Abstract

The tryptamine pathway is one of five proposed pathways for the biosynthesis of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), the primary auxin in plants. The enzymes AtYUC1 (Arabidopsis thaliana), FZY (Solanum lycopersicum), and ZmYUC (Zea mays) are reported to catalyze the conversion of tryptamine to N-hydroxytryptamine, putatively a rate-limiting step of the tryptamine pathway for IAA biosynthesis. This conclusion was based on in vitro assays followed by mass spectrometry or HPLC analyses. However, there are major inconsistencies between the mass spectra reported for the reaction products. Here, we present mass spectral data for authentic N-hydroxytryptamine, 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin), and tryptamine to demonstrate that at least some of the published mass spectral data for the YUC in vitro product are not consistent with N-hydroxytryptamine. We also show that tryptamine is not metabolized to IAA in pea (Pisum sativum) seeds, even though a PsYUC-like gene is strongly expressed in these organs. Combining these findings, we propose that at present there is insufficient evidence to consider N-hydroxytryptamine an intermediate for IAA biosynthesis.

Auxin is ubiquitous throughout the plant kingdom (Davies, 2010; Ross and Reid, 2010) and is involved in a wide variety of plant processes (Davies, 2010). However, although the primary auxin found in plants (indole-3-acetic acid [IAA]) was identified almost 80 years ago, there remain large gaps in our knowledge of its biosynthesis (for review, see Bartel et al., 2001; Ljung et al., 2002; Vanneste and Friml, 2009; Normanly, 2010; Zhao, 2010). There are four biosynthetic pathways proposed for Trp-dependent IAA biosynthesis in plants: the indole-3-acetaldoxime, indole-3-pyruvic acid, indole-3-acetamide, and tryptamine pathways. None of these pathways has been fully characterized, although there have been significant advances in the past few years due to the identification of new auxin mutants and more sensitive analytical techniques (e.g. Tao et al., 2008; Quittenden et al., 2009; Sugawara et al., 2009). Recently, the tryptamine pathway (Fig. 1) has received particular attention due to the identification of the YUC genes (Zhao et al., 2001; Tobeña-Santamaria et al., 2002; Cheng et al., 2006; Expósito-Rodríguez et al., 2007; Yamamoto et al., 2007; LeClere et al., 2010; Minorsky, 2010). The YUC proteins are homologous to known flavin-containing monooxygenases. It has been reported that AtYUC1 (Arabidopsis thaliana; Zhao et al., 2001) and its putative homologs in other species (Expósito-Rodríguez et al., 2007; LeClere et al., 2010) catalyze the formation of N-hydroxytryptamine from tryptamine. Both Zhao et al. (2001) and LeClere et al. (2010) based this conclusion on mass spectral identification of the product of an in vitro assay, using recombinant YUC (from Arabidopsis and maize [Zea mays], respectively) as the enzyme and tryptamine as the substrate. Expósito-Rodríguez et al. (2007), who isolated the YUC homolog FZY from tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), provided no mass spectrometry (MS) identification of their in vitro product, instead relying solely on HPLC coelution of the product with synthetic N-hydroxytryptamine. Zhao et al. (2001) and LeClere et al. (2010) did not present mass spectral data for synthetic N-hydroxytryptamine for comparison, and there are numerous differences between their published mass spectra for the putative N-hydroxytryptamine produced by their in vitro assays.

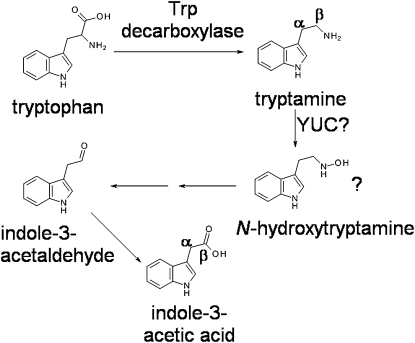

Figure 1.

The previously proposed pathway for tryptamine-dependent IAA biosynthesis. The involvement of N-hydroxytryptamine was first suggested by Zhao et al. (2001). The positions of some carbon atoms in tryptamine and IAA are indicated.

Extensive mutant-based studies clearly show the importance of YUC genes for plant development (Cheng et al., 2006), and since these genes are linked to the tryptamine pathway by N-hydroxytryptamine, it is of paramount importance to definitively characterize this compound. As yet, this has not been achieved by electrospray ionisation (ESI) MS, the method used by Zhao et al. (2001) and LeClere et al. (2010) to identify reaction products. In this study, we reexamine the tryptamine pathway by determining the mass spectral properties of our previously synthesized N-hydroxytryptamine (Quittenden et al., 2009) for comparison with the published spectra for putative N-hydroxytryptamine and related compounds. In addition, we conduct metabolism studies using pea (Pisum sativum) seeds to determine whether tryptamine is metabolized in these organs. We also determine whether YUC-like genes are expressed in pea seeds.

RESULTS

Mass Spectra of Authentic N-Hydroxytryptamine and Serotonin

We synthesized N-hydroxytryptamine as described by Quittenden et al. (2009), confirming its identity by 1H- and 13C-NMR (1H-NMR [DMSO] δ: 2.82 [t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H], 2.99 [t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H], 3.38 [bs, 2H], 6.95 [t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H], 7.04 [t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H], 7.11 [s, 1H], 7.31 [d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H], 7.49 [d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H], 10.77 [s, 1H]; 13C-NMR [DMSO] δ: 23.6 [CH2], 55.1 [CH2], 112.0 [CH], 113.1 [C], 118.8 [CH], 118.9 [CH], 121.5 [CH], 123.3 [CH], 128.0 [C], 136.9 [C]; see Hino et al. [1990] for 1H-NMR data for comparison) and MS. Our synthetic N-hydroxytryptamine was analyzed by liquid chromatography (LC)-ESI MS (Fig. 2A), along with commercially obtained serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine; Fig. 2B) and tryptamine (Supplemental Fig. S1; both compounds were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich). Our spectra were obtained using a Thermo LTQ ion trap/Orbitrap high-resolution mass spectrometer combination to enable the assignment of empirical formulae to the ion-trap-generated product ions, based on mass measurements to 5 ppm accuracy. MS, MS/MS (MS2), and MS/MS/MS (MS3) were performed for all three compounds.

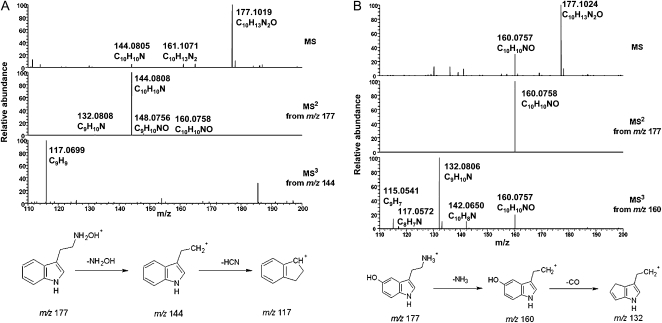

Figure 2.

MS, MS2, and MS3 data for N-hydroxytryptamine (A) and serotonin (B) and suggested fragmentation pathways for each. The collision energy for MS2 and MS3 was 35%.

The mass spectrum of N-hydroxytryptamine revealed an intense [M+H]+ ion at a mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) 177 with a less abundant ion at m/z 144 (loss of NH2OH). The predominant product ion of m/z 177 was m/z 144 (loss of NH2OH; MS2, Fig. 2A), and the predominant product ion of m/z 144 was m/z 117 (loss of HCN; MS3, Fig. 2A). A peak at m/z 160 was detected in MS2 but was very weak (1%–3% of m/z 144 depending on collision energy) and is not even visible in Figure 2A. By contrast, the mass spectrum of serotonin (also with an [M+H]+ ion at m/z 177) revealed ions predominantly at m/z 160 (loss of NH3) in MS2 and m/z 132 (loss of CO) in MS3. The losses of HCN and CO (outlined in Fig. 2) involve complex rearrangements and the likely formation of new rings (as proposed in McClean et al., 2002); hence, the charge and double bond distribution may not be localized exactly as shown.

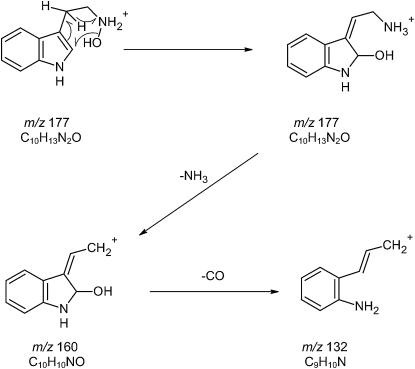

The N-hydroxytryptamine MS2 spectrum revealed a very weak signal at m/z 160. With less accurate instrumentation, this loss of 17 D from the [M+H]+ (m/z 177) ion could be attributed to loss of either a hydroxyl radical or NH3. However, mass data accurate to 5 ppm allow unequivocal determination of the empirical formula of the product ion and thereby the fragment lost. The [M+H]+ ion had an exact mass of 177.1019 D, while that of the product ion was 160.0758 D. This measured loss of 17.0261 D is NH3 (17.0265 D) rather than a hydroxyl radical (17.0077 D; these masses were calculated on the basis of individual isotopes, not standard atomic weights). We suggest that in MS2, an internal rearrangement transfers the hydroxyl group to the indole ring (Fig. 3). We also conducted MS3 on the m/z 160 ion from MS2, which gave m/z 142.0650 and m/z 132.0807 as major product ions, due to losses of H2O and CO, respectively. This indicates that the m/z 160 ion from N-hydroxytryptamine contained oxygen, confirming that it was not formed through loss of a hydroxyl radical (as N-hydroxytryptamine only contains one oxygen atom).

Figure 3.

Possible mechanism for the loss of NH3 from N-hydroxytryptamine in MS2 producing the very low abundance product ion at m/z 160 and the subsequent loss of CO in MS3.

It is important to note that the synthetic N-hydroxytryptamine was quite unstable on storage and readily converted to tryptamine. Consequently, the sample analyzed by LC-MS contained N-hydroxytryptamine with small to significant amounts of tryptamine depending on the age of the standard. The small ion at m/z 161 in the mass spectrum of N-hydroxytryptamine (Fig. 2A) was in fact derived from the tail of the tryptamine HPLC peak, which eluted 1.3 min before N-hydroxytryptamine on reverse-phase LC, and not from N-hydroxytryptamine itself (N-hydroxytryptamine is less polar than tryptamine, as also shown by our thin-layer chromatography [TLC] analyses; Supplemental Fig. S2). Another way in which artifact ions can be introduced in LC-MS analysis is through thermally induced decomposition of the analyte. In our atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) analyses of N-hydroxytryptamine, a strong m/z 161 ion was observed (data not shown) through the thermally induced decomposition of N-hydroxytryptamine to tryptamine; in APCI mass spectra, the m/z 161 ion was typically stronger than m/z 177.

We compared our spectra with those of Zhao et al. (2001) and LeClere et al. (2010) (adapted in Fig. 4). Both these groups also used ESI MS to identify the reaction products (in addition, LeClere et al. [2010] included MS2 and MS3 data; the spectra are reproduced here with permission). The general appearance of our synthetic N-hydroxytryptamine MS (Fig. 2A) was quite different from that obtained by Zhao et al. (2001) for AtYUC1 enzyme products. The Zhao et al. (2001) spectrum had a very unusual appearance for an ESI MS, due to the very weak putative [M+H]+ ion at m/z 177 and an abundance of fragment ions dominating the spectrum. ESI mass spectra are normally characterized by an intense signal for the protonated molecule (Smith et al., 1990) with little or no fragmentation, as illustrated by both our data and those of LeClere et al. (2010).

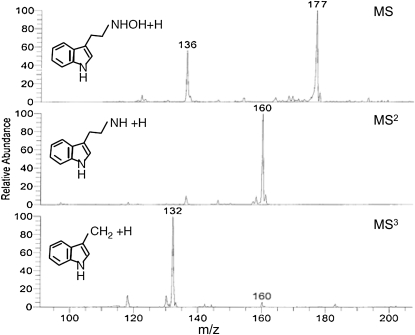

Figure 4.

MSn data for putative N-hydroxytryptamine (adapted from LeClere et al. [2010] with permission).

Our MSn data for authentic N-hydroxytryptamine (Fig. 2A) were also completely different from those presented by LeClere et al. (2010) for their putative N-hydroxytryptamine (Fig. 4). The LeClere et al. MS2 result shows a large m/z 160 ion, whereas we obtained predominantly m/z 144. On the other hand, the ring-hydroxylated tryptamine, serotonin, generates spectra (Fig. 2B) that closely resemble those shown by LeClere et al. (Fig. 4). The same may also be true for other ring-hydroxylated tryptamines and for α- and β-hydroxytryptamine (see Fig. 1 for these positions). Serotonin had an intense m/z 160 ion in MS2, caused by loss of NH3, and an intense m/z 132 in MS3, from subsequent loss of CO. Our accurate mass data support this previously proposed hypothesis (McClean et al., 2002) for the fragmentation of serotonin. Although N-hydroxytryptamine does undergo these same losses (Fig. 2A), the relative abundance of the m/z 160 ion is extremely low.

Metabolism of Trp and Tryptamine in Pea Seeds

The results discussed above indicate that N-hydroxytryptamine may not be a product of tryptamine metabolism by the YUCCA enzymes during auxin biosynthesis. However, the tryptamine pathway may still be important. Indeed, we recently demonstrated that tryptamine can be converted to IAA in pea roots, although we did not detect N-hydroxytryptamine in that study (Quittenden et al., 2009). To determine whether tryptamine acts as an IAA precursor in other parts of the pea plant, we investigated IAA synthesis in young developing seeds, about 14 d postanthesis (DPA), when the seeds weighed between 40 and 130 mg and still contained liquid endosperm. In initial experiments, we injected substrates into the endosperm of intact seeds in situ, perforating the pod wall and testa with a sterile syringe (Ross et al., 1993). In the experiments reported in Table I and Figure 5, for ease of substrate administration, the seeds were excised from the pod prior to injection.

Table I. Percentage of label incorporation into Trp, tryptamine, and IAA after feeding [2H4]Trp and [2H5]tryptamine to excised pea seeds, as determined by UPLC-MS.

For [2H4]Trp treatments, 1 μL of a 1,000 ng μL−1 solution was injected. For [2H5]tryptamine treatments, 1 μL of a 100 ng μL−1 solution was injected. The percentage of deuterium labeling was calculated by dividing the area of the labeled peak by the sum of the areas of the labeled and unlabeled peaks. Shown are means ± se (n = 4); 0% labeling means that any labeling was below the limit of detection.

| Substrate Injected | Period of Incubation | Compound Analyzed | Average Deuterium Labeling |

| h | % | ||

| [2H4]Trp | 3 | Trp | 19 ± 5 |

| IAA | 29 ± 6 | ||

| [2H4]Trp | 6 | Trp | 8 ± 4 |

| IAA | 13 ± 4 | ||

| [2H5]Tryptamine | 3 | Tryptamine | 99.7 ± 0.4 |

| IAA | 0 | ||

| [2H5]Tryptamine | 6 | Tryptamine | 99.8 ± 0.1 |

| IAA | 0 |

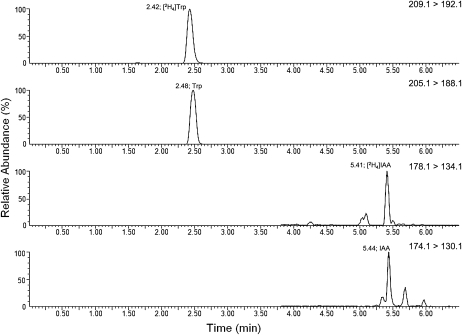

Figure 5.

UPLC-MRM MS/MS chromatograms for an extract from [2H4]Trp-fed excised pea seeds, showing the presence of labeled Trp (top channel), unlabeled Trp (2nd from top), labeled IAA (2nd from bottom), and unlabeled IAA (bottom channel). Retention times are shown near the apex of the relevant peaks. Trp channels are monitoring positive ions; IAA channels are monitoring negative ions.

Regardless of whether the seeds were in situ or excised, the results show that IAA becomes deuterated after administration of deuterated Trp (Table I; Fig. 5). However, labeled IAA was undetectable after feeding [2H5]tryptamine, as shown by ultraperformance liquid chromatography (UPLC)-MS (Table I) and GC-MS (after injections in situ; data not shown). This indicates that the conversion of Trp to IAA does not proceed via tryptamine in developing pea seeds.

To investigate the overall metabolism of tryptamine in pea seeds, we injected [14C]-labeled tryptamine in situ. The resulting extract contained only a single peak on HPLC radiocounting (Supplemental Fig. S3), corresponding to tryptamine itself, indicating that this compound was not metabolized to any product in the seeds. By contrast, [14C]tryptamine was readily converted to [14C]N-acetyltryptamine in pea roots (Quittenden et al., 2009).

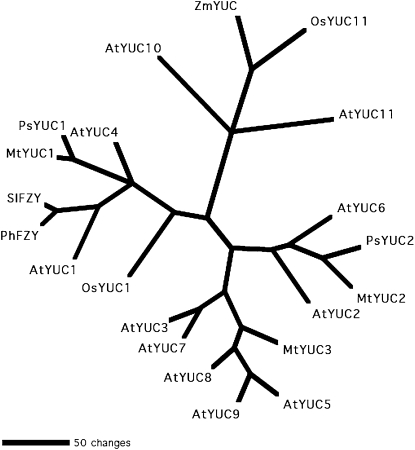

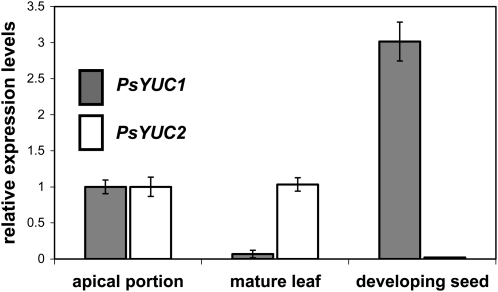

We obtained evidence for at least two PsYUC-like genes from pea; approximately 1-kb fragments of the expected 1.1-kb coding region were amplified and shown to align closely with previously isolated YUCs (Fig. 6). PsYUC1 is strongly expressed in developing seeds (Fig. 7). The lack of tryptamine metabolism in these organs indicates that the function of the seed-expressed PsYUC1 may be to catalyze other reactions.

Figure 6.

Inferred phylogenetic relationship of two pea YUC enzymes, PsYUC1 and PsYUC2, with other YUC-like enzymes. The unrooted phylogram was generated by Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony PAUP 4.0b10 analysis (Swofford, 2003) using putative amino acids excluding gaps. Included were AtYUC1 (At4g32540), AtYUC2 (At4g13260), AtYUC3 (At1g04610), AtYUC4 (At5g11320), AtYUC5 (At5g43890), AtYUC6 (At5g25620), AtYUC7 (At2g33230), AtYUC8 (At4g28720), AtYUC9 (At1g04180), AtYUC10 (At1g48910), and AtYUC11 (At1g21430; Cheng et al., 2006) from Arabidopsis, ZmYUC (NP_001105991.1 and NM_001112521.1; LeClere et al., 2010) from maize, OsYUC1 (Os01g0645400; Yamamoto et al., 2007) and OsYUC11 (Os12g0189500; Gallavotti et al., 2008) from rice, and the FLOOZY proteins from Petunia hybrida PhFZY (AAK74069.1; Tobeña-Santamaria et al., 2002) and tomato SlFZY (CAJ46041.1; previously referred to as ToFZY; Expósito-Rodríguez et al., 2007). Medicago YUC-like sequences were obtained by BLAST search from the IMGAG database at M. truncatula sequencing resources (www.medicago.org/genome) and named MtYUC1 (Medtr1g013140.1), MtYUC2 (Medtr1g009490.1), and MtYUC3 (Medtr7g117800.1).

Figure 7.

Transcript levels of two of the pea YUCCA genes in different parts of pea plants, measured by quantitative real-time PCR. Shown are means with se (n = 4 or 5). For each gene, the transcript level was compared to the housekeeper PsActin, and the apical portion sample value was set to 1, then other levels are shown relative to that value. The apical portion harvested was of the bud and leaflet above node 7, and the mature leaf sample was the fully expanded leaf at node 4, harvested from 22-d-old seedlings with uppermost fully expanded leaf at node 6 (five replicates with six plants combined in each). Developing seeds (four replicates with five to seven seeds from three pods from different plants) were harvested, with fresh weights of 60 to 80 mg seed−1.

DISCUSSION

In this article, we characterize N-hydroxytryptamine, suggested to be an important intermediate in IAA biosynthesis (Zhao et al., 2001). A key aspect of our synthesized compound is that on ESI MS, the major MS2 ion is m/z 144, not m/z 160. N-Hydroxytryptamine is less polar than its supposed precursor, tryptamine, and is relatively unstable. These findings, in particular our MS data, allow us to assess previous reports on the detection of N-hydroxytryptamine. Zhao et al. (2001) reported that N-hydroxytryptamine is produced when tryptamine is supplied to AtYUC1 as an in vitro substrate, and as a result, most tryptamine pathway variants proposed after 2001 include the step tryptamine → N-hydroxytryptamine (Bartel et al., 2001; Ljung et al., 2002; Woodward and Bartel, 2005; Sugawara et al., 2009; Vanneste and Friml, 2009; LeClere et al., 2010; Normanly, 2010; Zhao, 2010). Zhao et al. (2001) used MS to identify the in vitro product as N-hydroxytryptamine; however, no standard was reported for comparison, and when compared with our spectra (Fig. 2A), their data do not definitively identify this compound. Zhao et al. proposed that the major fragment ions that they observed at m/z 160, 144, and 130 resulted from losses of a hydroxyl radical (17 D), hydroxylamine (33 D), and a neutral CH2NH2OH (47 D) species, respectively. However, the loss of the hydroxyl radical breaks the even-electron rule (Karni and Mandelbaum, 1980), and here we show that this loss does not occur from authentic N-hydroxytryptamine. The even-electron rule, a fundamental MS principle, states that even-electron species, such as the [M+H]+ ion at m/z 177, should not produce energetically less favorable odd-electron species by the loss of radicals through homolytic bond cleavage, but rather should form other even-electron species through the loss of neutral molecules. Exceptions to this rule in ESI MS and other even-electron ionization techniques are rare, and the occasional odd-electron ions that do occur are of low relative intensity (Thurman et al., 2007). Given that Zhao et al. (2001) presented a mass spectrum without MS2 data, there may not even be a direct link between the m/z 177, 160, and 144 ions in that spectrum (if, for example, more than one compound was present in their analyte). The presence of strong ions at m/z 160, 132, and 130 in their spectrum is difficult to reconcile with our data (Fig. 2A). Zhao et al. made no firmer statement than that their mass spectrum was consistent with N-hydroxytryptamine. There is now a significant possibility that the product obtained by Zhao et al. was not N-hydroxytryptamine; therefore, we propose that AtYUC1 may not catalyze the conversion of tryptamine to N-hydroxytryptamine in vitro. Zhao (2010) also notes that due to the broad in vitro substrate specificity of flavin-containing monooxygenases, tryptamine may not be the primary AtYUC1 substrate. Furthermore, it has been suggested that YUC may in fact operate in the same pathway as TAA1, a key enzyme in the indole-3-pyruvic acid pathway (Strader and Bartel, 2008).

Expósito-Rodríguez et al. (2007) cloned a YUC-like gene (FZY) from tomato into Escherichia coli and used the expression product for an in vitro assay. These authors claim to have synthesized N-hydroxytryptamine and to have confirmed its identity using 1H-NMR. Although their 1H-NMR data are consistent with ours, they do not present 13C-NMR results, and their electron ionization MS data show an M+ ion at m/z 174, which is incorrect for N-hydroxytryptamine (M = 176.0950). In our LC-MS analysis of N-hydroxytryptamine, we observed the [M+H]+ ion at m/z 177.1019, which implies an M of 176.0941, in good agreement with the calculated value. Possibly, Expósito-Rodríguez et al. analyzed a synthetic by-product by MS. These authors claim that the product of their in vitro assay coeluted with their synthesized N-hydroxytryptamine on LC; however, this claim is rendered unconvincing by the very close retention times of tryptamine and the synthetic N-hydroxytryptamine on their system. These authors provided no MS identification of their product and therefore may not have obtained N-hydroxytryptamine. We therefore suggest that FZY may not catalyze the conversion of tryptamine to N-hydroxytryptamine in vitro.

Most recently, LeClere et al. (2010) isolated a gene from maize, ZmYUC, which is 40% homologous (amino acid sequence) to AtYUC1. This group also performed an in vitro assay, using tryptamine as a substrate, and claims to have obtained N-hydroxytryptamine as a product. As shown by their TLC result, there was strong conversion to a product, which resulted in good MS data (Fig. 4). However, these data clearly indicate that their in vitro product was not N-hydroxytryptamine. In particular, N-hydroxytryptamine does not give an intense ion at m/z 160 in MS2, as their compound did (Fig. 4), but rather an intense ion at m/z 144 (Fig. 2A). We note that differences in collision energy can create slightly different relative ion abundances in MS2 spectra (LeClere et al. do not report the collision energy used). However, we have tested a range of collision energies and three different mass spectrometers, including triple quadrupole and ion trap instruments, and in all cases the major product ion in MS2 for N-hydroxytryptamine was m/z 144, and the m/z 160 signal was never more than a few percent relative to m/z 144. LeClere et al. explain their large m/z 160 and 132 ions in terms of losses of OH and CH2NH, respectively, but there are at least two problems with this scheme. First, these losses give rise not to m/z 132 in MS3 but m/z 131 (177 − 17 − 29 = 131). Second, the even-electron rule (Karni and Mandelbaum, 1980) is broken by the suggested loss of OH from N-hydroxytryptamine in MS2. We suggest instead that the observed ions at m/z 160 and 132 in their MS2 and MS3 spectra for their reaction product are due to losses of NH3 and CO, respectively, entirely analogous with our observations for serotonin (Fig. 2B) and with the NH3 loss for tryptamine (Supplemental Fig. S1).

Hence, the data presented by LeClere et al. (2010) unequivocally show that the ZmYUC reaction product was not N-hydroxytryptamine. Instead, their data indicate the possibility of hydroxylation either on the indole ring or the α-carbon of the side chain. We are not suggesting that their product was serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine), since on TLC the retention factor of serotonin is less than that of tryptamine (data not shown), inconsistent with the LeClere et al. results. Nevertheless, if hydroxylation at the α-position reduces polarity, both the retention factor value and the spectrum observed might be explained. It should be noted that flavin-containing monooxygenases are usually considered to catalyze oxidation of heteroatoms, but there are exceptions involving oxidation of carbon (e.g. Driscoll et al., 2010).

Although the YUC-like proteins tested may not catalyze the formation of N-hydroxytryptamine, tryptamine-dependent IAA biosynthesis may still be important in a variety of species (e.g. pea roots; Quittenden et al., 2009). To investigate whether tryptamine plays a role in IAA synthesis in pea seeds, we injected Trp and tryptamine into these organs, during the liquid endosperm stage (approximately 14 DPA). The results indicate that Trp is a precursor to IAA in pea seeds. However, we could find no evidence that Trp-dependent IAA biosynthesis occurred via the tryptamine pathway: when we administered [14C]tryptamine and [2H5]tryptamine, no label incorporation into IAA was evident, in contrast with the results from pea roots (Quittenden et al., 2009). Moreover, we could find no evidence for either labeled or unlabeled N-hydroxytryptamine, even though at least one PsYUC-like gene was expressed in the developing seeds.

YUC homologs are known to be expressed in a number of plant species (Zhao et al., 2001; Tobeña-Santamaria et al., 2002; Expósito-Rodríguez et al., 2007; LeClere et al., 2010), and there is now evidence that at least two are expressed in pea (Figs. 6 and 7). It appears, however, that the YUC gene expressed in pea seeds is not involved in tryptamine metabolism.

CONCLUSION

Thus, we see that the evidence for the supposedly rate-limiting step of the tryptamine IAA biosynthesis pathway is unconvincing. The data presented by Zhao et al. (2001) and Expósito-Rodríguez et al. (2007) do not provide enough evidence to identify the product, while those of LeClere et al. (2010) show that their product is not N-hydroxytryptamine. There is little evidence that this conversion happens in vitro and no evidence that it happens in vivo, as there have been no successful labeling experiments performed using plant systems, nor any clear identification of endogenous N-hydroxytryptamine. Furthermore, Zhao et al. (2001) proposed that N-hydroxytryptamine is next converted to indole-3-acetaldoxime and then finally to IAA via indole-3-acetaldehyde. However, Sugawara et al. (2009) showed that indole-3-acetaldoxime levels were not significantly altered in the yuc1 yuc2 yuc4 yuc6 quadruple mutant, indicating that the plant is not dependent on the tryptamine pathway for the synthesis of indole-3-acetaldoxime.

Despite the reservations outlined above, it is still possible that YUC proteins are involved in IAA biosynthesis. One scenario that places YUC in the tryptamine pathway involves it catalyzing the β-hydroxylation of tryptamine. However, this hypothesis would be difficult to test as the β-hydroxylated product would be unstable, hydrolyzing to the aldehyde immediately in the presence of water. This expected instability implies that the abundant reaction product obtained by LeClere et al. was not β-hydroxytryptamine.

An alternative possibility is that the YUC proteins tested catalyze a step, or several steps, leading to a compound or compounds other than IAA, as suggested by Tobeña-Santamaria et al. (2002). This compound may be an auxin or auxin-like compound, in view of the auxin-related phenotypes of yuc mutants (Cheng et al., 2006), and this explanation would account for the observation that mutants with reduced YUC activity typically do not contain less IAA than the wild type (Tobeña-Santamaria et al., 2002; Culler, 2007; Tao et al., 2008).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

LC-MS

The main LC-MS system consisted of a Thermo Fisher Surveyor MS-plus HPLC with a μBondapak C18 10 μm, 100 × 8-mm Radial-Pak cartridge coupled to a Thermo LTQ Orbitrap high-resolution MS. The MS was operated in both APCI and ESI modes. In APCI mode, a vaporizer temperature of 350°C and a capillary temperature of 200°C were used, with a N2 sheath and auxiliary gas at 40 and 10 psi, respectively, and a tube lens voltage of 50 V. In ESI mode, a source voltage of 5 kV was applied at the tip with a capillary temperature of 300°C, N2 sheath and auxiliary gases at 50 and 10 psi, respectively, and a tube lens voltage of 50 V. The collision energy for MS/MS experiments was 35%. The system was run using the following conditions: eluent A, 1% (v/v) acetic acid in water; eluent B, 1% (v/v) acetic acid in acetonitrile (ACN); flow rate, 1 mL min−1; gradient, 0 to 20 min; 10% to 60% B, 20 to 30 min, 60% to 100% B, 30 to 35 min, 100% B. Analyses of N-hydroxytryptamine were also carried out using a Finnigan LCQ Classic ion trap mass spectrometer (data not shown).

TLC

Authentic tryptamine and N-hydroxytryptamine were analyzed by TLC using Merck silica gel 60 F254 aluminum-backed sheets. The solvent mixture was CH2Cl2/CH3OH/triethylamine (15:4:1; as previously described in Zhao et al., 2001). TLC plates were visualized under a 254-nm UV lamp and then treated with phosphoric acid/ceric sulfate dip (37.5 g phosphomolybdic acid, 7.5 g ceric sulfate, 37.5 mL sulfuric acid, and 720 mL water) and heated.

Plant Material

The line of pea (Pisum sativum) used was derived from cultivar Tordag (Hobart L107) and is wild type with respect to internode length genes. All plants were grown, two seeds per pot, in sterilized peat moss/sand potting mix. Plants were grown under a mixed light source in an air-conditioned glasshouse and watered regularly, as described by Jager et al. (2007).

Substrate Administration, Harvesting, and Extract Preparation

Substrates were applied to developing pea seeds, approximately 14 DPA, when the seeds weighed between 40 and 130 mg, using a syringe sterilized with ethanol. Two methods were used: we either injected substrates into the seeds while they were still attached to the parent plant (i.e. perforating the pericarp and testa; Ross et al., 1993) or excised the seeds before injection for ease of performing that operation. For the experiment reported in Table I and Figure 5, 48 seeds were excised from the pods and split into 16 equal groups, each of which was placed on moist filter paper in separate petri dishes. Substrates ([2H4]Trp, [2H5]Trp, and [2H5]tryptamine, synthesized as described in Quittenden et al., 2009) were then injected into the endosperm. For [14C]tryptamine (ViTrax Radiochemicals) treatments, the substrate was injected into seeds still attached to the plant. Substrates were injected in 1 μL of Milli-Q water.

Excised seeds were left for 3 or 6 h after substrate administration and in situ seeds for approximately 17 h before being harvested into between 5 and 10 mL of −20°C 4:1 methanol/water containing 250 mg L−1 butylated-hydroxytoluene. The extract was held at −20°C for a minimum of 1 h, after which the plant material was macerated and left to extract overnight at 4°C. The resulting extract was then filtered through a Whatman No. 1 filter paper and stored at −20°C until needed. Extracts for analysis by UPLC-MS were partially purified using C18 cartridges, while those for analysis of IAA by GC-MS were purified and derivatized as before (Quittenden et al., 2009).

UPLC-MS

Trp, tryptamine, and IAA were monitored as their 2H0, 2H4, and 2H5 forms by combined UPLC and multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) MS/MS mode using a Waters Acquity H-Class UPLC and a Waters Xevo triple quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with an ESI source, using Waters MassLynx software. The column was a Waters Acquity BEH C18 (5 cm × 2.1 mm × 1.7-μm particles). Mobile phase A was 1% acetic acid in water, and B was methanol. The flow rate was 0.3 mL min−1, and the gradient was 95% A:5% B to 80% A:20% B at 3 min, then to 20% A:80% B at 6 min. Column temperature was 35°C. Injections were 10 μL. Positive ions were monitored for Trp and tryptamine, while for IAA, negative ions were monitored. All assays used a desolvation temperature of 400°C and a sheath gas flow of 1000 L/h. Peak widths were 0.5 on Q1 and 0.75 on Q2. MRM transitions and detailed MS conditions were as follows: [2H0]Trp m/z 205.1 to 188.1 ([M+H]+ to [M+H-NH3]+), [2H4]Trp m/z 209.1 to 192.1 and 191.1 ([M+H]+ to [M+H-NH3]+ and [M+H-NH22H]+), cone 17 V, collision energy 10 V, needle voltage 2.3 kV, dwell 100 ms per channel; [2H0]tryptamine m/z 161.1 to m/z 144.1 ([M+H]+ to [M+H-NH3]+), [2H5]tryptamine m/z 166.1 to m/z 148.1 and 147.1 ([M+H]+ to [M+H-NH3]+ and [M+H-NH22H]+), cone 13 V, collision energy 12 V, needle voltage 2.3 kV, dwell 100 ms per channel, [2H0]IAA m/z 174.1 to 130.1, [2H4]IAA ([M-H]+ to [M-H-CO2]+ for both forms), cone 15 V, collision energy 18 V, needle voltage 2.1 kV, dwell 150 ms per channel. For the 2H5 assay, conditions were identical except that the precursor and product ions for the deuterated product were 1 D higher. Retention times were as follows: [2H0]Trp, 2.48 min; [2H4]Trp, 2.42 min; [2H0]tryptamine, 2.87 min; [2H5]tryptamine, 2.79 min; [2H0]IAA, 5.44 min; [2H4]IAA, 5.41 min.

Note that for [2H5]tryptamine and [2H4]Trp, full scan data on standards revealed the MS/MS product ions were due to losses of both NH22H (18) and NH3 (17) from the protonated molecule; both channels were therefore included for these analytes.

HPLC Radiocounting

Reverse-phase HPLC was used to determine if radiolabeled substrates had been metabolized by the plant. The HPLC system consisted of a Rheodyne Manual Injector fitted with a 2-mL sample loading loop, a Waters Absorbance Detector, and a μBondapak C18 10 μm, 100 × 8-mm Radial-Pak cartridge, with two Waters 510 Millipore HPLC pumps (Jager et al., 2005). An aliquot of the extract was dried in vacuo. The residue was then loaded in 2 mL of initial conditions (79:10:1 water/ACN/acetic acid). The system was run using the following conditions: eluent A, 1% acetic acid in water; eluent B, 1% acetic acid in ACN; flow rate, 1 mL min−1; gradient, 0 to 20 min, 10% to 60% B; 20 to 30 min, 60% to 100% B; and 30 to 35 min, 100% B.

Cloning YUC-Like Genes from Pea

Pea seed cDNA was synthesized with oligo(dT)20 primer (Superscript III; Invitrogen) from RNA extracted from immature pea seeds each with an average mass of 90 mg (RNeasy plant mini kit with on-column DNase digestion [Qiagen]). Degenerate primers were designed from blocks generated by CODEHOP (Rose et al., 1998) from conserved regions in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) YUCs (the forward primer in the highly conserved putative FAD binding motif GAGPSGLA and the reverse primer in the conserved WKGxxGLYxVG). These primers were then modified to reflect the nucleotide sequences of the full-length YUC-like Medicago truncatula sequences Medtr1g013140.1 (MtYUC1), Medtr1g009490.1 (MtYUC2), Medtr7g117800.1 (MtYUC3), and Medtr5g034600.1, obtained by a BLAST search from the International Medicago Genome Annotation Group (IMGAG) database at M. truncatula sequencing resources (www.medicago.org/genome).

PCR with Advantage 2 polymerase (Clontech) resulted in PCR fragments with the expected strong bands (approximately 1 kb) on agarose gel, which were purified (Wizard SV Gel and PCR cleanup system; Promega), ligated into pGEM-T easy, and transformed into JM109 competent Escherichia coli (Promega). Plasmid DNA was isolated from individual colonies (Wizard plus SV minipreps; Promega) and sequenced by Macrogen. Similarly, cDNA was also synthesized from the RNA extracted from the apical portion (combined apical bud and leaf at node 7) from 22-d-old pea seedlings.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Plant material for determinations of mRNA levels was immediately immersed in liquid nitrogen and ground frozen to a fine powder with a mortar and pestle. RNA was extracted from approximately 100 mg of ground tissue using the RNeasy plant mini kit including on column DNase treatment (Qiagen). Single-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA (1 μg) using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen). The cDNA (3 μL of 1/15 dilution) was used for quantitative real-time PCR using Sensimix plus SYBR (Quantace) following the manufacturer’s recommendations and run on a Rotorgene 2000 Dual-Channel machine (Qiagen). Mean mRNA levels of the gene of interest were calculated relative to the levels of actin.

For mRNA quantification, the following primer pairs were used: pea actin, 5′-GTGTCTGGATTGGAGGATCAATC-3′ and 5′-GGCCACGCTCATCATATTCA-3′ (Foo et al., 2005); PsYUC1, 5′-TTGCTACCGGTGAAAATGCTGA-3′and 5′-CATGAAAATGTTCCATACCATGAATC-3′; and PsYUC2, 5′-AGAGAATGCCGAGGCTGTTGTG-3′ and 5′-AAGTTCCATTCCAGAATTTCCACATCCAA-3′.

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers HQ439907 (PsYUC1) and HQ439908 (PsYUC2).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. ESI MS data for tryptamine.

Supplemental Figure S2. TLC chromatogram for tryptamine and N-hydroxytryptamine.

Supplemental Figure S3. HPLC-radiocounting histogram after feeding [14C]tryptamine.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ian Cummings, Tracey Winterbottom, Josephine Tilley, and Ella Hoban for technical assistance.

References

- Bartel B, LeClere S, Magidin M, Zolman BK. (2001) Inputs to the active indole-3-acetic acid pool: de novo synthesis, conjugate hydrolysis, and indole-3-butyric cid β-oxidation. J Plant Growth Regul 20: 198–216 [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Dai X, Zhao Y. (2006) Auxin biosynthesis by the YUCCA flavin monooxygenases controls the formation of floral organs and vascular tissues in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev 20: 1790–1799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culler AH. (2007) Analysis of the tryptophan-dependent indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis pathway in maize endosperm. PhD thesis. University of Minnesota, St. Paul [Google Scholar]

- Davies PJ. editor (2010) Plant Hormones: Biosynthesis, Signal Transduction, Action! Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll JP, Aliagas I, Harris JJ, Halladay JS, Khatib-Shahidi S, Deese A, Segraves N, Khojasteh-Bakht SC. (2010) Formation of a quinoneimine intermediate of 4-fluoro-N-methylaniline by FMO1: carbon oxidation plus defluorination. Chem Res Toxicol 23: 861–863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Expósito-Rodríguez M, Borges AA, Borges-Pérez A, Hernández M, Pérez JA. (2007) Cloning and biochemical characterisation of ToFZY, a tomato gene encoding a flavin monooxygenase involved in a tryptophan -dependent auxin biosynthesis pathway. J Plant Growth Regul 26: 329–340 [Google Scholar]

- Foo E, Bullier E, Goussot M, Foucher F, Rameau C, Beveridge CA. (2005) The branching gene RAMOSUS1 mediates interactions among two novel signals and auxin in pea. Plant Cell 17: 464–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallavotti A, Barazesh S, Malcomber S, Hall D, Jackson D, Schmidt RJ, McSteen P. (2008) sparse inflorescence1 encodes a monocot-specific YUCCA-like gene required for vegetative and reproductive development in maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 15196–15201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hino T, Hasegawa A, Liu JJ, Nakagawa M. (1990) 2-Hydroxy-1-substituted-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-β−carbolines. The Pictet-Spengler reaction of N-hydroxytryptamine with aldehydes. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 38: 59–64 [Google Scholar]

- Jager CE, Symons GM, Nomura T, Yamada Y, Smith JJ, Yamaguchi S, Kamiya Y, Weller JL, Yokota T, Reid JB. (2007) Characterization of two brassinosteroid C-6 oxidase genes in pea. Plant Physiol 143: 1894–1904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager CE, Symons GM, Ross JJ, Smith JJ, Reid JB. (2005) The brassinosteroid growth response in pea is not mediated by changes in gibberellin content. Planta 221: 141–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karni M, Mandelbaum A. (1980) The even-electron rule. Org Mass Spectrom 15: 53–64 [Google Scholar]

- LeClere S, Schmelz EA, Chourey PS. (2010) Sugar levels regulate tryptophan-dependent auxin biosynthesis in developing maize kernels. Plant Physiol 153: 306–318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljung K, Hull AK, Kowalczyk M, Marchant A, Celenza J, Cohen JD, Sandberg G. (2002) Biosynthesis, conjugation, catabolism and homeostasis of indole-3-acetic acid in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol 49: 249–272 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClean S, Robinson RC, Shaw C, Smyth WF. (2002) Characterisation and determination of indole alkaloids in frog-skin secretions by electrospray ionisation ion trap mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 16: 346–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minorsky P. (2010) On the inside. Plant Physiol 153: 1–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normanly J. (2010) Approaching cellular and molecular resolution of auxin biosynthesis and metabolism. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2: a001594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quittenden LJ, Davies NW, Smith JA, Molesworth PP, Tivendale ND, Ross JJ. (2009) Auxin biosynthesis in pea: characterization of the tryptamine pathway. Plant Physiol 151: 1130–1138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose TM, Schultz ER, Henikoff JG, Pietrokovski S, McCallum CM, Henikoff S. (1998) Consensus-degenerate hybrid oligonucleotide primers for amplification of distantly related sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 26: 1628–1635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross JJ, Reid JB. (2010) Evolution of growth-promoting plant hormones. Funct Plant Biol 37: 795–805 [Google Scholar]

- Ross JJ, Reid JB, Swain SM. (1993) Control of stem elongation by gibberellin A1: evidence from genetic studies including the slender mutant sln. Aust J Plant Physiol 20: 585–599 [Google Scholar]

- Smith RD, Loo JA, Edmonds CG, Barinaga CJ, Udseth HR. (1990) New developments in biochemical mass spectrometry: electrospray ionization. Anal Chem 62: 882–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strader LC, Bartel B. (2008) A new path to auxin. Nat Chem Biol 4: 337–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara S, Hishiyama S, Jikumaru Y, Hanada A, Nishimura T, Koshiba T, Zhao Y, Kamiya Y, Kasahara H. (2009) Biochemical analyses of indole-3-acetaldoxime-dependent auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 5430–5435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. (2003) PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods) v4. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y, Ferrer JL, Ljung K, Pojer F, Hong F, Long JA, Li L, Moreno JE, Bowman ME, Ivans LJ, et al. (2008) Rapid synthesis of auxin via a new tryptophan-dependent pathway is required for shade avoidance in plants. Cell 133: 164–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurman EM, Ferrer I, Pozo OJ, Sancho JV, Hernandez F. (2007) The even-electron rule in electrospray mass spectra of pesticides. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 21: 3855–3868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobeña-Santamaria R, Bliek M, Ljung K, Sandberg G, Mol JNM, Souer E, Koes R. (2002) FLOOZY of petunia is a flavin mono-oxygenase-like protein required for the specification of leaf and flower architecture. Genes Dev 16: 753–763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanneste S, Friml J. (2009) Auxin: a trigger for change in plant development. Cell 136: 1005–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward AW, Bartel B. (2005) Auxin: regulation, action, and interaction. Ann Bot (Lond) 95: 707–735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Kamiya N, Morinaka Y, Matsuoka M, Sazuka T. (2007) Auxin biosynthesis by the YUCCA genes in rice. Plant Physiol 143: 1362–1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. (2010) Auxin biosynthesis and its role in plant development. Annu Rev Plant Biol 61: 49–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Christensen SK, Fankhauser C, Cashman JR, Cohen JD, Weigel D, Chory J. (2001) A role for flavin monooxygenase-like enzymes in auxin biosynthesis. Science 291: 306–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.