Abstract

Mutations in superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) cause some forms of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (fALS). Affected tissues of patients and transgenic mouse models of the disease accumulate misfolded and aggregated forms of the mutant protein. In the present study we have identified specific sequences in human SOD1 that modulate the aggregation of fALS mutant proteins. From our study of a panel of mutant proteins, we identify two sequence elements in human SOD1 (residues 42–50 and 109–123) that are critical in modulating the aggregation of the protein. These sequences are components of the 4th and 7th β-strands of the protein, and in the native structure are normally juxtaposed as elements of the core β-barrel. Our data suggest that some type of intermolecular interaction between these elements may occur in promoting mutant SOD1 aggregation.

Keywords: Protein misfolding, Superoxide dismutase 1, Familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Introduction

Dominantly inherited mutations in superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) are linked to familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (fALS) [1]. To date, more than 140 mutations in SOD1 have been associated with fALS [2](http://alsod.iop.kcl.ac.uk/). Because these mutations have varied effects on enzyme activity and stability, it is thought that the mutant enzymes acquire one or more toxic properties [3]. The majority of fALS mutations are point mutations that occur predominantly at highly conserved amino acids [2, 4]. A subset of fALS mutations produce shifts in the reading frame or early termination codons that produce truncated mutant protein [2]. The effects of fALS mutations on enzyme activity, turnover, and folding of the SOD1 protein vary considerably [3, 5, 6]. Enzyme activity ranges from undetectable to normal [5, 7–10], and many mutants increase the susceptibility of SOD1 to disulfide reduction [11]. One property that may be shared by all mutants is a higher inherent propensity to form large sedimentable structures that are insoluble in non-ionic detergent [2, 12]. To date, the inherent aggregation propensity of more than 40 different fALS mutants of SOD1 has been examined in cell culture models and all have been found to generate aggregates [2].

The role of large aggregates of mutant protein in neurotoxicity is not well understood. Recent studies have revealed a relationship between the relative rate at which mutant SOD1 forms large aggregates and the rapidity with which the human disease progresses [2, 13]. For example, the A4V mutation is associated with rapidly progressing disease and a high inherent propensity to aggregate whereas the H46R mutation is associated with slowly progressing disease and a low propensity to aggregate [2]. In transgenic mouse models of ALS, the large sedimentable aggregates begin to accumulate to significant levels at the age at which symptoms are first noticeable and build in abundance as symptoms progress [14, 15]. However, in mice that express the G93A and G37R fALS mutants, it is possible to accelerate disease by increasing the levels of the copper chaperone for SOD1 (CCS) and in such cases the large sedimentable aggregates of mutant protein do not accumulate [16, 17]. Notably, increasing CCS levels has no effect on the course of disease in mice that express the G85R and L126Z FAL S mutants [17]. Thus, although it is possible to induce ALS-like symptoms in mice expressing mutant SOD1 without generating aggregates, such aggregates have been described in multiple mouse models that express only mutant SOD1 [13, 18–23].

The mechanisms involved in the aggregation of SOD1 are not completely understood. Considerable attention has been placed on the role of disulfide cross-linking in the formation of SOD1 aggregates [4, 22, 24, 25]. Human SOD1 encodes 4 cysteines at positions 6, 57, 111, and 146. Studies in vitro and in cell culture suggest that cysteine residues 6 and 111 participate in mutant SOD1 aggregation perhaps by mediating intermolecular disulfide bonds [22, 24] or by participating in other types of intermolecular interactions [25]. In symptomatic SOD1 transgenic mice, high-molecular-weight, disulfide cross-linked forms of human SOD1 are prominent in the detergent-insoluble protein fraction, which become more abundant as mice approach disease endstage [4, 14, 22]. However, we have demonstrated that SOD1 aggregates are not stabilized by disulfide cross-linking alone [14]. Moreover, missense mutations at cysteines 6, 111, and 146 cause fALS (http://alsod.iop.kcl.ac.uk/). In cell culture models, SOD1 variants with mutations at these cysteine residue aggregate robustly and when combined into one recombinant gene with an experimental mutation to eliminate cysteine 57, the resultant mutant SOD1 protein retains the ability to aggregate [25]. Lastly, fibrillar aggregates of human SOD1, formed in vitro, that resemble amyloid structures are not extensively cross-linked by disulfide bonding [26]. Overall, the weight of evidence indicates that disulfide cross-linking is secondary to other mechanisms of protein self-assembly in the formation of large aggregate structures.

In studies to examine the role of disulfide cross-linking in mutant SOD1 aggregation, described above, there has been much focus on the cysteine at position 111 as a possible mediator of cross-linking. In cell culture and in vitro models of mutant SOD1 aggregation, mutagenesis of this cysteine to serine has been shown to reduce the potential of human SOD1 harboring an fALS mutation to aggregate to a level similar to wild-type protein [22, 24, 25]. Notably, in NSC-34 cells that inducibly express mutant SOD1, the toxicity of the fALS SOD1 variants A4V, C6F, G93A, and C146R was diminished by mutation of cysteine 111 to serine, correlating with diminished generation of detergent-insoluble aggregates [24]. Although this finding is consistent with the idea that disulfide cross-linking, via cysteine 111, could be important in aggregation and toxicity, we have previously demonstrated that mouse SOD1 encoding the fALS mutation G85R shows a high potential to aggregate [25]; and transgenic mice that express mouse SOD1 with this mutation develop ALS [27]. Mouse SOD1 normally possesses only 3 cysteines (positions 6, 57, 146) and encodes serine at position 111. Mouse and human SOD1 differ at 25 amino acid positions, and thus it would seem that some elements in the mouse sequence obviate the need for cysteine at residue 111 in promoting aggregation.

In the present work we generated chimeric human/mouse SOD1 constructs to examine how sequences surrounding cysteine 111, as well as sequences located more distally to cysteine 111, may modulate aggregation in proteins derived from the two species. We demonstrate that chimeric SOD1 proteins in which amino acids 42–50 (4thβ-strand) and 109–123 (7thβ-strand) are of human origin show the highest potential to aggregate. In conjunction with studies by Seetharaman and colleagues (accompanying manuscript), sequence elements in SOD1 that may be important sites of non-native interactions in the formation of multimeric aggregate structures are identified.

Materials and Methods

Construction of SOD1 Expression Vectors

All SOD1 variants were expressed using the pEF-BOS vector [28]. The cDNA genes for chimeric mouse/human (N-M/C-H) and human/mouse (N-H/C-M) SOD1 of wild-type sequence (WT) were synthesized by Genescript (Piscataway, NJ, USA). Experimental and fALS associated mutations in human, mouse, and chimeric N-H/C-M SOD1 cDNAs were generated by standard PCR strategies with oligonucleotides that introduce the specific point mutations. All cDNA genes and pEF-BOS vectors encoding these cDNAs were verified by sequencing prior to their use in experimentation.

Tissue Culture Transient Transfection

HEK 293-FT cells were cultured in 60-mm poly-D lysine coated dishes. Upon reaching 95% confluency, cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and then harvested after 24 hours as previously described [25].

SOD1 Aggregation Assay by Differential Extraction

The procedures used to assess SOD1 aggregation by differential detergent extraction and centrifugation were similar to previous descriptions [12, 25]. Cells were lysed in buffers containing non-ionic detergent (NP40) using high speed centrifugation to separate soluble (S1) and insoluble proteins. The initial insoluble fraction (P1) is re-extracted with buffers containing NP40 to generate the final insoluble fraction (P2). Protein concentrations of S1 and P2 were measured by BCA method as described by the manufacturer (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA).

Immunoblotting

Standard sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed in 18% Tris-Glycine gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Samples were boiled for 5 minutes in Laemmli sample buffer prior to electrophoresis [29]. Immunoblots were probed with a rabbit polyclonal antibody termed m/hSOD1 at dilutions of 1:2500. The m/h SOD1 antibody is a peptide antiserum that recognizes amino acids 124–136 (conserved between mouse and human SOD1 proteins) [5].

Quantitative Analysis of Immunoblots

Quantification of the SOD1 protein in detergent-insoluble and detergent-soluble fractions was performed by measuring the band intensity of SOD1 in each lane using a Fuji Imaging system (FUJIFILM Life Science, Stamford, CT USA). The untransfected control served as background. SOD1 aggregation propensity is the ratio of the band intensity in the detergent-insoluble fraction to that of the detergent-soluble fraction. The mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) were calculated for the aggregation propensity of each sample in each experiment (see Supplemental Materials, Table 1). A homoscedastic student’s T-test was used to calculate significance (see Supplemental Materials, Tables 2-4).

Results

Human and mouse SOD1 mutated to encode the G85R fALS mutation show high propensities to aggregate in cell culture [25], and both mutants cause hindlimb paralysis when expressed in mice [27, 30]. Human and mouse SOD1 differ at 25 amino acids, but position 111, which encodes cysteine in human SOD1 and serine in mouse SOD1, has been of particular interest [25]. Note that a serine encoded at amino acid 111 is the more conserved residue at this position in mammals [4]. In human SOD1, when amino acid 85 encodes the fALS mutation (G85R) and amino acid 111 encodes a serine (G85R/C111S), the aggregation potential is similar to the WT protein and much lower than when the G85R mutation is the only change to the human protein (Fig. 1)[also see [25]]. To determine whether this effect is unique to the serine, cysteine 111 was mutated to an alanine in the context of the G85R mutation. Vectors containing SOD1 with combined mutations at amino acids 85 (R; an fALS mutation) and 111 (S or A; experimental mutations) were expressed in HEK293-FT cells, and cell lysates were extracted in non-ionic detergent to isolate detergent-insoluble and detergent-soluble protein fractions. The G85R/C111S and the G85R/C111A mutants produced similar levels of detergent-insoluble protein (Fig. 1A). The amount of detergent-soluble material, representing stably folded protein, was similar in all mutants (Fig. 1B). The G85R mutant exhibits anomalous migration in SDS-PAGE, which results in the protein migrating slightly faster than expected for its molecular weight. Thus, for human SOD1 harboring a fALS mutation, substituting the cysteine residue at amino acid 111 for serine or alanine has a dramatic effect on the aggregation.

Figure 1.

Cysteine 111 plays an important role in SOD1 aggregation. Mutants were expressed in HEK293-FT cells, and aggregate levels were measured as described in Methods. UT, untransfected cells. WT, cells transfected with vectors containing WT SOD1 protein, which does not aggregate. G85R is a robustly aggregating fALS mutant and serves a positive control. SDS-PAGE was performed in the presence of reducing agent in an 18% Tris-Glycine gels. Immunoblots were probed with an antiserum recognizing a conserved region in mouse and human SOD1 (m/hSOD1). A. Detergent-insoluble protein fraction (20 μg protein). B. Detergent-soluble protein fraction (5 μg protein). Image is representative of 3 repetitions of this experiment.

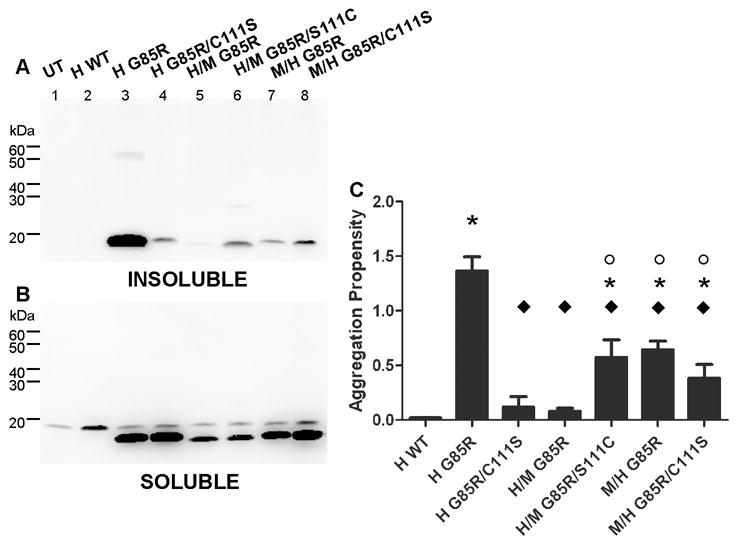

Chimeric human/mouse SOD1 cDNA constructs were created to map residues in human SOD1 that interact with cysteine 111 and promote aggregation. We created a recombinant SOD1 protein, in which amino acids 1–80 were encoded as human SOD1 and amino acids 81–153 were encoded as mouse SOD1 (N-H/C-M), and chimeric mouse/human proteins were constructed in the reverse order with 1–80 encoding mouse SOD1 and 81–153 encoding human SOD1 (N-M/C-H). In the context of these proteins, we introduced fALS mutations. Chimeric SOD1 genes were expressed in HEK293-FT cells and extracted in non-ionic detergent to identify insoluble aggregated mutant SOD1 protein. The chimeric proteins that encode WT sequence of human and mouse SOD1 (N-H/C-M WT and N-M/C-H WT) had aggregation propensities that were similar to the human WT protein (Fig. 2A, lanes 2, 6, 8; and Fig. 2C). Thus, the fusion of mouse and human sequence did not inherently induce aggregation. Mouse SOD1 migrates slightly faster than human SOD1 in SDS-PAGE. We observed the N-H/C-M SOD1 WT chimeras to migrate similar to mouse WT SOD1, whereas the N-M/C-H SOD1 WT chimeras migrated similar to human WT SOD1. Presumably slight differences in charge and SDS binding along the protein backbone cause these minor variations in migration rates. When the fALS mutation G85R was introduced into the N-H/C-M chimeric protein, very little detergent-insoluble protein was produced (Fig. 2A, lane 7); not differing from WT protein in propensity to aggregate (Fig. 2C). By contrast, the N-M/C-H G85R variant produced approximately the same level of detergent-insoluble protein as mouse SOD1-G85R (Fig. 2A, compare lanes 5 and 9; and Fig. 2C). Despite the differences in aggregation propensity, the levels of detergent-soluble SOD1 produced by the various constructs was consistent, indicating similar levels of expression for each construct (Fig. 2B). Thus, these chimeric proteins demonstrate that human and mouse protein sequences are not completely interchangeable in regards to promoting aggregation of SOD1; the N-H/C-M G85R variant exhibits a much lower propensity to aggregate than human SOD1-G85R, mouse SOD1-G85R, or N-M/C-HG85R.

Figure 2.

Differences in aggregation propensity between mouse and human SOD1 chimeric proteins. Mutants were expressed in HEK293-FT cells, and aggregate levels were measured as described in Methods. UT, untransfected cells. WT, cells transfected with vectors containing WT SOD1 protein, which does not aggregate. N-H/C-M-SOD1, human sequence between amino acids 1–80 and mouse sequence between 81–153 (abbreviated in panel as H/M). N-M/C-H-SOD1, mouse sequence between amino acids 1–80 and human sequence between 81–153 (abbreviated in panel as M/H). SDS-PAGE was performed in the presence of reducing agent in 18% Tris-Glycine gels. Immunoblots were probed with m/hSOD1 antiserum. A. Detergent-insoluble protein fraction (20 μg protein). B. Detergent-soluble protein fraction (5 μg protein). C. Relative aggregation propensity is a function of the amount of SOD1 found in the detergent-insoluble fraction compared to the detergent-soluble fraction. The graph represents the mean (± SEM (error bars)) of at least three different experiments (also see Supplemental Materials, Table 1). (*) = Statistically different from all wild-type variants (H WT, N-H/C-M WT, N-M/C-H WT. (°) = Statistically different from N-H/C-M G85R. (◆) = Statistically different from human G85R (for p values see Supplemental Materials, Table 2).

Due to the apparent importance of amino acid 111 in human SOD1 aggregation, we used chimeric proteins to examine how this residue influences aggregation. The chimeric protein N-H/C-M G85R encodes a serine at amino acid 111 and displays an aggregation propensity that is similar to human G85R/C111S, which is similar to wild-type human SOD1 (Fig. 3A, lanes 4 and 5). To more closely examine the role of cysteine 111 in SOD1 aggregation, amino acid 111 of N-H/C-M SOD1-G85R and N-M/C-H SOD1-G85R was engineered to encode either cysteine or serine (termed N-H/C-M G85R/S111C and N-M/C-H G85R/C111S). Encoding a cysteine at amino acid 111 in the N-H/C-M G85R mutant (N-H/C-M G85R/S111C) resulted in a modest increase in aggregate formation (Fig. 3A, lane 6), with the measured aggregation propensity being significantly different from N-H/C-M G85R (Fig. 3C) but less than that of human SOD1-G85R (Fig. 3C). In the converse experiment, when amino acid 111 encoded a serine in the N-M/C-H SOD1-G85R mutant (N-M/C-H G85R/C111S), the aggregation levels of this mutant decreased slightly but did not plummet to the level of wild-type human SOD1 (Fig. 3A, lane 8). Indeed, the measured aggregation propensity was not significantly different from N-M/C-H G85R (Fig. 3C). These findings indicate that when the N-terminus of the chimeric protein is human, aggregation is heightened when residue 111 is cysteine. However, when the N-terminus of the chimeric protein is mouse SOD1, aggregation is similar whether position 111 encodes serine or cysteine. Thus we conclude that sequences in the N-terminus of SOD1 may be interacting with sequences that include cysteine 111 in promoting aggregation and that this interaction is particularly important in the aggregation of human SOD1.

Figure 3.

Sequence surrounding cysteine 111 of human SOD1 influences aggregation. Mutants were expressed in HEK293-FT cells, and aggregate levels were measured as described in Methods and the legend to Fig. 3. A. Detergent-insoluble protein fraction (20 μg protein). B. Detergent-soluble protein fraction (5 μg protein). C. Graph of the mean aggregation propensity [±SEM (error bars)] for each mutant from at least three different experiments. (*) = Statistically different from all wild-type variants (H WT, N-H/C-M WT, N-M/C-H WT). (°) = Statistically different from N-H/C-M G85R. (◆) = Statistically different from human G85R (for p values see Supplemental Materials, Table 2).

Because restoring residue 111 in N-H/C-M SOD1-G85R to cysteine did not fully restore the aggregation propensity of the protein to that of human SOD1-G85R, we asked whether cysteine 111 works in concert with other neighboring residues to mediate aggregation by humanizing specific amino acids or blocks of sequence in the N-H/C-M SOD1-G85R construct. Humanizing the region encoding amino acids 109–123 (E109D, S111C, M117L, and Q123A) in the N-H/C-M G85R mutant (termed N-H/C-M G85R/δ 109–123) resulted in a protein that robustly aggregated in cell culture (Fig. 4A, lane 5). The measured aggregation propensity of this mutant was similar to human G85R (Fig. 4C). Thus, this region appears to be important for aggregation when the N-terminal half of the protein is of human origin. To determine whether a specific amino acid in this region (amino acids 109–123) is responsible for enhancing aggregation, each residue was substituted for the corresponding human residue individually (e.g.: N-H/C-M G85R/E109D/S111C, N-H/C-M G85R/S111C/M117L, N-H/C-M G85R/S111C/Q123A). Each of these mutants had an aggregation propensity similar to N-H/C-M G85R/S111C (Fig. 4A, lanes 6–8; and Fig. 4C). Although there was some variation, the amount of soluble SOD1 produced by each variant was similar, indicating all were efficiently expressed (Fig. 4B). Thus, we conclude that the region between amino acids 109–123 functions as a unit in promoting aggregation, with cysteine 111 being a critically important residue but not the only residue involved.

Figure 4.

Sequence elements in residues 42–50 and 109–123 of human SOD1 are important for aggregation. Mutants were expressed in HEK293-FT cells, and aggregate levels were measured as described in Methods and the legend to Fig. 3. A. Detergent- insoluble protein fraction (20 μg protein). B. Detergent-soluble protein fraction (5 μg protein). C. Graph of the mean aggregation propensity [±SEM (error bars)] for each mutant from at least three different experiments. (*) = Statistically different from all wild-type variants (H WT, N-H/C-M WT, N-M/C-H WT). (°) = Statistically different from N-H/C-M G85R. (◆) = Statistically different from human G85R (for p values see Supplemental Materials Table 2).

In the normally folded SOD1 protein, residues in the 7th β-strand (residues 116–120), are in close proximity to residues 41–48, which encompass in 4th β-strand [31]. In the N-H/C-M G85R mutant, the 4th and 7thβ-strands are not matched to species, but in the highly aggregating N-H/C-M G85R/δ 109–123 mutant the 4th and 7thβ-strands are both of human origin. To determine whether the 4th and 7thβ-strands interact in some type of species-specific manner, we re-engineered residues 42–50 of N-H/C-M-SOD1-G85R to encode the mouse sequence (L42Q, E49Q, and F50Y), creating a mutant in which the residues between 42 and 50 are of mouse origin and the residues between 109 and123 are of human origin (termed N-H/C-M G85R/δ 42–50/δ 109–123). This recombinant mutant SOD1 protein produced much less detergent-insoluble protein (Fig. 4A, lane 9) with an aggregation propensity similar to WT (Fig. 4C). This finding strongly suggests that in human SOD1 there are sequence elements in the 4th and 7thβ-strands that play a critical role in the aggregation of mutant human SOD1.

To determine whether these same elements are equally critical in the aggregation of mouse SOD1, we altered the N-H/C-M SOD1-G85R construct such that residues 42–50 were converted to the mouse SOD1 sequence (termed N-H/C-M SOD1-G85R/Δ42–50). Somewhat surprisingly, this mutant produced very little detergent-insoluble SOD1 aggregates (Fig. 4A, lane 10). N-H/C-M SOD1-G85R/Δ42–50, in which the 4th and 7thβ-strands encoded mouse SOD1, had a low propensity to aggregate, similar to WT (Fig. 4C). The amount of detergent-soluble SOD1 was similar in all the mutants examined (Fig. 4B). Thus, it appears that matching the species origin of the 4th and 7thβ-strands in the context of mouse SOD1 is not sufficient to restore the aggregation propensity to the level of native mouse SOD1-G85R. We conclude that additional sequence elements in mouse SOD1 play a substantial role in mediating aggregation.

To determine whether the sequence elements in human SOD1 that we have identified as important for the aggregation of the G85R mutant apply more broadly, fALS mutations located at the beginning of the protein (A4V) or at the end of the protein (V148G) were introduced into the chimeric N-H/C-M SOD1 protein. N-H/C-M A4V produced significantly less aggregates than human A4V (Fig. 5A, lanes 2 and 4; and Fig. 5C); however, the aggregation propensity of N-H/C-M A4V was greater than that of WT protein. Humanizing amino acids 109–123 in the N-H/C-M A4V protein (termed N-H/C-M A4V/δ 109–123) produced a robustly aggregating mutant that was significantly different from N-H/C-M A4V and similar in its propensity to aggregate to human SOD1-A4V and much higher than mouse SOD1-A4V (Fig. 5A, compare lanes 2, 3, and 5; and Fig. 5C). A similar pattern of aggregation was observed with the V148G mutation, whereby the N-H/C-M variant aggregated at low levels and humanizing 109–123 enhanced aggregation to the levels of human SOD1 encoding the V148G mutation (Fig. 5A, lanes 6–9, and Fig. 5C). Thus, the modulating effect of sequence elements within amino acids 109–123 of human SOD1 aggregation function independently of the location of the fALS mutation.

Figure 5.

The aggregation propensity of fALS mutations at N- and C-terminal locations is modulated by sequence elements in residues 109–123. Mutants were expressed in HEK293-FT cells, and aggregate levels were measured as described in Methods and the legend to Fig. 3. A) Detergent-insoluble protein fraction (20 μg protein). B) Detergent-soluble protein fraction (5 μg protein). C) Graph of the mean aggregation propensity [±SEM (error bars)] for each mutant from at least three different experiments. (●) = Statistically different from H A4V. (Δ) = Statistically different from N-H/C-M A4V/δ 109–123. (□) = Statistically different from H V148G. (■) = Statistically different from N-H/C-M V148G/δ 109–123 (for p values see Supplemental Materials, Tables 3 and 4).

Discussion

Our study was designed to identify regions in the human SOD1 protein that modulate aggregation of mutant SOD1 in an effort to improve our understanding of the role of cysteine 111 in modulating aggregation [24, 25]. Intriguingly, mouse SOD1 normally encodes a serine at position 111 and when mouse SOD1 is mutated to encode human fALS mutations, we observe robust aggregation [25]. To identify sequence elements in human and mouse SOD1 that account for the differing dependencies on a cysteine at position 111 for aggregation, we generated a series of chimeric SOD1 proteins that combine human and mouse SOD1 sequence (data summarized in Fig. 6). From this approach we identified 2 sequence elements in human SOD1 between residues 42–50 (which includes 4thβ-strand) and 109–123 (which includes elements of Loop VI, all of the 7thβ-strand and elements of Loop VII) that seem to act in concert to promote aggregation of human SOD1. This putative interaction between these sequence elements is similar for fALS mutants located at the N-terminus (A4V), middle (G85R), and C-terminus (V148G) of the protein. Thus, for human SOD1 we conclude that the folding pathway that results in the formation of large, detergent-insoluble, aggregates of mutant SOD1 involves protein:protein interactions that are optimal when residues 42–50 and 109–123 are of human origin.

Figure 6.

Summary of chimeric protein aggregation. Top. Sequences of human and mouse SOD1. Differences in amino acid sequence, total of 25, are marked by bold font. Cu binding sites are noted by blue font (His 46, 46, 63,120). Zn binding sites are underlined (His 63, 71, 80, Asp 83). Cysteines 57 and 146 form the intramolecular disulfide bond. Sequences composing 3 of the key chimeric SOD1 constructs are noted in boxes. Bottom. Diagrams of the chimeric proteins used in this study are represented on the left panel. Blue, human SOD1 sequence. Red, mouse SOD1 sequence. Black, highly conserved between human and mouse. The graph represents the mean [±SEM (error bars)] of at least three different experiments for each mutant (also see Supplemental Materials, Table 1).

Residues 42–50 and 109–124 of SOD1 contain elements within these sequences are normally aligned adjacent to one another in the mature folded protein; the 4th and 7th b-strands lie adjacent to one another in the natively folded protein [31]. Residues in both of these elements contribute to the formation of the normal dimer (Fig. 6) and participate in the binding of Cu. Shaw and colleagues reported that sequence elements overlapping with the two elements we study here [including the dimer interface (residues 50–53) and a region containing β-strand 7 and Loop VII (residues 117–144) of mutant SOD1] are more accessible to solvent in mutant human SOD1 as compared to the normal human enzyme [32]. This finding indicates that fALS mutations destabilize some aspect of normal structure so that residues 42–50 and 109–123 become more accessible to solvent. Additionally, three of the four copper binding sites are located in these elements (His 46, 48, and 120; the 4th ligand is His 63). Interestingly, dimer formation and copper binding greatly enhance the thermal stability in the WT protein, which accounts for a protein that is stable in 1% SDS and 8M urea [33]. However, in several previous studies we have not found an association between lack of Cu-binding and aggregation of mutant SOD1. Mutants that have a lower affinity for Cu do not generally show a higher propensity to aggregate as compared to mutants that retain high affinity for Cu [2, 12].

It is also important to note that there are several fALS associated mutations that occur within the sequences encompassing residues 42–50 and 109–123. Mutations occur at positions 43, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, and 118 (http://alsod.iop.kcl.ac.uk). One might predict that if there are interactions between residues 42–50 and 109–123 that are critical in promoting aggregation, then such interactions might be disturbed by fALS mutation and that such mutants might be less prone to aggregate. The aggregation propensities of several mutants that occur in these regions have been examined previously in the 293 cell model in which the aggregation potential of the A4V mutant serves as a bench mark [2]. Although the aggregation potential of the H43R mutant is similar to the A4V mutant, the aggregation potential of mutations H46R, H48Q, C111Y, and I113T were calculated to be more than 50% lower. However, there were examples of mutants with aggregation potentials more 50% lower than A4V that were located outside of residues 42–50 and 109–123, including E21G, E21K, G37R, D101N, D125H, S134N, V148I, L144F, and L144S. Notably, in the 40 plus mutants that were examined by Prudencio et al [2], the majority showed aggregation potentials similar to or higher than the A4V mutant. Thus, although the sampling of 5 mutants at 4 positions within the 42–50 and 109–123 regions is incomplete, the trend is for mutations in these regions to show lower aggregation potentials.

The slower aggregation of chimeric mouse/human SOD1 proteins may be related mechanistically to the effect that co-expression of WT mouse SOD1 has on the aggregation of fALS human SOD1 [34]. Co-expression of WT mouse SOD1 with mutant human SOD1 substantially slows the aggregation the human protein [34]. Moreover, unlike human WT SOD1, mouse WT SOD1 does not appear to be capable of co-aggregating with mutant human SOD1 [34]. Presumably, there is some aspect of the human and mouse SOD1 structures that are incompatible with assembly to multimeric structures. The chimeric SOD1 proteins we have created here appear to reproduce this incompatibility and through mutagenesis we map the amino acids involved to residues between 42–50 and 109–123 of human and mouse SOD1.

The accompanying report by Seetharaman and colleagues describes the crystal structures of mouse SOD1 and two of the chimeric constructs described here, N-M/C-H-WT, and N-H/C-M-WT SOD1 [35]. Their report documents subtle differences in the structures of these proteins but all show an expectedly high resemblance to WT human SOD1. Importantly, the chimeric proteins did not show obvious structural alterations around the 4th and 7th beta strands, leaving us presently unable to easily explain how these residues modulate the aggregation of mutant human SOD1. In previous work, the crystal structure of apo SOD1-H46R and SOD1-H80R revealed subunits of mutant protein that were aligned in filamentous arrays in which β-strands 5 and 6 become unprotected allowing non-native interactions between SOD1 subunits [36]. Similar structures have been observed in crystal structures of the SOD1-S134N [37]. Within these filamentous arrays, non-native interactions between subunits occur between residues in the 42–50 and 109–123 sequence elements (see the accompanying report by Seetharaman [35]). Thus, it seems that we have corroborating evidence that interactions between these residues of SOD1 could mediate multimerization of mutant SOD1. Together, the present study and the accompanying work identify sequences within SOD1 that may be critical sites of initial interaction between SOD1 subunits that initiate the formation of multimeric complexes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sai Seetharaman and P. John Hart for continued collaboration and invaluable insight into the structural aspects of SOD1 and the SOD1 chimeras described in this paper. We thank Hilda Brown for advice and assistance in generating the SOD1 expression constructs. We are grateful to Mercedes Prudencio and Guilian Xu for thoughtful discussion and advice throughout this study. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P01 NS049134 (Project 3 to DRB).

Abbreviations

- SOD1

superoxide dismutase 1

- fALS

familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- WT

wild-type

- N-M/C-H

mouse/human

- N-H/C-M

human/mouse

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rosen DR, Siddique T, Patterson D, Figlewicz DA, Sapp P, Hentati A, Donaldson D, Goto J, O'Regan JP, Deng HX, Rahmani Z, Krizus A, McKenna-Yasek D, Cayabyab A, Gaston SM, Berger R, Tanzi RE, Halperin JJ, Herzfeldt B, Van den Bergh R, Hung WY, Bird T, Deng G, Mulder DW, Smyth C, Laing NG, Soriano E, Pericak-Vance MA, Haines J, Rouleau GA, Gusella JS, Horvitz HR, Brown RH., Jr Nature. 1993;362:59–62. doi: 10.1038/362059a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prudencio M, Hart PJ, Borchelt DR, Andersen PM. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3217–3226. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valentine JS, Hart PJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3617–3622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730423100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang J, Xu G, Borchelt DR. J Neurochem. 2006;96:1277–1288. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borchelt DR, Lee MK, Slunt HH, Guarnieri M, Xu ZS, Wong PC, Brown RH, Jr, Price DL, Sisodia SS, Cleveland DW. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8292–8296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Potter SZ, Valentine JS. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2003;8:373–380. doi: 10.1007/s00775-003-0447-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayward LJ, Rodriguez JA, Kim JW, Tiwari A, Goto JJ, Cabelli DE, Valentine JS, Brown RH., Jr J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15923–15931. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112087200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishida CR, Butler Gralla E, Selverstone Valentine J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9906–9910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiedau-Pazos M, Goto JJ, Rabizadeh S, Gralla EB, Roe JA, Lee MK, Valentine JS, Bredesen DE. Science. 1996;271:515–518. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ratovitski T, Corson LB, Strain J, Wong P, Cleveland DW, Culotta VC, Borchelt DR. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1451–1460. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.8.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tiwari A, Hayward LJ. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5984–5992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210419200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J, Slunt H, Gonzales V, Fromholt D, Coonfield M, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Borchelt DR. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2753–2764. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J, Xu G, Li H, Gonzales V, Fromholt D, Karch C, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Borchelt DR. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2335–2347. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karch CM, Prudencio M, Winkler DD, Hart PJ, Borchelt DR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7774–7779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902505106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J, Farr GW, Zeiss CJ, Rodriguez-Gil DJ, Wilson JH, Furtak K, Rutkowski DT, Kaufman RJ, Ruse CI, Yates JR, III, Perrin S, Feany MB, Horwich AL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1392–1397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813045106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Son M, Puttaparthi K, Kawamata H, Rajendran B, Boyer PJ, Manfredi G, Elliott JL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6072–6077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610923104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Son M, Fu Q, Puttaparthi K, Matthews CM, Elliott JL. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;34:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watanabe M, Dykes-Hoberg M, Cizewski C, Price VDL, Wong PC, Rothstein JD. Neurobiol Dis. 2001;8:933–941. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnston JA, Dalton MJ, Gurney ME, Kopito RR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12571–12576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220417997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jonsson PA, Ernhill K, Andersen PM, Bergemalm D, Brannstrom T, Gredal O, Nilsson P, Marklund SL. Brain. 2004;127:73–88. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang J, Xu G, Slunt HH, Gonzales V, Coonfield M, Fromholt D, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Borchelt DR. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;20:943–952. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deng HX, Shi Y, Furukawa Y, Zhai H, Fu R, Liu E, Gorrie GH, Khan MS, Hung WY, Bigio EH, Lukas T, Dal Canto MC, O'Halloran TV, Siddique T. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7142–7147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602046103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jonsson PA, Graffmo KS, Andersen PM, Brannstrom T, Lindberg M, Oliveberg M, Marklund SL. Brain. 2006;129:451–464. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cozzolino M, Amori I, Pesaresi MG, Ferri A, Nencini M, Carri MT. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:866–874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705657200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karch CM, Borchelt DR. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:13528–13537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800564200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chattopadhyay M, Durazo A, Sohn SH, Strong CD, Gralla EB, Whitelegge JP, Valentine JS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18663–18668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807058105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ripps ME, Huntley GW, Hof PR, Morrison JH, Gordon JW. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:689–693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mizushima S, Nagata S. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:5322. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.17.5322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laemmli UK. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bruijn LI, Becher MW, Lee MK, Anderson KL, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Sisodia SS, Rothstein JD, Borchelt DR, Price DL, Cleveland DW. Neuron. 1997;18:327–338. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80272-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parge HE, Hallewell RA, Tainer JA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6109–6113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.6109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaw BF, Lelie HL, Durazo A, Nersissian AM, Xu G, Chan PK, Gralla EB, Tiwari A, Hayward LJ, Borchelt DR, Valentine JS, Whitelegge JP. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:8340–8350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707751200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lyons TJ, Gralla EB, Valentine JS. Met Ions Biol Syst. 1999;36:125–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prudencio M, Durazo A, Whitelegge JP, Borchelt DR. J Neurochem. 2009;108:1009–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05839.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seetharaman SV, Taylor AB, Holloway S, Karch CM, Borchelt DR, Hart PJ. Biochemistry. 2009 submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antonyuk S, Elam JS, Hough MA, Strange RW, Doucette PA, Rodriguez JA, Hayward LJ, Valentine JS, Hart PJ, Hasnain SS. Protein Sci. 2005;14:1201–1213. doi: 10.1110/ps.041256705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elam JS, Taylor AB, Strange R, Antonyuk S, Doucette PA, Rodriguez JA, Hasnain SS, Hayward LJ, Valentine JS, Yeates TO, Hart PJ. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:461–467. doi: 10.1038/nsb935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.