Abstract

A large proportion of the nitrate (NO3 −) acquired by plants from soil is actively transported via members of the NRT families of NO3 − transporters. In Arabidopsis, the NRT1 family has eight functionally characterised members and predominantly comprises low-affinity transporters; the NRT2 family contains seven members which appear to be high-affinity transporters; and there are two NRT3 (NAR2) family members which are known to participate in high-affinity transport. A modified reciprocal best hit (RBH) approach was used to identify putative orthologues of the Arabidopsis NRT genes in the four fully sequenced grass genomes (maize, rice, sorghum, Brachypodium). We also included the poplar genome in our analysis to establish whether differences between Arabidopsis and the grasses may be generally applicable to monocots and dicots. Our analysis reveals fundamental differences between Arabidopsis and the grass species in the gene number and family structure of all three families of NRT transporters. All grass species possessed additional NRT1.1 orthologues and appear to lack NRT1.6/NRT1.7 orthologues. There is significant separation in the NRT2 phylogenetic tree between NRT2 genes from dicots and grass species. This indicates that determination of function of NRT2 genes in grass species will not be possible in cereals based simply on sequence homology to functionally characterised Arabidopsis NRT2 genes and that proper functional analysis will be required. Arabidopsis has a unique NRT3.2 gene which may be a fusion of the NRT3.1 and NRT3.2 genes present in all other species examined here. This work provides a framework for future analysis of NO3 − transporters and NO3 − transport in grass crop species.

Introduction

Nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) in plants is determined by the efficiency with which the plant acquires and uses nitrogen. Nitrate (NO3 −) is the primary nitrogen source for most plants in agricultural soils; cereal crops, however, access only 33–50% on average of the NO3 − applied to the soil by farmers [1], [2]. In order to improve this efficiency a more complete understanding of the transport of NO3 − from the soil to the plant and within the plant itself is required. An important first step towards improving the NO3 − uptake capacity and the NUE of crop plants would be characterisation of the transporters responsible for NO3 − transport. Either the expression of the relevant genes or else the function of the proteins encoded by the genes could then be manipulated through traditional plant breeding or genetic engineering in order to improve NO3 − uptake characteristics. With this goal in mind, the aim of this research was to identify the NO3 − transporters in grass species.

The transport of NO3 − and the transporters involved in this process have best been characterised in Arabidopsis due both to its amenability to physiological analyses and availability of genetic resources. The transport of NO3 − is mediated largely by members of the NRT gene families which have recently been reviewed [3]. The Arabidopsis genome contains 53 NRT1(PTR) family genes [3]. Only AtNRT1.1 to AtNRT1.8, however, have functional analyses indicating that these proteins do indeed transport NO3 −. The NRT1 family comprises predominantly low-affinity NO3 − transporters, with the exception of AtNRT1.1 which appears to mediate dual-affinity NO3 − transport [4], [5] based on phosphorylation status of the amino acid residue T101 [6]. A recent study indicated that AtNRT1.1 may also function as an NO3 − sensor [7]. The expression of AtNRT1.2 is constitutive and located predominantly in the root epidermis indicating that the encoded transporter may also be involved in NO3 − uptake from the soil [8]. The expression of AtNRT1.3 in roots is repressed by exposure to NO3 − and is induced by NO3 − deprivation; its functional role, however, remains less clear [9], [10]. AtNRT1.4 is expressed primarily in the leaf petiole and appears to be involved in NO3 − storage [11]. AtNRT1.5 appears to mediate NO3 − efflux and to have a role in the loading of NO3 − into the xylem for transport to the shoot [12]. AtNRT1.6 is involved in transporting NO3 − from maternal tissue to developing embryos [13]. AtNRT1.7 has been identified as playing role in the remobilisation of NO3 − from older to younger leaves through facilitating phloem loading [14]. Very recently Li et al [15] have shown that AtNRT1.8 is responsible for retrieving NO3 − from the xylem parenchyma in the roots and shoots, thus working synergistically with AtNRT1.5 to control long-distance NO3 − transport.

The NRT2 family are high-affinity NO3 − transporters comprising NO3 − inducible and constitutively expressed members [3]. The best characterised members are AtNRT2.1 and AtNRT2.2, which are located next to each other on chromosome 1 and appear to encode proteins with similar function [16]. AtNRT2.1 seems to be more crucial for NO3 − influx and is expressed in the root cortex and epidermis [17]. Both AtNRT2.1 and AtNRT2.2, however, are inducible by provision of NO3 − to NO3 − starved plants [10], and compensate for one another in that expression of either increases when the other is reduced [16]. Little is known about AtNRT2.3 other than its expression may increase and decrease in cycles over the life cycle in the roots and shoots (mostly shoot) [9], [10]. AtNRT2.4 is expressed predominantly in the root, and expression appears to decrease following exposure of plants to NO3 − [9], [10]. Similarly, AtNRT2.5 is expressed in the root and shoot (mostly root) and is repressed by the provision of NO3 − [9], [10]. The expression of AtNRT2.6 remains relatively unchanged in roots and shoots (mostly root) following exposure of plants to NO3 − [9], [10]. AtNRT2.7 appears to have a role in storage of NO3 − in seeds [18].

The NRT3 genes in Arabidopsis play a role in NO3 − transport through regulating the activity of NRT2 genes, but are not themselves transporters [19], [20]. The two NRT3 genes appear to be closely related, but NRT3.1 (NAR2.1) appears to play the more significant role in high-affinity NO3 − uptake [20]. Although the recent annotation of the Arabidopsis genome has indicated that AtNRT3.2 gene is larger than originally published [20], the significance of this fact is unknown (http://www.arabidopsis.org/).

Here, bioinformatic analyses are presented of the NRT1, NRT2 and NRT3 gene families in the four fully sequenced grass genomes of rice [21], [22], [23], Brachypodium [24], maize [25] and sorghum [26]. Also included is an analysis of poplar as a further fully sequenced dicot species [27], with the purpose of strengthening observations made on the dichotomy between Arabidopsis and the grass species. The analyses were limited to fully sequenced genomes to ensure completeness and to increase the utility of the work for informing further research into NO3 − transporters in grass species. The evolution from a common ancestor of the four species studied is such that they provide a good indication of the diversity of genomes within the grass species; maize and sorghum are the most closely related, having diverged an estimated 12 million years ago [24]. Also, in order to clarify past identification of the relevant genes and to provide a standardised framework for future researchers, a nomenclature for the grass NRT genes is presented.

Results

A commonly accepted, extensively used and well documented method for the determination of genes that share a common evolutionary ancestor (orthologues, paralogues) across two genomes is the reciprocal best hit (RBH) [28], [29]. The RBH approach assumes that orthologous sequences hit to each other as the best scoring hit in a pairwise search between two genomes. There are however, limitations in the RBH method; it does not take parology into account and the highest scoring protein reported by BLAST is often not the nearest phylogenetic neighbour (high false negative rate) [30]. In this study we elected to use the RBH method over other orthology detection strategies due to its high stringency and success in identifying orthologues with a low false positive rate [31], [32]. To overcome the above mentioned shortcomings, a modified RBH, not restricted to the top hits alone and extended to include steps of refinement and validation was used (see Materials and Methods).

NRT1 family

As the genetic sequence(s) or protein motif(s) that separate the NRT1 genes from the PTR genes (the protein products of which transport peptides) are unknown, the analysis here was limited to determining putative grass orthologues of eight functionally characterised NRT1 genes (Table S1). Results from our analyses identified grass orthologues of AtNRT1.2, AtNRT1.3 and AtNRT1.4. However, for the remaining five members, a lack of resolution compounded by the analysis of only a subset of the 53 NRT1(PTR) genes and the complexity of ancestral events, rendered clear orthologous relationships between dicots and monocots, unattainable.

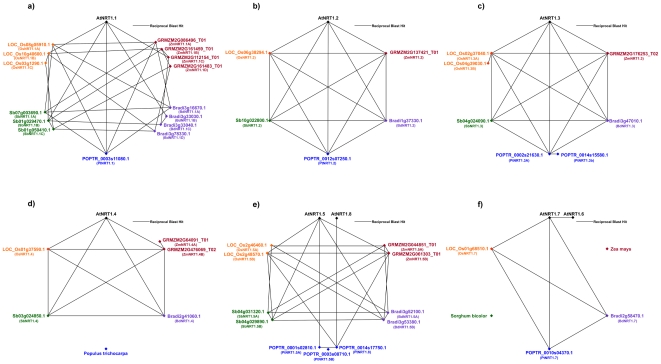

RBH BLASTp E values in both forward and reverse direction for all eight NRT1 genes was less than 10−139, with AtNRT1.1 – AtNRT1.5 and AtNRT1.8 showing greater sequence similarity to their grass counterparts (E values ≤2×10−159, ≈60% to 65% sequence identity across ≥85% of the query sequence) than AtNRT1.6 and AtNRT1.7 (≈50% sequence identity across ≥80% of the query sequence). Furthermore, RBH analyses returned near identical hits to the grass genomes for AtNRT1.5 and AtNRT1.8 as well as for AtNRT1.6 and AtNRT1.7. Graphical representation of the dicot – monocot RBH analysis can be seen in Figure S1. All-against-all RBH results for the NRT1 family is illustrated in Figure 1 (A–F).

Figure 1. NRT1 reciprocal BLAST polygons.

Reciprocal best hits are connected by black lines, for Arabidopsis (black), maize (red), Brachypodium (purple), poplar (blue), sorghum (green) and rice (orange). Results are depicted for (A) AtNRT1.1, (B) AtNRT1.2, (C) AtNRT1.3, (D) AtNRT1.4, (E) AtNRT1.5 and AtNRT1.8 and (F) AtNRT1.7.

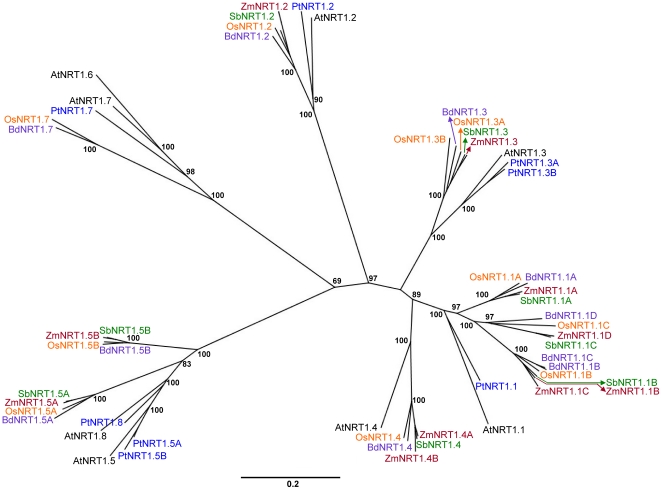

The phylogenetic tree of the eight Arabidopsis NRT1 genes and their identified grass homologues (Figure 2) depicts these findings clearly. For AtNRT1.1, there is one gene in poplar; in the grasses, however, there are three clades of closely related NRT1.1-like genes all containing at least one representative from each grass species (subclade 3 has an extra Brachypodium and maize gene). As the genes fall into three subclades, it is likely that gene duplication events gave rise to the three groups after the dicot-monocot split. For AtNRT1.2, AtNRT1.3 and AtNRT1.4 we see a much clearer picture, all cluster with a single clade of grass genes containing at least one member from the four grass species (rice and maize have an extra representative in the 1.3 and 1.4 clade respectively). Notably, poplar has no AtNRT1.4-like gene. AtNRT1.5 and AtNRT1.8 sit together with two and one poplar orthologues respectively and branch off from the main tree with two separate but complete clades of grass genes. Due to a slightly higher dicot – monocot RBH score for 1.5 over 1.8, the grass members of these two clades were named 1.5A and 1.5B. Upon close scrutiny of this branch, we found that the grass 1.5B clade had a nearer phylogenetic neighbour (a PTR gene – At5g19640) even though BLAST result scores were higher for 1.5 and 1.8. Since both clades sit equidistant from AtNRT1.5 (and neither more closely related to AtNRT1.8) an unambiguous assignment of orthology is not possible. Similarly, AtNRT1.6 and AtNRT1.7 sit together on the tree but unlike 1.5 and 1.8, 1.6 and 1.7 share one poplar orthologue and branch of the main tree with a single clade of grass genes missing both a maize and sorghum representative. Interestingly, the sorghum genome was found to contain a degraded pseudogene version that is related to NRT1.6 and NRT1.7, but this transcript is likely to be non-existent as no ESTs exist in any database.

Figure 2. Phylogenetic relationship of the NRT1 family.

Unrooted Neighbour-joining tree of NRT1 transporters in Arabidopsis (black), poplar (blue) and 4 grass species: rice (orange), sorghum (green), maize (red) and Brachypodium (purple). Bootstrap values from 1,000 replicates were used to estimate the confidence limits of the nodes. The scale bar represents a 0.2 estimated amino acid substitution per residue.

Additionally, eight monocot sequences - three maize, three sorghum and one each from rice and Brachypodium - were initially included in the potential orthologue list after RBH analysis but rejected after refinement and validation. These sequences were not included as they were clearly seen to be nearest neighbours to three Arabidopsis PTR genes (Figure S2) and this was authenticated in RBH scores.

NRT2 family

The seven members of the NRT2 family in Arabidopsis possessed a greater sequence similarity with each other than did the members of the NRT1 family (Table S1). RBH analysis of the NRT2 family returned identical results for AtNRT2.1 – AtNRT2.4 and AtNRT2.6 (E values = zero, 62% to 72% sequence identity across ≈90% of the query sequence). Results of the best hits for AtNRT2.5 were marginally lower (E values ranging between 10−162 and zero). Graphical representation of the dicot – monocot RBH analysis can be seen in Figure S1. All-against-all RBH results for the NRT2 family is illustrated in Figure 3.

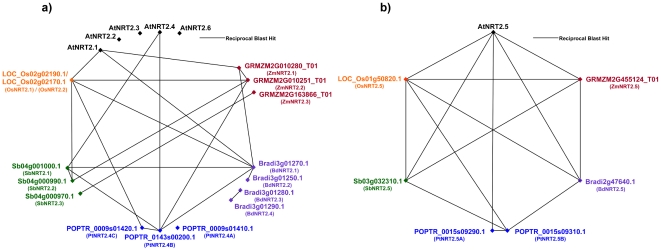

Figure 3. NRT2 reciprocal BLAST polygons.

Reciprocal best hits are connected by black lines, for Arabidopsis (black), maize (red), Brachypodium (purple), poplar (blue), sorghum (green) and rice (orange). Results are depicted for (A) AtNRT2.1 or AtNRT2.2 or AtNRT2.3 or AtNRT2.4 or AtNRT2.6 and (B) AtNRT2.5.

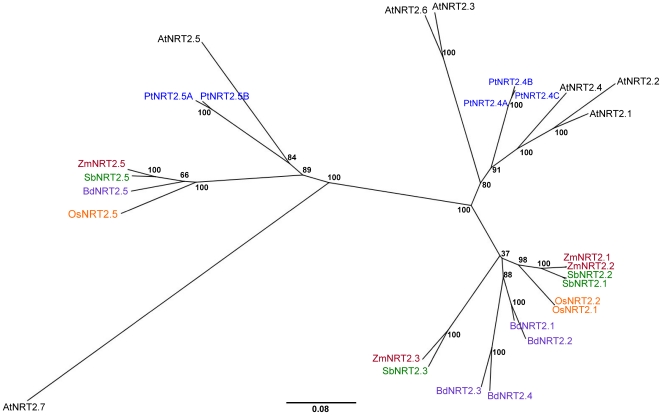

Results from analyses on the NRT2 family painted a particularly interesting picture, exclusive of NRT2.5, the grass NRT2 genes sit entirely separate on the phylogenetic tree from the Arabidopsis NRT2 genes (Figure 4). Three poplar sequences (named PtNRT2.4A, PtNRT2.4B and PtNRT2.4C due to a higher dicot – monocot RBH score with AtNRT2.4) cluster with the Arabidopsis sequences suggesting that the NRT2 genes developed primarily following the divergence of the monocots and dicots. Thus identification of a clear grass orthologues was only achieved for AtNRT2.5. A close investigation of the genomic localisation of these genes revealed clustering of the genes somewhat reminiscent of genes involved in disease resistance. AtNRT2.1 and AtNRT2.2 are neighbouring genes in opposing orientation, AtNRT2.3 and AtNRT2.4 are tandem repeats and AtNRT2.6 (which peculiarly has the highest pairwise sequence similarity over all pairwise matches in the group, to AtNRT2.3–89%) was located on a completely separate chromosome to the others. Correspondingly, of the twelve related sequences in grass (2.1–2.4 in Figure 4), eleven are located in close proximity to another in their respective genomes. Maize has three genes related to this NRT2 branch, two of which are closely located on chromosome 4, the other gene being located on a separate chromosome (Figure S3). Similarly, sorghum has two closely located NRT2 genes with a third related gene located one gene to the upstream side of the closely located pair; this third related gene clusters in the phylogenetic tree with the third NRT2 gene from maize. Rice has a similar pair of closely located NRT2 genes (actually giving rise to the same protein sequence), while Brachypodium has two sets of closely located NRT2 genes which are immediately adjacent to each other. Interestingly, the pair of NRT2 genes found in each of the grass species is generally separated by a non-NRT2 gene. These non-NRT2 genes do not share any sequence similarity with one another, nor to any other functionally characterised proteins in the databases (BLASTx search against NCBI). The pairs of NRT2 genes in the grass species may have similar function to AtNRT2.1 and AtNRT2.2, although confirmation of this would require proper functional analysis. Analysis of the gene structure of the NRT2 genes showed that the dicot NRT2 genes all contain both exons and introns, while none of the grass NRT2 genes contain introns (Table S2); this would indicate an ancient divergence of the members of the NRT2 gene family.

Figure 4. Phylogenetic relationship of the NRT2 family.

Unrooted Neighbour-joining tree of NRT2 transporters in Arabidopsis (black), poplar (blue) and 4 grass species: rice (orange), sorghum (green), maize (red) and Brachypodium (purple). Bootstrap values from 1,000 replicates were used to estimate the confidence limits of the nodes. The scale bar represents a 0.08 estimated amino acid substitution per residue.

There is one distinct NRT2.5-like gene in each grass genome; poplar, however, has two copies. There are no NRT2.7-like genes in any of the grass genomes, or in poplar. AtNRT2.7 is the most diverged of all the NRT2 sequences.

NRT3 family

The NRT3 family in Arabidopsis contains two members, AtNRT3.1 and AtNRT3.2. These genes are not NO3 − transporters, but have been shown to be necessary for NO3 − transport through interaction with other NRT2 transporters. The grass genomes were analysed for orthologues to both of these Arabidopsis NRT3 genes.

Genome analysis revealed the NRT3 family is best represented by individual splice forms. For NRT3.2 three splice variants have been predicted giving rise to two different amino acid sequences (www.arabidopis.org, TAIR Acc# At4G24730) (Figure S4 and S5). In comparison to the 443 aa long protein encoded by the longest splice form (At4G24730.1, hereafter referred to as AtNRT3.2), the proteins translated from the other two splice forms (At4G24730.2 and At4G24730.3, which will be referred to as NRT3.2SF2/3) are 311aa in length, the first 281 aa being identical with that of the longest splice form. Furthermore, there is evidence (NCBI Acc# DQ492237) for another splice product from this locus, which gives rise to a protein of 209 aa overlapping with the C-terminal half of the longest splice form. This protein sequence (referred to here as NRT3.2CT) was described and compared to NRT3.1 by Okamoto et al [20], revealing that the two proteins share 61% amino acid sequence identity.

When the protein sequence of At4G24730.1 was used in BLAST searches it became apparent that in the other species in this study the N- and C terminal halves of At4G24730.1 are coded for by two distinct genes. Consequently, it was decided that the protein sequences of NRT3.2SF2/3 and NRT3.2CT would be used separately for orthology searches. Notably, three splice forms have been predicted for NRT3.1 but all three of these translate into the same protein (http://arabidopsis.org/servlets/TairObject?type=gene&name=AT5G50200.3).

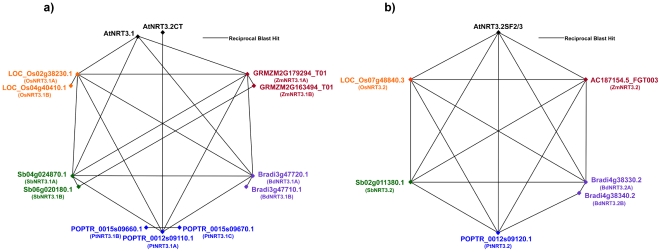

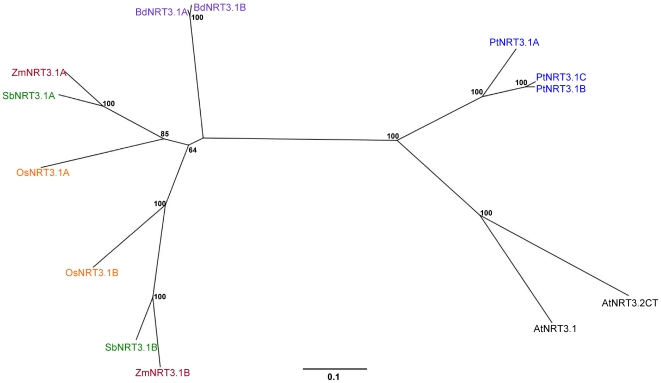

The results from RBH analysis were the same for both AtNRT3.1 and AtNRT3.2CT, identifying a pair of co-orthologous genes in maize, sorghum and rice and a tandem repeat in Brachypodium (Figure S1). Interestingly, poplar has three representative homologues of AtNRT3.1/3.2CT. BLAST E-values in both forward and reverse direction ranged between 10−27 and 10−32, with sequence identities ranging from 45% to 52% across 66% to 74% of the query sequence for AtNRT3.1 and ≈41% across ≈85% of the query sequence for AtNRT3.2CT (Graphical representation of the dicot – monocot RBH analysis can be seen in Figure S1). Closer investigation of the BLAST results to maize, rice and sorghum revealed a pattern; the genomic organisation of all these genes was well conserved between species. We postulate that either; a duplication event took place before the monocot – dicot split giving rise to co-orthologous pairs of genes of which one was eventually lost in Arabidopsis, or that, recent but separate duplication events have occurred in both the grass species and poplar, independent to Arabidopsis. RBH results for AtNRT3.1 and AtNRT3.2CT are illustrated in Figure 5A. Figure 6 shows the phylogenetic relationship of these protein sequences.

Figure 5. NRT3 reciprocal BLAST polygons.

Reciprocal best hits are connected by black lines, for Arabidopsis (black), maize (red), Brachypodium (purple), poplar (blue), sorghum (green) and rice (orange). Results are depicted for (A) AtNRT3.1 or AtNRT3.2CT and (B) AtNRT3.2 or AtNRT3.2SF2/3.

Figure 6. Phylogenetic relationship of the NRT3.1 or 3.2CT family.

Unrooted Neighbour-joining tree of NRT3.1 or 3.2CT family in Arabidopsis (black), poplar (blue) and 4 grass species: rice (orange), sorghum (green), maize (red) and Brachypodium (purple). Bootstrap values from 1,000 replicates were used to estimate the confidence limits of the nodes. The scale bar represents a 0.1 estimated amino acid substitution per residue.

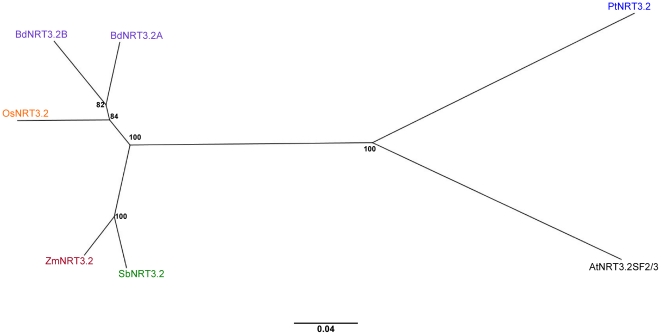

Similarly, AtNRT3.2 and AtNRT3.2SF2/3 produced the same RBH results, identifying a single NRT3 orthologue in maize, sorghum and rice and a tandem repeat in Brachypodium (Figure S1). BLAST E values in both forward and reverse direction ranged from 10−119 to 10−130, scoring ≈67% sequence identity. Alignment length differed between the two RBH analyses and was shown to be higher for NRT3.2SF2/3 (≈98%) compared with NRT3.2 (≈68%) (Graphical representation of the dicot – monocot RBH analysis can be seen in Figure S1). This difference can be explained by the fact that all BLAST hits landed within the aligned section between AtNRT3.2 and AtNRT3.2SF2/3 and never in the extended region of the former. For this reason, all subsequent investigations with respect to NRT3.2 were undertaken with only the AtNRT3.2SF2/3 splice form. Also similar to the NRT3.1 genes, close scrutiny of the AtNRT3.2SF2/3 RBH results revealed second best hits in the forward direction which were reciprocal in reverse for both maize (GRMZM2G337128_T01) and sorghum (Sb07g024380.1), but not in rice. E values, sequence identity and alignment length for these hits were found to be just below those of the top hits (E value 10−117, sequence identity ≈62% and alignment length of ≈99%). Although considered noteworthy, the maize and sorghum sequences were not used in any subsequent analysis. Figure 5B shows RBH results for AtNRT3.2 and AtNRT3.2SF2/3 and Figure 7 indicates the phylogenetic relationship of these protein sequences.

Figure 7. Phylogenetic relationship of the NRT3.2SF2/3 family.

Unrooted Neighbour-joining tree of NRT3.2SF2/3 family in Arabidopsis (black), poplar (blue) and 4 grass species: rice (orange), sorghum (green), maize (red) and Brachypodium (purple). Bootstrap values from 1,000 replicates were used to estimate the confidence limits of the nodes. The scale bar represents a 0.04 estimated amino acid substitution per residue.

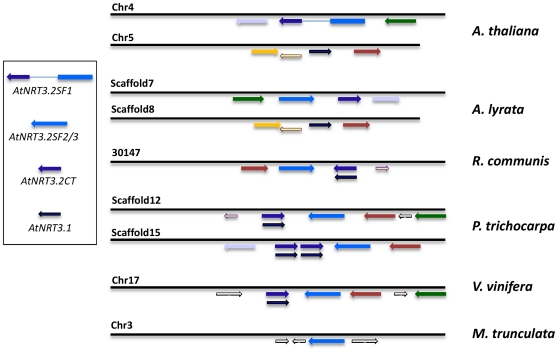

An attempt was made to explain our finding that At4G24730.1 appeared to be a fusion of what seemed to be two distinct genes in other species. This was done by comparing the genomic organisation of the NRT3 loci in Arabidopsis lyrata and in a further four dicot species each with a fully sequenced genome. As can be seen from Figure 8, only in Arabidopsis species is the organisation such that a di-cistronic mRNA can give rise to a fusion product through alternative splicing. In Ricinus communis, Vitis vinifera and Poplar trichocarpa the NRT3.2SP2/3 gene and the NRT3.2CT gene are encoded on the opposite strand of the double helix, and no additional separate NRT3.1-like gene could be found. The exception is Medicago trunculata which appears to lack any NRT3.2CT (or NRT3.1) orthologues in the genome at all. This organisation, with the genes being encoded on opposite strands in direct genomic vicinity, is true also for Carica papaya, Cucumis sativus, and Manihot esculenta (data not shown). These results clearly indicate that the genomic organisation found in Arabidopsis may be the exception rather than the rule for dicots.

Figure 8. Genomic organisation of the NRT3 genes in the dicots.

Results are depicted for Arabidopsis thaliana, Arabidopsis lyrata, Ricinus communis, Poplar trichocarpa, Vitis vinifera and Medicago trunculata. The genes represented by a similar colour are reciprocal top BLAST hits. Genes are labelled with Arabidopsis thaliana nomenclature: AtNRT3.1, AtNRT3.2SF1, AtNRT3.2SF2/3 and AtNRT3.2CT. Chromosome or scaffold numbers for each species are provided. Illustrations are not to scale.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine the cereal orthologues of the characterised Arabidopsis NRT genes. Several studies have considered the NRT genes in grasses, but have resulted in some confusion, not least in the nomenclature ascribed to the various NRT genes identified. Much of this confusion was due, presumably, to the unavailability of fully sequenced grass genomes leading, for example, to the cloning of orthologues using degenerate primers. For instance, Lin et al [33] cloned an NRT gene in rice which was referred to as OsNRT1.1 by Tsay et al [3]. This gene is part of the NRT1(PTR) family, but it is not a likely orthologue for AtNRT1.1. From the present analysis, and that of Tsay et al [3], it is evident that the rice genes Os08g05910 and Os10g40600 are much more likely to be the orthologues of AtNRT1.1 than Os03g13274 as originally suggested by Lin et al [33]. Similarly, Liu et al [34] identified AY187878 as the maize orthologue of AtNRT1.1; however this gene does not share as high a similarity with AtNRT1.1 as do the four genes identified in our analysis (GRMZM2G086496, GRMZM2G161483, GRMZM2G161459 and GRMZM2G112154).

The important differences which exist in NRT family structure between Arabidopsis and the grasses indicate that Arabidopsis may not be the best model for interpreting NO3 − transport in the grasses. The grasses have 3–4 closely related co-orthologues to AtNRT1.1. Recent work indicates that AtNRT1.1 (CHL1) may function as a nitrogen sensor [7]; should this be the case, the grasses may have more finely tuned nitrogen sensing, root tissue specific nitrogen sensors, a nitrogen sensor in the shoot tissue (depending on where these genes are expressed), or else may have a very different sensing mechanism altogether. Analysis of the NCBI Unigene database for Oryza sativa Build #80 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/UniGene/UGOrg.cgi?TAXID=4530) shows that OsNRT1.1A and OsNRT1.1B are expressed throughout the rice plant, however OsNRT1.1A is predominantly expressed in the root and is expressed more highly than OsNRT1.1B. This indicates that at least two genes potentially fill the same functional role of AtNRT1.1 in grasses. Conversely, the grass genomes lack certain NRT genes that have been characterised in Arabidopsis. Our analysis reveals that the Brachypodium and rice genomes contain only one protein similar to AtNRT1.7 and AtNRT1.6, or no orthologues in the case of maize and sorghum. AtNRT1.6 appears to be involved in transport of NO3 − from the maternal tissue to the developing embryo [13] and AtNRT1.7 plays a role in the remobilisation of NO3 − from the older leaves [14]. Again analysis of the NCBI Unigene database for Oryza sativa Build #80 shows OsNRT1.7 is expressed in flower, seed and panicle, perhaps indicating that NRT1.7 in the grasses fills a similar functional role to AtNRT1.6. Whether the proposed long distance NO3 − transport functions of the AtNRT1.5 [12] and AtNRT1.8 [15] genes are indeed carried out by their closest grass homologues (NRT1.5A and NRT1.5B) or whether the grasses employ different genes remains to be investigated. The NCBI Unigene database indicates that OsNRT1.5A is expressed predominantly in root and panicle, but also in stem, leaf and flower. OsNRT1.5B was mostly expressed in panicle, but also flower and stem.

Perhaps the most obvious difference between the grasses and Arabidopsis lies in the structure of the NRT2 gene family. The presence of closely located NRT2 genes is reminiscent of the AtNRT2.1/AtNRT2.2 cluster in Arabidopsis and functional analysis of these genes may show similar function between the NRT2 gene clusters. However, with extra duplication in Brachypodium, for example, it will be interesting to identify the functional role played by each of the repeats. Since the NRT2 genes in the grasses lack an intron, it would appear that development of the NRT2 family occurred following the split between the dicots and monocots. It is possible that when they diverged from primitive dicots, the early monocots lost the NRT2 intron(s) whilst the dicots retained the intron(s). However, determination of the development of the NRT2 gene family in plants requires significant further analysis including the genomes of species all along the evolutionary tree, especially other monocots and will need to wait until more genomes are fully sequenced. The NRT2 family is part of the Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS); of interest, therefore, would be an investigation of the other gene families in this superfamily to establish whether they show the same dichotomy in exon/intron structure. The grass genomes do not contain an AtNRT2.7 orthologue. Since the function of this gene is to load NO3 − into the seeds of Arabidopsis [18], again this would indicate a possible difference in the way in which grasses load NO3 − into seeds and embryos (similarly to the lack of AtNRT1.6 described above). Further analysis is required to determine whether the grass NRT2 genes have a similar function to that of the Arabidopsis NRT2 genes, or whether their evolutionary divergence also results in a divergence in function. Should there be a divergence in function the isolation of any common protein motifs or sequence differences that separate the dicot and grass NRT2s may provide important structure/function information of value in guiding biotechnological approaches to improving NO3 − transport in plants. Although not included in our full analysis (since the genome has not been fully sequenced) the four barley (Hordeum vulgare) NRT2s [35], [36] group with the two pairs of Brachypodium NRT2 genes (BdNRT2.1/BdNRT2.2 and BdNRT2.3/BdNRT2.4) (Figure S6); consequently, the functional analysis of these genes provides little insight into the potential function of the NRT2 genes from the other grasses except to indicate the cereal NRT2 transporters likely mediate high affinity NO3 − transport as the barley NRT2 transporters do.

Our analysis of the NRT3 family also indicates there may be fundamental differences between Arabidopsis and the grasses indicative of unique evolutionary events. Of particular importance, the significance of the fusion of the AtNRT3.2SF2/3 gene with the AtNRT3.1CT gene in Arabidopsis compared with the way this protein interacts with the high affinity NRT2 transporters in grasses remains unknown. It will be interesting to determine whether the AtNRT3.2SF2/3 orthologues in the grasses are involved in NO3 − transport. In barley (Hordeum vulgare), three NRT3 genes (NAR2.1, NAR2.2 and NAR2.3) have been identified [37], all of which are similar to the AtNRT3.1 or AtNRT3.2CT genes (Figure S7). It remains to be seen whether or not the NRT3 genes identified in this study play a functional role similar to that of the barley orthologues.

To assist future research we have developed a nomenclature for grass NRT genes (Table 1). Without functional characterisation of the grass NRT orthologues it is difficult to determine which grass orthologue will have similar function to a given Arabidopsis gene, especially in the case of genes with multiple candidates (e.g. NRT1.1). We have attempted to take this issue into account by naming all potential co-orthologues A, B, C, etc. However, in the case of the NRT2 gene family where dicot and grass genes do not cluster together in the phylogenetic tree, this approach becomes problematic. Therefore, we named family members NRT2.1, NRT2.2, etc, despite the fact that a grass NRT2.1 may not share a functional role with AtNRT2.1.

Table 1. Summary of the gene identifiers and new NRT nomenclature for NRT1, 2 and 3 genes in Arabidopsis, poplar, rice, maize, sorghum and Brachypodium.

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Populus trichocarpa | Oryza sativa | Zea mays | Sorghum bicolor | Brachypodium distachyon | ||||||

| Symbol | TAIR ID | Symbol | JGI ID | Symbol | MSU ID | Symbol | Maizesequences.orgID | Symbol | JGI ID | Symbol | Brachypodium.orgID |

| AtNRT1.1 | AT1G12110 | PtNRT1.1 | POPTR_0003s11080.1 | OsNRT1.1A OsNRT1.1B OsNRT1.1C | LOC_Os08g05910.1 LOC_Os10g40600.1 LOC_Os03g01290.1 | ZmNRT1.1A ZmNRT1.1B ZmNRT1.1C ZmNRT1.1D | GRMZM2G086496_P01 GRMZM2G161459_P02 GRMZM2G112154_P01 GRMZM2G161483_P01 | SbNRT1.1A SbNRT1.1B SbNRT1.1C | Sb07g003690.1 Sb01g029470.1 Sb01g050410.1 | BdNRT1.1A BdNRT1.1B BdNRT1.1C BdNRT1.1D | Bradi3g16670.1 Bradi3g33030.1 Bradi3g33040.1 Bradi1g78330.1 |

| AtNRT1.2 | AT1G69850 | PtNRT1.2 | POPTR_0012s07250.1 | OsNRT1.2 | LOC_Os06g38294.1 | ZmNRT1.2 | GRMZM2G137421_P01 | SbNRT1.2 | Sb10g022800.1 | BdNRT1.2 | Bradi1g37330.1 |

| AtNRT1.3 | AT3G21670 | PtNRT1.3A PtNRT1.3B | POPTR_0002s21630.1 POPTR_0014s15580.1 | OsNRT1.3A OsNRT1.3B | LOC_Os02g37040.1 LOC_Os04g39030.1 | ZmNRT1.3 | GRMZM2G176253_P02 | SbNRT1.3 | Sb04g024090.1 | BdNRT1.3 | Bradi3g47010.1 |

| AtNRT1.4 | AT2G26690 | N/A | N/A | OsNRT1.4 | LOC_Os01g37590.1 | ZmNRT1.4A ZmNRT1.4B | GRMZM2G064091_P01 GRMZM2G476069_P01 | SbNRT1.4 | Sb03g024850.1 | BdNRT1.4 | Bradi2g41060.1 |

| AtNRT1.5 | AT1G32450 | PtNRT1.5A PtNRT1.5B | POPTR_0001s02810.1 POPTR_0003s08710.1 | OsNRT1.5A OsNRT1.5B | LOC_Os02g46460.1 LOC_Os02g48570.1 | ZmNRT1.5A ZmNRT1.5B | GRMZM2G044851_P01 GRMZM2G061303_P01 | SbNRT1.5A SbNRT1.5B | Sb04g031320.1 Sb04g029890.1 | BdNRT1.5A BdNRT1.5B | Bradi3g52100.1 Bradi3g53380.1 |

| AtNRT1.6 | AT1G27080 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| AtNRT1.7 | AT1G69870 | PtNRT1.7 | POPTR_0010s04370.1 | OsNRT1.7 | LOC_Os01g68510.1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | BdNRT1.7 | Bradi2g58470.1 |

| AtNRT1.8 | AT4G21680 | PtNRT1.8 | POPTR_0014s17750.1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| AtNRT2.1 AtNRT2.2 AtNRT2.3 AtNRT2.4 AtNRT2.6 | AT1G08090 AT1G08100 AT5G60780 AT5G60770 AT3G45060 | PtNRT2.4A PtNRT2.4B PtNRT2.4C | POPTR_0009s01410.1 POPTR_0143s00200.1 POPTR_0009s01420.1 | OsNRT2.1 OsNRT2.2 | LOC_Os02g02190.1 LOC_Os02g02170.1 | ZmNRT2.1 ZmNRT2.2 ZmNRT2.3 | GRMZM2G010280_P01 GRMZM2G010251_P01 GRMZM2G163866_P01 | SbNRT2.1 SbNRT2.2 SbNRT2.3 | Sb04g001000.1 Sb04g000990.1 Sb04g000970.1 | BdNRT2.1 BdNRT2.2 BdNRT2.3 BdNRT2.4 | Bradi3g01270.1 Bradi3g01250.1 Bradi3g01280.1 Bradi3g01290.1 |

| AtNRT2.5 | AT1G12940 | PtNRT2.5A PtNRT2.5B | POPTR_0015s09290.1 POPTR_0015s09310.1 | OsNRT2.5 | LOC_Os01g50820.1 | ZmNRT2.5 | GRMZM2G455124_P01 | SbNRT2.5 | Sb03g032310.1 | BdNRT2.5 | Bradi2g47640.1 |

| AtNRT2.7 | AT5G14570 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| AtNRT3.1 AtNRT3.2CT | AT5G50200 DQ492237* | PtNRT3.1A PtNRT3.1B PtNRT3.1C | POPTR_0012s09110.1 POPTR_0015s09660.1 POPTR_0015s09670.1 | OsNRT3.1A OsNRT3.1B | LOC_Os02g38230.1 LOC_Os04g40410.1 | ZmNRT3.1A ZmNRT3.1B | GRMZM2G179294_P01 GRMZM2G163494_P01 | SbNRT3.1A SbNRT3.1B | Sb04g024870.1 Sb06g020180.1 | BdNRT3.1A BdNRT3.1B | Bradi3g47720.1 Bradi3g47710.1 |

| AtNRT3.2SF2/3 | AT4G24730.2/3 | PtNRT3.2 | POPTR_0012s09120.1 | OsNRT3.2 | LOC_Os07g48840.3 | ZmNRT3.2 | AC187154.5_FGP003 | SbNRT3.2 | Sb02g011380.2 | BdNRT3.2A BdNRT3.2B | Bradi4g38330.2 Bradi4g38340.2 |

*GenBank Identifer.

In conclusion, the present analysis of the NRT gene families in Arabidopsis and the grasses has revealed some striking differences in gene family structure. Important questions about the evolution of NRT transporters in plants and, significantly, about the suitability of Arabidopsis as a model for NO3 − transport in the grasses have also been posed. With the current exponential increase in the availability of molecular genetic resources for cereal crop plants it appears likely that the relevance of Arabidopsis research will decline. This analysis provides a framework for future studies of NO3 − transporters and transport in the grasses, and potentially will guide strategies for improvement of NUE in cereal species through genetic manipulation of the NRT genes.

Materials and Methods

Sequences and Databases

DNA and amino acid sequences of 17 AtNRT family members (Table S1.) were retrieved from TAIR (The Arabidopsis Information Resource), Arabidopsis thaliana genome annotation database release 9 (http://www.arabidopsis.org/). The complete database of predicted amino acid sequences from Arabidopsis thaliana and Populus trichocarpa as well as from four monocot species; Zea mays, Oryza sativa, Brachypodium distachyon and Sorghum bicolor were downloaded from public databases (Table S3).

Bioinformatics

Identification of homologues

Identification of homologues was based primarily on sequence similarity between the 17 Arabidopsis NRTs and the predicted amino acid sequences of the four above mentioned monocots (maize, rice, Brachypodium and sorghum). This was achieved by using BLASTp, standalone version 2.2.21 [38], [39] and a modified reciprocal best hit (RBH) approach [28], [29]. In brief, BLAST searches were performed which queried the set of 17 AtNRT protein sequences against each of the poplar/monocot databases in a pairwise manner (forward BLAST). Following this and deviating from the standard method, the top ‘cluster of best hits’ returned from each pairwise forward BLAST (based on E-value and sorted by score) was then used as queries in subsequent BLAST searches against the Arabidopsis database (reverse BLAST). Proteins from the reverse BLAST that returned as one of their best hits the original query protein from the forward BLAST (the relevant AtNRT), were then selected for further evaluation as homologues. For all forward and reverse BLASTp searches, E value cut-off was set to 1E-20 (-e 1E-20), output was set to tabular (-m 8), all other parameters were left as default. The aforementioned deviation introduced to the method used in this study was made in an attempt to resolve nearest phylogenetic neighbour and paralogy shortcomings when using BLAST and the strict RBH approach to identify homologues between species [30]. The list of homologues was then refined by removal of those candidates not specifically related to the AtNRTs of interest (Table S4). This was achieved via manual inspection of multiple sequence alignments and their corresponding trees. Throughout the analyses all splice variants of all identified homologues accepted for further analysis were used in subsequent rounds of RBH (eleven candidate homologues were found to possess splice variants, see Table S1). However, only the one member with the longest protein sequence from each splice variant group was used to build trees.

The remaining candidates were then used in all-against-all rounds of RBH analysis between the four monocot sequence databases. The RBH approach and criteria used for the original monocot to dicot search, as described above, was again applied here.

Multiple Sequence Alignment and Tree building

The RBH obtained sequences for NRT1, were aligned by MAFFT version 6.240 using the L-INS-I method with associated default parameters at (http://align.genome.jp/mafft/) [40] and manual editing, for NRT2, 3.1 and 3.2 by T-coffee::Advanced [41] using the server at the Swiss Institute for Bioinformatics, pairwise method set to ‘best_pair4prot’, multiple method set to ‘mafft_msa’ and default for all other parameters (http://tcoffee.vital-it.ch/). Trees were built using various programs of the Phylogenetic Interference Package (PHYLIP) 3.63 (J. Felsenstein, http://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/phylip.html). One thousand bootstrap datasets were generated with SEQBOOT to estimate the confidence limits of nodes. Protein distance matrices were calculated with PROTDIST using the PMB model [42]. Trees were generated with WEIGHBOR [43], and the majority rule consensus tree was generated by CONSENSE (default method used ‘Majority rule (extended)’ >50%). Trees were visualized using the software Geneious v4.8 (Biomatters Ltd, New Zealand, http://www.geneious.com/). Information on genome organisation was obtained from the Phytozome (www.phytozome.org) and TAIR.

Supporting Information

AtNRT1, 2 and 3 reciprocal BLASTp results. Depiction of forward and reverse reciprocal BLASTs is provided for (A) poplar, (B) Brachypodium, (C) maize, (D) sorghum and (E) rice. BLASTp hits of equal e‐value in forward and reverse directions are depicted as forward facing and reverse facing arrows respectively. The colour code of all arrows represents the order of hits, as returned by the BLAST program, first best hit (red), second best hit (blue), third best hit (orange), fourth best hit (green), fifth best hit (black). Truncated arrows indicate a minor drop in the e‐value score between hits. Also coded are the gene accession numbers; an asterisk (*) indicates the presence of alternative splice forms all scoring identical BLASTp results, an upward facing arrow head (∧) indicates a tandem repeat with identical BLAST score, red accessions indicate neighbouring genes in opposing orientation with identical BLAST scores and blue accessions indicate genes in close proximity to each other with identical BLAST scores.

(TIF)

Phylogenetic relationship of potential grass PTR transporters orthologues to AtNRT1.6 and AtNRT1.7. Unrooted Neighbour‐joining tree of NRT1 transporters in Arabidopsis (black), poplar (blue) and 4 grass species: rice (orange), sorghum (green), maize (red) and Brachypodium (purple). Highlighted in the box are the three closest PTR homologues to AtNRT1.6 and AtNRT1.7 (AT1G18880, AT3G47960 and AT5G62680) as well as orthologous grass PTR transporters (all in brown). This figure provides rationale for exclusion of grass transporters (brown) as orthologues to AtNRT1.6 and AtNRT1.7. Bootstrap values from 1,000 replicates were used to estimate the confidence limits of the nodes. The scale bar represents a 0.2 estimated amino acid substitution per residue.

(TIF)

Conservation of closely localised NRT2 genes. Gene identifiers and chromosome number are provided for NRT2 genes (red) for (A) Arabidopsis, (B) poplar, (C) rice, (D) Brachypodium, (E) maize and (F) sorghum. Sorghum has a third closely localised NRT2 gene (blue). Also depicted are non‐NRT2 genes (black) between NRT2 genes. Illustrations are not to scale.

(TIF)

Depiction of AtNRT3 genes. Schematic of the AtNRT3.2 locus (AT4G24730) from TAIR 9 GBrowse (http://gbrowse.arabidopsis.org/). Represented are chromosome, BAC, locus, gene models from TAIR 8 and TAIR 9 and cDNA details.

(TIF)

Alignment of AtNRT3 proteins. Proteins included are AtNRT3.1 and AtNRT3.2CT described previously Okamoto et al [20] and the new versions identified in TAIR9 (AtNRT3.2SF1 AtNRT3.2SF2 and AtNRT3.2SF3). Colour scheme for residue similarity (letter/background): black/white – non similar; blue/light blue – conservative; black/green – block of similar residues; red/yellow – identical; and green/white – weakly similar. Gene identifiers are provided in brackets. Refer to Figure 7 for genomic organisation of Arabidopsis genes.

(TIF)

Phylogenetic relationship of the NRT2 family including barley family members. Unrooted Neighbour‐joining tree of NRT2 transporters in Arabidopsis (black), poplar (blue) and 5 grass species: rice (orange), sorghum (green), maize (red), Brachypodium (purple) and barley (brown). The four barley members include HvNRT2.1 (HVU34198), HvNRT2.2 (HVU34290), HvNRT2.3 (AF091115) and HvNRT2.4 (AF091116). Bootstrap values from 1,000 replicates were used to estimate the confidence limits of the nodes. The scale bar represents a 0.08 estimated amino acid substitution per residue.

(TIF)

Phylogenetic relationship of the NRT3.1 or NRT3.2CT family including barley family members. Unrooted Neighbour‐joining tree of NRT3.1 or 3.2CT family in Arabidopsis (black), poplar (blue) and 5 grass species: rice (orange), sorghum (green), maize (red), Brachypodium (purple) and barley (brown). The three barley members include HvNRT3.1A (HvNAR2.1 ‐ AY253448), HvNRT3.1B (HvNAR2.2 ‐ AY253449) and HvNRT3.1C (HvNAR2.3 ‐ AY253450). Bootstrap values from 1,000 replicates were used to estimate the confidence limits of the nodes. The scale bar represents a 0.09 estimated amino acid substitution per residue.

(TIF)

Identifiers, annotations and family similarities for the Arabidopsis NRT genes described in this study. Provided are the TAIR annotation and identifier, UniprotKB identifier and RefSeq identifier for each NRT gene. Amino acid length of each protein is provided as well as the amino acid identity (%) between the NRTx.1 protein and the other family members.

(XLS)

Comparison of the NRT2 gene intron and exon numbers for dicots and grasses. Gene identifiers and exon and intron numbers are provided for the dicots Arabidopsis thaliana, Populus trichocarpa, Manihot esculenta, Ricinus communis and Vitis vinifera; and for the grasses Oryza sativa, Zea mays, Sorghum bicolor and Brachypodium distachyon.

(XLS)

Web addresses for the genome databases searched during this study including Arabidopsis thaliana , Brachypodium distachyon , Oryza sativa , Populus trichocarpa , Sorghum bicolor and Zea mays .

(XLS)

List of candidate homologues excluded from analysis after manual inspection of multiple sequence alignments and their corresponding trees.

(XLS)

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Carl Simmons, Antoni Rafalski and Kanwarpal Dhugga for their comments on the manuscript. Thanks also to Christina Morris for critical comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: Funding for this research was obtained from both DuPont Pioneer and from an Australian Reseach Council (www.arc.gov.au) Linkage Grant (LP0776635) to BNK and MT. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Raun WR, Johnson GV. Improving nitrogen use efficiency for cereal production. Agron J. 1999;91:357–363. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sylvester-Bradley R, Kindred DR. Analysing nitrogen responses of cereals to prioritize routes to the improvement of nitrogen use efficiency. J Exp Bot. 2009;60:1939–1951. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsay Y-F, Chiu C-C, Tsai C-B, Ho C-H, Hsu P-K. Nitrate transporters and peptide transporters. FEBS Lett. 2007;581(12):2290–2300. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang R, Liu D, Crawford NM. The Arabidopsis CHL1 protein plays a major role in high-affinity nitrate uptake. PNAS. 1998;95(25):15134–15139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.15134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu K-H, Huang C-Y, Tsay Y-F. CHL1 Is a dual-affinity nitrate transporter of Arabidopsis involved in multiple phases of nitrate uptake. Plant Cell. 1999;11(5):865–874. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.5.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu K-H, Tsay Y-F. Switching between the two action modes of the dual-affinity nitrate transporter CHL1 by phosphorylation. EMBO J. 2003;22(5):1005–1013. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho C-H, Lin S-H, Hu H-C, Tsay Y-F. CHL1 functions as a nitrate sensor in plants. Cell. 2009;138(6):1184–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang NC, Liu KH, Lo HJ, Tsay YF. Cloning and functional characterization of an Arabidopsis nitrate transporter gene that encodes a constitutive component of low-affinity uptake. Plant Cell. 1999;11(8):1381–1392. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.8.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orsel M, Krapp A, Daniel-Vedele F. Analysis of the NRT2 nitrate transporter family in Arabidopsis. Structure and gene expression. Plant Physiol. 2002;129(2):886–896. doi: 10.1104/pp.005280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okamoto M, Vidmar JJ, Glass ADM. Regulation of NRT1 and NRT2 gene families of Arabidopsis thaliana: responses to nitrate provision. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003;44(3):304–317. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcg036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiu C-C, Lin C-S, Hsia A-P, Su R-C, Lin H-L, et al. Mutation of a nitrate transporter, AtNRT1:4, results in a reduced petiole nitrate content and altered leaf development. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004;45(9):1139–1148. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin S-H, Kuo H-F, Canivenc G, Lin C-S, Lepetit M, et al. Mutation of the Arabidopsis NRT1.5 nitrate transporter causes defective root-to-shoot nitrate transport. Plant Cell. 2008;20(9):2514–2528. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.060244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Almagro A, Lin SH, Tsay YF. Characterization of the Arabidopsis nitrate transporter NRT1.6 reveals a role of nitrate in early embryo development. Plant Cell. 2008;20(12):3289–3299. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.056788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan S-C, Lin C-S, Hsu P-K, Lin S-H, Tsay Y-F. The Arabidopsis nitrate transporter NRT1.7, expressed in phloem, is responsible for source-to-sink remobilization of nitrate. Plant Cell. 2009;21(9):2750–2761. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.067603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J-Y, Fu Y-L, Pike SM, Bao J, Tian W, et al. Plant Cell; 2010. The Arabidopsis nitrate transporter NRT1.8 functions in nitrate removal from the xylem sap and mediates cadmium tolerance.tpc.110.075242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li W, Wang Y, Okamoto M, Crawford NM, Siddiqi MY, et al. Dissection of the AtNRT2.1:AtNRT2.2 inducible high-affinity nitrate transporter gene cluster. Plant Physiol. 2007;143(1):425–433. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.091223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wirth J, Chopin F, Santoni Vr, Viennois Gl, Tillard P, et al. Regulation of root nitrate uptake at the NRT2.1 protein level in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(32):23541–23552. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700901200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chopin F, Orsel M, Dorbe M-F, Chardon F, Truong H-N, et al. The Arabidopsis ATNRT2.7 nitrate transporter controls nitrate content in seeds. Plant Cell. 2007;19(5):1590–1602. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.050542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orsel M, Chopin F, Leleu O, Smith SJ, Krapp A, et al. Characterization of a two-component high-affinity nitrate uptake system in Arabidopsis. Physiology and protein-protein interaction. Plant Physiol. 2006;142(3):1304–1317. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.085209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okamoto M, Kumar A, Li W, Wang Y, Siddiqi MY, et al. High-affinity nitrate transport in roots of Arabidopsis depends on expression of the NAR2-Like gene AtNRT3.1. Plant Physiol. 2006;140(3):1036–1046. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.074385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goff SA, Ricke D, Lan T-H, Presting G, Wang R, et al. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. japonica). Science. 2002;296:92–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1068275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu J, Hu S, Wang J, Wong GK-S, Li S, et al. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. indica). Science. 2002;296:79–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1068037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.International Rice Genome Sequencing Project. The map-based sequence of the rice genome. Nature. 2005;436(7052):793–800. doi: 10.1038/nature03895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The International Brachypodium Initiative. Genome sequencing and analysis of the model grass Brachypodium distachyon. Nature. 2010;463(7282):763–768. doi: 10.1038/nature08747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schnable PS, Ware D, Fulton RS, Stein JC, Wei F, et al. The B73 maize genome: complexity, diversity, and dynamics. Science. 2009;326(5956):1112–1115. doi: 10.1126/science.1178534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paterson AH, Bowers JE, Bruggmann R, Dubchak I, Grimwood J, et al. The Sorghum bicolor genome and the diversification of grasses. Nature. 2009;457(7229):551–556. doi: 10.1038/nature07723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tuskan GA, DiFazio S, Jansson S, Bohlmann J, Grigoriev I, et al. The genome of Black Cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray). Science. 2006;313(5793):1596–1604. doi: 10.1126/science.1128691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tatusov RL, Koonin EV, Lipman DJ. A genomic perspective on protein families. Science. 1997;278:631–637. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bork P, Dandekar T, Diaz-Lazcoz Y, Eisenhaber F, Huynen M, Yuan Y. Predicting function: from genes to genomes and back. J Mol Biol. 1998;283:707–25. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koski LB, Golding GB. The closest blast hit is often not the nearest neighbour. J Mol Evol, 2001;52(6):540–2. doi: 10.1007/s002390010184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poptsava MS, Gogarten JP. BranchClust: a phylogenetic algorithm for selecting gene families. BMC Bioinform. 2007;8:120. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen F, Mackey AJ, Vermunt JK, Roos DS. Assessing Performance of Orthology Detection Strategies Applied to Eukaryotic Genomes. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(4):e383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin C-M, Koh S, Stacey G, Yu S-M, Lin T-Y, et al. Cloning and functional characterization of a constitutively expressed nitrate transporter gene, OsNRT1, from rice. Plant Physiol. 2000;122(2):379–388. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.2.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu J, Chen F, Olokhnuud C, Glass ADM, Tong Y, et al. Root size and nitrogen-uptake activity in two maize (Zea mays) inbred lines differing in nitrogen-use efficiency. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci. 2009;172(2):230–236. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trueman LJ, Richardson A, Forde BG. Molecular cloning of higher plant homologues of the high-affinity nitrate transporters of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Aspergillus nidulans. Gene. 1996;175(1–2):223–231. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vidmar JJ, Zhuo D, Siddiqi MY, Glass ADM. Isolation and characterization of HvNRT2.3 and HvNRT2.4, cDNAs encoding high-affinity nitrate transporters from roots of barley. Plant Physiol. 2000;122(3):783–792. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.3.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tong Y, Zhou J-J, Li Z, Miller AJ. A two-component high-affinity nitrate uptake system in barley. Plant J. 2005;41(3):442–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucl Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Altschul SF, Wootton JC, Gertz EM, Agarwala R, Morgulis A, et al. Protein database searches using compositionally adjusted substitution matrices. FEBS J. 2005;272:5101–5109. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04945.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Posada D, Katoh K, Asimenos G, Toh H. Multiple alignment of DNA sequences with MAFFT. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;537:39–64. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-251-9_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Notredame C, Higgins D, Heringa J. T-Coffee: A novel method for multiple sequence alignments. J Mol Biol. 2000;302:205–217. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Veerassamy S, Smith A, Tillier ERM. A transition probability model for amino acid substitutions from blocks. J Comput Biol. 2003;10:997–1010. doi: 10.1089/106652703322756195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bruno WJ, Socci ND, Halpern AL. Weighted neighbour joining: a likelihood-based approach to distance-based phylogeny reconstruction. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:189–197. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

AtNRT1, 2 and 3 reciprocal BLASTp results. Depiction of forward and reverse reciprocal BLASTs is provided for (A) poplar, (B) Brachypodium, (C) maize, (D) sorghum and (E) rice. BLASTp hits of equal e‐value in forward and reverse directions are depicted as forward facing and reverse facing arrows respectively. The colour code of all arrows represents the order of hits, as returned by the BLAST program, first best hit (red), second best hit (blue), third best hit (orange), fourth best hit (green), fifth best hit (black). Truncated arrows indicate a minor drop in the e‐value score between hits. Also coded are the gene accession numbers; an asterisk (*) indicates the presence of alternative splice forms all scoring identical BLASTp results, an upward facing arrow head (∧) indicates a tandem repeat with identical BLAST score, red accessions indicate neighbouring genes in opposing orientation with identical BLAST scores and blue accessions indicate genes in close proximity to each other with identical BLAST scores.

(TIF)

Phylogenetic relationship of potential grass PTR transporters orthologues to AtNRT1.6 and AtNRT1.7. Unrooted Neighbour‐joining tree of NRT1 transporters in Arabidopsis (black), poplar (blue) and 4 grass species: rice (orange), sorghum (green), maize (red) and Brachypodium (purple). Highlighted in the box are the three closest PTR homologues to AtNRT1.6 and AtNRT1.7 (AT1G18880, AT3G47960 and AT5G62680) as well as orthologous grass PTR transporters (all in brown). This figure provides rationale for exclusion of grass transporters (brown) as orthologues to AtNRT1.6 and AtNRT1.7. Bootstrap values from 1,000 replicates were used to estimate the confidence limits of the nodes. The scale bar represents a 0.2 estimated amino acid substitution per residue.

(TIF)

Conservation of closely localised NRT2 genes. Gene identifiers and chromosome number are provided for NRT2 genes (red) for (A) Arabidopsis, (B) poplar, (C) rice, (D) Brachypodium, (E) maize and (F) sorghum. Sorghum has a third closely localised NRT2 gene (blue). Also depicted are non‐NRT2 genes (black) between NRT2 genes. Illustrations are not to scale.

(TIF)

Depiction of AtNRT3 genes. Schematic of the AtNRT3.2 locus (AT4G24730) from TAIR 9 GBrowse (http://gbrowse.arabidopsis.org/). Represented are chromosome, BAC, locus, gene models from TAIR 8 and TAIR 9 and cDNA details.

(TIF)

Alignment of AtNRT3 proteins. Proteins included are AtNRT3.1 and AtNRT3.2CT described previously Okamoto et al [20] and the new versions identified in TAIR9 (AtNRT3.2SF1 AtNRT3.2SF2 and AtNRT3.2SF3). Colour scheme for residue similarity (letter/background): black/white – non similar; blue/light blue – conservative; black/green – block of similar residues; red/yellow – identical; and green/white – weakly similar. Gene identifiers are provided in brackets. Refer to Figure 7 for genomic organisation of Arabidopsis genes.

(TIF)

Phylogenetic relationship of the NRT2 family including barley family members. Unrooted Neighbour‐joining tree of NRT2 transporters in Arabidopsis (black), poplar (blue) and 5 grass species: rice (orange), sorghum (green), maize (red), Brachypodium (purple) and barley (brown). The four barley members include HvNRT2.1 (HVU34198), HvNRT2.2 (HVU34290), HvNRT2.3 (AF091115) and HvNRT2.4 (AF091116). Bootstrap values from 1,000 replicates were used to estimate the confidence limits of the nodes. The scale bar represents a 0.08 estimated amino acid substitution per residue.

(TIF)

Phylogenetic relationship of the NRT3.1 or NRT3.2CT family including barley family members. Unrooted Neighbour‐joining tree of NRT3.1 or 3.2CT family in Arabidopsis (black), poplar (blue) and 5 grass species: rice (orange), sorghum (green), maize (red), Brachypodium (purple) and barley (brown). The three barley members include HvNRT3.1A (HvNAR2.1 ‐ AY253448), HvNRT3.1B (HvNAR2.2 ‐ AY253449) and HvNRT3.1C (HvNAR2.3 ‐ AY253450). Bootstrap values from 1,000 replicates were used to estimate the confidence limits of the nodes. The scale bar represents a 0.09 estimated amino acid substitution per residue.

(TIF)

Identifiers, annotations and family similarities for the Arabidopsis NRT genes described in this study. Provided are the TAIR annotation and identifier, UniprotKB identifier and RefSeq identifier for each NRT gene. Amino acid length of each protein is provided as well as the amino acid identity (%) between the NRTx.1 protein and the other family members.

(XLS)

Comparison of the NRT2 gene intron and exon numbers for dicots and grasses. Gene identifiers and exon and intron numbers are provided for the dicots Arabidopsis thaliana, Populus trichocarpa, Manihot esculenta, Ricinus communis and Vitis vinifera; and for the grasses Oryza sativa, Zea mays, Sorghum bicolor and Brachypodium distachyon.

(XLS)

Web addresses for the genome databases searched during this study including Arabidopsis thaliana , Brachypodium distachyon , Oryza sativa , Populus trichocarpa , Sorghum bicolor and Zea mays .

(XLS)

List of candidate homologues excluded from analysis after manual inspection of multiple sequence alignments and their corresponding trees.

(XLS)