Abstract

The retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein, Rb, plays a major role in the regulation of mammalian cell cycle progression. It has been shown that Rb function is essential for the proper modulation of G1/S transition and inactivation of Rb contributes to deregulated cell proliferation. Rb exerts its cell cycle regulatory functions mainly by targeting the E2F family of transcription factors and Rb has been shown to physically interact with E2Fs1, 2 and 3, repressing their transcriptional activity. Multiple genes involved in DNA synthesis and cell cycle progression are regulated by E2Fs, and Rb prevents their expression by inhibiting E2F activity, inducing growth arrest. It has been established that inactivation of Rb by phosphorylation, mutation, or by the interaction of viral oncoproteins lead to a release of the repression of E2F activity, facilitating cell cycle progression. Rb-mediated repression of E2F activity involves the recruitment of a variety of transcriptional co-repressors and chromatin remodeling proteins, including histone deacetylases, DNA methyl transferases and Brg1/Brm chromatin remodeling proteins. Inactivation of Rb by sequential phosphorylation events during cell cycle progression leads to a dissociation of these co-repressors from Rb, facilitating transcription. It has been found that small molecules that prevent the phosphorylation of Rb prevents the dissociation of certain co-repressors from Rb, especially Brg1, leading to the maintenance of Rb mediated transcriptional repression and cell cycle arrest. Such small molecules have anti-cancer activities and will also act as valuable probes to study chromatin remodeling and transcriptional regulation.

Keywords: Raf-1, cyclin-dependent kinases, RRD-251, cell cycle arrest, transcriptional repression

1. Introduction

The proliferation of normal cells is regulated by growth promoting proto-oncogenes whose activity is counterbalanced by growth constraining tumor suppressor genes [1, 2]. Any mutation that disrupts this balance leads to uncontrolled cell proliferation contributing to oncogenesis. Studies in the past three decades have identified tumor suppressor genes to be wild type alleles of genes that play regulatory roles in cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis and angiogenesis [3, 4]. For example, the Rb tumor suppressor gene product plays a major role in regulating G1/S transition [5] while the p53 tumor suppressor gene modulates apoptosis as well as checkpoint control [6–8]. VHL tumor suppressor is an example of a protein that functions to regulate angiogenesis under hypoxic conditions [9–11]. Interestingly, the tumor suppressor genes mentioned above function by acting at the level of transcriptional regulation for the most part. Similarly, many cdk inhibitors cloned over the past fifteen years function as tumor suppressors by virtue of their ability to inhibit cell proliferation, indirectly by affecting the transcription regulatory functions of Rb as well as p53 target genes [12, 13].

Our laboratory has been interested in studying the mechanisms by which the Rb protein exerts its growth control properties and how inactivation of Rb leads to oncogenesis [14]. The Rb family consists of three genes, Rb, p107 and p130 [15]; of these, only Rb has been found to be mutated in a wide array of tumors [8, 16]. All three family members have a central conserved domain that is essential for their growth suppressive functions [17]. This domain, known as the pocket domain, mediates their interaction with a variety of cellular proteins as well as many viral oncoproteins like adenovirus E1A, SV40 large T-antigen and E7 protein of human papilloma virus [18–20]. It is thought that the interaction of these proteins with Rb brings about an inactivation that is equivalent to a mutation of its gene [21]. Supporting this contention, an earlier analysis had shown that human cervical carcinoma cell lines harboring mutations in the Rb gene did not harbor human papilloma virus while those cell lines that had a wild type Rb gene all had HPV. This was explained by the fact that in cells containing wild type Rb gene, the protein was inactivated by its interaction with the HPV E7 gene.

2. Regulation of Rb function

During the course of normal cell cycle progression, Rb is inactivated by a cascade of phosphorylation events leading to the dissociation of proteins associated with Rb [22, 23]. These phosphorylation events are fine tuned in a signal dependent manner by a complex machinery comprising of cyclins, cyclin dependent kinases and the inhibitors of cyclin dependent kinases. It has been demonstrated that cyclin dependent kinases, especially cdk4 and cdk6, in association with cyclin D phosphorylate Rb in mid-G1 leading to its partial inactivation [24]. This coincides with the dissociation of various cellular proteins from Rb. Phosphorylation by kinases associated with D type cyclins is followed by further rounds of phosphorylation by kinases associated with cyclin E, mainly cdk2 [5]. While this leads to almost complete inactivation of Rb, further phosphorylation events mediated by cdk2 and cdc2 in association with cyclin A might also contribute to the complete inactivation of Rb, facilitating cell cycle progression [25]. Studies from our lab had shown that the kinase Raf-1 (c-Raf) can physically interact with Rb and phosphorylate it early in the cell cycle, facilitating subsequent phosphorylation events [26, 27]. It is likely that the Raf-1 mediated phosphorylation is a priming phosphorylation that is necessary for the subsequent phosphorylation of Rb by cyclin dependent kinases.

In addition to proliferative signals, it has been found that Rb is also phosphorylated upon apoptotic signaling and this can overcome the anti-apoptotic functions of Rb [14, 28, 29]. Thus, stimulation of cell with agents like TNFα or Fas ligand or an anti-Fas antibody led to a significant phosphorylation of Rb, leading to its inactivation [28, 30]. Interestingly, this inactivation was completely independent of cyclins or cyclin dependent kinases [31]. Studies on a variety of cell lines showed that the kinases involved in the inactivation of Rb in response to apoptotic signaling are the p38 and ASK1 [28, 30, 31]. It was found that the p38 kinase could phosphorylate Rb effectively and the phosphorylation sites were distinct from that of cyclin dependent kinases. Further, p38 could phosphorylate and inactivate Rb whose phosphorylation sites for cyclin dependent kinases were mutated [31].

During the course of these investigations, it was also found that the kinase ASK1 had a canonical LXCXE motif that mediates binding to Rb and that ASK1 could bind to Rb in response to apoptotic signals. ASK1 binding occurred only in response to such signals and appeared to displace Raf-1 from Rb. ASK1 had to interact with and inactivate Rb to induce apoptosis and a mutant that could not bind to RB had minimal apoptotic effects [30]. In a similar vein, it was found that while a wild type Rb gene could prevent ASK1-induced apoptosis, a RB mutant could not. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays showed that there was a differential recruitment of Rb on proliferative and apoptotic promoters depending on the signals received and this correlated with the kinase inactivating Rb [30, 32]. These studies show that various upstream signals can affect Rb function to elicit the appropriate biological effect.

3. E2Fs as Downstream effectors of Rb function

Studies in the early 1990s identified the E2F transcription factor as the major downstream target of the Rb protein [33–35] based on EMSA analysis and antibody supershift experiments. Though the exact mechanism by which pRb controls the cell cycle is not completely understood, it is considered that pRb-family members mainly function through their association with the E2F family of transcription factors. The E2F transcription factor originally characterized has now been demonstrated to comprise of 8 related genes, E2Fs 1 through 8 [36, 37]. Of these, E2Fs 1, 2 and 3 have a strong transcriptional activation domain and interact with the Rb protein [38, 39]. E2Fs 4 and 5 have weak transcriptional activity, if at all, and are regulated by p107 and p130. E2Fs 6, 7 and 8 do not bind to Rb family proteins but strongly repress transcription by recruitment of transcriptional co-repressors [36, 40]. All the transcriptionally active E2F family members recognize the same canonical sequence on the DNA and are capable of inducing similar sets of genes; while all three E2F family members can strongly induce S-phase entry, it has been suggested that E2F1 and E2F3 has pro-apoptotic activity as well [37, 41].

E2F activity is necessary for the induction of many genes required for S phase progression and Rb inhibits cell cycle progression by repressing the transcriptional activity of E2Fs and their target genes [41]; a role for E2F-mediated repression has also been proposed in growth control recently [42, 43]. The prevailing model is that E2F4 and E2F5 are the main E2Fs present on gene promoters in Go/G1 phase in complex with pRb family members and other co-repressors [44]. As the levels of CDKs rise in G1, repressor complexes dissociate from their target promoters, and E2F activator complexes are recruited. Once pRb is completely phosphorylated and hence inactivated, the activating E2Fs can initiate the transcription of genes required for passage from G1 into S-phase including cyclins A and E, CDC2, p107, Rb, MYC, E2F1, and others [44, 45]. Taken together, the E2F family is responsible to maintaining the appropriate movement of cells through all phases of the cell cycle.

3.1 Mechanisms of E2F-mediated transcriptional regulation

The manner in which E2Fs regulate gene expression is complex—being dependent largely on the structure of the individual E2F protein itself. Every E2F has at least one winged-helix DNA binding motif, where E2F7 and E2F8 have two DNA binding motifs [44, 46]. E2F1-6 are usually found associated with one the three dimerization partner proteins, TFDP1 (DP1, DRTF1), TFDP2 (murine DP3, DP2, FLJ39131, DKFZp313O196), and TFDP3 (human DP4, murine DP3, CT30, HCA661, MGC161639), where this dimerization is mediated by the leucine zipper and marked box domains [41]. Like E2Fs, the DP family of transcription factors are evolutionarily conserved from Arabidopsis to Humans, contain both activating and repressive members, and can bind to canonical E2F binding sites [47’, Girling’, 1993 ‘#1]. Further, the association of these proteins to form heterodimers is responsible for the enhanced Rb binding, DNA binding activity, and transcriptional activity on respective E2F-regulated promoters. Although the pocket domain of Rb is necessary for binding E2F, the C-terminal domain of Rb has a high affinity interaction with the marked box domains of both E2F1 and DP1, which partially explains the importance of the DP1 protein in E2F mediated repression [48]. TFDP2 is structurally and functionally similar to TFDP1, however it can be expressed as several isoforms generated from tissue-specific alternative splicing, and is mainly associated with E2F4 and E2F5 [49–51]. The newest DP family member, TFDP3, is also structurally similar to the other DP family proteins, though it has distinct functions. In fact, heterodimers of TFDP3 and E2F family members do not interact with E2F consensus sequences, inhibit transcription, and impairs the entry into S-phase [52]. Co-transfection experiments also demonstrate that E2F1-mediated apoptosis can be abolished with ectopic expression of TFDP3 [53].

E2F1-5 also contain a transactivation domain, which is used to associate with pRb family proteins, though only E2F4 associates with pRB, p107 and p130, and E2F5 is found mostly with p130 [54]. The repressors, E2F6-8, are structurally different than the activating E2F family members—they lack the carboxy-terminus transactivation domain and are therefore unable to bind to pRb family proteins. E2F6 is has been shown to suppress transcription largely through association with polycomb group proteins [44, 55–57]. The newest members, E2F7 and E2F8, posses their repressive activities independent of heterodimerization with DP proteins or pocket protein binding, but rather through homodimerization or heterodimerization with each other [58, 59].

In more recent years, a considerable amount of research using gene profiling arrays and chromatin immunoprecipitation arrays (ChIP on chip) has been directed at discovering E2F targets and their associated coactivators and corepressors [60] [61, 62] [63] [64, 65]. Although it was initially assumed that E2Fs were evolutionarily conserved to regulate the cell cycle exclusively, these studies highlight a role for E2Fs in diverse biological processes such as development, cell differentiation, apoptosis, and angiogenesis in mammals. This is contradictory to the initial canon of a central role for E2F in proliferation--and alluring as a potential target for drug discovery, particularly in cancers where the Rb gene is frequently mutated resulting in ungoverned E2F activity.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments have also been instrumental in revealing the dynamic changes that take place between different E2Fs, histone acetyltransferases (HATs), histone deacetylaces (HDACs), and histone methyltransferases (HMTs), which determine whether a target gene is consequently repressed or activated. HDACs are recruited to promoters to repress E2F targets, and normally associate with pocket proteins p107 and p130. In addition to HDAC recruitment to E2F-repressed promoter sequences, mSin3A and mSin3B have been shown to serve as scaffolding proteins for the recruitment of intricate repressor complexes [66–68]. Using knock-out mouse models, it has been shown that similarly to E2F/Rb mutant phenotypes in MEFs, the Sin3B knockout MEFs were unable to enter quiescence upon serum starvation [66]. Grandinetti and David posit that while “activating” E2Fs are recruited to target genes in late G1, repressive complexes are recruited to pocket proteins by late G1, which are anchored through RBP1 and SAP 30, and include Sin3B complex with class I HDACs: HDAC1-3 [67]. Further, there is evidence that ErbB3 is also recruited to the complex in vitro and in vivo by Sin3A [69, 70]. Since Sin3 proteins are not found at every promoter that is being repressed, it seems likely that the content of the repressive complex is likely the product of the chromatin configuration where it is recruited.

Repression of E2F target genes can also be accomplished through association with other proteins than the pocket protein family. Fitting into this category, prohibitin, a tumor suppressor protein, has been shown to interact with the marked box domain of E2Fs whereas Rb binds to the transactivation domain [71, 72]. Prohibitin’s repression of E2F cannot be relieved through p38 kinase, E1A, or Cylins D and E, although all of these can reverse Rb function[72]. In addition, CDK activity is crucial for the serum-dependent inactivation of Rb, whereas this is not true with prohibitin [72]. Functional studies using chromatin immunoprecipitation assays show that prohibitin is needed for the recruitment of HP1 to E2F1-regulated proliferative promoters, leading to their repression [73]. This is concurrent with the induction of cell senescence. To enhance E2F-mediated transcriptional repression, prohibitin recruits the SWI/SNF family members BRG-1 and BRM to gene promotors independent of pRB [74]. In contrast to pRb, prohibitin requires N-CoR in addition to histone deacetylase activity for E2F mediated repression [73]. Recent studies have identified RING finger protein 2 (RNF2) a member of the PcG family, which can associate at E2F regulated promoters with prohibitin to inhibit transcription [75].

Not surprisingly, HATs are recruited to E2Fs as coactivators. CREB-binding protein (CBP), p300 (a highly homologous CBP protein) and the associated P/CAF are all known to associate with E2Fs on transcriptionally active promoters [76] [77]. Once Rb is hyperphosphorylated, the E2F1-3 protein itself can then be acetylated at lysines 117, 120, and 125 outside of the DNA binding domain [78]. This acetylation enriches the DNA binding activity of E2Fs, hence strongly activates transcription. The TIP60 complex is also a well-known E2F activating protein complex that is unrelated to CBP [79]. In fact, expression of E2F1 results in the recruitment of five components of the TIP60 complex, which suggests that acetylation can be the result of transcription, instead of a prerequisite, in certain milieus [80].

Besides for chromatin modifying proteins, there have been several studies showing proteins that play a non-traditional role in either repression or activation of E2F target genes. For example, the Lymphoid enhancer protein (LEF-1) is a transcription factor that can interact with E2F1, ergo reliving the repressive marks from HDAC1 [81]. Correspondingly, nuclear factor Y (NF-Y) ChIP experiments show that promoters are stringently regulated by various factors depending on cell cycle stage. In fact, NF-Y binds to target sequences prior to transcription as a histone-like CCAAT binding trimer, when H3 histones are hyperacetylated [82, 83].

3.2 Other functions of E2F proteins

In conjunction with its growth stimulatory properties, E2F1 has been shown to be oncogenic and can transform primary cells in conjunction with Ras or myc [84–86]. The oncogenic properties of E2F1 could be repressed by a functional Rb protein, and this was mediated through a physical association and inhibition of E2F-mediated transcription [87, 88]. In addition to cell proliferation and oncogenesis, some E2F family members, especially E2F1, can induce apoptosis under certain conditions [89–91]. Over-expression of E2F1 in Rat-1 cells promotes premature S-phase entry and apoptosis. Further, studies on E2F1 null mice also support a role for E2F1 in the apoptotic process [92]. It has been shown that E2F1 can induce apoptosis in collaboration with p53 [90, 93] or independent of p53 [94]. The p53-independent pathway is mainly mediated through the p73 protein, whose promoter is a transcriptional target of E2F1 [95, 96]. In addition, other apoptosis related proteins like survivin and Apaf1 are transcriptionally induced by E2F1 [97] contributing to the apoptotic process. It has been suggested that the transcriptional activation domain of E2F1 is not necessary for inducing apoptosis [94], but the fact that various genes involved in the apoptotic process are induced by E2F1 suggests that the transcriptional activity of E2F1 contributes to apoptosis [98].

3.3 Mechanisms of Rb-mediated repression of E2F activity

Detailed analysis of Rb-mediated repression of E2F-mediated transcription showed that Rb recruits a variety of co-repressors to affect different levels of inhibition [99–102]. Thus, histone deacetylase 1 is needed for the Rb-mediated repression of certain promoters [103]. Similarly, other biochemical mechanisms like histone methylation, recruitment of ring family proteins, CtBP and CtIP [104, 105], heterochromatin protein 1 [104, 106], as well as chromatin remodeling complexes like Brg/Brm have been shown to be involved in repression of specific E2F-driven promoters [105, 107, 108]. Elegant studies from the Doug Dean laboratory showed that multiple waves of phosphorylation dissociated Rb from E2Fs or different co-repressors to affect the transcription of specific promoters [23] and our studies showed that the Raf-1 kinase might be involved in the process [26, 27].

Post-translational modifications of the tail region of histones H3 and H4 can affect the packaging of the DNA around nucleosomes altering the accessibility to proteins involved in processes like transcription and repair [109, 110]. Histone acetylation and methylation have been found to be major regulators of transcription and the proteins that mediate such changes have been found to associate with transcription factors as well as other transcription regulators [111]. Thus, the Rb protein has been found to recruit histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) as well as the histone methyl transferase Suv39H to repress transcription. On the contrary, histone acetyl transferases (HATs) like p300/CBP as well as PCAF acetylate histone tails inducing transcription; some of these HATs acetylate transcription factors like p53 and E2F1 [76, 112–114]. It is worth pointing out that HDAC1 activation is correlated with oncogenesis and HDAC inhibitors like SAHA have been found to be efficacious in cancer therapy [115, 116].

Chromatin structure can also be regulated by ATPases using ATP hydrolysis as the source of energy [107, 117]. These processes remodel the nuecleosomal structure and position to alter the access of transcription factors to the promoters [118–121]. The first of these ATPase was identified in yeast as SWI2/SNF2 [118–121]. Studies revealed that SWI/SNF is involved in transcription activation as well as repression in yeast [117, 121]. The human homologs SWI2/SNF2 are BRG1/BRM. Both BRG1 and BRM can modulate the Rb function by direct interaction with Rb [122, 123]. Studies showed that expression of a dominant-negative form of BRG1 or BRM containing a mutant ATPase domain was not able to act as corepressors of Rb function [122, 124]. In transient transfection assays, Rb targets BRM to E2F and forms a complex with both E2F and BRM at the same at E2F responsive promoter and prevented cells for entering into S-phase [118]. Similarly, BRG1 also contain Rb-binding motif and binds to the pocket of Rb protein [122]. This study showed that overexpression of BRG1 cooperated with Rb to growth arrest the cells in absence of BRM expression [122]. Further, studies done with BRG1/BRM deficient cell lines C33a, SW1, PANC-1 and A427 revealed that functional cooperation of BRG-1/BRM is essential for Rb to inhibit cell cycle progression [24, 124, 125]. Reintroduction of BRG1 or BRM into A427 and C33a cells restored Rb-mediated signaling and caused cell cycle arrest [125]. These experiments revealed that BRM and BRG-1 could compensate each other’s loss for Rb-mediated signaling.

Histone methyltransferases involved in transcriptional regulation mainly methylate histone H3, lysine 4, 9 or 36, while other lysines can also be methylated [111]. Each lysine can be mono-, di-, or tri methylated; in addition, certain arginines on H3 tail are methylated as well [109, 110]. H3 lysine 9 methylation is correlated with transcriptional repression, while lysine 4 or 36 methylation correlates with transcriptional activation. The hetrochromatization of euchromatic promoters is one of the important tumor suppressor functions of Rb to ensure the proper cell cycle progression. Hetrochromatic DNA foci contain accumulation of hypoacetylated, H3-tri-methylated and HP1 bound histones, which results in stable repression of E2F responsive genes in senescent cells. Importantly, these features require functional Rb pathway [126]. However, hetrochromatization of E2F responsive promoters are stable in senescent cells, it is likely to be a reversible process in cycling cells. In mammalian cells, hetrochromatin domains are tri-methylated at Histone H3 at lysine 9 (H3K9) by HMTases Suv39h1 and Suv39h2 which creates the binding site for HP1 to form higher order structure of hetrochromatin [127–130]. Recently two more HMTases are identified to bind HP1 for and tri methylation of histone H4 at lysine 20 (H4K20) [131]. The functional association of Rb and HMTases in cell cycle was revealed by ChIP experiments on E2F responsive cyclin E promoter. DNA adjacent to the transcription start site of the cyclin E gene was specifically associated with both H3K9 and HP1 and was completely absent in cells lacking pRB, SUV39H1 or SUV39H2. Also, cyclin E expression was found to be elevated in both Rb−/− and Suv39h1−/− Suv39h2−/− double-knockout cells, suggesting that HMTases cooperates with Rb to suppress E2F responsive promoters [132, 133]. Since, cyclin E expression fluctuates throughout the cell cycle, the observation that its promoter is regulated by histone methylation raises the question about relatively stable modification of chromatin by methylation of histones.

Histone methylation was considered irreversible until very recently when Shi et al. [134] discovered a lysine-specific histone demethylase (LSD1). They showed LSD1 specifically demethylates H3K4me2/me1 and not H3K4me3 leading to transcriptional corepression [134]. Metzer et al. [135] demonstrated that LSD1 demethylates H3K9me2/me1 to promote androgen receptor (AR)-dependent transcription and cell proliferation. These studies suggested that LSD1’s specificity and activity is in fact regulated by associated protein cofactors and site of histone demethylation determines transcriptional activity [136, 137]. LSD1 along with four and a half LIM domain protein 2 (FHL 2) and androgen receptor have been reported to be elevated in high-risk prostate tumors [138]. JMJD2 family of histone demethylases consisting of JMJD2A, JMJD2B, JMJD2C, JMJD2D, JMJD2E and JMJD2F were first identified and characterized in silico [139]. Functionally, 2A-C removes methyl groups from H3K9 (me3/2) and H3K36 (me3/me2) whereas 2D from tri-, di- and mono-methylated H3K9 alone [140]. These proteins can repress or activate promoter specific gene transcription. JMJD1A is another histone demethylase that facilitates transcription activation by androgen receptor [141]. JMJD2A associates with Rb and class 1 HDACs in vivo there by mediating repression of E2F-regulated promoters [142]. Another class of histone demethylases to be identified is JHDMs (JmjC domain containing histone demethylases). JHDM1A preferentially demethylates H3K36me2 [143] and JHDM3A demethylates H3K9me3/H3K36me3 with a repressive activity. Its overexpression was found to abrogate recruitment of HP1 to heterochromatin [144], probably because K9 demethylation is associated with transcription activation

4. Small molecule modulators of Rb/E2F pathway and chromatin remodeling

It is well established that chromatin condensation and decondensation are events that are tightly linked to cell cycle regulation [145, 146]. Additional cellular phenomena like senescence also leads to alterations in global chromatin organization [73, 147]. Not surprisingly, it has been shown that a variety of cell cycle modulators can affect overall chromatin structure [148–153]. Thus, cdk inhibitors like olomoucine, roscovitine and flavopiridol has been found to affect the large scale reorgranization of chromatin and decouple condensation and decondensation from cell cycle stages [154, 155]. Further, from a clinical standpoint, it has been shown that combination of topoisomerase inhibitors as well as HDAC inhibitors with cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors can uncouple chromatin remodeling and cell cycle progression [156, 157]. Some of these agents could modify chromatin such that the transcription of vital genes was affected, thus impacting the survival of cells. It is easy to imagine that many of these molecules would be affecting chromatin structure by modulating the function of the Rb/E2F pathway, directly or indirectly.

Studies from our lab on disruptors of Rb-Raf-1 interaction provided certain new insights into the potential mechanisms by which modulators of Rb function might affect chromatin structure and gene expression [26]. We had observed that the kinase Raf-1 translocates to the nucleus upon growth factor stimulation, where it physically interacts with the Rb protein [26, 27]. Disruption of this interaction by an 8-amino acid peptide (ISNGFGFK) derived from Raf-1 prevented the phosphorylation of Rb even in late G1. This led to the accumulation of functional, unphosphorylated Rb in the cells and led to cell cycle arrest. Further, it was observed that disruption of the Rb-Raf-1 interaction by this peptide inhibited angiogenesis as well as tumor growth in mouse xenograft models [27].

It was also found that the binding of Raf-1 to Rb did not disrupt the binding of E2F1 to Rb; this was different from the case of viral oncoproteins like adenovirus E1A or HPV E7 proteins, which disrupt the binding of E2F1 to Rb [18]. At the same time, like E1A or E7, the binding of Raf-1 to Rb relieved the Rb-mediated repression of E2F1 transcriptional activity. Interestingly, Raf-1 could relieve the transcriptional repression effected by Rb independent of cyclin dependent kinases in a transient transfection experiment [27]. Similar effects were observed when a small molecule disruptor of the Rb-Raf-1 interaction, RRD-251, was used [158, 159].

Attempts were made to understand how RRD-251 or the ISNGFGFK peptide reversed the transcriptional repression of E2F1 mediated by the Rb protein. It has been established that E2F1 itself as well as co-repressors like HDAC1 are dissociated from Rb in mid- to late G1, following multiple rounds of phosphorylation events [23]. Since Raf-1 binds to Rb very early in the cell cycle, about 15 minutes to 2 hours after serum stimulation of quiescent cells, attempts were made to assess whether any chromatin modifying proteins or transcriptional repressors dissociate from Rb in the early G1 phase of the cell cycle. Immunoprecipitation-western blot analysis showed that the chromatin remodeling protein, Brg1, dissociates from Rb early in G1 upon growth factor stimulation, at the same time point where Raf-1 associates with Rb [27]. There was no cyclin D or cyclin E associated with Rb at this early time point, suggesting that the dissociation of Brg1 was probably mediated by the binding of Raf-1 to Rb. Interestingly, treating the cells with ISNGFGFK peptide or RRD-251 disrupted the binding of Raf-1 to Rb as expected, and led to the retention of Brg1 on Rb, confirming this hypothesis.

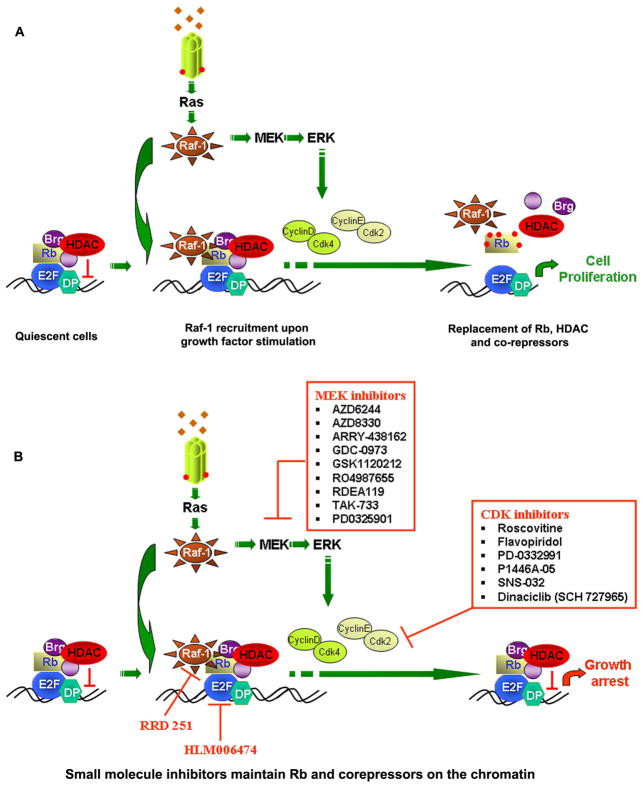

It was next examined whether the recruitment of Brg1 to Rb in the cells could be detected on chromatin. Towards this purpose, chromatin immunoprecipitation assays were conducted on quiescent cells, or those stimulated with serum for 2 hours in the presence or absence of RRD-251 or ISNGFGFK peptide. It was found that there was a significant amount of E2F1, Rb and Brg1 associated with E2F-regulated proliferative promoters like thymidylate synthase (TS) and Cdc25A in quiescent cells [27, 158]. As shown in Figure 1A, serum stimulation of the quiescent cells for two hours led to the association of Raf-1 with these promoters, with the concomitant dissociation of Brg1; other co-repressors like HDAC1 and HP1γ were retained on the promoter. Interestingly, serum stimulation in the presence of RRD-251 or ISNGFGFK peptide led to the inhibition of the binding of Raf-1 to Rb on the promoter; further, the Brg1 protein remained on the promoter even after serum stimulation. All the proteins, excluding E2F1, were dissociated from the promoter 16 hours after serum stimulation as expected, due to the complete inactivation of Rb by cyclin dependent kinases. These studies reveal that small molecule disruptors of the Rb-Raf-1 interaction can affect the chromatin fine structure by modulating the association of Brg1 with specific promoters that are regulated by Rb and E2F1. The striking feature of these molecules is that the association of other co-repressors like HDAC1 or HP1γ with Rb is not affected. Thus RRD-251 and similar molecules can be used as probes to study chromatin fine structure in relation to transcriptional regulation [158–160].

Figure 1.

Chromatin modification upon growth factor stimulation and the effect of small molecule inhibitors. (A) Quiescent cells have a variety of co-repressors and chromatin remodeling complexes associated with specific cellular promoters through the association with the E2F-DP complexes. Growth factor signaling leads to the eventual dissociation of these complexes, facilitating transcription and cell cycle progression. (B) Inhibitors of Rb-Raf-1 interaction, MAP/ERK kinase pathway, cyclin-cdks and E2F can prevent the dissociation, resulting in transcriptional repression of proliferative promoters and growth arrest.

5. Conclusions

The Rb-E2F pathway is vital regulator of various important biological phenomena including cell proliferation, differentiation, senescence and apoptosis. These protein extert their biological function by affecting the expression of genes involved in these processes by recruiting a variety of co-repressors and co-activators. Small molecules that can affect the function of Rb as well as E2F have the potential to modulate these biological processes and also have potential therapeutic benefits. In addition, as shown in Figure 1B, molecules such as RRD-251 or MEK and CDK inhibitors as well as E2F inhibitor by itself can also be used to study chromatin organization and function, especially in context of transcriptional regulation. These agents also affect cell proliferation, thus functioning as potent anti-cancer agents. It remains to be seen whether RRD-251 and similar molecules can affect global chromatin structure, including condensation and decondensation, independent of the cell cycle.

Acknowledgments

The work in S. Chellappan’s lab is supported by the grants CA118210, CA139612, CA127725 and CA77301 from the NCI.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bishop JM. Science. 1987;235:305–311. doi: 10.1126/science.3541204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishop JM. Cell. 1991;64:235–248. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90636-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho A, Dowdy SF. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(01)00263-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macleod K. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:81–93. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)00041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinberg RA. Cell. 1995;81:323–330. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor WR, Stark GR. Oncogene. 2001;20:1803–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hickman ES, Moroni MC, Helin K. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:60–6. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(01)00265-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sherr CJ, McCormick F. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:103–12. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansen WJ, Ohh M, Moslehi J, Kondo K, Kaelin WG, Welch WJ. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1947–60. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.6.1947-1960.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaelin WG., Jr Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:673–82. doi: 10.1038/nrc885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohh M, Kaelin WG., Jr Methods Mol Biol. 2003;222:167–83. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-328-3:167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harper JW. Cancer Surv. 1997;29:91–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamb A. Trends Genet. 1995;11:136–140. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)89027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dasgupta P, Padmanabhan J, Chellappan S. Curr Mol Med. 2006;6:719–29. doi: 10.2174/1566524010606070719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cobrinik D. Oncogene. 2005;24:2796–809. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nevins JR. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:699–703. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.7.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Classon M, Dyson N. Exp Cell Res. 2001;264:135–47. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nevins JR. Science. 1992;258:424–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1411535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nevins JR. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 1994;4:130–4. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(94)90101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JO, Russo AA, Pavletich NP. Nature. 1998;391:859–65. doi: 10.1038/36038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nevins JR. Biochemical Society Transactions. 1993;21:935–8. doi: 10.1042/bst0210935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherr CJ. Trends Cell Biol. 1994;4:15–18. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(94)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harbour JW, Luo RX, Dei Santi A, Positgo AA, Dean DD. Cell. 1999;98:859–69. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81519-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang HS, Gavin M, Dahiya A, Postigo AA, Ma D, Luo RX, Harbour JW, Dean DC. Cell. 2000;101:79–89. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80625-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cobrinik D, Dowdy SF, Hinds PW, Mittnacht S, Weinberg RA. Trends Biochem Sci. 1992;17:312–5. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90443-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang S, Ghosh R, Chellappan S. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7487–7498. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dasgupta P, Sun J, Wang S, Fusaro G, Betts V, Padmanabhan J, Sebti SM, Chellappan SP. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9527–41. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9527-9541.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang S, Nath N, Minden A, Chellappan S. Embo J. 1999;18:1559–70. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Padmanabhan J, Chellappan S. Landes Biosciences. 2005. Regulation of Rb function by non-cyclin dependent kinases. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dasgupta P, Betts V, Rastogi S, Joshi B, Morris M, Brennan B, Ordonez-Ercan D, Chellappan S. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38762–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nath N, Wang S, Betts V, Knudsen E, Chellappan S. Oncogene. 2003;22:5986–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dasgupta P, Kinkade R, Joshi B, Decook C, Haura E, Chellappan S. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6332–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509313103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chellappan SP, Hiebert S, Mudryj M, Horowitz JM, Nevins JR. Cell. 1991;65:1053–61. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90557-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bagchi S, Weinmann R, Raychaudhuri P. Cell. 1991;65:1073–82. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90558-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chittenden T, LDM, KWG Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1991;56:187–95. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1991.056.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeGregori J, Johnson DG. Curr Mol Med. 2006;6:739–48. doi: 10.2174/1566524010606070739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson DG, Degregori J. Curr Mol Med. 2006;6:731–8. doi: 10.2174/1566524010606070731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slansky JE, Farnham PJ. Bioessays. 1996;18:55–62. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slansky JE, Farnham PJ. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;208:1–30. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79910-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frolov MV, Dyson NJ. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2173–81. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dimova DK, Dyson NJ. Oncogene. 2005;24:2810–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rowland BD, Denissov SG, Douma S, Stunnenberg HG, Bernards R, Peeper DS. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:55–65. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rowland BD, Bernards R. Cell. 2006;127:871–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trimarchi JM, Lees JA. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:11–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen D, Pacal M, Wenzel P, Knoepfler PS, Leone G, Bremner R. Nature. 2009;462:925–9. doi: 10.1038/nature08544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lammens T, Li J, Leone G, De Veylder L. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:111–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hao XF, Alphey L, Bandara LR, Lam EW, Glover D, La Thangue NB. J Cell Sci. 1995;108(Pt 9):2945–54. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.9.2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rubin SM, Gall AL, Zheng N, Pavletich NP. Cell. 2005;123:1093–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rogers KT, Higgins PD, Milla MM, Phillips RS, Horowitz JM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7594–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Y, Chellappan SP. Oncogene. 1995;10:2085–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.DeGregori J, Leone G, Miron A, Jakoi L, Nevins JR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:7245–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qiao H, Di Stefano L, Tian C, Li YY, Yin YH, Qian XP, Pang XW, Li Y, McNutt MA, Helin K, Zhang Y, Chen WF. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:454–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606169200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tian C, Lv D, Qiao H, Zhang J, Yin YH, Qian XP, Wang YP, Zhang Y, Chen WF. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;361:20–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gaubatz S, Lindeman GJ, Ishida S, Jakoi L, Nevins JR, Livingston DM, Rempel RE. Mol Cell. 2000;6:729–35. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zini N, Trimarchi C, Claudio PP, Stiegler P, Marinelli F, Maltarello MC, La Sala D, De Falco G, Russo G, Ammirati G, Maraldi NM, Giordano A, Cinti C. J Cell Physiol. 2001;189:34–44. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trimarchi JM, Fairchild B, Verona R, Moberg K, Andon N, Lees JA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:2850–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Attwooll C, Oddi S, Cartwright P, Prosperini E, Agger K, Steensgaard P, Wagener C, Sardet C, Moroni MC, Helin K. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1199–208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412509200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Bruin A, Maiti B, Jakoi L, Timmers C, Buerki R, Leone G. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42041–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308105200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li J, Ran C, Li E, Gordon F, Comstock G, Siddiqui H, Cleghorn W, Chen HZ, Kornacker K, Liu CG, Pandit SK, Khanizadeh M, Weinstein M, Leone G, de Bruin A. Dev Cell. 2008;14:62–75. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wells J, Boyd KE, Fry CJ, Bartley SM, Farnham PJ. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5797–807. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.16.5797-5807.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wells J, Graveel CR, Bartley SM, Madore SJ, Farnham PJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3890–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062047499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wells J, Yan PS, Cechvala M, Huang T, Farnham PJ. Oncogene. 2003;22:1445–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jin VX, Rabinovich A, Squazzo SL, Green R, Farnham PJ. Genome Res. 2006;16:1585–95. doi: 10.1101/gr.5520206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lavrrar JL, Farnham PJ. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46343–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402692200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weinmann AS, Bartley SM, Zhang T, Zhang MQ, Farnham PJ. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:6820–32. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.20.6820-6832.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.David G, Grandinetti KB, Finnerty PM, Simpson N, Chu GC, Depinho RA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4168–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710285105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grandinetti KB, David G. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:1550–4. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.11.6052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grandinetti KB, Jelinic P, DiMauro T, Pellegrino J, Fernandez Rodriguez R, Finnerty PM, Ruoff R, Bardeesy N, Logan SK, David G. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6430–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang Y, Woodford N, Xia X, Hamburger AW. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2168–77. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang Y, Akinmade D, Hamburger AW. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:6024–33. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang S, Nath N, Adlam M, Chellappan S. Oncogene. 1999;18:3501–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang S, Nath N, Fusaro G, Chellappan S. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7447–60. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.11.7447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rastogi S, Joshi B, Dasgupta P, Morris M, Wright K, Chellappan S. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:4161–71. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02142-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang S, Zhang B, Faller DV. EMBO J. 2002;21:3019–28. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Choi D, Lee SJ, Hong S, Kim IH, Kang S. Oncogene. 2008;27:1716–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marzio G, Wagener C, Gutierrez MI, Cartwright P, Helin K, Giacca M. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10887–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.10887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang H, Larris B, Peiris TH, Zhang L, Le Lay J, Gao Y, Greenbaum LE. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24679–88. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Martinez-Balbas M, Bauer UM, Nielsen SJ, Brehm A, Kouzarides T. EMBO J. 2000;19:662–671. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.4.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sapountzi V, Logan IR, Robson CN. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:1496–509. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Taubert S, Gorrini C, Frank SR, Parisi T, Fuchs M, Chan HM, Livingston DM, Amati B. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4546–56. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4546-4556.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhou F, Zhang L, Gong K, Lu G, Sheng B, Wang A, Zhao N, Zhang X, Gong Y. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;365:149–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Donati G, Imbriano C, Mantovani R. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:3116–27. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gatta R, Mantovani R. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:6592–607. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 84.Johnson DG, Cress WD, Jakoi L, Nevins JR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:12823–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Singh P, Wong SH, Hong W. Embo J. 1994;13:3329–38. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06635.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Leone G, Sears R, Huang E, Rempel R, Nuckolls F, Park CH, Giangrande P, Wu L, Saavedra HI, Field SJ, Thompson MA, Yang H, Fujiwara Y, Greenberg ME, Orkin S, Smith C, Nevins JR. Mol Cell. 2001;8:105–13. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00275-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Johnson DG, Schneider-Broussard R. Front Biosci. 1998;3:d447–8. doi: 10.2741/a291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Muller H, Helin K. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1470:M1–M12. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(99)00030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Qin XQ, Livingston DM, Kaelin WJ, Adams PD. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:10918–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shan B, Lee WH. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:8166–73. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Phillips AC, Vousden KH. Apoptosis. 2001;6:173–82. doi: 10.1023/a:1011332625740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Field SJ, Tsai FY, Kuo F, Zubiaga AM, Kaelin WJ, Livingston DM, Orkin SH, Greenberg ME. Cell. 1996;85:549–61. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81255-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wu X, Levine AJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:3602–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hsieh JK, Fredersdorf S, Kouzarides T, Martin K, Lu X. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1840–52. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.14.1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Irwin M, Marin MC, Phillips AC, Seelan RS, Smith DI, Liu W, Flores ER, Tsai KY, Jacks T, Vousden KH, Kaelin WG., Jr Nature. 2000;407:645–8. doi: 10.1038/35036614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lissy NA, Davis PK, Irwin M, Kaelin WG, Dowdy SF. Nature. 2000;407:642–5. doi: 10.1038/35036608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Moroni MC, Hickman ES, Denchi EL, Caprara G, Colli E, Cecconi F, Muller H, Helin K. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:552–8. doi: 10.1038/35078527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Stanelle J, Putzer BM. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:177–85. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Harbour JW, Dean DC. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2393–409. doi: 10.1101/gad.813200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lemon B, Tjian R. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2551–69. doi: 10.1101/gad.831000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Macaluso M, Montanari M, Cinti C, Giordano A. Semin Oncol. 2005;32:452–7. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Macaluso M, Montanari M, Giordano A. Oncogene. 2006;25:5263–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Luo RX, Postigo AA, Dean DC. Cell. 1998;92:463–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80940-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Meloni AR, Smith EJ, Nevins JR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:9574–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dahiya A, Wong S, Gonzalo S, Gavin M, Dean DC. Mol Cell. 2001;8:557–69. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00346-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nielsen SJ, Schneider R, Bauer UM, Bannister AJ, Morrison A, O’Carroll D, Firestein R, Cleary M, Jenuwein T, Herrera RE, Kouzarides T. Nature. 2001;412:561–5. doi: 10.1038/35087620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dunaief JL, Strober BE, Guha S, Khavari PA, Alin K, Luban J, Begemann M, Crabtree GR, Goff SP. Cell. 1994;79:119–30. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90405-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Robertson KD, Ait-Si-Ali S, Yokochi T, Wade PA, Jones PL, Wolffe AP. Nat Genet. 2000;25:338–42. doi: 10.1038/77124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kouzarides T. Cell. 2007;128:802. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kouzarides T. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Li B, Carey M, Workman JL. Cell. 2007;128:707–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Galbiati L, Mendoza-Maldonado R, Gutierrez MI, Giacca M. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:930–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.7.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sakaguchi K, Herrera JE, Saito S, Miki T, Bustin M, Vassilev A, Anderson CW, Appella E. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2831–41. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.18.2831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gu W, Roeder RG. Cell. 1997;90:595–606. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80521-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kelly WK, Marks PA. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2005;2:150–7. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kelly WK, O’Connor OA, Krug LM, Chiao JH, Heaney M, Curley T, MacGregore-Cortelli B, Tong W, Secrist JP, Schwartz L, Richardson S, Chu E, Olgac S, Marks PA, Scher H, Richon VM. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3923–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.14.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Tyler JK, Kadonaga JT. Cell. 1999;99:443–6. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81530-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Trouche D, Le Chalony C, Muchardt C, Yaniv M, Kouzarides T. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:11268–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Schnitzler G, Sif S, Kingston RE. Cell. 1998;94:17–27. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lorch Y, Zhang M, Kornberg RD. Cell. 1999;96:389–92. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80551-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Holstege FC, Jennings EG, Wyrick JJ, Lee TI, Hengartner CJ, Green MR, Golub TR, Lander ES, Young RA. Cell. 1998;95:717–28. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81641-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Dunaief JL, Strober BE, Guha S, Khavari PA, Alin K, Luban J, Begemann M, Crabtree GR, Goff SP. Cell. 1994;79:119–30. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90405-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Singh P, Coe J, Hong W. Nature. 1995;374:562–5. doi: 10.1038/374562a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Strobeck MW, Knudsen KE, Fribourg AF, DeCristofaro MF, Weissman BE, Imbalzano AN, Knudsen ES. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7748–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.14.7748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Strobeck MW, Reisman DN, Gunawardena RW, Betz BL, Angus SP, Knudsen KE, Kowalik TF, Weissman BE, Knudsen ES. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4782–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109532200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Narita M, Nunez S, Heard E, Narita M, Lin AW, Hearn SA, Spector DL, Hannon GJ, Lowe SW. Cell. 2003;113:703–16. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00401-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Melcher M, Schmid M, Aagaard L, Selenko P, Laible G, Jenuwein T. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:3728–41. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.10.3728-3741.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Nakayama J, Rice JC, Strahl BD, Allis CD, Grewal SI. Science. 2001;292:110–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1060118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Lachner M, O’Carroll D, Rea S, Mechtler K, Jenuwein T. Nature. 2001;410:116–20. doi: 10.1038/35065132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Bannister AJ, Zegerman P, Partridge JF, Miska EA, Thomas JO, Allshire RC, Kouzarides T. Nature. 2001;410:120–4. doi: 10.1038/35065138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Schotta G, Lachner M, Sarma K, Ebert A, Sengupta R, Reuter G, Reinberg D, Jenuwein T. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1251–62. doi: 10.1101/gad.300704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Ross JF, Liu X, Dynlacht BD. Mol Cell. 1999;3:195–205. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80310-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Rea S, Eisenhaber F, O’Carroll D, Strahl BD, Sun ZW, Schmid M, Opravil S, Mechtler K, Ponting CP, Allis CD, Jenuwein T. Nature. 2000;406:593–9. doi: 10.1038/35020506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Shi Y, Lan F, Matson C, Mulligan P, Whetstine JR, Cole PA, Casero RA, Shi Y. Cell. 2004;119:941–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Metzger E, Wissmann M, Yin N, Muller JM, Schneider R, Peters AH, Gunther T, Buettner R, Schule R. Nature. 2005;437:436–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Shi YJ, Matson C, Lan F, Iwase S, Baba T, Shi Y. Mol Cell. 2005;19:857–64. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Lee MG, Wynder C, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R. Nature. 2005;437:432–5. doi: 10.1038/nature04021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Kahl P, Gullotti L, Heukamp LC, Wolf S, Friedrichs N, Vorreuther R, Solleder G, Bastian PJ, Ellinger J, Metzger E, Schule R, Buettner R. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11341–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Katoh M, Katoh M. Int J Oncol. 2004;24:1623–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Shin S, Janknecht R. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;353:973–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Yamane K, Toumazou C, Tsukada Y, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Wong J, Zhang Y. Cell. 2006;125:483–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Gray SG, Iglesias AH, Lizcano F, Villanueva R, Camelo S, Jingu H, Teh BT, Koibuchi N, Chin WW, Kokkotou E, Dangond F. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28507–18. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413687200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Tsukada Y, Fang J, Erdjument-Bromage H, Warren ME, Borchers CH, Tempst P, Zhang Y. Nature. 2006;439:811–6. doi: 10.1038/nature04433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Klose RJ, Yamane K, Bae Y, Zhang D, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Wong J, Zhang Y. Nature. 2006;442:312–6. doi: 10.1038/nature04853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Belmont AS. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:632–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Ito T. J Biochem. 2007;141:609–14. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Funayama R, Ishikawa F. Chromosoma. 2007;116:431–40. doi: 10.1007/s00412-007-0115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Munshi A, Tanaka T, Hobbs ML, Tucker SL, Richon VM, Meyn RE. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1967–74. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Han X, Berardi P, Riabowol K. Rejuvenation Res. 2006;9:69–76. doi: 10.1089/rej.2006.9.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Bassini A, Pierpaoli S, Falcieri E, Vitale M, Guidotti L, Capitani S, Zauli G. Br J Haematol. 1999;104:820–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Costello JF, Berger MS, Huang HS, Cavenee WK. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2405–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Costello JF, Plass C, Cavenee WK. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2000;17:49–56. doi: 10.1007/BF02482735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Costello JF, Plass C, Cavenee WK. Methods Mol Biol. 2002;200:53–70. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-182-5:053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Monardes A, Iribarren C, Morin V, Bustos P, Puchi M, Imschenetzky M. J Cell Biochem. 2005;96:235–41. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Stephens S, Beyer B, Balthazar-Stablein U, Duncan R, Kostacos M, Lukoma M, Green GR, Poccia D. Mol Reprod Dev. 2002;62:496–503. doi: 10.1002/mrd.90005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Rosato RR, Grant S. Cancer Biol Ther. 2003;2:30–7. doi: 10.4161/cbt.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Rosato RR, Grant S. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2004;13:21–38. doi: 10.1517/13543784.13.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Kinkade R, Dasgupta P, Carie A, Pernazza D, Carless M, Pillai S, Lawrence N, Sebti SM, Chellappan S. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3810–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Davis RK, Chellappan S. Drug News Perspect. 2008;21:331–5. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2008.21.6.1246832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Kinkade R, Dasgupta P, Chellappan S. Current Cancer Therapy Reviews. 2006;2:305–315. [Google Scholar]