Abstract

Mucin 1 (MUC1), a transmembrane mucin expressed at the apical surface of uterine epithelia, is a barrier to microbial infection and enzymatic attack. MUC1 loss at implantation sites appears to be required to permit embryo attachment and implantation in most species. MUC1 expression is regulated by progesterone (P) and proinflammatory cytokines, including TNFα and interferon γ (IFNγ). TNFα and IFNγ are highly expressed in uterine tissues under conditions where MUC1 expression is also high and activate MUC1 expression via their downstream transcription factors, nuclear factor (NF) κB and signal transducers and activators of transcription. P receptor (PR) regulates MUC1 gene expression in a PR isoform-specific fashion. Here we demonstrate that interactions among PR isoforms and cytokine-activated transcription factors cooperatively regulate MUC1 expression in a human uterine epithelial cell line, HES. Low doses of IFNγ and TNFα synergistically stimulate MUC1 promoter activity, enhance PRB stimulation of MUC1 promoter activity and cooperate with PRA to stimulate MUC1 promoter activity. Cooperative stimulation of MUC1 promoter activity requires the DNA-binding domain of the PR isoforms. MUC1 mRNA and protein expression is increased by cytokine and P treatment in HES cells stably expressing PRB. Using chromatin immunoprecipitation assays, we demonstrate efficient recruitment of NFκB, p300, SRC3 (steroid receptor coactivator 3), and PR to the MUC1 promoter. Collectively, our studies indicate a dynamic interplay among cytokine-activated transcription factors, PR isoforms and transcriptional coregulators in modulating MUC1 expression. This interplay may have important consequences in both normal and pathological contexts, e.g. implantation failure and recurrent miscarriages.

Low dose cytokines and progesterone regulates MUC1 gene expression.

Mucins are high-molecular-mass (>200 kDa), extensively O-glycosylated proteins characterized by variable number tandem repeat regions. Serine and threonine residues of variable number tandem repeat domains serve as attachment sites for oligosaccharides, whereas proline residues provide rigidity and contribute to a highly extended protein structure. Mucin 1 (MUC1), a type I transmembrane glycoprotein, belongs to the family of mucins that is expressed in a variety of carcinomas and in normal simple epithelial cells, including those of the female reproductive tract, mammary gland, lung, kidney, stomach, and pancreas as well as a few nonepithelial cell types (1,2,3,4,5). In conjunction with other cell surface and secreted mucins, MUC1 lubricates and hydrates cell surfaces and functions as a protective barrier against microbial and proteolytic attack (2,6). In the uterus, this salient property of MUC1 plays a critical role for successful embryo implantation. Embryo implantation is a highly coordinated process regulated by ovarian steroid hormones and a number of cytokines and growth factors. For successful implantation, direct interaction of the blastocyst with the luminal epithelium of the uterus is a necessary first step. MUC1 down-regulation or loss at implantation sites is prerequisite for a functionally receptive uterus in many species (7,8,9,10). Although in rabbits, MUC1 is expressed throughout the receptive phase, embryo implantation is characterized by a local loss at the implantation site (11). In humans, as in rabbits, the receptive phase is characterized by high levels of MUC1 expression (12,13,14). The only evidence consistent with down-regulation of MUC1 at the site of blastocyst attachment in humans is demonstrated in vitro (15). Regional acute loss of MUC1 may involve locally activated sheddases, e.g. TNFα converting enzyme/a disintegrin and metalloproteinase-17 and membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase (16,17). Alternatively, MUC1 expression can be repressed by protein inhibitor of activated signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) family members (18).

Endometrial MUC1 expression is regulated by ovarian steroid hormones estrogen (E2) and progesterone (P). In mice and humans, P has opposite effects on MUC1 gene expression, being a strong inhibitor in mice (9) and a stimulator in humans (12,15,19). The regulation of the complex multistep process of female reproduction by these hormones is mediated by E2 receptor (ER) and P receptor (PR). Although ER does not appear to directly regulate the human or murine MUC1 gene (19,20), some isoforms of MUC1 mRNA may be regulated by ERα in breast cancer cells (21). The PR isoforms PRA and PRB differentially regulate MUC1 gene expression in uterine epithelial cells (19). A transactivation function domain (AF3) is responsible for activation of certain target genes by PRB, and not by PRA, owing to differential binding of cofactors, in some cases having opposite transcriptional activities (22,23,24). Specifically, liganded PRB stimulates MUC1 promoter activity, whereas PRA represses this action in human uterine epithelial cells. PRA also antagonizes E2-stimulated MUC1 expression in mice (19), demonstrating that opposing actions of these isoforms account for the differential regulation of uterine MUC1 expression in these species. Biological actions of PR are further influenced by steroid hormone receptor coregulators that bridge the transcription machinery and act as coactivators or corepressors (25). These coactivators are expressed in human endometrium during the menstrual cycle in a cyclical manner (26,27).

Implantation also is a physiological inflammatory process, characterized by an influx of cytokines and growth factors at the feto-maternal surface and secreted under the influence of steroid hormones by the endometrium and the implanting blastocyst. Examples include the heparin-binding epidermal growth factor, leukemia inhibitory factor, IL-1β, TNFα, and interferon γ (IFNγ) (28). In addition, human chorionic gonadotropin and cyclooxygenase-derived prostaglandins also play an important role in implantation (29). The human endometrium expresses TNFα throughout the menstrual cycle, and levels correspond to the presence of steroid hormones (30,31,32,33). TNFα also is detected in maternal sera and conditioned medium of human preimplantation blastocysts (34). Both TNF receptor (TNFR)-I and TNFR-II are expressed in the endometrial epithelium during the menstrual cycle (35) and in blastocysts (36). Increased TNFα levels in maternal sera have been found in patients with spontaneous abortions (37). Furthermore, high levels of expression of TNFα and TNFR-I have been associated with pregnancy loss in mice (38,39,40). Blocking TNFR-I results in reduced stress-related abortion in mice (41). Higher levels of IFNγ were detected in patients undergoing recurrent abortions (42). In the human endometrium, IFNγ is expressed in the luminal and glandular epithelia throughout the menstrual cycle (40). Furthermore, both IFNγ receptors (IFNγR), IFNγR-1 and IFNγR-2, are expressed in the human endometrium (43). Mice null for IFNγ and IFNγR-1 show irregularities at implantation sites and are unable to initiate pregnancy-induced modifications including decidualization, angiogenesis, and natural killer cell maturation (44,45). In addition, IFNγ treatments in vivo in mice induce abortion (46). Cytokines with proinflammatory actions are also known to assist the mucosal barriers against microbial challenge. In fact, the proinflammatory cytokines TNFα and IFNγ greatly stimulate MUC1 expression in various cellular contexts (18,47,48,49,50,51,52). Previous investigations from our lab and others have revealed that the actions of above mentioned cytokines are mediated through STAT1α and nuclear factor κB (NFκB) transcription factors binding to STAT and κB binding elements in the MUC1 promoter, respectively (49,50,52). Cytokine-activated transcription factors also are known to recruit cofactors to regulate transcription.

It seems likely that gradients of cytokine levels occur in the endometrium either in the context of embryo implantation, i.e. at the site of blastocyst attachment, or in response to local sites of infection. Thus, it is possible that combinations of low concentrations of cytokines, acting through distinct transcription factors, cooperate or synergize to strongly stimulate MUC1 expression even in areas where levels of individual cytokines are low. P and PR levels also change markedly during the cycle and might alter cytokine responsiveness of MUC1 expression. Given the inhibitory action of PRA with regard to PRB-driven MUC1 expression, it is not clear whether PRA also would inhibit cytokine-stimulated MUC1 expression. Therefore, in this study, we sought to determine whether low concentrations of individual cytokines cooperate to enhance MUC1 expression. Furthermore, we examined how these responses are impacted by PR isoforms.

Results

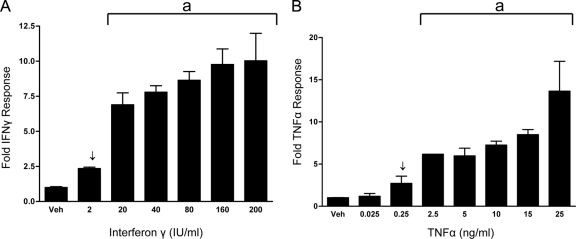

TNFα and IFNγ stimulate MUC1 promoter activity in a dose-dependent manner in HES cells

Previous investigations from our lab have shown that MUC1 P responsiveness is mediated by PR in an isoform-specific fashion (19). In addition, HES cells are responsive both to TNFα (18,50) and IFNγ (18). The first experiments were done to determine the MUC1 promoter dose-response curves for TNFα (0.025–25 ng/ml) and IFNγ (2–200 IU). In transient transfection assays, an IFNγ dose as low as 2 IU/ml and a TNFα dose as low as 0.25 ng/ml each resulted in a 2- to 2.5-fold stimulation of MUC1 promoter activity (Fig. 1, A and B). These concentrations are within ranges detected in unsuccessful pregnancies (34,53,54).

Figure 1.

MUC1 promoter responsiveness to IFNγ (A) or TNFα (B) in HES cells. HES cells were transiently transfected with the 1.4MUC reporter construct as described in Materials and Methods and treated with either vehicle (Veh) or the indicated concentrations of IFNγ (A) or TNFα (B). Data are normalized to mean value of vehicle-treated controls. The bars and error bars indicate the mean ± sd representative of at least two experiments performed in triplicate. Arrows indicate concentrations used in future experiments. The line indicated by a is significant vs. vehicle-treated controls.

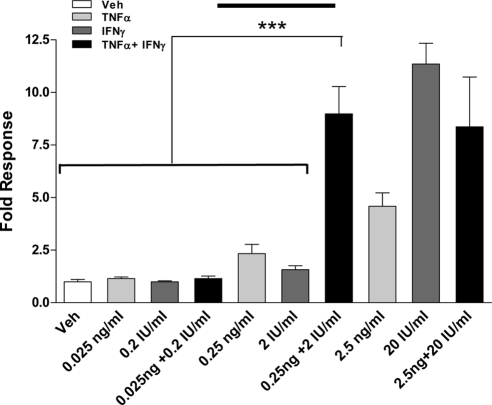

Low cytokine doses synergistically stimulate MUC1 promoter activity

To determine whether these low doses of TNFα (0.25 ng/ml) and IFNγ (2 IU/ml) can cooperate or synergize to stimulate MUC1 promoter activity, transient transfection assays with 1.4MUC were used for HES cells treated with combined cytokine doses 10-fold lower (0.025 ng/ml TNFα and 0.2 IU/ml IFNγ) to 10-fold higher (2.5 ng/ml TNFα and 20 IU/ml IFNγ) than the minimum individual cytokine doses required to stimulate a response determined as described above (Fig. 2). The lowest doses of combined cytokines failed to stimulate MUC1 promoter activity; however, the intermediate concentrations, i.e. 0.25 ng/ml TNFα plus 2 IU/ml IFNγ, synergized to stimulate the promoter maximally. Further stimulation was not observed with combined cytokine treatment, i.e. 20 IU/ml IFNγ plus 2.5 ng/ml TNFα. Combined treatments with higher doses of TNFα and IFNγ resulted in cell death (data not shown). Notably, combined treatments with 0.25 ng/ml TNFα and 2 IU/ml IFNγ maximally increases MUC1 promoter activity. Collectively, these data indicate that low doses of cytokines synergistically induce MUC1 transcriptional activity in HES cells.

Figure 2.

Cytokine doses are within optimal range for synergistic stimulation in HES cells. HES cells were transiently transfected with the 1.4MUC promoter as described in Materials and Methods and were treated either with vehicle (Veh) or with the indicated concentrations of IFNγ and/or TNFα for 24 h. Data are normalized to the mean value of the vehicle-treated controls. The bars and error bars represent the mean ± sd values of at least two experiments performed in triplicate. The solid line in the middle of the graph indicates the cytokine concentrations used in additional experiments. ***, P < 0.001 vs. indicated treatments.

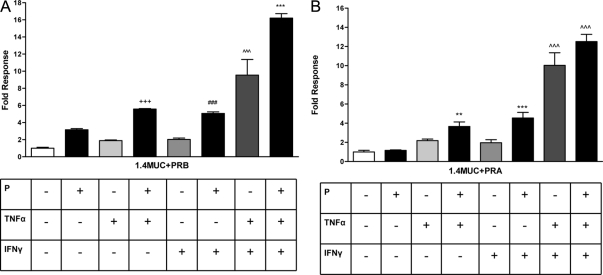

Low doses of cytokines enhance PRB-stimulated MUC1 promoter activity and cooperate with PRA to stimulate MUC1 promoter activity

We then examined the combined ability of cytokine-activated transcription factors and PR isoforms to modulate MUC1 promoter activity in the HES cells. Because the HES cells do not express endogenous PR, transient transfections with PR isoforms were performed for our study. We and others previously have reported that TNFα and IFNγ activate MUC1 promoter activity via NFκB and STAT1 binding, respectively (18,48,49,50,52). Furthermore, we also have reported that P-mediated MUC1 stimulation is through the nuclear receptor, PRB (19). PRA antagonizes liganded PRB-mediated stimulation of MUC1 promoter activity in HEC-1A (19) and HES cells (data not shown). Therefore, we considered whether cytokine activation of MUC1 promoter function might be impacted by P stimulation. Interestingly, combined treatments of P and TNFα as well as P and IFNγ resulted in an additive increase of the MUC1 promoter activity in the presence of PRB (Fig. 3A). Our results contrast with previous reports of PR and NFκB displaying mutual antagonism in other promoter contexts (55). We also observed this positive cooperation in the HEC-1A and T47D cells albeit to a lesser extent than observed in the HES cells (Supplemental Fig. 1, published on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org). A large synergistic stimulation of MUC1 promoter activity by cytokines also was observed in the presence of PRB and further enhanced by the addition of P (Fig. 3A). Similar to previous studies in HEC-1A cells (19), liganded PRA does not stimulate MUC1 promoter activity in HES cells. Interestingly, PRA not only did not antagonize the cytokine stimulation of MUC1 promoter activity but also appeared to cooperate with TNFα and IFNγ to further stimulate MUC1 promoter activity (Fig. 3B). These findings indicate that both PR isoforms act in a positive fashion in the presence of low doses of cytokines to stimulate MUC1 promoter activity and contrast with PRA’s antagonism of PRB action in this regard. Our data also indicate that a novel cooperation exists between P and TNFα downstream actions to regulate MUC1 promoter activity.

Figure 3.

Cytokines and P cooperate to stimulate MUC1 promoter activity. A, HES cells were transiently transfected with the 1.4MUC reporter and hPRB as described in Materials and Methods and then treated with vehicle [0.001% (vol/vol) ethanol and 0.01% (wt/vol) BSA], P (400 nm), TNFα (0.25 ng/ml), or IFNγ (2 IU/ml) as indicated for 24 h. Data are normalized to the mean value of the vehicle-treated controls. The bars and error bars represent the mean ± sd values of at least two experiments performed in triplicate. +++, P < 0.001 vs. vehicle, P4, or TNFα; ###, P < 0.001 vs. vehicle, P4, or IFNγ; ∧∧∧, P < 0.001 vs. vehicle; ***, P < 0.001 vs. vehicle or TNFα plus IFNγ. B, HES cells were transiently transfected with the hPRA expression plasmid and treated for 24 h with vehicle or different treatments as indicated above. Data are normalized to the mean value of the vehicle-treated controls. The bars and error bars indicate the mean ± sd values representative of at least two experiments performed in triplicate. **, P < 0.01 vs. vehicle or P; ***, P < 0.001 vs. vehicle or P; ∧∧∧, P < 0.001 vs. vehicle.

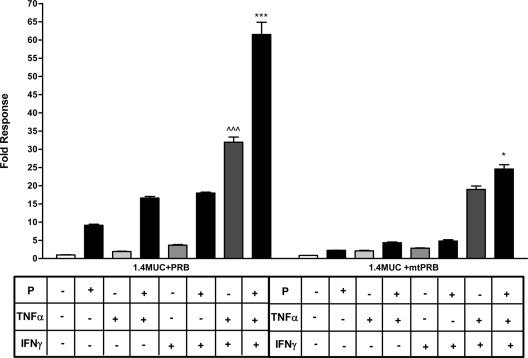

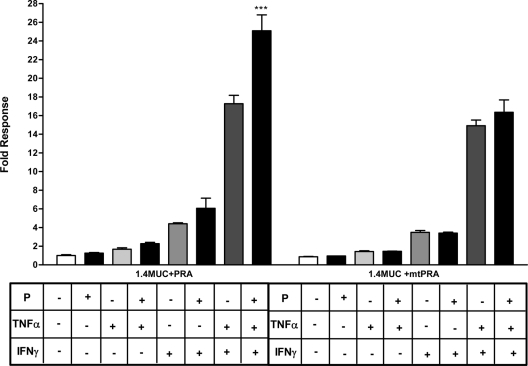

Cooperative stimulation of MUC1 promoter activity by cytokines and P requires the DNA-binding domain (DBD) of PRB and PRA

We previously demonstrated that PRB-mediated P response of the MUC1 promoter requires the DBD of the PRB (19). To determine whether the DBD of the PRB is required for cooperative induction of MUC1 promoter activity by P and cytokines, HES cells were transiently transfected with either the wild-type hPRB or mtPRB (an expression plasmid containing PRB with a point mutation in the DBD) and 1.4MUC and then treated with 0.25 ng/ml TNFα and/or 2 IU/ml IFNγ and/or 400 nm P (Fig. 4). In the presence of low doses of cytokines and liganded wild-type PRB, efficient stimulation of MUC1 promoter activity similar to that seen in Fig. 3A was observed; however, mutation of the DBD almost completely destroyed P responsiveness in all contexts.

Figure 4.

The DBD of PRB is necessary for cooperative stimulation of MUC1 promoter activity in the presence of cytokines and P. HES cells were transfected with 1.4MUC promoter and hPRB or a mtPRB expression plasmid and treated with vehicle or the indicated treatments (P, 400 nm; TNFα, 0.25 ng/ml; IFNγ, 2 IU/ml) for 24 h. Data are normalized to the mean value of the vehicle-treated controls. The bars and error bars indicate the mean ± sd values representative of at least two experiments performed in triplicate. ∧∧∧, P < 0.001 vs. mtPRB TNFα plus IFNγ treatment; ***, P < 0.001 vs. mtPRB P plus TNFα plus IFNγ treatment; *, P < 0.05 vs. mtPRB TNFα plus IFNγ treatment.

To explore whether the DBD of PRA is also necessary for the stimulation of MUC1 by P and low doses of cytokines, transient transfections in HES cells were performed with 1.4MUC and wild-type hPRA or expression plasmid PRA containing a mutation in the DBD (mtPRA). Similar to the results obtained with mtPRB, we observed that stimulation of MUC1 promoter activity by low doses of cytokines and P also requires the DBD of PRA (Fig. 5). The increase in the stimulation of MUC1 promoter activity is more drastic in the presence of PRB and the combined treatments, relative to PRA. Collectively, our data indicate that DBD of both PR isoforms is necessary for stimulation of MUC1 promoter activity by low doses of cytokines and P.

Figure 5.

The DBD of PRA is necessary for cooperative stimulation of MUC1 promoter activity in the presence of cytokines and P. HES cells were transiently transfected with 1.4MUC promoter and hPRA or mtPRA expression plasmid and treated with vehicle or the indicated treatments (P, 400 nm; TNFα, 0.25 ng/ml; IFNγ, 2 IU/ml) for 24 h. Data are normalized to the mean value of the vehicle-treated controls. The bars and error bars indicate the mean ± sd values representative of at least two experiments performed in triplicate. ***, P < 0.001 vs. mtPRA P plus TNFα plus IFNγ treatment.

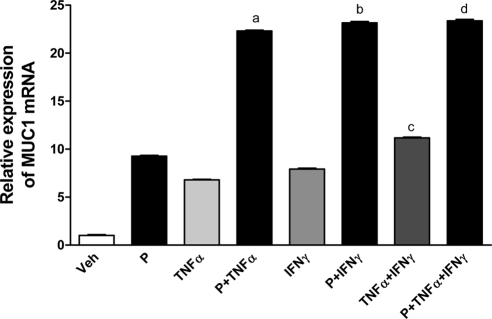

Low doses of cytokines cooperate with P to stimulate MUC1 mRNA and protein expression in HES cells stably transfected with PRB

MUC1 mRNA expression is increased by treatment with TNFα and/or IFNγ (49,50). From our results, we observed that low doses of cytokines enhance liganded PRB stimulation of MUC1 promoter activity. Therefore, we sought to determine whether low doses of cytokines and P stimulate MUC1 mRNA and protein expression in HES cells stably transfected with hPRB. Stably transfected clones were screened for PRB expression by Western blotting. Transient transfection assays with a consensus PRE reporter were performed to determine functionality of PRB (data not shown). MUC1 mRNA expression was analyzed after HES-PRB30 (clone selected for study) cells were treated with low doses of cytokines and P either singly or combinations for 48 h. MUC1 mRNA levels were increased both by individual and combined treatments (Fig. 6). However, combined treatments with P and TNFα or IFNγ resulted in robust induction of MUC1 mRNA expression. A significant increase in MUC1 mRNA expression was observed in cells treated with TNFα or IFNγ alone when compared with individual treatments of TNFα, IFNγ, or P; however, this stimulation did not replicate the degree of response seen in the transient transfection assays. Combined treatment of P, TNFα, and IFNγ increased the level of MUC1 mRNA significantly compared with all other treatments except for the combined treatments of P and IFNγ, indicating significant cooperation between these agents (Fig. 6). Collectively, these data demonstrate that low concentrations of cytokines cooperate with P to elevate MUC1 mRNA levels, although differences in the degree of increase were observed relative to those using transient transfection assays of MUC1 promoter activity.

Figure 6.

MUC1 mRNA expression is elevated by low cytokine doses and P in HES-PRB cells. HES cells stably transfected with hPRB (HES-PRB30) were subjected to the indicated treatments (P, 400 nm; TNFα, 0.25 ng/ml; IFNγ, 2 IU/ml) for 48 h as described in Materials and Methods. Analysis by real-time RT-PCR was performed as described in Materials and Methods. MUC1 mRNA expression was determined relative to that of β-actin. Bars indicate the mean ± sd values of at least two experiments performed in triplicate in each case. a, P < 0.001 vs. vehicle (Veh), P, TNFα, or IFNγ; b, P < 0.001 vs. Veh, P, TNFα, or IFNγ; c, P < 0.001 vs. Veh, P, TNFα, or IFNγ; d, P < 0.001 vs. all treatments except P plus IFNγ.

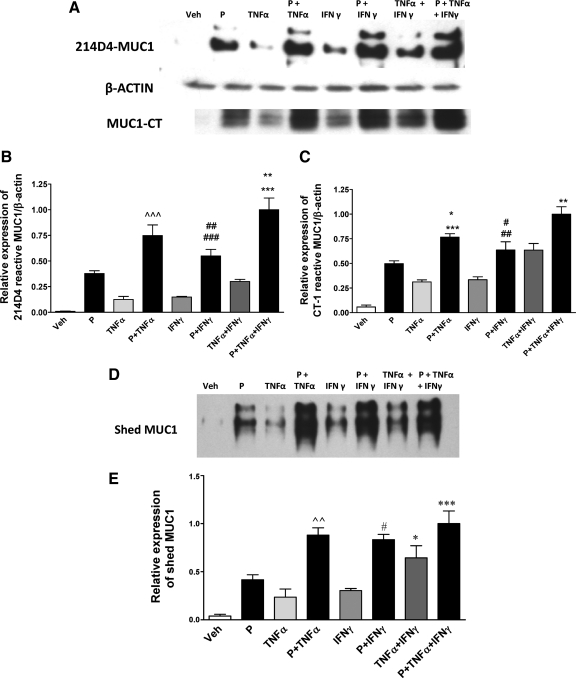

We previously demonstrated that P induces MUC1 protein expression in HEC1A cells stably transfected with PRB (19). In addition, TNFα and IFNγ elevate MUC1 protein expression and increase MUC1 shedding by HES cells (50,56). Therefore, we assessed the ability of these low doses of cytokines and P to regulate MUC1 protein expression in HES-PRB30 cells. HES-PRB30 cells were treated with 0.25 ng/ml TNFα and/or 2 IU/ml IFNγ in the presence or absence of P for 48 h. Cell lysates were probed with MUC1 antibodies, 214D4 and CT-1, or antibodies to β-actin for Western blot analysis (Fig. 7A). The MUC1 antibody, 214D4, is specific for the extracellular domain of MUC1, and CT-1 is specific for the cytoplasmic domain of MUC1. The 214D4-reactive species are mature, highly glycosylated forms of MUC1 (56). Shed or secreted MUC1 was probed with 214D4 antibody alone (Fig. 7D) because the soluble form of MUC1 released in supernatants is devoid of the cytoplasmic tail (50,57).

Figure 7.

Low cytokine concentrations further stimulate MUC1 protein expression and shedding in response to P. HES-PRB30 cells received the indicated treatments (P, 400 nm; TNFα, 0.25 ng/ml; IFNγ, 2 IU/ml) for 48 h as described in Materials and Methods. A, Cell lysates were probed with 214D4, CT-1,and β-actin antibodies by Western blotting as described in Materials and Methods. B and C, Bar graphs represent densitometric analyses of the ratio of MUC1 recognized by 214D4 to β-actin (B) or CT-1 to β-actin (C), respectively. Data are normalized to the mean value of the P- plus TNFα- plus IFNγ-treated samples that displayed maximum stimulation. Bars and error bars indicate mean ± sd values of at least two experiments performed in triplicate in each case. ∧∧∧, P < 0.001 vs. P, TNFα, IFNγ, or TNFα plus IFNγ; ##, P < 0.01 vs. P; ###, P < 0.001 vs. TNFα, IFNγ, or TNFα plus IFNγ; ***, P < 0.001 vs.TNFα plus IFNγ; **, P < 0.01 vs. P plus TNFα for 214D4-reactive MUC1 (B); *, P < 0.05 vs. P; ***, P < 0.001 vs. TNFα, IFNγ, or TNFα plus IFNγ; #, P < 0.05 vs. IFNγ; ##, P < 0.01 vs. TNFα; **, P < 0.01 vs. P plus IFNγ or TNFα plus IFNγ for CT1-reactive MUC1. Western blot analysis of MUC1 expression in culture supernatants from the above treated cells probed with 214D4 antibody. Shed MUC1 was collected in culture supernatants and detected by Western blotting with 214D4 antibody as described in Materials and Methods. A representative Western blot for each treatment is shown at the top and reveal two major bands representing products of the two MUC1 alleles. E, Shed MUC1 was quantified by densitometric analysis and is shown normalized to the mean value of the P- plus TNFα- plus IFNγ-treated samples that displayed maximal shedding. Bars and error bars indicate mean ± sd values representative of at least two experiments performed in triplicate in each case. ***, P < 0.001 vs. TNFα plus IFNγ; #, *, P < 0.05 vs. TNFα plus IFNγ or P; ∧∧, P < 0.01 vs. TNFα plus IFNγ (E). Veh, Vehicle.

Combined treatments with P, TNFα, or IFNγ significantly increased MUC1 protein expression, detected by both 214D4 and CT-1 antibodies (Fig. 7A) compared with individual treatments. MUC1 protein levels in response to TNFα and IFNγ were generally in good agreement with MUC1 mRNA expression studies. Thus, low doses of individual cytokines can cooperate with each other as well as P to further enhance MUC1 protein expression. Shed/secreted MUC1 paralleled changes observed in cell-associated MUC1 protein levels (Fig. 7D). The combined treatment of P, TNFα, and IFNγ only marginally enhances MUC1 protein levels in HES-PRB30 cells beyond levels observed in cells treated with individual cytokines in the presence of P. Collectively, our data indicate that either low-dose cytokine can enhance MUC1 protein expression and shedding in the presence of the other cytokine or P.

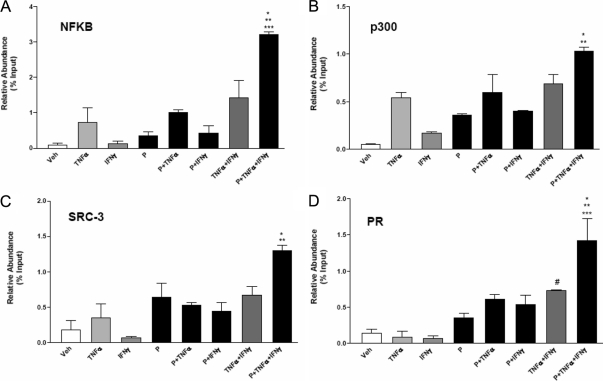

Transcription factor recruitment to the MUC1 promoter by low doses of cytokines and P

To investigate whether differences in MUC1 promoter occupancy by nuclear receptor coregulators or cytokine-activated transcription factors contribute to the differences in MUC1 expression, quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed (Fig. 8). HES-PRB30 cells were treated with cytokines and P, either singly or in combinations, for 1 h before chromatin isolation. Low doses of TNFα recruited the p65 subunit of NFκB to the MUC1 proximal promoter region (−618/−472), which includes binding sites for NFκB, STAT, and P-responsive region. NFκB binding was enhanced by combined treatments of TNFα with P/IFNγ, and further recruitment was observed when P was included with both cytokines (Fig. 8A). Although IFNγ stimulated STAT1 recruitment, no further enhancement of STAT1 binding was observed when P and/or TNFα were included (data not shown). These results indicated that more efficient recruitment of NFκB accounts for enhanced stimulation of MUC1 promoter activity when IFNγ is present. The transcriptional coactivator p300 was recruited efficiently by individual treatments with TNFα or P and very modestly by IFNγ (Fig. 8B). Recruitment of p300 appeared to be further enhanced by combined treatments with P, TNFα, and IFNγ. These results indicate that enhanced p300 recruitment also may contribute to stimulation of MUC1 promoter activity by combined P plus cytokine treatments. We also examined the recruitment of steroid receptor coactivators (SRC) family members SRC1 and SRC3, known to interact with PR. SRC1 (data not shown) and SRC3 association with the MUC1 promoter was higher in the presence of P, but cytokine addition had little further impact on this association (Fig. 8C). We also observed that SRC3 recruitment was stimulated by TNFα and P and enhanced in the presence of combined cytokine treatments and P (Fig. 8C). Quantitative ChIP assays also confirmed the enhanced recruitment of PR to MUC1 promoter under these conditions, particularly when all three treatments were given (Fig. 8D). Taken together, these studies indicate that combined treatments of low doses of cytokines and P stimulate NFκB, p300, SRC3, and PR association with the MUC1 promoter as a means to enhance MUC1 gene transcription.

Figure 8.

Recruitment of transcriptional coactivators to the MUC1 promoter by cytokines and P determined by quantitative ChIP PCR. HES-PRB30 cells were treated with vehicle (Veh) or the indicated treatments (P, 400 nm; TNFα, 0.25 ng/ml; IFNγ, 2 IU/ml) as indicated for 1 h. ChIP assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods with antibodies specific for NFκB (A) (*, P < 0.05 vs. TNFα plus IFNγ; **, P < 0.01 vs. TNFα or P plus TNFα; ***, P < 0.001 vs. Veh, IFNγ, or P), p300 (B) (*, P < 0.05 vs. TNFα or P plus TNFα), SRC3 (C) (*, P < 0.05 vs. TNFα, P plus TNFα, or P plus IFNγ; **, P < 0.01 vs. Veh or IFNγ), PR (D) (#, P < 0.05 vs. TNFα or IFNγ; *, P < 0.05 vs. TNFα plus IFNγ; **, P < 0.01 vs. P plus TNFα or P plus IFNγ; ***, P < 0.001 vs. Veh, IFNγ, P, or TNFα). PCR was performed with primers specific to the −618/−472 region of the MUC1 proximal promoter. Data are presented relative to input chromatin. Bars and error bars indicate mean ± sd values representative of three independent experiments.

Discussion

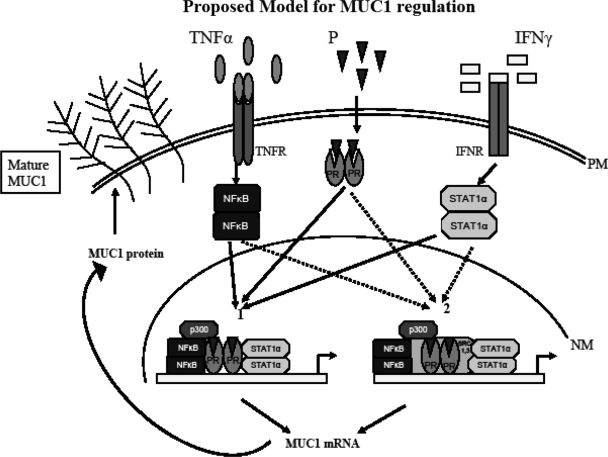

Proinflammatory cytokines are regulated during the menstrual cycle and prepare the endometrium for embryo implantation in concert with steroid hormones and their receptors (58). The potential interactions among cytokine-activated transcription factors and steroid hormone receptors are complex and not necessarily intuitive (12,13,14). Studies of these interactions in natural promoter contexts are essential to understand the impact of these powerful regulators of gene expression. MUC1 is a gene whose product plays important roles in many normal and pathological processes, including reproduction, cancer, and protection of mucosa from infection (1,2,59). MUC1 promoter activity and expression are activated in various cellular contexts by proinflammatory cytokines (18,48,49,50,51,52) including IFNγ and TNFα. These cytokines activate distinct transcription factors that bind to separate sites within the MUC1 promoter (3,5). In addition, MUC1 mRNA and protein expression in the uterus is regulated by E2 and P. In humans, uterine MUC1 expression is highest during the luteal (receptive) phase when P levels are high (12,13,14). The PR isoforms PRA and PRB differentially regulate P-mediated MUC1 gene transcription, with the P responsiveness region mapped to −570/−523 of the MUC1 promoter (19). Liganded PRB stimulates MUC1 promoter activity and protein expression, whereas PRA antagonizes PRB-mediated MUC1 promoter activity (19). PRA is also essential for the P-mediated repression of murine Muc1 in vivo (19). The implantation process not only requires P but also is characterized by changes in the levels of proinflammatory cytokines. Moreover, local infection or inflammation of the female reproductive tract is deleterious to the implantation process and maintenance of pregnancy (60,61). Local cytokine production at sites of inflammation or infection is expected to produce gradients of cytokines emanating from these sites. Although high levels of any single cytokine may be sufficient to drive local expression of MUC1 fully, this response may die out sharply with decreasing cytokine levels. Nonetheless, multiple cytokines are produced at such sites and, in theory, may be able to cooperate to promote expression of MUC1 or related genes to protect mucosa at distal sites within the tissue. Because PRA inhibits PRB stimulation of MUC1 expression, it is not clear whether PRA has a similar quenching function in terms of cytokine-activated MUC1 expression. Because certain species have a PRA-dominated endometrium, such a response potentially could impair mucosal protective responses during P-dominated states, e.g. pregnancy. Therefore, in the present study, we examined the ability of low doses of proinflammatory cytokines as well as PR isoforms to control MUC1 gene expression. A model of our findings is presented in Fig. 9.

Figure 9.

Proposed model for MUC1 regulation. The image depicts two alternative pathways for regulation of MUC1 gene expression by interactions between PR isoforms and cytokine-activated transcription factors. During the receptive phase, P, TNFα, and IFNγ enrich the uterine milieu. At the plasma membrane (PM), proinflammatory cytokines TNFα and IFNγ bind to their respective receptors, TNFR and IFNR, activating downstream transcription factors NFκB and STAT1α. Binding of P to PR activates PR. Pathway 1 illustrates PR isoforms interacting with NFκB and STAT1α and the transcriptional coactivator p300 to regulate MUC1 gene expression. The important role players in this pathway are NFκB and p300. Pathway 2 illustrates MUC1 expression by interaction between NFκB, STAT1α, p300, nuclear SRC-1 and SRC-3, and activated PR isoforms. Interactions from either pathway result in increased MUC1 mRNA and protein expression. Highly glycosylated (mature) MUC1 reaches the plasma membrane. High levels of mature MUC1 expression on luminal epithelia at the receptive phase inhibit embryo implantation. LE, Luminal epithelia; NM, nuclear membrane.

Most studies on MUC1 transcriptional regulation have employed high doses of single cytokines. A relatively small increase in MUC1 promoter activity is observed in HES cells treated with 0.25 ng/ml TNFα or 2 IU/ml IFNγ. We observed that combined treatments with these cytokine concentrations synergistically enhanced MUC1 promoter activity in HES cells. Interestingly, these doses are within the range found in serum of women with unsuccessful pregnancies (34,53,54).

In the presence of PRA or PRB, low concentrations of TNFα and IFNγ enhanced MUC1 promoter activity. In contrast to its inhibitory action on PRB, liganded PRA further enhanced cytokine-stimulated MUC1 promoter activity. Cross talk between STAT family members and PR have been reported previously in different cellular and promoter contexts (62,63,64,65). We also observed that liganded PR isoforms cooperate with TNFα to stimulate MUC1 gene activity in HES cells. This observation is in contrast with transcriptional studies reporting negative cross talk between PR and NFκB (55,66). The positive association of liganded PR and NFκB in the regulation of MUC1 could be attributed to increased recruitment of transcriptional cofactors in response to P (24) or TNFα (67). Additionally, transcription factors are known to interact with PR and regulate gene transcription in a PRE-independent manner (68). Phosphorylation of PR integrates signals from various pathways contributing to regulation of gene transcription in a ligand-dependent and ligand-independent manner (62,69).

Liganded PRB and cytokines enhance MUC1 promoter activity greatly in comparison with liganded PRA and combined cytokines. Differences in activity between the PR isoforms are associated with functions of the unique activation domain (AF-3) in PRB (23,70) and distinct cofactor binding among the isoforms (24). We observed that mutations in the DBD almost completely destroyed the ability of either PR isoform to further stimulate MUC1 promoter activity in the presence of cytokines. These data suggest that in the context of MUC1 gene regulation by cytokines and P, binding of PR to the P-responsive region of MUC1 promoter is essential. Alternatively, it is possible that PR isoforms on the MUC1 promoter interact with other transcription factors that are recruited for transactivation of the MUC1 promoter, and mutation of the DBD affects this cooperative network. However, liganded PR can be tethered indirectly to promoters lacking PRE and interact with transcription factors to regulate gene activity (68). Such observations underscore the complexity of gene regulation by PR isoforms. Stimulation of cytokine-activated MUC1 promoter activity by the unliganded DBD mutant of PRA was not greatly reduced when compared with these treatments in the presence of unliganded wild-type PRA. Cytokine-mediated PRA stimulation of MUC1 promoter activity could be due to binding of transcriptional coactivators, i.e. activated NFκB or p300, in this regard.

ChIP assays provide a more detailed understanding of the regulation of MUC1 promoter activity by PR isoforms and the low doses of cytokines. Low concentrations of TNFα treatment recruit the p65 subunit of NFκB to the MUC1 promoter. This association of NFκB was augmented by the addition of IFNγ. Thus, activation of transcription factors besides NFκB appeared to more efficiently recruit or stabilize NFκB association with the MUC1 promoter. As expected, IFNγ recruited STAT1 to the MUC1 promoter; however, no further increase in STAT1 binding was observed in combined treatments with TNFα and/or P. Therefore, it appears that synergistic stimulation of MUC1 transcriptional activity by low doses of cytokines is primarily due to increased NFκB recruitment. Mechanisms for TNFγ and IFNγ synergy include IFNγ augmentation of NFκB activation via rapid IκB degradation and is dependent on protein tyrosine kinase activity depending on the cell type (71). It is thus possible that MUC1 promoter activity is regulated by an integrated signaling cascade (62,63,65,68,72). Individual treatments with TNFα or P enhanced p300 recruitment to the MUC1 promoter with the highest signal observed when P was combined with both cytokines. Another transcriptional coactivator, CREB-binding protein (CBP) p300, has histone acetyltransferase activity and serves to bridge factors between cytokine-activated factors, PRs, and basal transcription machinery to activate transcription in other contexts (67,68,73,74,75). Our data indicate that SRC1 and SRC3 also contribute to MUC1 promoter activity stimulation in response to P, P plus combined cytokine treatments, and TNFα in case of SRC3. We found no significant difference in CBP or mediator complex subunit-1 recruitment among the different treatments by ChIP assays (data not shown). Therefore, increased association between NFκB, p300, SRC3, and PR appear to contribute to stimulation of MUC1 promoter activity. Thus, ChIP assays indicate that the enhanced transcriptional activation of the MUC1 promoter in the presence of combined cytokine plus P treatment involves changes in the recruitment of numerous cofactors, but most notably NFκB, p300, and SRC3.

We also found low doses of either cytokine cooperates with P to stimulate MUC1 mRNA and protein expression. Notably, P plus either cytokine alone gave near maximal elevation of MUC1 mRNA and protein levels. These responses differed in some respects from the promoter activity assays. Several factors might account for these discrepancies. PR-mediated stimulation of endogenous MUC1 expression may be influenced by the accessibility of transcription factors and chromatin arrangements in the plasmids used in transient transfection assays. Additionally, posttranscriptional controls, i.e. MUC1 effects on mRNA stability, may contribute to these differences and warrant further investigation.

In summary, we demonstrate that MUC1 gene expression is regulated in a complex fashion by transcriptional coactivators recruited by treatment with low concentrations of the cytokines TNFα and IFNγ as well as P. Efficient recruitment of NFκB and p300, PR interactions with SRC1 and SRC3, and STAT1 association on the proximal MUC1 promoter region contribute to a high level of stimulation of MUC1 transcriptional activity. Furthermore, while acting as an inhibitor of PRB activation of MUC1 expression, PRA works in conjunction with cytokine-activated transcription factors to stimulate MUC1 gene activity. Ultimately, the coordinated actions of these factors stimulate high levels of MUC1 protein expression with important biological consequences in both normal and pathological contexts. Understanding these molecular controls may help in developing the means to control MUC1 expression to improve implantation success, enhance mucosal protection, or reduce MUC1 expression by tumor cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

The human uterine epithelial cell line HES was kindly provided by Dr. Doug Kniss (Ohio State University, Columbus, OH). HES cells routinely were maintained at 37 C in an atmosphere of air/CO2 [95:5 (vol/vol)] in DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 5% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA) and 1 mm sodium pyruvate (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). Before experiments, cells were seeded on plates coated with growth factor-reduced Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) in DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) charcoal-stripped FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT) and 1 mm sodium pyruvate for 48 h.

Plasmids

The 1.4MUC promoter-luciferase, PRE reporter constructs, hPRB and mtPRB, hPRA and mtPRA, and pSG5 plasmids were used for transient transfection assays. The generation of these plasmids has been described previously (18,19). pGL3-control, pGL3-basic, and pRL-TK plasmids were obtained from Promega (Madison, WI).

Transient transfection and reporter assays

HES cells were plated in six-well plates coated with growth factor-reduced Matrigel and maintained as described above until cells reached 90–95% confluence. Transient transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 and Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Two hundred fifty nanograms of the reporter plasmid, 75 ng of the expression plasmids, 32.5 ng of pRL-TK plasmid, and 4 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 were used per well. pSG5 empty vector was added to wells in the dose-response experiments to keep the amount of plasmid DNA constant. Cells with liposome-DNA complexes were incubated for 6 h. Cells then were incubated overnight in fresh DMEM containing 10% (vol/vol) charcoal-stripped FBS. All treatments were performed in 10% (vol/vol) charcoal-stripped serum-containing media. Cells were treated with 400 nm P (Sigma), 0.25 ng/ml recombinant human TNFα (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), 2 IU/ml recombinant human IFNγ, (Roche), and/or vehicle [0.001% ethanol (vol/vol) and 0.01% (wt/vol) BSA in PBS for 24 h]. Cell lysates were collected using the dual-luciferase assay kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and luciferase assays were performed using a Dynex MLX microplate luminometer (Dynex Technologies, Chantilly, VA). Reporter activity was expressed as the ratio of firefly luciferase activity to Renilla luciferase activity.

Stable transfections

HES cells were cotransfected with the hPRB expression vector and pPUR plasmid (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) and selected for puromycin resistance. Transfections were done in Opti-MEM using Lipofectamine 2000, and selection was continued in DMEM containing 5% (vol/vol) FBS and 175 ng/ml of puromycin (Sigma). PRB expression in stably transfected clones was analyzed by Western blotting using anti-PgR Ab-8 (Neomarkers, Fremont, CA). Transient transfections with PRE reporter construct was used to determine functionality of PRB in the selected clones. P treatment (400 nm) enhanced PRE-driven luciferase activity 6- to 7-fold relative to vehicle-treated controls in these cells.

Immunoblotting

HES cells stably expressing PRB (HES-PRB30) were plated in 24-well plates coated with growth factor-reduced Matrigel (BD Biosciences) and maintained as described until cells reached 75% confluence. Cells were serum starved for 24 h before treatment. Cells were incubated in fresh serum-free medium with vehicle alone [0.001% (vol/vol) ethanol and 0.01% (wt/vol) BSA in PBS], P (400 nm), TNFα (0.25 ng/ml), and IFNγ (2 IU/ml) as indicated for 48 h. Culture supernatants were collected and samples prepared as described previously (16). Cell lysates were collected with sample extraction buffer [0.05 m Tris (pH 7), 8 m urea, 1% (wt/vol) urea, 1% (vol/vol) β-mercaptoethanol, and protease inhibitor cocktail mix at 1:100 dilution (Sigma)], and protein concentration was determined by the method of Lowry et al. (76). Fifteen micrograms of protein was separated by SDS-PAGE using a 5% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide Laemmli stacking gel and a 10% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide Porzio and Pearson resolving gel (77,78). Proteins then were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes at 4 C. Blots were blocked at 4 C in PBS plus 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 containing 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dry milk for 6 h. The 214D4 primary antibody (kindly provided by Dr. John Hilkens, The Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) was added to a final dilution of 1:2500 and incubated overnight at 4 C. Blots were rinsed three times for 5 min each at room temperature and incubated for 2 h at 4 C with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated sheep antimouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) at a final dilution of 1:200,000 in blocking solution. Finally, the blots were rinsed three times for 5 min each, and signal intensities were detected using the ECL system (Pierce, Rockford, IL) as described by the manufacturer. Twenty five micrograms of protein was used for blots probed with CT-1, an antibody that recognizes all cell-associated forms of MUC1, at a final dilution of 1:2000 as previously described (56). Blots used for detection of cell-associated MUC1 subsequently were immunoblotted with anti-β-actin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) to control for differences in loading and transfer efficiencies.

RNA isolation and real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from HES-PRB30 cells after treatments as described previously using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and digested with deoxyribonuclease I with the DNA-free kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription was carried out using 1 μg total RNA in a total reaction of 20 μl using the Omniscript RT kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) at 37 C for 1 h following the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR were performed using the primer sequences MUC1 forward 5′-AGAGAAGTTCAGTGCCCAGC-3′ and reverse 5′-TGACATCCTGTCCCTGAGTG-3′, ACT-B forward 5′-GATGAGATTGGCATGGCTTT-3′ and reverse 5′-CACCTTCACCGTTCCAGTTT-3′, and SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Samples were cycled for 15 sec at 95 C and 60 sec at 58 C for 45 cycles. The relative amounts of MUC1 mRNA were identified using the comparative threshold cycle method by ABI Prism 7000 SDS software (User Bulletin No.2, ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System; Applied Biosystems).

ChIP assays

HES-PRB30 cells were grown in 150-cm2 flasks in DMEM supplemented with 5% (vol/vol) FBS and 1 mm sodium pyruvate for 48 h and then switched to DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) charcoal-stripped FBS and 1 mm sodium pyruvate until cells attained 70–80% confluency. Cells then were serum starved for 24 h before treatments. Cells were treated in fresh serum-free medium with vehicle alone [0.001% (vol/vol) ethanol and 0.01% (wt/vol) BSA in PBS], P (400 nm), TNFα (0.25 ng/ml), and IFNγ (2 IU/ml) as indicated for 1 h. Cell fixation was carried out with 1% (wt/vol) formaldehyde in DMEM for 10 min at room temperature, followed by one wash using ice-cold PBS. The fixation reaction was stopped with the addition of glycine-stop fix solution (CHIP-IT Express; Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) for 15 min. Cells then were scraped from flasks with 10 ml PBS plus 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, centrifuged for 5 min at 1000 rpm for 5 min. Cell pellets were frozen and stored at −80 C with the addition of 1 μl 100 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 1 μl protease inhibitor cocktail (CHIP-IT Express). Preparation of chromatin by sonication shearing and immunoprecipitation was done using buffers supplied in CHIP-IT Express or ChIP IT (for quantitative ChIP) ChIP kit, following the manufacturer’s protocol. Optimized sonication conditions were three 30-sec pulses on ice at a setting of output of 4 and 85% duty cycle to reduce chromatin to a length of 200–500 bp. For immunoprecipitation reactions, 50 μl isolated chromatin was incubated with 2 μg of each antibody or appropriate controls at 4 C overnight. Affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies against NFκB p65 (sc-372x), TRAP220 (mediator −1; sc-8998), p300 (sc-585x), STAT1 p84/91 (sc-592x), SRC-1 (sc-6096x), and NCoA-3/SRC-3 (sc9119x) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), and antibody against KAT3A/CBP (ab-2832) was obtained from Abcam for ChIP reactions. Primers specific to the −618/−472 region of the MUC1 promoter (forward 5′-CTTTCTCCAAGGAGGGAACC-3′ and reverse 5′-GAGTGGACTAGGTGCTAGTT-3′) at an annealing temperature of 58 C or 55 C (for quantitative ChIP) was used to amplify a 146-bp product and visualized as described earlier (19).

Statistical analysis

Data are shown as the means ± sd of triplicate samples and are representative of at least two independent experiments. All data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer multiple-comparisons test using the GraphPad InStat version 3.05 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the insightful discussions with Dr. Cindy Farach-Carson, Dr. Melissa Brayman, JoAnne Julian, and members of the Carson/Farach-Carson labs. We greatly appreciate the expert secretarial assistance of Ms. Sharron Kingston. We thank Dr. John Hilkens for providing the 214D4 antibody.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant HD 29963 to D.D.C. and University of Delaware Dissertation Fellow award to N.D.

Current address for N.D.: Department of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Wiess School of Natural Sciences, Rice University, Houston, Texas 77251.

Current address for P.W.: Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online October 20, 2010

Abbreviations: ChIP, Chromatin immunoprecipitation; CBP, CREB-binding protein; DBD, DNA-binding domain; E2, estrogen; ER, E2 receptor; FBS, fetal bovine serum; IFNγ, interferon γ; IFNγR, IFNγ receptor; MUC1, mucin 1; NFκB, nuclear factor κB; P, progesterone; PR, P receptor; SRC, steroid receptor coactivator; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; TNFR, TNF receptor.

References

- Brayman M, Thathiah A, Carson DD 2004 MUC1: a multifunctional cell surface component of reproductive tissue epithelia. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2:4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendler SJ 2001 MUC1, the renaissance molecule. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 6:339–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendler SJ, Spicer AP 1995 Epithelial mucin genes. Annu Rev Physiol 57:607–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thathiah A, Carson DD 2002 Mucins and blastocyst attachment. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 3:87–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagow E, DeSouza MM, Carson DD 1999 Mammalian reproductive tract mucins. Hum Reprod Update 5:280–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilkens J, Ligtenberg MJ, Vos HL, Litvinov SV 1992 Cell membrane-associated mucins and their adhesion-modulating property. Trends Biochem Sci 17:359–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSouza MM, Mani SK, Julian J, Carson DD 1998 Reduction of mucin-1 expression during the receptive phase in the rat uterus. Biol Reprod 58:1503–1507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hild-Petito S, Fazleabas AT, Julian J, Carson DD 1996 Mucin (Muc-1) expression is differentially regulated in uterine luminal and glandular epithelia of the baboon (Papio anubis). Biol Reprod 54:939–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surveyor GA, Gendler SJ, Pemberton L, Das SK, Chakraborty I, Julian J, Pimental RA, Wegner CC, Dey SK, Carson DD 1995 Expression and steroid hormonal control of Muc-1 in the mouse uterus. Endocrinology 136:3639–3647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen JA, Bazer FW, Burghardt RC 1996 Spatial and temporal analyses of integrin and Muc-1 expression in porcine uterine epithelium and trophectoderm in vivo. Biol Reprod 55:1098–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman LH, Olson GE, Carson DD, Chilton BS 1998 Progesterone and implanting blastocysts regulate Muc1 expression in rabbit uterine epithelium. Endocrinology 139:266–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hey NA, Graham RA, Seif MW, Aplin JD 1994 The polymorphic epithelial mucin MUC1 in human endometrium is regulated with maximal expression in the implantation phase. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 78:337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hey NA, Li TC, Devine PL, Graham RA, Saravelos H, Aplin JD 1995 MUC1 in secretory phase endometrium: expression in precisely dated biopsies and flushings from normal and recurrent miscarriage patients. Hum Reprod 10:2655–2662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLoia JA, Krasnow JS, Brekosky J, Babaknia A, Julian J, Carson DD 1998 Regional specialization of the cell membrane-associated, polymorphic mucin (MUC1) in human uterine epithelia. Hum Reprod 13:2902–2909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meseguer M, Aplin JD, Caballero-Campo P, O'Connor JE, Martín JC, Remohí J, Pellicer A, Simón C 2001 Human endometrial mucin MUC1 is up-regulated by progesterone and down-regulated in vitro by the human blastocyst. Biol Reprod 64:590–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thathiah A, Blobel CP, Carson DD 2003 Tumor necrosis factor-α converting enzyme/ADAM 17 mediates MUC1 shedding. J Biol Chem 278:3386–3394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thathiah A, Carson DD 2004 MT1-MMP mediates MUC1 shedding independent of TACE/ADAM17. Biochem J 382:363–373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brayman MJ, Dharmaraj N, Lagow E, Carson DD 2007 MUC1 expression is repressed by protein inhibitor of activated signal transducer and activator of transcription-y. Mol Endocrinol 21:2725–2737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brayman MJ, Julian J, Mulac-Jericevic B, Conneely OM, Edwards DP, Carson DD 2006 Progesterone receptor isoforms A and B differentially regulate MUC1 expression in uterine epithelial cells. Mol Endocrinol 20:2278–2291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, DeSouza MM, Julian J, Gendler SJ, Carson DD 1998 Estrogen receptor does not directly regulate the murine Muc-1 promoter. Mol Cell Endocrinol 143:65–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaretsky JZ, Barnea I, Aylon Y, Gorivodsky M, Wreschner DH, Keydar I 2006 MUC1 gene overexpressed in breast cancer: structure and transcriptional activity of the MUC1 promoter and role of estrogen receptor α (ERα) in regulation of the MUC1 gene expression. Mol Cancer 5:57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen DX, Xu YF, Mais DE, Goldman ME, McDonnell DP 1994 The A and B isoforms of the human progesterone receptor operate through distinct signaling pathways within target cells. Mol Cell Biol 14:8356–8364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartorius CA, Melville MY, Hovland AR, Tung L, Takimoto GS, Horwitz KB 1994 A third transactivation function (AF3) of human progesterone receptors located in the unique N-terminal segment of the B-isoform. Mol Endocrinol 8:1347–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giangrande PH, Kimbrel EA, Edwards DP, McDonnell DP 2000 The opposing transcriptional activities of the two isoforms of the human progesterone receptor are due to differential cofactor binding. Mol Cell Biol 20:3102–3115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan BG, O'Malley BW 2000 Progesterone receptor coactivators. Steroids 65:545–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory CW, Wilson EM, Apparao KB, Lininger RA, Meyer WR, Kowalik A, Fritz MA, Lessey BA 2002 Steroid receptor coactivator expression throughout the menstrual cycle in normal and abnormal endometrium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:2960–2966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiozawa T, Shih HC, Miyamoto T, Feng YZ, Uchikawa J, Itoh K, Konishi I 2003 Cyclic changes in the expression of steroid receptor coactivators and corepressors in the normal human endometrium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:871–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson DD, Bagchi I, Dey SK, Enders AC, Fazleabas AT, Lessey BA, Yoshinaga K 2000 Embryo implantation. Dev Biol 223:217–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey SK, Lim H, Das SK, Reese J, Paria BC, Daikoku T, Wang H 2004 Molecular cues to implantation. Endocr Rev 25:341–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt JS, Chen HL, Hu XL, Tabibzadeh S 1992 Tumor necrosis factor-α messenger ribonucleic acid and protein in human endometrium. Biol Reprod 47:141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird SM, Tuckerman EM, Saravelos H, Li TC 1996 The production of tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α) by human endometrial cells in culture. Hum Reprod 11:1318–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabibzadeh S 1991 Ubiquitous expression of TNF-α/cachectin immunoreactivity in human endometrium. Am J Reprod Immunol 26:1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabibzadeh S, Satyaswaroop PG, von Wolff M, Strowitzki T 1999 Regulation of TNF-α mRNA expression in endometrial cells by TNF-α and by oestrogen withdrawal. Mol Hum Reprod 5:1141–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkin SS, Liu HC, Davis OK, Rosenwaks Z 1991 Tumor necrosis factor is present in maternal sera and embryo culture fluids during in vitro fertilization. J Reprod Immunol 19:85–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabibzadeh S, Zupi E, Babaknia A, Liu R, Marconi D, Romanini C 1995 Site and menstrual cycle-dependent expression of proteins of the tumour necrosis factor (TNF) receptor family, and BCL-2 oncoprotein and phase-specific production of TNFα in human endometrium. Hum Reprod 10:277–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey AM, Dellow K, Blayney M, Macnamee M, Charnock-Jones S, Smith SK 1995 Stage-specific expression of cytokine and receptor messenger ribonucleic acids in human preimplantation embryos. Biol Reprod 53:974–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghupathy R, Makhseed M, Azizieh F, Hassan N, Al-Azemi M, Al-Shamali E 1999 Maternal Th1- and Th2-type reactivity to placental antigens in normal human pregnancy and unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortions. Cell Immunol 196:122–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorivodsky M, Zemlyak I, Orenstein H, Savion S, Fein A, Torchinsky A, Toder V 1998 TNF-α messenger RNA and protein expression in the uteroplacental unit of mice with pregnancy loss. J Immunol 160:4280–4288 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron RL, Nestel FP, Lapp WS, Baines MG 1990 Lipopolysaccharide-induced fetal resorption in mice is associated with the intrauterine production of tumour necrosis factor-α. J Reprod Fertil 90:395–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeaman GR, Collins JE, Currie JK, Guyre PM, Wira CR, Fanger MW 1998 IFN-γ is produced by polymorphonuclear neutrophils in human uterine endometrium and by cultured peripheral blood polymorphonuclear neutrophils. J Immunol 160:5145–5153 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arck PC, Troutt AB, Clark DA 1997 Soluble receptors neutralizing TNF-α and IL-1 block stress-triggered murine abortion. Am J Reprod Immunol 37:262–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JA, Polgar K, Anderson DJ 1995 T-helper 1-type immunity to trophoblast in women with recurrent spontaneous abortion. JAMA 273:1933–1936 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Li Q, Dua A, Ying YK, Bagchi MK, Bagchi IC 2001 Messenger ribonucleic acid encoding interferon-inducible guanylate binding protein 1 is induced in human endometrium within the putative window of implantation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:2420–2427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkar AA, Croy BA 2001 Functions of uterine natural killer cells are mediated by interferon γ production during murine pregnancy. Semin Immunol 13:235–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkar AA, Di Santo JP, Croy BA 2000 Interferon γ contributes to initiation of uterine vascular modification, decidual integrity, and uterine natural killer cell maturation during normal murine pregnancy. J Exp Med 192:259–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattsson R, Mattsson A, Holmdahl R, Scheynius A, Van der Meide PH 1992 In vivo treatment with interferon-γ during early pregnancy in mice induces strong expression of major histocompatibility complex class I and II molecules in uterus and decidua but not in extra-embryonic tissues. Biol Reprod 46:1176–1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S, McGuckin MA, Hurst T, Ward BG 1994 Effect of interferon-γ and TNF-α on MUC1 mucin expression in ovarian carcinoma cell lines. Dis Markers 12:43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga T, Kuwahara I, Lillehoj EP, Lu W, Miyata T, Isohama Y, Kim KC 2007 TNF-α induces MUC1 gene transcription in lung epithelial cells: its signaling pathway and biological implication. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293:L693–L701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagow EL, Carson DD 2002 Synergistic stimulation of MUC1 expression in normal breast epithelia and breast cancer cells by interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α. J Cell Biochem 86:759–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thathiah A, Brayman M, Dharmaraj N, Julian JJ, Lagow EL, Carson DD 2004 Tumor necrosis factor α stimulates MUC1 synthesis and ectodomain release in a human uterine epithelial cell line. Endocrinology 145:4192–4203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy PK, Gold DV, Cardillo TM, Goldenberg DM, Li H, Burton JD 2003 Interferon-γ upregulates MUC1 expression in haematopoietic and epithelial cancer cell lines, an effect associated with MUC1 mRNA induction. Eur J Cancer 39:397–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaemers IC, Vos HL, Volders HH, van der Valk SW, Hilkens J 2001 A STAT-responsive element in the promoter of the episialin/MUC1 gene is involved in its overexpression in carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem 276:6191–6199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meekins JW, McLaughlin PJ, West DC, McFadyen IR, Johnson PM 1994 Endothelial cell activation by tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and the development of pre-eclampsia. Clin Exp Immunol 98:110–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naz RK, Butler A, Witt BR, Barad D, Menge AC 1995 Levels of interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α in sera and cervical mucus of fertile and infertile women: implication in infertility. J Reprod Immunol 29:105–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkhoven E, Wissink S, van der Saag PT, van der Burg B 1996 Negative interaction between the RelA(p65) subunit of NF-κB and the progesterone receptor. J Biol Chem 271:6217–6224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Julian JA, Carson DD 2008 The MUC1 HMFG1 glycoform is a precursor to the 214D4 glycoform in the human uterine epithelial cell line, HES. Biol Reprod 78:290–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian J, Carson DD 2002 Formation of MUC1 metabolic complex is conserved in tumor-derived and normal epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 293:1183–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly RW, King AE, Critchley HO 2001 Cytokine control in human endometrium. Reproduction 121:3–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuley JL, Linden SK, Png CW, King RM, Pennington HL, Gendler SJ, Florin TH, Hill GR, Korolik V, McGuckin MA 2007 MUC1 cell surface mucin is a critical element of the mucosal barrier to infection. J Clin Invest 117:2313–2324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSouza MM, Surveyor GA, Price RE, Julian J, Kardon R, Zhou X, Gendler S, Hilkens J, Carson DD 1999 MUC1/episialin: a critical barrier in the female reproductive tract. J Reprod Immunol 45:127–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero R, Espinoza J, Mazor M 2004 Can endometrial infection/inflammation explain implantation failure, spontaneous abortion, and preterm birth after in vitro fertilization? Fertil Steril 82:799–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange CA 2004 Making sense of cross-talk between steroid hormone receptors and intracellular signaling pathways: who will have the last word? Mol Endocrinol 18:269–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richer JK, Lange CA, Manning NG, Owen G, Powell R, Horwitz KB 1998 Convergence of progesterone with growth factor and cytokine signaling in breast cancer. Progesterone receptors regulate signal transducers and activators of transcription expression and activity. J Biol Chem 273:31317–31326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoumpoulidou G, Jones MC, Fernandez de Mattos S, Francis JM, Fusi L, Lee YS, Christian M, Varshochi R, Lam EW, Brosens JJ 2004 Convergence of interferon-γ and progesterone signaling pathways in human endometrium: role of PIASy (protein inhibitor of activated signal transducer and activator of transcription-y). Mol Endocrinol 18:1988–1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange CA, Richer JK, Shen T, Horwitz KB 1998 Convergence of progesterone and epidermal growth factor signaling in breast cancer. Potentiation of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. J Biol Chem 273:31308–31316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay LI, Cidlowski JA 1998 Cross-talk between nuclear factor-κB and the steroid hormone receptors: mechanisms of mutual antagonism. Mol Endocrinol 12:45–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen ME, Williams AJ, Neish AS, Moore S, Shi Y, Collins T 1997 CREB-binding protein/p300 are transcriptional coactivators of p65. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:2927–2932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen GI, Richer JK, Tung L, Takimoto G, Horwitz KB 1998 Progesterone regulates transcription of the p21(WAF1) cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor gene through Sp1 and CBP/p300. J Biol Chem 273:10696–10701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel AR, Knutson TP, Lange CA 2009 Signaling inputs to progesterone receptor gene regulation and promoter selectivity. Mol Cell Endocrinol 308:47–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung L, Abdel-Hafiz H, Shen T, Harvell DM, Nitao LK, Richer JK, Sartorius CA, Takimoto GS, Horwitz KB 2006 Progesterone receptors (PR)-B and -A regulate transcription by different mechanisms: AF-3 exerts regulatory control over coactivator binding to PR-B. Mol Endocrinol 20:2656–2670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheshire JL, Baldwin Jr AS 1997 Synergistic activation of NF-κB by tumor necrosis factor α and γ interferon via enhanced IκBα degradation and de novo IκBβ degradation. Mol Cell Biol 17:6746–6754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards DP, Wardell SE, Boonyaratanakornkit V 2002 Progesterone receptor interacting coregulatory proteins and cross talk with cell signaling pathways. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 83:173–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanden Berghe W, De Bosscher K, Boone E, Plaisance S, Haegeman G 1999 The nuclear factor-κB engages CBP/p300 and histone acetyltransferase activity for transcriptional activation of the interleukin-6 gene promoter. J Biol Chem 274:32091–32098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JJ, Vinkemeier U, Gu W, Chakravarti D, Horvath CM, Darnell Jr JE 1996 Two contact regions between Stat1 and CBP/p300 in interferon γ signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:15092–15096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojciak JM, Martinez-Yamout MA, Dyson HJ, Wright PE 2009 Structural basis for recruitment of CBP/p300 coactivators by STAT1 and STAT2 transactivation domains. EMBO J 28:948–958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ 1951 Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 193:265–275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porzio MA, Pearson AM 1977 Improved resolution of myofibrillar proteins with sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Biochim Biophys Acta 490:27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK 1970 Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.