Abstract

This article examines the decision of Hurricane Katrina evacuees to return to their pre-Katrina areas and documents how the composition of the Katrina-affected region changed over time. Using data from the Current Population Survey, we show that an evacuee’s age, family income, and the severity of damage in an evacuee’s county of origin are important determinants of whether an evacuee returned during the first year after the storm. Blacks were less likely to return than whites, but this difference is primarily related to the geographical pattern of storm damage rather than to race per se. The difference between the composition of evacuees who returned and the composition of evacuees who did not return is the primary force behind changes in the composition of the affected areas in the first two years after the storm. Katrina is associated with substantial shifts in the racial composition of the affected areas (namely, a decrease in the percentage of residents who are black) and an increasing presence of Hispanics. Katrina is also associated with an increase in the percentage of older residents, a decrease in the percentage of residents with low income/education, and an increase in the percentage of residents with high income/education.

Hurricane Katrina, which struck the Gulf Coast in August 2005, has had lasting and farreaching effects. Katrina caused massive flooding in New Orleans and catastrophic damage along the Gulf coasts of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. Before making landfall and in its wake, Katrina caused one of the largest and most abrupt relocations of people in U.S. history: approximately 1.5 million people aged 16 years and older evacuated from their homes (Groen and Polivka 2008b). Katrina was responsible for an estimated $96 billion of property damage (The White House 2006) and more than 1,800 deaths (Knabb, Rhome, and Brown 2005), making it the costliest and one of the deadliest hurricanes ever to strike the United States.

The sheer magnitude of the physical destruction and evacuation makes the effects of Katrina worth studying. Analyzing these effects is also important for the study of disasters more generally. Disaster research has long acknowledged that natural disasters evolve into social disasters based on the interaction of individuals and social structures with natural events (Fothergill, Maestas, and Darlington 1999; Fritz 1961; Kreps 1984; Quarantelli and Dynes 1977). Studies of previous disasters have found that socioeconomic status and being a member of a minority group are significant predictors of individuals suffering severe physical and psychological impacts of disasters (Bolin and Stanford 1998; Fothergill et al. 1999; Peacock and Girard 1997). Disaster research has also documented that socioeconomic status plays an important role during the recovery from a disaster—with more-advantaged groups able to recover more quickly and more completely (Bolin and Bolton 1986; Peacock, Morrow, and Gladwin 1997)—and that disasters tend to increase the concentration of poorer, more socially disadvantaged populations on less-desirable land (Girard and Peacock 1997; Pais and Elliott 2008).

An understudied aspect of disasters is the analysis of who returns to an area after evacuating. Given the scale of the evacuation both before and after Katrina, analysis of return migration is crucial to understanding the impact of the storm on the well-being of evacuees and on the social and economic structure of areas affected by the storm. While evacuees are deciding whether to return, individuals who never lived in the affected areas may decide to migrate to these areas. The decisions of evacuees and potential in-migrants influence the demographic composition of the storm-affected areas and thus may change community priorities and the cultural milieu of these areas.

This article examines the decision of evacuees to return to their pre-Katrina areas (through October 2006) and documents how the composition of the Katrina-affected region changed over time (through November 2007). Our empirical analysis has two primary components. First, we investigate the roles of demographic characteristics, public and private services, homeownership, and hurricane damage in the decision of evacuees to return. Second, we examine how the characteristics of the entire resident population changed over time in terms of demographic characteristics and family income.

Despite the attention paid to many aspects of Katrina’s aftermath, only a few studies have focused on the decision of individuals to return to the areas they evacuated. These studies have concentrated on single aspects that might influence the decision to return, such as an individual’s assessment of the risk of another hurricane striking an area (Baker et al. 2009), race and class (Elliott and Pais 2006), and the effect of the storm on an individual’s ties to an area (Paxson and Rouse 2008) or sense of place (Falk, Hunt, and Hunt 2006). By contrast, in this article, we take a more comprehensive approach.

Our analysis of returning is based on a relatively large and representative sample of evacuees from all geographic areas affected by the storm and on information indicating whether individuals actually returned to the areas from which they evacuated. Previous analyses have been based on evacuees’ intentions to return (e.g., Landry et al. 2007) or have been restricted to certain geographic areas or particular subpopulations (e.g., Paxson and Rouse 2008).

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

To motivate the empirical work that follows, we present a simple conceptual framework that includes a variety of factors that might influence the decision to return. This framework draws on standard human-capital investment models of geographic mobility (Borjas 1989; Greenwood 1975, 1985) in which individuals decide whether to migrate based on the utility they would receive from living in each area. We expand and modify the standard model to account for several circumstances specific to Katrina evacuees. First, evacuees deciding whether to return had initially migrated as part of a mass evacuation rather than for career or personal reasons. Second, the storm destroyed many aspects of evacuees’ lives that may have tied them to an area. Third, the financial cost that an evacuee would bear to return to an area could be substantial if a great deal of rebuilding and clean-up is necessary. Finally, evacuees experienced a great deal of uncertainty about the regulatory environment in storm-damaged areas and questions about what type of communities would be allowed to exist.

We model the decision to return as a comparison of the utility that individuals expect to receive living in one area versus another. Let o denote the location an individual evacuated (say, New Orleans), and let d denote the area to which an individual migrated (say, Houston). Then an individual will return if her expected discounted utility of living in location o is greater than the sum of her expected discounted utility of living in location d and the cost of returning:

| (1) |

where Uot represents the expected utility at time t of living in location o, Udt represents the expected utility at time t of living in location d, r is the discount rate, and c is the full cost of returning (measured in utility units). Time runs from the period in which the decision is made (t = 1) to the expected end of life (t = n).

The full cost of returning includes not only the direct expenses associated with moving back and the monetary costs of rebuilding or repairing a house (net of insurance payments and public assistance) but also the potentially huge time, monetary, and psychic costs associated with the relocation process (e.g., dealing with contractors and local public officials from a distance). The consideration of returning costs is important because even if evacuees would derive more utility living at the origin than the destination, the high cost of moving back may prevent them from doing so.

Factors that influence the expected utility of living in any given area include the amount of real income that an individual can expect to receive, an individual’s stock of location-specific capital associated with the area, the area’s amenities, locally produced public and private services, and an individual’s sense of place. In addition, the expected utility of living in an area directly affected by the storm can be influenced by uncertainty in the regulatory environment and questions about the degree of storm protection that the government will provide in the future. We briefly discuss each of these factors.1

Real Income

In light of research on geographic mobility within the United States (Borjas, Bronars, and Trejo 1992; Greenwood 1975; Sjaastad 1962), we anticipate regional differences in average wages and relative wages of workers with various skill levels to heavily influence evacuees’ decisions to return. However, because the evacuation was weather-related and widespread, the effect of such differences in wages is likely to be somewhat attenuated. Moreover, the focus on wages needs to be expanded to encompass other aspects of income, including transfer payments (e.g., Social Security benefits and welfare payments) and the likelihood that an individual with a certain skill level can obtain suitable employment in an area (see Groen and Polivka 2008a). Finally, to account for regional differences in prices, the utility comparison is assumed to be based on real income as opposed to nominal income. For those receiving fixed transfer payments, differences in prices are the primary component of differences in expected income between places.

Location-Specific Capital

“Location-specific capital,” a generic term for factors that tie someone to a particular place (DaVanzo and Morrison 1981; Paxson and Rouse 2008), includes concrete assets and other features specific to a place that are more valuable to an individual in one location than in another, such as job seniority, an established clientele, a license to practice a particular profession in a certain area, personal knowledge of an area, community ties, and social networks. Although location-specific capital usually does not depreciate over time, Hurricane Katrina potentially destroyed a great deal of location-specific capital (Paxson and Rouse 2008). Consequently, an individual’s decision to return depends on the individual’s stock of location-specific capital before the storm, the degree to which that stock was destroyed by the storm, and the extent to which location-specific capital can be restored. The restoration of some types of location-specific capital, such as social networks, is influenced by the previous and concurrent behavior of others, in a manner that can be self-reinforcing. Other types of location-specific capital will simply deteriorate the longer the individual is away from the pre-Katrina location. The location-specific capital associated with the areas to which individuals evacuated increases unambiguously with the time spent in those areas.

Amenities

Amenities are positive attributes associated with a specific area that cannot be influenced by an individual (Roback 1982; Sjaastad 1962). Amenities include physical attributes such as temperature, air quality, and recreational opportunities. Amenities may also include goods and services that are differentially available across areas, such as restaurants, professional sports teams, and museums. Disamenities are negative attributes, such as smog, crime, and a high probability of a hurricane striking.

Public and Private Services

The quality and amount of locally provided government services can influence where individuals decide to live, especially within specific regions or labor markets. These services include schools, libraries, parks, transportation infrastructure, hospitals, and public safety (including protection from flooding). Similarly, the provision and dependability of privately provided services can influence the decisions of evacuees to return. Services such as electricity, phone connections, and retail outlets are available in most areas, but in the wake of Katrina, these services were not immediately available in many of the affected areas.

Sense of Place

The term “sense of place” has been used by sociologists to explain why some blacks have moved back to the South (Falk 2004; Gieryn 2000; Hummon 1990). They define “place” as a geographical area in which one’s identity is “grounded” and further argue that people usually have a place-based identity of some kind. Much of the area affected by Hurricane Katrina, it could be argued, had a unique sense of place. To the extent that evacuees are tied to their pre-Katrina areas by a sense of place and cannot reconstitute this elsewhere, they will want to return (Chamlee-Wright and Storr 2009).

Government Regulations, Storm Protection, and Rebuilding Funds

Evacuees base their decision to return partly on the safety and type of communities they can anticipate living in after the storm. The expectations of evacuees, particularly homeowners from heavily damaged areas, depend on government regulation of rebuilding, accurate information about the risk of an area flooding, and the availability of government rebuilding funds. In the wake of Katrina, uncertainty on all of these dimensions was widespread. Comprehensive community-design plans were slow in being issued or were subject to frequent changes (Chamlee-Wright and Rothschild 2007). Updated flood-hazard maps were not issued for any areas until early 2008. And rebuilding-assistance programs for homeowners in Louisiana and Mississippi were plagued by complicated applications, policy changes, and low payout rates (Norcross and Skriba 2008).

DATA

Our empirical analysis is based primarily on data from the Current Population Survey (CPS), a nationally representative, monthly survey of approximately 60,000 occupied housing units. The CPS was modified in the wake of Hurricane Katrina to include questions that identify Katrina evacuees, the county (or parish) they evacuated, and if and when these individuals returned to their pre-Katrina residences (Cahoon et al. 2006; Groen and Polivka 2008b). (For ease of exposition, henceforth the term “counties” refers to parishes in Louisiana and counties in other states.) We use the responses to these questions, which were part of the CPS from October 2005 to October 2006, in combination with demographic and economic information collected in the CPS on a monthly basis. Information on evacuees’ counties of origin is used to merge the CPS data with data on damage from the storm, homeownership rates before the storm, and the availability of public and private services during the recovery.

The battery of CPS questions regarding Katrina opens with a question for the respondent for each household: “Is there anyone living or staying here who had to evacuate, even temporarily, where he or she was living in August because of Hurricane Katrina?” If the answer is yes, the respondent identifies who among those listed as being at the current address is an evacuee. The respondent is then asked about the pre-Katrina location of each evacuee using the question: “In August, prior to the hurricane warning, where (was NAME/were you) living?” Pre-Katrina locations are recorded in terms of state and county, parish, or city. The location of each household at the time of the interview can be obtained directly from the sample frame.

We define an evacuee as anyone who was identified as such in any of the months that the household was interviewed. Researchers interested in safety, disaster planning, and emergency responses typically define evacuees as those who leave before a natural disaster strikes (e.g., Gladwin and Peacock 1997; Haney, Elliott, and Fussell 2007; Perry, Lindell and Green 1981; Smith and McCarty 2009). In contrast, researchers interested in the recovery of an affected area, relocation decisions of individuals, and the effect of disasters on an area’s demographic composition define evacuees as those who leave either before or shortly after a natural disaster strikes (e.g., Elliott and Pais 2006; Girard and Peacock 1997; Landry et al. 2007). Given the large amount of destruction caused by Hurricane Katrina, the protracted nature of the disaster, and the focus of this article, we choose to define evacuees as those who left before or after the storm made landfall. To more carefully focus our analysis on those directly affected by Katrina, we also require that before the hurricane, evacuees lived in Louisiana, Mississippi, or Alabama in counties designated by the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) as eligible for both public and individual disaster assistance as a result of damages attributable to Hurricane Katrina (Groen and Polivka 2008b). Applying this definition to the CPS data, we estimate that approximately 1.5 million individuals aged 16 years and older evacuated because of Katrina.

EVACUATION RATES

To set the stage for the analysis of return migration among evacuees, we address a related issue: among pre-Katrina residents of areas affected by the storm, who evacuated? We estimate evacuation rates by using CPS data for October 2005–October 2006 on evacuees and on non-evacuees, who are defined as individuals living in these areas at the time of the CPS interview but who did not identify themselves as evacuees. The samples of evacuees and non-evacuees consist of individuals aged 19 years and older; persons aged 16 to 18 are included in the CPS but are excluded from our analysis because their migration behavior presumably depends on their parents’ decisions. The sample consists of 21,666 monthly observations on 6,692 individuals.

Over the entire region based on FEMA designations, which is a large area of 91 counties in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama, the estimated evacuation rate is 30%. Evacuation rates are much higher in areas near the Gulf Coast. In the set of 12 counties situated near the Gulf Coast within 100 miles of the storm path, an estimated 85% of pre-storm residents evacuated. By contrast, evacuation rates are considerably lower for areas farther away from the storm path: 32% in counties situated along the Gulf Coast within 100–200 miles of the storm path, and 8% among counties located further inland or near the Gulf Coast but more than 200 miles from the storm path.2

Given the geographical pattern of evacuation rates, we focus our analysis of return migration on evacuees who came from counties near the Gulf Coast within 100 miles of the storm path. (Henceforth, we refer to these counties as “affected areas” or “the entire affected area.”) We further distinguish among these counties by defining high-damage areas (four counties) and low-damage areas (eight counties).3 The estimated evacuation rate was 94% in high-damage areas (N = 1,517 monthly observations) and 80% in low-damage areas (N = 3,000 monthly observations). As shown in Table 1, evacuation rates do not vary greatly across demographic groups. In the entire affected area, the differences across subgroups for each characteristic are statistically significant but relatively small in magnitude.4 In high-damage areas, such variation tends to be even smaller.

Table 1.

Evacuation Rates by Personal and Family Characteristics

| Characteristic | Entire Affected Area |

High-Damage Areas |

Low-Damage Areas |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evacuation Rate | N | Evacuation Rate | N | Evacuation Rate | N | |

| Age | * | * | ||||

| 19 to 24 | 88.5 | 523 | 98.9 | 212 | 81.2 | 311 |

| 25 to 39 | 82.9 | 1,105 | 92.3 | 401 | 77.6 | 704 |

| 40 to 54 | 85.3 | 1,416 | 95.8 | 397 | 81.1 | 1,019 |

| 55 and older | 83.3 | 1,473 | 90.5 | 507 | 79.3 | 966 |

| Race/Ethnicity | * | |||||

| Whitea | 82.9 | 2,766 | 92.6 | 650 | 80.0 | 2,116 |

| Blacka | 87.2 | 1,359 | 94.2 | 796 | 75.9 | 563 |

| Hispanic | 83.6 | 221 | 94.3 | 33 | 81.8 | 188 |

| Othera | 89.0 | 171 | 100.0 | 38 | 86.0 | 133 |

| Gender | * | * | * | |||

| Female | 87.0 | 2,471 | 94.2 | 872 | 83.0 | 1,599 |

| Male | 81.8 | 2,046 | 93.1 | 645 | 76.1 | 1,401 |

| Education | * | * | ||||

| Less than high school | 85.5 | 746 | 94.3 | 345 | 77.3 | 401 |

| High school | 81.8 | 1,526 | 93.8 | 431 | 76.5 | 1,095 |

| Some college | 84.6 | 1,274 | 93.2 | 435 | 80.1 | 839 |

| College graduate | 88.1 | 971 | 93.6 | 306 | 85.6 | 665 |

| Marital Status | * | * | ||||

| Not married | 86.5 | 2,212 | 94.0 | 898 | 81.1 | 1,314 |

| Married | 82.5 | 2,305 | 93.3 | 619 | 78.5 | 1,686 |

| Children Under Age 18 | * | * | ||||

| Without children | 84.2 | 3,292 | 93.6 | 1,155 | 78.8 | 2,137 |

| With children | 85.4 | 1,225 | 94.1 | 362 | 81.8 | 863 |

| Family Income | * | * | * | |||

| Less than $15,000 | 90.8 | 680 | 95.3 | 347 | 85.4 | 333 |

| $15,000 to $74,999 | 86.0 | 1,938 | 92.8 | 706 | 81.8 | 1,232 |

| $75,000 or more | 83.8 | 860 | 90.4 | 227 | 81.6 | 633 |

| Not reported | 78.5 | 1,039 | 96.6 | 237 | 72.8 | 802 |

| Total | 84.5 | 4,517 | 93.7 | 1,517 | 79.7 | 3,000 |

Note: Sample sizes (N) are the number of person-month observations.

Source: Current Population Survey, October 2005–October 2006.

Non-Hispanic.

Differences in evacuation rates across subgroups for the specified characteristic are statistically significant (p < .05), based on a Pearson chi-square test.

DETERMINANTS OF RETURN MIGRATION

In this section, we examine the roles of demographic characteristics, public and private services, homeownership, and hurricane damage in the decision of evacuees to return to their pre-Katrina areas. The sample used in this analysis consists of CPS data from all 13 months (October 2005–October 2006) covered by the Katrina questions. This sample contains 3,764 monthly observations on 1,232 evacuees aged 19 years and older who resided before Katrina in one of the counties near the Gulf Coast within 100 miles of the storm path.5 We define returning for this analysis based on whether an evacuee was living in the same county at the time of the post-Katrina CPS interview as before Katrina. We estimate that, on average, over the entire 13-month period covered by the CPS data on evacuees, about 63% of evacuees returned to their pre-Katrina counties.

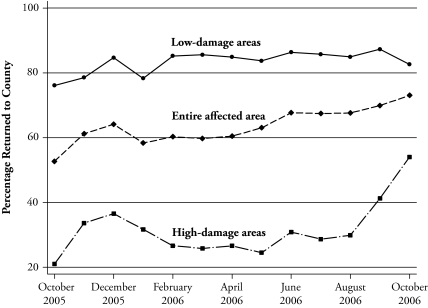

Tabulating the CPS data separately by month provides evidence on lengths of evacuation. In October 2005 (approximately two months after the storm), 53% of evacuees had returned to their pre-Katrina counties. As shown in Figure 1, the proportion of evacuees who had returned increased gradually from January 2006 (58%) to October 2006 (73%). These proportions suggest that the majority of those who returned (through October 2006) did so relatively quickly. Indeed, individuals who returned to their pre-storm addresses were away an average of 38 days. However, the timing of returning was quite different in high- and low-damage areas (Figure 1). The proportion of evacuees who had returned as of October 2005 was much lower in high-damage areas than low-damage areas, and the proportion returning to high-damage areas remained low until August 2006, when it began to increase.

Figure 1.

Percentage Returned to County by Month and Geographic Area

Source: Current Population Survey, October 2005–October 2006.

Descriptive Patterns

Personal and family characteristics. In contrast to evacuation rates, the probability of returning varies considerably by demographic group. Table 2 shows the percentage of evacuees in various demographic groups who returned to their pre-Katrina counties; the differences across subgroups are statistically significant for each characteristic for both the entire affected area and high-damage areas. The probability of returning increases with age, which is consistent with an individual’s location-specific capital and sense of place increasing with age. For evacuees who are retired, a high probability of returning also is consistent with these individuals not being influenced by relative wages and with the affected areas having a relatively low cost of living. Blacks were much less likely to return than individuals in other racial groups. Evacuees with lower levels of education and family income were less likely to return to high-damage areas than were other evacuees.

Table 2.

Percentage Returned to County by Personal and Family Characteristics

| Characteristic | Entire Affected Area |

High-Damage Areas |

Low-Damage Areas |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage Returned | N | Percentage Returned | N | Percentage Returned | N | |

| Age | * | * | * | |||

| 19 to 24 | 49.8 | 458 | 16.9 | 209 | 77.6 | 249 |

| 25 to 39 | 52.2 | 915 | 20.5 | 370 | 73.7 | 545 |

| 40 to 54 | 69.3 | 1,192 | 33.3 | 379 | 86.5 | 813 |

| 55 and older | 73.9 | 1,199 | 47.0 | 460 | 91.3 | 739 |

| Race/Ethnicity | * | * | * | |||

| Whitea | 76.2 | 2,256 | 46.1 | 601 | 86.5 | 1,655 |

| Blacka | 38.3 | 1,181 | 22.4 | 748 | 70.3 | 433 |

| Hispanic | 73.8 | 176 | 24.3 | 31 | 83.7 | 145 |

| Othera | 68.4 | 151 | 2.5 | 38 | 88.8 | 113 |

| Gender | * | * | * | |||

| Female | 61.7 | 2,134 | 28.7 | 825 | 82.5 | 1,309 |

| Male | 65.6 | 1,630 | 34.0 | 593 | 85.0 | 1,037 |

| Education | * | * | * | |||

| Less than high school | 53.3 | 628 | 23.6 | 324 | 87.3 | 304 |

| High school | 62.8 | 1,219 | 20.9 | 400 | 85.1 | 819 |

| Some college | 65.6 | 1,065 | 35.7 | 406 | 83.7 | 659 |

| College graduate | 69.5 | 852 | 49.2 | 288 | 79.4 | 564 |

| Marital Status | * | * | ||||

| Not married | 57.9 | 1,891 | 27.6 | 840 | 83.3 | 1,051 |

| Married | 69.5 | 1,873 | 36.8 | 578 | 83.9 | 1,295 |

| Children Under Age 18 | * | * | * | |||

| Without children | 66.1 | 2,718 | 36.0 | 1,077 | 86.7 | 1,641 |

| With children | 56.9 | 1,046 | 15.6 | 341 | 76.9 | 705 |

| Family Income | * | * | * | |||

| Less than $15,000 | 38.3 | 607 | 20.3 | 329 | 61.9 | 278 |

| $15,000 to $74,999 | 62.4 | 1,649 | 31.2 | 654 | 83.9 | 995 |

| $75,000 or more | 74.2 | 714 | 52.3 | 206 | 82.2 | 508 |

| Not reported | 75.3 | 794 | 30.3 | 229 | 94.1 | 565 |

| Total | 63.5 | 3,764 | 31.1 | 1,418 | 83.6 | 2,346 |

Note: Sample sizes (N) are the number of person-month observations.

Source: Current Population Survey, October 2005–October 2006.

Non-Hispanic.

Differences in return rates across subgroups for the specified characteristic are statistically significant (p < .05), based on a Pearson chi-square test.

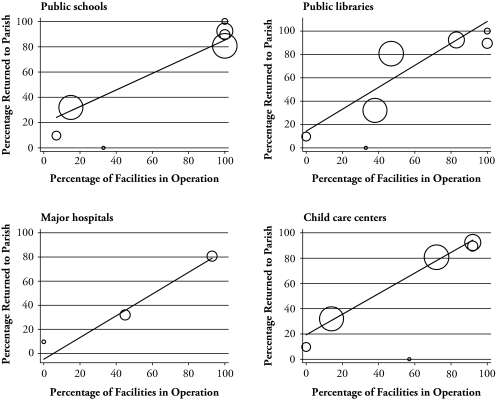

Public and private services. For evacuees who lived in the New Orleans metropolitan area before the storm, we link the CPS data to measures of services available during the recovery (Liu, Fellowes, and Mabanta 2006). We use measures for public schools, public libraries, major hospitals, and child care centers as of February 2006. As shown in Figure 2, for each type of facility, there is a positive relationship between the percentage of evacuees who returned and the proportion of facilities in operation. This pattern suggests that public and private services are important factors in the decision to return. However, other interpretations are plausible because causation may run the other way: residents may choose to return for other reasons and create demand for facilities to open.

Figure 2.

Public and Private Services and Returning

Notes: The area of each symbol is proportional to the number of evacuees who came from the parish. Each data point refers to one of the seven parishes in the New Orleans MSA (Jefferson, Orleans, Plaquemines, St. Bernard, St. Charles, St. John the Baptist, and St. Tammany). The regression line is estimated by weighted least squares with the number of evacuees in each parish as weights. The slopes of the regression lines are: 0.659 (SE = 0.070) for schools; 0.940 (SE = 0.348) for libraries; 0.900 (SE = 0.159) for hospitals; and 0.816 (SE = 0.090) for child care.

Source: Returning measure is based on Current Population Survey, October 2005–October 2006. Services data are from Liu et al. (2006: Tables 28, 32, 33, and 34). Timing of services data: schools, February 2, 2006; libraries, February 2006; hospitals, February 14, 2006; child care, February 2006.

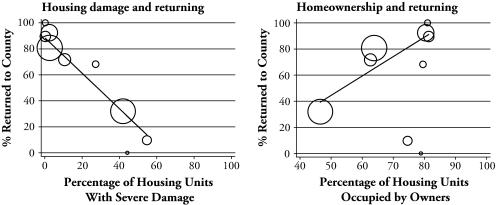

Housing damage. Data on the physical damage to local areas are desirable because they speak directly to the housing and employment situations of evacuees and because damage occurred before evacuees began considering whether to return. We link the CPS data to county-level measures from FEMA on damages to real property and personal property not covered by insurance. These estimates of damage were based on direct inspection of housing units to determine eligibility for FEMA housing assistance. Analysts at the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (2006) categorized the inspection results into three categories: minor damage (less than $5,200), major damage (between $5,200 and $29,999), and severe damage ($30,000 or higher).

We divided the number of housing units in each damage category by the total number of occupied housing units in a county before Katrina (according to the 2000 census) to compute the percentage of housing units in the county that are in each damage category. The scatter plot in Figure 3 (left panel) indicates a negative relationship between the percentage of evacuees who returned to a county and the percentage of housing units in the county with severe damage. The magnitude of this relationship is similar regardless of how we define damage, but the fit of the regression line is best when damage is measured as the percentage with severe damage (Groen and Polivka 2009).

Figure 3.

Housing Damage, Homeownership, and Returning

Notes: The area of each symbol is proportional to the number of evacuees who came from the county. The regression lines are estimated by weighted least squares with the number of evacuees in each county as weights. The slope of the regression line for housing damage and returning is −1.366 (SE = 0.102). The slope of the regression line for homeownership and returning is 1.485 (SE = 0.565).

Source: Returning measure is based on Current Population Survey, October 2005–October 2006. Damage data are from U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (2006). Homeownership rates are based on data from the 2000 census (Summary File 1).

Homeownership. People who own their homes often have stronger ties to their communities than people who rent their homes; thus, homeownership is considered a signal of location-specific capital. Therefore, we expect that evacuees who owned their homes before Katrina would be more likely to return than evacuees who rented their homes, all else equal. Because CPS data on pre-Katrina homeownership are not available for all evacuees, we use data from the 2000 census to construct the rate of homeownership in each county from which evacuees originated.6 Figure 3 (right panel) shows that a higher rate of homeownership in a county is associated with a larger percentage of evacuees returning to the county.

Multivariate Analysis

The preceding analysis identifies several factors that might explain evacuees’ decision to return to their pre-Katrina areas. To account for relationships among these characteristics, we estimate logit models in which the dependent variable is an indicator for whether an evacuee had returned to his or her pre-Katrina county by the time of the CPS interview. All of these models include month-year time indicator variables to control for changes over time in the probability of returning.

We first consider a specification that includes only personal and family characteristics as explanatory variables, in addition to the time controls. Column 1 of Table 3 reports estimated marginal effects of these characteristics on the probability of returning. Similar to the descriptive statistics, the regression estimates highlight the roles of age and race as determinants of returning. Older evacuees were more likely to return than younger evacuees, and a joint test that the marginal effects of the age variables are zero can be strongly rejected (χ2 = 22.85; p value = .00). Blacks were much less likely to return than whites; the difference is statistically significant, and the point estimate reflects a difference of 31 percentage points.

Table 3.

Determinants of Returning to County

| Variable | Entire Affected Area |

High-Damage Areas |

Low-Damage Areas |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Age 25 to 39 | 0.026 (0.048) | 0.031* (0.014) | 0.077 (0.081) | 0.069* (0.019) | 0.014 (0.045) | 0.029 (0.018) |

| Age 40 to 54 | 0.144* (0.047) | 0.135* (0.023) | 0.200* (0.078) | 0.205* (0.029) | 0.105* (0.044) | 0.109* (0.023) |

| Age 55 and Older | 0.184* (0.048) | 0.173* (0.036) | 0.278* (0.077) | 0.248* (0.022) | 0.128* (0.041) | 0.133* (0.036) |

| Blacka | −0.311* (0.049) | −0.127* (0.059) | −0.101 (0.063) | −0.159* (0.006) | −0.119* (0.054) | −0.101 (0.067) |

| Hispanic | 0.002 (0.078) | −0.054 (0.059) | −0.087 (0.112) | −0.121* (0.040) | −0.029 (0.075) | −0.036 (0.058) |

| Othera | −0.098 (0.111) | −0.099 (0.071) | −0.288* (0.044) | −0.297* (0.002) | −0.012 (0.078) | −0.028 (0.088) |

| Male | 0.024 (0.020) | 0.029* (0.014) | 0.054 (0.032) | 0.047* (0.003) | 0.004 (0.017) | 0.008 (0.020) |

| Less Than High School | −0.023 (0.046) | 0.029* (0.010) | 0.040 (0.068) | 0.045* (0.003) | 0.053 (0.039) | 0.049* (0.023) |

| Some College | 0.020 (0.037) | 0.029 (0.018) | 0.113 (0.059) | 0.073* (0.016) | −0.005 (0.035) | −0.007 (0.010) |

| College Graduate | −0.035 (0.046) | −0.006 (0.067) | 0.156* (0.073) | 0.095* (0.029) | −0.097* (0.044) | −0.102* (0.030) |

| Married | −0.018 (0.037) | −0.049 (0.028) | −0.030 (0.059) | −0.062 (0.050) | −0.056 (0.036) | −0.053* (0.023) |

| With Children | −0.019 (0.041) | −0.059 (0.034) | −0.153* (0.060) | −0.129* (0.047) | −0.010 (0.039) | −0.019 (0.025) |

| Less Than $15,000 | −0.119* (0.058) | −0.112* (0.054) | −0.028 (0.081) | −0.049* (0.021) | −0.206* (0.073) | −0.185* (0.031) |

| $75,000 or More | 0.042 (0.057) | 0.024 (0.044) | 0.132 (0.101) | 0.132* (0.006) | 0.010 (0.045) | 0.001 (0.026) |

| Severe Damage (%) | −0.0089* (0.0009) | |||||

| Homeownership (%) | −0.0015 (0.0021) | −0.0087* (0.0007) | 0.0091* (0.0023) | |||

| Persistence in County (%) | −0.0069 (0.0062) | −0.0351* (0.0033) | 0.0027 (0.0016) | |||

| Pseudo-R2 | .15 | .32 | .16 | .21 | .14 | .18 |

| N | 3,764 | 3,764 | 1,418 | 1,418 | 2,346 | 2,346 |

| Percentage Returned | 63.5 | 63.5 | 31.1 | 31.1 | 83.6 | 83.6 |

Notes: The dependent variable is an indicator for returning to the pre-Katrina county. The numbers reported in the table are average marginal effects from logit models. Standard errors, in parentheses, are corrected for correlation in the error term at the household level (columns 1, 3, and 5) or at the county level (columns 2, 4, and 6). Regressions also include month-year indicators and an indicator for observations without data on family income, and are estimated using CPS sampling weights. The omitted categories are: age 19 to 24; white; female; high school; not married; without children; and $15,000 to $74,999. The high-damage areas are Orleans, Plaquemines, and St. Bernard parishes in Louisiana and Hancock County in Mississippi. The low-damage areas are Jefferson, Lafourche, St. Charles, St. John the Baptist, and St. Tammany parishes in Louisiana and Harrison, Pearl River, and Stone counties in Mississippi.

Source: Current Population Survey, October 2005–October 2006.

Non-Hispanic.

p < .05

The second specification includes housing damage, homeownership, and sense of place, along with the time controls and the personal and family characteristics. The measure of sense of place is the percentage of residents (aged 5 and older) in 2000 of the evacuee’s county of origin that lived in the county in 1995, based on data from the 2000 census. We anticipate that individuals who have lived in an area less than 5 years would have less sense of place because they had less time to adopt the lifestyle of an area. Adding housing damage, homeownership, and the measure of sense of place to the regression does not affect age differences but dramatically reduces racial differences in returning (Table 3, column 2): the estimated difference in returning between black and white evacuees falls from 31 percentage points to 13 percentage points (but remains statistically significant). This change is driven almost entirely by the inclusion of the damage variable, not the homeownership or sense of place variables. The change in the estimated effect of race suggests that blacks were more likely to live in areas that suffered severe damage because of the storm; and to a large extent, it was differences in the amount of damage—rather than race, per se—that influenced return migration. Indeed, the correlation at the county level between the percentage of evacuees who are black and the percentage of housing units with severe damage is .80.

Damage exerts a strong influence on returning even when personal and family characteristics are held constant: a 10-percentage-point increase in the percentage of housing units in a county with severe damage is associated with a statistically significant decrease of 8.9 percentage points in the probability of an evacuee returning. The marginal effects of homeownership and sense of place are negative (opposite of the expected direction) but not statistically significant.

Because the level of location-specific capital (associated with evacuees’ home areas) after the storm depends on both the pre-storm stock of location-specific capital and the degree to which that stock was destroyed in the storm, the pre-storm stock may not influence the return behavior of evacuees who experienced high levels of damage (Paxson and Rouse 2008). Among these evacuees, homeowners may be more affected than renters by uncertainty in the regulatory environment surrounding rebuilding and delays in receiving financing to pay for repairs. These factors would further mute the effect of the pre-storm stock of location-specific capital on returning and discourage homeowners from returning.

To examine these hypotheses, we split the sample of evacuees into those from high-damage areas and those from low-damage areas. High-damage areas are the four counties with at least 20% of housing units classified as severely damaged; low-damage areas are the remainder of the affected counties. On average, over the 13 months of our sample, 84% of evacuees from low-damage areas returned, but only 31% of evacuees from high-damage areas returned. Taking homeownership as a signal of location-specific capital, the estimated marginal effects shown in Table 3 are consistent with the hypothesis that the destruction of location-specific capital reduces the probability of returning: homeownership does not encourage returning to high-damage areas but does encourage returning to low-damage areas. In fact, in high-damage areas, homeownership is negatively associated with returning.

The effects of several demographic characteristics on returning are different among evacuees from high-damage areas than among those from low-damage areas. Among evacuees from high-damage areas, evacuees with children are less likely to return than evacuees without children; among evacuees from low-damage areas, by contrast, there is no difference between these groups in the probability of returning. The impact of children on returning to high-damage areas might reflect the fact that public schools in many of these areas were closed for many months after the storm (Liu and Plyer 2008).

Differences in returning by education group among evacuees from high-damage areas are of an opposite pattern than the differences among those from low-damage areas. Compared with high school graduates, college graduates were more likely to return to high-damage areas but less likely to return to low-damage areas.7 These differences likely reflect a combination of factors. The pattern among evacuees from low-damage areas is consistent with college graduates having better access to job opportunities in other areas through geographically disperse networks based on their education and occupation (Greenwood 1975). Although this factor is also relevant among evacuees from high-damage areas, other factors may work in the opposite direction and tip the balance to produce the observed pattern. For instance, there is some evidence that more-educated evacuees were more likely to evacuate to nearby locations (Frey, Singer, and Park 2007), which reduced the costs of returning. In addition, more-educated evacuees might have had greater wealth and/or homeowners insurance before the storm.

Older evacuees were more likely than younger evacuees to return to both high-damage and low-damage areas, but these age differences are greater in high-damage areas. (A joint test that the marginal effects of the age variables are zero can be strongly rejected for both high-damage [χ2 = 7,723.73; p value = .00] and low-damage [χ2 = 78.16; p value = .00] areas.) As discussed earlier, our conceptual framework suggests several reasons why older evacuees were more likely to return.

Differences by Race and Education in Returning to New Orleans

Our analysis of CPS data indicates differences by race and education in returning to high-damage areas. In this section, we address whether these differences reflect differences across groups in the amount of storm damage. It is difficult to address this issue using CPS data because 80% of the evacuees in the high-damage sample came from Orleans Parish (i.e., the city of New Orleans) and the Katrina questions on the geographic origins of evacuees did not request information below the parish level.

Therefore, we turn to data from the Displaced New Orleans Residents Pilot Study (DNORPS), which is a survey of former New Orleans residents conducted for the RAND Corporation in September 2006–November 2006. DNORPS is based on a stratified, area-based probability sample of pre-Katrina dwellings in the city of New Orleans (Sastry 2009). Individuals who resided at one of the sample dwellings before Katrina were interviewed, regardless of where they were currently living. The DNORPS questionnaire requested information on individual and family background characteristics (similar to those used in our analysis of the CPS data), whether each individual was currently living in New Orleans, whether the sampled dwelling was owned or rented, and the extent of damage to the dwelling from Katrina and the subsequent flooding.8

Among the 147 households that were interviewed, the DNORPS recorded information on 386 individuals. We analyze data from a sample of 287 individuals aged 19 years and older, following the age restriction of our CPS sample. Among the individuals in the DNORPS sample, 54% had returned to New Orleans by the time of the interview. This rate is higher than the rate of returning to New Orleans over the entire 13 months of our CPS sample (32%), but it is similar to the figure when the CPS sample of evacuees from Orleans Parish is limited to September 2006–October 2006 (51%), which roughly corresponds to the period of the DNORPS interviews.

The DNORPS sample accords well with the CPS sample of evacuees from Orleans Parish, both in terms of the distribution of background characteristics and in a baseline regression in which returning is a function of time controls (for the CPS only) and background characteristics (Table 4, columns 1 and 2). Notably, the differences in returning by age, race, and education that are present in our CPS data are also present in the DNORPS sample. Housing damage from Katrina is categorized by the DNORPS as destroyed, uninhabitable, damaged but habitable, or undamaged. When indicator variables for these damage categories (undamaged being the omitted category) are added to the regression, the estimated differences by age are essentially unchanged (columns 3 and 4). By contrast, racial differences in returning are reduced dramatically, from a statistically significant black-white difference of 23 percentage points to a statistically insignificant difference of 4 percentage points.

Table 4.

Determinants of Returning to the City of New Orleans

| Variable | CPS (1) | DNORPS |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (2) | (3) | (4) | ||

| Age 25 to 39 | 0.069 (0.087) | 0.166 (0.122) | 0.164 (0.122) | 0.164 (0.119) |

| Age 40 to 54 | 0.196* (0.089) | 0.256* (0.107) | 0.250* (0.108) | 0.251* (0.101) |

| Age 55 and Older | 0.290* (0.086) | 0.300* (0.104) | 0.296* (0.104) | 0.266* (0.098) |

| Blacka | −0.213* (0.078) | −0.228* (0.091) | −0.225* (0.091) | −0.037 (0.092) |

| Hispanic/Othera | −0.250* (0.068) | −0.011 (0.181) | −0.005 (0.184) | 0.062 (0.162) |

| Male | 0.062 (0.039) | −0.102 (0.055) | −0.104 (0.055) | −0.077 (0.051) |

| Less Than High School | 0.032 (0.080) | 0.020 (0.106) | 0.022 (0.107) | 0.027 (0.097) |

| Some College | 0.080 (0.067) | −0.068 (0.102) | −0.071 (0.101) | −0.066 (0.092) |

| College Graduate | 0.141 (0.086) | 0.092 (0.098) | 0.090 (0.098) | 0.087 (0.092) |

| Married | −0.088 (0.063) | −0.090 (0.088) | −0.093 (0.088) | −0.012 (0.085) |

| With Children | −0.093 (0.074) | −0.042 (0.113) | −0.040 (0.113) | −0.086 (0.094) |

| Homeowner | 0.025 (0.091) | 0.035 (0.088) | ||

| Destroyed | −0.610* (0.052) | |||

| Uninhabitable | −0.466* (0.074) | |||

| Damaged but Habitable | −0.260* (0.080) | |||

| Pseudo-R2 | .17 | .11 | .11 | .23 |

| N | 1,136 | 287 | 287 | 287 |

| Percentage Returned | 32.0 | 53.9 | 53.9 | 53.9 |

Notes: The dependent variable is an indicator for returning to the city of New Orleans (i.e., Orleans Parish). The numbers reported in the table are average marginal effects from logit models. Standard errors, in parentheses, are corrected for correlation in the error term at the household level. The regressions are estimated using sampling weights (which for DNORPS account for the stratification by flood depth). The CPS regression also includes month-year indicators. The omitted categories are: age 19 to 24; white; female; high school; not married; without children; renter; and undamaged.

Source: Current Population Survey (CPS; October 2005–October 2006) and Displaced New Orleans Residents Pilot Study (DNORPS).

Non-Hispanic.

p < .05

This finding reflects two things. First, on average, blacks experienced greater housing damage than whites. According to our DNORPS sample, 81% of blacks reported that their homes were destroyed or rendered uninhabitable by Katrina, compared with 37% of whites.9 Second, the degree of housing damage exerts a powerful influence on returning, as we found in our analysis of CPS data. The pattern of marginal effects is jointly significant and monotonic with respect to damage, with those whose homes were destroyed being 61 percentage points less likely to return than those whose homes were undamaged, all else equal. Consequently, the finding of the lack of a racial difference in returning after damage is controlled for indicates that damage, not race per se, drives racial differences in returning. This finding from the DNORPS, based on within-county variation in damage, is consistent with the pattern of our findings in the CPS analysis, which involves cross-county variation in damage.

Unlike the racial differences, differences by education in returning to New Orleans are not affected by adding the damage variable to the DNORPS regressions. With or without damage in these regressions, college graduates were approximately 9 percentage points more likely to return than high school graduates, although the difference is not statistically significant. The lack of a change in education differences in returning when damage is added reflects that there is essentially no relationship within race between education and housing damage. This pattern of damages may arise if New Orleans neighborhoods, which were segregated on the basis of race (Brookings Institution 2005), were integrated by education within race.

CHANGES IN AFFECTED AREAS

In this section, we shift from analyzing evacuees’ decisions to return to understanding how the aggregate effect of those decisions is reflected in changes over time in the composition of affected areas. For these changes, the primary forces are the migration flows associated with Katrina evacuees who returned or did not return to their pre-Katrina counties during the first year after Katrina (through October 2006). In principle, there could also be a role for migration flows associated with non-evacuees moving into or out of the Katrina-affected area after the hurricane. However, the number of such migrating non-evacuees appears to be relatively small because we have defined the affected area such that the evacuation rate is quite high. Thus, changes in the demographic composition of the Katrina-affected areas depend primarily on the differences between returning and non-returning evacuees.

Table 5 reports the demographic composition of returnees and non-returnees, both for the entire affected area and for high-damage areas. Consistent with the findings on the determinants of returning, the demographic composition of evacuees who returned differs significantly from that of evacuees who did not return. Among evacuees from the entire affected area, 70% of returnees are white compared with only 38% of non-returnees. By contrast, only 20% of returnees are black, compared with 55% of non-returnees. Returnees as a group are older than non-returnees; for instance, 34% of returnees are aged 55 and older compared with only 21% of non-returnees. Furthermore, non-returnees had lower family incomes than returnees; for instance, 32% of non-returnees had incomes less than $15,000, compared with only 13% of returnees. Table 5 also indicates differences in the demographic distribution of returnees and non-returnees by education, marital status, and the presence of children.

Table 5.

Personal and Family Characteristics of Returnees and Non-returnees (distributions in percentages)

| Characteristic | Entire Affected Area |

High-Damage Areas |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Returnees | Non-returnees | χ2 | Returnees | Non-returnees | χ2 | |

| Age | * | * | ||||

| 19 to 24 | 11.4 | 19.9 | 9.4 | 20.9 | ||

| 25 to 39 | 20.9 | 33.3 | 17.6 | 30.9 | ||

| 40 to 54 | 33.9 | 26.1 | 27.9 | 25.3 | ||

| 55 and older | 33.9 | 20.8 | 45.0 | 22.9 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | * | * | ||||

| Whitea | 70.2 | 38.1 | 57.6 | 30.5 | ||

| Blacka | 19.5 | 54.7 | 40.5 | 63.5 | ||

| Hispanic | 5.9 | 3.6 | 1.7 | 2.4 | ||

| Othera | 4.5 | 3.6 | 0.2 | 3.6 | ||

| Gender | * | * | ||||

| Female | 53.1 | 57.2 | 50.7 | 56.8 | ||

| Male | 46.9 | 42.8 | 49.3 | 43.2 | ||

| Education | * | * | ||||

| Less than high school | 14.2 | 21.6 | 17.8 | 26.1 | ||

| High school | 31.8 | 32.7 | 19.5 | 33.4 | ||

| Some college | 29.7 | 27.1 | 32.5 | 26.5 | ||

| College graduate | 24.4 | 18.6 | 30.1 | 14.1 | ||

| Marital Status | * | * | ||||

| Not married | 47.1 | 59.7 | 54.7 | 64.8 | ||

| Married | 52.9 | 40.3 | 45.3 | 35.2 | ||

| Children Under Age 18 | * | * | ||||

| Without children | 74.6 | 66.5 | 87.9 | 70.5 | ||

| With children | 25.4 | 33.5 | 12.1 | 29.5 | ||

| Family Income | * | * | ||||

| Less than $15,000 | 13.2 | 32.1 | 18.7 | 33.3 | ||

| $15,000 to $74,999 | 58.0 | 52.8 | 55.6 | 56.0 | ||

| $75,000 or more | 28.8 | 15.2 | 25.7 | 10.7 | ||

| Number of Individualsb | 575.3 | 330.9 | 108.2 | 239.5 | ||

Note: Distributions of family income are based on those who reported family income.

Source: Current Population Survey, October 2005–October 2006.

Non-Hispanic.

In thousands.

The distribution of returnees is significantly different (p < .05) from the distribution of non-returnees, for the specified characteristic, based on a Pearson chi-square test.

Differences between the composition of returning and non-returning evacuees suggest that Katrina may have altered the composition of the geographic areas in the storm path. Table 6 contains distributions of the demographic characteristics and family income of all residents (not just evacuees) of the entire affected area and of the high-damage areas, both before and after the storm. Table 7 contains these estimates for the New Orleans metropolitan statistical area (MSA) and for the Mississippi Gulf Coast. All the estimates are based on monthly CPS data and cover one time period before the storm (January 2004–July 2005) and two time periods after the storm (October 2005–October 2006 and November 2006–November 2007).

Table 6.

Composition of Affected Areas Before and After Katrina: Entire Affected Area and High-Damage Areas (distributions in percentages)

| Characteristic | Entire Affected Area |

High-Damage Areas |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004–2005 | 2005–2006 | 2006–2007 | χ2 | 2004–2005 | 2005–2006 | 2006–2007 | χ2 | |

| Age | * | * | ||||||

| 19 to 24 | 12.2 | 12.1 | 12.3 | 11.7 | 8.0 | 13.9 | ||

| 25 to 39 | 26.1 | 22.2 | 24.2 | 27.5 | 19.5 | 27.2 | ||

| 40 to 54 | 30.0 | 32.7 | 30.8 | 28.3 | 27.3 | 25.2 | ||

| 55 and older | 31.7 | 33.0 | 32.8 | 32.4 | 45.2 | 33.7 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | * | * | ||||||

| Whitea | 66.1 | 70.1 | 68.5 | 45.0 | 57.0 | 51.4 | ||

| Blacka | 28.8 | 20.4 | 23.2 | 52.0 | 41.2 | 45.1 | ||

| Hispanic | 3.2 | 5.4 | 6.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | ||

| Othera | 1.8 | 4.1 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 1.8 | ||

| Gender | * | * | ||||||

| Female | 55.0 | 51.6 | 52.7 | 57.0 | 50.9 | 53.5 | ||

| Male | 45.0 | 48.4 | 47.3 | 43.0 | 49.1 | 46.5 | ||

| Education | * | * | ||||||

| Less than high school | 15.3 | 14.6 | 11.1 | 15.3 | 18.2 | 16.7 | ||

| High school | 33.1 | 33.8 | 32.1 | 32.2 | 20.2 | 22.5 | ||

| Some college | 27.8 | 29.3 | 31.2 | 26.7 | 32.9 | 28.3 | ||

| College graduate | 23.9 | 22.4 | 25.7 | 25.8 | 28.8 | 32.6 | ||

| Marital Status | * | * | ||||||

| Not married | 49.2 | 46.9 | 47.8 | 58.0 | 53.8 | 55.9 | ||

| Married | 50.8 | 53.2 | 52.2 | 42.0 | 46.2 | 44.1 | ||

| Children Under Age 18 | ||||||||

| Without children | 73.8 | 74.2 | 72.8 | 77.5 | 83.6 | 75.6 | ||

| With children | 26.2 | 25.8 | 27.2 | 22.5 | 16.4 | 24.4 | ||

| Family Income | * | * | ||||||

| Less than $15,000 | 18.8 | 13.0 | 12.8 | 24.3 | 17.9 | 21.7 | ||

| $15,000 to $74,999 | 60.5 | 57.2 | 57.1 | 61.9 | 56.1 | 57.5 | ||

| $75,000 or more | 20.8 | 29.8 | 30.1 | 13.8 | 26.0 | 20.8 | ||

| Housing Occupancy | * | * | ||||||

| Owner | 74.2 | 77.4 | 74.0 | 61.6 | 71.0 | 61.4 | ||

| Renter | 24.6 | 20.8 | 23.5 | 37.3 | 26.4 | 33.4 | ||

| Occupied without payment | 1.2 | 1.8 | 2.6 | 1.1 | 2.7 | 5.2 | ||

| Number of Individualsb | 1,128.9 | 805.6 | 878.2 | 383.1 | 138.3 | 196.3 | ||

Notes: 2004–2005 is January 2004–July 2005. 2005–2006 is October 2005–October 2006. 2006–2007 is November 2006–November 2007. Distributions of family income are based on those who reported family income.

Source: Current Population Survey, January 2004–November 2007.

Non-Hispanic.

In thousands.

The distribution across subgroups for the specified characteristic is significantly different (p < .05) over time, based on a Pearson chi-square test.

Table 7.

Composition of Affected Areas Before and After Katrina: New Orleans MSA and Mississippi Gulf Coast (distributions in percentages)

| Characteristic | New Orleans MSA |

Mississippi Gulf Coast |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004–2005 | 2005–2006 | 2006–2007 | χ2 | 2004–2005 | 2005–2006 | 2006–2007 | χ2 | |

| Age | * | |||||||

| 19 to 24 | 13.0 | 12.9 | 13.1 | 9.7 | 8.8 | 10.1 | ||

| 25 to 39 | 25.7 | 21.9 | 24.0 | 27.8 | 26.3 | 26.9 | ||

| 40 to 54 | 30.6 | 33.2 | 30.6 | 28.4 | 30.0 | 29.2 | ||

| 55 and older | 30.7 | 32.1 | 32.4 | 34.1 | 35.0 | 33.8 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | * | * | ||||||

| Whitea | 63.5 | 69.4 | 67.1 | 73.5 | 69.7 | 72.7 | ||

| Blacka | 31.7 | 20.9 | 24.7 | 20.7 | 25.1 | 21.3 | ||

| Hispanic | 3.2 | 4.9 | 6.6 | 2.7 | 4.6 | 4.8 | ||

| Othera | 1.7 | 4.7 | 1.6 | 3.1 | 0.6 | 1.2 | ||

| Gender | * | |||||||

| Female | 55.1 | 53.0 | 53.5 | 55.5 | 49.3 | 50.2 | ||

| Male | 44.9 | 47.0 | 46.6 | 44.5 | 50.7 | 49.8 | ||

| Education | * | |||||||

| Less than high school | 15.7 | 14.0 | 10.4 | 14.4 | 14.9 | 14.8 | ||

| High school | 32.9 | 32.7 | 31.5 | 33.7 | 37.3 | 34.2 | ||

| Some college | 26.9 | 29.5 | 31.5 | 32.5 | 30.9 | 31.9 | ||

| College graduate | 24.6 | 23.8 | 26.6 | 19.4 | 17.0 | 19.1 | ||

| Marital Status | * | |||||||

| Not married | 50.2 | 48.8 | 48.6 | 43.1 | 38.6 | 41.7 | ||

| Married | 49.8 | 51.2 | 51.4 | 56.9 | 61.4 | 58.3 | ||

| Children Under Age 18 | ||||||||

| Without children | 74.2 | 73.6 | 72.6 | 69.3 | 69.3 | 71.3 | ||

| With children | 25.8 | 26.4 | 27.4 | 30.7 | 30.7 | 28.7 | ||

| Family Income | * | * | ||||||

| Less than $15,000 | 19.3 | 12.9 | 12.6 | 20.0 | 14.7 | 10.8 | ||

| $15,000 to $74,999 | 59.9 | 57.7 | 56.1 | 60.1 | 56.9 | 60.0 | ||

| $75,000 or more | 20.8 | 29.4 | 31.3 | 19.8 | 28.4 | 29.2 | ||

| Housing Occupancy | * | * | ||||||

| Owner | 74.4 | 77.1 | 73.5 | 74.8 | 82.0 | 79.2 | ||

| Renter | 24.7 | 21.6 | 24.4 | 21.6 | 13.7 | 16.7 | ||

| Occupied without payment | 0.9 | 1.4 | 2.1 | 3.6 | 4.4 | 4.1 | ||

| Number of Individualsb | 958.4 | 677.6 | 757.8 | 293.8 | 263.1 | 261.8 | ||

Notes: 2004–2005 is January 2004–July 2005. 2005–2006 is October 2005–October 2006. 2006–2007 is November 2006–November 2007. Distributions of family income are based on those who reported family income. New Orleans MSA: Jefferson, Orleans, Plaquemines, St. Bernard, St. Charles, St. John the Baptist, and St. Tammany parishes. Mississippi Gulf Coast: Hancock, Harrison, and Jackson counties.

Source: Current Population Survey, January 2004–November 2007.

Non-Hispanic.

In thousands.

The distribution across subgroups for the specified characteristic is significantly different (p < .05) over time, based on a Pearson chi-square test.

In general, the changes over time are larger for the high-damage areas than for the entire affected area because the magnitude of the population shifts induced by Katrina was larger in the high-damage areas. The evacuation rate was higher in high-damage areas (see Table 1), and thus high-damage areas were more affected by patterns of return migration.

Katrina is associated with substantial shifts in racial composition. These shifts are statistically significant and primarily represent a decrease in the percentage of residents who are black and a corresponding increase in the percentage of residents who are white, which follows from the lower rate of returning among black evacuees. Specifically, in high-damage areas, the percentage of residents who are black decreased from 52% before the storm to 41% in the year after the storm before rebounding to 45% the following year. This pattern of change in racial composition is also present in the New Orleans MSA, but the Mississippi Gulf Coast exhibits the reverse pattern, with the percentage black increasing after Katrina before falling back to near its pre-Katrina level.

The rebounding of the percentage black in high-damage areas and the New Orleans MSA suggests that among evacuees who returned during the first two years after Katrina, blacks returned more slowly than whites. Consistent with this notion, the black-white difference in the probability of returning is smaller in the last three months of the period covered by the Katrina questions (20 percentage points) than in the first 10 months of this period (34 percentage points), according to baseline regressions (analogous to Table 3, column 1) estimated separately for each of these time periods. The reduction in the black-white difference appears to be related to the reopening of public schools in Orleans Parish in August 2006 (Liu and Plyer 2008).

Our estimates of changes in demographic composition also indicate an increasing presence of Hispanics in the affected areas. In both the New Orleans MSA and the Mississippi Gulf Coast, the percentage of residents who are Hispanic increased sharply over time. In the New Orleans MSA, for instance, this percentage increased from 3.2% before the storm to 4.9% in the year after the storm and 6.6% the following year. This increase appears to be driven by migration into the affected areas after Katrina rather than by differential returning among evacuees. Trends in other demographic and family characteristics are consistent with our findings on the determinants of returning.

The distribution of family income (in all four areas examined) and the distribution of education (in every area examined except the Mississippi Gulf Coast) shifted to the right over this time period, with the percentage of residents with high income/education increasing and the percentage of residents with low income/education decreasing. In the New Orleans MSA, these shifts were particularly large. For instance, the percentage of residents with incomes of less than $15,000 a year decreased from 19.3% before the storm to 12.6% in the second year after the storm, and the percentage with incomes of $75,000 or more increased from 20.8% to 31.3%. In terms of education, the percentage of residents without a high school degree decreased from 15.7% to 10.4%, and the percentage of residents who attended college increased from 51.5% to 58.1%.

One explanation for the shift in the income distribution is that low-income evacuees were more likely than high-income evacuees to evacuate to distant locations (Frey et al. 2007), which increased the financial cost of returning and made it harder to learn about the recovery of their pre-Katrina areas. In addition, the areas that experienced extensive damage became more expensive places to live in the aftermath of Katrina. In the city of New Orleans, for instance, the price of housing increased by about 50% from 2004 to 2006 (Vigdor 2008). Finally, the shift may reflect that higher-income evacuees had greater wealth or homeowners insurance, making it easier for them to rebuild and return.

The homeownership rate increased sharply in the high-damage areas after Katrina, from 62% before the storm to 71% in the year after the storm. Over the second year after Katrina, however, the homeownership rate in the high-damage areas fell back to its pre-Katrina level. The time trend in the homeownership rate might reflect a variety of factors, including the desire of different types of evacuees to return, the timing and extent of government subsidies to rebuilding owner-occupied and rental housing, and government regulations regarding demolition of damaged properties and construction of new housing.

LONGER-TERM PROSPECTS

Our estimates in the previous section cover changes in the affected areas in the first two years after Katrina. Also of interest are the longer-term prospects of these areas, particularly New Orleans and the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Disaster research documents many instances in which cities and areas have recovered economically from catastrophic disasters and restored their populations (Friesema et al. 1979; Pais and Elliott 2008; Vigdor 2008; Wright, Rossi, and Wright 1979). Indeed, full recovery of an area’s population appears to be the norm rather than the exception. A review of the disaster literature indicates the main determinants of whether an area recovers are the strength of an area’s economic foundation before the disaster (Fothergill et al. 1999; Vigdor 2008), the cause of the disaster (natural, technological, or both) (Erikson 1976; Picou and Marshall 2007), and the amount of governmental and private resources available for recovery as well as the allocation of those resources (Bolin and Bolton 1986; Peacock and Girard 1997).

The evidence for New Orleans on these determinants is mixed. On the negative side, the city and the surrounding area were in a somewhat precarious situation before Katrina. The city’s population had been declining since the 1960s, and its economic foundation had greatly eroded (Vigdor 2008). At least one economist has argued that the New Orleans area maintained a relatively large population only because a sufficiently large supply of housing built in more-robust economic times kept housing prices low, compensating workers for the relative lack of economic opportunity (Vigdor 2008). Katrina destroyed or seriously damaged much of the affordable housing in New Orleans, thus eliminating New Orleans’ advantage in the housing market.

Others have argued that for New Orleans, Katrina was not only a natural disaster but also a social and technological disaster because of the slow and uncoordinated relief effort, the breaching of the levees, and the contamination of the area with hazardous materials (Picou and Marshall 2007). Social and technological disasters frequently cause residents to blame and distrust individuals within the community, the government, and other social institutions, which in turn often results in corrosive social cycles that impede an area’s recovery and may ultimately lead to its demise (Erikson 1976; Picou and Marshall 2007). Media coverage in the aftermath of the storm also left the impression that New Orleans was a blighted, dangerous place, thus discouraging tourism (Davidson 2006; Oberman 2006).

On the positive side, oil extraction and shipping—two other mainstays of the New Orleans economy—remain tied to the area. New Orleans is close to offshore oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico. Louisiana ranks eighth among U.S. states in oil reserves, and in 2008, had 17% of the nation’s crude-oil refinery capacity. The New Orleans area is home to the Port of South Louisiana and the Port of New Orleans, which rank third and fourth, respectively, among U.S. ports in total world trade (Cieslak 2005).

In contrast to New Orleans, the prospects for the recovery of the Mississippi Gulf Coast appear brighter and more certain. When Katrina struck, the Mississippi Gulf Coast areas affected by the storm—particularly the Gulfport-Biloxi MSA—were enjoying robust population and job growth. The combined population of the three Gulf Coast counties (Hancock, Harrison, and Jackson), which include the cities of Biloxi, Gulfport, and Pascagoula, grew 16% between 1990 and 2000, and grew 52% between 1960 and 2000. Total nonfarm wage and salary employment in the Gulfport-Biloxi MSA grew 58% between 1990 and 2004, well above the growth rate nationwide (20%).

An important stimulus to employment growth in the Gulfport-Biloxi MSA was the rise of the gaming and hospitality industry after the Mississippi legislature passed a law in 1990 permitting casinos on floating barges. Gulfport-Biloxi’s employment in leisure and hospitality more than tripled between 1990 and 2004. In 2004, 26% of nonfarm wage and salary employment in Gulfport-Biloxi was in leisure and hospitality; and in Harrison County—the largest county in the Gulfport-Biloxi MSA—14% of employment was specifically in casino hotels (Garber et al. 2006). Rebuilding of the casinos occurred relatively rapidly in the wake of the storm—perhaps encouraged by legislation permitting casinos to be built on dry ground—thus ensuring casinos as an economic base for the Gulfport-Biloxi area (Davidson 2006).

CONCLUSION

Although the longer-term prospects of the areas affected by Hurricane Katrina are somewhat uncertain, the short-run effects of the storm and the patterns of return migration are relatively clear. Overall, the results presented in this article indicate sharp differences between those who returned to their pre-Katrina areas and those who did not. The probability of returning during the first year after Katrina increased with an evacuee’s age and decreased with the severity of damage in the evacuee’s county of origin. Blacks were less likely to return than whites, but this difference is primarily related to the geographical pattern of storm damage rather than to race per se. In high-damage areas, evacuees with children were less likely to return than those without children.

The difference between the composition of returnees and the composition of non-returnees is the primary force behind changes in the composition of the affected areas in the first two years after the storm. Katrina is associated with substantial shifts in racial composition (namely, a decrease in the percentage of residents who are black) and an increasing presence of Hispanics. Katrina is also associated with an increase in the percentage of older residents, a decrease in the percentage of residents with low income/education, and an increase in the percentage of residents with high income/education.

These findings have important implications not only for the individuals and areas affected by this particular storm but also for those responsible for managing recoveries from future natural disasters. Our results suggest that when formulating expectations about who will return after a natural disaster, one should consider the geographic pattern of damage, the age distribution of evacuees, and their needs for public services. The results also suggest that disasters may affect the overall demographic composition of an area and increase the overall levels of family income and educational attainment in the affected areas—specifically, these areas may lose some of their more-disadvantaged residents.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Alison Aughinbaugh, Joel Elvery, Mark Loewenstein, and Allison Plyer; two anonymous referees; and seminar participants at the University of Maryland, the University of Michigan, the Brookings Institution, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the 2007 annual meeting of the Society of Labor Economists, the 2007 annual meeting of the Southern Economic Association, and the 2008 annual meeting of the Population Association of America for useful comments.

We thank Narayan Sastry for providing data from the Displaced New Orleans Residents Pilot Study. The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics. A longer version of this article is available as BLS Working Paper 428.

Footnotes

For simplicity, we model the return decision in an individual context. A family’s decision to return could be modeled by aggregating family members’ individual utility and returning costs.

Counties along the Gulf Coast within 100–200 miles of the storm center are Baldwin and Mobile counties in Alabama; Assumption, Iberia, St. James, St. Mary, and Terrebonne parishes in Louisiana; and George and Jackson counties in Mississippi.

These counties are listed in Table 3.

As a check on the sensitivity of our findings on return migration to the potential selectivity of evacuation, we added non-evacuees to the sample and treated them as returnees. The regression results were qualitatively similar to the ones we report.

Evacuees are observed in the CPS sample for a maximum of 5 months and for an average of 3 months. In the regression estimates, we adjust the standard errors to account for the existence of multiple observations per individual.

The CPS Katrina questions did not ask whether evacuees were homeowners prior to the storm. However, because the CPS asks about homeownership at the time of interview, pre-Katrina homeownership rates are known for evacuees who returned to their pre-Katrina residences. Among these evacuees, an estimated 85% owned their homes, which is greater than the homeownership rate of 74% among all residents of Katrina-affected areas before the storm—suggesting that returnees were disproportionately homeowners.

A joint test that the marginal effects of the education variables are zero can be strongly rejected for both high-damage (χ2 = 399.70; p value = .00) and low-damage (χ2 = 81.62; p value = .00) areas.

About two-thirds of the 344 sampled cases were located, 79% of located cases were contacted, and 88% of those contacted completed a questionnaire.

Further evidence on the racial pattern of hurricane damage across New Orleans neighborhoods is provided in Groen and Polivka (2009).

REFERENCES

- Baker J, Shaw WD, Bell D, Brody S, Riddel M, Woodward RT, Neilson W. “Explaining Subjective Risks of Hurricanes and the Role of Risks in Intended Moving and Location Choice Models”. Natural Hazards Review. 2009;10:102–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bolin RC, Bolton PA. Race, Religion and Ethnicity in Disaster Recovery. Boulder: Institute of Behavioral Science, University of Colorado; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bolin RC, Stanford L. The Northridge Earthquake: Vulnerability and Disaster. New York: Routledge; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borjas GJ. “Economic Theory and International Migration”. International Migration Review. 1989;23:457–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borjas GJ, Bronars SG, Trejo SJ. “Self-selection and Internal Migration in the United States”. Journal of Urban Economics. 1992;32:159–85. doi: 10.1016/0094-1190(92)90003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookings Institution “New Orleans After the Storm: Lessons From the Past, a Plan for the Future.”. 2005. Report. Brookings Institution, Washington, DC.

- Cahoon LS, Herz DE, Ning RC, Polivka AE, Reed ME, Robison EL, Weyland GD. “The Current Population Survey Response to Hurricane Katrina”. Monthly Labor Review. 2006;129(8):40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Chamlee-Wright E, Rothschild DM. Mercatus Policy Series. Policy Comment No. 9. Mercatus Center at George Mason University; Arlington, VA: 2007. “Disastrous Uncertainty: How Government Disaster Policy Undermines Community Rebound.”. [Google Scholar]

- Chamlee-Wright E, Storr VH. “‘There’s No Place Like New Orleans’: Sense of Place and Community Recovery in the Ninth Ward After Hurricane Katrina”. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2009;30:615–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cieslak V. “Ports in Louisiana: New Orleans, South Louisiana, and Baton Rouge.”. 2005. CRS Report RS22297. Congressional Research Service, Washington, DC.

- DaVanzo JS, Morrison PA. “Return and Other Sequences of Migration in the United States”. Demography. 1981;18:85–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson C. “The Gulf Coast’s Tourism Comeback: Playing for Even Higher Stakes?”. Econ-South. 2006;8(3) [Google Scholar]

- Elliott JR, Pais J. “Race, Class, and Hurricane Katrina: Social Differences in Human Responses to Disaster”. Social Science Research. 2006;35:295–321. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson KT. Everything in Its Path: Destruction of Community in the Buffalo Creek Flood. New York: Simon and Schuster; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Falk WW. Rooted in Place: Family and Belonging in a Southern Black Community. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Falk WW, Hunt MO, Hunt LL. “Hurricane Katrina and New Orleanians’ Sense of Place: Return and Reconstitution or ‘Gone With the Wind’?”. Du Bois Review. 2006;3:115–28. [Google Scholar]

- Fothergill A, Maestas EGM, Darlington JD. “Race, Ethnicity and Disasters in the Untied States: A Review of the Literature”. Disasters. 1999;23:156–73. doi: 10.1111/1467-7717.00111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey WH, Singer A, Park D. “Resettling New Orleans: The First Full Picture From the Census.”. 2007. Report. Brookings Institution, Washington, DC.

- Friesema HP, Caporaso JA, Goldstein G, Lineberry RL, McCleary R. Aftermath: Communities After Natural Disasters. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz CE. “Disasters.”. In: Merton RK, Nisbet RA, editors. Contemporary Social Problems. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World; 1961. pp. 651–94. [Google Scholar]

- Garber M, Unger L, White J, Wohlford L. “Hurricane Katrina’s Effects on Industry Employment and Wages”. Monthly Labor Review. 2006;129(8):22–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gieryn T. “A Space for Place in Sociology”. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000;26:463–96. [Google Scholar]

- Girard C, Peacock WG. “Ethnicity and Segregation: Post-Hurricane Relocation.”. In: Peacock WG, Morrow BH, Gladwin H, editors. Hurricane Andrew: Ethnicity, Gender and the Sociology of Disasters. New York: Routledge; 1997. pp. 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Gladwin H, Peacock WG. “Warning and Evacuation: A Night for Hard Houses.”. In: Peacock WG, Morrow BH, Gladwin H, editors. Hurricane Andrew: Ethnicity, Gender and the Sociology of Disasters. New York: Routledge; 1997. pp. 52–72. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood MJ. “Research on Internal Migration in the United States: A Survey”. Journal of Economic Literature. 1975;13:397–433. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood MJ. “Human Migration: Theory, Models, and Empirical Studies”. Journal of Regional Science. 1985;25:521–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9787.1985.tb00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groen JA, Polivka AE. “The Effect of Hurricane Katrina on the Labor Market Outcomes of Evacuees”. American Economic Review. 2008a;98(2):43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Groen JA, Polivka AE. “Hurricane Katrina Evacuees: Who They Are, Where They Are, and How They Are Faring”. Monthly Labor Review. 2008b;131(3):32–51. [Google Scholar]

- Groen JA, Polivka AE. “Going Home after Hurricane Katrina: Determinants of Return Migration and Changes in Affected Areas” BLS Working Paper 428. Bureau of Labor Statistics; Washington, DC: 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney TJ, Elliott JR, Fussell E. “Families and Hurricane Response: Evacuation, Separation, and the Emotional Toll of Hurricane Katrina.”. In: Brunsma DL, Overfelt D, Picou JS, editors. The Sociology of Katrina: Perspectives on a Modern Catastrophe. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield; 2007. pp. 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Hummon DM. Commonplaces: Community Ideology and Identity in American Culture. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]