Abstract

Subunit a plays a key role in coupling H+ transport to rotations of the subunit c-ring in F1Fo ATP synthase. In Escherichia coli, H+ binding and release occur at Asp-61 in the middle of the second transmembrane helix (TMH) of Fo subunit c. Based upon the Ag+ sensitivity of Cys substituted into subunit a, H+ are thought to reach Asp-61 via aqueous pathways mapping to surfaces of TMH 2–5. In this study we have extended characterization of the most Ag+-sensitive residues in subunit a with cysteine reactive methanethiosulfonate (MTS) reagents and Cd2+. The effect of these reagents on ATPase-coupled H+ transport was measured using inside-out membrane vesicles. Cd2+ inhibited the activity of all Ag+-sensitive Cys on the cytoplasmic side of the TMHs, and three of these substitutions were also sensitive to inhibition by MTS reagents. On the other hand, Cd2+ did not inhibit the activities of substitutions at residues 119 and 120 on the periplasmic side of TMH2, and residues 214 and 215 in TMH4 and 252 in TMH5 at the center of the membrane. When inside-out membrane vesicles from each of these substitutions were sonicated during Cd2+ treatment to expose the periplasmic surface, the ATPase-coupled H+ transport activity was strongly inhibited. The periplasmic access to N214C and Q252C, and their positioning in the protein at the a-c interface, is consistent with previous proposals that these residues may be involved in gating H+ access from the periplasmic half-channel to Asp-61 during the protonation step.

Keywords: ATP Synthase, F1Fo ATPase, Membrane Energetics, Membrane Proteins, Mutant, Proton Transport

Introduction

The H+-transporting F1Fo ATP synthases of oxidative phosphorylation utilize the energy of a transmembrane electrochemical gradient of H+ or Na+ to mechanically drive the synthesis of ATP via two coupled rotary motors in the F1 and Fo sectors of the enzyme (1–4). In the intact enzyme, H+ transport through the transmembrane Fo sector is coupled to ATP synthesis or hydrolysis in the F1 sector at the surface of the membrane. Homologous enzymes are found in mitochondria, chloroplasts, and many bacteria (5). In Escherichia coli and other eubacteria, F1 consists of five subunits in an α3β3γ1δ1ϵ1 stoichiometry (5). Fo is composed of three subunits in a likely ratio of a1b2c10 in E. coli and Bacillus subtilis PS3 (6, 7), a1b2c11 in the Na+ translocating Ilyobacter tartaricus ATP synthase (4, 8), and as many as 15 c subunits in other bacterial species (9). Subunit c spans the membrane as a helical hairpin with the first transmembrane helix (TMH)2 on the inside and the second TMH on the outside of the c-ring (8–10). The high resolution x-ray structure of the I. tartaricus c11-ring revealed the sodium binding site at the periphery of the ring with chelating groups to the Na+ extending from two interacting subunits in an extensive hydrogen bonding network (8, 11). The essential I. tartaricus Glu-65 in the Na+-chelating site corresponds to E. coli Asp-61. Subsequently published structures of H+ binding c-rings from chloroplasts (12), Spirulina platensis (9), and Bacillus pseudofirmus (13) have revealed at least two modes of liganding the proton at the essential side chain carboxyl using alternative hydrogen-bonding networks (13).

In the H+-transporting E. coli enzyme, Asp-61 at the center of the second TMH is thought to undergo protonation and deprotonation as each subunit of the c-ring moves past a stationary subunit a (1–4, 14). In the complete membranous enzyme, the rotation of the c-ring is proposed to be driven by H+ transport at the subunit a/c interface, with ring movement then driving rotation of subunit γ within the α3β3 hexamer of F1 to cause conformational changes in the catalytic sites leading to synthesis and release of ATP (1–4). Subunit a folds in the membrane with 5 TMHs and is thought to provide access channels to the proton-binding Asp-61 residue in the c-ring (14–17). Interaction of the conserved Arg-210 residue in aTMH4 with cTMH2 is thought to be critical during the deprotonation-protonation cycle of cAsp-61 (18–20), and aTMH4 and cTMH2 are known to pack in parallel to each other based upon cross-linking (21).

Previously, we probed Cys residues introduced into the 5 TMHs of subunit a for aqueous accessibility based upon their reactivity with NEM and Ag+ (22–25). Both reagents react preferentially with the thiolate form of the Cys side chain that is expected in a polar, aqueous environment. Two regions of aqueous access were found with distinctly different properties. One region extending from Asn-214 and Arg-210 near the center of the membrane to the cytoplasmic surface of TMH4 contains Cys residues that are sensitive to inhibition by both NEM and Ag+ (Fig. 1). A second set of Ag+-sensitive but NEM-inaccessible residues mapped to the opposite face and periplasmic side of TMH4. Ag+-sensitive and NEM-insensitive Cys residues were also found in TMHs 2, 3, and 5, extending from the center of the membrane to the periplasm. The Ag+-sensitive/NEM-insensitive residues in TMHs 2, 3, 4, and 5 cluster at the interior of the four-helix bundle predicted by cross-linking (Ref. 26 and Fig. 2), and could interact to form a continuous aqueous pathway extending from the periplasmic surface to the center of the membrane.

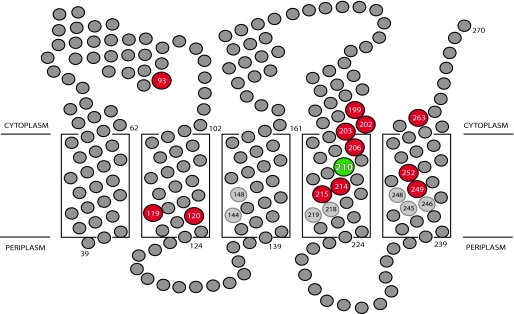

FIGURE 1.

Location of the most Ag+-sensitive cysteine substitutions in a topological model of subunit a. The ATP-driven proton pumping activity of the Cys substitutions highlighted in red was inhibited by >90% on treatment with 40 μm Ag+. Residues colored in gray were less sensitive to inhibition by Ag+. Numbered residues that are shaded in light gray define the positions of disulfide cross-link formation in doubly Cys-substituted mutants. The position of the essential Arg-210 residue in TMH4 is indicated.

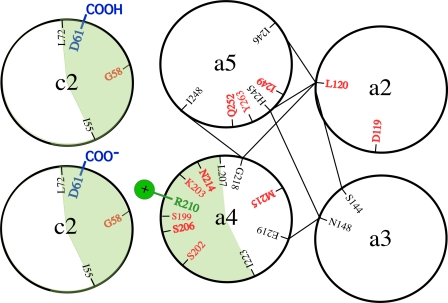

FIGURE 2.

Cross-sectional view of positions of Ag+-sensitive residues in transmembrane regions of subunit a. Cys substitutions showing >90% inhibition of ATP-driven ACMA quenching on treatment with 40 μm Ag+ are depicted in red. The orientation of TMHs 2–4 in a four-helix bundle is suggested by disulfide cross-link formation between the residues connected by fine solid lines. The green shaded areas depict the cross-linkable faces of aTMH4 with cTMH2. TMHs 4 and 5 are predicted to swivel counterclockwise and clockwise, respectively, during the gating of proton access to cAsp-61 from the periplasmic half-channel in the center of the four-helix bundle.

In the experiments reported here, we probed the reactivity of the most Ag+-sensitive Cys residues in subunit a with Cd2+ and methanethiosulfonate (MTS) reagents of varying polarity (see Fig. 1 for location). MTS reagent reactivity was confined to 3 Cys residues in TMH4 that are thought to line the aqueous access pathway to the cytoplasm, i.e. N214C, S206C, and S202C. The Cd2+ reactivity of inverted membrane vesicles was confined to Cys localized to the cytoplasmic side of subunit a. Cd2+-insensitive but Ag+-sensitive residues were found to cluster at the center of the proposed four-helix bundle extending to the periplasm (Fig. 2). However, on sonication of the inverted membrane vesicles, these residues became Cd2+-sensitive, which supports the proposed aqueous accessibility to this region of the protein from the periplasmic face of the membrane. The residues made accessible by sonication include N214C and Q252C, which pack at the interfaces of TMH4 and TMH5 and the surface of the c-ring. Swiveling of helices at this interface was proposed to gate H+ access to cAsp-61 during H+-transport-driven ATP synthesis (27). We suggest that these two Cd2+-sensitive residues may define the gate of H+ access from the periplasmic half-channel to cAsp-61 and then to the second half-channel to the cytoplasm.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cys-substituted Mutants

The cysteine substitutions used here were constructed in plasmid pCMA113 (22), which encodes a subunit a with a hexahistidine tag on the C terminus and genes encoding the other subunits of F1Fo in which all endogenous Cys had been substituted by Ala or Ser (28). Properties of the substitutions were described previously (22–25). Three new substitutions in the Ser-202 codon were generated here using a two-step PCR protocol with a synthetic oligonucleotide encoding the codon change and two wild-type primers (29). PCR products were transferred into pCMA113 directly using unique HindIII (870) and BsrGI (1913) sites (see Ref. 30) for nucleotide numbering). The new mutations were confirmed by sequencing the cloned fragment through the ligation junctions. All experiments were performed with the mutant whole operon plasmid derivative of pCMA113 in the unc operon deletion host strain JWP292 (6).

Membrane Preparation

JWP292 transformant strains were grown in M63 minimal medium containing 0.6% glucose, 2 mg/liter thiamine, 0.2 mm uracil, 1 mm l-arginine, 0.02 mm dihydroxybenzoic acid, and 0.1 mg/ml ampicillin, supplemented with 10% LB medium, and harvested in the late exponential phase of growth (6). Cells were suspended in TMG-acetate buffer (50 mm Tris acetate, 5 mm magnesium acetate, 10% glycerol, pH 7.5) containing 1 mm dithiothreitol, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 0.1 mg/ml of DNase I and disrupted by passage through a French press at 1.38 × 108 nt/m2 and membranes prepared as described (31). Cell debris was cleared by low-speed centrifugation of the lysate at 7,700 × gmax, and membranes were collected by high-speed centrifugation of the cleared lysate at 193,000 × gmax. Membranes were washed once with and then resuspended in TMG-acetate and stored at −80 C. Protein concentrations were determined using a modified Lowry assay (32).

ATP-driven Quenching of ACMA Fluorescence

Aliquots of membranes prepared from JWP292 transformant strains (1.6 mg at 10 mg/ml) were suspended in 3.2 ml of HMK-nitrate buffer (10 mm HEPES-KOH, 1 mm Mg(NO3)2, 10 mm KNO3, pH 7.5) or HMK-chloride buffer (10 mm HEPES-KOH, 5 mm MgCl2, 300 mm KCl, pH 7.5) and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. ACMA was added to 0.3 μg/ml and fluorescence quenching was initiated by the addition of 30 μl 25 mm ATP, pH 7. Each experiment was terminated by adding nigericin to 0.5 μg/ml. The level of fluorescence obtained after addition of nigericin was used as a normalized 100% baseline in calculating the percent quenching due to ATP-driven proton pumping. For NEM treatment, 160-μl aliquots of 10 mg/ml membrane in TMG-acetate buffer were treated with 5 mm NEM for 10 min at room temperature and then diluted into HMK-nitrate buffer before carrying out the quenching assay. The 10-min incubation of untreated control samples resulted in no significant inhibition relative to samples that were not pre-incubated. The HMK-nitrate buffer is that used in previous experiments with Ag+. Treatments with MTS derivatives were performed as for NEM. The MTS compounds were dissolved immediately before use in DMSO solvent at 100 mm and 3.2 μl of reagent mixed with 160 μl of 10 mg/ml membrane in TMG-acetate buffer. After a 10-min incubation at room temperature, the treated membranes were diluted into 3.2 ml HMK-nitrate buffer, and the quenching reaction was carried out as described above. For treatment with Cd2+, 160 μl of 10 mg/ml membrane was suspended in 3.2 ml of HMK-chloride, and CdCl2 was added from an aqueous stock solution to the desired concentration. Following an incubation of 10 min at room temperature the fluorescence quenching reaction was carried out as described above. HMK-chloride buffer was used in these experiments since the ATP-driven ACMA quenching is more robust in this buffer than in HMK-nitrate buffer.

Sonication of Cd2+-treated Membrane Vesicles

An aliquot of 160 μl of inverted membrane vesicles at 10 mg/ml was diluted into 3.2 ml of HMK-chloride buffer and 3.3 μl of 1 m CdCl2 added to a final concentration of 1 mm. The sample was then transferred to an ice-water bath and sonicated for 1 min at 80% of maximum power using an Ultrasonics Sonicator Cell Disruptor with a 1.3-cm diameter tip. Following sonication, the membrane vesicles were incubated for 10 min at 20 °C before initiating the quenching assay. The same sonication procedure carried out with control membrane vesicles lacking Cd2+ led to negligible effects on their quenching activity, i.e. 90 ± 10% of quenching response of vesicles not subjected to sonication.

RESULTS

Testing of Ag+-sensitive Residues for Inhibition by Other Cysteine Reactive Reagents

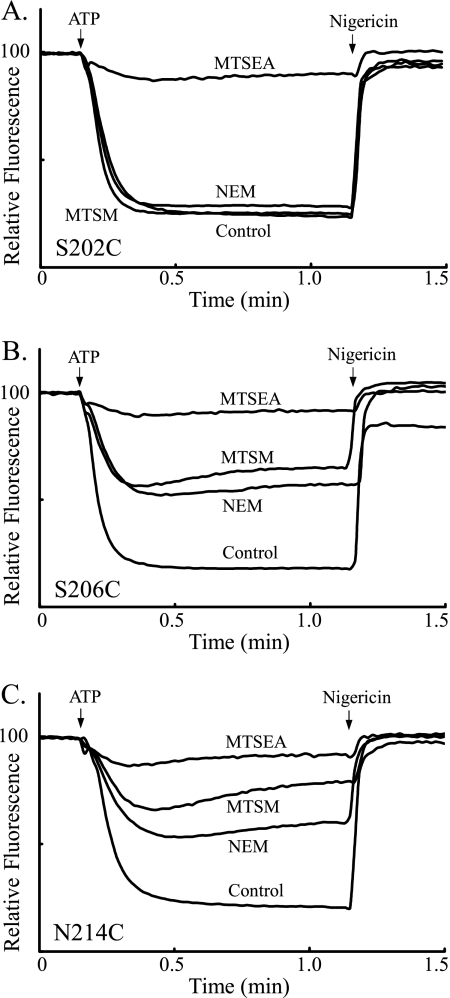

We initially did a survey of the most Ag+-sensitive residues in subunit a to determine their susceptibility to inhibition of the ATP-driven ACMA quenching response by five MTS reagents of varying size and charge (Fig. 1).3 Of the residues tested, three Cys substitutions were most significantly inhibited by two of the MTS reagents tested, i.e. S202C, S206C and N214C with MTSM and MTSEA (Table 1). The three MTSM or MTSEA sensitive substitutions were insensitive to inhibition by the anionic MTSES and MTSCE reagents or the membrane impermeant and cationic MTSET reagent as were the other nine Cys substitutions tested (Table 1). A comparison of the inhibition seen with select reagents and the S202C, S206C, and S214C substitutions is shown in Fig. 3. Two of these substitutions correspond to the two NEM-sensitive residues in subunit a, and NEM was included in these experiments for comparison. The ACMA quenching response of all three substitutions shown in Fig. 3 was nearly abolished by the membrane-permeant MTSEA reagent, which, when protonated, would be cationic. The quenching response of the S206C and N214C substitutions were inhibited significantly by the neutral MTSM and NEM reagents, whereas the S202C quenching response was not significantly affected by these reagents. The inhibition seen with the S206C and N214C substitutions could be attributed to modifications that increase the bulk of the amino acid side chain or reduce its polarity. However, the introduction of a protonatable and potentially positively charged group at these positions by modification with MTSEA is clearly more disruptive. The inhibition pattern seen with S202C differs in that NEM and MTSM are not inhibitory whereas the potentially cationic MTSEA is very inhibitory. A polar side chain at this position is clearly not required since the bulky, hydrophobic adduct formed with NEM is not inhibitory.4 Rather, inhibition may be caused by introduction of the protonatable and potentially positively charged ethylamine moiety.

TABLE 1.

Inhibitor sensitivity of subunit a substitutions

| Mutation and locationa | +Ag/−Agb | +MTSM/−MTSMc | +MTSEA/−MTSEAc | +MTSET/−MTSETc | +MTSES/−MTSESc | +MTSCE/−MTSCEc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 0.90 ± 0.05 | 0.94 ± 0.04 | 0.88 ± 0.06 | 0.95 ± 0.07 | 0.94 ± 0.05 | 0.95 ± 0.07 |

| 1-2 loop | ||||||

| M93C | 0.12 ± 0.00 | 0.98 ± 0.04 | 0.91 ± 0.05 | 0.97 ± 0.04 | 0.96 ± 0.01 | 0.96 ± 0.01 |

| TMH 2 | ||||||

| D119C | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 1.06 ± 0.10 | 0.97 ± 0.05 | 1.00 ± 0.06 | 0.99 ± 0.03 | 0.98 ± 0.03 |

| L120C | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 1.00 ± 0.04 | 0.98 ± 0.03 | 0.94 ± 0.08 | 1.01 ± 0.03 | 1.00 ± 0.03 |

| 3-4 loop & TMH4 | ||||||

| S199C | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.12 | 0.97 ± 0.13 | 0.96 ± 0.06 | 0.98 ± 0.04 | 0.98 ± 0.04 |

| S202C | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.96 ± 0.05 | 0.20 ± 0.05 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.04 |

| K203C | 0.03 ± 0.03 | 0.96 ± 0.05 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 0.98 ± 0.03 | 1.00 ± 0.01 |

| S206C | 0.05 ± 0.03 | 0.60 ± 0.04 | 0.27 ± 0.10 | 0.98 ± 0.03 | 0.98 ± 0.03 | 0.95 ± 0.07 |

| N214C | 0.09 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.11 | 0.36 ± 0.16 | 0.93 ± 0.08 | 0.94 ± 0.09 | 0.90 ± 0.14 |

| M215C | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.90 ± 0.06 | 0.91 ± 0.11 | 0.97 ± 0.06 | 0.96 ± 0.08 | 0.95 ± 0.08 |

| TMH 5 | ||||||

| I249C | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.87 ± 0.13 | 0.88 ± 0.14 | 1.00 ± 0.03 | 0.93 ± 0.08 | 0.98 ± 0.03 |

| Q252C | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.96 ± 0.04 | 0.91 ± 0.03 | 0.97 ± 0.05 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 0.94 ± 0.08 |

| C terminus | ||||||

| Y263C | 0.11 ± 0.00 | 0.82 ± 0.05 | 0.80 ± 0.00 | 0.74 ± 0.01 | 0.73 ± 0.11 | 0.81 ± 0.08 |

a The results presented are the average of two or more determinations ± S.D.

b The +Ag/−Ag ratios are taken from Ref. 25.

c MTS reagents were added at a concentration of 2 mm.

FIGURE 3.

Inhibition of ATP-driven proton pumping by NEM, MTSM, and MTSET with membrane vesicles from the S202C, S206C, and N214C substitutions. ATP-driven quenching of ACMA fluorescence by inverted membrane vesicles was assayed as described under “Experimental Procedures” using HMK-nitrate buffer. Fluorescence quenching was initiated by the addition of ATP at 20 s and terminated by the addition of nigericin at 100 s. The return to the maximum fluorescence reached after the addition of nigericin was used to calculate the relative inhibition of quenching. Fluorescence quenching by mutant vesicles treated with DMSO (control), 5 mm NEM, 2 mm MTSM, and 2 mm MTSEA.

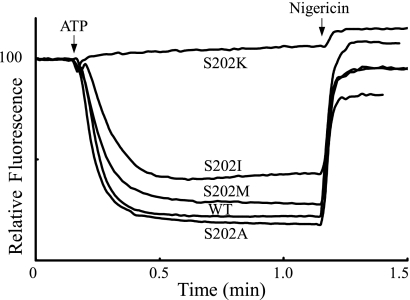

To further test the likely cause of inhibition on modification of the Ser-202 residue, several site directed mutants at residue 202 were constructed and then tested for ATP-driven ACMA quenching (Fig. 4). The small Ala side chain substitution was non-inhibitory confirming the lack of need for a polar group at this position. The bulky and hydrophobic Ile and Met substitutions resulted in very modest reductions in the quenching response. These results are consistent with the previous finding that S202C does react with radioactive NEM, but the reaction is not inhibitory (23).4 On the other hand, the S202K substitution abolished activity and suggests that the key inhibitory element here is the protonatable and potentially positively charged side chain.

FIGURE 4.

ATP-driven proton pumping activity with different substitutions in Ser-202 of subunit a. The activity of the S202A, S202I, S202M, and S202K substitutions are compared with wild type.

Sensitivity of Ag+-sensitive Residues to Inhibition by Cd2+

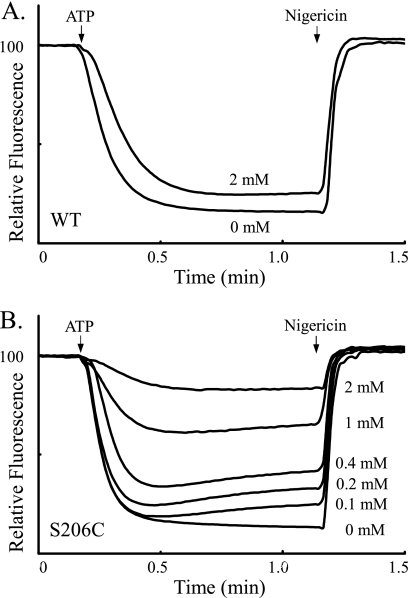

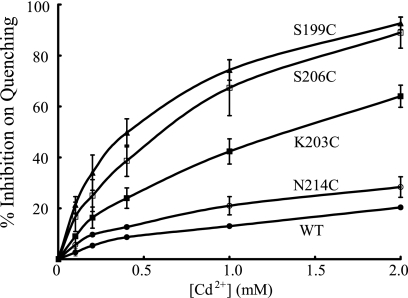

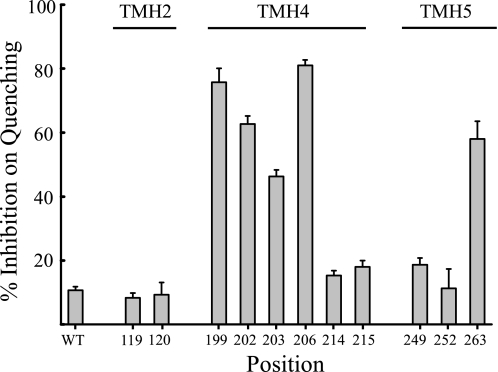

The most Ag+-sensitive Cys substitutions in subunit a were also surveyed for sensitivity to inhibition by Cd2+. The concentration dependence for Cd2+ inhibition of ACMA quenching by S206C membrane vesicles is illustrated in Fig. 5. Inhibition increased gradually over the range of 0.1–2 mm with near maximal inhibition being observed at 2 mm Cd2+ (Fig. 5B). Very modest inhibition of quenching was observed when wild-type membranes were treated with 2 mm Cd2+ (Fig. 5A). The range of Cd2+-sensitivity of different Ag+-sensitive mutants is illustrated in Fig. 6 with S199C and S206C showing greatest sensitivity in contrast to the very insensitive N214C mutant. The Cd2+ sensitivity of the TMH Cys substitutions surveyed in this study is compared in Fig. 7. About half of the mutants were inhibited significantly by Cd2+ whereas the other half were as resistant or only slightly more sensitive to inhibition than wild type. The M93C substitution proved to be Cd2+-insensitive (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

Inhibition of ATP-driven proton pumping by Cd2+ with S206C-substituted subunit a. ATP-driven quenching of ACMA fluorescence was measured as described under “Experimental Procedures” using HMK-chloride buffer. Membrane vesicles were treated with varying concentrations of CdCl2 for 10 min at room temperature prior to initiation of the assay with ATP. The return of the fluorescent signal to the maximum reached after the addition of nigericin was used to calculate the inhibition values given in Fig. 6. The activity and extent of Cd2+ inhibition of wild-type (A) and S206C (B) membrane vesicles are compared.

FIGURE 6.

Concentration dependence of Cd2+ inhibition of ATP-driven proton pumping with different Cys substitutions in subunit a. The percent inhibition of ATP-driven proton pumping was calculated as described in Fig. 5.

FIGURE 7.

Relative inhibition of ATP-driven proton pumping by Cd2+ with Cys substitutions in TMHs 2, 4, and 5 of subunit a. Membrane vesicles were treated with 1 mm Cd2+ and the extent of inhibition calculated as described in Fig. 5. The position of the substituted residues in a two dimensional model of subunit a is indicated in Fig. 1.

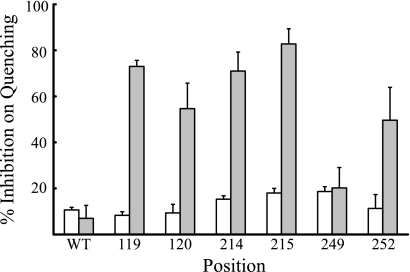

Ag+-sensitive but Cd2+-insensitive Residues Locate to the Periplasmic Side of the Membrane

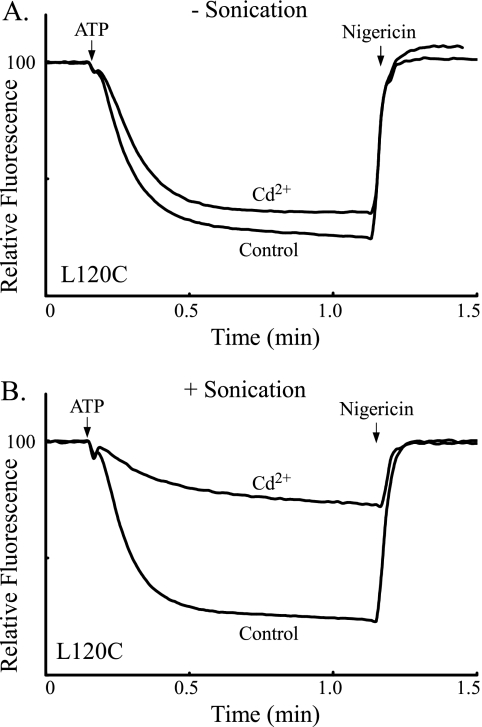

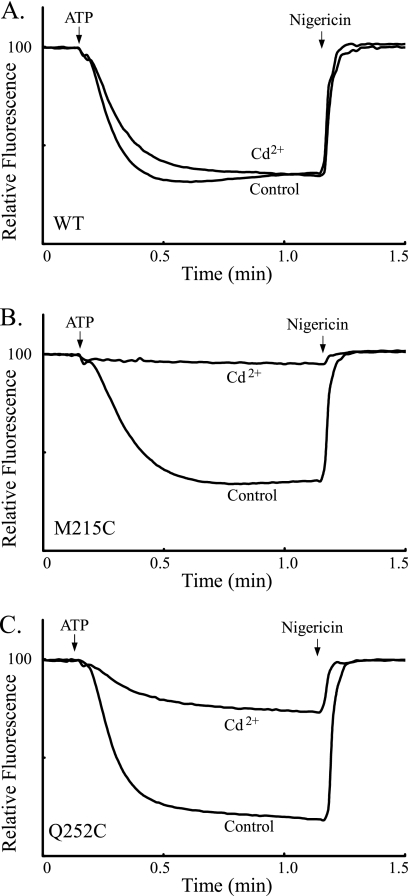

In the current topographical models of subunit a, the Ag+-sensitive but Cd2+-insensitive D119C and L120C substitutions are located on the periplasmic side of TMH2 and would be most easily accessed from the aqueous compartment at the interior of the inverted membrane vesicles used here (Fig. 1). To test whether the Cd2+ insensitivity of these residues might be due to Cd2+ impermeability to the interior aqueous compartment, we disrupted L120C membrane vesicles by sonication during the course of Cd2+ treatment. The sonication treatment led to a marked increase in the Cd2+ inhibition of ATP-driven ACMA quenching as shown in Fig. 8. Similar increases in Cd2+ sensitivity were seen on sonication of M215C and Q252C membrane vesicles that have substitutions in TMH4 and TMH5 respectively (Fig. 9). The Cd2+ sensitivity of D119C and N214C membrane vesicles was also markedly increased by sonication during Cd2+ treatment (Fig. 10). Of the Ag+-sensitive but Cd2+-insensitive substitutions identified in Fig. 7, I249C membrane vesicles were the only set where simultaneous sonication during Cd2+ treatment did not increase the inhibition of the ACMA quenching response (Fig. 10).

FIGURE 8.

Effect of sonication during Cd2+ treatment on inhibition of ATP-driven proton pumping with L120C membrane vesicles. Inverted membrane vesicles were treated or not treated with 1 mm Cd2+ and subjected or not subjected to 1 min of sonication as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

FIGURE 9.

Effect of sonication during Cd2+ treatment on inhibition of ATP-driven proton pumping with M215C and Q252C membrane vesicles. Inverted membrane vesicles were treated with 1 mm Cd2+ and subjected to 1 min of sonication as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Control membrane vesicles were sonicated in the absence of Cd2+. A, wild type; B, M215C; C, Q252C.

FIGURE 10.

Sonication potentiates Cd2+ inhibition with Cys substitutions that may be aqueous inaccessible from the cytoplasmic side of inverted membrane vesicles. Experiments were carried out as described in Figs. 8 and 9 and relative inhibition calculated as described in the legend to Fig. 5. Open bars, no sonication; grey bars, with sonication.

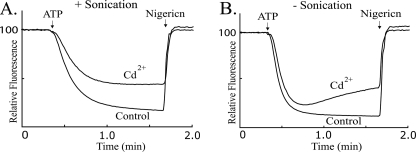

Probing the Periplasmic Exposure of His-245 with Cd2+

His-245 is likely to pack at the center of the helical bundle mediating aqueous access from the periplasm and perhaps serve as a buffer to the protons entering the half-channel (33). The H245C substitution results in an inactive enzyme, which led us to probe the Ag+ sensitivity of H245C in the active D119H/H245C suppressor strain, where we found the ACMA quenching response to be only modestly sensitive to inhibition by Ag+ (23). To test possible access to H245C from the periplasm, we compared the effects of Cd2+ in sonicated and unsonicated inverted membrane vesicles. As shown in Fig. 11A, Cd2+ treatment of sonicated membrane vesicles resulted in an ∼40% inhibition of the ACMA quenching response. In contrast, the initial rate of ATP-driven ACMA quenching by unsonicated membrane vesicles was little effected by Cd2+ treatment (Fig. 11B). However, as the ATP-driven ACMA quenching reaction progressed beyond 20 s, gradual inhibition ensued (Fig. 11B). Because these membrane vesicles had been incubated in HMK-chloride buffer with 1 mm Cd2+ for 10 min prior to the addition of ATP, we postulate that the gradual access of Cd2+ to H245C during enzyme function must result from dynamic movements that enhance aqueous access from the cytoplasmic side of the membrane.

FIGURE 11.

Sonication potentiates Cd2+ inhibition with the H245C substitution in aTMH5. Inverted membrane vesicles were treated with 1 mm Cd2+ and subjected or not subjected to 1 min of sonication as described in Fig. 8. A, quenching response of vesicles sonicated in the presence or absence of Cd2+. B, quenching response of non-sonicated vesicles in the presence or absence of Cd2+. The likely location of H245C on the periplasmic face at the center of the four-helix bundle is indicated in Figs. 1 and 2.

DISCUSSION

Only three of twelve of the most Ag+-sensitive Cys substitutions in subunit a proved to be sensitive to any of the MTS reagents tested, as assessed by inhibition of ATP-driven ACMA quenching activity. Inhibition was only observed with the smallest of the reagents tested, i.e. MTSM and MTSEA, and then with only the S202C, S206C, and N214C substitutions. The size or possibly the charge of the groups on MTSET, MTSCE, and MTSES may prevent access to any of the twelve Cys substitutions tested in Table 1. It is unclear whether MTSM and MTSET have access to the nine substitutions that are insensitive to inhibition by these reagents. Five of these substitutions, i.e. D119C, L120C, M215C, I249C, and Q252C, are not accessible to labeling with [14C]NEM (22, 23), so there may be a correlation between NEM and MTS-reagent accessibility. On the other hand, the S199C, S202C, and S203C are all labeled by [14C]NEM, although NEM is not inhibitory (23, 25).4 It is thus possible that some of the Cys substitutions studied here are modified by the MTS reagents and that the modification is not inhibitory.

For S202C, S206C, and N214C, the greater sensitivity to inhibition by MTSEA versus MTSM can probably be attributed to the disruptive effects caused by a positively charged amine introduced into these transmembrane positions. For S202C this conclusion is supported by the mutagenesis studies where the S202K substitution was much more disruptive than the S202M or S202I substitutions. In the case of S206C, the disruption of function by MTSM and NEM can be attributed at least partially in introduction of a bulky group at this position. This conclusion is supported by mutagenesis studies where the S206A substitution is non-disruptive (34), whereas the S206L substitution nearly abolishes function (35). The size of the group introduced at N214C also appears to be a critical factor in inhibition of function in that the N214L substitution is much more debilitating than the N214V substitution (36).

The three residues showing MTS reagent sensitivity, i.e. S202C, S206C, and N214C, are thought to pack at the interface of aTMH4 and the peripheral surface of cTMH2 of the c-ring. The rate of reaction of MTS reagents with ionized thiolates is > 5 × 109 times that of reaction with a neutral thiol (37), so it is very likely that the reactive Cys residues report an aqueous accessible space in this transmembrane region of the protein. S206C and N214C are the only two substitutions in subunit a that are sensitive to major inhibition by NEM and, in models derived from cross-linking evidence and the c-ring x-ray structures, would pack around the MTSEA-sensitive pocket in subunit c that surrounds Asp-61 (38). The only Cys substitution in subunit c that is inhibited by NEM is cG58C, and it also packs in this pocket (38).

The activity of all Ag+-sensitive Cys substitutions mapping toward the cytoplasmic side of aTMH4 and aTMH5 was inhibited by treatment with CdCl2 (Fig. 1). Cd2+-sensitive residues 199, 202, 203, and 263 are likely to cluster at the cytoplasmic surface of TMHs 4 and 5 where they could interact with the Cd2+-sensitive cQ52C substitution in subunit c (39). In contrast to these residues, the activity of Cys substitutions at positions 119, 120, 214, 215, and 252 was not inhibited by Cd2+. Each of these substitutions localize more toward the center or periplasmic side of the membrane. For each of these substitutions, sonication of inside-out membrane vesicles during Cd2+ treatment to expose the periplasmic surface resulted in strong inhibition of ATP-driven ACMA quenching activity. We conclude that Cd2+ cannot permeate the E. coli inner membrane and that the permeability barrier to Cd2+ explains the lack of inhibition seen with the 119, 120, 214, 215, and 252 substitutions in the absence of sonication. Residues 206 and 214 would pack directly above and below the essential Arg-210 residue in an α-helical model of TMH4 (Fig. 1). Based upon these results we predict that Ser-206 provides aqueous access to the half-channel extending to the cytoplasm and that Asn-214 is accessed from the periplasmic half-channel at the interior of the four-helix bundle formed by TMHs 2–4 (Figs. 1 and 2).

The accessibility of residues 214 and 252 from the periplasm, and their positioning in the protein at the interface of the c-ring (Fig. 2), is consistent with a previous proposal that these residues may be involved in gating H+ access from the periplasmic half-channel to cAsp-61 during the protonation step (27). Based upon previous cross-linking experiments, gating was proposed to occur via helical swiveling of both aTMH4 and aTMH5, with simultaneous movement of Asn-214 and Gln-252 toward the c-ring interface, and with the coordinated movement of Arg-210 away from a deprotonated c-subunit to facilitate its reprotonation from periplasmic half-channel. The effects of sonication reported here on Cd2+ inhibition support the idea of aqueous access from the periplasm to not only residues Asn-214 and Gln-252, but also to Asp-119, Leu-120, Met-215, and His-245 in the predicted center of the four-helix bundle. Based upon their predicted depth of packing in the membrane, we would predict that the transported proton would initially encounter the D119/L120/M215/H245 region of the protein before moving to the predicted Asn-214 and Gln-252 gating residues. We are attracted to the idea that His-245 may initially buffer proton accumulation in this region (33), and a role for a histidine at this position as a buffering residue is supported by the D119H second site suppressor to the inactivating H245C mutation (15). The possible role of His-245 in capturing protons at near neutral pH is also supported by its replacement with a Lys in alkalophilic bacteria at a position equivalent to Gly-218 in E. coli (40), and the necessity of this alkalophilic-specific Lys for function at alkaline pH (41, 42). The nearness of positions 218 and 245 in subunit a of E. coli is supported not only by cross-linking studies (26) but also by second site suppressor substitutions in Gly-218 to the H245G mutation (43).

Acknowledgment

We thank Hun Sun Chung for assistance in some of these experiments.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by United States Public Health Service Grant GM23105 from the National Institutes of Health.

We were not able to confirm the high Ag+ sensitivity of the L195C and V198C substitutions reported previously (25) and did not include these substitutions in this study.

The reaction of [14C]NEM with many of the residues listed in Table 1 has been reported previously and normalized to the most NEM-reactive residue S206C (22, 23). The reactivity of additional Cys substitutions with [14C]NEM is reported in Angevine, C.A., Ph.D Thesis, University of Wisconsin, Madison, 2004. These residues include: V198C (10%), S199C (100%), L200C (29%), L201C (14%), S202C (61%), K203C (72%), P204C (5%), and V205C (9%), where the relative reactivity is normalized to that of S206C at 100%.

- TMH

- transmembrane helix

- ACMA

- 9-amino-6-chloro-2-methoxyacridine

- βMSH

- β-mercaptoethanol

- MTS

- methanethiosulfonate

- MTSM

- MTS-methyl

- MTSEA

- MTS-ethylamino

- MTSET

- MTS-ethyl(trimethylammonium)

- MTSCE

- MTS-carboxylethyl

- MTSES

- MTS-ethylsulfonate

- NEM

- N-ethylmaleimide.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yoshida M., Muneyuki E., Hisabori T. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Biol. 2, 669–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capaldi R. A., Aggeler R. (2002) Trends Biochem. Sci. 27, 154–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakamoto R. K., Baylis Scanlon J. A., Al-Shawi M. K. (2008) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 476, 43–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Ballmoos C., Wiedenmann A., Dimroth P. (2009) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 649–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Senior A. E. (1988) Physiol. Rev. 68, 177–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang W., Hermolin J., Fillingame R. H. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 4966–4971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitome N., Suzuki T., Hayashi S., Yoshida M. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 12159–12164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meier T., Polzer P., Diederichs K., Welte W., Dimroth P. (2005) Science 308, 659–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pogoryelov D., Yildiz O., Faraldo-Gómez J. D., Meier T. (2009) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 1068–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones P. C., Jiang W., Fillingame R. H. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 17178–17185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meier T., Krah A., Bond P. J., Pogoryelov D., Diederichs K., Faraldo-Gómez J. D. (2009) J. Mol. Biol. 391, 498–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krah A., Pogoryelov D., Meier T., Faraldo-Gómez J. D. (2010) J. Mol. Biol. 395, 20–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Preiss L., Yildiz O., Hicks D. B., Krulwich T. A., Meier T. (2010) Plos. Biol. 8, e1000443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fillingame R. H., Angevine C. M., Dmitriev O. Y. (2003) FEBS Lett. 555, 29–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valiyaveetil F. I., Fillingame R. H. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 16241–16247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long J. C., Wang S., Vik S. B. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 16235–16240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wada T., Long J. C., Zhang D., Vik S. B. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 17353–17357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cain B. D. (2000) J. Bioenerg. Biomembrane 32, 365–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hatch L. P., Cox G. B., Howitt S. M. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 29407–29412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valiyaveetil F. I., Fillingame R. H. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 32635–32641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang W., Fillingame R. H. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 6607–6612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Angevine C. M., Fillingame R. H. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 6066–6074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Angevine C. M., Herold K. A., Fillingame R. H. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 13179–13183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angevine C. M., Herold K. A., Vincent O. D., Fillingame R. H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 9001–9007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore K. J., Angevine C. M., Vincent O. D., Schwem B. E., Fillingame R. H. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 13044–13052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwem B. E., Fillingame R. H. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 37861–37867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore K. J., Fillingame R. H. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 31726–31735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuo P. H., Ketchum C. J., Nakamoto R. K. (1998) FEBS Lett. 426, 217–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barik S. (1996) Methods Mol. Biol. 57, 203–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walker J. E., Saraste M., Gay N. J. (1984) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 768, 164–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mosher M. E., White L. K., Hermolin J., Fillingame R. H. (1985) J. Biol. Chem. 260, 4807–4814 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fillingame R. H. (1975) J. Bacteriol. 124, 870–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mulkidjanian A. Y. (2006) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1757, 415–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howitt S. M., Gibson F., Cox G. B. (1988) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 936, 74–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cain B. D., Simoni R. D. (1986) J. Biol. Chem. 261, 10043–10050 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cain B. D., Simoni R. D. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 3292–3300 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberts D. D., Lewis S. D., Ballou D. P., Olson S. T., Shafer J. A. (1986) Biochemistry 25, 5595–5601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steed P. R., Fillingame R. H. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 12365–12372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steed P. R., Fillingame R. H. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 23243–23250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hicks D. B., Liu J., Fujisawa M., Krulwich T. A. (2010) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1797, 1362–1377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Z., Hicks D. B., Guffanti A. A., Baldwin K., Krulwich T. A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 26546–26554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McMillan D. G., Keis S., Dimroth P., Cook G. M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 17395–17404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hartzog P. E., Cain B. D. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 32313–32317 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]