Abstract

The functions of dicot sucrose transporters (SUTs) in apoplastic phloem loading of sucrose are well established; however, whether SUTs similarly function in monocots was unresolved. To address this question, we recently provided genetic evidence that ZmSUT1 from maize (Zea mays) is required for efficient phloem loading. sut1-m1 mutant plants hyperaccumulate carbohydrates in leaves, are defective in loading sucrose into the phloem, and have altered biomass partitioning. Presumably due to the hyperaccumulation of soluble sugars in leaves, mutations in ZmSUT1 lead to downregulation of chlorophyll accumulation, photosynthesis and stomatal conductance. However, because we had identified only a single mutant allele, we were not able to exclude the possibility that the mutant phenotypes were instead caused by a closely linked mutation. Based on a novel aspect of the sut1 mutant phenotype, secretion of a concentrated sugar solution from leaf hydathodes, we identified an additional mutant allele, sut1-m4. This confirms that the mutation of SUT1 is responsible for the impairment in phloem loading. In addition, the sut1-m4 mutant does not accumulate transcripts, supporting the findings reported previously that the original mutant allele is also a null mutation. Collectively, these data demonstrate that ZmSUT1 functions to phloem load sucrose in maize leaves.

Key words: carbohydrate partitioning, guttation, hydathode, maize, phloem loading, sucrose transporter1, sut1-m4

Introduction

Most plant species translocate sucrose as the reduced form of carbon from source leaves to nonphotosynthetic sink tissues.1,2 In apoplastic phloem loading species, sucrose transporters (SUTs) import sucrose from the apoplast into the companion cells and/or sieve elements.3–5 In dicot plants, genetic and biochemical evidence has shown that SUTs function to phloem load sucrose in leaves.6–10 However, it was unclear which SUTs perform this role within monocots. We recently obtained genetic evidence suggesting that maize SUT1 functions in phloem loading in leaves.11

Using reverse genetics, we obtained a Mutator (Mu) transposable element insertion into the 5′ UTR of the SUT1 gene (referred to as sut1-m1).11 Plants homozygous for the sut1-m1 mutation have greatly diminished growth, altered biomass partitioning, reduced fertility, hyperaccumulate carbohydrates within mature leaves, and fail to load 14C-labeled sucrose into the veins.11 Here we describe further aspects of the mutant phenotype directly related to the inability to phloem load sucrose in source leaves, and we report the characterization of additional mutant alleles, which confirm the phenotypes result from the loss of SUT1 function.

Inhibition of Phloem Loading Leads to Secretion of Soluble Sugars from Maize Leaves

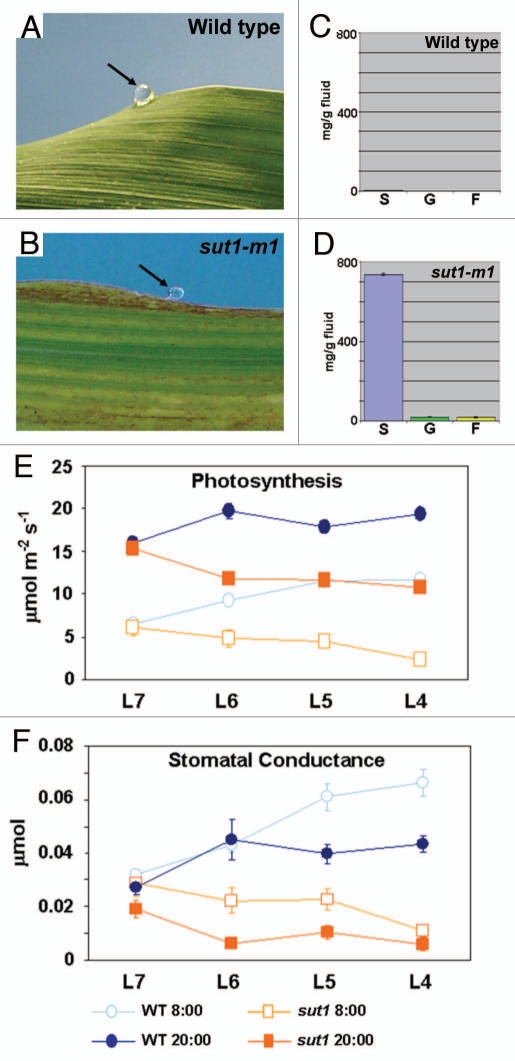

Under normal growing conditions, wild-type maize plants secrete droplets of water from specialized structures, called hydathodes,12 when water potential in roots is greater than that in leaves (Fig. 1A). This process is known as guttation.13–15 Typically, guttation fluids contain only trace amounts of reduced carbon compounds and rapidly evaporate from the leaf surface shortly after dawn. Interestingly, we observed that sut1-m1 mutant leaves retained guttation fluids on their surface (Fig. 1B). This was also seen in wild-type plants that had been cold-girdled,11 a process that results in inhibition of phloem transport (data not shown). This novel phenotype was not observed for the many other maize leaf carbohydrate hyperaccumulation mutants.16–25 Guttation fluid was collected from untreated wild-type sibling and sut1-m1 mutant plants and assayed for soluble sugar concentrations. Wild-type guttation fluid contained very low sugar concentrations, whereas guttation fluid from sut1-m1 leaves contained over 700 mg of sucrose/g of fluid and 20–25 mg each of glucose and fructose/g of fluid (Fig. 1C and D). We infer that both the loss of SUT1 function and the inhibition of phloem transport by girdling result in the build-up of apoplastic sucrose that subsequently migrates into the xylem transpiration stream. The presence of the relatively equal amounts of glucose and fructose in the guttation fluid is likely explained by cell wall invertases that cleave sucrose into the two monosaccharides.26

Figure 1.

Additional phenotypes of sut1 mutant plants. (A and B) Photographs of guttation fluid on leaf margins. (C and D) Graphs of quantifications of sucrose (S), glucose (G) and fructose (F) in guttation fluid. (A and C) Wild type. (B and D) sut1-m1 mutant. (E and F) Measurements of photosynthesis (E) and stomatal conductance (F) rates of wild-type and sut1-m1 mutant leaves. L7-L4 indicate leaves seven through four on three-week-old plants. Circles represent wild type and squares represent sut1 mutants. Open symbols indicate data collected at 8 AM and filled symbols indicate data collected at 8 PM (described in ref. 11).

Accumulation of Carbohydrates in sut1 Mutant Leaves is Associated with Decreased Photosynthetic and Stomatal Conductance Rates

High levels of photoassimilates are known to feedback and negatively regulate photosynthesis.27,28 In sut1-m1 mutants, photosynthetic and stomatal conductance rates are comparable to wild-type plants only in leaves emerging from the whorl (leaf 7 in Fig. 1E and F), which are in the process of transitioning to source tissue.11 Once leaves become sources, photosynthesis and stomatal conductance rates drastically decline in the sut1-m1 mutant relative to wild type (leaves 4–6 in Fig. 1E and F), presumably due to the excess accumulation of carbohydrates downregulating photosynthesis. However, even with greatly elevated carbohydrate levels, sut1 mutant leaves perform limited photosynthesis and gas exchange.

Phenotypes Observed in the sut1 Mutant Plants are Representative of Null Mutations in the SUT1 Gene

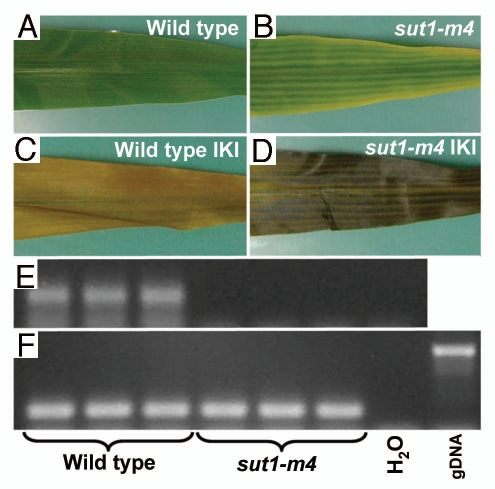

Based on the novel phenotype of the concentrated sucrose solution being secreted from leaf margins (Fig. 1B), an additional mutant allele of ZmSUT1 (sut1-m4) was independently isolated. The sut1-m4 allele was recovered from a Ds transposable element remobilization screen in the W22 inbred background. The new mutant had an identical phenotype to that reported for the sut1-m1 mutant, including leaf chlorosis and carbohydrate hyperaccumulation (Fig. 2A–D). PCR and DNA sequence analysis revealed that the Ds transposon inserted into the 5′ UTR of ZmSUT1, 11 basepairs downstream of the Mu insertion site in the sut1-m1 allele.11 By RT-PCR analyses on RNA isolated from mature leaves of sut1-m4 plants, no SUT1 RNA was detected, indicating that the sut1-m4 allele is an RNA null (Fig. 2E and F). These data are in agreement with both the sut1-m1 and sut1-m4 transposable element insertion alleles being nulls. Furthermore, these data demonstrate that the loss of SUT1 function is responsible for the phenotypes observed, and that SUT1 functions to load sucrose into the phloem in maize leaves. Finally, we note that two other SUT1 Ds insertion alleles are available (www.plantgdb.org/prj/AcDsTagging/), one located in the promoter that confers no obvious phenotype [sut1-m2, #I.S06.0327_JSR05], and a second in the 5′ UTR 66 basepairs downstream of the Mu insertion in the -m1 allele, which has an identical mutant phenotype to the sut1-m1 and sut1-m4 plants [sut1-m3, #I.S06.1500_JSR05].

Figure 2.

sut1-m4 mutant leaves contain excess starch and do not accumulate transcripts. (A and B) Photographs of leaves. (C and D) Same leaves cleared of photosynthetic pigments and starch (IKI) stained. (A and C) Wild type. (B and D) sut1-m4 mutant. (E and F) RT -PCR on three biological replicates isolated from wild-type and sut1-m4 mutant leaves. (E) RT-PCR with SUT1-specific primers. (F) RT-PCR with ubiquitin primers as a cDNA normalization control (described in ref. 11).

Implications and Future Work

Though debilitated, sut1 mutant plants are viable. This suggests that there may be partial genetic redundancy, and that one of the other six SUT genes in maize may be able to load sucrose into the phloem, albeit not as efficiently as SUT1. Alternatively, in the absence of SUT1 function, sucrose may enter the phloem via another route, such as symplastically.2,5,11 Plasmodesmata are present at all cellular interfaces between mesophyll cells and sieve elements, although their numbers were reported as “scarce” between vascular parenchyma cells and companion cells.29 A similar hypothesis was recently proposed for Arabidopsis thaliana plants mutated in the principal SUT responsible for phloem loading.9 Indeed, symplastic phloem loading of sucrose appears to be more widespread in plants than previously appreciated.1,2 Future work examining compensatory changes in the expression of SUT family members in maize sut1 mutants, and by analyzing double and higher order sut mutant combinations will address these possibilities.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sally Assmann for the use of the LICOR 6400 and the members of the Braun and McSteen labs for discussions of the data and comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Research Initiative of the United States Department of Agriculture Cooperative State Research, Education and Extension Service, grant number 2008-35304-04597 to D.M.B.

Abbreviations

- SUT

sucrose transporter

- Mu

mutator

- UTR

untranslated region

- Ds

dissociation

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/11575

References

- 1.Rennie EA, Turgeon R. A comprehensive picture of phloem loading strategies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:14162–14167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902279106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slewinski TL, Braun DM. Current perspectives on the regulation of whole-plant carbohydrate partitioning. Plant Sci. 2010;178:341–349. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lalonde S, Wipf D, Frommer WB. Transport mechanisms for organic forms of carbon and nitrogen between source and sink. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2004;55:341–372. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sauer N. Molecular physiology of higher plant sucrose transporters. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2309–2317. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun DM, Slewinski TL. Genetic control of carbon partitioning in grasses: Roles of Sucrose Transporters and Tie-dyed loci in phloem loading. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:71–81. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.129049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riesmeier JW, Willmitzer L, Frommer WB. Evidence for an essential role of the sucrose transporter in phloem loading and assimilate partitioning. EMBO J. 1994;13:1–7. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bürkle L, Hibberd JM, Quick WP, Kühn C, Hirner B, Frommer WB. The H+-sucrose cotransporter NtSUT1 is essential for sugar export from tobacco leaves. Plant Physiol. 1998;118:59–68. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gottwald JR, Krysan PJ, Young JC, Evert RF, Sussman MR. Genetic evidence for the in planta role of phloem-specific plasma membrane sucrose transporters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13979–13984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250473797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srivastava AC, Ganesan S, Ismail IO, Ayre BG. Functional characterization of the Arabidopsis thaliana AtSUC2 Suc/H+ symporter by tissue-specific complementation reveals an essential role in phloem loading but not in long-distance transport. Plant Physiol. 2008;147:200–211. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.124776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandran D, Reinders A, Ward JM. Substrate specificity of the Arabidopsis thaliana sucrose transporter AtSUC2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44320–44325. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308490200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slewinski TL, Meeley R, Braun DM. Sucrose transporter1 functions in phloem loading in maize leaves. J Exp Bot. 2009;60:881–892. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evert RF. Esau's Plant Anatomy: Meristems, Cells and Tissues of the Plant Body: Their Structure, Function and Development. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curtis LC. Deleterious effects of guttated fluids on foliage. Am J Bot. 1943;30:778–782. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenhill AW, Chibnall AC. The exudation of glutamine from perennial rye-grass. Biochem J. 1934;28:1422–1427. doi: 10.1042/bj0281422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pilot G, Stransky H, Bushey DF, Pratelli R, Ludewig U, Wingate VPM, et al. Overexpression of GLUTAMINE DUMPER1 leads to hypersecretion of glutamine from hydathodes of Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Cell. 2004;16:1827–1840. doi: 10.1105/tpc.021642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braun DM, Ma Y, Inada N, Muszynski MG, Baker RF. tie-dyed1 regulates carbohydrate accumulation in maize leaves. Plant Physiol. 2006;142:1511–1522. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.090381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker RF, Braun DM. tie-dyed1 functions non-cell autonomously to control carbohydrate accumulation in maize leaves. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:867–878. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.098814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baker RF, Braun DM. tie-dyed2 functions with tie-dyed1 to promote carbohydrate export from maize leaves. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:1085–1097. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.111476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blauth S, Yao Y, Klucinec J, Shannon J, Thompson D, Guilitinan M. Identification of Mutator insertional mutants of starch-branching enzyme 2a in corn. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:1396–1405. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.3.1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dinges JR, Colleoni C, James MG, Myers AM. Mutational analysis of the pullulanase-type debranching enzyme of maize indicates multiple functions in starch metabolism. Plant Cell. 2003;15:666–680. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma Y, Baker RF, Magallanes-Lundback M, DellaPenna D, Braun DM. Tie-dyed1 and Sucrose export defective1 act independently to promote carbohydrate export from maize leaves. Planta. 2008;227:527–538. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0636-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma Y, Slewinski TL, Baker RF, Braun DM. Tie-dyed1 encodes a novel, phloem-expressed transmembrane protein that functions in carbohydrate partitioning. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:181–194. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.130971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slewinski TL, Ma Y, Baker RF, Huang M, Meeley R, Braun DM. Determining the role of Tie-dyed1 in starch metabolism: Epistasis analysis with a maize ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase mutant lacking leaf starch. J Hered. 2008;99:661–666. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esn062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Russin WA, Evert RF, Vanderveer PJ, Sharkey TD, Briggs SP. Modification of a specific class of plasmodesmata and loss of sucrose export ability in the sucrose export defective1 maize mutant. Plant Cell. 1996;8:645–658. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.4.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slewinski TL, Braun DM. The Psychedelic genes of maize redundantly promote carbohydrate export from leaves. Genetics. 2010 doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.113357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koch K. Sucrose metabolism: regulatory mechanisms and pivotal roles in sugar sensing and plant development. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2004;7:235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheen J. Metabolic repression of transcription in higher plants. Plant Cell. 1990;2:1027–1038. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.10.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheen J. Feedback-control of gene-expression. Photosynth Res. 1994;39:427–438. doi: 10.1007/BF00014596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evert RF, Eschrich W, Heyser W. Leaf structure in relation to solute transport and phloem loading in Zea mays L. Planta. 1978;138:279–294. doi: 10.1007/BF00386823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]