Inhibition of Cdc42 by dRich induces postsynaptic release of the BMP ligand Glass bottom boat.

Abstract

Retrograde bone morphogenetic protein signaling mediated by the Glass bottom boat (Gbb) ligand modulates structural and functional synaptogenesis at the Drosophila melanogaster neuromuscular junction. However, the molecular mechanisms regulating postsynaptic Gbb release are poorly understood. In this study, we show that Drosophila Rich (dRich), a conserved Cdc42-selective guanosine triphosphatase–activating protein (GAP), inhibits the Cdc42–Wsp pathway to stimulate postsynaptic Gbb release. Loss of dRich causes synaptic undergrowth and strongly impairs neurotransmitter release. These presynaptic defects are rescued by targeted postsynaptic expression of wild-type dRich but not a GAP-deficient mutant. dRich inhibits the postsynaptic localization of the Cdc42 effector Wsp (Drosophila orthologue of mammalian Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein, WASp), and manifestation of synaptogenesis defects in drich mutants requires Wsp signaling. In addition, dRich regulates postsynaptic organization independently of Cdc42. Importantly, dRich increases Gbb release and elevates presynaptic phosphorylated Mad levels. We propose that dRich coordinates the Gbb-dependent modulation of synaptic growth and function with postsynaptic development.

Introduction

Reliable and effective communication between neurons and their postsynaptic targets across the synaptic cleft is critical for the formation, growth, and plasticity of neuronal synapses. One mode of this transsynaptic communication is retrograde signaling, in which target cells provide molecular signals to influence presynaptic neurons (Tao and Poo, 2001; Marqués and Zhang, 2006). In Drosophila melanogaster, Glass bottom boat (Gbb), a bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), acts as a critical retrograde signal that promotes synaptic growth and neurotransmitter release at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ; Haghighi et al., 2003; McCabe et al., 2003; Goold and Davis, 2007). Genetic experiments have shown that the retrograde Gbb signal is sensed by a presynaptic receptor complex formed by the type II BMP receptor wishful thinking (Wit) and either of two type I BMP receptors, thick veins (Tkv) and saxophone (Sax; Aberle et al., 2002; Marqués et al., 2002; Rawson et al., 2003; McCabe et al., 2004; O’Connor-Giles et al., 2008). Upon Gbb binding, the receptor phosphorylates the transcription factor Mothers against decapentaplegic (Mad). Phosphorylated Mad (P-Mad) associates with the co-Smad Medea (Med) and enters the nucleus to regulate transcription of target genes (Keshishian and Kim, 2004).

Retrograde BMP signaling is instructive for presynaptic growth. For example, mutations in dad, an inhibitory Smad gene, cause synaptic overgrowth (Sweeney and Davis, 2002; O’Connor-Giles et al., 2008), whereas mutations disrupting BMP signaling have the opposite effect (Marqués et al., 2002; McCabe et al., 2004; Rawson et al., 2003; O’Connor-Giles et al., 2008). Moreover, presynaptic P-Mad levels closely correlate with the extent of synaptic growth (O’Connor-Giles et al., 2008). Spichthyin and Nervous Wreck inhibit BMP signaling through endocytic regulation of BMP receptors in presynaptic terminals (Wang et al., 2007; O’Connor-Giles et al., 2008). Recently, we showed that Wsp, the Drosophila orthologue of mammalian Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASp), functions postsynaptically to inhibit the secretion of Gbb from muscle (Nahm et al., 2010). Thus, retrograde Gbb signaling is negatively regulated at multiple levels to limit synaptic growth. A key question is whether negative Gbb signaling regulation can be relieved to promote synaptic growth. As the NMJ grows continuously during larval development, a primary challenge in muscle is to appropriately regulate the subsynaptic reticulum (SSR; Guan et al., 1996) and postsynaptic glutamate receptor (GluR) domains with developmental changes in GluR composition and abundance (Schmid et al., 2008). However, little is known about mechanisms that couple postsynaptic assembly to the Gbb-dependent regulation of the presynaptic nerve terminal.

In mammals, Rich-1 (also called Nadrin) was identified as a neuron-specific GTPase-activating protein (GAP) that is required for Ca2+-dependent exocytosis (Harada et al., 2000). In addition to its RhoGAP domain, Rich-1 has an N-terminal BIN/amphiphysin/Rvs (BAR) domain, which is capable of binding to membrane lipids and inducing tubulation of liposomes (Richnau et al., 2004), and a C-terminal proline-rich domain, which strongly interacts with the SH3 domains of other BAR domain proteins, including Cdc42-interacting protein 4 (CIP4), syndapin, and amphiphysin II (Richnau and Aspenström, 2001; Richnau et al., 2004). Rich-1 associates with Pals1- and Patj-containing polarity complexes at tight junctions through interactions with angiomotin and maintains tight junction integrity by regulating Cdc42 activity (Wells et al., 2006). Based on Rich-1 interactions with endocytic adaptors CIN85 and CD2AP and its partial colocalization with the early endosome protein EEA1, it has been proposed that Rich-1 regulation of Cdc42 activity may be critical for proper endocytic trafficking of tight junction polarity proteins (Wells et al., 2006). However, the roles for Rich-1 in endocytosis and exocytosis have not been demonstrated at the organism level.

In this study, we describe synaptic functions of the single Drosophila orthologue of Rich-1 (Drosophila Rich [dRich]). We find that dRich acts postsynaptically to promote presynaptic growth and function at the NMJ. dRich drives transsynaptic effects on neurotransmitter release and presynaptic ultrastructure. Our biochemical and genetic data suggest that this retrograde regulatory role is mediated via inhibition of a Cdc42 to Wsp pathway, which inhibits postsynaptic Gbb secretion (Nahm et al., 2010). In addition, we show that dRich controls postsynaptic SSR structure, GluR subunit composition, and muscular growth through a Cdc42-independent pathway. Collectively, our data establish regulatory roles for dRich during synapse development and provide a better understanding of how modifications of pre- and postsynaptic terminals are coordinately regulated during synaptic maturation.

Results

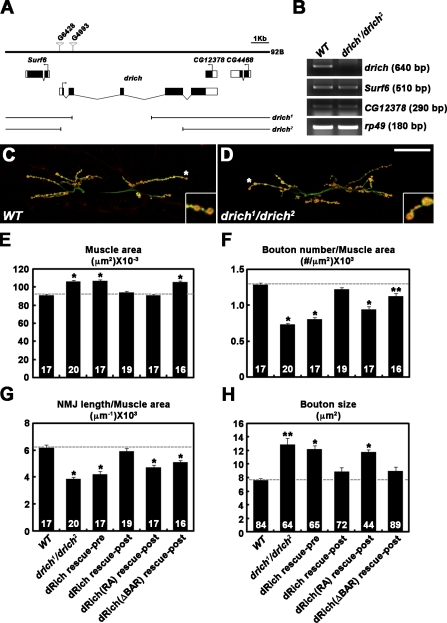

Postsynaptic dRich promotes NMJ expansion and restrains muscle growth

We performed an unbiased, forward genetic screen for novel mutations that affect synaptic morphology at the Drosophila NMJ. This screen was based on immunohistochemical inspection of the NMJ using an antibody against the axonal membrane marker HRP (Jan and Jan, 1982). Screening through 1,500 independent lines from the GenExel collection of EP-induced mutations (Lee et al., 2005), we identified two insertions, G6428 and G4993, that reside in the predicted gene RhoGAP92B (CG4755; Fig. 1 A). Both mutants showed simplified NMJ morphology compared with the wild-type control (w1118). A database search revealed that RhoGAP92B encodes the orthologue of mammalian Rich proteins. Therefore, we named the gene drich. To establish unambiguous null alleles of drich, we imprecisely excised the G4993 and G6428 insertions (Fig. 1 A). The drich1 allele, derived from G4993, has a 4,337-bp deletion (474–4,810 from the predicted translation start site), and the drich2 allele, derived from G6428, has a larger deletion (−129 to 6,550). No drich transcript was detected in drich1/drich2 third instar larvae by RT-PCR, whereas the neighboring genes Surf6 and CG12378 were normally expressed in these mutants (Fig. 1 B). Homozygotes and transheterozygotes of drich1 and drich2 were viable and displayed no obvious defects in pathfinding of motor axons.

Figure 1.

dRich required postsynaptically for presynaptic growth. (A) Genomic organization of drich/RhoGAP92B locus. The exon–intron organization of drich and neighboring genes Surf6 and CG12378. Untranslated regions are indicated by white boxes and translated regions by black boxes. The P-element insertions G4993 and G6428 were imprecisely excised to generate drich1 and drich2, respectively. (B) RNA of drich, Surf6, and CG12378 analyzed by RT-PCR in third instar wild-type (WT; w1118) and drich1/drich2 larvae. rp49 is used as a loading control. (C and D) Confocal images of NMJ 6/7 doubly labeled with anti-HRP and anti–cysteine string protein antibodies shown for wild type (C) and drich1/drich2 (D). Insets show magnified views of terminal boutons marked with asterisks. Bar, 50 µm. (E–H) Quantification of the combined surface area of muscles 6 and 7 (E), bouton number (F), and NMJ length (G) normalized to muscle area and mean size of type-Ib boutons (H) at NMJ 6/7 in the following genotypes: wild type, drich1/drich2, C155-GAL4/+; drich2/UAS-drich,drich1 (dRich rescue-pre), BG57-GAL4,drich2/UAS-drich,drich1 (dRich rescue-post), BG57-GAL4,drich2/UAS-drich-R287A,drich1 (dRich[RA] rescue-post), and BG57-GAL4,drich2/UAS-drichΔBAR-GFP,drich1 (dRich[ΔBAR] rescue-post). The number of NMJs or type-Ib boutons quantified for each genotype is indicated inside the bars. Statistically significant differences versus wild type are indicated (*, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01). Error bars indicate mean ± SEM.

To quantify the synaptic undergrowth phenotype of drich deletion mutants (Fig. 1, C and D), we measured synaptic terminal length, bouton number, and bouton size on third instar muscles 6 and 7 of abdominal segment 2. Transheterozygous drich1/drich2 mutants displayed a mild 17% increase in the muscle 6/7 area (Fig. 1 E). With normalization to muscle area, mutations in drich caused a 43% reduction in bouton number and 37% reduction in NMJ length (Fig. 1, F and G; and Fig. S1, A and B). At the same time, mean bouton size was increased by 69% in drich1/drich2 compared with wild type (Fig. 1 H). The synaptic undergrowth and muscle overgrowth phenotypes of drich mutants were highly penetrant, affecting other type I NMJs (Fig. S1, C–G). Muscle area and NMJ bouton number are normal in drich1/drich2 first instar larvae at 1 h after hatching (Fig. S1, H–L), indicating that drich function is specifically required for the proper growth of muscles and synapses during larval development.

To determine where drich function is required, we performed genetic rescue experiments using the UAS/GAL4 system (Brand and Perrimon, 1993). When the muscle-specific BG57-GAL4 driver was used to express UAS-drich in drich1/drich2 mutants, both muscle and NMJ growth defects were near completely rescued (Fig. 1, E–H). In contrast, the same UAS-drich transgene showed no significant rescue activity when driven by the neuronal C155-GAL4 driver (Fig. 1, E–H), suggesting that the synaptic undergrowth phenotype in drich mutants is caused by loss of postsynaptic drich function.

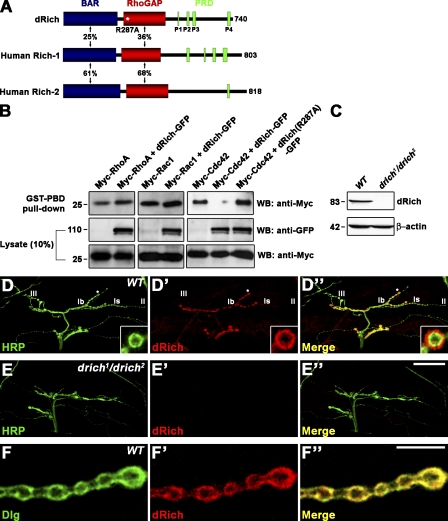

Requirements of dRich GAP and BAR domains

The dRich protein displays highly similar domain organization to mammalian Rich-1 and Rich-2 proteins (Fig. 2 A). All proteins consist of an N-terminal BAR domain that is highly homologous to those of endophilin and amphiphysin (Richnau et al., 2004), a central RhoGAP domain, and a C-terminal proline-rich domain. Overall, dRich is ∼24–25% identical to human Rich-1 and Rich-2 at the amino acid level.

Figure 2.

dRich is a Cdc42-selective GAP localized postsynaptically at the NMJ. (A) Schematic domain structures of dRich, human Rich-1, and human Rich-2. The percent amino acid identity is indicated for each domain. The substitution mutation R287A in the RhoGAP domain of dRich is marked by the white asterisk. (B) dRich inactivates Cdc42 but not RhoA or Rac1 in cultured cells. Plasmids encoding Myc-tagged RhoA, Rac1, or Cdc42 were transiently transfected alone or in combination with a plasmid encoding dRich-GFP or dRich-R287A-GFP into S2R+ cells as indicated. After transfection, GTP-loaded RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42 were precipitated from cell lysates with GST-Rhotekin-PBD (for RhoA) and GST-PAK1-PBD (for Rac1 and Cdc42). The amounts of active, GTP-loaded GTPases in precipitates were determined by Western blotting (WB) using anti-Myc (top). Levels of GFP and Myc fusion proteins in the cell lysates were determined by Western blotting using anti-GFP (middle) and anti-Myc (bottom) antibodies, respectively. Markers are given in kilodaltons. (C) Western blotting of wild-type and drich1/drich2 larval extracts using anti-dRich. The same blot was reprobed for β-actin as a loading control. (D–E″) Confocal images of NMJ 12/13 stained with anti-HRP (green) and anti-dRich (red) in wild-type (D) and drich1/drich2 (E) third instar larvae. (D–D”) Insets show higher magnification images of a single Ib bouton. (F–F″) A confocal plane of wild-type NMJ 12/13 branch stained with anti-Dlg (green) and anti-dRich (red) antibodies. Bars: (E″) 50 µm; (F″) 10 µm.

To determine the membrane-deforming activity of dRich, we transiently expressed a GFP fusion of full-length dRich (dRich-GFP) in COS-7 cells. The GFP signal localized at tubular structures that also labeled with extracellularly applied CM-DiI (chloromethylbenzamido), a tracer of the plasma membrane (Fig. S2 A). Expression of a 243–amino acid fragment of dRich covering the BAR domain (dRich-BAR-GFP) induced tubulation similar to that of full-length dRich-GFP (Fig. S2 B). In contrast, expression of the dRich-GFP protein lacking the first 236 amino acids (dRichΔBAR-GFP) did not induce tubulation (Fig. S2 C). Thus, the BAR domain of dRich appears to have membrane-deforming activity. To confirm dRich GAP activity and substrate specificity, we expressed GFP-tagged dRich with Myc epitope–tagged RhoA, Rac1, or Cdc42 in Drosophila S2R+ cells (Fig. 2 B). We assayed GTPase activity in cell lysates with p21-binding domain (PBD) pull-down (see Materials and methods). dRich reduced Cdc42-GTP by ∼77% but did not significantly alter levels of RhoA-GTP and Rac1-GTP (Fig. 2 B). In addition, the R287A mutation in dRich (dRich-R287A) completely impaired GAP activity toward Cdc42 (Fig. 2 B). Thus, dRich acts as a Cdc42-specific GAP in cultured cells.

To determine whether dRich BAR and GAP domains are required for proper retrograde regulation of synaptic growth, we generated UAS transgenes of dRich-R287A and dRichΔBAR-GFP and tested their ability to rescue drich phenotypes. Postsynaptic expression of UAS-drich-R287A using BG57-GAL4 rescued the increase in muscle size but not defects in NMJ length, bouton number, and bouton size (Fig. 1, E–H; and Fig. S1, A and B). In contrast, postsynaptic expression of UAS-dRichΔBAR-GFP in drich1/drich2 mutants completely rescued defects in NMJ length, bouton number, and bouton size but failed to rescue the increase in muscle area (Fig. 1, E and H; and Fig. S1, A and B). Normalized NMJ length and bouton number were still defective in these animals because of muscle overgrowth (Fig. 1, F and G). The dRich variants were expressed at levels comparable with those of wild-type dRich (Fig. S3, A–E). Thus, the synaptic and muscle functions of dRich have different domain requirements.

dRich is enriched in the postsynaptic domain and inhibits Wsp localization

To further characterize dRich, we generated an antibody against an N-terminal region (amino acids 1–255). On Western blots of wild-type third instar larval extracts, this antibody recognized a band of ∼83 kD, the expected size for dRich, which was not detected in extracts from drich1/drich2 mutants (Fig. 2 C). Double staining of wild-type animals with HRP antibody revealed that dRich is highly enriched around type I boutons (Fig. 2, D–D″). Only a small portion of dRich immunoreactivity was observed within synaptic boutons. However, the protein was not detectable at type II/III boutons that lack the SSR. dRich signal was dramatically reduced at drich1/drich2 mutant NMJs (Fig. 2 E), confirming the specificity of the dRich staining. dRich highly overlaps with the postsynaptic marker Discs large (Dlg; Fig. 2 F), suggesting that dRich is a new postsynaptic component.

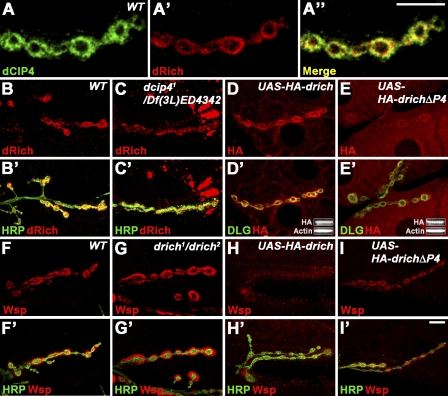

Mammalian Rich-1 binds the SH3 domain of CIP4 via its second proline-rich motif (P2; Richnau and Aspenström, 2001). Therefore, we assessed the interaction of dRich with Drosophila CIP4 (dCIP4). First, GST pull-down assays revealed that dRich interacts with the SH3 domain of dCIP4 via the fourth proline-rich motif (P4; Fig. S2, D and E). Second, dRich–dCIP4 interaction was confirmed in S2R+ cells by coimmunoprecipitation experiments (Fig. S2 F). Finally, we found strong colocalization between dCIP4 and dRich in the postsynaptic region of type I boutons (Fig. 3 A).

Figure 3.

Regulation of the postsynaptic localization of dRich and Wsp. (A–A″) A single confocal section of a wild-type (WT) NMJ 6/7 branch stained with anti-dCIP4 (green) and anti-dRich (red). (B–C′) Confocal images of wild-type (B) and dcip41/Df(3L)ED4342 mutant (C) third instar larval NMJ 6/7 stained with anti-HRP (green) and anti-dRich (red). (D–E′) Confocal images of NMJ 6/7 stained with anti-Dlg (green) and anti-HA (red) in wild-type third instar larvae with postsynaptic expression of HA-dRich (D) or HA-dRichΔP4 (E). (D’ and E’) Insets show Western blot analysis of muscle extracts using anti-HA and anti–β-actin antibodies. (F–G′) Confocal images of NMJ 6/7 stained with anti-HRP (green) and anti-Wsp (red) in wild type (F) and drich1/drich2 mutant (G). (H–I′) Confocal images of NMJ 6/7 stained with anti-HRP (green) and anti-Wsp (red) in wild type with postsynaptic expression of HA-dRich (H) or HA-dRichΔP4 (I). Bars, 10 µm.

To investigate whether dCIP4 is required for synaptic localization of dRich, we examined dRich immunoreactivity in the dcip4-null dcip41/Df(3L)ED4342 (Nahm et al., 2010). We found that there was a strong decrease in postsynaptic dRich localization and a corresponding appearance of extrasynaptic dRich aggregates (Fig. 3, compare B and C), suggesting that dCIP4 function is critical for efficient postsynaptic localization of dRich. In contrast, the distribution or abundance of synaptic dCIP4 was not affected in drich1/drich2 animals (unpublished data). To further test whether dRich–dCIP4 interaction is necessary for efficient, postsynaptic localization of dRich, we overexpressed both full-length HA-tagged dRich (HA-dRich) and a mutant deleting the dCIP4-binding P4 motif (dRichΔP4) in muscle. Like endogenous dRich, HA-dRich was efficiently localized to the postsynaptic region, whereas HA-dRichΔP4 was partially delocalized (Fig. 3, D and E; and Fig. S4 A). Expression levels of HA-dRich and HA-dRichΔP4 were comparable (Fig. 3, D′ and E′, insets), suggesting that dRich is postsynaptically localized via its interaction with dCIP4.

The SH3 domain of dCIP4 also mediates interaction with Wsp (Fricke et al., 2009). We therefore hypothesized that dRich might inhibit the postsynaptic localization of Wsp. In testing this possibility, we observed a twofold increase in postsynaptic Wsp in drich1/drich2 mutants compared with wild type (Fig. 3, F and G; and Fig. S4 B). Postsynaptic overexpression of HA-dRich and dRichΔBAR-GFP led to a substantially decreased expression of Wsp (Fig. 3 H and Fig. S4 B), whereas the HA-dRichΔP4 mutant had no effect on postsynaptic Wsp levels (Fig. 3 I and Fig. S4 B). Thus, a dRich–dCIP4 interaction via the dRich P4 motif inhibits postsynaptic localization of Wsp.

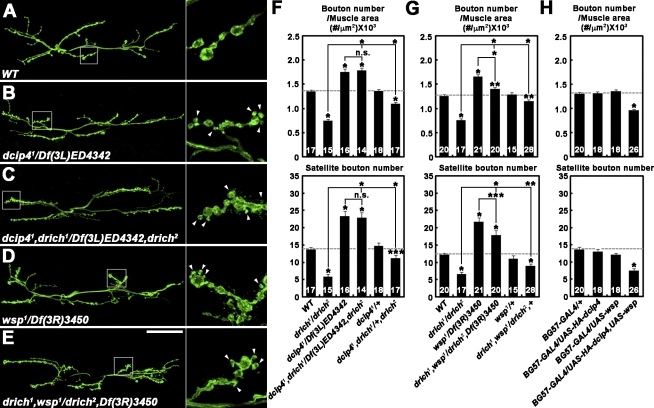

dRich antagonizes the dCIP4–Wsp pathway during synaptic growth

The aforementioned result and demonstrated GAP activity of dRich strongly suggest that dRich may regulate synaptic growth by antagonizing the dCIP4–Wsp pathway. To test this model, we examined genetic interactions between drich, dcip4, and wsp. Compared with wild-type controls, overall bouton number and satellite bouton formation in dcip4 mutants were significantly increased (Fig. 4, A, B, and F). These parameters of synaptic growth in drich; dcip4 double mutants were not significantly different from dcip4 single mutants (Fig. 4, B, C, and F). Moreover, synaptic undergrowth in drich mutants was significantly suppressed by removing one copy of dcip4, whereas heterozygosity for dcip4 alone did not cause any significant defects (Fig. 4 F). A similar genetic interaction was observed between drich and wsp (Fig. 4, D, E, and G). However, the synaptic morphology of drich; wsp double mutants was less severely affected than wsp single mutants (Fig. 4 G), perhaps reflecting a presynaptic role of Wsp in restraining synaptic growth (Coyle et al., 2004). Collectively, our genetic data suggest that dRich promotes synaptic growth by antagonizing the dCIP4–Wsp pathway. If this model is correct, postsynaptic overexpression of dCP4/Wsp should cause synaptic undergrowth in a wild-type background. In fact, cooverexpression of dCIP4 and Wsp in muscles reduced synaptic growth (Fig. 4 H), supporting the antagonistic relationship. However, postsynaptic overexpression of dCIP4 or Wsp alone had no effect (Fig. 4 H), suggesting that they function together in the muscle to limit synaptic growth.

Figure 4.

Synaptic undergrowth in drich requires dCIP4/Wsp signaling. (A–G) dCIP4/Wsp signaling is necessary for synaptic undergrowth in drich. (A–E) Confocal images of NMJ 6/7 labeled with anti-HRP in wild type (WT; A), dcip41/Df(3L)ED4342 (B), dcip41,drich1/Df(3L)ED4342,drich2 (C), wsp1/Df(3R)3450 (D), and drich1,wsp1/drich2,Df(3R)3450 (E). (right) Insets show higher magnification views of NMJ terminals marked by boxes. Arrowheads indicate satellite boutons. Bar, 50 µm. (F and G) Quantification of total bouton number and satellite bouton number at NMJ 6/7. (H) Co-overexpression of dCIP4 and Wsp in wild type decreases synaptic growth. Total bouton number and satellite bouton number at NMJ 6/7 were quantified for the indicated genotypes. All comparisons are with wild type unless indicated (*, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.05). Error bars indicate mean ± SEM.

Given the antagonistic effect of dRich on the signaling cascade of Cdc42, dCIP4, and Wsp, we hypothesized that dRich may be required for normal regulation of postsynaptic filamentous actin (F-actin). To test this idea, we visualized F-actin using rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin. F-actin is enriched at the NMJ postsynaptic region of wild type (Fig. S5 A), as described previously (Coyle et al., 2004). In drich mutants, levels of postsynaptic F-actin were dramatically increased (>70%) compared with control (Fig. S5, A–C). This phenotype was rescued by targeted postsynaptic expression of wild-type dRich or dRichΔBAR but not by dRich-R287A (Fig. S5 C). We then examined the effect of dRich overexpression on postsynaptic F-actin. Levels of postsynaptic F-actin were reduced in larvae overexpressing either dRich or dRichΔBAR (Fig. S5 C). In contrast, the dRich-R287A mutant increased postsynaptic F-actin in a dominant-negative manner (Fig. S5 C). Collectively, our data suggest that the GAP activity of dRich is inversely correlated to levels of postsynaptic F-actin and support the antagonistic relationship of dRich with the dCIP4-Wsp pathway.

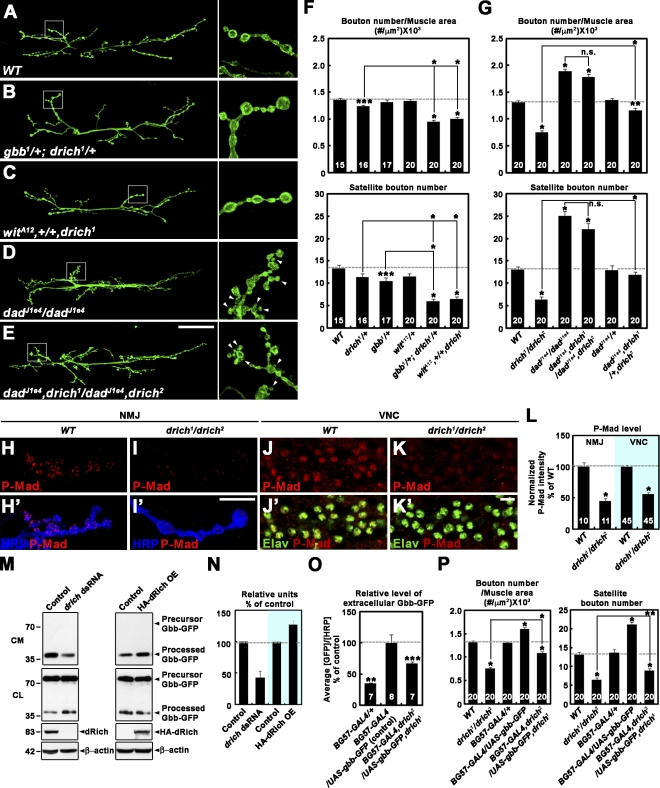

dRich positively regulates retrograde Gbb signaling

The Cdc42–dCIP4–Wsp pathway has recently been shown to restrain synaptic growth by inhibiting the secretion of Gbb at the Drosophila NMJ (Nahm et al., 2010). Therefore, we asked whether the retrograde role of dRich in synaptic growth regulation might be linked to Gbb. We first examined transheterozygous interactions between drich and mutants in either the retrograde signal (gbb) or its receptor (wit). When compared with wild-type controls, total bouton number and satellite bouton number in heterozygous drich1/+, gbb1/+, or witA12/+ larvae were normal or slightly decreased (Fig. 5 F). In striking contrast, there was a significant decrease in both parameters in transheterozygous gbb1/+; drich1/+ and witA12/+; drich1/+ animals compared with any of the single heterozygotes alone (Fig. 5, A–C and F), supporting a positive role of drich in gbb/wit-mediated synaptic growth. We then examined genetic interactions between drich and dad. In a control experiment, synaptic growth was significantly increased in dad single mutants compared with wild type (Fig. 5, A, D, and G), as described previously (O’Connor-Giles et al., 2008). In dad; drich double mutants, both parameters of synaptic growth were not significantly different from dad single mutants (Fig. 5, D, E, and G). In addition, removal of one copy of dad, which had no effect in wild type, significantly suppressed the synaptic undergrowth phenotype of drich single mutants (Fig. 5 G). These genetic interactions suggest that synaptic undergrowth in drich mutants requires regulation of BMP signaling by Dad, an inhibitory Smad. We therefore examined the effect of drich mutations on P-Mad levels at the NMJ and in the ventral nerve cord and found a significant reduction in drich1/drich2 compared with wild type (P < 0.001; Fig. 5, H–L). Together, these data suggest that dRich promotes synaptic growth by increasing the activity of retrograde Gbb signaling.

Figure 5.

dRich enhances retrograde Gbb signaling during synaptic growth. (A–G) drich interacts with gbb, wit, and dad at the NMJ. (A–E) Confocal images of NMJ 6/7 labeled with anti-HRP are shown for the indicated genotypes. (right) Insets show higher magnification views of NMJ terminals marked by boxes. Bar, 50 µm. (F and G) Quantification of total bouton number and satellite bouton number at NMJ 6/7 is shown for the indicated genotypes. (H–L) P-Mad levels are decreased in drich compared with wild-type (WT) larvae. (H–I′) Confocal images of NMJ 6/7 branches doubly labeled with anti–P-Mad (red) and anti-HRP (blue). (J–K′) Confocal images of ventral nerve cords (VNC) doubly labeled with anti–P-Mad (red) and anti-Elav (green), which marks the nuclei of neurons (Robinow and White, 1991). Bar, 10 µm. (L) Quantification of the ratio between mean P-Mad and HRP or Elav levels. The numbers of NMJ branches and nuclei analyzed are indicated inside the bars. Values represent percentages of wild type. (M and N) dRich promotes Gbb secretion from S2R+ cells. (M) Western blot of conditioned media (CM) and cell lysates (CL) from S2R+ cells transfected with a Gbb-GFP construct alone (control) or in combination with either drich dsRNA (left) or an HA-dRich construct (right, HA-dRich OE). Markers are given in kilodaltons. (N) Quantification of secreted Gbb-GFP levels normalized to total cell-associated Gbb-GFP by densitometric measurements. Values from four independent experiments are shown (control = 100%). (O) dRich promotes postsynaptic Gbb secretion at the larval NMJ. Fillets of BG57-GAL4/+, BG57-GAL4/UAS-gbb-GFP, and BG57-GAL4,drich2/UAS-gbb-GFP,drich1 third instar larvae were labeled for extracellular Gbb-GFP (Nahm et al., 2010). The ratios of mean extracellular GFP-GFP to HRP levels presented as percentages of BG57-GAL4/UAS-gbb-GFP. (P) Postsynaptic overexpression provides a partial rescue of the synaptic undergrowth phenotype of drich mutants. Total bouton number and satellite bouton number at NMJ 6/7 were quantified for the indicated genotypes. All comparisons are with wild type unless indicated (*, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.05). Error bars indicate mean ± SEM.

In mammalian cells, Wasp signaling plays a critical role during exocytosis (Lanzetti, 2007). Therefore, we hypothesized that dRich might be involved in the regulation of Gbb secretion. To test this idea, we transiently transfected S2R+ cells with a Gbb-GFP construct and assayed whether knockdown or overexpression of dRich would affect secretion. The medium of untreated control cells contained only processed Gbb-GFP of the expected size (∼44 kD), whereas lysates of the same cells contained processed Gbb-GFP and its precursor (∼75 kD; Fig. 5 M; Nahm et al., 2010). Treatment of cells with drich dsRNA greatly reduced processed Gbb-GFP in the medium, whereas overexpression of wild-type dRich had the opposite effect (Fig. 5, M and N), demonstrating that the level dRich bidirectionally correlates with the level of Gbb secretion. To confirm dRich-mediated regulation of Gbb secretion at the NMJ, we examined how drich mutations affect the secretion of processed Gbb-GFP from the muscle. Under immunostaining conditions to detect only extracellular antigens (Strigini and Cohen, 2000), BG57-GAL4,drich2/UAS-gbb-GFP,drich1 displayed significantly decreased secreted signal compared with the BG57-GAL4/UAS-gbb-GFP control (P < 0.05; Fig. 5 O), supporting the positive role for dRich in postsynaptic Gbb secretion in retrograde signaling. NMJ bouton number and satellite bouton formation were significantly increased in BG57-GAL4/UAS-gbb-GFP compared with BG57-GAL4/+ larvae (Fig. 5 P), suggesting that Gbb-GFP produced in BG57-GAL4/UAS-gbb-GFP is biologically active. Importantly, overexpression of UAS-gbb-GFP in muscles partially rescued the synaptic undergrowth phenotype caused by drich mutations (Fig. 5 P). Thus, dRich appears to promote synaptic growth by stimulating postsynaptic Gbb release at the NMJ.

dRich organizes the postsynapse domain independently of Cdc42

The general NMJ synaptic organization of drich mutants was analyzed using an array of synaptic markers. The distribution and levels of presynaptic markers, including vesicle-associated cysteine string protein and the cell adhesion molecule fasciclin II appeared to be normal in drich1/drich2 mutants (unpublished data). In contrast, postsynaptic assembly was clearly perturbed. In wild type, the Dlg scaffold is homogeneously detected in a halolike postsynaptic region surrounding type I boutons (Fig. 6 A). In drich1/drich2 mutants, the Dlg-positive domain was clearly increased (Fig. 6 B). In addition, Dlg was absent from several focal areas within the postsynaptic region (Fig. 6 B, arrowheads). This phenotype was rescued by muscle expression of wild-type dRich (Fig. 6 C), demonstrating postsynaptic specificity for the phenotype. We observed a similar alteration in the postsynaptic distribution of α-spectrin (Fig. S5, D and E).

Figure 6.

Distribution of Dlg and GluRIIB is altered in drich mutants. (A–E′) Single confocal slices of NMJ 6/7 stained with anti-HRP (green) and anti-Dlg (red). (bottom) Insets show higher magnification views of the areas indicated by asterisks. The genotypes analyzed include wild type (WT; A), drich1/drich2 (B), BG57-GAL4, drich2/UAS-drich,drich1 (dRich rescue; C), BG57-GAL4,drich2/UAS-drich-R287A,drich1 (dRich[RA] rescue; D), and BG57-GAL4,drich2/UAS-drichΔBAR-GFP,drich1 (dRich[ΔBAR] rescue; E). Note that several focal areas in the NMJ postsynapse are frequently devoid of Dlg staining in drich mutant larvae (arrowheads). Bar, 10 µm. (F–H) The levels of GluRIIB are altered in drich mutant larvae. (F–G′) Confocal images of NMJ 6/7 in wild-type (F) and drich1/drich2 (G) larvae stained for anti-GluRIIB (red) and anti-HRP (green). Insets show Western blots of muscle lysates. Bar, 20 µm. (H) Quantification of staining intensities of GluRIIA, GluRIIB, and GluRIIC normalized to anti-HRP. (I–N) The distribution of GluRIIB is altered in drich mutant larvae. (I–L″) Confocal images of NMJ 6/7 in wild-type (I and K) and drich1/drich2 (J and L) larvae stained with anti-NC82 (green) and either anti-GluRIIB (red; I and J) or anti-GluRIIC (red; K and L). The intensity of GluRIIB staining in wild type was artificially increased. Bar, 10 µm. (M and N) The mean sizes of GluRIIB and GluRIIC clusters (M) and quantification of the ratio of GluRIIB or GluRIIC versus NC82 puncta (N) in wild type, drich1/drich2, BG57-GAL4,drich2/UAS-drich,drich1 (dRich rescue), BG57-GAL4,drich2/UAS-drich-R287A,drich1 (dRich[RA] rescue), and BG57-GAL4,drich2/UAS-drichΔBAR-GFP,drich1 (dRich[ΔBAR] rescue). Statistically significant differences versus wild type are indicated (*, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01). Error bars indicate mean ± SEM.

The postsynaptic domain organizes tetrameric GluRs composed of GluRIIC, -D, and -E and either GluRIIA or GluRIIB subunits (Petersen et al., 1997; DiAntonio et al., 1999; Marrus et al., 2004; Featherstone et al., 2005; Qin et al., 2005). Synaptic levels of GluRIIA and GluRIIC subunits were not significantly different between wild type and drich1/drich2 (P > 0.05; Fig. 6 H). However, synaptic GluRIIB levels were increased nearly twofold in drich1/drich2 mutants compared with controls (Fig. 6, F–H). Levels of GluRIIB expression in drich1/drich2 muscles were normal (Fig. 6, F′ and G′, insets), suggesting that the increase in synaptic GluRIIB levels results from changes in subcellular localization. This defect was completely rescued by muscle expression of wild-type dRich (Fig. 6 H).

We next examined the relative distribution between GluR domains and presynaptic active zones in drich1/drich2 mutants. We colabeled with antibodies against GluRIIB or GluRIIC in combination with anti-NC82 against Bruchpilot in the electron-dense specializations (T-bars) of active zones (Fouquet et al., 2009). The mean size of GluRIIB or GluRIIC clusters was not significantly different between drich and wild type (P > 0.43; Fig. 6 M), and the ratio between postsynaptic GluRIIC domains and presynaptic NC82 puncta did not significantly change (wild type, 0.88 ± 0.05; drich1/drich2, 0.99 ± 0.04; P = 0.12; Fig. 6, K, L, and N). However, drich mutants displayed a significant increase in the ratio between postsynaptic GluRIIB domains and presynaptic NC82 puncta (wild type, 1.04 ± 0.05; drich1/drich2, 1.33 ± 0.04; P < 0.01; Fig. 6, I, J, and N), indicating that some GluRIIB clusters in drich mutants are not juxtaposed to active zones. This defect was completely rescued by muscle expression of wild-type dRich (Fig. 6 N). Thus, postsynaptic dRich is required for the proper distribution of postsynaptic GluRIIB domains.

Next, we tested the ability of dRich-R287A and dRichΔBAR-GFP to rescue the Dlg and GluRIIB phenotypes in drich1/drich2 mutants. Postsynaptic expression of dRich-R287A completely rescued defects in the distribution of Dlg and GluRIIB (Fig. 6, D and N). In addition, GluRIIB synaptic abundance was also restored to the wild-type level (Fig. 6 H). In contrast, postsynaptic expression of dRichΔBAR-GFP failed to rescue any postsynaptic defects (Fig. 6, E, H, and N). Together, these data establish the involvement of the BAR but not GAP domain of dRich in postsynaptic organization and reveal that dRich roles regulating presynaptic growth and postsynaptic organization are separable.

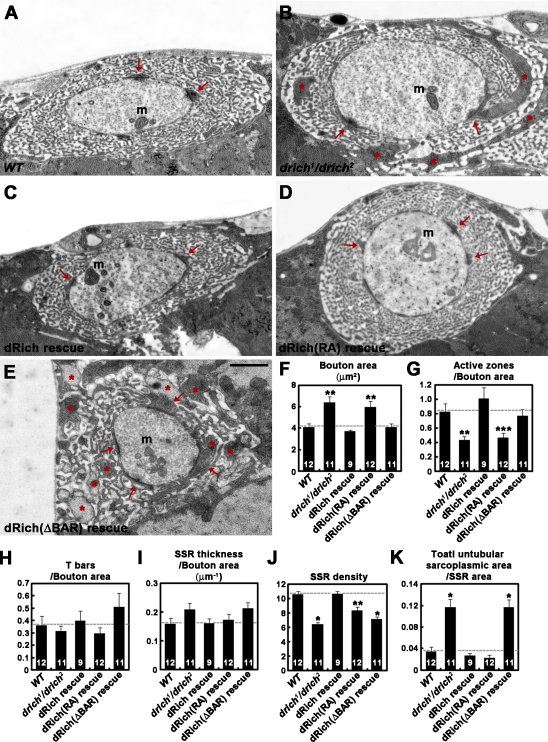

dRich regulates synaptic ultrastructure

To further investigate the role of dRich in regulating synaptic architecture, we examined the ultrastructure of NMJ 6/7 type Ib boutons by serial section transmission EM. Consistent with our light microscopic data, the cross-sectional bouton area was increased by 51% in drich compared with wild type (wild type, 4.13 ± 0.32 µm2; drich1/drich2, 6.22 ± 0.55 µm2; P < 0.01; Fig. 7, A, B, and F). In addition, the number of active zones normalized by the cross-sectional bouton area was significantly reduced by ∼50% in mutants (wild type, 0.83 ± 0.11 µm2; drich1/drich2, 0.45 ± 0.05 µm2; P < 0.01; Fig. 7 G). However, the number of active zone T-bars normalized by the cross-sectional bouton area was not significantly altered in drich1/drich2 mutants (Fig. 7 H). Likewise, the mean size and density of synaptic vesicles were not detectably changed (unpublished data).

Figure 7.

Ultrastructural analysis of drich mutant synapses. (A–E) Transmission electron micrographs of cross-sectioned type I boutons in wild type (WT; A), drich1/drich2 (B), BG57-GAL4,drich2/UAS-drich,drich1 (dRich rescue; C), BG57-GAL4,drich2/UAS-drich-R287A,drich1 (dRich[RA] rescue; D), and BG57-GAL4,drich2/UAS-drichΔBAR-GFP,drich1 (dRich[ΔBAR] rescue; E). Postsynaptic pockets and untubular sarcoplasmic area in the SSR are indicated by arrows and asterisks, respectively. m, mitochondria. Bar, 1 µm. (F–K) Quantification of the cross-sectional bouton area (F), number of active zones per bouton area (G), number of T-bars per bouton area (H), SSR thickness normalized by the cross-sectional bouton area (I), SSR density (J), and total untubular sarcoplasmic area normalized with bouton area (K). Statistically significant differences versus wild type are indicated (*, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.05). Error bars indicate mean ± SEM.

Postsynaptic SSR features were altered in drich1/drich2 mutants. In wild type, type I boutons are surrounded by an SSR consisting of an alternate tubular array of two compartments: (1) the electron-dense sarcoplasmic compartment and (2) the electron-light compartment representing SSR cisternae. Aside from the postsynaptic pockets that immediately face presynaptic active zones, the SSR contains few untubular sarcoplasmic patches in single EM sections (Fig. 7 A). In drich1/drich2 mutants, the SSR was more expanded and contained numerous untubular sarcoplasmic patches of large size (Fig. 7 B, asterisks). To quantify these changes, we measured SSR thickness, SSR density, and the ratio of the total untubular sarcoplasmic area to the cross-sectional SSR area. In drich mutants, SSR thickness normalized by the cross-sectional bouton area was normal (Fig. 7 I). However, the density of SSR membranes was 34% lower than control (wild type, 10.59 ± 0.43 µm−1; drich1/drich2, 7.02 ± 0.28 µm−1; P < 0.001; Fig. 7 J), showing that membrane layers are less compact. In addition, the ratio of untubular sarcoplasmic area to SSR cross-sectional area was increased by 175% in drich mutants (wild type, 0.04 ± 0.01; drich1/drich2, 0.11 ± 0.02; P < 0.001; Fig. 7 K).

Next, we tested UAS-drich, UAS-drich-R287A, and UAS-drichΔBAR-GFP transgenes for their ability to rescue the ultrastructural defects in drich. Muscle-specific expression of wild-type dRich fully rescued drich1/drich2 defects (Fig. 7, C, F, G, J, and K). Postsynaptic expression of dRich-R287A provided a partial or complete rescue of defects in SSR density and untubular sarcoplasmic area to SSR cross-sectional area ratio but not defects in bouton size or active zone number (Fig. 7, D, F, G, J, and K). In contrast, dRichΔBAR-GFP efficiently rescued defects in bouton size and active zone number but not defects in SSR density and SSR ratio (Fig. 7, E–G, J, and K). Thus, the GAP activity of dRich is required for normal presynaptic morphology, whereas the BAR domain of dRich is necessary for proper postsynaptic organization.

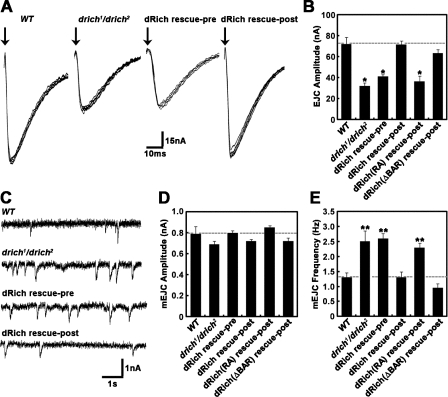

Postsynaptic dRich strongly facilitates synaptic transmission

To directly assess the functional consequence of drich mutations at the larval glutamatergic NMJ synapse, we recorded postsynaptic currents using the two-electrode voltage clamp (TEVC) recording configuration. At a basal stimulation frequency of 0.5 Hz in 0.5 mM extracellular Ca2+, the amplitude of excitatory junctional currents (EJCs) in drich mutants was reduced by ∼50% compared with wild-type controls (wild type, 72.2 ± 6.2 nA; drich1/drich2, 32.2 ± 3.1 nA; P < 0.001; Fig. 8, A and B). Neuronal expression of wild-type dRich in drich mutants failed to restore synaptic transmission (Fig. 8, A and B). In sharp contrast, targeted muscle expression of wild-type dRich in the null background completely restored synaptic transmission amplitude to wild-type levels (Fig. 8, A and B), indicating that dRich acts postsynaptically to strongly facilitate synaptic function. To determine the domain requirements of dRich for the facilitation of synaptic transmission, we expressed dRich-R287A or dRichΔBAR-GFP in the muscles of drich1/drich2 mutants and tested their ability to restore the reduction in EJC amplitude. We found that the defect in synaptic transmission amplitude was rescued by dRichΔBAR-GFP but not by dRich-R287A (Fig. 8 B), providing evidence that the Cdc42-selective GAP activity of dRich is critical for the retrograde transsynaptic regulation of synaptic function.

Figure 8.

Postsynaptic loss of dRich impairs NMJ synaptic transmission. (A) Representative TEVC (−60 mV) records from muscle 6 in segment A3 with 0.5 Hz nerve stimulation in 0.5 mM external Ca2+. EJC records are shown for wild-type (WT), drich1/drich2, C155-GAL4/+; drich2/UAS-drich,drich1 (dRich rescue-pre), and BG57-GAL4,drich2/UAS-drich,drich1 (dRich rescue-post) larvae. Arrows indicate time of nerve stimulation. (B) Quantified mean EJC amplitudes for all six genotypes, including BG57-GAL4,drich2/UAS-drich-R287A,drich1 (dRich[RA] rescue-post) and BG57-GAL4,drich2/UAS-drichΔBAR-GFP,drich1 (dRich[ΔBAR] rescue-post). Transmission is reduced >50% in drich mutants. The defect is completely rescued by postsynaptic but not presynaptic expression of wild-type dRich. The defect is similarly rescued by BAR domain–deleted dRich in the postsynaptic compartment but not by dRich lacking GAP domain function. (C) Representative mEJC events after nerve transection; continuous recording in 0.5 mM external Ca2+ in the same genotypes as in A. (D and E) Quantification of mean mEJC amplitude (D) and frequency (E). Sample size is at least six animals per genotype. Statistically significant differences versus wild type are indicated (*, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01). Error bars indicate mean ± SEM.

Either presynaptic or postsynaptic defects or both could potentially underlie impaired neurotransmission in drich mutants. One method to identify mechanistic defects is to assay spontaneous synaptic vesicle fusion, or miniature EJC (mEJC) events, occurring in the absence of evoked or endogenous action potentials (Trotta et al., 2004; Gatto and Broadie, 2008; Long et al., 2008). Representative mEJC records for wild-type and drich-null mutants are shown in Fig. 8 C. In drich mutants, mean mEJC amplitude was not altered compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 8 D), suggesting no defect in basal postsynaptic function in the absence of dRich. In contrast, there was a small but significant increase in mEJC frequency in drich1/drich2 compared with wild-type animals (wild type, 1.3 ± 0.2 Hz; drich1/drich2, 2.5 ± 0.4 Hz; P < 0.01; Fig. 8 E). Although this defect is presumably reflecting synaptic vesicle fusion probability and is therefore presynaptic, the defect could only be rescued with postsynaptic introduction of wild-type dRich (Fig. 8, C and E). In addition, postsynaptic expression of dRichΔBAR-GFP but not dRich-RA rescued the abnormality in mEJC frequency. Collectively, these data suggest that postsynaptic dRich inhibits Cdc42 signaling to exert a retrograde transsynaptic effect on the regulation of synaptic neurotransmitter release.

Discussion

A fundamental property of neuronal synapses is the ability to dynamically modulate both structure and function. Alterations of pre- and postsynaptic sides must occur in a coordinated fashion, demanding a tight network of transsynaptic signals. In this study, we demonstrate that dRich is an evolutionarily conserved postsynaptic RhoGAP that positively regulates presynaptic growth and neurotransmitter release by relieving Cdc42-mediated inhibition of postsynaptically secreted retrograde Gbb signal. We further show that dRich signaling regulates the elaboration of postsynaptic architecture and GluR composition via a Cdc42-independent pathway. These findings indicate that dRich function bifurcates to independently regulate Gbb-dependent presynaptic development and postsynaptic organization. Thus, dRich is an important new signaling component in synaptic mechanisms that coordinate pre- and postsynaptic modifications during development.

Postsynaptic dRich promotes Gbb-dependent presynaptic development

We previously proposed that dCIP4 regulation of Cdc42/Wsp/Arp2/3-induced actin polymerization restrains synaptic growth by inhibiting postsynaptic Gbb release (Nahm et al., 2010). Such a mechanism requires the means to finely tune levels of Gbb signaling. In this study, we provide multiple lines of evidence supporting the model that postsynaptic dRich regulates Gbb release primarily by inhibiting Cdc42/Wsp/Arp2/3-induced actin polymerization. First, the dRich GAP domain increases the intrinsic GTPase activity of Cdc42 in cultured cells, and this GAP activity is critical for promoting synaptic growth. Second, dRich binds to the SH3 domain of dCIP4, a Cdc42 effector that interacts with Wsp via the same SH3 domain (Leibfried et al., 2008; Fricke et al., 2009), and this interaction inhibits the postsynaptic localization of Wsp, which is normally recruited to the postsynaptic domain in a dCIP4-dependent manner (Nahm et al., 2010). Third, synaptic undergrowth in drich mutants requires dCIP4 and Wsp signaling, supporting the notion that dRich acts by negatively regulating the Cdc42–dCIP4–Wsp pathway. Fourth, postsynaptic F-actin is negatively regulated by dRich, supporting an inhibitory effect on Cdc42/Wsp/Arp2/3-induced actin polymerization. Fifth, genetic interactions between drich and gbb, wit, or dad mutants support a positive role for dRich in retrograde BMP signaling. Finally, levels of dRich are positively correlated to P-Mad levels in motor neurons and levels of Gbb secretion from cultured cells and at the NMJ synapse.

In the presynaptic compartment, drich mutants display additional abnormalities. The mutants show reduced active zone density, and this defect can be rescued only by postsynaptic dRich, indicating a retrograde signaling mechanism. A similar phenotype has been described for gbb and mutants of BMP signaling components, including wit, tkv, sax, mad, and med (Aberle et al., 2002; McCabe et al., 2003, 2004), suggesting that aberrant regulation of postsynaptic Gbb release underlies the ultrastructural defect in drich mutants. In support of this notion, postsynaptic expression of a GAP-deficient dRich does not rescue the reduction in active zone density. At the electrophysiological level, drich mutations cause reduced neurotransmitter release without any effect on mean quantal size. This defect can also be rescued only by postsynaptic dRich, not presynaptic expression, again indicating a retrograde signaling mechanism. A similar phenotype has been reported in gbb, wit, tkv, sax, and mad mutants (Marqués et al., 2002; McCabe et al., 2004), suggesting a common retrograde signaling pathway. At present, we do not know the basis underlying the increase in mEJC frequency in drich mutants. One possibility is that dRich-mediated inhibition of the postsynaptic Cdc42–Wsp pathway could equally regulate other retrograde signals that enhance synaptic vesicle fusion probability.

dRich regulates postsynaptic organization independently of Cdc42 signaling

Loss of dRich causes multiple defects in the molecular composition and organization of the postsynaptic domain. This requirement for dRich is within the muscle, with no requirement for transsynaptic signaling. Null drich mutants show altered distribution of Dlg and spectrin membrane scaffolds, and exhibit a less-compact SSR with numerous untubular sarcoplasmic patches. In addition, mutants display a small increase in GluRIIB postsynaptic abundance and supernumerary GluRIIB domains that do not oppose presynaptic active zones. These GluR domain changes do not produce any detectable alteration in mEJC amplitude, although functional properties of GluRIIA- and GluRIIB-containing receptors are different (Petersen et al., 1997; DiAntonio et al., 1999). All postsynaptic phenotypes are rescued by a GAP-deficient dRich, showing that dRich exerts its effect on postsynaptic assembly independently of Cdc42 via a completely different mechanism.

We envision two models for dRich regulation of postsynaptic architecture. One possibility is that the membrane tubulation activity of dRich might induce or stabilize infoldings of postsynaptic muscle membrane. In support, postsynaptic phenotypes of drich mutants are not rescued by postsynaptic expression of a dRich mutant lacking the BAR domain. In addition, several similar BAR domain proteins have been shown to play critical roles in regulating membrane morphogenesis. For example, dAmph organizes T-tubules in muscles and rhabdomere membrane in photoreceptors (Razzaq et al., 2001; Zelhof et al., 2001). More recently, syndapin has been shown to promote SSR expansion via its F-BAR domain (Kumar et al., 2009). An alternative possibility is that dRich acts by recruiting other postsynaptic components. For example, dRich colocalizes with Dig, which regulates SSR development (Budnik et al., 1996), and dRich lacking the BAR domain fails to rescue the null mutant defect in Dlg distribution. It is therefore plausible that membrane folding by the dRich BAR domain may allow for proper retention or targeting of Dlg to the postsynaptic domain. In addition, preliminary GST pull-down assays indicate that dRich interacts with syndapin via a proline-rich motif (unpublished data), suggesting that dRich may promote membrane tubulation by recruiting other BAR domain proteins. This possibility is supported by a recent finding that multiple BAR domain proteins can be involved in the generation of a single tubular structure (Frost et al., 2008). Further analysis of genetic and biochemical interactions between dRich and other postsynaptic components will test the role of dRich in membrane morphogenesis.

Materials and methods

Fly stocks and genetics

The wild-type strain used was w1118. Two P-element alleles of drich, G4993 and G6428, were obtained from GenExel and imprecisely excised to generate drich1 and drich2, respectively. Transgenic lines carrying UAS-drich, UAS-drich-R287A, UAS-HA-drich, UAS-HA-drichΔP4, UAS-drichΔBAR-GFP, UAS-dcip4, and UAS-gbb-GFP were obtained in the w1118 background using standard protocols (Robertson et al., 1988). Transgenes were expressed using either the muscle-specific BG57-GAL4 (Budnik et al., 1996) or neuron-specific C155-GAL4 driver (Lin and Goodman, 1994). Df(3L)ED4342 (a deficiency of the cip4 locus), witA12 (Harrison et al., 1995), and dadJ1e4 (Tsuneizumi et al., 1997) flies were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center. wsp1, UAS-wsp, and Df(3R)3450 (a deficiency of the wsp locus) flies were provided by E. Schejter (Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel). gbb1 has been described previously (Wharton et al., 1999).

Molecular biology

A full-length cDNA for drich (CG4755) was obtained from the Drosophila Genomics Resource Center (clone ID: AT11177). For expression in bacteria or mammalian cells, drich cDNA fragments of interest were amplified by PCR and subcloned into the pGEX6P1 (GE Healthcare) or pcDNA3.1-HA (Invitrogen) vector. The dRich-R287A point mutation was made using the QuikChange Multi kit (Agilent Technologies). For expression in the fly and S2R+ cells, PCR-amplified drich sequences were subcloned into the GAL4-based expression vector pUAST (Brand and Perrimon, 1993) or its derivative pUAST-HA.

For dRich GAP activity assays, a cDNA fragment encoding Drosophila RhoA, Rac1, or Cdc42 was PCR amplified from the EST clones GH20776, LD34217, or HL08128, respectively, and subcloned into pCMV-Tag 3B vector (Agilent Technologies). In addition, a cDNA fragment encoding dRich was amplified by PCR from the EST clone AT11177 and subcloned into the pEGFPN2 vector (Takara Bio Inc.). The cDNA inserts in the resulting constructs were transferred with the corresponding tag sequence into the pAc5.1 vector (Invitrogen) for S2 expression of the fusion proteins.

The following primers were used to characterize drich excision lines at the molecular level: drich1, 5′-ATGGTCAGCAGTTCCAAGACT-3′ and 5′-GCCGGAGCGTTGCTGCTCTTG-3′; and drich2, 5′-ATGGTCAGCAGTTCCAAGACT-3′ and 5′-TACACTACGCGCACCCACTCT-3′. The effects of drich1 and drich2 mutations on the expression of drich and its neighboring genes Surf6 and CG12378 were analyzed by RT-PCR. In brief, total RNA was extracted from larval extracts using TRIzol (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription was performed with 1 µg RNA, an oligo-dT primer, and the SuperScript II reverse transcription kit (Invitrogen). The resulting cDNA was analyzed by PCR using the following primers: drich, 5′-AGATCGAGCAAGTCGGACAGC-3′ and 5′-TACGTGCTGCAGGGCGCGCTC-3′; Surf6, 5′-ACACAACAAGGATCAGAAGCCGGA-3′ and 5′-TGGAGTAGACGATCTTGGCCTCCT-3′; CG12378, 5′-ATGTCTTTCGTTGGAGAAGTT-3′ and 5′-CCTCTGCGTATTATGCATTTG-3′; and rp49, 5′-CACCAGTCGGATCGATATGC-3′ and 5′-CACGTTGTGCACCAGGAACT-3′.

For RNA-mediated knockdown of dRich in S2R+ cells, drich dsRNAs were generated by in vitro transcription of a DNA template containing T7 promoter sequences at both ends as described previously (Lee et al., 2007). The DNA template was PCR amplified from a full-length cDNA of drich using the primers containing a 5′ T7 RNA polymerase-binding site followed by drich-specific sequences 5′-CATCTGACATCCACAAACCG-3′ and 5′-GAATGTCTAGAGGTTCGGTG-3′.

Generation of dRich antibody

To generate an antibody against dRich, GST-dRich-N (amino acids 1–255) fusion protein was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (Agilent Technologies), purified with glutathione–Sepharose 4B, and digested with PreScission protease (GE Healthcare). The cleaved dRich-N protein was separated by SDS-PAGE gels for the immunization of guinea pigs. Antisera were affinity purified using GST-dRich-N cross-linked to CNBr-activated Sepharose 4 Fast Flow beads (GE Healthcare).

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed as described previously (Lee et al., 2007). Primary antibodies were used at the following dilutions: guinea pig anti-dRich, 1:1,000 (this study); rat anti-dCIP4, 1:1,000 (Nahm et al., 2010); rabbit anti-Myc, 1:1,000 (Cell Signaling Technology); rat anti-HA, 1:1,000 (Roche); rabbit anti–β-actin, 1:1,000 (Sigma-Aldrich); rabbit anti-GluRIIB, 1:400 (Liebl et al., 2005); and mouse anti-GFP, 1:1,000 (Roche).

dRich GAP activity assay

Inactivation of Rho GTPases by dRich in cells was assayed using the EZ-detect Rho, Rac, or Cdc42 activation kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). In brief, pAc-drich-GFP or pAc-drichR287A-GFP was cotransfected with pAc-Myc-RhoA, Rac1, or Cdc42 into S2R+ cells. After 48 h, cells were lysed in 25 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1% NP-40, 1 mM DTT, and 5% glycerol and clarified by centrifugation at 13,000 g for 10 min. Equal volumes of lysates were incubated at 4°C for 1 h with glutathione–Sepharose 4B–bound GST-Rhotekin-p21–binding domain (for RhoA-GTP) or GST-PAK1-PBD proteins (for Rac1-GTP and Cdc42-GTP). The beads were washed four times with the lysis buffer and boiled in SDS sample buffer. The amount of GTP-bound Myc-RhoA, Rac1, or Cdc42 was determined by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using an anti-Myc antibody.

Cell transfections and binding experiments

HEK293 and COS-7 cells were maintained in DME supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS at 55°C for 30 min. S2R+ cells were grown in Schneider’s medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS. Cells were transfected by using either Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) or Cellfectin (Invitrogen).

GST pull-down assays were performed to detect dRich–dCIP4 interaction and map the dCIP4-binding motif in dRich. In brief, GST, GST-dCIP4 (amino acids 1–631), dCIP4ΔSH3 (1–527), and GST-dCIP4-SH3 (528–631) were expressed in E. coli and purified using glutathione–Sepharose 4B. HEK293 cells expressing HA-dRich (1–740), HA-dRichΔP4 (1–710), HA-dRichΔP3-4 (1–565), HA-dRichΔP2-4 (1–538), or HA-dRichΔP1-4 (1–496) were homogenized in 500 µl lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.5% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and protease inhibitors). 450 µl cell lysates was incubated with glutathione–Sepharose 4B bead–bound 20 µg GST fusions overnight at 4°C. The beads were washed four times with the lysis buffer, and precipitated proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using anti-HA.

Immunoprecipitation was performed essentially as previously described (Lee et al., 2007). In brief, S2 cells expressing dRich-GFP were homogenized in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.5% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and protease inhibitors) and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. Supernatants were precleared by incubation with protein A/G PLUS agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) for 1 h at 4°C. The samples were incubated with IgG or anti-GFP (Abcam) for 4 h at 4°C and incubated with protein A/G PLUS agarose for 2 h at 4°C. Beads were washed three times with the lysis buffer and boiled in SDS sample buffer for SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using anti-dCIP4.

Immunohistochemistry and morphological quantification

Wandering third instar larvae were live dissected in Ca2+-free HL3 saline (Stewart et al., 1994) and fixed in either 4% formaldehyde for 30 min or in Bouin’s fixative (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min (for staining with anti-NC82, anti–α-spectrin, anti-GluRIIA, anti-GluRIIB, or anti-GluRIIC). Antibody staining for fixed larvae was performed as previously described (Lee et al., 2009). Primary antibodies were used at the following dilutions: guinea pig anti-dRich, 1:100; rat anti-dCIP4, 1:100; guinea pig anti-Wsp, 1:100 (Bogdan et al., 2005); FITC-conjugated goat anti-HRP, 1:200 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.); rabbit anti-GFP, 1:250 (Abcam); rat anti-HA, 1:100 (Roche); rabbit anti-GluRIIB, 1:2,500; and rabbit anti-GluRIIC, 1:2,000 (Marrus et al., 2004). The following monoclonal antibodies from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank were also used: anti-Dlg (4F3; 1:500), anti–α-spectrin (3A9; 1:30), anti-cysteine string protein (1G12; 1:100), anti-Bruchpilot (NC82; 1:10), anti-GluRIIA (1:10), anti-Elav (1:10), and anti–fasciclin II (1D4; 1:10). FITC-, Cy3-, and Cy5-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.) were used at 1:200. To visualize postsynaptic F-actin, rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin (Invitrogen) was used at 1:150. Images were taken at room temperature with a laser-scanning confocal microscope (FV300; Olympus) using a Plan Apo 40× 0.90 NA or U Plan Apo 100× 1.35 NA objective lens and were processed using FLOUVIEW image analysis software (version 5.0; Olympus). To compare different genotypes, samples for each experiment were processed simultaneously and imaged under identical confocal settings.

Quantification of NMJ morphological features was performed at muscles 6/7 and muscle 4 of abdominal segment 2. Bouton number, satellite bouton number, and NMJ length were measured using anti-HRP staining. NMJ length was measured as the total length of synaptic branches. A synaptic branch was defined as an arborization with two or more boutons as previously described (Wu et al., 2005). Satellite boutons were defined as any single boutons extending from synaptic branches. Muscle surface area was visualized by saturating HRP signal and measured using the FLOUVIEW software. For quantification of bouton size, we analyzed only three type Ib terminal boutons from randomly selected NMJ 6/7 branches. For each genotype, ∼44–89 individual boutons were manually measured using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). For quantification of GluR abundance, larval NMJs were double stained with anti-HRP and either anti-GluRIIA, GluRIIB, or GluRIIC. The fluorescence intensity of each receptor was measured using the FLOUVIEW software and normalized to HRP intensity. The size and distribution of GluR clusters were analyzed essentially as previously described (Pielage et al., 2006). In brief, larval NMJs of each genotype were stained with anti-NC82 and anti-GluRIIB or GluRIIC, and z-series stacks collected with intervals of 0.2 µm were projected using the maximum intensity method. To avoid a requirement for fluorescence intensity calibration between genotypes, the intensity of GluRIIB fluorescence in wild type was artificially increased to drich1/drich2 mutant levels. The size and number of GluR clusters and NC82 puncta were measured using the analyze particle function in ImageJ. Student’s t test was used for statistical analysis. The data are presented as mean ± SEM. The numbers of samples analyzed are indicated inside the bars.

EM

Preparation of third instar larvae for EM was performed as described previously (Lee et al., 2009). Type Ib boutons at NMJ 6/7 (segment A2) were serially sectioned (90 nm) and photographed at 20,000× with the Digital Micrograph software (GATAN) driving a charge-coupled device camera (Orius). 6–10 preparations were analyzed for wild type (12 boutons), drich1/drich2 (11 boutons), BG57-GAL4,drich2/UAS-drich,drich1 (9 boutons), BG57-GAL4,drich2/UAS-drich-R287A,drich1 (12 boutons), and BG57-GAL4,drich2/UAS-drichΔBAR-GFP,drich1 (11 boutons). For each bouton, the largest diameter section representing the bouton midline was analyzed using ImageJ.

We analyzed the following parameters as described previously (Budnik et al., 1996; Lee et al., 2009): (a) the midline cross-sectional area (micrometers squared) of boutons, (b) the SSR thickness (micrometers) at each bouton (the distance between the presynaptic membrane and the outermost SSR membrane), (c) the density of SSR (the number of SSR layers/micrometer), (d) the cross-sectional area of the SSR (micrometers squared) per bouton, and (e) the total area of untubular sarcoplasmic patches (micrometers squared) per SSR. Untubular sarcoplasmic patches are defined as sarcoplasmic space between electron-light cisternae that form a gap >0.05 µm2 except the sarcoplasmic region containing subcellular organelles or structures, including mitochondria, that structurally obstruct tubular SSR organization. The Student’s t test was used for statistical analysis. The data are presented as mean ± SEM. The numbers of samples analyzed are indicated inside the bars.

NMJ electrophysiology

TEVC records were made at the wandering third instar NMJ as previously described (Rohrbough et al., 1999; Long et al., 2008; Venkatachalam et al., 2008). In brief, staged control and mutant animals were secured on sylgard-coated coverslips with surgical glue (liquid suture), dissected longitudinally along the dorsal midline, and glued flat. The segmental nerves were cut near the base of the ventral nerve cord. Recording was performed in 128 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 5 mM trehalose, 70 mM sucrose, and 5 mM Hepes. Recording electrodes (1-mm outer diameter capillaries; World Precision Instruments, Inc.) were filled with 3 M KCl and had resistances of <15 MΩ. EJC recordings were performed in voltage-clamped (Vhold = −60 mV) muscle 6 in segment A3 with an amplifier (Axoclamp 200B; MDS Analytical Technologies). The cut segmental nerve was stimulated with a glass suction electrode at a suprathreshold voltage level (50% above baseline threshold value) for a duration of 0.5 ms. Records were made with 0.5 Hz nerve stimulation in episodic acquisition setting. Current signals were filtered at 1,000 Hz and analyzed with Clampex software (version 7.0; Axon Instruments). mEJC records were made in continuous, gap-free recording mode. Each n = 1 represents 120 s of recording from one animal. Traces were filtered in a low-pass setting at 450 Hz (pClamp software; version 7.0; Axon Instruments) and analyzed for mean peak amplitude (nA) and frequency (Hz). Statistical comparisons were performed using Mann–Whitney nonparametric tests.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows the effect of drich mutations or overexpression on synapse growth at the NMJ. Fig. S2 shows the conserved biochemical properties of dRich in cultured cells. Fig. S3 shows that levels and distribution of transgenic dRich, dRich-RA, dRich-GFP, and dRichΔBAR-GFP expression in drich muscles are comparable. Fig. S4 shows quantification of synaptic and extrasynaptic dRich levels in larvae overexpressing HA-dRich or HA-dRichΔP4 postsynaptically and of synaptic Wsp levels in wild-type and drich larvae and larvae overexpressing HA-dRich, HA-dRichΔP4, or dRichΔBAR-GFP postsynaptically. Fig. S5 shows dRich regulation of postsynaptic F-actin and spectrin at the NMJ. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.201007086/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Young-Ho Koh for the BG57-GAL4 line, Eyal Schejter for the wsp1 and Df(3R)3450 lines, Aaron DiAntonio for anti-GluRIIB and anti-GluRIIC antibodies, David Featherstone for anti-GluRIIB antibody, and Sven Bogdan for anti-Wsp antibody.

This work was supported by grants from the Brain Research Center of the 21st Century Frontier (2009K001278), Science Research Center (2010-0029398), and the Korea Research Foundation (KRF-2006-312-C00361) to S. Lee and from the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM54544) to K. Broadie.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- BAR

- BIN/amphiphysin/Rvs domain

- BMP

- bone morphogenetic protein

- CIP4

- Cdc42-interacting protein 4

- dCIP4

- Drosophila CIP4

- Dlg

- Discs large

- dRich

- Drosophila Rich

- EJC

- excitatory junctional current

- F-actin

- filamentous actin

- GAP

- GTPase-activating protein

- Gbb

- Glass bottom boat

- GluR

- glutamate receptor

- mEJC

- miniature EJC

- NMJ

- neuromuscular junction

- PBD

- p21-binding domain

- P-Mad

- phosphorylated Mad

- Sax

- saxophone

- SSR

- subsynaptic reticulum

- TEVC

- two-electrode voltage clamp

- Tkv

- thick veins

- WASp

- Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein

- Wit

- wishful thinking

References

- Aberle H., Haghighi A.P., Fetter R.D., McCabe B.D., Magalhães T.R., Goodman C.S. 2002. wishful thinking encodes a BMP type II receptor that regulates synaptic growth in Drosophila. Neuron. 33:545–558 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00589-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan S., Stephan R., Löbke C., Mertens A., Klämbt C. 2005. Abi activates WASP to promote sensory organ development. Nat. Cell Biol. 7:977–984 10.1038/ncb1305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand A.H., Perrimon N. 1993. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 118:401–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budnik V., Koh Y.H., Guan B., Hartmann B., Hough C., Woods D., Gorczyca M. 1996. Regulation of synapse structure and function by the Drosophila tumor suppressor gene dlg. Neuron. 17:627–640 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80196-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle I.P., Koh Y.H., Lee W.C., Slind J., Fergestad T., Littleton J.T., Ganetzky B. 2004. Nervous wreck, an SH3 adaptor protein that interacts with Wsp, regulates synaptic growth in Drosophila. Neuron. 41:521–534 10.1016/S0896-6273(04)00016-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiAntonio A., Petersen S.A., Heckmann M., Goodman C.S. 1999. Glutamate receptor expression regulates quantal size and quantal content at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. J. Neurosci. 19:3023–3032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone D.E., Rushton E., Rohrbough J., Liebl F., Karr J., Sheng Q., Rodesch C.K., Broadie K. 2005. An essential Drosophila glutamate receptor subunit that functions in both central neuropil and neuromuscular junction. J. Neurosci. 25:3199–3208 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4201-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouquet W., Owald D., Wichmann C., Mertel S., Depner H., Dyba M., Hallermann S., Kittel R.J., Eimer S., Sigrist S.J. 2009. Maturation of active zone assembly by Drosophila Bruchpilot. J. Cell Biol. 186:129–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricke R., Gohl C., Dharmalingam E., Grevelhörster A., Zahedi B., Harden N., Kessels M., Qualmann B., Bogdan S. 2009. Drosophila Cip4/Toca-1 integrates membrane trafficking and actin dynamics through WASP and SCAR/WAVE. Curr. Biol. 19:1429–1437 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost A., Perera R., Roux A., Spasov K., Destaing O., Egelman E.H., De Camilli P., Unger V.M. 2008. Structural basis of membrane invagination by F-BAR domains. Cell. 132:807–817 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatto C.L., Broadie K. 2008. Temporal requirements of the fragile X mental retardation protein in the regulation of synaptic structure. Development. 135:2637–2648 10.1242/dev.022244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goold C.P., Davis G.W. 2007. The BMP ligand Gbb gates the expression of synaptic homeostasis independent of synaptic growth control. Neuron. 56:109–123 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan B., Hartmann B., Kho Y.H., Gorczyca M., Budnik V. 1996. The Drosophila tumor suppressor gene, dlg, is involved in structural plasticity at a glutamatergic synapse. Curr. Biol. 6:695–706 10.1016/S0960-9822(09)00451-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haghighi A.P., McCabe B.D., Fetter R.D., Palmer J.E., Hom S., Goodman C.S. 2003. Retrograde control of synaptic transmission by postsynaptic CaMKII at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. Neuron. 39:255–267 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00427-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada A., Furuta B., Takeuchi K., Itakura M., Takahashi M., Umeda M. 2000. Nadrin, a novel neuron-specific GTPase-activating protein involved in regulated exocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 275:36885–36891 10.1074/jbc.M004069200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison S.D., Solomon N., Rubin G.M. 1995. A genetic analysis of the 63E-64A genomic region of Drosophila melanogaster: identification of mutations in a replication factor C subunit. Genetics. 139:1701–1709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan L.Y., Jan Y.N. 1982. Antibodies to horseradish peroxidase as specific neuronal markers in Drosophila and in grasshopper embryos. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 79:2700–2704 10.1073/pnas.79.8.2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshishian H., Kim Y.S. 2004. Orchestrating development and function: retrograde BMP signaling in the Drosophila nervous system. Trends Neurosci. 27:143–147 10.1016/j.tins.2004.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V., Fricke R., Bhar D., Reddy-Alla S., Krishnan K.S., Bogdan S., Ramaswami M. 2009. Syndapin promotes formation of a postsynaptic membrane system in Drosophila. Mol. Biol. Cell. 20:2254–2264 10.1091/mbc.E08-10-1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzetti L. 2007. Actin in membrane trafficking. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19:453–458 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Lee Y., Lee J., Bang S., Hyun S., Kang J., Hong S.T., Bae E., Kaang B.K., Kim J. 2005. Pyrexia is a new thermal transient receptor potential channel endowing tolerance to high temperatures in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Genet. 37:305–310 10.1038/ng1513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Nahm M., Lee M., Kwon M., Kim E., Zadeh A.D., Cao H., Kim H.J., Lee Z.H., Oh S.B., et al. 2007. The F-actin-microtubule crosslinker Shot is a platform for Krasavietz-mediated translational regulation of midline axon repulsion. Development. 134:1767–1777 10.1242/dev.02842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M., Paik S.K., Lee M.J., Kim Y.J., Kim S., Nahm M., Oh S.J., Kim H.M., Yim J., Lee C.J., et al. 2009. Drosophila Atlastin regulates the stability of muscle microtubules and is required for synapse development. Dev. Biol. 330:250–262 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibfried A., Fricke R., Morgan M.J., Bogdan S., Bellaiche Y. 2008. Drosophila Cip4 and WASp define a branch of the Cdc42-Par6-aPKC pathway regulating E-cadherin endocytosis. Curr. Biol. 18:1639–1648 10.1016/j.cub.2008.09.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebl F.L., Chen K., Karr J., Sheng Q., Featherstone D.E. 2005. Increased synaptic microtubules and altered synapse development in Drosophila sec8 mutants. BMC Biol. 3:27 10.1186/1741-7007-3-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D.M., Goodman C.S. 1994. Ectopic and increased expression of Fasciclin II alters motoneuron growth cone guidance. Neuron. 13:507–523 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90022-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long A.A., Kim E., Leung H.T., Woodruff E., III, An L., Doerge R.W., Pak W.L., Broadie K. 2008. Presynaptic calcium channel localization and calcium-dependent synaptic vesicle exocytosis regulated by the Fuseless protein. J. Neurosci. 28:3668–3682 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5553-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marqués G., Zhang B. 2006. Retrograde signaling that regulates synaptic development and function at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 75:267–285 10.1016/S0074-7742(06)75012-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marqués G., Bao H., Haerry T.E., Shimell M.J., Duchek P., Zhang B., O’Connor M.B. 2002. The Drosophila BMP type II receptor Wishful Thinking regulates neuromuscular synapse morphology and function. Neuron. 33:529–543 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00595-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrus S.B., Portman S.L., Allen M.J., Moffat K.G., DiAntonio A. 2004. Differential localization of glutamate receptor subunits at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. J. Neurosci. 24:1406–1415 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1575-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe B.D., Marqués G., Haghighi A.P., Fetter R.D., Crotty M.L., Haerry T.E., Goodman C.S., O’Connor M.B. 2003. The BMP homolog Gbb provides a retrograde signal that regulates synaptic growth at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. Neuron. 39:241–254 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00426-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe B.D., Hom S., Aberle H., Fetter R.D., Marques G., Haerry T.E., Wan H., O’Connor M.B., Goodman C.S., Haghighi A.P. 2004. Highwire regulates presynaptic BMP signaling essential for synaptic growth. Neuron. 41:891–905 10.1016/S0896-6273(04)00073-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahm M., Kim S., Paik S.K., Lee M., Lee S., Lee Z.H., Kim J., Lee D., Bae Y.C., Lee S. 2010. dCIP4 (Drosophila Cdc42-interacting protein 4) restrains synaptic growth by inhibiting the secretion of the retrograde Glass bottom boat signal. J. Neurosci. 30:8138–8150 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0256-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor-Giles K.M., Ho L.L., Ganetzky B. 2008. Nervous wreck interacts with thickveins and the endocytic machinery to attenuate retrograde BMP signaling during synaptic growth. Neuron. 58:507–518 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen S.A., Fetter R.D., Noordermeer J.N., Goodman C.S., DiAntonio A. 1997. Genetic analysis of glutamate receptors in Drosophila reveals a retrograde signal regulating presynaptic transmitter release. Neuron. 19:1237–1248 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80415-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pielage J., Fetter R.D., Davis G.W. 2006. A postsynaptic spectrin scaffold defines active zone size, spacing, and efficacy at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. J. Cell Biol. 175:491–503 10.1083/jcb.200607036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin G., Schwarz T., Kittel R.J., Schmid A., Rasse T.M., Kappei D., Ponimaskin E., Heckmann M., Sigrist S.J. 2005. Four different subunits are essential for expressing the synaptic glutamate receptor at neuromuscular junctions of Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 25:3209–3218 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4194-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawson J.M., Lee M., Kennedy E.L., Selleck S.B. 2003. Drosophila neuromuscular synapse assembly and function require the TGF-beta type I receptor saxophone and the transcription factor Mad. J. Neurobiol. 55:134–150 10.1002/neu.10189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razzaq A., Robinson I.M., McMahon H.T., Skepper J.N., Su Y., Zelhof A.C., Jackson A.P., Gay N.J., O’Kane C.J. 2001. Amphiphysin is necessary for organization of the excitation-contraction coupling machinery of muscles, but not for synaptic vesicle endocytosis in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 15:2967–2979 10.1101/gad.207801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richnau N., Aspenström P. 2001. Rich, a rho GTPase-activating protein domain-containing protein involved in signaling by Cdc42 and Rac1. J. Biol. Chem. 276:35060–35070 10.1074/jbc.M103540200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richnau N., Fransson A., Farsad K., Aspenström P. 2004. RICH-1 has a BIN/Amphiphysin/Rvsp domain responsible for binding to membrane lipids and tubulation of liposomes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 320:1034–1042 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson H.M., Preston C.R., Phillis R.W., Johnson-Schlitz D.M., Benz W.K., Engels W.R. 1988. A stable genomic source of P element transposase in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 118:461–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinow S., White K. 1991. Characterization and spatial distribution of the ELAV protein during Drosophila melanogaster development. J. Neurobiol. 22:443–461 10.1002/neu.480220503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbough J., Pinto S., Mihalek R.M., Tully T., Broadie K. 1999. latheo, a Drosophila gene involved in learning, regulates functional synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 23:55–70 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80753-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid A., Hallermann S., Kittel R.J., Khorramshahi O., Frölich A.M., Quentin C., Rasse T.M., Mertel S., Heckmann M., Sigrist S.J. 2008. Activity-dependent site-specific changes of glutamate receptor composition in vivo. Nat. Neurosci. 11:659–666 10.1038/nn.2122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart B.A., Atwood H.L., Renger J.J., Wang J., Wu C.F. 1994. Improved stability of Drosophila larval neuromuscular preparations in haemolymph-like physiological solutions. J. Comp. Physiol. [A]. 175:179–191 10.1007/BF00215114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strigini M., Cohen S.M. 2000. Wingless gradient formation in the Drosophila wing. Curr. Biol. 10:293–300 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00378-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney S.T., Davis G.W. 2002. Unrestricted synaptic growth in spinster–a late endosomal protein implicated in TGF-beta-mediated synaptic growth regulation. Neuron. 36:403–416 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)01014-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao H.W., Poo M. 2001. Retrograde signaling at central synapses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:11009–11015 10.1073/pnas.191351698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotta N., Rodesch C.K., Fergestad T., Broadie K. 2004. Cellular bases of activity-dependent paralysis in Drosophila stress-sensitive mutants. J. Neurobiol. 60:328–347 10.1002/neu.20017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuneizumi K., Nakayama T., Kamoshida Y., Kornberg T.B., Christian J.L., Tabata T. 1997. Daughters against dpp modulates dpp organizing activity in Drosophila wing development. Nature. 389:627–631 10.1038/39362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam K., Long A.A., Elsaesser R., Nikolaeva D., Broadie K., Montell C. 2008. Motor deficit in a Drosophila model of mucolipidosis type IV due to defective clearance of apoptotic cells. Cell. 135:838–851 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]