Abstract

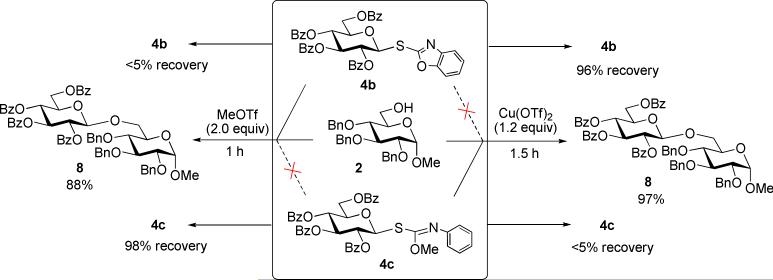

It is reported that S-glycosyl O-methyl phenylcarbamothioates (SNea carbamothioates) have a fully orthogonal character in comparison to S-benzoxazolyl (SBox) glycosides. This complete orthogonality was revealed by performing competitive glycosylation experiments in the presence of various promoters. The results obtained indicate that SNea carbamothioates have a very similar reactivity profile to that of glycosyl thiocyanates, yet are significantly more stable and tolerate selected protecting group manipulations. These features make the SNea carbamothioates new promising building blocks for further utilization in oligosaccharide synthesis.

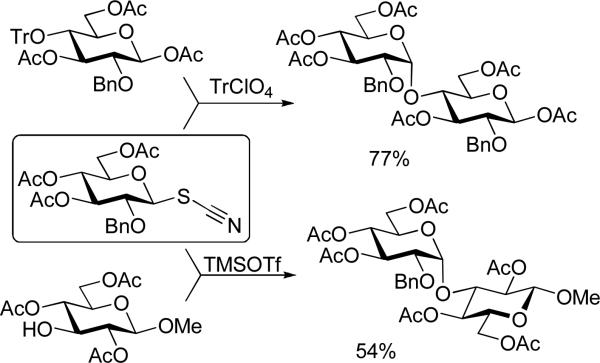

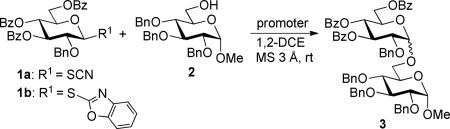

The stereocontrolled introduction of glycosidic linkages1,2 is arguably the most challenging aspect in the synthesis of oligosaccharides3-9 and glycoconjugates.10-12 A broad variety of factors is known to have a profound effect on the stereoselectivity outcome of the chemical glycosylation.13 Although a typical glycosylation reaction follows the unimolecular mechanism with the rate-determining step being the attack of the glycosyl acceptor on the intermediate formed as a result of the leaving group departure;14,15 the effect of a leaving group is important. The belief that the nature of the leaving group itself may also have an influence on the anomeric stereoselectivity led to the development of a myriad of glycosyl donors.2 However, it is not always clear whether this effect is a result of a bimolecular, close-ion-pair displacement mechanism, or others. For instance, glycosyl thiocyanates were introduced two decades ago as very effective glycosyl donors for 1,2-cis glycosylations.16,17 Various hexose and pentose 1,2-trans thiocyanate glycosyl donors were found to provide challenging 1,2-cis glycosides18 with complete stereoselectivity. While tritylated acceptors were used in most of the reported transformations, a procedure involving unprotected hydroxyl was also developed.19 These two typical examples of glycosylation using the thiocyanate methodology are illustrated in Scheme 1. A major drawback of this technique is modest yields obtained during both the synthesis of glycosyl thiocyanates and their glycosidations. The modest yields are typically due to the propensity of thiocyanates to isomerize into the corresponding stable isothiocyanates.

Scheme 1.

Reaction of a glycosyl thiocyanate with 4-O-trityl and 3-hydroxyl glycosyl acceptors.19,27

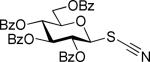

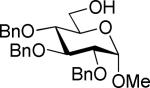

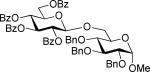

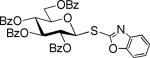

Our laboratory has been investigating glycosyl thioimidates, and the synthesis of the S-benzoxazolyl (SBox)20-22 and S-thiazolinyl (STaz)23,24 derivatives and their application as glycosyl donors has been reported. Undoubtedly, thioimidates have some structural similarity with thiocyanates. However, how these two methodologies compare in glycosylations remained unclear. Therefore, we decided to investigate these two structurally related classes of glycosyl donor by performing comparative side-by-side investigations. For this purpose, we obtained glycosyl donors 1a (SCN) and 1b25 (SBox) and performed direct comparative couplings with glycosyl acceptor 2.26

Silver(I)triflate (AgOTf) that was found to be a very efficient promoter for activating a variety of thioimidates studied in our laboratory,28,29 was similarly effective with both thiocyanate 1a and SBox 1b glycosyl donors. The disaccharide 3 was isolated in around 80% (entries 1 and 2, Table 1). Relatively low stereoselectivity obtained in the glycosidation of thiocyanate 1a was not surprising in light of our recent observation that the stereoselectivity may greatly depend on the nature of the protecting groups used for masking hydroxyl groups of the glycosyl acceptor.30

Table 1.

Comparative studies of glycosyl thiocyanate 1a and S-benzoxazolyl glycoside 1b.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | donor | promoter (equiv)a | time | yield of 3 (α/β ratio) |

| 1 | 1a | AgOTf (1.2) | 48 h | 80% (3/1) |

| 2 | 1b | AgOTf (1.2)b | 48 h | 79% (3.4/1) |

| 3 | 1a | MeOTf (1.2) | 48 h | Traces |

| 4 | 1b | MeOTf (1.2) | 48 h | 76% (3.2/1) |

| 5 | 1a | Cu(OTf)2 (1.2) | 1 h | 95% (9.0/1) |

| 6 | 1b | Cu(OTf)2 (1.2) | 48 h | Traces |

intentionally, only slight excess of promoter has been used in these reactions to gain a better control of the reaction rate

completed in 15 min (86%) with 3 equiv.

Methyl triflate, very commonly used for the activation of thioglycosides31 and thioimidates32 was virtually ineffective in the case of thiocyanate 1a, whereas glycosidation of SBox donor 1b was much more efficient (entries 3 and 4). Conversely, copper(II) triflate, which is too mild an activator to activate SBox glycoside 1b with the 2-Bn-tri-Bz super-disarming protective group pattern,25 was rather effective with glycosyl thiocyanate. Thus, Cu(OTf)2-promoted glycosidation of 1a afforded disaccharide 3 in 95% yield and good stereoselectivity α/β = 9/1 (entry 5). The results summarized in Table 1 indicate potential orthogonality of these two classes of glycosyl donors, however, we anticipate that the application of thiocyanates in orthogonal-like oligosaccharide synthesis33 will be cumbersome due to their general instability.

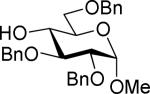

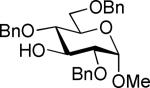

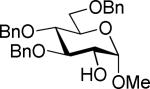

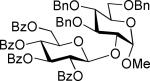

These interesting results stimulated us to pursue more extended comparative studies. Similar comparative reactions have been conducted with glycosyl donors of the disarmed (per-benzoylated) series and glycosyl thiocyanate 4a34,35 and SBox derivative 4b22 have been obtained. To gain a better insight in the nature of effects that prompt similar leaving groups to react so differently, we obtained S-glycosyl O-methyl phenylcarbamothioate 4c (SNea carbamothioate, shown in Table 2).36 The SNea leaving group has been specifically designed to represent a hybrid structure bridging between simple acyclic thiocyanate 4a and cyclic SBox glycoside 4b. In addition, comparison of the SBox and SNea leaving groups could serve as a useful toolkit for studying whether the cyclic structure of thioimidates previously investigated in our laboratory29 and by others32 is truly crucial for the successful activation/application of this class of glycosyl donors.

Table 2.

Comparative studies of per-benzoylated glycosyl thiocyanate 4a, SBox glycoside 4b, and SNea carbamothioate 4c.

| entry | donor | acceptor | promoter (equiv) | time | disaccharide (yield) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

|

MeOTf (1.2) | 22 h |

|

| 4a | 2 | 8 (84%) | |||

| 2 | 4a | 2 | AgOTf (1.2) | 5 min | 8 (82%) |

| 3 | 4a | 2 | AgBF4 (1.2) | 5 min | 8 (95%) |

| 4 | 4a | 2 | Cu(OTf)2 (1.2) | 10 min | 8 (87%) |

| 5 |

|

2 | MeOTf (1.2) | 6 h | 8 (94%) |

| 4b | |||||

| 6 | 4b | 2 | AgOTf (1.2) | 30 min | 8 (88%) |

| 7 | 4b | 2 | AgBF4 (1.2) | 3.5 h | 8 (91%) |

| 8 | 4b | 2 | Cu(OTf)2 (1.2 or 3.0) | 24 h | 8 (35 or 85%) |

| 9 |

|

2 | MeOTf (1.2 or 3.0) | 24 h | 8 (traces or 12%) |

| 4c | |||||

| 10 | 4c | 2 | AgOTf (1.2 or 3.0) | 24 h | 8 (traces or 32%) |

| 11 | 4c | 2 | AgBF4 (1.2 or 3.0) | 24 h | 8 (25 or 55%) |

| 12 | 4c | 2 | Cu(OTf)2 (1.2 or 3.0) | 1 h | 8 (90 or 91%) |

| 13 | 4c |

|

Cu(OTf)2 (3.0)a | 1 h |

|

| 5 | 9 (78%) | ||||

| 14 | 4c |

|

Cu(OTf)2 (3.0)a | 1 h |

|

| 6 | 10 (74%) | ||||

| 15 | 4c |

|

Cu(OTf)2 (3.0)a | 1 h |

|

| 7 | 11 (75%) |

slower reaction (24 h) and lower yields were observed in the presence of 1.2 equiv of the promoter

These comparative studies began with the investigation of per-benzoylated thiocyanate 4a. We found that this derivative can be smoothly activated under a variety of reaction conditions also common for the activation of thioimidates (Table 2). With the exception of the MeOTf-promoted glycosidation that required 22 h to complete (entry 1), reactions with all other activators investigated were completed in less than 10 min (entries 2-4). The disaccharide 8 was obtained with consistently very good to excellent yields (82-95%), hence offering a variety of new effective pathways for the activation of glycosyl thiocyanates, which is significant since previously developed protocols suffered from very modest yields. The fact that perbenzoylated thiocyanate 4a actually reacts in the presence of MeOTf can be explained by its significantly more reactive nature in comparison to that of its superdisarmed counterpart 1a.

The SBox glycoside 4b performed very similarly (entries 5-8), although most reactions, except those promoted with MeOTf (entry 5), were notably slower than the respective reactions with thiocyanate 4a. Cu(OTf)2-promoted reaction required 3 equiv. of the promoter to proceed with acceptable rate and good yield (entry 8). Strikingly, SNea carbamothioate 4c reacted somewhat differently than either thiocyanate 4a or SBox glycoside 4b. First, glycosidations of 4c in the presence of either MeOTf or AgOTf as promoters were virtually ineffective (entries 9 and 10), whereas both 4a and 4b reacted readily. Second, although the reaction of 4c required 3 equiv. of AgBF4, it completed in 15 min (entry 11), similarly to that of thiocyanate 4a, whereas glycosidation of SBox 4b required 3.5 h. Third, Cu(OTf)2 was particularly effective allowing the disaccharide 8 in 90% yield in 1 h (entry 12) even in the presence of a very slight excess of the promoter. These studies were extended to the evaluation of secondary glycosyl acceptors 5-7.37-39 All glycosylations readily afforded the target disaccharides 9-1124,40 in good yields (see entries 13-15 and the SI for characterization data).

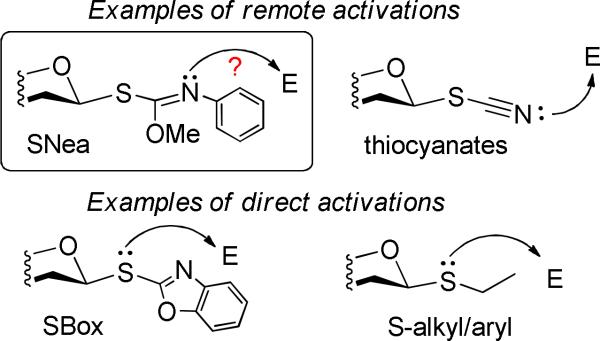

Overall, the reactivity pattern of benzoylated carbamothioate 4c is very similar to that of the superdisarmed thiocyanate 1a observed earlier (Table 1). This led us to postulate that SNea leaving group reacts similarly to that of the SCN, but it is somewhat less reactive and its activation requires more powerful conditions and/or longer reaction time (compare for example results depicted in entries 4 and 12, Table 2). It is possible that SNea moiety follows a remote activation pathway,41 similar to that of thiocyanates (via the nitrogen atom),27 while SBox glycosides were found to be activated directly via the sulfur atom22,42 similarly to that of the conventional alkyl/aryl thioglycosides (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Direct vs. remote activation pathways

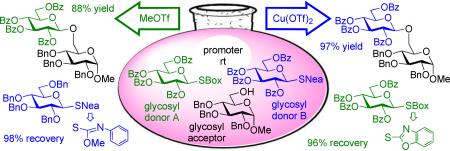

In comparison to the SBox glycosyl donor 4b, SNea derivative 4c may be considered fully orthogonal: the SBox leaving group was promoted much faster in the presence of MeOTf, whereas Cu(OTf)2 was found to be significantly more effective for the activation of SNea carbamothioate. The anticipated orthogonality of the SBox vs. SNea derivatives has been evaluated in the direct competition experiments depicted in Scheme 2. In these reactions, two glycosyl donors 4b and 4c were allowed to compete for one glycosyl acceptor 2. Upon consumption of the acceptor, the products were separated, and the unreacted glycosyl donor was recovered. The differentiation of the SBox and SNea building blocks was found to be very effective in both directions. First, MeOTf-promoted competition experiment led to the formation of disaccharide 8 in 88%. In this case, 98% of SNea glycosyl donor 4c could be recovered while only traces of SBox glycoside 4b were remaining. Second, Cu(OTf)2-promoted competition experiment led to the formation of disaccharide 8 in 97% yield. In this case 96% of SBox glycosyl donor 4b could be recovered while only traces of SNea carbamothioate 4a were present. These results clearly serve as an indication for the highly selective nature of these orthogonal activations.

Scheme 2.

Competitive glycosylations involving differentiation of two glycosyl donors, SBox 4b vs. SNea 4c.

In conclusion, as a part of a study of glycosyl donors with S-C-N generic leaving group structure we described the comparative studies of glycosyl thiocyanates vs. S-benzoxazolyl glycosides. To gain a better insight into the reactivity mode of these structurally similar glycosyl donors react, we designed a bridging structure, SNea carbamothioate, which were found to react similarly to the SCN derivatives. Higher stability of SNea carbamothioate allowed for the investigation of their proposed orthogonality with the SBox glycosides. Further studies of these promising new glycosyl donors in the context of expeditious oligosaccharide synthesis via effective selective or orthogonal activation strategies are currently underway in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by awards from the NIGMS (GM077170), NSF (CHE-0547566), and AHA (0855743G). Dr. Winter and Mr. Kramer (UM – St. Louis) are thanked for HRMS determinations.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures, 1H and 13C NMR spectra for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Demchenko AV, editor. Handbook of Chemical Glycosylation: Advances in Stereoselectivity and Therapeutic Relevance. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu X, Schmidt RR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:1900–1934. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis BG. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 2000:2137–2160. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boons GJ. Drug Discov. Today. 1996;1:331–342. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osborn HMI, Khan TH. Oligosaccharides. Their synthesis and biological roles. Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plante OJ, Palmacci ER, Seeberger PH. Science. 2001;291:1523–1527. doi: 10.1126/science.1057324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demchenko AV. Lett. Org. Chem. 2005;2:580–589. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seeberger PH, Werz DB. Nature. 2007;446:1046–1051. doi: 10.1038/nature05819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smoot JT, Demchenko AV. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 2009;62:161–250. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2318(09)00005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galonic DP, Gin DY. Nature. 2007;446:1000–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature05813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis BG. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1999:3215–3237. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mallet JM, Sinay P. In: Carbohydrates in Chemistry and Biology. Ernst B, Hart GW, Sinay P, editors. Vol. 1. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, New York: 2000. pp. 467–492. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demchenko AV. In: Handbook of Chemical Glycosylation. Demchenko AV, editor. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2008. pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mydock LK, Demchenko AV. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010;8:497–510. doi: 10.1039/b916088d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crich D. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010;43:1144–1153. doi: 10.1021/ar100035r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kochetkov NK, Klimov EM, Malysheva NN. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:5459–5462. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kochetkov NK, Klimov EM, Malysheva NN, Demchenko AV. Bioorg. Khim. 1990;16:701–710. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demchenko AV. Curr. Org. Chem. 2003;7:35–79. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kochetkov NK, Klimov EM, Malysheva NN, Demchenko AV. Carbohydr. Res. 1992;232:C1–C5. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)91007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demchenko AV, Malysheva NN, De Meo C. Org. Lett. 2003;5:455–458. doi: 10.1021/ol0273452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamat MN, De Meo C, Demchenko AV. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:6947–6955. doi: 10.1021/jo071191s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamat MN, Rath NP, Demchenko AV. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:6938–6946. doi: 10.1021/jo0711844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demchenko AV, Pornsuriyasak P, De Meo C, Malysheva NN. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:3069–3072. doi: 10.1002/anie.200454047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pornsuriyasak P, Demchenko AV. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:6630–6646. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamat MN, Demchenko AV. Org. Lett. 2005;7:3215–3218. doi: 10.1021/ol050969y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuester JM, Dyong I. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1975:2179–2189. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kochetkov NK, Klimov EM, Malysheva NN, Demchenko AV. Carbohydr. Res. 1991;212:77–91. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(91)84047-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramakrishnan A, Pornsuriyasak P, Demchenko AV. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 2005;24:649–663. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pornsuriyasak P, Kamat MN, Demchenko AV. ACS Symp. Ser. 2007;960:165–189. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaeothip S, Akins SJ, Demchenko AV. Carbohydr. Res. 2010;345:2146–2150. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhong W, Boons G-J. In: Handbook of Chemical Glycosylation. Demchenko AV, editor. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2008. pp. 261–303. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szeja W, Grynkiewicz G. In: Handbook of Chemical Glycosylation. Demchenko AV, editor. Wiley-VCH; Weinhein, Germany: 2008. pp. 329–361. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanie O. In: Carbohydrates in Chemistry and Biology. Ernst B, Hart GW, Sinay P, editors. Vol. 1. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, New York: 2000. pp. 407–426. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pakulski Z, Pierozynski D, Zamojski A. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:2975–2992. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Somsák L, Czifrák K, Deim T, Szilágyi L, Bényei A. Tetrahedron: Asymmerty. 2001;12:731–736. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Note: , SNea 4c can be prepared from benzobromoglucose directly, but in our hands higher overall yield was obtained from acetobromoglucose followed by sequential deacetylationbenzoylation (see SI for details).

- 37.Garegg PJ, Hultberg H. Carbohydr. Res. 1981;93:C10–C11. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koto S, Takebe Y, Zen S. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1972;45:291–293. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sollogoub M, Das SK, Mallet J-M, Sinay P. C. R. Acad. Sci. Ser. 2. 1999;2:441–448. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaeothip S, Pornsuriyasak P, Demchenko AV. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:1542–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2007.12.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hanessian S, Bacquet C, Lehong N. Carbohydr. Res. 1980;80:c17–c22. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaeothip S, Pornsuriyasak P, Rath NP, Demchenko AV. Org. Lett. 2009;11:799–802. doi: 10.1021/ol802740b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.