Abstract

Molecular-scale pore structures, called nanopores, can be assembled by protein ion channels through genetic engineering or be artificially fabricated on solid substrates using fashion nanotechnology. When target molecules interact with the functionalized lumen of a nanopore, they characteristically block the ion pathway. The resulting conductance changes allow for identification of single molecules and quantification of target species in the mixture. In this review, we first overview nanopore-based sensory techniques that have been created for the detection of myriad biomedical targets, from metal ions, drug compounds, and cellular second messengers to proteins and DNA. Then we introduce our recent discoveries in nanopore single molecule detection: (1) using the protein nanopore to study folding/unfolding of the G-quadruplex aptamer; (2) creating a portable and durable biochip that is integrated with a single-protein pore sensor (this chip is compared with recently developed protein pore sensors based on stabilized bilayers on glass nanopore membranes and droplet interface bilayer); and (3) creating a glass nanopore-terminated probe for single-molecule DNA detection, chiral enantiomer discrimination, and identification of the bioterrorist agent ricin with an aptamer-encoded nanopore.

1. Principle of nanopore sensors for single molecule detection

Ion channels are transmembrane protein pores that open and close in response to chemical, electrical, or mechanical stimuli1. For example, the membrane-bound nicotinic acetylcholine receptor on a nerve cell can be opened by the binding of a specific neural transmitter to its recognition site. A protein channel in the open state can selectively transport ions across the cell membrane under an applied transmembrane voltage, generating a pico-Ampere ion current that can be measured electrically. Through protein engineering, a correlation between the probability of an open pore and the intensity of a stimulus can be established, such as ligand concentration1. Such engineered protein pores can act as target-responsive biosensors2. Due to its nanometer-scale pore size, the engineered protein pore is also called a “nanopore.”

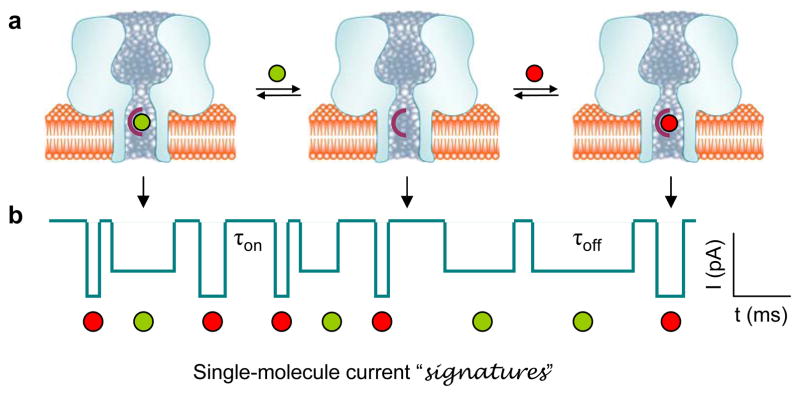

Distinct from other biosensor systems, the nanopore sensor is a single-molecule detector—it detects the binding of individual molecules to a recognition group within the pore. Fig. 1 shows the principle for nanopore detection. First, a hydrophobic film (e.g., Teflon) is used to partition the recording cell into two chambers, cis and trans. A planar lipid bilayer is then formed over a tiny orifice (~100 nm) in the center of the partition. Channel proteins on one side of the bilayer will be spontaneously inserted into the bilayer to form pores that constitute the only path for ionic flow between solutions on both sides. Two Ag/AgCl electrodes connect two chamber solutions with an amplifier (e.g., Axopatch from Molecular Devices Ins) to provide voltage and record pico-Ampere current through the protein pore. The protein pore is engineered with a recognition probe in the lumen; without a bound target, the pore remains open (Fig. 1a middle; current in Fig. 1b marked by arrow). When a single molecule binds to the probe, the pore current is blocked, but when the molecule is released, the ionic current resumes (Fig. 1a, left and right; Fig. 1b, current blocks marked by arrows). Repeated cycles of binding and release of individual target molecules to and from the pore result in a string of binary (on/off) blocks.

Figure 1.

Single-molecule detection in a protein pore. (a) Competitive and reversible binding of different analytes (represented by green and red balls) to a receptor engineered in the protein pore. (b) Stochastic current blocks function as “signatures” of single bound analytes, which, based on block amplitude and duration, allow for the identification of the unknown analytes. In the diagram, the red analyte blocks more current with a shorter duration than the green one. Analytes can also be quantified by their block occurrence.

Because of the stochastic nature, individual block durations differ. Statistically, however, they follow an exponential distribution. The fitted constant is defined as the average block duration, τoff, which is unique for a target species and independent of the target concentration. τoff and the change in conductance amplitude, Δg, represent a signature of target identification. With τoff, the dissociation rate constant koff can be calculated by koff = 1/τoff. By counting the frequency of binding events, one can also quantify the target by measuring the interval between two adjacent blocks. Similar to the block duration, the stochastic intervals also follow an exponential distribution, and the constant τon is the average interval. The inverted value of τon is the frequency of event occurrence (f=1/τon), which is proportional to the target concentration ([T]), using the coefficient as the association rate constant kon, i.e. f = kon[T].

2. A survey of nanopore single-molecule detection

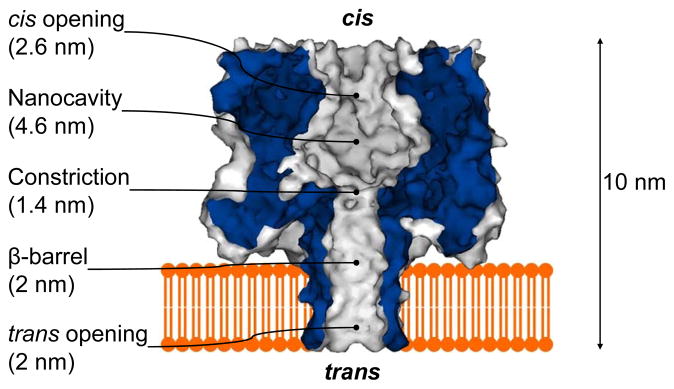

Many nanopore applications have been developed using α-hemolysin as the model pore, an exotoxin that is secreted by the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus. The monomeric α-hemolysin contains 293 amino acids, wherein seven monomers self-assemble in the lipid bilayer to form a 10-nm-long heptameric pore that consists of a 2-nm-wide transmembrane β-barrel and a 4.6-nm-wide nanocavity above the β-barrel3 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Molecular graph of the heptameric α-hemolysin pore in the lipid bilayer and diagrams for various single molecule detections using α-hemolysin3. The dimensions of the various regions in the lumen of the pore are provided.

The Bayley group has performed pioneer and seminal work on α-hemolysin pore-based biosensing 4,5. The representative contributions are selected as follows. A tetrahistidine motif that is engineered on one of the seven subunits in the lumen of the β-barrel can reversibly capture single divalent metal ions such as Zn2+ and Co2+, enabling one pore to detect metal ions at nanomolar concentrations in the mixture6. The pore, equipped with double arginine rings near the constrictive domain, discriminates between biologically significant phosphate compounds, including adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and the second messenger inositol triphosphate (IP3)7. A ring-shaped molecule, such as cyclodextrin and cyclic-peptide, can be lodged in the pore lumen, where it acts as a molecular adaptor to discriminate between structurally similar drugs8 and chiral enantiomers9. In the attaching mode, the protein pore detects large proteins that are inaccessible to the pore10, distinguishes DNA segments that harbor a single nucleotide mismatch with the attached probing DNA11, and monitors enzyme-inhibitor interactions12. In addition to biosensing, engineered protein pores regulate polymer transport across the membrane13, switch the ion selectivity of the pore14, facilitate electroosmotic force-driven neutral compound transport through the pore15, and self-assemble into supramolecules16.

One of extensively participated programs that has attracted copious funding (see review articles17,18) is developing nanopore as the next-generation technology for DNA sequencing. When single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) is driven by the electrical field to thread through a pore, it will partially block the pore current19. If each base of the translocating DNA specifically participates in the current modulation, one can discriminate individual base species based on changes in the characteristic current and thus obtain an entire DNA sequence. Compared with ensemble sequencing technologies, the nanopore single-molecule approach is simpler and more cost-efficient. It does not need fluorescent labeling or amplification of the sample DNA, obviating the use of such enzymes as polymerase during detection. At a translocation speed of 1 μs per base, it would take merely hours to complete the sequencing of billions of bases in the mammalian genome. All these features fulfill the goal of the $1000 genome sequencing program being supported by the US National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI). Through intensive study of DNA or RNA translocation through nanopores, a wealth of important knowledge has been accumulated on how block characters, such as amplitudes and translocation duration, are modulated by the sequence, environmental factors including temperature and voltage, and chemical modification19,20,21,22,23,24,17,25,26,27.

Recently, new strategies for base recognition in the nanopore have been proposed and warrant particular attention. For example, a ssDNA attached to a “large head,” such as a hairpin 28 or streptavidin29, can be immobilized in an α-hemolysin pore. The pore therefore can distinguish between adenine and cytosine in different immobilized ssDNA species at the trans mouth of the β-barrel28, and the engineered pore can even discriminate all four DNA bases—A, T, G, and C—in immobilized DNA at the recognition sites in the pore lumen29. Instead of directly detecting DNA, a modified cyclodextrin, aminocyclodextrin, is covalently attached to the α-hemolysin pore as a molecular adaptor to discriminate all 4 unlabeled nucleotides in a mixture30. This conjugation is the first step toward a novel nanopore sequencing strategy, wherein if an exonuclease that is placed at the cis entry of the pore can digest target dsDNA into individual monophosphate nucleotides, these nucleotides will be sequentially discriminated by the immobilized cyclodextrin in the pore lumen30. A new approach is being devised to hybridize nanopores with single molecule fluorescence to detect so-called “converted” DNA, a DNA segment that consists of a series of 12-mer oligonucleotides that are concatenated in a specific order to encode the target DNA sequence31.

The nanopore is a very useful single-molecule instrument to investigate many molecular processes. Because the pore block is sensitive to the conformation, dimension, and orientation of molecules in the pore, the resulting conductance signatures can reveal intermediate states in a single-molecule reaction. For example, by attaching a reactant in the lumen of α-hemolysin, one can identify intermediates, uncover pathways, and quantify the kinetics of a multistep reaction at the single molecule level32.

Nanopores are also powerful tools for studying single DNA or RNA molecule unzipping19,33,34,35,28,36. When dsDNA that is attached to an ssDNA tail is trapped in the pore from the cis entry, the single-strand domain will enter the β-barrel, while the dsDNA domain is prevented from entering, because dsDNA (2.0 nm) is too wide for the cis entrance of the β-barrel (1.4 nm). At a given voltage, the single strand section will be pulled by the strong electric field in the β-barrel, leading to unzipping of the double strand section33,34,35,28,36.

Recently, nanopores have been used to measure the binding of enzymes to their DNA substrates. Because the enzyme protein can not be pushed into the pore, while the DNA can, one can remove the DNA from the bound protein. In this mode, the nanopore acts as a force microscope. The electrical field in the pore is used to examine the forces that regulate single-molecule enzyme-DNA interactions37,38. Expanded from this approach, a nanopore sensor can accurately identify DNA templates bound in the catalytic site of individual DNA polymerase molecules, and discriminate among unbound DNA, binary DNA/polymerase complexes, and ternary DNA/polymerase/deoxynucleotide triphosphate complexes39. Also the DNA polymerase-catalyzed extension of a single DNA can be monitored at single-nucleotide resolution based on the corresponding stepped increase in the nanopore current40.

Polypeptides have also been characterized using nanopore with regard to their folding states, backbone flexibility, structural stability, interaction with ligands, and enzymatic activity (see review article41). For example, by creating electrostatic traps at different sites within the α-hemolysin pore, one can enhance the translocation frequency and trapping time of a polypeptide that carries countercharges to the trap42, The enzymatic activity of proteases can be monitored by discriminating the nanopore blockage by the original polypeptide and the cleavage product43. By using synthetic nanopores, single-molecule protein unfolding process can be revealed44; protein and protein-antibody complex translocation can be discriminated45.

In addition to α-hemolysin, other protein pore systems have also been explored for sensing applications. One of representatives is channel-forming peptide gramicidin. As early as 1997, the engineered gramicidin has been incorporated into tethered lipid bilayer membrane as a biosensor for protein detection46, and modified gramicidin is also a single molecule probe to detect chemical reaction through monitoring the conductance change of the channel47. Recently, the porin MspA of Mycobacterium smegmatis48 have been demonstrated to be able to detect DNA translocation for the sequencing purpose.

3. Cation-regulated folding/unfolding of a single G-quadruplex aptamer in the nanopore

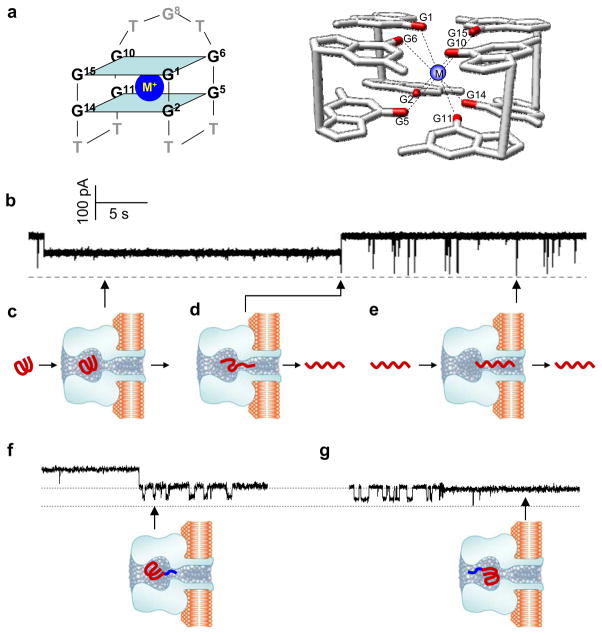

Recently we have encapsulated a single G-quadruplex aptamer in the nanocavity enclosed by the α-hemolysin pore, and demonstrated nanopore capability in understanding mechanisms of cation regulation on the folding and unfolding of single G-quadruplex 49,50. G-quadruplexes represent special four-stranded complexes folded by guanine-rich single-stranded DNA or RNA51,52,53. G-quadruplexes are rich in human telomeres, where these complexes play an important role in gene regulation54, thus are drug targets for treatment of cancer55. Engineered G-quadruplexes are ideal powerful biosensors56 and potent pharmaceuticals57 because they can bind to target proteins with high affinity in vitro. In nanobiotechnology, the synthetic G-quadruplexes are the unique building bricks of nano-structures58 and nanomachines59,60. We have utilized the αHL nanopore to investigate the folding and unfolding of the G-quadruplex formed by the thrombin-binding aptamer (TBA)49,50. This well-known 15-base short oligonucleotide (GGTTGGTGTGGTTGG)61 can fold into a two-tetrad, one-cation quadruplex in the presence of cations (Fig. 3a)61. Upon folding, the TBA G-quadruplex can efficiently inhibit the clotting activity of thrombin56. Due to the high affinity for thrombin, TBA has also been studied as a sophisticated biosensor element for protein detection62.

Figure 3.

Examining the folding and unfolding of a single G-quadruplex aptamer in the nanocavity of the αHL pore. (a) The sequence and structure of the G-quadruplex formed by the thrombin-binding aptamer (TBA) (left) and the two G-tetrad planes in the TBA G-quadruplex (right). The top tetrad is formed by guanines at the positions 1, 6, 10 and 15, and the bottom is formed by guanine 2, 5, 11 and 14. A cation in between is coordinated with eight carbonyls. The average cation-carbonyl distance is 2.86 Å. (b) Current block signal. (c) The long-lived block for capturing a single G-quadruplex in the nanocavity enclosed by the αHL pore. (d) The spike at the long block terminal produced by translocation of an unfolded G-quadruplex in the nanocavity. (e) Short-lived blocks formed by translocation of the linear form of TBA. (g) Characteristic blocks produced by tag-TBA (top) and the model showing the molecular location and position in the cavity (bottom). (h) Another type of block by tag-TBA (top) and the corresponding model showing the change in position of the molecule (bottom). This figure has been modified from references49,50.

We first discovered that a single TBA G-quadruplex can be arrested in the nanocavity domain enclosed by the αHL nanopore (Fig. 3c) by identification of the characteristic current signatures (Fig. 3b)49,50. There were two types of blocks identified for TBA added to the cis-side of the αHL pore: short-lived full blocks (~100 μs, Fig. 3b) and the long-lived half blocks (~10 seconds, Fig. 3b). The short blocks were attributed to the translocation of a linear form of TBA (unfolded) through the pore (Fig. 3e). The long blocks were produced by encapsulating a single G-quadruplex TBA in the nanocavity of the αHL pore (Fig. 3c)49. Multiple observations supported this conclusion. First, translocation of linear DNA never produces long blocks. Second, the dimension of the TBA G-quadruplex is ~2 nm, which is slightly more narrow than the cis-opening of the αHL pore but larger than the β-barrel (Fig. 2); therefore, the TBA G-quadruplex can enter the nanocavity but became trapped. Third, the volume of the TBA G-quadruplex is smaller than that of the nanocavity. When sequestered, the G-quadruplex did not occupy the entire space. Therefore, the unoccupied space could still form an ion pathway, leading to the partially-blocked conductance seen during a long block event (Fig. 3b). Finally, the long blocks could be eliminated by the addition of human α-thrombin to the TBA solution. This was due to the tight binding of TBA G-quadruplex in the solution to thrombin63, which would result in fewer free G-quadruplexes that could bind to the pore.

We also uncovered that the G-quadruplex can unfold in the nanopore49. The unfolding was proved to be a spontaneous process, because the long block duration is independent to the transmembrane voltage. After unfolding, the resulting linear DNA could rapidly leave the pore from the trans-opening by producing a spike-like, short block at the long block terminal (Fig. 3d). Because most long blocks were terminated with a spike block, it is expected that most trapped G-quadruplex will stay in the cavity until unfolding. The use of a tagged TBA allowed us to determine that the G-quadruplex was trapped at the bottom of the nanocavity and vibrated near the opening of the β-barrel (Fig. 3f and g). In summary, the main findings were: 1) a single G-quadruplex could be trapped within the nanopore; 2) the trapped G-quadruplex could spontaneously unfold into a linear conformation; 3) the characteristic current blocks (Fig. 3b) allowed for the discrimination of a single TBA molecule, either in the G-quadruplex form (Fig. 3c) or the linear form (Fig. 3e).

We used nanopore single molecule detection to find that the formation of the G-quadruplex is cation-selective50. The cation is sequestered between G-tetrads in coordination with eight carbonyls (Fig. 3a). The stability of the G-quadruplex is determined by the cation species. Understanding the folding/unfolding pathway is important for designing quadruplex applications, because a properly folded quadruplex is critical for molecular recognition. We developed an analytical approach to determine the equilibrium (Kf, Equation 1), unfolding (ku, Equation 2) and folding (kf, Equation 3) rate constants for the G-quadruplex from current signatures50:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

The occurrences of short-lived full blocks with the control DNA, Ctrl, and the linear form TBA, TBAL are represented by fCtrl and fTBAL in the above equations. The duration of the G-quadruplex-produced long blocks, τ, has been proven to be equal to the life of the G-quadruplex in solution. Through this analytical approach, the characteristic properties of G-quadruplex formation and regulation of cation-mediated folding/unfolding were identified50. For example, in the formation of the TBA G-quadruplex, K+, Ba2+ and NH4+ are cations that are favored over Cs+, Na+ and Li+. However, due to the strong non-specific DNA-cation interactions, Mg2+ and Ca2+ did not induce the formation of the G-quadruplex. The high formation capability of the K+-induced G-quadruplex was largely attributed to the slow unfolding reaction. It was also interesting to find that, although the Na+- and Li+-quadruplexes feature similar equilibrium properties, they undergo radically different pathways: the Na+-quadruplex folds and unfolds most rapidly, while the Li+-quadruplex is the slowest in both folding and unfolding. In addition, it was also revealed that the cation selectivity for the G-quadruplex formation is correlated with the volume of the G-quadruplex that varies with the cation species50.

These findings indicated that the nanopore is a useful single-molecule tools for enhancing our understanding of the ion-regulated properties and processes of oligonucleotides49,50. This would further enhance the understanding of the molecular recognition by aptamer-target complexes. The nanopore method is also applicable to other quadruplexes and their variants, including a variety of bio-relevant intramolecular quadruplexes, such as the i-motif (quadruplexes formed by cytidine-rich sequences) and chemically-modified quadruplexes with unique functionalities. When combined with site-directed nucleotide substitution, the nanopore method could be used to examine the contribution of each guanine to the quadruplex’s folding capability. Nanopores could also be used to determine the force involved in the interaction of G-quadruplex aptamers and their targets, such as thrombin and HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Finally, this research may facilitate the generation of new molecular species with tunable properties for nano-construction and the manufacture of biosensors.

4. Creation of nanopore sensor devices

Due to the vast breadth of nanopore applications, great efforts are being made to develop nanopore devices as the next generation of biosensors. These devices should be portable for independent storage and free transportation, while they should be independent, pluggable components that connect to other systems for real-time applications. For high-throughput applications, such as screening membrane protein-targeted drugs, detection should be performed on a microarray platform, in which each element contains a single responsive pore.

To create a robust, versatile device that functions with single pores, one significant challenge involves membrane stability; i.e., how to improve the fragility of the lipid bilayer membrane in which the protein pore is embedded. Issues that should be addressed also include the controllable insertion of protein pores into the lipid bilayer and device miniaturization. Here, we introduce several recent advances in the development of nanopore devices and compare their potential in various applications.

Portable and durable modular biochip containing single ion channels

There have been several strategies to stabilize the lipid membrane. For example, reducing the size of the aperture over which the lipid bilayer is formed may help to promote membrane stability. Through micro-fabrication, the aperture in silicon can be made as small as several micrometers in diameter64,65. The lipid bilayers can also be covalently tethered to a solid surface to form a solid-supported bilayer46,66. Peterson et al has reported a sandwiched lipid membrane generated by the painted method67, in which the bilayer was formed on a pre-cast gel slab and covered with another gel slab for double support68. With the sandwich structure, Schmidt et al improved the lipid membrane stability using an UV-triggered hydrogel in place of agarose69, and demonstrated a very efficient system that conjugates the headgroups of lipids in the membrane to the polyethylene glycol-based hydrogel during the hydrogel polymerization process to achieve extended lifetimes and resistance to mechanical perturbation.70

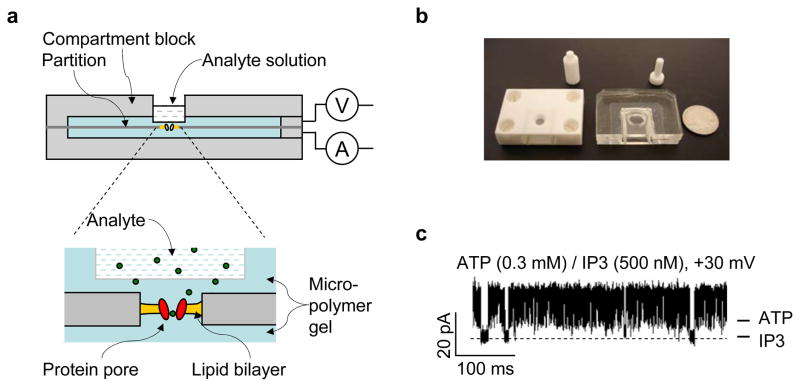

Both our laboratory71 and the Bayley group72 independently reported a portable, long-lived, modular biochip that integrates ion channels into a solidified membrane structure that is useful for both biomedical detection and membrane protein research. The core of the chip is a long-lived lipid membrane that is sandwiched between two air-proof agarose layers, with a single protein pore embedded in the membrane functions as the sensor element71. The chip can be fabricated in a multi-step process (Fig. 4a and b). First, the Teflon partition, with a 100 μm aperture in the center, is clipped between two compartment blocks to form two separate compartments. Second, a 1 M KCl solution containing 1.5% (w/v) ultra-low gelling temperature agarose is melted and cooled to room temperature. This agarose can remain in liquid form for days. Third, the lipid bilayer membrane is formed by a monolayer folding process73 and a single protein pore is inserted into the newly-formed membrane. Fourth, the entire chip is stored at 10 °C until the gel has solidified on both sides. Finally, the openings at the top of the two compartments are sealed by block lids to maintain the water content of the gel. The electrodes that are fixed in the block lids can connect with the gel to provide the membrane potential and receive the pico-Ampere current. For analyte detection, the cover of the sample cell in the the upper compartment is gently removed to allow for loading of the analyte solution (Fig. 4a). Due to the pore size of a 2% agarose gel (470 nm)74, analytes of various molecular weights can move through the gel to reach the protein pore embedded within the membrane for detection.

Figure 4.

Fabrication, prototype and use of the modular ion channel chip. (a) Assembly of the chip. The analyte can be added from the sample cell on the back of either compartment and delivered to the sensor element through agarose layered between the sample cell and the membrane. (b) A device prototype. (c) Signature blocks by the second messenger IP3 (500 nM) on the chip in a simulated intracellular conditions: 150 mM KCl, 2 mM ATP, 2.3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris, 0.3 mM ATP, pH 7.4. This figure has been modified from reference71.

The ion channel-integrated chip device is highly durable. The lipid membrane layered within the agarose gel consistently retains a high-sealing property (>10 GΩ in 1 M KCl) for a week, compared with several hours for conventional planar bilayers. The ion channel we tested, the viral potassium channel (Kcv), retained its function for as long as the membrane remained intact. The ion channel chip is also highly portable, which is an important characteristic required for practical application of this chip to biosensing and research. It can be repeatedly disconnected and reconnected to any device, such as an electrophysiology recording instrument. The disconnected chip is capable of independent storage, and can be transported from place to place. The unique portability and durability of the ion channel chip make it an independent, pluggable, modular biosensor that is useful for real-time sensing applications. For example, we have used the chip containing a single pore formed by M113R/T145R, an engineered a-hemolysin that can discriminate various phosphate compounds7, to detect nano-molar concentrations of the second messenger inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) in a mixture with high concentration of ATP (Fig. 4c). Any membrane protein can be used in the ion channel chip for single molecule detection, such as screening of enzymes or detection of glucose or neural transmitters. The areas of research where the chip will be of the greatest use include DNA and protein detection in genomics and proteomics, and screening for membrane protein-targeting pharmaceuticals. We speculate that the chip could be a valuable tool for investigating the long-term dynamics of membrane proteins, including ion channels, which otherwise are difficult to study by traditional electrophysiology techniques.

The chip features quick fabrication. The biosensor assembling time is less than 1 hour, including 5 minutes to form the bilayer, 10 minutes to insert single channels in the bilayer, and 15 minutes to solidify agarose at 10 °C. Besides the agarose, any polymer material, such as “smart polymer,” which solidifies at a specified pH or salt concentration and is permeable to ions and molecules without damaging bilayer membranes and proteins, could be used as a membrane support for the biosensor. The chip design can be improved with the help of powerful micro-/nano-fabrication tools including bioMEMS techniques. For example, due to the reduced diffusion in the gel, the neutral molecules (cyclodextrin) need to travel for half hour through a 2 mm thick gel slab from the bottom of the sample cell to the bilayer membrane (Fig. 4a), to reach the protein pore sensor in the membrane. This travel time can be shortened by thinning the gel layer to micrometers using micro-fabrication techniques. The volume of sample cell can be reduced to smaller than 1 μL to significantly reduce reagent consumption. As a modular device, it is possible to couple the ion channel chip with a micro-fluidic system to rapidly control the sample exchange. Because micro-patterned hydrogels have been created75,76, the chip is speculated to be able to provide a micro-array in future for high throughput screening with each array element containing a single stochastic sensor. The possibility of interfacing to a microfluidic system is enhanced by the recent technological advance that the protein pore-incorporated lipid membrane can be formed across a microfluidic channel77, and the possibility of indexing each individual ion channel on the array is supported by the ability to quickly transferring ion channels into membrane for single channel assay78.

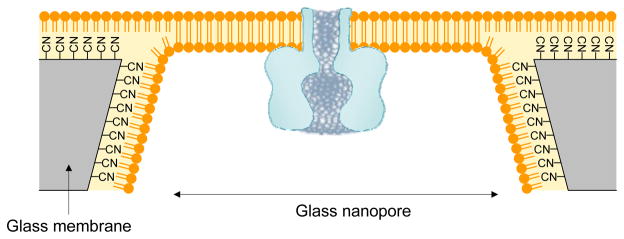

Stable suspended bilayer on a glass membrane nanopore

We have discussed that bilayers that are formed on an orifice as small as several micrometers are more stable64,65. Mayer et al. reported a supported lipid bilayer on a 2-μm aperture in a Teflon membrane79; Fertig et al. formed ion channels on a supported bilayer over a glass aperture on the scale of tens of micrometers80. One problem with the supported bilayer is the leak current that originates from a 1-nm-thick water layer between the polar head groups of the lipids and the glass surface. To overcome this problem, the White group and Cremer group generated a long-lived suspended lipid bilayer over a 100-nm glass nanopore (GNP) membrane for single channel recording81. This GNP-based bilayer can be fabricated using materials and instruments that are commonly available in most laboratories and do not require microlithographic fabrication techniques. The GNP can be fabricated by sealing an atomically sharp platinum wire in a glass capillary, polishing the capillary terminal until a nanometer wide platinum disk is exposed, and electrochemically etching the exposed platinum to produce a truncated cone-shaped nanopore in glass82. The platinum disk at the bottom of the pore serves as an electrode that is extremely useful for studying the control of molecular transport through the nanopore 83,84,85. As shown in Fig. 5, after GNP fabrication, the interior and exterior surfaces of the GNP are chemically modified with 3-cyanopropyldimethylchlorosilane to generate a sufficiently hydrophobic surface. When the lipid solution is applied, a monolayer of lipid molecules can be deposited, whereby the hydrophobic tails are oriented toward the glass surface, while the hydrophilic heads face the aqueous solution. Lipid monolayers that are deposited on the interior and exterior surfaces of the GNP will merge to form an exceptionally stable bilayer across the GNP.

Figure 5.

Incorporation of the protein pore in the lipid bilayer suspended over a glass nanopore (GNP) membrane81. The GNP is a single conical-shaped nanopore embedded in a 50 μm glass membrane. The fabrication of GNP membrane was described in the reference82. The interior and exterior surfaces of the GNP are coated with 3-cyanopropyldimethylchlorosilane to form a hydrophobic surface, which allows the formation of lipid monolayer on it. Lipid monolayers on the interior and exterior surfaces of the GNP will merge to form an exceptionally stable bilayer across the GNP.

The suspended bilayer can be formed over glass pores that range from tens of nanometers to several micrometers, with a seal resistance of 70 G. The 106-fold reduction in the bilayer area compared with conventional bilayers vastly improves mechanical and electrical stability. The GNP bilayer can persist for at least 2 weeks at room temperature and demonstrate voltage stability at 800 mV. It has been successfully used for stochastic sensing of small molecules and can perform continuous detection for at least 24 hours without further optimization. The bilayer on the GNP is also refractory to mechanical disruptions and can be transferred between different analyte solutions, during which the functioning protein pore sensing unit remains in place.

An intriguing property of the GNP bilayer is that single ion channels can be inserted and removed from the bilayer as desired by applying small pressure gradients across the lipid bilayers. This capacity is critical for the directed insertion of proteins at different positions on an array of ion channel biosensors. It is reasonable to speculate that many independent GNP bilayer-based ion channel probes can be arranged into an array, which can be used in high-throughput biosensing applications.

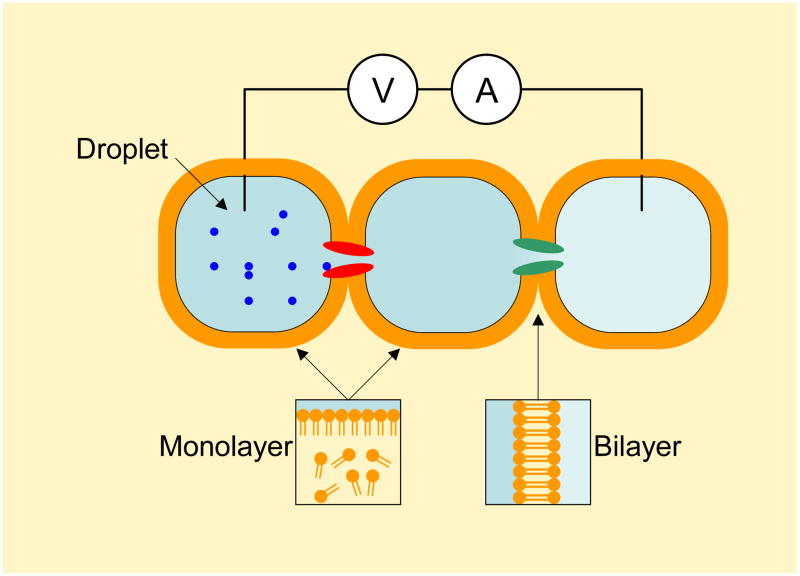

Network and parallel detections using droplet interface bilayers

All of the methods that we have described form bilayers in the aqueous phase. Nevertheless, the Bayley group and Wallace group have pursued protein pore research and applications on a bilayer that is formed in the oil phase, called the droplet interface bilayer (DIB) (see review article86). The similar concepts to DIB have been reported earlier87,88. The DIB is formed on the interface between two aqueous droplets in the lipid solution. As shown in Fig. 6, when a droplet is created by pipetting the aqueous solution into the lipid solution, a lipid monolayer will self-assemble on the droplet-oil interface; the hydrophilic head of the lipid molecules orient themselves toward the aqueous solution in the droplet, and the hydrophobic tails face the lipid solution. When two droplets are manipulated to contact, their surface lipid monolayers will hybridize into a bilayer on the interface—i.e., the DIB. The channel proteins in the droplet solution can be inserted into the DIB, and the electrical properties of the DIB and channel proteins can be recorded through a pair of Ag/AgCl electrodes that are inserted into the droplets.

Figure 6.

Droplet interface bilayer (DIB) and DIB network. The DIB is formed on the interface between two aqueous droplets in the lipid solution. Firstly, a liquid droplet is created by dipping a drop of aqueous solution into the lipid solution, with a lipid monolayer formed on the droplet-oil interface. Then two droplets are manipulated to contact each other and their surface lipid monolayers will hybridize into a bilayer on the interface, DIB. Various channel proteins in the droplet solution can be incorporated into the DIB, and recorded using two Ag/AgCl electrodes, each of which is inserted into a droplet. A very useful property of DIB is the ability to form network, in which each DIB contains a responsive protein channel89. The DIB network acts as a molecular device to simulate functions of semiconductor circuits, such as half-wave rectification and full-wave rectification90. The droplets can also form arrays for parallel screening ion channel blocks91.

The DIB demonstrates superior stability, possessing a lifetime that ranges from days to weeks89. Further, the positions of droplets can be easily controlled with a micromanipulator, such that many droplets can be assembled into a DIB network (Fig. 6), in which each DIB contains a protein channel that is responsive to a specific stimulus, including light, ligands, pH, ion species, and voltage89. Such a responsive DIB network can functions as a microbattery89 and circuit elements (e.g., resistor, capacitor, and diode), rendering the entire droplet network a molecular device that simulates the functions of semiconductor circuits, such as half-wave rectification and full-wave rectification90.

The droplets can form arrays for parallel screening applications91. In this configuration, a probing droplet that contains the ion channels is manipulated to contact each blocker droplet (contains a blocker species) in the array to examine the blocking effect. After a blocker is tested, the droplet is disconnected from that blocker droplet and connected to another droplet containing another blocker to test the blocker effect. Therefore, it is possible to build a DIB automation line for rapid parallel screening of blockers. Compared with many ensemble assay-based automatic patch clamp techniques that have been developed to increase ion channel screening efficiency92, single channel recording can provide detailed information on the blocking mechanism, such as rate constants for the binding and release of blockers from the target. In addition, the minute volume of droplets (as low as 100 nL) allows for efficient use of expensive reagents. The small volume also transforms the droplet into a nanoreactor93. For example, the channel proteins can be synthesized by in vitro transcription and translation (IVTT) in the droplet, and the pore-forming ability of the product can be immediately examined with the DIB86.

Droplet-based bilayers can also be created on the interface between an aqueous droplet and an agarose substrate in the oil phase, called droplet-on-hydrogel bilayers (DHBs)94,95. Because thin agarose substrates can be developed (down to the submicrometer level), the bilayer on which they lie can be accessible to the total internal reflection fluorescence microscope (TIRF), a platform that combines single molecule fluorescence and single-channel recording to study single molecule diffusion and assembly in the bilayer94,95. By moving the droplet along the hydrogel surface, the DHB can also directly scan the gel to characterize channel proteins after electrophoresis, without the need for protein extraction and reconstitution94.

The goal of all the methods described herein is creating robust, single protein pore sensors. In real-time applications, however, the currently used instruments and peripherals for electrical detection are bulky and should be miniaturized. Many labs use precise instruments, such as the Axopatch (Molecular Devices Ins) to record pico-Ampere single channel currents and Faraday cages to isolate noise interference. Their miniaturization has not been widely reported in academic journals but is expected to be realized with the aid of electrical engineers and mechanical engineers in the industry. For example, to simplify the recording instrument, functions in a traditional electrophysiology instrument that are unnecessary for biosensing applications can be removed, and the core module—current amplification—should be retained. At least a module should be added that can automatically filter the 50/60 Hz electric noise, so that detection is less dependent on the Faraday cage.

5. From protein nanopores to synthetic nanopores

The nanopores assembled by protein ion channels are unique because they allow for the attachment of a receptor in the lumen through structure-directed genetic engineering and chemical modification96. The receptor recognizes the specific target, making the protein pore highly selective. In addition, due to the fixed pore size, the results from protein nanopores are highly reproducible. Nanopores can also be created on solid supports using various fashion micro- and nano-technologies97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108, called synthetic nanopores. These solid-state nanopores, by determining ion currents and forces as molecules pass through, can help to investigate a wide range of phenomena involving DNA, RNA and proteins, and provide versatile single-molecule tools for biophysics and biotechnology (see review articles109,110).

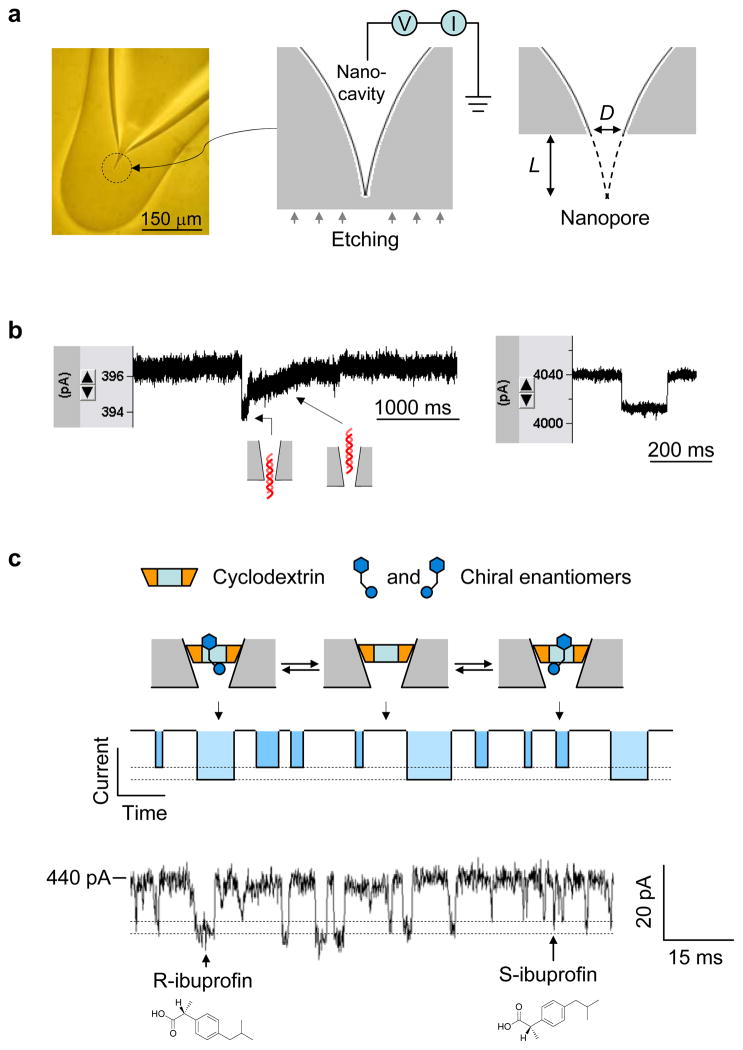

Although synthetic nanopores are not the focus of this review, we will provide a brief overview of several representative examples, and compare synthetic nanopores with bio-nanopores. A solid nanopore can be “sculpted” in the Si3N4 membrane97 with a focused ion beam or lithographed with a high-energy electron beam from a transmission electron microscope101,111,102,103. Another well-established method for creating a single nanopore involves ion-track etching on a polymer film98,99,112,113. Glass capillaries can be pulled into nanopipettes for controlled delivery, ion conductance microscopes and nanosensors114,115,116. Glass nanopore electrodes have also been created from platinum nanoelectrodes coated with a glass membrane for use in a variety of nano-electrochemistry studies117. Very recently, Zhang et al reported the formation of a size-controllable glass nanochannel (down to 5 nm in diameter) from micropipette with demonstrated ability of sensing and molecular transport118. Our group have developed a glass nanopore-terminating probe by externally penetrating an enclosed nanocavity in the terminal end of a capillary pipette25. The fabrication is illustrated in Fig. 7a. This nanopore can be fashioned to accommodate almost any molecular complex under investigation, and features several distinguishable benefits: ease of fabrication by virtually any laboratory at low cost; precise manipulatable pore size, from one to several hundred nanometers; experimentally verified ability to capture single molecules and perform stochastic sensing; reduced electrical noise; bio-friendly surface engineering; and the ability to function as a probe platform for in situ and high throughput applications. The pore sizes equivalent to a single molecule have been verified by translocation of molecules of known sizes, including dsDNA (~2 nm) (Fig. 7b), gold nanoparticles (~10 nm) and ring-shaped cyclodextrin (~1.5 nm). Particularly when the pore size is comparable to dsDNA, the DNA translocation speed is slowed down and translocation steps can be revealed from the block type (Fig. 7b left), which is different from that for DNA translocation in a wider pore (Fig. 7b right). We can also fabricate 1-nm glass nanopore so that it can trap a single cyclodextrin in the lumen. The trapped cyclodextrin functions in a similar way to that in the protein pore: acting as a molecular adapter to identify small chemicals in the mixture8. For example, we have used the 1-nm nanopore with a trapped β-cyclodextrin to discriminate chiral enantiomers on the basis of their characteristic block signatures25 (Fig. 7c).

Figure 7.

Glass nanopore-terminated probe and single molecule manipulation. (a) The glass nanopore is fabricated by sealing the micropipette terminal to enclose a nanocavity, followed by external etching the glass terminal with electrical monitoring to perforate the nanocavity with controllable pore size. (b) Current blocks showing translocation of 1 kbp dsDNA through a 2 nm nanopore (left) and a 7 nm pore (right) in 1 M NaCl and recorded +100 mV. When the pore size is comparable to dsDNA, the DNA translocation speed is slowed down and translocation steps can be revealed from the block type (left), which is different from that for DNA translocation in a wider pore (right). (c) Single molecule discrimination of chiral enantiomers by the cyclodextrin (1.5 nm) trapped in the 1 nm nanopore. The interaction of chiral compounds with cyclodextrin can be separated from their block durations and current amplitudes. The current trace showed the binding of individual enantiomers of ibuprofen to the trapped β-cyclodextrin in the nanopore. The solution contained the mixture of 100 μM R-(−)-ibuprofen and 100 μM S-(+)-ibuprofen. The current block levels by R- and S-ibuprofen were marked with dash lines25.

A comprehensive comparison between protein pores and synthetic nanopores, as well as their perspectives can be found in Martin and Siwy’s review article110. Compared with protein pores, synthetic nanopores offer higher stability, flexible pore sizes, and array platforms. These greatly expand the potential of nanopore applications in biotechnology and the life sciences119,120,121,122. Synthetic nanopores do not require special processing for stabilization, and can detect at a potential as high as several volts. The flexible and adjustable pore sizes make them suitable to target molecules of different dimensions. Moreover, fabrication of synthetic nanopore is suitable to laboratories that do not work with genetic engineering techniques, and the pore materials are diverse, such as Si, Si4N3 and glass, all of which allow for rich surface modification. On the other hand, however, the greater stability of synthetic nanopores comes with reduced selectivity. Single molecules, such as DNA or proteins, are measured during translocation through the pore, but any molecules smaller than the nanopore also can generate a transient pore block. This low specificity limits the ability to identify and isolate molecular processes with translocation-based detections110. This may be overcome by coating a layer of probing molecules to the nanopore 103,123,124,112,125 to force specific targeting. For example, DNA transport was enhanced in nanopores modified with an complementary oligonucleotide probe 126,103; a biosensing nanopore coated with antibodies can detect target proteins such as ricin by measuring the time spent for fully blocking the poreconductance112; and recently, a significant step was made toward functionalization at selected points in a solid nanopore124. However, these methods have thus far failed to detect the binding of individual target molecules, and it remains impossible to distinguish between blocks produced by binding and those generated by translocation.

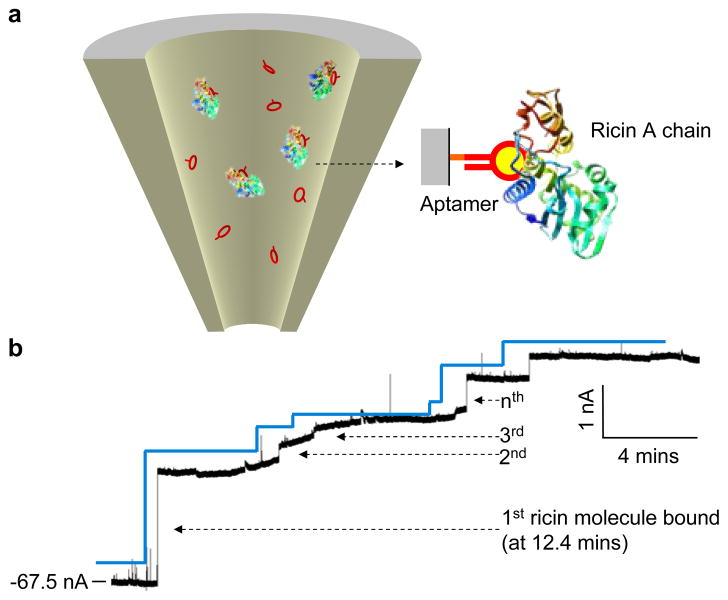

To overcome challenges of synthetic nanopores, we recently developed an aptamer-encoded nanopore that integrates sophisticated aptamers and the glass nanopore technique26 (Fig. 8). Aptamers, or “synthesized antibodies,” are short DNA or RNA segments that are created by in vitro evolution127,128. Despite their diminutive size, aptamers recognize and specifically bind broad species of ligands, such as peptides129, proteins130,131,132, and pathogenic targets133,134,135, with high affinity (nano- to picomolar)136 that matches or exceeds that of their true antibody counterparts137. Because aptamers are much smaller than their targets, when they are bound by the target, the target signal is pronounced, allowing one to identify single molecules that are sequentially captured by the immobilized aptamer. Therefore, aptamers outperform antibodies with regard to single-molecule detection in nanopores. We have applied aptamer-encoded nanopores to quantify Immunoglobulin E (IgE) and the bioterrorist agent ricin in the solution at single molecule resolution26 (Fig. 8). The sensing signal comprises a series of stepwise, discrete current blocks that are attributed to individual target molecules sequentially captured by the immobilized aptamer in the nanopore. The aptamer-encoded nanopore is advantageous over other systems. Firstly, it performs rapid label-free target (ricin) detection with high sensitive and selectivity. Secondly, the nanopore electrical detection is much simpler than other optical and mass spectroscopic methods, making it more suitable to real-time detection. The digital signal produced by individual ricin molecules (stepwise blocks, Fig. 8) distinguishes them from the analog background signal. This is particularly useful in real-time detections, where, when the background current dynamically drifts or fluctuates with the environment, one can still identify discrete single molecule events, thus greatly enhancing the signal/noise ratio. Thirdly, the aptamer-encoded nanopore can distinguish between transient current blockades caused by non-specific molecules passing through the nanopore and much longer blocks resulting from the target binding. We have focused this new nanopore sensor technique on bioterrorist materials because of their importance to homeland security, but this invention is potential for broad applications. Aptamer-based nanopore sensors can be used for environmental monitoring, detecting pollution or contaminating materials in water. It can be applied to medical diagnoses, quantifying biomarkers in blood samples. It depends on the aptamer development. If the aptamer is ready, one can use it for just about anything. Using aptamers is also advantageous because they are more durable than most protein receptors, resisting most denaturing and degrading conditions, including immobilization; yet, they are simpler to synthesize, modify, and immobilize using low-cost methods. The affinity and specificity of aptamer-target interactions can also be fine-tuned through rational design or molecular evolution. Having already created a nanopore detector for ricin, we now aims to devise a nanopore sensor that will use an aptamer to detect anthrax spores—well known as a bioterrorist threat. Scientists already have developed an anthrax aptamer, paving the way for a nanopore sensor.

Figure 8.

Single-molecule detection of bioterrorist agent ricin with an aptamer-encoded nanopore. The ricin A chain-targeted aptamer was immobilized on the inner surface of the glass nanopore. The current trace showed a 56 nm aptamer-encoded nanopore in the presence of 100 nM ricin A-chain protein in the external solution (−100 mV). The stepwise current blocks are attributed to the sequential binding of single ricin molecules to the immobilized aptamers in the nanopore26.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported by NSF 0546165, NIH GM079613, and University of Missouri Startup Fund and Research Board. This investigation was conducted in a facility constructed with support from Research Facilities Improvement Program Grant C06-RR-016489-01 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health.

Reference List

- 1.B. Hille, 2001, 3rd,

- 2.Bayley H, Cremer PS. Nature. 2001;413:226–230. doi: 10.1038/35093038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song LZ, Hobaugh MR, Shustak C, Cheley S, Bayley H, Gouaux JE. Science. 1996;274:1859–1866. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5294.1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayley H, Cremer PS. Nature. 2001;413:226–230. doi: 10.1038/35093038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayley H, Jayasinghe L. Molecular Membrane Biology. 2004;21:209–220. doi: 10.1080/09687680410001716853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braha O, Gu LQ, Zhou L, Lu XF, Cheley S, Bayley H. Nature Biotechnology. 2000;18:1005–1007. doi: 10.1038/79275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheley S, Gu LQ, Bayley H. Chemistry & Biology. 2002;9:829–838. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00172-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gu LQ, Braha O, Conlan S, Cheley S, Bayley H. Nature. 1999;398:686–690. doi: 10.1038/19491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang XF, Cheley S, Guan XY, Bayley H. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128:10684–10685. doi: 10.1021/ja063485l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Movileanu L, Howorka S, Braha O, Bayley H. Nature Biotechnology. 2000;18:1091–1095. doi: 10.1038/80295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howorka S, Cheley S, Bayley H. Nature Biotechnology. 2001;19:636–639. doi: 10.1038/90236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie H, Braha O, Gu LQ, Cheley S, Bayley H. Chem Biol. 2005;12:109–210. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bezrukov SM, Vodyanoy I, Parsegian VA. Nature. 1994;370:279–281. doi: 10.1038/370279a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu LQ, Dalla Serra M, Vincent JB, Vigh G, Cheley S, Braha O, Bayley H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3959–3964. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.3959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gu LQ, Cheley S, Bayley H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15498–15503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2531778100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu LQ, Cheley S, Bayley H. Science. 2001;291:636–640. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5504.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Branton D, Deamer DW, Marziali A, Bayley H, Benner SA, Butler T, Di Ventra M, Garaj S, Hibbs A, Huang X, Jovanovich SB, Krstic PS, Lindsay S, Ling XS, Mastrangelo CH, Meller A, Oliver JS, Pershin YV, Ramsey JM, Riehn R, Soni GV, Tabard-Cossa V, Wanunu M, Wiggin M, Schloss JA. Nature Biotechnology. 2008;26:1146–1153. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bayley H. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2006;10:628–637. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kasianowicz JJ, Brandin E, Branton D, Deamer DW. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13770–13773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akeson M, Branton D, Kasianowicz JJ, Brandin E, Deamer DW. Biophys J. 1999;77:3227–3233. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77153-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meller A, Nivon L, Brandin E, Golovchenko J, Branton D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1079–1084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meller A, Nivon L, Branton D. Phys Rev Lett. 2001;86:3435–3438. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.3435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deamer DW, Branton D. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35:817–825. doi: 10.1021/ar000138m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakane J, Akeson M, Marziali A. J Phys Condens Matter. 2003:15. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao C, Ding S, Tan Q, Gu LQ. Anal Chem. 2009;81:80–86. doi: 10.1021/ac802348r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding S, Gao C, Gu LQ. Anal Chem. 2009;81:6649–6655. doi: 10.1021/ac9006705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitchell N, Howorka S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:5565–5568. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashkenasy N, Sanchez-Quesada J, Bayley H, Ghadiri MR. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition. 2005;44:1401–1404. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stoddart D, Heron AJ, Mikhailova E, Maglia G, Bayley H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7702–7707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901054106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clarke J, Wu HC, Jayasinghe L, Patel A, Reid S, Bayley H. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:265–270. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soni GV, Meller A. Clin Chem. 2007;53:1996–2001. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.091231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luchian T, Shin SH, Bayley H. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition. 2003;42:3766–3771. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vercoutere W, Winters-Hilt S, Olsen H, Deamer D, Haussler D, Akeson M. Nature Biotechnology. 2001;19:248–252. doi: 10.1038/85696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mathe J, Visram H, Viasnoff V, Rabin Y, Meller A. Biophys J. 2004;87:3205–3212. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.047274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakane J, Wiggin M, Marziali A. Biophys J. 2004;87:615–621. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.040212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Astier Y, Braha O, Bayley H. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128:1705–1710. doi: 10.1021/ja057123+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hornblower B, Coombs A, Whitaker RD, Kolomeisky A, Picone SJ, Meller A, Akeson M. Nature Methods. 2007;4:315–317. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tropini C, Marziali A. Biophys J. 2007;92:1632–1637. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.094060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benner S, Chen RJA, Wilson NA, Abu-Shumays R, Hurt N, Lieberman KR, Deamer DW, Dunbar WB, Akeson M. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2:718–724. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cockroft SL, Chu J, Amorin M, Ghadiri MR. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2008;130:818–820. doi: 10.1021/ja077082c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Movileanu L. Trends Biotechnol. 2009;27:333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mohammad MM, Prakash S, Matouschek A, Movileanu L. J AM CHEM SOC. 2008;130:4081–4088. doi: 10.1021/ja710787a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao Q, De Zoysa RSS, Wang D, Jayawardhana DA, Guan X. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2009;131:6324–6325. doi: 10.1021/ja9004893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Talaga DS, Li J. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2009;131:9287–9297. doi: 10.1021/ja901088b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sexton LT, Horne LP, Sherrill SA, Bishop GW, Baker LA, Martin CR. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129:13144–13152. doi: 10.1021/ja0739943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cornell BA, BraachMaksvytis VLB, King LG, Osman PDJ, Raguse B, Wieczorek L, Pace RJ. Nature. 1997;387:580–583. doi: 10.1038/42432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Capone R, Blake S, Restrepo MR, Yang J, Mayer M. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129:9737–9745. doi: 10.1021/ja0711819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Butler TZ, Pavlenok M, Derrington IM, Niederweis M, Gundlach JH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20647–20652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807514106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shim JW, Gu LQ. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:8354–8360. doi: 10.1021/jp0775911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shim JW, Tan Q, Gu LQ. Nucleic Acids Research. 2009;37:972–982. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burge S, Parkinson GN, Hazel P, Todd AK, Neidle S. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34:5402–5415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hardin CC, Perry AG, White K. Biopolymers. 2000;56:147–194. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2000/2001)56:3<147::AID-BIP10011>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sen D, Gilbert W. Nature. 1988;334:364–366. doi: 10.1038/334364a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arthanari H, Bolton PH. Chemistry & Biology. 2001;8:221–230. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Neidle S, Parkinson G. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2002;1:383–393. doi: 10.1038/nrd793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bock LC, Griffin LC, Latham JA, Vermaas EH, Toole JJ. Nature. 1992;355:564–566. doi: 10.1038/355564a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tang ZW, Shangguan D, Wang KM, Shi H, Sefah K, Mallikratchy P, Chen HW, Li Y, Tan WH. Anal Chem. 2007;79:4900–4907. doi: 10.1021/ac070189y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davis JT, Spada GP. Chemical Society Reviews. 2007;36:296–313. doi: 10.1039/b600282j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alberti P, Mergny JL. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:1569–1573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0335459100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li JWJ, Tan WH. Nano Letters. 2002;2:315–318. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marathias VM, Bolton PH. Nucleic Acids Research. 2000;28:1969–1977. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.9.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Heyduk T, Heyduk E. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:171–176. doi: 10.1038/nbt0202-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bock LC, Griffin LC, Latham JA, Vermaas EH, Toole JJ. Nature. 1992;355:564–566. doi: 10.1038/355564a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fertig N, Blick RH, Behrends JC. Biophys J. 2002;82:3056–3062. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75646-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sackmann E. Science. 1996;271:43–48. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5245.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Knoll W, Frank CW, Heibel C, Naumann R, Offenhausser A, Ruhe J, Schmidt EK, Shen WW, Sinner A. J Biotechnol. 2000;74:137–58. doi: 10.1016/s1389-0352(00)00012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mueller P, Rudin DO, Tien HT, Wescott WC. Nature. 1962;194:979–80. doi: 10.1038/194979a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Costello RF, Peterson IP, Heptinstall J, Byrne NG, Miller LS. Advanced Materials for Optics and Electronics. 1998;8:47–52. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jeon TJ, Malmstadt N, Schmidt JJ. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128:42–43. doi: 10.1021/ja056901v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Malmstadt N, Jeon TJ, Schmidt JJ. Adv Mater. 2008;20:84–89. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shim JW, Gu LQ. Anal Chem. 2007;79:2207–2213. doi: 10.1021/ac0614285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kang XF, Cheley S, Rice-Ficht AC, Bayley H. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129:4701–4705. doi: 10.1021/ja068654g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Montal M, Mueller P. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1972;69:3561–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.12.3561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pluen A, Netti PA, Jain RK, Berk DA. Biophys J. 1999;77:542–552. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)76911-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mayer M, Yang J, Gitlin I, Gracias DH, Whitesides GM. Proteomics. 2004;4:2366–2376. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Klajn R, Fialkowski M, Bensemann IT, Bitner A, Campbell CJ, Bishop K, Smoukov S, Grzybowski BA. Nature Materials. 2004;3:729–735. doi: 10.1038/nmat1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Malmstadt N, Nash MA, Purnell RF, Schmidt JJ. Nano Letters. 2006;6:1961–1965. doi: 10.1021/nl0611034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Holden MA, Jayasinghe L, Daltrop O, Mason A, Bayley H. Nature Chemical Biology. 2006;2:314–318. doi: 10.1038/nchembio793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mayer M, Kriebel JK, Tosteson MT, Whitesides GM. Biophys J. 2003;85:2684–2695. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74691-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fertig N, Klau M, George M, Blick RH, Behrends JC. Appl Phys Lett. 2002;81:4865–4867. [Google Scholar]

- 81.White RJ, Ervin EN, Yang T, Chen X, Daniel S, Cremer PS, White HS. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11766–11775. doi: 10.1021/ja073174q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang B, Galusha J, Shiozawa PG, Wang G, Bergren AJ, Jones RM, White RJ, Ervin EN, Cauley CC, White HS. Anal Chem. 2007;79:4778–4787. doi: 10.1021/ac070609j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jun HS, Kim J, Geun SC, Nam H, White RJ, White HS, Brown RB. Anal Chem. 2007;79:3568–3574. doi: 10.1021/ac061984z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang G, Bohaty AK, Zharov I, White HS. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128:13553–13558. doi: 10.1021/ja064274j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang B, Zhang Y, White HS. Anal Chem. 2006;78:477–483. doi: 10.1021/ac051330a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bayley H, Cronin B, Heron A, Holden MA, Hwang WL, Syeda R, Thompson J, Wallace M. Mol Biosyst. 2008;4:1191–1208. doi: 10.1039/b808893d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tsofina LM, Liberman EA, Babakov AV. Nature. 1966;212:681–683. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Funakoshi K, Suzuki H, Takeuchi S. Anal Chem. 2006;78:8169–8174. doi: 10.1021/ac0613479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Holden MA, Needham D, Bayley H. J AM CHEM SOC. 2007;129:8650–8655. doi: 10.1021/ja072292a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Maglia G, Heron AJ, Hwang WL, Holden MA, Mikhailova E, Li Q, Cheley S, Bayley H. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:437–440. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Syeda R, Holden MA, Hwang WL, Bayley H. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2008;130:15543–15548. doi: 10.1021/ja804968g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dunlop J, Bowlby M, Peri R, Vasilyev D, Arias R. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:358–368. doi: 10.1038/nrd2552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Aharoni A, Griffiths AD, Tawfik DS. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2005;9:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Heron AJ, Thompson JR, Mason AE, Wallace MI. J AM CHEM SOC. 2007;129:16042–16047. doi: 10.1021/ja075715h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Thompson JR, Heron AJ, Santoso Y, Wallace MI. Nano Lett. 2007;7:3875–3878. doi: 10.1021/nl071943y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bayley H, Jayasinghe L. Molecular Membrane Biology. 2004;21:209–220. doi: 10.1080/09687680410001716853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Li J, Stein D, McMullan C, Branton D, Aziz MJ, Golovchenko JA. Nature. 2001;412:166–169. doi: 10.1038/35084037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Siwy Z, Gu Y, Spohr HA, Baur D, Wolf-Reber A, Spohr R, Apel P, Korchev YE. Europhysics Letters. 2002;60:349–355. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Harrell CC, Lee SB, Martin CR. Anal Chem. 2003;75:6861–6867. doi: 10.1021/ac034602n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Storm AJ, Chen JH, Ling XS, Zandbergen HW, Dekker C. Nature Materials. 2003;2:537–540. doi: 10.1038/nmat941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ho C, Qiao R, Heng JB, Chatterjee A, Timp RJ, Aluru NR, Timp G. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10445–10450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500796102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kim MJ, Wanunu M, Bell DC, Meller A. Adv Mater. 2006;18:3149. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Iqbal SM, Akin D, Bashir R. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2:243–248. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Karhanek M, Kemp JT, Pourmand N, Davis RW, Webb CD. Nano Lett. 2005;5:403–407. doi: 10.1021/nl0480464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Shao Y, Mirkin MV. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1997;119:8103–8104. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wei C, Bard AJ, Feldberg SW. Analytical Chemistry. 1997;69:4627–4633. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ying LM, Bruckbauer A, Rothery AM, Korchev YE, Klenerman D. Analytical Chemistry. 2002;74:1380–1385. doi: 10.1021/ac015674m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zhang B, Zhang YH, White HS. Analytical Chemistry. 2004;76:6229–6238. doi: 10.1021/ac049288r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dekker C. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2:209–215. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Martin CR, Siwy ZS. Science. 2007;317:331–332. doi: 10.1126/science.1146126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Storm AJ, Chen JH, Ling XS, Zandbergen HW, Dekker C. Nature Materials. 2003;2:537–540. doi: 10.1038/nmat941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Siwy Z, Trofin L, Kohli P, Baker LA, Trautmann C, Martin CR. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2005;127:5000–5001. doi: 10.1021/ja043910f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Powell MR, Sullivan M, Vlassiouk I, Constantin D, Sudre O, Martens CC, Eisenberg RS, Siwy ZS. Nat Nanotechnol. 2008;3:51–57. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Klenerman D, Korchev Y. Nanomedicine. 2006;1:107–114. doi: 10.2217/17435889.1.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Piper JD, Clarke RW, Korchev YE, Ying LM, Klenerman D. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128:16462–16463. doi: 10.1021/ja0650899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ying LM, Bruckbauer A, Rothery AM, Korchev YE, Klenerman D. Analytical Chemistry. 2002;74:1380–1385. doi: 10.1021/ac015674m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.White RJ, Zhang B, Daniel S, Tang JM, Ervin EN, Cremer PS, White HS. Langmuir. 2006;22:10777–10783. doi: 10.1021/la061457a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zhang B, Wood M, Lee H. Anal Chem. 2009;81:5541–5548. doi: 10.1021/ac9009148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Saleh OA, Sohn LL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:820–824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337563100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Uram JD, Ke K, Hunt AJ, Mayer M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:2281–2285. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sexton LT, Horne LP, Sherrill SA, Bishop GW, Baker LA, Martin CR. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129:13144–13152. doi: 10.1021/ja0739943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.McNally B, Wanunu M, Meller A. Nano Letters. 2008;8:3418–3422. doi: 10.1021/nl802218f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Kohli P, Harrell CC, Cao ZH, Gasparac R, Tan WH, Martin CR. Science. 2004;305:984–986. doi: 10.1126/science.1100024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Nilsson J, Lee JRI, Ratto TV, tant SE. Adv Mater. 2006;18:427–431. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Wanunu M, Meller A. Nano Letters. 2007;7:1580–1585. doi: 10.1021/nl070462b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kohli P, Harrell CC, Cao ZH, Gasparac R, Tan WH, Martin CR. Science. 2004;305:984–986. doi: 10.1126/science.1100024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ellington AD, Szostak JW. Nature. 1990;346:818–822. doi: 10.1038/346818a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Tuerk C, Gold L. Science. 1990;249:505–510. doi: 10.1126/science.2200121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Baskerville S, Zapp M, Ellington AD. Journal of Virology. 1999;73:4962–4971. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.4962-4971.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Klug SJ, Huttenhofer A, Famulok M. Rna-a Publication of the Rna Society. 1999;5:1180–1190. doi: 10.1017/s135583829999088x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wen JD, Gray DM. Nucleic Acids Research. 2004:32. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Xiao Y, Lubin AA, Heeger AJ, Plaxco KW. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005;44:5456–5459. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Jeon SH, Kayhan B, Ben-Yedidia T, Arnon R. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:48410–48419. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.de Soultrait VR, Lozach PY, Altmeyer R, Tarrago-Litvak L, Litvak S, Andreola ML. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2002;324:195–203. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Jing NJ, Rando RF, Pommier Y, Hogan ME. Biochemistry. 1997;36:12498–12505. doi: 10.1021/bi962798y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Jenison RD, Gill SC, Pardi A, Polisky B. Science. 1994;263:1425–1429. doi: 10.1126/science.7510417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Jenison RD, Gill SC, Pardi A, Polisky B. Science. 1994;263:1425–1429. doi: 10.1126/science.7510417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]