Abstract

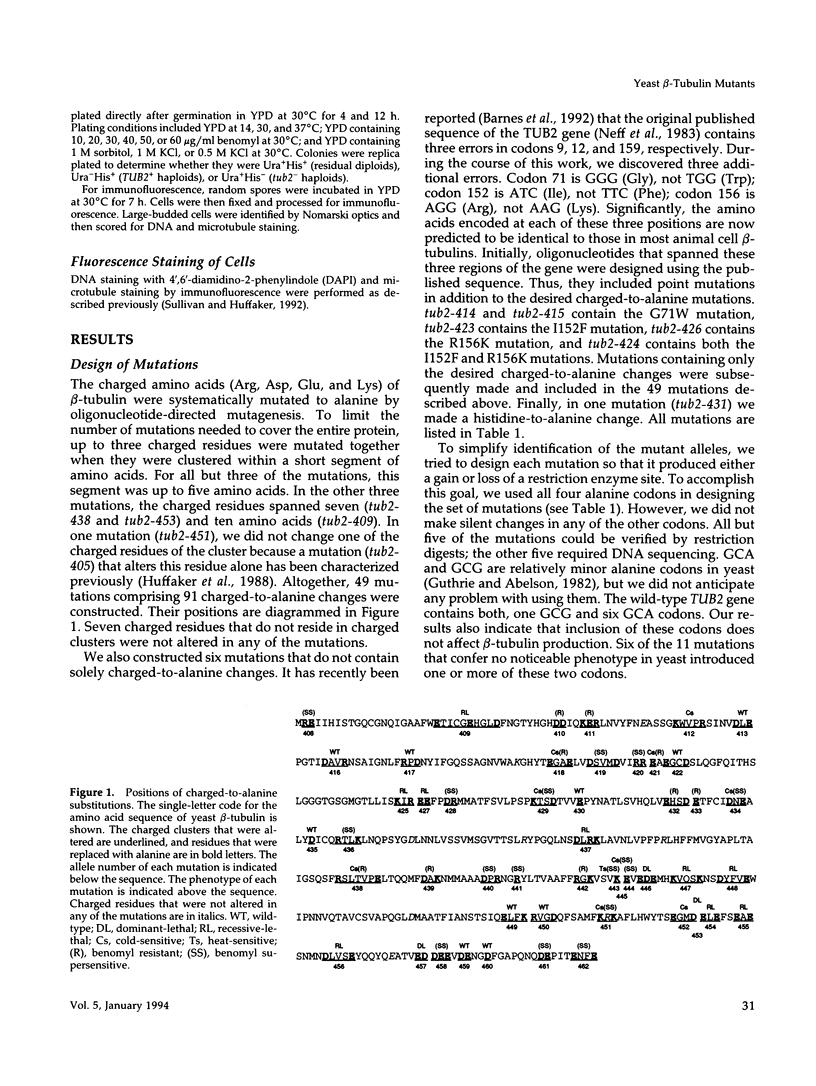

A systematic strategy was used to create a synoptic set of mutations that are distributed throughout the single beta-tubulin gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Clusters of charged amino acids were targeted for mutagenesis and converted to alanine to maximize alterations on the protein's surface and minimize alterations that affect protein folding. Of the 55 mutations we constructed, three confer dominant-lethality, 11 confer recessive-lethality, 10 confer cold-sensitivity, one confers heat-sensitivity, and 27 confer altered resistance to benomyl. Only 11 alleles give no discernible phenotype. In spite of the fact that beta-tubulin is a highly conserved protein, three-fourths of the mutations do not destroy the ability of the protein to support the growth of yeast at 30 degrees C. The lethal substitutions are primarily located in three regions of the protein and presumably identify domains most critical for beta-tubulin function. Interestingly, most of the conditional-lethal alleles produce specific defects in spindle assembly at their restrictive temperature; cytoplasmic microtubules are relatively unaffected. The exceptions are two mutants that contain abnormally long cytoplasmic microtubules. Mutants with specific spindle defects were not observed in our previous collection of beta-tubulin mutants and should be valuable in dissecting spindle function.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barnes G., Louie K. A., Botstein D. Yeast proteins associated with microtubules in vitro and in vivo. Mol Biol Cell. 1992 Jan;3(1):29–47. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass S. H., Mulkerrin M. G., Wells J. A. A systematic mutational analysis of hormone-binding determinants in the human growth hormone receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 May 15;88(10):4498–4502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.10.4498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker D. M., Guarente L. High-efficiency transformation of yeast by electroporation. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:182–187. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett W. F., Paoni N. F., Keyt B. A., Botstein D., Jones A. J., Presta L., Wurm F. M., Zoller M. J. High resolution analysis of functional determinants on human tissue-type plasminogen activator. J Biol Chem. 1991 Mar 15;266(8):5191–5201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond J. F., Fridovich-Keil J. L., Pillus L., Mulligan R. C., Solomon F. A chicken-yeast chimeric beta-tubulin protein is incorporated into mouse microtubules in vivo. Cell. 1986 Feb 14;44(3):461–468. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90467-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chène P., Mazarguil H., Wright M. Microtubule assembly protects the region 28-38 of the beta-tubulin subunit. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1992;22(1):25–37. doi: 10.1002/cm.970220104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado M. A., Conde J. Benomyl prevents nuclear fusion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;193(1):188–189. doi: 10.1007/BF00327435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs C. S., Zoller M. J. Rational scanning mutagenesis of a protein kinase identifies functional regions involved in catalysis and substrate interactions. J Biol Chem. 1991 May 15;266(14):8923–8931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffaker T. C., Thomas J. H., Botstein D. Diverse effects of beta-tubulin mutations on microtubule formation and function. J Cell Biol. 1988 Jun;106(6):1997–2010. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.6.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs C. W., Adams A. E., Szaniszlo P. J., Pringle J. R. Functions of microtubules in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell cycle. J Cell Biol. 1988 Oct;107(4):1409–1426. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.4.1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassir Y., Simchen G. Monitoring meiosis and sporulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:94–110. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilmartin J. V., Adams A. E. Structural rearrangements of tubulin and actin during the cell cycle of the yeast Saccharomyces. J Cell Biol. 1984 Mar;98(3):922–933. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.3.922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilmartin J. V. Purification of yeast tubulin by self-assembly in vitro. Biochemistry. 1981 Jun 9;20(12):3629–3633. doi: 10.1021/bi00515a050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauhs E., Little M., Kempf T., Hofer-Warbinek R., Ade W., Ponstingl H. Complete amino acid sequence of beta-tubulin from porcine brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981 Jul;78(7):4156–4160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.7.4156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki F., Matsumoto S., Yahara I. Truncation of the carboxy-terminal domain of yeast beta-tubulin causes temperature-sensitive growth and hypersensitivity to antimitotic drugs. J Cell Biol. 1988 Oct;107(4):1427–1435. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.4.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff N. F., Thomas J. H., Grisafi P., Botstein D. Isolation of the beta-tubulin gene from yeast and demonstration of its essential function in vivo. Cell. 1983 May;33(1):211–219. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson J. B., Ris H. Electron-microscopic study of the spindle and chromosome movement in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Sci. 1976 Nov;22(2):219–242. doi: 10.1242/jcs.22.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillus L., Solomon F. Components of microtubular structures in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Apr;83(8):2468–2472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.8.2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RayChaudhuri D., Park J. T. Escherichia coli cell-division gene ftsZ encodes a novel GTP-binding protein. Nature. 1992 Sep 17;359(6392):251–254. doi: 10.1038/359251a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz P. J., Solomon F., Botstein D. Isolation and characterization of conditional-lethal mutations in the TUB1 alpha-tubulin gene of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1988 Nov;120(3):681–695. doi: 10.1093/genetics/120.3.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman F. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:3–21. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94004-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski R. S., Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989 May;122(1):19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stearns T., Botstein D. Unlinked noncomplementation: isolation of new conditional-lethal mutations in each of the tubulin genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1988 Jun;119(2):249–260. doi: 10.1093/genetics/119.2.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J. H., Neff N. F., Botstein D. Isolation and characterization of mutations in the beta-tubulin gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1985 Dec;111(4):715–734. doi: 10.1093/genetics/111.4.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertman K. F., Drubin D. G., Botstein D. Systematic mutational analysis of the yeast ACT1 gene. Genetics. 1992 Oct;132(2):337–350. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.2.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer P., Crossley R., Rothfield L. The essential bacterial cell-division protein FtsZ is a GTPase. Nature. 1992 Sep 17;359(6392):254–256. doi: 10.1038/359254a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]