Abstract

The Liver X receptor (LXR) is an important regulator of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in humans and mice. We have recently shown that activation of LXR regulates cellular fuel utilization in adipocytes. In contrast, the role of LXR in human adipocyte lipolysis, the major function of human white fat cells, is not clear. In the present study, we stimulated in vitro differentiated human and murine adipocytes with the LXR agonist GW3965 and observed an increase in basal lipolysis. Microarray analysis of human adipocyte mRNA following LXR activation revealed an altered gene expression of several lipolysis-regulating proteins, which was also confirmed by quantitative real-time PCR. We show that expression and intracellular localization of perilipin1 (PLIN1) and hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) are affected by GW3965. Although LXR activation does not influence phosphorylation status of HSL, HSL activity is required for the lipolytic effect of GW3965. This effect is abolished by PLIN1 knockdown. In addition, we demonstrate that upon activation, LXR binds to the proximal regions of the PLIN1 and HSL promoters. By selective knock-down of either LXR isoform, we show that LXRα is the major isoform mediating the lipolysis-related effects of LXR. In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that activation of LXRα up-regulates basal human adipocyte lipolysis. This is at least partially mediated through LXR binding to the PLIN1 promoter and down-regulation of PLIN1 expression.

Keywords: Adipocyte, Lipase, Lipid Droplet, Lipolysis, Transcription Regulation, Liver X Receptor, Perilipin 1

Introduction

Obesity and its associated insulin resistance are important risk factors for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Adipose tissue is the main organ for energy storage and release. During adipocyte lipolysis triglycerides (TGs)2 are hydrolyzed into free fatty acids (FFAs) and glycerol (1). It is well established that spontaneous (basal) lipolysis is increased in obesity and that the ensuing increment in circulating FFAs promotes insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes via several mechanisms (2). Hydrolysis of adipocyte TGs is regulated by two lipases: adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) and the tri/diglyceride lipase hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) (1). Activity of HSL is regulated by phosphorylation on several serine residues (3). Lipolytic activity of ATGL requires the presence of the cofactor Comparative Gene Identification 58 (CGI-58). Together, HSL and ATGL are responsible for more than 95% of the TG hydrolysis in murine white adipose tissue (WAT) (4). However, the respective role of ATGL and HSL in the regulation of basal and catecholamine-stimulated lipolysis in human adipocytes is not quite clear (5, 6).

Besides lipases, the lipid droplet-coating proteins are also known important regulators of lipolysis (3). The most essential group is the perilipin (PLIN) family. The phosphoprotein PLIN1 is the most abundant lipid droplet-coating protein in adipocytes (7). In the basal, unphosphorylated state, PLIN1 inhibits TG breakdown by restricting the access of lipases to the lipid droplet, thereby keeping basal lipolysis at a low level (8, 9). Low PLIN1 content is associated with an increased basal but blunted stimulated lipolysis in rodents (10, 11) and humans (12), a state similar to that of obesity (2). In addition to PLIN members, other lipid droplet-associated proteins may also regulate lipolysis. Down-regulation of cell death-inducing DNA fragmentation factor, α subunit-like effector C (CIDEC) by siRNA has been shown to increase lipolysis and decrease lipid droplet-size in 3T3-L1 adipocytes (13, 14). Similarly, down-regulation of another family member, CIDEA, in human adipocytes enhances basal lipolysis (15).

In addition to the acute hormonal lipolytic regulators such as catecholamines, many other factors contribute to the fine-tuning of FFA release from adipocytes (3). The liver X receptor (LXR) is a possible regulator of lipid turnover in fat cells. The role of LXR in adipocyte metabolism has been proposed by studies in LXR deficient mice and in cell cultures, mostly in murine 3T3-L1 adipocytes (16–20). Both LXR isoforms, LXRα and LXRβ are expressed in human white adipocytes. Expression of LXRα is up-regulated during adipocyte differentiation (17, 19), levels of LXRα are higher in obese patients and SNPs in both LXR isoforms are associated with obesity (21). Data obtained in murine systems indirectly imply that activation of LXR up-regulates the release of FFAs and glycerol from adipocytes (22). However, the mechanisms involved in this regulation remain to be established.

In this study we have investigated the role of LXR in human adipocyte lipolysis to further elucidate a possible link between this receptor system and insulin resistance. The role of LXR isoforms on expression, function, and localization of lipolysis-regulating proteins was examined.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Subjects and Cell Culture

Human preadipocytes were differentiated as previously described (23, 24). This cell system has been shown to display a similar lipolysis regulation to human adipocytes in vivo (25). 3T3-L1 cells were cultured and differentiated to adipocytes as previously described (26). Cells were cultured on 24-, 12-, or 6-well plates (Costar, Corning Inc, Corning, NY) and treated with the synthetic LXR agonist GW3965 (Sigma-Aldrich), DMSO, and/or control siRNA or targeting siRNA. For the immunostainings, cells were cultured on 4-well poly-d-lysine-coated chambers (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA).

Lipolysis

Glycerol release into cell culture medium was used as an index of lipolysis and measured by a bioluminescence method as previously described (27, 28). In the experiments with BAY (4-isopropyl-3-methyl-2-W-2H-isoxazol-5–1) (29), Triacsin C (Sigma-Aldrich) or Isoprenaline (Hässle, Mölndal, Sweden) the cells were incubated for 3 h in DMEM/F12 medium supplied with 20 g/liter of BSA.

Microarray Analysis

From high-quality total RNA we prepared and hybridized biotinylated complementary RNA to Gene 1.0 ST Arrays using standardized protocols (Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara, CA). We used the GeneChip Operating Software Version 1.4 for analysis. All microarrays were subjected to an all-probe set scaling to target signal 100. The 22,050 annotated transcripts on the microarrays were included in subsequent analysis. Differences in expression of individual genes on the microarrays between ligand treated and unstimulated preadipoctes were analyzed using significance analysis of microarrays (SAM) with a false discovery rate of 1% (30). Difference in frequency of LXR-regulated lipolysis genes versus other regulated genes were compared by the Hypergeometric z-test.

Quantitative Real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted, and cDNA was synthesized as previously described (20). qRT-PCR was performed using an iCycler IQTM (Bio-Rad) with Taqman® probes (Assays-on-Demand, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) for all genes except HSL and PLIN1, for which Sybrgreen detection method was used. PCR conditions and primers have been described previously (25, 31). The mRNA levels of the different genes were determined by the 2−ΔΔCT comparative method (32). The 18 S and low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 10 were used as reference genes with similar results.

Western Blot

Protein expression levels were assessed as previously described (20, 27). The following antibodies were used: CIDEC (18–001-30077, GenWay Inc, San Diego, CA), PLIN1 (GP29, Progen, Heidelberg, Germany), CGI-58 (H00051099-M01, Abnova, Tapei City, Taiwan), phosphorylated-HSL antibodies (pSer660 4126, pSer563 4139, pSer565 4137 Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). Two different total HSL antibodies were used with similar results: 4107 from Cell Signaling and a kind gift from Prof. Cecilia Holm (Lund University, Lund, Sweden). β-Actin (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as a reference for all Western blots. Appropriate secondary antibodies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Immunostaining

To examine the localization of PLIN1 and HSL in the same cell we performed a sequential double immunocytochemical staining, as previously described (6). The antibodies used were AlexaFluor-488 and -568 (A11039 and A10042, Invitrogen Molecular Probes), PLIN1 (ab3526–100, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), anti-HSL (a kind gift from Prof. Cecilia Holm), and Hoechst (33258, Invitrogen Molecular Probes).

Microscopy and Image Analysis

Immuno-fluorescence images were obtained with an Axio Observer.Z1 inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH, Göttingen, Germany) using a 63×/1.40 Oil Plan-Apochromat objective, Axiocam MRm camera and the AxioVision software as previously described (6). Adipocyte cultures from three different patients were used. At least three z-stacks after deconvolution from three different lipid droplets in three different cells were analyzed per patient.

RNAi

In vitro-differentiated preadipocytes were treated with targeting siRNA or non-targeting control siRNA as previously described (20), medium was collected, and cells were lysed for RNA or protein. Specific siRNA against LXRα (NR1H3), LXRβ (NR1H2) or PLIN1 was obtained from Dharmacon (ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool Dharmacon Inc., Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). No important off-target effects of siRNA were detected in our cell system (20).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

In vitro differentiated adipocytes were treated with GW3965 for 6 h, and ChIP assay was performed as previously described (33). The LXR antibody was a kind gift from Knut Steffensen (Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden), the RXR (sc-774), Pol II (H-224, sc-9001), and IgG (sc-2027) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Quantification of the precipitated DNA regions was performed by qPCR, for primers see supplemental data.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test or Mann-Whitney test. All data are presented as means ± S.D. or S.E. N relates to number of donors. All experiments were performed in duplicates or triplicates.

RESULTS

LXR Up-regulates Basal Lipolysis in White Human Adipocytes

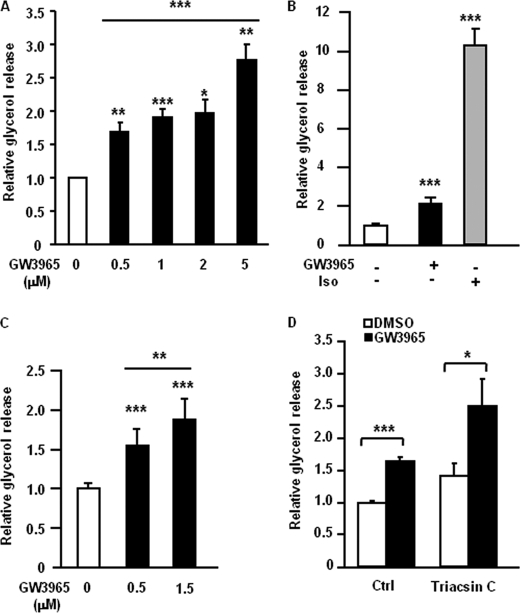

In vitro-differentiated human adipocytes were stimulated for 48 h with different concentrations of the LXR agonist GW3965. LXR activation up-regulated basal glycerol release into the cell culture medium in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1A, p < 0.05–0.001). However, cell-toxic effects were observed at the highest concentration of GW3965 (data not shown). We therefore chose to use 1 μm GW3965 in all subsequent experiments. Similar results were obtained using another LXR agonist, T0901317 (data not shown). In addition, pretreatment of in vitro differentiated human adipocytes with GW3965 for 48 h caused increased glycerol release into lipolytic medium during 3-h incubation. However, this effect was lower than the acute stimulation by the known lipolytic agent isoprenalin (Fig. 1B). The pro-lipolytic effect of GW3965 was not restricted to human adipocytes, since activation of LXR in differentiated murine 3T3-L1 adipocytes resulted in higher glycerol release as compared with control (Fig. 1C). Next the influence of fatty acid re-esterification on LXR-induced lipolysis was evaluated. In vitro-differentiated adipocytes were treated with GW3965 or vehicle for 48 h and subsequently incubated with or without the acyl-CoA synthase inhibitor Triacsin C. Although Triacsin C slightly, but not significantly, increased basal glycerol release the relative effect of the LXR agonist on lipolysis was similar with or without the re-esterification inhibitor (Fig. 1D). Shorter incubations (12–24 h) with GW3965 did not significantly affect lipolysis in human adipocytes (data not shown). We therefore hypothesized that LXR mediates its effects on lipolysis via transcriptional regulation.

FIGURE 1.

LXR up-regulates glycerol release in human and murine 3T3-L1 adipocytes independent of re-esterification. A, in vitro-differentiated human adipocytes were treated with different concentrations of GW3965 (black bars) or vehicle (white bar) for 48 h, after which medium was removed, and glycerol release was measured. Values were corrected for protein concentration in each experimental group. Means ± S.D. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; n = 3–7. B, adipocyte cultures were pretreated with 1 μm of GW3965 (black bar) or vehicle (DMSO, white bar) for 48 h and incubated in lipolytic medium for 3 h. Glycerol release was measured, and values were corrected for protein concentration in each experimental group. The known lipolytic agent isoprenaline (Iso) was used as a positive control for acute lipolysis induction. Means ± S.D., n = 3. C, differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes were treated with different concentrations of GW3965 (black bars) or vehicle (white bar) for 48 h, after which medium was removed, and glycerol release was measured. Values were corrected for protein concentration in each experimental group. Means ± S.D. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001, n = 7. D, adipocyte cultures were pretreated with 1 μm of GW3965 (black bars) or vehicle (DMSO, white bars) for 48 h, and incubated in lipolytic medium for 3 h with or without Triacsin C. Glycerol release was measured, and values were corrected for protein concentration in each experimental group. Means ± S.D. *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001; n = 2.

LXR Activation Has a Profound Effect on Lipolytic Signaling Pathways

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of LXR on lipolysis we performed microarray analysis on RNA from in vitro-differentiated adipocytes treated with GW3965 or vehicle for 24 h. Cells from five different subjects were used. Ten different chips were analyzed for the two conditions. 293 transcripts were up-regulated and 1194 down-regulated according to SAM. The cholesterol transporters ABCG1 and ABCA1, well-established LXR-responsive genes (34), were strongly up-regulated (Table 1), confirming that we obtained a proper LXR activation. SAM analysis showed that several lipolytic genes (3) were regulated by LXR activation. Table 1 lists the genes that have been implicated in regulation of lipolysis (even genes with low absolute call) or genes that could be of potential importance and had an absolute call above 150 in the microarray data set. LXR activation affected the mRNA expression of several cell surface receptors, G-proteins, and regulatory proteins. Further downstream, GW3965 strongly down-regulated the gene expression of HSL (LIPE) and the lipid droplet-associated proteins PLIN1, CGI-58 (ABHD5), and CIDEC. The mRNA levels of ATGL, the adipocyte-specific gene CIDEA, the lipid droplet protein adipophilin (PLIN2) or the adipocyte differentiation marker peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARG) were not regulated by LXR, according to SAM (Table 1). Taken together, SAM analysis showed that LXR affected the expression of 6.1% of all genes represented on the microarray chip and 25% of the genes involved in lipolysis regulation (p = 3 × 10−6). These findings suggested that LXR regulates human adipocyte lipolysis at the gene expression level.

TABLE 1.

Effect of the LXR agonist GW3965 on lipolysis-related gene expression

Microarray-based level of expression is shown as absolute call and fold-change of expression induced by the LXR agonist is indicated. Significantly (SAM) regulated genes are pointed out in the last column

| Gene groups | Gene symbol | Absolute call in untreated cells | Fold-change | Regulated by LXR activation (SAM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receptors | ||||

| β-adrenergic receptors | ADRB1 | 172 | 1.10 | |

| ADRB2 | 77 | 1.15 | ||

| ADRB3 | 51 | 1.03 | ||

| α-adrenergic receptors | ADRA2A | 228 | 0.72 | Yes |

| ADRA2B | 196 | 0.90 | ||

| ADRA2C | 263 | 1.01 | ||

| ADORA1 | 88 | 0.95 | ||

| Natriuretic peptide receptors | NPR-A | 278 | 0.79 | |

| NPR-C | 43 | 0.96 | ||

| G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) | GPR81 | 112 | 0.59 | |

| GPR109A | 340 | 0.3 | Yes | |

| GPR109B | 206 | 0.27 | Yes | |

| NPFFR2 (GPR74) | 46 | 1.02 | ||

| Other receptors | EP-3R | 184 | 0.47 | Yes |

| NPY-R1 | 50 | 1.17 | ||

| INSR | 183 | 1.13 | ||

| IGF-1R | 81 | 1.01 | ||

| TNFAR | 50 | 1.11 | ||

| EDNRA | 40 | 1.72 | Yes | |

| IL-6R | 103 | 1.21 | ||

| G-proteins | ||||

| Gα inhibitory | GNAI1 | 171 | 0.72 | Yes |

| GNAI2 | 851 | 1.03 | ||

| GNAI3 | 432 | 0.95 | ||

| Gα stimulatory | GNAT1 | 149 | 1.01 | |

| GNAT2 | 132 | 0.89 | ||

| Gβ | GNB1 | 1754 | 0.96 | |

| GNB2 | 262 | 1.05 | ||

| Gγ | GNG2 | 173 | 0.42 | Yes |

| GNG11 | 90 | 1.59 | Yes | |

| GNG5 | 402 | 1.36 | ||

| GNG12 | 960 | 1.06 | ||

| GNG10 | 463 | 0.84 | ||

| GNG7 | 164 | 0.97 | ||

| Adenylyl cyclases | ADCY1 | 285 | 1.01 | |

| ADCY3 | 249 | 1.63 | Yes | |

| ADCY6 | 407 | 0.89 | ||

| Phosphodiesterase | PDE3B | 644 | 0.63 | |

| PKA | PRKAR2B | 1293 | 0.47 | Yes |

| PRKAR2A | 571 | 0.83 | ||

| PRKAA2 | 552 | 0.91 | ||

| PRKAR1A | 1827 | 0.97 | ||

| PRKAA1 | 357 | 0.92 | ||

| PKG | PRKG1 | 99 | 1.12 | |

| PRKG2 | 61 | 0.61 | Yes | |

| Lipases | LIPE (HSL) | 1604 | 0.50 | Yes |

| ATGL | 1657 | 0.76 | ||

| MGL | 673 | 0.95 | ||

| Lipid-binding and lipid droplet-associated proteins | PLIN1 (PLIN) | 1805 | 0.40 | Yes |

| PLIN2 (ADRP) | 3432 | 1.29 | ||

| PLIN3 (TIP47) | 403 | 1.19 | ||

| CIDEC | 1416 | 0.40 | Yes | |

| CIDEA | 47 | 0.85 | ||

| CAV1 | 1317 | 0.54 | Yes | |

| FABP4 (aP2) | 5877 | 0.83 | ||

| ABHD5 (CGI-58) | 511 | 0.56 | Yes | |

| AQP7 | 1173 | 0.82 | ||

| Miscellaneous | PPARG | 1001 | 1.01 | |

| ABCG1 | 70 | 6.6 | Yes | |

| ABCA1 | 845 | 2.5 | Yes | |

| SREBP1 | 750 | 1.57 | Yes |

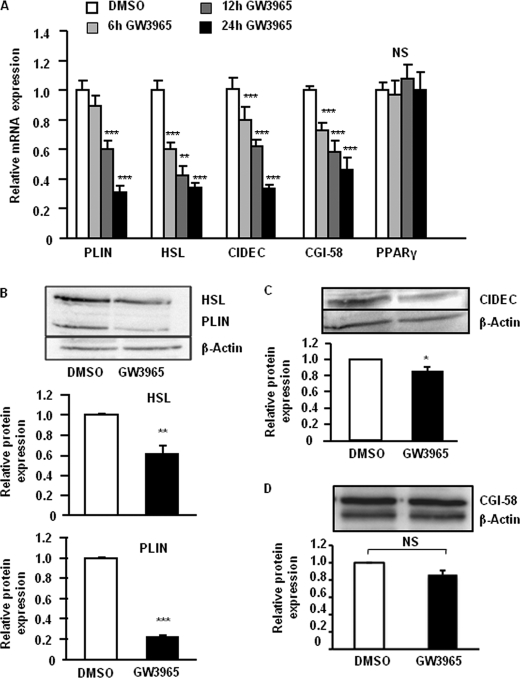

Activation of LXR Down-regulates Expression of Several Lipolytic Proteins

To confirm the results from the microarray analysis and try to elucidate if the effect of LXR on lipolytic gene expression is direct, we performed qRT-PCR measurements on samples from adipocytes treated with GW3965 or vehicle for 6, 12, or 24 h. We chose to investigate PLIN1, HSL, CIDEC, and CGI-58 because their role in regulation of basal adipocyte lipolysis is well documented (3). In accordance with the microarray data, the mRNA levels of HSL, CIDEC, and CGI-58 were significantly down-regulated by GW3965 already 6 h after stimulation (Fig. 2A, p < 0.05–0.001), suggesting a direct effect of LXR on transcriptional regulation. PLIN1 mRNA levels were slightly down-regulated after 6 h and reached significance after 12 h of treatment. The levels of ABCG1 mRNA were strongly increased (data not shown) at 6 h of stimulation while expression of PPARγ was not affected (Fig. 2A). Another LXR agonist (T091317) caused similar effect on PLIN1, HSL, and CGI-58 expression (data not shown). Next we examined if the effects at mRNA level caused by LXR activation corresponded to changes in protein expression. Differentiated adipocytes were treated with GW3965 for 48 h and protein expression was analyzed by Western blot. Activation of LXR caused a significant decrease of HSL, PLIN1, and CIDEC expression, corroborating the findings at the mRNA level (Fig. 2, B and C). Expression of PLIN1 was most pronouncedly suppressed by 78% (p < 0.001). In contrast to the finding at mRNA level, the protein expression of CGI-58 was not affected by the LXR agonist (Fig. 2D). LXR activation did not affect the expression of ATGL, and the effect on CIDEC protein expression was only marginal (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Therefore, we chose to focus further on the involvement of PLIN1 and HSL in the LXR-mediated up-regulation of basal lipolysis.

FIGURE 2.

LXR agonist affects expression of several lipolytic genes. A, in vitro-differentiated human adipocytes were treated with vehicle (white bars) or GW3965 for 6 h (light gray bars), 12 h (dark gray bars), or 24 h (black bars). Levels of mRNA were assessed using qRT-PCR. Means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001, n = 4–7. B–D, in vitro-differentiated human adipocytes were treated with GW3965 (black bars) or vehicle (white bars) for 48 h, and protein levels were assessed by Western blot. β-Actin was used as control for equal loading. Means ± S.D. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001, n = 3–4. Representative picture of Western blot and quantification of expression levels for HSL, PLIN1 (B), CIDEC (C), and CGI-58 (D) are shown.

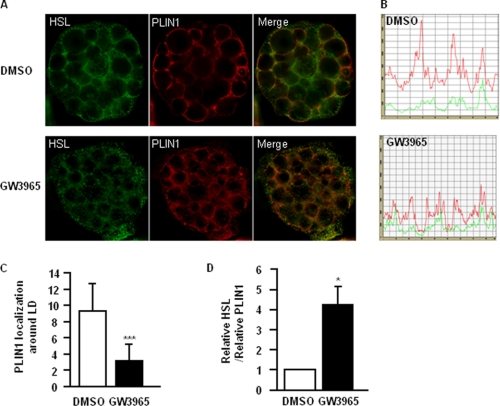

LXR Activation Affects the Localization of PLIN1 and HSL on the Lipid Droplet

It is well established that adipocyte lipolysis is not only regulated by the expression of lipolytic proteins, but also by their intracellular localization (9). Therefore, we assessed the intracellular localization of HSL and PLIN1 in GW3965-treated cells by immunocytochemistry. In control cells, PLIN1 was distributed evenly around the lipid droplets while staining representing HSL around the lipid droplets was low. After stimulation with GW3965, PLIN1 staining around the lipid droplets was decreased and appeared more fragmented (Fig. 3, A and B). In addition, HSL staining showed a dotted pattern, which could represent protein aggregation. By quantifying the total number of positive pixels along the perimeter of the lipid droplets, we found that the presence of PLIN1 around the droplet was significantly lower in GW3965-treated cells (Fig. 3C, p < 0.001). Furthermore, the ratio of HSL/PLIN1 was significantly increased in cells stimulated by LXR agonist compared with control (Fig. 3D, p < 0.05). This indicated that LXR activation induced alterations at the lipid droplet surface and suggested that HSL might be activated.

FIGURE 3.

Activation of LXR induces re-distribution of HSL and PLIN1 in human adipocytes. A, in vitro-differentiated human adipocytes were treated with 1 μm GW3965 for 48 h and sequentially stained for HSL and PLIN1. A, representative Z-sections after de-convolution are shown. B, representative profiles of PLIN1 (red) and HSL (green) staining, displaying signals on the rim of lipid droplet. C and D, line corresponding the perimeter of the lipid droplet was drawn and intensity of fluorescent pixels corresponding to PLIN1 or HSL (total positive pixels in the red and green channel, respectively) around the lipid droplet were calculated. Amount of PLIN1 in vehicle (white bars) and LXR agonist-treated (black bars) cells was calculated (C). The relative amount of PLIN1 to HSL was calculated and compared in control and GW3965-treated cells (D). Means ± S.D. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01, n = 3.

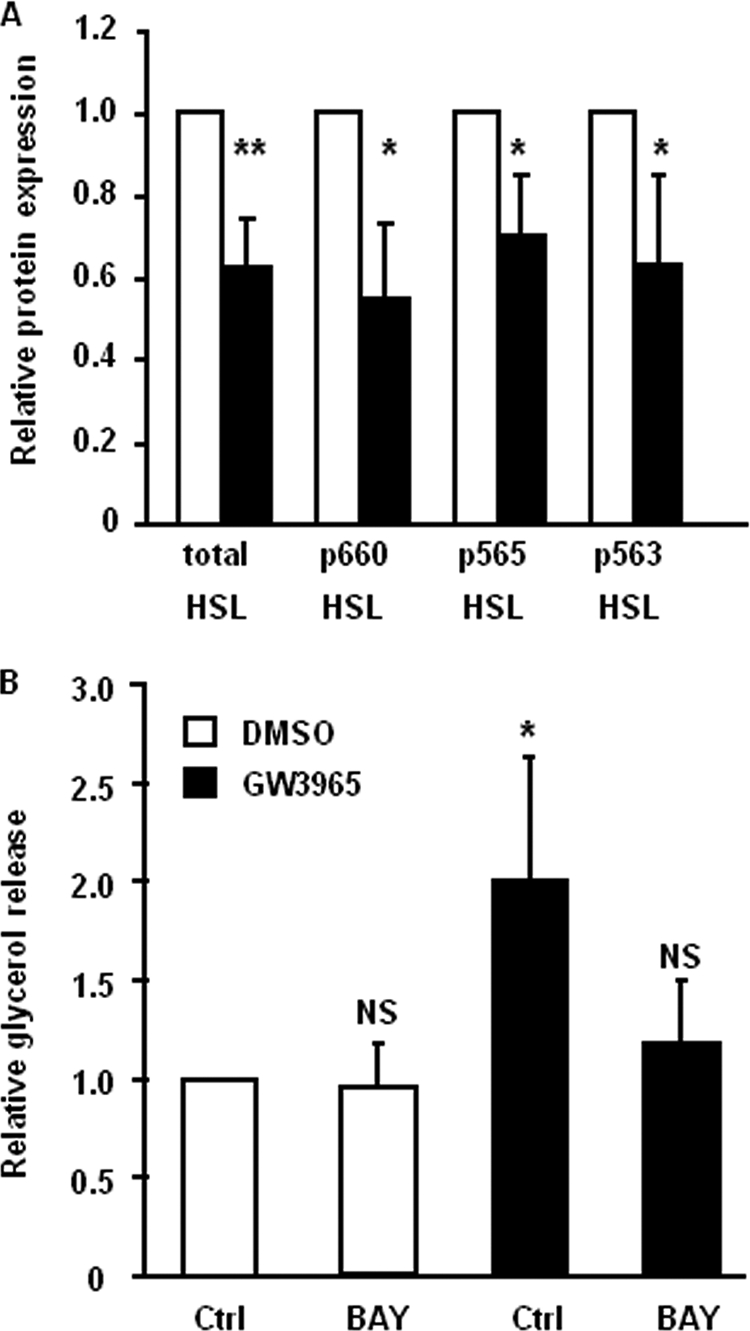

HSL Phosphorylation Status Is Not Affected by LXR, but HSL Activity Is Required for LXR Agonist-induced Lipolysis

To investigate the effects on the activation of HSL, we treated differentiated adipocytes with GW3965 for 48 h and performed Western blot with antibodies directed against HSL phosphorylation sites known to affect lipase activity (3, 35). We observed that the phosphorylated forms of HSL were down-regulated by GW3965 to the same extent as total HSL protein (Fig. 4A) and amount of phosphorylated HSL per total HSL was not changed (data not shown) by GW3965 treatment. These findings suggested that GW3965 affected HSL protein expression but not phosphorylation. To investigate the functional consequence of HSL down-regulation, glycerol release was measured in GW3965-pretreated adipocytes in the presence or absence of the specific HSL inhibitor BAY. Cells treated with GW3965 showed up-regulated lipolysis similar to the effect demonstrated in Fig. 1A. In cells treated with the HSL inhibitor, the effect of the LXR agonist on glycerol release was abolished, and the level of released glycerol was similar to that of control cells (Fig. 4A, p < 0.05). This implied that the LXR effect on basal lipolysis was dependent on HSL activity.

FIGURE 4.

HSL phosphorylation is not affected by GW3965, but HSL activity is required for LXR-mediated lipolysis. A, in vitro-differentiated human adipocytes were treated with 1 μm GW3965 (black bars) or vehicle (white bars) for 48 h and protein levels of phosphorylated and total HSL were assessed by Western blot. Quantification after adjustment for β-actin is shown, ± S.D. n = 3–4. B, in vitro-differentiated human adipocytes were preincubated with 1 μm GW3965 (black bars) or vehicle (white bars) for 48 h and then incubated with lipolytic medium with or without the HSL inhibitor BAY for 3 h. Glycerol release was measured and corrected for protein amount in each experimental group. Means ± S.D. *, p < 0.05, n = 3.

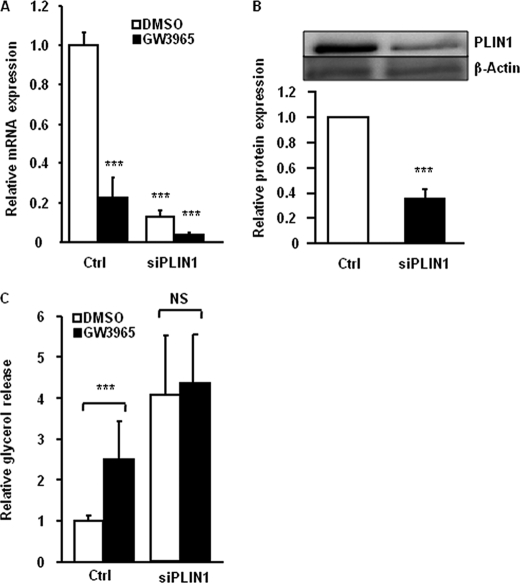

Knockdown of PLIN1 Abolishes the Effect of LXR on Lipolysis

Because our data indicated that LXR did not affect HSL phosphorylation, we hypothesized that down-regulation of PLIN1 might be the major event in the LXR-mediated lipolysis up-regulation. Therefore, we performed siRNA-mediated knockdown of PLIN1 in in vitro-differentiated human adipocytes. Analysis of mRNA and protein expression in cells treated with siRNA showed an efficient knockdown of PLIN1 (80–95 and 60% suppression at mRNA and protein levels, respectively) (Fig. 5, A and B, p < 0.001). Knockdown of PLIN1 increased basal lipolysis (Fig. 5C, p < 0.001) and the effect of GW3965 was abolished in cells treated with siPLIN1 (Fig. 5C, p < 0.001). This supported our hypothesis on the role of PLIN1 down-regulation in LXR-induced lipolysis.

FIGURE 5.

Knockdown of PLIN1 abolishes the effect of LXR on activation of lipolysis. In vitro-differentiated adipocytes were treated with nonspecific siRNA (Ctrl) or siRNA against PLIN1 (siPLIN1) and stimulated with GW3965 (black bars) or vehicle (white bars) for 48 h. A, expression of PLIN1 mRNA was investigated by qRT-PCR, means ± S.D., n = 4, p < 0.001. B, expression of PLIN1 protein was investigated by Western blot and adjusted for β-actin (n = 4, p < 0.001). C, glycerol release was quantified in cell cultures treated with siRNA and stimulated with GW3965 or vehicle. Values were corrected for protein concentration in each experimental group. Means ± S.D., n = 4. ***, p < 0.001.

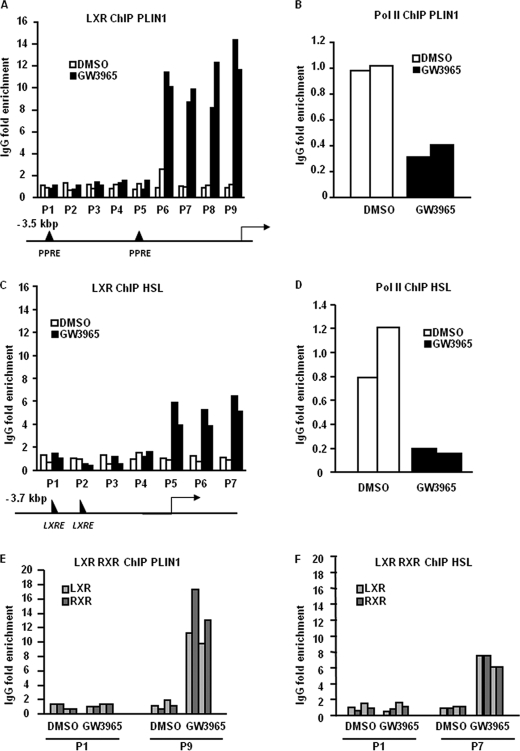

LXR and Retinoid X Receptor (RXR) Are Recruited to the PLIN1 and HSL Promoters in Vivo

We further examined if LXR binds to the PLIN1 promoter by performing ChIP. We could not identify any LXREs in the human PLIN1 promoter (3.5-kb upstream transcription start site) using the MatInspector software. Therefore, we designed several primers pairs overlapping known PPARγ response elements (PPREs) (36) (P1 and P5) and predicted RXR sites (P2-P4, P6, P9). In addition, primers amplifying the proximal regions of the PLIN1 promoter were used (P7, P8) (Fig. 6A). Enrichment of the promoter fragments in ChIP using anti-LXR antibody versus unspecific IgG was examined by qPCR. Our results indicated that activated LXR bound to the proximal regions of PLIN1 promoter, but not PPARγ sites (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, ChIP with anti-polymerase II (Pol II) antibodies showed reduced binding of Pol II to the PLIN1 promoter in GW3965-treated adipocytes (Fig. 6B). This finding was in line with diminished transcription of the PLIN1 gene determined by qRT-PCR. In the HSL promoter, two weak LXREs were predicted 3.6- and 2.6-kb upstream transcription start site. However, we did not observe LXR binding to these sites (Fig. 6C, primers P1 and P2). Several RXR sites were predicted by MatInspector software in the proximal regions of HSL promoter and intron 1. We designed primers (P3-P7) that would amplify these regions. ChIP analysis demonstrated that upon activation LXR was recruited to intron 1 of the HSL gene. At the same time, recruitment of Pol II to the HSL promoter was reduced (Fig. 6D). LXR binding to the promoter of the control gene ABCG1 was also enriched (data not shown).

FIGURE 6.

LXR and RXR bind to the PLIN1 and HSL promoters. In vitro-differentiated human adipocytes were treated with GW3965 or vehicle for 6 h and ChIP assays were performed. A, LXR binds to the proximal part of the PLIN1 promoter. Enrichment of PLIN1 promoter fragments in ChIP using anti-LXR antibodies compared with unspecific IgG is shown. White bars correspond to vehicle-treated cells, and black bars represent GW3965-treated cells from two independent experiments, using cell cultures from different subjects. P1–P9 corresponds to different primer pairs (see supplemental data). B, enrichment of Pol II binding to the PLIN1 promoter was assessed using primer pair P9. C, LXR binds to the intron 1 of the HSL gene. Enrichment of HSL promoter fragments in ChIP using anti-LXR antibodies compared with unspecific IgG is shown. White bars correspond to vehicle-treated cells and black bars represent GW3965-treated cells from two independent experiments, using cell cultures from different subjects. P1–P7 corresponds to different primer pairs (see supplemental data). D, enrichment of Pol II binding to the HSL promoter was assessed using primer pair P7. E and F, RXR and LXR are recruited in a similar fashion to selected regions of the PLIN1 and HSL genes (P1 and P9 for PLIN1; P1 and P7 for HSL). Light gray bars represent ChIP using LXR antibodies, and dark gray bars represent ChIP using RXR antibodies.

LXR is known to bind DNA as a heterodimer with another nuclear receptor, RXR. Therefore we performed ChIP analysis with an anti-RXR antibody. Our results indicated that stimulation by LXR agonist also induced RXR recruitment to the LXR binding regions of PLIN1 and HSL promoters in human adipocytes (Fig. 6, E and F).

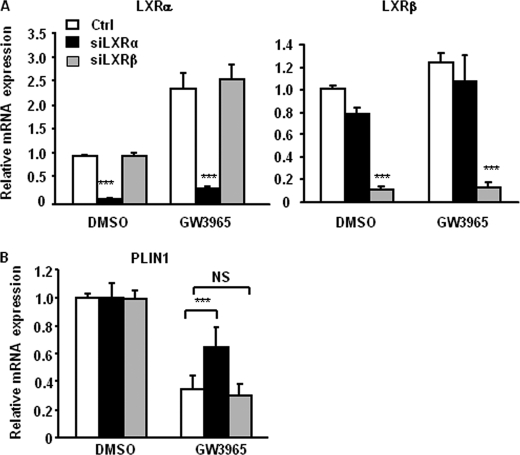

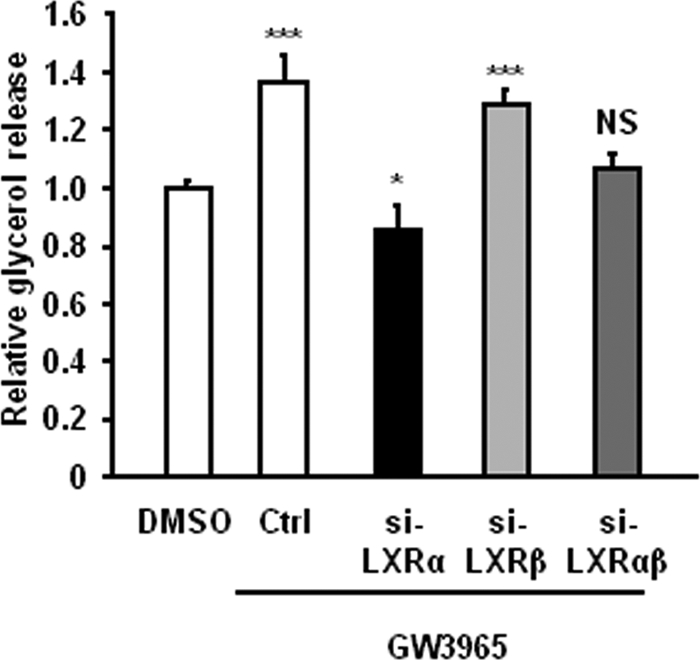

LXRα Is Required for Up-regulation of Basal Lipolysis by LXR Agonist

To elucidate which LXR isoform is responsible for the regulation of basal lipolysis, we performed isoform-specific knockdowns using siRNA in human adipocytes. The RNAi was efficient and resulted in a specific knockdown of mRNA of either LXR isoform by up to 95% (Fig. 7A). Expression of LXRα was induced by GW3965, confirming the positive auto-regulatory mechanism reported earlier (34). We examined the expression of PLIN1 and levels of basal lipolysis in adipocytes treated with siRNA followed by stimulation with the LXR agonist and observed a significantly lower effect of GW3965 on PLIN1 expression in the cells treated with LXRα-specific siRNA (siLXRα), compared with cells transfected with siLXRβ or control siRNA (Fig. 7B, p < 0.001). Furthermore, the up-regulation of glycerol release by GW3965 was abolished in cells transfected with siLXRα but not with siLXRβ (Fig. 8). These results suggest that LXRα is the main isoform mediating the effects of GW3965 on lipolysis in human primary adipocytes. To control for specificity of the agonist, double knockdowns of LXRα and LXRβ were also performed. GW3965 had no effect on basal lipolysis in adipocytes where both LXR isoforms were down-regulated. Cells treated with siLXRα and stimulated with LXR agonist showed lower glycerol release, compared with siLXRα/β-treated cells (Fig. 8, p < 0.05). This could be explained by a more efficient down-regulation of LXRα in the single knockdown condition.

FIGURE 7.

Presence of LXRα is important for the effects of GW3965 on PLIN1 expression. In vitro-differentiated adipocytes were treated with nonspecific (Ctrl, white bars), LXRα (siLXRα, black bars), or LXRβ (siLXRβ, gray bars) siRNA and stimulated with GW3965 or vehicle (DMSO) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A, mRNA expression of LXRα (left panel) and LXRβ (right panel) was investigated by qRT-PCR (n = 4, means ± S.D.). B, mRNA expression of PLIN1 was examined by qRT-PCR (n = 4, ***, p < 0.001; means ± S.D.).

FIGURE 8.

Presence of LXRα is required for GW3965-mediated up-regulation of lipolysis. Glycerol release was quantified in in vitro-differentiated adipocyte cell cultures treated with nonspecific (Ctrl), LXRα (siLXRα), LXRβ (siLXRβ), or both LXRα and β (siLXRαβ) and stimulated with GW3965. Graph shows relative glycerol release in GW3965-stimulated cells compared with vehicle (DMSO)-stimulated cells (means ± S.D., n = 4; *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Increased basal adipocyte lipolysis is associated with a number of insulin resistant conditions. Several paracrine, endocrine, and neural factors contribute to the fine-tuning of fatty acid release from the adipose tissue. Our present study demonstrates for the first time that agonist activation of LXR increases basal lipolysis and affects the expression and function of several lipolysis-regulating proteins in human adipocytes. We also show that PLIN1 is an LXR target gene, and we conclude that LXR is a regulator of human adipocyte lipolysis.

The microarray data imply that LXR regulates human adipocyte lipolysis at several different levels, with 25% of the lipolysis-regulating genes affected by LXR activation. This report focuses on the role of LXR in regulating spontaneous adipocyte lipolysis, while LXRs role in regulation of stimulated lipolysis is presently under investigation. Activation of LXR causes a strong down-regulation of PLIN1 both at mRNA and protein level. In addition, immunocytochemistry experiments indicate that the staining intensity of PLIN1 around the lipid droplet is reduced upon LXR activation, which most likely cause disturbance of lipid droplet morphology. Knockdown of PLIN1 using RNAi abolishes the effect of LXR agonist on basal lipolysis. In addition, GW3965 also slightly down-regulates CIDEC, another important lipid droplet protein. Low levels or absence of PLIN1 and CIDEC have been implicated in enhanced spontaneous lipolysis both in mice and humans (10–12). Consequently, down-regulation of lipid droplet-coating proteins, and PLIN1 in particular, could be a major mechanism for the LXR-induced spontaneous lipolysis.

Both mRNA and protein levels of the lipase HSL are decreased by GW3965 treatment, while the phosphorylation status, at least of the serine residues examined here, is not affected. At present, we cannot exclude the possibility that HSL might be phosphorylated on other sites, which could affect the enzymatic activity. The impact of HSL protein amount on the rate of basal lipolysis is not clear. Previous studies show that down-regulation of HSL might not affect (6, 37) or can attenuate (5) the rate of basal lipolysis. In the present study it is apparent though, that the effect of PLIN1 down-regulation (causing an increased basal lipolysis) overrides down-regulation of HSL (causing a decreased lipolysis). This is similar to the lipolytic effect mediated by tumor necrosis factor α (38, 39). The data obtained using the HSL inhibitor indicate that HSL activity is required for the up-regulation of lipolysis caused by LXR activation. Another adipocyte lipase, ATGL, was not regulated by LXR according to the SAM analysis, and we could not confirm regulation of ATGL cofactor CGI-58 at the protein expression level. However, PLIN1 down-regulation may allow release of CGI-58 (40) from the lipid droplet surface, and thereby activate ATGL. Although our present data speak against a direct role, we cannot fully exclude involvement of ATGL and/or CGI-58 in lipolysis regulation by LXR.

LXR binds to LXR response elements in DNA (LXREs) as a heterodimer with the RXR. Although LXREs have mostly been implicated in positive gene regulation, LXR can also suppress gene expression via interaction with other transcription factors and cofactors (reviewed in Ref. 41), and a negative LXRE is reported (42). The ChIP-analysis demonstrates LXR and RXR binding to the proximal parts of the PLIN1 and HSL promoters in human adipocytes, which correlates with a reduced binding of Pol II to these genes, confirming diminished transcription at the PLIN1 and HSL gene loci. At present we do not know if LXR regulates expression of PLIN1 and HSL via direct binding to DNA or via interaction with other transcription factor and cofactor complexes on the promoters. However, our mRNA expression kinetic data and ChIP experiments suggest that LXR regulates lipolytic genes via its direct recruitment to the gene promoters. Agonist-induced recruitment of LXR/RXR-dimers to gene promoters usually positively regulates transcription (41). Data presented here indicate that upon activation, LXR/RXR can be recruited to the promoter regions and can instead negatively regulate transcription.

Expression of PPARγ or known PPARγ target genes such as aP2, ACS, or S3–12 is not affected by LXR stimulation in our experimental setup, although LXR has been shown to up-regulate PPARγ and potentiate its adipogenic effect by previous studies (43). This discrepancy might be explained by the difference in the degree of differentiation of the adipocytes at time of stimulation. It is conceivable that LXR-PPARγ cross-talk might be of less importance in fully or near-fully differentiated adipocytes.

The overall role of LXR in the regulation of lipid turnover in white adipocytes is puzzling. Adipocytes harbor large amounts of nonesterified cholesterol, a potential source of natural ligands for LXR (44). However, the physiological conditions and endogenous signals that activate LXR in fat cells are unknown. Several studies implicate a role of LXR in lipid accumulation in adipocytes (17, 19), but we (data not shown) and others (45) have not observed any effects of LXR activation on the expression of genes involved in de novo lipogenesis. Quite contrary, LXR stimulates FA oxidation in human adipocytes (20). Thus, in in vitro-differentiated human adipocytes, LXR up-regulates both lipolysis and FA oxidation. These findings are in line with previous reports in murine models, demonstrating that ectopic expression of LXRα induces FFA and glycerol release from rodent adipocytes (22). Administration of LXR agonist to mice causes higher levels of glycerol in the serum (22) and a decreased size of white adipocytes (46). Taken together, these findings suggest that LXR activity increases both lipid breakdown and utilization in white adipocytes.

Several previous studies point to that LXRα might be the main isoform regulating adipocyte metabolism (22, 34, 47). In the present study, selective knockdowns of the two LXR isoforms demonstrated that LXRα is the major isoform mediating the lipolytic effect of LXR in human fat cells. This is, to our knowledge, the first demonstration of selective roles of LXR subtypes in human adipocytes. Previous work has shown that the relative expression levels of LXRα are higher in obese women in comparison to lean subjects (21). This is in line with observations that obese subjects display enhanced basal lipolysis and decreased levels of PLIN1 (12). These data indicate that LXRα might be an important regulator of human adipocyte lipolysis in vivo. On the other hand, LXRβ-deficient mice display a clear difference in adipocyte phenotype compared with wild type mice (16). It is therefore possible that LXRα and LXRβ regulate different metabolic pathways. Further investigation is needed to better establish the function of both LXR isoforms in human fat cells.

The ability of LXR activators to promote reverse cholesterol transport and limit inflammation in macrophages make them attractive drug target. However, administration of the non-isoform-specific LXR agonists to mice induces expression of lipogenic genes in the liver and raises plasma triglyceride levels (48). Although there are no isoform-specific LXR agonists available at present, it is possible that these agents could play a role in future clinical evaluation. Our study suggests that LXRα could have a deleterious effect by increasing lipolysis, a process strongly associated to the development of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes.

In conclusion, we demonstrate a novel and isoform-specific role for the nuclear receptor LXR in human adipocytes, namely regulation of lipolysis. Activation of LXRα influences several important lipolytic proteins and up-regulates basal lipolysis, implicating a role of LXRα in the development of insulin resistance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Eva Sjölin and Kerstin Wåhlén for excellent technical assistance.

This study was supported in part by the Swedish Research Council, NovoNordisk, Swedish Diabetes Association, Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation, EndoMet, Karolinska Institutet, Åke Wiberg Foundation, Magn Bergvalls Foundation, the European Union [HEPADIP (LSHM-CT-2005-018734), ADAPT (HEALTH-F2-2008-201100], NordForsk (SYSDIET-070014), COST action BM 0602, and NWO Rubicon (825.07.025).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental data.

- TG

- triglyceride

- ATGL

- adipose triglyceride lipase

- Bay

- 4-isopropyl-3-methyl-2-[1-(3(S)-methyl-piperidin-1-yl)-methanoyl]- 2H-isoxazol-5-one

- CIDEC and CIDEA

- cell death-inducing DNA fragmentation factor, α subunit-like effector C and A, respectively

- FFA

- free fatty acid

- HSL

- hormone-sensitive lipase

- LXR

- liver X receptor

- PLIN1

- perilipin 1

- SAM

- significance analysis of microarrays.

REFERENCES

- 1. Arner P., Langin D. (2007) Curr. Opin. Lipidology 18, 246–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arner P. (2005) Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 19, 471–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lafontan M., Langin D. (2009) Prog. Lipid Res. 48, 275–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schweiger M., Schreiber R., Haemmerle G., Lass A., Fledelius C., Jacobsen P., Tornqvist H., Zechner R., Zimmermann R. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 40236–40241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ryden M., Jocken J., van Harmelen V., Dicker A., Hoffstedt J., Wiren M., Blomqvist L., Mairal A., Langin D., Blaak E. E., Arner P. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol Metab. 292, 1847–1855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bezaire V., Mairal A., Ribet C., Lefort C., Girousse A., Jocken J., Laurencikiene J., Anesia R., Rodriguez A. M., Ryden M., Stenson B. M., Dani C., Ailhaud G., Arner P., Langin D. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 18282–18291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marcinkiewicz A., Gauthier D., Garcia A., Brasaemle D. L. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 11901–11909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brasaemle D. L. (2007) J. Lipid Res. 48, 2547–2559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moore H. P., Silver R. B., Mottillo E. P., Bernlohr D. A., Granneman J. G. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 43109–43120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tansey J. T., Sztalryd C., Gruia-Gray J., Roush D. L., Zee J. V., Gavrilova O., Reitman M. L., Deng C. X., Li C., Kimmel A. R., Londos C. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 6494–6499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Martinez-Botas J., Anderson J. B., Tessier D., Lapillonne A., Chang B. H., Quast M. J., Gorenstein D., Chen K. H., Chan L. (2000) Nat. Genet. 26, 474–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mottagui-Tabar S., Rydén M., Löfgren P., Faulds G., Hoffstedt J., Brookes A. J., Andersson I., Arner P. (2003) Diabetologia 46, 789–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Puri V., Konda S., Ranjit S., Aouadi M., Chawla A., Chouinard M., Chakladar A., Czech M. P. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 34213–34218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Magnusson B., Gummesson A., Glad C. A., Goedecke J. H., Jernås M., Lystig T. C., Carlsson B., Fagerberg B., Carlsson L. M., Svensson P. A. (2008) Metabolism 57, 1307–1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nordström E. A., Rydén M., Backlund E. C., Dahlman I., Kaaman M., Blomqvist L., Cannon B., Nedergaard J., Arner P. (2005) Diabetes 54, 1726–1734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gerin I., Dolinsky V. W., Shackman J. G., Kennedy R. T., Chiang S. H., Burant C. F., Steffensen K. R., Gustafsson J. A., MacDougald O. A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 23024–23031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Juvet L. K., Andresen S. M., Schuster G. U., Dalen K. T., Tobin K. A., Hollung K., Haugen F., Jacinto S., Ulven S. M., Bamberg K., Gustafsson J. A., Nebb H. I. (2003) Mol. Endocrinol. 17, 172–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Le Lay S., Robichon C., Le Liepvre X., Dagher G., Ferre P., Dugail I. (2003) J. Lipid Res. 44, 1499–1507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Darimont C., Avanti O., Zbinden I., Leone-Vautravers P., Mansourian R., Giusti V., Macé K. (2006) Biochimie 88, 309–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stenson B. M., Rydén M., Steffensen K. R., Wåhlén K., Pettersson A. T., Jocken J. W., Arner P., Laurencikiene J. (2009) Endocrinology 150, 4104–4113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dahlman I., Nilsson M., Jiao H., Hoffstedt J., Lindgren C. M., Humphreys K., Kere J., Gustafsson J. A., Arner P., Dahlman-Wright K. (2006) Pharmacogenet. Genomics 16, 881–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ross S. E., Erickson R. L., Gerin I., DeRose P. M., Bajnok L., Longo K. A., Misek D. E., Kuick R., Hanash S. M., Atkins K. B., Andresen S. M., Nebb H. I., Madsen L., Kristiansen K., MacDougald O. A. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 5989–5999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dicker A., Le Blanc K., Aström G., van Harmelen V., Götherström C., Blomqvist L., Arner P., Rydén M. (2005) Exp. Cell Res. 308, 283–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. van Harmelen V., Skurk T., Hauner H. (2005) Methods Mol. Med. 107, 125–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dicker A., Kaaman M., van Harmelen V., Astrom G., Blanc K. L., Ryden M. (2005) Int. J. Obesity 29, 1413–1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shimizu M., Blaak E. E., Lonnqvist A., Gafvels M. E., Arner P. (1996) Pharmacol. Toxicol. 78, 254–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ryden M., Dicker A., van Harmelen V., Hauner H., Brunnberg M., Perbeck L., Lonnqvist F., Arner P. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 1085–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hellmér J., Arner P., Lundin A. (1989) Anal. Biochem. 177, 132–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lowe D. B., Magnuson S., Qi N., Campbell A. M., Cook J., Hong Z., Wang M., Rodriguez M., Achebe F., Kluender H., Wong W. C., Bullock W. H., Salhanick A. I., Witman-Jones T., Bowling M. E., Keiper C., Clairmont K. B. (2004) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 14, 3155–3159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tusher V. G., Tibshirani R., Chu G. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 5116–5121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mairal A., Langin D., Arner P., Hoffstedt J. (2006) Diabetologia 49, 1629–1636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001) Methods 25, 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jakobsson T., Venteclef N., Toresson G., Damdimopoulos A. E., Ehrlund A., Lou X., Sanyal S., Steffensen K. R., Gustafsson J. A., Treuter E. (2009) Mol. Cell 34, 510–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ulven S. M., Dalen K. T., Gustafsson J. A., Nebb H. I. (2004) J. Lipid Res. 45, 2052–2062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Krintel C., Osmark P., Larsen M. R., Resjö S., Logan D. T., Holm C. (2008) PloS. one 3, e3756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dalen K. T., Schoonjans K., Ulven S. M., Weedon-Fekjaer M. S., Bentzen T. G., Koutnikova H., Auwerx J., Nebb H. I. (2004) Diabetes 53, 1243–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miyoshi H., Perfield J. W., 2nd, Obin M. S., Greenberg A. S. (2008) J. Cell. Biochem. 105, 1430–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Laurencikiene J., van Harmelen V., Arvidsson Nordström E., Dicker A., Blomqvist L., Näslund E., Langin D., Arner P., Rydén M. (2007) J. Lipid Res. 48, 1069–1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bézaire V., Mairal A., Anesia R., Lefort C., Langin D. (2009) FEBS Lett. 583, 3045–3049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Granneman J. G., Moore H. P., Krishnamoorthy R., Rathod M. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 34538–34544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Baranowski M. (2008) J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 59, Suppl. 7, 31–55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang Y., Rogers P. M., Su C., Varga G., Stayrook K. R., Burris T. P. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 26332–26339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Seo J. B., Moon H. M., Kim W. S., Lee Y. S., Jeong H. W., Yoo E. J., Ham J., Kang H., Park M. G., Steffensen K. R., Stulnig T. M., Gustafsson J. A., Park S. D., Kim J. B. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 3430–3444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Krause B. R., Hartman A. D. (1984) J. Lipid Res. 25, 97–110 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sekiya M., Yahagi N., Matsuzaka T., Takeuchi Y., Nakagawa Y., Takahashi H., Okazaki H., Iizuka Y., Ohashi K., Gotoda T., Ishibashi S., Nagai R., Yamazaki T., Kadowaki T., Yamada N., Osuga J. I., Shimano H. (2007) J. Lipid Res. 48, 1581–1591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Commerford S. R., Vargas L., Dorfman S. E., Mitro N., Rocheford E. C., Mak P. A., Li X., Kennedy P., Mullarkey T. L., Saez E. (2007) Mol. Endocrinol. 21, 3002–3012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dalen K. T., Ulven S. M., Bamberg K., Gustafsson J. A., Nebb H. I. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 48283–48291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schultz J. R., Tu H., Luk A., Repa J. J., Medina J. C., Li L., Schwendner S., Wang S., Thoolen M., Mangelsdorf D. J., Lustig K. D., Shan B. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 2831–2838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.