Abstract

Phospholemman (PLM), a member of the FXYD family of regulators of ion transport, is a major sarcolemmal substrate for protein kinases A and C in cardiac and skeletal muscle. In the heart, PLM co‐localizes and co‐immunoprecipitates with Na+‐K+‐ATPase, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, and L‐type Ca2+ channel. Functionally, when phosphorylated at serine68, PLM stimulates Na+‐K+‐ATPase but inhibits Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in cardiac myocytes. In heterologous expression systems, PLM modulates the gating of cardiac L‐type Ca2+ channel. Therefore, PLM occupies a key modulatory role in intracellular Na+ and Ca2+ homeostasis and is intimately involved in regulation of excitation–contraction (EC) coupling. Genetic ablation of PLM results in a slight increase in baseline cardiac contractility and prolongation of action potential duration. When hearts are subjected to catecholamine stress, PLM minimizes the risks of arrhythmogenesis by reducing Na+ overload and simultaneously preserves inotropy by inhibiting Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. In heart failure, both expression and phosphorylation state of PLM are altered and may partly account for abnormalities in EC coupling. The unique role of PLM in regulation of Na+‐K+‐ATPase, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, and potentially L‐type Ca2+ channel in the heart, together with the changes in its expression and phosphorylation in heart failure, make PLM a rational and novel target for development of drugs in our armamentarium against heart failure. Clin Trans Sci 2010; Volume 3: 189–196

Keywords: phospholemman, ion transport regulator, protein kinase

Introduction

Phospholemman (PLM) was initially identified by Larry Jones in 1985 1 as a 15‐kDa sarcolemmal (SL) protein that is phosphorylated in response to isoproterenol and is distinct from phospholamban (PLB). 1 Follow‐up studies indicated that this 15‐kDa SL protein is also phosphorylated by protein kinase C 2 and α‐adrenergic agonists. 3 In 1991, this 15‐kDa SL phosphoprotein was purified, the complete protein sequence determined by the Edman degradation, the cDNA cloned, and the name “phospholemman” was coined. 4 In 1997, the human PLM gene is localized to chromosome 19q13.1. 5

PLM is synthesized as a 92 amino acid peptide containing at its N‐terminus a 20 amino acid signal peptide that is cleaved off during processing. The mature protein contains 72 amino acid residues with a calculated molecular weight of 8,409, but a mobility of approximately15 kDa in sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE) gels. The first 17 amino acid residues lie in the extracellular domain. The transmembrane (TM) region contains 20 amino acids (residues 18–37) while the remaining 35 amino acids (residues 38–72) at the C‐terminus are in the cytoplasm. Palmer et al. 4 also noted sequence homology between PLM and γ‐subunit of Na+‐K+‐ATPase, as well as a short region of sequence similarity between PLM (at its C‐terminus facing the cytoplasm) and PLB (at its N‐terminus also facing the cytoplasm). This region of sequence similarity (RSSIRRLST69 in PLM and RSAIRRAST17 in PLB) contains serines and threonines that are potential phosphorylation sites. Indeed, serine68 in PLM and serine16 in PLB are phosphorylated by protein kinase A (PKA). 6 , 7

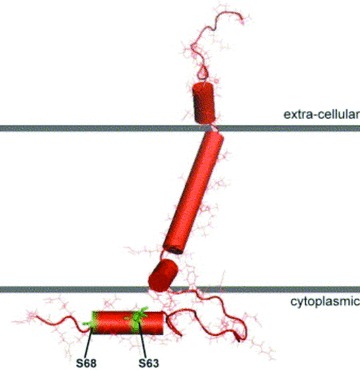

The extracellular N‐terminus of PLM contains an FXYD motif, and the cytoplasmic tail of dog, human, and rat PLM contains three serines (at residues 62, 63, and 68) and one threonine (at residue 69) but threonine69 is replaced by serine in mouse PLM. By nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) 8 and infrared spectroscopy, 9 the TM domain of PLM reconstituted in liposomes is an α‐helix with a maximum tilt of 15–17°. Specifically, NMR spectroscopic studies of highly purified PLM in model micelles indicate that the molecule consists of four α‐helices: H1 (residues 12–17) is in the extracellular N‐terminus, H2 (residues 22–38) is the main TM helix followed by the short H3 (residues 39–45), and H4 (residues 60–68) in the C‐terminus is connected to H3 by a flexible linker ( Figure 1 ). 10 In vivo, PKA phosphorylates serine68 while protein kinase C (PKC) phosphorylates serine63 and serine68 of PLM. 7 In vitro studies using PLM fragments suggest that PKA also phosphorylates serine63 while PKC phosphorylates threonine69. 11 In adult rat myocytes, approximately 46% of serine68 and approximately16% of serine63 are estimated to be phosphorylated in the resting state. 12 Using phospho‐specific anti‐PLM antibodies, 11 , 13 approximately 30–40% of PLM in adult rat myocytes 11 , 14 and approximately 25% of PLM in guinea pig myocytes 15 are phosphorylated under basal conditions. In transfected human embryonic kidney (HEK)293 cells, approximately 30–45% of exogenous PLM is phosphorylated under resting conditions. 16

Figure 1.

Molecular model of phospholemman. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies of highly purified phospholemman in micelles revealed four helices of the protein with a single transmembrane domain (after Francesca Marassi). 8 , 10 The FXYD motif is in the extracellular domain and the important serine63 and serine68 are in the cytoplasm.

Based on observations on Xenopus oocytes in which PLM is overexpressed, Randall Moorman suggested that PLM is a hyperpolarization‐activated anion‐selective channel. 17 When reconstituted in lipid bilayers, PLM forms a channel that is highly selective for taurine 18 and is thought to be involved in regulation of cell volume in noncardiac tissues. 19 , 20 The function of PLM in the heart remains unknown until the dawning of the 21st century.

PLM: Founding Member of the FXYD Family of Regulators of Ion Transport

In 2000, Kathy Sweadner described the FXYD family of regulators of ion transport, 21 of which PLM is the first cloned member (FXYD1). At present, there are at least 12 known FXYD proteins, including γ‐subunit of Na+‐K+‐ATPase (FXYD2), mammary‐associated tumor 8 kDa (MAT‐8 or FXYD3), channel‐inducing factor (CHIF or FXYD4), dysadherin (FXYD5; also known as related to ion channel [RIC]), phosphohippolin (FXYD6), FXYD7, and phospholemman‐shark (PLM‐S) (FXYD10; the shark homolog of PLM). As a family, FXYD proteins are found predominantly in tissues involved in solute and fluid transport (kidney, colon, pancreas, mammary gland, liver, lung, prostate, and placenta) or are electrically excitable (heart, skeletal, and neural tissues). All FXYD members have the signature FXYD motif in the N‐terminus and a single TM domain. Except for γ‐subunit of Na+‐K+‐ATPase, all other known members of the FXYD gene family have at least one serine or threonine within the cytoplasmic tail, indicating potential phosphorylation sites. PLM is unique among FXYD proteins in that it has consensus sequence for phosphorylation by PKA (RRXS), PKC (RXXSXR), and never‐in‐mitosis aspergillus (NIMA) kinase (FRXS/T). PLM is also a substrate for myotonic dystrophy protein kinase. 22 The γ‐subunit of Na+‐K+‐ATPase is the only member in the FXYD family boasting two alternative splice variants (FXYD2a and FXYD2b).

PLM: Regulator of Cardiac Na+‐K+‐ATPase

In 2002, Kaethi Geering demonstrated that PLM co‐immunoprecipitates with α‐subunits of Na+‐K+‐ATPase in bovine sarcolemma. 23 In isolated adult rat cardiac myocytes, PLM co‐localizes with α‐subunits of Na+‐K+‐ATPase ( Figure 2 ). When co‐expressed with α‐ and β‐subunits of Na+‐K+‐ATPase in Xenopus oocytes, PLM modulates Na+‐K+‐ATPase activity primarily by decreasing Km for Na+ and K+ without affecting Vmax. 23 Data obtained from cardiac myocytes or homogenates indicate that PLM inhibits Na+‐K+‐ATPase by reducing its apparent affinities for intracellular Na+ 24 , 25 and external K+ 26 or decreasing Vmax. 11 , 14 , 15 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 When phosphorylated at serine68, PLM relieves its inhibition on Na+‐K+‐ATPase by decreasing its apparent Km for Na+ 25 , 32 but not for K+ 26 and increasing Vmax. 15 , 28 , 32

Figure 2.

Phospholemman co‐localizes with α1‐subunit of Na+‐K+‐ATPase. Indirect immunofluorescence of adult rat ventricular myocytes doubly labeled with mouse monoclonal antibody against α1‐subunit of Na+‐K+‐ATPase (A) and rabbit polyclonal anti‐PLM antibody (B) are shown. Primary antibodies are visualized with Alexa Fluor 488‐labeled goat anti‐mouse IgG (A) and Alexa Fluor 594‐ labeled goat anti‐rabbit IgG (B). Note the orange color in the merged image (C), indicating co‐localization of PLM and Na+‐K+‐ATPase. Bar = 5 μm.

In terms of molecular interactions between PLM and Na+‐K+‐ATPase, mutational analysis suggests that FXYD proteins (FXYD2, 4 and 7) interact with TM9 segment of Na+‐K+ ‐ATPase. 33 Co‐immunoprecipitation and covalent cross‐linking studies demonstrate that the TM segment of PLM is close to TM2 segment of Na+‐K+‐ATPase. 34 Molecular modeling based on Ca2+‐ATPase crystal structure in the E1ATP‐bound conformation suggests that the single TM segment of FXYD proteins docks into the groove between TM segments 2, 6, and 9 of the α‐subunit of Na+‐K+‐ATPase. 34 High resolution crystal structure (2.4 Angstrom) of shark rectal gland Na+‐K+‐ATPase in the E2.2K+.Pi state indicates that FXYD proteins interact almost exclusively with the outside of TM9 of the α‐subunit (journal cover figure). 35 The role of the signature FXYD(Y) motif is to stabilize interactions between α‐ and β‐subunits of Na+‐K+‐ATPase and residue D (in the FXYD motif) caps the helix and defines the membrane border. 35 In transfected HEK293 cells, PLM interacts with either α1‐ or α2‐subunit of Na+‐K+‐ATPase in a 1:1 stoichiometry. 24 Phosphorylation of PLM‐S causes it to dissociate from shark Na+‐K+‐ATPase. 36 However, phosphorylation of PLM does not cause it to dissociate from the α‐subunit of Na+‐K+‐ATPase. 15 , 24 Despite NMR studies of PLM in micelles showing no major conformational changes on phosphorylation of serine68 in intact cells examined with fluorescence resonance energy transfer, interaction between PLM and Na+‐K+‐ATPase is decreased on phosphorylation of PLM. 24 , 37 , 38

There are four isoforms of the catalytic α‐subunits of Na+‐K+‐ATPase and expression of a particular α‐isoform is both tissue and species dependent. 39 Human 40 , 41 and rabbit 42 hearts are known to express α1‐, α2‐, and α3‐isoforms while rodent hearts express only α1‐ (ouabain‐resistant) and α2‐isoforms of Na+‐K+‐ATPase. 15 , 32 , 43 , 44 In both adult rat and mouse ventricles, the ouabain‐sensitive α2‐subunit is preferentially localized to the t‐tubules 43 , 45 and its activity represents <25% of total Na+‐K+‐ATPase activities. 32 , 43 , 44 PLM co‐immunoprecipitates all three α‐subunits of Na+‐K+‐ATPase in human and rabbit, 42 α1‐ and α2‐subunits in mouse 32 and bovine, 23 but only α1‐subunit in rat 28 and guinea pig 15 hearts. In both wild‐type (WT) mouse 32 and guinea pig 15 ventricular myocytes, PLM regulates the activity of α1‐but not α2‐isoform of Na+‐K+‐ATPase. This conclusion must be tempered with the recent finding that in “SWAP” mouse 46 in which the ouabain affinities of the α‐subunits are reversed, PLM regulates the apparent affinities for Na+ of both α1‐ and α2‐subunits of Na+‐K+‐ATPase. 24 Together with observations made on Xenopus oocytes heterologously expressing PLM and Na+‐K+‐ATPase, 23 , 47 it is likely the PLM regulates both α1‐ and α2‐subunits of Na+‐K+‐ATPase.

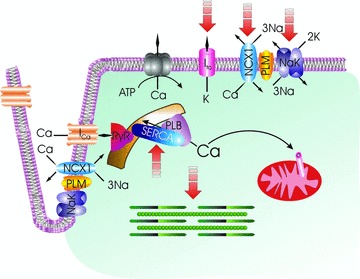

Cardiac Excitation–Contraction (EC) Coupling

Both α1‐ 46 and α2‐subunits 45 of Na+‐K+‐ATPase have been implicated in the control of cardiac contractility. Therefore, modulation of Na+‐K+‐ATPase activity suggests an important role for PLM in regulation of inotropy. We will give a brief overview of cardiac EC coupling ( Figure 3 ) that has previously been reviewed by Don Bers in detail. 48 During the upstroke of the action potential, Na+ enters via Na+ channels and further depolarizes the sarcolemma. Depolarization activates the voltage‐dependent L‐type Ca2+ channels, allowing extracellular Ca2+ to enter as an inward current (ICa), which contributes to the plateau phase of the action potential. Some Ca2+ also enters via the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX1) operating in the reverse mode (3 Na+ out: 1 Ca2+ in) during this phase of the action potential, although the amount and duration of Ca2+ influx via reverse Na+/Ca2+ exchange vary among species. Ca2+ entry triggers release of approximately two‐thirds of Ca2+ stored in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) via the ryanodine receptor. The combination of Ca2+ influx and SR Ca2+ release abruptly raises the free intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i), allowing Ca2+ to bind to troponin C and activate the contractile apparatus. Relaxation requires termination of SR Ca2+ release, and [Ca2+]i to decline so that Ca2+ can dissociate from troponin C. About 70–92% of myoplasmic Ca2+ is resequestered into the SR by sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+‐ATPase (SERCA2) that is under the control of PLB. To maintain steady‐state Ca2+ balance, Ca2+ that has entered during systole is mainly extruded by NCX1 operating in the forward mode (3 Na+ in: 1 Ca2+ out), with the SL Ca2+‐ATPase playing a smaller role. Likewise, the small amount of Na+ that has entered during depolarization is extruded by Na+‐K+‐ATPase during diastole. In this way, the cardiac myocyte maintains beat‐to‐beat Ca2+ and Na+ balance. Outward K+ currents contribute to repolarization phase of the action potential.

Figure 3.

Cardiac excitation–contraction coupling. Membrane depolarization is initiated by opening of the Na+ channel (not shown) with Na+ entry. Extracellular Ca2+ enters via L‐type Ca2+ channel (ICa) and Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX1), causing Ca2+ release from the ryanodine receptor (RyR) in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). Ca2+ binds to troponin and initiates myofilament contraction. During diastole, Ca2+ is pumped back to the SR by SR Ca2+‐ATPase (SERCA) under the control of phospholamban (PLB). A small amount of Ca2+ is also taken up by the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter. The amount of Ca2+ that has entered during systole is extruded by Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and to a lesser extent by sarcolemmal Ca2+‐ATPase. Na+ that has entered via Na+ channel and Na+/Ca2+ exchanger is pumped out by Na+‐K+‐ATPase. Repolarization is mediated by opening of K+ channels (only the transient outward K+ current Ito responsible for early repolarization is shown). Phospholemman (PLM) associates with and is an endogenous regulator of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, Na+‐K+‐ATPase, and possibly L‐type Ca2+ channel. Na+/Ca2+ exchanger is depicted as operating in the forward mode (Ca2+ efflux) in the sarcolemma and reverse mode (Ca2+ influx) in the t‐tubules. Broken arrows point to ion transporters, ion channels, and myofilaments that are altered after myocardial infarction.

Among the many transporters and ion channels involved in cardiac Ca2+ fluxes, NCX1 is unique in that during an action potential, it participates in Ca2+ influx, [Ca2+]i transient buffering, and Ca2+ efflux. 48 The direction of Ca2+ flux (in or out) depends on the thermodynamic driving force determined by the membrane potential (Em) and the concentrations of Na+ and Ca2+ ions sensed by NCX1. Other than the determinants of its thermodynamic driving force, remarkably little is known about the regulation of NCX1.

In the heart, inhibition of Na+‐K+‐ATPase by PLM is expected to raise intracellular Na+ concentration ([Na+]i), thereby decreasing the thermodynamic driving force for forward Na+/Ca2+ exchange (Ca2+ efflux) and increasing the driving force for reverse Na+/Ca2+ exchange (Ca2+ influx). Both these actions are expected to increase [Ca2+]i and SR Ca2+ load, thereby enhancing cardiac contractility. Indeed, inhibition of Na+‐K+‐ATPase with secondary effects on NCX1 has long been proposed to be the mechanism of positive inotropy of digitalis glycosides. 49

PLM: First Endogenous Regulator of Cardiac NCX1

When PLM is overexpressed (1.4‐ to 3.5‐fold) in adult rat left ventricular (LV) myocytes by adenovirus‐mediated gene transfer, 14 , 50 , 51 expression of SERCA2, α1‐ and α2‐subunits of Na+‐K+‐ATPase, NCX1, and calsequestrin remains unchanged. As expected, Na+‐K+‐ATPase current (Ipump) is decreased in rat myocytes overexpressing PLM, primarily as a result of decrease in Vmax rather than changes in apparent Km for Na+ or K+. 14 A totally unexpected finding is that both contraction and [Ca2+]i transient amplitudes (5.0 mM [Ca2+]o, 1 Hz, 37°C) in myocytes overexpressing PLM are lower, rather than higher, when compared to control rat myocytes overexpressing green fluorescent protein (GFP). 50 This serendipitous but critical observation is inconsistent with the theoretical prediction that inhibition of Na+‐K+‐ATPase by PLM leads to enhanced cardiac contractility. Because the contractile phenotype of myocytes overexpressing PLM is similar to that observed in myocytes in which NCX1 is downregulated, 52 and opposite to that in which NCX1 is overexpressed, 53 we were the first to propose in 2002 that PLM directly regulates NCX1 activity, independent of its effects on Na+‐K+‐ATPase. 50 Follow‐up studies in adult rat myocytes demonstrate that PLM co‐localizes with NCX1 to the sarcolemma and t‐tubules, 51 that PLM co‐immunoprecipitates with NCX1, 54 , 55 that overexpression of PLM inhibits Na+/Ca2+ exchange current (INaCa), 12 , 51 and that downregulation of PLM by antisense increases INaCa. 55 Using HEK293 cells that are devoid of NCX1 and PLM, we demonstrated that cells transfected with NCX1 display the characteristic INaCa, and that cells co‐transfected with PLM demonstrate inhibition of INaCa as well as Na+‐dependent Ca2+ uptake. 54 In addition, PLM co‐immunoprecipitates with NCX1 in transfected HEK293 cells, 54 pig SL vesicles, 54 and guinea pig ventricular myocyte membranes. 56 In cardiac myocytes isolated from PLM‐null mice, INaCa was higher in PLM‐null myocytes 57 despite no differences in NCX1 protein levels. 58 The cumulative evidence obtained from three model systems: adult rat myocytes, HEK293 cells, and PLM‐null mice are all consistent with our hypothesis that PLM directly regulates NCX1. 59

NCX1 is a 938 amino acid (939 amino acid in the rat) peptide consisting of an extracellular N‐terminal domain comprising the first five TM segments, a large intracellular loop (residues 218–764), and an intracellular C‐terminal domain consisting of the last four TM segments. 60 , 61 The α‐repeats of TM segments 2, 3, and 7 of NCX1 are important in ion transport activity 62 , 63 while the large intracellular loop contains the regulatory domains of the exchanger. 64 , 65 , 66 Using glutathione S‐transferase pulldown assay, we demonstrated that neither the N‐ nor the C‐terminal TM domains of NCX1 associates with PLM. 67 Rather, the cytoplasmic tail of PLM both physically and functionally interacts with the intracellular loop (residues 218–358) of NCX1. 67 Using overlapping NCX1 loop deletion mutants, we further showed that PLM interacts with NCX1 at two distinct regions encompassing residues 238–270 and 300–328. 16

There are significant differences between the mechanisms by which PLM regulates the activities of NCX1 and Na+‐K+‐ATPase. First, phosphorylation of PLM at serine68 relieves its inhibition of Na+‐K+‐ATPase. 15 , 25 , 28 By contrast, PLM phosphorylated at serine68 is the active species that inhibits NCX1. 12 , 57 Second, the TM segment of FXYD proteins (and by inference PLM) interacts with TM segments 2, 6, and 9 of α‐subunit of Na+‐K+‐ATPase. 33 , 34 , 35 By contrast, TM43, a PLM mutant with its cytoplasmic tail truncated, targets correctly to the sarcolemma 12 but does not co‐immunoprecipitate NCX1 67 and has no effect on myocyte contractility, 12 suggesting little‐to‐no association between the TM domains of PLM and NCX1.

PLM: Regulator of Cardiac L‐Type Calcium Channel

In guinea pig cardiac myocytes, Blaise Peterson recently demonstrated that PLM co‐immunoprecipitates not only NCX1 but also L‐type Ca2+ channels (Cav1.2). 56 In transfected HEK293 cells and using Ba2+ as charge carrier, PLM modulates gating kinetics of Cav1.2 but not Cav2.1 (P/Q‐type) or Cav2.2 (N‐type) Ca2+ channels. 56 Specifically, PLM was found to modulate four important gating processes of Cav1.2 channels: (i) activation kinetics were slowed at voltages near the threshold for channel activation; (ii) deactivation kinetics were slowed following voltage commands mimicking human cardiac action potential; (iii) voltage‐dependent inactivation was enhanced at voltages corresponding to the plateau phase of the cardiac action potential; and (iv) increased number of channels enter a deep inactivated state from which recovery is slow. When a human cardiac action potential is imposed on HEK293 cells transfected with Cav1.2 channels, PLM increases Ca2+ influx during the repolarization phase of the cardiac action potential. 56 The role of PLM phosphorylation in the regulation of Cav1.2 gating kinetics remains to be elucidated.

The possibility that in cardiac myocytes, PLM may potentially modulate gating kinetics of L‐type Ca2+ channels, in addition to its known effects on Na+‐K+‐ATPase and NCX1, renders the interpretation of the effects of PLM expression/phosphorylation on cardiac contractility extremely complex. However, heterologous expression systems often do not reproduce a protein’s native milieu and may distort the stoichiometry of interaction between proteins. A good example is the potentiation of ICa by adrenergic agonists, so readily observed in cardiac myocytes, 68 , 69 has yet to be reproduced in heterologous expression systems. 70 In addition, using Ca2+ as charge carrier, we did not detect any differences in maximal ICa amplitude, fast and slow inactivation time constants, slope conductance, and test potential at which maximal ICa occurs between WT and PLM‐null myocytes. 58 Therefore, the physiological significance of regulation of Cav1.2 by PLM, while intriguing, remains to be established in cardiac myocytes.

Regulation of Single Myocyte Contraction by PLM: Na+‐K+‐ATPase versus NCX1

In cultured myocytes isolated from PLM‐null mice and expressing the phosphomimetic PLM S68E mutant, INaCa but not Ipump is inhibited. 31 This is associated with decreased [Ca2+]i transient and contraction amplitudes (1 Hz, 37°C) measured at 5.0 but not at 1.8 mM [Ca2+]o: the phenotype that we observed when NCX1 is downregulated 52 or when PLM is overexpressed. 50 By contrast, when cultured PLM‐null myocytes overexpress the nonphosphorylable PLM S68A mutant, Ipump but not INaCa is inhibited. 31 This is associated with no changes in [Ca2+]i transient and contraction amplitudes at both [Ca2+]o. Therefore, under conditions in which [Ca2+]o is varied to manipulate the thermodynamic driving force for NCX1, regulation of single cardiac myocyte contractility by PLM is mediated by its inhibitory effects on NCX1 rather than Na+‐K+‐ATPase.

When myocytes are subjected to rapid pacing (2 Hz) and isoproterenol (1 μM) stimulation, [Na+]i initially increases but then starts to decline in WT but not in PLM‐null myocytes. 32 , 71 [Ca2+]i transient and contraction amplitudes follow the time course of [Na+]i: initially increase followed by decline in WT but not PLM‐null myocytes. When pacing was slowed to 0.5 Hz to minimize the steep rise in [Na+]i, both [Ca2+]i transient and contraction amplitudes increase to a lower steady‐state level without any time‐dependent decline in both WT and PLM‐null myocytes. 32 These observations suggest that under conditions of high [Na+]i, phosphorylated PLM activates Na+‐K+‐ATPase to limit intracellular Na+ overload at the expense of reduced inotropy. Therefore, at the level of a single myocyte, PLM can be shown to regulate Na+ and Ca2+ fluxes (and hence [Ca2+]i transients and contractility), by either NCX1 or Na+‐K+‐ATPase, depending on experimental manipulations.

Regulation of In Vivo Contractility by PLM: Studies with PLM‐Null Mice

In 2005, Amy Tucker made a major contribution to the understanding of PLM and cardiac function by successfully engineering the PLM‐null mouse. 72 There is mild cardiac hypertrophy, 27 , 32 , 72 at least partly due to increased fibrosis in PLM‐null hearts 32 since neither LV myocyte length and width 58 nor whole cell membrane capacitance (a measure of cell surface area) 25 , 58 is different between WT and PLM‐null myocytes. There are no differences in protein levels of α1‐, α2‐, β1‐, and β2‐subunits of Na+‐K+‐ATPase, SERCA2, PLB, NCX1, and calsequestrin between WT and congenic PLM‐null hearts. 27 , 58 The majority of proteins that are differentially expressed between WT and PLM‐null hearts are involved in cell metabolism. 27 Na+‐K+‐ATPase enzymatic activity, 27 Ipump, 25 , 31 and INaCa 31 , 57 are higher in PLM‐null hearts, as expected from the relief of inhibition of Na+‐K+‐ATPase and NCX1. There are no changes in ICa amplitudes but action potential duration is prolonged in PLM‐null myocytes. 58

The effects of PLM on cardiac contractility in vivo are complicated and controversial. Using magnetic resonance imaging, Amy Tucker 72 initially reported cardiac hypertrophy and increased ejection fraction in PLM‐null hearts of mice with mixed genetic background (C57BL/6 and 129/SvJ). By contrast, in vivo hemodynamic measurements made by Mike Shattock with conductance catheter introduced by LV puncture in open‐chest mice demonstrate no significant differences in measured cardiac indices between WT and PLM‐null mice of congenic (C57BL/6) background. 27 Our own data in closed‐chest catheterized mice show slightly increased baseline +dP/dt in congenic PLM‐null hearts. 32 Different genetic backgrounds, noninvasive imaging versus invasive catheterization, different anesthesia, blood loss associated with opening the chest and LV puncture, and heat dissipation in an open‐chest mouse, may account for these discrepancies. The weight of current evidence, however, indicates that PLM‐null hearts contract just as well, if not better, than WT hearts. This is inconsistent with the expectation that with relief of inhibition of Na+‐K+‐ATPase, PLM‐null hearts should exhibit lower contractility when compared to WT hearts.

PLM: A Novel Cardiac Stress Protein

When PLM is overexpressed in adult rat LV myocytes, contractility and [Ca2+]i transient amplitudes measured under physiological conditions (1.8 mM [Ca2+]o, 1 Hz, 37°C) are only slightly less than those measured in control myocytes expressing GFP. 50 Likewise, contractility and [Ca2+]i transient amplitudes (1.8 mM [Ca2+]o, 1 Hz, 37°C) are similar between WT and PLM‐null myocytes. 58 Only when the thermodynamic driving force for NCX1 is altered by varying [Ca2+]o (0.6 or 5.0 mM) are the effects of PLM on myocyte contractility and [Ca2+]i transients evident. 12 , 50 , 51 , 55 , 58 The effects of PLM on Na+‐K+‐ATPase are also not apparent in myocytes under resting conditions: basal [Na+]i is similar between WT and PLM‐null myocytes. 25 , 32 Therefore, under resting conditions, PLM is functionally quiescent.

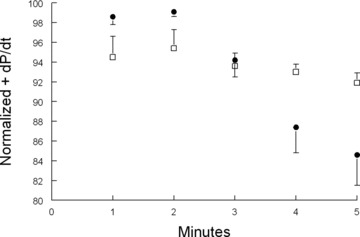

In the intact heart, β‐adrenergic stimulation increases chronotropy leading to more frequent depolarizations and increased Na+ entry. In addition, ICa and SERCA2 activity are also increased in response to β‐adrenergic stimulation, resulting in increased Ca2+ entry and SR Ca2+ loading. Elevated SR Ca2+ content available for release largely accounts for the enhanced inotropy associated with β‐adrenergic stimulation. Increased Ca2+ entry must be balanced by greater Ca2+ efflux mediated by forward NCX1, thereby bringing more Na+ into the myocyte. This, if unchecked, will lead to cellular Na+ and Ca2+ overload. Don Bers 71 hypothesized that β‐adrenergic agonists increase PLM phosphorylation at serine68, thereby activating Na+‐K+‐ATPase and resulting in lower [Na+]i. The lower [Na+]i promotes Ca2+ efflux via NCX1, resulting in lower [Ca2+]i transient and contraction amplitudes. 32 , 71 Indeed, when hearts in vivo are stressed with maximal doses of isoproterenol, inotropy (+dP/dt) rises to a peak within 2 minutes followed by decline in WT but not PLM‐null hearts ( Figure 4 ). Therefore, when hearts are under duress, one of the major functions of PLM is to limit Na+ and Ca2+ overload, thereby minimizing the risks of arrhythmogenesis apparently at the expense of reduced inotropy.

Figure 4.

Effects of activation of Na+‐K+‐ATPase by phosphorylated phos‐pholemman on β‐adrenergic response in vivo. Shown are normalized in vivo hemodynamics (+dP/dt) of anesthetized wild type (•; n= 9) and phospholemman‐null (€n= 14) mice after stimulation with 25 ng of isoproterenol. Note time‐dependent decline of +dP/dt in wild type but not phospholemman‐null hearts. Phospholemman phosphorylated at serine68 activates Na+‐K+‐ATPase, 25 , 32 leading to decreases in [Na+]i in wild type but not phospholemman‐null cardiac myocytes. 32 , 71

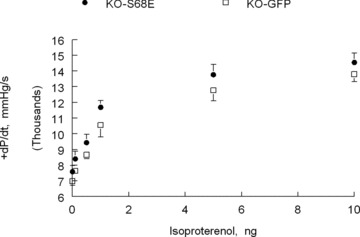

On the other hand, reduced cardiac contractility under conditions of fight or flight is clearly not in the best interests of the organism. In 2006, we proposed a coordinated paradigm in which PLM, upon phosphorylation at serine68, enhances Na+‐K+‐ATPase activity to minimize risks of arrhythmogenesis but inhibits NCX1 to preserve inotropy during stress. 57 Our recent experiments provide support for this hypothesis. In PLM‐null hearts in which isoproterenol has little‐to‐no effects on Na+‐K+‐ATPase, 25 , 32 injection of recombinant adeno‐associated virus (serotype 9) expressing the phosphomimetic PLM S68E mutant (rAAV9‐S68E) directly into the LV resulted in expression of the mutant protein after 4–5 weeks. PLM S68E mutant inhibits NCX1 but not Na+‐K+‐ATPase. 31 Isoproterenol stimulation resulted in similar increases in [Na+]i but higher +dP/dt in PLM‐null hearts expressing PLM S68E mutant when compared to PLM‐null hearts expressing GFP ( Figure 5 ). Therefore, inhibition of NCX1 by phosphorylated PLM preserves cardiac contractility under stressful situations.

Figure 5.

Effects of inhibition of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger by phosphorylated phospholemman on β‐adrenergic response in vivo. Left ventricles of phospholemman‐null (KO) mice are injected with recombinant adeno‐associated virus, serotype 9, expressing either green fluorescent protein (GFP) (€; n= 5) or the phosphomimetic phospholemman S68E mutant (•; n= 7). S68E mutant inhibits Na+/Ca2+ exchanger but has no effect on Na+‐K+‐ATPase. 12 , 31 , 57 Five weeks after virus injection, in vivo hemodynamics (+dP/dt) are measured in anesthetized mice. 32 Note that with increasing doses of isoproterenol, KO‐S68E hearts contract significantly better than KO‐GFP hearts. Since isoproterenol has no effect on Na+‐K+‐ATPase in phospholemman‐null myocytes, 25 , 32 [Na+]i is similar between KO‐S68E and KO‐GFP hearts (data not shown). Enhanced contractility in KO‐S68E hearts is therefore due to inhibition of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger by the S68E mutant.

FXYD Proteins In Aging, Exercise, and Disease

PLM expression is 2‐fold higher in neonatal rabbit ventricular membranes and declines within 10 days to the level observed in adults. 73 The decrease in PLM expression with postnatal maturation is concurrent with reduction in Na+‐K+‐ATPase and NCX1 73 and suggests tight coordination of PLM with the two ion transporters. With aging, expression of PLM in sedentary rat skeletal muscle is not altered but the level of α1‐subunit of Na+‐K+‐ATPase that co‐immunoprecipitates with PLM increases 3‐fold. 74 There are no detectable changes of association of α2‐subunit of Na+‐K+‐ATPase with PLM with aging. 74

Acute exercise (treadmill running) in rats increases SL PLM in skeletal muscle by 200–350% due to translocation, but phosphorylation at serine68 appears not to be altered. 75 When senescent rats (26‐month‐old) are subjected to endurance treadmill running for 13–14 weeks, PLM in skeletal muscle is increased by 150% when compared to sedentary senescent rats. 74 In addition, increased association of PLM with α1‐subunit of Na+‐K+‐ATPase in skeletal muscle of senescent rats (as compared to young rats) is decreased with endurance treadmill running. 74

In 2000, using cDNA microarrays containing 86 known genes and 989 unknown cDNAs, Sehl et al. 76 are the first to report that PLM is one of only 19 genes to increase after myocardial infarction (MI) in the rat. We confirmed that PLM protein levels increased 2.4‐ and 4‐fold at 3 and 7 days post‐MI, respectively, in the rat. 14 PLM overexpression may very well explain the depression in both Na+‐K+‐ATPase 77 and NCX1 78 , 79 activities observed in the post‐MI rat model. In rat hearts subjected to acute ischemia, PLM is phosphorylated that leads to profound activation of SL Na+‐K+‐ATPase. 28 In isolated perfused mouse hearts subjected to ischemia/reperfusion, protection against infarction by sildenafil is associated with increased PLM phosphorylation at serine69 that enhances Na+‐K+‐ATPase activity during reperfusion. 80 Increased Na+‐K+‐ATPase activity during acute ischemia ± reperfusion is critical in maintaining [Na+]i homeostasis in order to minimize the adverse effects of elevated [Na+]i on contractility and arrhythmogenesis. In human heart failure, protein levels of PLM in LV homogenates are reduced by 24%. 42 In a rabbit model of volume overload heart failure that is prone to arrhythmias, 81 expression of PLM is reduced by 42–48% but phosphorylation at serine68 is dramatically increased. 42 Thus, both altered expression and phosphorylation of PLM have been observed in various cardiac disease models. In this context, it is very relevant to note that the two classes of drugs that have been clinically proven to be efficacious in human heart failure, β‐adrenergic blockers (lowering PKA activity) and angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors (reducing PKC activity), both have PLM as a common target.

Sepsis is a major clinical problem that is characterized by profound hypotension, systemic vasodilatation, and depression in cardiac contractility. A wide range of inflammatory cascades is activated during systemic sepsis. 82 Increased nitric oxide (NO) by inducible NO synthase has been suggested to cause depressed cardiac contractility in sepsis. 83 In this light, Helge Rasmussen demonstrated that NO stimulates Na+‐K+‐ATPase 84 , 85 and Mike Shattock reported (in abstract form) that this is dependent on PLM. Acceleration of Na+‐K+‐ATPase activity by PLM may account for hyperpolarization and relaxation of vascular smooth muscle (vasodilatation) in addition to depression of cardiac contractility.

PLM has also been implicated in other diseases. For example, PLM is downregulated in layer II/III stellate neurons in patients with schizophrenia. 86 Rett syndrome, an X‐linked neuro‐development disorder that ranks as the second most prevalent cause of mental retardation in girls, 87 is due to heterozygous de novo mutations in the methyl‐CpG‐binding protein 2 (MeCP2) gene. MeCP2 normally represses PLM transcription through direct interactions with sequences in the PLM promoter. In patients with Rett syndrome and MeCP2‐null mice, PLM is elevated in neurons in the frontal cortex and cerebellum. 88 , 89 Increasing neuronal PLM expression is sufficient to reduce dendritic arborization and spine formation, hallmarks of neuropathology in patients with Rett syndrome.

Dominant‐negative mutation in FXYD2 (γ‐subunit of Na+‐K+‐ATPase) causes defective routing to the plasma membrane and is the cause of primary renal hypomagnesemia. 90 Increased MAT‐8 (FXYD3) expression is associated with tumor progression in human breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers. 91 Likewise, dysadherin (FXYD5) expression is altered in a wide variety of human cancers, including but not limited to breast, gastrointestinal stromal, head and neck, papillary thyroid, colorectal, nonsmall cell lung, and testicular cancers, and also epitheliod sarcoma and malignant melanoma. 92

Future Directions

The physiological role of PLM on regulation of L‐type Ca2+ channel needs to be established in its natural environment. The stoichiometry of interaction between PLM and Na+‐K+‐ATPase, PLM and NCX1, and PLM and L‐type Ca2+ channel remains to be determined in cardiac myocytes. The role of PLM in regulating cardiac contractility in vivo, both in health and disease states, needs further investigation. This will likely require development of novel genetic models. The effects of oxidative stress and NO on both PLM and Na+‐K+‐ATPase are just beginning to be addressed. For effective but specific drug targeting, the precise molecular interactions between PLM and Na+‐K+‐ATPase, and PLM and NCX1 need to be mapped out.

Conclusion

FXYD proteins are emerging not only as novel endogenous regulators of ion transport but also as important targets in many human diseases including neurological, cardiac and renal diseases, and a wide variety of cancers. PLM (FXYD1) regulates Na+‐K+‐ATPase, NCX1, and possibly L‐type Ca2+ channel in the heart. Its effects on in vivo cardiac contractility are complex and remain to be clarified. When hearts are subjected to stress, PLM minimizes risks of arrhythmogenesis and preserves inotropy. Elucidating the mechanisms by which alterations or mutations of FXYD proteins are involved in human diseases will undoubtedly provide novel and rational therapeutic targets.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1‐HL58672 and RO1‐HL74854 (JYC), RO1‐HL91096 (JER), and by an American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant F64702 (TOC).

References

- 1. Presti CF, Jones LR, Lindemann JP. Isoproterenol‐induced phosphorylation of a 15‐kilodalton sarcolemmal protein in intact myocardium. J Biol Chem. 1985; 260: 3860–3867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Presti CF, Scott BT, Jones LR. Identification of an endogenous protein kinase C activity and its intrinsic 15‐kilodalton substrate in purified canine cardiac sarcolemmal vesicles. J Biol Chem. 1985; 260: 13879–13889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lindemann JP. α‐adrenergic stimulation of sarcolemmal protein phosphorylation and slow responses in intact myocardium. J Biol Chem. 1986; 261: 4860–4867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Palmer CJ, Scott BT, Jones LR. Purification and complete sequence determination of the major plasma membrane substrate for cAMP‐dependent protein kinase and protein kinase C in myocardium. J Biol Chem. 1991; 266: 11126–11130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen LS, Lo CF, Numann R, Cuddy M. Characterization of the human and rat phospholemman (PLM) cDNAs and localization of the human PLM gene to chromosome 19q13.1. Genomics. 1997; 41: 435–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Simmerman HK, Jones LR. Phospholamban: protein structure, mechanism of action, and role in cardiac function. Physiol Rev. 1998; 78: 921–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Waalas SI, Czernik AJ, Olstad OK, Sletten K, Walaas O. Protein kinase C and cyclic AMP‐dependent protein kinase phosphorylate phospholemman, an insulin and adrenaline‐regulated membrane phosphoprotein, at specific sites in the carboxy terminal domain. Biochem J. 1994; 304: 635–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Franzin CM, Gong XM, Thai K, Yu J, Marassi FM. NMR of membrane proteins in micelles and bilayers: the FXYD family proteins. Methods (San Diego, Calif). 2007; 41: 398–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beevers AJ, Kukol A. Secondary structure, orientation, and oligomerization of phospholemman, a cardiac transmembrane protein. Protein Sci. 2006; 15: 1127–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Teriete P, Franzin CM, Choi J, Marassi FM. Structure of the Na,K‐ATPase regulatory protein FXYD1 in micelles. Biochemistry. 2007; 46: 6774–6783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fuller W, Howie J, McLatchie L, Weber R, Hastie CJ, Burness K, Pavlovic D, Shattock MJ. FXYD1 phosphorylation in vitro and in adult rat cardiac myocytes: threonine 69 is a novel substrate for protein kinase C. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009; 296: C1346–C1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Song J, Zhang XQ, Ahlers BA, Carl LL, Wang J, Rothblum LI, Stahl RC, Mounsey JP, Tucker AL, Moorman JR, Cheung JY. Serine 68 of phospholemman is critical in modulation of contractility, [Ca2+]i transients, and Na+/Ca2+ exchange in adult rat cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005; 288: H2342–H2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rembold CM, Ripley ML, Meeks MK, Geddis LM, Kutchai HC, Marassi FM, Cheung JY, Moorman JR. Serine 68 phospholemman phosphorylation during forskolin‐induced swine carotid artery relaxation. J Vasc Res. 2005; 42: 483–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang XQ, Moorman JR, Ahlers BA, Carl LL, Lake DE, Song J, Mounsey JP, Tucker AL, Chan YM, Rothblum LI, Stahl RC, Carey DJ, Cheung JY. Phospholemman overexpression inhibits Na+‐K+‐ATPase in adult rat cardiac myocytes: relevance to decreased Na+ pump activity in post‐infarction myocytes. J Appl Physiol. 2006; 100: 212–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Silverman BZ, Fuller W, Eaton P, Deng J, Moorman JR, Cheung JY, James AF, Shattock MJ. Serine 68 phosphorylation of phospholemman: acute isoform‐specific activation of cardiac Na/K ATPase. Cardiovasc Res. 2005; 65: 93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang XQ, Wang J, Carl LL, Song J, Ahlers BA, Cheung JY. Phospholemman regulates cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchanger by interacting with the exchanger’s proximal linker domain. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009; 296: C911–C921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moorman JR, Ackerman SJ, Kowdley GC, Griffin M, Mounsey JP, Chen Z, Cala SE, O’Brian JJ, Szabo G, Jones LR. Unitary anion currents through phospholemman channel molecules. Nature. 1995; 377: 737–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen Z, Jones LR, O’Brian JJ, Moorman JR, Cala SE. Structural domains in phospholemman: a possible role for the carboxyl terminus in channel inactivation. Circ Res. 1998; 82: 367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Davis CE, Patel MK, Miller JR, John JE III, Jones LR, Tucker AL, Mounsey JP, Moorman JR. Effects of phospholemman expression on swelling‐activated ion currents and volume regulation in embryonic kidney cells. Neurochem Res. 2004; 29: 177–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morales‐Mulia M, Pasantes‐Morales H, Moran J. Volume sensitive efflux of taurine in HEK 293 cells overexpressing phospholemman. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2000; 1496: 252–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sweadner KJ, Rael E. The FXYD gene family of small ion transport regulators or channels: cDNA sequence, protein signature sequence, and expression. Genomics. 2000; 68: 41–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mounsey JP, John J III, Helmke S, Bush E, Gilbert J, Roses A, Perryman M, Jones LR, Moorman JR. Phospholemman is a substrate for myotonic dystrophy protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2000; 275: 23362–23367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Crambert G, Fuzesi M, Garty H, Karlish S, Geering K. Phospholemman (FXYD1) associates with Na,K‐ATPase and regulates its transport properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002; 99: 11476–11481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bossuyt J, Despa S, Han F, Hou Z, Robia SL, Lingrel JB, Bers DM. Isoform‐specificity of the Na/K‐ATPase association and regulation by phospholemman. J Biol Chem. 2009; 284: 26749–26757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Despa S, Bossuyt J, Han F, Ginsburg KS, Jia LG, Kutchai H, Tucker AL, Bers DM. Phospholemman‐phosphorylation mediates the beta‐adrenergic effects on Na/K pump function in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2005; 97: 252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Han F, Tucker AL, Lingrel JB, Despa S, Bers DM. Extracellular potassium dependence of the Na+‐K+‐ATPase in cardiac myocytes: isoform specificity and effect of phospholemman. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009; 297: C699–C705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bell JR, Kennington E, Fuller W, Dighe K, Donoghue P, Clark JE, Jia LG, Tucker AL, Moorman JR, Marber MS, Eaton P, Dunn MJ, Shattock MJ. Characterisation of the phospholemman knockout mouse heart: depressed left ventricular function with increased Na/K ATPase activity. Am J Physiol. 2008; 294: H613–H621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fuller W, Eaton P, Bell JR, Shattock MJ. Ischemia‐induced phosphorylation of phospholemman directly activates rat cardiac Na/K‐ATPase. FASEB J. 2004; 18: 197–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Han F, Bossuyt J, Despa S, Tucker AL, Bers DM. Phospholemman phosphorylation mediates the protein kinase C‐dependent effects on Na+‐K+ pump function in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2006; 99: 1376–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pavlovic D, Fuller W, Shattock MJ. The intracellular region of FXYD1 is sufficient to regulate cardiac Na/K ATPase. FASEB J. 2007; 21: 1539–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Song J, Zhang XQ, Wang J, Cheskis E, Chan TO, Feldman AM, Tucker AL, Cheung JY. Regulation of cardiac myocyte contractility by phospholemman: Na+/Ca2+ exchanger versus Na+‐K+‐ATPase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008; 295: H1615–H1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang J, Gao E, Song J, Zhang XQ, Li J, Koch WJ, Tucker AL, Philipson KD, Chan TO, Feldman AM, Cheung JY. Phospholemman and β‐adrenergic stimulation in the heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010; 298: H807–H815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li C, Grosdidier A, Crambert G, Horisberger JD, Michielin O, Geering K. Structural and functional interaction sites between Na,K‐ATPase and FXYD proteins. J Biol Chem. 2004; 279: 38895–38902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lindzen M, Gottschalk KE, Fuzesi M, Garty H, Karlish SJ. Structural interactions between FXYD proteins and Na+‐K+‐ATPase: α/β/FXYD subunit stoichiometry and cross‐linking. J Biol Chem. 2006; 281: 5947–5955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shinoda T, Ogawa H, Cornelius F, Toyoshima C. Crystal structure of the sodium‐potassium pump at 2.4 A resolution. Nature. 2009; 459: 446–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mahmmoud YA, Vorum H, Cornelius F. Purification of a phospholemman‐like protein from shark rectal glands. J Biol Chem. 2000; 275: 35969–35977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Teriete P, Thai K, Choi J, Marassi FM. Effects of PKA phosphorylation on the conformation of the Na,K‐ATPase regulatory protein FXYD1. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009; 1788: 2462–2470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bossuyt J, Despa S, Martin JL, Bers DM. Phospholemman phosphorylation alters its fluorescence resonance energy transfer with the Na/K‐ATPase pump. J Biol Chem. 2006; 281: 32765–32773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Blanco G, Mercer RW. Isozymes of the Na‐K‐ATPase: heterogeneity in structure, diversity in function. Am J Physiol. 1998; 275: F633–F650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McDonough A, Zhang Y, Shin V, Frank JS. Subcellular distribution of sodium pump isoform subunits in mammalian cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1996; 270: C1221–C1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zahler R, Gilmore‐Hebert M, Baldwin JC, Franco K, Benz EJ Jr. Expression of alpha isoforms of the Na,K‐ATPase in human heart. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993; 1149: 189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bossuyt J, Ai X, Moorman JR, Pogwizd SM, Bers DM. Expression and phosphorylation of the Na‐pump regulatory subunit phospholemman in heart failure. Circ Res. 2005; 97: 558–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Berry RG, Despa S, Fuller W, Bers DM, Shattock MJ. Differential distribution and regulation of mouse cardiac Na+‐K+‐ATPase alpha1 and alpha2 subunits in T‐tubule and surface sarcolemmal membranes. Cardiovasc Res. 2007; 73: 92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sweadner KJ, Herrera V, Amato S, Moellmann A, Gibbons D, Repke K. Immunologic identification of Na+, K+‐ATPase isoforms in myocardium. Circ Res. 1994; 74: 669–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Swift F, Tovsrud N, Enger UH, Sjaastad I, Sejersted OM. The Na+‐K+‐ATPase α2‐isoform regulates cardiac contractility in rat cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2007; 75: 109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dostanic I, Schultz Jel J, Lorenz JN, Lingrel JB. The alpha 1 isoform of Na,K‐ATPase regulates cardiac contractility and functionally interacts and co‐localizes with the Na/Ca exchanger in heart. J Biol Chem. 2004; 279: 54053–54061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bibert S, Roy S, Schaer D, Horisberger JD, Geering K. Phosphorylation of phospholemman (FXYD1) by protein kinases A and C modulates distinct Na,K‐ATPase isozymes. J Biol Chem. 2008; 283: 476–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bers DM. Cardiac excitation‐contraction coupling. Nature. 2002; 415: 198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Grupp I, Im WB, Lee C, Lee SW, Pecker M, Schwartz A. Regulation of sodium pump inhibition to positive inotrophy at low concentrations of ouabain in rat heart muscle. J Physiol (Lond). 1985; 360: 149–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Song J, Zhang XQ, Carl LL, Qureshi A, Rothblum LI, Cheung JY. Overexpression of phospholemman alter contractility and [Ca2+]i transients in adult rat myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002; 283: H576–H583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhang XQ, Qureshi A, Song J, Carl LL, Tian Q, Stahl RC, Carey DJ, Rothblum LI, Cheung JY. Phospholemman modulates Na+/Ca2+ exchange in adult rat cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003; 284: H225–H233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tadros GM, Zhang XQ, Song J, Carl LL, Rothblum LI, Tian Q, Dunn J, Lytton J, Cheung JY. Effects of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger downregulation on contractility and [Ca2+]i transients in adult rat myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002; 283: H1616–H1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zhang XQ, Song J, Rothblum LI, Lun M, Wang X, Ding F, Dunn J, Lytton J, McDermott PJ, Cheung JY. Overexpression of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger alters contractility and SR Ca2+ content in adult rat myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001; 281: H2079–H2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ahlers BA, Zhang XQ, Moorman JR, Rothblum LI, Carl LL, Song J, Wang J, Geddis LM, Tucker AL, Mounsey JP, Cheung JY. Identification of an endogenous inhibitor of the cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, phospholemman. J Biol Chem. 2005; 280: 19875–19882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mirza MA, Zhang XQ, Ahlers BA, Qureshi A, Carl LL, Song J, Tucker AL, Mounsey JP, Moorman JR, Rothblum LI, Zhang TS, Cheung JY. Effects of phospholemman downregulation on contractility and [Ca2+]i transients in adult rat cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004; 286: H1322–H1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wang X, Gao G, Guo K, Yarotskyy V, Huang C, Elmslie KS, Peterson BZ. Phospholemman modulates the gating of cardiac L‐type calcium channels. Biophys J. 2010; 98: 1149–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhang XQ, Ahlers BA, Tucker AL, Song J, Wang J, Moorman JR, Mounsey JP, Carl LL, Rothblum LI, Cheung JY. Phospholemman inhibition of the cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. Role of phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2006; 281: 7784–7792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tucker AL, Song J, Zhang XQ, Wang J, Ahlers BA, Carl LL, Mounsey JP, Moorman JR, Rothblum LI, Cheung JY. Altered contractility and [Ca2+]i homeostasis in phospholemman‐deficient murine myocytes: role of Na+/Ca2+ exchange. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006; 291: H2199–H2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Cheung JY, Rothblum LI, Moorman JR, Tucker AL, Song J, Ahlers BA, Carl LL, Wang J, Zhang XQ. Regulation of cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchanger by phospholemman. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007; 1099: 119–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Nicoll DA, Ottolia M, Lu L, Lu Y, Philipson KD. A new topological model of the cardiac sarcolemmal Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. J Biol Chem. 1999; 274: 910–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Philipson KD, Nicoll DA. Sodium‐calcium exchange: a molecular perspective. Annu Rev Physiol. 2000; 62: 111–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Iwamoto T, Uehara A, Imanaga I, Shigekawa M. The Na+/Ca2+ exchanger NCX1 has oppositely oriented reentrant loop domains that contain conserved aspartic acids whose mutation alters its apparent Ca2+ affinity. J Biol Chem. 2000; 275: 38571–38580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Nicoll DA, Hryshko LV, Matsuoka S, Frank JS, Philipson KD. Mutation of amino acid residues in the putative transmembrane segments of the cardiac sarcolemmal Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. J Biol Chem. 1996; 271: 13385–13391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Levitsky DO, Nicoll DA, Philipson KD. Identification of the high affinity Ca2+‐binding domain of the cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. J Biol Chem. 1994; 269: 22847–22852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Li Z, Nicoll DA, Collins A, Hilgemann D, Filoteo A, Penniston J, Weiss J, Tomich J, Philipson KD. Identification of a peptide inhibitor of the cardiac sarcolemmal Na+‐Ca2+ exchanger. J Biol Chem. 1991; 266: 1014–1020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Maack C, Ganesan A, Sidor A, O’Rourke B. Cardiac sodium‐calcium exchanger is regulated by allosteric calcium and exchanger inhibitory peptide at distinct sites. Circ Res. 2005; 96: 91–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wang J, Zhang XQ, Ahlers BA, Carl LL, Song J, Rothblum LI, Stahl RC, Carey DJ, Cheung JY. Cytoplasmic tail of phospholemman interacts with the intracellular loop of the cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. J Biol Chem. 2006; 281: 32004–32014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Reuter H. The dependence of slow inward current in Purkinje fibres on the extracellular calcium‐concentration. J Physiol. 1967; 192: 479–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zhang XQ, Moore RL, Tillotson DL, Cheung JY. Calcium currents in postinfarction rat cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1995; 269: C1464–C1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lemke T, Welling A, Christel CJ, Blaich A, Bernhard D, Lenhardt P, Hofmann F, Moosmang S. Unchanged β‐adrenergic stimulation of cardiac L‐type calcium channels in Cav1.2 phosphorylation site S1928A mutant mice. J Biol Chem. 2008; 283: 34738–34744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Despa S, Tucker AL, Bers DM. PLM‐mediated activation of Na/K‐ATPase limits [Na]i and inotropic state during β‐adrenergic stimulation in mouse ventricular myocytes. Circulation. 2008; 117: 1849–1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Jia LG, Donnet C, Bogaev RC, Blatt RJ, McKinney CE, Day KH, Berr SS, Jones LR, Moorman JR, Sweadner KJ, Tucker AL. Hypertrophy, increased ejection fraction, and reduced Na‐K‐ATPase activity in phospholemman‐deficient mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005; 288: H1982–H1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Srivastava S, Cala SE, Coetzee WA, Artman M. Phospholemman expression is high in the newborn rabbit heart and declines with postnatal maturation. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2007; 355: 338–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Reis J, Zhang L, Cala S, Jew KN, Mace LC, Chung L, Moore RL, Ng YC. Expression of phospholemman and its association with Na+‐K+‐ATPase in skeletal muscle: effects of aging and exercise training. J Appl Physiol. 2005; 99: 1508–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Rasmussen MK, Kristensen M, Juel C. Exercise‐induced regulation of phospholemman (FXYD1) in rat skeletal muscle: implications for Na+‐K+‐ATPase activity. Acta Physiol (Oxford, England). 2008; 194: 67–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Sehl PD, Tai JT, Hillan KJ, Brown LA, Goddard A, Yang R, Jin H, Lowe DG. Application of cDNA microarrays in determining molecular phenotype in cardiac growth, development, and response to injury. Circulation. 2000; 101: 1990–1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Dixon I, Hata T, Dhalla N. Sarcolemmal Na+‐K+‐ATPase activity in congestive heart failure due to myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1992; 262: C664–C671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Dixon I, Hata T, Dhalla N. Sarcolemmal calcium transport in congestive heart failure due to myocardial infarction in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1992; 262: H1387–H1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Zhang XQ, Tillotson DL, Moore RL, Zelis R, Cheung JY. Na+/Ca2+ exchange currents and SR Ca2+ contents in postinfarction myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1996; 271: C1800–C1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Madhani M, Hall AR, Cuello F, Charles RL, Burgoyne JR, Fuller W, Hobbs AJ, Shattock MJ, Eaton P. Phospholemman Ser‐69 phosphorylation contributes to sildenafil‐induced cardioprotection against reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. In press, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Pogwizd SM, Schlotthauer K, Li L, Yuan W, Bers DM. Arrhythmogenesis and contractile dysfunction in heart failure: roles of sodium‐calcium exchange, inward rectifier potassium current, and residual β‐adrenergic responsiveness. Circ Res. 2001; 88: 1159–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Parrillo JE. Pathogenetic mechanisms of septic shock. New Eng J Med. 1993; 328: 1471–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Grocott‐Mason RM, Shah AM. Cardiac dysfunction in sepsis: new theories and clinical implications. Intensive Care Med. 1998; 24: 286–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Figtree GA, Liu CC, Bibert S, Hamilton EJ, Garcia A, White CN, Chia KK, Cornelius F, Geering K, Rasmussen HH. Reversible oxidative modification: a key mechanism of Na+‐K+ pump regulation. Circ Res. 2009; 105: 185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. William M, Vien J, Hamilton E, Garcia A, Bundgaard H, Clarke RJ, Rasmussen HH. The nitric oxide donor sodium nitroprusside stimulates the Na+‐K+ pump in isolated rabbit cardiac myocytes. J Physiol. 2005; 565: 815–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Hemby SE, Ginsberg SD, Brunk B, Arnold SE, Trojanowski JQ, Eberwine JH. Gene expression profile for schizophrenia: discrete neuron transcription patterns in the entorhinal cortex. Arch Gen Psych. 2002; 59: 631–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Naidu S. Rett syndrome: a disorder affecting early brain growth. Ann Neurol. 1997; 42: 3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Deng V, Matagne V, Banine F, Frerking M, Ohliger P, Budden S, Pevsner J, Dissen GA, Sherman LS, Ojeda SR. FXYD1 is an MeCP2 target gene overexpressed in the brains of Rett syndrome patients and Mecp2‐null mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2007; 16: 640–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Jordan C, Li HH, Kwan HC, Francke U. Cerebellar gene expression profiles of mouse models for Rett syndrome reveal novel MeCP2 targets. BMC Med. Genet. 2007; 8: 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Meij IC, Koenderink JB, Van Bokhoven H, Assink KF, Groenestege WT, De Pont JJ, Bindels RJ, Monnens LA, Van Den Heuvel LP, Knoers NV. Dominant isolated renal magnesium loss is caused by misrouting of the Na+‐K+‐ATPase γ‐subunit. Nat Genet. 2000; 26: 265–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Yamamoto H, Okumura K, Toshima S, Mukaisho K, Sugihara H, Hattori T, Kato M, Asano S. FXYD3 protein involved in tumor cell proliferation is overproduced in human breast cancer tissues. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009; 32: 1148–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Nam JS, Hirohashi S, Wakefield LM. Dysadherin: a new player in cancer progression. Cancer Lett. 2007; 255: 161–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]