Abstract

Detailed phylogenetic analyses were performed to characterize an HIV-1 outbreak among injection drug users (IDUs) in Stockholm, Sweden, in 2006. This study investigated the source and dynamics of HIV-1 spread during the outbreak as well as associated demographic and clinical factors. Seventy Swedish IDUs diagnosed during 2004 to 2007 were studied. Demographic, clinical, and laboratory data were collected, and the V3 region of the HIV-1 envelope gene was sequenced to allow detailed phylogenetic analyses. The results showed that the Stockholm outbreak was caused by a CRF01_AE variant imported from Helsinki, Finland, around 2003, which was quiescent until the outbreak started in 2006. Local Swedish subtype B variants continued to spread at a lower rate. The number of new CRF01_AE cases over a rooted phylogenetic tree accurately reflected the transmission dynamics and showed a temporary increase, by a factor of 12, in HIV incidence during the outbreak. Virus levels were similar in CRF01_AE and subtype B infections, arguing against differences in contagiousness. Similarly, there were no major differences in other baseline characteristics. Instead, the outbreak in Stockholm (and Helsinki) was best explained by an introduction of HIV into a standing network of previously uninfected IDUs. The combination of phylogenetics and epidemiological data creates a powerful tool for investigating outbreaks of HIV and other infectious diseases that could improve surveillance and prevention.

In the summer of 2006, a sharp increase of newly diagnosed cases of HIV type 1 (HIV-1) infections among injection drug users (IDUs) was reported in Stockholm, Sweden. The outbreak continued until the end of 2007, resulting in more than 70 newly diagnosed cases. The first HIV-1 cases among IDUs in Sweden were diagnosed when HIV antibody testing became available in 1984 to 1985, and since the early 1990s, the number of new cases in the Stockholm area has been relatively stable, with around 20 cases per year. Cumulatively, there were 885 HIV-1 diagnoses among IDUs between 1984 and 2009, while the number of IDUs in Stockholm has been estimated to be around 9,000 (19), or possibly lower (3). The true HIV-1 prevalence among IDUs has been difficult to assess, but the national prevalence in prisons was 5.5% in 2005 (7). Differentiated risk behavior (i.e., serosorting) depending on HIV or hepatitis B and C status has been observed (25), and one study identified needle-sharing behavior as the only factor associated with HIV status (26).

HIV-1 subtype B dominated the early epidemic in Western Europe (22, 27) and also in Sweden, where subtype B constituted 85% of HIV-1 infections among examined IDUs in 2001 and 2002 (33). A majority of these IDUs were infected in Sweden, but a few non-subtype B infections were imported from HIV-1 outbreaks among IDUs in Finland (1 to 3 cases), Latvia (1 or 2 cases), and Estonia (1 case) (33). Helsinki, the capital of Finland, experienced an HIV-1 outbreak among IDUs that started in 1998. The outbreak involved infections with the circulating recombinant form 01_AE (CRF01_AE) (21), which is prevalent in Southeast Asia. Kivela et al. reported that IDUs in Helsinki infected with the Finnish CRF01_AE variant had higher plasma viral loads than did IDUs in Amsterdam, Netherlands, who were infected with subtype B, and they suggested that this might have contributed to the rapid spread in Helsinki (14).

Viruses which evolve at a measurable rate, like HIV, present unique opportunities to use molecular epidemiology to investigate the rate of spread, introduction dates, time between infections, and detailed phylodynamics (11, 23, 28, 30). Thus, molecular epidemiology using HIV sequence data can provide information that is not readily accessible from pure epidemiological studies. The aim of this study was to investigate the dynamics of HIV-1 spread in the IDU outbreak in Stockholm by using molecular epidemiology together with observational epidemiological data. In addition, we investigated if the outbreak could be due in part to the introduction of a new, more-transmissible HIV-1 variant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

The inclusion criteria were (i) newly diagnosed HIV-1 infection during 2004 to 2007, (ii) residency in the Stockholm area, and (iii) intravenous drug use as the likely route of infection. A total of 74 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the study. From patient records, we obtained information about the year of diagnosis, age, gender, reporting clinic, main drug used, living situation, CD4+ lymphocyte (CD4) counts, and plasma HIV-1 RNA levels. Blood samples (EDTA-treated plasma) were collected from each individual. The method for sequencing the C2V3C3 (V3) region of the HIV-1 env gene has been described elsewhere (33, 39).

We included previously unpublished sequences from 81 Finnish IDUs diagnosed in Helsinki during 1998 to 2007. The sociodemographic characteristics of the early Finnish epidemic (1998 to 2003) have been described in detail elsewhere (13). The Finnish samples represent the National Microbe Strain Collection, which is based on the Communicable Diseases Act and the Communicable Diseases Decree. The study was approved by the regional ethics committee in Stockholm (protocols 2005/944-31/1, 2008/662-32, and 2010/1385-32).

CD4 counts and plasma HIV-1 RNA levels.

CD4 counts were enumerated by flow cytometry in accordance with recommendations by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Plasma HIV-1 RNA levels were measured using the Cobas Ampliprep/Cobas Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor assay, version 1.5 (Roche Molecular Diagnostic Systems, Mannheim, Germany), or, after July 2007, the Cobas Ampliprep/Cobas TaqMan HIV-1 assay, version 1 (Roche Molecular Diagnostic Systems, Mannheim, Germany). It has been reported that the TaqMan assay sometimes underquantifies the RNA load, but no significant subtype-specific associations have been identified for subtype B or CRF01_AE (9, 16). An extensive comparison between the two assays has been done for the Stockholm HIV cohort at Huddinge University Hospital. Only 2% of samples were underquantified with the TaqMan assay, with no subtype-specific associations (A Sönnerborg, personal communication, December 2009). We estimated the set-point CD4 counts and plasma HIV-1 RNA levels by calculating the means for up to three consecutive determinations, excluding determinations performed after the start of antiretroviral therapy. The first available RNA determination was excluded to avoid the possible impact of high virus levels during primary infection.

Phylogenetic and phylodynamic inferences.

Subtype assignments of the sequences were done using the subtype reference data set available at the Los Alamos HIV database. The phylogenetic signals in the Swedish and Finnish sequences were estimated using likelihood mapping, available in TreePuzzle (35). We compared the Swedish and Finnish V3 sequences to international sequences available in the Los Alamos HIV sequence database, covering the same genetic region for each subtype. Nucleotide alignments were made using MAFFT (12), followed by manual editing in Se-Al (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/seal/), and uncertain regions were removed. Neighbor-joining (BioNJ) trees were inferred in PAUP* (37), using substitution model F84. Database sequences closely related to the Swedish and Finnish sequences were saved, including 92 sequences from Swedish IDUs diagnosed prior to the 2006 outbreak, i.e., during 1987 to 2004 (GenBank accession numbers EU010269 to EU101360) (33). Subsequently, a maximum likelihood (ML) tree was inferred for each subtype, using PhyML v3.0 (10), with a GTR substitution model with invariable sites and gamma-distributed rates among sites. Phylogenetic uncertainty was assessed using a nonparametric bootstrap and the approximate likelihood ratio test (aLRT) (1). Mixing and clustering of the demographic and clinical data over the ML trees were estimated using MacClade v4.06 (http://macclade.org), with a modified version of the Slatkin-Maddison test (34), where significance was assessed by computing the 95% confidence interval for character changes in 10,000 random trees. Phylodynamic analyses were performed by analyzing node heights, tip lengths, and cumulative cases from the inferred ML trees together with sampling times, using computational functions in R (31).

We further analyzed the temporal and phylogenetic dynamics of the Swedish and Finnish sequences involved in the outbreaks by using BEAST v1.4.8 (5). We used the SRD06 model (32), along with two different population growth models: nonparametric Bayesian skyline analysis with four or five groups and the logistic growth model. Evolutionary rates were inferred under both a strict and a relaxed clock (4), and the suitable clock was determined by calculating the Bayes factor (BF) (24, 36) and by inspecting marginal posterior distributions of the parameters of interest. The Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chain lengths and appropriate burn-in were chosen so that the effective sample sizes exceeded 300, and convergence was visually assessed in the program Tracer 1.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/). For the tight Swedish CRF01_AE cluster, we used a strong molecular clock rate prior derived from the evolutionary rate of the Finnish CRF01_AE sequences. Phylogeographic analysis was performed for the Swedish and Finnish CRF01_AE sequences by using BEAST v1.5.3 according to a previously described method (18).

Statistical analyses.

Nonparametric statistical analyses (chi-square test, Fisher's exact test, and Mann-Whitney U test) were used, as appropriate, to compare baseline characteristics between CRF01_AE and subtype B infections. Regression analyses were done using OLS and loess functions in R (31) and skyline and logistic functions in BEAST (5).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The previously unpublished Swedish and Finnish V3 sequences have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers GU222921 to GU223066.

RESULTS

Our study included all 74 HIV-1 patients in Sweden who fulfilled the inclusion criteria. V3 sequencing from plasma was unsuccessful for eight samples, but four of these patients were subtyped using pol sequences and were included in the demographic and clinical analyses. Forty-six of the 70 study subjects were infected with CRF01_AE variants that were closely related to viruses from IDUs in Helsinki, Finland, while 23 study subjects had subtype B infections. One patient had a subtype A infection and was excluded from further analyses.

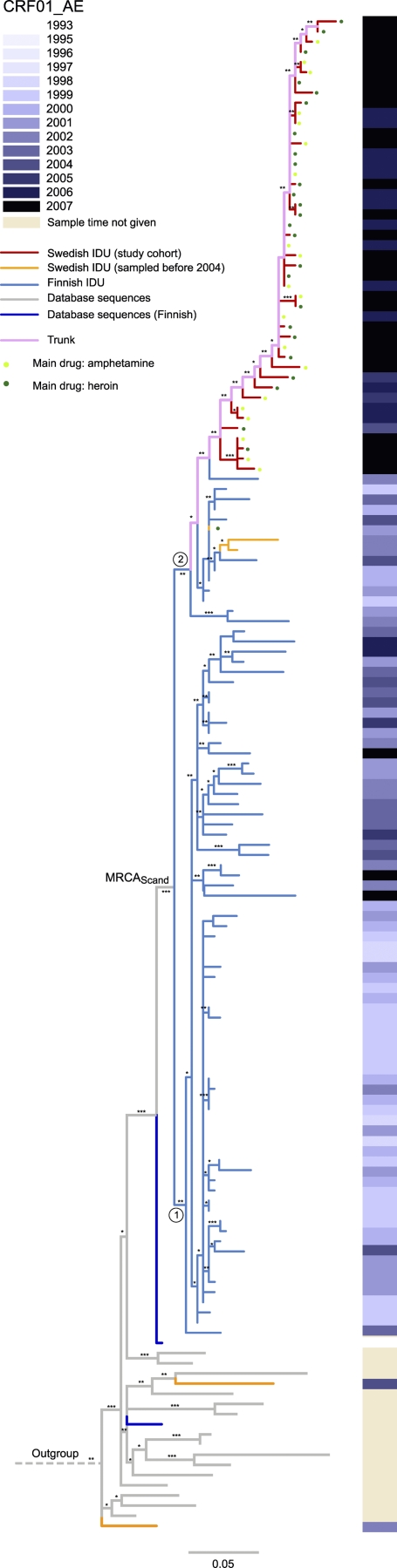

Multiple introductions of CRF01_AE to Stockholm from Helsinki, with one successful founder.

Almost all of the Swedish and Finnish CRF01_AE sequences formed a monophyletic cluster (98%; aLRT) (Fig. 1; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Furthermore, the Swedish sequences from 2004 to 2007 formed a monophyletic cluster within the Finnish sequences, whereas three Swedish CRF01_AE sequences from 2002 clustered with the Finnish sequences. Thus, at least one HIV-1 introduction from Helsinki occurred before 2003, but it caused no or very limited local spread in Stockholm. A separate introduction involved the founder of the HIV-1 outbreak among IDUs in Stockholm in 2006. This pattern was robustly recovered with both phylogenetic methods used, i.e., ML and Bayesian inference.

FIG. 1.

Maximum likelihood tree of CRF01_AE V3 sequences from Stockholm and Helsinki and of closely related database sequences. The color of each branch represents the country of sampling for Swedish and Finnish sequences, while sequences from other countries are shown in gray. The filled circles next to the tips indicate main drug use. The sampling times for Swedish and Finnish sequences are shown on the right, in gray scale. The trunk, colored pink, describes the relative movement of the epidemic of lineage 2, and the MRCA for the Finnish-Swedish cluster is annotated MRCAScand. The scale at the bottom indicates the number of nucleotide substitutions per site, according to a GTR+I+G model. The tree was rooted using CRF01_AE African sequences 01CD107 (GenBank accession no. AY675602) and 01CM2534 (GenBank accession no. AY180116). Robustness aLRT values of >70%, >80%, and >90% are marked with 1, 2, and 3 asterisks, respectively.

The dynamics of the local epidemics of CRF01_AE in Stockholm and Helsinki were investigated using the genetic distances of the ML tree in Fig. 1. The tips are the outermost branches (leaves) in the tree, and their length is the genetic distance from the start of the branch at the internal node to the end of the branch. A majority of the tips were shorter than 0.005 substitution site−1 year−1 (Fig. 2A). This indicates that the time from infection to diagnosis was short for most cases (17, 23).

FIG. 2.

Detailed analysis of the CRF01_AE maximum likelihood tree. (A) Tip length distributions for the Swedish and Finnish sequences, shown at intervals of 0.01 substitution site−1. (B) Number of tips at a certain height from MRCAScand, measured to the internal node of the tip. Furthermore, the tip length distribution was resolved according to the height from MRCAScand to the internal node of each tip (the MRCA of each tip edge). (C) Loess regression for each geographical region. (D) Tip length distribution, resolved according to sampling dates of the taxa, with loess regressions.

The height of the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) for each tip was defined as the genetic distance from the base of the Finnish outbreak (MRCAScand) to the internal node of each tip. Thus, the MRCA height is a relative genetic measure of the genetic distance from the beginning of the Scandinavian outbreak to each branching event resulting in a tip, which is an approximation of a transmission event (but see reference 17). When the MRCA height distributions for the Finnish and Swedish outbreaks were superposed, it was clear that the majority of the Finnish MRCA heights were shorter than the Swedish MRCA heights (P < 0.001; Wilcoxon rank sum test) (Fig. 2B), which indicates that the Helsinki epidemic had culminated before the outbreak in Stockholm started.

We also used genetic measures to investigate changes in the time from infection to diagnosis. Thus, the tip length distribution was resolved according to MRCA height (Fig. 2C) and date of sampling (Fig. 2D). It was interesting that the first Swedish cases had long tips, which indicates that these cases remained undiscovered for some time before the outbreak started. However, during the Swedish outbreak in 2006 and 2007 (at a MRCA height of approximately 0.08 substitution site−1), the majority of the tip lengths were very short (Fig. 2C and D), indicating diagnosis soon after infection. For the Finnish epidemic, the tip lengths increased with time and increasing MRCA heights (Fig. 2C and D). This suggests that the time from infection to diagnosis increased over time or that transmissions occurred from undiagnosed or unsampled cases.

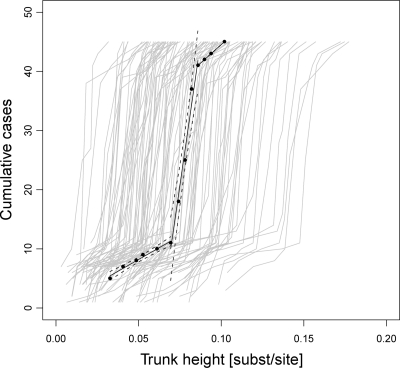

The Finnish CRF01_AE sequences were divided into lineage 1 and lineage 2, with the latter introduced into Sweden (Fig. 1). The trunk of lineage 2, shown in pink in Fig. 1, indicates the movement of the main epidemic through time, as measured by substitutions per site as a proxy for calendar time. Figure 3 shows the cumulative history of Swedish cases resolved according to trunk height, where trunk height is defined as the genetic distance from MRCAScand to each branching event on the trunk. When the slope (number of cases per trunk height) was normalized to 1 according to the first phase (i.e., the preoutbreak phase) of the Swedish CRF01_AE epidemic, it was evident that the case incidence temporarily increased by a factor of 12 (5 to 95% quantile range, 8.3 to 41) during the peak of the outbreak, indicating a change from slow to fast HIV spread. In the third phase (i.e., postoutbreak phase), the incidence rate decreased to a normalized slope of 1.6. All three regressions were clearly separated, with a high confidence level (R2 > 0.97 and P < 0.01; F test). Phylogenetic uncertainty was accounted for by inferring 100 ML bootstrap replicate trees (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The first phase had a normalized median slope of 1.3 (5 to 95% quantile range, 0.61 to 3.4) (normalized with the first-phase ML slope) (see Fig. S2A). The increase in case incidence during the outbreak was also significant for the bootstrap replicates (P < 0.001; Wilcoxon rank sum test) (see Fig. S2B). Slope 3, representing the incidence rate shortly after the outbreak, returned to lower values in both the ML tree and the bootstrap replicate trees, at 1.6 and 2.5 (5 to 95% quantile range, 1.2 to 5.9), respectively (see Fig. S2C). The initial and final phases of the CRF01_AE incidence rate were similar to the case incidence rates measured for subtype B transmission clusters I and II, within factors of 1.43 and 1.57, respectively (data not shown). The trunk definition is valid, as the massive expansion of the number of Swedish cases during a short time interval around a trunk height of 0.08 substitution site−1 (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material) agrees well with what is seen in Fig. 2B.

FIG. 3.

Cumulative history of Swedish CRF01_AE cases. Black points show the height of the trunk from MRCAScand (see Fig. 1). The black lines are ordinary least-squares estimates of the incidence rates inferred from the ML tree in Fig. 1, with the 95% regression confidence limits shown with dashed lines. The slope of phase 1 (preoutbreak) was 160 cases/trunk height (R2 = 0.97; P < 0.01; F test), phase 2 (the outbreak) had a slope of 1,930 cases/trunk height (R2 = 0.97; P < 0.01; F test), and phase 3 (postoutbreak) had a slope of 251 cases/trunk height (R2 = 1; P < 0.01; F test). The gray lines represent each of 100 bootstrap replicate trees. The three inferred bootstrap slopes were also well separated (P < 0.001; Wilcoxon rank sum test) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The initial spread rate of CRF01_AE in the ML tree (preoutbreak) was used to normalize the slopes in the figure to allow for relative rate estimation. The outbreak accumulated 12 times more infections per trunk height than those during the preoutbreak phase.

As expected, the phylogenetic signal was low for the Swedish CRF01_AE sequences (∼30% of the quartets were star-like), but for the combined Swedish and Finnish data set, the phylogenetic signal was higher (17% star-like quartets). The low aLRT values for many branches associated with the outbreak suggest that the exact relationships of viruses sampled during the outbreak should be interpreted with caution. However, the overall structure of the tree was more robust. The subtype B sequences had a higher phylogenetic signal, with 12% of the quartets showing a star-like signal. This agrees well with the fact that subtype B has spread more slowly than CRF01, thus accumulating more mutations between transmissions (23).

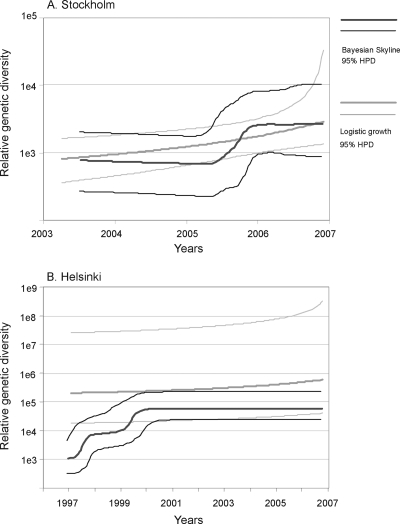

Dating CRF01_AE introductions to Stockholm.

The CRF01_AE epidemics among IDUs in both Stockholm and Helsinki involved slow as well as fast spread, which complicates dating because the molecular clock is inversely correlated to the rate of spread (23). However, for both the Swedish and Finnish data sets, the epidemic dynamics shown by the above ML analyses were also captured by Bayesian analyses, using a relaxed clock and two different growth models (the nonparametric skyline growth model and the logistic growth model). This allowed us to infer when epidemic events occurred (Fig. 4) (6). We estimated that the local CRF01_AE spread leading up to the outbreak in Stockholm started at or before February 2003 (95% highest posterior distribution [HPD], July 2001 to July 2004), using the MRCA of all Stockholm taxa in the present study and the skyline model. The date estimations derived from the logistic growth model were essentially the same (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 4A, the relative genetic diversity (RGD) in the skyline curve started to grow in the second half of 2006, which is supported by the logistic growth parameter (logistic t50) (mean = December 2005; median = July 2006; HPD = December 2002 to October 2007), representing the time in the past when the viral population had half of the final population size. This coincides with the increase in newly diagnosed HIV-1 cases among IDUs, but it is important that the RGD does not directly correspond to the number of infected individuals (2, 38). According to our analyses using the skyline model, the local Finnish epidemic started with a sharp increase of RGD in 1998, followed by a short plateau and another increase in 2001 (Fig. 4B). The MRCA of the Finnish sequences was estimated to occur in November 1994 (HPD, August 1991 to January 1998). However, it should be stressed that the logistic growth model, which by definition shows a continuous increase in RGD, did not show an inferior fit to the data than the Bayesian skyline model (2·ln BF = 1.5 [insignificant]).

FIG. 4.

Viral population growth histories of the local CRF01_AE epidemics in Stockholm (A) and Helsinki (B). The relative genetic diversity over time inferred with the Bayesian skyline model is indicated in dark gray, and that with the logistic growth model is indicated in light gray.

The migration between Finland and Sweden was also investigated using the logistic model. The analysis indicated that there might have been multiple introductions from Finland into Sweden, but there was also an indication (posterior probability = 0.64) of migration from Stockholm to Helsinki (data not shown). Thus, the base of lineage 2 in Fig. 1 could be regarded as a single IDU community based in two geographical locations. Epidemiological information has suggested that the virus causing the IDU outbreak in Helsinki was imported from Thailand, but interestingly, we found that the database sequence most closely related to the Finnish CRF01_AE sequences was obtained from a heterosexually infected Finnish individual diagnosed in 1993 (GenBank accession no. AF219378) (20). This suggests that the CRF01_AE variant that caused the massive outbreak among IDUs in Helsinki around the year 2000 may already have been introduced into Finland through heterosexual transmission in the early 1990s (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

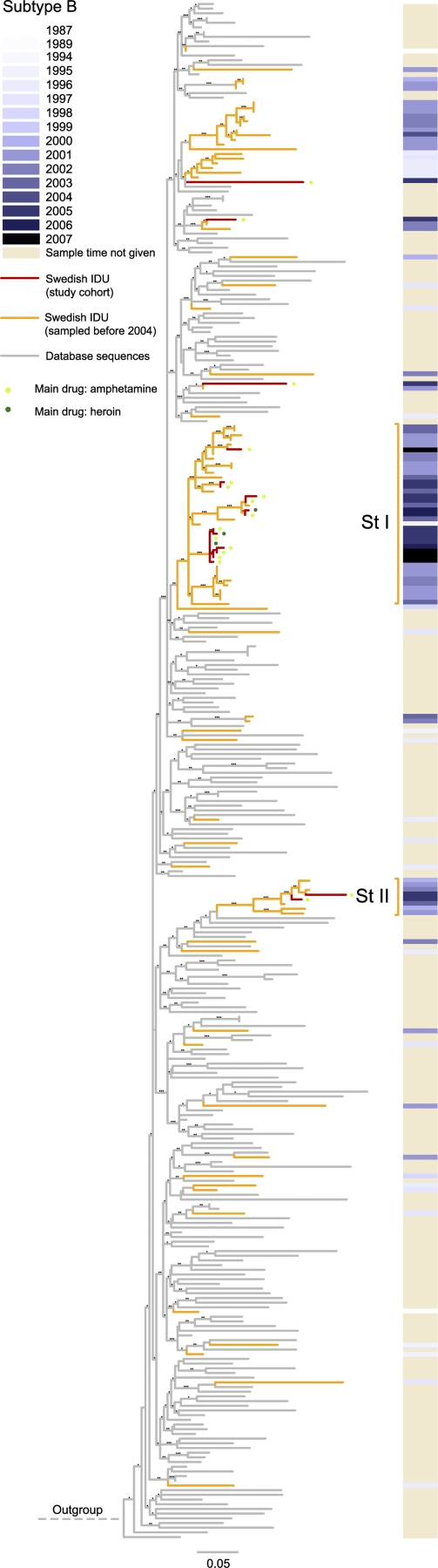

Continued spread of subtype B among IDUs in Stockholm.

Twenty-three of the study subjects were infected by subtype B strains, and Fig. 5 shows that all except one clustered with earlier identified local transmission chains (33). Two of these clusters were previously named Stockholm clusters I and II. Their MRCAs were dated to the mid-1990s, and our new data show that these variants have continued to spread among IDUs in Stockholm. Eight patients diagnosed in 2005 and 2007 appear to have been involved in a small outbreak within cluster I, as the corresponding taxa display short internal and external branches; six of these IDUs used amphetamine as their main drug (Fig. 5). However, half of the subtype B-infected IDUs appear to have been involved in slower spread.

FIG. 5.

Maximum likelihood tree of subtype B V3 sequences from Stockholm and of closely related database sequences. Red branches represent sequences in the present study cohort, while orange branches represent sequences from the work of Skar et al. (33); other sequences are shown in gray. The local transmission clusters are annotated in the same way as in reference 33. St I and II refer to Stockholm clusters 1 and 2, respectively. The sampling times are shown on the right, in gray scale, for Swedish sequences. The tree was rooted using subtype D sequence ELI (GenBank accession no. A07108). Robustness aLRT values of >70%, >80%, and >90% are marked with 1, 2, and 3 asterisks, respectively.

Demographic and clinical characteristics and distribution.

The demographic characteristics of patients infected with subtype B or CRF01_AE were compared to investigate if the two variants had spread in different IDU subgroups in Stockholm (Table 1). Sex, reporting body, or housing situation did not differ between individuals infected with CRF01_AE or subtype B. However, the year for diagnosis was strongly correlated with the viral subtype (P < 0.001; Mann-Whitney U test), and patients infected with subtype B were somewhat older (median, 45 years) than patients infected with CRF01_AE (median, 40 years) (same-age P = 0.017; Mann-Whitney U test). A majority of the heroin users had CRF01_AE infections (83%), while amphetamine users had similar proportions of CRF01_AE (52%) and subtype B (48%) infections (P = 0.0022; Fisher's exact test). The proportion of heroin users increased nonsignificantly over time, from 19% in 2005 to 51% in 2007 (P = 0.13; Mann-Whitney U test).

TABLE 1.

Patient baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | Value |

P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Subtype B infections | CRF01_AE infections | ||

| No. (%) of patients | 69 | 23 (33) | 46 (66) | |

| Sex (no. [%] of patients) | 0.38 | |||

| Female | 17 | 4 (24) | 13 (76) | |

| Male | 52 | 19 (36) | 33 (62) | |

| Age (no. [%] of patients) | 0.017 | |||

| 18-30 | 10 (14) | 2 | 8 | |

| 31-40 | 21 (30) | 5 | 16 | |

| 41-50 | 28 (41) | 10 | 18 | |

| 51-60 | 9 (13) | 5 | 4 | |

| 61-70 | 1 (1) | 1 | 0 | |

| Year of diagnosis (no. [%] of patients) | <0.001 | |||

| 2004 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 | |

| 2005 | 16 (23) | 14 | 2 | |

| 2006 | 17 (25) | 3 | 14 | |

| 2007 | 35 (51) | 6 | 29 | |

| Reporting body (no. [%] of patients) | 0.46 | |||

| Institutional care | 12 (17) | 4 | 8 | |

| Addiction-related care | 27 (39) | 7 | 20 | |

| Correctional systems | 12 (17) | 6 | 6 | |

| Noninstitutional care | 12 (17) | 2 | 10 | |

| Outreach programs | 6 (9) | 3 | 3 | |

| Main drug (no. [%] of patients) | 0.0022 | |||

| Heroin | 30 (43)a | 4 | 26 | |

| Amphetamines | 39 (57) | 19 | 20 | |

| Living situation (no. [%] of patients) | 0.78 | |||

| Homelessb | 49 (71) | 17 | 32 | |

| Stable housingc | 20 (29) | 6 | 14 | |

| CD4 count (cells/μl) (median [range]) | 506 (40, 1,200) | 425 (40, 1,000) | 550 (200, 1,200) | 0.22 |

| Viral load (log 10 copies/ml) (median [range]) | 4.8 (2.3, 6.0) | 4.9 (3.3, 6.0) | 4.7 (2.3, 6.0) | >0.2 |

The heroin group includes two buprenorphine users.

Homelessness was defined as sleeping in shelters, cars, or public parks, squatting places, staying with friends, or other nondwelling circumstances.

Stable housing was defined as residing in an apartment, trial apartment, or temporary accommodation during the last 3 months.

We also estimated the mixing of the demographic parameters over the phylogenetic tree within the Swedish CRF01_AE cluster (Fig. 1, lineage 2) and the subtype B Stockholm cluster I (Fig. 5, cluster St I [red branches]). There was no significant clustering of any demographic parameter for either CRF01_AE or the small subtype B transmission chain.

IDUs in the Finnish CRF01_AE outbreak had been reported to have higher plasma viral levels than Dutch IDUs infected with subtype B viruses (14). However, in our study, there was no significant difference in plasma HIV-1 RNA levels between Swedish IDUs infected with subtype B and those infected with CRF01_AE (P > 0.2 [Mann-Whitney U test]; false discovery rate [q], <0.077), nor were there significantly different CD4 counts (P = 0.218; Mann-Whitney U test) (Table 1). We did not observe any significant clustering according to plasma HIV-1 RNA levels or CD4 counts in the phylogenetic trees.

DISCUSSION

As detailed in our analyses of the CRF01_AE outbreaks in Stockholm and Helsinki, the methods used in our study can give information about a number of important aspects of HIV-1 spread, such as the number of circulating viral variants, the dynamics of spread in time and space, the time from infection to diagnosis, and possible subdivided local networks. The CRF01_AE outbreak in Stockholm was identified in 2006, but the founder CRF01_AE variant had been present in Stockholm at least since 2003. In support of this, the first Swedish taxa had longer tips than those obtained during the peak of the outbreak. Thus, short tips in the phylogenetic tree indicate a short time between infection and diagnosis and longer tips indicate a longer time from infection to diagnosis, but this could also be due to missing taxa, i.e., undiagnosed or unsampled cases. In addition, transmitted viruses might already contain diversity, and thus viruses within one patient might have diverged before the infection took place (17). We quantified that there was a 12-fold increase in case incidence during the peak of the CRF01_AE outbreak. Furthermore, we found that the incidence of CRF01_AE infections before and perhaps also after the outbreak was similar to the incidence of subtype B infections. The phylogenetic error was estimated using nonparametric bootstrap analysis, i.e., bootstrapping the input sequence data and inferring a new ML tree for each such data set. Because this will lower the phylogenetic signal for each replicate, especially for short branches (in outbreaks) and for HIV, where a large proportion of sites are homoplastic, this is likely an overly conservative measure of uncertainty of the phylodynamics. Thus, the uncertainties in the slope estimates could be reduced if a less conservative method, such as the Bayesian strategy, was used. However, we feel that the nature of these dynamics, which involved both slow and extremely fast spread, makes ML a preferred method over Bayesian methods, since Bayesian coalescent methods make additional assumptions (such as a clock parameter that is relaxed but still not completely free to vary over the tree) that potentially could bias the results. In addition, we supported the results from the maximum likelihood analyses with the more-complex Bayesian analyses inferred separately. The CRF01_AE outbreak in Stockholm appears to have ended, since the number of newly diagnosed cases returned to around 20 in 2008, and the phylogenetically estimated case incidence after the outbreak was within a factor of 1.4 of the rate at which subtype B has been spreading among IDUs in Stockholm. This indicates that the CRF01_AE variant could continue to spread among IDUs in Stockholm together with the subtype B variants that have been present for over a decade. It is also likely that some IDUs in Stockholm who were infected with CRF01_AE virus during the outbreak are still not diagnosed. Thus, it is possible that we will observe a similar increase in tip lengths for Stockholm to that we have documented for Helsinki. Interestingly, recent findings by Kivela et al. support the finding that the time to diagnosis has increased over time in the Finnish IDU epidemic, since 6% of patients were defined to have late diagnoses in 1998 to 2001, compared to 37% in 2002 to 2005 (15).

We found that there were several migrations of CRF01_AE from Helsinki to Stockholm, suggesting the occurrence of IDU networks that span the Baltic Sea. However, only one migrating variant appeared to have founded the outbreak in Stockholm. It is interesting to discuss if there was a specific reason why this Finnish variant of CRF01_AE founded the outbreak instead of the subtype B variant that had been present in Stockholm since the 1990s. However, our results argue against a biological explanation, i.e., transmissibility (8, 29), because there were no differences in virus levels and CD4 counts between patients infected with CRF01_AE and those infected with subtype B. Furthermore, we saw no significant clustering of clinical or behavioral parameters over the subtype B and CRF01_AE trees. These findings are interesting, since it has been reported that the CRF01_AE variant in Helsinki is associated with higher viral loads than those in IDUs from Amsterdam infected with subtype B (14). However, it should be mentioned that our study was not powered to detect minor differences in virus levels, but we feel that it is a strength that we investigated individuals who lived in the same city, belonged to the same transmission group, and were sampled during the same period.

The rapid spread of the CRF01_AE variant suggests that it entered a standing social network of IDUs with risky needle-sharing (or sexual) behavior. We identified some sociodemographic factors that differed significantly between individuals infected with subtype B and CRF01_AE. In particular, we found that almost all heroin users were infected with CRF01_AE, whereas amphetamine users had both subtype B and CRF01_AE infections. Thus, the CRF01_AE variant appears to have entered a network of heroin users who previously had not experienced subtype B infections. However, our data indicate that there has been communication between IDUs using heroin and amphetamine, since they did not show distinct phylogenetic clustering. Since the turn of the century, amphetamine abuse has increased in Stockholm, and it is the major drug in Helsinki (13). Thus, the introduction of CRF01_AE in Stockholm seems likely to have involved amphetamine users. However, it should be noted that a few of the sequences at the base of the Swedish CRF01_AE cluster were obtained from heroin users.

There are probably several reasons for the rapid decrease in HIV diagnoses among IDUs in Stockholm. The fact that the outbreak was rapidly discovered led to preventive efforts from society and probably also an increased awareness and reduction in risky behavior in the IDU community. However, there have been no needle exchange programs in Stockholm. Thus, IDUs in Stockholm have had to resort to other ways of avoiding HIV-1 infection, such as serosorting (25). However, serosorting has a limited effect if HIV unknowingly enters a standing network that practices risky needle-sharing or sexual behavior. Thus, effective prevention depends crucially on rapid discovery of and response to outbreaks. We feel that continuous and rapid molecular epidemiology of HIV-1 in newly diagnosed patients can greatly aid in surveillance and prevention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kajsa Aperia and Afsaneh Heidarian for excellent technical assistance and Inger Zedenius and Malin Arneborn for valuable contributions.

This work was supported by the National Board of Health and Welfare, the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (grant SWE-2006-018), the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant 1R01AI087520-01A1), and the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013), under the project Collaborative HIV and Anti-HIV Drug Resistance Network (CHAIN) (grant agreement 223131).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 October 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anisimova, M., and O. Gascuel. 2006. Approximate likelihood-ratio test for branches: a fast, accurate, and powerful alternative. Syst. Biol. 55:539-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett, S. N., A. J. Drummond, D. D. Kapan, M. A. Suchard, J. L. Munoz-Jordan, O. G. Pybus, E. C. Holmes, and D. J. Gubler. 2010. Epidemic dynamics revealed in dengue evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27:811-818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Britton, S., K. Hillgren, K. Marosi, K. Sarkar, and S. Elofsson. 2009. Baslinjestudie om blodburen smitta bland injektionsnarkomaner i Stockholms län 1 Juli 2007-31 Augusti 2008. Karolinska Institute, Institution for Medicin, and Maria Beroendecentrum AB, Stockholm, Sweden.

- 4.Drummond, A. J., S. Y. Ho, M. J. Phillips, and A. Rambaut. 2006. Relaxed phylogenetics and dating with confidence. PLoS Biol. 4:e88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drummond, A. J., and A. Rambaut. 2007. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol. Biol. 7:214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drummond, A. J., A. Rambaut, B. Shapiro, and O. G. Pybus. 2005. Bayesian coalescent inference of past population dynamics from molecular sequences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22:1185-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.EuroHIV. 2007. HIV/AIDS Surveillance in Europe. Mid-year report 2007. Institut de Veille Sanitaire, Saint-Maurice, France.

- 8.Fraser, C., T. D. Hollingsworth, R. Chapman, F. de Wolf, and W. P. Hanage. 2007. Variation in HIV-1 set-point viral load: epidemiological analysis and an evolutionary hypothesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:17441-17446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gueudin, M., J. C. Plantier, V. Lemee, M. P. Schmitt, L. Chartier, T. Bourlet, A. Ruffault, F. Damond, M. Vray, and F. Simon. 2007. Evaluation of the Roche Cobas TaqMan and Abbott RealTime extraction-quantification systems for HIV-1 subtypes. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 44:500-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guindon, S., and O. Gascuel. 2003. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 52:696-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughes, G. J., E. Fearnhill, D. Dunn, S. J. Lycett, A. Rambaut, and A. J. Leigh Brown. 2009. Molecular phylodynamics of the heterosexual HIV epidemic in the United Kingdom. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katoh, K., K. Kuma, H. Toh, and T. Miyata. 2005. MAFFT version 5: improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:511-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kivela, P., A. Krol, S. Simola, M. Vaattovaara, P. Tuomola, H. Brummer-Korvenkontio, and M. Ristola. 2007. HIV outbreak among injecting drug users in the Helsinki region: social and geographical pockets. Eur. J. Public Health 17:381-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kivela, P. S., A. Krol, M. O. Salminen, R. B. Geskus, J. I. Suni, V. J. Anttila, K. Liitsola, V. Zetterberg, F. Miedema, B. Berkhout, R. A. Coutinho, and M. A. Ristola. 2005. High plasma HIV load in the CRF01-AE outbreak among injecting drug users in Finland. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 37:276-283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kivela, P. S., A. Krol, M. O. Salminen, and M. A. Ristola. 2010. Determinants of late HIV diagnosis among different transmission groups in Finland from 1985 to 2005. HIV Med. 11:360-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Labbett, W., A. Garcia-Diaz, Z. Fox, G. S. Clewley, T. Fernandez, M. Johnson, and A. M. Geretti. 2009. Comparative evaluation of the ExaVir Load version 3 reverse transcriptase assay for measurement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 plasma load. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3266-3270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leitner, T., and J. Albert. 1999. The molecular clock of HIV-1 unveiled through analysis of a known transmission history. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:10752-10757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemey, P., A. Rambaut, A. J. Drummond, and M. A. Suchard. 2009. Bayesian phylogeography finds its roots. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5:e1000520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lidman, C., L. Norden, M. Kaberg, K. Kall, J. Franck, S. Aleman, and M. Birk. 2009. Hepatitis C infection among injection drug users in Stockholm, Sweden: prevalence and gender. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 41:679-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liitsola, K., P. Holmstrom, T. Laukkanen, H. Brummer-Korvenkontio, P. Leinikki, and M. O. Salminen. 2000. Analysis of HIV-1 genetic subtypes in Finland reveals good correlation between molecular and epidemiological data. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 32:475-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liitsola, K., M. Ristola, P. Holmstrom, M. Salminen, H. Brummer-Korvenkontio, S. Simola, J. Suni, and P. Leinikki. 2000. An outbreak of the circulating recombinant form AECM240 HIV-1 in the Finnish injection drug user population. AIDS 14:2613-2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lukashov, V., C. Kuiken, D. Vlahov, R. Coutinho, and J. Goudsmit. 1996. Evidence for HIV type 1 strains of U.S. intravenous drug users as founders of AIDS epidemic among intravenous drug users in northern Europe. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 12:1179-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maljkovic Berry, I., R. Ribeiro, M. Kothari, G. Athreya, M. Daniels, H. Y. Lee, W. Bruno, and T. Leitner. 2007. Unequal evolutionary rates in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) pandemic: the evolutionary rate of HIV-1 slows down when the epidemic rate increases. J. Virol. 81:10625-10635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newton, M. A., and A. E. Raftery. 1994. Approximate Bayesian inference by the weighted likelihood bootstrap. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 56:3-48. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norden, L., and C. Lidman. 2005. Differentiated risk behaviour for HIV and hepatitis among injecting drug users (IDUs). Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 37:493-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norden, L., and C. Lidman. 2003. Needle sharing with known and diagnosed human immunodeficiency virus-infected injecting drug users. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 35:127-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Op de Coul, E. L., M. Prins, M. Cornelissen, A. van der Schoot, F. Boufassa, R. P. Brettle, L. Hernandez-Aguado, V. Schiffer, J. McMenamin, G. Rezza, R. Robertson, R. Zangerle, J. Goudsmit, R. A. Coutinho, and V. V. Lukashov. 2001. Using phylogenetic analysis to trace HIV-1 migration among Western European injecting drug users seroconverting from 1984 to 1997. AIDS 15:257-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pybus, O. G., A. J. Drummond, T. Nakano, B. H. Robertson, and A. Rambaut. 2003. The epidemiology and iatrogenic transmission of hepatitis C virus in Egypt: a Bayesian coalescent approach. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20:381-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quinn, T. C., M. J. Wawer, N. Sewankambo, D. Serwadda, C. Li, F. Wabwire-Mangen, M. O. Meehan, T. Lutalo, and R. H. Gray. 2000. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Rakai Project Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 342:921-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rambaut, A., and E. Holmes. 2009. The early molecular epidemiology of the swine-origin A/H1N1 human influenza pandemic. PLoS Curr. 1:RRN1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.R Development Core Team. 2008. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org.

- 32.Shapiro, B., A. Rambaut, and A. J. Drummond. 2006. Choosing appropriate substitution models for the phylogenetic analysis of protein-coding sequences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23:7-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skar, H., S. Sylvan, H. B. Hansson, O. Gustavsson, H. Boman, J. Albert, and T. Leitner. 2008. Multiple HIV-1 introductions into the Swedish intravenous drug user population. Infect. Genet. Evol. 8:545-552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slatkin, M., and W. P. Maddison. 1989. A cladistic measure of gene flow inferred from the phylogenies of alleles. Genetics 123:603-613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strimmer, K., and A. von Haeseler. 1997. Likelihood-mapping: a simple method to visualize phylogenetic content of a sequence alignment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:6815-6819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suchard, M. A., R. E. Weiss, and J. S. Sinsheimer. 2001. Bayesian selection of continuous-time Markov chain evolutionary models. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18:1001-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swofford, D. L. 2002. PAUP*: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods), 4.0b10. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA.

- 38.Volz, E. M., S. L. Kosakovsky Pond, M. J. Ward, A. J. Leigh Brown, and S. D. Frost. 2009. Phylodynamics of infectious disease epidemics. Genetics 183:1421-1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zetterberg, V., V. Ustina, K. Zilmer, K. Liitsola, N. Kalikova, K. Sevastianova, H. Brummer-Korvenkontio, P. Leinikki, and M. Salminen. 2004. Two viral strains and a possible novel recombinant are responsible for the explosive injecting drug use-associated HIV type 1 epidemic in Estonia. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 20:1145-1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.