Abstract

N-Formyl peptide receptors (FPRs) are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) involved in host defense and sensing cellular dysfunction. Thus, FPRs represent important therapeutic targets. In the present studies, we screened 32 ligands (agonists and antagonists) of unrelated GPCRs for their ability to induce intracellular Ca2+ mobilization in human neutrophils and HL-60 cells transfected with human FPR1, FPR2, or FPR3. Screening of these compounds demonstrated that antagonists of gastrin-releasing peptide/neuromedin B receptors (BB1/BB2) PD168368 [(S)-a-methyl-a-[[[(4-nitrophenyl)amino]carbonyl]amino]-N-[[1-(2-pyridinyl) cyclohexyl]methyl]-1H-indole-3-propanamide] and PD176252 [(S)-N-[[1-(5-methoxy-2-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]-a-methyl-a-[[-(4-nitrophenyl)amino]carbonyl]amino-1H-indole-3-propanamide] were potent mixed FPR1/FPR2 agonists, with nanomolar EC50 values. Cholecystokinin-1 receptor agonist A-71623 [Boc-Trp-Lys(ε-N-2-methylphenylaminocarbonyl)-Asp-(N-methyl)-Phe-NH2] was also a mixed FPR1/FPR2 agonist, but with a micromolar EC50. Screening of 56 Trp- and Phe-based PD176252/PD168368 analogs and 41 related nonpeptide/nonpeptoid analogs revealed 22 additional FPR agonists. Most were potent mixed FPR1/FPR2/FPR3 agonists with nanomolar EC50 values for FPR2, making them among the most potent nonpeptide FPR2 agonists reported to date. In addition, these agonists were also potent chemoattractants for murine and human neutrophils and activated reactive oxygen species production in human neutrophils. Molecular modeling of the selected agonists using field point methods allowed us to modify our previously reported pharmacophore model for the FPR2 ligand binding site. This model suggests the existence of three hydrophobic/aromatic subpockets and several binding poses of FPR2 agonists in the transmembrane region of this receptor. These studies demonstrate that FPR agonists could include ligands of unrelated GPCR and that analysis of such compounds can enhance our understanding of pharmacological effects of these ligands.

Introduction

N-Formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenyalanine (fMLF) is one of the most studied phagocyte chemoattractants and represents a prototype for microbe-derived formylated peptides (Schiffmann et al., 1975). Recent studies have shown that formylated peptides are also produced by mitochondria and can be released when mitochondria are damaged during tissue injury (Raoof et al., 2010). N-Formyl peptides activate cells through formyl peptide receptors (FPRs), which are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) (for review, see Ye et al., 2009). The three human FPRs (FPR1, FPR2, and FPR3) are expressed on a variety of cell types, including neutrophils, macrophages, T lymphocytes, epithelial cells, hepatocytes, fibroblasts, astrocytes, and other cells that serve a variety of regulatory functions during the host defense response (for review, see Ye et al., 2009; Gavins, 2010). For example, FPR1 and FPR2 have been implicated in control of endogenous inflammatory processes and initiation of proinflammatory neutrophil responses to pathogenic bacteria (Kretschmer et al., 2010). The diverse tissue expression of these receptors suggests the possibility of as-yet unappreciated complexity in the innate response and perhaps other unidentified functions for FPR family members. For example, mouse FPRs have been reported to be candidate chemosensory receptors in the vomeronasal organ (Liberles et al., 2009). Likewise, several studies have suggested that FPR2 agonists exhibit protective effects in ischemia-reperfusion models (for review, see Gavins, 2010). Overall, the demonstrated role of FPRs in orchestrating acute-phase inflammation supports the development of FPR agonists as novel anti-inflammatory therapeutics (Dufton and Perretti, 2010).

The conserved seven-transmembrane structure of GPCRs suggests the possibility that this superfamily may have evolved from a single ancestral protein (Fredriksson et al., 2003). Indeed, the common seven-transmembrane structure and the presence of universally conserved residues in each of the TM helices make it possible to build rough models of the helical bundle for diverse GPCRs (Katritch et al., 2010). On the basis of this structural conservation, privileged scaffolds can be selected that are able to provide high-affinity ligands for more than one type of receptor by targeting common conserved motifs of the GPCR superfamily (Parravicini et al., 2010). Indeed, such structural motifs have been successfully used to design and synthesize combinatorial libraries to probe for novel GPCR targets (Gloriam et al., 2009). Furthermore, it has been shown that various compounds can act as both agonists and/or antagonists for several GPCRs within the same or different subfamilies. For example, bile acids are antagonists of FPR1/FPR2 (Chen et al., 2000) and agonists for TGR5, a GPCR involved in regulating thyroid hormone signaling and energy homeostasis (Kawamata et al., 2003). Thus, it is reasonable that known GPCR ligands (agonists and/or antagonists) could be used in screening of unrelated GPCR targets to identify novel therapeutics.

To provide further insight in the specificity of different previously described GPCR ligands and identify novel and potentially higher affinity FPR agonists, we screened 32 relatively low-molecular weight ligands (agonists and antagonists) of 24 unrelated GPCRs using a Ca2+ mobilization assay in human neutrophils and HL-60 cells transfected with human FPR1, FPR2, or FPR3. It is noteworthy that we found that two bombesin-related BB1/BB2 antagonists, PD168368 [(S)-a-methyl-a-[[[(4-nitrophenyl)amino]carbonyl]amino]-N-[[1-(2-pyridinyl) cyclohexyl]methyl]-1H-indole-3-propanamide] and PD176252 [(S)-N-[[1-(5-methoxy-2-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]-a-methyl-a-[[-(4-nitrophenyl)amino]carbonyl]amino-1H-indole-3-propanamide], were potent mixed FPR agonists, with EC50 values in the nanomolar range. After further structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis and analog screening, we identified 22 additional mixed FPR agonists with EC50 values in the low micromolar and nanomolar ranges. In addition, these agonists were also potent chemoattractants for murine and human neutrophils and activated reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in human neutrophils. Molecular modeling of selected FPR agonists using the field point method allowed us to modify our previously reported pharmacophore model (Kirpotina et al., 2010) for the ligand binding site of FPR2. These studies demonstrate for the first time that selected bombesin receptor BB1/BB2 antagonists, PD176252 and PD168368, their Trp- and Phe-based derivatives, and related nonpeptoid/nonpeptide analogs are potent FPR agonists and that analysis of such compounds can enhance our understanding of ligand-FPR interactions.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

8-Amino-5-chloro-7-phenylpyridol[3,4-d]pyridazine-1,4(2H,3H)-dione (L-012) was obtained from Wako Chemicals (Richmond, VA). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), horseradish peroxidase, fMLF, and Histopaque 1077 were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Peptides Trp-Lys-Tyr-Met-Val-d-Met (WKYMVm) and Trp-Lys-Tyr-Met-Val-l-Met (WKYMVM) were from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA) and Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO), respectively. Tetramethylbenzidine was from BD Biosciences Pharmingen (San Diego, Ca). RPMI-1640 medium without phenol red was from Lonza Walkersville, Inc. (Walkersville, MD). Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS; 0.137 M NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 0.25 mM Na2HPO4, 0.44 mM KH2PO4, 4.2 mM NaHCO3, 5.56 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). HBSS containing 1.3 mM CaCl2 and 1.0 mM MgSO4 is designated HBSS+. Percoll stock solution was prepared by mixing Percoll with 10× HBSS at a ratio of 9:1.

Screening compounds were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO), ChemBridge (San Diego, CA), InterBioScreen (Moscow, Russia), Albany Molecular Research (Albany, NY), and ChemDiv (San Diego, CA). The purity and identity of the compounds were verified using NMR spectroscopy, elemental analysis, and mass spectroscopy, as performed by the suppliers. The compounds were diluted in DMSO at a concentration of 20 mM and stored at −20°C.

Cell Culture.

Human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells stably transfected with human FPR1, FPR2, or FPR3 were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 10 mM HEPES, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 U/ml penicillin, and G418 (1 mg/ml), as described previously (Christophe et al., 2002). Wild-type HL-60 cells were cultured under the same conditions but without G418.

Neutrophil Isolation.

For isolation of human neutrophils, blood was collected from healthy donors in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board at Montana State University. Neutrophils were purified from the blood using dextran sedimentation, followed by Histopaque 1077 gradient separation and hypotonic lysis of red blood cells, as described previously (Schepetkin et al., 2007). Isolated neutrophils were washed twice and resuspended in HBSS. Neutrophil preparations were routinely >95% pure, as determined by light microscopy, and >98% viable, as determined by trypan blue exclusion.

For murine neutrophil isolation, bone marrow leukocytes were flushed from tibias and femurs of BALB/c mice with HBSS, filtered through a 70-μm nylon cell strainer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) to remove cell clumps and bone particles, and resuspended in HBSS at 106 cells/ml. Bone marrow neutrophils were isolated from bone marrow leukocyte preparations, as described previously (Schepetkin et al., 2007). In brief, bone marrow leukocytes were resuspended in 3 ml of 45% Percoll solution and layered on top of a Percoll gradient consisting of 2 ml each of 50, 55, 62, and 81% Percoll solutions in a conical 15-ml polypropylene tube. The gradient was centrifuged at 1600g for 30 min at 10°C, and the cell band located between the 61 and 81% Percoll layers was collected. The cells were washed, layered on top of 3 ml of Histopaque 1119, and centrifuged at 1600g for 30 min at 10°C to remove contaminating red blood cells. The purified neutrophils were collected, washed, and resuspended in HBSS. All animal use was conducted in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Montana State University.

Ca2+ Mobilization Assay.

Changes in intracellular Ca2+ were measured with a FlexStation II scanning fluorometer using fluorescent dye Fluo-4AM (Invitrogen) for human and murine neutrophils and HL-60 cells. All active compounds were evaluated in wild-type HL-60 cells to verify that the agonists were inactive in nontransfected cells. Neutrophils or HL-60 cells, suspended in HBSS, were loaded with Fluo-4AM dye (final concentration, 1.25 μg/ml) and incubated for 30 min in the dark at 37°C. After dye loading, the cells were washed with HBSS, resuspended in HBSS+, separated into aliquots, and deposited into the wells of flat-bottomed, half-area-well black microtiter plates (2 × 105 cells/well). The compound source plate contained dilutions of test compounds in HBSS+. Changes in fluorescence were monitored (λex = 485 nm, λem = 538 nm) every 5 s for 240 s at room temperature after automated addition of compounds. Maximum change in fluorescence, expressed in arbitrary units over baseline, was used to determine agonist response. Responses were normalized to the response induced by 5 nM fMLF for HL-60 FPR1 and neutrophils or 5 nM WKYMVm for HL-60 FPR2 and HL-60 FPR3 cells, which were assigned a value of 100%. Curve fitting (at least five to six points) and calculation of median effective concentration values (EC50) were performed by nonlinear regression analysis of the dose-response curves generated using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA).

Degranulation Assay.

Degranulation of azurophil granules was determined by measuring release of myeloperoxidase (MPO), as described previously (Zhang et al., 2007b). Human neutrophils (5 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI-1640) were treated with test compounds, fMLF, or DMSO, incubated for 30 min at 37°C, and centrifuged at 550g for 3 min. Aliquots of the supernatants (100 μl) were mixed with 100 μl of tetramethylbenzidine in a 96-well flat-bottomed transparent microtiter plate and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. The reaction was terminated by addition of 50 μl of 5% phosphoric acid, and the absorbance was read at 450 nm in a SpectraMax Plus microtiter plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Chemotaxis Assay.

Human or murine neutrophils were suspended in HBSS+ containing 2% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (2 × 106 cells/ml), and chemotaxis was analyzed in 96-well ChemoTx chemotaxis chambers (Neuroprobe, Gaithersburg, MD), as described previously (Schepetkin et al., 2007). In brief, lower wells were loaded with 30 μl of HBSS+ containing 2% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and the indicated concentrations of test compounds, DMSO (negative control), or 1 nM fMLF as a positive control. Neutrophils were added to the upper wells and allowed to migrate through the 5.0-μm pore polycarbonate membrane filter for 60 min at 37°C and 5% CO2. The number of migrated cells was determined by measuring ATP in lysates of transmigrated cells using a luminescence-based assay (CellTiter-Glo; Promega, Madison, WI), and luminescence measurements were converted to absolute cell numbers by comparison of the values with standard curves obtained with known numbers of neutrophils. Curve fitting (at least eight to nine points) and calculation of median effective concentration values (EC50) were performed by nonlinear regression analysis of the dose-response curves generated using Prism 5.

Analysis of ROS Production.

ROS production was determined by monitoring L-012–enhanced chemiluminescence, which represents a sensitive and reliable method for detecting ROS production (Daiber et al., 2004). Human neutrophils were resuspended at 5 × 105 cells/ml in HBSS+ and supplemented with 40 μM L-012 and 8 μg/ml horseradish peroxidase. Cells (100 μl) were separated into aliquots and placed in wells of 96-well flat-bottomed white microtiter plates containing test compounds diluted in 100 μl of HBSS+ (final DMSO concentration of 0.5%). Changes in luminescence were monitored every 5 s for 120 s at room temperature using a Fluoroskan Ascent FL microtiter plate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The curve of light intensity (in relative luminescence units) was plotted against time, and the area under the curve was calculated as total luminescence. Curve fitting (at least five to six points) and calculation of median effective concentration values (EC50) were performed by nonlinear regression analysis of the dose-response curves generated using Prism 5.

Molecular Modeling.

Five agonists with known enantiomeric configurations and relatively high activity at FPR2 were chosen for pharmacophore modeling. The selected structures included PD168368, AG-10/5, AG-10/8, AG-10/17, and compound 11 from (Frohn et al., 2007) [1-((5-methoxyindol-2-yl)carbonyl)-3-(2-ethylbenzimidazol-1-yl)(3R)pyrrolidine; designated here as Frohn-11]. We used a ligand-based approach for molecular modeling based on the use of field points (Cheeseright et al., 2007), as described in our previous studies (Kirpotina et al., 2010). The structures of the compounds in Tripos MOL2 format were imported into the FieldTemplater program (FieldTemplater Version 2.0.1; Cresset Biomolecular Discovery Ltd., Hertfordshire, UK). The conformation hunter algorithm was used to generate representative sets of conformations corresponding to local minima of energy calculated within the extended electron distribution force field (Vinter, 1994; Cheeseright et al., 2007). This algorithm incorporated in the FieldTemplater and FieldAlign software allowed us to obtain up to 200 independent conformations that were passed to further calculation of field points surrounding each conformation of each molecule. To decrease the number of rotatable bonds during the conformation search, the “force amides trans” option was enabled in the program. For the generation of field point patterns, probe atoms having positive, negative, and zero charge were placed in the vicinity of a given conformation, and the energy of their interaction with the molecular field was calculated using the extended electron distribution parameter set. Positions of energy extrema for positive probes give “negative” field points, whereas energy extrema for negative and neutral probe atoms correspond to “positive” and steric field points, respectively. Hydrophobic field points were also generated with neutral probes capable of penetrating into the molecular core and reaching extrema in the centers of hydrophobic regions (e.g., benzene rings). The size of a field point depends on magnitude of an extremum (Cheeseright et al., 2006). There are approximately the same number of field points as heavy atoms in a “drug-like” molecule, and the field points are colored according to the following convention: blue, electron-rich (negative); red, electron-deficient (positive); yellow, van der Waals attractive (steric); and orange, hydrophobic (Cheeseright et al., 2007). A detailed description of the field point calculation procedure has been published elsewhere (Cheeseright et al., 2006). A clique-matching algorithm with further simplex optimization was applied to obtain the conformations of five molecules giving good mutual overlays in terms of geometric and field similarity. The best overlay was taken as a template representative of the bioactive conformation.

Additional FPR2-specific agonists, including compound 25 [N-(4-bromophenyl)-N-(1,5-dimethyl-3-oxo-2-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)urea; designated here as Bürli-25] (Bürli et al., 2006), compound 14x [N-(4-bromophenyl)-2-[5-(4-methoxybenzyl)-3-methyl-6-oxo-6H-pyridazin-1-yl]-acetamide; designated here as Cilibrizzi-14x] (Cilibrizzi et al., 2009), AG-09/3, AG-09/4, AG-09/5, AG-09/6, AG-09/8, and AG-09/42 and mixed FPR1/FPR2 agonists AG-09/9, AG-09/10 (Kirpotina et al., 2010) were superimposed onto the template using the FieldAlign program (FieldAlign Version 2.0.1; Cresset Biomolecular Discovery Ltd., Hertfordshire, UK). The molecular structures were imported into FieldAlign in Tripos MOL2 format. Conformational search and field point calculation were performed as described above for template building. Conformations with the best fit to the geometry and field points of the template were identified, and their superimpositions were refined by the simplex optimization algorithm incorporated in FieldAlign.

Results

Identification of FPR Agonists by Screening of Known GPCR Ligands.

The subset of 32 ligands was selected from the parent library of 100 different GPCR ligands as compounds that contained at least two heterocycles separated by a chemical linker with >2 bonds, because previous studies have shown that these characteristics are almost always present in low-molecular weight synthetic FPR1/FPR2 agonists (Nanamori et al., 2004; Edwards et al., 2005; Bürli et al., 2006; Frohn et al., 2007; Schepetkin et al., 2007, 2008; Kirpotina et al., 2010). The selected 32 compounds represented ligands of 24 different GPCR, including a nociceptin receptor agonist [(8-naphthalen-1-ylmethyl-4-oxo-1-phenyl-1,3,8-triaza-spiro(4.5)-dec-3-yl)acetic acid methyl ester (NNC 63-0532)], three cholecystokinin-1 (CCK-1) receptor antagonists [devazepide, Boc-Trp-Lys(ε-N-2-methylphenylaminocarbonyl)-Asp-(N-methyl)-Phe-NH2 (A-71623), and 1-((2-(4-(2-chlorophenyl)thiazol-2-yl)aminocarbonyl)indolyl)acetic acid (SR 27897)], two CCK-2 receptor antagonists [1-(2,3-dihydro-1-(2′-methylphenacyl)-2-oxo-5-phenyl-1H-1,4-benzodiazepin-3-yl)-3-(3-methylphenyl)urea (YM 022) and 1-(4-bromophenylaminocarbonyl)-4,5-diphenyl-3-pyrazolidinone (LY 288513)], three cannabinoid CB2 receptor ligands [indomethacin morpholinylamide (BML-190), iodopravadoline (AM 630), and 1-(2,3-dichlorobenzoyl)-5-methoxy-2-methyl-3-[2-(4-morpholinyl)ethyl]-1H-indole (GW 405833)], a neuropeptide Y5 receptor antagonist [1-benzoyl-2-[[trans-4-[[[[2-nitro-4-trifluoromethyl)phenyl]sulfonyl]amino]methyl]cyclohexyl]carbonyl]hydrazine (S 25585), two thyrotropin receptor agonists [taltirelin and N-(4-(5-(3-(furan-2-ylmethyl)-4-oxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinazolin-2-yl)-2-methoxybenzyloxy)phenyl)acetamide (NCGC00168126–01)], a vasopressin 1A receptor antagonist [relcovaptan (SR 49059)], a protease-activated receptor 2 agonist [(2E)-2-[1-(3-bromophenyl)ethylidene] α-(benzoylamino)-3,4-dihydro-4-oxo-1-phthalazineacetic acid hydrazide (AC 55541)], a sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor antagonist [1-[1,3-dimethyl-4-(2-methylethyl)-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridin-6-yl]-4-(3,5-dichloro-4-pyridinyl)-semicarbazide (JTE 013)], a neuropeptide FF receptor antagonist [adamantylcarbonyl-arginyl-phenylalaninamide (RF9)], a neurotensin receptor antagonist [2-[[[5-(2,6-dimethoxyphenyl)-1-[4-[[[3-(dimethylamino)propyl]methylamino]carbonyl]-2-(1-methylethyl)phenyl]-1H-pyrazol-3-yl]carbonyl]amino]-tricyclo[3.3.1.13,7]decane-2-carboxylic acid (SR 142948)], an endothelin A receptor antagonist[N-(N-(N-((hexahydro-1H-azepin-1-yl)carbonyl)-l-leucyl)-1-methyl-d-tryptophyl)-3-(2-pyridinyl)-d-alanine (FR 139317)], a cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 antagonist [pranlukast (ONO 1078)], a growth hormone secretagogue receptor 1a agonist [3-[[(2R)-2-hydroxypropyl]amino]-3-methyl-N-[(3R)-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-2-oxo-1-[[2′-(1H-tetrazol-5-yl)[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl]methyl]-1H-1-benzazepin-3-yl]-butanamide (L-692,585)], a gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor antagonist [7-[(2,6-difluorophenyl)methyl]-4,7-dihydro-2-[4-[(2-methyl-1-oxopropyl)amino]phenyl]-3-[[methyl(phenylmethyl)amino]methyl]-4-oxo-thieno[2,3-b]pyridine-5-carboxylic acid 1-methylethyl ester (T 98475)], an oxytocin receptor antagonist [1-(1-(4-((N-acetyl-4-piperidinyl)oxy)-2-methoxybenzoyl)piperidin-4-yl)-4H-3,1-benzoxazin-2(1H)-one(L-371,257)], three tachykinin NK1 receptor antagonists [N(2)-(4-hydroxy-1-(1-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)carbonyl-l-prolyl)-N-methyl-N-phenylmethyl-3-(2-naphthyl)-l-alaninamide (FK 888), 2-nitrophenylcarbamoyl-(S)-prolyl-(S)-3-(2-naphthyl)alanyl-N-benzyl-N-methylamide (SDZ NKT 343), and N-acetyl-l-tryptophan 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)benzyl ester (L-732,138)], a platelet-activating factor receptor antagonist [apafant (WEB 2086)], a prostanoid EP4 receptor antagonist [N-[[4′-[[3-butyl-1,5-dihydro-5-oxo-1-[2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-4>H-1,2,4-triazol-4-yl]methyl][1,1′-biphenyl]-2-yl]sulfonyl]-3-methyl-2-thiophenecarboxamide (L-161,982)], a serotonin 5-HT4 receptor agonist (cisapride), a somatostatin sst2 receptor agonist [2-((spiro(1H-indene-1,4′-piperidin)-1′-ylcarbonyl)amino)-N-(3-aminomethyl-1-cyclohexylmethyl)-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)propanamide (L-054,264)], a melanocortin 4 (MC4) receptor agonist (N-[(1R)-1-[(4-chlorophenyl)methyl]-2-[4-cyclohexyl-4-(1H-1,2,4-trazol-1-ylmethyl)-1-piperidinyl]-2-oxoethyl]-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-3-isoquinolinecarboxamide), and two BB1/BB2 antagonists (PD168368 and PD176252).

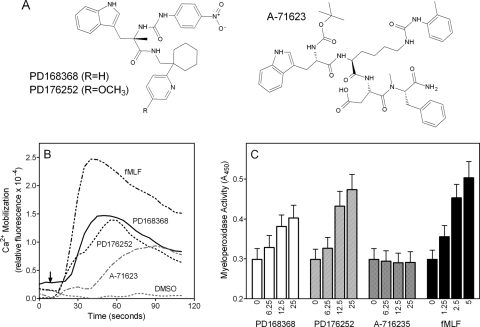

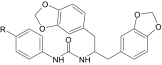

Screening of the 32 GPCR ligands for their ability to induce Ca2+ mobilization in human neutrophils demonstrated that three such compounds were indeed neutrophil agonists. Structures of the active compounds and representative kinetic curves for Ca2+ mobilization in human neutrophils are shown in Fig. 1, and activities of the compounds are reported in Table 1. The CCK-1 receptor agonist A-71623 (Sugg et al., 1995) exhibited modest activity, with an EC50 of ∼18.3 μM. In contrast, the bombesin-related BB1/BB2 antagonists PD168368 (Ryan et al., 1999) and PD176252 (Ashwood et al., 1998) were highly active and stimulated [Ca2+]i release in human neutrophils with EC50 values in the nanomolar range. In addition, PD168368 and PD176252 stimulated degranulation of neutrophil azurophil granules (i.e., release of MPO) comparable with that induced by fMLF (Fig. 1C). In contrast, A-71623 did not induce azurophil degranulation over the concentration range tested, indicating that it may activate a different array of responses than PD168368/PD176252.

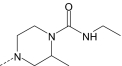

Fig. 1.

Structure and activity of selected GPCR agonists. A, chemical structures of CCK-1 receptor agonist A-71623 and bombesin-related receptor BB1 and BB2 antagonists PD176252 and PD168368. B, human neutrophils were treated with 300 nM PD176252 or PD168368, 20 μM A-716235, 5 nM fMLF (positive control), or 1% DMSO (negative control), and Ca2+ mobilization was monitored for the indicated times (arrow indicates when treatment was added). Arrow indicates time of treatment addition. C, human neutrophils were treated with the indicated concentrations of PD168368, PD176252, A-716235, and fMLF (all in micromolar), and MPO release was determined as described under Materials and Methods. The data are presented as mean ± S.D. of triplicate samples. In B and C, the data are from one experiment that is representative of three independent experiments.

TABLE 1.

Previously reported GPCR ligands that induced Ca2+ mobilization in human neutrophils and FPR-transfected HL-60 cells

The EC50 values are presented as the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments, in which median effective concentration values (EC50) were determined by nonlinear regression analysis of the dose-response curves (five to six points) generated using GraphPad Prism 5 with 95% confidence interval (P < 0.05). Efficacy is expressed as percentage of the response induced by 5 nM fMLF (FPR1) or 5 nM WKYMVm (FPR2 and FPR3).

| Compound | Previously Reported Activity for GPCR | Ca2+ Mobilization,

EC50, and Efficacy |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophils | FPR1 | FPR2 | FPR3 | ||

| μM (%) | |||||

| PD168368 | BB1 antagonist | 0.91 ± 0.34 (70) | 0.57 ± 0.17 (95) | 0.24 ± 0.08 (90) | 2.7 ± 0.4 (60) |

| PD176252 | BB1/BB2 antagonist | 0.72 ± 0.21 (75) | 0.31 ± 0.09 (100) | 0.66 ± 0.12 (95) | N.A. |

| A-71623 | CCK-1 receptor agonist | 18.3 ± 3.1 (55) | 18.0 ± 3.8 (50) | 16.4 ± 3.1 (85) | N.A. |

N.A., nonactive compound (cell activation was <30% of control level over a concentration range of 0–40 μM).

Specificity of the selected neutrophil agonists was verified by their ability to activate Ca2+ mobilization in HL-60 cells transfected with human FPRs, and we found A-71623 and PD176252 to be mixed FPR1/FPR2 agonists, whereas PD168368 was a mixed FPR1/FPR2/FPR3 agonist (Table 1). PD176252 and PD168368 had very high efficacy, inducing responses similar in amplitude to those induced by fMLF or WKYMVm, whereas A-71623 had somewhat lower efficacy. No response was observed in control, untransfected HL-60 cells treated with these compounds. The activities of PD176252 and PD168368 in HL-60 FPR2 cells were higher than or comparable with previously reported nonpeptide FPR2 agonists, such as Quin-C1 (EC50 = 1.4 μM) (Nanamori et al., 2004) and AG-09/42 (EC50 = 0.1 μM) (Kirpotina et al., 2010), or synthetic peptides, such as HFYLPM and its analogs (Bae et al., 2003a). Thus, our data demonstrate that the CCK-1 receptor agonist A-71623 and the bombesin-related BB1/BB2 antagonists PD168368 and PD176252 can interact with GPCR unrelated to CCK-1 and BB1/BB2, respectively.

Because PD168368 and PD176252 were the most potent FPR agonists from our screen, we focused further efforts on investigation these compounds and their analogs. To determine whether other bombesin-related receptor ligands activated Ca2+ mobilization in human neutrophils and FPR-transfected HL-60 cells, we evaluated nine other commercially available BB1/BB2 ligands, including three agonists [1-de(5-oxo-l-proline)-2-de-l-valine-3-d-phenylalanine-10-l-leucine-11-l-leucinamide-ranatensin (BIM 187), bombesin, and gastrin-releasing peptide] and six antagonists [1-de(5-oxo-l-proline)-2-de-l-valine-3-d-phenylalanine-10-l-leucine-11-(4-chloro-l-phenylalaninamide)-ranatensin (BIM 189), d-Nal-Cys-Tyr-d-Trp-Lys-Val-Cys-Nal-NH2 (BIM 23042), d-Nal-Cys-Tyr-d-Trp-Orn-Val-Cys-Nal-NH2 (BIM 23127), [d-Phe12]-bombesin, [d-Phe12,Leu14]-bombesin, and N-isobutyryl-His-Trp-Ala-Val-d-Ala-His-Leu-NHMe (ICI 216,140)]. None of these ligands was found to activate neutrophil Ca2+ mobilization when tested over a concentration range of 1–50 μM, and these ligands (at concentrations of 1 and 10 μM) did not desensitize WKYMVm-induced Ca2+ mobilization in human neutrophils (data not shown). Thus, our results suggest that FPR agonist activity is due to specific structural features of PD168368 and PD176252 and not to a general effect of all BB1/BB2 ligands. In addition, these data support the conclusion that PD168368 and PD176252 are true FPR ligands and are not stimulating cells through bombesin receptors.

Identification of Additional FPR Agonists by Screening PD168368/PD176252 Analogs.

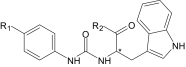

The BB1/BB2 antagonists PD168368 and PD176252 are characterized by a peptoid scaffold but also include an N-phenylurea substructure on one end of the molecule (see Fig. 1A). We found previously that N-phenethyl-N′-phenylurea derivatives activated neutrophil functional responses and included FPR2-specific agonists (Schepetkin et al., 2008; Kirpotina et al., 2010). Likewise, Bürli et al. (2006) identified potent and specific FPR2 agonists with a 1-(3-oxo-2-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-3-phenylurea scaffold. Because aromatic amino acids (Trp, Phe, and Tyr) of peptide FPR1/FPR2 agonists have also been shown to be important moieties for ligand-receptor interactions (Bae et al., 2003b, 2004; Cavicchioni et al., 2006; Wan et al., 2007; Movitz et al., 2010), we selected Trp- and Phe-based N-phenylurea derivatives and related analogs for further screening. These 97 compounds included 7 Trp-based, 49 Phe-based, and 41 other nonpeptoid derivatives (see Tables 2–5 and Supplemental Table S1 for structural details).

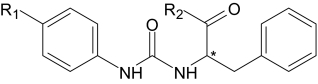

TABLE 2.

Trp-based derivatives that induced Ca2+ mobilization in human neutrophils and FPR-transfected HL-60 cells

The EC50 values are presented as the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments, in which median effective concentration values (EC50) were determined by nonlinear regression analysis of the dose-response curves (five to six points) generated using GraphPad Prism 5 with 95% confidence interval (P < 0.05). Efficacy is expressed as percentage of the response induced by 5 nM fMLF (FPR1) or 5 nM WKYMVm (FPR2 and FPR3).

| Compound | R1 | R2 | Enantiomer | Ca2+ Mobilization,

EC50, and Efficacy |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophils | FPR1 | FPR2 | FPR3 | ||||

| μM (%) | |||||||

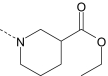

| AG-10/1 | H |

|

R/S | 3.8 ± 0.5 (120) | 2.7 ± 0.4 (100) | 0.3 ± 0.07 (115) | 13.5 ± 3.4 (60) |

| AG-10/2 | Br |

|

S | 1.9 ± 0.5 (125) | 0.5 ± 0.1 (120) | 0.13 ± 0.03 (120) | 7.6 ± 1.9 (85) |

| AG-10/3 | Br |

|

S | 2.7 ± 0.6 (135) | 2.2 ± 0.6 (120) | 0.3 ± 0.06 (110) | 2.4 ± 0.5 (80) |

N.A., nonactive compound (cell activation was <30% of control level over a concentration range of 0–40 μM).

*Location of the chiral center.

TABLE 3.

Phe-based derivatives that induced Ca2+ mobilization in human neutrophils and FPR-transfected HL-60 cells

The EC50 values are presented as the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments, in which median effective concentration values (EC50) were determined by nonlinear regression analysis of the dose-response curves (five to six points) generated using GraphPad Prism 5 with 95% confidence interval (P < 0.05). Efficacy is expressed as percentage of the response induced by 5 nM fMLF (FPR1) or 5 nM WKYMVm (FPR2 and FPR3).

| Compound | R1 | R2 | Enan-tiomer | Ca2+ Mobilization,

EC50, and Efficacy |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophils | FPR1 | FPR2 | FPR3 | ||||

| μM (%) | |||||||

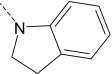

| AG-10/4 | Br |

|

S | 3.2 ± 0.6 (115) | 4.5 ± 1.1 (90) | 0.14 ± 0.05 (100) | 11.5 ± 2.8 (55) |

| AG-10/5 | Br |

|

S | 1.2 ± 0.3 (140) | 1.8 ± 0.5 (130) | 0.04 ± 0.02 (115) | 6.5 ± 1.7 (85) |

| AG-10/6 | Cl |

|

S | 0.5 ± 0.2 (140) | 2.9 ± 0.7 (100) | 0.05 ± 0.01 (95) | 3.1 ± 0.8 (65) |

| AG-10/7 | S-CH3 |

|

S | 6.6 ± 1.4 (50) | 6.0 ± 1.4 (45) | 0.3 ± 0.08 (75) | N.A. |

| AG-10/8 | Br |

|

S | 0.7 ± 0.2 (145) | 0.3 ± 0.08 (135) | 0.004 ± 0.002 (115) | 0.1 ± 0.03 (90) |

| AG-10/9 | Br |

|

S | 0.5 ± 0.1 (110) | 0.08 ± 0.02 (100) | 0.007 ± 0.003 (100) | 0.5 ± 0.1 (50) |

| AG-10/10 | Br |

|

S | 4.4 ± 1.2 (85) | N.A. | 0.16 ± 0.04 (85) | N.A. |

| AG-10/11 | Br |

|

R/S | 9.7 ± 0.2 (90) | 6.7 ± 1.6 (75) | 0.25 ± 0.06 (55) | N.A. |

| AG-10/12 | Cl |

|

S | 10.5 ± 2.6 (100) | 4.2 ± 0.9 (85) | 0.7 ± 0.3 (55) | N.A. |

| AG-10/13 | CH2CH3 |

|

S | 10.8 ± 2.2 (110) | 3.1 ± 0.7 (105) | 1.6 ± 0.3 (75) | N.A. |

N.A., nonactive compound (cell activation was <30% of control level over a concentration range of 0–40 μM).

*Location of the chiral center.

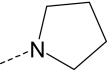

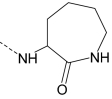

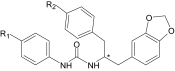

TABLE 4.

N-[1,3-Di(benzodioxolan-5-yl)propan-2-yl]-N-phenylurea derivatives that induced Ca2+ mobilization in human neutrophils and FPR-transfected HL-60 cells

The EC50 values are presented as the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments, in which median effective concentration values (EC50) were determined by nonlinear regression analysis of the dose-response curves (five to six points) generated using GraphPad Prism 5 with 95% confidence interval (P < 0.05). Efficacy is expressed as percentage of the response induced by 5 nM fMLF (FPR1) or 5 nM WKYMVm (FPR2 and FPR3).

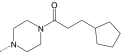

| Compound | R | Ca2+ Mobilization,

EC50, and Efficacy |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophils | FPR1 | FPR2 | FPR3 | ||

| μM (%) | |||||

| AG-10/14 | H | 5.9 ± 1.4 (85) | N.A. | 0.006 ± 0.002 (95) | 3.3 ± 0.7 (45) |

| AG-10/15 | F | 0.7 ± 0.2 (120) | 1.7 ± 0.3 (90) | 0.004 ± 0.001 (100) | 0.7 ± 0.2 (35) |

| AG-10/16 | Cl | 0.06 ± 0.02 (150) | 3.7 ± 0.8 (110) | 0.002 ± 0.0006 (100) | 0.2 ± 0.05 (90) |

| AG-10/17 | Br | 0.1 ± 0.03 (130) | 2.7 ± 0.5 (95) | 0.004 ± 0.001 (105) | 1.7 ± 0.4 (90) |

| AG-10/18 | CH3 | 4.5 ± 1.2 (45) | 5.1 ± 1.8 (50) | 0.07 ± 0.02 (95) | 10.8 ± 3.3 (40) |

N.A., nonactive compound (cell activation was <30% of control level over a concentration range of 0–40 μM).

*Location of the chiral center.

TABLE 5.

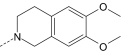

N-[2-(1,3-Benzodioxol-5-yl)-1-benzylethyl]-N-phenylurea R/S derivatives that induced Ca2+ mobilization in human neutrophils and FPR-transfected HL-60 cells

The EC50 values are presented as the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments, in which median effective concentration values (EC50) were determined by nonlinear regression analysis of the dose-response curves (five to six points) generated using GraphPad Prism 5 with 95% confidence interval (P < 0.05). Efficacy is expressed as percentage of the response induced by 5 nM fMLF (FPR1) or 5 nM WKYMVm (FPR2 and FPR3).

| Compound | R1 | R2 | Ca2+ Mobilization,

EC50, and Efficacy |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophils | FPR1 | FPR2 | FPR3 | |||

| μM (%) | ||||||

| AG-10/19 | H | F | 1.2 ± 0.3 (115) | N.A. | 0.12 ± 0.03 (90) | 1.3 ± 0.3 (65) |

| AG-10/20 | F | F | 0.14 ± 0.03 (150) | 7.5 ± 1.6 (70) | 0.02 ± 0.005 (105) | 1.2 ± 0.3 (75) |

| AG-10/21 | CH3 | F | 10.1 ± 2.4 (80) | N.A. | 0.5 ± 0.2 (80) | N.A. |

| AG-10/22 | Cl | O-CH3 | 0.013 ± 0.003 (140) | 0.11 ± 0.03 (130) | 0.0002 ± 0.0001 (130) | 0.05 ± 0.02 (115) |

N.A., nonactive compound (cell activation was <30% of control level over a concentration range of 0–40 μM).

*Location of the chiral center.

Compounds that induced Ca2+ mobilization in human neutrophils and HL-60 cells transfected with FPR1, FPR2, or FPR3 are shown in Tables 2 to 5 (chemical names for most potent compounds are indicated in the Table 6 legend), whereas nonactive compounds are listed in Supplemental Table S1. Nonactive compounds induced no Ca2+ flux or had very low efficacy (<25% of the response induced by positive control peptide) in human neutrophils. Our screening demonstrated that 3 Trp-based analogs, 10 Phe-based analogs, and 9 other analogs were agonists for human neutrophils and FPR-transfected HL-60 cells. In general, the active analogs also exhibited high efficacy, although a couple of exceptions were present (see Tables 2–5). Among the most potent in human neutrophils, compounds AG-10/16 and AG-10/22 had EC50 values in the low nanomolar range (EC50 ∼60 and 13 nM, respectively) and very high efficacy (>100%). When evaluated in HL-60 cells, most of the 22 compounds were mixed FPR1/FPR2 agonists, although many displayed much higher selectivity for either FPR1 or FPR2, as demonstrated by comparing the EC50 values at FPR1 with EC50 values at FPR2 for each agonist (see Tables 2–4). Twenty-one compounds had nanomolar EC50 values in FPR2-HL-60 cells and four compounds had nanomolar EC50 values in FPR1-HL-60 cells (Tables 2–5). Sixteen compounds were also active in FPR3-HL-60 cells, AG-10/8 and AG-10/22 being the most potent (Tables 2–5). N-[1,3-di(benzodioxolan-5-yl)propan-2-yl]-N′-phenylurea and N-[2-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-1-benzylethyl]-N′-phenylurea derivatives displayed the highest selectivity for FPR2 versus FPR1 or FPR3 (Tables 4 and 5), and AG-10/22 had the highest activity at FPR2 among all agonists identified (EC50 ∼ 200 pM with >100% efficacy). In any case, further SAR analysis and biological studies will be needed to determine a role of different substituents in the receptor selectivity of related FPR agonists.

TABLE 6.

Ca2+ mobilization, chemotactic activity, and ROS production in neutrophils treated with selected agonists

The data are presented as the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments with cells from different donors or mice, in which median effective concentration values (EC50) were determined by nonlinear regression analysis of the dose−response curves (five to six points) generated using GraphPad Prism 5 with 95% confidence interval (P < 0.05).

| Compound | EC50 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca2+ Mobilization in Murine Neutrophils | Chemotaxis |

ROS Production in Human Neutrophils | ||

| Human Neutrophils | Murine Neutrophils | |||

| μM | ||||

| PD176252 | 0.2 ± 0.05 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 8.3 ± 1.5 | N.A. |

| PD168368 | 0.1 ± 0.03 | 0.5 ± 0.15 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | N.A. |

| AG-10/1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.004 ± 0.002 | 13.5 ± 4.2 | 0.43 ± 0.2 |

| AG-10/2 | 0.4 ± 0.09 | 0.003 ± 0.001 | 3.4 ± 0.9 | 0.5 ± 0.2 |

| AG-10/3 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.022 ± 0.005 | 10.9 ± 2.1 | 8.0 ± 2.7 |

| AG-10/4 | 3.5 ± 0.7 | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 10.8 ± 1.9 | 4.6 ± 1.3 |

| AG-10/5 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 12.4 ± 2.2 | 4.5 ± 1.2 |

| AG-10/6 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 0.36 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 4.3 ± 1.3 |

| AG-10/7 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.68 ± 0.2 | 12.0 ± 2.6 | 9.3 ± 2.2 |

| AG-10/8 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.002 ± 0.001 | 0.96 ± 1.7 | 18.2 ± 4.3 |

| AG-10/9 | 0.3 ± 0.07 | 0.02 ± 0.005 | 0.056 ± 0.022 | 1.9 ± 0.4 |

| AG-10/10 | 0.2 ± 0.06 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.005 ± 0.002 | 4.2 ± 0.9 |

| AG-10/14 | 10.7 ± 1.9 | 0.65 ± 0.2 | 9.1 ± 1.7 | 1.4 ± 0.4 |

| AG-10/15 | 0.1 ± 0.04 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.16 |

| AG-10/16 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.3 |

| AG-10/17 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.56 ± 0.12 | 0.35 ± 0.08 |

| AG-10/18 | 4.6 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 7.1 ± 1.3 | N.A. |

| AG-10/19 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.90 ± 0.3 | 19.0 ± 4.3 | 2.4 ± 0.6 |

| AG-10/20 | 8.5 ± 1.9 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 5.8 ± 1.7 | 0.8 ± 0.18 |

| AG-10/21 | 4.5 ± 1.4 | 4.3 ± 1.1 | 29.3 ± 6.2 | 1.6 ± 0.4 |

| AG-10/22 | 0.003 ± 0.001 | 0.006 ± 0.002 | 0.18 ± 0.07 | 0.23 ± 0.6 |

| WKYMVm | 0.01 ± 0.005 | 0.002 ± 0.001 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 4.1 ± 0.9 |

| WKYMVM | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 3.5 ± 1.2 | 125 ± 24.5 |

| fMLF | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 0.0005 ± 0.0002 | 14.6 ± 2.7 | 0.04 ± 0.02 |

N.A., nonactive compound (cell activation was <30% of control level over a concentration range of 0–40 μM); AG-10/1, (R/S) 3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2-(3-phenylureido)propanamide); AG-10/2, (S)-ethyl 1-(2-(3-(4-bromophenyl)ureido)-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)propanoyl)piperidine-4-carboxylate; AG-10/3, (S)-4-(2-(3-(4-bromophenyl)ureido)-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)propanoyl)-N-ethyl-2-methylpiperazine-1-carboxamide; AG-10/4, (S)-1-(4-bromophenyl)-3-(1-oxo-3-phenyl-1-(pyrrolidin-1-yl) propan-2-yl)urea; AG-10/5, (S)-1-(4-bromophenyl)-3-(1-oxo-3-phenyl-1-(piperidin-1-yl)propan-2-yl)urea; AG-10/6, (S)-1-(4-chlorophenyl)-3-(1-oxo-3-phenyl-1-(piperidin-1-yl)propan-2-yl)urea; AG-10/7, (S)-1-(4-(methylthio)phenyl)-3-(1-oxo-3-phenyl-1-(piperidin-1-yl)propan-2-yl)urea; AG-10/8, (S)-2-(3-(4-bromophenyl)ureido)-N-(2-oxoazepan-3-yl)-3-phenylpropanamide; AG-10/9, (S)-ethyl 1-(2-(3-(4-bromophenyl)ureido)-3-phenylpropanoyl)piperidine-3-carboxylate; AG-10/10, (S)-ethyl 1-(2-(3-(4-bromophenyl)ureido)-3-phenylpropanoyl)piperidine-4-carboxylate; AG-10/14, N-2-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-1-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-ylmethyl)ethyl]-N′-phenylurea; AG-10/15, N-2-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-1-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-ylmethyl)ethyl]-N′-(4-fluorophenyl)urea; AG-10/16, N-2-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-1-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-ylmethyl)ethyl]-N′-(4-chlorophenyl)urea; AG-10/17, N-2-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-1-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-ylmethyl)ethyl]-N′-(4-bromophenyl)urea; AG-10/20, (R/S) N-2-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-1-(4-fluorobenzyl)ethyl]-N′-(4- fluorophenyl)urea; AG-10/22, (R/S) N-2-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-1-(4-methoxybenzyl)ethyl]-N′-(4-chlorophenyl)urea].

Effect of Active Compounds on Neutrophil Functional Responses.

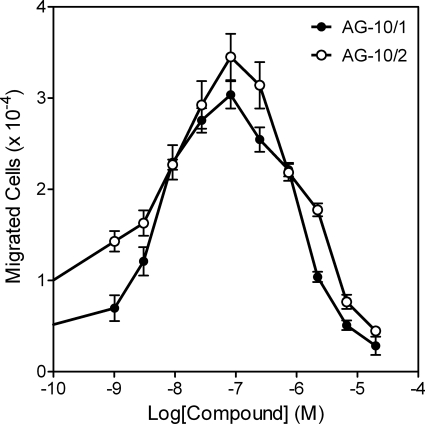

Compounds that activated Ca2+ mobilization in human neutrophils and transfected HL-60 cells also activated Ca2+ flux in murine neutrophils (Table 6). As with human neutrophils, AG-10/22 was the most potent agonist for murine neutrophils (EC50 ∼3 nM). The selected compounds were also chemoattractants for murine and human neutrophils (Table 6), and representative bell-shaped dose response curves are shown in Fig. 2 for human neutrophil chemotactic responses. Similar response curves were found with murine neutrophils (data not shown). The most potent chemotactic compounds for murine and human neutrophils were AG-10/10 and AG-10/22, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Stimulation of human neutrophil migration by selected compounds. Human neutrophil chemotaxis toward the indicated concentrations of AG-10/1 and AG-10/2 was determined, as described under Materials and Methods. The data are presented as the mean ± S.D. of triplicate samples from one experiment that is representative of three independent experiments.

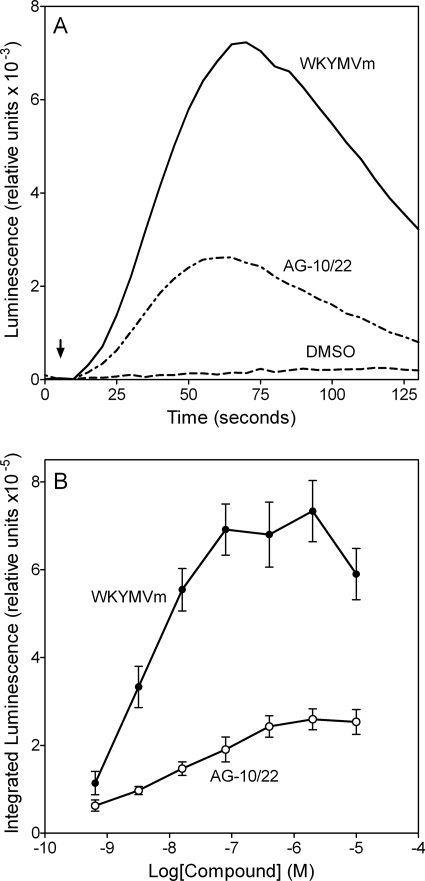

FPR agonists identified in the Ca2+ mobilization screening were evaluated for their ability to activate human neutrophil ROS production in comparison with chemoattractant peptides fMLF and WKYMVm. Both peptides induced ROS production with a very similar time course and a peak of activity at ∼1 min (Fig. 3A), which is comparable with data from previous reports (Karlsson et al., 2006; Thorén et al., 2010). Analysis of the ability of selected FPR agonists (Table 6) to activate ROS production in human neutrophils showed that these compounds stimulated ROS production with kinetic curves similar to the chemoattractant peptides, but with a lower amplitude. As an example, kinetics of ROS production is shown for AG-10/22 in Fig. 3A. We found that most of the lead FPR agonists dose-dependently stimulated ROS production, with EC50 values in the nanomolar or low micromolar ranges (Fig. 3B, Table 6). It is noteworthy that PD168368 and PD176252 were classified as nonactive compounds for stimulating ROS production, because their efficacy was <30% of background level.

Fig. 3.

ROS production by human neutrophils treated with WKYMVm or AG-10/22. A, kinetic curves of ROS production induced by 100 nM WKYMVm or 100 nM AG-10/22. Arrow indicates time of treatment addition. B, integrated luminescence (120 s) induced in human neutrophils plotted against the compound concentration. The data are presented as the mean ± S.D. of triplicate samples. A representative experiment from three independent experiments is shown in each panel.

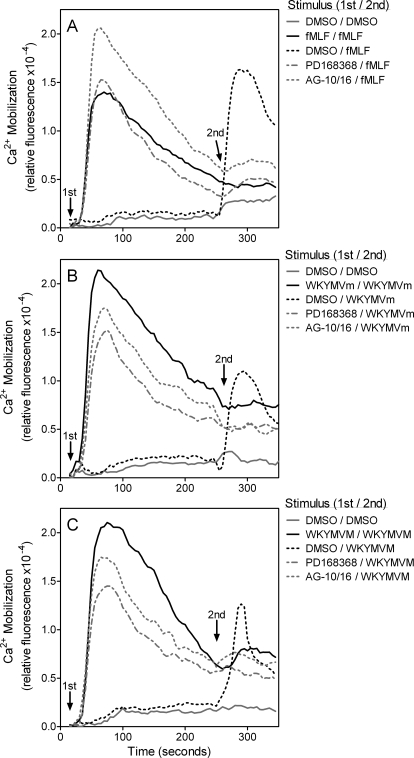

We also examined whether fMLF, WKYMVm, or WKYMVM pretreatment desensitized the neutrophil response to selected compounds, including PD168368, AG-10/5, AG-10/8, AG-10/16, and AG-10/22, and vice versa. We found that pretreatment with the selected compounds (or peptides) markedly attenuated Ca2+ mobilization induced by the peptides or selected compounds, respectively. As examples, kinetic traces of Ca2+ flux desensitization are shown for PD168368 and AG-10/16 in Fig. 4. These data further demonstrate that the selected compounds are FPR agonists and can desensitize FPR to subsequent stimulation.

Fig. 4.

Desensitization of Ca2+ mobilization in human neutrophils by selected FPR agonists. Human neutrophils were loaded with Fluo-4AM dye and pretreated with vehicle (DMSO), PD168368 (10 μM), AG-10/16 (100 nM), 5 nM fMLF (A), 5 nM WKYMVm (B), or 5 nM WKYMVM (C), and Ca2+ mobilization was monitored. The same wells were then treated with one of peptides (in 5 nM concentrations) as indicated, and Ca2+ mobilization was monitored after this second treatment. In each panel, the data are from representative experiments from three independent experiments.

Structure-Activity Relationship Analysis of Selected FPR Agonists.

The active FPR agonists with Trp/Phe-based scaffolds contained a variety of R2 substituents, which ranged from a relatively small N-pyrrolidine (AG-10/4) to a bulky 6,7-dimethoxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-isoquinoline (AG-10/13). Note, however, that modification of the R2 substituent did affect agonist selectivity and/or potency. For example, comparison of our previously reported N-phenethyl-N′-phenylurea FPR2-specific agonists (Kirpotina et al., 2010) with the Trp/Phe-based FPR agonists and their related analogs identified here demonstrated that introduction of additional heterocycle-containing groups to the carbon atom in the α-position to the carbamide fragment increased potency at FPR2 but led to loss of specificity. Likewise, introduction of an ethyl acetate group into the meta position of the N-piperidine ring increased agonist activity (compare AG-10/5 and AG-10/9), but shifting of the ethyl acetate group from the meta to the para position resulted in decrease FPR2 activity and loss of FPR1 and FPR3 activity (compare AG-10/9 and AG-10/10).

Most potent agonists with EC50 values in the nanomolar range contained a halogen atom in the para position of the N′-phenylurea moiety. Although the presence of the halogen atom was not absolutely essential for FPR activity, its absence did result in decreased activity. For example, substitution of para-Br or para-Cl with an S-Me group (compare AG-10/5 or AG-10/6 with AG-10/7) or a Me group (compare AG-10/16 or AG-10/17 with AG-10/18) led to decreased activity in human neutrophils and FPR-transfected HL-60 cells. In addition, moving the halogen atom from the para position to the meta (AG-10/76 and AG-10/95) or ortho (AG-10/83 and AG-10/89) positions resulted in complete loss of activity at all FPRs. This finding is similar to previous studies showing that shift of a halogen atom in the phenyl group of the N′-phenylurea moiety from the para position to the meta or ortho positions resulted in loss of FPR agonist activity (Bürli et al., 2006; Kirpotina et al., 2010).

All active FPR agonists (Tables 2–5) were S-enantiomers or racemic mixtures of R- and S-enantiomers. We did not have pairs of compounds with distinct enantiomeric configurations in our synthetic library, and further synthesis and analysis will be needed to verify whether a specific configuration is preferred for any given molecule.

Pharmacophore Modeling of Ligand Recognition.

We previously applied a ligand-based approach to molecular modeling of FPR2 (Kirpotina et al., 2010) that used field point methods (Cheeseright et al., 2006, 2007). To revise and expand this model, we selected five agonists with known enantiomeric configurations, different heterocyclic fragments, and relatively high selectivity for FPR2 in comparison with FPR1/FPR3 (>100-fold more active for FPR2, making them essentially specific for FPR2). In comparison with previously described FPR2 agonists (Kirpotina et al., 2010), these compounds bear additional heterocycle-containing groups at the carbon atom in the α-position to the carbamide fragment (see Tables 2 and 3). The selected agonists included: PD168368, AG-10/5, AG-10/8, AG-10/17, and Frohn-11 (Frohn et al., 2007). This chiral compound was used to increase diversity of scaffolds used for building the template.

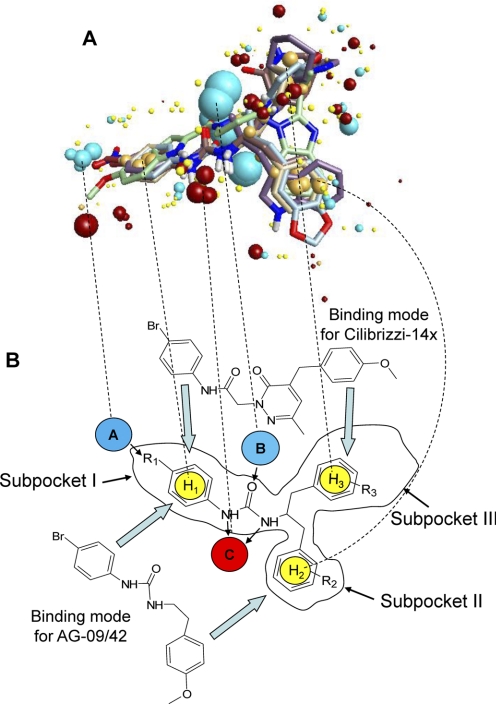

Using the conformer hunt algorithm (FieldTemplater ver. 2.0.1), we generated up to 200 independent conformations lying within 6 kcal/mol energy gap above the lowest-energy geometry for each of the molecules. Field point patterns were calculated for these conformations, and the clique algorithm of FieldTemplater was applied to obtain the best alignment for this group of five agonists. Analysis of all conformations of the five compounds led to the construction of three five-molecule templates very similar to each other in molecular geometry and quality of overlays, providing evidence that a stable solution was obtained by the FieldTemplater program. The best template, shown in Fig. 5A, was taken for further investigation. A schematic representation of the template and three hypothetical hydrophobic subpockets are shown in Fig. 7. Furthermore, relative locations of substituents inside the different subpockets are indicated in Table 7.

Fig. 5.

Multimolecule template for FPR2 and alignments of two molecules on the template. A, the multimolecule template was created using the best conformations of the following five molecules: AG-10/5, AG-10/8, AG-10/17, PD168368, and Frohn-11. Field points are colored as follows: blue, electron-rich (negative); red, electron-deficient (positive); yellow, van der Waals attractive (steric); and orange, hydrophobic. B, alignments for Cilibrizzi-14x and AG-09/42 in the template represent examples of two different modes of ligand-receptor interaction with the three hypothetical receptor subpockets I, II, and III. Arrows indicate directions of alignments for AG-09/42 in subpockets I/II and for Cilibrizzi-14x in subpockets I/III. Negative field points (blue spheres A and B) correspond to the receptor's positively charged regions (e.g., amino and hydroxyl groups in the active site that are capable of forming hydrogen bonds with electronegative atoms of the agonist). Positive field points (red sphere C) correspond to the receptor's negatively charged regions or to hydrogen bond acceptors in the FPR2 active site. Spheres H1, H2, and H3 correspond to hydrophobic centers. Substituents R1, R2, and R3 may influence lipophilicity, molar refraction, and atomic charges for respective groups of particular FPR2 agonists. Dashed lines show correspondences between centers of the main field points on the multimolecule template (A) and their schematic representations in B.

TABLE 7.

Location in hypothetical hydrophobic subpockets of substituents from representative conformations obtained for the 5-molecule FPR2 template and alignments on this template of previously reported FPR agonists

| Compound | Subpocket |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | |

| Template | |||

| AG-10/8 | 4-Bromophenyl | Benzyl | 2-Oxoazepan-3-yl |

| PD168368 | 4-Nitrophenyl | 3-indolyl | 1-(2-Pyridyl)-1-cyclohexyl |

| Frohn-11 | 5-Methoxy-indole | Benzimidazol-1-yl | Ethyl |

| AG-10/5 | 4-Bromophenyl | Benzyl | 1-Piperidyl |

| AG-10/17 | 4-Bromophenyl | 1,3-Benzodioxol-5-yl | 1,3-Benzodioxol-5-yl |

| Alignment | |||

| Cilibrizzi-14x | 4-Bromophenyl | Methyl | 4-Methoxybenzyl |

| Bürli-25 | 4-Bromophenyl | Methyl oriented to subpocket II | Phenyl |

| AG-09/3 | 4-Bromophenyl | 4-Fluorophenyl | |

| AG-09/4 | 4-Bromophenyl | 3-Chlorophenyl | |

| AG-09/5 | 4-Chlorophenyl | 2-Nitrophenyl located between subpockets II and III; nitro group oriented to subpocket II | |

| AG-09/6 | 4-Methoxyphenyl | 2-Thienyl | |

| AG-09/8 | 4-Nitrophenyl | Fused benzene ring | 4-Methoxyphenyl |

| AG-09/9 | 4-Methoxyphenyl | Thiazolidin-4-one-3-yl | Fused benzene ring |

| AG-09/10 | 4-Methoxyphenyl | 1-Piperidyl | |

| AG-09/42 | 4-Bromophenyl | 4-Methoxyphenyl | |

One of the notable features of the template is the good overlap of phenylurea fragments in compounds PD168368, AG-10/5, AG-10/8, and AG-10/17. Electron-withdrawing substituents in the para position of phenyl ring produce a group of blue points where an electropositive area of the receptor could be located. In the centers of the superimposed phenylurea benzene rings, orange field points reflect the hydrophobic nature of the benzene fragments (Fig. 5A). Thus, it is reasonable to suggest the presence of a hydrophobic pocket (subpocket I) with positively charged groups in the binding site of FPR2. Another pocket with hydrophobic character (subpocket II) corresponds to the overlapping benzyl substituents of molecules AG-10/5 and AG-10/8. This location also coincides with the fused benzene rings of indole, benzodioxolane, and benzimidazole fragments in compounds PD168368, AG-10/17, and Frohn-11, respectively. An additional subpocket III of the proposed FPR2 agonist-binding site is occupied by piperidine, azepinone, and (2-pyridyl)cyclohexyl groups of molecules AG-10/5, AG-10/8, and PD168368, as well as by the second benzodioxolane heterocycle of AG-10/17. Although hydrophobic points dominate in the center of this area, one being produced by the ethyl side chain of Frohn-11, a cloud of blue and red field points is present in the vicinity of subpocket III. These points may correspond to groups responsible for hydrogen bonding and/or electrostatic interactions between the receptor and ligand heteroatoms. Finally, noticeable groups of blue and red field points are seen near the overlapping carbonyl and NH groups, respectively (Fig. 5A). It is very likely that corresponding areas of the receptor participate in hydrogen bond formation with ligands.

Additional specific FPR2 agonists Bürli-25, Cilibrizzi-14x, AG-09/3, AG-09/4, AG-09/5, AG-09/6, AG-09/8, AG-09/9, and mixed FPR1/FPR2 agonists AG-09/10, and AG-09/42 were overlaid on the 5-molecule template of FPR2. The main steps (conformational searches, field point generation, finding preliminary overlays by clique matching, and their subsequent simplex optimization) were performed by built-in modules of FieldAlign software (see Materials and Methods). It should be noted that conformations of the same molecule produce various overlays onto the template that differ in similarity score. The highest-score superimpositions are shown in Table 7. As examples, overlaid molecules occupying subpockets I and II (AG-09/42) or subpockets I and III (Cilibrizzi-14x) are shown in Fig. 5B. The above-mentioned modes of superimposition were found for at least three overlays with high similarity scores for each molecule.

A reasonable way to analyze the results obtained is to identify which of the fragments of overlaid molecules occupies each of the three subpockets (Table 7). Subpocket I is always occupied by the terminal phenyl ring of N-phenylurea (N-phenylthiourea) or N-phenylamide (Bürli-25, Cilibrizzi-14x, AG-09/1, AG-09/3, AG-09/4, AG-09/6, AG-09/9, AG-09/10, and AG-09/42). For AG-09/5 and AG-09/8, the benzene ring of a substituted benzoyl is located in subpocket I (Fig. 7B). Most FPR agonists overlaid in a two-subpocket mode. In addition to subpocket I, the second occupied region was either subpocket II (AG-09/1, AG-09/3, AG-09/4, AG-09/6, and AG-09/42) or subpocket III (Bürli-25 and AG-09/10). For AG-09/5, the nitro-substituted phenyl ring was located between subpockets II and III and coincided with the 5-membered imidazole ring of Frohn-11 within the template. Cilibrizzi-14x, AG-09/8, and AG-09/9 were overlaid in a three-pocket mode (Table 7).

Discussion

FPRs have been implicated in the control of many inflammatory processes, promoting the recruitment and infiltration of phagocytes to sites of inflammation (for review, see Ye et al., 2009), as well as resolving inflammation (Dufton and Perretti, 2010). However, the expression pattern of FPRs, especially that of FPR2, in nonphagocytic cells suggests that these receptors participate in functions other than innate immunity and may represent unique targets for therapeutic drug design. Because of the homology between GPCRs, it has been suggested and demonstrated that some of GPCR ligands thought previously to be “specific” may actually be recognized by unrelated GPCRs (Herold et al., 2003). Thus, screening heterologous GPCRs, in our case FPRs, with such ligands has the potential to identify novel agonist activity and potential leads for new therapeutics. Indeed, we screened a small library of 32 relatively low-molecular-weight ligands (agonists and antagonists) of 24 different GPCRs and used SAR analysis to identify a number of novel and potent FPR agonists.

Screening of the GPCR ligands resulted in the discovery of CCK-1 receptor agonist A-71623 and bombesin-related BB1/BB2 receptor antagonists PD168368 and PD176252 as FPR agonists. It should be noted that all three of these ligands contain Trp and an N-phenylurea moiety. Trp was also present in the structures of other compounds that we screened (e.g., somatostatin sst2 receptor agonist L-054,264 and tachykinin NK1 receptor antagonist L-732,138); however, both these ligands were inactive. Nevertheless, three of the five Trp-based GPCR ligands among all 32 compounds tested were FPR agonists. This represents a hit frequency of ∼10%, which is much higher than that observed when screening a random collection of compound structures (∼ 0.1%) (Edwards et al., 2005). Thus, the presence of both Trp and N-phenylurea aromatic fragments in the structure of peptide/peptoid GPCR ligands could be considered a “risk factor” for cross-activity in relation to FPRs. Indeed, further screening of 97 PD176252/PD168368 analogs revealed 22 additional FPR agonists, some with very high potency and high efficacy.

Note that EC50 values for the selected agonists in human neutrophils followed the same trend but were generally higher than those observed in FPR-transfected HL-60 cells. This is not surprising because of the differences in complexity between undifferentiated HL-60 cells and mature neutrophils (for review, see Birnie, 1988). Undifferentiated HL-60 cells lack many receptors, including endogenous FPR1 (Prossnitz et al., 1993), and other phagocyte functional responses, such as NADPH oxidase activity (Levy et al., 1990). In addition, Prossnitz et al. (1993) proposed that primary myeloid cells maintain a subpopulation of FPR in a low-affinity, possibly G protein-free state, which is not a feature of FPR-transfected HL-60 cells. Thus, their work indicates that the environment in which FPRs are expressed plays an important role in the nature or amplitude of subsequent FPR-mediated responses, and confirmation of these responses in primary myeloid cells is essential. Clearly, further work is important to evaluate the role of cellular complexity, G protein availability, and levels of individual FPR expression in modulating the relative amplitude of FPR-mediated responses in transfected cell lines versus primary phagocytes.

Although CCK receptor agonists can modulate leukocyte functions, including activation of Ca2+ mobilization in JURKAT T lymphocytic cells and monocyte chemotaxis (Sacerdote et al., 1988; Lignon et al., 1993; Carrasco et al., 1997), this is the first report that CKK-1 receptor agonist A-71623 can activate Ca2+ mobilization in cells via FPRs. Agonistic activity of A-71623 in HL-60 cells transfected with FPR1/FPR2 can be related to the specific structure of this CCK-1 receptor agonist, which resembles structures of PD168368 and PD176252 [i.e., three aromatic fragments, including a Trp moiety, emerging from the same carbon atom in the α-position (Fig. 1A)].

To date, several BB1/BB2 antagonists have been reported, including 2-[3-(2, 6-diisopropyl-phenyl)-ureido]3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-2-methyl-N-(1-pyridin-2-yl-cyclohexylmethyl)-proprionate (PD165929), PD168368, and PD176252 (Eden et al., 1996; Ryan et al., 1999). These compounds are known as peptoids and represent nonpeptide ligands that were designed based on the chemical structure of the mammalian neuropeptide (Horwell, 1995). PD168368 has high affinity for BB1, a 30- to 60-fold lower affinity for BB2, and a >300-fold lower affinity for BB3 and BB4 (Ryan et al., 1999), whereas PD176252 has nanomolar affinity for both BB1 and BB2 (Ashwood et al., 1998; Moody et al., 2003). On the other hand, cross-activity of these BB1/BB2 antagonists for other GPCRs has not been reported. Given the potent effects of PD176252 and PD168368 at FPR1 and FPR2, our results indicate that these compounds are in fact not selective BB1/BB2 ligands. Note, however, that all other BB1/BB2 ligands tested were inactive, indicating that human neutrophils do not express functional BB1/BB2 receptors, as has been suggested previously (Djanani and Kähler, 2002). Thus, our results show that FPR agonist activity is due to specific structural features of PD168368 and PD176252. Indeed, further SAR analysis of PD168368 and PD176252 analogs identified several additional FPR agonists with EC50 values in the low nanomolar range, and these potent FPR agonists activated a number of phagocyte functional responses.

PD168368 and PD176252 have been used to study the role of BB1/BB2 in physiological and pathological processes. For example, PD176252 inhibited the growth of lung cancer and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells, potentiated the growth inhibitory effects of histone deacetylase inhibitors, inhibited Ca2+ flux in gastrin-releasing peptide/bombesin-stimulated lung cancer cells, and stimulated cell growth (Moody et al., 2000, 2006; Zhang et al., 2007a). Likewise, PD168368 inhibited NMB-stimulated cellular signaling and inhibited NMB-induced proliferation of rat C6 glioblastoma cells and NCI-H1299 lung cancer cells (Ryan et al., 1999; Moody et al., 2000). Here, we demonstrate that PD168368 and PD176252 and their analogs can also activate a number of host defense functions in human and murine neutrophils. Thus, the effects of the BB1/BB2 antagonists PD168368 and PD176252 on experimental animals or in vitro/ex vivo systems with a high content of phagocytic cells should be re-evaluated to consider the potential innate immune enhancing effects of these compounds via FPR activation.

Pharmacophore modeling represents a rational approach for optimization of candidate small-molecule receptor ligands and screening for bioactive ligand conformations (Wolber et al., 2008). Through field point analysis of the relatively specific FPR2 agonists identified here, we were able to revise our previously published pharmacophore model of FPR2 agonists (Kirpotina et al., 2010). The revised model suggests the existence of three hydrophobic/aromatic subpockets and several binding poses of FPR2 agonists onto these subpockets. This is not surprising, because analysis of different agonists binding to the β2-adrenergic receptor predicted different poses with various sets of optimal interaction inside of the local binding site (Katritch et al., 2009). Our pharmacophore model has similarities with the proposed interaction mode between the tetrapeptide WNleYM and FPR2 (Wan et al., 2007). However, because of the high flexibility of this peptide molecule, alignment of WNleYM conformations on our current FPR2 pharmacophore model could not be solved by the field point approach. Consequently, FPR2 agonists with three aromatic fragments linked to the same carbon atom in the α-position may achieve an optimal binding arrangement and trigger more conformational changes within the FPR2 transmembrane region, compared with the previously described dumbbell-shaped FPR2 agonists (see compounds used here for alignments on the template; Table 7).

Although our pharmacophore model represents a ligand-based view of the active site for FPR2, identification of the actual amino acid residues that comprise the ligand-binding site is complicated by the lack of crystallographic, site-directed mutagenesis, and cross-linking data. On the other hand, the similarity between GPCR ligands could reflect a similarity between their binding sites (Gloriam et al., 2009). Thus, because amino acids (in particular Tyr-220) in transmembrane region 5 (TM-5) of the neuromedin receptor (BB1) play a major role in PD168368 binding (Tokita et al., 2001), it can be hypothesized that the binding site for PD168368, PD176252, and analogs may lie in the TM-5 region of FPR2. Indeed, the amino sequence 201RGIIR205 is conserved in TM-5 of most species variants for both FPR1 and FPR2 (Alvarez et al., 1996), and site-directed mutagenesis supports the role of residues Arg-201 and Arg-205 in positioning fMLF in the FPR1-binding pocket (Mills et al., 2000). Although bombesin-related receptors and FPRs are phylogenetically quite far from each other in the human rhodopsin receptor family (Gloriam et al., 2009), it seems that conserved residues in these GPCRs results in ligand promiscuity among unrelated receptor targets.

In summary, we have identified a class of compounds, including bombesin BB1/BB2 antagonists PD176252 and PD168368, that are potent FPR1 and FPR2 agonists. Indeed, AG-10/16 and AG-10/22 represent the most potent nonpeptide FPR2 agonists reported to date. Thus, because of their potency and high efficacy, PD168368 and PD176252 and their analogs represent important leads for therapeutic development in regulating FPR function, and these compounds can serve as scaffolds for the development of novel, potent, and selective FPR2 agonists. On the other hand, the previously reported effects of these compounds that have been attributed solely to activity as BB1/BB2 antagonists, such as effects on animal behavior (Merali et al., 2006) and cell proliferation (Moody et al., 2000, 2003) should also be reevaluated for contributions of FPR.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Marie-Josèphe Rabiet and Francois Boulet (Commissariat à l'Energie atomique, Direction des Sciences du Vivant, Institut de Recherches en Technologies et Sciences pour le Vivant, Laboratoire Biochimie et Biophysique des Systèmes Intégrés, Grenoble, France) for kindly providing FPR-transfected HL-60 cells.

The online version of this article (available at http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org) contains supplemental material.

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health National Center for Research Resources [Grant P20-RR020185]; by the National Institutes of Health [Contract HHSN266200400009C]; the M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust; and the Montana State University Agricultural Experimental Station.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/mol.110.068288.

- fMLF

- N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenyalanine

- FPR

- formyl peptide receptor

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- SAR

- structure-activity relationship

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- L-012

- 8-amino-5-chloro-7-phenylpyridol[3,4-d]pyridazine-1,4(2H,3H)-dione

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- WKYMVm

- Trp-Lys-Tyr-Met-Val-d-Met

- HBSS

- Hanks' balanced salt solution

- HBSS+

- Hanks' balanced salt solution containing 1.3 mM CaCl2 and 1.0 mM MgSO4

- AM

- acetoxymethyl ester

- MPO

- myeloperoxidase

- CCK

- cholecystokinin

- TM

- transmembrane

- PD168368

- (S)-a-methyl-a-[[[(4-nitrophenyl)amino]carbonyl]amino]-N-[[1-(2-pyridinyl) cyclohexyl]methyl]-1H-indole-3-propanamide

- PD176252

- (S)-N-[[1-(5-methoxy-2-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]-a-methyl-a-[[-(4-nitrophenyl)amino]carbonyl]amino-1H-indole-3-propanamide

- A-71623

- Boc-Trp-Lys(ε-N-2-methylphenylaminocarbonyl)-Asp-(N-methyl)-Phe-NH2

- NNC 63-0532

- (8-naphthalen-1-ylmethyl-4-oxo-1-phenyl-1,3,8-triaza-spiro(4.5)-dec-3-yl)acetic acid methyl ester

- SR 27897

- 1-((2-(4-(2-chlorophenyl)thiazol-2-yl)aminocarbonyl)indolyl)acetic acid

- YM 022

- 1-(2,3-dihydro-1-(2′-methylphenacyl)-2-oxo-5-phenyl-1H-1,4-benzodiazepin-3-yl)-3-(3-methylphenyl)urea

- LY 288513

- 1-(4-bromophenylaminocarbonyl)-4,5-diphenyl-3-pyrazolidinone

- BML-190

- indomethacin morpholinylamide

- AM 630

- iodopravadoline

- GW 405833

- 1-(2,3-dichlorobenzoyl)-5-methoxy-2-methyl-3-[2-(4-morpholinyl)ethyl]-1H-indole

- S 25585

- 1-benzoyl-2-[[trans-4-[[[[2-nitro-4-trifluoromethyl)phenyl]sulfonyl]amino]methyl]cyclohexyl]carbonyl]hydrazine

- SR 49059

- relcovaptan

- AC 55541

- (2E)-2-[1-(3-bromo-phenyl)ethylidene] α-(benzoylamino)-3,4-dihydro-4-oxo-1-phthalazineacetic acid hydrazide

- JTE 013

- 1-[1,3-dimethyl-4-(2-methylethyl)-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridin-6-yl]-4-(3,5-dichloro-4-pyridinyl)-semicarbazide

- RF9

- adamantylcarbonyl-arginyl-phenylalaninamide

- SR 142948

- 2-[[[5-(2,6-dimethoxyphenyl)-1-[4- [[[3-(dimethylamino)propyl]methylamino]carbonyl]-2-(1-methylethyl)phenyl]-1H-pyrazol-3-yl]carbonyl]amino]-tricyclo[3.3.1.13,7]decane-2-carboxylic acid

- FR 139317

- N-(N-(N-((hexahydro-1H-azepin-1-yl)carbonyl)-l-leucyl)-1-methyl-d-tryptophyl)-3-(2-pyridinyl)-d-alanine

- ONO 1078

- pranlukast

- L-692,585

- 3-[[(2R)-2-hydroxypropyl]amino]-3-methyl-N-[(3R)-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-2-oxo-1-[[2′-(1H-tetrazol-5-yl)[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl]methyl]-1H-1-benzazepin-3-yl]-butanamide

- T 98475

- 7-[(2,6-difluorophenyl)methyl]-4,7-dihydro-2-[4-[(2-methyl-1-oxopropyl)amino]phenyl]-3-[[methyl(phenylmethyl)amino]methyl]-4-oxo-thieno[2,3-b]pyridine-5-carboxylic acid 1-methylethyl ester

- L-371,257

- 1-(1-(4-((N-acetyl-4-piperidinyl)oxy)-2-methoxybenzoyl)piperidin-4-yl)-4H-3,1-benzoxazin-2(1H)-one

- FK 888

- N(2)-(4-hydroxy-1-(1-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)carbonyl-l-prolyl)-N-methyl-N-phenylmethyl-3-(2-naphthyl)-l-alaninamide

- SDZ NKT 343

- 2-nitrophenylcarbamoyl-(S)-prolyl-(S)-3-(2-naphthyl)alanyl-N-benzyl-N-methylamide

- L-732,138

- N-acetyl-l-tryptophan 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)benzyl ester

- WEB 2086

- apafant

- L-161,982

- N-[[4′-[[3-butyl-1,5-dihydro-5-oxo-1-[2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-4H-1,2,4-triazol-4-yl]methyl][1,1′-biphenyl]-2-yl]sulfonyl]-3-methyl-2-thiophenecarboxamide

- L-054,264

- 2-((spiro(1H-indene-1,4′-piperidin)-1′-ylcarbonyl)amino)-N-(3-aminomethyl-1-cyclohexylmethyl)-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)propanamide

- BIM 187

- 1-de(5-oxo-l-proline)-2-de-l-valine-3-d-phenylalanine-10-l-leucine-11-l-leucinamide-ranatensin

- BIM 189

- 1-de(5-oxo-l-proline)-2-de-l-valine-3-d-phenylalanine-10-l-leucine-11-(4-chloro-l-phenylalaninamide)-ranatensin

- BIM 23042

- d-Nal-Cys-Tyr-d-Trp-Lys-Val-Cys-Nal-NH2

- BIM 23127

- d-Nal-Cys-Tyr-d-Trp-Orn-Val-Cys-Nal-NH2

- ICI 216,140

- N-isobutyryl-His-Trp-Ala-Val-d-Ala-His-Leu-NHMe

- PD165929

- 2-[3-(2, 6-diisopropyl-phenyl)-ureido]3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-2-methyl-N-(1-pyridin-2-yl-cyclohexylmethyl)-proprionate

- Frohn-11

- 1-((5-methoxyindol-2-yl)carbonyl)-3-(2-ethylbenzimidazol-1-yl)(3R)pyrrolidine

- Bürli-25

- N-(4-bromophenyl)-N-(1,5-dimethyl-3-oxo-2-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)urea

- Cilibrizzi-14x

- N-(4-bromophenyl)-2-[5-(4-methoxybenzyl)-3-methyl-6-oxo-6H-pyridazin-1-yl]-acetamide

- NCGC00168126–01

- N-(4-(5-(3-(furan-2-ylmethyl)-4-oxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinazolin-2-yl)-2-methoxybenzyloxy)phenyl acetamide.

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Schepetkin, Khlebnikov, Jutila, and Quinn.

Conducted experiments: Schepetkin, Kirpotina, and Khlebnikov.

Performed data analysis: Schepetkin, Kirpotina, Khlebnikov, and Quinn.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Schepetkin, Khlebnikov, Jutila, and Quinn.

Other: Quinn and Jutila acquired funding for the research.

References

- Alvarez V, Coto E, Setién F, González-Roces S, López-Larrea C. (1996) Molecular evolution of the N-formyl peptide and C5a receptors in non-human primates. Immunogenetics 44:446–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashwood V, Brownhill V, Higginbottom M, Horwell DC, Hughes J, Lewthwaite RA, McKnight AT, Pinnock RD, Pritchard MC, Suman-Chauhan N, et al. (1998) PD176252—the first high affinity non-peptide gastrin-releasing peptide (BB2) receptor antagonist. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 8:2589–2594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae YS, Lee HY, Jo EJ, Kim JI, Kang HK, Ye RD, Kwak JY, Ryu SH. (2004) Identification of peptides that antagonize formyl peptide receptor-like 1-mediated signaling. J Immunol 173:607–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae YS, Park JC, He R, Ye RD, Kwak JY, Suh PG, Ho Ryu S. (2003a) Differential signaling of formyl peptide receptor-like 1 by Trp-Lys-Tyr-Met-Val-Met-CONH2 or lipoxin A4 in human neutrophils. Mol Pharmacol 64:721–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae YS, Yi HJ, Lee HY, Jo EJ, Kim JI, Lee TG, Ye RD, Kwak JY, Ryu SH. (2003b) Differential activation of formyl peptide receptor-like 1 by peptide ligands. J Immunol 171:6807–6813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnie GD. (1988) The HL60 cell line: a model system for studying human myeloid cell differentiation. Br J Cancer Suppl 9:41–45 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bürli RW, Xu H, Zou X, Muller K, Golden J, Frohn M, Adlam M, Plant MH, Wong M, McElvain M, et al. (2006) Potent hFPRL1 (ALXR) agonists as potential anti-inflammatory agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 16:3713–3718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco M, Del Rio M, Hernanz A, De la Fuente M. (1997) Inhibition of human neutrophil functions by sulfated and nonsulfated cholecystokinin octapeptides. Peptides 18:415–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavicchioni G, Fraulini A, Falzarano S, Spisani S. (2006) Structure-activity relationship of for-L-Met L-Leu-L-Phe-OMe analogues in human neutrophils. Bioorg Chem 34:298–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseright T, Mackey M, Rose S, Vinter A. (2006) Molecular field extrema as descriptors of biological activity: definition and validation. J Chem Inf Model 46:665–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseright T, Mackey M, Rose S, Vinter A. (2007) Molecular field technology applied to virtual screening and finding the bioactive conformation. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2:131–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Yang D, Shen W, Dong HF, Wang JM, Oppenheim JJ, Howard MZ. (2000) Characterization of chenodeoxycholic acid as an endogenous antagonist of the G-coupled formyl peptide receptors. Inflamm Res 49:744–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christophe T, Karlsson A, Rabiet MJ, Boulay F, Dahlgren C. (2002) Phagocyte activation by Trp-Lys-Tyr-Met-Val-Met, acting through FPRL1/LXA4R, is not affected by lipoxin A4. Scand J Immunol 56:470–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cilibrizzi A, Quinn MT, Kirpotina LN, Schepetkin IA, Holderness J, Ye RD, Rabiet MJ, Biancalani C, Cesari N, Graziano A, et al. (2009) 6-Methyl-2,4-disubstituted pyridazin-3(2H)-ones: a novel class of small-molecule agonists for formyl peptide receptors. J Med Chem 52:5044–5057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daiber A, August M, Baldus S, Wendt M, Oelze M, Sydow K, Kleschyov AL, Munzel T. (2004) Measurement of NAD(P)H oxidase-derived superoxide with the luminol analogue L-012. Free Radic Biol Med 36:101–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djanani AM, Kähler ChM. (2002) Modulation of inflammation by vasoactive intestinal peptide and bombesin: lack of effects on neutrophil apoptosis. Acta Med Austriaca 29:93–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufton N, Perretti M. (2010) Therapeutic anti-inflammatory potential of formyl-peptide receptor agonists. Pharmacol Ther 127:175–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eden JM, Hall MD, Higginbottom M, Horwell DC, Howson W, Hughes J, Jordan RE, Lewthwaite RA, Martin K, McKnight AT, et al. (1996) PD165929—the first high affinity non-peptide neuromedin-B (NMB) receptor selective antagonist. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 6:2617–2622 [Google Scholar]

- Edwards BS, Bologa C, Young SM, Balakin KV, Prossnitz ER, Savchuck NP, Sklar LA, Oprea TI. (2005) Integration of virtual screening with high-throughput flow cytometry to identify novel small molecule formylpeptide receptor antagonists. Mol Pharmacol 68:1301–1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksson R, Lagerström MC, Lundin LG, Schiöth HB. (2003) The G-protein-coupled receptors in the human genome form five main families. Phylogenetic analysis, paralogon groups, and fingerprints. Mol Pharmacol 63:1256–1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohn M, Xu H, Zou X, Chang C, McElvaine M, Plant MH, Wong M, Tagari P, Hungate R, Bürli RW. (2007) New ‘chemical probes’ to examine the role of the hFPRL1 (or ALXR) receptor in inflammation. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 17:6633–6637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavins FN. (2010) Are formyl peptide receptors novel targets for therapeutic intervention in ischaemia-reperfusion injury? Trends Pharmacol Sci 31:266–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloriam DE, Foord SM, Blaney FE, Garland SL. (2009) Definition of the G protein-coupled receptor transmembrane bundle binding pocket and calculation of receptor similarities for drug design. J Med Chem 52:4429–4442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herold CL, Behm DJ, Buckley PT, Foley JJ, Wixted WE, Sarau HM, Douglas SA. (2003) The neuromedin B receptor antagonist, BIM-23127, is a potent antagonist at human and rat urotensin-II receptors. Br J Pharmacol 139:203–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwell DC. (1995) The ‘peptoid’ approach to the design of non-peptide, small molecule agonists and antagonists of neuropeptides. Trends Biotechnol 13:132–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson J, Fu H, Boulay F, Bylund J, Dahlgren C. (2006) The peptide Trp-Lys-Tyr-Met-Val-D-Met activates neutrophils through the formyl peptide receptor only when signaling through the formylpeptide receptor like 1 is blocked. A receptor switch with implications for signal transduction studies with inhibitors and receptor antagonists. Biochem Pharmacol 71:1488–1496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]