Abstract

Objectives

With the ultimate goal of improving the quality of care provided to aging women with overactive bladder, we sought to better understand aging women’s experience with overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms and the care they receive.

Methods

Women seen in outpatient female urology clinics were identified by ICD-9 codes for OAB and recruited. Patients with painful bladder syndrome, mixed stress and urge incontinence, prolapse, or recent pelvic surgery were excluded. Patient focus groups were conducted by trained non-clinician moderators incorporating topics related to patients’ perceptions of OAB physiology, symptoms, diagnostic evaluation, treatments, and outcomes. Qualitative data analysis was performed using grounded theory methodology.

Results

Five focus groups totaling 33 women with OAB were conducted. Average patient age was 67 years (range 39–91). Older women with OAB lacked knowledge about the physiology of their disease and had poor understanding regarding the rationale for many diagnostic tests, including urodynamics and cystoscopy. The results of diagnostic studies often were not understood by older patients. Many women were dissatisfied with the care they had received. This lack of knowledge and understanding was more apparent among the elderly women in the group.

Conclusions

Findings demonstrated a poor understanding of the physiology of overactive bladder and the rationale for various diagnostic modalities and treatments. This was associated with dissatisfaction with care. There is a need for better communication with older women experiencing OAB symptoms about the physiology of the condition.

Keywords: Focus groups, qualitative research, aging, urinary incontinence, grounded theory

INTRODUCTION

Overactive bladder (OAB) is defined by the International Continence Society as urinary urgency, with or without urge urinary incontinence, usually with frequency and nocturia.1 According to the National Overactive Bladder Evaluation Program (NOBLE), the prevalence of OAB is 16.9% among women. Both the prevalence and severity of OAB has been found to increase with age.2 The impact of aging on voiding function has not been clearly elucidated. However, several epidemiologic studies have found strong associations between age and lower urinary tract dysfunction. This correlates with the fact that many patients and providers believe that lower urinary tract symptoms are the result of normal aging.3, 4 Concomitant disease processes, polypharmacy, and physical and mental impairment often complicate the interpretation of age-related changes in urinary tract function, and several studies have shown that age is not an independent risk factor for voiding dysfunction.5 It is possible that OAB may have a greater impact on quality of life among aging women due to these confounding processes. Such factors may affect their ability to engage in effective communication with their provider, and thus prevent them from achieving a maximal benefit from the diagnosis and treatment of OAB. Furthermore, it seems logical that poor understanding of disease physiology and treatment strategies would produce poor compliance with treatment.

Despite the rising prevalence of OAB with age, little is known about how aging women perceive the etiology and physiology of OAB and the rationale for various diagnostic modalities and treatments they receive from their providers. With the ultimate goal of improving the quality of care provided to aging women with OAB, the intent of this study was to better understand older women’s experience with the care they received by conducting patient focus groups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Qualitative research is quite different methodologically from most studies assessing the impact of OAB on quality of life. Unlike quantitative research methodology, qualitative methodology typically does not test a hypothesis, but rather searches for a theory implicit in the data. Due to the paucity of information regarding patient perspectives and OAB, a research method was sought that would facilitate exploration of ideas and create a foundation for future research. Focus groups were chosen because they permit a discussion of many topics, while allowing for extrapolation when interesting points or ideas are introduced. These focus groups were conducted to better understand older women’s experience with the care they receive.

After obtaining approval from the UCLA institutional review board, recruitment commenced for patients from the female urology specialty clinics in the Department of Urology. Potential subjects seen over a two-year period were first selected based on International Classifications of Diseases (9th edition, ICD- 9) codes for OAB-related symptoms over a two-year period (Appendix 1). Records were then reviewed to confirm a diagnosis of OAB and for exclusion criteria, which included pelvic organ prolapse (greater than or equal to stage two), painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis, pelvic pain, mixed urinary incontinence, as well as anti-incontinence or other pelvic surgery within the last year. Potential subjects were also excluded if they did not speak English, were younger than age 21, were unable to ambulate (and therefore unlikely to achieve significant symptom improvement), or had dementia prohibiting effective focus group participation.

Women were recruited with both OAB-wet symptoms (frequency and urgency accompanied by urge urinary incontinence) and OAB-dry symptoms (frequency and urgency without urge urinary incontinence). After files were screened, participants were recruited by telephone and asked them to participate in a 90-minute focus group session. Participants were provided with a small honorarium for their time.

Focus groups were conducted with trained female non-clinician moderators using a standardized open-ended script for 1.5-hour sessions. Focus groups were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. The topics covered in the focus groups encompassed women’s perceptions of OAB symptoms, their etiology and pathophysiology, as well as their experiences with diagnosis, evaluation, treatment, and outcomes of care. Topics for the focus group were developed through reviews of the literature and validated questionnaires. The same topical guide was used for each focus group.

Grounded theory methodology, as illustrated by Charmaz, was used to analyze the data.6 Grounded theory methodology is a qualitative research methodology that allows the researcher to identify key issues by coding and identifying categories.6 Briefly, this includes initial line-by-line coding of transcripts utilizing key phrases in the participant’s own words. This is followed by a grouping together of similarly coded phrases into preliminary themes. Preliminary themes are then grouped together to develop categories, from which core categories, or emergent concepts, are derived. Four investigators separately performed line-by-line coding. Preliminary themes were then compared and merged.

RESULTS

Thirty-three women with OAB symptoms were recruited and enrolled to form five focus groups. Mean age was 67 years (range 39–91 years), and median age was 69 years. The patient population was primarily older, with 1/3 of participants less than age 65 and 2/3 greater than or equal to age 65. Median age in the younger group was 59 years and median age in the older group was 73 years. The majority of women were non-Hispanic Caucasians. There was a wide range in the severity of OAB symptoms as well as the treatments that the women had experienced. Qualitative data analysis was utilized to extract key phrases that emerged from each focus group. Trends and repetitive themes were noted among the patient population. Six preliminary themes related to OAB in the aging population were extracted during data analysis (Table 1). The preliminary themes fell into two main categories; 1) there were frequent misconceptions among patients and, 2) there was often poor communication between the physician and the patient.

Table 1.

Preliminary themes derived from line by line coding and grouping of similarly coded phrases; illustrative patient quotes for each preliminary theme.

| Six Preliminary Themes | Quotes to Illustrate the Preliminary Themes | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Lack of Understanding of Etiology of OAB |

“I just thought it was a process of getting older and you can’t do anything for it, I have been a frequent urinator and I kind of just accepted it, like this is my plight in life.” |

| 2. | Confusion with other Pelvic Disorders |

“My bladder fell and they had to tie it up.” |

| 3. | Lack of Understanding of Diagnostic Tests |

“They put me on a table and turned me upside down.” “The doctor stuck a wand in my bladder.” |

| 4. | Misconceptions of Definitions of Incontinence |

Nocturnal enuresis: If the sheets of the bed are not wet, they didn’t “wet the bed.” |

| 5. | Miscommunication between patients and providers over Kegel exercises |

When asked how to perform them: “Well you just squeeze as hard as you can all the way up to the mid area. Just squeeze down there to make the muscles firm.” |

| 6. | Miscommunication between patients and providers over medications |

“I was taking the pills, but then I stopped it because it didn’t make the leakage go away.” |

Category 1 Themes: Misconceptions

The first theme preliminary theme identified was a lack of understanding over the etiology of OAB. Patients believed OAB was a natural part of aging and therefore something they must just accept. To illustrate how the process of primary coding was performed, examples of patient quotes from which these themes were derived are included in Table 1. The second theme identified was the confusion of OAB with other pelvic disorders. When asked to describe their experience with OAB, patients described a multitude of pelvic floor disorders, including prolapse, urinary tract infections, stress urinary incontinence, and painful bladder syndrome. When asked about the onset of their OAB symptoms, one woman reported the following: “I blamed my hysterectomy, I say [my gynecologist] did something to my bladder”.

The third preliminary theme identified was a lack of understanding of diagnostic tests, specifically urodynamics and cystocopy. Participants lacked understanding about what was happening to their bodies during these studies. They also lacked information about what useful information these studies would provide. Participants often expected a potential therapeutic outcome from undergoing these diagnostic studies. The fourth theme identified was misconceptions over the definitions of incontinence. Some Participants believed that if they wore an incontinence pad, then they did not have an incontinent episode if their leakage was contained in the pad. In fact, all women initially denied bedwetting, but on further questioning, the majority leaked into a diaper at night.

Category 2 Themes: Miscommunication

Miscommunication between participants and providers regarding Kegel exercises, specifically the instruction and feedback, was also identified. When asked who taught them Kegel exercises, one patient reported: “I learned from friends.” Prior to seeing a specialist, very few participants had been examined while performing the exercises to determine whether they were doing the exercises correctly. Another miscommunication between participants and providers occurred over medications, specifically with respect to unrealistic expectations of cure and side effects. Patients interpreted the prescription from their physician as a cure for their problem, something they took for a short time then discontinued after things were “fixed.” Furthermore, side effects, rarely understood by participants, often led to discontinuation. “You get to the point where all of a sudden you can’t say the next word; your mouth is so dry it won’t move. I was scared.”

Emergent Concepts

From the preliminary themes arose three emergent concepts. First, the women were, dissatisfied with their treatment outcomes. “First you go to the doctor for advice and if that doesn’t work you start playing doctor yourself doing what you think should be done. I mean what can you do?” Second, it is clear that women have expectations that exceed what current state of the art medical care can provide, (i.e. the unrealistic expectation that a course of drug therapy can cure OAB). They need to learn from their providers what to realistically expect from behavioral modification, medications and kegel exercises. Third, more effective communication is needed to optimize patients’ understanding, expectations, satisfaction and, ultimately, outcomes.

COMMENT

Through focus groups composed of primarily older women with OAB, aspects of care that matter most to patients were sought by identifying their experiences with the evaluation and management of the overactive bladder symptom syndrome. Several misconceptions about OAB were found. Older women lacked understanding about the cause of their OAB symptoms. There was a belief that their symptoms were a normal part of aging that they had to tolerate. Such attitudes were also found in other qualitative work done two decades ago,7 as well as in more recent work.8, 9 Diokno et al. found that in over half of the 757 women administered a bladder survey, bladder symptoms were thought to be an inevitable consequence of aging.8 A small subset surveyed in their study also participated in focus group dialogs; a greater lack of understanding was similarly identified among the older women.

Unrealistic expectations, including that bladder symptoms could be cured with medication alone, were identified among the women. These women had not been counseled adequately, or did not understand, that OAB is a chronic condition that requires the patient to be an active participant in her care. Additionally, patients were referred to specialists without a discussion of the importance of behavioral modification and pelvic floor exercises, in addition to medication. These unrealistic expectations were likely endorsed by the direct to consumer drug advertising that make it seem like OAB is easily treated with pills alone.

Qualitative focus group data provides information that cannot be obtained by quantitative measures and validated questionnaires. Quantitative data measures, such as volume voided, are intuitively known to have little to do patient satisfaction. The difficulty with interpretation of questionnaire data is that patients may not truly understand the vocabulary of the question. Furthermore, many questionnaires do not elicit what matters most to the patient, and therefore miss critical information. This lack of understanding comes out in the focus group setting, where women are asked open-ended questions and have the opportunity to ask follow-up questions.

Poor communication between older patients and providers may contribute to the dissatisfaction with care identified in this study. Prior studies have suggested a link between the quality of physician-patient communication and patient health outcomes including emotional health, symptom resolution, functional and physiologic status, and pain control.10 Further work has found that providing information, or education, during the medical visit resulted in greater patient satisfaction and improved patient compliance with care.11 In the treatment of quality-of-life conditions such as OAB, the importance of communication cannot be understated. Greater understanding may result in improved QOL and greater satisfaction with care, two of the more important outcome measures in OAB treatment.12

Effective patient communication can be challenging, as the demands on the health care system heighten and providers are extended to see a greater number of patients in a given period of time. This can be especially challenging in the elderly population, where functional and cognitive limitations may further impede valuable patient-physician interactions. However, improving communication with aging women with OAB can likely be achieved through relatively simple measures. First, in order to minimize lack of understanding due to memory impairment, written materials will allow patients to review what is told to them at their office visits.10 Pamphlets written at appropriate literacy levels that explain the etiology of OAB, as well as the rationale for and description of testing modalities such as urodynamics, will greatly enhance patient understanding. The American Geriatric Society Foundation for Health in Aging has made great strides in providing this type of resource.13 Second, the presence of patients’ children or companions at office visits may also enhance patient understanding and memory.14 Third, development of a “patient-centered” diagnosis and treatment strategy that focuses on the patient’s point of view, attends to their psychosocial needs, and emphasizes the physician-patient partnership can create a greater sense of responsibility for treatment success among patients.11, 15 This level of involvement and autonomy may lead to a greater dedication and positive attitudes toward treatment strategies resulting in improved compliance. Finally, in order to better manage patients’ expectations, physicians must elicit and document their patients’ goals with respect to treatment and understand their conception of a good quality of life.11

Limitations of our study include small sample size and selection of patients from a tertiary care center specialty practice which may not be representative of the generalized OAB population. Data is not available to determine whether this cohort represents patients with more severe symptoms, those who have failed previous treatments or interventions, or patients with greater composite disease burden. Furthermore, no information is available on the educational level of these women which may or may not impact their expectations of care.

CONCLUSIONS

Using grounded theory methodology to analyze focus group dialog, poor understanding among older women with OAB regarding etiology, physiology, and the rationale for various diagnostic modalities and treatments was found. This was associated with dissatisfaction with care. Although memory impairment among older women may affect recall about their experiences with their physicians, there appears to be a need for better communication with women experiencing OAB.

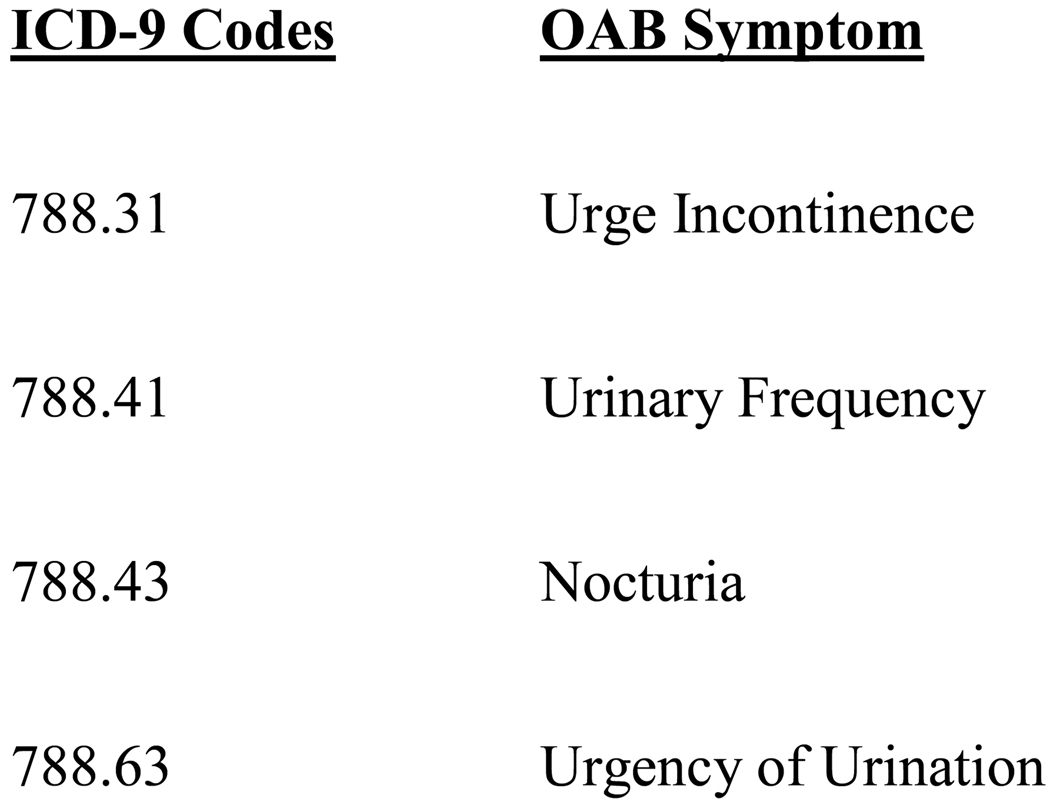

Figure 1.

Selected ICD-9 codes used to identify patients with OAB previously seen in the urology specialty clinics.

Table 2.

Emergent concepts derived from grouping of preliminary themes into categories.

| Emergent Concepts | |

|---|---|

| 1. | Dissatisfaction with Care |

| 2. | Need for Better Management of Patient Expectations |

| 3. | Need for Better Communication with the Aging Population |

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Funding: Supported by the NIDDK (1 K23 DK080227-01, JTA)

Sponsor's Role: None

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions: Study concept and design (ALS, HAN, TXL, AK, SLM, MSL, CAS, SR, LVR, JTA), acquisition of subjects/data (HAN, TXL, SR, LVR, JTA), analysis and interpretation of data (ALS, HAN, TXL SLM, JTA), preparation of manuscript (ALS, HAN, TXL, AK, SLM, MSL, CAS, SR, LVR, JTA).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standarisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167–178. doi: 10.1002/nau.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coyne KS, Zhou Z, Thompson C, et al. The impact on health-related quality of life of stress, urge and mixed urinary incontinence. BJU Int. 2003;92(7):731–735. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, et al. Pelvic Disorders Network. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA. 2008;300(11):1311–1316. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Minassian VA, Stewart WF, Wood GC. Urinary incontinence in women: variation in prevalence estimates and risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(2 Pt 1):324–331. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000267220.48987.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anger JT, Saigal CS, Litwin MS. The prevalence of urinary incontinence among community dwelling adult women: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Urol. 2006;175(2):601–604. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charmaz K. The grounded theory method: an explication and interpretation. In: Emerson RM, editor. Contemporary Filed Research. Boston: Little Brown; 1983. pp. 109–127. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitteness LS. Knowledge and beliefs about urinary incontinence in adulthood and old age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38(3):374–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb03525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diokno AC, Sand PK, Macdiarmid S, et al. Perceptions and behaviours of women with bladder control problems. Fam Pract. 2006;23(5):568–577. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cml018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarkisian CA, Hays RD, Mangione CM. Do older adults expect to age successfully? The association between expectations regarding aging and beliefs regarding healthcare seeking among older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(11):1837–1843. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152(9):1423–1433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams SL, Haskard KB, DiMatteo MR. The therapeutic effects of the physician-older patient relationship: effective communication with vulnerable older patients. Clin Interv Aging. 2007;2(3):453–467. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abrams P, Artibani W, Gajewski JB, et al. Assessment of treatment outcomes in patients with overactive bladder: importance of objective and subjective measures. Urology. 2006;68(2 Supple):17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Geriatric Society. Aging in the Know. [Accessed 1/15/2010]; http://www.healthinaging.org/agingintheknow/topics_trial.asp.

- 14.Greene MG, Adelman RD. Physician-older patient communication about cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;50:55–60. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(03)00081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(7):1087–1110. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]