Abstract

To evaluate the possible role of microtubules in the cellular action of vasopressin on the mammalian kidney, the effects of microtubule-disrupting agents were studied in vivo and in vitro.

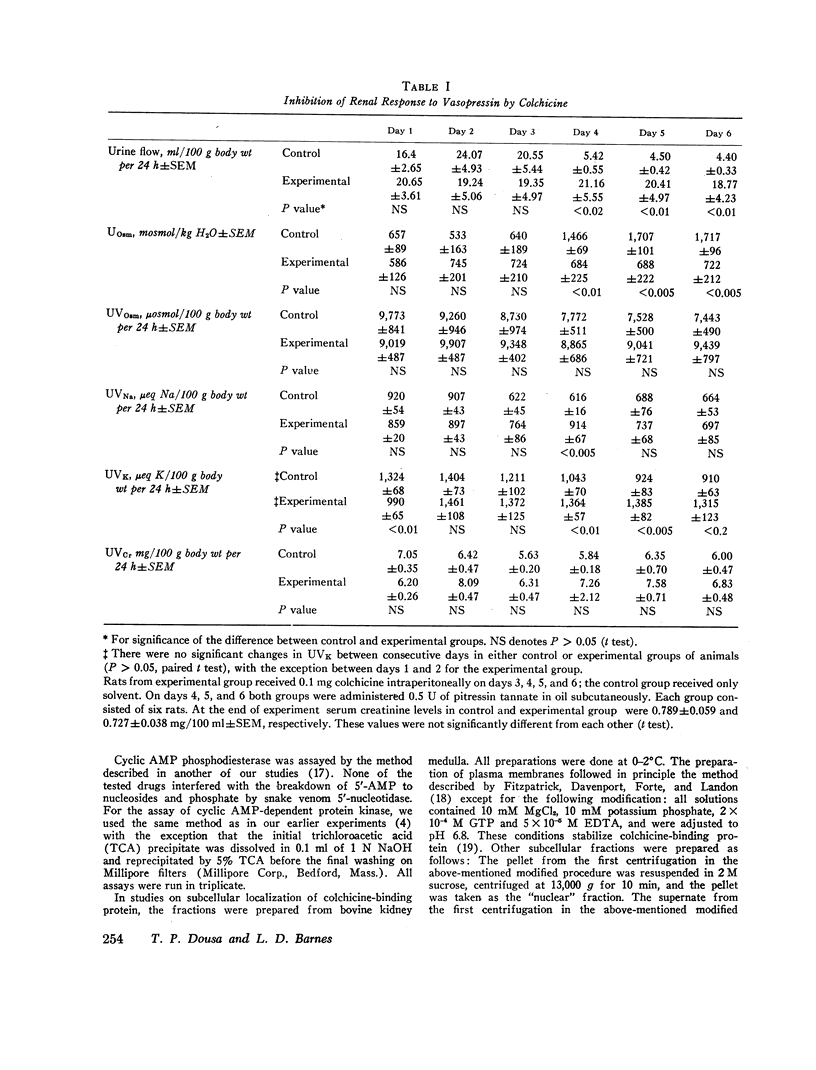

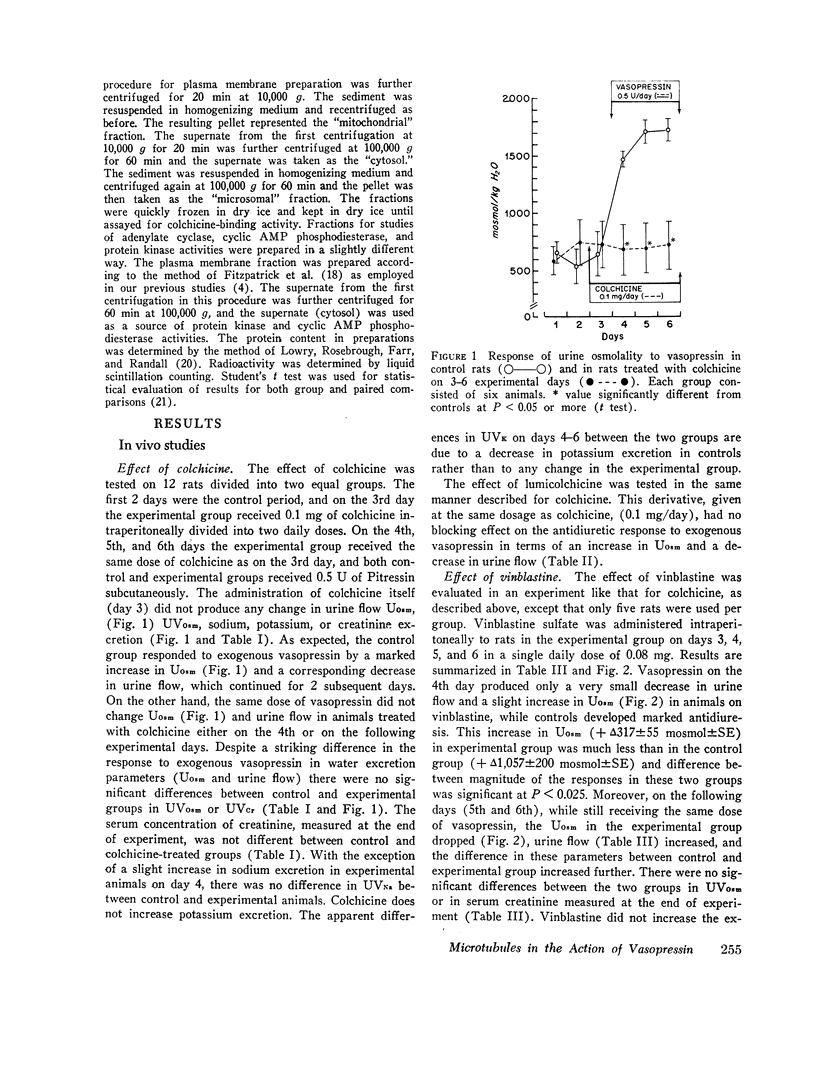

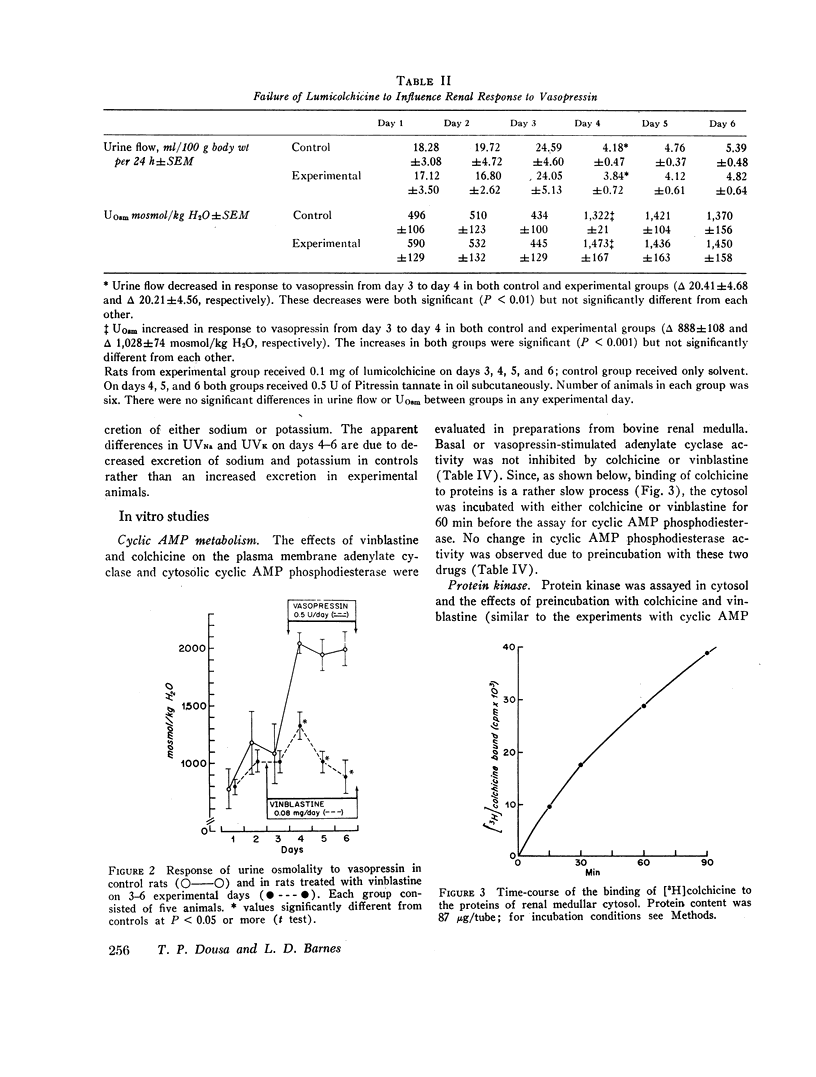

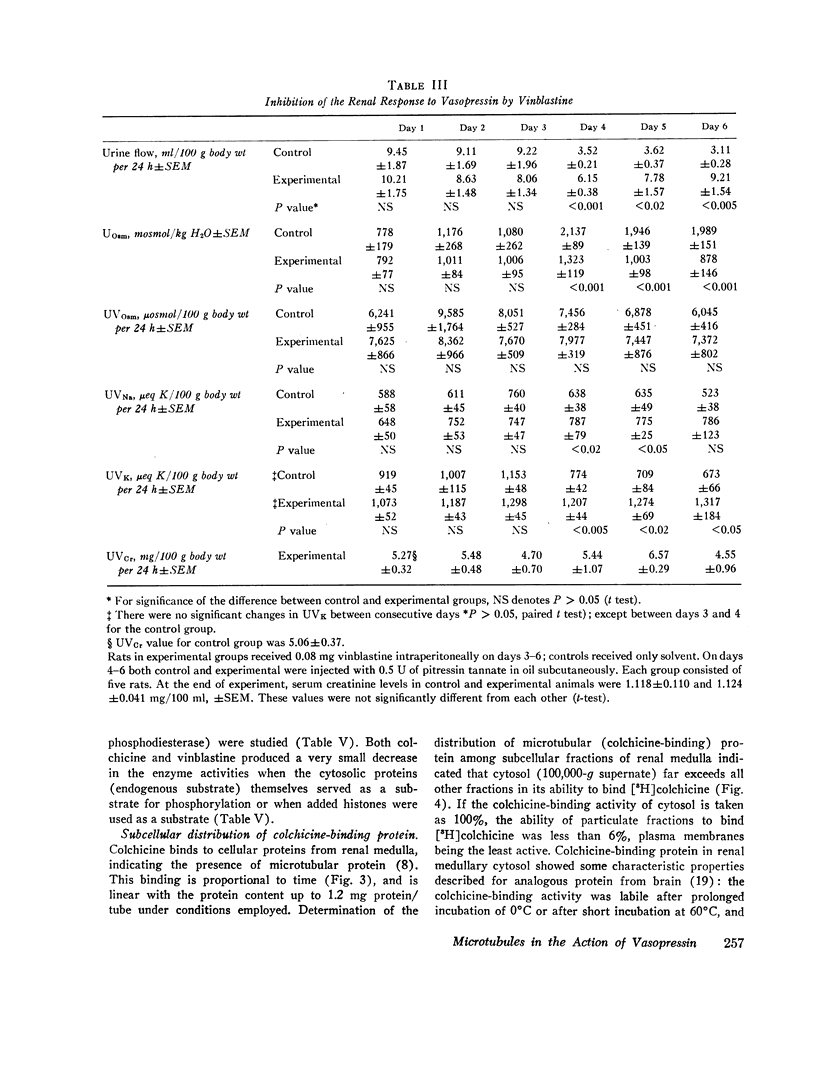

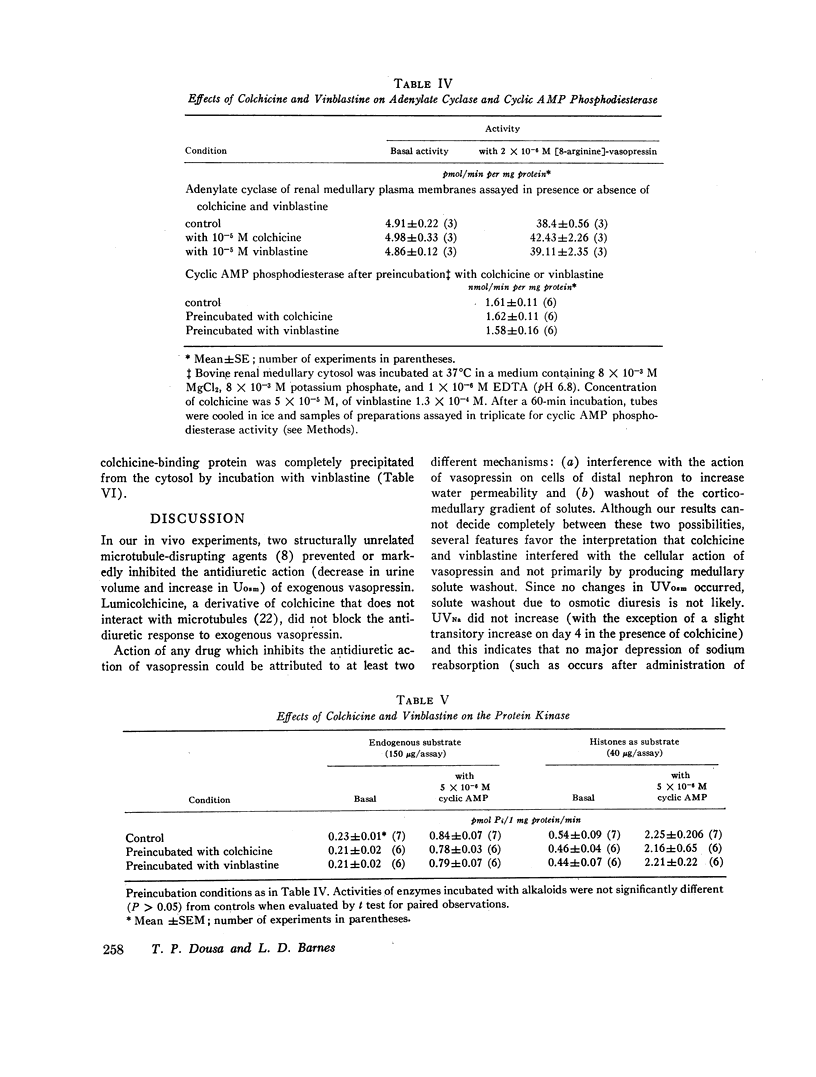

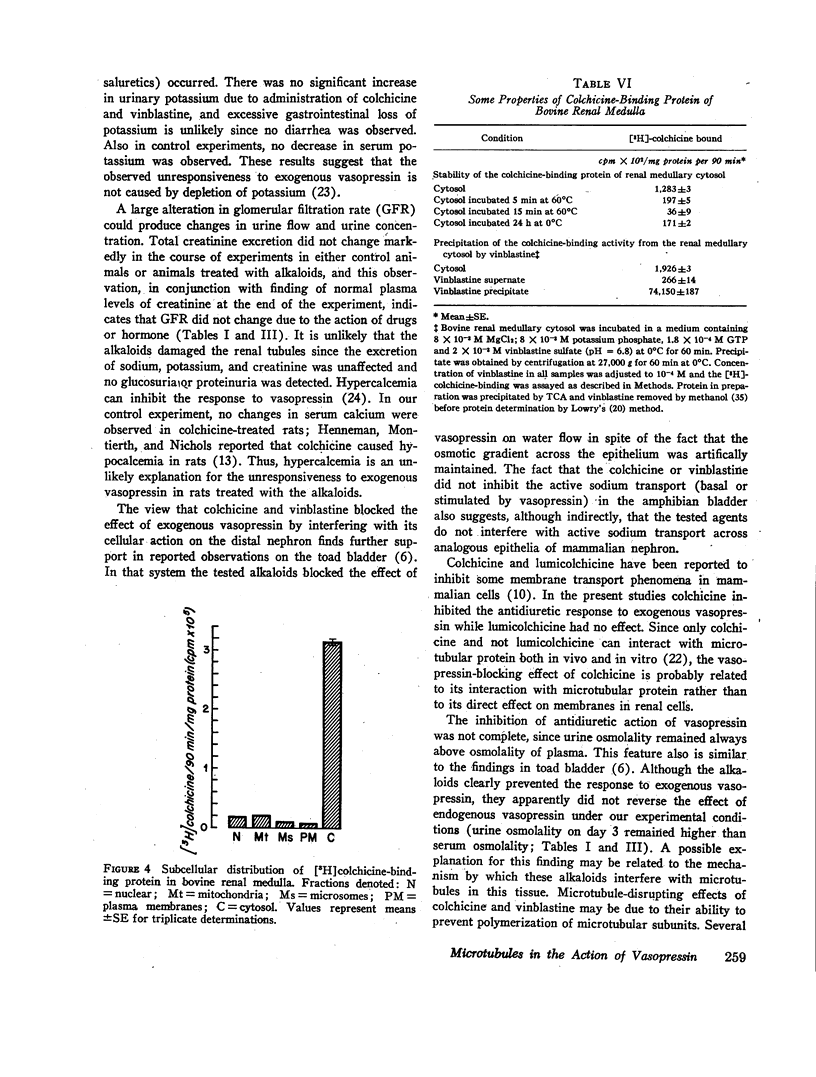

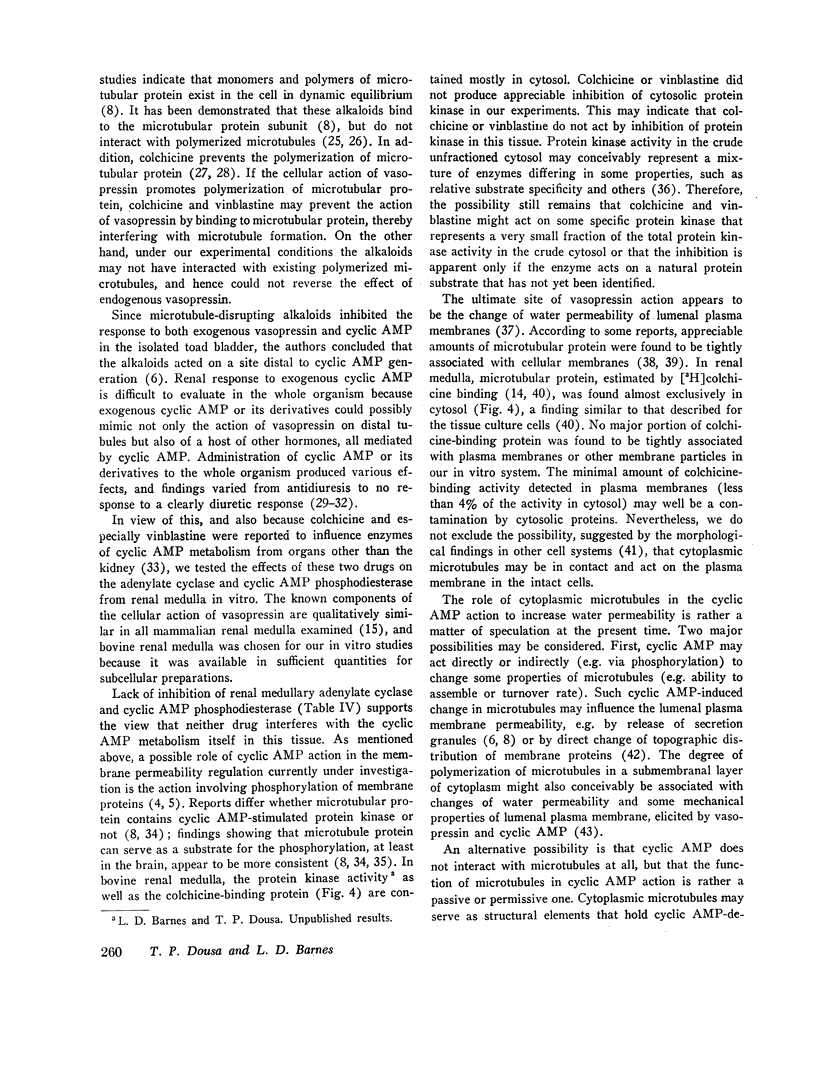

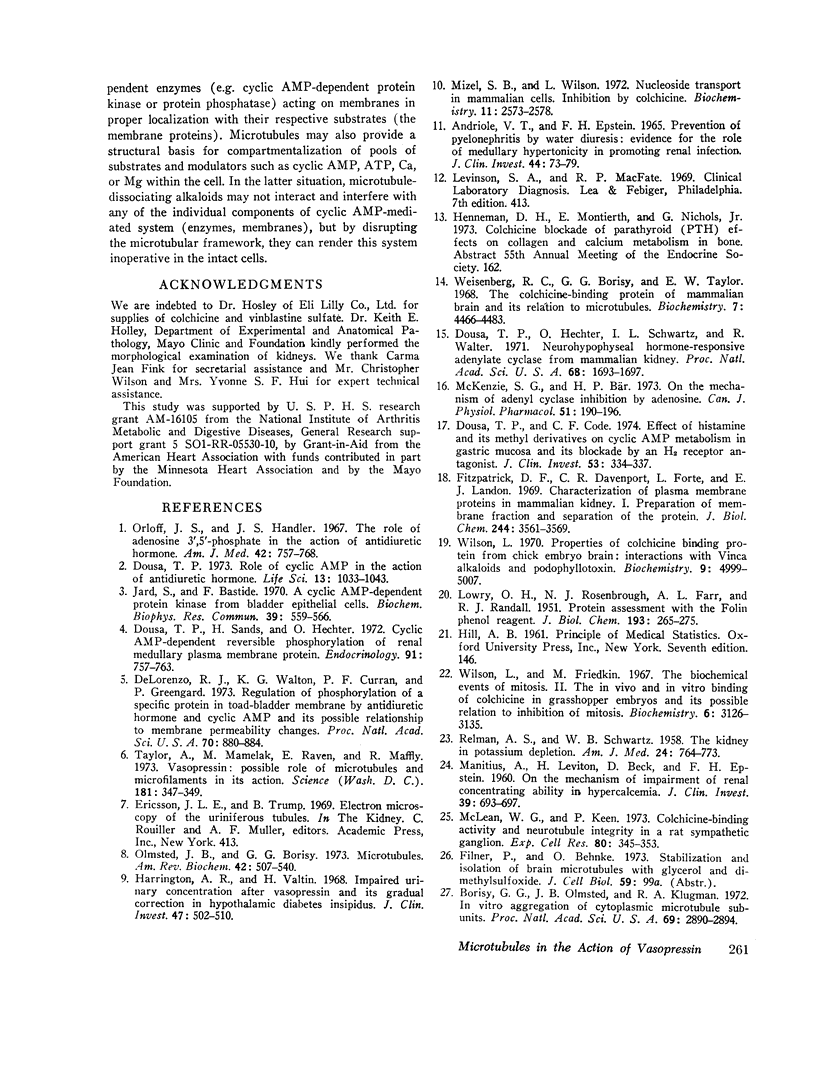

In vivo studies were done in rats in mild to moderate water diuresis induced by drinking 5% glucose. Microtubule-disrupting alkaloids, colchicine (0.1 mg/day) or vinblastine (0.08 mg/day), given intraperitoneally, did not change water and solute excretion itself, but blocked or markedly inhibited the antidiuretic response (increase in urine osmolality and decrease in urine flow) to exogenous vasopressin. Total solute excretion was unaffected by these two alkaloids and there were no substantial changes in excretion of sodium, potassium, or creatinine. Lumicolchicine, a derivative of colchicine that does not interact with microtubules, did not alter the antidiuretic response to exogenous vasopressin. Activities of adenylate cyclase in the renal medullary plasma membrane, and cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase and protein kinase in renal medullary cytosol, were not influenced by 10-5—10-4 M colchicine or vinblastine in vitro. Studies on the subcellular distribution of microtubular protein (assessed as [3H]colchicine-binding protein) in renal medulla shows that this protein is contained predominantly in the cytosol. Particulate fractions, including plasma membrane, contain only a minute amount (less than 6%) of the colchicine-binding activity.

The results suggest that the integrity of cytoplasmic microtubules in cells of the distal nephron is required for the antidiuretic action of vasopressin, probably in the sites distal to cyclic AMP generation in the mammalian kidney.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ANDRIOLE V. T., EPSTEIN F. H. PREVENTION OF PYELONEPHRITIS BY WATER DIURESIS: EVIDENCE FOR THE ROLE OF MEDULLARY HYPERTONICITY IN PROMOTING RENAL INFECTION. J Clin Invest. 1965 Jan;44:73–79. doi: 10.1172/JCI105128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe Y., Morimoto S., Yamamoto K., Ueda J. Effects of dibutyryl cyclic 3',5'-adenosine monophosphate on the renal function. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1968 Jun;18(2):271–272. doi: 10.1254/jjp.18.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borisy G. G., Olmsted J. B., Klugman R. A. In vitro aggregation of cytoplasmic microtubule subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1972 Oct;69(10):2890–2894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.10.2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borisy G. G., Taylor E. W. The mechanism of action of colchicine. Binding of colchincine-3H to cellular protein. J Cell Biol. 1967 Aug;34(2):525–533. doi: 10.1083/jcb.34.2.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLorenzo R. J., Walton K. G., Curran P. F., Greengard P. Regulation of phosphorylation of a specific protein in toad-bladder membrane by antidiuretic hormone and cyclic AMP, and its possible relationship to membrane permeability changes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1973 Mar;70(3):880–884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.3.880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dousa T. P., Code C. F. Effect of histamine and its methyl derivatives on cyclic AMP metabolism in gastric mucosa and its blockade by an H2 receptor antagonist. J Clin Invest. 1974 Jan;53(1):334–337. doi: 10.1172/JCI107555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dousa T. P. Role of cyclic AMP in the action of antidiuretic hormone on kidney. Life Sci. 1973 Oct 16;13(8):1033–1040. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(73)90371-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dousa T. P., Sands H., Hechter O. Cyclic AMP-dependent reversible phosphorylation of renal medullary plasma membrane protein. Endocrinology. 1972 Sep;91(3):757–763. doi: 10.1210/endo-91-3-757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dousa T., Hechter O., Schwartz I. L., Walter R. Neurohypophyseal hormone-responsive adenylate cyclase from mammalian kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971 Aug;68(8):1693–1697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.8.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick D. F., Davenport G. R., Forte L., Landon E. J. Characterization of plasma membrane proteins in mammalian kidney. I. Preparation of a membrane fraction and separation of the protein. J Biol Chem. 1969 Jul 10;244(13):3561–3569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grantham J. J. Mode of water transport in mammalian renal collecting tubules. Fed Proc. 1971 Jan-Feb;30(1):14–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grantham J. J. Vasopressin: effect on deformability of urinary surface of collecting duct cells. Science. 1970 May 29;168(3935):1093–1095. doi: 10.1126/science.168.3935.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington A. R., Valtin H. Impaired urinary concentration after vasopressin and its gradual correction in hypothalamic diabetes insipidus. J Clin Invest. 1968 Mar;47(3):502–510. doi: 10.1172/JCI105746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jard S., Bastide F. A cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase from frog bladder epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1970 May 22;39(4):559–566. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(70)90240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs E. G. Protein kinases. Curr Top Cell Regul. 1972;5:99–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O. H., ROSEBROUGH N. J., FARR A. L., RANDALL R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951 Nov;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagnado J. R., Lyons C., Wickremasinghe G. The subcellular distribution of colchicine-binding protein ('microtubule protein') in rat brain. FEBS Lett. 1971 Jun 24;15(3):254–258. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(71)80324-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine R. A. Antiduretic responses to exogenous adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate in man. Clin Sci. 1968 Apr;34(2):253–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANITIUS A., LEVITIN H., BECK D., EPSTEIN F. H. On the mechanism of impairment of renal concentrating ability in hypercalcemia. J Clin Invest. 1960 Apr;39:693–697. doi: 10.1172/JCI104085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Maldonado M., Eknoyan G., Suki W. N. Natriuretic effects of vasopressin and cyclic AMP: possible site of action in the nephron. Am J Physiol. 1971 Jun;220(6):2013–2020. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1971.220.6.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie S. G., Bär H. P. On the mechanism of adenyl cyclase inhibition by adenosine. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1973 Mar;51(3):190–196. doi: 10.1139/y73-027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean W. G., Keen P. Colchicine-binding activity and neurotubule integrity in a rat sympathetic ganglion. Exp Cell Res. 1973 Aug;80(2):345–353. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(73)90306-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizel S. B., Wilson L. Nucleoside transport in mammalian cells. Inhibition by colchicine. Biochemistry. 1972 Jul 4;11(14):2573–2578. doi: 10.1021/bi00764a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmsted J. B., Borisy G. G. Microtubules. Annu Rev Biochem. 1973;42:507–540. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.42.070173.002451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orloff J., Handler J. The role of adenosine 3',5'-phosphate in the action of antidiuretic hormone. Am J Med. 1967 May;42(5):757–768. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(67)90093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RELMAN A. S., SCHWARTZ W. B. The kidney in potassium depletion. Am J Med. 1958 May;24(5):764–773. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(58)90379-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddington M., Lagnado J. R. The phosphorylation of colchicine-binding ('microtubular') protein in respiring slices of guinea pig cerebral cortex. FEBS Lett. 1973 Mar 1;30(2):188–194. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(73)80649-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelanski M. L., Gaskin F., Cantor C. R. Microtubule assembly in the absence of added nucleotides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1973 Mar;70(3):765–768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.3.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A., Mamelak M., Reaven E., Maffly R. Vasopressin: possible role of microtubules and microfilaments in its action. Science. 1973 Jul 27;181(4097):347–350. doi: 10.1126/science.181.4097.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukena T. E., Berlin R. D. Effect of colchicine and vinblastine on the topographical separation of membrane functions. J Exp Med. 1972 Jul 1;136(1):1–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.136.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisenberg R. C., Borisy G. G., Taylor E. W. The colchicine-binding protein of mammalian brain and its relation to microtubules. Biochemistry. 1968 Dec;7(12):4466–4479. doi: 10.1021/bi00852a043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson L., Friedkin M. The biochemical events of mitosis. II. The in vivo and in vitro binding of colchicine in grasshopper embryos and its possible relation to inhibition of mitosis. Biochemistry. 1967 Oct;6(10):3126–3135. doi: 10.1021/bi00862a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson L. Properties of colchicine binding protein from chick embryo brain. Interactions with vinca alkaloids and podophyllotoxin. Biochemistry. 1970 Dec 8;9(25):4999–5007. doi: 10.1021/bi00827a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]