Abstract

Background:

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is one of the most commonly performed procedures in general surgery. There have been very few reported thoracic complications from this surgical procedure.

Methods:

We report the case of a patient who underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy with gallstone spillage 34 months before presenting to the thoracic surgery service. The patient first complained of streaks of hemoptysis at 6 months from the time of the original procedure. A lower lobe infiltrate was noted and treated successfully with oral antibiotics. Over the next 2 years, the patient's symptoms waxed and waned.

Results:

Due to the chronic infiltrate in his lung, a thoracotomy was performed that revealed erosion of the stone through the right diaphragm with formation of a lung abscess.

Conclusion:

A high index of suspicion for a gallstone-related problem should be entertained by the practitioner when presented with a patient who has a right lung infiltrate and a history of open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Keywords: Cholelithiasis, Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Lung abscess

INTRODUCTION

Gallbladder perforation during laparoscopic cholecystectomy occurs in 10% to 32% of patients, with gallstone spillage in 0.2% to 20% of cases. There have been very few reported thoracic complications from this common problem.1

Before laparoscopic cholecystectomy, cholelithoptysis and intrathoracic complications from gallstones were rare because the operative field was packed off to facilitate the open surgery. Introduction of a pneumoperitoneum and intraoperative irrigation facilitates distant migration of gallstones, specifically to the subphrenic space.

A review of the literature reveals 11 reported cases of gallstones being found in the thoracic cavity following cholecystectomy. Eight cases presented as cholelithoptysis and the latest one as massive hemoptysis from a gallstone associated abscess. We believe these findings reiterate the need for fastidious stone removal at the time of initial cholecystectomy. Furthermore, while most patients with this problem present with cholelithoptysis, a high index of suspicion should be entertained by the practitioner when encountering a patient who has a right lung infiltrate and a history of open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

CASE REPORT

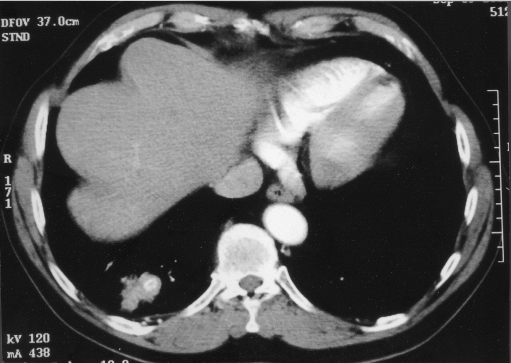

A 73-year-old man with a past medical history of hyper-tension and chronic obstructive lung disease presented with a 4-month history of biliary colic and mild pancreatitis. After 3 days of conservative management with nothing by mouth and intravenous antibiotics, his pancreatitis resolved, and he underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Intraoperatively, there was reported spillage of gallstones, with most being retrieved laparoscopically. He did well postoperatively and was asymptomatic for 6 months until he developed low-grade fevers and streaks of hemoptysis. Computed tomography of the chest revealed a 5×7-cm pulmonary infiltrate in the posterior basilar segment of the right lower lobe associated with a 5×9-mm oval calcification at the level of the right diaphragm (Figure 1). There was no clear radiographic evidence of a subdiaphragmatic abscess. His symptoms were treated successfully with oral antibiotics.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography of the chest shows eccentric calcification of a soft tissue mass in the lower lobe of the right lung.

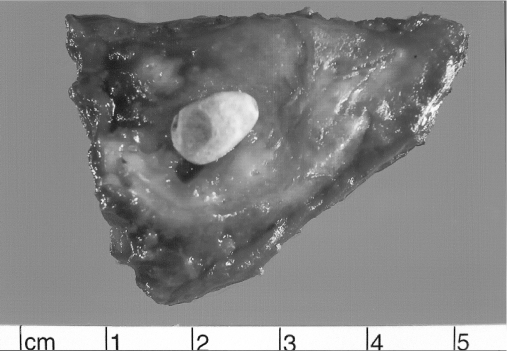

A repeat CT scan 2 months later demonstrated marked improvement of the pulmonary infiltrate, but the persistence of a calcified nodule on the surface of the diaphragm. Over the next 2 years, the patient developed episodic bouts of scant hemoptysis every 2 to 3 months that resolved spontaneously. Thirty-four months after his laparoscopic cholecystectomy, after an episode of self-limited hemoptysis, he underwent a surveillance CT scan that revealed a new 5×3-cm opacity in the posterobasal segment of his right lower lobe. Flexible bronchoscopy showed no endobronchial lesions. A presumptive diagnosis of pneumonia was made, and oral antibiotic therapy was initiated. An interval CT scan 2 months later demonstrated no change in the lesion. He was at this point referred to the thoracic surgery service. Further evaluation with a mediastinoscopy showed no evidence of malignancy. At the time of exploration, the right lower lobe was densely adherent to the diaphragm. To ensure an oncologic resection, a 2-cm section of diaphragm was resected. Frozen section showed no malignancy. The final pathology was returned as chronic pulmonary abscess and foreign body giant cell reaction to a gallstone. (Figure 2). The patient's postoperative course was uneventful.

Figure 2.

Transection of the gross lung specimen shows a gallstone encapsulated by surrounding fibrous reactive tissue.

DISCUSSION

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is now the standard of care for the surgical management of cholelithiasis. Gallbladder perforation occurs in 10% to 32% of patients who have laparoscopic cholecystectomies. Gallstone spillage is estimated to occur in 0.2% to 20% of cases with very few causing complications. A case review of 1130 consecutive laparoscopic cholecystectomies performed at 2 different institutions demonstrated a 0.3% complication rate from intraoperative stone spillage at 13-year follow-up.1

Complications from gallstone spillage vary from trocar-site wound infections to overt intraabdominal abscess as well as gynecological and intrathoracic complications.2 Thoracic complications of retained gallstones with pleurobiliary and bronchobiliary fistulas were reported as early as 1955.3 Some of these complications present in an insidious fashion several years after the cholecystectomy. The mean time to onset of complications is 6 months, but a case report exists of a gallstone-associated subphrenic abscess presenting 10 years after the cholecystectomy.4,5

Our case represents a complication of a spilled gallstone at the time of laparoscopic cholecystectomy that eroded through the right diaphragm and caused pneumonitis presenting as intermittent hemoptysis. Although our patient never had an overt intraabdominal abscess, clinically and by imaging, he had a prolonged right subdiaphragmatic inflammatory process that allowed the intrathoracic migration of the gallstone. Preventative measures included the use of a plastic bag when handling the gallbladder. If stone spillage occurs, a serious attempt to retrieve as many stones as possible with a larger forceps should be made followed by copious amounts of irrigation with a large bore suction catheter. This should be performed laparoscopically without conversion to an open procedure, as overall complication rate of stone spillage is 0.3%.

Before the advent of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, cholelithoptysis and intrathoracic complications from gallstones were rare. Broncholithoptysis, “coughing up stones,” was classically due to calcified peribronchial lymph nodes that eroded through the bronchial wall. They were composed of calcium phosphate or calcium carbonate. These cases are usually associated with histoplasmosis or tuberculosis.

There are 11 case reports in the literature of gallstones in the thoracic cavity following cholecystectomy (Table 1). Nine cases presented as cholelithoptysis, and the latest one as massive hemoptysis from a gallstone-associated abscess.

Table 1.

Complications of Intrathoracic Gallstones

| Investigator | Presenting Symptom | Onset | Calcified nodule on CXR | Location | Intra-abdominal Fluid Collection | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schwegler 19756 | Hemoptysis | 36 m | Yes | RLL | Yes | RLL lobectomy |

| Lee 19937 | Cholelithoptysis/massive hemoptysis | 8 m | No | RLL | Yes | Laparotomy/bronchoscopy |

| Lee 19937 | Cholelithoptysis | 9 m | Yes | RLL | Yes | Lung wedge resection |

| Downie 19938 | Cholelithoptysis/hemoptysis | 12 m | No | RLL | Yes | Bronchoscopy/antibiotics |

| Thompson 19959 | Cholelithoptysis/hemoptysis | NS | No | RLL | Yes | Bronchoscopy/antibiotics |

| Barnard 199510 | Cholelithoptysis/hemoptysis | 13 m | Yes | RML | Yes | Antibiotics/RML lobectomy |

| Breslin 199611 | Cholelithoptysis/hemoptysis | 2 m | No | RLL | No | Antibiotics |

| Chan 199812 | Cholelithoptysis | 6 m | No | RLL | Yes | Antibiotics |

| Baldo 199813 | Cholelithoptysis/hemoptysis | 60 m | No | RLL | No | Spontaneous resolution |

| Chopra 199914 | Cholelithoptysis | 30 m | No | RLL | Yes | Antibiotics |

| Werber 200315 | Abscess with massive hemoptysis | 6 m | Yes | RLL | Yes | RLL wedge resection |

| Fontaine 2004 | Hemoptysis | 34 m | No | RLL | Yes | RLL wedge resection |

Three possible routes of intrathoracic migration of gallstones exist: the lymphatic channels of Ranvier, congenital diaphragmatic defects, and transdiaphragmatic tracts that form from local infection/inflammation.

CONCLUSION

As seen in our case, prolonged chest symptoms, especially with findings in the RLL, following a laparoscopic cholecystectomy should raise the suspicion of intrathoracic gallstones. One must search for an intraabdominal collection and consider antibiotic treatment, percutaneous drainage, or laparotomy. Thoracotomy is rarely required and only indicated for obstructing pneumonia, refractive hemoptysis, or nodules of uncertain cause.

If stone spillage occurs during a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, documentation in the chart would be valuable to clinicians following the patient, allowing them to have a high clinical suspicion when abdominal or thoracic symptoms occur.

Contributor Information

Jacques P. Fontaine, Division of Thoracic Surgery, University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worcester, Massachusetts, USA..

Roger A. Issa, Division of Thoracic Surgery, University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worcester, Massachusetts, USA..

Rhonda K. Yantiss, Department of Pathology, University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worcester, Massachusetts, USA..

Francis J. Podbielski, Division of Thoracic Surgery, University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worcester, Massachusetts, USA..

References:

- 1. Horton M, Florence MG. Unusual abscess patterns following dropped gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 1998; 175 (5): 375–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vadlamudi G, Graebe R, Khoo M, Schinella R. Gallstones implanting in the ovary. A complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1997; 121 (2): 155–158 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adams HD. Pleurobiliary and bronchobiliary fistulas. J Thorac Surg. 1955; 30: 255–260 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bandyopadhyay D, Kapadia CR, Blake SG. “The stones… to rise.” Surg Endosc. 2002; 16 (10): 1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chin PT, Boland S, Percy JP. “Gallstone hip” and other sequelae of retained gallstones. HPB Surg. 1997; 10 (3): 165–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schwegler N, Endrei E. Gallstone in the lung. Radiology. 1975; 115 (3): 541–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee VS, Paulson EK, Libby E, Flannery JE, Meyers WC. Cholelithoptysis and cholelithorrhea: rare complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Gastroenterology. 1993; 105: 1877–1881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Downie GH, Robbins MK, Souza JJ, Paradowski LJ. Cholelithoptysis: a complication following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Chest. 1993; 103 (2): 616–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thompson J, Pisano E, Warshauer D. Cholelithoptysis: an unusual complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Clin Imaging. 1995; 19 (2): 118–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barnard SP, Pallister I, Hendrick DJ, Walter N, Morritt GN. Cholelithoptysis and empyema formation after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995; 60 (4): 1100–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Breslin AB, Wadhwa V. Cholelithoptysis: a rare complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Med J Aust. 1996; 165 (7): 373–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chan SY, Osborne AW, Purkiss SF. Cholelithoptysis: an unusual complication following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Dig Surg. 1998; 15 (6): 707–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baldo XRS, Belda J, Monton C, Canalis E. Cholelithoptysis as spontaneous resolution of a pulmonary solitary nodule. Eur J Cardiothor Surg. 1998; 14 (4): 445–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chopra P, Killorn P, Meharan RJ. Cholelithoptysis and pleural empyema. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999; 68: 254–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Werber Y, Wright C. Massive hemoptysis from a lung abscess due to retained gallstones. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001; 72: 278–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]