Abstract

Background:

Ten percent of gastric cancer (GC) cases are familial, with one third resulting from a mutation in the tumor suppressor gene CDH1. Loss of this important structure can result in hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC), which carries a high mortality if early diagnosis is not made. Despite its clear genetic origin, optimal management of HDGC family members is controversial, as the utility and efficacy of current cancer screening programs for mutation carriers are unproven.

Methods:

A 53-year-old Caucasian woman was initially seen for genetic screening because multiple family members had mutations of the CDH1 gene. Her pedigree analysis demonstrated 4 generations of gastric cancer, and 2 of the generations carried the CDH1 germline mutation, consistent with HDGC. At endoscopy, the patient's gastric mucosa was normal and random biopsies were also normal. The patient underwent a laparoscopic total gastrectomy.

Results:

The gross examination of her stomach appeared normal. On histologic examination, however, the stomach was found to have diffuse (signet ring cell) adenocarcinoma in-situ with 11 microscopic foci of invasive adenocarcinoma limited to the lamina propria.

Conclusions:

Our case is the first reported prophylactic total gastrectomy utilizing a laparoscopic approach, and it highlights the importance of taking a thorough family history and obtaining a pedigree analysis. Endoscopic screening in HDGC cannot rule out diffuse GC, because the stomach and biopsies can be normal despite the presence of adenocarcinoma. Therefore, our case supports the recommendation for prophylactic gastrectomy in HDGC.

Keywords: Laparoscopic-assisted total gastrectomy, Gastric cancer

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer (GC) will account for approximately 22,000 cases of cancer in the United States in 2006, with 10% being familial.1 Of the familial gastric cancers, approximately one third result from a mutation in the tumor suppressor gene CDH1, which normally encodes for the protein E-cadherin.2 This mutation has an autosomal dominant inheritance with a high rate of penetrance. Patients who are CDH1 positive are at high risk for diffuse gastric cancer, which carries a poor prognosis if an early diagnosis is not made.

The CDH1 gene is located on chromosome16p22.1 and contains 2.6kb of coding sequences with 16 exons. It encodes for a transmembrane protein, E-cadherin, with 5 tandemly repeated extracellular domains and a cytoplasmic domain that connects to an actin cytoskeleton through a complex with α, β, and ʳ catenins.3 The mature protein product belongs to the family of cell-cell adhesion molecules. E-cadherin is important for establishing cell polarity and maintaining normal tissue morphology and cellular differentiation.3 Loss of the CDH1 gene function impairs cell adhesiveness as well as cell proliferation pathways.4 The mechanism by which these E-cadherin mutations actually lead to cancer is complex and not well understood. The disrupted cell adhesion is likely to play a role in the initiation of cell proliferation by allowing escape from growth control signals. Alternatively, the cytoplasmic domain of E-Cadherin may modulate specific signaling pathways by inhibiting the availability of free cytoplasmic ʲ-catenin, in a manner complementary to the product of the colorectal tumor-suppressor gene APC.5 Germline CDH1 mutations have an approximately 70% to 80% penetrance.6 Each individual in a cancer syndrome family has a 50% chance of inheriting the mutant gene, due to the autosomal dominant transmission.4 Gene carriers have a cumulative lifetime risk estimated at 67% for men and 83% for women7 of developing GC by the age of 80.

HDGC is defined as1 families with 2 or more documented cases of pathologically proven diffuse GCs in first- or second-degree relatives with at least one diagnosed before the age of 50, or2 3 or more cases of documented diffuse gastric cancer in first- or second-degree relatives, independent of age of onset.8 It is predicted that up to 25% of families that fit these criteria will have inactivating germline CDH1 mutations. Early onset of phenotypic expression is a defining feature of inherited malignancies, as evidenced by the vast majority of families with truncating CDH1 mutations that fulfill the above diagnostic criteria.

Despite its clear genetic origin, optimal management of HDGC family members has been controversial. Early genetic screening and testing is mandatory, with prompt intervention for affected individuals. There are currently no methods available to predict which mutation carrier will develop phenotypic expression (ie, diffuse gastric cancer). The utility and efficacy of current surveillance programs for CDH1 mutation carriers are unproven,9 which has given credence to the recommendation for prophylactic gastrectomy.8

Endoscopic screening and surveillance is inappropriate in the great majority of cases of CDH1 germ-line mutations, as patients usually have normal-appearing gastric mucosa endoscopically. Random biopsies are often negative when in fact the histologic specimen often has multiple foci of carcinoma in situ and invasive carcinoma with negative biopsies. Therefore, prophylactic total gastrectomy is warranted in this high-risk group.

CASE REPORT

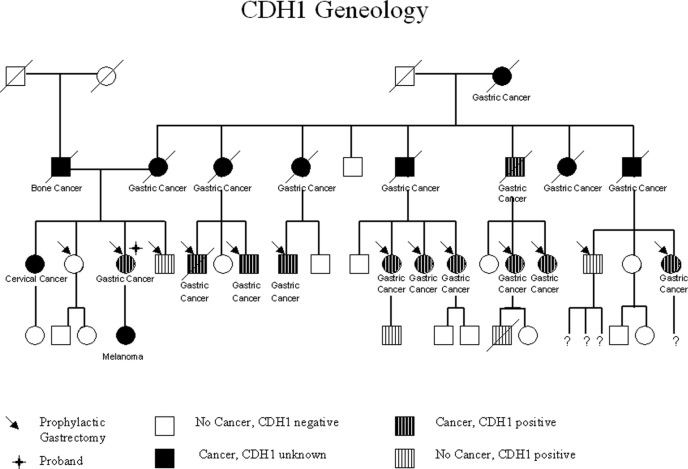

A 53-year-old asymptomatic Caucasian female was referred for prophylactic total gastrectomy because she was found to carry a mutation of the tumor suppressor gene CDH1. Multiple family members had died from gastric cancer. Her grandmother died from diffuse gastric cancer at age 63, and of her grandmother's 8 children, 7 died from diffuse gastric cancer at ages ranging from 26 years to 67 years of age. Among her (third) generation, 13 cousins including herself ultimately underwent prophylactic total gastrectomy after testing positive for the CDH1 mutation. Pedigree analysis of her family shows that the family has an inheritable gastric cancer that exhibits autosomal dominant transmission with high penetrance (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Genealogy demonstrating 4 generations of stomach cancer, 2 of which carried the CDH1 germline mutation, consistent with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC). Thirteen patients had prophylactic gastrectomy, including the proband who underwent successful total laparoscopic gastrectomy. Eighteen patients were identified as having gastric cancer, and 11 of those were identified as carrying the CDH1 tumor suppressor gene mutation. Three patients were identified as carrying the CDH1 tumor suppressor gene mutation but did not have cancer.

The patient denied any gastrointestinal symptoms. She had no significant past medical history. Surgical history was significant for a tubal ligation. She did not take any medications. Her physical examination was unremarkable. Previous upper endoscopy revealed no abnormalities and random gastric biopsies were unremarkable.

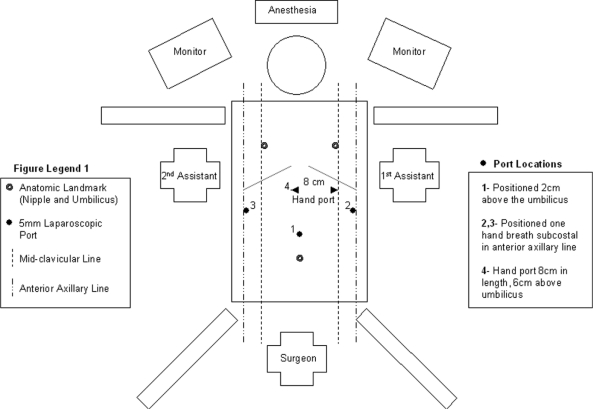

After extensive genetic counseling and discussions regarding the risks and benefits, she elected to undergo a prophylactic total gastrectomy. Laparoscopic hand-assisted total gastrectomy was performed with Roux-en-Y reconstruction. The patient was placed in the lithotomy position with the operating surgeon positioned between the legs. A total of 4 ports were used (three 5-mm ports and one 12-mm port) in addition to the hand port (Figure 2). The jejunojejunostomy (JJ) was created with a linear laparoscopic stapling device, and the common channel enterostomy was closed with a running full-thickness suture. The mesenteric defect at the JJ was closed. The Roux limb was brought in a retrocolic fashion, and the mesocolic defect including Peterson's defect was closed. The Roux limb was 60cm in length. With the patient in full reverse Trendelenberg, gastric resection was performed and the specimen removed through the hand port. Gross examination of the resected stomach was performed. Esophagojejunostomy was performed using a #21 EEA stapler. The anvil was passed transorally. Esophageal and duodenal mucosa were confirmed in the specimen before closure.

Figure 2.

Diagram of patient in lithotomy position with location of surgeon, assistants, and placement of laparoscopic ports.

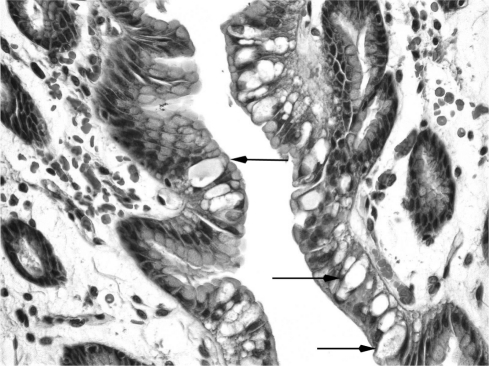

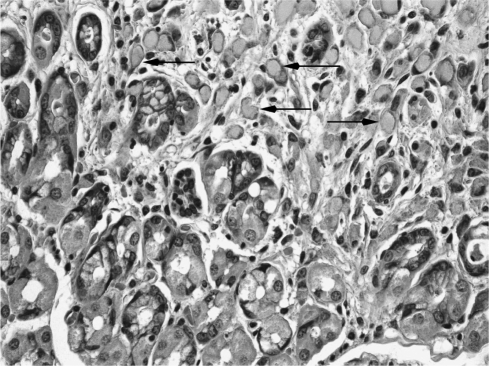

The resected stomach was grossly unremarkable. Only microscopic examination of the entire gastric mucosa revealed widespread adenocarcinoma in situ (Figure 3) and 11 foci of invasive adenocarcinoma limited to the lamina propria (Figures 4). An additional finding was of hypervacuolation of the foveolar epithelium (globoid changes), and slight chronic active gastritis. The histological features of the tumor, including its signet ring cell morphology, its multifocality, and its superficial distribution, and the associated globoid changes of normal foveolar mucosa have been described in prophylactic gastrectomy of patients with E-cadherin germ-line mutations.10,11

Figure 3.

Adenocarcinoma in situ, showing neoplastic goblet cells within foveolar epithelium (as outlined by black arrows).

Figure 4.

Focus of invasive adenocarcinoma, showing signet ring cells in the lamina propria distorting gastric glands (as outlined by black arrows).

The patient's postoperative course was uneventful. She had return of bowel function on postoperative day 3 and was allowed to eat. She was discharged home on postoperative day 4 tolerating a postgastrectomy diet. She developed a stricture at the esophagojejunal anastomosis 6 weeks postoperatively, which was successfully treated with endoscopic balloon dilation. More than one year after the surgery, she is disease free and doing well.

DISCUSSION

Sokoloff is credited for the earliest recognition of a gastric cancer prone family (the Bonaparte family).12 Napoleon Bonaparte died in 1821 while in his sixth year in exile on St. Helena. His postmortem examination revealed a perforated malignant gastric ulcer.13 At 52, on his death bed, he was heard to utter “pylorus… my father's pylorus.”12 His father died from an autopsy proven gastric cancer, and it has been proposed that his grandfather, his brother, and 3 sisters also died from GC.12 Familial gastric cancer in a kindred of New Zealand Maori ethnicity was originally reported in 1964, and the pedigree pattern was consistent with an autosomal dominant inheritance.14 It was not until 1998 that germline truncating mutations of the CHD1 tumor suppressor gene were described in 3 New Zealand Maori families predisposed to diffuse GC.6 This led to the formation of the International Gastric Cancer Linkage Consortium (IGCLC) where the name “hereditary diffuse gastric cancer” (HDGC) was designated.8 There have been several reports of prophylactic gastrectomy for CDH1 gene mutation carriers in the literature (Table 1). Lewis et al15 reported on 6 patients from 2 families, and all patients recovered uneventfully and were discharged on average 7 days postoperatively. Chun et al16 reported on 5 patients from a single family with no reported complications. Newman and Mulholland17 reported on 2 patients from the same family. All patients underwent open total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction. Two other groups18,19 reported a total of 12 patients, but the details of their perioperative care was not reported.

Table 1.

Summary of All Previous Documented Open Prophylactic Gastrectomies

| Series | No. of Patients | Reconstruction | Mean Length of Stay (d) | Foci of Adenocarcinoma (No. of Pts) | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lewis et al | 6 | Roux-en-Y | 7 | 6 | Stricture, SBO, septic thrombophlebitis, dumping |

| Chun et al | 5 | Roux-en-Y | 7 | 5 | Nil |

| Charlton et al | 6 | Not reported | Not reported | 6 | Not reported |

| Suriano et al | 6 | Not reported | Not reported | 5 | Not reported |

| Newman | 2 | Roux-en-Y | 11 | 0 | Prolonged ileus, wound infection, dumping |

Based on this review, our case brings the total number of prophylactic gastrectomies to 26, and, to the best of our knowledge, our case is the first prophylactic laparoscopicassisted total gastrectomy performed for HDGC. The benefits of laparoscopic total gastrectomy are clearly demonstrated in our case. The patient had early return of bowel function, tolerated oral intake early, and was discharged on postoperative day 4. This is in contrast to open gastrectomies where the average length of stay ranges from 7 days to 11 days.

A noteworthy observation is that 23 of 26 patients who underwent prophylactic gastrectomy, including our patient, had foci of adenocarcinoma despite normal surveillance endoscopy. This further establishes the role of prophylactic gastrectomy in these patients; in fact, the surgery that was intended to be prophylactic proved to be therapeutic and curative.

In regards to the laparoscopic versus the open technique, definite conclusions cannot be made from one case, but our preference for the laparoscopic approach is supported by Usui et al20 who showed that time to first flatus, time to initial oral intake, and postoperative hospital stay were significantly shorter (P < 0.05) in laparoscopic gastric surgery than in open gastric surgery. Their report concluded that laparoscopic-assisted total gastrectomy is suitable and feasible for early gastric cancer and has the advantage of a shorter recovery time compared with that for open total gastrectomy.

Laparoscopic total gastrectomy has been criticized because of the doubts that remain about its ability to satisfy all the oncologic staging criteria met during conventional open surgery. Although no long-term studies have been conducted, adenocarcinoma in HDGC, when present, exists at a very early stage (TisN0M0). Therefore, the classical D1 or D2 dissection is not necessary. The guideline given by the IGCLC is that when a total gastrectomy is performed, it is essential to document the complete removal of gastric mucosa by pathologically identifying rims of esophageal and duodenal mucosa at the 2 ends of the surgical specimen.8 Laparoscopic total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction can satisfy this requirement and, given the improved postoperative recovery and decreased morbidity, it is well suited for the asymptomatic, cancer-susceptible patients found in HDGC families. However, only surgeons experienced in advanced laparoscopy should attempt laparoscopic gastrectomy.

Total gastrectomy is not without complications. Overall, the 30-day mortality for total gastrectomy ranges from 3% to 6%.21 However, considering that gastrectomy is usually performed in older patients, the complication rate in a younger, healthier population, such as those with HDGC undergoing prophylactic gastrectomy, are expected to be much less, with an estimated mortality of 1% to 2%.8 Long-term morbidity after total gastrectomy is related to alteration of eating habits, dumping syndrome, diarrhea, and weight loss. There is usually a 10% to 15% decrease in body weight, which is principally a decrease in body fat.21 Dumping syndrome occurs in 20% to 30% of patients but improves over time.22

Laparoscopic total gastrectomy for HDGC should not be performed without genetic counseling and genetic testing. The modified screening criteria as proposed by Suriano et al19 should be used to determine which families should be screened. The age at which genetic screening should be initiated is controversial, because patients younger than age 18 have undergone prophylactic gastrectomy.18 However, current consensus requires that the patient is able to give informed consent.23

CONCLUSION

Genomics is playing an ever-greater role in clinical medicine. This is highlighted in our case, in which a patient with a CDH1 mutation within a family of HDGC underwent prophylactic laparoscopic gastrectomy. Despite the normal appearance of the stomach endoscopically, many microscopic foci of invasive adenocarcinoma were present. Thus, the surgery was curative. This review highlights the poor prognosis in those family members who did not receive gastrectomy, as death ensued within 1 year to 2 years after diagnosis. The penetrance in this family was high, with >70% of family members who acquired the CDH1 gene mutation developing diffuse gastric cancer.

Endoscopic screening in HDGC cannot be recommended because the stomach will appear normal and biopsies can and often fail to demonstrate the (signet ring cell) adeno-carcinoma in situ or invasive adenocarcinoma that is invariably found in resected stomachs. Prophylactic gastrectomy has provided many members of this family with relief from gastric cancer with minimal complications. This case further supports the current recommendation in the literature for prophylactic gastrectomy in HDGC. Furthermore, we report that successful complete gastrectomy can be accomplished laparoscopically without complication, thus reducing the length of hospitalization and providing a minimally invasive alternative to more traditional open surgery. In fact, the laparoscopic approach should be offered first to CDH1-positive patients.

Contributor Information

Wesley P. Francis, Department of Surgery, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan, USA.

Daniald M. Rodrigues, Department of Internal Medicine, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan, USA..

Nolan E. Perez, Division of Gastroenterology, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan, USA..

Fulvio Lonardo, Department of Pathology, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan, USA..

Donald Weaver, Department of Surgery, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan, USA.

John D. Webber, Department of Surgery, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan, USA.

References:

- 1. Society AC. Cancer Facts and Figures. American Cancer Society 2006; Atlanta, Georgia [Google Scholar]

- 2. Oliveira C, Seruca R, Carneiro F. Genetics, pathology, and clinics of familial gastric cancer. Int J Surg Pathol. 2006;14(1):21–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grunwald GB. The structural and functional analysis of cadherin calcium-dependant cell adhesion molecules. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1993;5:797–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Graziano F, Humar B, Guilford P. The role of the E-cadherin gene (CDH1) in diffuse gastric cancer susceptibility: from the laboratory to clinical practice. Ann Oncol. 2003;14(12):1705–1713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morin PJ, Sparks AB, Korinek V, et al. Activation of beta-catenin-Tcf signaling in colon cancer by mutations in beta-catenin or APC. Science. 1997;275(5307):1787–1790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guilford P, Hopkins J, Harraway J, et al. E-cadherin germline mutations in familial gastric cancer. Nature. 1998;392(6674):402–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pharoah PD, Guilford P, Caldas C. Incidence of gastric cancer and breast cancer in CDH1 (E-cadherin) mutation carriers from hereditary diffuse gastric cancer families. Gastroenterology. 2001;121(6):1348–1353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Caldas C, Carneiro F, Lynch HT, et al. Familial gastric cancer: overview and guidelines for management. J Med Genet. 1999;36(12):873–880 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huntsman DG, Carneiro F, Lewis FR, et al. Early gastric cancer in young, asymptomatic carriers of germ-line E-cadherin mutations. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(25):1904–1909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bresciani C, Perez RO, Gama-Rodrigues J. Familial gastric cancer. Ar Qgastroenterol. 2003;40(2):114–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carneiro F, Huntsman DG, Smyrk TC, et al. Model of the early development of diffuse gastric cancer in E-cadherin mutation carriers and its implications for patient screening. J Pathol. 2004;203(2):681–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sokoloff . Predisposition to cancer in the Bonaparte family. Am J Surg. 1938;40:673–678 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sloane . St Helena-1815-1821. Life of Napolean Bonaparte. New York, NY: Century; 1896 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jones EG. Familial Gastric Cancer. N Z Med J. 1964;63:287–296 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lewis FR, Mellinger JD, Hayashi A, et al. Prophylactic total gastrectomy for familial gastric cancer. Surgery. 130(4):612–617, 2001; discussion 617- 619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chun YS, Lindor NM, Smyrk TC, et al. Germline E-cadherin gene mutations: is prophylactic total gastrectomy indicated? Cancer. 2001;92(1):181–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Newman EA, Mulholland MW. Prophylactic gastrectomy for hereditary diffuse gastric cancer syndrome. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202(4):612–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Charlton A, Blair V, Shaw D, et al. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: predominance of multiple foci of signet ring cell carcinoma in distal stomach and transitional zone. Gut. 2004;53(6):814–820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Suriano G, Yew S, Ferreira P, et al. Characterization of a recurrent germ line mutation of the E-cadherin gene: implications for genetic testing and clinical management. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(15):5401–5409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Usui S, Yoshida T, Ito K, et al. Laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: comparison with conventional open total gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2005;15(6):309–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liedman B, Andersson H, Bosaeus I, et al. Changes in body composition after gastrectomy: results of a controlled, prospective clinical trial. World J Surg. 1997;21(4):416–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Miholic J, Meyer HJ, Muller MJ, et al. Nutritional consequences of total gastrectomy: the relationship between mode of reconstruction, postprandial symptoms, and body composition. Surgery. 1990;108(3):488–494 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lynch HT, Grady W, Lynch JF, et al. E-cadherin mutation-based genetic counseling and hereditary diffuse gastric carcinoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2000;122(1):1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]