Abstract

Introduction:

This retrospective study was performed to review the intermediate-term results of the laparoscopic repair of giant paraesophageal hernia (PEH) in the unit.

Methods:

This retrospective 8-year case series involved 42 patients. The clinical records were retrieved, reviewed individually, and data were collected regarding symptoms, investigation, operative details, and follow-up.

Results:

M:F ratio was 1:1.8 and median age was 64 years.Symptoms included epigastric/chest pain (69%), heart-burn (42.8%), dysphagia (38%), vomiting (23.8%), gastric volvulus (19%), and upper GI bleed (16.6%). The repair included reduction, sac excision, esophageal mobilization, and cruroplasty. Fundoplication (anterior partial) was done in 18 (42.8%) patients with radiologically documented reflux. Median hospital stay was 3 days. The complications included esophageal perforation in 1 (2.3%), gas-forming mediastinal abscess in 1 (2.3%), small bowel obstruction in 1 (2.3%), and bilateral basal atelectasis in 3 (7.1%). One patient (2.3%) died due to duodenal perforation and myocardial infarction. Of the 38 (90.4%) patients followed up (median 18m), 20 (52.6%) had a follow-up investigation. One patient (2.6%) had postoperative dysphagia, and 3 (7.8%) had postoperative heart-burn. Five (11.9%) had recurrence. Symptom outcome was Visick grades I/II (86.8%), III (10.5%), and IV (2.6%).

Conclusion:

Laparoscopic repair of PEH resulted in a short length of stay, excellent outcome in almost 87% of patients, and an overall recurrence rate of 11.9%.

Keywords: Laparoscopic, Paraesophageal, Hernia, Fundoplication, Recurrence

INTRODUCTION

Paraesophageal hernia (PEH) forms 5% to 10% of all hiatal herniae. Giant PEH means greater than a third of the stomach in the thorax. Most patients are elderly and with significant associated medical illnesses. This hernia can lead to potentially catastrophic mechanical complications, such as gastric volvulus, hemorrhage, gangrene, and perforation. Conservative management alone for PEH has a potential to result in significant morbidity (hemorrhage volvulus, gangrene, and perforation) in 50% of patients1 and mortality in 27%.2 The conventional repair has been the open abdominal, thoracic or abdomino-thoracic approach. Laparoscopic esophageal surgery was introduced in the early 1990s. Laparoscopic PEH repair has consistently flourished since then.

The aim of this retrospective case series was to review the intermediate-term results of laparoscopic repair of giant PEH.

METHODS

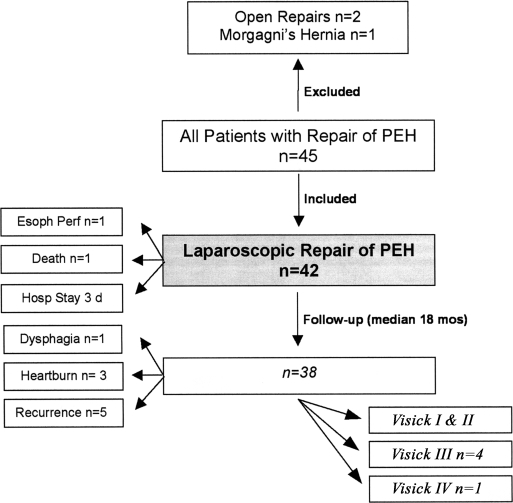

The study was carried out in the department of surgery at a regional hospital in Northern Ireland, United Kingdom. The case records of all patients who had repair of a paraesophageal hernia performed between 1996 and 2004 were retrieved from the Medical Records Department and were reviewed individually (Figure 1). The start date was selected in keeping with the commencement of laparoscopic practice in the unit. Prospectively recorded data were extracted and put on summary sheets and included demographic details, symptoms (chest/epigastric pain, heartburn, dysphagia, vomiting), ASA score, and results of chest x-rays, upper GI endoscopy, and barium esophagogram. Operative details recorded were operative confirmation (type II vs. III), completeness of hernia reduction and sac excision, cruroplasty (suture or mesh), fundoplication, and conversion to laparotomy. Postoperative details included complications, length of stay, duration of follow-up, postoperative dysphagia, heartburn, and recurrence. Visick score (Table 1) was used to quantify the severity of postoperative symptoms.

Figure 1.

Outline of the study.

Table 1.

Visick Grading

| Visick | Symptoms | Quality of Life | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade I | None | Normal | None |

| Grade II | Minimal | Normal | None |

| Grade III | Significant | Relatively normal | Medical only |

| Grade IV | Incapacitating | Affected | Surgical |

Statistical Analysis

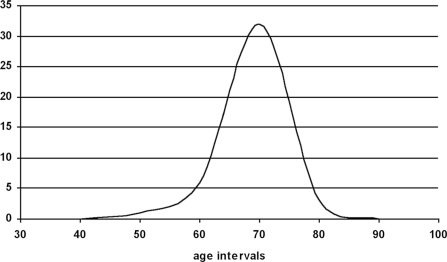

The age distribution was normal. Mean, median with interquartile range (IQR), and mode were calculated. The incidence of complications was described with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The significance was calculated by using the chi-square test for the sex difference and recurrence and also to compare various studies. The data were plotted on Microsoft Excel 2000 and represented in histogram and bar diagrams.

RESULTS

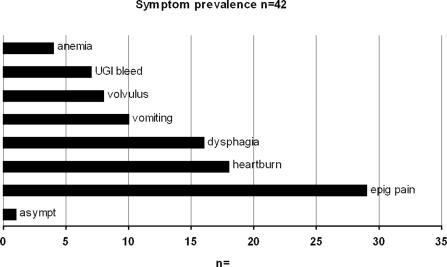

Forty-five case records were identified. Three of them were excluded, because those patients did not have a paraesophageal hernia (Figure 1). Hence, 42 patients were included in this retrospective case series over an 8-year period from 1996 through 2004 (Table 2). All patients had more than one third of the stomach in the thorax. Male to female ratio was 1:1.8. Age range at operation was 45 years to 80 years (arithmetic mean, 64.1; median, 64; IQR, 62 to 67; mode, 64) (Figure 2). Preoperative symptoms included chest/epigastric pain in 29, heartburn in 18, dysphagia in 16, vomiting in 10, gastric volvulus in 8, upper GI bleed in 7, and anemia in 4 patients (Figure 3). Three surgeries were done as an emergency, and the rest were planned operations.

Table 2.

Demographic Details and Symptom Distribution (CI-95% Confidence Interval) (n=42)

| M:F (15 M, 27 F) | 1:1.8 |

| Median Age at Operation (range) | 64 y (45–80 y) |

| Asymptomatic | 1 (2.38%) (−2.22–6.98) |

| Chest/Epigastric Pain | 29 (69%) (55.02–82.98) |

| Heartburn | 18 (42.8%) (27.84–85.6) |

| Dysphagia | 16 (38%) (23.33–52.67) |

| Vomiting | 10 (23.8%) (10.93–36.67) |

| Volvulus 8 (19%) (7.13–30.87) | Hematemesis/Melena 7 (16.66%) (5.41–27.91) |

| Anemia | 4 (9.52%) (3.6–15.44) |

| ASA | |

| I | 17 (40.4%) (25.56–55.24) |

| II | 16 (38%)(23.33–52.67) |

| III | 9 (21.42%)(9.02–33.82) |

| Median Symptom-Operation Gap | 2 years (4 months-20 years) |

| Median Follow-up (38/42 patients) | 18 months (2–42 months) |

| Follow-up Imaging | 20/42 (47.61%) (32.51–62.71) |

Figure 2.

Age distribution for the binomial outcome variable was normal (bell shaped).

Figure 3.

Symptom prevalence among the patients. Symptom-operation gap was a median of 24 months.

Preoperative investigations are shown in Table 2. For diagnosis of PEH, chest x-ray had a sensitivity of 75%, barium esophagogram 100%, and endoscopy 46%. The associated gastroesophageal reflux was diagnosed with barium esophagography. The diagnosis of PEH was regarded as an indication for surgery subject to general health (ASA III or less). The indication of an antireflux procedure was the documentation of reflux on barium study (radiological reflux). Watson's anterior fundoplication was the only antireflux procedure used in this study in n=18 (42.85%). Esophageal manometry and pH studies were not performed.

Veress-induced CO2 pneumoperitoneum was established at 10mm Hg to 12mm Hg. Five to 6 ports were used. The primary port was inserted above the umbilicus. A table-mounted hepatic retractor was used. PEH was reduced with graspers in a hand-over-hand manner. Complete reduction of the contents was achieved in 41/42 (97.6%). The clockwise circum-esophageal dissection was completed, and the sac was excised in 41 (97.6%). The dissection was carried high in the mediastinum for esophageal mobilization in 41 (97.6%). The crura were defined and suture cruroplasty was done using interrupted nonabsorbable suture starting posteriorly in 32 (76.2%). Bridging or buttressing mesh was used in 9 patients (21.4%). In the one remaining patient, the reduction of the hernia could not be completed due to intrasac adhesions, technical difficulty, and failure to progress. Therefore, gastropexy alone was done in this situation. Watson's (anterior partial) fundoplication was done in 18 (42.85%) patients. Postoperatively, the patients had liquids in the evening. A light diet began the following morning.

The median hospital stay was 3 days. The median follow-up for 38 patients (90.47%) was 18 months. Twenty (47.62%) of all patients had a follow-up esophagogram (52.63% of the follow-up patients). The indications were symptom driven (epigastric pain, dysphagia, vomiting). Patients asymptomatic at follow-up did not undergo an esophagogram.

One (2.38%) patient had perioperative esophageal perforation. It was repaired through a laparotomy and fundoplication the next day and the patient recovered. One (2.38%) patient had gas-forming mediastinal abscess requiring CT-guided drainage. The mesh repair remained intact. Small-bowel obstruction occurred in one (2.38%), and atelectasis was seen in 2 (4.76%). One patient (2.38%) died after 3 weeks due to a duodenal perforation and myocardial infarction (Table 3).

Table 3.

Complications of the Repair

| Perioperative Complications | n (%) (95% CI) |

| Conversion | 0 |

| Esophageal perforation | 1 (2.38%) (CI −2.22–6.98) |

| Atelectasis | 3 (7.14%) (CI −0.64–14.92) |

| Small bowel obstruction | 1 (2.38%) (CI −2.22–6.98) |

| Mediastinal abscess | 1 (2.38%) (CI −2.22–6.98) |

| Died | 1 (2.38%) (CI −2.22–6.98) |

| Complications at Follow-up (median 18 months) | n=38/42 (90.47%) |

| Post-op reflux | 3 (7.89%) (CI −0.68–16.46) |

| Post-op dysphagia | 1 (2.63%) (CI −2.45–7.71) |

| Recurrence (overall) | 5/42 (11.9%) (CI 2.11–21.69) |

| Recurrence in followed up cohort | 5/38 (13.15%) (CI 2.45–23.85) |

| Recurrence in pts with follow-up Ba esophagogram (n=20) | 5/20 (25%) (CI 6.03–43.97) |

Of the 38 (90.47%) patients followed up (median, 18 months), 3 (7.89%) had postoperative heartburn requiring proton pump inhibitors (PPI). One (2.63%) had postfundoplication dysphagia and required one sitting of esophageal dilatation. Overall, 5 (11.9%) patients had a recurrence documented on follow-up esophagogram. There was no significant sex influence on recurrence (P=0.434). It turned out to be 13.15% if only the followed up patients were considered and 25% if it narrowed down to only those patients who had follow-up investigation (symptom-driven). One recurrence has been reoperated. The others are being treated conservatively. The symptom outcome according to the Visick score is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Symptom Outcome According to Visick Grading

| Visick Grade | n=38 (95% confidence intervals) |

|---|---|

| I/II | 33 (86.84%) (CI 77–97) |

| III | 4 (10.52%) (CI 0.47–19.53) |

| IV | 1 (2.63%) (CI −8.53–13.73) |

DISCUSSION

This is the largest series on laparoscopic repair of PEH from Northern Ireland. During the course of the study, it became clear that the condition of PEH was more prevalent than many imagined. Frequently, the patients were referred by radiologists who recognized the condition on “routine” chest x-ray. On many occasions, these have been reported as incarcerated or fixed hiatus hernias, and the clinical significance was not conveyed to the referring clinician. After discussion with the radiologists, it was decided that these should be reported as gastric volvulus/ hiatus hernia. This resulted in more referrals to us. Not infrequently, these patients had been under the treatment of the gastroenterologist, had had more than one upper GI endoscopy, and had simply been treated with PPI, often with no benefit. It was only when other symptoms like dysphagia or volume reflux/regurgitation were added to those already present that the condition was properly recognized. It is stressed that PPIs only help a few, and only surgical intervention is likely to help the vast majority. The patients should be counseled that the condition will not improve, that the intrathoracic component can only increase with time and that with this progression, the potential for serious complication increases. Surgery is also easier in the early stages.

In this study, the index of suspicion of PEH on part of the referring sources (general practitioners and physicians) generally was not very high. Despite evident x-ray findings, some patients were treated for ailments like coronary or chronic airway disease. There was a recognized tendency to either label hernias as type-I or not stress them enough at the time of identification. Surgical specialties (other than upper GI) appeared not to emphasize the condition sufficiently to merit an appropriate referral.

Routine chest radiograph and barium esophagogram had very high diagnostic sensitivity (75% and 100%, respectively). Upper GI endoscopy is reported to have a low sensitivity of 17%.3 Without a reasonable index of suspicion, it is difficult for an average endoscopist to detect the relevant findings like eccentric cardiac orifice, diminished stomach capacity, distortion of the pylorus, very deep fundus, and inability to enter the duodenum.

The dilemma whether to add adjunct fundoplication is unresolved. It appears to be the customary practice. However, there is a lack of prospective randomized case controlled trials providing evidence for mandatory fundoplication. Currently, only a few surgeons apply selective policy (variably based on preoperative clinical reflux or evidence-based diagnosis of reflux). The majority adopts a mandatory fundoplication policy. Whereas symptomatic postoperative reflux can usually be managed pharmacologically, postfundoplication dysphagia may be prolonged. This study has used the selective application of fundoplication based on preoperative radiological evidence of reflux. It may be a trade-off between postoperative reflux and postoperative dysphagia. Also, it is assumed that the restoration of the gastroesophageal junction below the hiatus should reverse the gastroesophageal acid reflux. The factor that counters this “incidental” correction of reflux is the degree to which the cardia is distorted during dissection. The hospital stay is by far better with the laparoscopic method.

The recurrence after laparoscopic repair of PEH is between 5% and 42%. It may be attributed to poor quality of the crura, incomplete sac excision, and lack of esophageal mobilization. Excessive tension at the crural repair is to be avoided. The recurrence tends to take place in the first year and often has minimal symptoms. It is mostly sliding in nature. The significance of, and the strategy to deal with recurrence, remains unclear. It appears to be higher in studies where more patients had follow-up esophagograms (Table 5). The studies appear to have similar overall recurrence outcomes (P=0.10). However, when evidence is used with follow-up esophagogram, the difference in various reports is statistically significant (P=0.05), thereby suggesting a possible technique difference (technique evolution over time). We have a meta-analysis ready to go of 13 papers (1991 through 2006) addressing >25 laparoscopic PEH repairs revealing a true recurrence rate of 25.5% (with likely impressive benefit of esophageal lengthening by Collis-Nissen operation).

Table 5.

Recurrence in Studies Where More Patients Had Follow-up Barium Esophagography (chi squared P=0.10 for overall recurrence; P=0.05 for follow-up esophagograms)

| Study | Lap/Open | n | Antireflux Yes/No | Follow-up Barium Esophagography | Overall Recurrence | Recurrence Among Barium Esophagography |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This study 2006 | Lap | 42 | Selective | 52.6% | 11.9% | 25% |

| Wiechmann 20014 | Lap | 54 | Yes | 73% | 7% | 9% |

| Diaz 20035 | Lap | 116 | Yes | 69% | 22% | 32% |

| Mattar 20026 | Lap | 125 | Yes | 26% | 33% | 43% |

| Wu 19997 | Lap | 37 | Yes | 94% | 21% | 23% |

| Jobe 20028 | Lap | 52 | Yes | 65% | 21% | 32% |

| Perdikis 19979 | Lap | 65 | Yes | 70% | 12% | 17% |

| Swanstrom 199910 | Lap | 52 | Yes | 61% | 8% | 12% |

| Loustarinen 199811 | Lap | 22 | Yes | 86% | 36% | 42% |

CONCLUSION

Laparoscopic repair of giant PEH with selective fundoplication resulted in a short length of stay, excellent outcome in 87% of patients, moderately good (clinically beneficial) outcome in another 10%, and a “true” recurrence rate of 25% (customary overall recurrence rate of 11.9%). These results are better in clinical situations than in statistics as the asymptomatic recurrence appears to be unlikely to trouble the patient during the rest of his or her life span.

Contributor Information

Munir A. Rathore, Clinical Fellow in Surgery, Antrim Area Hospital, N/Ireland UK..

Imran Andrabi, Specialist Registrar in Surgery, Craigavon Area Hospital, N/Ireland UK..

El Nambi, SHO, Department of Surgery Antrim Area Hospital, N/Ireland UK..

Arthur H. McMurray, Consultant Surgeon & Director of Surgery, Antrim Area Hospital, N/Ireland UK..

References:

- 1. Treacy PJ, Jamieson GG. An approach to the management of para-oesophageal hiatus hernias. Aust N Z J Surg. 1987; 57: 813–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Skinner DB, Belsey RH. Surgical management of esophageal reflux and hiatus hernia: long-term results with 1,030 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1967; 53: 33–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gantert WA, Patti MG, Arcerito M, et al. Laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hiatal hernias. J Am Coll Surg. 1998; 186 (4): 428–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wiechmann RJ, Ferguson MK, Naunheim KS, et al. Laparoscopic management of giant paraesophageal herniation. Ann Thoracic Surg. 2001; 71 (4): 1080–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Diaz S, Brunt LM, Klingensmith ME, Frisella PM, Soper NJ. Laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair, a challenging operation. J Gastrointestinal Surg. 2003; 7 (1): 59–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mattar SG, Bowers SP, Galloway KD, Hunter JG, Smith CD. Long-term outcome of laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernia. Surg Endosc. 2002; 16 (5): 745–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wu JS, Dunnegan DL, Soper NJ. Clinical and radiological assessment of laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: Surg Endosc. 1999; 13 (5): 497–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jobe BA, Aye RW, Deveney CW, Domreis JS, Hill LD. Laparoscopic management of giant Type III hiatal hernia and short esophagus objective follow-up at three years. J Gastrointestinal Surg. 2002; 6 (2): 181–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Perdikis G, Hinder RA, Filipi CJ, Walenz T, McBride PJ, Smith SL, Katada N, Klingler PJ. Laparoscopic paraoesophageal hernia repair: Arch Surg. 132 (6): 586–589, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Swanstrom LL, Jobe BA, Kinzie LR, Horvath KD. Esophageal motility and outcomes following laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair and fundoplication. Am J Surg. 1999; 177 (5): 359–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Luostarinen M, Rantalainen M, Helve O, Reinikainen P, Isolauri J. Late results of paraoesophageal hiatus hernia repair with fundoplication. Br J Surg. 1998; 85 (2): 272–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]