Abstract

Background:

We present a case in which laparoscopy was both diagnostic and therapeutic in a patient with a spigelian hernia.

Case Report:

A 35-year-old man was referred to the General Surgery Service for evaluation of right lower quadrant abdominal pain of approximately 6 months. The pain was not disabling but was a constant discomfort. The patient did not have any significant past medical or surgical history, and the physical examination was significant only for an area of focal tenderness in the right lower quadrant. Ultrasound and CT scans of the patient's abdomen were unremarkable. A laparoscopic exploration of the area revealed a defect in the area of semilunar and semicircular lines consistent with a spigelian hernia. The patient underwent a laparoscopic herniorrhaphy with placement of a polypropylene mesh.

Conclusion:

This case illustrates the role of laparoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of spigelian hernias.

Keywords: Spigelian hernia, Laparoscopic herniorrhaphy

INTRODUCTION

The diagnosis of spigelian hernias by history and physical examination is notoriously difficult. Recently, imaging modalities, such as ultrasound and computed tomography, have increased preoperative diagnostic yield. However, in some, the spigelian hernia eludes diagnosis. We present a case where laparoscopic surgery was both diagnostic and therapeutic in an individual with a spigelian hernia. The purpose of this case report and literature review is to describe and review the use of minimally invasive surgery in the diagnosis and repair of abdominal wall defects such as spigelian hernias. We conducted a Medline search of all reported cases of laparoscopic spigelian hernia repairs that were published in English to date.

METHODS

Just prior to the induction of anesthesia, the patient's abdomen was palpated until his typical abdominal pain and discomfort were reproduced. This area corresponding to his symptoms was outlined around the examining finger with a marking pen. Topographically, this coincided with the area of the right spigelian aponeurosis. The patient underwent general endotracheal anesthesia.

A vertical supraumbilical incision was made approximately 5 cm superior to the umbilicus, and intraperitoneal access was gained with a Veress needle. The abdomen was insufflated with carbon dioxide to a pressure of 15 mm Hg. A 10-mm, 30-degree laparoscope was inserted into the abdomen, and immediately upon entry a small cleft-like defect was seen in the area corresponding to that marked on the skin. This was confirmed by finger pressure on the area marked on the abdominal skin. This site was in the proximity of the topographical representation of the junction of the semilunar and semicircular lines, making it consistent with a spigelian hernia. A small, discolored fibrotic piece of omentum was discovered intraperitoneally. This was lying close to the hernial defect and may have represented formerly incarcerated contents of the hernia. We suspect that the intraperitoneal insufflation to 15 mm Hg, with separation of the anterior abdominal wall from the abdominal contents, may have affected reduction of the hernia. A full laparoscopic exploration of the abdomen with attention focused on both inguinal regions and the contralateral spigelian aponeurosis was completed without finding other defects.

Two 5-mm trocars through which dissecting instruments were passed were placed in the left lower quadrant of the abdomen. The peritoneum surrounding the defect was dissected circumferentially with a combination of sharp and blunt instrumentation (Figure 1). This dissection revealed that the defect was considerably larger than was first suspected. A 4 x 6-cm piece of polypropylene mesh was delivered into the abdominal cavity though the 10-mm camera port. It was positioned preperitoneally to cover the defect (Figure 2). The intraabdominal insufflation pressure was decreased to 8 mm Hg, and the peritoneum was tacked over the mesh (Figure 3). The trocars were then removed and the trocar sites inspected for bleeding. The fascia around the 10-mm trocar site incision and the skin at all trocar sites were closed with absorbable suture.

Figure 1.

Cleft defect seen corresponding to the exact location of the patient's pain.

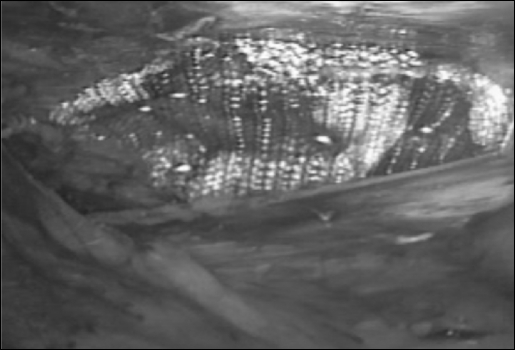

Figure 2.

Placement of polypropylene mesh in area of defect after creation of peritoneal flaps.

Figure 3.

Tackers used to secure mesh and peritoneum to over-lying defect.

RESULTS

The patient had an uneventful recovery and was discharged in stable condition.

DISCUSSION

Adrian van der Spieghel, born in Padau in 1578, is credited with the initial description of the semilunar line.1 This line demarcates where the transverses abdominis muscle becomes aponeurotic as it travels medially toward the rectus sheath.2 That portion of the transverses abdominis muscle bordered by the semilunar line laterally, and the lateral border of the rectus sheath medially, is termed the spigelian aponeurosis. Spigelian hernias protrude through this aponeurosis. The first report of a spigelian hernia appeared in 1764, and it is attributed to Klinkosch. He called the defect Spieghel's linear hernia.3

The majority of spigelian hernias are located in proximity to the point where the semilunar line crosses the semi-circular line of Douglas. The proclivity for this area is thought to be due to the division of the spigelian aponeurosis into 2 layers in this region. Here, the fibers of the spigelian aponeurosis interdigitate with the fibers of the anterior and posterior rectus sheaths. The dorsal layer of the spigelian aponeurosis is particularly weakened by this loss of uniformity. Inferior to this area, the spigelian aponeurosis is reconstituted into a single, stronger layer. Nonetheless, a number of hernias have been reported protruding through the spigelian aponeurosis in the region of Hesselbach's triangle. These are called low spigelian hernias.4 Most spigelian hernias are intercalated between layers of the abdominal wall and are thus termed interparietal or interstitial.

The diagnosis of a spigelian hernia by history and physical examination is notoriously difficult because its clinical manifestations are protean. Usually little can be uncovered from the patient's history that is specific for the diagnosis. Vague complaints of abdominal pain are common. Occasionally, symptoms may be referable to an intraabdominal organ, or to tissue that is contained within the hernia sac. Stomach, Meckel's diverticulum, colon, appendix, ovary, testicle, and endometrial tissue have all been found in a spigelian hernia sac.5–11 Much of the difficulty with the physical diagnosis of a spigelian hernia is due to the interparietal location of the defect. The hernia protrudes through the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis, but is usually covered superficially by the external oblique muscle. Because the internal oblique offers little resistance, the hernia may spread between the oblique muscles. This can confound surgeons who center an incision over a palpable mass, only to find the actual hernia defect in a remote location. These pitfalls in the history and physical examination of spigelian hernias have resulted in patients being followed for years before the diagnosis is made.

Radiological examinations have been used in an attempt to increase the preoperative diagnostic yield. Conventional and contrast-enhanced studies like plain abdominal roentgenograms, upper gastrointestinal studies, small bowel follow-through, and barium enemas are of little use, particularly in the absence of signs of intestinal obstruction.12–14 Even incarcerated omentum will be missed by these studies. Herniography is of historical curiosity only as it is invasive and inaccurate.15 More success has been achieved with imaging modalities capable of accurately characterizing the abdominal wall.

Abdominal ultrasonography with a 3.5- to 5.0-MHz transducer has been successful in the diagnosis of palpable and nonpalpable spigelian hernias.16 Its resolution for the structures of the abdominal wall is excellent. Findings on an ultrasound examination that suggest the presence of a spigelian hernia include visualization of a complex mass within the layers of the anterior abdominal wall. In particular, mesentery and omentum will appear echogenic, and air-filled bowel will result in shadowing. The presence of one or more of these elements in the anterior abdominal wall, within the spigelian aponeurosis, supports the diagnosis. Additionally, the hernia defect itself can be seen as an interruption in the echo line of the aponeurosis.

Abdominal computed tomography is also an excellent study for the diagnosis of a spigelian hernia.17 Similar to ultrasound, it can delineate the contents of the hernia sac and can demonstrate the defect in the spigelian aponeurosis. Successful diagnosis by computed tomography after a nondiagnostic or equivocal ultrasound have been reported.18 Because it is more easily performed and less costly, some authors have advocated initial examination by ultrasound followed by computed tomography if a diagnosis is still in doubt. Although sophisticated radiological techniques may be helpful, in some cases the hernia still eludes diagnosis.

Spigelian hernias account for only 2% of all abdominal wall hernias. They are associated with a relatively high complication rate, mainly associated with diagnostic delays.19 Therefore, the presence of a spigelian hernia is the indication for its repair. The most common operative approach remains a gridiron skin incision when the hernia is palpable. For nonpalpable defects, a paramedian incision is made in which the ventral lamella of the rectus sheath is opened. Often the patient's incision is disproportionately large for the size of the hernia defect.

A newer, open surgical technique has been described that involves an alternative method of localizing the hernia defect.20 Using an infraumbilical or lower midline vertical incision, a finger is introduced intraabdominally to palpate the defect. A direct cutdown is then performed over the examiner's finger, exposing the hernia defect. Proponents of this technique contend that this can be accomplished through 2 small incisions and obviates the need for both expensive laparoscopic equipment and the use of polypropylene mesh in the abdomen. The description20 included no actual report of its use or its success.

Recently, minimally invasive surgical techniques have been applied to the diagnosis, localization, and repair of spigelian hernias. Our review of the literature yielded 16 reports, which describe a total of 30 cases. There is currently 1 prospective randomized study and 2 case series in the literature.21–23 The remainder are case reports.

In the only prospective trial to date by Moreno-Egea et al,21 open versus laparoscopic repair of spigelian hernias were compared. Their study involved 22 patients, (11 open versus 11 laparoscopic). The laparoscopic group consisted of 8 totally extraperitoneal approaches and 3 intraabdominal approaches. Postoperative morbidity, length of in-hospital stay, number of patients requiring admission, and hernia recurrence were evaluated. They showed the superiority of the laparoscopic technique by demonstrating a significant difference in morbidity between the groups: 4 hematomas in the open group versus none in the laparoscopic group (P<0.05). In addition, the length of hospital stay in the laparoscopic group was significantly shorter: 5 days for the open group versus 1 day for the laparoscopic group (P<0.001). Ninety-one percent of the laparoscopic group were treated on an outpatient basis versus 9% in the open group. No recurrences were noted in either group. They concluded that laparoscopic repair of spigelian hernias significantly reduces patient morbidity and hospital stay and can be safely performed on an outpatient basis.

In the series of Felix and Michas,22 repair was achieved with a preperitoneal polypropylene mesh in 4 cases. Previously unsuspected bilateral inguinal hernias were diagnosed by laparoscopy in 1 case in which a right-sided inguinal hernia was also repaired. All repairs were successfully completed laparoscopically, and no patients required hospital admission.

Successful concomitant laparoscopic repairs of umbilical, inguinal, femoral hernias and cholecystectomy have been described. A case series by Amendolara23 showed successful simultaneous cholecystectomy and umbilical herniorrhaphy performed in 2 of their patients. No complications were reported in that series, and at 3-month follow-up, there had been no recurrences. Fisher24 and Teleky et al25 also reported simultaneous cholecystectomy and spigelian hernia repair with success. The patient reported by Fisher subsequently had a left inguinal hernia repaired laparoscopically, at which time the spigelian herniorrhaphy was found intact.

Strand and Larsen26 described a repair of a spigelian hernia and bilateral femoral hernias in the same patient without complications. Similarly, Gedebou and Neubauer27 repaired bilateral spigelian and inguinal hernias in 1 patient. Again, this was done without complications, and at 1-year follow-up, there were no reported recurrences. De Matteo, Morris, and Broderick28 described the incidental finding and repair of a left spigelian hernia found during a laparoscopic bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection for prostate cancer staging in a 64-year-old man. Repair was performed with a fenestrated PTFE patch and staples. The patient was asymptomatic at 6-month follow-up.

Barie, Thompson, and Mack29 described a planned laparoscopic repair of a spigelian hernia using a composite prosthesis. The patient had a history of a right ovarian chocolate cyst, and on physical examination was found to have a left-sided spigelian hernia. Because the patient was to have a laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy, a laparoscopic mesh repair of the hernia was planned. The procedure was completed without complications, and the patient was symptom-free and without recurrence at 12-month follow-up.

Several case reports (Table 1) by Appeltans,30 Carter and Michas,31 Habib,32 Iswariah,33 Kasirajan,34 Tarnoff,35 and Welter36 demonstrate successful repair of spigelian hernias without significant complications. Successful treatment of a spigelian hernia with incarcerated jejunum in an 80-year-old woman was reported by Novell et al.37 There were no reported complications. Larson and Farley38 at the Mayo Clinic published a retrospective review of 81 patients who underwent spigelian hernia repair. However, only 1 patient was treated laparoscopically. There were no complications with this patient, and after a 7-year follow-up, no recurrence was reported.

Table 1.

Laparoscopic Repair of Spigelian Hernia

| No.of Patients | Complications | Recurrence | Follow-up | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appeltans30 | 1 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Amendolora23 | 2 | 0 | 0 | .25 |

| Barie29 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Carter and Michas31 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| DeMatteo28 | 1 | 0 | 0 | .5 |

| Felix22 | 4 | 0 | 0 | .02 |

| Fisher24 | 1 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Gedebou27 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Habib32 | 1 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Iswariah33 | 1 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Kasirajan34 | 1 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Larson38 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7.5 |

| Moreno-Egea21 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 3.4 |

| Strand26 | 1 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Tarnoff35 | 1 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Welter36 | 1 | 0 | NA | NA |

CONCLUSION

These cases validate the efficacy and safety of laparoscopic management of spigelian hernias. We conclude that the laparoscopic approach to spigelian hernias offers several advantages to any open operative technique currently described. Laparoscopy affords full abdominal exploration and the opportunity for diagnosis of synchronous abdominal conditions, which if present, can be addressed at the same operation. These benefits combined with the low morbidity, low rates of recurrence, and the ability to be safely performed on an outpatient basis, makes laparoscopic repair of Spigelian hernias the treatment of choice.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank the Department of Surgery and the Tripler Army Medical Center support staff for their assistance in this report.

Footnotes

Disclosure: This case report was not funded or performed in the interest of any commercial device, equipment, or instrument. The opinions expressed in the paper are those solely of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of either the United States Army or the Department of Defense.

Contributor Information

Erick G. Martell, Department of Surgery, Tripler Army Medical Center, Honolulu, HI, USA..

Niten N. Singh, Department of Surgery, Tripler Army Medical Center, Honolulu, HI, USA..

Stanley M. Zagorski, Department of Surgery, Tripler Army Medical Center, Honolulu, HI, USA..

Michael A. J. Sawyer, Department of Surgery, Kaiser Permanente Medical Center, Honolulu, HI, USA..

References:

- 1. Spangen L. Spigelian hernia. In: Nyhus L, Condon R. eds. Hernia. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: JB Lippincott Co; 1989:369–379 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Spangen L. Spigelian hernia. Surg Clin North Am. 1984;64:351–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Klinkosch JT. Divisionem Herniarum Novamgue Hernia Ventralis Proponit. Dissertationum Medicorum. 1764:184 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Spangen L. Spigelian hernia. World J Surg. 1989;13:573–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beluzzi V. Observazioni cliniche. Ernia di Spigelio strozzata contente lo stomaco. Policlinico Sez Prat. 1957;36:1151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Massabuau MM, Guibal et Cabanac A. Deux cas de hernies ventrales laterals spontanees etranglees: Presence du diverticule de Meckel dans une ces hernies. Arch Soc Med Biol Montpellier. 1933;14:340 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Benjamin RB, Webber RJ. Spigelian hernia. Bull St Louis Park Med Ctr. 1966;10:31 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jain KM, Hastings OH, Kunz VP, Lazaro FJ. Spigelian hernia. Am Surg.1977;43:596–600 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mathews FS. Hernia through the conjoined tendon. Ann Surg. 1923;78:300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Graver L, Bernstein D, Urbane CF. Lateral ventral (spigelian) hernias in infants and children. Surgery. 1978;83:228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lamb WK. Discussion of Hibbard IF, Schuman WR The spigelian hernia in gynecology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1962;83: 1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Holder LE, Schneider HJ. Spigelian hernias: anatomy and roentgenographic manifestations. Radiology. 1974;112:309–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arida EJ, Joh SK, Cucolo GF. The Spigelian hernia: radiographic manifestations. Br J Radiol. 1970;43:903–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hunter TB, Freundlich IM, Zukoski CF. Preoperative radiographic diagnosis of a spigelian hernia containing large and small bowel. Gastrointest Radiol. 1977;1:379–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gullmo A, Bromee A, Smedberg S. Herniography. Surg Clin North Am. 1984;64:229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nelson RL, Renigers SA, Nyhus LM, Sigel B, Spigos DG. Ultrasonography of the abdominal wall in the diagnosis of spigelian hernia. Am Surg. 1980;46:373–376 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Balthazar EJ, Subramanyam BR, Megibow A. Spigelian hernia: CT and ultrasonography diagnosis. Gastrointest Radiol. 1984;9:81–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Papierniak K, Wittenstein B, Bartizal JF, Wielgolewski JW, Love L. Diagnosis of spigelian hernia by computed tomography. Arch Surg. 1983;118:109–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zimmerman IM, Anson BJ. Anatomy and Surgery of Hernia, 2nd ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams and Wilkins; 1967:272–282 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Broughton G, Alvarez J. Repair of Spigelian hernias. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185(5):490–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moreno-Egea A, Carrasco L, Girela E, Martin JG, Aguayo JL, Canteras M. Open vs laparoscopic repair of spigelian hernia: a prospective randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2002;137:1266–1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Felix E, Michas C. Laparoscopic repair of spigelian hernias. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1994;4:308–310 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Amendolara M. Videolaparoscopic treatment of spigelian hernias. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1998;8:136–139 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fisher B. Video assisted spigelian hernia repair. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1994;4:238–240 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Teleky R, Duda M, Brezina L. Spigelian hernia and cholecystolithiasis treated laparoscopically. Rozhl Chir. 1999;78:610–612 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Strand L, Larsen J. Laparoscopic surgery of spigelian hernia. Ugeskr Laeger. 2002;164:1223–1224 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gedebou T, Neubauer W. Laparoscopic repair of bilateral spigelian and inguinal hernias. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1424–1425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. DeMatteo RR, Morris JB, Broderick G. Incidental laparoscopic repair of a spigelian hernia. Surgery. 1994;115:521–522 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barie P, Thompson WA, Mack CA. Planned laparoscopic repair of a spigelian hernia using a composite prosthesis. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1994;4:359–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Appeltans B, Zeebregts C, Cate Hoedemaker H. Laparoscopic repair of a spigelian hernia using an expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) mesh. Surg Endosc. 2000;14: 1189 Epub 2000 Sep 28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Carter J, Michas C. Laparoscopic diagnosis and repair of Spigelian hernias: Report of a case and technique. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:77–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Habib E, Elhadad A. Spigelian hernia long considered as diverticulitis: CT scan diagnosis and laparoscopic treatment. Computed tomography. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:159 Epub 2002 Oct 29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Iswariah H, Metcalf M, Morrison C, Maddern G. Facilitation of open Spigelian hernia repair by laparoscopic location of the hernia defect. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kasirajan K, Lopez J, Lopez R. Laparoscopic technique in the management of Spigelian hernia. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 1997;7:385–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tarnoff M, Rosen M, Brody F. Planned totally extraperitoneal laparoscopic Spigelian hernia repair. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:359 Epub 2001 Dec 10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Welter H. Laparoscopic management of a Spigelian hernia. Chirurg. 1994;65:898–899 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Novell F, Sanchez G, Sentis J, et al. Laparoscopic management of Spigelian hernia. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:1189 Epub 2000 Sep 20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Larson D, Farley D. Spigelian hernias: repair and outcome for 81 patients. World J Surg. 2002;26:1277–1281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]