Abstract

Determining the identity and distribution of molecular changes leading to the evolution of modern crop species provides major insights into the timing and nature of historical forces involved in rapid phenotypic evolution. In this study, we employed an integrated candidate gene strategy to identify loci involved in the evolution of flowering time during early domestication and modern improvement of the sunflower (Helianthus annuus). Sunflower homologs of many genes with known functions in flowering time were isolated and cataloged. Then, colocalization with previously mapped quantitative trait loci (QTLs), expression, or protein sequence differences between wild and domesticated sunflower, and molecular evolutionary signatures of selective sweeps were applied as step-wise criteria for narrowing down an original pool of 30 candidates. This process led to the discovery that five paralogs in the FLOWERING LOCUS T/TERMINAL FLOWER 1 gene family experienced selective sweeps during the evolution of cultivated sunflower and may be the causal loci underlying flowering time QTLs. Our findings suggest that gene duplication fosters evolutionary innovation and that natural variation in both coding and regulatory sequences of these paralogs responded to a complex history of artificial selection on flowering time during the evolution of cultivated sunflower.

DOMESTICATION by early farmers and improvement by modern breeders have dramatically transformed wild plants into today's crops, and these human-driven phenotypic changes are excellent models for studying the genetics of rapid evolutionary responses to natural selection. Investigations seeking the genetic basis of domestication and crop improvement traits generally fall into two categories: top-down and bottom-up approaches (Wright and Gaut 2005; Doebley et al. 2006; Ross-Ibarra et al. 2007; Burger et al. 2008). Top-down studies begin with phenotypic variation and use forward genetic methods to positionally clone genetic variants underlying quantitative trait loci (QTLs). Alternatively, association analyses, which exploit the fine-mapping resolution provided by the recombination history of natural populations or complex crosses, are performed for candidate genes with known involvement in traits of interest. Top-down approaches have identified genes contributing to domestication and improvement traits in several important crop species (e.g., Doebley et al. 1997; Frary et al. 2000; Thornsberry et al. 2001; Wang et al. 2005; Li et al. 2006; Simons et al. 2006; Cong et al. 2008; Jin et al. 2008; Tan et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2008; Xiao et al. 2008; Sugimoto et al. 2010) but have several limitations. Positional cloning is costly and labor-intensive, as QTL detection power and fine mapping require large numbers of recombinant individuals and genetic markers, and it may not be feasible for species with long generation times or that are vegetatively propagated. Population structure and bias or error in candidate gene choice can confound association studies.

Bottom-up studies search, on a genomic scale, for molecular evolutionary signatures of selective sweeps with the expectation that the identities of genes under selection and their sequence variants will eventually lead back to phenotypic variation. Genetic targets of selective sweeps exhibit reduced sequence variation relative to interspecific divergence when compared to neutrally evolving loci (Hudson et al. 1987; Wright and Charlesworth 2004). A localized signature of selection is evident because selection, unlike other evolutionary forces such as genetic drift and inbreeding, acts in a locus-specific manner. The timing of selection can also be examined by comparing diversity levels in wild progenitors, traditional landraces, and elite-bred cultivars (Burke et al. 2005). This approach has successfully identified genes that experienced selection during the domestication or improvement of maize (Vigouroux et al. 2002; Wright et al. 2005; Yamasaki et al. 2005, 2007; Hufford et al. 2007; Vielle-Calzada et al. 2009) and sunflower (Chapman et al. 2008), but was less effective for sorghum (Casa et al. 2005; Hamblin et al. 2006). Although these screens are unbiased because target loci are randomly selected with respect to function, homologs of many genes with known effects on traits of interest are often omitted by chance or in screens that assay simple sequence repeat (SSR) diversity because they lack SSRs. The functions of many included genes may be unknown; consequently, connecting genes that exhibit signatures of selective sweeps back to domestication or improvement traits is rarely straightforward.

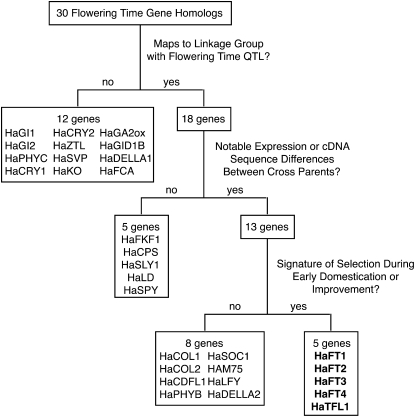

An alternative strategy is to synthesize information from both top-down and bottom-up methods (Figure 1). First, the genomic locations of genes homologous to those involved in a trait of interest in model species can be examined. The subset colocalizing with QTL intervals constitutes an excellent group of candidates, and additional criteria (e.g., coding sequence or expression differences between the cross parents) can be applied to build evidence supporting the candidacy of these genes. Molecular evolution analyses can then be applied to test whether these genes exhibit signatures of selection during a stage of crop evolution. While still beholden to preexisting knowledge, this strategy is not agnostic with respect to phenotype, integrates known details of genetic architecture and mechanistic context, and directs attention to evolutionarily relevant genes. This provides a sharpened focus in terms of genomic location, tissue, phenotype, and stage of crop evolution for subsequent functional and evolutionary confirmation.

Figure 1.—

Flowchart illustrating the criteria applied by integrated candidate gene approach and the serial refinement of the candidate gene pool.

Here, we present the results of such an integrated candidate gene approach in identifying genes involved in the evolution of flowering time during domestication and the improvement of cultivated sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Flowering time is a critical agronomic trait, and its evolution was crucial for the domestication and spread of many crop species into new climatic regions (Colledge and Conolly 2007; Fuller 2007; Izawa 2007). The gene regulatory network controlling flowering time is exceptionally well described, making it an excellent trait for candidate gene analysis. Many genes involved in flowering time regulation are known, and the molecular mechanisms through which environmental and endogenous cues are integrated to trigger the floral transition have been elucidated in many cases (Kobayashi and Weigel 2007; Farrona et al. 2008; Michaels 2008).

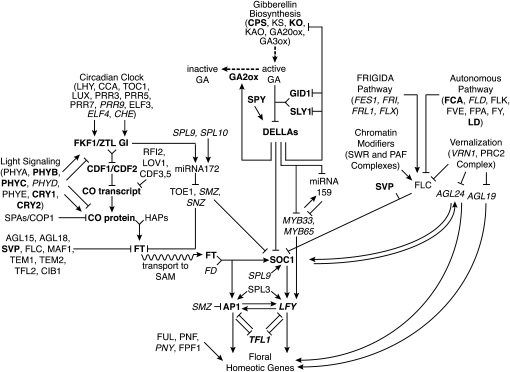

Plants assess photoperiod cues by integrating information received from the circadian clock and light cues. These signals jointly regulate the abundance of CONSTANS (CO) such that its transcript and protein accumulate and activate transcription of the floral inducer FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) only under inductive conditions (Figure 2; Suárez-López et al. 2001; Yanovsky and Kay 2002; Imaizumi et al. 2003, 2005; Valverde et al. 2004; Laubinger et al. 2006; Wenkel et al. 2006; Sawa et al. 2007; Jang et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2008b; Fornara et al. 2009; Adrian et al. 2010; Tiwari et al. 2010). FT expression is also promoted by circadian signals through a CO-independent pathway that represses FT repressors (Jung et al. 2007; Mathieu et al. 2009; Wu et al. 2009). FT protein travels from the leaf through the phloem to the shoot apical meristem (Corbesier et al. 2007; Jaeger and Wigge 2007; Lin et al. 2007; Mathieu et al. 2007; Tamaki et al. 2007; Shalit et al. 2009). There it induces the meristem integrators SUPRESSOR OF OVEREXPRESSION OF CONSTANS 1 (SOC1) and APETALA1 (AP1; Abe et al. 2005; Wigge et al. 2005; Yoo et al. 2005), which in turn promote expression of the meristem identity protein LEAFY (LFY) and initiate a signaling cascade of floral homeotic genes that pattern the floral meristem.

Figure 2.—

Sunflower contains homologs of many genes in the A. thaliana flowering time gene regulatory network. Regulatory relationships between genes as determined in A. thaliana are depicted. Junctions indicate protein complex formation, a dashed arrow indicates biosynthetic action, and a wavy arrow indicates protein transport between tissues. Genes without identifiable homologs in sunflower are italicized; genes with homologs genetically mapped in sunflower as part of this study are shown in boldface type.

Combinatorial regulation by internal and environmental signals occurs elsewhere in the flowering time gene regulatory network as well. Hormonal signals from gibberellic acid promote flowering by targeting the DELLA family proteins, repressors of SOC1 and LFY, for degradation while signals induced by abiotic stresses oppose these effects (Figure 2; Achard 2004; Dill et al. 2004; Strader et al. 2004; Ueguchi-Tanaka et al. 2005; Achard et al. 2006, 2007; Willige et al. 2007; Murase et al. 2008; Yamaguchi 2008; Schwechheimer and Willige 2009). Likewise, the FRIGIDA (FRI) pathway and endogenous chromatin-modifying complexes promote expression of the floral repressor FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) while other autonomous signals and external cues from the duration of overwintering, or vernalization, repress FLC expression. (Michaels and Amasino 1999; Levy et al. 2002; Michaels et al. 2003; Yu et al. 2004; Schönrock et al. 2006; Farrona et al. 2008; Lee et al. 2008; Li et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2008a; Michaels 2008).

Changes in flowering time coincide with major transitions in the evolution of cultivated sunflower. Sunflower was initially domesticated >4000 years ago from wild H. annuus populations in eastern North America (Heiser 1951; Rieseberg and Seiler 1990; Harter et al. 2004; Smith 2006). Over its history as a crop, sunflower experienced several periods of intense selection and population bottlenecks (Putt 1997; Tang and Knapp 2003), including its transformation in the mid-20th century by breeders into a globally important oilseed crop. While wild H. annuus populations range from early to late flowering (Heiser 1954), native American landraces are primarily late or very late flowering (Heiser 1951). In contrast, most elite-inbred modern cultivated lines are early flowering as a consequence of selection for shorter growing seasons during improvement (Goyne and Schneiter 1988; Goyne et al. 1989).

QTL studies performed on a landrace × wild H. annuus cross (Wills and Burke 2007) and an elite × wild H. annuus cross (Burke et al. 2002; Baack et al. 2008) have found that the genetic architecture of flowering time differences between wild and domesticated sunflower is oligogenic. In each case, one major and several minor flowering time QTLs were detected, and QTLs concordant between these crosses were detected in two regions. No sunflower domestication or improvement locus for flowering time has been positionally cloned. Although a recent bottom-up screen of 492 loci identified two selected genes that map to flowering QTLs and belong to gene families with flowering time regulators (Chapman et al. 2008), functional studies confirming a role of either gene in flowering have yet to be completed.

Here, we report our findings using an integrated strategy to study 30 sunflower homologs of flowering time regulators (Figure 1, Table 1). Specifically, we asked (1) whether any of these genes met multiple successive criteria highlighting them as strong candidate genes for domestication or improvement and (2) what the identity and distribution of molecular changes in these genes revealed about the timing and nature of selection on flowering time. This work extends and contextualizes findings reported in our recent study of the FT/TERMINAL FLOWER 1 (TFL1) family, which found functional and evolutionary support for a homolog of FT, HaFT1, as the gene underlying one of the two concordant QTLs (Blackman et al. 2010).

TABLE 1.

Sunflower homologs of flowering time genes

| Gene | Arabidopsis homolog | Arabidopsis locus ID | GenBank no.a | % IDb | % lengthc | Linkage group | Paneld | Closest marker |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photoperiod pathway | ||||||||

| HaFT1 | FT | AT1G65480 | DY917234 | 72.6e | 100 | 6 | 1 | ORS483 |

| HaFT2 | FT | AT1G65480 | EL485572 | 73.7e | 100 | 6 | 1 | ORS483 |

| HaFT3 | FT | AT1G65480 | — | 71.4e | 100 | 6 | 2 | ORS349 |

| HaFT4 | FT | AT1G65480 | EL482916 | 73.7e | 100 | 14 | 2 | HT765 |

| HaCOL1 | CO | AT5G15840 | — | 41.1e | 100 | 9 | 2 | ORS1155 |

| HaCOL2 | CO | AT5G15840 | DY912615 | 41.5e | 100 | 14 | 2 | HT842 |

| HaGI1 | GI | AT1G22770 | DY913818 | 71.3e | 100 | 11 | 3 | ORS228 |

| DY914731 | ||||||||

| HaGI2 | GI | AT1G22770 | EL438742 | 57.8f | 27 | 10 | 1 | CRT278 |

| HaCDFL1 | CDF1 | AT5G62430 | BU025202 | 37.0e | 100 | 7 | 1 | ORS331 |

| HaPHYB | PHYB | AT2G18790 | DY908939 | 78.2e | 60 | 1 | 2 | HT636 |

| HaPHYC | PHYC | AT5G35840 | EE622685 | 51.7f | 29 | 11 | 1 | HT555 |

| EE622732 | ||||||||

| HaCRY1 | CRY1 | AT4G08920 | CF081828 | 30.5f | 22 | 5 | 3 | ORS1153 |

| HaCRY2 | CRY2 | AT1G04400 | BQ970293 | 41.2f | 52 | 3 | 6 | ORS1114 |

| HaZTL | ZTL | AT5G57360 | BU034705 | 91.1f | 31 | 3 | 2 | HT745 |

| HaFKF1 | FKF1 | AT1G68050 | DY912573 | 74.9e | 100 | 17 | 2 | ZVG80 |

| Meristem integrators | ||||||||

| HaTFL1 | TFL1 | AT5G03840 | — | 68.0e | 100 | 7 | 1 | ORS331 |

| HaSOC1 | SOC1 | AT2G45660 | DY916215 | 60.7e | 100 | 6 | 1 | ORS1229 |

| HAM75 | AP1 | AT1G69120 | AF462152 | 55.6e | 100 | 8 | 2 | ORS744 |

| HaLFY | LFY | AT5G61850 | — | 61.6e | 100 | 9 | 1 | ORS844 |

| HaSVP | SVP | AT2G22540 | CD848608 | 54.9f | 100 | 5 | 1 | HT440 |

| CD848755 | ||||||||

| DY916321 | ||||||||

| Gibberellin pathway | ||||||||

| HaCPS | CPS | AT4G02780 | BQ917137 | 42.6e | 47 | 17 | 2 | ZVG80 |

| HaKO | KO | AT5G25900 | DY915145 | 54.3f | 48 | 5 | 5 | ORS694 |

| HaGA2ox | GA2ox | AT1G78440 | DY958114 | 55.3e | 100 | 11 | 4 | ORS005 |

| DY938012 | ||||||||

| DY938180 | ||||||||

| HaGID1B | GID1B | AT3G63010 | BQ970863 | 75.6f | 37 | 10 | 3 | HT960 |

| BU022119 | ||||||||

| HaSLY1 | SLY1 | AT4G24210 | AJ412362 | 50.0e | 100 | 9 | 1 | HT294 |

| HaDELLA1 | RGA | AT2G01570 | BU028290 | 59.6f | 100 | 12 | 4 | ORS167 |

| BQ912776 | ||||||||

| BQ913059 | ||||||||

| DY948837 | ||||||||

| DY916832 | ||||||||

| HaDELLA2 | GAI | AT1G14920 | CD849186 | 64.1e | 29 | 17 | 2 | ORS625 |

| CD850340 | ||||||||

| HaSPY | SPY | AT3G11540 | BQ969439 | 67.3e | 37 | 6 | 3 | ORS516 |

| Autonomous pathway | ||||||||

| HaFCA | FCA | AT4G16280 | DY906794 | 13.5f | 92 | 13 | 1 | ORS534 |

| HaLD | LD | AT4G02560 | EL450845 | 39.8e | 39 | 4 | 2 | ORS1239 |

GenBank accession numbers for sunflower EST sequences used for design of mapping primers.

Percentage amino acid identity to A. thaliana protein sequence.

Percentage of the full A. thaliana cDNA covered by cDNA sequences from Ann1238 or EST sequences.

Numeric code for mapping panels used to place genes on genetic map is as follows: (1) Hopi × Ann1238 F2, (2) NMS373 × Ann1811 BC1, (3) RHA280 × RHA801 RIL, (4) CMSHA89 × Ann1238 F3, (5) PHC × PHD RIL, and (6) NMS801 × Arg1803 F1.

Calculated using cDNA sequence obtained during this study from Ann1238.

Calculated using EST sequence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ortholog identification:

A list of genes with demonstrated involvement in regulation of flowering time in Arabidopsis was compiled from the literature (Figure 2), and the Helianthus expressed sequence tag (EST) collections generated by the Compositae Genome Project were screened for homologs of these genes. Initial EST library content and methods of library construction, sequencing, and assembly are described in Heesacker et al. (2008). Subsequent library construction and sequencing have produced new EST collections for H. ciliaris, H. exilis, and H. tuberosus. All results reported are based on the EST assemblies available at http://cgpdb.ucdavis.edu/asteraceae_assembly. Homologs of flowering time genes, MADS-box genes, and CONSTANS-like (COL) genes were identified by searching a report of top BLASTx hits of the H. annuus EST assembly to Arabidopsis thaliana proteins by The Arabidopsis Information Resource locus ID number. When searching the H. annuus report did not yield any homologs, reports for additional Helianthus species were searched.

The sunflower EST collection has grown incrementally since the beginning of this project, and early releases did not contain homologs of many key flowering time genes. Therefore, PCR and hybridization-based methods were employed to obtain these genes. Acquisition of the four HaFT homologs has been described (Blackman et al. 2010). Partial sequences of HaGI and HaTFL1 were obtained with degenerate primers designed for alignments of homologs from other species in GenBank (supporting information, Table S1). Previously published degenerate primers successfully amplified partial sequences of HaLFY (Aagaard et al. 2006) and HaCOL2 (Hecht et al. 2005). Partial sequence of HaSOC1 was obtained with primers designed for a Chrysanthemum × morifolium SOC1-like sequence (GenBank accession no. AY173065). The H. annuus cultivated line HA383 BAC library generated by the Clemson University Genome Institute was then screened with radioactively labeled overgo probes (Ross et al. 2001) designed for HaCOL2, HaSOC1, and HaTFL1 partial sequences (Table S1). These screens resulted in identification of genomic clones containing full-length HaCOL1, HaSOC1, and HaTFL1. Full-length sequences of HaCOL2, HaGI, and HaLFY were acquired by assembly with sequences from subsequently available ESTs, thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR, and 5′ and 3′ RACE.

Genetic mapping:

Map positions were obtained for 30 candidate genes by genotyping markers on subsets of one of six mapping panels: 94 of 214 NMS373 × (NMS373 × Ann1811) BC1 individuals (Gandhi et al. 2005); 96 of 378 Hopi × Ann1238 F2 individuals (Wills and Burke 2007); 96 of 374 CMSHA89 × Ann1238 F3 individuals (Burke et al. 2002); 48 of 94 RHA280 × RHA801 recombinant inbred lines (RILs) (Tang et al. 2002; Lai et al. 2005); 94 of 262 PHC × PHD RILs (S. Knapp, unpublished results); and 94 of 94 NMS801 × Arg1805 F1's (Heesacker et al. 2009). Portions of the genes were amplified by PCR with gene-specific primers (Table S1). Parental DNAs or a subset of progeny of each mapping panel were initially screened for polymorphisms by sequencing. For most of the polymorphic candidate genes, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were then scored on a mapping panel by denaturing high performance liquid chromatography analysis carried out on a WAVE nucleic fragment analyzer (Transgenomic) using a DNASep HT Column as described previously (Lai et al. 2005). An SSR in HaGID1B was mapped by assaying length polymorphism of fluorescently labeled PCR products on an Applied Biosystems 3730xl sequencer as previously described (Burke et al. 2002). HaFT3, HaSVP, HaLFY, and HaGA2ox PCR products were directly sequenced. Linkage mapping was performed with MAPMAKER 3.0/EXP (Lander et al. 1987).

Gene expression analysis:

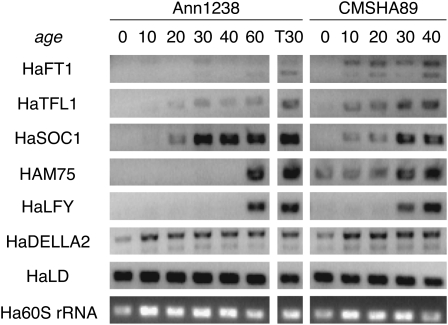

To survey candidate gene expression in leaf tissue, wild accession Ann1238 and elite line CMSHA89 were grown at 25.5° in growth chambers under short days (8 hr light, 16 hr dark) or long days (16 hr light, 8 hr dark). At 30 days after sowing, leaf tissue was collected every 4 hr from dawn to 20 hr after dawn. To survey expression in shoot apices, Ann1238 and CMSHA89 plants were grown in long-day conditions, and shoot apices were collected from germinated seedlings before sowing and from seedlings at 10, 20, 30, and 40 days after sowing. Shoot apices were collected from Ann1238 only at 60 days after sowing as well. Some Ann1238 plants were also transferred from long days into short days at 20 days after sowing, and shoot apices were collected from these plants 10 days after transfer. In both the leaf and shoot apex collections, three biological replicates were taken at each time point or developmental age, and samples from three plants were pooled within each replicate.

RNA was isolated with the Spectrum Plant Total RNA Kit (Sigma) and treated with On-Column DNase (Sigma) during extraction. Shoot apex RNA samples were further cleaned and concentrated with an RNeasy MinElute Cleanup Kit (Qiagen). RNA was converted to cDNA with SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen), and gene-specific primers (Table S1) were used to amplify candidates by PCR. PCR on leaf cDNA was carried out in 20-μl reactions with Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen) run for 30 cycles for all candidate genes and for 26 cycles for a control gene, Ha60S rRNA. PCR of shoot apex cDNA was carried out for 32 cycles for HaFT1 and HaSOC1; 30 cycles for HaTFL1, HAM75, HaLFY, HaDELLA2, and HaLD; and 28 cycles for Ha60S rRNA. PCR product concentrations were visualized on 1% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide.

cDNA sequencing:

Gene-specific primers were designed to the 5′ and 3′ ends of the candidate genes mapping to linkage groups (LGs) with flowering time QTLs, and full-length coding sequences were amplified by PCR from Ann1238 and CMSHA89 leaf or shoot apex cDNAs (Table S1). For candidate genes where alignments of ESTs or otherwise-isolated sequences did not cover the entire coding sequence, 5′ and 3′ RACE was performed to try to isolate the remaining sequence. If this was unsuccessful, primers were designed to the largest possible portion of the gene. In most cases, full-length sequence could be obtained from first-strand cDNA generated by reverse transcription (RT) reactions primed with an oligo(dT) primer. However, particularly for long or low-abundance transcripts, RT reactions primed with gene-specific primers targeted to the 3′-UTR were required to acquire a cDNA substrate amenable to full-length cDNA amplification by PCR. The number of PCR cycles and duration of extension time were increased for genes of large size or low transcript abundance.

Molecular evolution analyses:

Portions of candidate genes and seven putatively neutral control loci were amplified by PCR and sequenced using gene-specific primers (Table S1) on a diversity panel of wild and domesticated H. annuus. This panel included 18 individuals from elite inbred lines, 19 individuals from native American landraces, 23 individuals from a geographically diverse sample of wild H. annuus populations, and 6 individuals from H. argophyllus (Table S2). Although H. argophyllus has been isolated for ∼1.1 million generations from H. annuus, due to H. annuus' large effective population size, incomplete lineage sorting may affect divergence estimates because some shared polymorphisms may be confounded with fixed differences (Strasburg et al. 2009). PCR fragments from heterozygous individuals were cloned (TOPO TA cloning, Invitrogen) and sequenced with T7 and T3 primers. Multiple clones were sequenced per individual, compared with each other, and compared to the original direct sequencing reads to detect and eliminate errors introduced during PCR and cloning. Seven putative neutral reference loci (Table S3) were chosen because they were shown to be evolving neutrally (Liu and Burke 2006) or because they had the most complete sequence information available from an ongoing study of sequence diversity by the Compositae Genome Project. A multi-locus Hudson–Kreitman–Aguadé (HKA; Hudson et al. 1987) test demonstrated that sequence diversity of the seven reference loci did not deviate from a strictly neutral evolutionary model (http://genfaculty.rutgers.edu/hey/software#HKA).

Diversity parameters—number of segregating sites (S), number of haplotypes (h), pairwise nucleotide diversity (π), and Watterson's estimator of diversity (θw)—were calculated with DnaSP (Rozas et al. 2003). DnaSP was also used for synonymous substitution rate calculations between paralogs. MLHKA (Wright and Charlesworth 2004) was used to conduct maximum-likelihood HKA tests. For each candidate gene, likelihoods for a strictly neutral model and a model where the candidate was under selection were calculated and compared with a likelihood-ratio test. To examine the timing of selection, separate tests were conducted for elite, landrace, and wild samples.

RESULTS

Flowering time gene homologs in sunflower:

Our analysis of the Helianthus EST collections revealed that most flowering time genes identified in model plant species have homologs in sunflower (Figure 2). For the 30 genes pursued as potential candidates, GenBank accession numbers for contributing ESTs, percentage amino-acid identity to A. thaliana homolog, and percentage of the total protein sequence obtained are reported in Table 1. Information for all genes not involved in subsequent analyses is summarized in Table S4. Phylogenetic analyses conducted to more specifically identify homologs in two large gene families—CONSTANS LIKE (COL) genes and type II MADS-box transcription factors—are described in File S1, Figure S1, Figure S2, Table S5, and Table S6.

In total, the H. annuus EST collection (93,428 sequences) contained just over half the genes in our search (82 of 155 total). Expanding our search to the EST collections of related sunflower species (189,585 additional sequences) led to the identification of homologs of 31 additional genes. Sunflower homologs were identified for genes throughout the flowering time gene regulatory network, including genes that function in the circadian clock, light reception, CO-dependent and CO-independent photoperiod pathways, gibberellin biosynthesis and signaling, the autonomous pathway, vernalization response, chromatin modification, and meristem integration (Figure 2). The absence of ESTs homologous to any FRI pathway genes was a notable exception.

Several causes may have contributed to the absence of sunflower EST homologs of certain genes. Homologs were not expected for genes like PHYTOCHROME D that arose by duplication events in lineages not ancestral to sunflower (Mathews and Sharrock 1997). Insufficient library sequencing depth or incomplete sampling of particular cell types, developmental stages, circadian time points, or environmental conditions may also have produced gaps in coverage. For example, absence of several critical flowering genes expressed in the shoot apical meristem during floral induction (MYB33, MYB65, LFY, TFL1, and FD) signals that samples used for EST library construction were impoverished for this tissue.

In several cases, multiple Helianthus copies were found of genes present as a single copy in Arabidopsis, e.g., GIGANTEA (GI), FLAVIN-BINDING. KELCH REPEAT, F-BOX 1 (FKF1), and ZEITLUPE (ZTL). Recent gene family expansion has also been described for the FT/TFL1 family (Blackman et al. 2010). Some of these expansions likely result from persistence of duplications that arose during polyploidy events at the base of the Compositae or, more recently, within the Heliantheae (Barker et al. 2008). For example, values of Ks, the synonymous substitution rate between two sequences, for sunflower duplicate pairs of ZTL and FKF1 were 0.71 and 0.66, respectively, consistent with the former event; Ks was 0.45 for one of the duplication events in the sunflower FT clade, consistent with the latter event.

Although describing sunflower type II MADS-box gene diversity was not our principal aim, the involvement of many of these genes in flowering required more rigorous evaluation of orthology with a phylogeny. Although we limited our analysis to H. annuus ESTs and excluded several incomplete sequences, sunflower orthologs clustered in all major MADS-box clades except AGL12 and GGM13 (Figure S2; Becker and Theissen 2003), including sequences related to SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE (SVP), SOC1, FRUITFULL (FUL), AP1, and FLC. FLC and the MADS AFFECTING FLOWERING (MAF) genes were once suspected of being a Brassicaceae-specific clade (De Bodt et al. 2003). However, recent work has determined that FLC homologs are present in diverse eudicots and can act as cold-repressed regulators of flowering (Hileman et al. 2006; Reeves et al. 2007). While temperature's influence on flowering in sunflower is well documented (Goyne and Schneiter 1988; Goyne et al. 1989), to our knowledge there is no evidence of vernalization sensitivity. FLC also regulates seed germination in A. thaliana (Chiang et al. 2009), and this function could be conserved. Therefore, the functional importance of this FLC homolog and its regulators requires further investigation.

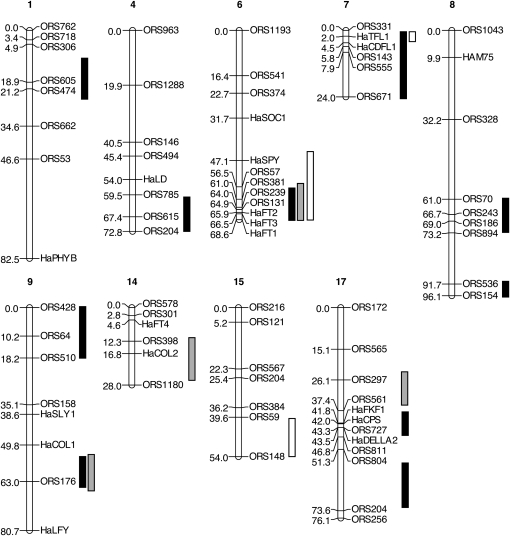

Defining candidates by mapping:

As a first criterion for choosing flowering time homologs as candidate domestication or improvement genes, we tested whether genes colocalized with previously identified flowering time QTLs (Burke et al. 2002; Wills and Burke 2007; Baack et al. 2008). Markers polymorphic in one of the six mapping panels available to us were identified (Table 1, Figure 2); of the 30 genes mapped, 18 mapped to LGs containing flowering time QTLs (Figure 3). These genes included representatives from throughout the gene regulatory network. QTLs for flowering time have been detected in just over half (9 of 17) of the LGs in the H. annuus genome in previous crosses between wild and domesticated sunflower, and these QTLs, when projected onto the same genetic map, cover ∼15% of the genome (148.2 cM/972.6 cM map from Burke et al. 2002). Nine of our 30 candidates (30%) unambiguously colocalized with QTLs, suggesting that these regions may be enriched for flowering time genes.

Figure 3.—

Relative positions of candidate genes and flowering time QTLs on the sunflower genetic map (Burke et al. 2002). QTL positions and candidate gene positions were approximated by homothetic projection from markers concordant between multiple mapping populations as performed in BioMercator (Table S7; Arcade et al. 2004). The Burke et al. (2002) map was chosen as a framework since the most flowering QTLs and several candidate genes were mapped in this population. Only the 9 LGs containing flowering time QTLs of the 17 LGs in sunflower are shown. QTL regions, shown as 1-LOD intervals and detected in an elite × wild population in the greenhouse (Burke et al. 2002) and the wild (Baack et al. 2008), are shown as solid and shaded bars, respectively. QTL regions detected in a landrace × wild population grown in the greenhouse (Wills and Burke 2007) are shown as white bars.

In some cases, QTL chromosomal blocks and gene locations clearly overlapped, whereas in other cases candidate genes and QTLs did not overlap or the coincidence was ambiguous (Figure 3). For example, HaPHYB mapped to the opposite end of LG1 from the QTL region. The locations of HaFT1, HaFT2, and HaFT3 coincided with the LG6 chromosomal block in which a QTL was detected in all three previous QTL studies; HaSOC1 and HaSPY also map to LG6 but fall outside the concordant region. HaCDFL1 (also mapped as c1921 in Chapman et al. 2008) and HaTFL1 mapped to positions similar to QTLs on LG7. Relative positioning of QTL and genes on the remaining linkage groups was less certain. LG15 was the only group with a flowering time QTL to which no flowering time gene homologs mapped. Notably, this is also the only QTL found in the cross between wild H. annuus and a native American landrace but not in the cross of wild H. annuus and an elite-bred line.

Although we could confidently assign genes to LGs, ambiguity in determining whether a gene and QTL were truly colocalized arose from several sources. Since different markers were used in the construction of each of the six mapping panels and only two of the panels were used for QTL detection, approximate map locations of the candidate genes and QTLs were often inferred from the relatively few markers common to more than one mapping panel. Inconsistent ordering of markers on different panels compounded this issue. The map with the most QTLs (Ann1238 × CMSHA89 F3's; Burke et al. 2002) partly consisted of dominant markers, leading to uncertainties in marker ordering, potential false splitting of single QTL into multiple QTLs, and some large confidence intervals around QTL peaks that often spanned half to all of a LG. Finally, variation in marker density among LGs and panels may have affected the breadth of QTL confidence intervals. Due to these sources of uncertainty, we conservatively designated all 18 genes located on LGs with flowering time QTL as preliminary candidates.

Expression and sequence surveys of candidates:

Next, we winnowed down our preliminary candidate gene pool by surveying for notable differences in expression or protein sequence between parents of the elite × wild cross used to develop two of the three QTL panels. The domesticated parent was inbred line CMSHA89 (Figures 4 and 5, Table 2). The wild parent of this cross, Ann1238, came from a population near Cedar Point Biological Station (Rural Ogallala, NE). Individuals of this population have a short-day-sensitive photoperiod response in flowering, unlike CMSHA89, which is long-day-sensitive and flowers earlier than Ann1238 in both inductive and non-inductive photoperiods (Blackman et al. 2010). Since no genes mapped to the LG containing the single QTL unique to the landrace × wild panel (Wills and Burke 2007), we did not include the landrace parent of that panel in our analysis.

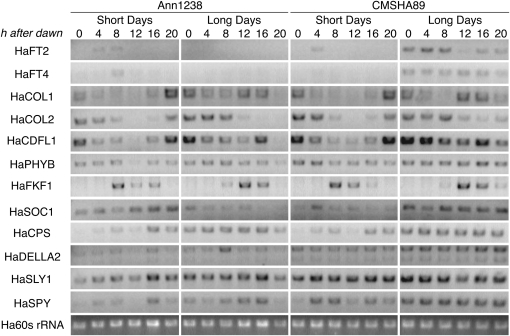

Figure 4.—

Comparison of candidate gene expression patterns in leaf tissue between parent populations of an elite × wild QTL cross. Expression was assayed by RT–PCR in leaves collected every 4 hr starting at dawn over the course of a day from wild (Ann1238) and elite (CMSHA89) plants raised in long days and short days for 30 days after sowing. Data from one of three biological replicates are shown.

Figure 5.—

Comparison of candidate gene expression patterns in shoot apex tissue between parent populations of an elite × wild QTL cross. Expression was assayed by RT–PCR in shoot apices collected over a developmental time course for wild (Ann1238) and elite (CMSHA89) plants raised in long days. Plants were sown at day 0 and collection occurred every 10 days until day 40 for both lines. A collection at 60 days was also conducted for Ann1238. In addition, some Ann1238 plants (T30) were transferred from long days to short days at 20 days, and shoot apices were collected from these plants on day 30. Data from one of three biological replicates are shown. HaFT1 data are from Blackman et al. (2010).

TABLE 2.

Nucleotide changes present in cross parent accession coding sequences

| Differences between Ann1238 and CMSH89 |

Polymorphisms within Ann1238 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Synonymous | Replacement | Insertion/Deletion | Synonymous | Replacement | Insertion/Deletion |

| HaFT1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 0 |

| HaFT2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HaFT4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| HaCOL1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 2 |

| HaCOL2 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 1 |

| HaCDFL1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 0 |

| HaPHYB | 9 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 5 | 0 |

| HaFKF1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 0 |

| HaTFL1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| HaSOC1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| HAM75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| HaLFY | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 3 | 0 |

| HaCPS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 10 | 0 |

| HaSLY1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| HaDELLA2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HaSPY | 2 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 0 |

| HaLD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

Expression of candidates was assayed by RT–PCR in leaf and/or shoot apex tissue, depending on the gene's expression domain(s) in other species. Since many photoperiod pathway genes are controlled by the circadian clock and since the parents differ in photoperiod response, we surveyed gene expression in leaf tissue in plants raised in short days and long days, taking samples every 4 hr over the course of a single day (Figure 4). For the survey of shoot apex expression, we observed transcript levels over a developmental time course in long days, allowing us to look at the relative timing of upregulation of candidates during growth (Figure 5). Expression in the shoot apices was also examined for a set of Ann1238 individuals transferred to short days—this population's inductive photoperiod—for 10 days.

We assayed expression differences between the parents as a proxy for functionally important cis-regulatory sequence variants. While we expect that this served as a reliable indicator, two situations may have arisen where this was not the case. First, expression differences may have been too subtle to detect by RT–PCR or occurred in conditions not surveyed. Second, the parents may have identical expression patterns yet differ by compensatory sequence changes. Consequently, transgressive variation in gene expression, and potentially in flowering time, could have segregated in hybrids. Although missing such genes may have led us to discard candidates underlying particular QTLs, attrition of our primary search targets—genes responsible for phenotypic differences that experienced directional selection during the evolution of cultivated sunflower—is unlikely.

The entire coding region or the largest partial sequence possible (Table 1) was amplified from Ann1238 and CMSHA89 leaf or shoot apex cDNA for 17 of the 18 preliminary candidates. Previous work found that HaFT3 is not expressed, but previously characterized loss-of-function mutations were genotyped from genomic DNA (Blackman et al. 2010).

Both expression and sequence differences:

Of the 18 preliminary candidates, two exhibited expression and protein sequence differences. As previously reported (Blackman et al. 2010), the domesticated allele of HaFT1 contains a 1-bp deletion in the third exon that causes a frameshift and extension of the protein by 17 amino acids. HaFT1 is expressed at very low levels in Ann1238 plants raised in long days but is upregulated on transfer to short days. In contrast, HaFT1 is upregulated in long days in CMSHA89 as soon as 10 days after sowing.

In both leaf and shoot apex tissue, HaSOC1 expression differed. In Ann1238, HaSOC1 was upregulated at most times of day in leaves of plants raised in short days relative to leaves of plants raised in long days, but the opposite pattern was observed in CMSHA89. Shoot apex expression of HaSOC1 also started earlier in development in CMSHA89 than in Ann1238. A SNP causing a histidine-to-glutamine substitution in the K-box domain of HaSOC1 was also found in CMSHA89. Due to these differences, HaFT1 and HaSOC1 retained candidate gene status.

Sequence differences only:

Five genes showed no notable differences in the timing or abundance of gene expression consistent across all biological replicates, but they did have replacement substitutions or insertion/deletion mutations between Ann1238 and CMSHA89.

HaCOL1 had three in-frame insertion/deletion differences: a 6-bp insertion polymorphic in Ann1238, a 24-bp insertion in CMSHA89, and an SSR, which is polymorphic in Ann1238 but always contains more repeats than in CMSHA89. The two lines also differed by two replacement substitutions in HaCOL1 that both cause replacement of a histidine in Ann1238 with a glutamine in CMSHA89. Two nonconservative amino-acid changes—a secondary structure-altering serine-to-proline substitution and a charge-changing lysine-to-phenylalanine substitution—distinguished the HaCOL2 sequences of Ann1238 and CMSHA89. None of the mutations in HaCOL1 or HaCOL2 were in either of the two B-box domains or the CCT domain.

Although we opted to keep HaCOL1 and HaCOL2 designated as candidate genes on the basis of these notable mutations, changes in the remaining three genes were not dramatic enough to merit continued study. Two substitutions were found in HaFKF1 (serine to tyrosine; aspartic acid to valine): one in an unconserved residue of the PAS domain and the other in the fifth KELCH domain. Ann1238 and CMSHA89 HaSLY1 protein sequences differed only by a glutamic acid to aspartic acid substitution in the unconserved 5′ region. Finally, the two lines differed by a serine-to-glutamine substitution in the unconserved 3′ end of HaSPY. Although these substitutions appear conservative, the possibility that they have phenotypic effects cannot be excluded.

Of the four previously discovered nonfunctionalizing mutations in HaFT3 (Blackman et al. 2010), none were present in Ann1238 and one was present in CMSHA89, a 7-bp frameshift mutation in the fourth exon. In that study, lack of expression of HaFT3 in Ann1238 was also demonstrated for all tissues tested. Even so, we retained HaFT3 in our candidate list.

Expression differences only:

Eight genes exhibited differences in expression but had no differences in protein sequence. In the leaf, HaFT2 and HaFT4 showed expression patterns consistent with the divergence in photoperiod response between the two parents. Both were expressed only in short days in Ann1238 and only in long days in CMSHA89 (Figure 4), although one CMSHA89 replicate (shown) had a small peak of HaFT2 expression in short days. In CMSHA89, transcript abundances of both genes appeared higher in the inductive photoperiod at all times of day as well, a result quantitatively confirmed for HaFT2 previously (Blackman et al. 2010).

For HaCDFL1, HaPHYB, and HaDELLA2, timing of expression in each photoperiod was similar, but expression levels appeared higher at most or all time points in CMSHA89 than in Ann1238 (Figure 4). Similar to HaFT1, HAM75 and HaTFL1 are expressed at very early developmental stages in CMSHA89 shoot apices in long days; expression of both genes increases only later in development in Ann1238 plants under long days or upon transfer to short days (Figure 5). HaLFY is also expressed earlier in development in long days in CMSHA89 than in Ann1238, although expression was shifted earlier when Ann1238 was transferred to short days.

Although some of the expression differences observed may be partially or wholly caused by trans-acting changes in upstream factors, we cannot rule out contributions of cis-regulatory changes. Consequently, all eight genes were kept as candidates for further study.

No expression or sequence differences:

HaCPS and HaLD showed no differences in expression (Figures 4 and 5) between Ann1238 and CMSHA89 consistently across all biological replicates, and no cDNA sequence differences were found (Table 2). Therefore, candidate status was revoked for these genes.

Signatures of selection on refined candidate set:

We next conducted MLHKA tests on the remaining 13 candidate genes to determine whether these genes were under selection during early domestication or crop improvement (Wright and Charlesworth 2004). Portions of the candidate genes and seven putative neutral reference genes were sequenced on a panel of elite-bred cultivars, native American landraces, and wild H. annuus (Table S2). Several individuals of H. argophyllus, H. annuus' sister species, were sequenced to obtain divergence measures.

Levels of diversity in the reference genes in wild, landrace, and elite lines were comparable to levels found in previous work (Table 3; Liu and Burke 2006; Kolkman et al. 2007; Chapman et al. 2008). Also as in previous studies, average pairwise nucleotide diversity (π) and average Watterson's estimator of diversity (θw) were highest in the wild populations, intermediate in the landraces, and lowest in the elite lines, indicative of genetic bottlenecks at both the domestication and improvement stages (Table 3; Burke et al. 2005; Liu and Burke 2006; Chapman et al. 2008). A similar progressive drop in diversity with each stage of crop evolution was observed for the candidate genes.

TABLE 3.

Average sequence diversity values for candidate and reference genes

| Diversity statistics | Elites | Landraces | Wilds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate genes (13 loci) | |||

| n | 35.7 (0.3) | 37.9 (0.2) | 44 (0.9) |

| L | 686.3 (30.9) | 683.9 (30.9) | 671.5 (32.2) |

| S | 6.6 (2.1) | 14.9 (3.3) | 43.5 (6.4) |

| h | 2.4 (0.3) | 7.5 (1.1) | 23.6 (1.8) |

| π | 0.0026 (0.0010) | 0.0056 (0.0013) | 0.0101 (0.0013) |

| θw | 0.0024 (0.0007) | 0.0053 (0.0012) | 0.0149 (0.0021) |

| Reference genes (7 loci) | |||

| n | 36 (0.0) | 38 (0.0) | 46 (0.0) |

| L | 601.1 (38.6) | 593.6 (40.4) | 608 (41.9) |

| S | 12.43 (1.2) | 24.71 (4.3) | 51.17 (6.5) |

| h | 4.714 (0.9) | 12 (2.4) | 31.5 (2.9) |

| π | 0.0056 (0.0010) | 0.0095 (0.0013) | 0.0129 (0.0018) |

| θw | 0.005 (0.0006) | 0.01 (0.0016) | 0.02 (0.0028) |

Parameters listed include the average number of sequences (n), average sequence length (L), average number of segregating sites (S), average number of haplotypes (h), average pairwise nucleotide diversity (π), and average Watterson's estimator of diversity (θw). Values in parentheses are standard errors.

In an MLHKA test, the likelihood of a strictly neutral model is compared to the likelihood of a model where a candidate gene is under selection. For each gene, separate tests were performed for elite, landrace, and wild sequence data sets to determine the timing of selection. Five of the 13 candidate genes tested had significant MLHKA tests indicative of selection occurring during domestication or improvement (Table 4). As previously reported (Blackman et al. 2010), sequence variation in HaFT1 was consistent with neutral evolution in wild H. annuus, but consistent with selection in landraces and elite lines. Notably, all additional members of the FT/TFL1 family tested had significant signatures of selection in elite lines but not for wild or landrace data sets. HaFT2, HaFT3, and HaFT4 sequences were identical in all elite lines. A 1-bp indel polymorphism in a homopolymer run of adenines present in just a single line was the only SNP segregating in HaTFL1 in elite lines.

TABLE 4.

Results of MLHKA tests for selection on candidate genes

| MLHKA P-values |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Elites | Landraces | Wilds | Timing of selectiona |

| HaFT1 | 0.014* | 0.045* | 0.468 | Domestication |

| HaFT2 | 0.001*** | 0.123 | 0.895 | Improvement |

| HaFT3 | 0.001*** | 0.086 | 0.475 | Improvement |

| HaFT4 | 0.001** | 0.122 | 0.728 | Improvement |

| HaCOL1 | 0.906 | 0.839 | 0.961 | — |

| HaCOL2 | 0.330 | 0.533 | 0.944 | — |

| HaCDFL1 | 0.909 | 0.922 | 0.616 | — |

| HaPHYB | 0.075 | 0.876 | 0.764 | — |

| HaTFL1 | 0.001*** | 0.103 | 0.914 | Improvement |

| HaSOC1 | 0.841 | 0.914 | 0.931 | — |

| HAM75 | 0.813 | 0.548 | 0.737 | — |

| HaLFY | 0.495 | 0.480 | 0.758 | — |

| HaDELLA2 | 0.909 | 0.968 | 0.859 | — |

| 7 reference locib | 0.517 | 0.600 | 0.207 | |

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Defined on the basis of the interpretation of MLHKA P-values.

P-values for reference loci are reported for HKA results (see materials and methods).

DISCUSSION

Multiple FT/TFL1 family members emerge as strong candidates:

By integrating information gained from both top-down and bottom-up analyses, we identified several strong candidate domestication and improvement genes affecting flowering time (Figure 1). Of the genes pursued, 17% (5/30) exhibited signatures of selection during a stage of cultivated sunflower evolution. Notably, all of these candidates are FT/TFL1 homologs.

HaFT1, HaFT2, and HaFT3 mapped to a large QTL on LG6 that is concordant between elite × wild and landrace × wild crosses and explains 7.6–36% of the variance in flowering time, depending on the cross (Burke et al. 2002; Wills and Burke 2007; Baack et al. 2008). Additional analyses published elsewhere (Blackman et al. 2010) provide strong support for HaFT1 as the genetic cause of this QTL. Involvement of HaFT3 is unlikely, as it is nonfunctionalized. The domesticated allele delays flowering in near isogenic lines (NILs) segregating for this QTL region, and although cis-mapping differences affecting HaFT2 expression were found, they were inconsistent with this result as higher expression of the CMSHA89 allele would be predicted to promote earlier flowering. In contrast, the domesticated allele of HaFT1 contains a frameshift mutation consistent with the NIL phenotypes, provided the mutation has dominant negative action. Transgenic analyses in A. thaliana confirmed this by demonstrating that the domesticated allele of HaFT1 suppresses complementation of late-flowering ft mutants by HaFT4 while the wild allele does not (Blackman et al. 2010).

HaTFL1 mapped to a minor QTL on LG7 concordant between both landrace × wild and elite × wild crosses (Burke et al. 2002; Wills and Burke 2007); however, HaTFL1 exhibited a signature of selection during improvement but not early domestication. This discrepancy may be explainable if the domesticated parent in the landrace × wild panel carried a functionally equivalent haplotype as the domesticated parent in the elite cross. Alternatively, the QTL may have complex genetic underpinnings.

A recent SSR-based screen identified two other putative flowering time gene homologs in this interval with signatures of selection during improvement (Chapman et al. 2008); however, we consider HaTFL1 to be the best-supported individual candidate. One gene, c1921, is the same gene as HaCDFL1 from our analysis, but in our diversity panel no signature of selection in elite lines was apparent. The larger size of our study (24 more elite haplotypes) likely allowed better sampling of low-frequency alleles, explaining this discrepancy.

The other gene, c2588, belongs to the same gene family as INDETERMINATE1/EARLY HEADING DATE2 (ID1/Ehd2), a zinc-finger transcription factor and upstream regulator of FT homologs in monocots (Colasanti et al. 1998; Matsubara et al. 2008). While TFL1 homologs regulate flowering and other photoperiodic responses across diverse plants (Bradley et al. 1997; Pnueli et al. 1998; Nakagawa et al. 2002; Foucher et al. 2003; Guo et al. 2006; Danilevskaya et al. 2008; Ruonala et al. 2008; Mimida et al. 2009), the function of ID1/Ehd2 homologs in flowering may be monocot-specific. No direct ID1/Ehd2 ortholog exists in the A. thaliana genome, and phylogenetic analyses indicate the INDETERMINATE gene family independently diversified in the monocot and eudicot lineages (Colasanti et al. 2006).

Both HaFT4 and HaCOL2 map to LG14, where a flowering time QTL was detected only in the elite × wild cross and only in field-raised plants (Baack et al. 2008). While HaCOL2 falls within the QTL, HaFT4's relative position is ambiguous on the basis of shared markers, and it may fall outside the QTL region. Nonetheless, HaFT4 exhibits a signature of selection with improvement and HaCOL2 does not, making HaFT4 the better candidate improvement gene.

In terms of the genes potentially identifiable through our strategy, we have identified candidates under selection mapping to flowering time QTLs on 33% (3/9) of LGs with QTLs. Not all of the genes underlying detected QTLs are expected to have experienced the same selective pressures during either domestication or improvement, however. Genetic variation for flowering has been detected in crosses between elite lines (Leon et al. 2000, 2001; Bert et al. 2003), and different lines may have different recent histories of selection on flowering time by farmers in different geographic regions. This scenario would increase diversity and obscure a signature of selection. Since QTL analysis of flowering time has been conducted only in a single elite × wild cross, improvement-specific QTLs and line-specific QTLs cannot be distinguished. As a result, some CMSHA89 × Ann1238 cross-specific QTLs may be due to functional variants in candidates that we identified by mapping, expression, and sequence analyses that did not show signatures of selection (e.g., HaLFY on LG9). Although these line-specific variants may be of great value for plant breeders or aid description of the molecular basis of particular phenotypes, they may offer little evolutionary value toward improving knowledge of the early domestication process. Since we examined genes homologous to well-characterized regulators of flowering, there are clear directions for follow-up studies.

Our initial concerns about ambiguity in QTL and gene relative positions may have been unfounded. No genes on LGs with flowering time QTLs but clearly mapping outside QTL regions (e.g., HaSOC1 and HAM75) exhibited signatures of selection, suggesting that our efforts could have been more efficient. In systems where more QTL studies have been conducted, more formal meta-analyses and computation of a composite map combining several densely genotyped panels may further improve the confidence of QTL/candidate gene colocalization and thus also improve the efficiency of this approach (Arcade et al. 2004; Chardon et al. 2004). Several observations suggest that genetic hitchhiking is a concern that impacts how effectively improvement loci can be identified, however. Signatures of selective sweeps during improvement were found for all three closely linked HaFT genes on LG6, but variation in at least one of these copies, HaFT3, is unlikely to have been under selection directly as this gene is nonfunctional (Blackman et al. 2010). Hitchhiking may also explain why multiple closely linked genes on LG7 exhibit evidence for selection during improvement (Chapman et al. 2008).

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) decayed relatively rapidly, r2 < 0.1 within ∼2 kb for a sample of elite and landrace lines (Liu and Burke 2006), but LD persisted for much greater distances in a sample of solely elite lines (r2 ∼ 0.32 at 5.5 kb and r2 < 0.1 at 150 kb; Kolkman et al. 2007; Fusari et al. 2008). LD may persist over even longer distances in regions containing targets of selection. For example, reductions in diversity around targets of selection in maize and rice have been shown to persist over large regions (∼250 kb to ∼1.1 Mb) containing multiple additional genes (Palaisa et al. 2004; Olsen et al. 2006; Tian et al. 2009).

Even if LD persists for such large distances in elite sunflower lines, genes would have to be linked by <1 cM in sunflower for hitchhiking to be relevant. The sunflower genome is ∼3.5 Gb large (Baack et al. 2005), and based on a map length of 1400 cM (Tang et al. 2002), there are ∼2.5 Mb/cM. HaFT2 and HaFT3 are indeed that closely linked, although HaFT2 is not present in the 10 and 100 kb of BAC sequence to either side of HaFT3. There is greater ambiguity on LG7 since HaTFL1 was not mapped on the same panel as the other selected genes, but several of those genes map within 1 cM of each other (Chapman et al. 2008). None of these genes are present in the ∼60 and ∼38 kb BAC of sequence flanking HaTFL1 though.

Molecular signature of changing selection pressure:

A surprising result from our work was that all the members of the FT/TFL1 gene family tested were under selection at some stage of crop evolution. While HaFT3 is likely a false positive and the contributions of HaTFL1 and HaFT4 to particular QTLs remain ambiguous, the timing of selection on these genes and their protein sequence or expression differences between wild and domesticated sunflower suggest an appealing evolutionary scenario. They provide a molecular signature of a reversal in the direction of selection on flowering time occurring over the history of sunflower cultivation.

The frameshift mutation in HaFT1 experienced selection during the initial stages of domestication due to either direct selection for later flowering or selection on indirect developmental effects on other traits. Alternatively, selection may have favored direct pleiotropic effects of the frameshift allele on other domestication traits, and later flowering was a by-product of this selection. QTLs for additional vegetative and reproductive traits map to this locus in multiple crosses (Burke et al. 2002; Wills and Burke 2007; Baack et al. 2008), and NILs segregating for the locus show genotype-dependent differences in some of these traits (Blackman et al. 2010). Genetic evidence supports roles for FT in plant architecture, meristem size, leaf development, and abscission zone formation in Arabidopsis and tomato (Jeong and Clark 2005; Jeong et al. 2008; Melzer et al. 2008; Shalit et al. 2009; Krieger et al. 2010).

Modern sunflower breeders imposed selection for early flowering. In-frame HaFT1 alleles may have been excluded by the genetic bottleneck at this stage of crop evolution, or selection may have continued to favor the frameshift mutation due to its effects on other traits. It is also possible that the fixation of additional mutations in HaFT1 or epistatic loci during early domestication also thwarted selection for a simple reversal of the frameshift in the domesticated background (Bridgham et al. 2009). Consequently, variation in other genes responded to selection. Genetic redundancy, their similar positions to HaFT1 in the flowering time regulatory network, and their molecular mode of action all may have primed HaFT2, HaFT4, and HaTFL1 to respond most appropriately. Both FT and TFL1 homologs interact with FD in other organisms (Pnueli et al. 2001; Abe et al. 2005; Wigge et al. 2005), and it has been hypothesized that phenotypic effects of these genes on flowering and growth depend on the outcome of competitive interactions between members of this family (Ahn et al. 2006; Shalit et al. 2009; Krieger et al. 2010). Increased expression of HaFT2 and HaFT4 are consistent with this scenario, particularly since there is evidence that HaFT2's elevated expression level is controlled by differences in cis-regulatory elements (Blackman et al. 2010). Expression of HaTFL1, a repressor of flowering, rose to higher levels earlier in development in CMSHA89 relative to Ann1238, an observation inconsistent with this scenario unless HaTFL1 expression is evolving to alleviate particular deleterious effects of increased HaFT expression.

Further work is required to support this scenario. Isolation of recombinants between HaFT1 and HaFT2 will be necessary to tease apart the contributions to flowering of the wild and domesticated alleles in these two genes. In addition, allele-specific expression analysis in additional elite × wild crosses will help determine how widespread putative cis-regulatory differences affecting HaFT2, HaFT4, and HaTFL1 are.

Functional variants in FT orthologs contribute to natural variation in flowering time in cereal varieties and natural populations of A. thaliana. In cultivated rice, the promoter type of Hd3a, an FT ortholog, is a significant predictor of expression level and flowering time (Kojima et al. 2002; Takahashi et al. 2009). Alleles of FT ortholog VRN3 in wheat and barley have noncoding variants that bypass a vernalization requirement for expression (Yan et al. 2006). Finally, allelic variation in FT and TWIN SISTER OF FT has been associated with natural variation in flowering among A. thaliana accessions (Schwartz et al. 2009; Atwell et al. 2010; Brachi et al. 2010). Notably, all of these previous findings involve cis-regulatory changes while our data suggest that changes in both expression and coding sequence of FT orthlologs were involved in the evolution of cultivated sunflower. Thus, our findings challenge the prediction that downstream genes like FT are more likely to exhibit regulatory variation (Schwartz et al. 2009). The redundancy afforded by a recent history of duplication, the novel derived expression domain of HaFT1, or multifarious selection acting on multiple pleiotropic effects may have uniquely fostered a selective sweep on a structural change in this case (Blackman et al. 2010); however, given the expansion of FT/TFL1 homolog numbers observed in other species (Carmel-Goren et al. 2003; Faure et al. 2007; Nishikawa et al. 2007; Danilevskaya et al. 2008; Igasaki et al. 2008; Mimida et al. 2009), similar results may soon be observed in additional systems.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank A. Kozik and the Compositae Genome Project for providing BLAST summaries of EST library assemblies; D. Wills and A. Heesacker for providing genetic map data for various mapping panels prior to publication; Z. Lai, H. Luton, A. Posto, and K. Turner for technical assistance; the Indiana University Greenhouse staff; L. Washington and the Indiana Molecular Biology Institute for sequencing; and M. Hahn, L. Moyle, and past and present members of the Rieseberg, Michaels, and Moyle lab groups for helpful discussions. The research was supported by National Science Foundation (NSF) (DBI0421630) and National Institutes of Health (NIH) (GM059065) grants to L.H.R.; NSF (IOB0447583) and NIH (GM075060) grants to S.D.M.; a NIH Ruth L. Kirschstein Postdoctoral Fellowship (5F32GM072409-02) to J.L.S.; and an NSF Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grant (DEB0608118) to B.K.B.

Supporting information is available online at http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/genetics.110.121327/DC1.

Sequence data from this article have been deposited with the EMBL/GenBank Data Libraries under accession nos. GU985570–GU987022 and HQ110110–HQ110505.

References

- Aagaard, J., J. Willis and P. Phillips, 2006. Relaxed selection among duplicate floral regulatory genes in Lamiales. J. Mol. Evol. 63 493–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe, M., Y. Kobayashi, S. Yamamoto, Y. Daimon, A. Yamaguchi et al., 2005. FD, a bZIP protein mediating signals from the floral pathway integrator FT at the shoot apex. Science 309 1052–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achard, P., 2004. Modulation of floral development by a gibberellin-regulated microRNA. Development 131 3357–3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achard, P., H. Cheng, L. De Grauwe, J. Decat, H. Schoutteten et al., 2006. Integration of plant responses to environmentally activated phytohormonal signals. Science 311 91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achard, P., M. Baghour, A. Chapple, P. Hedden, D. Van Der Straeten et al., 2007. The plant stress hormone ethylene controls floral transition via DELLA-dependent regulation of floral meristem-identity genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104 6484–6489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adrian, J., S. Farrona, J. J. Reimer, M. C. Albani, G. Coupland et al., 2010. cis-Regulatory elements and chromatin state coordinately control temporal and spatial expression of FLOWERING LOCUS T in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 22 1425–1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, J., D. Miller, V. J. Winter, M. J. Banfield, J. H. Lee et al., 2006. A divergent external loop confers antagonistic activity on floral regulators FT and TFL1. EMBO J. 25 605–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcade, A., A. Labourdette, M. Falque, B. Mangin, F. Chardon et al., 2004. BioMercator: integrating genetic maps and QTL towards discovery of candidate genes. Bioinformatics 20 2324–2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwell, S., Y. S. Huang, B. J. Vilhjalmsson, G. Willems, M. Horton et al., 2010. Genome-wide association study of 107 phenotypes in Arabidopsis thaliana inbred lines. Nature 465 627–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baack, E. J., K. D. Whitney and L. H. Rieseberg, 2005. Hybridization and genome size evolution: timing and magnitude of nuclear DNA content increases in Helianthus homoploid hybrid species. New Phytol. 167 623–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baack, E. J., Y. Sapir, M. A. Chapman, J. M. Burke and L. H. Rieseberg, 2008. Selection on domestication traits and quantitative trait loci in crop-wild sunflower hybrids. Mol. Ecol. 17 666–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker, M. S., N. C. Kane, M. Matvienko, A. Kozik, R. W. Michelmore et al., 2008. Multiple paleopolyploidizations during the evolution of the Compositae reveal parallel patterns of duplicate gene retention after millions of years. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25 2445–2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, A., and G. Theissen, 2003. The major clades of MADS-box genes and their role in the development and evolution of flowering plants. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 29 464–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bert, P. F., I. Jouan, D. T. de Labrouhe, F. Serre, J. Philippon et al., 2003. Comparative genetic analysis of quantitative traits in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). 2. Characterisation of QTL involved in developmental and agronomic traits. Theor. Appl. Genet. 107 181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackman, B. K., J. L. Strasburg, A. R. Raduski, S. D. Michaels and L. H. Rieseberg, 2010. The role of recently derived FT paralogs in sunflower domestication. Curr. Biol. 20 629–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachi, B., N. Faure, M. Horton, E. Flahauw, A. Vazquez et al., 2010. Linkage and association mapping of Arabidopsis thaliana flowering time in nature. PLoS Genet. 6 e1000940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, D., O. Ratcliffe, C. Vincent, R. Carpenter and E. Coen, 1997. Inflorescence commitment and architecture in Arabidopsis. Science 275 80–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridgham, J. T., E. A. Ortlund and J. W. Thornton, 2009. An epistatic ratchet constrains the direction of glucocorticoid receptor evolution. Nature 461 515–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger, J. C., M. A. Chapman and J. M. Burke, 2008. Molecular insights into the evolution of crop plants. Am. J. Bot. 95 113–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, J. M., S. Tang, S. J. Knapp and L. H. Rieseberg, 2002. Genetic analysis of sunflower domestication. Genetics 161 1257–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, J. M., S. J. Knapp and L. H. Rieseberg, 2005. Genetic consequences of selection during the evolution of cultivated sunflower. Genetics 171 1933–1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmel-Goren, L., Y. S. Liu, E. Lifschitz and D. Zamir, 2003. The SELF-PRUNING gene family in tomato. Plant. Mol. Biol. 52 1215–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casa, A. M., S. E. Mitchell, M. T. Hamblin, H. Sun, J. E. Bowers et al., 2005. Diversity and selection in sorghum: simultaneous analyses using simple sequence repeats. Theor. Appl. Genet. 111 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, M. A., C. H. Pashley, J. Wenzler, J. Hvala, S. Tang et al., 2008. A genomic scan for selection reveals candidates for genes involved in the evolution of cultivated sunflower (Helianthus annuus). Plant Cell 20 2931–2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chardon, F., B. Virlon, L. Moreau, M. Falque, J. Joets et al., 2004. Genetic architecture of flowering time in maize as inferred from quantitative trait loci meta-analysis and synteny conservation with the rice genome. Genetics 168 2169–2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, G. C., D. Barua, E. M. Kramer, R. M. Amasino and K. Donohue, 2009. Major flowering time gene, FLOWERING LOCUS C, regulates seed germination in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106 11661–11666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colasanti, J., Z. Yuan and V. Sundaresan, 1998. The indeterminate gene encodes a zinc finger protein and regulates a leaf-generated signal required for the transition to flowering in maize. Cell 93 593–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colasanti, J., R. Tremblay, A. Y. Wong, V. Coneva, A. Kozaki et al., 2006. The maize INDETERMINATE1 flowering time regulator defines a highly conserved zinc finger protein family in higher plants. BMC Genomics 7 158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colledge, S., and J. E. Conolly, 2007. The Origins and Spread of Domestic Plants in Southwest Asia and Europe. Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek, CA.

- Cong, B., L. S. Barrero and S. D. Tanksley, 2008. Regulatory change in YABBY-like transcription factor led to evolution of extreme fruit size during tomato domestication. Nat. Genet. 40 800–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbesier, L., C. Vincent, S. Jang, F. Fornara, Q. Fan et al., 2007. FT protein movement contributes to long-distance signaling in floral induction of Arabidopsis. Science 316 1030–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilevskaya, O. N., X. Meng, Z. Hou, E. V. Ananiev and C. R. Simmons, 2008. A genomic and expression compendium of the expanded PEBP gene family from maize. Plant Physiol. 146 250–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bodt, S., J. Raes, K. Florquin, S. Rombauts, P. Rouzé et al., 2003. Genomewide structural annotation and evolutionary analysis of the type I MADS-box genes in plants. J Mol. Evol. 56 573–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill, A., S. G. Thomas, J. Hu, C. M. Steber and T. P. Sun, 2004. The Arabidopsis F-box protein SLEEPY1 targets gibberellin signaling repressors for gibberellin-induced degradation. Plant Cell 16 1392–1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doebley, J., A. Stec and L. Hubbard, 1997. The evolution of apical dominance in maize. Nature 386 485–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doebley, J., B. S. Gaut and B. D. Smith, 2006. The molecular genetics of crop domestication. Cell 127 1309–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrona, S., G. Coupland and F. Turck, 2008. The impact of chromatin regulation on the floral transition. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 19 560–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure, S., J. Higgins, A. Turner and D. A. Laurie, 2007. The FLOWERING LOCUS T-like gene family in barley (Hordeum vulgare). Genetics 176 599–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornara, F., K. C. Panigrahi, L. Gissot, N. Sauerbrunn, M. Rühl et al., 2009. Arabidopsis DOF transcription factors act redundantly to reduce CONSTANS expression and are essential for a photoperiodic flowering response. Dev. Cell 17 75–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foucher, F., J. Morin, J. Courtiade, S. Cadioux, N. Ellis et al., 2003. DETERMINATE and LATE FLOWERING are two TERMINAL FLOWER1/CENTRORADIALIS homologs that control two distinct phases of flowering initiation and development in pea. Plant Cell 15 2742–2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frary, A., T. C. Nesbitt, S. Grandillo, E. Knaap, B. Cong et al., 2000. fw2.2: a quantitative trait locus key to the evolution of tomato fruit size. Science 289 85–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, D. Q., 2007. Contrasting patterns in crop domestication and domestication rates: recent archaeobotanical insights from the Old World. Ann. Bot. 100 903–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusari, C., V. Lia, H. E. Hopp, R. Heinz and N. Paniego, 2008. Identification of single nucleotide polymorphisms and analysis of linkage disequilibrium in sunflower elite inbred lines using the candidate gene approach. BMC Plant Biol. 8 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi, S. D., A. F. Heesacker, C. A. Freeman, J. Argyris, K. Bradford et al., 2005. The self-incompatibility locus (S) and quantitative trait loci for self-pollination and seed dormancy in sunflower. Theor. Appl. Genet. 111 619–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyne, P. J., and A. A. Schneiter, 1988. Temperature and photoperiod interactions with the phenological development of sunflower. Agron. J. 80 777–784. [Google Scholar]

- Goyne, P. J., A. A. Schneiter, K. C. Cleary, R. A. Creelman, W. D. Stegmeier et al., 1989. Sunflower genotype response to photoperiod and temperature in field environments. Agron. J. 81 826–831. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X., Z. Zhao, J. Chen, X. Hu and D. Luo, 2006. A putative CENTRORADIALIS/TERMINAL FLOWER 1-like gene, Ljcen1, plays a role in phase transition in Lotus japonicus. J. Plant Physiol. 163 436–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamblin, M. T., A. M. Casa, H. Sun, S. C. Murray, A. H. Paterson et al., 2006. Challenges of detecting directional selection after a bottleneck: lessons from Sorghum bicolor. Genetics 173 953–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter, A. V., K. A. Gardner, D. Falush, D. L. Lentz, R. A. Bye et al., 2004. Origin of extant domesticated sunflowers in eastern North America. Nature 430 201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht, V., F. Foucher, C. Ferrándiz, R. Macknight, C. Navarro et al., 2005. Conservation of Arabidopsis flowering genes in model legumes. Plant Physiol. 137 1420–1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heesacker, A., V. K. Kishore, W. Gao, S. Tang, J. M. Kolkman et al., 2008. SSRs and INDELs mined from the sunflower EST database: abundance, polymorphisms, and cross-taxa utility. Theor. Appl. Genet. 117 1021–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heesacker, A. F., E. Bachlava, R. L. Brunick, J. M. Burke, L. H. Rieseberg et al., 2009. Karyotypic evolution of the common and silverleaf sunflower genomes. Plant Genome 2 233–246. [Google Scholar]

- Heiser, C. B., Jr., 1951. The sunflower among the North American Indians. Proc. Am. Philos. Soc. 95 432–448. [Google Scholar]

- Heiser, C. B., Jr., 1954. Variation and subspeciation in the common sunflower, Helianthus annuus. Am. Midl. Nat. 51 287–305. [Google Scholar]

- Hileman, L. C., J. F. Sundstrom, A. Litt, M. Chen, T. Shumba et al., 2006. Molecular and phylogenetic analyses of the MADS-box gene family in tomato. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23 2245–2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, R. R., M. Kreitman and M. Aguade, 1987. A test of neutral molecular evolution based on nucleotide data. Genetics 116 153–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hufford, K. M., P. Canaran, D. H. Ware, M. D. McMullen and B. S. Gaut, 2007. Patterns of selection and tissue-specific expression among maize domestication and crop improvement loci. Plant Physiol. 144 1642–1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igasaki, T., Y. Watanabe, M. Nishiguchi and N. Kotoda, 2008. The FLOWERING LOCUS T/TERMINAL FLOWER 1 family in Lombardy poplar. Plant Cell Physiol. 49 291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaizumi, T., H. G. Tran, T. E. Swartz, W. R. Briggs and S. A. Kay, 2003. FKF1 is essential for photoperiodic-specific light signalling in Arabidopsis. Nature 426 302–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaizumi, T., T. F. Schultz, F. G. Harmon, L. A. Ho and S. Kay, 2005. FKF1 F-box protein mediates cyclic degradation of a repressor of CONSTANS in Arabidopsis. Science 309 293–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izawa, T., 2007. Adaptation of flowering time by natural and artificial selection in Arabidopsis and rice. J. Exp. Bot. 58 3091–3097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, K. E., and P. A. Wigge, 2007. FT protein acts as a long-range signal in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 17 1050–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang, S., V. Marchal, K. C. Panigrahi, S. Wenkel, W. Soppe et al., 2008. Arabidopsis COP1 shapes the temporal pattern of CO accumulation conferring a photoperiodic flowering response. EMBO J. 27 1277–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, S., and S. E. Clark, 2005. Photoperiod regulates flower meristem development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 169 907–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, S., M. Rebeiz, P. Andolfatto, T. Werner, J. True et al., 2008. The evolution of gene regulation underlies a morphological difference between two Drosophila sister species. Cell 132 783–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J., W. Huang, J. P. Gao, J. Yang, M. Shi et al., 2008. Genetic control of rice plant architecture under domestication. Nat. Genet. 40 1365–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung, J. H., Y. H. Seo, P. J. Seo, J. L. Reyes, J. Yun et al., 2007. The GIGANTEA-regulated microRNA172 mediates photoperiodic flowering independent of CONSTANS in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19 2736–2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, Y., and D. Weigel, 2007. Move on up, it's time for change: mobile signals controlling photoperiod-dependent flowering. Gene Dev. 21 2371–2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, S., Y. Takahashi, Y. Kobayashi, L. Monna, T. Sasaki et al., 2002. Hd3a, a rice ortholog of the Arabidopsis FT gene, promotes transition to flowering downstream of Hd1 under short-day conditions. Plant Cell Physiol. 43 1096–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolkman, J. M., S. T. Berry, A. J. Leon, M. Slabaugh, S. Tang et al., 2007. Single nucleotide polymorphisms and linkage disequilibrium in sunflower. Genetics 177 457–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, U., Z. B. Lippman and D. Zamir, 2010. The flowering gene SINGLE FLOWER TRUSS drives heterosis for yield in tomato. Nat. Genet. 42 459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Z., K. Livingstone, Y. Zou, S. A. Church, S. J. Knapp et al., 2005. Identification and mapping of SNPs from ESTs in sunflower. Theor. Appl. Genet. 111 1532–1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander, E. S., P. Green, J. Abrahamson, A. Barlow, M. J. Daly et al., 1987. MAPMAKER: an interactive computer package for constructing primary genetic linkage maps of experimental and natural populations. Genomics 1 174–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laubinger, S., V. Marchal, J. Le Gourrierec, J. Gentilhomme, S. Wenkel et al., 2006. Arabidopsis SPA proteins regulate photoperiodic flowering and interact with the floral inducer CONSTANS to regulate its stability. Development 133 3213–3222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J., M. Oh, H. Park and I. Lee, 2008. SOC1 translocated to the nucleus by interaction with AGL24 directly regulates leafy. Plant J. 55 832–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon, A. J., F. H. Andrade and M. Lee, 2000. Genetic mapping of factors affecting quantitative variation for flowering in sunflower. Crop Sci. 40 404–407. [Google Scholar]

- Leon, A. J., M. Lee and F. H. Andrade, 2001. Quantitative trait loci for growing degree days to flowering and photoperiod response in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 102 497–503. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, Y. Y., S. Mesnage, J. S. Mylne, A. R. Gendall and C. Dean, 2002. Multiple roles of Arabidopsis VRN1 in vernalization and flowering time control. Science 297 243–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, C., A. Zhou and T. Sang, 2006. Rice domestication by reducing shattering. Science 311 1936–1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]