Abstract

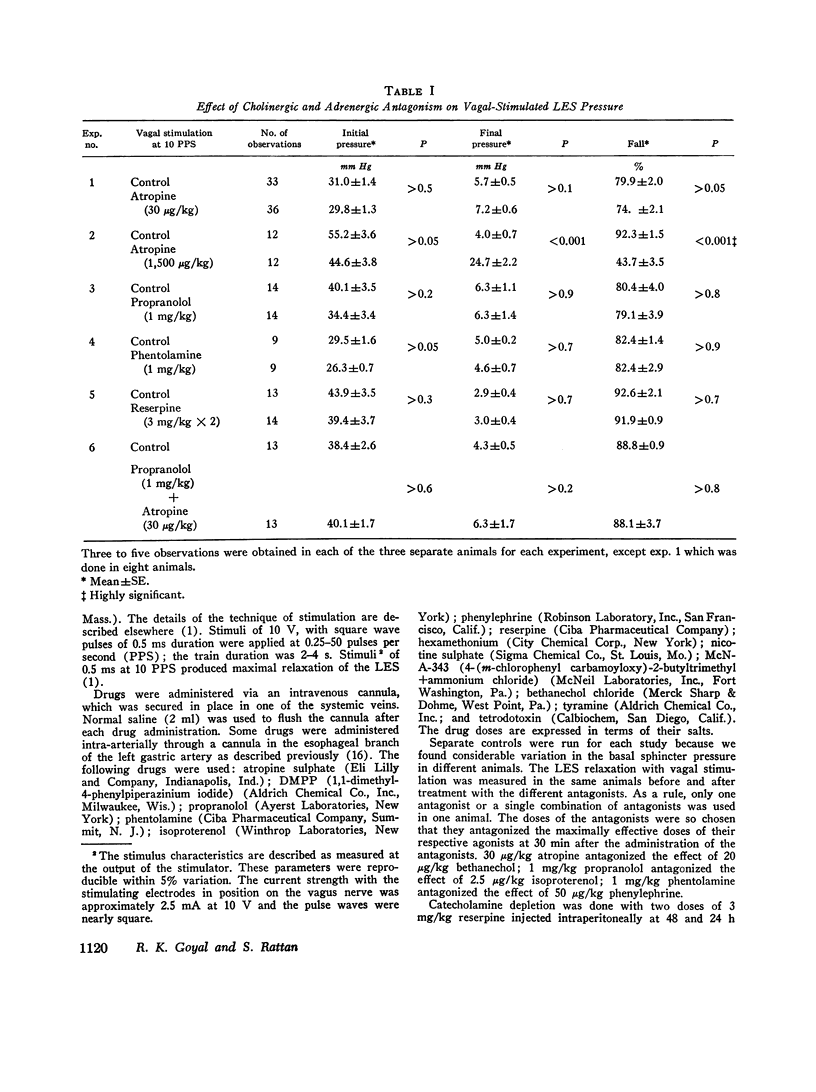

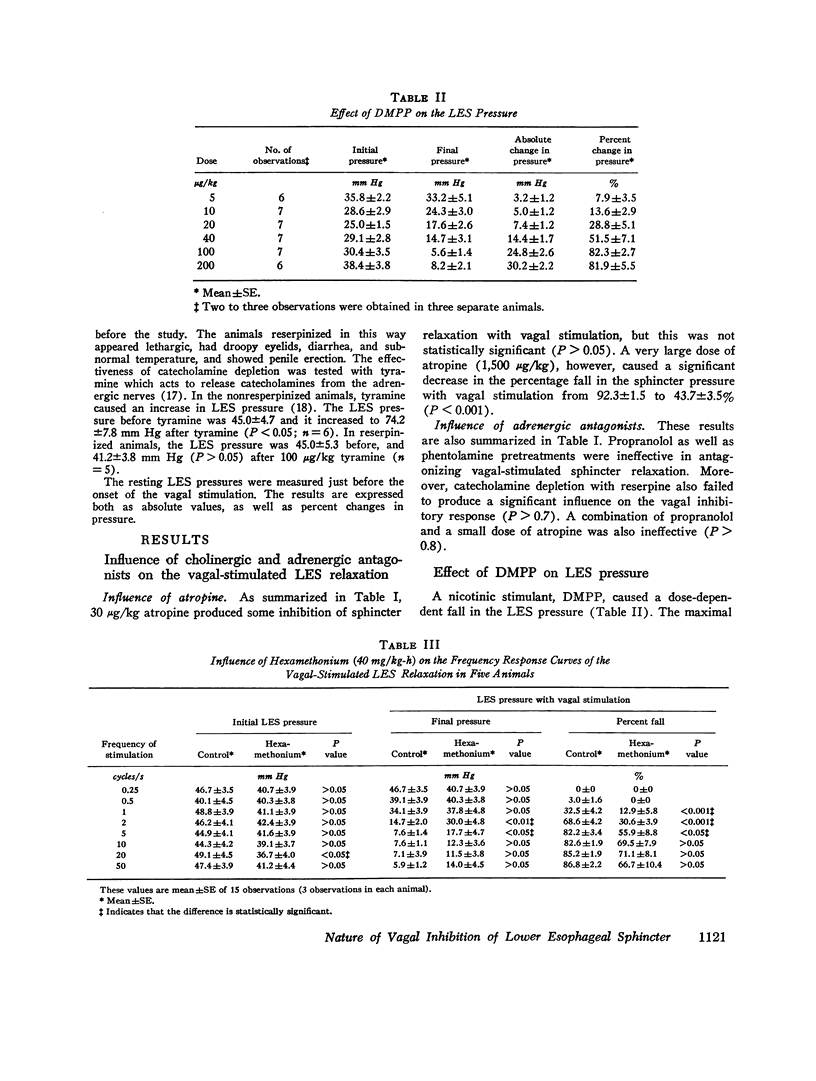

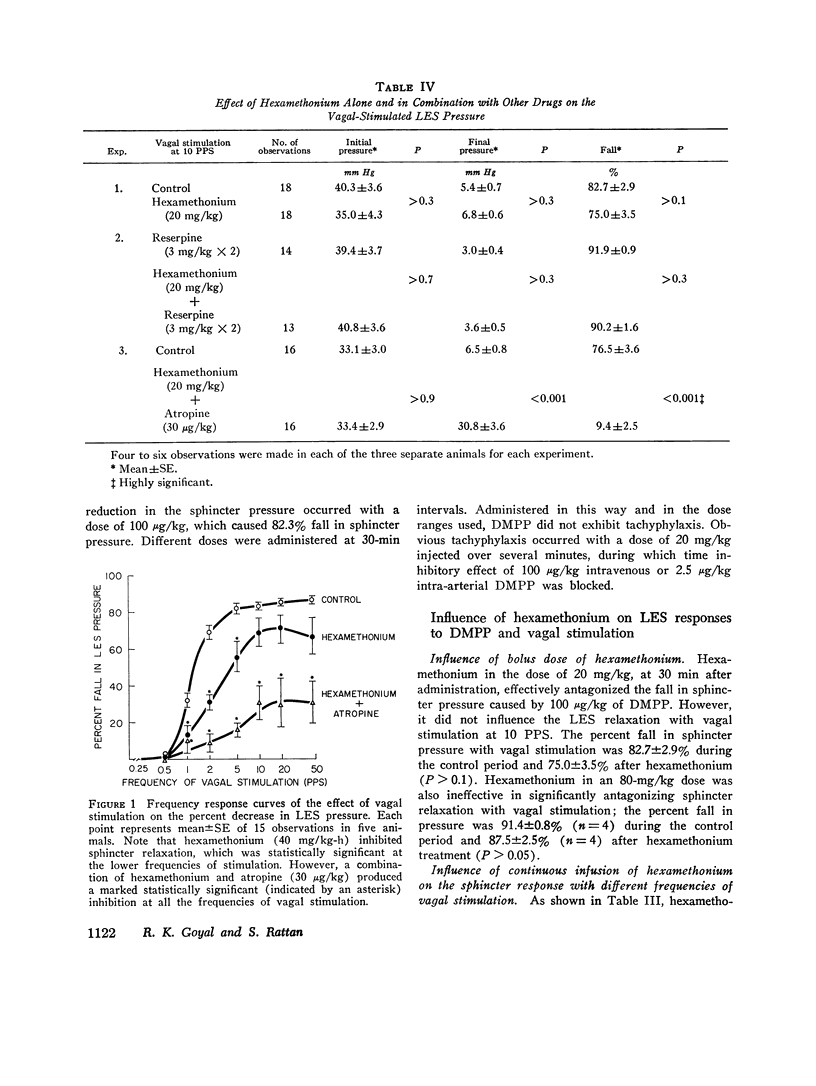

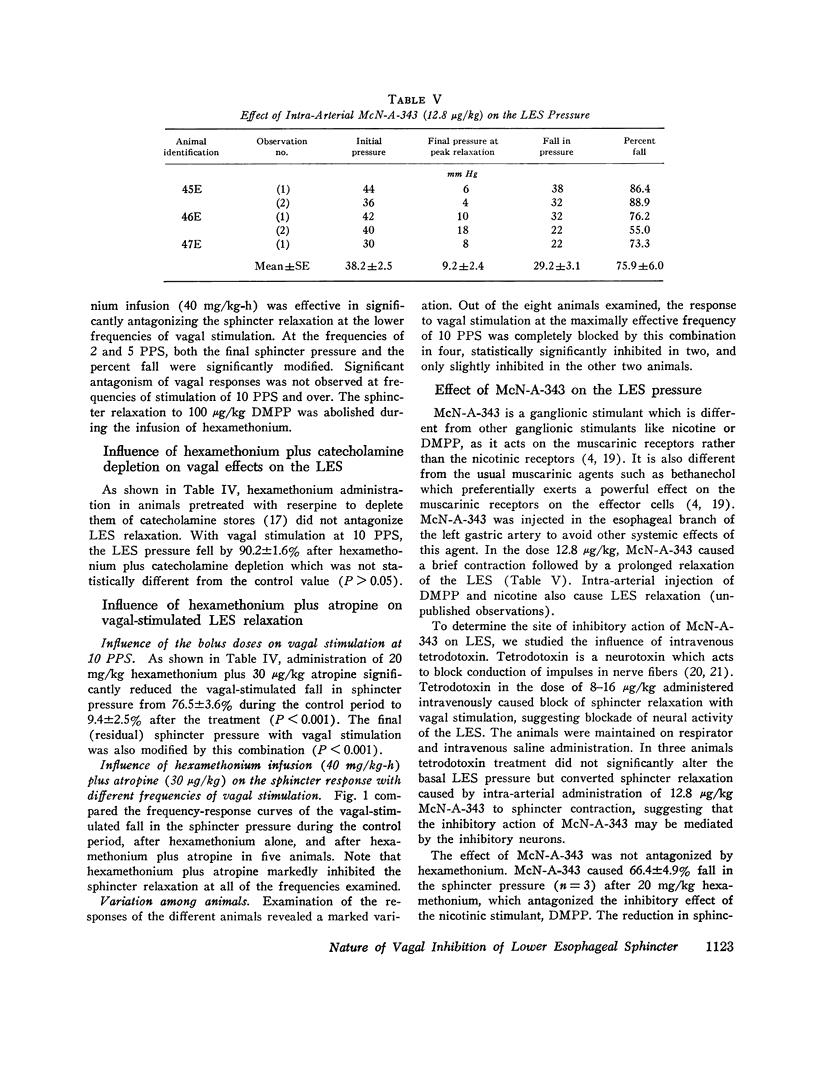

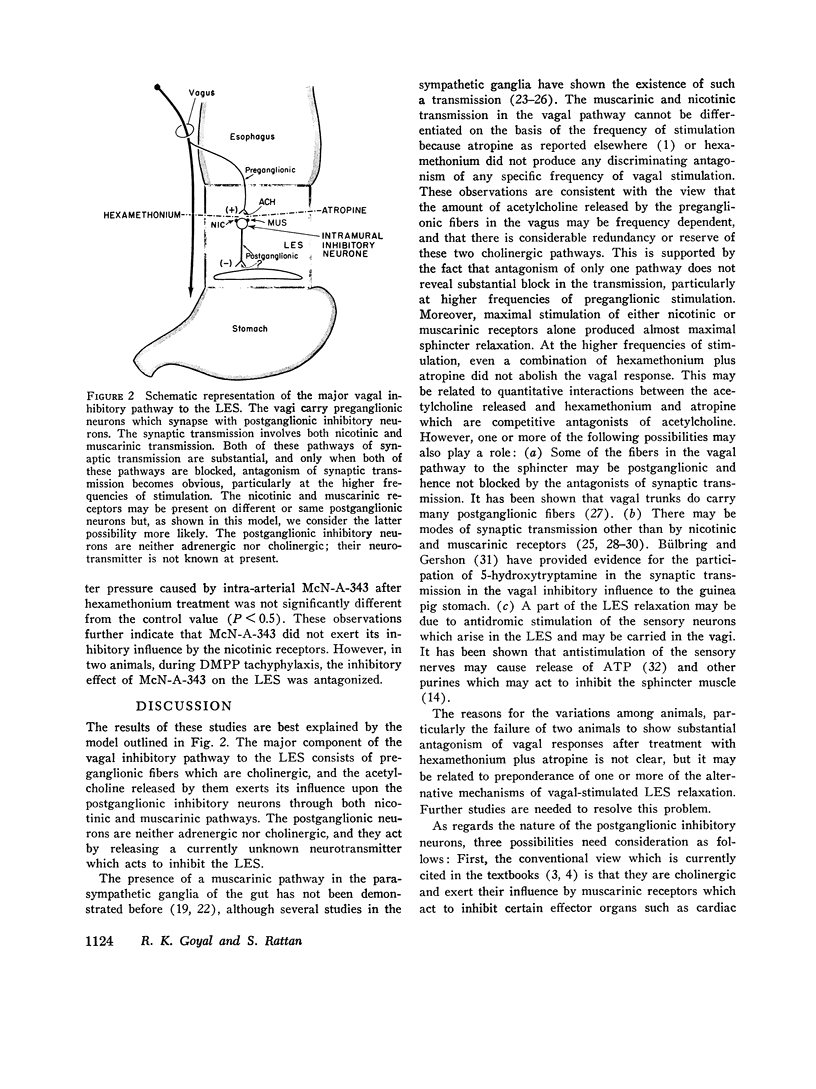

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the nature of the vagal inhibitory innervation to the lower esophageal sphincter in the anesthetized opossum. Sphincter relaxation with electrical stimulation of the vagus was not antagonized by atropine, propranolol, phentolamine, or by catechloamine depletion with reserpine. A combination of atropine and propranolol was also ineffective, suggesting that the vagal inhibitory influences may be mediated by the noncholinergic, nonadrenergic neurons. To determine whether a synaptic link with nicotinic transmission was present, we investigated the effect of hexamethonium on vagal-stimulated lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. Hexamethonium in doses that completely antagonized the sphincter relaxation in response to a ganglionic stimulant, 1,1-dimethyl-4-phenylpiperazinium iodide (DMPP), did not block the sphincter relaxation in response to vagal stimulation at 10 pulses per second, and optimal frequency of stimulation. A combination of hexamethonium and catecholamine depletion was also ineffective, but hexamethonium plus atropine markedly antagonized sphincter relaxation (P less than 0.001). Moreover, 4-(m-chlorophenyl carbamoyloxy)-2-butyltrimethylammonium chloride (McN-A-343), a muscarinic ganglionic stimulant, also caused relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter. We suggest from these results that: (a) pthe vagal inhibitory pathway to the sphincter consists of preganglionic fibers which synapse with postganglionic neurons: (b) the synaptic transmission is predominantly cholinergic and utilizes nicotinic as well as muscarinic receptors on the postganglionic neuron, and; (c) postganglionic neurons exert their influence on the sphincter by an unidentified inhibitory transmitter that is neither adrenergic nor cholinergic.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alkadhi K. A., McIsaac R. J. Non-nicotinic transmission during ganglionic block with chlorisondamine and nicotine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1973 Oct;24(1):78–85. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(73)90116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beani L., Bianchi C., Crema A. Vagal non-adrenergic inhibition of guinea-pig stomach. J Physiol. 1971 Sep;217(2):259–279. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A. M. Cardiac sympathetic adrenergic pathways in which synaptic transmission is blocked by atropine sulfate. J Physiol. 1967 Jul;191(2):271–288. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Purinergic nerves. Pharmacol Rev. 1972 Sep;24(3):509–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bülbring E., Gershon M. D. 5-hydroxytryptamine participation in the vagal inhibitory innervation of the stomach. J Physiol. 1967 Oct;192(3):823–846. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLARK C. G., VANE J. R. The cardiac sphincter in the cat. Gut. 1961 Sep;2:252–262. doi: 10.1136/gut.2.3.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen J., Conklin J. L., Freeman B. W. Physiologic specialization at esophagogastric junction in three species. Am J Physiol. 1973 Dec;225(6):1265–1270. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1973.225.6.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen J., Daniel E. E. Effects of some autonomic drugs on circular esophageal smooth muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1968 Feb;159(2):243–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen J., Lund G. F. Esophageal responses to distension and electrical stimulation. J Clin Invest. 1969 Feb;48(2):408–419. doi: 10.1172/JCI105998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel E. E. Electrical and contractile responses of the pyloric region to adrenergic and cholinergic drugs. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1966 Nov;44(6):951–979. doi: 10.1139/y66-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMarino A. J., Cohen S. The adrenergic control of lower esophageal sphincter function. An experimental model of denervation supersensitivity. J Clin Invest. 1973 Sep;52(9):2264–2271. doi: 10.1172/JCI107413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELLIS F. G., KAUNTZE R., TROUNCE J. R. The innervation of the cardia and lower oesophagus in man. Br J Surg. 1960 Mar;47:466–472. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18004720503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon M. D. Effects of tetrodotoxin on innervated smooth muscle preparations. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1967 Mar;29(3):259–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1967.tb01958.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal R. K., Rattan S. Mechanism of the lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. Action of prostaglandin E 1 and theophylline. J Clin Invest. 1973 Feb;52(2):337–341. doi: 10.1172/JCI107189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greengard P., McAfee D. A., Kebabian J. W. On the mechanism of action of cyclic AMP and its role in synaptic transmission. Adv Cyclic Nucleotide Res. 1972;1:337–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLTON P. The liberation of adenosine triphosphate on antidromic stimulation of sensory nerves. J Physiol. 1959 Mar 12;145(3):494–504. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1959.sp006157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INGELFINGER F. J. Esophageal motility. Physiol Rev. 1958 Oct;38(4):533–584. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1958.38.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao C. Y. Tetrodotoxin, saxitoxin and their significance in the study of excitation phenomena. Pharmacol Rev. 1966 Jun;18(2):997–1049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misiewicz J. J., Waller S. L., Anthony P. P., Gummer J. W. Achalasia of the cardia: pharmacology and histopathology of isolated cardiac sphincteric muscle from patients with and without achalasia. Q J Med. 1969 Jan;38(149):17–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninckx F., Kerremans R., Beckers J. Pharmacological characteristics of the non-striated anorectal musculature in cats. Gut. 1973 May;14(5):393–398. doi: 10.1136/gut.14.5.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattan S., Goyal R. K. Neural control of the lower esophageal sphincter: influence of the vagus nerves. J Clin Invest. 1974 Oct;54(4):899–906. doi: 10.1172/JCI107829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHENK E. A., FREDERICKSON E. L. Pharmacologic evidence for a cardiac sphincter mechanism in the cat. Gastroenterology. 1961 Jan;40:75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trendelenburg U. Transmission of preganglionic impulses through the muscarinic receptors of the superior cervical ganglion of the cat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1966 Dec;154(3):426–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuch A., Cohen S. Lower esophageal sphincter relaxation: studies on the neurogenic inhibitory mechanism. J Clin Invest. 1973 Jan;52(1):14–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI107157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volle R. L. Ganglionic transmission. Annu Rev Pharmacol. 1969;9:135–146. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.09.040169.001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisbrodt N. W., Christensen J. Gradients of contractions in the opossum esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1972 Jun;62(6):1159–1166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]