Abstract

Epigenetics refers to heritable changes that control how the genome is accessed in different cell-types and during development and differentiation. Even though each cell contains essentially the same genetic code, epigenetic mechanisms permit specialization of function between cells. The state of chromatin, the complex of histone proteins, RNA and DNA that efficiently package the genome, is largely regulated by specific modifications to histone proteins and DNA, and the recognition of these marks by other proteins and protein complexes. The enzymes that produce these modifications (the ‘writers’), the proteins that recognize them (the ‘readers’), and the enzymes that remove them (the ‘erasers’) are critical targets for manipulation in order to further understand the histone code and its role in biology and human disease.

1. Introduction: Epigenetics

Multicellular organisms have evolved elaborate mechanisms to enable cell-type specific expression of genes. Epigenetics refers to heritable changes that control how the genome is accessed in different cell-types and during development and differentiation 1. Even though each cell contains essentially the same genetic code, epigenetic mechanisms permit specialization of function between cells. Over the last decade, the cellular machinery that creates these heritable changes has been the subject of intense scientific investigation as there is no area of biology or indeed, human health where epigenetics may not play a fundamental role 2.

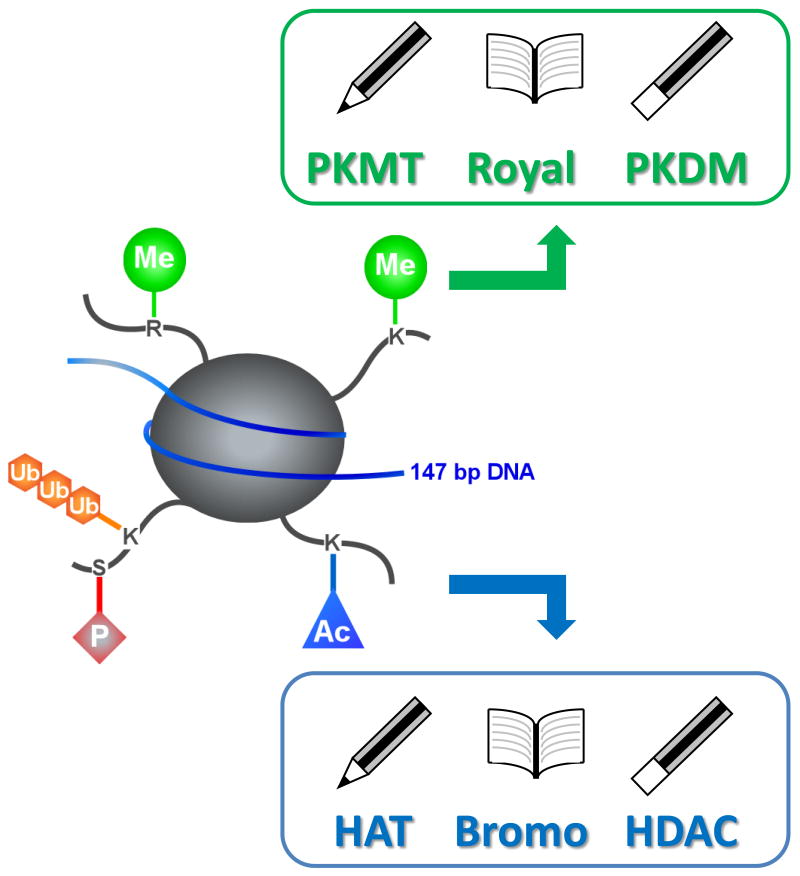

The template upon which the epigenome is written is chromatin – the complex of histone proteins, RNA and DNA that efficiently package the genome within each cell. The basic building block of chromatin structure is the nucleosome – an octomer of histone proteins (associated dimers of H3 and H4 capped with dimers of H2A and H2B) around which 147 base pairs of DNA are wound. The amino-terminal tails of histone proteins project from the nucleosome structure and are subject to more than 100 post-translational modifications (PTM) 2. The state of chromatin, and therefore access to the genetic code, is largely regulated by specific modifications to histone proteins and DNA, and the recognition of these marks by other proteins and protein complexes 3, 4. The enzymes that produce these modifications (the ‘writers’), the proteins that recognize them (the ‘readers’), and the enzymes that remove them (the ‘erasers’, Figure 1) are critical targets for manipulation in order to further understand the histone code and its role in biology and human disease 5, 6. Indeed, small molecule inhibitors of histone deacetylases have already proven useful in the treatment of cancer 7, 8 and the role of lysine acetylation is rivaling that of phosphorylation in importance as a PTM that regulates protein function 9, 10. While histone phosphorylation plays a significant role in epigenetics, the technologies underlying kinase activity measurement are well understood and the impact of ubiquitination and sumoylation are as yet nascent, so this review will focus on tools and techniques associated with methylation and acetylation.

Figure 1.

Nucleosomes are octomers of associated dimers of histone H3 and H4 proteins capped by dimers of H2A and H2B, and this protein core is surrounded by ∼147 bp of double-stranded DNA. The physical spacing between repeating nucleosomal subunits controls the level of DNA condensation and the access of transcription factors and replication machinery to the genetic information. Post-translational modifications to the flexible N-terminal tails that protrude from the nucleosomal core controls the level of DNA packaging, and influences the temporal and spatial expression of genes. The most commonly studied modifications are the acteylation of lysine, which is ‘written’ and ‘erased’ by histone acetyltransferases and histone deacetylases, and lysine methylation which is ‘written’ and ‘erased’ by protein methyltransferases and protein demethylases. The marks are ‘read’ by two major families of proteins: Bromodomains bind to and recognize acetylated lysine, while the Royal family of proteins recognize and bind to methylated lysine. Other important histone post-translational modifications include the methylation of arginine, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination.

2. Overview of Histone Methylation – Tools and Technologies

Since the discovery of the first histone lysine methyltransferase in 200011, the study of histone methylation in the context of drug discovery has experienced exponential growth because of its essential function in many biological processes12. Now, a decade later, there are > 50 protein lysine methyltransferases (PKMTs) and > 10 protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) known12-14 and, depending on the identity of the enzyme, varying degrees of methylation can be attained; lysine can be mono-, di or trimethylated, while arginine can be monomethylated, symmetrically dimethylated or asymmetrically dimethylated. Among the PKMTs, all but one enzyme, DOT1L, contain an evolutionarily conserved catalytic subunit of ∼130 amino acids called a SET domain15, 16 and the PRMTs are divided into type I and type II families that respectively catalyze the formation of asymmetric or symmetric ω-NG,NG-dimethylarginine tails 17. All PKMTs and PRMTs transfer a methyl group from the cofactor S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) to the target residue through a bimolecular SN2-like mechanism and produce S-adenosylhomocysteine as a by-product14. Due to their functional similarity to protein kinases, protein methyltransferases (PMTs) may represent a novel and highly tractable target-family for drug discovery.

Recognition of methyl-lysine marks has been associated with the “Royal Family” of proteins including those containing Tudor, Chromo, Maligant Brain Tumor (MBT), PWWP, and plant Agenet domains, the plant homeodomain (PHD) family and the WD40 repeat protein WRD5. These motifs all have structurally related binding pockets defined by an aromatic electron-rich cage and H-bond donors that interact with the lysine cation18. Methyl-lysine binding proteins can directly influence the structural state of chromatin19 or act as scaffolding for other proteins that are involved in chromatin remodeling20. In addition, many chromatin-acting enzymes, including a vast number that modify histones, contain methyl-lysine recognition domains or can often be found in complexes with proteins that do, recruiting the catalytic domains to the appropriate site of action21.

Until recently, histone methylation was thought to be a stable and irreversible PTM, but the isolation of the first known histone demethylase in 200422 and the subsequent identification of > 30 demethylating enzymes since has suggested that histone methylation is a highly dynamic and complex process. All protein demethylases (PKDMs) oxidize the carbon of the targeted methyl group, which degrades to release formaldehyde. Among the demethylases, there are flavin-dependent monoamine oxidases like LSD1 that utilize an FAD+ cofactor to catalyze oxidation of mono- and dimethyl-lysines, and the JmjC domain demethylases that utilize iron and α-ketoglutarate cofactors to hydroxylate mono-, di or trimethyl-lysines 23.

As epigenetic targets involved in writing, reading and erasing histone methylation continue to find a place in drug discovery pipelines, the assay technologies available to support high-throughput screening and compound profiling has become more advanced and sophisticated. For the enzymes that alter the methylation state of histone proteins, there are two major strategies for measuring activity: (1) detecting the formation or depletion of methylated substrate, and (2) monitoring the rate of cofactor usage by the enzymes.

While it is more practical to perform in vitro activity assays on peptide substrates, it can be advantageous to consider the use of whole nucleosomes as substrates in enzymatic reactions. For example, the enzyme DOT1L only shows catalytic activity in the context of whole nucleosomes and requires contact with ubiquitinated histone H2B to stimulate its catalytic activity toward the H3K79 residue, which is part of the core nucleosome rather than the amino-terminal tail24. In addition, allosteric regulators of PMTs and PDMs that do not bind near the lysine binding channel or the SAM-binding pocket may be overlooked when using peptide substrates. However, most histone-modifying enzymes, particularly those that act on the flexible amino tails, are often amenable to the use of peptide substrates.

In the substrate-based assay strategy, synergy can be obtained between the methyltransferases and demethylases, as assays configured to monitoring the methylation status of the substrate are applicable to both classes of enzymes. The use of antibodies against specific methyl-lysine histone marks and a secondary anti-IgG antibody with a reporter molecule are frequently employed in small molecule screening efforts. The secondary antibody can be conjugated to an enzyme such as horseradish peroxidase (ELISA)25, to lanthanide metals such as Europium (DELFIA)26 for a time resolved fluorescence signal (TRF) or to an AlphaScreen acceptor bead. In the latter, a second AlphaScreen donor bead is coupled to the peptide substrate and a binding event that brings the beads into close proximity (within 200 nm) will allow singlet oxygen molecules to be transferred from the donor to the acceptor bead, generating a chemiluminescent signal27. Success using the antibody-based detection method is heavily reliant on the use of high quality antibodies, and selecting an antibody for the proper mark. For example, G9a activity can produce both mono- and dimethyl-lysine, but functional assays have only been performed with an antibody against dimethyl-lysine26. Another technique takes advantage of the fact that endoproteinase-LysC, which cleaves peptide bonds C-terminal to lysine, is unable to do so if the lysine is methylated. When coupled to microfluidic capillary electrophoresis using the Caliper Life Sciences Labchip™ technology, this methylation-sensitive proteolysis permits the detection of the ratio of methylated to unmethylated peptides from a 384-well plate, and enzymatic activity can be quantitated accurately and precisely 28, allowing it to be used for both HTS and quantitative enzymology in the generation of Ki's. Alternatively, measuring the incorporation of a radioactive methyl group from 3H-SAM to substrates anchored to microplates is a proven, inexpensive and sensitive method that is compatible with both synthetic peptides and whole nucleosomes29, 30. However, radioactivity is inherently hazardous to the assay operator and the necessity for disposal of bulk reagents and decontamination of liquid handling equipment usually make it an assay of last resort.

The second strategy, measuring cofactor usage, is PKMT- or PKDM-specific. In the case of PKMTs, the conversion of SAM to SAH has been measured using an enzyme-coupled assay that uses SAH hydrolase (and adenosine deaminase) to produce inosine and homocysteine, the latter of which can be detected using the Thioglo reagent, which fluoresces strongly when its maleimide moiety reacts with a thiol31. Caution must be exercised when using the assay to avoid reducing agents such as DTT in the assay buffer, and to keep the PKMT and any thiol-containing substrates at concentrations that do not saturate the Thioglo emission. In addition, several other enzyme coupled assays for PKMTs have been reported32, 33. PKDMs produce formaldehyde and peroxide as by-products of catalysis, both of which can be detected using enzyme-coupling systems. Formaldehyde dehydrogenase reduces formaldehyde to formic acid, and this can be coupled stoichiometrically to the reduction of NAD+ to NADH, which has an absorbance maximum of 340 nm34. The formaldehyde dehyrogenase coupling assay is quite robust, and has recently been miniaturized to a 1536-well format to enable μHTS35. Another method compatible for screening PKDMs is the detection of the peroxide formed using one of several known peroxidase coupled assays36, 37.

Isolated methyl-lysine binding proteins (KMe readers) bind their cognate histone peptides with low affinity, however, the combinatorial effect of multiple interactions on various lysine marks leads to high binding affinity and specificity in vivo38. Biochemical techniques such as fluorescence polarization39, isothermal titration calorimetry39, 40, surface plasmon resonance41 and nuclear magnetic resonance42 have indicated that, in vitro, the Kd of KMe readers for a single methyl-lysine histone mark on a synthetic peptide is in the 25 – 200 μM range. As a result, it is challenging to subject individual reader proteins to biochemical screening assays amenable to HTS because the requirement for protein to run assays would be too great (i.e., > 50 μM protein per well). To circumvent this problem, AlphaScreen has been employed in screening for inhibitors of methyl-lysine recognition 43, 44. In these assays a biotinylated peptide containing the desired methyl-lysine modification is bound by the KMe reader containing a hexahistidine or glutathione S-transferase purification tag, and streptavidin-coated donor beads and nickel- or glutathione-coated acceptor beads are added. As described above, a chemiluminescent signal can be generated when the beads are brought into proximity due to a binding interaction between the peptide and protein. The requirement for protein in the AlphaScreen assay is in the low nanomolar range, as opposed to the micromolar range for other techniques. This can be attributed to the phenomenon of bead avidity, where each bead has multiple sites for the capture of ligands, and binding affinities are the sum of multiple interactions. The transduction of the AlphaScreen signal is sensitive to singlet oxygen quenchers, organometallic compounds and metal-chelating agents, and a counterscreen should be performed to purge these compounds from subsequent follow-up studies. AlphaScreen is a very promising tool for hit discovery but the caveat should be noted that these same advantages for use in primary screening complicate compound profiling and rank-order potency determination, and alternate biophysical methods may be more appropriate for lead optimization once the hits have been identified with the primary AlphaScreen assay.

3. Chemical Tools for Protein Lysine Methyltransferases

Growing evidence suggests that PKMTs play critical roles in the development of various human diseases including cancer,15, 45-47 inflammation,48 drug addiction,49 and mental retardation.50 For example, G9a, also known as EHMT2, is over expressed in human cancers and knockdown of G9a inhibits cancer cell growth.51, 52 In addition, G9a catalyzes dimethylation of lysine 373 (K373) of p53, a tumor suppressor.53 The dimethylation of p53 K373 results in the inactivation of p53.53

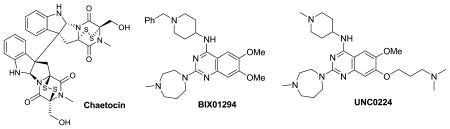

To date, 3 selective small molecule PKMT inhibitors have been reported.26, 54-56 Chaetocin, a fungal mycotoxin, was identified as the first selective small molecule inhibitor of H3K9 PKMT SU(VAR)3-9 (IC50 = 0.6 μM) via screening of 2,967 compounds55. Chaetocin also inhibited SUV39H1 (IC50 = 0.8 μM), the human ortholog of SU(VAR)3-9, and was selective for H3K9 PKMTs over other PKMTs that do not target H3K9, for example, EZH2, SET7/9, and SET8/Pre-SET7.55 Mechanistically, chaetocin is a SAM competitive inhibitor that was reported to be cellularly active and not toxic to cells at up to 0.5 μM.55 Cells treated with 0.5 μM chaetoxin show a marked reduction of dimethylation and trimethylation of H3K9 without affecting the methylation state of H3K27, H3K36, and H3K79.55

BIX-01294 is a small molecule inhibitor of G9a and GLP (a H3K9 PKMT that shares 80% sequence identity with G9a in their respective SET domains) that was discovered via screening of a library of 125,000 synthetic compounds.26 BIX-01294 is selective for G9a and GLP over several H3K9 PKMTs including SUV39H1 and ESET, other KMTs such as SET7/9, and the arginine methyltransferase PRTM1.26 The X-ray crystal structure of GLP and BIX-01294 confirmed that BIX-01294 bound to the histone peptide binding pocket but failed to interact with the lysine binding channel.57 Cells dosed with BIX-01294 at 4.1 μM were characterized by reduced H3K9me2 levels in several cell lines but toxicity to cells at > 4.1 μM was observed.26 More importantly, BIX-01294 at 4.1 μM reduced the H3K9me2 levels at several G9a target genes including mage-a2, Bmi1, and Serac1 and the inhibitor effects were reversible and restored upon removal of the inhibitor.26

Design and synthesis based on the GLP and BIX-01294 X-ray co-crystal structure in combination with initial structure activity relationship (SAR) exploration led to the discovery of UNC0224 as a potent and selective G9a inhibitor.56 UNC0224 (IC50 = 15 nM) possessing a 7-dimethylaminopropoxy chain was > 5-fold more potent compared to BIX-01294 (IC50 = 106 nM) in the G9a ThioGlo assay. The high potency of UNC0224 was confirmed in isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) (Kd = 23 nM for UNC0224 vs. Kd of 130 nM for BIX-01294).56 UNC0224 showed similar potency versus GLP, but was more than 1,000-fold selective for G9a over SET7/9 and SET8/PreSET7.56 In addition, UNC0224 showed good selectivity against a broad range of G-protein coupled receptors, ion channels, and transporters.56 A high resolution X-ray co-crystal structure of G9a and UNC0224, the first co-crystal structure of a G9a and a small molecule inhibitor, confirmed that the 7-dimethylamino propoxy side chain of UNC0224 indeed occupied the lysine binding channel of G9a. This explained the higher potency of UNC0224 compared to BIX-01294.56 The combination of high potency and good selectivity makes UNC0224 a potentially useful tool compound for the biomedical research community to further investigate the biology of G9a and its role in chromatin remodeling.

Discovering and developing high quality chemical probes58 of PKMTs is gaining momentum in both the academic research community and the pharmaceutical industry. Although PKMTs inhibitors are clinically unprecedented, they hold great promise as effective mono-therapies or synergizing agents in combination with existing therapeutics.59

4. Overview of Histone Acetylation – Tools and Technologies

The acetylation state of histones is primarily controlled by 2 familes of enzymes; Histone Acetyl Transferases (HAT) and Histone Deacetylases (HDAC) 60-62. As their names imply, the former add an ε-acetyl function to terminal lysines and the latter remove this modification. Both families have been extensively studied 9, 10, and in particular, there have been multiple successful drug discovery campaigns for inhibitors of HDACs 7, 63, 64 that eventually yielded several marketed drugs.

There are currently 18 known human HDAC isoforms that are commonly grouped into 4 families based on their homology to yeast HDACs, subcellular localization and enzymatic mechanism 65, 66. Class I HDACs (HDAC 1, 2, 3, and 8) are homologous to the yeast RPD3 protein, act as zinc dependent enzymes and are predominantly localized in the nucleus. These enzymes are ubiquitously expressed in human tissue. Class II HDACs (HDAC 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, and 10) share homology with the yeast Hda I protein, are also zinc dependent and in comparison to class II HDACs, are known to translocate between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Two HDACs (6 and 10) are unique within this class because they have two deacetylase domains 67, 68. HDAC6 is also distinctive in that it targets non-histone substrates 69 70. The class III HDACs are also known as sirtuins (SIRT 1–7) for their homology with the yeast SIR2 protein. These enzymes also have a unique enzymatic mechanism and require NAD+ for their activity. HDAC11 is the lone class IV HDAC. While it shares some sequence homology with both classes I and II, HDAC 11 is not zinc dependent.60.

Similar to the familiar enzymatic classes of kinases and phosphatases that add or remove phosphate groups from amino acids, the opposing nature of HDACs and HATs means that these two enzyme families can largely be monitored by the same technologies. Any technology that measures the relative presence of an acetyl group will be able to monitor either the addition or loss of acetyl moieties. While there are, of course, many radioactive methods for monitoring this activity, they are complicated by the need for pre-acetylated substrates for HDAC enzymes and the obvious drawbacks of waste disposal and safety71, 72.

The first technique developed for the non-radioactive measurement of HDAC activity was the Fluor-de-Lys® assay developed by Biomol (now Enzo Life Sciences). This assay is based on the deacetylation of a short lysine containing peptide substrate that is developed by trypsin digestion, which releases a proprietary fluorescent dye that fluoresces upon cleavage. Later versions of this assay are sold as a kit and use a green shifted (485ex/530em) dye which avoids some of the interference problems associated with small molecule compounds. The Fluor-de-Lys® assay came to prominence when it was reported that the compound resveratrol was a potent activator of the HDAC SIRT1 73. However, this finding has been disputed by later research that demonstrated that the purported activation was solely due to substrate specific interactions with the bulky dye group and the SIRT1 enzyme 74-76.

Other homogeneous assay technologies have been developed, for example a linked luminescent assay from Promega wherein deacetylation of an acetylated prolumigenic peptide substrate allows proteolytic cleavage and a subsequent luminescent readout. This offers a lower level of interference from compound libraries and increased sensitivity. Linked assays using luciferase to monitor NAD+ production in class III enzymes have also been reported 71.

Caliper Life Sciences Labchip™ technology can also be used to quantitatively measure the acetylation or deacetylation of a fluorescently labeled peptide substrate. In this system, the charge to mass ratio change associated with acetylation allows microfluidic, capillary electrophoresis-based separation and quantification of product and substrate from an HDAC or HAT enzymatic reaction71, 77. The ability to monitor both product and substrate makes this technique extremely precise and less prone to compound interference.

5. Conclusions

While the field is relatively new, there have been great strides in developing assays to monitor the PTM of histones and DNA through methylation and acetylation (Table 1). Given the growing importance of epigenetics in our understanding of human biology and the tractability of enzymes that target PTM of proteins for drug discovery, we can anticipate rapid development of new technologies to monitor the writers and erasers of the histone code. While the readers of the code are also of interest, their tractability for discovery of potent and selective small molecules is unproven. We can however be confident that new understanding of biology and new therapeutic agents will emerge as technology drives scientific understanding in epigenetics.

Table 1. Target classes and technologies involved in methylation and acetylation PTM of histones.

| Target Class | Detection Method | Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Methyltransferases | Colorimetric | ELISA 25 |

| TRF | DELFIA26 | |

| Chemiluminescence | AlphaScreen27 | |

| Fluorescence | Microfluidic capillary electrophoresis28 | |

| Radioactive | Incorporation of radioactive methyl groups 29, 30. | |

| Enzyme-coupled fluorescence | Thioglo chromophore31 or Ellman's reagent32, 33. | |

| Protein Demethylases | Enzyme-linked colorimetric | Formaldehyde dehydrogenase coupled reaction 35. |

| Colorimetric | Peroxide production 36, 37 | |

| Histone-Binding Proteins | Chemiluminescence | AlphaScreen 43, 44. |

| Histone Acetyl Transferases and Histone Deacetylases | Fluorescence | Fluor-de-Lys® assay73 |

| Luminescence | Prolumigenic peptide | |

| Fluorescence | Microfluidic capillary electrophoresis71, 77 |

Abbreviations

- HAT

Histone Acetyl Transferases

- HDAC

Histone Deacetylases

- ITC

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

- MBT

Maligant Brain Tumor

- PHD

Plant Homeodomain

- PRMT

Protein Arginine Methyltransferase

- PKDM

Protein Lysine Demethylase

- PKMT

Protein Lysine Methyltransferase

- PMT

Protein Methyltransferase

- SAM

S-adenosylmethionine

- TRF

Time Resolved Fluorescence

- PTM

Post-Translational Modifications

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Berger SL, Kouzarides T, Shiekhattar R, Shilatifard A. An operational definition of epigenetics. Genes Dev. 2009;23:781–3. doi: 10.1101/gad.1787609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein BE, Meissner A, Lander ES. The mammalian epigenome. Cell. 2007;128:669–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gelato KA, Fischle W. Role of histone modifications in defining chromatin structure and function. Biol Chem. 2008;389:353–63. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruthenburg AJ, Li H, Patel DJ, David Allis C. Multivalent engagement of chromatin modifications by linked binding modules. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:983–994. doi: 10.1038/nrm2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marmorstein R, Trievel RC. Histone modifying enzymes: structures, mechanisms, and specificities. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1789:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seet BT, Dikic I, Zhou MM, Pawson T. Reading protein modifications with interaction domains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:473–83. doi: 10.1038/nrm1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esteller M. Epigenetics in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1148–59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marks PA, Richon VM, Miller T, Kelly WK. Histone deacetylase inhibitors. Adv Cancer Res. 2004;91:137–68. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(04)91004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norvell A, McMahon SB. Rise of the Rival. Science. 2010;327:964–965. doi: 10.1126/science.1187159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haberland M, Montgomery RL, Olson EN. The many roles of histone deacetylases in development and physiology: implications for disease and therapy. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:32–42. doi: 10.1038/nrg2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rea S, Eisenhaber F, O'Carroll D, Strahl BD, Sun ZW, Schmid M, Opravil S, Mechtler K, Ponting CP, Allis CD, Jenuwein T. Regulation of chromatin structure by site-specific histone H3 methyltransferases. Nature. 2000;406:593–9. doi: 10.1038/35020506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin C, Zhang Y. The diverse functions of histone lysine methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:838–49. doi: 10.1038/nrm1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Copeland RA, Solomon ME, Richon VM. Protein methyltransferases as a target class for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:724–32. doi: 10.1038/nrd2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fog CK, Jensen KT, Lund AH. Chromatin-modifying proteins in cancer. APMIS. 2007;115:1060–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.apm_776.xml.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dillon SC, Zhang X, Trievel RC, Cheng X. The SET-domain protein superfamily: protein lysine methyltransferases. Genome Biol. 2005;6:227. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-8-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith BC, Denu JM. Chemical mechanisms of histone lysine and arginine modifications. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1789:45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams-Cioaba MA, Min J. Structure and function of histone methylation binding proteins. Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;87:93–105. doi: 10.1139/O08-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trojer P, Li G, Sims RJ, 3rd, Vaquero A, Kalakonda N, Boccuni P, Lee D, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Nimer SD, Wang YH, Reinberg D. L3MBTL1, a histone-methylation-dependent chromatin lock. Cell. 2007;129:915–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trojer P, Reinberg D. Beyond histone methyl-lysine binding: how malignant brain tumor (MBT) protein L3MBTL1 impacts chromatin structure. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:578–85. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.5.5544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horton JR, Upadhyay AK, Qi HH, Zhang X, Shi Y, Cheng X. Enzymatic and structural insights for substrate specificity of a family of jumonji histone lysine demethylases. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:38–43. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi Y, Lan F, Matson C, Mulligan P, Whetstine JR, Cole PA, Casero RA. Histone demethylation mediated by the nuclear amine oxidase homolog LSD1. Cell. 2004;119:941–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trewick SC, McLaughlin PJ, Allshire RC. Methylation: lost in hydroxylation? EMBO Rep. 2005;6:315–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGinty RK, Kohn M, Chatterjee C, Chiang KP, Pratt MR, Muir TW. Structure-activity analysis of semisynthetic nucleosomes: mechanistic insights into the stimulation of Dot1L by ubiquitylated histone H2B. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;4:958–68. doi: 10.1021/cb9002255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng D, Yadav N, King RW, Swanson MS, Weinstein EJ, Bedford MT. Small molecule regulators of protein arginine methyltransferases. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23892–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401853200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kubicek S, O'Sullivan RJ, August EM, Hickey ER, Zhang Q, Teodoro ML, Rea S, Mechtler K, Kowalski JA, Homon CA, Kelly TA, Jenuwein T. Reversal of H3K9me2 by a small-molecule inhibitor for the G9a histone methyltransferase. Mol Cell. 2007;25:473–81. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quinn AM, Allali-Hassani A, Vedadi M, Simeonov A. A chemiluminescence-based method for identification of histone lysine methyltransferase inhibitors. Molecular BioSystems. 2010 doi: 10.1039/B921912A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wigle TJ, Provencher LM, Norris JL, Jin J, Brown PJ, Frye SV, Janzen WP. Accessing Protein Methyltransferase and Demethylase Enzymology Using Microfluidic Capillary Electrophoresis Chemistry and Biology. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.04.014. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gowher H, Zhang X, Cheng X, Jeltsch A. Avidin plate assay system for enzymatic characterization of a histone lysine methyltransferase. Anal Biochem. 2005;342:287–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dhayalan A, Dimitrova E, Rathert P, Jeltsch A. A continuous protein methyltransferase (G9a) assay for enzyme activity measurement and inhibitor screening. J Biomol Screen. 2009;14:1129–33. doi: 10.1177/1087057109345528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collazo E, Couture JF, Bulfer S, Trievel RC. A coupled fluorescent assay for histone methyltransferases. Anal Biochem. 2005;342:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hendricks CL, Ross JR, Pichersky E, Noel JP, Zhou ZS. An enzyme-coupled colorimetric assay for S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases. Anal Biochem. 2004;326:100–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dorgan KM, Wooderchak WL, Wynn DP, Karschner EL, Alfaro JF, Cui Y, Zhou ZS, Hevel JM. An enzyme-coupled continuous spectrophotometric assay for S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases. Anal Biochem. 2006;350:249–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lizcano JM, Unzeta M, Tipton KF. A spectrophotometric method for determining the oxidative deamination of methylamine by the amine oxidases. Anal Biochem. 2000;286:75–9. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sakurai M, Rose NR, Schultz L, Quinn AM, Jadhav A, Ng SS, Oppermann U, Schofield CJ, Simeonov A. A miniaturized screen for inhibitors of Jumonji histone demethylases. Mol Biosyst. 2010;6:357–64. doi: 10.1039/b912993f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forneris F, Binda C, Vanoni MA, Mattevi A, Battaglioli E. Histone demethylation catalysed by LSD1 is a flavin-dependent oxidative process. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:2203–7. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang Y, Greene E, Murray Stewart T, Goodwin AC, Baylin SB, Woster PM, Casero RA., Jr Inhibition of lysine-specific demethylase 1 by polyamine analogues results in reexpression of aberrantly silenced genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8023–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700720104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garske AL, Oliver SS, Wagner EK, Musselman CA, LeRoy G, Garcia BA, Kutateladze TG, Denu JM. Combinatorial profiling of chromatin binding modules reveals multisite discrimination. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:283–90. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacobs SA, Fischle W, Khorasanizadeh S. Assays for the determination of structure and dynamics of the interaction of the chromodomain with histone peptides. Methods Enzymol. 2004;376:131–48. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)76009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Min J, Allali-Hassani A, Nady N, Qi C, Ouyang H, Liu Y, MacKenzie F, Vedadi M, Arrowsmith CH. L3MBTL1 recognition of mono- and dimethylated histones. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1229–30. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li H, Fischle W, Wang W, Duncan EM, Liang L, Murakami-Ishibe S, Allis CD, Patel DJ. Structural basis for lower lysine methylation state-specific readout by MBT repeats of L3MBTL1 and an engineered PHD finger. Mol Cell. 2007;28:677–91. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santiveri CM, Lechtenberg BC, Allen MD, Sathyamurthy A, Jaulent AM, Freund SM, Bycroft M. The malignant brain tumor repeats of human SCML2 bind to peptides containing monomethylated lysine. J Mol Biol. 2008;382:1107–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wigle TJ, Herold JM, Senisterra GA, Vedadi M, Kireev DB, Arrowsmith CH, Frye SV, Janzen WP. Screening for inhibitors of low-affinity epigenetic peptide-protein interactions: an AlphaScreen-based assay for antagonists of methyl-lysine binding proteins. J Biomol Screen. 2010;15:62–71. doi: 10.1177/1087057109352902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quinn AM, Bedford MT, Espejo A, Spannhoff A, Austin CP, Oppermann U, Simeonov A. A homogeneous method for investigation of methylation-dependent protein-protein interactions in epigenetics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spannhoff A, Sippl W, Jung M. Cancer treatment of the future: inhibitors of histone methyltransferases. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Copeland RA, Solomon ME, Richon VM. Protein methyltransferases as a target class for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:724–732. doi: 10.1038/nrd2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spannhoff A, Hauser AT, Heinke R, Sippl W, Jung M. The emerging therapeutic potential of histone methyltransferase and demethylase inhibitors. ChemMedChem. 2009;4:1568–82. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200900301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Y, Reddy MA, Miao F, Shanmugam N, Yee JK, Hawkins D, Ren B, Natarajan R. Role of the Histone H3 Lysine 4 Methyltransferase, SET7/9, in the Regulation of NF-{kappa}B-dependent Inflammatory Genes: RELEVANCE TO DIABETES AND INFLAMMATION. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:26771–26781. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802800200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maze I, Covington HE, 3rd, Dietz DM, LaPlant Q, Renthal W, Russo SJ, Mechanic M, Mouzon E, Neve RL, Haggarty SJ, Ren Y, Sampath SC, Hurd YL, Greengard P, Tarakhovsky A, Schaefer A, Nestler EJ. Essential role of the histone methyltransferase G9a in cocaine-induced plasticity. Science. 2010;327:213–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1179438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schaefer A, Sampath SC, Intrator A, Min A, Gertler TS, Surmeier DJ, Tarakhovsky A, Greengard P. Control of Cognition and Adaptive Behavior by the GLP/G9a Epigenetic Suppressor Complex. Neuron. 2009;64:678–691. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McGarvey KM, Fahrner JA, Greene E, Martens J, Jenuwein T, Baylin SB. Silenced tumor suppressor genes reactivated by DNA demethylation do not return to a fully euchromatic chromatin state. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3541–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kondo Y, Shen L, Ahmed S, Boumber Y, Sekido Y, Haddad BR, Issa JP. Downregulation of histone H3 lysine 9 methyltransferase G9a induces centrosome disruption and chromosome instability in cancer cells. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang J, Dorsey J, Chuikov S, Zhang X, Jenuwein T, Reinberg D, Berger SL. G9A and GLP methylate lysine 373 in the tumor suppressor p53. J Biol Chem. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.062588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cole PA. Chemical probes for histone-modifying enzymes. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:590–7. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Greiner D, Bonaldi T, Eskeland R, Roemer E, Imhof A. Identification of a specific inhibitor of the histone methyltransferase SU(VAR)3-9. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:143–5. doi: 10.1038/nchembio721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu F, Chen X, Allali-Hassani A, Quinn AM, Wasney GA, Dong A, Barsyte D, Kozieradzki I, Senisterra G, Chau I, Siarheyeva A, Kireev DB, Jadhav A, Herold JM, Frye SV, Arrowsmith CH, Brown PJ, Simeonov A, Vedadi M, Jin J. Discovery of a 2,4-diamino-7-aminoalkoxyquinazoline as a potent and selective inhibitor of histone lysine methyltransferase G9a. J Med Chem. 2009;52:7950–3. doi: 10.1021/jm901543m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chang Y, Zhang X, Horton JR, Upadhyay AK, Spannhoff A, Liu J, Snyder JP, Bedford MT, Cheng X. Structural basis for G9a-like protein lysine methyltransferase inhibition by BIX-01294. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:312–7. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Frye SV. The art of the chemical probe. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:159–161. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Simon JA, Lange CA. Roles of the EZH2 histone methyltransferase in cancer epigenetics. Mutat Res. 2008;647:21–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roth SY, Denu JM, Allis CD. Histone acetyltransferases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:81–120. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marmorstein R, Roth SY. Histone acetyltransferases: function, structure, and catalysis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001;11:155–61. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marks PA, Miller T, Richon VM. Histone deacetylases. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2003;3:344–51. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(03)00084-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marks P, Breslow R. Dimethyl sulfoxide to vorinostat: development of this histone deacetylase inhibitor as an anticancer drug. Nature biotechnology. 2007;25:84–90. doi: 10.1038/nbt1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Müller S, Krämer O. Inhibitors of HDACs-Effective Drugs Against Cancer. Current cancer drug targets. doi: 10.2174/156800910791054149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bolden JE, Peart MJ, Johnstone RW. Anticancer activities of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:769–84. doi: 10.1038/nrd2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gallinari P, Di Marco S, Jones P, Pallaoro M, Steinkühler C. HDACs, histone deacetylation and gene transcription: from molecular biology to cancer therapeutics. Cell research. 2007;17:195–211. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grozinger CM, Hassig CA, Schreiber SL. Three proteins define a class of human histone deacetylases related to yeast Hda1p. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4868–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guardiola AR, Yao TP. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel histone deacetylase HDAC10. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3350–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109861200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hubbert C, Guardiola A, Shao R, Kawaguchi Y, Ito A, Nixon A, Yoshida M, Wang XF, Yao TP. HDAC6 is a microtubule-associated deacetylase. Nature. 2002;417:455–8. doi: 10.1038/417455a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kovacs J, Murphy P, Gaillard S, Zhao X, Wu J, Nicchitta C, Yoshida M, Toft D, Pratt W, Yao T. HDAC6 regulates Hsp90 acetylation and chaperone-dependent activation of glucocorticoid receptor. Molecular cell. 2005;18:601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu Y, Gerber R, Wu J, Tsuruda T, McCarter JD. High-throughput assays for sirtuin enzymes: a microfluidic mobility shift assay and a bioluminescence assay. Anal Biochem. 2008;378:53–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Heltweg B, Trapp J, Jung M. In vitro assays for the determination of histone deacetylase activity. Methods. 2005;36:332–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Howitz KT, Bitterman KJ, Cohen HY, Lamming DW, Lavu S, Wood JG, Zipkin RE, Chung P, Kisielewski A, Zhang LL, Scherer B, Sinclair DA. Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan. Nature. 2003;425:191–6. doi: 10.1038/nature01960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Borra MT, Smith BC, Denu JM. Mechanism of human SIRT1 activation by resveratrol. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17187–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pacholec M, Bleasdale JE, Chrunyk B, Cunningham D, Flynn D, Garofalo RS, Griffith D, Griffor M, Loulakis P, Pabst B, Qiu XY, Stockman B, Thanabal V, Varghese A, Ward J, Withka J, Ahn K. SRT1720, SRT2183, SRT1460, and Resveratrol Are Not Direct Activators of SIRT1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285:8340–8351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.088682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kaeberlein M, McDonagh T, Heltweg B, Hixon J, Westman EA, Caldwell SD, Napper A, Curtis R, DiStefano PS, Fields S, Bedalov A, Kennedy BK. Substrate-specific activation of sirtuins by resveratrol. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17038–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500655200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Blackwell L, Norris J, Suto CM, Janzen WP. The use of diversity profiling to characterize chemical modulators of the histone deacetylases. Life Sci. 2008;82:1050–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]