Abstract

Summary: Accurate prediction of transcription factor binding motifs that are enriched in a collection of sequences remains a computational challenge. Here we report on GimmeMotifs, a pipeline that incorporates an ensemble of computational tools to predict motifs de novo from ChIP-sequencing (ChIP-seq) data. Similar redundant motifs are compared using the weighted information content (WIC) similarity score and clustered using an iterative procedure. A comprehensive output report is generated with several different evaluation metrics to compare and evaluate the results. Benchmarks show that the method performs well on human and mouse ChIP-seq datasets. GimmeMotifs consists of a suite of command-line scripts that can be easily implemented in a ChIP-seq analysis pipeline.

Availability: GimmeMotifs is implemented in Python and runs on Linux. The source code is freely available for download at http://www.ncmls.eu/bioinfo/gimmemotifs/.

Contact: s.vanheeringen@ncmls.ru.nl

Supplementary Information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

The spectacular development of sequencing technology has enabled rapid, cost-efficient profiling of DNA binding proteins. Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput deep sequencing (ChIP-seq) delivers high-resolution binding profiles of transcription factors (TFs) (Park, 2009). The elucidation of the binding characteristics of these TFs is one of the obvious follow-up questions. However, the de novo identification of DNA sequence motifs remains a challenging computational task. Although many methods have been developed with varying degrees of success, no single method consistently performs well on real biological eukaryotic data (Tompa et al., 2005). The combination of different algorithmic approaches, each with its own strengths and weaknesses, has been shown to improve prediction accuracy and sensitivity over single methods (Hu et al., 2005).

Here, we report on GimmeMotifs, a motif prediction pipeline using a ensemble of existing computational tools (Supplementary Fig. S1). This pipeline has been specifically developed to predict TF motifs from ChIP-seq data. It uses the wealth of sequences (binding peaks) usually resulting from ChIP-seq experiments to both predict motifs de novo, as well as validate these motifs in an independent fraction of the dataset.

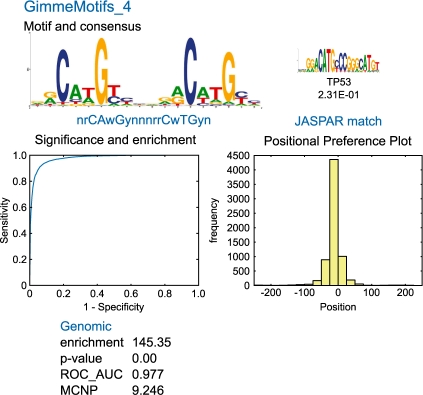

GimmeMotifs incorporates the weighted information content (WIC) similarity metric in an iterative clustering procedure to cluster similar motifs and reduce the redundancy which is the result of combining the output of different tools (see Supplementary Material). It produces an extensive graphical report with several evaluation metrics to enable interpretion of the results (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

An example of the GimmeMotifs output for p63 (Kouwenhoven et al., 2010). Shown are the sequence logo of the predicted motif (Schneider and Stephens, 1990), the best matching motif in the JASPAR database (Sandelin et al., 2004), the ROC curve, the positional preference plot and several statistics to evaluate the motif performance. See the Supplementary Material for a complete example.

2 METHODS

2.1 Overview

The input for GimmeMotifs is a file in BED format containing genomic coordinates, e.g. peaks from a ChIP-seq experiment or a FASTA file. This dataset is split: a prediction set contains randomly selected sequences from the input dataset (20% of the sequences by default) and is used for motif prediction with several different computational tools. Predicted motifs are filtered for significance using all remaining sequences (the validation set), clustered using the WIC score as described below, and a list of non-redundant motifs is generated.

2.2 Motif similarity and clustering

The WIC similarity score is based on the information content (IC) and is defined for position i in motif X compared with position j of motif Y as:

| (1) |

where c is 2.5, and DIC(Xi, Yj) is the differential IC defined in Equation (3). The IC of a specific motif position is defined as:

| (2) |

where IC(Xi) is the IC of position i of motif X, fxi,n is the frequency of nucleotide n at position i and fbg is the background frequency (0.25). The differential IC (DIC) of position i in motif X and position j in motif Y is defined as:

| (3) |

The WIC score of all individual positions in the alignment is summed to determine the total WIC score of two aligned motifs. To calculate the maximum WIC score of two motifs, all possible scores of all alignments are calculated, and the maximum scoring alignment is kept. Similar motifs are clustered using an iterative pair-wise clustering procedure (Supplementary Material).

2.3 Evaluation

The motifs can be evaluated using several different statistics: the absolute enrichment, the hypergeometric P-value, a receiver operator characteristic (ROC) graph, the ROC area under the curve (AUC) and the mean normalized conditional probability (MNCP) (Clarke and Granek, 2003). In addition to these evaluation metrics, GimmeMotifs generates a histogram of the motif position relative to the peak summit, the positional preference plot. Especially in case of high-resolution ChIP-seq data, this gives valuable information on the motif location.

2.4 Implementation

The GimmeMotifs package is implemented in Python, while the similarity metrics are written as a C extension module for performance reasons. It is freely available under the MIT license. Sequence logos are generated using WebLogo (Schneider and Stephens, 1990).

3 BENCHMARK RESULTS

We performed a benchmark study of GimmeMotifs on 18 TF ChIP-seq datasets. The ROC AUC and MNCP of the best performing motif were calculated and compared with the best motif of two other ensemble methods: SCOPE (Carlson et al., 2007) and W-ChipMotifs (Jin et al., 2009) (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2) . The results show that GimmeMotifs consistently produces accurate results (median ROC AUC 0.830). The method also significantly improves on the results of SCOPE (ROC AUC 0.613). The recently developed W-ChIPmotifs shows comparable results to GimmeMotifs (ROC AUC 0.824), although this tool does not cluster similar redundant motifs. In addition, the focus of GimmeMotifs is different. While the web interface of W-ChipMotifs is very useful for casual use, the command-line tools of GimmeMotifs can be integrated in more sophisticated analysis pipelines.

4 CONCLUSION

We present GimmeMotifs, a de novo motif prediction pipeline ideally suited to predict transcription factor binding motifs from ChIP-seq datasets. GimmeMotifs clusters the results of several different tools and produces a comprehensive report to evaluate the predicted motifs. We show that GimmeMotifs performs well on biologically relevant datasets of different TFs and compares favorably to other methods.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all the authors of the computational tools for their publicly available software. We are grateful to W. Akhtar, R.C. Akkers, S.J. Bartels, A. Costessi, M. Koeppel, E.N. Kouwenhoven, M. Lohrum, J.H. Martens, N.A.S. Rao, L. Smeenk and H. Zhou for data, testing and feedback.

Funding: NWO-ALW (Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research-Research Council for Earth and Life Sciences, grant number 864.03.002); National Institutes of Health (grant number R01HD054356) with grants to G.J.C.V.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Carlson JM, et al. SCOPE: a web server for practical de novo motif discovery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(suppl. 2):W259–W264. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke ND, Granek JA. Rank order metrics for quantifying the association of sequence features with gene regulation. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:212–218. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, et al. Limitations and potentials of current motif discovery algorithms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:4899–4913. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin VX, et al. W-ChIPMotifs: a web application tool for de novo motif discovery from ChIP-based high-throughput data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:3191–3193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouwenhoven EN, et al. Genome-Wide profiling of p63 DNA-Binding sites identifies an element that regulates gene expression during limb development in the 7q21 SHFM1 locus. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001065. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park PJ. ChIP-seq: advantages and challenges of a maturing technology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:669–680. doi: 10.1038/nrg2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelin A, et al. JASPAR: an open-access database for eukaryotic transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(suppl. 1):D91–D94. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider TD, Stephens R. Sequence logos: a new way to display consensus sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6097–6100. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.20.6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompa M, et al. Assessing computational tools for the discovery of transcription factor binding sites. Nat. Biotech. 2005;23:137–144. doi: 10.1038/nbt1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.