Abstract

Here we show that the extent of electron flow through the cbb3 oxidase of Rhodobacter sphaeroides is inversely related to the expression levels of those photosynthesis genes that are under control of the PrrBA two-component activation system: the greater the electron flow, the stronger the inhibitory signal generated by the cbb3 oxidase to repress photosynthesis gene expression. Using site-directed mutagenesis, we show that intramolecular electron transfer within the cbb3 oxidase is involved in signal generation and transduction and this signal does not directly involve the intervention of molecular oxygen. In addition to the cbb3 oxidase, the redox state of the quinone pool controls the transcription rate of the puc operon via the AppA–PpsR antirepressor–repressor system. Together, these interacting regulatory circuits are depicted in a model that permits us to understand the regulation by oxygen and light of photosynthesis gene expression in R.sphaeroides.

Keywords: cbb3 cytochrome c oxidase/electron transport chain/gene regulation/photosynthesis/redox sensing

Introduction

The primary environmental factor that governs the expression of the photosynthesis (PS) genes in Rhodobacter sphaeroides, is oxygen. The photosynthetic apparatus is synthesized when oxygen tensions fall below ∼2.5% (Kiley and Kaplan, 1988). Under anaerobic conditions in the light the cellular level of the B800–850 complex relative to the B875 complex increases differentially and inversely to the incident light intensity (Kiley and Kaplan, 1988; Zeilstra-Ryalls et al., 1998).

Transcriptional regulation of the PS genes in R.sphaeroides is achieved by the coordinate action of at least three major regulatory systems: the PrrBA two-component activation system, the AppA–PpsR antirepressor–repressor system and FnrL. The PrrBA two-component system functions as a global anaerobic activation system (Eraso and Kaplan, 1994, 1996; Joshi and Tabita, 1996; Qian and Tabita, 1996). PpsR is a redox-responding protein that is responsible for the aerobic and high-light repression of the puc operon and photopigment biosynthesis genes such as crt and bch (Gomelsky and Kaplan, 1995a; Oh and Kaplan, 2000). The AppA protein appears to modulate the activity of PpsR in response to changes in cellular redox state (Gomelsky and Kaplan, 1995b, 1997, 1998). FnrL, the homolog of the global anaerobic regulator Fnr, is required for the enhanced expression of selective PS genes (puc, hemA, hemN, hemZ and bchE) and the ccoNOQP operon encoding the cbb3 oxidase, as well as for the expression of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) reductase in R.sphaeroides under oxygen- limiting conditions (Zeilstra-Ryalls et al., 1995, 1997; Zeilstra-Ryalls and Kaplan, 1998; Mouncey and Kaplan, 1998a,b; Oh et al., 2000).

When grown aerobically, R.sphaeroides contains a branched aerobic electron transport chain (ETC) that is terminated with two functional cytochrome c oxidases and at least one functional quinol oxidase (Hosler et al., 1992; Shapleigh et al., 1992; Garcia-Horsman et al., 1994b; N.J.Mouncey, E.Gak, M.Choudhary, J.Oh and S.Kaplan, in preparation). The aa3- and cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidases belong to the heme–copper oxidase superfamily (Garcia-Horsman et al., 1994a) and take electrons from the bc1 complex through both cytochromes c2 and cy (Donohue et al., 1988; Myllykallio et al., 1999). Rhodobacter capsulatus, a bacterium phylogenetically very close to R.sphaeroides, does not contain the aa3 cytochrome c oxidase. The cbb3 oxidase encoded by the ccoNOQP operon consists of four non-identical subunits (Toledo-Cuevas et al., 1998). CcoN is the catalytic subunit where the reduction of O2 occurs, while CcoO and CcoP are monoheme and diheme cytochromes c, respectively. CcoQ is the smallest subunit and is not required for cbb3 oxidase activity (Zufferey et al., 1998; Oh and Kaplan, 1999).

Cohen-Bazire et al. (1956) first proposed that the redox state of the ETC might ultimately control the levels of the spectral complexes in R.sphaeroides in response to changes in oxygen tension and light intensity. The finding that mutations in the ccoNOQP operon led to the formation of spectral complexes even under high oxygen conditions provided the first clue that the cbb3 cytochrome c oxidase might be an O2/redox sensor (Zeilstra-Ryalls and Kaplan, 1996; O’Gara and Kaplan, 1997). We proposed that the cbb3 oxidase transduces an inhibitory signal to the PrrBA two-component system under aerobic conditions to prevent PS gene expression (O’Gara et al., 1998; Oh and Kaplan, 1999; Oh et al., 2000). However, the nature of the signal and the mechanism by which the cbb3 oxidase perceives the signal remained to be determined.

In this report we present evidence suggesting that the extent of electron flux through the cbb3 cytochrome c oxidase determines the expression levels of the PS genes that are under control of the PrrBA two-component system. The dual function of the cbb3 oxidase as both terminal oxidase and O2 sensor represents a novel mode of redox sensing. Furthermore, we present the first evidence that the redox state of the quinone pool in the ETC can provide a cbb3-independent signal that is likely to be sensed and transduced by the AppA–PpsR antirepressor–repressor system.

Results

Growth and spectral complex formation in ETC mutant strains of R.sphaeroides under aerobic conditions

When grown on SIS agar plates under aerobic conditions, the BC1 and C2Cy mutant strains formed colonies with very deep red pigmentation, compared with the relatively pale pink coloration of the wild type. This phenotype, designated ‘oxygen-insensitive spectral complex formation’, was previously observed for Cco mutant strains as well as the RdxB insertion mutant (RDXB1) (O’Gara and Kaplan, 1997; Oh and Kaplan, 1999). Colonies of the Cy mutant exhibited somewhat greater pigmentation than those of the wild type. In contrast, the C2 or AA3 mutant strains produced colonies with similar coloration to those of the wild-type strain 2.4.1. Under 30% O2 conditions, growth rates of all ETC mutants with the exception of the BC1 and C2Cy mutant strains were not significantly different. The latter mutants relying exclusively on quinol oxidase function had an ∼2-fold greater doubling time than the wild-type strain.

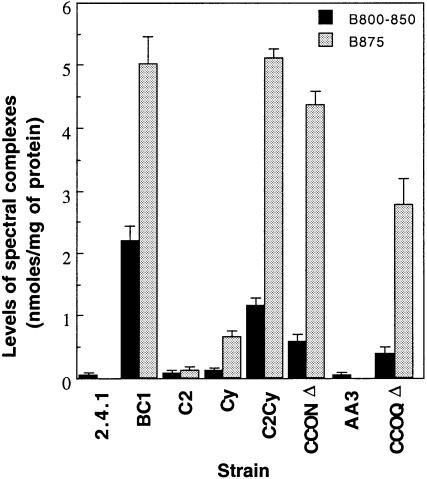

All ETC mutant strains were cultivated under 30% O2, along with the wild type, and the levels of spectral complexes were quantitatively determined. As shown in Figure 1, the mutants are divided roughly into three groups. The first group comprised the C2 and AA3 mutants which, like the wild-type strain 2.4.1, produced only background levels of spectral complexes. The second group consisted of the BC1, C2Cy, CCONΔ and CCOQΔ mutant strains where spectral complex formation was orders of magnitude higher when compared with the wild type. Approximately the same amounts of B875 complex were produced in the mutants of this group with the exception of the CCOQΔ mutant, whereas the levels of the B800–850 complex showed greater variation (BC1>C2Cy>CCONΔ>CCOQΔ). The Cy mutant belonged to the third group. Although the Cy mutant synthesized spectral complexes in the presence of 30% O2, the levels were well below those observed for the mutants of group two.

Fig. 1. Levels of spectral complexes in R.sphaeroides strains grown under aerobic conditions. Strains were grown aerobically by sparging with 30% O2–69% N2–1% CO2 to an OD600 of 0.5. The black and gray bars indicate the levels of B800–850 and B875 light harvesting complexes, respectively. All values provided are the average of two independent determinations. Vertical bars represent the standard deviation from the mean.

PS gene expression in ETC mutants of R.sphaeroides under aerobic conditions

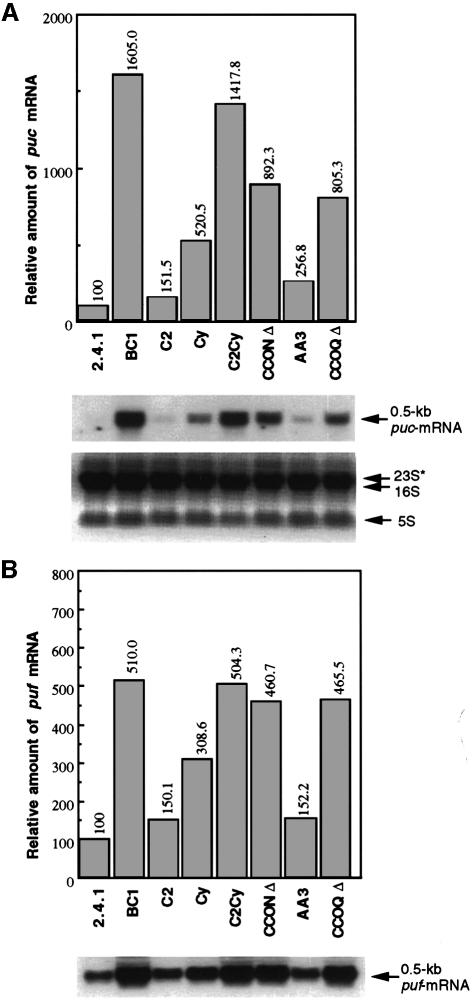

The expression of the puc and puf operons, which encode the apoproteins of the B800–850 and B875 complexes, respectively, was investigated at the transcriptional level by means of northern hybridization analyses using total RNA isolated from the wild-type and mutant strains grown under 30% O2. As shown in Figure 2A, the levels of puc transcripts were increased in the BC1, C2Cy, CCONΔ and CCOQΔ mutants by a factor of 8–16, compared with the wild type. The Cy mutant showed an ∼5-fold increase in puc operon expression when compared with the wild type, whereas only marginal derepression of puc operon expression was observed in the C2 and AA3 mutants.

Fig. 2. Analysis of mRNA levels specific for puc (A) and puf (B) in R.sphaeroides strains grown under aerobic conditions. Total RNA was isolated from R.sphaeroides strains grown aerobically as described for Figure 1. Approximately 20 µg of total RNA was loaded in each lane. The northern blots were probed with a labeled 0.53 kb BamHI–KpnI fragment from pUI624 and a 0.47 kb StyI fragment from pUI655, which are specific for puc- and puf-mRNA, respectively. The levels of transcripts were quantitated as described. After background correction, the values were normalized by the levels of processed 23S (23S*) and 16S rRNA. The normalized values are plotted above the northern blots. The transcript levels in the wild type (2.4.1) are set at 100.

The trend in puf operon derepression in the mutants grown under 30% O2 was similar to that observed for the puc operon, although the more extreme variations in mRNA levels observed for the latter were dampened in the former (Figure 2B). What is striking is the relatively consistent levels of derepression of the puf operon in the BC1, C2Cy, CCONΔ and CCOQΔ mutant strains (∼6% variation), which is not true for puc operon expression (∼24% variation).

Contributions of the aa3 and cbb3 terminal oxidases to the electron flux of the ETC

As shown in Table I, the CCONΔ and AA3 mutant strains exhibited ∼70.5 and 35.7% of the cytochrome c oxidase activity present in the wild type 2.4.1, respectively, when grown under 30% O2 conditions. This indicates that in R.sphaeroides 2.4.1 grown under 30% O2 conditions the bulk of the reducing equivalents moving to O2 are proceeding through the aa3 terminal oxidase. Yet, inactivation of the aa3 oxidase did not lead to the oxygen-insensitive formation of spectral complexes. This observation is crucial to the conclusion that derepression of PS genes observed in the CCONΔ mutant is not a consequence of changes in the ‘redox state’ of electron carriers upstream of the cbb3 oxidase, e.g. the bc1 complex and quinone pool, etc. This fortifies our previous proposal that the cbb3 oxidase per se functions as an O2/redox sensor and generates the inhibitory signal that represses PS gene expression in the presence of O2.

Table I. Cytochrome c oxidase activities from R.sphaeroides strains.

| Strain | Relative cytochrome c oxidase activity (%)a | Specific activity of cbb3 (µmol/min/mg protein)b |

|---|---|---|

| 2.4.1 | 100 | 1.32 ± 0.01 |

| BC1 | n.d. | 1.15 ± 0.01 |

| C2 | n.d. | 1.37 ± 0.03 |

| Cy | n.d. | 1.33 ± 0.10 |

| C2Cy | n.d. | 0.97 ± 0.02 |

| CCONΔ | 70.5 | 0.06 ± 0.00 |

| AA3 | 35.7 | 1.23 ± 0.02 |

| CCOQΔ | n.d. | 1.16 ± 0.05 |

aCytochrome c oxidase activities from cells grown aerobically by sparging with 30% O2–69% N2–1% CO2 to an OD600 of 0.5–0.6. Oxygen consumption was measured polarographically with an oxygen electrode. The rate of oxygen consumption of the wild-type membrane fraction is set at 100 and the relative activity is expressed for the other strains. n.d., not determined.

bStrains were grown anaerobically in the dark with DMSO as a terminal electron acceptor. Cytochrome c oxidase activity was measured spectrophotometrically by monitoring the oxidation of pre-reduced horse heart cytochrome c. All values provided are the average of two independent determinations.

It is the functional state of the cbb3 oxidase that determines PS gene expression

If we assume that the cbb3 oxidase is the actual O2/redox sensor, we can then ask how derepression of the puc and puf operons occurs in the BC1 and C2Cy mutant strains under aerobic conditions. A first possibility is that inactivation of these electron carriers might affect either the transcription of the ccoNOQP operon or the assembly and/or maturation of the cbb3 oxidase post-transcriptionally. We therefore determined the activity of the cbb3 oxidase in the mutant and wild type grown under anaerobic dark–DMSO conditions where the cbb3 oxidase is the exclusive cytochrome c oxidase synthesized in R.sphaeroides (Table I). As expected, the CCONΔ mutant exhibited virtually no cytochrome c oxidase activity. In contrast, high cbb3 oxidase activities were detected in the wild type and other mutant strains. Therefore, preventing the flow of reducing equivalents to the cbb3 oxidase affects neither transcription of the ccoNOQP operon nor assembly/activity of the cbb3 oxidase.

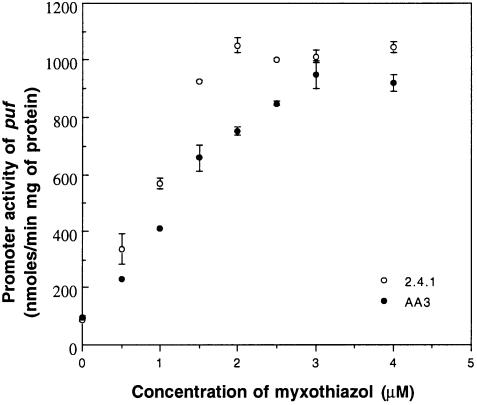

A second possibility is that interruption of electron flow to the cbb3 oxidase resulting from inactivation of the upstream electron carriers might render the cbb3 oxidase incapable of generating an inhibitory signal in the presence of O2. Using a puf::lacZ transcriptional fusion, we examined the effect of the bc1 complex-specific inhibitor myxothiazol upon puf operon expression in both the wild type and AA3 mutant grown under 30% O2. Figure 3 shows that the promoter activity of the puf operon increased with increasing myxothiazol concentration. Importantly, higher promoter activity of puf was observed in the wild type at a given concentration of myxothiazol than in the AA3 mutant. Furthermore, promoter activity reached maximal levels at a lower concentration of myxothiazol in the wild type (2 µM) than in the AA3 mutant (3 µM), although the ultimate level of promoter activity was the same for both strains. The concentration of myxothiazol that gave half-maximal puf promoter activity was ∼1 and 1.3 µM for the wild-type and AA3 mutant strains, respectively.

Fig. 3. Effect of myxothiazol on the expression of puf in the wild-type and AA3 mutant strains of R.sphaeroides grown under aerobic conditions. The wild-type (2.4.1) and AA3 mutant strains harboring the puf::lacZ transcriptional fusion plasmid pUI1663 were grown aerobically by sparging with 30% O2–69% N2–1% CO2 to an OD600 of ∼0.25–0.3. After addition of a given concentration of myxothiazol dissolved in methanol, the cultures were grown under the same growth conditions for an additional 3 h. Cell-free crude extracts were used to determine β-galactosidase activity. All values provided are the average of three independent determinations. Error bars represent the standard deviation from the mean.

What caused the differences in the kinetic behavior of puf operon expression between the wild type and the AA3 mutant as a function of myxothiazol concentration under high oxygen conditions? The most plausible explanation is that there are more electrons available to the cbb3 oxidase in the AA3 mutant in the presence of myxothiazol. Therefore, our hypothesis that the extent of electron flow through the cbb3 oxidase determines the expression levels of the PS genes that are under control of the PrrBA two-component system, is supported.

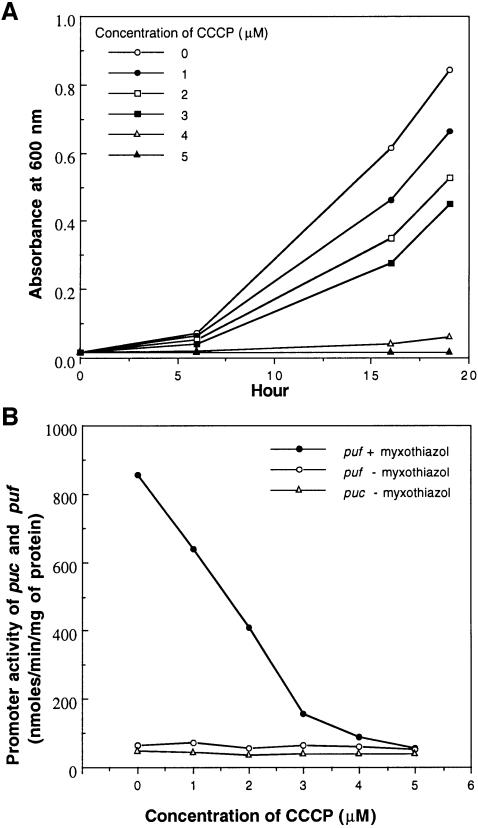

Another possibility is that it is a reduction in the proton motive force or cellular energy charge (ATP/ADP) that brings about derepression of the puc and puf operons in the BC1 and C2Cy mutants grown under 30% O2 conditions. To address this point, we investigated the effect of an uncoupler of oxidative phosphorylation upon puc and puf operon expression in the wild type 2.4.1 grown under 30% O2. As shown in Figure 4A, the growth rate of 2.4.1 was inversely related to the concentration of carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP) in the growth medium and growth ceased in the presence of 5 µM CCCP. As shown in Figure 4B, the expression of both puc and puf remained at basal levels regardless of an increase in CCCP concentration. However, the addition of 3 µM myxothiazol induced puf expression in the presence of 1–4 µM CCCP. These data and those above clearly suggest that it is not a decrease in the proton motive force and/or cellular levels of ATP but the blocking of electron flow through the bc1 complex to the cbb3 oxidase that causes derepression of puc and puf operon expression in the BC1 and C2Cy mutant strains.

Fig. 4. Effect of CCCP on the growth of R.sphaeroides 2.4.1 (A) and the expression of puc and puf in R.sphaeroides 2.4.1 grown under aerobic conditions (B). Growth curves were determined by cultivating the wild type 2.4.1 under aerobic conditions in SIS medium containing a given concentration of CCCP. The wild type 2.4.1 harboring either puf::lacZ (pUI1663) or puc::lacZ transcriptional plasmid (pCF200Km) was grown aerobically as described for Figure 3. After addition of a given concentration of CCCP dissolved in ethanol, cultivation continued under the same growth conditions for an additional 3 h. Myxothiazol was added to the control group (2.4.1 containing pUI1663) to a final concentration of 3 µM in addition to CCCP. Cell-free crude extracts were used to determine β-galactosidase activity.

Structural and functional integrity of the cbb3 oxidase is required for its O2-sensing and signal transduction capacity

The catalytic subunit (CcoN) of the cbb3 oxidase has a low spin heme b and a binuclear center composed of a high spin heme b3 and CuB, which are involved in intramolecular electron transfer and substrate binding (Garcia-Horsman et al., 1994a; Toledo-Cuevas et al., 1998). Those histidine residues proposed to ligate the low and high spin hemes as well as the CuB (Iwata et al., 1995; Zufferey et al., 1998) were changed to alanine by site-directed mutagenesis (His405, His407 and His267 provide the ligands to the high and low spin hemes, and CuB, respectively).

We first examined the effect of the histidine to alanine replacements upon spectral complex formation in the mutants grown under 30% O2 conditions (Table II). The positive control strain CCONΔ (pUI2803) produced only basal levels of the light harvesting complexes under 30% O2 conditions, like the wild type 2.4.1 (pRK415), indicating that the in-frame deletion of ccoN in the CCONΔ mutant is fully complemented by pUI2803. In contrast, the H405A, H407A and H267A mutants as well as the negative control strain CCONΔ (pRK415) exhibited 7- to 8-fold and 22- to 25-fold increased levels of the B800–850 and B875 complexes, respectively, when compared with the positive control strain 2.4.1 (pRK415).

Table II. Relevant phenotypes of a set of histidine replacement mutants of catalytic subunit (CcoN) of R.sphaeroides cbb3 oxidase.

| Strain | Plasmid | 30% O2a |

Dark–DMSOb |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B800–850 | B875 | cbb3 activity | ||

| 2.4.1 | pRK415 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 1.20 ± 0.06 |

| CCONΔ | pRK415 | 0.36 ± 0.03 | 2.68 ± 0.17 | 0.01 ± 0.00 |

| CCONΔ | pUI2803 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 3.10 ± 0.05 |

| CCONΔ | pUI2803-H405A | 0.41 ± 0.01 | 2.71 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 |

| CCONΔ | pUI2803-H407A | 0.41 ± 0.01 | 2.38 ± 0.19 | 1.61 ± 0.02 |

| CCONΔ | pUI2803-H267A | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 2.65 ± 0.10 | 0.01 ± 0.00 |

aFor determination of spectral complex levels, strains carrying the corresponding plasmids were grown aerobically as in Table I. The levels of light harvesting complexes, B800–850 and B875, are expressed as nmol/mg protein.

bStrains were grown anaerobically in the dark with DMSO as a terminal electron acceptor. Cytochrome c oxidase activity was measured spectrophotometrically. cbb3 oxidase activity is expressed as µmol/min/mg protein. All values provided are the average of two independent determinations.

Cytochrome c oxidase activity was determined in the mutant strains as well as the control strains grown under anaerobic, dark–DMSO conditions where the cbb3 oxidase is the sole cytochrome c oxidase. As shown in Table II, the negative control strain CCONΔ (pRK415) showed no cbb3 oxidase activity. On the other hand, CCONΔ (pUI2803) exhibited a 2.6-fold increase in cbb3 oxidase activity as compared with the wild type 2.4.1 (pRK415), which can be explained by the copy number of the pRK415-based plasmid (four or five copies per cell). While virtually no cytochrome c oxidase activity was detected in the H405A and H267A mutants, the H407A mutant showed approximately half the cbb3 activity present in the control strain, CCONΔ (pUI2803), but which is still greater than that observed for 2.4.1 (pRK415).

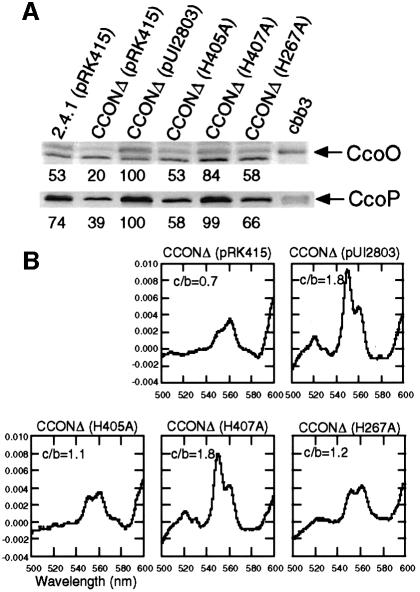

To determine whether the assembly of the cbb3 oxidase in the membrane was affected by the histidine replacements, we performed western blot analyses with antibodies against CcoO and CcoP of R.sphaeroides. As shown in Figure 5A, the H405A and H267A mutants contained 53–58% and 58–66% of the CcoO and CcoP subunits in their membranes, respectively, relative to the positive control strain, CCONΔ (pUI2803). Therefore, the replacement of the histidine residues involved in the coordination of the binuclear center of CcoN leads to either some assembly defect or instability in the cbb3 oxidase in the membrane. In contrast, near control levels of the CcoO and CcoP subunits were detected in the H407 mutant. The nature of the cross-reacting bands in the western analysis, which were not present in the purified cbb3 oxidase, is unknown.

Fig. 5. Immunological and spectroscopic analyses of the cbb3 oxidase from a set of histidine replacement mutants of CcoN. Membrane fractions were isolated from the strains harboring the corresponding plasmid (in parentheses) grown semi-aerobically by sparging with 2% O2–97% N2–1% CO2 to an OD600 of 0.5–0.6. (A) Western blot analysis using a polyclonal antibody against CcoO and CcoP proteins. Solubilized membrane proteins (50 µg) were loaded in each lane. H405A: pUI2803-H405A, H407A: pUI2803-H407A, H267A: pUI2803-H267A, cbb3: ∼2 µg of the purified cbb3 oxidase. The relative amounts of the CcoO and CcoP subunits are given below the western blots. (B) Dithionite-reduced minus air-oxidized difference spectra between 500 and 600 nm recorded at RT. Membrane proteins (0.2 mg/ml) solubilized with dodecyl maltoside were used for the assay. The 551 and 561 nm peaks represent c-type and b-type cytochromes, respectively. The ratio of heme c to heme b (c/b) was estimated by using their respective extinction coefficients (see Materials and methods).

Figure 5B shows the dithionite-reduced minus air-oxidized visible absorption spectra of membranes isolated from the three histidine replacement mutants as well as from the control strains. Because the stoichiometries of heme b and heme c in the cbb3 oxidase are not equal (two heme b and three heme c per enzyme molecule), an increase in cbb3 oxidase results in a higher ratio of heme c to heme b (c/b) in the visible spectrum profile. As expected, CCONΔ (pRK415) exhibited significantly reduced levels of both heme c and heme b as well as a decreased c/b. In the mutants H405A and H267A the levels of both heme b and c were significantly reduced as compared with the positive control strain CCONΔ (pUI2803). However, mutant H407A displayed only slightly (13–14%) decreased levels of b- and c-type hemes compared with CCONΔ (pUI2803). Futhermore, this mutant showed the same c/b as the positive control strain CCONΔ (pUI2803).

The results presented in Table II and Figure 5 reveal that with but one exception, all histidine to alanine substitutions result in the loss of cbb3 activity, a change in the c/b ratio and the derepression of PS gene expression. Only mutant H407A is relatively normal with respect to cbb3 structure and catalytic function, but still leads to the derepression of PS gene expression under aerobic conditions.

We further investigated the effects of mutations leading to replacements of the histidine residues in three heme-binding motifs (C-X-X-C-H-Xn-M-P) present in the CcoO and CcoP subunits. All three mutants showed the same phenotype as the H405A mutant, i.e. some defect in the assembly or stability of the cbb3 oxidase, the lack of cbb3 activity and oxygen-insensitive spectral complex formation under aerobic conditions (data not shown).

Redox state of the cyclic photosynthetic ETC serves as a signal that is in part mediated by PpsR

Collectively, these results strongly suggest that the cbb3 oxidase itself is the signal generator that controls the PrrBA two-component system and thereby controls both puc and puf operon expression. Yet, as observed above (Figure 2), puc operon expression is highly variable as compared with puf operon expression. One possible explanation is that another regulatory element, in addition to the cbb3–PrrBA signal transduction pathway, is operative in regulating puc expression. We do know that the AppA–PpsR antirepressor–repressor system and FnrL are active in regulating puc expression and it is possible that this(these) system(s) derive(s) a signal elsewhere in the ETC.

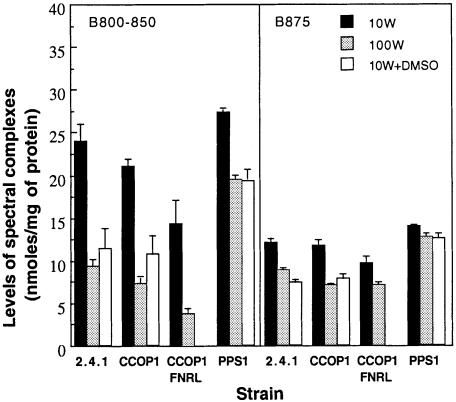

To address this question, we examined the effect of DMSO and light, which affect the redox state of the cyclic photosynthetic ETC, upon spectral complex formation in the CCOP1, PPS1 and CCOP1FNRL mutant strains as well as in the wild type as a control. The ability of the CCOP1FNRL mutant (Oh et al., 2000), in which both ccoP and fnrL genes are disrupted, to grow photosynthetically enabled us to examine the involvement of FnrL in the light response. As shown in Figure 6, when grown photosynthetically at high light (100 W/m2) or at medium light in the presence of DMSO (10 W/m2 + DMSO), the CCOP1 mutant and the wild-type strain produced very substantially reduced levels of the B800–850 and B875 complexes, when compared with the same strains grown at medium light (10 W/m2). In the case of the CCOP1FNRL mutant only the light effect was examined, since the synthesis of DMSO reductase is severely affected in this mutant. The CCOP1FNRL mutant showed a similar response to changes in light intensity to that of the wild-type and CCOP1 mutant strains with regard to the B800–850 and B875 complex levels. In contrast, the PPS1 mutant, in which the ppsR gene is disrupted, was much less responsive to either changes in light intensity or addition of DMSO to photosynthetic cultures.

Fig. 6. Effect of light intensity and DMSO on spectral complex formation in R.sphaeroides strains under photosynthetic conditions. Strains were grown photosynthetically at a light intensity of either 10 W/m2 (10W) or 100 W/m2 (100W). To examine the DMSO effect, strains were grown photosynthetically with supplementation of DMSO to a final concentration of 0.5% (v/v) at 10 W/m2 (10W+DMSO). Cells were harvested at an OD600 of 0.5–0.6 except for the CCOP1FNRL mutant grown at 100 W/m2 which was harvested at an OD600 of 0.2 because of its slow growth under these conditions. All values provided are the average of two independent determinations. Vertical bars represent the standard deviation from the mean.

Taken together, the data presented here imply that the redox state of the cyclic photosynthetic ETC, probably the quinone pool (see Discussion), is at least in part sensed by the AppA–PpsR system to control PS gene expression and that the cbb3–PrrBA pathway and FnrL appear not to be involved in sensing the redox state of the photosynthetic ETC in any major way.

Discussion

Previously it was reported from this laboratory that inactivation of the cbb3 oxidase leads to derepression of PS genes (PSD) under aerobic conditions, which is accompanied by the oxygen-insensitive formation of the spectral complexes (Zeilstra-Ryalls and Kaplan, 1996; O’Gara and Kaplan, 1997). Inactivation of the PrrBA two-component activation system in a Cco-minus background overrides the Cco-minus phenotype (O’Gara et al., 1998). The spectrum of PS genes that are derepressed under aerobic conditions by the inactivation of the cbb3 oxidase (puc, puf, hemA, bchE, hemN and hemZ) is coincident with those genes that are shown to be regulated by the PrrBA two-component system (Eraso and Kaplan, 1994; Zeilstra-Ryalls and Kaplan, 1996; O’Gara and Kaplan, 1997; Oh et al., 2000). Based on these and other findings, we proposed that the cbb3 cytochrome c oxidase functions as an O2/redox sensor, which transduces an inhibitory signal to the membrane-bound sensor histidine kinase, PrrB, under aerobic conditions to prevent PS gene expression. The unique role of the cbb3 oxidase in this sensory transduction pathway came from studies of a cbb3 lacking the CcoQ subunit. This mutant contains a fully functional cbb3 oxidase but it produces spectral complexes aerobically like other Cco mutant strains, further suggesting that the cbb3 oxidase itself is an O2/redox sensor (Oh and Kaplan, 1999). This assumption is strengthened by the finding that inactivation of the major cytochrome c oxidase aa3 revealed only a marginal effect upon PS gene expression under aerobic conditions. Thus, the available evidence directly implicates the cbb3 oxidase in regulating the PrrBA system and makes it highly unlikely that any other electron carriers of the ETC such as the bc1 complex and quinone pool are involved in this pathway.

The finding that strong PSD occurred in both the BC1 and C2Cy mutants grown under high oxygen conditions allowed us to speculate that it is the interruption of electron flow into the cbb3 oxidase that leads to aerobic PSD. Employing myxothiazol, it was clearly demonstrated that it is the extent of the electron flux through the cbb3 oxidase, rather than the binding per se of an oxygen molecule to the cbb3 oxidase that determines the degree of PSD. The greater the electron flow through the cbb3 oxidase, the stronger the inhibitory signal generated by the cbb3 oxidase which in turn represses the PrrBA two-component system, resulting in repression of PS gene expression.

As further proof that the signal transduction pathway originates within the structure of the cbb3 oxidase, we demonstrated that altering the structure of the cbb3 oxidase by changing a series of histidine residues involved in ligand coordination to alanine all led to the aerobic PSD. However, only in the case of H407A were both the catalytic function and structure of the cbb3 oxidase maintained. The H407A mutant contains near normal levels of apparently properly assembled cbb3 oxidase containing normal amounts of heme b, which is consistent with the data obtained from the coresponding mutant of Bradyrhizobium japonicum (Zufferey et al., 1998). The partial decrease in cbb3 activity in H407A despite the normal levels of heme b indicates that the loss of His407 might alter the conformation or placement of the low spin heme in CcoN. The absence of one axial ligand (His407) might result in displacement of the heme iron within the porphyrin plane toward the other axial ligand His118, which in turn causes a partial reduction of cbb3 oxidase activity. Considering that the H407A mutant contains more cbb3 oxidase activity than the wild type with pRK415, which contains a single copy of the ccoNOQP operon (see Table II), oxygen-insensitive formation of spectral complexes in this mutant implies that either the His407 itself or precise placement of the low spin heme might be required in order for the cbb3 oxidase to generate the inhibitory signal to repress PS gene expresion in the presence of O2. The removal of His407, as well as the non-polar deletion of the ccoQ gene, unambiguously dissociates the sensory function of the cbb3 oxidase from its catalytic function, reinforcing the idea that the CcoQ subunit of the cbb3 oxidase and the His407 residue or the low spin heme are intimately involved in signal generation and transduction. These results together with the lack of any phenotypic effect associated with the AA3 mutant indicate that no other component of the aerobic ETC is involved in the signal transduction pathway from cbb3 to the PrrBA two-component system.

The cbb3 oxidase has excellent properties as an oxygen sensor in order to provide for the orderly control of PS gene expression in R.sphaeroides: (i) it has a high affinity for O2 (Km of B. japonicum cbb3 oxidase is 7 nM which is 6- to 8-fold lower than that for the aa3 oxidase: Preisig et al., 1996) and (ii) it is present in cells grown under anaerobic conditions (Shapleigh et al., 1992; Oh and Kaplan, 1999). The high affinity of the cbb3 oxidase for O2 enables R.sphaeroides not to activate the PrrBA two-component system until O2 tensions in the environment fall to sufficiently low levels. The anaerobic presence of the cbb3 oxidase allows R.sphaeroides both to maintain transcriptional control of the PS genes under anaerobic conditions and to turn off the PrrBA system quickly as soon as it is exposed to O2.

How then does the inhibitory signal move from the cbb3 oxidase to the membrane-bound PrrB histidine kinase? We suggest that the CcoQ subunit, which is a part of the cbb3 complex, can monitor the ‘volume’ of electron flow through the cbb3 oxidase (Oh and Kaplan, 1999). Furthermore, recent genetic studies performed by Eraso and Kaplan proposed that the membrane-bound PrrC protein, whose gene is located immediately upstream of prrA, is located between the cbb3 oxidase and the PrrBA two-component system in the signal transduction pathway (Eraso and Kaplan, 2000).

Rhodobacter sphaeroides contains two functional cytochromes c under normal physiological conditions, which participate in electron transfer between the membrane-associated bc1 complex and the two terminal cytochrome c oxidases (Donohue et al., 1988; Myllykallio et al., 1999). The soluble periplasmic cytochrome c2 supports both respiratory and photosynthetic ETC, while the membrane-anchored cytochrome cy participates only in respiratory electron transfer. Based upon our assumption that the ‘extent’ of electron flow through the cbb3 oxidase ultimately determines the level of PS gene expression under aerobic conditions, then the differential expression of both the puc and puf operons observed in the C2 and Cy mutants grown under 30% O2 conditions permits us to assign, albeit indirectly, the relative contribution of cytochromes c2 and cy to channel electrons from the bc1 complex to the cbb3 oxidase (see Figure 2). From these results, we suggest that under 30% O2 conditions the membrane-bound cytochrome cy is approximately two to three times more effective in its ability to channel electrons from the bc1 complex to the cbb3 oxidase than is cytochrome c2.

The puf operon, which appears to be under the exclusive control of the PrrBA system (Zeilstra-Ryalls et al., 1998), was shown to be derepressed to similar levels in the BC1, C2Cy, CCONΔ and CCOQΔ mutant strains (see Figure 2B). However, in the case of the puc operon its degree of derepression in the aforementioned mutants was highly variable, i.e. derepression of the puc operon in the BC1 and C2Cy mutants was substantially higher than that observed for the CCONΔ and CCOQΔ mutant strains (see Figure 2A). These differences in puc and puf operon expression imply that ‘factors’, in addition to the PrrBA activation system, are operative together with the PrrBA system in regulating the puc operon. These factors, in a cbb3–PrrBA-independent manner, sense another redox signal associated with the interruption of electron flow through the bc1 complex to enhance puc operon expression. Other factors known to affect puc operon expression are FnrL, IHF and the AppA–PpsR antirepressor–repressor system (Zeilstra-Ryalls et al., 1998). We postulate that the redox state of the quinone pool, which is positioned upstream of the bc1 complex in the ETC, might be the source of another signal that is transduced to enhance puc operon expression independently of the cbb3–PrrBA signal transduction pathway. The redox state of the quinone pool can be affected by the rate at which electrons are removed to the terminal oxidases under aerobic conditions or to the terminal reductases such as DMSO reductase under anaerobic conditions, when a steady flow of electrons from a given organic electron donor is entering the pool. In addition, changes in the light intensity also affect the redox state of the quinone pool. Therefore, under 30% O2, inactivation of the bc1 complex or both cytochromes c2 and cy is likely to shift the quinone pool toward a more reduced state, which might preferentially enhance the derepression of the puc operon relative to the puf operon.

What then might sense the redox state of the quinone pool? The best candidate to our knowledge is the AppA antirepressor–PpsR repressor system (Gomelsky and Kaplan, 1995a,b, 1997). The reasons are that: (i) it is involved in the regulation of the puc operon and not the puf operon (Gomelsky and Kaplan, 1995a); (ii) the PpsR mutant PPS1 was shown to be much less responsive to the transition from medium light (10 W/m2) to high light (100 W/m2) as well as to the addition of DMSO to photosynthetic cultures when compared with the wild type with regard to spectral complex formation; (iii) the CCOP1 and CCOP1FNRL mutant strains showed a similar response to changes in light intensity under photosynthetic conditions to the wild type, eliminating the involvement of both the cbb3–PrrBA signal transduction pathway and FnrL in sensing and transduction of the redox state of the quinone pool; (iv) the AppA protein contains at least FAD as a possible redox prosthetic group (Gomelsky and Kaplan, 1998), which further raises the possibility that it might sense the redox state of the quinone pool; and finally (v) there is no indication that the IHF protein is involved in redox control, although it has been shown to be involved in puc operon regulation (Lee et al., 1993).

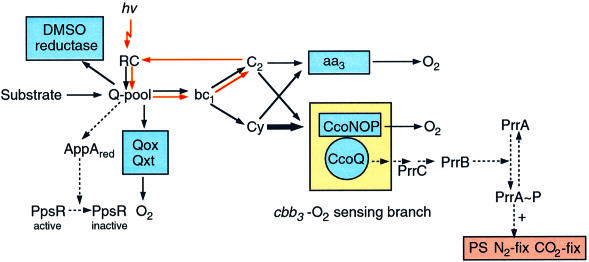

On the basis of the results presented here, as well as those reported previously (Zeilstra-Ryalls et al., 1998; Oh and Kaplan, 1999; Oh et al., 2000), we present a model describing the interrelationship between the regulation of the PS genes and the activity of the ETC in R.sphaeroides (Figure 7). This model together with other recent studies of the anaerobic regulator FnrL, which participates in the selective control of both puc and the tetrapyrrole biosynthesis genes such as hemA, hemN, hemZ and bchE as well as the ccoNOQP operon as conditions become increasingly less aerobic (Zeilstra-Ryalls and Kaplan, 1995, 1998; Zeilstra-Ryalls et al., 1997; Mouncey and Kaplan, 1998a; Oh et al., 2000), allows us to describe fully the regulation of PS gene expression in R.sphaeroides.

Fig. 7. Respiratory and photosynthetic electron transport pathways in R.sphaeroides and model for redox sensing and signal transduction. The solid and dotted arrows demonstrate the electron and signal flows, respectively. The red arrows indicate the photosynthetic cyclic electron transport pathway. The thickness of the arrow indicates the presumptive relative contribution of cytochromes c2 and cy to channel electrons from the bc1 complex to the cbb3 oxidase. The ‘+’ sign indicates the activation of genes. Abbreviations: Q-pool, ubiquinone pool; bc1, cytochrome bc1 complex; C2, soluble cytochrome c2; Cy, membrane-bound cytochrome cy; aa3, aa3-type cytochrome c oxidase; RC, photochemical reaction center; Qox and Qxt, two quinol oxidases; PS, photosynthesis; fix, fixation; hv, light; red, reduced form.

In summary, we here demonstrated that the regulation of PS gene expression in R.sphaeroides is closely coupled with the activity of the ETC, i.e. the functional state of the cbb3 oxidase and the redox state of the quinone pool. The fact that the cbb3 oxidase has dual function as both a terminal oxidase and an O2 sensor and that it, together with the PrrBA two-component system, constitutes a signal transduction pathway, provides a new paradigm for O2 sensing and gene regulation. The advantage of redox sensing through the ETC, as demonstrated here, appears to be the ability to respond rapidly and precisely to environmental stimuli as well as to provide for a mechanism to integrate all cellular metabolic activities.

Materials and methods

Strains, plasmids and growth conditions

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table III. Rhodobacter sphaeroides and Escherichia coli strains were grown as described previously (Oh and Kaplan, 1999).

Table III. Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work.

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant phenotype or genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| R.sphaeroides | ||

| 2.4.1 | wild type | van Neil (1944) |

| BC1 | 2.4.1 derivative, ΔfbcBC::Tp cassette | N.J.Mouncey, E.Gak, M.Choudhary, J.Oh and S.Kaplan, in preparation |

| C2 | 2.4.1 derivative, formerly CYCA1, ΔcycA::Km cassette | Donohue et al. (1988) |

| Cy | 2.4.1 derivative, cycY::Tp cassette | this study |

| C2Cy | 2.4.1 derivative, ΔcycA::Km cassette cycY::Tp cassette | this study |

| CCONΔ | 2.4.1 derivative, in-frame deletion in ccoN | Oh and Kaplan (1999) |

| AA3 | 2.4.1 derivative, ΔctaD::Sp/St cassette | this study |

| CCOP1 | 2.4.1 derivative, ccoP::Tp cassette | O’Gara and Kaplan (1997) |

| CCOP1FNRL | 2.4.1 derivative, ccoP::Tp cassette, ΔfnrL::Km cassette | Oh et al. (2000) |

| PPS1 | 2.4.1 derivative, ppsR::Km cassette | Gomelsky and Kaplan (1997) |

| CCOQΔ | 2.4.1 derivative, in-frame deletion in ccoQ | Oh and Kaplan (1999) |

| E.coli | ||

| S17-1 | Pro– Res– Mod+ recA; integrated plasmid RP4-Tc::Mu-Km::Tn7 | Simon et al. (1983) |

| Plasmids | ||

| pNHG1 | Kmr Tcr; SacB RP4-oriT ColE1-oriT | Jeffke et al. (1999) |

| pRK415 | Tcr; Mob+ lacZα IncP | Keen et al. (1988) |

| pUI624 | Apr; pBS::0.53 kb XmaIII fragment of puc | Lee et al. (1989) |

| pUI655 | Apr; pBS::0.47 kb StyI fragment of pufBA | J.K.Lee |

| pUI2803 | pRK415::4.7 kb BamHI–EcoRI fragment containing ccoNOQP | O’Gara and Kaplan (1997) |

| pUI2803-H405A | pUI2803 in which His405 of CcoN is changed to Ala | this study |

| pUI2803-H407A | pUI2803 in which His407 of CcoN is changed to Ala | this study |

| pUI2803-H267A | pUI2803 in which His267 of CcoN is changed to Ala | this study |

| pUI8180 | Tcr; pLA2917 derivative, cosmid containing cycY, ccoNOQP and rdxBHIS | Zeilstra-Ryalls and Kaplan (1995) |

| pTP | Apr Tpr; pBSIISK+::1110 bp ApaI fragment containing the Tp cassette | this study |

| pCTS1 | pJS1 derivative, ΔctaD::Sp/St | Shapleigh and Gennis (1992) |

| pCYΔ3 | Kmr Tcr Tpr; pNHG1 derivative, cycY::Tp | this study |

| pCCO2 | pUC19::4.7 kb BamHI–EcoRI fragment from pUI2803 | this study |

| p19CCON | pUC19::2.6 kb BamHI–SacI fragment from pCCO2 | this study |

| pCF200Km | Spr Str Kmr; IncQ, puc::lacZYA′ | Lee and Kaplan (1992) |

| pUI1663 | Spr Str Kmr; IncQ, puf::lacZYA′ | Eraso and Kaplan (1996) |

DNA manipulations and conjugation techniques

Genomic DNA from R.sphaeroides was isolated according to Ausubel et al. (1988). Standard protocols (Sambrook et al., 1989) or manufacturer’s instructions were followed for recombinant DNA manipulations. Mobilization of plasmids from E.coli strains into R.sphaeroides strains was performed as described elsewhere (Davis et al., 1988).

Construction of mutants

Cy and C2Cy mutants. In order to construct the Cy mutant, a 1232 bp fragment containing the cycY gene was amplified from pUI8180 by PCR using pfu turbo polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) using primers CyEcoRI (5′-GCAAAAGAATTCTCGACCGGCAGCATC-3′) and CyHindIII (5′-CTCGCCAAGCTTGGGTGCGTCGGGATTG-3′). The PCR product was restricted with EcoRI and HindIII, and cloned into pUC19 to give plasmid pCYΔ1. A 1.1 kb ApaI fragment containing the Tp cassette from pTP was cloned into pCYΔ1 digested with ApaI, resulting in the plasmid pCYΔ2. Finally, a 2.3 kb EcoRI–HindIII fragment from pCYΔ2 was filled in by treatment of Klenow fragment of E.coli polymerase I and subsequently cloned into the suicide vector pNHG1, which was restricted with SacI and blunt-ended, yielding the plasmid pCYΔ3. The resulting plasmid pCYΔ3 was transferred from E.coli strain S17-1 to R.sphaeroides 2.4.1 and C2 by conjugation to generate Cy and C2Cy mutants, respectively. Heterogenotes of R.sphaeroides, generated by a single recombination event, were selected for their Km and Tc resistance on SIS agar plates incubated under aerobic conditions. Isogenic homogenotes were obtained from the heterogenotes after a second recombination selecting for sucrose and Tp resistance on SIS agar plates containing 15% (w/v) sucrose, 1% (w/v) Bactotrypton, 0.5% (w/v) yeast extract, 0.5% (w/v) NaCl and 0.5% (v/v) DMSO under dark anaerobic conditions.

AA3 mutant. The AA3 mutant was constructed by crossing pCTS1 into R.sphaeroides 2.4.1 and selecting for the double cross-over recombinant.

Site-directed mutagenesis

To mutate His267, His405 and His407 of CcoN to alanine, a 2.6 kb BamHI–SacI fragment carrying the ccoN gene was cloned from pCCO2 into pUC19. The resulting plasmid, p19CCON, was used as a template plasmid for site-directed mutagenesis. Mutagenesis was carried out using the Quick Change Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). Synthetic oligonucleotides 33–34 bases long containing an alanine codon (GCC) in place of the histidine codon in the middle of their sequences were used to mutagenize the histidine codons. Following the verification of mutations by sequencing, a 2.6 kb BamHI–SacI fragment containing the mutated sequence was cloned back into pCCO2, in which the 2.6 kb fragment was removed, to give pCCO2 with the mutated sequence. The entire insert of the mutated pCCO2 (the 4.7 kb BamHI–EcoRI fragment containing the entire ccoNOQP operon) was cloned in pRK415. The resulting plasmids, pUI2803-H267A, pUI2803-H405A and pUI2803-H407A, were introduced into R.sphaeroides CCONΔ, a strain in which a part of ccoN has been deleted in frame by gene replacement.

RNA isolation and analysis

Total RNA was isolated from R.sphaeroides strains as described by Oelmüller et al. (1990). Northern hybridization experiments were performed using the AlkPhos DIRECT System (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) as instructed by the manufacturer. Quantitation of signals was performed with NIH Imager 1.62. The signal levels were normalized by those of processed 23S and 16S rRNA.

Preparation of solubilized membrane proteins

The harvested cells were resuspended in buffer A (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5) and disrupted by passage through a French pressure cell. Cell-free crude extracts were obtained following centrifugation at 27 000 g for 20 min at 4°C to remove unbroken cells and cell debris. Membrane fractions were isolated by ultracentrifugation of crude extracts at 150 000 g for 1 h at 4°C. After membrane fractions (pellet) were washed twice with buffer A, the membranes were solubilized in buffer A containing 0.5% (w/v) sodium dodecyl maltoside by pipetting and then centrifuged at 13 000 r.p.m. for 10 min in a benchtop minicentrifuge. The supernatant was taken as solubilized membrane proteins.

Spectroscopic and immunoblotting analyses

Solubilized membrane proteins (0.2 mg/ml) in buffer A containing 0.5% (w/v) sodium dodecyl maltoside was used to record an air-oxidized spectrum on an UV 1601PC spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Corp., Columbia, MD). The same sample was reduced with 30 µl of 15% (w/v) sodium dithionite for 2 min at room temparature (RT) and then a reduced spectrum was recorded. The dithionite-reduced minus air-oxidized spectrum was obtained by subtraction of these two spectra. The amount of the b- and c-type hemes was estimated by using the extinction coefficients ε561–575 of 22 mM–1 cm–1 and ε551–540 of 19 mM–1 cm–1, respectively.

The B800–850 and B875 complex levels were determined spectrophotometrically as described previously (Oh and Kaplan, 1999). SDS–PAGE and western blotting were performed as described elsewhere (Laemmli, 1970; Mouncey and Kaplan, 1998b).

Enzyme assays and protein determination

Preparation of crude cell extracts and determination of β-galactosidase activities were performed as described previously (Oh and Kaplan, 1999). Cytochrome c oxidase activities were measured either spectrophotometrically with reduced horse heart cytochrome c (Sigma, St Louis, MO) as described previously (Oh and Kaplan, 1999) or polarographically with a Clark-type oxygen electrode (YSI Inc., Yellow Springs, OH). Prepared membrane fractions washed twice with 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.0 were resuspended in the same buffer. The rate of oxygen uptake at 30°C was determined with 0.2 mg resuspended membrane fractions in 5 ml 30% O2 saturated buffer after addition of 20 µM horse heart cytochrome c and 12.5 mM ascorbate. Protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL) using bovine serum albumin as the standard protein.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr F.Daldal for his comments on Cy. This work was supported by grant GM15590 to S.K.

References

- Ausubel F.M., Brent,R., Kingston,R.E., Moore,D.D., Seidman,J.G., Smith,J.A. and Struhl,K. (1988) Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Greene Publishing Associates and John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Bazire G., Sistrom,W.R. and Stanier,R.Y. (1956) Kinetic studies of pigment synthesis by non-sulfur purple bacteria. J. Cell. Comp. Physiol., 49, 25–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J., Donohue,T.J. and Kaplan,S. (1988) Construction, characterization, and complementation of a Puf– mutant of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol., 170, 320–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue T.J., McEwan,A.G., Van Doren,S., Crofts,A.R. and Kaplan,S. (1988) Phenotypic and genetic characterization of cytochrome c2 deficient mutants of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochemistry, 27, 1918–1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eraso J.M. and Kaplan,S. (1994) prrA, a putative response regulator involved in oxygen regulation of photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol., 176, 32–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eraso J.M. and Kaplan,S. (1996) Complex regulatory activities associated with the histidine kinase PrrB in expression of photosynthesis genes in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J. Bacteriol., 178, 7037–7046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eraso J.M. and Kaplan,S. (2000) From redox flow to gene regulation: role of the PrrC protein of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. Biochemistry, 39, 2052–2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Horsman J.A., Barquera,B., Rumbley,J., Ma,J. and Gennis,R.B. (1994a) The superfamily of heme–copper respiratory oxidases. J. Bacteriol., 176, 5587–5600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Horsman J.A., Berry,E., Shapleigh,J.P., Alben,J.O. and Gennis,R.B. (1994b) A novel cytochrome c oxidase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides that lacks CuA. Biochemistry, 33, 3113–3119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomelsky M. and Kaplan,S. (1995a) Genetic evidence that PpsR from Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1 functions as a repressor of puc and bchF expression. J. Bacteriol., 177, 1634–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomelsky M. and Kaplan,S. (1995b) appA, a novel gene encoding a trans-acting factor involved in the regulation of photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J. Bacteriol., 177, 4609–4618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomelsky M. and Kaplan,S. (1997) Molecular genetic analysis suggesting interactions between AppA and PpsR in regulation of photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J. Bacteriol., 179, 128–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomelsky M. and Kaplan,S. (1998) AppA, a redox regulator of photosystem formation in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1, is a flavoprotein. Identification of a novel FAD binding domain. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 35319–35325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosler J.P., Fetter,J., Tecklenburg,M.M., Espe,M., Lerma,C. and Ferguson-Miller,S. (1992) Cytochrome aa3 of Rhodobacter sphaeroides as a model for mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase. Purification, kinetics, proton pumping, and spectral analysis. J. Biol. Chem., 267, 24264–24272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata S., Ostermeier,C., Ludwig,B. and Michel,H. (1995) Structure at 2.8 Å resolution of cytochrome c oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans. Nature, 376, 660–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffke T., Gropp,N.H., Kaiser,C., Grzeszik,C., Kusian,B. and Bowien,B. (1999) Mutational analysis of the cbb operon (CO2 assimilation) promoter of Ralstonia eutropha. J. Bacteriol., 181, 4374–4380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi H.M. and Tabita,F.R. (1996) A global two component signal transduction system that integrates the control of photosynthesis, carbon dioxide assimilation, and nitrogen fixation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 14515–14520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen N.T., Tamaki,S., Kobayashi,D. and Trollinger,D. (1988) Improved broad-host-range plasmids for DNA cloning in gram-negative bacteria. Gene, 70, 191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiley P.J. and Kaplan,S. (1988) Molecular genetics of photosynthetic membrane biosynthesis in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Microbiol. Rev., 52, 50–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U.K. (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature, 227, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.K. and Kaplan,S. (1992) cis-acting regulatory elements involved in oxygen and light control of puc operon transcription in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol., 174, 1146–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.K., Kiley,P.J. and Kaplan,S. (1989) Posttranscriptional control of puc operon expression of B800–850 light-harvesting complex formation in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol., 171, 3391–3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.K., Wang,S., Eraso,J.M., Gardner,J. and Kaplan,S. (1993) Transcriptional regulation of puc operon expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Involvement of an integration host factor-binding sequence. J. Biol. Chem., 268, 24491–24497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouncey N.J. and Kaplan,S. (1998a) Oxygen regulation of the ccoN gene encoding a component of the cbb3 oxidase in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1T: involvement of the FnrL protein. J. Bacteriol., 180, 2228–2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouncey N.J. and Kaplan,S. (1998b) Redox-dependent gene regulation in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1(T): effects on dimethyl sulfoxide reductase (dor) gene expression. J. Bacteriol., 180, 5612–5618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myllykallio H., Zannoni,D. and Daldal,F. (1999) The membrane-attached electron carrier cytochrome cy from Rhodobacter sphaeroides is functional in respiratory but not in photosynthetic electron transfer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 4348–4353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelmüller U., Kruger,N., Steinbuchel,A. and Friedrich,C.G. (1990) Isolation of procaryotic RNA and detection of specific mRNA with biotinylated probes. J. Microbiol. Methods, 11, 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- O’Gara J.P. and Kaplan,S. (1997) Evidence for the role of redox carriers in photosynthesis gene expression and carotenoid biosynthesis in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J. Bacteriol., 179, 1951–1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Gara J.P., Eraso,J.M. and Kaplan,S. (1998) A redox-responsive pathway for aerobic regulation of photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J. Bacteriol., 180, 4044–4050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J.I. and Kaplan,S. (1999) The cbb3 terminal oxidase of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1: structural and functional implications for the regulation of spectral complex formation. Biochemistry, 38, 2688–2696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J.I., Eraso,J.M. and Kaplan,S. (2000) Interacting regulatory circuits involved in the orderly control of photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J. Bacteriol., 182, 3081–3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preisig O., Zufferey,R., Thony-Meyer,L., Appleby,C.A. and Hennecke,H. (1996) A high-affinity cbb3-type cytochrome oxidase terminates the symbiosis-specific respiratory chain of Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J. Bacteriol., 178, 1532–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Y. and Tabita,F.R. (1996) A global signal transduction system regulates aerobic and anaerobic CO2 fixation in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol., 178, 12–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd Edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Shapleigh J.P. and Gennis,R.B. (1992) Cloning, sequencing and deletion from the chromosome of the gene encoding subunit I of the aa3-type cytochrome c oxidase of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Mol. Microbiol., 6, 635–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapleigh J.P., Hill,J.J., Alben,J.O. and Gennis,R.B. (1992) Spectroscopic and genetic evidence for two heme–Cu-containing oxidases in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol., 174, 2338–2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon R., Priefer,U. and Puhler,A. (1983) A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. BioTechnology, 1, 784–791. [Google Scholar]

- Toledo-Cuevas M., Barquera,B., Gennis,R.B., Wikstrom,M. and Garcia-Horsman,J.A. (1998) The cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides, a proton-pumping heme–copper oxidase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1365, 421–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Neil C.B. (1944) The culture, general physiology, morphology, and classification of the non-sulfur purple and brown bacteria. Bacteriol. Rev., 8, 1–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeilstra-Ryalls J.H. and Kaplan,S. (1995) Aerobic and anaerobic regulation in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1: the role of the fnrL gene. J. Bacteriol., 177, 6422–6431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeilstra-Ryalls J.H. and Kaplan,S. (1996) Control of hemA expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1: regulation through alterations in the cellular redox state. J. Bacteriol., 178, 985–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeilstra-Ryalls J.H. and Kaplan,S. (1998) Role of the fnrL gene in photosystem gene expression and photosynthetic growth of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J. Bacteriol., 180, 1496–1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeilstra-Ryalls J.H., Gabbert,K., Mouncey,N.J., Kaplan,S. and Kranz,R.G. (1997) Analysis of the fnrL gene and its function in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Bacteriol., 179, 7264–7273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeilstra-Ryalls J., Gomelsky,M., Eraso,J.M., Yeliseev,A., O’Gara,J. and Kaplan,S. (1998) Control of photosystem formation in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol., 180, 2801–2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zufferey R., Arslan,E., Thony-Meyer,L. and Hennecke,H. (1998) How replacements of the 12 conserved histidines of subunit I affect assembly, cofactor binding, and enzymatic activity of the Bradyrhizobium japonicum cbb3-type oxidase. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 6452–6459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]