Masses due to cystic lesions of the breast are extremely common findings on mammography, ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging. Although many of these lesions can be dismissed as benign simple cysts, requiring intervention only for symptomatic relief, complex cystic and solid masses require biopsy. Perhaps the most challenging are complicated cysts, that is, cysts with internal debris. When the debris is mobile or a fluid-debris level is seen, complicated cysts can be dismissed as benign. Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS)1 2, findings. When the debris is homogeneous and hypoechoic, it is often difficult to distinguish a complicated cyst from a solid mass. As an isolated finding, homogeneous complicated cysts can be classified as probably benign, BI-RADS 3, with intervention only considered if there is interval development or enlargement, if abscess is suspected, or if suspicious features develop. When multiple and bilateral complicated and simple cysts are present (ie, at least 3 cysts, with at least 1 in each breast), a benign, BI-RADS 2, assessment is usually appropriate. Clustered microcysts are common benign findings in pre- and perimenopausal women, although short-interval surveillance may be appropriate for many such lesions in postmenopausal women, particularly if the lesion is new or rather small or deep (ie, diagnostic uncertainty). Intradermal cysts, such as epidermal inclusion cysts and sebaceous cysts, are benign findings, which are not included in this review.

Increasing use of whole breast screening ultrasonography reveals many, otherwise occult, cystic lesions of the breast; a thorough understanding of their imaging findings and management is important. In addition to reviewing the literature on such lesions, the authors present results from the American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ACRIN) 6666 protocol of screening breast ultrasonography.2 In the ACRIN protocol, women at high risk for breast cancer were screened annually with mammography and independent, physician-performed, freehand sonography for 3 years.3 The reference standard for a given lesion in the ACRIN protocol includes not only biopsy within the first year of follow-up or at least 11-month follow-up imaging but also any biopsy results for procedures performed through a minimum of 33 months of follow-up. A summary of studies reviewed after systematic literature search (PubMed, National Library of Medicine, on January 2, 2010) and associated reference standards are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of studies evaluating cystic breast lesions

| Study, Year | Description of Population | Reference Standard |

|---|---|---|

| Omori et al,46 1993 | 6000 consecutive sonograms, 70 cases of mixed cystic and solid lesions |

Surgical excision of 56 reported cases |

| Kolb et al,23 1998 | 3626 screening sonograms in women with at least minimal scattered fibroglandular density; normal mammography and clinical breast examination |

Aspiration (n = 30) or follow-up (n = 126) for lesions described |

| Venta et al,24 1999 | 4562 consecutive diagnostic sonograms, 252 women with 308 complexa cysts |

141 lesions were attempted for aspiration, but 24 failed and had biopsy; 2 bloody, atypical cytology, biopsy benign |

| Buchberger et al,20 2003 | 6113 asymptomatic women with at least minimal scattered fibroglandular density, and 687 women with palpable or mammographic masses; 133 complexa cysts identified |

All 133 lesions aspirated; 7 could not be aspirated and had core biopsy |

| Berg et al,19 2003 | 2072 image-guided biopsies, 150 cystic lesions identified |

All lesions biopsied; follow-up after biopsy in 126 |

| Berg,35 2005 | 1900 consecutive sonograms with 79 clustered microcysts; 4 palpable |

13 biopsied lesions overlap with prior series,19 66 lesions followed |

| Chang et al,21 2007 | 212 patients with symptomatic cystic lesions among 57,437 sonograms |

175 lesions with pathologic proof reported |

| Daly et al,22 2008 | 186 patients consecutively presenting for aspiration of 243 complicated cysts, including 15 clustered microcysts (ie, 228 were complicated cysts) |

Pathologic proof for all lesions: 243 lesions aspirated, 33 did not yield fluid; 32 biopsied and 1 resolved; benign lesions followed for a mean of 21.9 mo |

| Tea et al,47 2009 | Retrospective review of records reporting complex cyst; 151 lesions in 131 patients. Nonstandard terminology used: impossible to compare with prior literature for most subgroups |

Excision of all lesions |

| ACRIN 6666 | 2809 women at elevated risk of breast cancer enrolled for 3 rounds of annual screening ultrasonography, blinded to mammography |

11-month follow-up or biopsy available for 2659 women year 1; 2493 women, year 2; 2321 women, year 3; total 2662 unique participants |

The term complex is used, but the description is that of complicated cysts: mass resembles a cyst except that internal echoes are present or posterior enhancement is absent; mass has circumscribed margins with no perceptible intracystic mass or solid component.

Meticulous technique is critical in evaluating cystic lesions, and technical issues with breast ultrasonography are discussed in this article. Use of high-frequency, broadband, linear array transducers, with center frequency of at least 10 MHz, is required for adequate breast ultrasonography.

SIMPLE CYSTS

Simple cysts are epithelium-lined, fluid-filled, round or oval structures that are thought to occur secondary to obstructed ducts. The epithelium can be bland or apocrine type. The latter is a tall, cuboidal, secretory epithelium and can make the inner wall of the cyst appear fuzzy on high-resolution ultrasonography. Cysts can be isolated or diffuse and can occur in any quadrant. Ectopic breast tissue (tail of Spence) can extend into the axillary tail regions, but breast tissue and therefore cysts and other breast lesions are not usually found within the axillae proper.

Cysts are the most common type of breast mass, with peak incidence between ages 35 and 50 years. Simple cysts represented 25% of consecutive breast masses in the series by Hilton and colleagues.4 In the ACRIN 6666 protocol, cysts were seen in 998 (37.5%) of 2659 women in the first round of screening ultrasonography and in 1255 (47.1%) of 2662 participants over the 3 years. Of the participants with simple cysts, nearly half (48%) had cysts in both breasts. Being hormonally sensitive, cysts can fluctuate in size and number with the menstrual cycle, being most prominent in the premenstrual phase. In postmenopausal women, cysts are more common in women on hormone replacement therapy5,6 and were reported in 6% of such women in 1 series.6 Based on the ACRIN 6666 experience, it seems that postmenopausal cysts are much more common. In the first year of ACRIN 6666 trial, 406 (29.8%) of 1362 postmenopausal women were found to have cysts, decreasing to 298 (24.7%) of 1208 by year 3. Cysts were seen at some time during the 3-year study in 537 (39.4%) of 1363 postmenopausal women compared with 516 (65.1%) of 793 premenopausal women (P<.0001) (Table 2). Among 1363 postmenopausal women in the ACRIN 6666 trial, 73 (5.4%) were using estrogen replacement therapy. Over the 3-year study, cysts were seen in 48 (66%) of 73 women using estrogen compared with 489 (37.9%) of 1290 who were not (P<.0001) (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of simple cysts among 2662 unique participants in ACRIN 6666

| Number of Participants | Number with Cysts (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Premenopausal | 793 | 516 (65.1) |

| Postmenopausal | 1363 | 537 (39.4) |

| No HRTa | 1290 | 489 (37.9) |

| HRT | 73 | 48 (66)b |

| Surgical Menopause | 484 | 193 (39.9) |

| Unknown Menopausal status | 22 | 9 (41) |

| Total | 2662 | 1255 (47.1) |

HRT, any estrogen-containing hormone replacement therapy.

Simple cysts were more common in postmenopausal women taking HRT rather than not taking HRT (P<.0001).

The natural history of cysts is to develop and regress. In a series following 68 newly appearing benign cysts, Brenner and colleagues7 reported that 47% had completely regressed within 1 year and 69% within 5 years. In any given year, up to 12% of the cysts had increased in size.7

Imaging Findings

Mammographically, cysts present as solitary or multiple, often bilateral, low-density, circumscribed, round, oval, or occasionally mildly lobulated masses (Figs. 1–4), which vary in size from several millimeters to 5 to 6 cm. The margins are frequently obscured by surrounding parenchyma. When at least 75% of the margin of the mass is seen as circumscribed and the rest is not worse than obscured, the mass is still considered circumscribed.8 Cysts can have thin calcified walls and can contain calcium. Calcium in cysts, ie, milk of calcium, appears amorphous, round, or smudgy on the craniocaudal (CC) view and changes in appearance to layer on a true lateral (mediolateral or lateromedial) view like leaves in the bottom of a tea cup (Fig. 5). With the exception of macrocysts containing milk of calcium, cysts cannot be distinguished from solid masses mammographically.

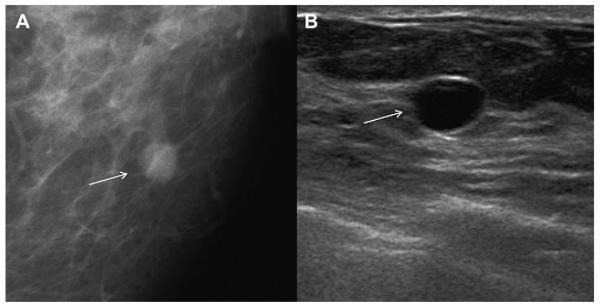

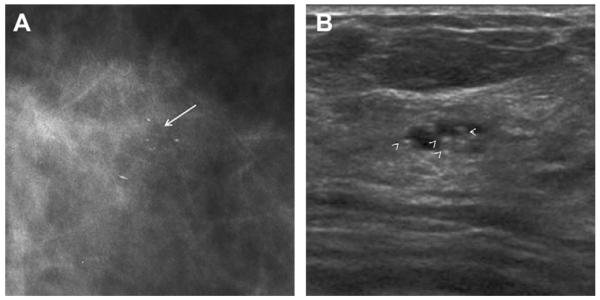

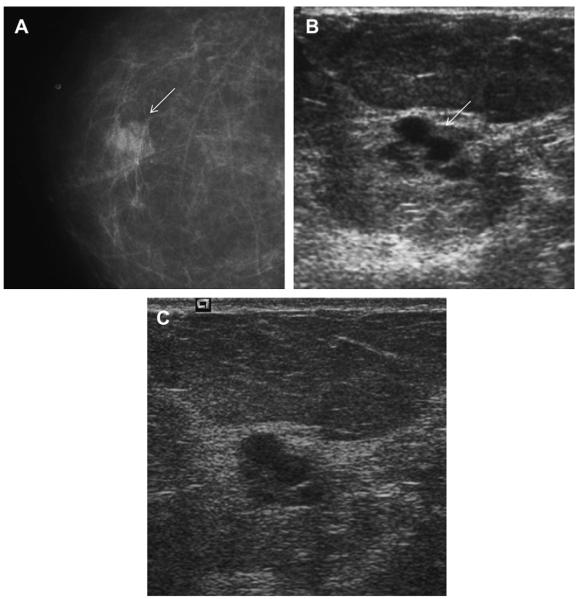

Fig. 1.

A 74-year-old woman was noted to have a new mass on screening mammography and no history of hormone use. (A) Spot magnification craniocaudal (CC) view shows partially circumscribed, partially obscured 7-mm mass (arrow). (B) Targeted ultrasonography shows anechoic circumscribed mass (arrow) with minimal posterior enhancement, that is, a simple cyst, corresponding to the mammographic abnormality, a benign finding. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

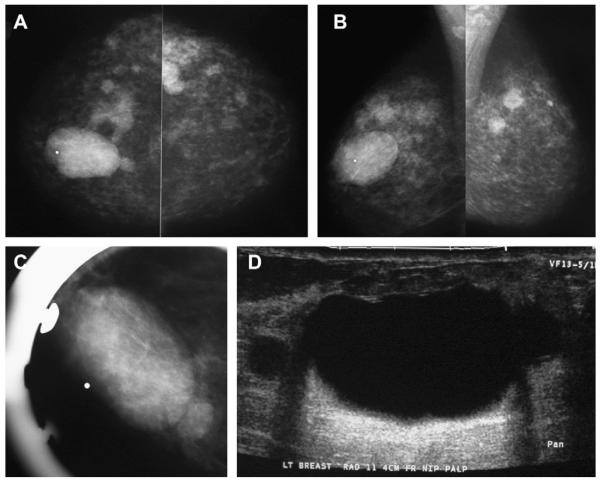

Fig. 4.

A 43-year-old woman had a history of cysts and presented with a lump in the left breast. (A) Bilateral CC and (B) MLO mammograms show minimal scattered fibroglandular density and multiple bilateral PCPO masses consistent with the history of cysts. Ultrasonography is appropriate at least to evaluate the dominant, palpable mass (marked with a radiopaque marker). (C) Spot compression view was performed, but, in this case, it is not necessary before (D) targeted ultrasonography, which confirmed a benign simple cyst. Aspiration is typically only performed for symptomatic relief or diagnostic uncertainty. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

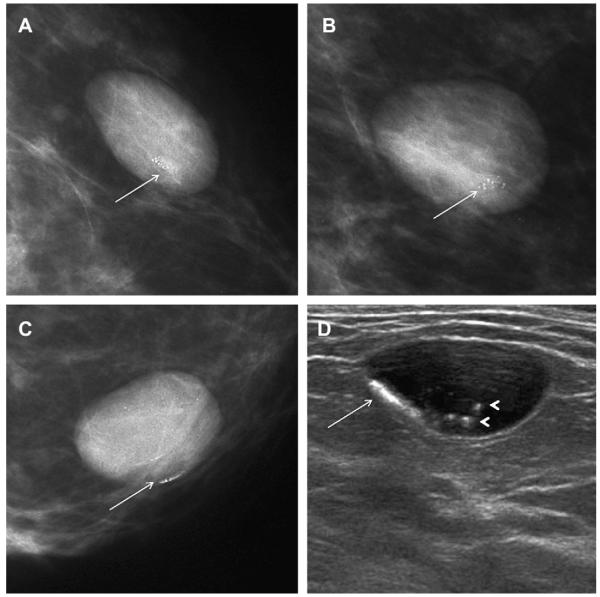

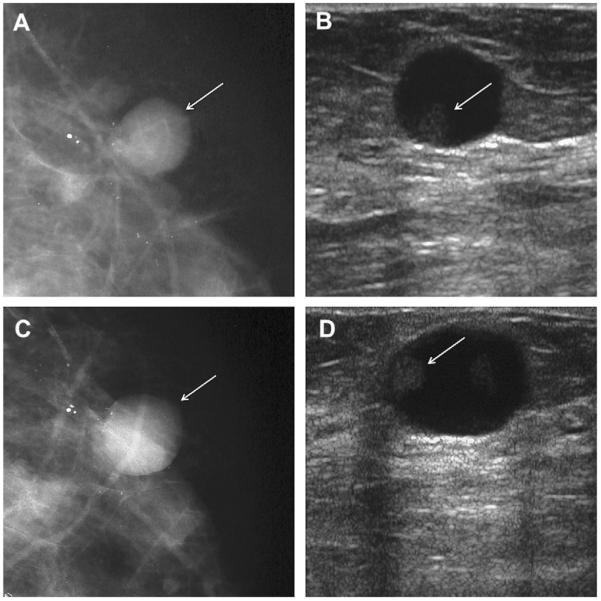

Fig. 5.

On screening mammography, a 65-year-old woman was noted to have a circumscribed oval mass containing calcifications that were punctate and amorphous and changed appearance between (A) CC and (B) MLO views (arrows). (C) True lateral view was obtained, showing the calcifications to layer in the inferior aspect of the mass (arrow), compatible with milk of calcium within a cyst. Layering calcifications were also evident on (D) ultrasonography (arrow), although not all the echogenic calcifications layer (arrowheads). (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

When multiple and bilateral (with at least 3 cysts in total and at least 1 in each breast), partially circumscribed, partially obscured (PCPO) masses can be dismissed as benign findings, BI-RADS 2,9 with the usual etiologies being cysts (see Figs. 3 and 4), complicated cysts, and fibroadenomata. With multiple bilateral PCPO masses, ultrasonography is appropriate when there is a dominant or palpable mass (see Fig. 4; Figs. 6 and 7) or if 1 or more masses have suspicious features (Fig. 8). Ultrasonography can also be performed electively for supplemental screening when there is concern that a suspicious mass could be obscured by the PCPO masses and/or dense parenchyma.

Fig. 3.

A 43-year-old woman was noted to have a changing pattern of multiple bilateral partially circumscribed, partially obscured (PCPO) masses on screening (A)CCand(B) MLO mammograms, most compatible with cysts, which were confirmed on screening ultrasonography (not shown). (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

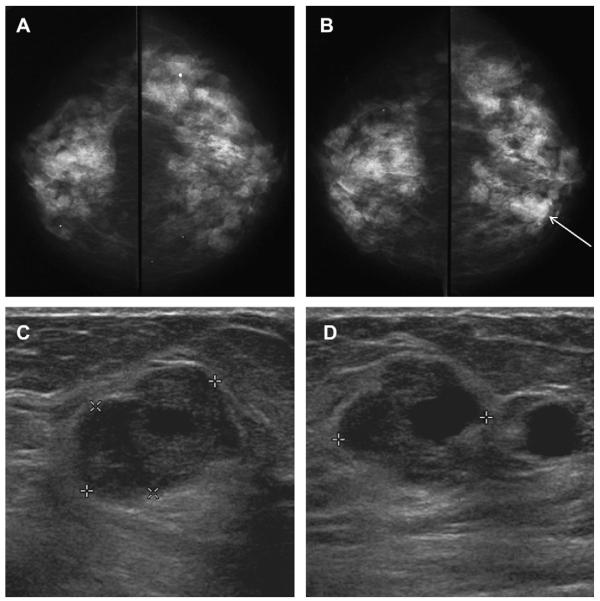

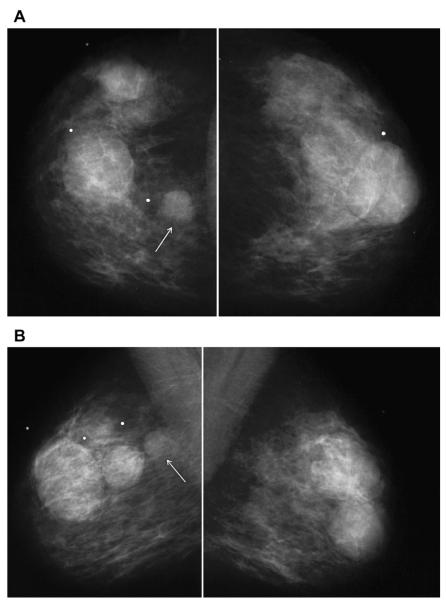

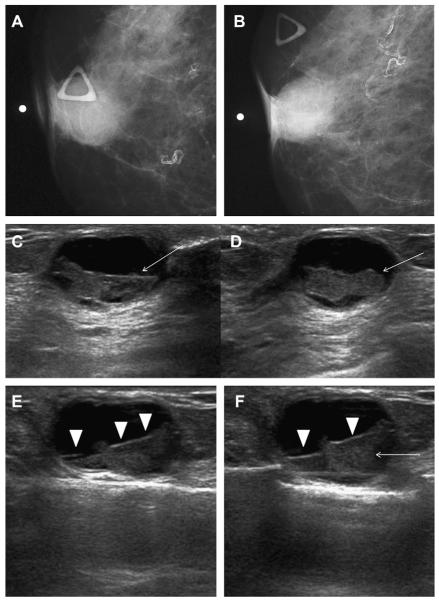

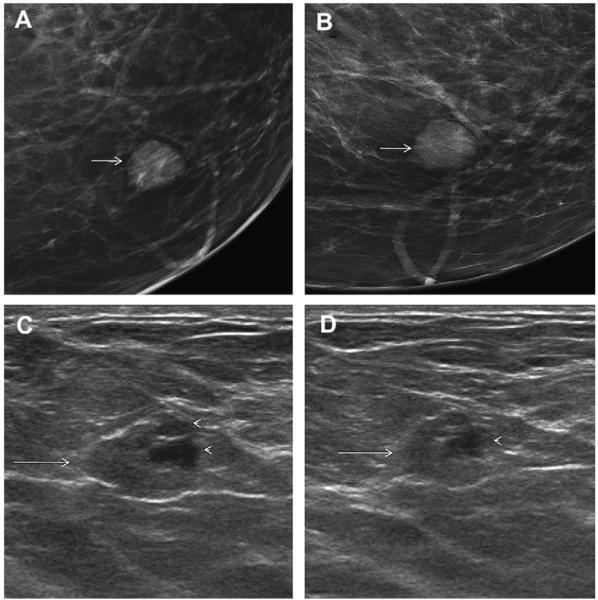

Fig. 6.

A 64-year-old woman has a changing pattern of bilateral PCPO masses on (A) initial CC views and (B) CC views obtained 3 years later. One slightly larger mass (arrow) was recalled for additional evaluation on the latter examination. (C) Radial and (D) antiradial ultrasonography targeted to the recalled mass showed a complex cystic and solid mass (denoted by calipers), as well as an adjacent simple cyst. Ultrasound-guided core biopsy and excision showed benign phyllodes tumor. Multiple simple cysts were also present in both breasts. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

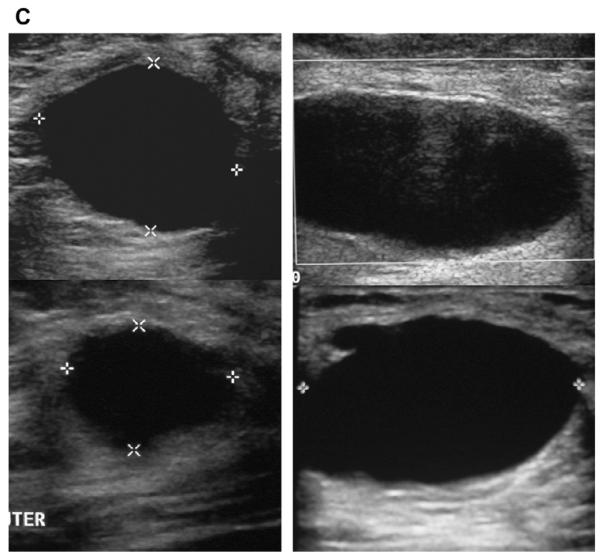

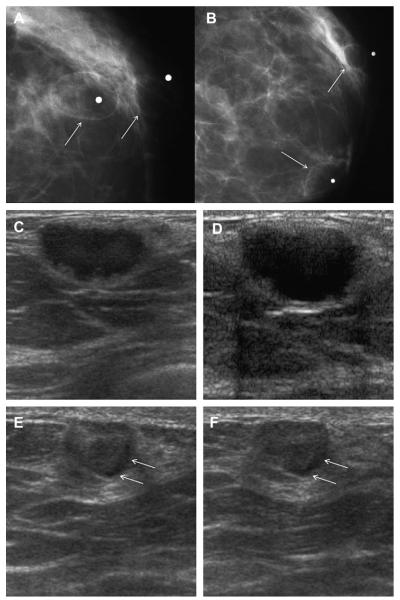

Fig. 7.

A 45-year-old woman had a history of cysts and now had bilateral tender palpable masses marked by radiopaque markers on (A) CC and (B) MLO mammograms. (C) Multiple static ultrasonographic images of the palpable lumps were interpreted as bilateral cysts. One lump was aspirated (upper inner right breast [marked by arrows in A and B]), yielding malignant cytology. (D) Repeat ultrasonography of the known malignant mass in the right breast at 2-o’clock position shows it to be indistinctly marginated and lobulated both without and (E) with spatial compounding. Any lesion documented on ultrasonography should have images recorded without calipers to facilitate margin assessment. Images of the tumor from the initial ultrasonography in part C (the bottom left image) had too narrow a dynamic range (effectively too few shades of gray); hence, the solid mass appeared anechoic. (F) Sagittal image from 3-dimensional fat-suppressed spoiled gradient echo (SPGR) MR imaging 1.5 minutes after 0.1 mmol/kg of gadolinium-based contrast injection shows an irregular enhancing mass (arrow) corresponding to the known grade III invasive ductal carcinoma. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

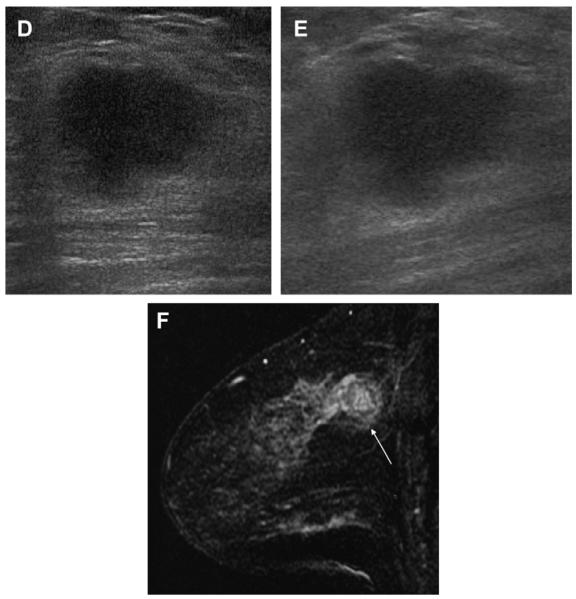

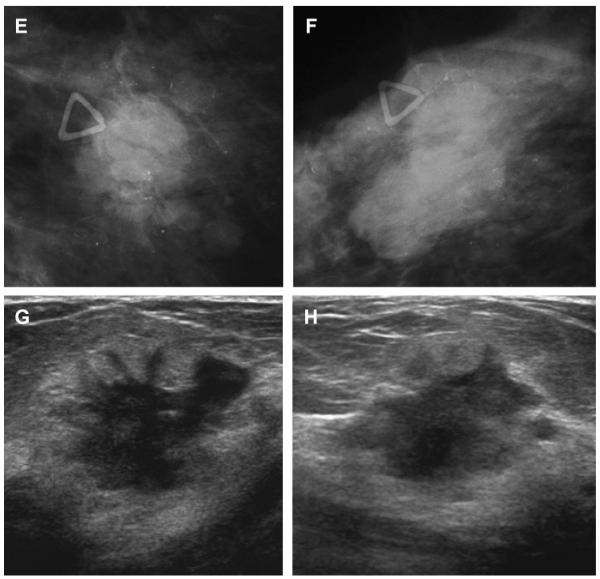

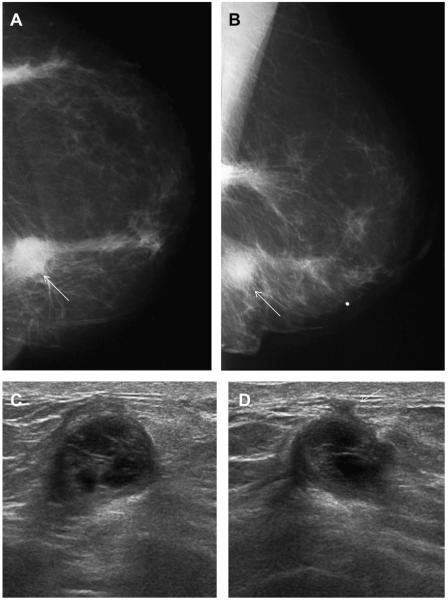

Fig. 8.

A 57-year-old woman had multiple bilateral PCPO masses on (A) CC and (B) MLO screening mammograms, compatible with cysts or other benign nodules. (C) CC and (D) MLO mammograms of the same woman, obtained 3 years later, show changing pattern of bilateral cysts as well as interval development of an indistinctly marginated dense mass at the site of a new palpable mass (marked by triangular markers). The mass is seen better on (E) spot compression CC and (F) close-up MLO views. (G) Transverse and (H) sagittal ultrasonographic images show an irregular complex cystic and solid mass with a surrounding echogenic halo, highly suggestive of malignancy. Ultrasound-guided biopsy and excision showed grade III infiltrating ductal carcinoma not otherwise specified, ER+, her2/neu−, with negative sentinel nodes. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

Sonography should be performed using high-frequency transducers, with a center frequency of at least 10 MHz and peak frequency of at least 12 MHz. With high-frequency transducers, cysts as small as 2 to 3 mm in size can be identified and characterized, although characterization of cysts was variable until a size of at least 8 mm was reached in an observer study.10 With gentle compression, a cyst frequently flattens, unlike most solid lesions.

If the mass is deeper than 3 cm from the skin, the transducer’s frequency may need to be decreased for adequate penetration. A sonographically simple cyst with the classic appearance (avascular, anechoic, oval or round mass with imperceptible wall and posterior enhancement) can be dismissed as a benign finding, although posterior enhancement may not always be apparent.4 Spatial compounding improves margin detection and decreases speckle and noise, although posterior features are less conspicuous (Fig. 7D, E).

Reverberation artifacts (Fig. 9) typically parallel the anterior wall of a cyst: on its way back to the transducer, the beam is reflected again off the anterior wall of the cyst to insonate deeper tissues again and thus takes longer to return to the transducer, and the imaged structure appears deeper than it really is. Tissue harmonic imaging can be used to reduce artifactual internal echoes.

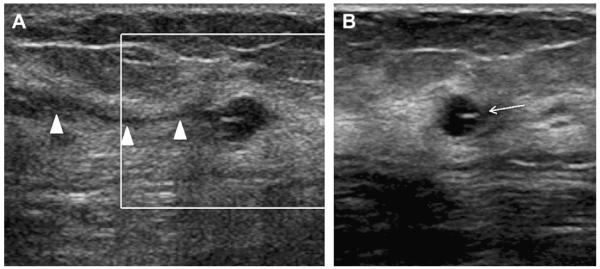

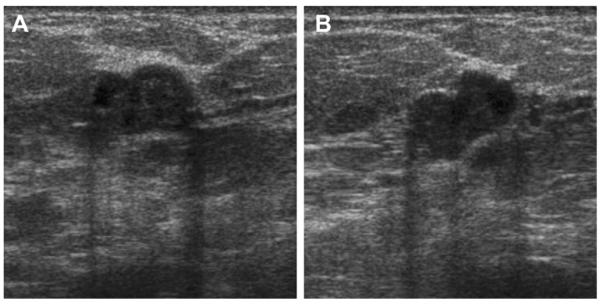

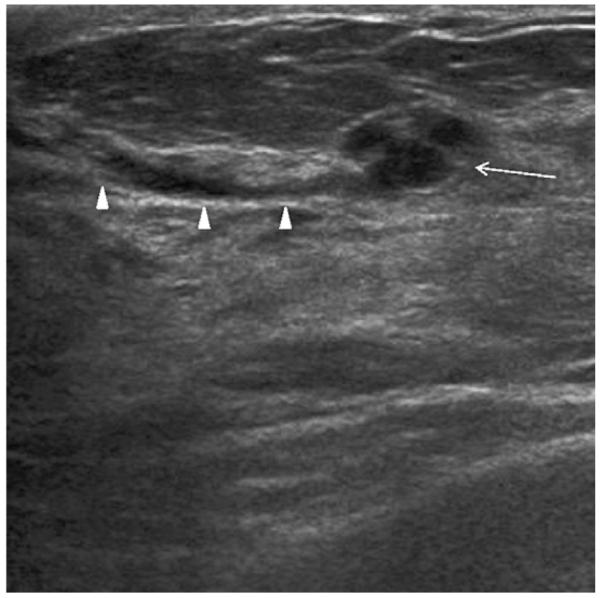

Fig. 9.

A 30-year-old woman presented for evaluation of palpable masses. The masses were shown to be cysts on (A) radial and (B) antiradial ultrasonographic images. The more superficial cyst shows reverberation artifacts paralleling the anterior wall of the cyst (arrowheads). (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

Thin (<0.5 mm) septations can be present in lobulated simple cysts (Figs. 2C, 10 and 11) or can appear to be present when several cysts abut each other (Fig. 12). Cysts can communicate with ducts (Figs. 13 and 14).

Fig. 2.

A 54-year-old woman was noted to have a new mass on screening mammography. (A) Close-up of mediolateral oblique (MLO) mammogram shows lobulated, circumscribed mass (arrow). (B, C) Targeted ultrasonography shows lobulated simple cyst corresponding to the mammographic abnormality, a benign finding. Apparent thin septation in image (C)(arrow) is due to lobulation of the cyst. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

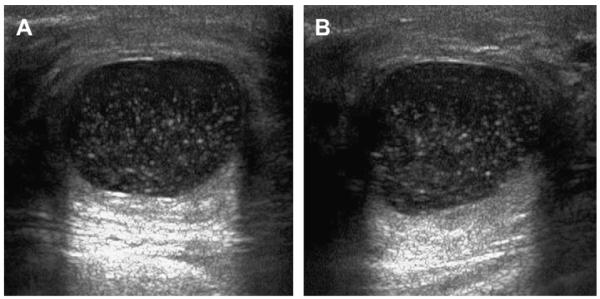

Fig. 10.

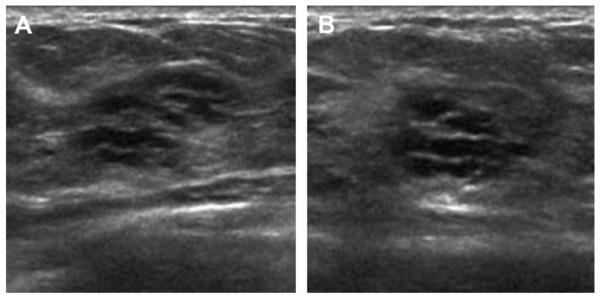

(A) Transverse and (B) sagittal ultrasonographic images (L12-5 MHz transducer) of a 47-year-old woman with incidental cyst containing a thin (<0.5 mm) septation (arrows) on ACRIN 6666 screening ultrasonography, which was stable for 3 years. This is a benign finding. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

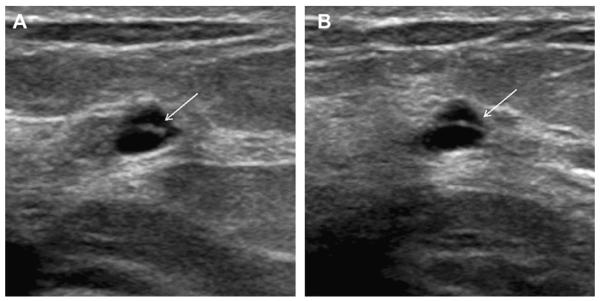

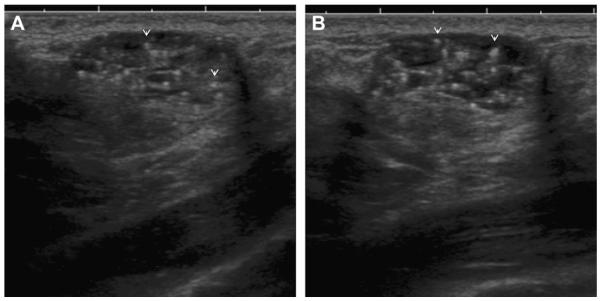

Fig. 11.

A benign cyst showing thin internal septation (arrows)on (A) radial and (B) antiradial ultrasonographic images in a 46-year-old woman. Often such cysts will be shown to communicate with each other if aspiration is attempted. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

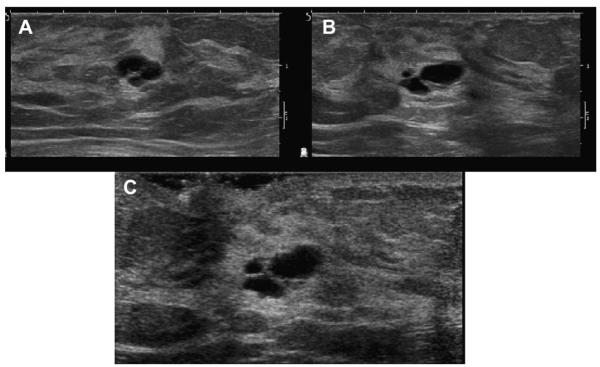

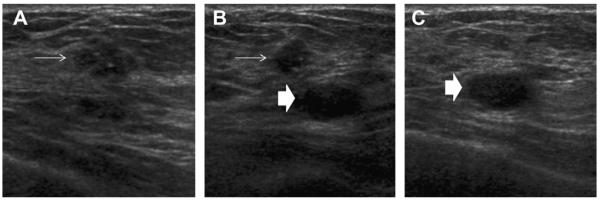

Fig. 12.

A 35-year-old woman was noted to have a mass that was initially questioned as a complex cystic and solid mass on (A) transverse sonography (L15-4 MHz transducer). On (B) sagittal and (C) radial images, the mass was shown to correspond to a group of adjacent small cysts. This is a benign finding. (Courtesy of Dr Linda Hovanessian Larsen, Keck University School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, via SuperSonic Imagine.)

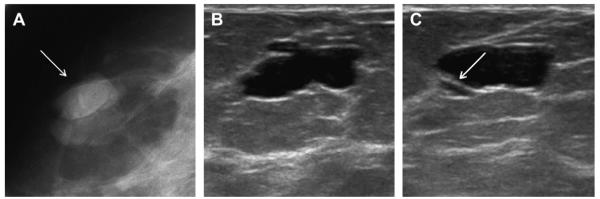

Fig. 13.

In the ACRIN 6666 protocol, on baseline screening a 54-year-old woman by (A) radial and (B) antiradial ultrasonography, a small cyst was incidentally identified, which communicates with a duct (arrowheads). The cyst contains a single thin septation (arrow). This is a benign finding. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

Fig. 14.

Radial ultrasonographic image shows incidental group of small cysts (arrow) communicating with a duct (arrowheads) in a 51-year-old woman who underwent screening ultrasonography due to a strong family history of breast cancer and dense breasts. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

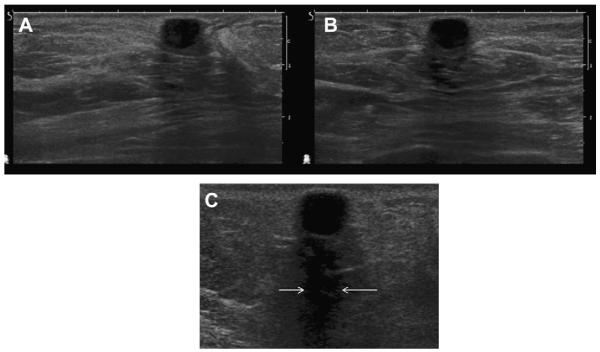

Elastography provides a measure of the stiffness of a lesion and is an option availble on most standard ultrasonographic equipment. Cysts are typically soft and many malignancies are hard. Compression elastography is an evolving technology, and different methods and algorithms are used by different manufacturers. Devices manufactured by Toshiba and Hitachi require gentle pressure to be applied with the transducer and released; cysts can have a trilaminar appearance on such an equipment (Fig. 15).11 With equipments from Siemens and Philips, normal patient respiratory motion is sufficient to generate an elastogram, although superficial or very deep lesions cannot be readily imaged, and there must be at least several centimeters of breast thickness. Softer lesions appear bright (Siemens and Philips) or green (Toshiba and Hitachi) and smaller on elastography than on B-mode ultrasonography, whereas stiffer lesions will appear darker (Siemens and Philips) or blue (Toshiba and Hitachi) and larger on elastography. With Siemens and Philips, a target or bull’s-eye appearance can be seen on elastography of cysts (Fig. 16)12,13 and cystic areas within complex masses (Fig. 17), and such appearance is due to subtle motion of the fluid (Richard Barr, MD, PhD, personal communication, 2010). With shear-wave elastography, low-frequency shear waves are propagated in tissue and elasticity of the tissue is quantitatively and reproducibly assessed (Claude Cohen-Bacrie, PhD, personal communication, 2010). Cysts can appear black internally on shear-wave elastography because shear waves do not propagate in nonviscous liquid (Fig. 18); fat and soft masses appear blue, and stiff lesions appear red on SuperSonic equipment (SuperSonic Imagine, Aix-en-Provence, France). Manufacturers are encouragedto adopt a consistent approach to color code stiffness.

Fig. 15.

A 39-year-old woman was followed up for cysts and complicated cysts. On (A) elastography with Hitachi equipment (or also Toshiba), cysts can have a layered and usually trilaminar appearance (arrows), appearing stiffer (blue on these devices) anteriorly and softer (red on these devices) posteriorly. Sometimes there is an apparent fourth layer (open arrow) in the region of posterior enhancement, analogous to the bright area on Siemens and Philips equipment. This is a simple cyst on (B) B-mode ultrasonography image. (Courtesy of Dr Christopher Comstock, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY.)

Fig. 16.

A 35-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a palpable abnormality and was noted to have a cyst on (A) and (C) conventional ultrasonography (L17-5 MHz transducer, Philips Ultrasound, Bothell, WA, USA). (B) On EI (elastography imaging) setting 2, a target or bull’s-eye appearance is seen (white arrow) in which the cyst is a void with a central bright area because of the motion of cyst fluid. Also, a bright area is noted just deep to the cyst (red arrow). (D) On EI setting 1, the cyst a black void (arrow) with posterior bright area. (Courtesy of Richard G. Barr, MD, PhD, Radiology Consultants, Youngstown, OH.)

Fig. 17.

A 40-year-old woman was found to have a mass on screening mammography. (A) Targeted ultrasonography showed an intraductal mass (arrow), which was hypervascular on power Doppler (not shown). (B) Elasticity image shows bull’s-eye appearance to the fluid (solid arrows) on either side of the solid, gray, stiffer, biopsy-proven papilloma (white arrow). Posterior bright areas (red arrows) are also noted deep to the cystic portions. (Courtesy of Richard G. Barr, MD, PhD, Radiology Consultants, Youngstown, OH.)

Fig. 18.

Simple cyst on (A) gray-scale (L15-4 MHz transducer) and (B) shear-wave elastography. Cysts typically appear mostly black or dark blue (ie, soft) on this type of elastography. (Courtesy of Dr Philippe Henrot, Nancy, France, via SuperSonic Imagine.)

With MR imaging, there is no contrast enhancement of simple cysts. The signal intensity of simple cysts parallels that of water (ie, hypointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2 or short T1 inversion recovery [STIR]).

Differential Diagnosis

Meticulous sonographic technique must be used, with the focal zone at the level of the mass and appropriate gain and gray scale. With too narrow a dynamic range, hypoechoic solid lesions can appear anechoic and mimic cysts (see Fig. 7). Metastatic adenopathy (Fig. 19), high-grade infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC) not otherwise specified (NOS), and mucinous and medullary carcinomas (2 special types of IDC) can present as nearly anechoic masses with posterior enhancement.14,15 Metastatic nodes are usually located in the axilla and may show vascularity on color or power Doppler; cysts do not show internal vascularity. Margin characterization is important: most cystic-appearing IDC or other malignancies show at least a focally indistinct margin or thickened wall and may show internal vascularity (Figs. 20 and 21). Images of all lesions, including cysts, should be documented without calipers (and electively with calipers also) in 2 perpendicular planes, so that the margins can be fully assessed by the interpreting physician (see Fig. 7).

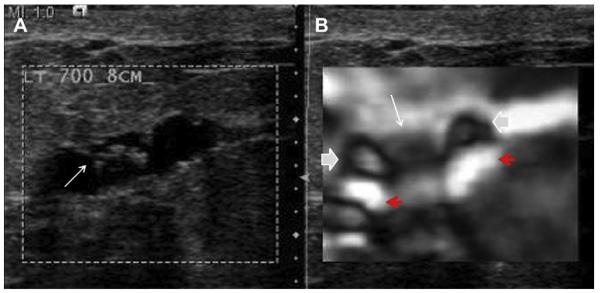

Fig. 19.

This 42-year-old woman had a palpable axillary mass, incorrectly attributed to cysts on (A) transverse sonography. (B) MLO mammograms show portion of a dense mass corresponding to the palpable axillary mass (arrow). Ultrasound-guided core biopsy showed metastatic grade III invasive ductal carcinoma. (C) Sagittal subtraction image from contrast-enhanced spoiled gradient echo (SPGR) MR imaging shows bulky, enhancing, axillary adenopathy (long arrow). Tiny enhancing breast lesion (short arrow) proved benign, and the primary was never identified. The patient underwent excision of the nodes, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy to the breast and was disease free 5 years later. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

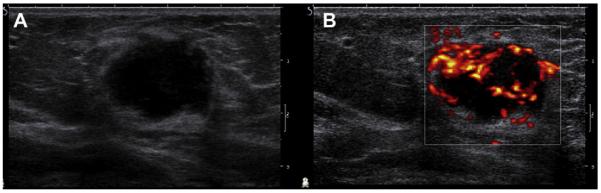

Fig. 20.

A 60-year-old woman was noted to have a nearly anechoic but slightly irregular mass on (A) ultrasonography. Internal vascularity was demonstrated on (B) power Doppler. Biopsy showed medullary carcinoma, a special type of invasive ductal carcinoma. (Courtesy of Dr Catherine Balu-Maestro, Centre Antoine Lacassagne, Nice, France, via SuperSonic Imagine.)

Fig. 21.

A 64-year-old woman underwent (A) ultrasonography, demonstrating a nearly anechoic irregular mass with posterior enhancement. (B) On power Doppler, marked internal vascularity was demonstrated, confirming the solid nature of this spindle cell sarcoma. (Courtesy of Dr David Cosgrove, Charing Cross Hospital, London, UK, via SuperSonic Imagine.)

Management

A palpable mass in a patient younger than 30 years should be evaluated initially with ultrasonography,16 and mammography is typically performedonly if sonographic and/or clinical features are suspicious for malignancy. If the patient is 30 years or older, typically mammography is performed first, followed by ultrasonography.

Simple cysts are primarily asymptomatic, although they can be palpable as soft mobile masses when they are large. Relaxed cysts, which are oval (flat), are usually asymptomatic. Tense, round cysts may require aspiration for symptomatic relief. A clearly benign cyst recommended for aspiration because of symptoms is still appropriately coded BI-RADS 2, benign1 and is not included as a positive imaging finding for auditing purposes (Edward A. Sickles, MD, personal communication, 2009).

The fluid of simple cysts can be clear or cloudy and yellow or greenish black. Cysts that communicate with ducts can produce nipple discharge. Greenish-black nipple discharge is typical of fibrocystic change communicating with the nipple and does not require further evaluation. Clear or milky nipple discharge only with stimulation is usually physiologic and does not require further evaluation.17 Spontaneous clear nipple discharge can be caused by papillomas or cysts or rarely by cancer (with 6% malignancy rate in one series18) and merits further evaluation with mammography and ultrasonography and rarely MR imaging or galactography. Bloody nipple discharge is typically caused by benign or malignant papillary lesions, with a 24% rate of malignancy in one series.18

COMPLICATED CYSTS: CYSTS WITH DEBRIS

Complicated cysts are masses that otherwise meet the criteria for simple cysts except that they are not anechoic, that is, they appear at least partially hypoechoic internally (Fig. 22). The internal echoes represent proteins from cell turn-over, hemorrhage, or pus, and such proteins can be collectively termed debris.

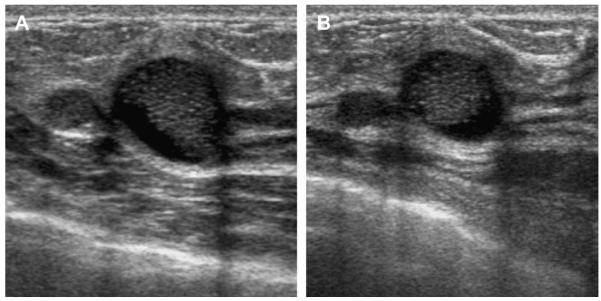

Fig. 22.

A 41-year-old woman presented with a palpable mass. (A) Radial and (B) antiradial ultrasonographic images (L12-5 MHz) showed oval circumscribed mass (arrows) with homogeneous low-level echoes and posterior enhancement, which is typical of a complicated cyst with debris. This mass was aspirated to resolution at patient request, yielding a cloudy yellow fluid that is typical of benign cyst content and therefore it was discarded. An adjacent simple cyst was incidentally noted. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

Demographically, there is no difference between simple and complicated cysts with peak incidence for both at 35 to 50 years of age. In the ACRIN trial, participants with and without cysts, complicated cysts, and other cystic lesions had the same demographics as the overall patient population of ACRIN 6666, with a median age of 49 to 54 years (range, 26–87 years).

Complicated cysts are frequently asymptomatic and often accompany simple cysts and can be painful and/or palpable when they are tense, in-flamed, infected, or rapidly enlarging. Infected cysts are often associated with overlying erythema. Rarely, nipple discharge can occur if there is communication with a duct. Over time, both simple cysts and cysts with debris can wax and wane in size and many will resolve spontaneously in weeks to years.

Across 6 prior series,19–24 only 2 (0.23%) of 868 lesions that were thought to be complicated cysts on sonography proved to be malignant (Table 3). One malignancy was a 3-mm ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) within a papilloma24 and the other was a 4-mm grade II IDC NOS.22 Of the 243 lesions that were prospectively classified as complicated cysts (including 15 clustered microcysts) in the series by Daly and colleagues,22 210 (86.4%) yielded fluid at diagnosis, 8 resolved or nearly resolved (3.2%) on puncture, and 7 (2.9%) had enough material for cytologic examination, 1 of which was atypical and showed myxoid fibroadenoma at excision. Of the 33 suspected complicated cysts not yielding fluid, a total of 19 were biopsied, of which 1 was malignant.22 Importantly, in the series by Buchberger and colleagues,20 7 (5.2%) of 133 complicated cysts did not yield fluid on attempted aspiration, with no malignancies; 24 (17%) of 141 did not yield fluid on attempted aspiration in the series by Venta and colleagues24 (including the 1 malignancy); and 33 (14%) of 243 did not yield fluid on attempted aspiration in the series by Daly and colleagues22 (including the 1 malignancy). Thus, over these 3 series,20,22,24 64 (12%) of 517 lesions that were thought to be complicated cysts proved solid, with 2 (3.1%) of such 64 solid lesions proving malignant.

Table 3.

Summary of outcomes of lesions described sonographically as complicated cysts

| Study, Year | Number | Number Aspirated or Biopsied (%) |

Number Malignant (%) |

Details of Malignancies |

Details of Benign |

Follow-up Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kolb et al,23 1998 | 126 | 30 aspirated | 0 | NA | Not distinctly reported | 96 followed |

| Venta et al,24 1999 | 308 | 123 | 1 (0.32) | 3-mm DCIS in a papilloma (6-mm mass) |

11 FA, 10 FCC, 5 cyst walls, 3 fibroses, 1 hamartoma, 1 lymph node |

161 followed, 24 no follow-up |

| Buchberger,et al20 1999 | 133 | 133 aspirated, 7 also core biopsied |

0 | NA | Not distinctly reported |

|

| Berg et al,19 2003 | 38 | 38 | 0 | NA | 19 cysts, 6 abscesses, 5 FCC, 2 fat necroses, 1 papilloma |

26 resolved, 1 enlarging papilloma excised, 1 each recurrent cyst and fat necrosis excised; 1 recurrent galactocele |

| Chang et al,21 2007 | 35 | 26 aspirated, 7 core biopsied, 2 excised |

0 | NA | 21 abscesses, 9 FCC, 4 cysts, 1 mucocelelike tumor |

|

| Daly et al,22 2008 | 228 | Aspiration attempted on all, no fluid in 33a |

1 (0.44) | 4-mm grade II IDC NOS, did not yield fluid (6-mm mass) |

4 abscesses, 2 FA, 1 ALH, rest were cysts and FCC |

|

| Total | 868 | 2 (0.23) |

Abbreviations: ALH, atypical lobular hyperplasia; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; FA, fibroadenoma; FCC, fibrocystic change; NA, not applicable, no entries.

Includes women with lesions prospectively classified as either clustered microcysts or complicated cysts; mean size 13 mm.

In the ACRIN 6666 protocol, complicated cysts in the setting of bilateral simple cysts could be dismissed as benign findings (BI-RADS 2).3 A solitary probable complicated cyst seen only on initial ultrasonography was classified as probably benign (BI-RADS 3).3 Aspiration was generally recommended only for isolated new probable complicated cysts or those with other suspicious features (BI-RADS 4).3 In year 1, of 296 complicated cysts, 132 (44.6%) were given BI-RADS 2 assessment; 135 (45.6%), BI-RADS 3; and 28 (9.5%), BI-RADS 4A (with 1 unknown). By year 3, of 224 complicated cysts, 176 (78.6%) were given BI-RADS 2 assessment; only 37 (17%), BI-RADS 3; and only 9 (4.0%), BI-RADS 4A. New complicated cysts in the setting of multiple simple cysts were dismissed as benign unless there were other suspicious features. Using this approach, only 1 malignancy was followed (Fig. 23), and 1 other malignancy was identified as a new complicated cyst on ultrasonography with biopsy recommended (Fig. 24). One other participant had bilateral complicated cysts during the first screening and was recommended for a 6-month follow-up, at which time a new mass was noted on ultrasonography and found to be malignant. Complicated cysts were seen in 376 (14.1%) ACRIN participants. Of those 376 participants with complicated cysts, 301 (80%) also had at least 1 simple cyst and 84 (22%) had multiple bilateral complicated cysts. Of the 7473 ultrasonographic studies in the 3 years of the ACRIN 6666 trial, 644 (8.6%) examinations showed at least 1 complicated cyst, with 475 such lesions identified (counting multiple bilateral similar complicated cysts as 1 lesion). Of the 475 lesions, 2 (0.42%) possible cysts with debris proved malignant (see Figs. 23 and 24, Table 4) and 2 were high-risk lesions (1 an atypical papilloma and 1 a ruptured cyst in year 1, which was excised in year 2 showing lobular carcinoma in situ). The malignancies were each found in breasts with concurrent ipsilateral cancer: for one, the lesion mistaken for a complicated cyst was a 6-mm invasive lobular carcinoma (see Fig. 23) ipsilateral to grade I IDC+DCIS, node negative; for the other, the lesion was IDC+DCIS ipsilateral to a second grade II IDC+DCIS, with nodal metastases (see Fig. 24).

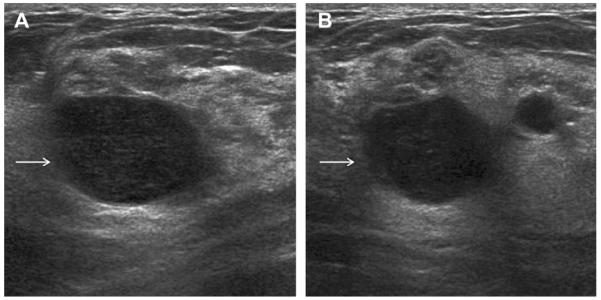

Fig. 23.

A 52-year-old ACRIN 6666 participant had multiple findings on her third annual screening ultrasonography, including multiple cysts. On (A) radial and (B) antiradial ultrasonography with power Doppler, a mass seen at 2-o’clock position in the left breast was thought to be a complicated cyst and was recommended for a 6-month follow-up. On (C) radial and (D) antiradial ultrasonographic images of the right breast, at the 12-o’clock position, a few calcifications were noted (red circles), which were dismissed as fibrocystic changes adjacent to several small cysts. No calcifications were seen mammographically. At follow-up after 7 months, (E) radial ultrasonography showed that the left breast mass had enlarged (arrow), prompting ultrasound-guided biopsy. This mass proved to be a 6-mm node-negative invasive lobular carcinoma. (F) Radial ultrasonography of the 12-o’clock position in the left breast appeared unremarkable. Follow-up (G) transverse and (H) sagittal ultrasonography on the right side showed an enlarging isoechoic mass with calcifications (red ovals). This mass proved to be a 6-mm grade I IDC+DCIS and node negative. Seen only on (I) CC and not on (J) MLO mammograms, a subtle area of distortion was noted in the 12-o’clock position of the left breast (short solid arrow), which proved to be a 5-mm tubular carcinoma (grade I IDC, special type) with associated DCIS. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

Fig. 24.

A 59-year-old ACRIN 6666 participant had prior left breast conservation therapy for cancer. On the third annual screening ultrasonography, 2 masses were noted in the outer right breast on (A) oblique, (B) antiradial, and (C) radial images. The first mass was nearly isoechoic, microlobulated, and contained echogenic calcifications (arrows) and was recommended for biopsy. Just deep to this mass was an oval mass with probable fluid-debris level which was thought to be a complicated cyst (short solid arrows). The first mass was proved to be a 12-mm grade II IDC with DCIS. The deeper mass was also excised and also proved to be grade II IDC with DCIS. Sentinel node showed metastatic disease. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

Table 4.

Prevalence and outcomes of cystic lesions in ACRIN 6666 among 2662 unique participants over 3 annual screening ultrasonographic examinations

| Descriptiona | Number of Participants (%) |

Number of Unique Lesionsb | Number of such Lesions Biopsied (%) |

Number of such Lesions Aspirated (%) |

Number Malignant (%) |

Details of Pathology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complicated Cystsc | 376 (14.1) | 475 | 34 (7.2)d | 40 (8.4) | 2 (0.42) | 1 ILC, 1 IDC-DCIS, 1 atypical papilloma, 1 ADH, 1 LCIS, 7 FA, 12 ruptured cysts, 1 granuloma/chronic inflammation, 4 FCC, 1 FIBR, 2 SA, 1 lymph node, 1 duct ectasia |

| Clustered Microcystse | 104 (3.9) | 123 | 5 (4.1) | 3 (2.4) | 1 (0.8)e | 1 ILC,e 1 AM, 1 FCC, 1 ruptured duct, 1 SA |

| Complex Cystic and Solid Lesionsf |

42 (1.6) | 45 | 20 (48)e | 6 (13) | 0 | 1 ADH, 4 papillomas, 4 FA, 2 ruptured cysts, 2 FCC, 2 AM, 2 FIBR, 1 duct ectasia, 1 SA, 1 was granulomatous |

| Hypoechoic Solid with Tiny Cystic Areasg |

32 (1.2) | 35 | 17 (49) | 4 (11) | 0e | 6 FA, 4 FCC, 1 AM, 2 SA, 1 FNx, 1 duct ectasia, 1 BBT, 1 PASH |

Abbreviations: ADH, atypical ductal hyperplasia; AM, apocrine metaplasia; BBT, benign breast tissue; FA, fibroadenoma; FCC, fibrocystic change; FIBR, fibrosis; FNx, fat necrosis; ILC, invasive lobular carcinoma; LCIS, lobular carcinoma in situ; PASH, pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia; SA, sclerosing adenosis.

Lesions are listed by their initial description; participants are listed more than once, if they had several types of cystic lesions.

Multiple bilateral complicated cysts were seen in 84 participants and are considered one such lesion each as were multiple bilateral clustered microcysts in 4 participants.

Seven lesions initially described as complicated cysts changed description on follow-up, none of which were malignant: 3 changed to complex, 1 to hypoechoic with cysts, and 3 to clustered microcysts.

Twelve complicated cysts also underwent initial attempt at cyst aspiration, as did 4 complex cystic and solid lesions, not listed among aspirations.

Four lesions initially classified as clustered microcysts changed description on follow-up: 1 became hypoechoic solid with tiny cystic areas and was biopsied, showing ILC; 2 became complex with no biopsy; and 1 became complicated.

One lesion initially classified as complex was later classified as clustered microcysts.

One lesion initially classified as hypoechoic solid with tiny cystic areas was later considered complicated and one was later considered complex.

Imaging Findings

Mammographically, both simple and complicated cysts are manifest as solitary or multiple, bilateral, PCPO, round or oval masses, and both simple and complicated cysts can show milk of calcium or, rarely, rim calcification. As with simple cysts, a pattern of fluctuation, with some regressing and others developing, is common. This pattern does not require further imaging (ie, ultrasonography) unless there is a new dominant or palpablelesion, although ultrasonography can be performed electively.

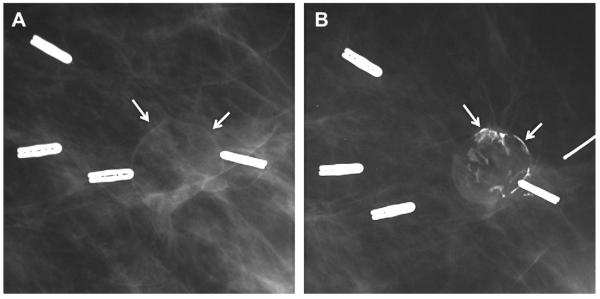

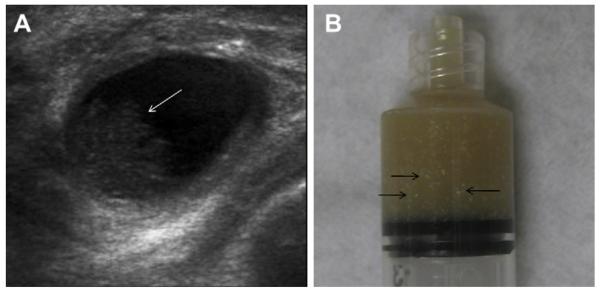

Most simple and complicated cysts are identified on sonography that is performed for evaluation of a clinical or mammographic abnormality or for screening. An oval, or less often round, mass with imperceptible walls, internal echoes, and posterior acoustic enhancement is classic. When a fluid-debris level is observed with no suspicious features (Fig. 25) or when the internal echoes are mobile on real-time evaluation (Fig. 26), the appearance is pathognomonic,1 although such appearances are relatively uncommon. In the ACRIN 6666 protocol, of the 376 participants with complicated cysts, 28 (7.4%) were reported to have fluid-debris levels and 23 (6.1%) had mobile internal echoes. Power Doppler can impart energy, which can allow motion of the debris to be visible. Rarely, a fluid-debris level can be present because of hemorrhage from an intracystic mass (Figs. 27 and 28). In such cases, turning the patient from supine to supine oblique position will prompt a change in appearance of debris and can allow visualization of any underlying mass (see Fig. 28; Fig. 29). If the debris is thick, up to 5 minutes may be needed between initial and repeat imaging.

Fig. 25.

On screening ultrasonography, a 54-year-old ACRIN 6666 participant was noted to have 2 small adjacent cysts with fluid-debris levels (arrows). These are complicated cysts with debris, benign findings, and such lesions do not require any follow-up. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

Fig. 26.

A 45-year-old woman noted a palpable lump. Targeted (A) radial and (B) antiradial ultrasonography show a complicated cyst containing echogenic cholesterol crystals, which were mobile on real-time evaluation. Aspiration can be performed electively for symptomatic relief, but this is a benign finding. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

Fig. 27.

A 68-year-old woman was noted to have a palpable mass at the nipple, marked by triangular markers on (A) spot compression CC and (B) MLO mammograms that show the palpable abnormality to correspond to a dense indistinctly marginated mass with overlying skin retraction. (C) Radial and (D) antiradial ultrasonography show intracystic mass (arrows). Additional oblique ultrasonographic images (E, F) show fluid-debris level (arrowheads) formed due to hemorrhage from the intracystic mass (arrow). A 14-gauge core biopsy showed atypical papilloma. Excision showed 8 mm of DCIS involving a papilloma, with 3-mm microinvasive colloid carcinoma. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

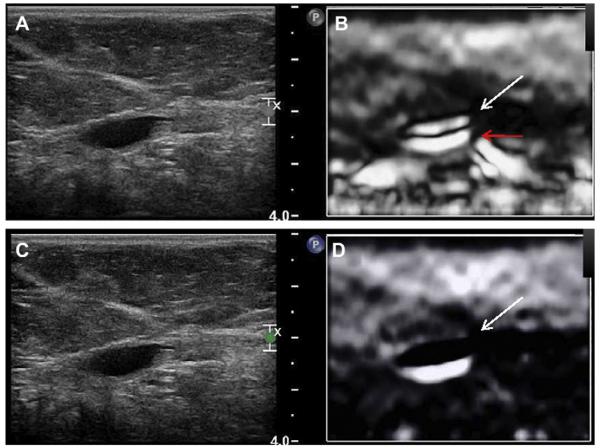

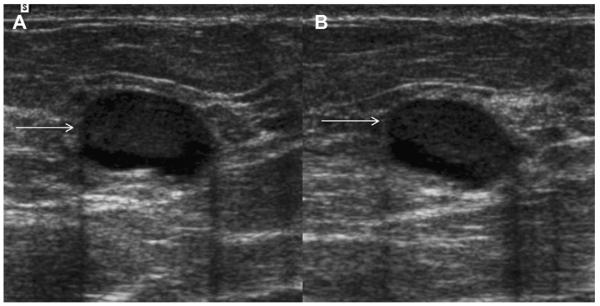

Fig. 28.

A 52-year-old woman had a palpable mass on the right breast. On standard (A) radial and (B) antiradial ultrasonographic images, the mass was cystic with a fluid-debris level (arrows). There was also a question of an intracystic mass (short solid arrow). The patient was then positioned (C) in the right-side decubitus and then (D) the left-side decubitus positions. The fluid-debris level shifted accordingly (arrows), and the intracystic mass persisted (short solid arrow). Ultrasound-guided aspiration was performed, yielding bloody fluid. Core biopsy of the residual mass showed papillary DCIS (which had bled, causing the fluid-debris level). (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

Fig. 29.

On screening ACRIN 6666 ultrasonography, a 54-year-old woman was noted to have a circumscribed oval mass with posterior enhancement in the outer right breast on (A) supine position. Internal echoes were noted, and it was uncertain whether the echoes represented debris or an intracystic mass. (B) The patient was then positioned in left lateral decubitus (LLD) position and reimaged after 3 minutes, showing a shift in the contents, which is consistent with debris. This is a benign complicated cyst with no evidence of an intracystic mass. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

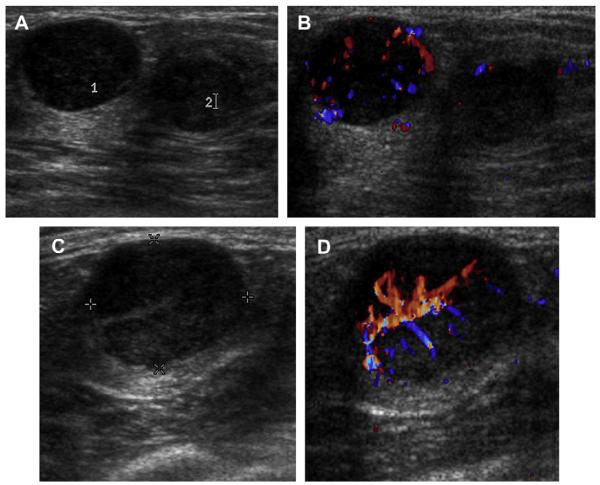

Complicated cysts with homogeneous low-level echoes can be difficult to distinguish from solid masses, and, indeed, as described earlier, 64 (12%) of 517 lesions prospectively classified as complicated cysts proved solid across three series.20,22,24 Complicated cysts are usually accompanied by simple cysts (as in 80% of AC-RIN 6666 participants previously described). Internal vascularity is not present in cysts and should prompt biopsy (Fig. 30). Harmonics can reduce false internal echoes. Spatial compounding improves margin evaluation and decreases speckle and noise at the expense of posterior feature characterization.

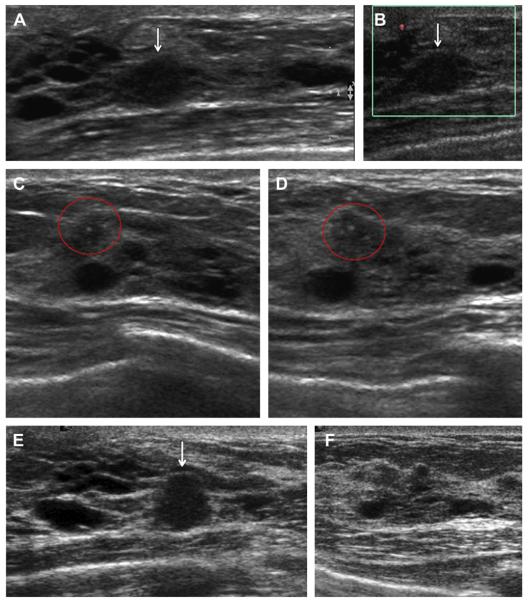

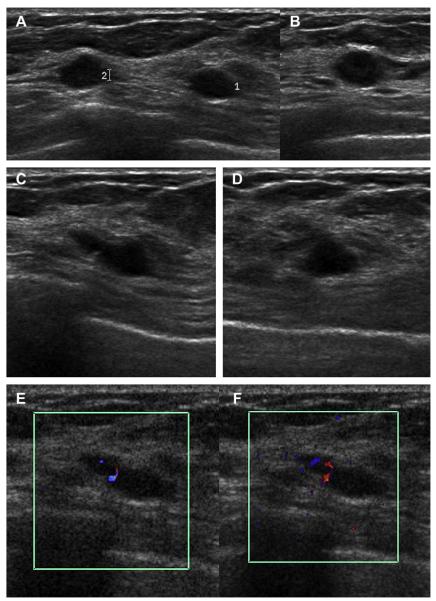

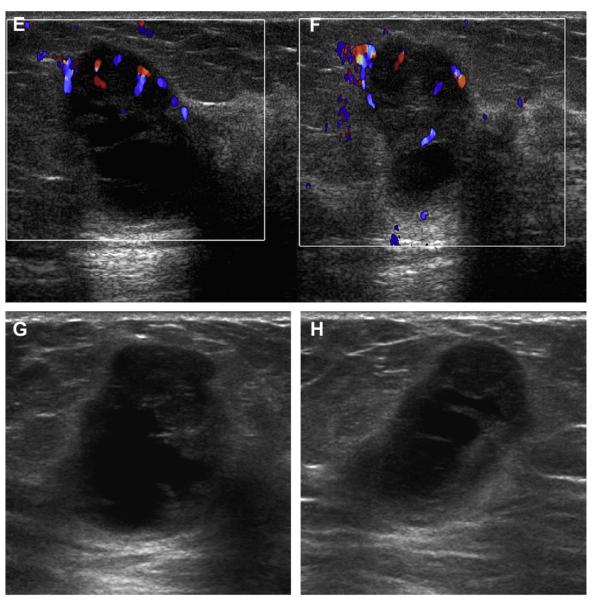

Fig. 30.

A 59-year-old woman with dense breasts was referred for biopsy of indeterminate calcifications in the right breast. Screening ultrasonography was performed, demonstrating 2 adjacent, mostly circumscribed, hypoechoic masses with posterior enhancement suggestive of complicated cysts (labeled 1 and 2) on (A) radial and (B) antiradial sonograms of mass 1. (C) Radial and (D) antiradial images of mass 2. Radial power Doppler images (E, F) of mass 2 show internal vascularity, which is not found with cysts. As such, biopsy was performed of both masses, showing multifocal grade III invasive ductal carcinoma. The original calcifications referred for biopsy proved to be high nuclear grade DCIS. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

Elastography can sometimes help distinguish a benign complicated cyst (Fig. 31) from a suspicious solid mass (Figs. 32 and 33), although further validation of this approach is needed.

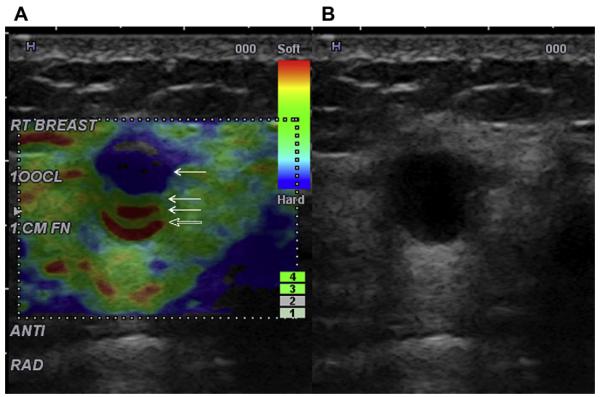

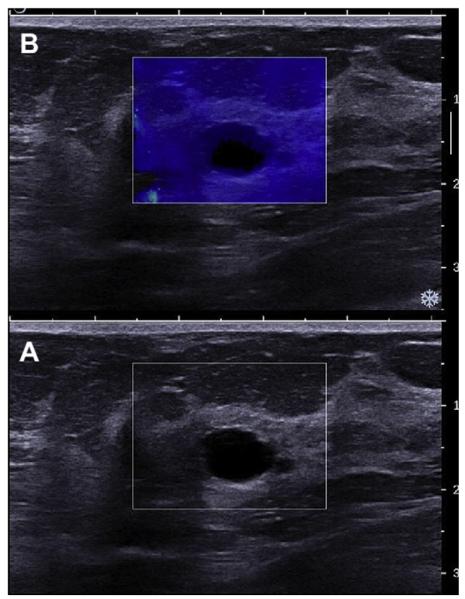

Fig. 31.

A 52-year-old woman underwent screening ultrasonography that showed an incidental circumscribed oval mass with uniform low-level echoes on (A) gray-scale image (arrow) compatible with either complicated cyst or solid mass. (B) Elastogram (Antarres, Siemens-Acuson, Mountain View, CA, USA) shows the lesion to have a bull’s-eye appearance, being centrally white and peripherally dark (arrow), that is typical of a cyst (in this case, a complicated cyst with debris). The lesion measured the same diameter on both images (dotted lines). Stiff lesions, including many cancers, tend to appear larger on elastography. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

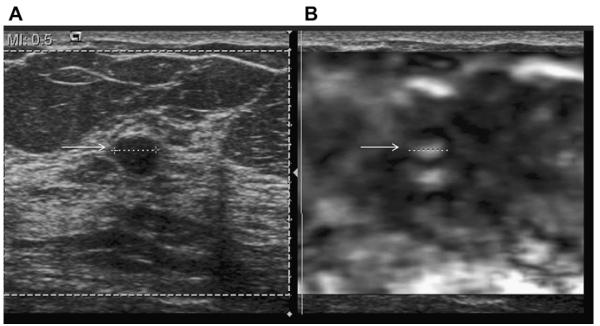

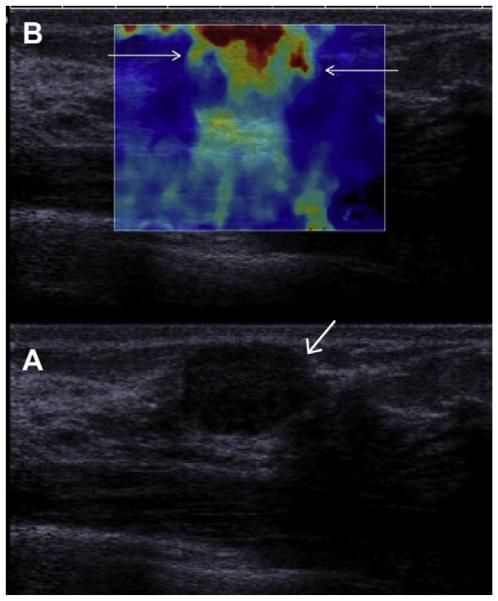

Fig. 32.

(A) On conventional gray-scale ultrasonography (L15-4 MHz transducer), a mass (arrow) is noted which appears mostly circumscribed with posterior enhancement and could be mistaken for a complicated cyst. (B) Shear-wave elastography, in which low-frequency shear waves are induced in the tissue, shows the lesion to be hard (as evidenced by the orange and red overlay, arrows) compared with the softer (blue) surrounding tissue, suggesting malignancy. This proved to be a fibroadenoma. (Courtesy of Dr Valerie Juhan, MD, Hospital La Timone, Marseille, France, via Super Sonic Imagine, Aix, Provence, France; with permission.)

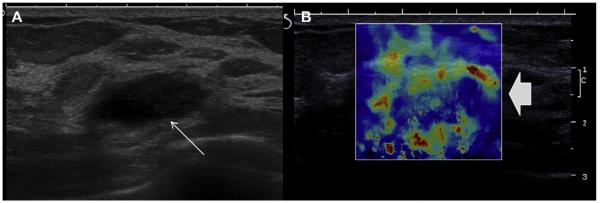

Fig. 33.

A 48-year-old woman with an oval mass on (A) radial (L15-4 MHz transducer) ultrasonography. The margins are mostly circumscribed, and there is a question of a fluid-debris level (arrow), suggesting a complicated cyst. (B) On a shear-wave elastogram, the lesion appears irregular (short solid arrow) and portions are stiff (red). Biopsy showed grade III IDC. (Courtesy of Dr Valerie Juhan, Hospital La Timone, Marseille, France, via SuperSonic Imagine.)

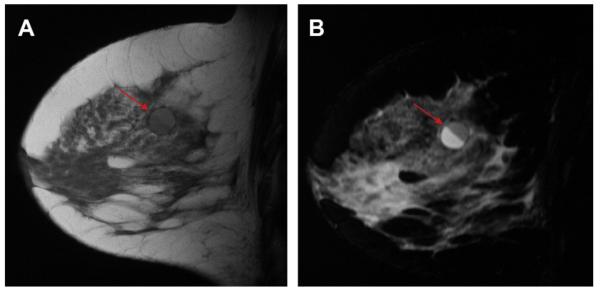

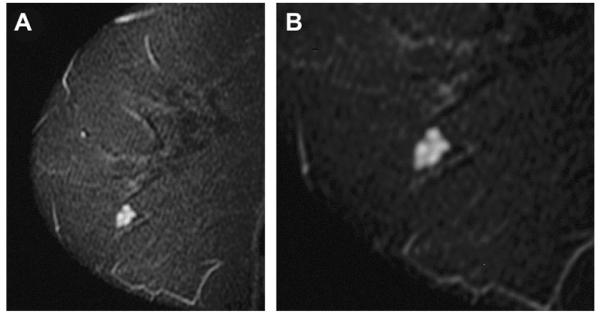

T1-weighted MR imaging demonstrates an oval, round, or gently lobulated mass with its signal dependent on the internal contents. Hemorrhagic and proteinaceous cysts appear hyperintense on T1 and hypointense on T2 or STIR. A fluid-fluid or fluid-debris level may be seen (Fig. 34).

Fig. 34.

On sagittal (A) T1- and (B) inversion-recovery weighted MR imaging performed for high-risk screening in a 47-year-old woman with a personal history of contralateral cancer, a smooth round mass with fluid-fluid level is seen (arrows), which is typical of a benign complicated cyst with debris. The more posterior component has a higher protein content than the anterior fluid. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

Differential Diagnosis

Small simple cysts can appear hypoechoic, with 21% of cysts measuring 4 mm or smaller in size described as solid masses in one series, as were 13% of cysts measuring 4.1 to 6 mm and 8% of cysts measuring 6.1 to 8 mm; all simple cysts larger than 8 mm were appropriately classified.10 Reverberation artifacts (see Fig. 9) can mimic debris.

Fibroadenomata are typically circumscribed oval masses, which are slightly hypoechoic or isoechoic to fat, with or without posterior enhancement (see Fig. 32). Internal echogenic septations may be evident within fibroadenomata and lactating adenomas (Fig. 35), and there can be vascularity adjacent to or even within such solid masses. Popcorn calcifications are best seen on mammography and are pathognomonic of fibroadenomata.

Fig. 35.

A 30-year-old woman was 24 weeks pregnant and noted a left breast lump. (A) Radial and (B) antiradial ultrasonographic images show a circumscribed oval mass isoechoic to fat with internal echogenic septations (arrowheads). Biopsy showed lactating adenoma. (Courtesy of Dr Ellen Mendelson, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, via SuperSonic Imagine.)

Sonographically, oil cysts can be anechoic or can have low-level echoes or fluid-debris levels (discussed later). They may or may not show posterior enhancement and can even shadow. Mammographically, oil cysts are lucent and can develop rim/dystrophic calcification, the latter contributing to posterior shadowing on ultrasonography. There may be other evidence of fat necrosis (discussed later).

Galactoceles are associated with pregnancy or breastfeeding. Finding an echogenic fat plug (Fig. 36) or fluid-debris level with nondependent hypoechoic fat can suggest the diagnosis of galactocele (Fig. 37). Internal vascularity implies a solid mass and should prompt biopsy (Fig. 38).

Fig. 36.

A 18-year-old pregnant woman noted a palpable mass in her left breast. On targeted ultrasonography, a circumscribed mass with low-level internal echoes and posterior enhancement was noted, as well as a focal echogenic area representing a fat plug (arrow) in this galactocele, which was aspirated to resolution. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

Fig. 37.

A 36-year-old woman noted a lump 6 months post partum. Targeted (A) radial and (B) antiradial ultrasonography demonstrate nondependent fat-containing echogenic debris (arrows) with fluid-debris level, typical of benign galactocele. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

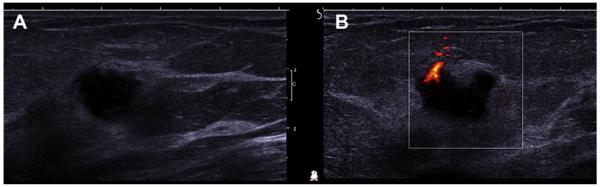

Fig. 38.

A 36-year-old breastfeeding woman noted a lump. (A) Targeted ultrasonography demonstrated 2 adjacent hypoechoic masses (labeled 1 and 2). Mass 1 appears mostly circumscribed but has internal vascularity on (B) color Doppler. The suspicious nature of these findings was not initially recognized, and the patient was recommended for a 3-month follow-up ultrasonography. (C) On follow-up ultrasonography, both masses had enlarged, and (D) mass 1 was shown to be even more vascular on color Doppler. Ultrasound-guided core biopsy showed grade III IDC from both masses. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

Abscesses are most often found near the nipple, with bacteria entering through cracks in the skin (Fig. 39). Abscesses usually produce clinically evident pain and often erythema and are more frequent with breastfeeding, trauma, or surgery. Most abscesses will have a thick and/or irregular wall (ie, complex cystic lesion), although 6 (33%) of 18 abscesses appeared to be complicated cysts in one series.19 In the series of symptomatic cystic lesions reported by Chang and colleagues,21 of the 35 complicated cysts with homogeneous low-level echoes, 21 (60%) were abscesses, 9 (26%) fibrocystic changes, 4 (11%) cysts had debris, and 1 (3%) was a mucocele-like tumor excised, (benign). With abscesses, there is usually increased echogenicity in the surrounding parenchyma because of associated edema. Increased vascularity may be evident adjacent to abscesses on color or power Doppler.

Fig. 39.

A 43-year-old woman had a history of recurrent subareolar abscesses in the left breast. (A) CC mammogram shows a dense oval mass in the subareolar region. (B) Transverse ultrasonography shows a circumscribed oval mass with posterior enhancement at the site of a mammographic and palpable tender mass. Sonographically this mass has the appearance of a complicated cyst with debris. (C) On incision for ultrasound-guided aspiration, pus spontaneously drained from the mass (arrow). (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

As mentioned earlier, malignancies are rarely mistaken for complicated cysts. Intraductal papillary DCIS rarely can bleed and obscure the mass and produce a fluid-debris level (see Figs. 27 and 28). High-grade IDC, NOS, can present as a round or oval hypoechoic mass with posterior acoustic enhancement (see Fig. 30).15 Although most of the margin can appear circumscribed with IDC NOS, usually at least a portion of the margin is indistinct or angular and/or there will be evidence of a complex cystic and solid mass (discussed later) with thickened wall, thick septations, or intracystic mass.

Management

Mammographic or sonographic bilateral fluctuating cysts, both simple and complicated, may be dismissed as benign, BI-RADS 2, with routine mammographic (and, optionally sonographic) screening performed.

Asymptomatic complicated cysts with fluid-debris levels or mobile internal echoes are benign, BI-RADS 2, with no follow-up needed.

An isolated noncalcified mass, which may be a fibroadenoma or complicated cyst on ultrasonography, noted on baseline examination or incidentally noted on ultrasonography can be considered probably benign, BI-RADS 3, with 6-, 12-, and 24-month surveillance. Gradual enlargement, defined as a 20% or less increase in diameter in 6 months, is acceptable for fibroadenomata25 and certainly also for complicated cysts. Although typically biopsy is performed for palpable masses compatible with fibroadenomata, surveillance seems to be a reasonable alternative, with 1 malignancy (1.5-mm DCIS) among 375 palpable masses in one series (0.3% malignancy rate26) and no malignancies among 157 such masses in another series.27

A BI-RADS 4 assessment, with recommendation for aspiration and possible biopsy if the mass proves to be solid, is appropriate in the following situations:

Palpable, tender, possible abscess

Diagnostic uncertainty (ie, possibly solid) and mass is new, or enlarging (more than 20% increase in diameter in 6 months)

Other suspicious features are present, such as suspicious calcifications, indistinct margin on mammography, distortion, or mass is actually a complex cystic lesion (ie, intracystic mass, thick wall of ≥0.5 mm, thick septations of ≥0.5 mm, mixed cystic and solid lesion).

Aspiration is performed with an 18- to 20- gauge needle. Use of ultrasonographic guidance facilitates aspiration to resolution. An equal volume of room air can be instilled at the conclusion of the procedure to decrease the risk of recurrence.28,29 Typical cyst fluid is clear or cloudy and yellow or greenish black. Unless the fluid is bloody (especially old blood) or pus, it can be discarded. When bloody, the fluid should be sent for cytologic examination and the cyst should be marked with a clip placed under sonographic guidance, although the risk of malignancy in this situation is exceedingly low. Indeed, among 6782 aspirates sent for cytologic examination in the series by Ciatto and colleagues,30 no malignancies were identified, although there were 5 papillomas among the 2% of aspirates which were bloody. Sending typical cyst fluid for cytologic examination may result in false-positive results and unnecessary further treatment. In the series by Smith and colleagues,31 660 aspirates were sent for cytologic examination and 33 (5%) produced an atypical result with no malignancies on surgery or follow-up and 86 (13%) were acellular and nondiagnostic but none were malignant. Similarly, Hindle and colleagues32 reported all 689 nonbloody aspirates in their series produced only acellular, benign, or nondiagnostic cytology.

OIL CYSTS

An oil cyst is a round or oval, liquid, fat-containing, encapsulated lesion. The cause is usually trauma, although the trauma can be so minor as to be unnoticed by the patient. Oil cysts can often occur after surgery and irradiation. Oil cysts are most commonly seen in superficial subcutaneous and subareolar tissues, which are the most mobile and most vulnerable regions to trauma. Ischemia can result in cell death and fat necrosis, particularly at the periphery (upper outer quadrant) of transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap reconstructions, where the blood supply is most tenuous.

Oil cysts are a special type of fat necrosis, which occurs when fat cells are damaged and release their lipid content into surrounding parenchyma. The lipids are broken down into fatty acids, which then are surrounded by a fibrous capsule. The capsule calcifies over time, with calcifications typically seen 2 years after the original trauma.

Clinical presentation is related to underlying cause and ranges from asymptomatic on screening to tender or nontender palpable masses. No treatment is needed as there is no association with malignancy. Oil cysts occur at any age in men and women, being much more frequent in women.

Imaging Findings

Oil cysts are easily recognized on mammography as round or oval, circumscribed, lucent masses with a thin capsule. Over time, usually beginning after 1.5 to 2 years,33 the capsule can calcify due to saponification of the fatty acids. Eggshell or rim calcification of a lucent mass is pathognomonic of an oil cyst (Fig. 40), and dystrophic calcifications are simply more densely calcified oil cysts/fat necrosis.

Fig. 40.

A 64-year-old woman underwent lumpectomy and radiation therapy for tubular cancer. On (A) MLO mammography 18 months after surgery, a circumscribed lucent mass is noted at the lumpectomy site, which is compatible with an oil cyst (arrows). On (B) follow-up MLO mammography 6 months later, the oil cyst is slightly smaller and has developed peripheral rim calcification (arrows). (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

The sonographic appearance of oil cysts is variable and depends on the composition of the lesion (Figs. 41 and 42). The mass is typically round or oval and anechoic if simple liquid fat is present (see Fig. 42). With increasing complexity and calcification, internal septations and echogenic bands can be seen, as can thickened walls, echogenic mural masses (see Fig. 41C, D), and fluid-debris levels (see Fig. 41E, F) with the fat echogenic and nondependent as in galactoceles. Posterior enhancement can be seen, but posterior shadowing is common with oil cysts (see Fig. 42) and is sometimes caused by peripheral calcification. No flow is seen with color or power Doppler. Acutely, other stigmata of fat necrosis can be seen, such as edema in the surrounding parenchyma and mixed anechoic and hyperechoic collections from trauma or surgery.

Fig. 41.

A 37-year-old woman is 18 months postreduction mammoplasty and noted 2 palpable lumps (marked with radiopaque markers). On close-up (A) CC and (B) MLO mammograms, the masses are shown to be circumscribed and lucent, typical of benign oil cysts (arrows). Ultrasonography was nonetheless performed because of other abnormalities. (C) Transverse and sagittal ultrasonographic images of the mass in the 6-o’clock position show a nearly anechoic mass with thick nodular wall and no posterior features. Without the mammogram, the sonographic appearance would be indeterminate. (E) Radial and (F) antiradial ultrasonographic images of the oil cyst at 12-o’clock position show it to be mostly (but not completely) circumscribed, nearly isoechoic to surrounding fat, and to contain a thin eccentric rim of fluid (arrows). (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

Fig. 42.

A 72-year-old woman had a superficial palpable mass. On targeted (A) radial and (B) antiradial ultrasonography, the mass appeared circumscribed but produced minimal low-level echoes. Posterior shadowing (arrows) was evident in (C) fundamental ultrasonographic image without spatial compounding. These features are fundamentally indeterminant on ultrasonography but can be seen with oil cysts, as in this case, which was aspirated, showing red oily fluid. (Courtesy of Dr Valerie Juhan, Hospital La Timone, Marseille, France, via SuperSonic Imagine.)

MR imaging demonstrates a well-defined, hyper-intense, round to oval mass on T1-weighted images, which has decreased signal on T2W images. With contrast, a thin enhancing rim can occasionally be seen.

Differential Diagnosis

Imaging findings of oil cysts are pathognomonic on mammography and MR imaging. Sonographic findings can be correlated with the mammogram by placing a radiopaque marker under ultrasonography and repeating the mammogram if needed.

Management

Oil cysts are benign findings, BI-RADS 2.

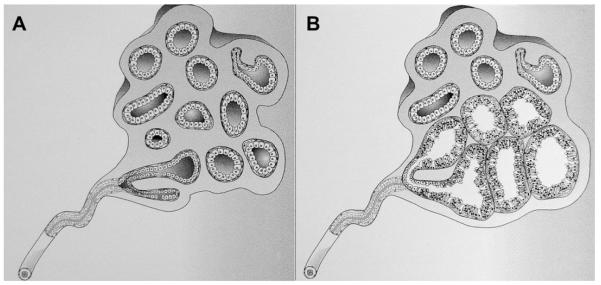

CLUSTERED MICROCYSTS

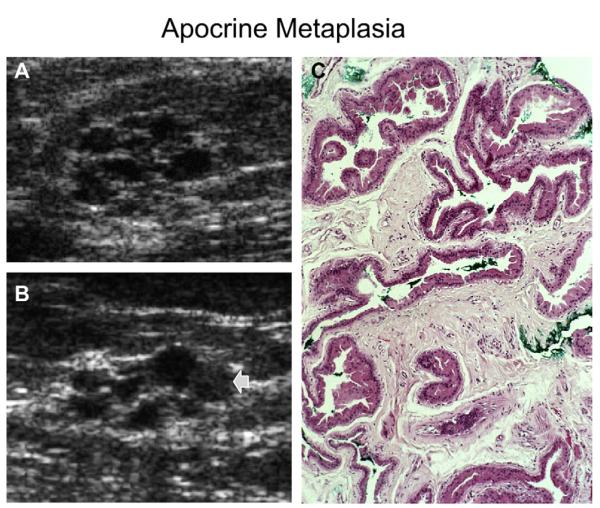

Clustered microcysts represent the terminal duct lobular unit, or a portion of it, where there has been cystic dilatation of individual acini (Fig. 43).1,34 Clustered microcysts are a part of the spectrum of benign cystic change of the breast and can be lined with bland or apocrine metaplastic epithelium (see Fig. 43; Figs. 44 and 45). Stigmata of fibrocystic changes, with simple cysts, fibrosis, and adenosis, are also often present.

Fig. 43.

(A) A normal terminal duct lobular unit (TDLU) composed of numerous acini lined by bland epithelium. (B) A group of acini are cystically dilated with tall cuboidal epithelium: ie, apocrine metaplasia. When imaged with ultrasonography, the TDLU in B is seen as clustered microcysts. (Reprinted from Warner JK, Kumar D, Berg WA. Apocrine metaplasia: mammographic and sonographic appearances. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1998;170:1375–9; with permission.)

Fig. 44.

(A) Radial and (B) antiradial ultrasonographic (10 MHz linear array transducer) images of an incidental mass on baseline screening mammography in a 95-year-old woman show typical appearance of clustered microcysts, one of which appears to contain debris (arrow). (C) Low-power (10× magnification) view of hematoxylineosin staining of 14-gauge core biopsy shows distended acini with tall, cuboidal, apocrine metaplastic epithelium. (Reprinted from Warner JK, Kumar D, Berg WA Apocrine metaplasia: mammographic and sonographic appearances. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1998;170:1375–9; with permission.)

Fig. 45.

A 70-year-old ACRIN 6666 participant was noted to have incidental clustered microcysts (arrows) on screening (A) radial and (B) antiradial ultrasonographic images. Ultrasound-guided core biopsy was performed because of diagnostic uncertainty and it showed fibrocystic changes, apocrine metaplasia, cyst wall inflammation, and periductal fibrosis. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

Clustered microcysts are most common in perimenopausal women aged 39 to 50 years (median 48 years)35 and were found in 5.8% of consecutive breast ultrasonographic examinations in one series.35 Typically, these are found as an incidental finding on mammography, ultrasonography, or both. One-half of clustered microcysts are stable at 1-year follow-up, and at 2 years, approximately 20% resolve, approximately 20% decrease in size, and approximately 10% increase in size, after which they are stable or they resolve.35

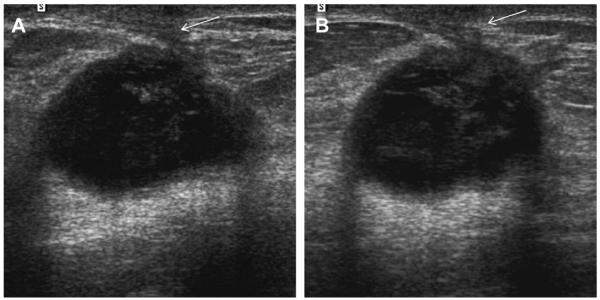

Across 4 prior series, no malignancies were found among 112 lesions described as clustered microcysts (Table 5). On the initial screening ultrasonographic examination in the ACRIN 6666 trial, 64 (2.4%) of 2659 women were reported to have clustered microcysts, although this may be underreported as some may have been included among simple cysts. Over the 3-year ACRIN 6666 experience, of 123 unique lesions described as clustered microcysts, 1 (0.8%) proved malignant (a 4-mm node-negative invasive lobular carcinoma). The malignant lesion appeared solid with distortion during the second screening and may not have even been the same lesion (Fig. 46). Over three years of ACRIN 6666, clustered microcysts were found in 104 (3.9%) of 2662 participants.

Table 5.

Summary of outcomes of lesions described sonographically as clustered microcysts

| Study, Year | Number | Number of Lesions Biopsied | Follow-up Details | Number Malignant | Results of Biopsies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berg,19 2003 | 16 | 16 | After biopsy, 9 resolved, 2 decreased, 2 stable, 2 NA, 1 rebiopsied was benign |

0 | 7 AM, 6 FCC, 2 cysts, 1 FA |

| Berg,35 2005 | 79, only 66 newb | 13b | ≥2-y follow-up on 66 lesions: 35 (53%) stable, 15 (23%) resolved, 12 (18%) decreased, 4 (6%) initially increased then were stable or decreased |

0 | 5 AM, 5 FCC, 2 cysts, 1 FAb |

| Chang et al,21 2007 | 15 | 10 aspirated, 4 core biopsied, 1 excised |

Follow-up of some lesions, details not clear |

0 | 15 cysts or FCC |

| Daly et al,22 2008 | 15 | 218 aspirated, 32 biopsiedb | All followed, details not specified |

0 | See Table 1 |

| Total | 112b | 0 |

Abbreviations: AM, apocrine metaplasia; FA, fibroadenoma; FCC, fibrocystic changes; NA, not available.

All 13 biopsied lesions in the study by Berg, 200535 overlap with the 16 lesions reported in the study by Berg et al, 200319 and are thereby excluded from the total of 79 lesions in the study by Berg, 2005,35 that is, only the 66 lesions which were followed (not biopsied) in the study by Berg, 200535 are new and therefore listed in the overall total.

Includes women with lesions prospectively classified as either clustered microcysts or complicated cysts; mean size 13 mm.

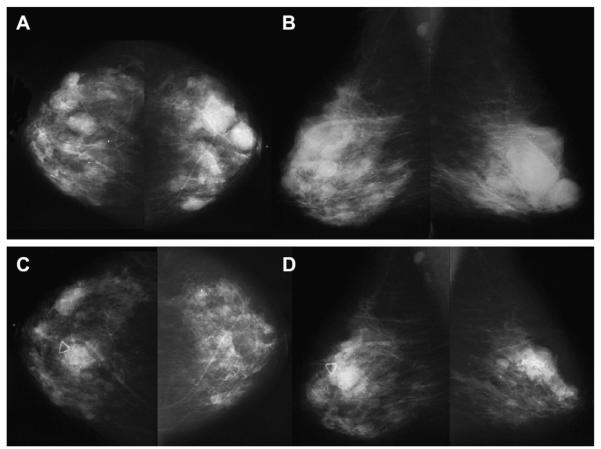

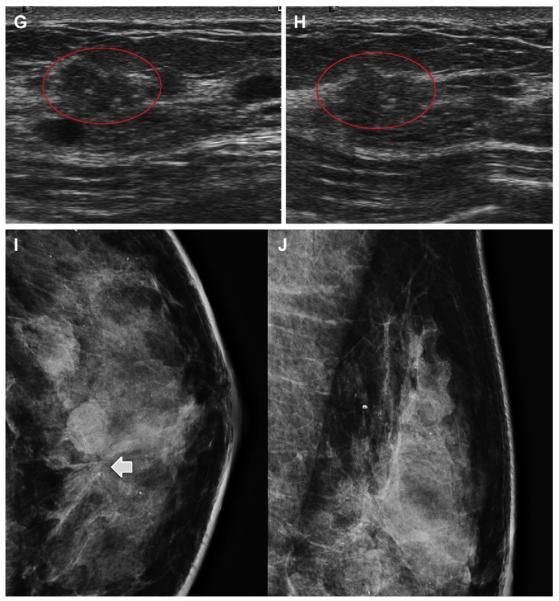

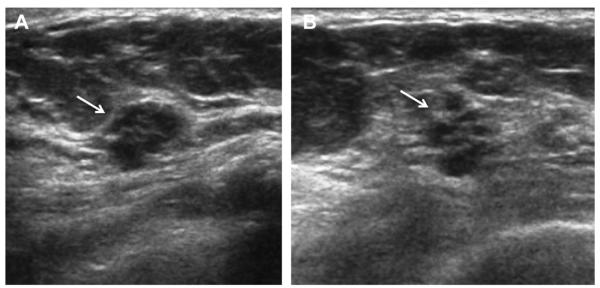

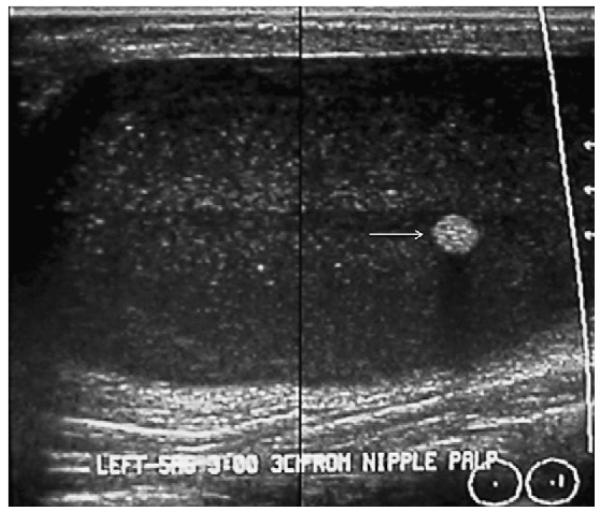

Fig. 46.

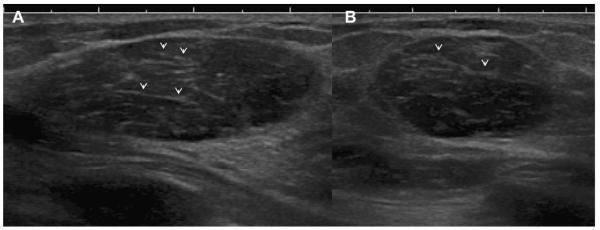

A 42-year-old ACRIN 6666 participant was noted to have a mass attributed to clustered microcysts on screening ultrasonography (A, radial and B, antiradial images). At screening ultrasonography 12 months later, ultrasonography of the same area demonstrated a subtle irregular isoechoic mass (arrows) on (C) radial and (D) antiradial images. It seems that the original clustered microcysts resolved and a new lesion has formed. Biopsy showed a 4-mm invasive lobular carcinoma. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

Imaging Findings

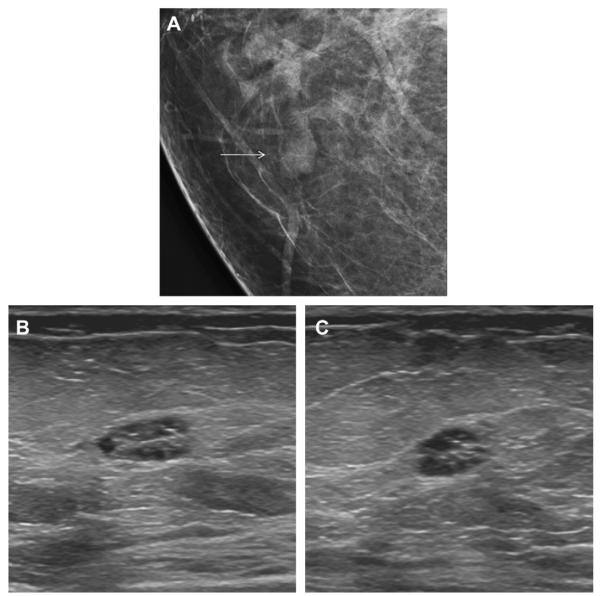

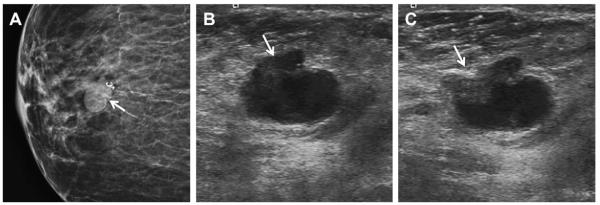

Mammographically, clustered microcysts manifest as a microlobulated or oval mass with circumscribed or partially obscured margins of equal or low density when compared with the surrounding parenchyma (Fig. 47). Milk of calcium can be seen (Fig. 48).

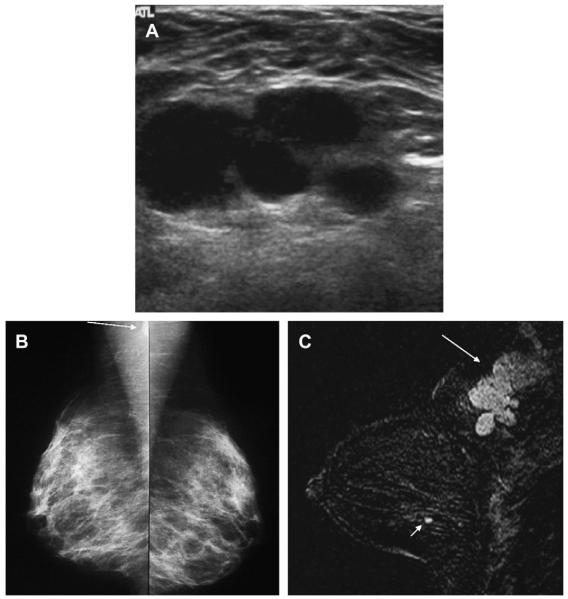

Fig. 47.

A 59-year-old woman who used hormone replacement therapy had a PCPO low-density mass (arrow)in the inner right breast, as seen on (A) spot compression mammographic image. (B) Radial and (C) antiradial targeted ultrasonography (13 MHz linear array transducer) demonstrates an oval circumscribed mass composed of microscopic cysts, that is, clustered microcysts. The mass has been stable for 4 years. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

Fig. 48.

A 62-year-old woman was noted to have loosely grouped punctate calcifications on (A) mediolateral magnification mammogram (arrow). The calcifications were shown to be within clustered microcysts on (B) targeted ultrasonography (arrowheads). (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

Sonographically, a circumscribed, microlobulated or oval mass is seen, composed of multiple small adjacent cysts separated by thin (<0.5 mm) septa (see Figs. 43–48; Fig. 49). The septations represent the equivalent of 2 acini walls lying back to back (ie, epithelial and myoepithelial layers of each acinus). Mean size is 8 mm with a range from 5 to 30 mm, with individual microcysts ranging from 1 to 7 mm.35 Posterior enhancement can be seen. When lined by apocrine metaplastic epithelia, the internal septi may be fuzzy (see Figs. 43 and 44), although the outer marginappears circumscribed. When associated with milk of calcium, dependent echogenic material can be seen (see Fig. 48). Individual microcysts can be complicated with fluid-debris levels or low-level echoes (see Fig. 44). The latter may be difficult to differentiate from a solid component. Associated simple and complicated cysts can be present. Spatial compounding may better depict the internal septa. Harmonics may help to prove individual microcysts are truly anechoic. With color Doppler, no flow is present.

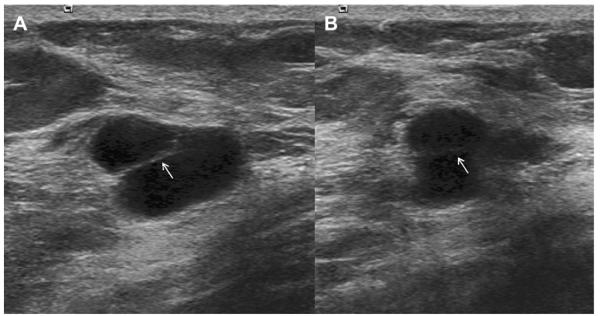

Fig. 49.

A 49-year-old woman had dense breasts and underwent screening ultrasonography demonstrating multiple bilateral simple and complicated cysts as well as this lesion of clustered microcysts on (A) transverse and (B) sagittal ultrasonographic images. Within 2 years, this mass had resolved on ultrasonography, and other clustered microcysts developed elsewhere over subsequent screening ultrasonographic examinations. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

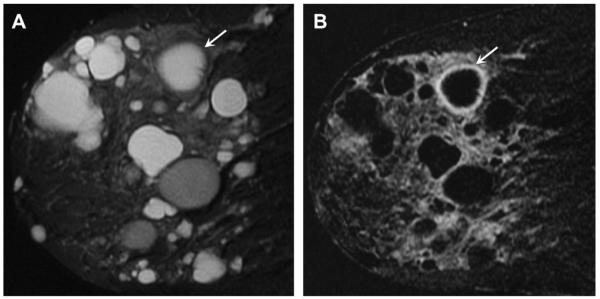

On T1-weighted MR images, clustered microcysts appear as oval or microlobulated masses that are iso- or hypointense to the parenchyma. The fluid components within clustered microcysts appear bright on T2W images (Fig. 50). Apocrine metaplastic change can enhance, although the cystic components do not.

Fig. 50.

A 54-year-old BRCA mutation carrier was referred for screening MR imaging. (A) On sagittal inversion recovery (STIR) MR imaging, hyperintense fluid-filled clustered microcysts with hypointense thin internal septations were incidentally noted. (B) Close-up. No enhancement was noted after contrast injection. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

Differential Diagnosis

Clustered microcysts are typically caused by fibrocystic change and can have milk of calcium. Individual acini can have apocrine metaplasia. Multiple, adjacent, tiny, simple cysts can mimic clustered microcysts.

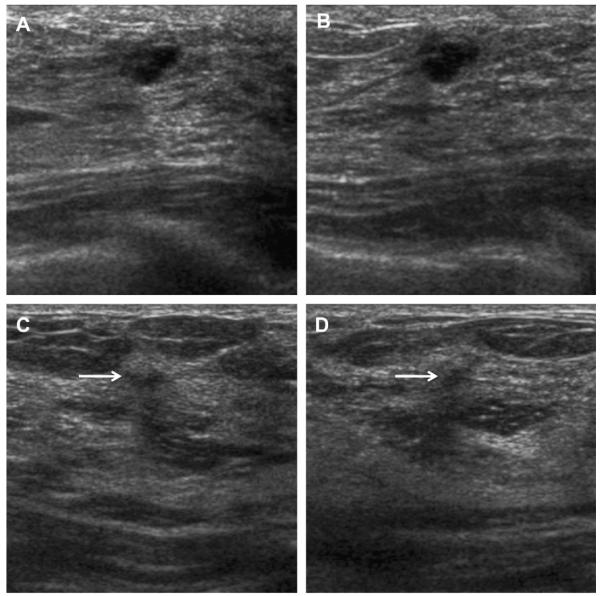

Apparent solid components in individual microcysts are most often debris, that is, complicated microcysts (see Fig. 44). Papillary apocrine metaplasia is a high-risk lesion and is more likely to have solid components. Of greater concern, complex cystic and solid masses, when small, can mimic benign clustered microcysts (Figs. 51 and 52), but complex masses are suspicious for malignancy as discussed later.

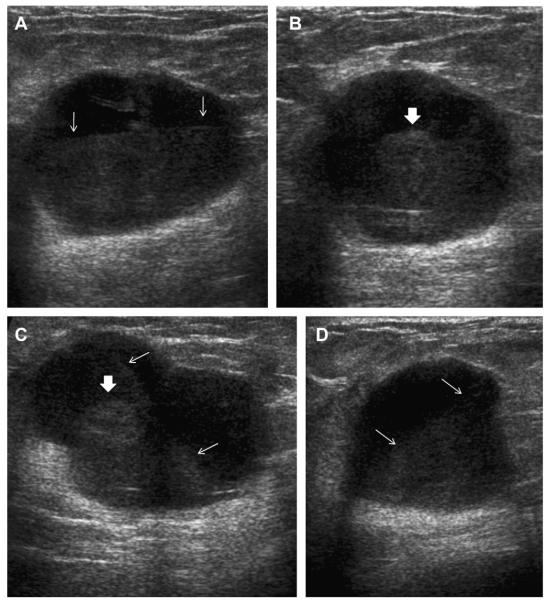

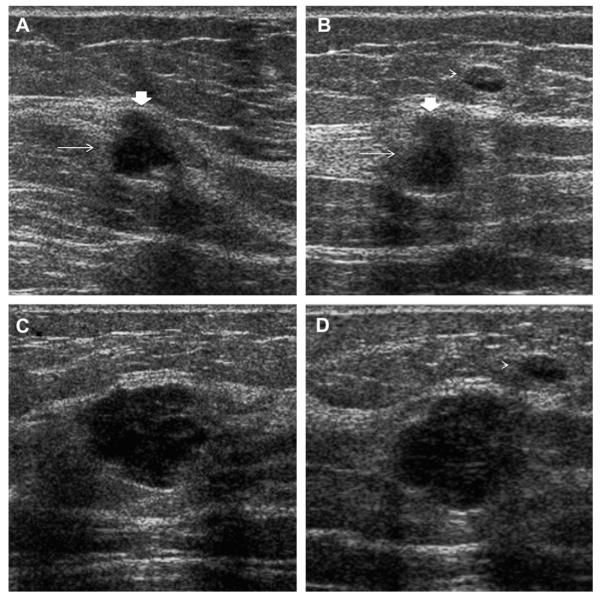

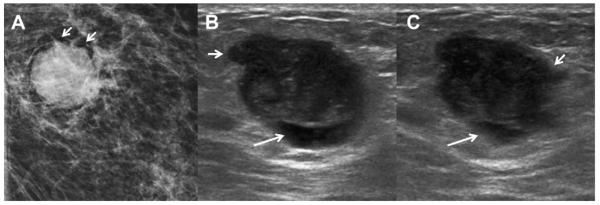

Fig. 51.

Ultrasonography was performed to evaluate multiple bilateral small nodules noted on screening mammography in a 58-year-old woman. Multiple cysts were noted. One nodule (A, radial and B, antiradial ultrasonography, thin arrows) was thought to be clustered microcysts but was recommended for a 6-month follow-up ultrasonography. An incidental adjacent complicated cyst with fluid-debris level was noted (arrowhead). At 6-month follow-up (C, radial and D, antiradial ultrasonography), the mass had enlarged. Biopsy was performed showing a 2-cm grade III IDC. The adjacent complicated cyst was stable (arrowhead). In retrospect, the mass is indistinctly marginated with probable solid component on the initial ultrasonographic images (A, B, short fat arrows). (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

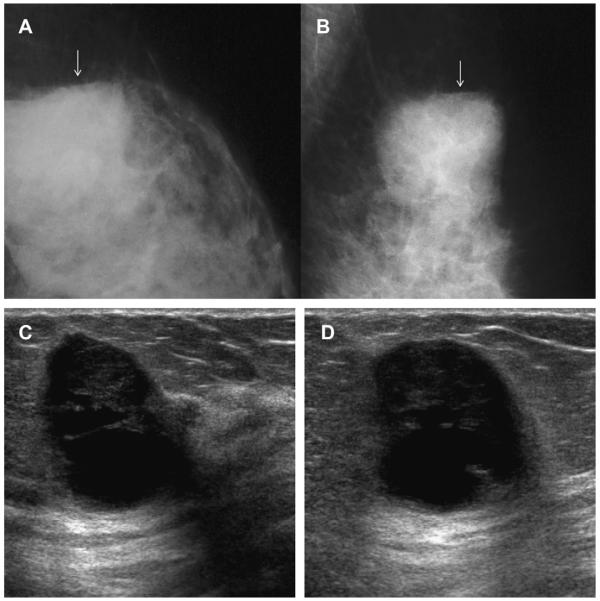

Fig. 52.

A 78-year-old woman was noted to have a new mass on screening mammography, as seen on (A)CC mammogram (arrow). (B) Targeted ultrasonography demonstrated what appeared to be clustered microcysts (arrow). The patient was not on hormonal therapy. Short-interval follow-up was recommended. At (C) 6-month follow-up ultrasonography, the mass seemed to have thick septations and indistinct margins. Biopsy was recommended, showing grade III IDC with associated high nuclear grade DCIS. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

Small microlobulated, predominantly solid, masses such as fibroadenomata, papillomas, phyllodes tumor (Fig. 53), DCIS, IDC, infiltrating lobular carcinomas, lactating adenomas, and tubular adenomas, rarely can be difficult to distinguish from clustered microcysts.

Fig. 53.

A 31-year-old woman had a mass in the right breast. On (A) radial and (B) antiradial ultrasonography, the mass appeared complex, cystic, and solid with many tiny cystic areas and numerous echogenic microcalcifications (arrowheads). Excision showed benign phyllodes tumor. (Courtesy of Dr Valérie Juhan, La Timone University Hospital, Marseille, France, via SuperSonic Imagine.)

Management

When the typical sonographic appearance is seen, clustered microcysts can be dismissed as benign, BI-RADS 2. When small or deep and difficult to adequately characterize, a probably benign assessment, BI-RADS 3, with 6-, 12-, and 24-month follow-up may be appropriate, using the imaging modality on which the lesion is best seen. Greater caution is appropriate with new clustered microcysts in a postmenopausal woman, particularly in the absence of hormone replacement therapy; with a typical appearance, a BI-RADS 3 assessment can be used in this setting. If the margins are not circumscribed, or if there are other suspicious features, a BI-RADS 4 assessment and biopsy may be appropriate.

Debris within microcysts can mimic a solid component. Provided there is no dominant solid component, and margins appear circumscribed, surveillance is reasonable. Biopsy should be performed (with BI-RADS 4 assessment) if the overall appearance is that of a complex cystic and solid mass (see Fig. 51), rapid growth has occurred (see Figs. 51 and 52), or any suspicious findings are present clinically or on any imaging (see Fig. 53).

COMPLEX CYSTIC AND SOLID MASSES

Complex cystic and solid masses are those with solid components such as a thick wall (≥0.5 mm), thick septations (≥0.5 mm), an intracystic mass, or solid masses with cystic areas. Such masses are uncommon but are suspicious for malignancy, BI-RADS 4, and merit biopsy. When malignant, the cystic portion can be due to areas of necrosis within a high-grade malignancy. As mentioned earlier, invasive cancers can mimic cysts or complicated cysts (see Figs. 7 and 30), although often slightly indistinct or angular margins or thickened walls are present (see Figs. 20 and 21; Fig. 54).15 High-grade cancers are typically rapidly enlarging and often palpable. With the high prevalence of benign cystic lesions, it can be especially difficult to recognize the few malignancies with such presentation, when they are nonpalpable incidental findings on imaging. Papillary DCIS can present as an intraductal or intracystic mass (see Figs. 27 and 28); it is difficult on imaging to exclude focal invasion.

Fig. 54.

A 74-year-old woman noted a lump in her left breast. (A) Spot compression mammogram demonstrated a mostly circumscribed dense mass. A portion of the margin appears lobulated (short arrows). Targeted (B) radial and (C) antiradial ultrasonography demonstrated a complex mostly solid mass with eccentric cystic area (arrows). The margins are focally angular (short arrows). Ultrasound-guided biopsy showed grade III IDC. (Courtesy of Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, Lutherville, MD.)

Across prior series, 97 (36%) of 270 complex cystic and solid lesions proved malignant (Table 6). In the ACRIN 6666 protocol, 19 (0.7%) of 2659 participants had such lesions on the initial screening, as did 42 (1.6%) of 2662 participants over the 3-year protocol, with 45 such lesions initially so classified, and no malignancies (see Table 4). These lesions were retrospectively reviewed. Only 20 (44%) of the 45 lesions were actually complex cystic lesions: 7 intracystic masses, 5 thick-walled cystic lesions, 3 mixed cystic and solid masses, 3 hypoechoic masses with tiny cystic areas, 1 intraductal mass, and 1 postsurgical collection. The other 25 were not complex cystic lesions: 10 complicated cysts (including 4 with fluid-debris levels), 4 clustered microcysts, 4 simple cysts with a single thin septation (see Figs. 10 and 13), 3 groups of simple cysts with intervening normal tissue, 2 simple cysts, and 1 each microlobulated anechoic mass and indistinctly marginated anechoic mass.

Table 6.

Summary of outcomes of sonographically complex cystic lesionsa

| Type of Lesion Author, Year |

Number | Number Malignant (%) | Details of Malignancies | Details of Benignity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intracystic Masses | ||||

| Omori et al,46 1993 | 21 | 10 (42) | Not detailed | 6 FCC, 3 papillomas, 2 abscesses |

| Berg et al,19 2003 | 18 | 4 (22) | 2 DCIS, 1 IDC, 1 IDC+DCIS | 5 papillomas, 3 FCC, 2 abscesses, 1 each galactocele, cyst, AM, and ruptured cyst |

| Tea et al,47 2009b | 19 | 4 (21) | Not detailedb | |

| Total of this subgroup | 58 | 18 (31) | ||

| Thick Walls with or without Thick Septations | ||||

| Berg et al,19 2003 | 23 | 7 (30) | 6 IDC, 1 IDC+DCIS | |

| Chang et al,21 2007c | 27 | 7 (26) | 5 high-grade IDC (1 medullary), 2 papillary carcinomas |

7 abscesses, 4 papillomas, 3 FCC, 3 cysts, 2 mucocelelike tumors, 1 fibroadenoma |

| Tea et al,47 2009b | 36b | 11 (31)b | Not specifically detailedb | |

| Total of this subgroup | 86 | 25 (29) | ||

| Complex Cystic and Solid Masses | ||||

| Omori et al,46 1993 | 35 | 14 (40) | Not detailed | 12 FCC, 3 FA, 2 papillomas, 2 abscesses, 1 ruptured epidermal inclusion cyst, 1 hemangioma |

| Berg et al,19 2003 | 38 | 7 (18) | 2 IDC, 2 IDC+DCIS, 1 each DCIS, ILC, and IDC+ILC+DCIS |

14 FCC, 11 FA, 2 AM, 1 each cyst, abscess, fat necrosis, and lactating adenoma |

| Chang et al,21 2007 | 53 | 33 (62) | 19 IDC, 5 malignant phyllodes, 4 metaplastic carcinoma, 2 DCIS, 2 mucinous carcinoma, 1 papillary carcinoma |

8 FA, 7 FCC, 2 abscesses, 2 papillomas, 1 phyllodes tumor |

| Total of this subgroup | 126 | 54 (43) | ||

| Overall Total | 270 | 97 (36) | ||

Abbreviations: AM, apocrine metaplasia; FA, fibroadenoma; FCC, fibrocystic change; ILC, invasive lobular carcinoma.

All such lesions were biopsied in the reported series.

In the report by Tea et al,47 masses with an intracystic solid mass may overlap with the group with wall thickness and/or septation. For wall thickness, 11 (31%) of 36 lesions were malignant compared with 7 (9.7%) of 72 lesions with septation not otherwise detailed and with some overlap of these categories not detailed: only wall-thickness group is included herein. Overall, 21 malignancies were identified among 151 complex cystic and solid masses, of which 8 (38%) were invasive, including 6 IDC, 1 ILC, and 1 invasive papillary carcinoma.

Includes lesions with mural masses (ie, intracystic masses).

Of the 2662 participants, 35 (1.2%) had masses described as hypoechoic with few tiny cystic areas (ie, predominantly solid with cystic components), and none of the 35 such lesions initially so classified proved malignant, although 1 lesion initially appearing as clustered microcysts was later described as hypoechoic with few tiny cystic areas and proved malignant (see Fig. 46).

Imaging Findings

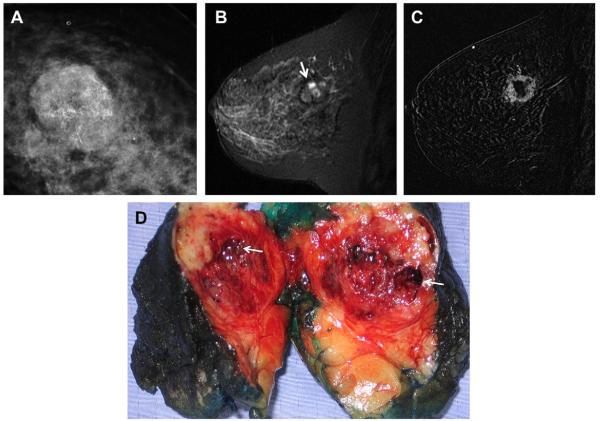

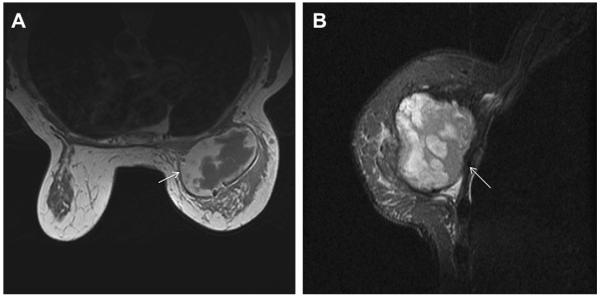

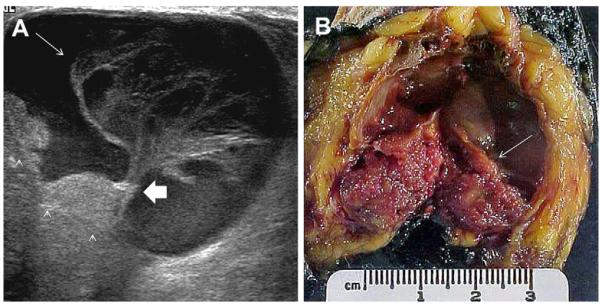

Mammographically, such lesions may have additional suspicious features such as indistinct margins, higher density than surrounding parenchyma, and associated suspicious calcifications. Amorphous calcifications can be seen in papillary lesions.