Abstract

Promoter binding by TraR and LuxR, the activators of two bacterial quorum-sensing systems, requires their cognate acyl-homoserine lactone (acyl-HSL) signals, but the role the signal plays in activating these transcription factors is not known. Soluble active TraR, when purified from cells grown with the acyl-HSL, contained bound signal and was solely in dimer form. However, genetic and cross-linking studies showed that TraR is almost exclusively in monomer form in cells grown without signal. Adding signal resulted in dimerization of the protein in a concentration-dependent manner. In the absence of signal, monomer TraR localized to the inner membrane while growth with the acyl-HSL resulted in the appearance of dimer TraR in the cytoplasmic compartment. Affinity chromatography indicated that the N-terminus of TraR from cells grown without signal is hidden. Analysis of heterodimers formed between TraR and its deletion mutants localized the dimerization domain to a region between residues 49 and 156. We conclude that binding signal drives dimerization of TraR and its release from membranes into the cytoplasm.

Keywords: acyl-homoserine lactone/Agrobacterium tumefaciens/quorum sensing/Ti plasmid/TraR dimerization

Introduction

Many bacteria regulate the expression of specific gene systems in response to the size of their population by a strategy called quorum sensing (reviewed in Fuqua et al., 1994). Such regulation requires at least three components: a transcription factor, a diffusible signal molecule called the autoinducer (AI) and a cis-acting recognition site located in the promoter region of the target gene. Most of the transcription factors are activators although at least one, EsaR from Pantoea stewartii, is a repressor (Beck von Bodman et al., 1998). Among Gram-negative bacteria, quorum sensing is often mediated by an acyl-homoserine lactone (acyl-HSL) signal molecule. As the paradigm of such systems, lux, the bioluminescence operon of Vibrio fischeri, requires the activator LuxR, a cis-acting inverted repeat called the lux box, and the acyl-HSL N-(3-oxo-hexanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone (3-oxo-C6-HSL) (reviewed in Sitnikov et al., 1995). The signal, which is produced by the bacteria, is membrane permeable and diffuses stochastically between the cellular and environmental compartments (Kaplan and Greenberg, 1985), thereby accumulating in the habitat as the size of the bacterial population increases. The bacteria monitor their population density by sensing the amount of AI present in the environment. The importance of this regulatory strategy is reinforced by the large number of bacteria that control gene expression by quorum sensing (Cha et al., 1998; Swift et al., 1999).

Conjugal transfer of the Ti plasmids of Agrobacterium tumefaciens is controlled in part by quorum sensing (Piper et al., 1993; Fuqua and Winans, 1996; Piper and Farrand, 2000). Expression of the three transfer operons, traAFB, traCDG and trb of pTiC58, is regulated by TraR, a LuxR-like activator (Piper et al., 1993) and N-(3-oxo-octanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone (3-oxo-C8-HSL) (Zhang et al., 1993). Like LuxR, activation of TraR requires that the signal accumulates to a threshold concentration within the environment. As a result, the expression of the Ti plasmid tra regulon is activated only when the donor population has reached a critical size (Piper and Farrand, 2000).

While AI is required for activation by LuxR and its homologs, how this signal modulates the activity of these transcription factors remains to be determined. Genetic and biochemical studies indicate that LuxR, TraR and CarR bind their cognate signals (Kaplan and Greenberg, 1985; Shadel et al., 1990; Adar and Ulitzur, 1993; Hanzelka et al., 1995; Zhu and Winans, 1999; Welch et al., 2000). Signal binding, in turn, is required by TraR and LuxR for interaction with their promoter recognition sites (Luo and Farrand, 1999; Egland and Greenberg, 2000). LuxR and its homologs are thought to be comprised of an N-terminal signal recognition region and a C-terminal DNA binding domain (reviewed in Fuqua et al., 1994). C-terminal deletion mutants of TraR and of LuxR exert strong dominant negativity over their wild-type counterparts (Choi and Greenberg, 1992; Luo and Farrand, 1999), suggesting that the two activators function as dimers or higher order homomultimers. These observations have yielded a model in which DNA binding and subsequent activation require multimerization, and that this process is dependent upon binding the acyl-HSL (reviewed in Fuqua et al., 1994). However, LuxRΔN, a 95-residue C-terminal fragment of LuxR, binds DNA and activates transcription of the lux operon in a signal-independent manner (Choi and Greenberg, 1991; Stevens et al., 1994). Significantly, LuxRΔN purifies as a monomer (Stevens et al., 1994). Thus, it is not clear whether signal binding is necessary for transcriptional activation or for some other activity of the protein.

TraR has been purified to homogeneity from cells grown with 3-oxo-C8-HSL (Zhu and Winans, 1999). The protein binds specifically to the 18 bp tra box recognition element and activates transcription from this promoter. Furthermore, the acyl-HSL is tightly bound to TraR with a stoichiometry of 1 mol of signal to 1 mol of protomer (Zhu and Winans, 1999). No other unmodified members of the LuxR family have been purified in a form that will activate transcription, making TraR an excellent model for the in vitro analysis of these transcription factors. However, functional TraR has not been purified from cells grown in the absence of AI, so the role of the signal remains to be determined. In this study we show that active TraR is a dimer and that the formation and stability of the dimer require bound AI. We localized the dimerization domain to the N-terminal half of TraR and present evidence suggesting that this region of the protein changes conformation when bound with ligand. We also show that in the absence of AI, monomer TraR predominantly associates with the cytoplasmic membrane and that upon interaction with the signal the protein appears as dimers in the cytoplasm. From these studies we present a model in which TraR in its inactive monomer form is compartmentalized such that the activator is poised to respond to signal present in the environment.

Results

Purified active TraR is a dimer containing 3-oxo-C8-HSL

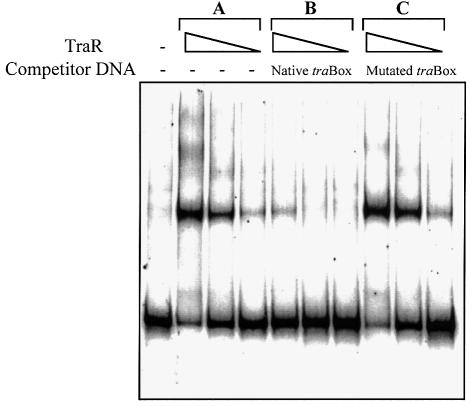

We purified TraR of pTiC58 from Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)(pLysS, pETR) grown in medium supplemented with 3-oxo-C8-HSL as described in Materials and methods. The protein is soluble and binds a DNA fragment containing the tra box element (Figure 1). The amount of probe DNA shifted increased with increasing amounts of the activator and no significant tertiary complexes were detected at any concentration of TraR tested. Formation of labeled DNA–protein complexes was strongly inhibited by excess unlabeled DNA containing the intact tra box (Figure 1). However, an unlabeled fragment containing symmetrical alterations at the 4th and 15th nucleotides of the tra box sequence failed to compete against the labeled probe (Figure 1). These substitution mutations within the tra box abolish TraR activity in vivo (Luo and Farrand, 1999).

Fig. 1. TraR specifically binds DNA containing the tra box. Purified TraR was incubated at 10-fold decreasing protein concentrations (35 to 0.35 ng) with 0.4 ng of a labeled 47 bp DNA fragment containing the tra box. Protein–DNA complexes were detected as described in Materials and methods. Gels contain TraR incubated with: (A) labeled probe only; (B) labeled probe and a 500-fold excess of unlabeled probe; (C) labeled probe and a 500-fold excess of unlabeled probe containing a tra box altered at positions 4 and 15.

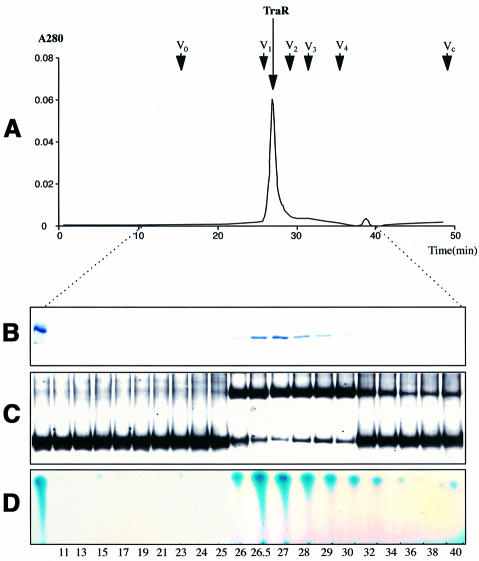

The purified protein eluted from an FPLC size exclusion column at a position corresponding to a molecular weight of 52 000, the expected size of the dimeric form of TraR (Figure 2A). No peaks corresponding to the monomeric form or to higher order multimers were detected. Analysis of the peak fractions by reducing SDS–PAGE yielded a single band with a size of 26 kDa, corresponding to the monomer form of the activator (Figure 2B). As judged by gel retardation assays, the protein in this peak binds DNA encoding the tra box (Figure 2C). A compound with the biological activity and the chromatographic properties of 3-oxo-C8-HSL was detectable by thin layer chromatography in fractions that contained TraR (Figure 2D).

Fig. 2. TraR isolated from cells grown with 3-oxo-C8-HSL is a dimer. Purified TraR (150 µg) was subjected to size-exclusion chromatography and fractions from the column were assayed for: (A) protein content (A280); (B) monomer protein size by SDS–PAGE; (C) interaction with the tra box by gel retardation; (D) presence of 3-oxo-C8-HSL by thin-layer chromatography, all as described in Materials and methods. Arrows indicate the elution times for a set of standard proteins (Sigma Chemical Co.) including V1, bovine serum albumin (Mr ∼66 000); V2, bovine erythrocyte carbonic anhydrase (Mr ∼29 000); V3, horse heart cytochrome c (Mr ∼12 400); and V4, bovine lung aprotinin (Mr ∼6500). V0 marks the elution time of blue dextran (Mr ∼2 000 000) and Vc denotes the column volume. The peak of absorbance labeled TraR eluted at a time interval corresponding to a protein of Mr ∼52 000.

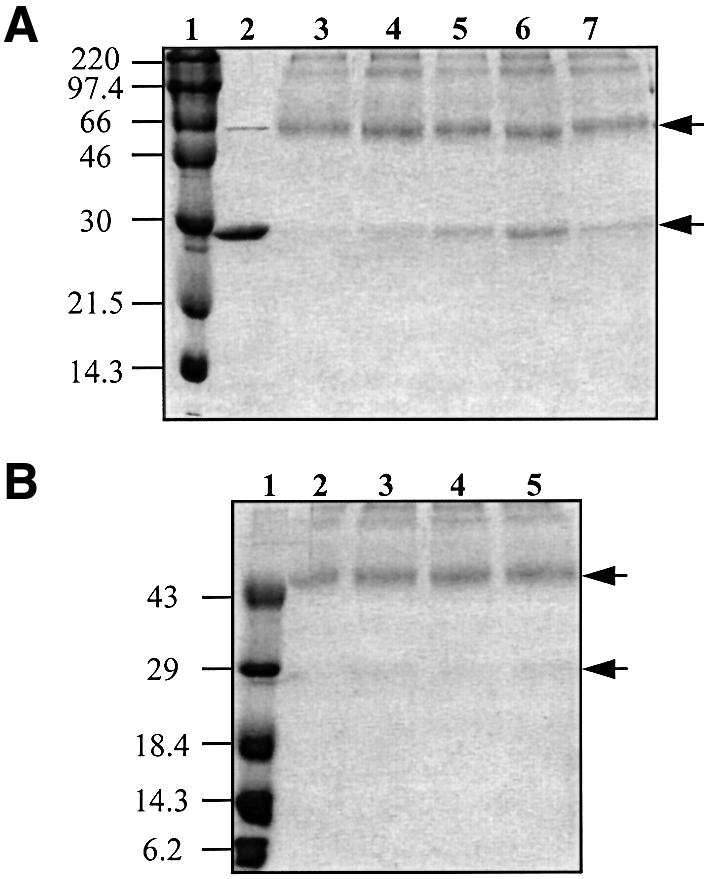

3-oxo-C8-HSL is bound very tightly to the active form of TraR; in previous studies prolonged dialysis was required to remove the ligand (Zhu and Winans, 1999). Of significance, as the ligand was removed the protein lost DNA binding activity. To determine whether the acyl-HSL is required to maintain TraR in the dimer form we dialyzed active TraR against two buffers, one with and the other without 3-oxo-C8-HSL. At 2-day intervals a volume was removed from each sample, treated with the cross-linker dithiobis(succinimidylpropionate) (DSP) and the protein was subjected to SDS–PAGE under non-reducing conditions. At zero time all of the detectable TraR was in the cross-linked dimer form in both samples (Figure 3). Following 2 days of dialysis against buffer lacking the ligand, detectable amounts of TraR appeared in the monomer form (Figure 3A), and after 6 days of dialysis a significant amount of the protein electrophoresed as monomers (Figure 3A). After 6 days a volume was removed from this sample, 3-oxo-C8-HSL was added and the sample was incubated for 2 h before treatment with DSP. Incubation with the acyl-HSL led to a decrease in the amount of monomer detectable in the sample (Figure 3A). However, TraR was not quantitatively converted back to the dimer form. The sample dialyzed against buffer containing the ligand did not detectably disassociate over the same time period (Figure 3B).

Fig. 3. TraR converts from dimer to monomer during dialysis in the absence of 3-oxo-C8-HSL. Purified dimer TraR (10 µM) was dialyzed against a buffer containing 50 mM HEPES pH 8.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 20% sucrose, 5% glycerol, 0.05% Tween 20 with (B) or without (A) 3-oxo-C8-HSL (10 µM final concentration). At 2-day intervals a volume was removed from each sample, the protein was treated with DSP and subjected to non-reducing SDS–PAGE as described in Materials and methods. (A) Lane 2 contains undialyzed, untreated TraR; lane 3 contains undialyzed, cross-linked TraR; and lanes 4, 5 and 6 contain TraR cross-linked following dialysis in the absence of 3-oxo-C8-HSL for 2, 4 or 6 days, respectively. Lane 7, TraR sampled from day 6 that had been re-incubated with 3-oxo-C8-HSL for 2 h prior to cross-linking. (B) Lane 2 contains undialyzed, cross-linked TraR, and lanes 3, 4 and 5 contain TraR cross-linked following dialysis in the presence of 3-oxo-C8-HSL for 2, 4 and 6 days, respectively. Lane 1 contains size standards (in kDa). The upper and lower arrows mark the locations of the dimer and monomer forms of TraR.

Inactive TraR is associated with the cytoplasmic membrane

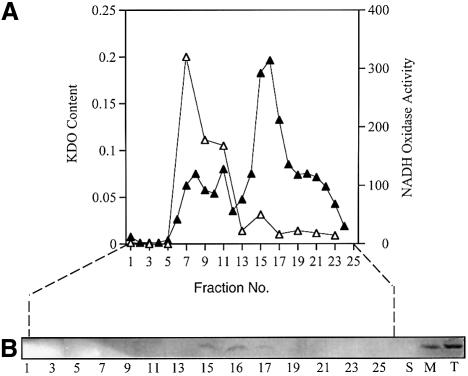

We have consistently noted that virtually all of the detectable TraR in cells of A.tumefaciens grown without signal sediments with the particulate fraction (data not shown). Given that LuxR is membrane associated (Kolibachuk and Greenberg, 1993), we determined the cellular location of TraR. Following growth in the absence of 3-oxo-C8-HSL all of the detectable TraR in A.tumefaciens NT1(pKKTR2) (which lacks a Ti plasmid) was located in the particulate fraction (Figure 4B). After separation into inner and outer membranes (Figure 4A), TraR localized exclusively to the inner membrane component (Figure 4B). We considered the possibility that aggregates of TraR formed from misfolded protein artificially co-purify with the particulate fraction. However, TraR was released from the inner membrane fraction by treatment with Tween 20 (1%) under conditions in which this detergent did not solubilize the membranes. TraR was also released by Triton X-100 (1%), which did solubilize the membranes, but not by 5 mM EDTA (data not shown). None of these treatments solubilized TraR in true inclusion bodies isolated from E.coli overexpressing the protein (data not shown). As expected, a significant portion of TraR was detected in the soluble fraction from cells grown with 3-oxo-C8-HSL (see below).

Fig. 4. TraR co-purifies with the inner membrane of A.tumefaciens. Membranes prepared from A.tumefaciens NT1(pKKTR2) grown in the absence of signal were fractionated into inner and outer components on a sucrose gradient as described in Materials and methods. Fractions were assayed for NADH oxidase activity (µmol NAD formed/min/ml, filled triangles) and 2-keto 3-deoxyoctanoate (KDO) content (mg/ml, open triangles) (A), and for TraR by western blot analysis (B) as described in Materials and methods. T, M and S represent equal loadings of proteins from the total lysate, the total membrane fraction and the soluble fraction, respectively.

3-oxo-C8-HSL is required for TraR to form dimers in vivo

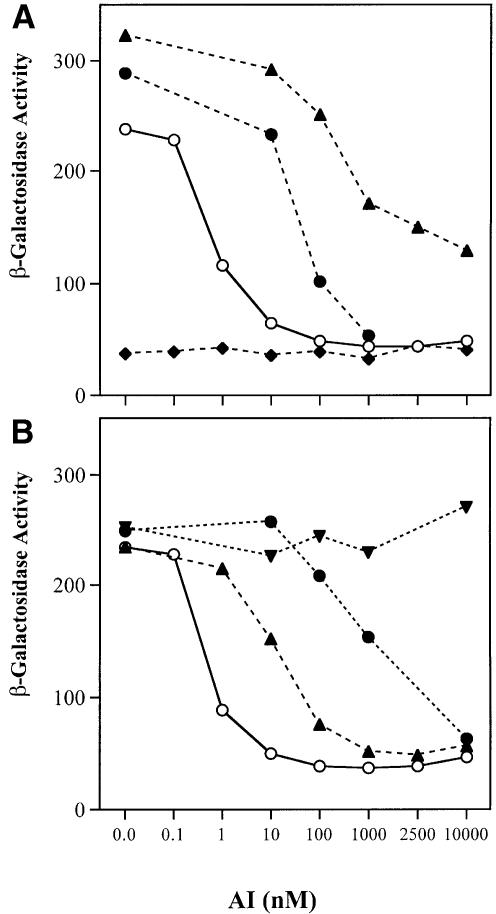

Biologically active TraR has not been isolated from cells grown without 3-oxo-C8-HSL, therefore we have not been able to assess biochemically the role of the signal in the activation of TraR. As an alternative, we used a genetic system based on the cI repressor of phage λ to determine if dimerization of TraR requires the acyl-HSL. In the assay, the protein of interest is fused to cI′, the N-terminal DNA binding domain of the repressor (Hu, 1995). cI′ alone fails to bind DNA because it lacks the dimerization domain located in the C-terminal portion of the full-size repressor. If the protein being tested multimerizes, the hybrid protein can regain operator binding activity as signified by repression of a λ PR::lacZ reporter (Hu, 1995). Such fusions between cI′ and full-size TraR repressed the reporter, but repression was dependent on growth with 3-oxo-C8-HSL (Table I). Furthermore, the degree of repression depended on the amount of ligand provided to the bacteria (Figure 5A). The range of concentrations of the signal required for repression by the cI′::TraR fusion protein is similar to that required by native TraR to activate expression of the tra and trb operons in A.tumefaciens (Zhang et al., 1993; Hwang et al., 1994). The cI′::LeuZip–GCN4 fusion protein, which contains the multimerization domain of the yeast activator GCN4 (Hu et al., 1990), strongly repressed the reporter, but, as expected, it did so in an acyl-HSL-independent manner (Table I). cI′ fusions to TraR from the octopine-type Ti plasmid pTi15955 or LuxR from V.fischeri also repressed the reporter, but only when the cells were grown with the cognate acyl-HSL (Table I; Figure 5A). TraR responds to non-cognate ligands but requires greater quantities of the alternative signal (Zhang et al., 1993; Shaw et al., 1997; Zhu et al., 1998). cI′::TraR repressed the reporter when the cells were grown with 3-oxo-C6-HSL, or with N-octanoyl-HSL (C8-HSL), but much higher amounts of these acyl-HSLs were required to produce levels of repression comparable to those observed in cells grown with 3-oxo-C8-HSL (Figure 5B). cI′::TraR did not repress the reporter in response to N-hexanoyl-HSL (C6-HSL), even at high concentrations (Figure 5B). However, wild-type TraR responds very poorly to this alkanoyl acyl-HSL (Cha et al., 1998; Zhu et al., 1998). Interestingly, fusions between cI′ and EsaR, a LuxR homolog from P.stewartii (Beck von Bodman and Farrand, 1995), repressed the reporter even in the absence of the cognate signal, 3-oxo-C6-HSL (Table I; Figure 5A). Moreover, adding the acyl-HSL had no effect on repression by cI′::EsaR.

Table I. Dimerization of TraR and LuxR λ cI′ fusion proteins requires acyl-HSL.

| Plasmida | cI′ fusion | Expression of λ PR::lacZb |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| –AI |

+AIc |

||||

| β-gal activity | Fold repressiond | β-gal activity | Fold repressiond | ||

| pJH391 | none | 235 | – | 272 | – |

| pJH370 | LeuZip-GCN4 | 23 | 10 | 24 | 11 |

| pAJS100 | TraRpTiC58 | 238 | none | 44 | 6 |

| pAJS150 | TraRpTi15955 | 289 | none | 54 | 5 |

| pAJS200 | LuxR | 323 | none | 130 | 2.1 |

| pAJS300 | EsaR | 37 | 6 | 39 | 7 |

aAll constructs were tested in E.coli JH372 (Hu et al., 1990).

bβ-galactosidase activity is expressed per 108 c.f.u. as described in Materials and methods.

cStrains harboring pJH391, pJH370, pAJS100 and pAJS150 were grown with 1 µM 3-oxo-C8-HSL. Strains harboring pAJS200 and pAJS300 were grown with 10 µM 3-oxo-C6-HSL.

dCalculated relative to the level of β-galactosidase activity in JH372(pJH391).

Fig. 5. Dimerization of λ cI′ fusions to TraR or LuxR is dependent upon acyl-HSL. Cultures of E.coli JH372, harboring plasmids coding for cI′ fusion proteins were grown for 6 h in L broth with the appropriate acyl-HSL at the indicated concentration. Samples were assayed for β-galactosidase activity as described in Materials and methods. (A) Repression by cI′ fusions to TraR and LuxR but not to EsaR is dependent upon the acyl-HSL concentration. Fusions of cI′ to: TraRpTiC58 (open circles) and TraRpTi15955 (filled circles), both incubated with 3-oxo-C8-HSL, and LuxR (filled triangles) and EsaR (filled diamonds), both incubated with 3-oxo-C6-HSL. (B) Repression by the cI′::TraR fusion is dependent upon the structure of the acyl-HSL. Fusions of cI′ to TraRpTiC58 incubated with: 3-oxo-C8-HSL (open circles), 3-oxo-C6-HSL (filled triangles), C8-HSL (filled circles) and C6-HSL (filled inverted triangles).

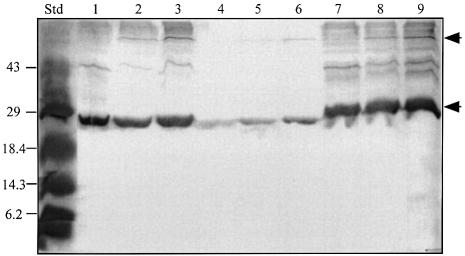

We also examined the oligomeric state of TraR in vivo by chemical cross-linking. In these studies A.tumefaciens NT1(pZLQR) was grown with or without 3-oxo-C8-HSL. The cells were harvested, treated with DSP, which is membrane permeable, lysed, and the location and multimeric state of the activator protein were determined by far western blot analysis. In cells grown without signal, most of the detectable TraR was located in the particulate fraction, although a small amount was detected in the soluble fraction (Figure 6). Furthermore, the TraR present in both fractions was solely in the monomer form. In cells grown with 3-oxo-C8-HSL, TraR was detectable in both fractions (Figure 6). Moreover, while much of the protein electrophoresed as monomers, the dimer form was easily detected in both the soluble and particulate fractions. Significantly, the amount of dimer detectable in both fractions increased with increasing amounts of signal to which the cells were exposed. The additional reactive bands present in the total and particulate fractions from cells grown with or without the acyl-HSL may represent TraR cross-linked to other membrane proteins. Whether such interactions are gratuitous or of biological significance remains to be determined. We conclude from these results that in the absence of 3-oxo-C8-HSL TraR is predominantly, if not exclusively in monomer form and is associated with the cytoplasmic membrane of the bacterium. Upon exposure to the signal, TraR dimerizes and a proportion, if not most of these dimers localize to the cytoplasmic compartment.

Fig. 6. 3-oxo-C8-HSL drives dimerization of TraR and its appearance in the cytoplasm. Agrobacterium tumefaciens NT1(pZLQR) was grown in ABM medium to late exponential phase, harvested cells were treated with DSP, broken in the French press, and the lysates (lanes 1–3) were separated into soluble (lanes 4–6) and particulate (lanes 7–9) fractions as described in Materials and methods. Equal amounts of protein of each of the fractions were subjected to SDS–PAGE under non-reducing conditions, and TraR was visualized by far western blot analysis (Luo et al., 2000). Cultures were grown with no ligand (lanes 1, 4 and 7) or with 50 nM (lanes 2, 5 and 8) or 100 nM (lanes 3, 6 and 9) 3-oxo-C8-HSL. The upper and lower arrows mark the locations of the dimer and monomer forms of TraR.

The N-terminus of unactivated TraR is occluded

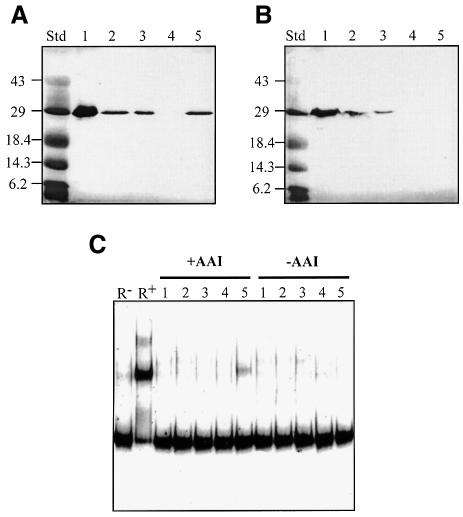

Our results are consistent with a model in which AI binding results in a change in the structure of TraR, allowing the protein to dimerize. An N-terminal His6-tagged derivative of TraR retains biological activity, activating expression of a traG::lacZ reporter fusion to a level ∼70% that of wild-type TraR expressed from the same vector (Hwang et al., 1999 and data not shown). Moreover, activation by the His-tagged TraR remains dependent upon 3-oxo-C8-HSL. Like wild-type TraR, when expressed in A.tumefaciens cultured without signal most of the protein is located in the particulate fraction, while a very small amount can be detected in the soluble fraction (Figure 7B). When loaded on a nickel affinity column, this soluble His-tagged TraR is not retained, but can be detected in the column flow-through (Figure 7B). Addition of 3-oxo-C8-HSL to the lysate prior to loading the column had no effect on the affinity of the protein for the column (data not shown). On the other hand, a large proportion of His6-TraR isolated from cells grown with signal was detected in the soluble fraction and was retained by the affinity column (Figure 7A). Furthermore, this affinity-purified His6-TraR contained 3-oxo-C8-HSL (data not shown) and bound a DNA probe containing the tra box (Figure 7C). In contrast, the His6-TraR in the column flow-through of the lysate from cells grown without signal did not detectably bind the DNA probe (Figure 7C).

Fig. 7. N-terminal His-tagged TraR from cells grown in the absence of 3-oxo-C8-HSL fails to bind to nickel affinity resin. Cultures of A.tumefaciens NT1(pKKHTR9) were grown in ABM with (A) or without (B) 3-oxo-C8-HSL (100 nM). The cells were harvested and lysates were prepared and subjected to nickel affinity chromatography. Equal volumes of samples from each treatment were electrophoresed and TraR was visualized by far western blot analysis (A and B). Samples were also assayed for DNA binding by gel retardation (C), all as described in Materials and methods. Lane 1, total lysate; lane 2, cleared lysate; lane 3, column flow-through; lane 4, 10 mM imidazole wash; lane 5, 100 mM EDTA eluate. R– and R+ in (C) contain the labeled probe DNA without or with pure native TraR, respectively.

A dimerization domain of TraR is located in the N-terminal half of the protein

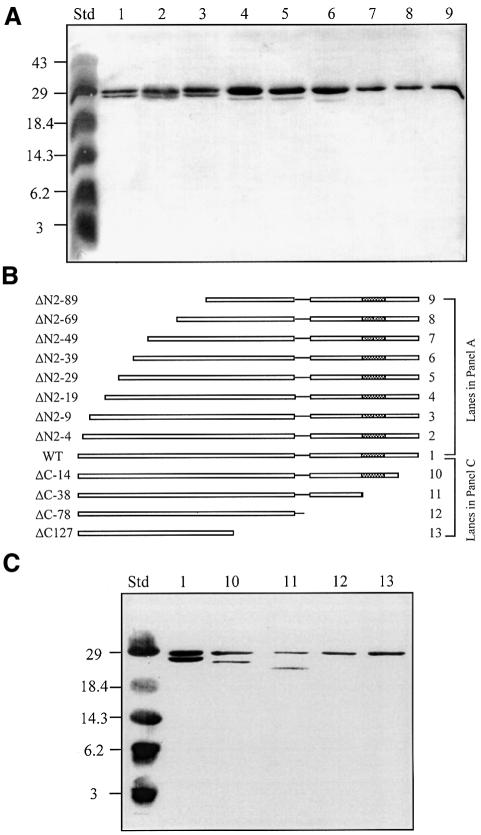

We used an affinity chromatography strategy that assesses the ability of two proteins of different sizes to form heterodimers in vivo to localize the region of TraR required for dimerization. When wild-type and full-size His6-TraR were co-expressed in cells grown with 3-oxo-C8-HSL, both proteins were retained in large amounts on the nickel affinity column (Figure 8). Binding and co-elution of the two proteins are due to the formation of heterodimers of wild-type- and His6-TraR; the activator expressed from cells containing only the wild-type gene was not bound by these columns (data not shown). Moreover, when lysates from cultures independently expressing wild-type and His6-TraR were mixed prior to loading, only the His-tagged form of the protein was retained on the column (data not shown).

Fig. 8. The dimerization region of TraR is located in the N-terminal half of the protein. Wild-type TraR or its N- or C-terminal deletion mutants were co-expressed with His6-TraR in A.tumefaciens NT1 grown with 100 nM 3-oxo-C8-HSL. Cleared lysates were prepared, subjected to nickel affinity chromatography, and the protein eluted from the resin was analyzed by SDS–PAGE as described in Materials and methods. Heterodimers of His6-TraR and N-terminal deletion mutants (A) were detected by far western blot analysis while heterodimers of His6-TraR and C-terminal deletion mutants (C) were detected by western analysis as described in Materials and methods. The alleles of TraR along with representations of their structures are presented in (B). Std, a mixture of standard markers with sizes in kilodaltons noted to the left of the blots.

Co-expressing His6-TraR with mutants of the activator deleted for up to nine N-terminal amino acids had little effect on the formation of heterodimers (Figure 8A). However, while the amount of eluted His6-TraR remained constant, deleting between 19 and 39 N-terminal residues decreased the amount of the deletion protein recoverable as heterodimers. Mutants of the activator deleted for 49 or more N-terminal residues did not form detectable amounts of heterodimers (Figure 8A). Mutants of the activator missing from 14 to 38 C-terminal amino acids yielded heterodimers equivalent in amount to those formed between the His-tagged and the wild-type proteins (Figure 8B). Removing 78 or more C-terminal residues resulted in the absence of detectable heterodimers. In all cases the N- and C-terminal deletion proteins were produced at levels equal to or greater than that of His6-TraR as assessed by western or far western blot analyses prior to affinity chromatography (data not shown).

Discussion

We conclude from these studies that interactions between TraR and its acyl-HSL signal result in the formation of stable homodimers of the protein. Clearly, active TraR purifies as a dimer and this dimer contains 3-oxo-C8-HSL. Moreover, upon removal of the ligand the dimer disassociates (Figure 3) and loses biological activity (Zhu and Winans, 1999). Furthermore, results from the λ cI′ fusions, and from in vivo cross-linking studies indicate that in the absence of the acyl-HSL, TraR exists predominantly in monomer form. Addition of the signal results in the formation of dimers in vivo, an observation that is consistent with the form of the active protein purified from cells grown with signal. Based on the cI′ fusion studies, LuxR behaves in a similar manner. The activator does not detectably multimerize in the absence of 3-oxo-C6-HSL, but forms dimers when the cells are grown with the signal. These results stand in contrast to those of Welch et al. (2000) in a study of CarR, a LuxR homolog that regulates expression of genes involved in virulence of the plant pathogen, Erwinia carotovora. Unlike TraR, a portion of CarR purified from cells grown without the acyl-HSL renatured into dimers. Moreover, addition of the signal to a preparation of pure protein did not increase the amount of the dimer form, but resulted in the aggregation of CarR into high molecular weight complexes. In this regard, CarR may resemble EsaR. This member of the LuxR family regulates expression of genes required for capsular polysaccharide synthesis in P.stewartii, a close relative of E.carotovora (Beck von Bodman and Farrand, 1995). As judged by analysis of cI′::EsaR fusions, this protein forms dimers in the absence of its cognate acyl-HSL. Interestingly, EsaR strongly represses gene expression in the absence of signal (Beck von Bodman et al., 1998), suggesting that the acyl-HSL is not required for promoter binding by this transcription factor. Since most prokaryotic repressors bind DNA only as dimers or higher order homomultimers (reviewed in Ptashne, 1986), the capacity to multimerize in the absence of the acyl-HSL is consistent with the negative regulatory properties of EsaR. EsaR, in any form, is not required for transcription; the target genes are expressed constitutively in an esaR-null mutant (Beck von Bodman et al., 1998). However, the cognate acyl-HSL is required for derepression, suggesting that the signal alters the interaction between EsaR and its target promoters. How ligand binding relieves repression by EsaR remains to be determined. CarR is more closely related to EsaR than it is to TraR or to LuxR (data not shown). Given that CarR and EsaR dimerize and bind promoters in the absence of signal, it is possible that the phylogenetic relationships reflect a difference in how these transcription factors interact with signal and, in turn, regulate their target genes.

The differences between TraR and CarR extend to how these two proteins interact with their promoters. In vivo, neither TraR nor LuxR binds its DNA recognition site in the absence of its ligand (Luo and Farrand, 1999; Egland and Greenberg, 2000). Consistent with these analyses, soluble His6-TraR from cells grown without signal did not detectably bind DNA (Figure 7C), while the ligand-bound dimer form of TraR, either wild-type or His-tagged, binds DNA (Figures 2C and 7C). Furthermore, binding is specific, with a strict requirement for the tra box, and produces a single, well defined protein–DNA complex even at high protein concentration (Figure 1). CarR, on the other hand, when purified from cells grown without signal, bound promoter DNA, forming increasingly larger complexes as the amount of protein was increased (Welch et al., 2000). Addition of the ligand modified the binding pattern, but large complexes of DNA and CarR protein were still formed. The results are clear; TraR and probably LuxR require their ligands to bind DNA while CarR, and most probably EsaR can bind DNA even in the absence of signal. Moreover, as judged by the patterns of fragment retardation, TraR and CarR form different types of complexes with their target promoters. Consistent with this conclusion, CarR activates transcription independently of signal when the protein is overexpressed (McGowan et al., 1995). Such is not the case for TraR, emphasizing further the differences between these two quorum-sensing activators.

Analysis of heterodimers formed between N- and C-terminal deletion mutants and His6-TraR indicates that a portion of the activator spanning residues 49–156 is required for dimerization. This region corresponds with a segment of LuxR that, based on genetic analysis, is thought to be associated with multimerization (Choi and Greenberg, 1992). This region of LuxR is also required for binding 3-oxo-C6-HSL (Hanzelka and Greenberg, 1995; Schaefer et al., 1996a). From our data we cannot differentiate between effects of the deletions in TraR on signal binding versus dimerization per se.

The changes in structure of TraR that allow dimerization concomitant with signal binding are not known. However, our observation that monomeric His6-TraR does not bind to a nickel affinity column suggests that without ligand, the N-terminus of the protein is hidden from the aqueous environment. Such is not the case for TraR bound with its acyl-HSL; in this state the His-tagged protein binds to the nickel column, indicating that the N-terminus is exposed. These observations are consistent with those of Welch et al. (2000), showing that the structure of CarR changes upon ligand binding. We propose that such a structural alteration in TraR favors a shift in the equilibrium towards dimer formation. This may occur, for example, by forcing a conformational change that results in the unmasking of a domain required for dimerization. This hypothesis is consistent with the ligand-dependent availability of the N-terminal portion of the protein, the region that contains the dimerization domain. An acyl-HSL-induced alteration at the N-terminus is also consistent with the observation that this region of the protein is required for transcriptional activation (Luo and Farrand, 1999). Perhaps a conformational change attendant to signal binding and concomitant dimerization is required to allow this region of the molecule access to RNA polymerase.

Like LuxR, inactive TraR is associated with the cytoplasmic membrane in A.tumefaciens. Solubility studies using mild, non-ionic detergents suggest that this association is not an artifact of the expression system or the isolation procedure. Consistent with this interpretation, the location of TraR depends on the presence of the acyl-HSL signal. While almost all of the activator co-purifies with the membrane in cells grown without 3-oxo-C8-HSL, when grown with the signal, a significant portion of TraR locates to the cytoplasm. In this regard, TraR differs from LuxR; all of the detectable LuxR locates to the membrane irrespective of the presence of ligand (Kolibachuk and Greenberg, 1993). Moreover, TraR present in the soluble fraction is virtually all in dimer form, while the majority of TraR remaining in the membrane fraction is monomeric. This observation suggests that whatever the effect on structure, binding the acyl-HSL results in the partitioning of the protein from the membrane to the cytoplasm. Furthermore, this partitioning coincides with dimerization. Like LuxR, TraR lacks identifiable membrane-spanning motifs. The absence of such regions suggests that some segment of TraR exposed in cells grown without the acyl-HSL has an affinity for membranes. Hydropathy profiles indicate that a region of TraR from residues 110 to 160 is strongly hydrophobic (data not shown). This region comprises a segment of the domain of TraR required for dimerization. We speculate that in the absence of the acyl-HSL this region is surface exposed, and because of its hydrophobicity associates with the lipid bilayer of the cytoplasmic membrane. Presumably, interaction with the AI alters the conformation of the protein such that this region becomes buried, or more likely is masked by participating directly in the formation of dimers.

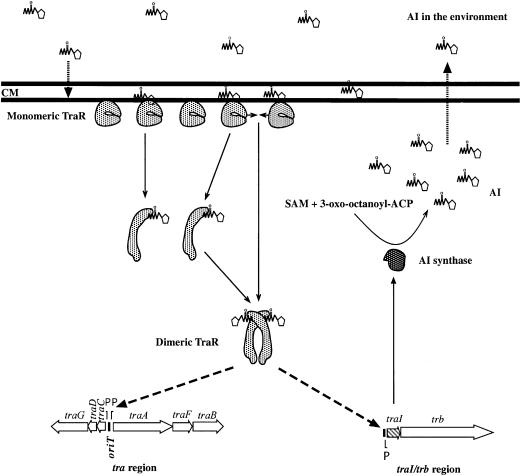

A membrane location for inactive TraR predicts a model that could answer some vexing paradoxes. According to the current model, the acyl-HSLs exchange freely between the intra- and extracellular compartments. Moreover, in the absence of other considerations, since the signal is produced enzymatically within the cell, the intracellular concentration will always be higher than that of the exterior. However, Kaplan and Greenberg (1985) estimated that as few as two molecules of 3-oxo-C6-HSL per cell are sufficient to activate LuxR. It is hard to imagine, given its enzymatic origin (Schaefer et al., 1996b), that fewer than two molecules of the acyl-HSL are present in each cell during growth of the bacterium. It seems probable that TraR and the other activators of the LuxR family must be compartmentalized away from newly synthesized signal. This notion is consistent with the results of Kaplan and Greenberg (1985). They derived their estimates from luxI– cells incubated with exogenous radiolabeled 3-oxo-C6-HSL. Thus, the only signal to which these cells were exposed came from the exterior. The need to protect the activator from nascent intracellular signal is also consistent with the observation that Pseudomonas aeruginosa exports one of its acyl-HSLs via an efflux pump (Pearson et al., 1999). We propose a model in which TraR, LuxR and perhaps other members of this family associate with the inner face of the cytoplasmic membrane (Figure 9). This compartmentalization shields the activator or its AI binding domain from nascent signal present in the intracellular compartment. However, as the externalized signal diffuses back into the membrane it is free to interact with its binding site on TraR, which also is associated with the membrane. In this manner, TraR is poised to interact with signal re-entering the cell. In this regard the model is consistent with a proposal by Welch et al. (2000) that the membrane solubility properties of the acyl-HSLs can, in part, dictate ligand-receptor specificity. Upon binding the signal, TraR dimerizes and partitions to the cytoplasmic compartment where it can interact with its target promoters. Inherent to the model is the notion that it is the extracellular form of the signal that determines the quorum and also contributes to the cell-to-cell communication properties of this gene regulatory system.

Fig. 9. Model for the compartmentalization of TraR from intracellular 3-oxo-C8-HSL. Unactivated TraR is associated as monomers with the inner face of the cytoplasmic membrane (CM) where it is shielded from nascent acyl-HSL produced by TraI (Moré et al., 1996) within the cell. The newly synthesized signal passes out through the membrane where it can accumulate in the environment. This extracellular signal diffuses back into the membrane where, when at sufficiently high concentrations, it can interact with its binding site on TraR. Signal binding, at a stoichiometry of 1:1 (Zhu and Winans, 1999), alters some property of TraR, thereby allowing the activator to dimerize and to release from the membrane into the cytoplasm. Alternatively, after binding one molecule of signal, protomers of TraR release from the membrane and dimerize in the cytoplasm. In its soluble dimer form TraR binds to tra box sites located in promoters of the tra regulon and, in conjunction with RNA polymerase, activates transcription.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains, culture conditions and constructions

Agrobacterium tumefaciens NT1, a Ti plasmid-cured derivative of C58 (Watson et al., 1975) was grown in L broth, in MG/L medium (Cangelosi et al., 1991) or in ABM minimal medium (Chilton et al., 1974) at 28°C. Acyl-HSLs, synthesized as previously described (Shaw et al., 1997), were included in media at concentrations as indicated in the text. Escherichia coli strains were grown at 37°C on L agar plates or in L broth. pZLQR and pKKTR2, both of which express wild-type TraR, have been described (Luo and Farrand, 1999; Luo et al., 2000). pKKHTR9, which expresses His6-TraR, was constructed by cloning full-size traR, preceded by the pET14b-encoded His6-tag sequence, behind the trc promoter of pKK38 (Oger et al., 1998). Fusions of TraR from pTiC58 and pTi15955, and of LuxR and EsaR, to the N-terminus of λ cI repressor were constructed by cloning the appropriate genes as PCR products into pJH391. This plasmid contains the first 396 bp of the cI gene expressed from the lac promoter (Dang et al., 1999). Primers, templates and cloning strategies used for these constructs are available on request. Correct translational fusions between the two proteins were confirmed by DNA sequence analysis. The repressor activities of these constructs were assayed in E.coli JH372, a derivative of MC1061 lysogenized with λ202 that contains a PR::lacZ reporter (Hu et al., 1990). The construction and properties of the 5′ and 3′ deletion derivatives of traR were described previously (Luo and Farrand, 1999).

Enzyme assays

β-galactosidase activity, expressed per 108 colony forming units (c.f.u.), was determined as described previously (Farrand et al., 1996). Samples were assayed in triplicate and each experiment was repeated at least once.

Purification of TraR

Native active TraR was purified from E.coli BL21(DE3)(pLysS, pETR) as described by Luo et al. (2000). His6-TraR expressed in A.tumefaciens NT1(pKKHTR9) grown with or without 3-oxo-C8-HSL was subjected to chromatography on nickel affinity columns as follows: cleared lysates (5 ml) were mixed for 2 h at 4°C with a 1 ml slurry of nickel affinity resin (Qiagen) equilibrated with TDGT buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.9, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 5% glycerol and 0.05% Tween 20] containing 1 mM imidazole. The resin was loaded on a column and washed with three 5-ml volumes of the same buffer containing 1 mM and then 10 mM imidazole. The bound protein was eluted with 2 ml of the same buffer containing 100 mM EDTA. Protein concentrations were determined as described previously (Luo et al., 2000).

Gel filtration chromatography

Purified TraR [150 µg in 100 µl of TEDGT buffer (Luo et al., 2000)] was chromatographed on Superose 12HR 10/30 using a Pharmacia FPLC apparatus. The column was developed with 25 ml of TEDGT buffer containing 2 nM 3-oxo-C8-HSL at an elution rate of 0.5 ml per minute. The column was calibrated using a kit containing a set of standard proteins from Sigma (St Louis, MO).

Gel retardation assays

Gel retardation assays were conducted as described previously (Luo et al., 2000). A 47 bp probe containing the intact tra box was prepared by annealing two oligonucleotides (sequence available on request) obtained from the Keck Center at the University of Illinois. A second 47 bp probe, in which the 4th and 15th nucleotides of the tra box were altered, was prepared in a similar fashion. The two modifications altered the sequence but retained the symmetry of the tra box by changing the T at position 4 to C, and the A at position 15 to G (Luo and Farrand, 1999). Probes were labeled with digoxigenin-11-ddUTP and terminal transferase as described by the supplier (Roche Molecular Biochemicals).

Detection of acyl-HSLs

Two-microliter volumes of samples to be tested were chromatographed on C18 reversed-phase thin-layer plates using methanol:water (60:40 v/v). The acyl-HSLs were detected by overlaying the developed plates with the bioindicator strain NT1(pZLR4) in soft ABM agar containing X-Gal as described previously (Shaw et al., 1997).

Cell fractionation

Cells were grown in 500 ml volumes of MG/L medium to late exponential phase, harvested and washed with double-distilled water. The cell pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of a buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.5, 20% sucrose and 0.2 mM DTT containing DNase (10 U/ml) and RNase (0.2 mg/ml), and the cells were broken by passage three times through a pre-chilled French press at 1400 kg per cm2 at 4°C. Lysozyme (0.2 mg/ml) was added and the suspension was incubated for 30 min at 4°C. Two volumes (20 ml) of 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.5 were added and unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 2800 r.p.m. for 20 min at 4°C in a Sorvall SS34 rotor. The supernatant was adjusted to 0.2 M KCl and fractionated into soluble and particulate components by centrifugation at 262 000 g for 2 h at 4°C in a Beckman Ti 60 rotor. The membrane fraction was resuspended in 1 ml of buffer and separated into inner and outer membrane components by centrifugation on a 25–60% discontinuous sucrose gradient in a Beckman SW41 rotor at 68 000 g for 16 h as described by de Maagd and Lugtenberg (1986). Fractions were collected and assayed for KDO, a marker for outer membranes (Keleti et al., 1974), and for NADH oxidase activity, a marker for inner membranes (Kolibachuk and Greenberg, 1993).

Solubilization of TraR

Inner membrane fractions containing TraR were resuspended in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.9, 150 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol and 0.2 mM DTT. Samples were treated with Tween 20 (1% final concentration), Triton X-100 (1% final concentration) or EDTA (5 mM final concentration) for 1.5 h at 4°C. Following these treatments, the samples were separated into soluble and particulate fractions by centrifugation at 10 000 g for 1 h at 4°C.

Chemical cross-linking

The membrane-permeable homo-bifunctional cross-linker DSP (2.7 mM final concentration) was added to a solution containing 26 µg (1 nmol) of purified TraR in 100 µl of a buffer containing 50 mM HEPES pH 8.5, 1 mM EDTA, 20% sucrose, 5% glycerol and 0.05% Tween 20. The mixture was incubated on ice for 1 h and the reaction was stopped by addition of Tris–HCl pH 7.9 to a final concentration of 25 mM. Following incubation for 15 min at room temperature, an equal volume of a buffer containing 0.5 M Tris–HCl pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 20% glycerol was added, and the sample was concentrated by ultrafiltration using an Amicon 10 filter to a volume of 30 µl.

For in vivo analyses, NT1(pZLQR), grown in 200 ml of MG/L medium, was harvested by centrifugation. The cells were washed three times with, and resuspended in 10 ml of 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.6. DSP was added (1 mM final concentration), the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min and the reaction was stopped with Tris buffer as described above. Treated cells were collected by centrifugation, washed three times with sodium phosphate buffer and the pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of TNEGT buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.9, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol and 0.05% Tween 20). The cells were broken in the French press and the lysates were separated into soluble and particulate fractions as described above.

Protein electrophoresis and western and far western blot analyses

Protein samples in buffer containing DTT were subjected to electrophoresis in 12 or 15% polyacrylamide gels containing 0.1% SDS (SDS–PAGE) as described previously (Luo et al., 2000). For non-reducing conditions, DTT was omitted from the sample buffer. Gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. Alternatively, the proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and detected using murine polyclonal anti-TraR antiserum, all as described previously (Luo et al., 2000). N-terminal deletion mutants of TraR fail to interact with our anti-TraR antiserum (Luo and Farrand, 1999). These mutant proteins were detected by far western blot analysis using the antiactivator TraM and its murine anti-TraM antiserum as the detection probe (Luo et al., 2000). In all cases protein–antibody complexes were detected chromogenically as described previously (Luo et al., 2000).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Archie Portis for the use of his FPLC apparatus. Portions of this work were supported by grant No. R01 GM52465 from the NIH to S.K.F.

References

- Adar Y.Y. and Ulitzur,S. (1993) GroESL proteins facilitate binding of externally added inducer by LuxR protein-containing E.coli cells. J. Biolumin. Chemilumin., 8, 261–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck von Bodman S. and Farrand,S.K. (1995) Capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis and pathogenicity of Erwinia stewartii require induction by an N-acylhomoserine lactone autoinducer. J. Bacteriol., 177, 5000–5008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck von Bodman S., Majerczak,D.R. and Coplin,D.L. (1998) A negative regulator mediates quorum-sensing control of exopolysaccharide production in Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 7687–7692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cangelosi G.A., Best,E.A., Martinetti,C. and Nester,E.W. (1991) Genetic analysis of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Methods Enzymol., 145, 177–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha C., Gao,P., Chen,Y.-C., Shaw,P.D. and Farrand,S.K. (1998) Production of acyl-homoserine lactone quorum-sensing signals by Gram-negative plant-associated bacteria. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact., 11, 1119–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilton M.-D., Currier,T.C., Farrand,S.K., Bendich,A.J., Gordon,M.P. and Nester,E.W. (1974) Agrobacterium tumefaciens and PS8 bacteriophage DNA not found in crown gall tumors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 71, 3672–3676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S.H. and Greenberg,E.P. (1991) The C-terminal region of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR protein contains an inducer-independent lux gene activating domain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 115–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S.H. and Greenberg,E.P. (1992) Genetic evidence for multimerization of LuxR, the transcriptional activator of Vibrio fischeri luminescence. Mol. Marine Biol. Biotechnol., 1, 408–413. [Google Scholar]

- Dang T.A., Zhou,X.-R., Graf,B. and Christie,P.J. (1999) Dimerization of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB4 ATPase and the effect of ATP-binding cassette mutations on the assembly and function of the T-DNA transporter. Mol. Microbiol., 32, 1239–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Maagd R.A. and Lugtenberg,B. (1986) Fractionation of Rhizobium leguminosarum cells into outer membrane, cytoplasmic membrane, periplasmic, and cytoplasmic components. J. Bacteriol., 167, 1083–1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egland K.A. and Greenberg,E.P. (2000) Conversion of the Vibrio fischeri transcriptional activator, LuxR, to a repressor. J. Bacteriol., 182, 805–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrand S.K., Hwang,I. and Cook,D.M. (1996) The tra region of the nopaline-type Ti plasmid is a chimera with elements related to the transfer systems of RSF1010, RP4 and F. J. Bacteriol., 196, 4233–4247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua W.C. and Winans,S.C. (1994) A LuxR–LuxI type regulatory system activates Agrobacterium Ti plasmid conjugal transfer in the presence of a plant tumor metabolite. J. Bacteriol., 176, 2796–2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua C. and Winans,S.C. (1996) Localization of OccR-activated and TraR-activated promoters that express two ABC-type permeases and the traR gene of Ti plasmid pTiR10. Mol. Microbiol., 20, 1199–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua W.C., Winans,S.C. and Greenberg,E.P. (1994) Quorum sensing in bacteria: the LuxR–LuxI family of cell density-responsive transcriptional regulators. J. Bacteriol., 17, 269–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanzelka B.L. and Greenberg,E.P. (1995) Evidence that the N-terminal region of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR protein constitutes an autoinducer-binding domain. J. Bacteriol., 177, 815–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J.C. (1995) Repressor fusions as a tool to study protein–protein interactions. Structure, 3, 431–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J.C., O’Shea,E.K., Kim,P.S. and Sauer,P.T. (1990) Sequence requirements for coiled-coils: analysis with λ repressor-GCN4 leucine zipper fusions. Science, 25, 1400–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang I., Li,P.-L., Zhang,L., Piper,K.R., Cook,D.M., Tate,M.E. and Farrand,S.K. (1994) TraI, a LuxI homologue, is responsible for production of conjugation factor, the Ti plasmid N-acylhomoserine lactone autoinducer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 4639–4643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang I., Smyth,A.J, Luo,Z.-Q. and Farrand,S.K. (1999) Modulating quorum sensing by antiactivation: TraM interacts with TraR to inhibit activation of Ti plasmid conjugal transfer genes. Mol. Microbiol., 34, 282–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan H.B. and Greenberg,E.P. (1985) Diffusion of autoinducer is involved in regulation of the Vibrio fischeri luminescence system. J. Bacteriol., 163, 1210–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keleti G. and Lederer,W.H. (1974) Handbook of Micromethods for the Biological Sciences, Van Nostrand Reinhold Co., New York, NY, pp. 74–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kolibachuk D. and Greenberg,E.P. (1993) The Vibrio fischeri luminescence gene activator LuxR is a membrane-associated protein. J. Bacteriol., 175, 7307–7312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z.-Q. and Farrand,S.K. (1999) Signal-dependent DNA binding and functional domains of the quorum-sensing activator TraR as identified by repressor activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 9009–9014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z.-Q., Qin,Y. and Farrand,S.K. (2000) The antiactivator TraM interferes with the autoinducer-dependent binding of TraR to DNA by interacting with the C-terminal region of the quorum-sensing activator. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 7713–7722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan S.J. et al. (1995) Carbapenem antibiotic production in Erwinia carotovora is regulated by CarR, a homologue of the LuxR transcriptional activator. Microbiology, 141, 541–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moré M.I., Finger,L.D., Stryker,J.L., Fuqua,C., Eberhard,A. and Winans,S.C. (1996) Enzymatic synthesis of a quorum-sensing autoinducer through use of defined substrates. Science, 272, 1655–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oger P., Kim,K.-S., Sackett,R.L., Piper,K.R. and Farrand,S.K. (1998) Octopine-type Ti plasmids code for a mannopine-inducible dominant-negative allele of traR, the quorum-sensing activator that regulates Ti plasmid conjugal transfer. Mol. Microbiol., 27, 277–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson J.P., Van Delden,C. and Iglewski,B.H. (1999) Active efflux and diffusion are involved in transport of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cell-to-cell signals. J. Bacteriol., 181, 1203–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper K.R. and Farrand,S.K. (2000) Quorum sensing but not autoinduction of Ti plasmid conjugal transfer requires control by the opine regulon and the antiactivator TraM. J. Bacteriol., 182, 1080–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper K.R., Beck von Bodman,S. and Farrand,S.K. (1993) Conjugation factor of Agrobacterium tumefaciens regulates Ti plasmid transfer by autoinduction. Nature, 362, 448–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptashne M. (1986) A Genetic Switch. Blackwell Press, Palo Alto, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer A., Hanzelka,B.L., Eberhard,A. and Greenberg,E.P. (1996a) Quorum sensing in Vibrio fischeri: probing autoinducer–LuxR interactions with autoinducer analogs. J. Bacteriol., 178, 2897–2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer A., Val,D.L., Hanzelka,B.L., Cronan,J.E.,Jr and Greenberg,E.P. (1996b) Generation of cell-to-cell signals in quorum sensing: acyl homoserine lactone synthase activity of a purified Vibrio fischeri LuxI protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 9505–9509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadel G.S., Young,R. and Balwin,T.O. (1990) Use of regulated cell lysis in a lethal genetic selection in Escherichia coli: identification of the autoinducer binding region of the LuxR protein from Vibrio fischeri ATCC 7744. J. Bacteriol., 172, 3980–3987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P.D., Gao,P., Daly,S.L., Cha,C., Cronan,J.,Jr, Rinehart,K.L. and Farrand,S.K. (1997) Detecting and characterizing N-acyl homoserine lactone signal molecules by thin-layer chromatography. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 6036–6041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitnikov D.M., Schineller,J.B. and Baldwin,T.O. (1995) Transcriptional regulation of bioluminescence genes from Vibrio fischeri. Mol. Microbiol., 17, 801–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens A.M., Dolan,K.M. and Greenberg,E.P. (1994) Synergistic binding of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR transcriptional activator domain and RNA polymerase to the lux promoter region. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 12619–12623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift S., Williams,P. and Stewart,G.S.A.B. (1999) N-acylhomoserine lactones and quorum sensing in the proteobacteria. In Dunny,G.M. and Winans,S.C. (eds), Cell–Cell Signaling in Bacteria. American Society for Microbiology Press, Washington, DC, pp. 291–313. [Google Scholar]

- Watson B., Currier,T.C., Gordon,M.P., Chilton,M.-D. and Nester,E.W. (1975) Plasmid required for virulence of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol., 123, 255–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch M., Todd,D.E., Whitehead,N.A., McGowan,S.J., Bycroft,B.W. and Salmond,G.P.C. (2000) N-acyl homoserine lactone binding to the CarR receptor determines quorum-sensing specificity in Erwinia. EMBO J., 19, 631–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Murphy,P.J., Kerr,A. and Tate,M.E. (1993) Agrobacterium conjugation and gene regulation by N-acyl-l-homoserine lactones. Nature, 362, 446–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J. and Winans,S.C. (1999) Autoinducer binding by the quorum-sensing regulator TraR increases affinity for target promoters in vitro and decreases TraR turnover rates in whole cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 4832–4837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Beaber,J.W., Moré,M.I., Fuqua,C., Eberhard,A. and Winans,S.C. (1998) Analogs of the autoinducer 3-oxooctanoyl-homoserine lactone strongly inhibit activity of the TraR proteins of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol., 180, 5398–5405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]