Abstract

High transcription is associated with genetic instability, notably increased spontaneous mutation rates, which is a phenomenon termed Transcription-Associated-Mutagenesis (TAM). In this study, we investigated TAM using the chromosomal CAN1 gene under the transcriptional control of two strong and inducible promoters (pGAL1 and pTET) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Both pTET- and pGAL1-driven high transcription at the CAN1 gene result in enhanced spontaneous mutation rates. Comparison of both promoters reveals differences in the type of mutagenesis, except for short (−2 and −3 nt) deletions, which depend only on the level of transcription. This mutation type, characteristic of TAM, is sequence dependent, occurring prefentially at di- and trinucleotides repeats, notably at two mutational hotspots encompassing the same 5′-ACATAT-3′ sequence. To explore the mechanisms underlying the formation of short deletions in the course of TAM, we have determined CanR mutation spectra in yeast mutants affected in DNA metabolism. We identified topoisomerase 1-deficient strains (top1Δ) that specifically abolish the formation of short deletions under high transcription. The rate of the formation of (−2/−3nt) deletions is also reduced in the absence of RAD1 and MUS81 genes, involved in the repair of Top1p–DNA covalent complex. Furthermore ChIP analysis reveals an enrichment of trapped Top1p in the CAN1 ORF under high transcription. We propose a model, in which the repair of trapped Top1p–DNA complexes provokes the formation of short deletion in S. cerevisiae. This study reveals unavoidable conflicts between Top1p and the transcriptional machinery and their potential impact on genome stability.

Genetic instability is both beneficial for organisms as raw material for evolution and generally detrimental for individuals as it can suppress advantageous if not essential function, and in the case of higher eukaryotes, can lead to cancer and ageing. Transcription influences genetic stability in a complex manner by affecting DNA repair, replication, recombination and mutagenesis (1–3). Although transcription enhances the repair capacity of the cell in the transcription-coupled repair (TCR) pathway, conflicts between DNA replication and transcription are likely associated with genomic instability (1, 2). A recent study identified about 1,400 natural replication pause sites in the yeast genome including highly expressed genes, which points to transcription at the origin of stalled replication forks (3, 4). Conflicts between transcription and replication have been shown to elevate recombination rates in yeast and mammalian cells, a process called transcription-associated recombination (TAR; refs. 5–7). High transcription level is also associated with enhanced spontaneous mutagenesis in Escherichia coli (8, 9), bacteriophage T7 (10), and mammalian cells (11, 12).

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, an increased transcription level stimulates spontaneous mutagenesis, a phenomenon termed transcription associated mutagenesis or TAM (13). Under high transcription, the reversion rate of the pGAL-lys2ΔBgl allele was increased by about 30-fold, compared with the one measured under low-transcription condition. The use of a reversion assay imposed a biased ascertainment, because only a specific subset of mutation types could be detected. To overcome this limitation, the same team has investigated mutation spectra using a forward mutation assay at the LYS2 gene, placed under the control of pGAL1 promoter. In the high-transcription condition, short insertion-deletion mutations predominated, most notably two-nucleotide deletions (−2nt) revealing a mutational signature for TAM (14).

In the present study, we developed a forward mutation assay to assess TAM at the CAN1 locus in S. cerevisiae. The CAN1 gene was placed under the control of two strong and inducible promoters (pGAL1 and pTET) at its endogenous location on Chromosome V. Our results show that both pTET- and pGAL1-driven high transcription at the CAN1 gene result in enhanced spontaneous mutation rate. Sequencing the full CAN1 gene in CanR mutants isolated under high transcription reveals a strong impact of −2nt and −3nt deletions at repeated di- or trinucleotides sequences. To explore the mechanisms of TAM and more specifically the formation of short deletions, we have determined mutation spectra in a variety of mutants affected in DNA metabolism. Among them, we identified the topoisomerase 1-deficient strains (top1Δ) that abolish −2nt and −3nt deletions under high transcription. The role of Top1p in TAM is also revealed by the enrichment of Top1p–DNA covalent complexes on the CAN1 ORF when the gene is highly transcribed. Our data suggest that, under high transcription, conflicts frequently occur between the transcription machinery and Top1p. We propose a model in which the repair of irreversible Top1p–DNA complexes will provoke −2nt and −3nt deletions that are the hallmark of TAM in S. cerevisiae.

Results and Discussion

Increase of Spontaneous Mutagenesis at CAN1 Under High Transcription.

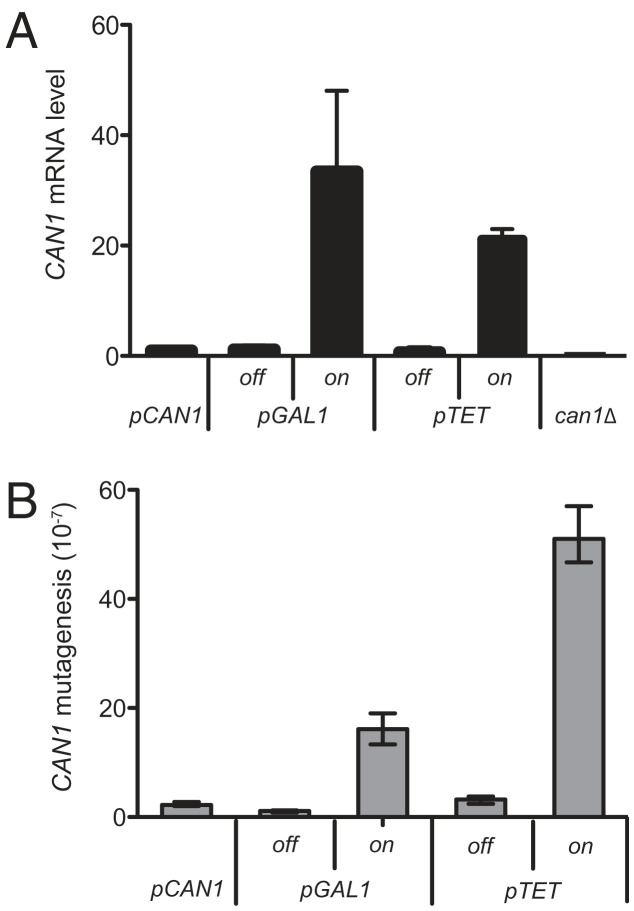

In this study, we developed a forward mutation assay to explore TAM at the CAN1 locus in S. cerevisiae. The CAN1 gene at its endogenous localization on Chromosome V was placed under the transcriptional control of two strong promoters (pGAL1 and pTET), whose activity can be regulated by galactose and doxycycline (Dox), respectively. The properties of the resulting strains (pGAL1-CAN1 and pTET-CAN1) were compared with those of the control strain (pCAN1-CAN1; strains used in this study are listed in Table S1). Together, these strains permit the study of forward mutagenesis at the CAN1 locus under five different transcriptional conditions: (i) low transcription from endogenous CAN1 promoter (pCAN1); (ii) low transcription from pGAL1 in the presence of glucose (pGAL1-off); (iii) high transcription from pGAL1 in the presence of galactose (pGAL1-on); (iv) low transcription from pTET in the presence of Dox (pTET-off); and (v) high transcription from pTET in the absence of Dox (pTET-on). High-transcription conditions, pGAL1-on and pTET-on, result in a strong increase in CAN1 mRNA level, 20- to 30-fold compared with pCAN1 (Fig.1A). In the pGAL1-off and pTET-off conditions, CAN1 mRNA level is decreased down to pCAN1 level, but remains higher than in can1Δ strain, indicating that CAN1 repression is not complete (Fig.1A). High transcription at CAN1 generates genetic instability, because the spontaneous CanR mutation rate is increased by 7-fold under pGAL1-on and 23-fold under pTET-on conditions, compared with the endogenous pCAN1 (Fig.1B). This mutagenesis requires transcription activation, because it is not observed under low-transcription conditions (pGAL1-off and pTET-off; Fig.1B). These data strongly suggest that TAM can be generalized, because it applies at least to two different loci, LYS2 and CAN1, in S. cerevisiae.

Fig. 1.

Increase of CAN1 spontaneous mutagenesis associated with high transcription. (A) Steady-state level of CAN1 mRNA in wild-type, pGAL1-CAN1, pTET-CAN1, and can1Δ strains grown under various conditions: (i) YPD for pCAN1 and can1Δ, (ii) YPD (pGAL1-off) or YP Galactose (pGAL1-on), (iii) YPD plus Dox (1 mg/L; pTET-off) or YPD (pTET-on). CAN1 mRNA was quantified by RT-PCR. (B) CanR forward mutagenesis was measured in saturated cultures. Rates of forward mutation at the CAN1 locus were determined from the number of CanR mutant colonies by the method of the median (38). The 95% confidence intervals are calculated.

CanR Mutation Spectra Under Low and High Transcription.

To get further information about the mechanisms of TAM, CanR mutants generated under the different transcription conditions were collected, and mutation spectra were determined by sequencing the entire CAN1 gene. Under low transcription (pCAN1), base substitutions (BPS) predominate (83% of total) followed by one-nucleotide indels (−1/+1nt; 8% of total; Table 1). Under high transcription (pTET-on), we observed an overall enhanced CanR mutation rate (23-fold) compared with pCAN1, corresponding to enhanced rates for all types of mutations such as BPS (11-fold) and (−1/+1nt) indels (52-fold; Table 1). The pTET-on spectra also revealed a new and major (30% of total) class of mutations, short deletions of two or three nucleotides (−2/−3nt), not represented in the control spectrum (>385-fold increase; Table 1). Some CanR mutants (6 of 83) exhibit no mutation inside the ORF of CAN1. Further analysis showed that these CanR clones have mutations in the gene coding for tetR-VP16 hybrid transcription activator, located upstream from CAN1 in the pTET-CAN1 construct (Fig. S1A), whose inactivation leads to the absence of CAN1 expression (Fig. S1B) and thus to canavanine resistance.

Table 1.

CanR mutation spectra upon low and high transcription

| pCAN1 (low) | pTET-on (high) | pGAL1-on (high) | ||||

| Mutation | Freq. (%) | Rate* (10−7) | Freq. (%) | Rate* (10−7) | Freq. (%) | Rate* (10−7) |

| Total | 2.2 (2.0–2.8)† | 51.0 (47–57)† | 16.1 (13–19)† | |||

| BPS | 51/62 (83) | 1.8 | 32/83 (39) | 19.7 | 7/63 (11) | 1.8 |

| BPS at GC | 39/62 (63) | 1.4 | 28/83 (34) | 17.2 | 6/63 (10) | 1.5 |

| BPS at AT | 12/62 (19) | 0.4 | 4/83 (5) | 2.5 | 1/63 (2) | 0.3 |

| Indels | 7/62 (11) | 0.3 | 42/83 (51) | 25.8 | 56/63 (89) | 14.3 |

| (−1/+1) nt | 5/62 (8) | 0.2 | 17/83 (21) | 10.5 | 5/63 (8) | 1.3 |

| (−2/−3) nt | 0/62 (0) | <0.04 | 25/83 (30) | 15.4 | 51/63 (81) | 13.0 |

| Other ins/del | 2/62 (3) | 0.1 | 0/83 (0) | <0.6 | 0/63 (0) | <0.3 |

| Complex‡ | 4/62 (6) | 0.1 | 3/83 (4) | 1.8 | 0/63 (0) | <0.3 |

| Out of ORF‡ | 0/62 (0) | <0.04 | 6/83 (7) | 3.7 | 0/63 (0) | <0.3 |

*Mutation rates were determined by multiplying the proportion occurrence of specific mutation types by the overall mutation rate for that strain. When no events were observed, the rate was estimated assuming the occurrence of one event.

†Numbers in parentheses correspond to 95% confidence intervals.

‡Complex mutation refers to a mutation composed of more than one molecular event. Out of ORF events corresponds to CanR mutants displaying no mutation inside CAN1 ORF.

In the pGAL1-on condition (high transcription), an overall enhanced CanR mutation rate (sevenfold compared with pCAN1) is also observed (Table 1). This increase reflects mostly (−2/−3nt) deletion formation (89% of total and >325-fold increase), with a modest stimulation of (−1/+1nt) indels (8% of total and 6-fold increase; Table 1). Furthermore, the rate of formation of (−2/−3nt) deletions is similarly enhanced under pGAL1-on and pTET-on conditions (13.0 × 10−7 and 15.4 × 10−7, respectively), which is coherent with a similar increase in CAN1 mRNA levels (Table 1 and Fig. 1A). Thus, (−2/−3nt) short deletions seem to be a direct consequence of high transcription, independently of the promoter (pGAL1 or pTET) and the reporter gene used (CAN1 or LYS2; this study and ref. 14). Interestingly, our results also show major differences in mutation spectra between pGAL1- and pTET-driven transcription of CAN1, primarily the absence of stimulation of BPS in pGAL1-on. The molecular bases for these differences remain unexplained.

Identification of TAM-Associated Mutational Hotspots for (−2/−3nt) Deletions in CAN1.

Because (−2/−3nt) deletions are the hallmark of TAM, we decided to focus our attention on this class of events. We collected the position of 76 (−2/−3nt) deletions from both pTET-on and pGAL1-on conditions (Table 2 and Fig. S2). These deletions are mostly found (89%) inside di- and trinucleotide tandem repeats without any correlation between the number of repeats and the occurrence of the deletion (Table 2). For instance, the four-repeat sequence (5′-AGAGAGAG-3′) at the position 254–261 is associated with only 1 (−2nt) deletion, whereas 23 (−2nt) deletions occur inside the repeat (5′-ATAT-3′) at the position 1127–1130 (Table 2 and Fig. S2). Most of the (−2nt) events occur at (5′-ATAT-3′) repeats rather than monotonous runs of (As) or (Ts) in CAN1, the classical targets of replication errors (Table 2 and Fig. S2). In addition, the distribution of (−2/−3nt) deletions along CAN1 points to the identification of two strong mutational hotspots for (−2nt) deletions at position 275 and 1127 (47% of all short deletions) and to a third hotspot for (−3nt) deletions at position 970 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sequence context at sites of (−2/−3nt) deletions in the high-transcription conditions

| Position* | pGAL1-on occurrence | pTET-on occurrence | Mutation | Sequence context† |

| 254 | 1 | 0 | −AG/GA | GA AGAGAGAG CT |

| 275 | 10 | 3 | −AT/TA | AC ATAT TG |

| 294 | 0 | 1 | −TGG/GGT/GTG | CT TGGTGGT AC |

| 369 | 1 | 1 | −AT/TA | CT TATAT CA |

| 375 | 0 | 2 | −AT/TA | TC ATAT TT |

| 381 | 1 | 0 | −AT/TA | TT TAT TT |

| 392 | 0 | 1 | −TTC/TCT/CTT | GG TTCTT TG |

| 399 | 3 | 0 | −AT/TA | GC ATAT TC |

| 463 | 1 | 0 | −GT/TG | CA GTGT TC |

| 470 | 0 | 1 | −AC/CA | CT CACA AA |

| 539 | 0 | 1 | −CT | CA CT TT |

| 704 | 0 | 1 | −TT | AG TTTT AG |

| 727 | 1 | 0 | −AT/TA | TA ATAT AC |

| 964 | 2 | 3 | −AA | TC AAAAAA GT |

| 970 | 7 | 0 | −GTT/TTG/TGT | AA GTTGTT TT |

| 973 | 0 | 1 | −GT/TG | GT TGT TT |

| 1002 | 1 | 0 | −CT/TC | GG CTCTCT AT |

| 1127 | 18 | 5 | −AT/TA | AC ATAT CT |

| 1170 | 1 | 0 | −AA | GC AAA TT |

| 1199 | 0 | 1 | −TT | TA TTTT AT |

| 1363 | 1 | 0 | −ATC/TCA | AT ATCA CT |

| 1372 | 1 | 0 | −GTT/TTG | GG TGTTG CA |

| 1406 | 1 | 0 | −TC/CT | AA TCTC GC |

| 1448 | 0 | 3 | −TC/CT | CA TCTCTC GT |

| 1454 | 1 | 0 | −GT/TG | TC GTG AC |

| 1464 | 0 | 1 | −AC | TT AC CA |

*Positions are relative to +1 of coding sequence and correspond to numbering in Fig. S2.

†Underlined characters represent the sequence where the deletion occurred.

The two (−2nt) deletion hotspots display the same nucleotide sequence (5′-ACATAT-3′), which does not occur elsewhere inside CAN1. Interestingly, this sequence is absent from the LYS2 fragments sequenced in the other TAM studies (14, 15). The occurrence of an excess of CanR mutants at the (5′-ACATAT-3′) sequences in both pGAL1-on and pTET-on condition assesses this hexameric sequence as a genuine hotspot for (−2nt) deletions. The in-frame deletion of three nucleotides (−3nt) is translated in the removal of one amino acid in the protein. Therefore, the (−3nt) deletion hotspot may reflect an important amino acid for the Can1p function rather than a true mutation hotspot. Our data reveal information about TAM in yeast: (i) (−2/−3nt) deletions occur almost exclusively inside repeated sequence; (ii) the number of repeats does not influence the occurrence of deletions; (iii) most deletions occur inside (5′-ATAT-3′) repeats; and (iv) the (5′-ACATAT-3′) sequence behaves as a mutation hotspot for TAM.

Topoisomerase 1 Is Required for the Formation of TAM-Associated (−2/−3nt) Deletions.

To get insight into the mechanisms of TAM, we looked for yeast mutants that would affect CanR mutation rate and mutation spectrum under high transcription using the pTET-CAN1 strain. In a gene-specific approach, we tested mutants involved in the DNA metabolism and the maintenance of genetic stability. Among them, the rev3Δ and the top1Δ strains showed a significant (greater than twofold) reduction in overall CanR mutation rate (Table 3). Analysis of CanR mutation spectra shows that REV3 deletion has no significant impact on the rate of (−2/−3nt) deletions, whereas it nearly completely suppresses BPS and (−1/+1nt) events in the pTET-on condition (Table 3). The position of (−2/−3nt) deletions in the rev3Δ context is not modified compared with the wild type (Fig. S2). Accordingly, the mutagenesis observed in pGAL1-on, in which TAM consist mainly of (−2/−3nt) deletions, is essentially unchanged in the rev3Δ mutant (Table 4). These results indicate that (−2/−3nt) deletions are formed independently of Polζ.

Table 3.

CanR mutation spectra under high transcription (pTET-on) in top1Δ and rev3Δ mutant strains

| Type of event | pTET-on wild type (83 events) | pTET-on top1Δ (39 events) | pTET-on rev3Δ (48 events) |

| Total* | 51.0 (47-57)† | 24.0 (22–26)† | 14.2 (13–16)† |

| BPS | 19.7 | 8.0 | 0.6 |

| (−1/+1) nt | 10.5 | 7.4 | 1.2 |

| (−2/−3) nt | 15.4 | <0.6 | 10.1 |

| Larger ins/del | <0.6 | 1.8 | <0.3 |

| Other‡ | 5.5 | 6.8 | 2.4 |

*Mutation rates were determined by multiplying the proportion occurrence of specific mutation types by the overall mutation rate for that strain. When no events were observed, the rate was estimated assuming the occurrence of one event.

†Numbers in parentheses correspond to 95% confidence intervals.

‡Other refers to complex mutations (composed of more than one molecular event) and mutations outside CAN1 ORF.

Table 4.

CanR mutation spectra under high transcription (pGAL1-on) in top1Δ, rev3Δ, tdp1Δ, and rad1Δ mus81Δ mutant strains

| Type of event | pGAL1-on wild type (63 events) | pGAL1-on rev3Δ (30 events) | pGAL1-on top1Δ (31 events) | pGAL1-on tdp1Δ (30 events) | pGAL1-on mus81Δ rad1Δ (58 events) |

| Total* | 16.1 (13–19)† | 13.4 (11–20)† | 5.1 (3.5–5.9)† | 13.5 (11–18)† | 11.9 (9–14)† |

| Base substitution | 1.8 | <0.5 | 3.1 | <0.5 | 2.3 |

| (−1/+1nt) | 1.3 | <0.5 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 2.9 |

| (−2/−3nt) | 13.0 | 13.0 | 0.2 | 11.3 | 4.9 |

| Larger ins/del | <0.3 | 0.5 | <0.2 | 0.9 | 0.4 |

| Complex‡ | <0.3 | <0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 1.4 |

*Mutation rates were determined by multiplying the proportion occurrence of specific mutation types by the overall mutation rate for that strain. When no events were observed, the rate was estimated assuming the occurrence of one event.

†Numbers in parentheses correspond to 95% confidence intervals.

‡Complex mutation refers to a mutation composed of more than one molecular event.

In contrast, our results show that TOP1 deletion is associated with a nearly complete suppression of (−2/−3nt) deletions both in pTET-on (Table 3) and pGAL1-on conditions (Table 4). Interestingly, Top1p has not been involved so far into any mutagenic pathway in S. cerevisae. Indeed, top1Δ in the pCAN1 context has a CanR mutation rate and spectrum very similar to the wild type (Table S2). Top1p relaxes positive and negative supercoiling, relieving the torsional stress associated with DNA replication, transcription, and chromatin condensation (16). Here, we propose that, under high transcription, Top1p more frequently catalyzes irreversible single-strand cleavage, covalently attaching the 3′ end of broken DNA, and that the processing of these Top1p–DNA intermediates could lead to the formation of (−2/−3nt) deletions.

Alternatively to a direct role of Top1p on the formation of short deletions, two other hypotheses can be proposed. First, the absence of Top1p could impact the mutagenesis through its interaction with other proteins, independently of its topoisomerase activity. To test this hypothesis, top1Δ strains were complemented with a chromosomal version of Top1p (wild type) or a catalytically dead Top1p-Y727F (17). In the pGAL1-on condition, the mutant Top1p-Y727F is not able to restore a wild-type CanR mutagenesis, whereas the wild-type Top1p does (Fig. S3). Thus, the topoisomerase catalytic activity of Top1p seems necessary for the formation of short deletions. Second, Top1p could act indirectly modulating the transcriptional activity at CAN1. Thus, top1Δ strains would not be able to transcribe CAN1 at high level, which in turn would suppress TAM. The data shown in Fig. S4 suggest this hypothesis is incorrect, because the steady-state levels of CAN1 mRNA in pTET-on condition are not different in wild-type and top1Δ strains. Similarly, the impact of Rev3p on TAM at the level of BPS and (−1/+1nt) cannot be explained by a reduced accumulation of CAN1 mRNA (Fig. S4). Therefore, our data strongly suggest that the formation of (−2/−3nt) deletions, which are the signature of the TAM process, is directly linked to Top1p topoisomerase activity.

Role of Rad1p/Mus81p in the Formation of TAM-Associated (−2/−3nt) Deletions.

To support a direct role of Top1p in the formation of short deletions, we explored the impact of genes that contribute to the removal of trapped Top1p on DNA. Using camptothecin (Cpt), a Top1p-specific poison, several pathways have been identified to repair trapped Top1p on DNA: (i) Cleavage of the Top1p–DNA phosphodiester bond by the tyrosyl DNA phosphodiesterase Tdp1p (18, 19); (ii) removal of a DNA fragment containing trapped Top1p by a redundant network of endonucleases, notably Rad1-Rad10 and Mus81-Mms4 (20, 21); and (iii) collision between blocked Top1p and replication fork, generating a double-strand break repaired by homologous recombination (22). Here, we investigated the formation of TAM-associated (−2/−3nt) deletions in tdp1Δ and in mus81Δ rad1Δ double-mutant strains. We chose the mus81Δ rad1Δ double mutant because single mutants may have very minor phenotype, as already reported for their sensitivity to the lethal action of Cpt (21).

Under high transcription (pGAL1-on), the tdp1Δ mutant displays no significant effect on the Top1p-dependent formation of (−2/−3nt) deletions (Table 4). In contrast, the (−2/−3nt) deletion rate is partially but significantly reduced (2.7-fold) in the mus81Δ rad1Δ double mutant (Table 4). These results suggest that 3′-flap endonucleases promote repair pathways for trapped Top1p–DNA responsible for (−2/−3nt) deletions, whereas Tdp1p does not. It has been shown that Tdp1p has a very weak activity on 3′-phosphotyrosine in a double-strand nicked DNA, a structure that could mimic the one generated by conflicts between RNA polymerase and Top1p (23). In contrast, Rad1-Rad10 and Mus81-Mms4 can act efficiently on Top1p covalently bound at the 3′-side of the nick in double-stranded DNA. In the absence of these enzymes, Top1p covalent complex should be repaired either by other endonucleases such as Slx1-Slx4 and the MRX complex (20, 21), yielding (−2/−3nt) deletions or in an error-free manner by homologous recombination after the formation of a double-strand break (22).

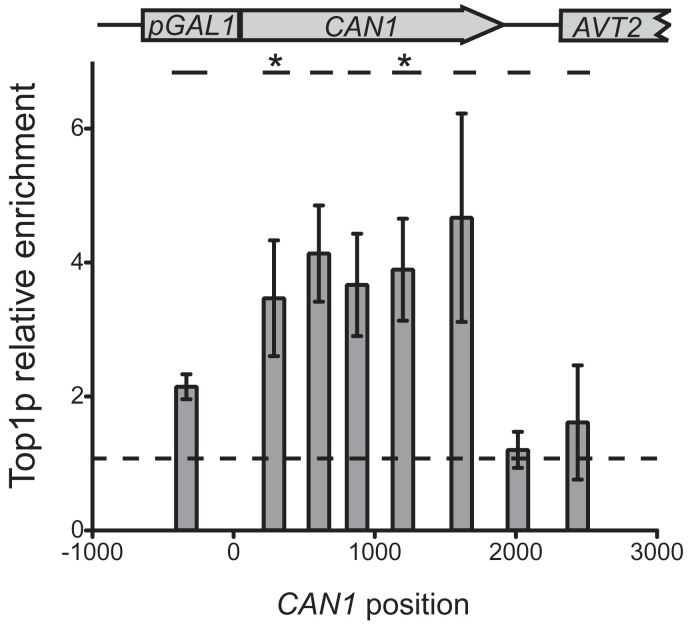

Enrichment in Covalent Top1p–DNA Adducts in Highly Transcribed CAN1

The impact of Rad1-Rad10 and Mus81-Mms4 on the formation of Top1p-dependent (−2/−3nt) deletions suggests the accumulation of Top1p covalently trapped to DNA under high transcription. To explore this possibility, we developed a ChIP assay for Top1p-GFP without cross-linking agent (SI Text). Importantly, the Top1p-GFP fusion protein behaves as a fully active topoisomerase 1, because it confers sensitivity to Cpt (Fig. S5) and provokes the formation of (−2/−3nt) deletions (Table S2), like the Top1p. This ChIP assay should allow us to detect Top1p–DNA covalent complexes, notably in the presence of Cpt, which stabilizes those complexes. Indeed, under the low-transcription condition, Cpt-treated cells displayed a significant enrichment of Top1p–DNA in the CAN1 locus (promoter, ORF and downstream region) compared with untreated cells (Fig. S6). Thus, our ChIP assay without cross-linking agent most likely reveals Top1p–DNA adducts. Under the high-transcription condition (pGAL1-on), we observed a significant enrichment of Top1p–DNA (4- to 5-fold) along the ORF of CAN1 compared to the low-transcription (pGAL1-off) condition (Fig.2). In contrast, enrichment of Top1p–DNA is much weaker (<2-fold) in the promoter and in the downstream regions of CAN1 under high transcription of CAN1 (Fig. 2). The presence of covalently bound Top1p on the ORF of CAN1 under high transcription points to a direct role of Top1p in the formation of (−2/−3nt) deletions, suggesting that mutations occur nearby its site of fixation. This conclusion addresses the question of the two hotspots observed in this study (Table 2 and Fig. S2). Interestingly, the regions that span the two deletion hotspots (position 275 and 1127) do not show significantly higher level of Top1p–DNA complexes compared with the other CAN1 regions (Fig.2).

Fig. 2.

Top1p recruitment on CAN1 locus under high and low transcription. Top1p-GFP recruitment under pGAL1-on and pGAL1-off condition was analyzed by ChIP without cross-linking agent as described in SI Text. The figure shows the ratio between pGAL1-on and pGAL1-off signal. The position of the primers couples inside CAN1 regions is represented above. Asterisks correspond to the (−2nt) deletion hotspots.

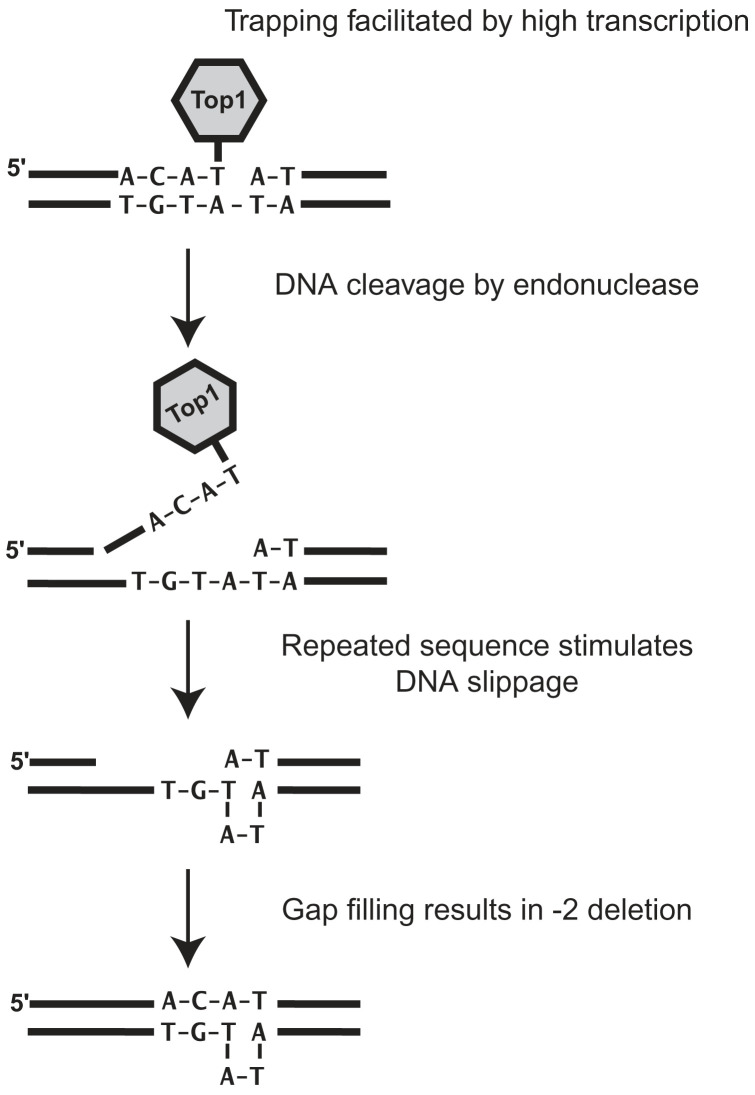

Model for Top1p-Dependent Formation of TAM-Associated (−2/−3nt) Deletions.

Taken together, our results support a model in which Top1p catalytic activity is the direct cause of TAM-associated short deletions in tandem repeats in S. cerevisiae (Fig.3). The model decomposes in three successive steps: (i) The formation of a trapped covalent Top1p–DNA complex at (nearby) the site of mutation, facilitated under high transcription condition; (ii) the elimination of the Top1p-containing end by an endonuclease (Rad1-Rad10/Mus81-Mms4), which results in the formation of a gap into DNA; (iii) the DNA repair synthesis, which is accompanied by the sliding of the template strand and realignment. The fact that (−2/−3nt) deletions occur at di- and trinucleotide tandem repeats probably reflects a “facilitated sliding-realignment” of the template. Finally, the 5′-end is processed, ligation occurs and mutation is fixed after a round of replication or elimination of the loop by MMR.

Fig. 3.

Model for Top1p-dependent formation of TAM-associated (−2/−3nt) deletions.

The enhanced trapping of Top1p on highly transcribed DNA could result from the recently described association between high transcription and DNA damage (24). Indeed, these data have shown that high transcription enhances the incorporation of dUMP that can be further converted into abasic sites and single-strand breaks. All these DNA lesions have been shown to stabilize covalent Top1p–DNA complexes in vitro (25, 26). Alternatively, trapped Top1p–DNA complexes may reflect conflicts between the transcription machinery (RNA polymerases) and Top1p at highly transcribed undamaged DNA. A recent study points to the role of Top1p in suppressing genomic instability by preventing interference between replication and transcription (27). The probability of conflicts is proportional to the occupancy of the ORF by RNA polymerases in the elongation state and the need of Top1p for relaxing topological constraints. Indeed, RNA polymerase can hit Top1p before religation has occurred, generating the trapped Top1p–DNA complex (28). These two modes of formation of Top1p–DNA complexes are not exclusive to each other. It should be noted that the frequency of the conflicts between transcription and Top1p cannot be evaluated from the (−2/−3nt) deletion rates reported in this study. Indeed, conflicts might be much more frequent but mainly solved in an error-free manner in agreement with our model. The presence of Top1p on highly transcribed DNA should be essentially beneficial to the cell. Although unavoidable conflicts can occur, only a minor fraction of them lead to deleterious (−2nt) deletions.

Another unsolved question about the formation of Top1p-induced deletions is their sequence specificity at nonmonotonous di- and trinucleotide tandem repeats and hotspots at (5′-ACATAT-3′). In the accompanying paper, Lippert et al. (29) show that this hexameric sequence becomes a (−2nt) deletion hotspot when transposed into the LYS2 frameshift reversion assay. Their data point to a strong correlation between the short deletion formation and the hotspots sequence, which could point to a preferential region for Top1p recruitment. Top1p preferential binding site has been previously described in vitro using calf thymus or wheat germ Top1p (30). According to this study, the sequence 5′-ACAT-3′ could be a good substrate for Top1 cleavage. However, several other sites for short deletions are also potential Top1p-binding sites (Table 2). In addition, our ChIP experiment does not reveal a positive correlation between the frequency of Top1 trapping onto DNA and (−2/−3nt) deletion hotspots (Fig. 2). Therefore, we are in favor of a model in which the mutation hotspots are primarily determined by the capacity of sequence encompassing the 5′-ACATAT-3′ hexanucleotide to undergo a “facilitated sliding-realignment” reaction.

In mammalian cells, Top1p trapping in neurons causes genetic disorder called spinocerebellar ataxia with axonal neuropathy SCAN1 (31, 32). Therefore, the enhanced formation of irreversible Top1p–DNA complexes under high transcription demonstrated here may have deleterious effects, particularly in nondividing cells. Indeed, the model we propose does not require DNA replication and may apply to nondividing cells, like neurons.

Materials and Methods

Media and Growth Conditions.

Yeast strains were grown at 30 °C in YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 1% bactopeptone, and 2% glucose, with 2% agar for plates), YP Gal medium (1% yeast extract, 1% bactopeptone, and 2% galactose), YNBD medium (0.7% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids and 2% glucose, with 2% agar for plates) supplemented with appropriate amino acids and bases or YNB Gal medium (YNB with 2% galactose). Supplemented YNBD and YNB Gal medium lacking arginine but containing L-canavanine (Sigma) at 60 mg/L were used for the selective growth of canavanine-resistant (CanR) mutants on plates. The doxycycline cultures were performed in YPD medium containing 1 mg/L doxycycline (Sigma).

Yeast Strains.

S. cerevisiae strains used in the present study are listed in Table S1. All strains are haploid and isogenic to the wild-type strain FF18733 (MATa, leu2-3-112, trp1-289, his7-2, ura3-52, lys1-1; ref. 33). The pGAL1-CAN1 strain was constructed by the replacement at the endogenous location on the chromosome V of the 250 nucleotides downstream of CAN1 with a PCR-generated cassette from pFA6a-kanMX6-pGAL1 (34). The GAL1 cassette consists in the GAL1 upstream region containing GAL1-10 promoter and the KanMX6 marker. The pTET-CAN1 strain was similarly constructed by replacement of the downstream CAN1 region with a PCR-generated cassette from pCM225 (35) that includes seven repeats of the tetO sequence motif, the tetR-VP16 transcriptional activator gene under the control of the CMV promoter, and the KanMX4 marker. Correct integration of both promoters was confirmed by PCR and sequence analysis. For analysis of TOP1 catalytically dead mutant, top1Δ pGAL1-CAN1 strain was transformed with a shuttle vector based on pRS305, which carried wild-type or mutated TOP1 gene under the control of the endogenous TOP1 promoter, for integration into the LEU2 locus. The empty vector pRS305 served as control. For ChIP experiments, the C terminus of Top1p was tagged with GFP as described (34). Mutant strains in the pGAL1-CAN1 and pTET-CAN1 context were constructed using PCR-based allele replacement techniques (34) or by crossing and genetic analysis of meiotic events.

Spontaneous Mutation Rates.

For each strain, 11 independent cultures were inoculated with about 103 cells in 2 mL of YPD or YP Gal and grown at 30 °C for 3 d. Cell density was measured by plating dilutions on YPD agar plates and counting the colonies after 2 d at 30 °C. The quantification of canavanine-resistant mutants (CanR) was determined after plating on selective medium YNB Gal agar plates containing 60 mg/L l-canavanine for pGAL1-CAN1 strains and YNBD agar plates containing 60 mg/L l-canavanine for the other strains (36). Colonies were counted after 3–4 d at 30 °C. All experiments were repeated independently at least three times. Mutation rates were determined from the number of CanR colonies by the method of the median (37).

Mutation Spectra.

For each strain, at least 32 independent cultures were grown and plated onto L-canavanine-containing plates (one culture per plate). After 3–4 d at 30 °C, a single CanR mutant colony per plate was isolated and streaked onto selective canavanine-containing plates. Genomic DNA was purified using FTA cards (Whatman), and CAN1 gene was amplified by PCR. Sequencing of CAN1 gene (1,773 base pairs) was performed using two primers covering the entire gene.

ChIP of Top1p.

ChIP assays were performed as described (38) but without any cross-linking agent, because Top1p can directly form covalent complex with DNA. Detailed procedure is presented in SI Text.

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from exponentially growing cultures, using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen), and was reverse-transcribed using 1 μg of total RNA, Primescript reverse transcriptase (Takara), and random hexamers as primers. DNA was quantified by real-time PCR amplification on a Mastercycler ep realplex (Eppendorf, Germany). mRNA levels were calculated as the ratio of measured CAN1 mRNA and ACT1 mRNA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the UMR217 for support and discussion. Special thanks to Xavier Veaute for critical reading of the manuscript and to Monique Vacher for technical help. We thank the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique (CEA) for their support. G.B.-S. was supported by a fellowship from the CEA and Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (ARC). D.T.T. was supported by a fellowship from the Ecole Normale Supérieure.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1012582108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hanawalt PC. Subpathways of nucleotide excision repair and their regulation. Oncogene. 2002;21:8949–8956. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguilera A. The connection between transcription and genomic instability. EMBO J. 2002;21:195–201. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.3.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azvolinsky A, Giresi PG, Lieb JD, Zakian VA. Highly transcribed RNA polymerase II genes are impediments to replication fork progression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell. 2009;34:722–734. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ivessa AS, et al. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae helicase Rrm3p facilitates replication past nonhistone protein-DNA complexes. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1525–1536. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00456-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huertas P, Aguilera A. Cotranscriptionally formed DNA:RNA hybrids mediate transcription elongation impairment and transcription-associated recombination. Mol Cell. 2003;12:711–721. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prado F, Aguilera A. Impairment of replication fork progression mediates RNA polII transcription-associated recombination. EMBO J. 2005;24:1267–1276. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gottipati P, Cassel TN, Savolainen L, Helleday T. Transcription-associated recombination is dependent on replication in Mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:154–164. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00816-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beletskii A, Bhagwat AS. Transcription-induced mutations: increase in C to T mutations in the nontranscribed strand during transcription in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13919–13924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klapacz J, Bhagwat AS. Transcription-dependent increase in multiple classes of base substitution mutations in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:6866–6872. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.24.6866-6872.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beletskii A, Grigoriev A, Joyce S, Bhagwat AS. Mutations induced by bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase and their effects on the composition of the T7 genome. J Mol Biol. 2000;300:1057–1065. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendriks G, et al. Gene transcription increases DNA damage-induced mutagenesis in mammalian stem cells. DNA Repair (Amst) 2008;7:1330–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hendriks G, et al. Transcription-dependent cytosine deamination is a novel mechanism in ultraviolet light-induced mutagenesis. Curr Biol. 2010;20:170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.11.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Datta A, Jinks-Robertson S. Association of increased spontaneous mutation rates with high levels of transcription in yeast. Science. 1995;268:1616–1619. doi: 10.1126/science.7777859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lippert MJ, Freedman JA, Barber MA, Jinks-Robertson S. Identification of a distinctive mutation spectrum associated with high levels of transcription in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4801–4809. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.11.4801-4809.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim N, Abdulovic AL, Gealy R, Lippert MJ, Jinks-Robertson S. Transcription-associated mutagenesis in yeast is directly proportional to the level of gene expression and influenced by the direction of DNA replication. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:1285–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Champoux JJ. DNA topoisomerases: structure, function, and mechanism. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:369–413. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lynn RM, Bjornsti MA, Caron PR, Wang JC. Peptide sequencing and site-directed mutagenesis identify tyrosine-727 as the active site tyrosine of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA topoisomerase I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3559–3563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pouliot JJ, Yao KC, Robertson CA, Nash HA. Yeast gene for a Tyr-DNA phosphodiesterase that repairs topoisomerase I complexes. Science. 1999;286:552–555. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu C, Pouliot JJ, Nash HA. Repair of topoisomerase I covalent complexes in the absence of the tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase Tdp1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14970–14975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182557199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vance JR, Wilson TE. Yeast Tdp1 and Rad1-Rad10 function as redundant pathways for repairing Top1 replicative damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13669–13674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202242599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng C, Brown JA, You D, Brown JM. Multiple endonucleases function to repair covalent topoisomerase I complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2005;170:591–600. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.028795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nitiss J, Wang JC. DNA topoisomerase-targeting antitumor drugs can be studied in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:7501–7505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.20.7501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raymond AC, Staker BL, Burgin ABJ., Jr. Substrate specificity of tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase I (Tdp1) J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22029–22035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502148200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim N, Jinks-Robertson S. dUTP incorporation into genomic DNA is linked to transcription in yeast. Nature. 2009;459:1150–1153. doi: 10.1038/nature08033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pourquier P, et al. Effects of uracil incorporation, DNA mismatches, and abasic sites on cleavage and religation activities of mammalian topoisomerase I. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7792–7796. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.12.7792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lebedeva N, Auffret Vander Kemp P, Bjornsti MA, Lavrik O, Boiteux S. Trapping of DNA topoisomerase I on nick-containing DNA in cell free extracts of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:799–809. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tuduri S, et al. Topoisomerase I suppresses genomic instability by preventing interference between replication and transcription. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1315–1324. doi: 10.1038/ncb1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu J, Liu LF. Processing of topoisomerase I cleavable complexes into DNA damage by transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4181–4186. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.21.4181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lippert MJ, et al. Role for topoisomerase 1 in transcription-associated mutagenesis in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:698–703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012363108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanizawa A, Kohn KW, Pommier Y. Induction of cleavage in topoisomerase I c-DNA by topoisomerase I enzymes from calf thymus and wheat germ in the presence and absence of camptothecin. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5157–5166. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.22.5157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takashima H, et al. Mutation of TDP1, encoding a topoisomerase I-dependent DNA damage repair enzyme, in spinocerebellar ataxia with axonal neuropathy. Nat Genet. 2002;32:267–272. doi: 10.1038/ng987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirano R, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia with axonal neuropathy: consequence of a Tdp1 recessive neomorphic mutation? EMBO J. 2007;26:4732–4743. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cassier-Chauvat C, Fabre F. A similar defect in UV-induced mutagenesis conferred by the rad6 and rad18 mutations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat Res. 1991;254:247–253. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(91)90063-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Longtine MS, et al. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bellí G, Garí E, Aldea M, Herrero E. Functional analysis of yeast essential genes using a promoter-substitution cassette and the tetracycline-regulatable dual expression system. Yeast. 1998;14:1127–1138. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19980915)14:12<1127::AID-YEA300>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whelan WL, Gocke E, Manney TR. The CAN1 locus of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: fine-structure analysis and forward mutation rates. Genetics. 1979;91:35–51. doi: 10.1093/genetics/91.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lea DE, Coulson CA. The distribution of the numbers of mutants in bacterial populations. J Genet. 1949;49:264–285. doi: 10.1007/BF02986080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guglielmi B, Soutourina J, Esnault C, Werner M. TFIIS elongation factor and Mediator act in conjunction during transcription initiation in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:16062–16067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704534104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.