Summary

The eukaryotic nucleus houses a significant amount of information that is carefully ordered to ensure that genes can be transcribed as needed throughout development and differentiation. The genome is partitioned into regions containing functional transcription units, providing the means for the cell to selectively activate some, while keeping other regions of the genome silent. Over the last quarter of a century the structure of chromatin and how it is influenced by epigenetics has come into the forefront of modern biology. However, it has thus far failed to identify the mechanism by which individual genes or domains are selected for expression. Through covalent and structural modification of the DNA and chromatin proteins, epigenetics maintains both active and silent chromatin states. This is the “other” genetic code, often superseding that dictated by the nucleotide sequence. The nuclear matrix is rich in many of the factors that govern nuclear processes. It includes a host of unknown factors that may provide our first insight into the structural mechanism responsible for the genetic selectivity of a differentiating cell. This review will consider the nuclear matrix as an integral component of the epigenetic mechanism.

Keywords: potentiation, epigenetics, DNA methylation, histone modification, RNA-mediated silencing, nuclear matrix, gene regulation, epigenetic therapy

I. Introduction

Recent data mining of the 3.27 billion nucleotide base pairs of DNA that comprise the human genome, estimate our complement of genes above 24,000, coding for at least 35,000 transcripts (EMBL-EBI Ensembl, 2005). This significant amount of information has to be carefully ordered in the nucleus to ensure that genes can be transcribed as needed throughout development and differentiation. The majority of cell and tissue specific gene activity is controlled by DNA-sequence dependent forms of regulation mediated through molecular interactions at gene promoters and enhancers. There are additional mechanisms that modulate, if not supersede, transcriptional and post-transcriptional forms of regulation with a less-direct relationship to the DNA sequence.

Mechanisms that control the outcome of heritable gene activity without manipulating, or relying on the DNA sequence, are termed “epigenetic” (Russo et al, 1996). These forms of regulation shift the focus from enhancer/promoter interactions to those that generally impact the chromatin structure of a locus. They address whether a locus is in an “open” conformation enabling trans-acting factor access as necessary for transcription. A gene locus or chromatin domain that has acquired an “open” transcriptionally permissive conformation is “potentiated” (Kramer et al, 1998).

Epigenetic forms of regulation were first suggested in the late 1950s when McClintock’s group began their studies directed toward understanding how transposable elements regulate maize coat color (McClintock, 1958). During this same period, Brink defined “paramutation”, the expression of a heterozygotic allele heritably altered by exposure to the other allele (Brink, 1958a,b). The field blossomed with new studies pursuing the basis of mammalian X-inactivation (Ohno et al, 1959; Lyon, 1961) along with those using insect models targeted towards understanding imprinting (Crouse, 1960). This set the stage for chromatin structure’s steady progression into the spotlight.

The balance between activating factors and silencing factors dictates the transcriptional outcome. This has been considered the language overlaying that used by DNA-sequence dependent forms of regulation (Strahl and Allis, 2000). Cross-talk and reinforcement between each of the different epigenetic mechanisms enrich the lexicon regulating gene activation. What is thus far lacking, is the first word of the sentence, i.e., the crucial factor or process that sets potentiation in motion. Evidence has been accumulating that interactions with the nuclear matrix may be the first word, since the nuclear matrix appears to recruit many epigenetic factors (Stauffer et al, 2001; Yasui et al, 2002). However, we require a greater appreciation for syntax. For example, the timing of each spoken word impacts how the sentence is interpreted. It communicates whether silencing or activation proceeds. The latter setting the stage for the recruitment of the transcription machinery to a gene’s enhancer and promoter regions as requisite for initiation and elongation.

This review will examine the body of work that has contributed to our understanding of the importance of chromatin structure and epigenetics with regard to its control over the expression of our genome. Interactions with the nuclear matrix that provide the framework for the molecular interactions that mediate epigenetic regulation will be considered.

II. Chromatin structure

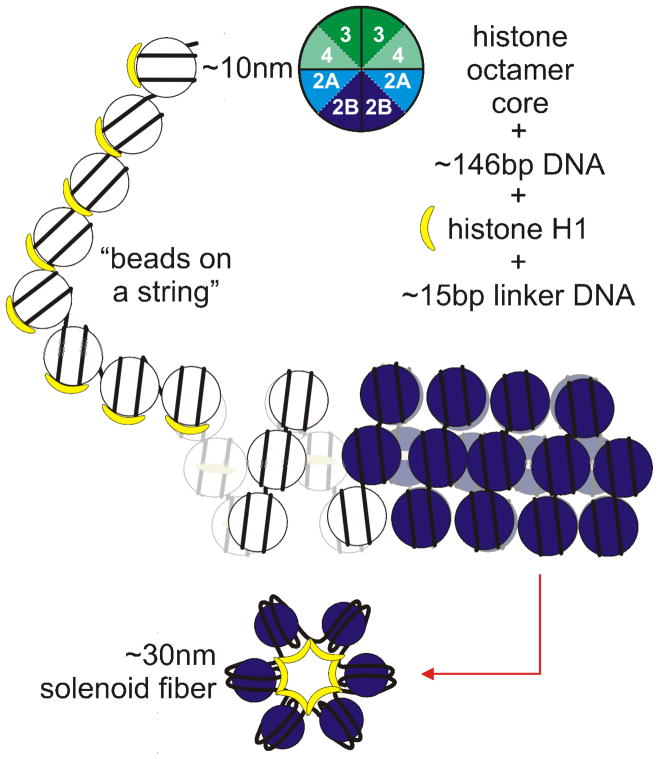

Within the eukaryotic nucleus DNA associates with a number of proteins to achieve a high degree of compaction (Daban, 2003; Daban, 2000). This compensates for the increased size of the genome in a fixed nuclear space (Vinogradov, 2005). One of the building blocks, the nucleosome, has been characterized at the atomic level (Richmond and Davey, 2003). Nucleosomal packaging presents an obstacle to transcription (reviewed in Struhl, 1999). It is comprised of 146 base pairs of supercoiled DNA wrapped approximately one and three quarter times around a histone octamer core of H2A, H2B, H3 and H4 dimers. Each adjacent nucleosome is linked by approximately 15 base pairs of linker DNA complexed with histone (H1) to yield, in vitro, the “beads on a string”, or 10nm chromatin fibre. These structures coil, forming an approximately 30 nm diameter “solenoid” (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The nucleosome is the fundamental unit of DNA organization in the eukaryotic nucleus.

Approximately 146 base pairs (bp) of DNA wraps 1.75 times around a histone octamer core composed of two of each of the H2A and H2B homodimers together with two H3–H4 dimers. Successive nucleosomes are linked by approximately 15 bp of DNA and the entire structure is stabilized associating with histone H1. In solution this arrangement forms the 10 nm “beads on a string” that is readily transcribed in the presence of all of the requisite trans-acting factors and transcription “machinery.” This form can be compacted by coiling into a solenoid form (~30 nm in diameter, in solution) that can be transcribed at basal levels. However, potentiation is a necessary transition from the compacted to the “beads on the string” conformation in order to allow higher degrees of transcription.

Heterochromatin are those transcriptionally silent chromosomal regions exhibiting higher levels of compaction. These structures are created and stabilized through a series of interactions with “heterochromatinizing” proteins such as heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) or members of the polycomb group (PcG) of proteins (reviewed in Craig, 2005). In this case, transacting factor access is mitigated by the effects of higher order chromatin structure. Less compacted regions of chromatin, termed “euchromatin,” are those regions of the chromosome that can be permissive to transcription when they have assumed the open-potentiated conformation requisite for transcription. This is orchestrated through a number of epigenetic and transcription-promoting factors. Potentiated chromatin was originally viewed as the 10 nm fibre, although it is now known that other higher order euchromatic structures can support basal levels of transcription (Georgel et al, 2003).

Although the mechanistic intricacies mediating potentiation remain to be delineated, a series of clues to the mechanism are provided by the recently described host of epigenetic and chromatin structure-altering modifications. The modifiers include enzymes that act on the DNA directly, e.g., DNA MethylTransferases (DNMTs) including those that act on histones; histone MethylTransferases (MTases) and de-methylases, ATP-dependent chromatin-remodelling complexes, Histone AcetylTranserases (HATs) and Histone De-ACetylases (HDACs), mi-RNAs, as well as interactions with nuclear matrix constituents.

III. DNA methylation

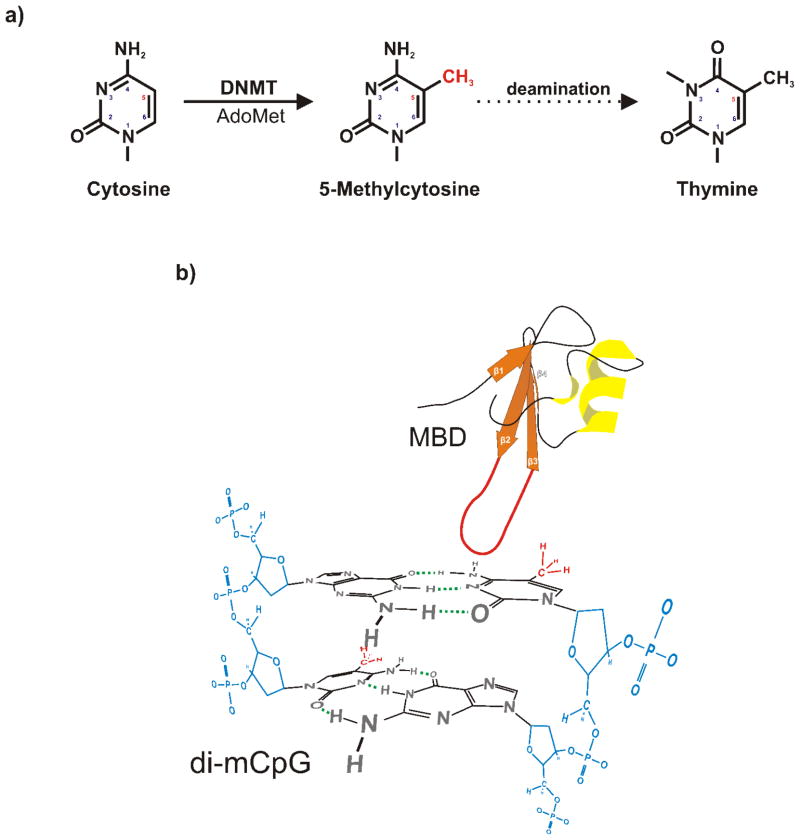

Through covalent modification, DNMTs attach a methyl group to cytosine residues at the carbon-5 position (Figure 2a). In mammals, genomic methylation is localized predominantly to CpG dinucleotides (Holliday and Pugh, 1975; Riggs, 1975), although other non-CpG motifs have been shown to be methylated (Tasheva and Roufa, 1994; Clark et al, 1995). Eukaryotic DNMTs can be grouped into two main classes based on their activity (Riggs, 1975), maintenance or de novo (reviewed in Chen and Li, 2004; Ponger and Li, 2005).

Figure 2. Genomic Methylation and silencing.

a) Cytosine can be methylated at the carbon-5 position by any number of DNA Methyltransferases (DMNTs) with S-adenosyl-L-methionine (AdoMet) co-factor. Once modified, 5-methylcytosine is highly labile and can be readily deaminated to thymine. This modification is mutagenic yielding C≡G →5mC≡G →T=G→T=A transition essentially ablating trans-factor recognition, silencing Alu elements and other invading DNA elements. b) The primary mechanism of genomic methylation-based silencing requires the recognition of symmetrically methylated CpG dinucleotides (di-mCpG). For example, MeCP2, recognizes and binds to methyl-CpG Binding Domains (MBD) excluding transcription promoting interactions. The MBD interacts with the modified bases in the major groove and several residues in the loop domain between the second and third β-sheets have been shown to be critical to methyl-CpG recognition. Methyl-residues are shown in red, DNA phosphodiester backbone in blue. The ribbon model was adapted (Wakefield et al, 1999; Khorasanizadeh, 2004).

Mammals possess five different DNA MethylTransferases, DNMT1, DNMT2, DNMT3a, 3b and 3L. Specific patterns of methylation are usually established in the early embryo by de novo MethylTransferases (MTases) DNMT3a and DNMT3b (Okano et al, 1999). DNMT3L has been shown to associate with DNMT3a or 3b and play an essential role in establishing parental imprints (Bourc’his et al, 2001; Hata et al, 2002; Webster et al, 2005) but possesses no catalytic activity (Aapola et al, 2001; Bourc’his et al, 2001). These patterns are perpetuated by the maintenance MTase DNMT1 after DNA replication. Lsh, a member of the SNF2 family of ATP-dependent helicases, is essential to maintaining genomic methylation (Dennis et al, 2001) in repetitive element rich regions (reviewed in Bourc’his and Bestor, 2002). DNMT2 is not-essential to mammalian methylation, as DNMT2 has only residual MTase activity in humans (Hermann et al, 2003). In addition, the corresponding targeted mouse ES cell knockout shows no change in the pattern of methylation (Okano et al, 1998). However, Drosophila DNMT2, plays an important role in non-CpG methylation (Kunert et al, 2003).

DNA methylation is usually associated with transcriptional repression. This is exemplified by the action of MeCP2 as shown in Figure 2b. This Methylation-sensitive chromatin protein binds via a specific methyl-CpG binding domain, MBD (Nan et al, 1993; Nan et al, 1996). The MBD recognizes symmetrically methylated CpG dinucleotides in the major groove (Rauch et al, 2005). Contact, critical to methyl-CpG recognition, is mediated by several residues in the loop domain between the second and third β-sheets (Free et al, 2001). Once bound, transcription is attenuated using a transcription repression domain to recruit mSin3A/HDAC, a nucleosome remodeller and histone de-acetylase (Deplus et al, 2002; Fuks et al, 2000; Fuks et al, 2001; Nan et al, 1998). MeCP2 can act in two different manners. First, by promoting histone de-acetylation, neighboring nucleosomes can be compacted to a silenced state. Second, by direct interaction with TFIIB, the formation of the pre-initiation complex can be inhibited (Wong and Privalsky, 1998).

Genomic methylation is also dependent on the methylation of a number of chromatin proteins (Fuks et al, 2002). For example, the amino-terminal of histone H3 can be methylated at lysine 9 (H3:K9) by Suv39-MTase. This promotes binding to members of the HP1 family of Heterochromatin Proteins (Nielsen et al, 2002) that are known to associate with yeast centromeric heterochromatin (Bannister et al, 2001). Failure to methylate H3:K9 can effect establishment, maintenance and inheritance of genomic methylation (Bannister et al, 2001; Lachner et al, 2001; Peters et al, 2001).

Sixty to ninety percent of vertebrate CpGs are methylated. The remaining non-methylated CpGs are commonly associated with gene promoters of constitutively expressed, housekeeping genes (Antequera and Bird, 1993). They are hypomethylated CpG islands defined as ~100 bp C≡G rich regions, i.e. >55%, providing a universal control mechanism to ensure constitutive expression of housekeeping genes (Bird, 1986).

In mammals, principally primates, the Alu family of short interspersed repetitive elements are typically CpG rich. These transposable elements are often regarded as parasitic elements in genomes and contribute as many as one third of the CpGs in the genome (Schmid, 1991). In contrast to CpG islands, Alu elements are usually highly methylated to constitutively silence the endogenous RNA Polymerase III promoters embedded within these elements (Li et al, 2002). This is regarded as a genomic defense mechanism against transposable elements and viral sequences. Regulatory cis-elements in the Pol III promoters are silenced by methyl-cytosine deamination that transitions 5mC≡G to T=A (Rideout et al, 1990). Thus, methylation based genomic silencing can be reinforced through histone modification and by mutating the invading sequences.

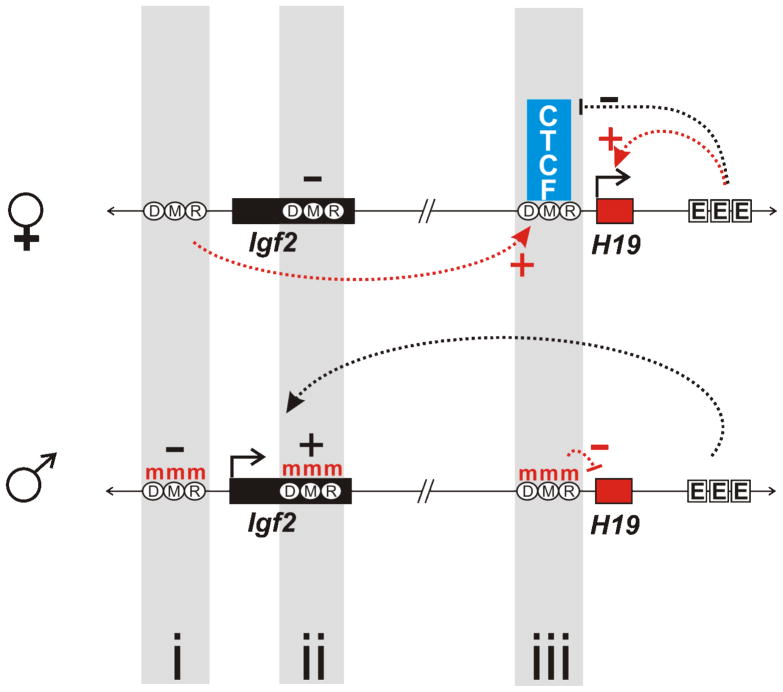

Genomic imprinting, the mono-allelic pattern of expression passed from parent to offspring, is largely controlled by methylation. The mouse Igf2-H19 locus on chromosome 7, shown in Figure 3, is a well characterized model of imprinting. H19 is expressed from the maternal allele and Igf2 from the paternal allele. Expression is dictated by the methylation status of three DMRs, Differentially Methylated Regions. The maternal allele is not methylated promoting the binding of the CTCF boundary element at the DMR, just upstream of H19 (Figure 3 top, region iii). This restricts the activity of the H19 enhancer. In comparison, the paternal allele (Figure 3 bottom) is heavily methylated at all DMRs (Figure 3, regions i, ii, iii). Thus CTCF cannot bind and the enhancer (Figure 3, EEE) can now interact with the Igf2 gene. Non-methylated DMR i, acts as an activator that likely loops out to physically interact with DMR iii to drive maternal H19 expression (reviewed in Kato and Sasaki, 2005). This interaction may be mediated by CTCF binding to unmethylated DMR iii. New evidence suggests that long-range chromatin looping mediated through the DMRs may position the transcribing alleles in active chromosome territory regions to facilitate their transcription (Murrell et al, 2004). DMR ii, located in intron 6 of Igf2, acts as a methylation-sensitive repressor. Paternal expression of Igf2 is promoted through its interaction in the unmethylated state with the downstream enhancer (EEE; Bell and Felsenfeld, 2000; Srivastava et al, 2000).

Figure 3. Genomic imprinting is governed by DNA methylation.

Genomic methylation plays an essential role in genomic imprinting, the mono-allelic expression of specific loci. In mice, the Igf2-H19 locus provides a well-characterized model where differential methylation between alleles at various DMRs (differentially methylated regions) mediates the imprint. The unmethylated maternal allele, enables the CTCF boundary element to bind, restricting the activity of the upstream enhancers (EEE) on H19. In contrast, the paternal allele is heavily methylated at all three DMRs (red m’s). When unmethylated, DMRi, acts as an activator and could loop to physically interact with DMRiii to drive maternal H19 expression. This interaction may be mediated by CTCF, binding the unmethylated downstream DMR. DMRii acts as a methylation-sensitive repressor within intron 6 of Igf2. Upon interacting with the downstream enhancers unmethylated DMRii promotes paternal Igf2 expression.

At the zygotic stage, most mammalian genomes are demethylated with the exception of sheep, where the degree of zygotic methylation loss is greatly decreased (Young and Beaujean, 2004). Methylation is then restored de novo at gastrulation (Monk et al, 1987). The mechanism of genome-wide demethylation has yet to be determined. Passive and progressive demethylation by down regulating maintenance DNMTs proceeded by successive rounds of replication and division has been proposed (Matsuo et al, 1998; Hsieh, 1999, 2000). However, this process would be exceedingly slow to account for the scale of change that occurs within a single day of development (Hajkova et al, 2002). Alternatively, active mechanisms of demethylation, employing DNA excision and repair mechanisms have also been implicated. For example, consider the expression of 5-methylcytosine DNA glycosylase that removes methyl-cytosine, cleaving the sugar backbone thus signaling to the DNA damage/repair mechanisms to replace the cleaved base for a cytosine. In vitro, over-expression demethylated the promoter of a stably co-transfected hormone-responsive reporter gene but failed to affect the level of genome-wide methylation (Zhu et al, 2001). This enzyme and the chicken homologue (Jost and Jost, 1994) preferentially utilize a hemi-methylated substrate. Accordingly genome-wide demethylation would require a concomitant decrease in DNMT activity. In essence, the active mechanism is dependent on the passive loss of DNA methylation. While the above have provided testable models, additional evidence of how re-activation of a methylated region of silenced DNA can be achieved is still lacking. However, the absence of an active mechanism would ensure that silent states are inherited as cells divide then maintained once terminal differentiation is achieved.

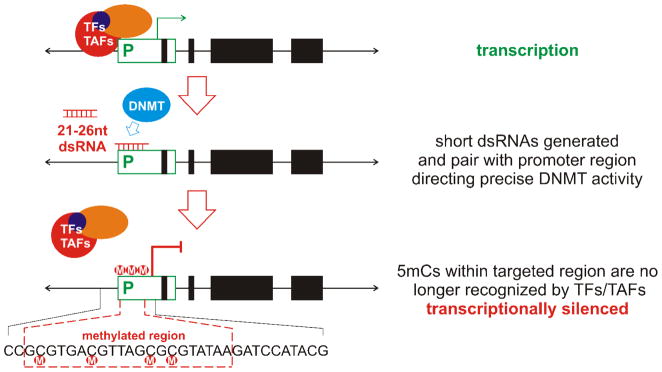

This raises the question what is the mechanism that directs or signals de novo genomic methylation? It has been proposed that paired DNA repeats (Hsieh and Fire, 2000) or spans of unpaired DNA that form unusual secondary structures, e.g., cruciforms or hairpins (Smith et al, 1991; Chen et al, 1995; Laayoun and Smith, 1995; Kho et al, 1998) could provide recognition sequences for de novo DNMTs, thus directing methylation to a specific locus. Recently, the recognition of multiple short A=T tracts in the minor groove have been implicated as triggers when establishing methylation in Neurospora crassa (Tamaru and Selker, 2003). Interestingly, plants utilize an RNA-mediated mechanism (Wassenegger et al, 1994). As shown in Figure 4, RNA-dependent DNA Methylation uses a ~21–26 nt, double stranded RNA (dsRNA; Mette et al, 2000; Sijen et al, 2001; Hamilton et al, 2002; Zilberman et al, 2003). These short RNase III-like nuclease processed dsRNAs, target and pair with specific regions of DNA e.g., promoters, (Mette et al, 2000; Jones et al, 2001; Sijen et al, 2001; Aufsatz et al, 2002) leading to the methylation of all cytosines contained within that processed dsRNA. Unlike X-ist RNA targeting in mammalian X-inactivation, this process is specific and does not spread. Only those cytosines within the short RNA are methylated (Jones et al, 2001; Aufsatz et al, 2002) to block the molecular recognition of cis-regulatory promoter elements silencing transcription.

Figure 4. RNA-dependent DNA methylation RdDM.

A ~21–26 nt, double stranded RNA targets specific regions, e.g., promoters, for localized methylation of all cytosines. Only those cytosines within the short RNA are methylated to block the molecular recognition of cis-regulatory promoter elements silencing transcription. Unlike X-ist RNA targeting in mammalian X-inactivation, this process is specific and does not spread along a larger domain.

IV. Post-translational histone modification

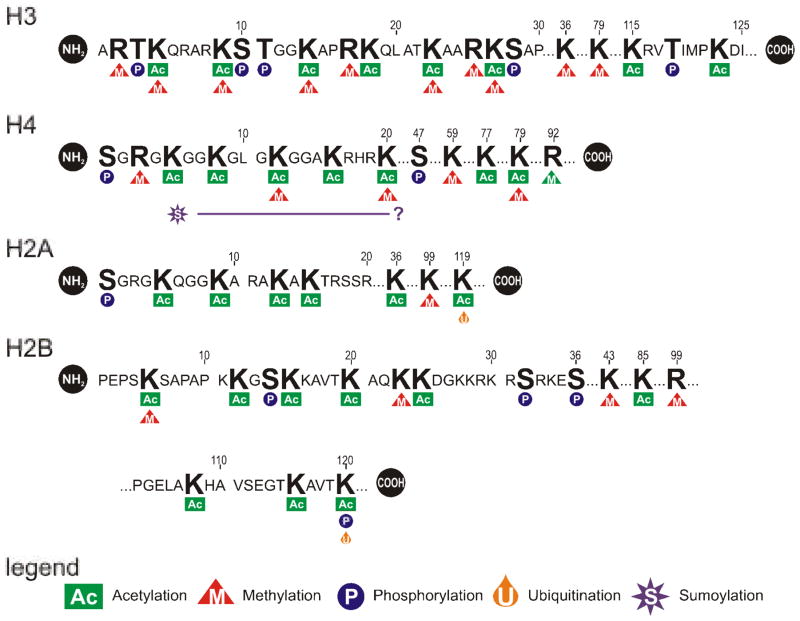

Histones are a dynamic substrate for post-translational modification at key amino acid residues. Modifications include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, glycosylation, ADP-ribosylation, ubiquitination and sumoylation. The sites of core histone modification are summarized in Figure 5. Each can signal, or results from, a host of cell processes including DNA repair, gene transcription, chromatin activation, silencing, heterochromatin formation, replication and/or recombination. Phosphorylation and ADP-ribosylation are more commonly associated with DNA repair mechanisms (de la Cruz et al, 2005; Lowndes and Toh, 2005) but can impact transcription. Sumoylation and ubiquitination are two related protein modification pathways associated with protein trafficking and degradation. Interestingly, sumoylation of the amino-terminus of H4 has been associated with transcriptionally quiescent DNA (Shiio and Eisenman, 2003; Gill, 2004). Detailed reviews of the various histone modifications have been presented (Fischle et al, 2003a; Lachner et al, 2003; Gill, 2004; Khorasanizadeh, 2004; de la Cruz et al, 2005; Lowndes and Toh, 2005). The sections that follow will focus on acetylation and methylation that are well characterized and known to change with transcriptional status.

Figure 5. Post-translational histone modifications.

The covalent modification of histones can serve to signal any number of cellular and genetic processes. This has been reviewed by (Fischle et al, 2003a; Lachner et al, 2003; Gill, 2004; Khorasanizadeh, 2004; de la Cruz et al, 2005; Lowndes and Toh, 2005), and (Upstate, Waltham, MA, USA). The effect is varied, depending on the residue and how it is modified. Lysines are subject to acetylation, methylation, ubiquitination and sumoylation, arginine to methylation while serine and tyrosine can be phosphorylated. Acetylation of H3 and H4 lysines are generally associated with transcriptionally active DNA, e.g. H3:K4, K9, K27. In contast, sumoylation of H4 lysine is associated with transcriptional repression, but the specific residues have not yet been identified. Arginine and lysine can be mono-, di- and tri-methylated associated with both active and silent chromatin. Specific modifications seldom exist to the exclusion of the other. In concert they form a code imparting silencing or activation.

A. Acetylation

Heritable states of active and silent chromatin can be achieved through various post-translational modifications to amino- and carboxy- histone termini. Acetylation and methylation of key lysine residues in the amino-termini of histones H3 and H4 are well characterized. Acetylation of the H3 and H4 lysines employ large Histone AcetylTransferase domain complexes such as GCN5. Transcription is generally facilitated by these modifications in two manners. First, lysine acetylation increases steric hindrance between adjacent nucleosomes, thereby disrupting higher order chromatin folding (Fry and Peterson, 2001). The degree of order is substantially lessened upon hyperacetylation, when at least six of the H3 and H4 lysine residues are acetylated. In conjunction with other factors, this maintains a potentiated open chromatin state enabling trans-acting factors to interact with cis-regulatory elements. Secondly, these acetylated residues are recognized by the bromodomains of transcription-promoting factors such as TFIID of the preinitiation complex as well as ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes (Agalioti et al, 2002).

Histone de-acetylases (HDACs) can reverse these modifications. They are divided into three groups depending on their similarity to those originally cloned from yeast and whether they require NAD+ (reviewed in de Ruijter et al, 2003). Silencing by histone methylation usually accompanies deacetylation as exemplified by MT1, metallothionein I. For example, DNMT3a/b methylates the MT1 promoter at several sites becoming substrates for MeCP2. This recruits HDAC1 to the promoter and de-acetylates several key histones effectively silencing the MT1 promoter (Beisel et al, 2002). This class of associations between HDACs and other chromatin remodelers is termed NuRDs (Nucleosome Remodelling and histone De-acetylases).

B. Methylation

While acetylation generally correlates with transcriptionally competent chromatin, methylation lacks that specificity. Both lysine or arginine residues can be methylated. The extent of the modification and the position of the residue on the histone tail, promotes either active or silent chromatin states. For example, the methylation of H3:K9 and H3:K27 in Drosophila promotes chromodomain binding of HP1 and Polycomb protein to heritably silence spans of chromatin (Fischle et al, 2003b). In contrast, the interaction of RNA Polymerase II with methylated H3:K4 can be associated with transcriptional activation (Ng et al, 2003). Methylation of H3:K4, H3:K9 and H4:K20 by histone MTase Ash1 provides substrates for Brm, a SWI/SNF family homologue in Drosophila. In this case nucleosomes localized to several cis-regulatory trithorax response elements are remodeled (Beisel et al, 2002) thereby activating the Ubx promoter.

Unlike direct nucleotide methylation, recent studies have identified two novel histone de-methylation pathways. These include PAD4, PeptidylArginine Deiminase 4 and LSD1, Lysine Specific Demethylase 1. For example, PAD4 has been identified as catalyzing the deimination of arginine residues in humans. This is achieved by converting methylated H3:R17 and H4:R3 to citrulline. In turn this down regulates the transcription of an oestrogen-responsive gene (Wang et al, 2004). In comparison, using the FAD cofactor, yeast LSD1 directly demethylates H3:lys4. This leads to transcriptional repression (Shi et al, 2004).

V. ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling

Several ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling processes are mediated by large multi-subunit helicase containing complexes. These include SWI/SNF (SWItch/Sucrose Non-Fermenting helicases), ISWI (Imitation SWItch, nucleosome remodelers) and NuRD. By altering nucleo-histone interactions as well as protein-protein interactions these complexes can both modulate silencing as well as maintain open chromatin structures.

This group of ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers were initially characterized as part of an ~2 MDa, 11-subunit complex of proteins in yeast. Homologues have since been identified throughout eukaryotes (Becker and Horz, 2002; Natarajan et al, 1999; Pollard and Peterson, 1998). While SWI/SNF have been shown to act on genes independent of other factors (Natarajan et al, 1999), they usually form complexes with HATs such as SAGA and trans-activators like GAL-4 (VP16 and AH). In this manner they can cooperatively act to remodel chromatin and promote transcription (Neely et al, 1999; Yudkovsky et al, 1999). The order in which these large remodeling complexes are formed is still a matter of intense debate. For example, there is evidence suggesting that SWI/SNF and HATs are recruited by transcription factors, transcription associated factors and the pre-initiation complex, prior to associating with DNA (Soutoglou and Talianidis, 2002). Other models suggest that SWI/SNF remodeling must occur first, in order to enable additional factors to interact with the DNA (Peterson, 2000; Peterson and Logie, 2000; Peterson and Workman, 2000).

While some members of this family of enzymes repress transcription, e.g., NuRD (Wade et al, 1999), the majority of these factors activate transcription. This is achieved in an ATP-dependent manner by twisting the nucleosome thereby disrupting the association between DNA and histones in a ubiquitin independent manner (Flaus and Owen-Hughes, 2003 and reviewed Fry and Peterson, 2001). By disrupting nucleo-protein association at promoters or enhancers these regions become histone free and available to bind the necessary trans-acting factors to effect transcription. In addition to their role during transcription, chromatin remodellers are recruited to sites of replication, facilitating the re-association of epigenetic marks to ensure the heritability of the chromatin states (Poot et al, 2004, 2005).

VI. RNA-mediated regulation

The last decade has revolutionized how we view the role of RNA in the cell. It is well-documented that X chromosome dosage compensation in mammals is mediated by RNA-directed silencing. The Xist RNA coats and directs the inactivation (Penny et al, 1996; Marahrens et al, 1997) of the specific chromosome from which it is expressed. Different regions of this ~70 kb transcript regulate association to the X chromosome, as well as its ability to signal downstream silencing (Wutz et al, 2002). It is thought that several repeating stem-loops form in the 5′ region of the transcript to serve as binding sites for proteins that may direct the myriad of epigenetic modifications required to silence the inactive copy of the X chromosome (Brown and Baldry, 1996; Wutz et al, 2002). These include, methylation of H3:K9 and K27 by several histone MTases (Okamoto et al, 2004; Rougeulle et al, 2004).

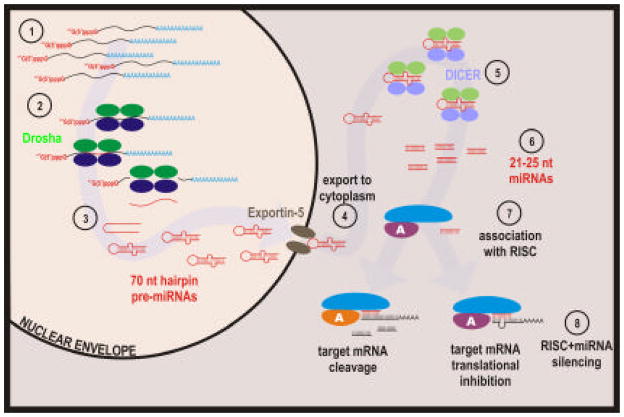

No longer recognized as just an intermediate as DNA is decoded to protein, RNAs are now also appreciated as molecules of regulatory function from plant to man. RNA-mediated gene silencing, termed RNA interference (RNAi) in animals uses signaled transcript degradation or translational inhibition by targeted single-stranded 21–25 nt micro RNA (miRNA) molecules (Figure 6). Interestingly, genes coding for miRNAs are found throughout the genome (Lau et al, 2001; Lagos-Quintana et al, 2001; Lee and Ambros, 2001; Mourelatos et al, 2002) and when initially transcribed bear a 5′ cap structure and poly(A)-tail as shown in Figure 6.1 (Lee et al, 2004). Functional miRNAs are derived from a series of maturation events catalyzed by various RNase III complexes. Subsequent to transcription, 70-nt nuclear hairpin pre-miRNAs are generated by Drosha-DGCR8 (Figure 6.2.3; Lee et al, 2003; Han et al, 2004). This dictates specificity and relative silencing ability (Lee et al, 2003; Lund et al, 2004). After transitioning to the cytoplasm Dicer cleaves the pre-miRNAs to yield ~22 nt mature miRNAs (Bernstein et al, 2001; Grishok et al, 2001; Hutvagner et al, 2001; Ketting et al, 2001; Knight and Bass, 2001). To specifically target transcripts for down-regulation (Hammond et al, 2000, 2001) these short molecules then pair with a large protein complex including members of the Argonaut family, termed RISC (RNA-Induced Silencing Complex) as summarized in Figure 6.7, 8. Down-regulation is achieved by either cleavage or translational inhibition of the target mRNA as determined by the type of Argonaut protein that is part of that RISC and the level complementation between the miRNA sequence and its target mRNA (reviewed in Tang, 2005).

Figure 6. RNA-mediated silencing.

Post-transcriptional RNA-mediated silencing termed RNAi, RNA interference is a multi-step mechanism. It begins in the nucleus, with expression of 5′ capped, polyadenylated transcripts that are ubiquitous throughout the genome (1). These are processed in the nucleus by an RNaseIII-like complex including Drosha (2) that cleaves the primary transcripts into ~70 nucleotide hairpin pre-micro RNAs (pre-miRNAs; 3) that are exported to the cytoplasm by Exportin 5, a nuclear pore protein (4). Upon reaching the cytoplasm, these pre-miRNAs are further processed by Dicer (5), another RNaseIII family member, to produce 21–25nt miRNAs (6). Silencing is achieved upon association of these miRNAs with the RNA-Induced Silencing Complex, RISC (7). RISC is a heterogeneous complex of additional RNaseIII-like factors as well as members of the Argonaut family. This association empowers RISC to down regulate a specific message by either targeted mRNA cleavage or targeted mRNA translational inhibition (8). Silencing efficiency is dependent upon the level of miRNA and target identity as well as the type of Argonaut protein that is associated with the RISC. The greater the level of identity drives the mechanism towards cleavage and degradation as opposed to translational repression of the target.

RNAi impacts numerous developmental pathways. Members include Lin-4 (Lee et al, 1993; Wightman et al, 1993) and let-7 (Reinhart et al, 2000; Slack et al, 2000). They were the first miRNAs discovered and shown to regulate developmental and morphogenetic timing in the nematode caenorhabditis elegans. Interesting but still controversial, several miRNA-like transcripts have been identified in mature human sperm (Ostermeier et al, 2005) that could aid in gene regulation in the early embryo and imprinting (Krawetz, 2005).

In plants and fungi, an RNA-dependent RNA Poymerase-based (RdRP) amplification mechanism that reinforces and spreads silencing has been identified (reviewed in Caplen, 2004). A similar RdRP mechanism, has been shown to participate in the establishment of centromeric heterochromatin in budding yeast (Motamedi et al, 2004; Sugiyama et al, 2005). In this case, RNAs complimentary to the centromeric repeats are processed by the RNA-induced Initiation of Transcriptional gene Silencing complex (RITS). RITS contains an RdRP (Rdp1), Dicer and Chp1, a heterochromatin-associated protein (Verdel et al, 2004). To permanently silence the centromeric DNA the RITS complex then recruits a number of ATP-mediated chromatin remodelers (e.g., Swi6), heterochromatin assembly proteins (e.g., HP1), as well as the histone MTases Clr4 and Suv39H that methylate H3:K9, (Motamedi et al, 2004; Noma et al, 2004; Sugiyama et al, 2005).

VII. The nuclear matrix

The manner in which chromatin and its modifying factors are organized within the cell nucleus is a layer of complexity whose role in gene regulation is becoming apparent. Individual chromosomes occupy distinct territories within the cell nucleus with transcriptionally active segments generally localized to the periphery and transcriptionally inert regions localizing to the center of the territories (Kurz et al, 1996; Dietzel et al, 1999). While delimiting each chromosome in the interphase nucleus, territories appear as static regions. Recent evidence has emerged that transcriptionally active regions of DNA can loop out of chromosome territories (Chambeyron and Bickmore, 2004; Chambeyron et al, 2005; Spilianakis et al, 2005) to interact with the domains of co-regulated genes on other chromosomes (Spilianakis et al, 2005). Chromatin is organized by attachment or association to a network of proteins including ribonucleo-proteins within the nucleus that are interior to the nuclear envelope, termed the nuclear matrix (Cremer et al, 2000). The very existence of the nuclear matrix itself has been a great source of contention, as many of the studies conducted in the field use biochemically fractionated cell preparations that preclude examination of in vivo function (Mirkovitch et al, 1984; Balasubramaniam and Oleinick, 1995). However, over time two paradigms of the nuclear matrix have emerged.

The first paradigm regards the nuclear matrix as a static structure. Chromatin is segmented into transcriptional domains ranging from 50–200 kb in length. The second paradigm includes both a structural and dynamic or transient component. The latter views the composition of the nuclear matrix as transient, reflecting the developmental competence of the cell. Just as cells undergoing differentiation utilize different promoters, enhancers and “epigenetic terms” to specify genetic fates, so too are different factors mobilized to their respective nuclear matricies. These are reflective of the types of interaction necessary to produce the intended outcome (Samuel et al, 1997a,b; Yudkovsky et al, 1999; Alvarez et al, 2000; Kontaraki et al, 2000; Vassetzky et al, 2000; Spencer and Davie, 2001; Sun et al, 2001; Beisel et al, 2002; Soutoglou and Talianidis, 2002).

A. Matrix attachment regions

Nuclear matrix association is mediated by Matrix Attachment Regions, (MARs), which anchor chromatin to the nuclear matrix and shield domains from neighboring enhancers and the silencing effects of neighboring chromosomal regions (McKnight et al, 1992; Namciu et al, 1998; Martins and Krawetz, 2004). While these and other roles of nuclear matrix-DNA interaction have been scrutinized (Bode et al, 2000), the exact nature of the association and its mechanism remain to be fully characterized.

The few examples of characterized MARs indicate that they vary in size ranging from 100 – 1000 base pairs in length and in primary sequence. Several “families” of matrix associating DNA motifs have been described in the literature (Singh et al, 1997). These include AT-rich spans, GT-rich spans, topoimerase II binding sites, regions of kinked and curved DNA secondary structures, as well as origins of replication (Kramer and Krawetz, 1995). These motifs have provided some predictive insight and several algorithms have been created to search for MARs (Benham et al, 1997; Singh et al, 1997; Bode et al, 2000; Rogozin et al, 2000; Engel et al, 2001; Frisch et al, 2002). However, these motifs do not define MARs per se. That is, not every AT-rich span will be associated with the nuclear matrix. Accordingly, experimental confirmation to validate binding to the nuclear matrix of a predicted MAR is required (Mielke et al, 1990; Kramer and Krawetz, 1995; Kramer et al, 1996).

The positioning of MARs with respect to genes also varies greatly. For example, the chicken lysozyme 5′ MAR is located within the distal upstream enhancer (Bonifer, 1999). Other gene systems like the human protamine locus have MARs at the boundaries of its DNase I-sensitive domain (Kramer et al, 1996). These regions likely impart an insulative function to the locus since their deletion subjects the locus to position effects (Martins and Krawetz, 2004). This appears recapitulated in human 3′ MAR mutations (Kramer et al, 1997).

B. DNA-Nuclear matrix interactions

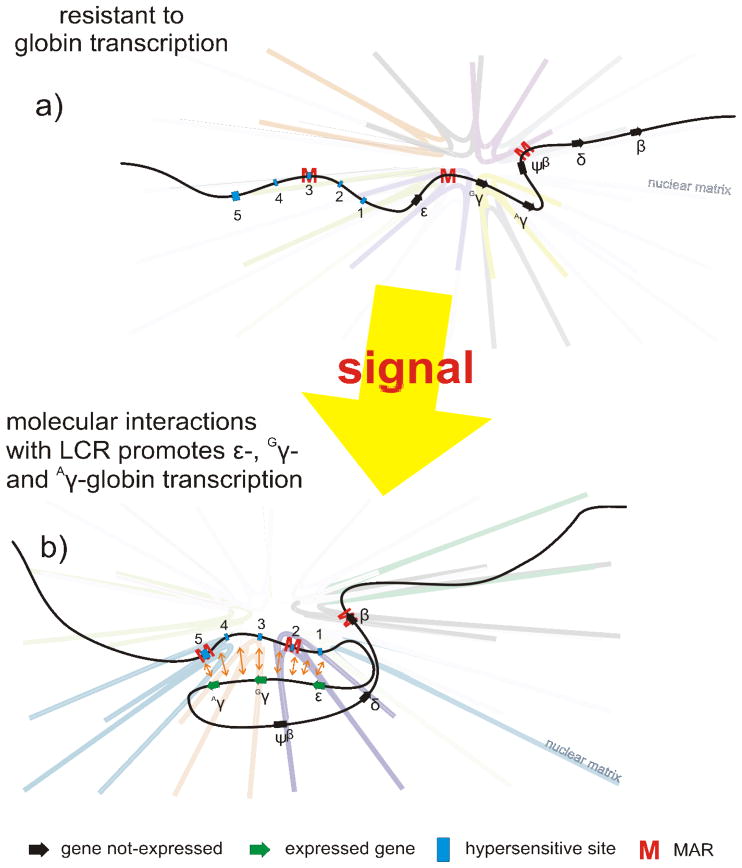

MARs do not always bind the nuclear matrix in a constitutive fashion. Just as the composition of the nuclear matrix is transient, so too is their association, often reflecting the differentiative state (Goetze et al, 2005; Ostermeier et al, 2003). This has been confirmed by the stable transfection of tandem arrays of somatic MARs. Only one was used at any given time. Accordingly, MARs are used in a selective and dynamic manner (Heng et al, 2004). This is also evident at the human β-globin cluster shown in Figure 7, where changes in nuclear matrix association vary directly with the temporal expression of the members of the locus (Ostermeier et al, 2003). In non-expressing cells, the pattern of binding, tethers the locus to the matrix preventing long range chromatin interactions between the locus control region and the various gene promoters. The cis sequence binding pattern and tethering to the nuclear matrix changes in cells that express ε, Gγ and Aγ-globins. This provided direct evidence of nuclear matrix association mediating long range looping-based interactions that constitute an “active chromatin hub” (de Laat and Grosveld, 2003).

Figure 7. Nuclear matrix association mediates molecular interactions that regulate transcription.

The human β-globin cluster is composed of five genes that are temporally regulated from embryo to adult. The cluster is regulated through LCR mediated interactions localized by five DNase I hypersensitive sites labeled 1–5. Nuclear matrix association varies directly with the temporal expression of the members of the locus. a) In non-expressing cells, the pattern of binding tethers the locus to the matrix, preventing long range chromatin interactions between the locus control region and the various gene promoters. b) The cis sequence binding pattern and tethering to the nuclear matrix changes in cells that express ε, Gγ and Aγ-globins coincident with long range looping-based interactions that constitute an “active chromatin hub”.

Chromosomal looping has also been shown to be critical for the expression of co-ordinately expressed multigene loci such as the HOX gene cluster, the imprinted Igf2-H19 locus (Murrell et al, 2004) as well as the interferon-γ (Infγ) and the T-helper cell (TH) 2 cytokines (interleukins (Il) 4, 5 and 13) loci that reside on chromosomes 10 and 11, respectively. The HoxB cluster was shown to loop outside of its chromosome territory in response to retinoic acid stimulation of mouse ES cells (Chambeyron and Bickmore, 2004) as well as in vivo, during embryonic development (Chambeyron et al, 2005). Loci guiding the differentiation of naïve murine CD4+ T-cells to T H1 or T H2 fates reside on different chromosomes. In naïve cells, regions from the Infg (a TH1 marker) loop out of their chromosome territory and interact with DNase I hypersensitive sites from the Il4-Il5-Il13 locus. Upon differentiation into either the TH1 or TH2 fate, this interaction is lost (Spilianakis et al, 2005) and the loci are alternatively expressed. This is the first example of an active chromatin hub formed through inter-chromosomal interactions. Thus far a mechanism for these intra- and inter-chromosomal interactions has not been established, but it is tempting to postulate an involvement of nuclear matrix association in a manner similar to that evident at the β-globin locus (Ostermeier et al, 2003).

Examination of both ribosomal (rDNA and 5S) and somatic (c-myc and keratin) genes in developing Xenopus embryos revealed specific interactions with the nuclear matrix that appeared to parallel changes in chromatin (appearance of DNase I hypersensitive sites) following genomic activation after the mid-blastula transition (Vassetzky et al, 2000). This suggested that transcription may be facilitated by changes in nuclear matrix association. Confirmation in single-copy gene systems is required to establish generality of this mechanism.

C. Nuclear matrix proteins

Several proteomic strategies have been employed in an attempt to identify and characterize the constituents of the nuclear matrix (Samuel et al, 1997b). Thus far over 400 nuclear matrix proteins have been archived in the Nuclear Matrix Protein database (Mika and Rost, 2005). The list includes structural proteins (see De Carcer et al, 1995; Malone et al, 1999) such as the lamins (Sepp-Lorenzino et al, 1989; Yam et al, 2002) as well as a number of transcription factors (Chatterjee and Fisher, 2002; Dworetzky et al, 1992; Guerrero-Santoro et al, 2004; He et al, 1994; Tang et al, 1998). One is left with the impression of substantial heterogeneity that is likely reflective of cell type or pathological state (Oesterreich et al, 1997). Nevertheless, significant advances have been made towards understanding how some nuclear matrix constituent proteins including SATB1 and CHMP1 regulate specific genic domains.

SATB1 is a protein that binds AT-rich base-unpairing regions of supercoiled DNA (Kohwi-Shigematsu and Kohwi, 1990; Dickinson et al, 1997) associated with MARs in numerous genes. These include the T-cell differentiation genes, e.g., Ig-μH enhancer (Alvarez et al, 2000) and IL-2Rα (Yasui et al, 2002). The critical role of SATB1 in T-cell differentiation was clearly established in the knockout model. SATB1−/− mice fail to produce the appropriate distribution of terminally differentiated T-cell fates observed in their wild-type counterparts (Alvarez et al, 2000). Interestingly, SATB1 impacts global T-cell gene expression by affecting the long range chromatin structure of a number of differentiation associated genes. This is accomplished by assembling a matrix, i.e., network that provides a “meeting place” for a number of chromatin remodeling complexes. These include Mi2-NuRD, ISWI, pARP, and several HDACs (Yasui et al, 2002). The interaction of SATB1 with its target DNA serves to physically recruit the gene to the nuclear matrix laden with factors that effect structural silencing. This process may be mediated through a nuclear matrix targeting signal (Seo et al, 2005). The subnuclear localization peptide sequence is unique, bearing no sequence similarity to known signals (Barseguian et al, 2002; Djabali and Christiano, 2004; Huang et al, 2004; Seo et al, 2005; Sierra et al, 2004; Telfer et al, 2004; Vradii et al, 2005).

Human CHMP1 has two isoforms that differ in size, the larger localizing to the nuclear matrix. When over expressed, CHMP1 accumulates throughout the nucleus forming foci of chromatin condensation that ultimately lead to late S-phase cell cycle arrest. These foci recruit and encapsulate chromatin silencers like Polycomb Group proteins (PcG) BMI1 and Polycomb2 (Stauffer et al, 2001). PcG proteins “fix” developmental decisions by silencing homeotic and other genes no longer required for differentiation. A heritable silencing is achieved through targeted deacetylation and methylation of histone tails (reviewed in Gil et al, 2005).

VIII. Clinical implications and conclusions

The orchestration of factors necessary to promote and ensure the correct transcription of any locus in the genome is complex. Epigenetic events that dictate the heritability of chromatin states interplay with domain potentiating factors that reside in the nuclear matrix. Appreciating the complexity in these interactions provides a means to better understand how genetic and therefore cellular fates are specified, presents a new prospective. This is clearly evident in cancer genetics.

With age, there is an increase in methylated CpG islands at gene promoters. This is thought to contribute to the silencing of tumour suppressors (Shibata et al, 2002; Wong et al, 2002; Kawaguchi et al, 2004; Breault et al, 2005). However this increase takes place within the context of an overall net loss in genomic methylation with age (Wilson and Jones, 1983; Richardson, 2002). Given how epigenetic marks are reinforced and how processes like methylation impact chromatin dynamics, the net loss of methylation could lead to chromosomal instabilities, loss of heterozygocity or loss of imprinting at some loci. In turn, this opens the door to autoimmune and metabolic disorders as well as any number of carcinomas (Wilson and Jones, 1983; Richardson, 2002; Schulz et al, 2002; Shibata et al, 2002; Wong et al, 2002; Kawaguchi et al, 2004; Breault et al, 2005; Nakagawa et al, 2005; Park et al, 2005). This is further compounded in scenarios where other known tumor suppressors are mutated or in individuals who are heterozygous for a mutation (Park et al, 2005), providing a novel means to satisfy Knudson’s two-hit hypothesis (Jones and Laird, 1999).

A number of pathologies that result from mutations or the misregulation of genes coding for DNMTs, ATP-dependent chromatin remodellers and heterochromatin assembly proteins have also been identified. These include the DNMT3b mutation (Hansen et al, 1999; Okano et al, 1999) that gives rise to ICF (Immunodeficiency, Centromeric region instability and Facial anomalies), the hSNF5 ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler mutation (Vries et al, 2005), that gives rise to malignant rhabdoid tumours and the series of MeCP2 germline mutations (Amir et al, 1999; Amir and Zoghbi, 2000) that give rise to Rett syndrome, an X-linked disorder presenting as mental retardation.

Each of these alterations presents a series of targets for therapeutic intervention. The problem that remains is one of specificity. Many of the small chemical agents that are currently known to inhibit histone methylation or HDACs lack the specificity to act on a single factor. Accordingly, the cure may be worse than the disease as the potential to de-repress a number of other unrelated genes and transposable elements is introduced. Clinical trials are currently underway using a coupled therapeutic approach. This includes a number of histone methylation and HDAC inhibitors along with chemotherapeutic, immunotherapeutic and interferon-based therapies (reviewed in Egger et al, 2004). Considering the synergism, a customized combinatorial approach may prove the most efficacious.

The assemblage of factors and processes necessary to drive transcription in a cell represents a fine tuned symphony. The cell requires mechanisms to select particular gene loci in a temporally and spatially-specific manner. The nuclear matrix may provide the structural framework and network of factors to potentiate and propagate chromatin structures that will facilitate transcription (Figure 7b). The cell also requires other mechanisms to permanently silence genes whose activity is no longer required or would otherwise be detrimental to a differentiated cell. Understanding the epigenetic and genetic codes that the cell uses to tailor its transcription program to that individual cell at that point in its development is a necessary first step to harnessing our genetic fates. Armed with this understanding and our understanding of how other cellular processes mitigate each form of regulation is the crucial step in making forms of genetic or epigenetic therapy a reality.

From left to right: Yi Lu, Adrian E. Platts, Stephen A. Krawetz, Amelia Quayla, Rui Pires Martins, Jodi Gardner and Robert Goodrich

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NICHD grant HD36512 to SAK. Predoctoral fellowship support to RPM from Wayne State University School of Medicine is gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations

- DMR

Differentially Methylated Region

- DNMTs

DNA MethylTransferases

- HP1

heterochromatin protein 1

- HATs

Histone AcetylTranserases

- HDACs

Histone De-ACetylases

- MTases

histone MethylTransferases

- ISWI

Imitation SWItch

- MBD

Methyl-CpG Binding Domain

- NuRDs

Nucleosome Remodelling and histone De-acetylases

- PcG

polycomb group

- RNAi

RNA interference

- RdRP

RNA-dependent RNA Poymerase-based

- RITS

RNA-induced Initiation of Transcriptional gene Silencing complex

- RISC

RNA-Induced Silencing Complex

- SWI/SNF

SWItch/Sucrose Non-Fermenting helicases

References

- Aapola U, Lyle R, Krohn K, Antonarakis SE, Peterson P. Isolation and initial characterization of the mouse Dnmt3l gene. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 2001;92:122–6. doi: 10.1159/000056881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agalioti T, Chen G, Thanos D. Deciphering the transcriptional histone acetylation code for a human gene. Cell. 2002;111:381–92. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez JD, Yasui DH, Niida H, Joh T, Loh DY, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. The MAR-binding protein SATB1 orchestrates temporal and spatial expression of multiple genes during T-cell development. Genes Dev. 2000;14:521–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir RE, Van den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nat Genet. 1999;23:185–8. doi: 10.1038/13810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir RE, Zoghbi HY. Rett syndrome: methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 mutations and phenotype-genotype correlations. Am J Med Genet. 2000;97:147–52. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(200022)97:2<147::aid-ajmg6>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antequera F, Bird A. CpG Islands. In: Jost JP, Saluz HP, editors. DNA methylation: molecular biology and biological significance. 1993. pp. 169–185. [Google Scholar]

- Aufsatz W, Mette MF, van der Winden J, Matzke AJ, Matzke M. RNA-directed DNA methylation in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(Suppl 4):16499–506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162371499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramaniam U, Oleinick NL. Preferential cross-linking of matrix-attachment region (MAR) containing DNA fragments to the isolated nuclear matrix by ionizing radiation. Biochemistry. 1995;34:12790–12802. doi: 10.1021/bi00039a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister AJ, Zegerman P, Partridge JF, Miska EA, Thomas JO, Allshire RC, Kouzarides T. Selective recognition of methylated lysine 9 on histone H3 by the HP1 chromo domain. Nature. 2001;410:120–4. doi: 10.1038/35065138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barseguian K, Lutterbach B, Hiebert SW, Nickerson J, Lian JB, Stein JL, van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS. Multiple subnuclear targeting signals of the leukemia-related AML1/ETO and ETO repressor proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15434–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242588499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker PB, Horz W. ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:247–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beisel C, Imhof A, Greene J, Kremmer E, Sauer F. Histone methylation by the Drosophila epigenetic transcriptional regulator Ash1. Nature. 2002;419:857–62. doi: 10.1038/nature01126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell AC, Felsenfeld G. Methylation of a CTCF-dependent boundary controls imprinted expression of the Igf2 gene. Nature. 2000;405:482–485. doi: 10.1038/35013100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benham C, Kohwi-Shigematsu T, Bode J. Stress-induced duplex DNA destabilization in scaffold/matrix attachment regions. J Mol Biol. 1997;274:181–96. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E, Caudy AA, Hammond SM, Hannon GJ. Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature. 2001;409:363–6. doi: 10.1038/35053110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird AP. CpG-rich islands and the function of DNA methylation. Nature. 1986;321:209–13. doi: 10.1038/321209a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode J, Benham C, Knopp A, Mielke C. Transcriptional augmentation: modulation of gene expression by scaffold/matrix-attached regions (S/MAR elements) Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2000;10:73–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifer C. Long-distance chromatin mechanisms controlling tissue-specific gene locus activation. Gene. 1999;238:277–289. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00340-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourc’his D, Bestor TH. Helicase homologues maintain cytosine methylation in plants and mammals. Bioessays. 2002;24:297–9. doi: 10.1002/bies.10078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourc’his D, Xu GL, Lin CS, Bollman B, Bestor TH. Dnmt3L and the establishment of maternal genomic imprints. Science. 2001;294:2536–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1065848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breault JE, Shiina H, Igawa M, Ribeiro-Filho LA, Deguchi M, Enokida H, Urakami S, Terashima M, Nakagawa M, Kane CJ, Carroll PR, Dahiya R. Methylation of the gamma-catenin gene is associated with poor prognosis of renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:557–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brink RA. Mutable loci and development of the organism. J Cell Physiol. 1958a;52:169–95. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030520410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brink RA. Paramutation at the R locus in maize. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1958b;23:379–91. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1958.023.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CJ, Baldry SE. Evidence that heteronuclear proteins interact with XIST RNA in vitro. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1996;22:403–17. doi: 10.1007/BF02369896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplen NJ. Gene therapy progress and prospects. Downregulating gene expression: the impact of RNA interference. Gene Ther. 2004;11:1241–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambeyron S, Bickmore WA. Chromatin decondensation and nuclear reorganization of the HoxB locus upon induction of transcription. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1119–3. doi: 10.1101/gad.292104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambeyron S, Da Silva NR, Lawson KA, Bickmore WA. Nuclear re-organisation of the Hoxb complex during mouse embryonic development. Development. 2005;132:2215–23. doi: 10.1242/dev.01813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee TK, Fisher RA. RGS12TS-S localizes at nuclear matrix-associated subnuclear structures and represses transcription: structural requirements for subnuclear targeting and transcriptional repression. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:4334–45. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.12.4334-4345.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Li E. Current Topics in Developmental Biology. 2004. Structure and Function of Eukaryotic DNA Methyltransferases; p. 55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Mariappan SV, Catasti P, Ratliff R, Moyzis RK, Laayoun A, Smith SS, Bradbury EM, Gupta G. Hairpins are formed by the single DNA strands of the fragile X triplet repeats: structure and biological implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:5199–203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.5199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SJ, Harrison J, Frommer M. CpNpG methylation in mammalian cells. Nat Genet. 1995;10:20–7. doi: 10.1038/ng0595-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig JM. Heterochromatin--many flavours, common themes. Bioessays. 2005;27:17–28. doi: 10.1002/bies.20145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer T, Kreth G, Koester H, Fink RH, Heintzmann R, Cremer M, Solovei I, Zink D, Cremer C. Chromosome territories, interchromatin domain compartment, and nuclear matrix: an integrated view of the functional nuclear architecture. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2000;10:179–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouse HV. The controlling element in chromosome behaviour in Sciara. Genetics. 1960;45:1429–1443. doi: 10.1093/genetics/45.10.1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daban JR. Physical constraints in the condensation of eukaryotic chromosomes. Local concentration of DNA versus linear packing ratio in higher order chromatin structures. Biochemistry. 2000;39:3861–6. doi: 10.1021/bi992628w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daban JR. High concentration of DNA in condensed chromatin. Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;81:91–9. doi: 10.1139/o03-037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Carcer G, Lallena MJ, Correas I. Protein 4.1 is a component of the nuclear matrix of mammalian cells. Biochem J. 1995;312 (Pt 3):871–7. doi: 10.1042/bj3120871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cruz X, Lois S, Sanchez-Molina S, Martinez-Balbas MA. Do protein motifs read the histone code? Bioessays. 2005;27:164–75. doi: 10.1002/bies.20176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Laat W, Grosveld F. Spatial organization of gene expression: the active chromatin hub. Chromosome Res. 2003;11:447–59. doi: 10.1023/a:1024922626726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ruijter AJ, van Gennip AH, Caron HN, Kemp S, van Kuilenburg AB. Histone deacetylases (HDACs): characterization of the classical HDAC family. Biochem J. 2003;370:737–49. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis K, Fan T, Geiman T, Yan Q, Muegge K. Lsh, a member of the SNF2 family, is required for genome-wide methylation. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2940–2944. doi: 10.1101/gad.929101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deplus R, Brenner C, Burgers WA, Putmans P, Kouzarides T, de Launoit Y, Fuks F. Dnmt3L is a transcriptional repressor that recruits histone deacetylase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3831–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson LA, Dickinson CD, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. An atypical homeodomain in SATB1 promotes specific recognition of the key structural element in a matrix attachment region. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11463–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietzel S, Schiebel K, Little G, Edelmann P, Rappold GA, Eils R, Cremer C, Cremer T. The 3D positioning of ANT2 and ANT3 genes within female X chromosome territories correlates with gene activity. Exp Cell Res. 1999;252:363–75. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djabali K, Christiano AM. Hairless contains a novel nuclear matrix targeting signal and associates with histone deacetylase 3 in nuclear speckles. Differentiation. 2004;72:410–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2004.07208007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworetzky SI, Wright KL, Fey EG, Penman S, Lian JB, Stein JL, Stein GS. Sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins are components of a nuclear matrix-attachment site. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:4178–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.4178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger G, Liang G, Aparicio A, Jones PA. Epigenetics in human disease and prospects for epigenetic therapy. Nature. 2004;429:457–63. doi: 10.1038/nature02625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel H, Ruhl H, Benham CJ, Bode J, Weiss S. Germ-line transcripts of the immunoglobulin lambda J-C clusters in the mouse: characterization of the initiation sites and regulatory elements. Mol Immunol. 2001;38:289–302. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(01)00056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EMBL-EBI and The Sanger Institute. Ensembl Human Genome Assembly (release 3. 35d) 2005 http://www.ensembl.org/Homo_sapiens.

- Fischle W, Wang Y, Allis CD. Histone and chromatin cross-talk. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2003a;15:172. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischle W, Wang Y, Jacobs SA, Kim Y, Allis CD, Khorasanizadeh S. Molecular basis for the discrimination of repressive methyl-lysine marks in histone H3 by Polycomb and HP1 chromodomains. Genes Dev. 2003b;17:1870–81. doi: 10.1101/gad.1110503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaus A, Owen-Hughes T. Mechanisms for nucleosome mobilization. Biopolymers. 2003;68:563–78. doi: 10.1002/bip.10323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Free A, Wakefield RI, Smith BO, Dryden DT, Barlow PN, Bird AP. DNA recognition by the methyl-CpG binding domain of MeCP. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3353–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007224200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M, Frech K, Klingenhoff A, Cartharius K, Liebich I, Werner T. In silico prediction of scaffold/matrix attachment regions in large genomic sequences. Genome Res. 2002;12:349–54. doi: 10.1101/gr.206602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry CJ, Peterson CL. Chromatin remodeling enzymes: who’s on first? Curr Biol. 2001;11:R185–97. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuks F, Burgers WA, Brehm A, Hughes-Davies L, Kouzarides T. DNA methyltransferase Dnmt1 associates with histone deacetylase activity. Nat Genet. 2000;24:88–91. doi: 10.1038/71750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuks F, Burgers WA, Godin N, Kasai M, Kouzarides T. Dnmt3a binds deacetylases and is recruited by a sequence-specific repressor to silence transcription. Embo J. 2001;20:2536–44. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.10.2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuks F, Hurd PJ, Wolf D, Nan X, Bird AP, Kouzarides T. The methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 links DNA methylation to histone methylation. J Biol Chem. 2002 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210256200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgel PT, Fletcher TM, Hager GL, Hansen JC. Formation of higher-order secondary and tertiary chromatin structures by genomic mouse mammary tumor virus promoters. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1617–29. doi: 10.1101/gad.1097603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil J, Bernard D, Peters G. Role of polycomb group proteins in stem cell self-renewal and cancer. DNA Cell Biol. 2005;24:117–25. doi: 10.1089/dna.2005.24.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill G. SUMO and ubiquitin in the nucleus: different functions, similar mechanisms? Genes Dev. 2004;18:2046–2059. doi: 10.1101/gad.1214604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetze S, Baer A, Winkelmann S, Nehlsen K, Seibler J, Maass K, Bode J. Performance of genomic bordering elements at predefined genomic loci. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2260–72. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.6.2260-2272.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grishok A, Pasquinelli AE, Conte D, Li N, Parrish S, Ha I, Baillie DL, Fire A, Ruvkun G, Mello CC. Genes and mechanisms related to RNA interference regulate expression of the small temporal RNAs that control C. elegans developmental timing. Cell. 2001;106:23–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00431-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero-Santoro J, Yang L, Stallcup MR, DeFranco DB. Distinct LIM domains of Hic-5/ARA55 are required for nuclear matrix targeting and glucocorticoid receptor binding and coactivation. J Cell Biochem. 2004;92:810–9. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajkova P, Erhardt S, Lane N, Haaf T, El-Maarri O, Reik W, Walter J, Surani MA. Epigenetic reprogramming in mouse primordial germ cells. Mechanisms of Development. 2002;117:15. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton A, Voinnet O, Chappell L, Baulcombe D. Two classes of short interfering RNA in RNA silencing. Embo J. 2002;21:4671–9. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SM, Bernstein E, Beach D, Hannon GJ. An RNA-directed nuclease mediates post-transcriptional gene silencing in Drosophila cells. Nature. 2000;404:293–6. doi: 10.1038/35005107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SM, Boettcher S, Caudy AA, Kobayashi R, Hannon GJ. Argonaute2, a link between genetic and biochemical analyses of RNAi. Science. 2001;293:1146–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1064023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Lee Y, Yeom KH, Kim YK, Jin H, Kim VN. The Drosha-DGCR8 complex in primary microRNA processing. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3016–27. doi: 10.1101/gad.1262504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen RS, Wijmenga C, Luo P, Stanek AM, Canfield TK, Weemaes CM, Gartler SM. The DNMT3B DNA methyltransferase gene is mutated in the ICF immunodeficiency syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14412–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata K, Okano M, Lei H, Li E. Dnmt3L cooperates with the Dnmt3 family of de novo DNA methyltransferases to establish maternal imprints in mice. Development. 2002;129:1983–93. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He WW, Lindzey JK, Prescott JL, Kumar MV, Tindall DJ. The androgen receptor in the testicular feminized (Tfm) mouse may be a product of internal translation initiation. Receptor. 1994;4:121–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heng HH, Goetze S, Ye CJ, Liu G, Stevens JB, Bremer SW, Wykes SM, Bode J, Krawetz SA. Chromatin loops are selectively anchored using scaffold/matrix-attachment regions. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:999–1008. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann A, Schmitt S, Jeltsch A. The human Dnmt2 has residual DNA-(cytosine-C5) methyltransferase activity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31717–21. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305448200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday R, Pugh JE. DNA modification mechanisms and gene activity during development. Science. 1975;187:226–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh CL. In vivo activity of murine de novo methyltransferases, Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:8211–8. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh CL. Dynamics of DNA methylation pattern. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:224–8. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh J, Fire A. Recognition and silencing of repeated DNA. Annu Rev Genet. 2000;34:187–204. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JY, Shen BJ, Tsai WH, Lee SC. Functional interaction between nuclear matrix-associated HBXAP and NF-kappaB. Exp Cell Res. 2004;298:133–43. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutvagner G, McLachlan J, Pasquinelli AE, Balint E, Tuschl T, Zamore PD. A cellular function for the RNA-interference enzyme Dicer in the maturation of the let-7 small temporal RNA. Science. 2001;293:834–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1062961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, Ratcliff F, Baulcombe DC. RNA-directed transcriptional gene silencing in plants can be inherited independently of the RNA trigger and requires Met1 for maintenance. Curr Biol. 2001;11:747–57. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PA, Laird PW. Cancer epigenetics comes of age. Nat Genet. 1999;21:163–7. doi: 10.1038/5947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost JP, Jost YC. Transient DNA demethylation in differentiating mouse myoblasts correlates with higher activity of 5-methyldeoxycytidine excision repair. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10040–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y, Sasaki H. Imprinting and looping: epigenetic marks control interactions between regulatory elements. Bioessays. 2005;27:1–4. doi: 10.1002/bies.20171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi K, Oda Y, Saito T, Yamamoto H, Takahira T, Tamiya S, Iwamoto Y, Tsuneyoshi M. Death-associated protein kinase (DAP kinase) alteration in soft tissue leiomyosarcoma: Promoter methylation or homozygous deletion is associated with a loss of DAP kinase expression. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:1266–71. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketting RF, Fischer SE, Bernstein E, Sijen T, Hannon GJ, Plasterk RH. Dicer functions in RNA interference and in synthesis of small RNA involved in developmental timing in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2654–9. doi: 10.1101/gad.927801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kho MR, Baker DJ, Laayoun A, Smith SS. Stalling of human DNA (cytosine-5) methyltransferase at single-strand conformers from a site of dynamic mutation. J Mol Biol. 1998;275:67–79. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khorasanizadeh S. The nucleosome: from genomic organization to genomic regulation. Cell. 2004;116:259–72. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight SW, Bass BL. A role for the RNase III enzyme DCR-1 in RNA interference and germ line development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001;293:2269–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1062039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohwi-Shigematsu T, Kohwi Y. Torsional stress stabilizes extended base unpairing in suppressor sites flanking immunoglobulin heavy chain enhancer. Biochemistry. 1990;29:9551–6. doi: 10.1021/bi00493a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontaraki J, Chen HH, Riggs A, Bonifer C. Chromatin fine structure profiles for a developmentally regulated gene: reorganization of the lysozyme locus before trans-activator binding and gene expression. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2106–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JA, Krawetz SA. Matrix-associated regions in haploid expressed domains. Mamm Genome. 1995;6:677–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00352382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JA, McCarrey JR, Djakiew D, Krawetz SA. Differentiation: the selective potentiation of chromatin domains. Development. 1998;125:4749–55. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.23.4749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JA, Singh GB, Krawetz SA. Computer-assisted search for sites of nuclear matrix attachment. Genomics. 1996;33:305–8. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JA, Zhang S, Yaron Y, Zhao Y, Krawetz SA. Genetic testing for male infertility: a postulated role for mutations in sperm nuclear matrix attachment regions. Genet Test. 1997;1:125–9. doi: 10.1089/gte.1997.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawetz SA. Paternal contribution: new insights and future challenges. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:633–42. doi: 10.1038/nrg1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunert N, Marhold J, Stanke J, Stach D, Lyko F. A Dnmt2-like protein mediates DNA methylation in Drosophila. Development. 2003;130:5083–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.00716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz A, Lampel S, Nickolenko JE, Bradl J, Benner A, Zirbel RM, Cremer T, Lichter P. Active and inactive genes localize preferentially in the periphery of chromosome territories. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1195–205. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.5.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laayoun A, Smith SS. Methylation of slipped duplexes, snapbacks and cruciforms by human DNA(cytosine-5)methyltransferase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:1584–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.9.1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachner M, O’Carroll D, Rea S, Mechtler K, Jenuwein T. Methylation of histone H3 lysine 9 creates a binding site for HP1 proteins. Nature. 2001;410:116–2. doi: 10.1038/35065132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachner M, O’Sullivan RJ, Jenuwein T. An epigenetic road map for histone lysine methylation. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:2117–2124. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science. 2001;294:853–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1064921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau NC, Lim LP, Weinstein EG, Bartel DP. An abundant class of tiny RNAs with probable regulatory roles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001;294:858–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1065062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, Ambros V. An extensive class of small RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001;294:862–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1065329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-1. Cell. 1993;75:843–54. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Ahn C, Han J, Choi H, Kim J, Yim J, Lee J, Provost P, Radmark O, Kim S, Kim VN. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature. 2003;425:415–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Kim M, Han J, Yeom KH, Lee S, Baek SH, Kim VN. MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. Embo J. 2004;23:4051–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Peterson KR, Fang X, Stamatoyannopoulos G. Locus control regions. Blood. 2002;100:3077–3086. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowndes NF, Toh GW. DNA repair: the importance of phosphorylating histone H2AX. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R99–R102. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund E, Guttinger S, Calado A, Dahlberg JE, Kutay U. Nuclear export of microRNA precursors. Science. 2004;303:95–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1090599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon MF. Gene action in the X-chromosome of the mouse (Mus musculus L.) Nature. 1961;190:372–3. doi: 10.1038/190372a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone CJ, Fixsen WD, Horvitz HR, Han M. UNC-84 localizes to the nuclear envelope and is required for nuclear migration and anchoring during C. elegans development. Development. 1999;126:3171–81. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.14.3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marahrens Y, Panning B, Dausman J, Strauss W, Jaenisch R. Xist-deficient mice are defective in dosage compensation but not spermatogenesis. Genes Dev. 1997;11:156–66. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins RP, Krawetz SA. Using multiplexed real-time polymerase chain reaction to rapidly identify single-copy transgenic animals. Anal Biochem. 2004;329:337–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins RP, Krawetz SA. RNA in human sperm. Asian J Androl. 2005;7 doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2005.00048.x. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo K, Silke J, Georgiev O, Marti P, Giovannini N, Rungger D. An embryonic demethylation mechanism involving binding of transcription factors to replicating DNA. Embo J. 1998;17:1446–53. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClintock B. The suppressor-mutator system of control of gene action in maize. Carnegie Inst Wash Year Book. 1958;60:469–476. [Google Scholar]

- McKnight RA, Shamay A, Lakshmanan S, Wall RJ, Hennighausen L. Matrix-attachment regions can impart position-independent regulation of a tissue-specific gene in transgenic mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 1992;89:6943–6947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.6943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mette MF, Aufsatz W, van der Winden J, Matzke MA, Matzke AJ. Transcriptional silencing and promoter methylation triggered by double-stranded RNA. Embo J. 2000;19:5194–201. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.19.5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mielke C, Kohwi Y, Kohwi-Shigematsu T, Bode J. Hierarchical binding of DNA fragments derived from scaffold-attached regions: correlation of properties in vitro and function in vivo. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7475–85. doi: 10.1021/bi00484a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mika S, Rost B. NMPdb: Database of Nuclear Matrix Proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D160–3. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirkovitch J, Mirault ME, Laemmli UK. Organization of the higher-order chromatin loop: specific DNA attachment sites on nuclear scaffold. Cell. 1984;39:223–32. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90208-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk M, Boubelik M, Lehnert S. Temporal and regional changes in DNA methylation in the embryonic, extraembryonic and germ cell lineages during mouse embryo development. Development. 1987;99:371–82. doi: 10.1242/dev.99.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motamedi MR, Verdel A, Colmenares SU, Gerber SA, Gygi SP, Moazed D. Two RNAi complexes, RITS and RDRC, physically interact and localize to noncoding centromeric RNAs. Cell. 2004;119:789–802. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourelatos Z, Dostie J, Paushkin S, Sharma A, Charroux B, Abel L, Rappsilber J, Mann M, Dreyfuss G. miRNPs: a novel class of ribonucleoproteins containing numerous microRNAs. Genes Dev. 2002;16:720–8. doi: 10.1101/gad.974702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrell A, Heeson S, Reik W. Interaction between differentially methylated regions partitions the imprinted genes Igf2 and H19 into parent-specific chromatin loops. Nat Genet. 2004;36:889–93. doi: 10.1038/ng1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Kanai Y, Ushijima S, Kitamura T, Kakizoe T, Hirohashi S. DNA hypomethylation on pericentromeric satellite regions significantly correlates with loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 9 in urothelial carcinomas. J Urol. 2005;173:243–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000141577.98902.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namciu SJ, Blochlinger KB, Fournier RE. Human matrix attachment regions insulate transgene expression from chromosomal position effects in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2382–91. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]