Abstract

Aims

To collect information on the use of the Reveal implantable loop recorder (ILR) in the patient care pathway and to investigate its effectiveness in the diagnosis of unexplained recurrent syncope in everyday clinical practice.

Methods and results

Prospective, multicentre, observational study conducted in 2006–2009 in 10 European countries and Israel. Eligible patients had recurrent unexplained syncope or pre-syncope. Subjects received a Reveal Plus, DX or XT. Follow up was until the first recurrence of a syncopal event leading to a diagnosis or for ≥1 year. In the course of the study, patients were evaluated by an average of three different specialists for management of their syncope and underwent a median of 13 tests (range 9–20). Significant physical trauma had been experienced in association with a syncopal episode by 36% of patients. Average follow-up time after ILR implant was 10 ± 6 months. Follow-up visit data were available for 570 subjects. The percentages of patients with recurrence of syncope were 19, 26, and 36% after 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively. Of 218 events within the study, ILR-guided diagnosis was obtained in 170 cases (78%), of which 128 (75%) were cardiac.

Conclusion

A large number of diagnostic tests were undertaken in patients with unexplained syncope without providing conclusive data. In contrast, the ILR revealed or contributed to establishing the mechanism of syncope in the vast majority of patients. The findings support the recommendation in current guidelines that an ILR should be implanted early rather than late in the evaluation of unexplained syncope.

Keywords: Reveal, Guidelines, Implantable loop recorder, Traumas, Injuries, Cardiac syncope

Introduction

Syncope is common in the general population1,2 and is perceived as an important clinical problem with adverse outcomes from associated physical trauma, negative impact on quality of life, and an increased cardiovascular risk in many patients.2–5

The first European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of syncope were published in 20016 and were revised in 20047 and 2009.8 The 2009 guidelines differ from earlier versions not only in their specific recommendations but also in their transatlantic endorsement; the guidelines were developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) and Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) and were endorsed by a large number of national societies on both sides of the Atlantic. This range of specialties reflects the fact that syncope is a transient and often un-witnessed symptom with many possible underlying causes, leading to difficulties in standardizing diagnostic procedures.

The updated versions of the guidelines highlight the use of implantable loop recorders (ILRs) and recommend their early use in the diagnostic work-up. In the majority of patients with a syncopal event, a corresponding arrhythmic event is likely to be seen in the ECG. The gold standard of diagnosis remains the correlation of a spontaneous event with a specific ECG finding,9 but as the occurrence of syncope tends to be unpredictable, observers are unlikely to have the opportunity to record ECGs at the time of an event. The ability of ILRs to continuously record ECGs over long periods, with newer versions having longevity up to 3 years, makes them powerful diagnostic tools in patients with syncope secondary to an arrhythmia.

The PICTURE (Place of Reveal In the Care pathway and Treatment of patients with Unexplained Recurrent Syncope) registry aimed to collect information on the use of the Reveal ILR (Medtronic Inc.) in the patient care pathway and to investigate the effectiveness of Reveal in the diagnosis of unexplained recurrent syncope and pre-syncope in everyday clinical practice. Data were gathered after the publication of the 2004 ESC guidelines and before the new 2009 version became available.

Methods

The PICTURE was a prospective, multicentre, observational post-marketing study conducted from November 2006 until October 2009 in 11 countries (Austria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Israel, The Netherlands, the Slovak Republic, Sweden, and Switzerland). A total of 71 sites contributed to patient enrolment (see Appendix). The study was conducted in full compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.10 All investigators were required to follow the policies and procedures set forth by their governing Institutional Review Board (IRB)/Ethics Committee in compliance with local requirements. Participating patients gave written informed consent. The main objectives of the PICTURE study were to describe the standard care pathway in unexplained syncope, evaluate the burden of diagnostic tests, determine the diagnostic yield of the ILR, evaluate the time to diagnosis in relation to the timing of the ILR implant, determine the ratio between ‘cardiac-related’ and ‘non-cardiac-related’ diagnoses, determine the relationship between the number of preceding syncopal events and the time to diagnosis, and evaluate the relationship between diagnostic test results and ILR-documented diagnosis.

Patients were eligible if they had recurrent unexplained syncope or pre-syncope, estimated after the event and not separated in the analysis. The term ‘unexplained’ was not defined in the protocol but the application of the term to a patient and the subsequent decision to implant an ILR and the programming of the device were left to the investigator's discretion. Investigators were to indicate if they implanted an ILR in the initial phase of the diagnostic process (in the guidelines of 2004 consisting of a thorough medical history, physical examination, orthostatic blood pressure measurements, or echocardiogram) or after a full diagnostic work-up (as interpreted by the respective investigator). Patients were followed up until the first recurrence of a syncopal event leading to a diagnosis or for at least 1 year.

At the time of enrolment, the following was recorded: history of syncope in the previous 2 years, total number of syncopal events during life time of patient, clinical characteristics of syncope, number of syncopal episodes with severe trauma (defined as fractures or injury with bleeding), clinical history, number of specialists seen in relation to syncope, specialty of physician referring for implant, number of admissions to ER and/or hospitalizations, diagnostic tests performed before implant of an ILR, and suspected diagnosis guided by the diagnostic tests before implant. Data on device implant complications were not actively collected. Follow-up was per normal clinical practice and subjects were advised to contact the treating physician promptly in the case of a suspected event. At follow-up visits, clinical characteristics of syncope, occurrence of severe trauma, admissions to ER and/or hospitalizations, the role of the ILR in establishing a diagnosis, ILR-guided diagnosis, other tests undertaken, and treatment administered for syncope were recorded.

Statistical analysis

All enrolled subjects received a Reveal Plus, DX or XT ILR. For a patient to be included in the final analysis, an implant/discharge visit was required together with a recurrence visit or a 1-year follow-up visit. For patients with more than one follow-up visit, the first visit after an event was included in the analysis. If patients had no event, the last visit that took place during the pre-specified follow-up period was included in the analysis. Events that occurred between enrolment and implant were not included in the analysis. Descriptive statistics were used for the analyses. For quantitative variables such as age, the mean and standard deviation, or median and interquartile (IQ) range were calculated as appropriate. For qualitative variables, counts and percentages were calculated. Time-to-event outcomes were described using the Kaplan–Meier curves, with day of implant as time zero.

The diagnostic effectiveness of the ILR was analysed in two ways. The diagnostic yield was defined as Reveal-guided diagnosis: a syncopal episode for which Reveal played a major role in determining whether the cause of syncope was either cardiac or non-cardiac. Further, investigators could specify the role of Reveal in a diagnosis as primary, confirmatory, or additional to other confirmatory tests.

Results

Patients and follow-up

Of a total 650 enrolled subjects, follow-up visit data (with or without events) were available for 570 subjects who were included in the analysed population. Most implants were performed on the day of enrolment. Fifty-three patients had to wait a median of 3 days (IQ range 1–14) from enrolment to implant. The follow-up dates were missing for three patients and implant date for one patient. These patients were included in the follow-up analysis but excluded from the survival analysis. The average follow-up time after ILR implant was 10 ± 6 months.

Patient characteristics at baseline

Baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Average age was 61 ± 17 years and 54% were women. Seven per cent of patients were enrolled based on unexplained pre-syncope; 91% had unexplained syncope and the classification was missing for 2% of patients. Patients with syncope had experienced a median of 4 reported events prior to enrolment, of which three were within the 2 years prior to enrolment. Mean age (±SD) at first syncope was 55 ± 20 years. Reveal versions DX/XT were used in 316 patients (55%); the remaining 45% received Reveal Plus. Baseline characteristics for the 80 patients without complete follow-up did not differ from those in the overall population.

Table 1.

General characteristics of patients at study enrolment

| Total recruitment | 570 (100%) |

| Women | 306 (54%) |

| Age ± SD | 61 ± 17 |

| Primary Indication | |

| Unexplained syncope | 517 (91%) |

| Unexplained pre-syncope | 42 (7%) |

| Other | 11 (2%) |

| History | |

| Hypertension | 277 (49%) |

| Coronary artery disease | 84 (15%) |

| Valvular heart disease | 30 (5%) |

| Cardiomyopathy | 18 (3%) |

| Stroke/TIA | 57 (10%) |

| Diagnostic work-up before ILR implant | |

| In an initial phase of diagnostic work-up of syncope | 128 (22%) |

| After full evaluation of mechanism of syncope | 386 (68%) |

| Device Implanted | |

| Reveal DX | 264 (46%) |

| Reveal XT | 52 (9%) |

| Reveal Plus | 254 (45%) |

| Age at first syncope | 55 ± 20 |

| Previous syncopes median (IQ range) | 4 (2–6) |

| Syncopes in the last 2 years median (IQ range) | 3 (2–4) |

| Syncopal episodes per year median (IQ range) | 2 (1–3.5) |

| Median interval between first and last episode years (IQ range) | 2 (0–4) |

| Any previous hospitalization because of syncope | 399 (70%) |

| Any syncopal episodes without prodromes | 339 (59%) |

| Any syncopal episodes with severe trauma | 204 (36%) |

| Any syncopal episodes suggestive of vasovagal origin | 86 (15%) |

| Any situational syncope | 39 (7%) |

| Characteristics of last syncope | |

| After effort | 28 (5%) |

| During effort | 144 (25%) |

| At rest | 294 (52%) |

| Unknown | 97 (17%) |

| Missing | 7 (1%) |

| Symptoms | |

| Muscle spasms (one sided) | 8 (1%) |

| Muscle spasms (two sided) | 19 (3%) |

| Grand mal | 10 (2%) |

| Other muscle spasms | 14 (2%) |

| Transpiration | 73 (13%) |

| Cyanosis | 19 (3%) |

| Angina pectoris | 23 (4%) |

| Palpitations | 76 (13%) |

| Dizziness | 163 (29%) |

| Dyspnoea | 33 (6%) |

| Fatigue | 95 (17%) |

| Other | 80 (14%) |

| None | 266 (47%) |

Physicians consulted and diagnostic tests performed before ILR implant

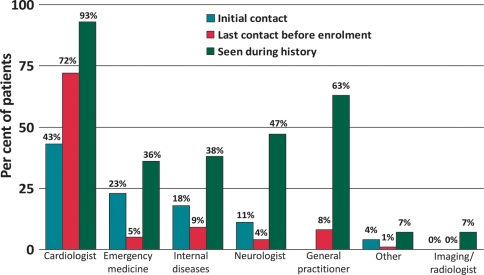

The first specialist consulted for syncope in almost 23% of patients was an emergency medicine consultant. Cardiologists were the first specialists consulted in 43% of cases and neurologists in 11% (Figure 1). The last specialist consulted before the referral for implant of the ILR was a cardiologist in 72% of cases, with no other specialties represented in more than 10% of cases (Figure 1). Cardiologists were the most frequently consulted specialists, with general practitioners second-most consulted physicians overall. Forty-seven per cent of the study population had consulted a neurologist at some point. Overall, patients had seen an average of three different specialists for management of their syncope. Most patients (70%) had been hospitalized at least once for syncope and one-third (36%) had experienced significant trauma in association with a syncopal episode.

Figure 1.

Physicians consulted in relation to syncope. Blue, red, and green bars indicate specialists seen at the hospital for the latest syncope episode; shaded bars last specialist consulted before ILR implant; open bars all specialists reported by patients as being consulted in relation to syncope in the past. GP, general practitioner. Data on GP consultations at initial contact were not collected.

The median number of tests performed per patient in the total study population was 13 (IQ range 9–20; Table 2). The tests performed most frequently were echocardiography, ECG, ambulatory ECG monitoring, in-hospital ECG monitoring, exercise testing, and orthostatic blood pressure measurements. About half the patient population had undergone an MRI/CT scan (47%), neurological or psychiatric evaluation (47%), or electroencephalography (EEG; 39%). In contrast, carotid sinus massage or tilt tests were only undertaken in one-third of subjects. The ILR was implanted during the initial phase of the diagnostic work-up (up to four diagnostic tests) in 128 patients (22%).

Table 2.

History of diagnostic tests performed before ILR implant

| Total recruitment | 570 (100%) |

| Standard ECG | 556 (98%) |

| Echocardiography | 490 (86%) |

| Basic laboratory tests | 488 (86%) |

| Ambulatory ECG monitoring | 382 (67%) |

| In-hospital ECG monitoring | 311 (55%) |

| Exercise testing | 297 (52%) |

| Orthostatic blood pressure measurements | 275 (48%) |

| MRI / CT scan | 267 (47%) |

| Neurological or psychiatric evaluation | 270 (47%) |

| EEG | 222 (39%) |

| Carotid sinus massage | 205 (36%) |

| Tilt test | 201 (35%) |

| Electrophysiology testing | 144 (25%) |

| Coronary angiography | 133 (23%) |

| External loop recording | 67 (12%) |

| ATP test | 15 (3%) |

| Other tests | 52 (9%) |

| No tests performed | 1 (0%) |

Diagnostic yield

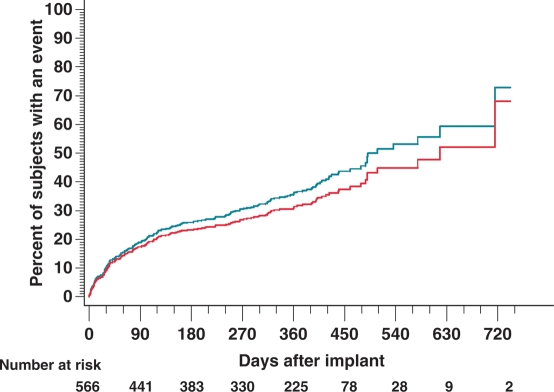

During follow-up, a total of 218 patients (38% of the population) experienced an episode of syncope, 149 (26% of patients or 68% of episodes) with prodromal symptoms. The percentages of patients who had a recurrence of syncope were 19, 26, and 36% after 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively (Figure 2). Ten patients with an episode during follow-up (5.2% of the population with an event) had associated severe trauma.

Figure 2.

The Kaplan–Meier estimates of time to syncopal episode (green line) and time to syncopal episode where Reveal played a role in the diagnosis (red line).

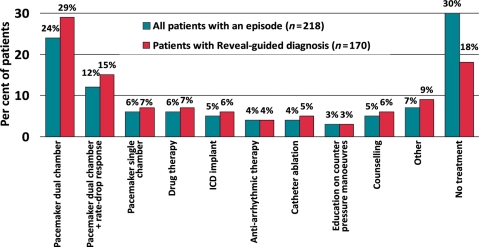

There were 25 symptomatic recurrences without an ILR recording. Time to a syncopal event where Reveal played a role in the diagnosis showed the recurrence of diagnosis within 180 days as 20%, within 365 days as 30%, and within 462 days as 38% (Figure 2). The estimated rate of syncope after 30 days of follow-up was 10% and the estimated rate of diagnosis where Reveal played a role at this time of follow-up was 9%. Of the 218 events, 23 diagnoses were reported as not guided by Reveal data and for 12 patients, data were inconclusive. The diagnosis was reported as guided by Reveal in 78% of cases or 170 patients (Figure 3); the role in 13 diagnoses was inconclusive.

Figure 3.

Patient flow chart and diagnostic yield of the ILR in PICTURE.

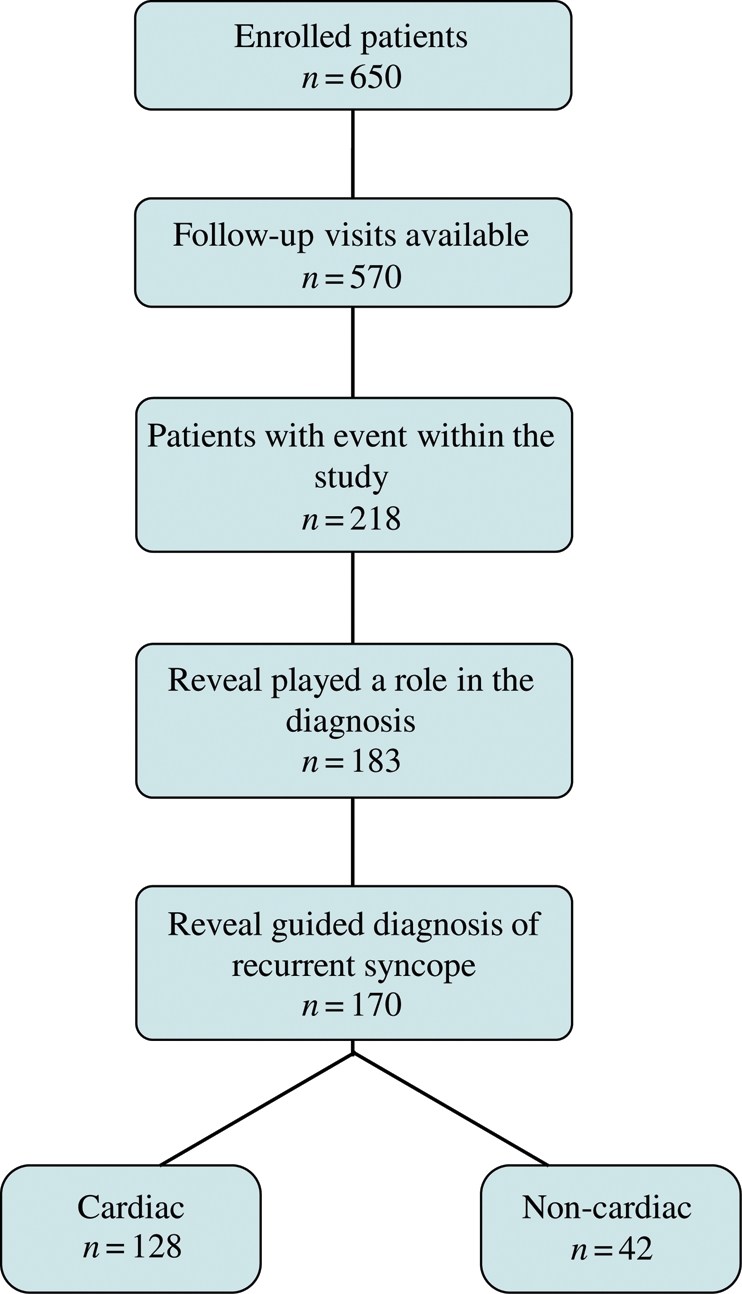

Specific treatment based on diagnosis made by ILR

Of the 170 Reveal-guided diagnoses, 75%, or 128 cases, were cardiac. This represented 59% of all recurrences of syncope. Reveal-guided diagnosis led to pacemaker implants in 86 patients, 51% of diagnosed cases. Antiarrhythmic drug therapy (7%), implantable cardioverter defibrillators (6%) and ablation (5%) were also utilized as treatment. No specific treatment was used in 18% of cases (Figure 4). Therapies were similar in the total population with an event (n = 218) but more patients in this population remained untreated upon diagnosis. In the 48 patients with an episode but without Reveal-guided diagnosis, 12% received dual-chamber pacemakers, 4% anti-arrhythmic drug therapy, 4% had other drug therapy, and 4% education/counselling. There were no ICD implants or catheter ablations in these patients. The basis for diagnosis was not captured in these 48 subjects.

Figure 4.

Treatment decisions made in relation to syncope after diagnosis. There were no ICD implants or catheter ablations in the 48 patients with an episode but without Reveal-guided diagnosis.

Discussion

The results of the PICTURE study provide new and important insights into the discrepancy between real-life care and the recommendations in the ESC guidelines at the time. The results underline that more efforts are needed if better adherence to guidelines are to be obtained. Two important findings were the large number of diagnostic tests that patients underwent before an ILR implant and the high diagnostic yield from the use of an ILR in the overall population with unexplained syncope. Together, these findings imply that if an ILR is implanted early, as emphasized in the 2009 ESC guidelines, a reduced number of tests might be needed.

The PICTURE is the largest observational study to date to evaluate the usage and diagnostic effectiveness of ILRs in the everyday clinical diagnostic work-up of patients with unexplained syncope. The registry included European countries and Israel, but the findings may have wider relevance. As in Europe, implementation of guidelines in the USA has been patchy with several different recommendations published.11 The 2009 guidelines are based on transatlantic consensus and might be better prepared to improve adherence but at present, there is an important gap between what guidelines prescribe and how the real-life care of patients with unexplained syncope is carried out.

The population in PICTURE was slightly younger and healthier than those in other syncope studies such as EaSyAS,12 EGSYS 2,13 and ISSUE 2.14 The number of syncopal events before patients were considered for ILR implantation was close to those reported from EaSyAS and EGSYS 2. In comparison with these and other reports,15 the incidence of severe trauma was high in PICTURE, particularly considering that the first syncope occurred only a few years before the implant. However, the study protocol did not include a specific term for mild traumas and the rates may be increased by mild injuries being reported as severe.

The PICTURE study did not ascertain how familiar investigators were with the 2004 guidelines which recommended ILRs only as a last resort when other tests have failed to reach a diagnosis. Such familiarity would make the results more understandable. Nevertheless, a median of 13 tests per patient before considering an implant seems unnecessarily high. The large number of investigations may well have been due to the number of different specialists that patients met. The frequent use of EEG has been observed in other evaluations of diagnostic pathways for patients with syncope.16,17 In PICTURE, the EEG rates are most likely explained by the high percentage of referrals to neurologists. The clinical picture of syncope frequently includes neurological symptoms and is often mistaken for epilepsy,18 which probably explains why neurologists are frequently consulted. Conversely, epilepsy may be mistaken as syncope, but in such patients, an ILR may be a faster way to arrive at the correct diagnosis, if an ILR recording can be obtained during a typical episode. Furthermore, almost half the patient population had undergone an MRI/CT scan, neurological evaluation, or psychiatric evaluation. In the EGSYS 1 population, reflecting the clinical context in 2001, the rates of MRI and/or CT scan were 20%.17 There were, however, simple diagnostic tests that could have been used more widely and would have been included in the initial phase of evaluation, e.g. tilt test, carotid sinus massage, and orthostatic blood pressure measurements. Carotid sinus massage or tilt tests were performed on about one-third of the PICTURE subjects and since multiple tests were allowed, it is likely that more than two-thirds of the population did not undergo these tests.

In theory, the differentiation between various forms of loss of consciousness and seizures may appear reasonably easy, but in the real world, the diagnosis most often has to be based on the retrospective observations of bystanders and little information from the patient, who has frequently no memory of the event. Thus, the patient or relatives do not know which specialist to see first, and the first physician may not be the most appropriate to reach a diagnosis. However, in PICTURE, the final diagnosis was most often a cardiac event and almost always an arrhythmic event. Also, cardiologists were often seen, both as the first and the last specialist before implant. These observations must lead to the question how to make the first contact with a cardiologist more useful, since the final diagnosis is most often to be found in his/her area of competence. Still, syncope is a very heterogeneous condition, and although the majority of events can be effectively handled, some diagnoses will be difficult. In those cases, a multidisciplinary approach is of great importance and access to physicians in other specialties needs to be considered.

The PICTURE found a high diagnostic yield with ILRs, which guided the diagnosis in 78% of patients with recurrent syncope and provided useful information in another 6%. Observational studies reflect clinical practice and without end point adjudication, site monitoring, etc., a margin for error must be taken into account. On the other hand, it can be argued that clinically relevant diagnostic yield measurements have to be obtained from studies in clinical practice with all that implies as to compliance, methodological differences between practices, etc. Diagnostic rates above 50% with the use of an ILR have been reported in other, smaller studies19–21 with one early study claiming >90%.22 One report by Farwell and Sulke16 noted markedly enhanced diagnosis rates with an increased use of automatic recording of events. Half the population in PICTURE received the newer Reveal device models in which the automatic recording mode is always active. In the other half of the patients, when automatic detection was not the default and could be switched off at the discretion of the investigator, we cannot exclude that the yield would have been improved if the automatic detection had always been enabled. There were 25 symptomatic recurrences without an ILR recording, implying that the rhythm during the event was sinus rhythm or, possibly, that automatic detection was switched off and the patient forgot or was unable to activate the device. In the Reveal Plus device, used in 254 subjects, automatic capture can be switched off, an option not available in the newer devices. An obvious action would be to advise clinicians that automatic detection should always be activated. We do not have data on the actual settings in the Reveal Plus devices. Subjects were advised to contact the treating physician promptly in the case of a suspected event; hence, it is unlikely that any symptomatic event went unrecorded from loss of memory.

Ideally, a device-based diagnosis should lead to a specific treatment, and this was very often the case in PICTURE. A cardiac cause of syncope was found in 59% of the patients with recurrent syncope, leading to symptomatic treatment with pacemakers (at rates corresponding to reported rates of bradycardia in syncope patients9), ablation and medication as well as life-saving treatment with implantable defibrillators. In less than 20% of patients with a Reveal-guided diagnosis was there a decision to undertake no specific treatment. In this group of patients, the benefit of knowing the cause of syncope would have reduced the need for further diagnostic tests. This finding implies that many tests undertaken prior to implant were unnecessary in that they had a low probability of reaching a diagnosis.

The main advantage of ILRs is to provide continuous monitoring, increasing the chances of obtaining such findings. The Kaplan–Meier estimates showed that most PICTURE patients had their first syncopal recurrence after more than 30 days from implant (Figure 2). This illustrates the need for longer-term monitoring to obtain a diagnosis. Recurrence rates during the longer follow-up period of 10 ± 6 months were 38%. This is within the range of what has been reported in other studies with similar study populations. Farwell et al.23 found a 1-year recurrence rate of 66%, whereas Solano et al.21 reported 21% yearly recurrence rates. Differences between the groups of patients are probably responsible for these discrepancies. In PICTURE, the 50% of patients who received a Reveal Plus device with a battery life of around 14 months may not have had sufficient time to experience a syncopal event. The Reveal DX/XT models that became available during the course of the conduct of PICTURE have a battery life of 3 years and given the recurrence rates increasing with time in patients with follow-up visit data beyond 12 months (Figure 2), it seems reasonable that within this time span the majority of the study population would experience an event.

Limitations

The PICTURE was an observational registry and the results should be interpreted accordingly. However, such data complement those of randomized, controlled studies, and may better describe the real-world situation. The fact that 12% of implanted patients did not have follow-up visit data is a limitation. Follow-up rates may well be improved in the future by newer technologies for remote monitoring and automatic data delivery. Patients with pre-syncope only were admitted into the registry, and they have been analysed and reported together with patients with syncope, since the subgroup was small.

Conclusions

In patients with unexplained syncope and a recurrence during follow-up, the ILR revealed or contributed to establishing the mechanism of syncope in the vast majority. The PICTURE study found a great diversity and number of physicians consulted, plus a large number of tests performed. The proportion of patients with an ILR-guided diagnosis increased over time and was still growing at the end of follow-up, implying that more patients would get a diagnosis before the end of battery life. The findings support the recommendation in current guidelines that an ILR should be implanted early rather than late in the evaluation of unexplained syncope. The best way to disseminate this information to physicians and increase the adherence to guidelines remains a challenge.

Funding

The PICTURE study was sponsored by Medtronic, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Stelios Tsintzos, Luke Johnson, Ajay Sasikumar, Erin Rapallini, Hannes Premm, Erich Groesslinger, Keith Hebert, and Giorgio Corbucci for their critical review of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest: N.E. is a member of the speaker's bureau for Medtronic. D.V. and C.G. are the employees of the Medtronic Bakken Research Center in The Netherlands. P.S. has acted as a consultant to Medtronic and has received financial support from the company. N.J.L. has received educational grants from Medtronic.

Appendix

Steering committee

Nils Edvardsson, MD, PhD, Rob van Mechelen, MD, Jean-Luc Pasquié, MD, PhD, Rodolfo Ventura, MD, and Nicholas J. Linker, MD.

PICTURE participating investigators

M. Ait Said, Clinique Ambroise Paré, Neuilly sur Seine, France; P. Ammann, Kantonsspital St Gallen, St Gallen, Switzerland; T. Aronsson, Växjö Medicinkliniken Centralsjukhuset, Växjö, Sweden; A. Bauer, Universitätsklinikum Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany; W. Benzer, Landeskrankenhaus Feldkirch, Feldkirch, Austria; V. Bernát, NÚSCH, Bratislava, Slovak Republic; D. Böcker, St Marien-Hospital Hamm, Hamm, Germany; A. Brandes, Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark; P. Breuls, Merwede Ziekenhuis Dordrecht, Dordrecht, the Netherlands; S. Buffler, Centre Hospitalier Hagueneau, Hagueneau, France; H. Ebert, Kardiologische Gemeinschaftspraxis, Riesa, Germany; A. Ebrahimi, Mölndal/Kungälv, Mölndal, Sweden; O. Eschen, Aalborg Hospital, Aalborg, Denmark; T. Fåhraeus, Universitetssjukhuset Lund, Lund, Sweden; G. Falck, Bollnässjukhus, Bollnäs, Sweden; W. Fehske, St Vinzenz-Hospital, Köln, Germany; R. Frank, APHP Hospital Pitie Salpetriere, Paris, France; V. Frykman, Danderyds Sjukhus, Stockholm, Sweden; F. Gadler, Karolinska Sjukhuset Solna & Huddinge, Stockholm, Sweden; G. Gehling, Katholische Krankenhaus Hagen gem. GmbH, St-Johannes-Hospital, Hagen, Germany; M. Geist, Edith Wolfson Hospital, Holon, Israel; J. Günther, Kardiologisches Centrum and der Klinik Rotes Kreuz am Zoo, Frankfurt, Germany; M. Gutmann, Kantonsspital Liestal, Liestal, Switzerland; H. Hartog, Diakonessenhuis Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands; H. Hartog, Diakonessenhuis Zeist, Zeist, the Netherlands; S. Jensen, Norrlands Universitetssjukhus I Umeå, Umeå, Sweden; W. Kainz, Hanusch Krankenhaus, Vienna, Austria; J. Kautzner, Institut Klinické a Experimentální Medicíny, Prague, Czech Republic; W. Kiowski, Klinik im Park AG, Zürich, Switzerland; B. Kjellman, Södersjukhuset, Stockholm, Sweden; H. Klomps, St Jans ziekenhuis, Weert, the Netherlands; H. Krappinger, Landeskrankenhaus Villach, Villach, Austria; P. Lercher, Landeskrankenhaus Graz - Medizinische Universitätsklinik, Graz, Austria; J. Lindström, Centralsjukhuset I Karlstad, Karlstad, Sweden; M. Lukat, Kliniken Essen Nordwest, Philippusstift Krankenhaus, Essen, Germany; Z. Macháčová, VÚSCH, Košice, Slovak Republic; C. Magnusson, Mälarsjukhuset, Eskilstuna, Sweden; F. Maru, Örnsköldsvikssjukhus, Örnsköldsvik, Sweden; J. Melichercik, Herzzentrum Lahr/Baden, Lahr, Germany; A. Militianu, Carmel Medical Center, Haifa, Israel; T. Minařίk, Fakultnί Nemocnice, Ostrava, Ostrava, Czech Republic; P. Mitro, Faculty Hospital L. Pasteura, Košice, Slovak Republic; A. Mohii-Oskarsson, St Görans Sjukhus, Stockholm, Sweden; H. Mölgaard, Skejby Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark; C. Nimeth, Krankenhaus der Barmherzigen Schwestern Ried, Ried im Innkreis, Austria; T. Nordt, Klinikum Stuttgart Katharinenhospital, Stuttgart, Germany; M. Novák, Fakultní Nemocnice u sv. Anny v Brně, Brno, Czech Republic; K. Nyman, Keski-Suomen Keskussairaala, Jyväskylä, Finland; J.-L. Pasquié, CHU Arnaud de Villeneuve, Montpellier, France; J. Plomp, Tergooi Ziekenhuizen lok. Hilversum, Hilversum, the Netherlands; A. Podczeck-Schweighofer, Sozialmedizinisches Zentrum Süd Kaiser-Franz-Josef-Spital, Vienna, Austria; H. Ramanna, Medisch Centrum Haaglanden, Den Haag, Netherlands; J.M. Rigollaud, Hôpital d'Instruction des Armees Robert Picque, Bordeaux-Armees, France; C. Rorsman, Sjukhuset Varberg, Varberg, Sweden; A. Rötzer, Klinikum Ludwigsburg, Ludwigsburg, Germany; T. Salo, TYKS Raision Sairaala, Raision, Finland; N. Samnieh, Bnai Zion Medical Center, Haifa, Israel; F. Schwertfeger, Spreewaldklinik Lübben, Lübben, Germany; G. Strupp, Klinikum Fulda, Fulda, Germany; H. Sunthorn, Hôpital Cantonal Universitaire, Genève, Switzerland; S. Trinks, Krankenhaus Hietzing, Vienna, Austria; I.C. van Gelder, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands; R. van Mechelen, St Franciscus Hospital Rotterdam, Rotterdam, the Netherlands; R. Ventura, UKE Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany; E. Vester, Evangelisches Krankenhaus Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany; S. Viskin, Tel Aviv Medical Center, Tel Aviv, Israel; P. Visman, Beatrix Ziekenhuis, Gorinchem, the Netherlands; J. Vlašίnová, Fakultnί Nemocnice Brno, Brno, Czech Republic; I. Westbom, Sahlgrenska. Universitetssjukhuset, Göteborg, Sweden; W.B. Winkler, Krankenanstalt der Stadt Wien Rudolfstiftung, Vienna, Austria; J. Woltmann, St Vincenz-Krankenhaus, Menden, Germany.

References

- 1.Serletis A, Rose S, Sheldon AG, Sheldon RS. Vasovagal syncope in medical students and their first-degree relatives. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1965–70. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soteriades ES, Evans JC, Larson MG, Chen MH, Chen L, Benjamin EJ, et al. Incidence and prognosis of syncope. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:878–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanc JJ, L'Her C, Touiza A, Garo B, L'Her E, Mansourati J. Prospective evaluation and outcome of patients admitted for syncope over a 1 year period. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:815–20. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linzer M, Pontinen M, Gold DT, Divine GW, Felder A, Brooks WB. Impairment of physical and psychosocial function in recurrent syncope. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44:1037–43. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90005-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rose MS, Koshman ML, Spreng S, Sheldon R. The relationship between health-related quality of life and the frequency of spells in patients with syncope. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1209–16. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00257-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brignole M, Alboni P, Benditt D, Bergfeldt L, Blanc JJ, Bloch Thomsen PE, et al. Guidelines on management (diagnosis and treatment) of syncope. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:1256–306. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brignole M, Alboni P, Benditt DG, Bergfeldt L, Blanc JJ, Bloch Thomsen PE, et al. Guidelines on management (diagnosis and treatment) of syncope—update 2004: the Task Force on Syncope, European Society of Cardiology. Europace. 2004;6:467–537. doi: 10.1016/j.eupc.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moya A, Sutton R, Ammirati F, Blanc JJ, Brignole M, Dahm JB, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009): the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2631–71. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brignole M, Vardas P, Hoffman E, Huikuri H, Moya A, Ricci R, et al. Indications for the use of diagnostic implantable and external ECG loop recorders. Europace. 2009;11:671–87. doi: 10.1093/europace/eup097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Adopted by the 18th WMA General Assembly, Helsinki, Finland, June 1964, and amended by the 59th WMA General Assembly; October 2008; Seoul. http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html (10 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herzog E, Frankenberger O, Pierce W, Steinberg JS. The SELF pathway for the management of syncope. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2006;5:173–8. doi: 10.1097/01.hpc.0000235984.06110.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farwell DJ, Freemantle N, Sulke AN. Use of implantable loop recorders in the diagnosis and management of syncope. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1257–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brignole M, Menozzi C, Bartoletti A, Giada F, Lagi A, Ungar A, et al. A new management of syncope: prospective systematic guideline-based evaluation of patients referred urgently to general hospitals. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:76–82. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brignole M, Sutton R, Menozzi C, Garcia-Civera R, Moya A, Wieling W, et al. International Study on Syncope of Uncertain Etiology 2 (ISSUE 2) Group. Early application of an implantable loop recorder allows effective specific therapy in patients with recurrent suspected neurally mediated syncope. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1085–92. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartoletti A, Fabiani P, Bagnoli L, Cappelletti C, Cappellini M, Nappini G, et al. Physical injuries caused by a transient loss of consciousness: main clinical characteristics of patients and diagnostic contribution of carotid sinus massage. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:618–24. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farwell DJ, Sulke AN. Does the use of a syncope diagnostic protocol improve the investigation and management of syncope? Heart. 2004;90:52–8. doi: 10.1136/heart.90.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brignole M, Ungar A, Bartoletti A, Ponassi I, Lagi A, Mussi C, et al. Standardized-care pathway vs. usual management of syncope patients presenting as emergencies at general hospitals. Europace. 2006;8:644–50. doi: 10.1093/europace/eul071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaidi A, Clough P, Cooper P, Scheepers B, Fitzpatrick AP. Misdiagnosis of epilepsy: many seizure-like attacks have a cardiovascular cause. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:181–4. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00700-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lombardi F, Calosso E, Mascioli G, Marangoni E, Donato A, Rossi S, et al. Utility of implantable loop recorder (Reveal Plus) in the diagnosis of unexplained syncope. Europace. 2005;7:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.eupc.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krahn AD, Klein GJ, Yee R, Skanes AC. Detection of asymptomatic arrhythmias in unexplained syncope. Am Heart J. 2004;148:326–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solano A, Menozzi C, Maggi R, Donateo P, Bottoni N, Lolli G, et al. Incidence, diagnostic yield and safety of the implantable loop-recorder to detect the mechanism of syncope in patients with and without structural heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1116–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krahn AD, Klein GJ, Norris C, Yee R. The etiology of syncope in patients with negative tilt table and electrophysiological testing. Circulation. 1995;92:1819–24. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.7.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farwell DJ, Freemantle N, Sulke N. The clinical impact of implantable loop recorders in patients with syncope. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:351–6. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]