Abstract

Age is the greatest risk factor for the development of epithelial cancers. In this minireview, we will examine key extracellular matrix and matricellular components, their changes with aging, and discuss how these alterations might influence the subsequent progression of cancer in the aged host. Because of the tight correlation between advanced age and the prevalence of prostate cancer, we will use prostate cancer as the model throughout this minireview.

Keywords: prostate cancer, microenvironment, senescence, extracellular matrix, matricellular proteins

Introduction

Most tissues undergo significant modification with age. For the purposes of this review, the term aged refers to hosts that have reached greater than 75% of their species life expectancy and that generally have a larger percentage of cells (relative to young hosts) defined as senescent in many of their tissues.1-4 Senescent cells, which have ceased replicating but remain metabolically active, as well as normal aged cells influence the microenvironment of tissues. The relative contribution of senescent cells versus normal aged cells in remodeling the microenvironment is speculative, especially in regard to the effect of specific cell types (e.g. endothelial, epithelial, fibroblasts). In this review, we will explore the possible effects of senescent cells as just one of many factors that can alter the microenvironment in an aged host, thereby influencing tumor progression.

Whereas cells have been the focus of most research in tissue aging, it is increasingly appreciated that pervasive changes also occur in the components of the extracellular space.5-8 Modifications in the local environment, in turn, impact cellular functions. As an example, loss of tissue architecture is a defining characteristic of epithelial cancer initiation and progression. Thus an extracellular environment that provides the correct cues can serve as a powerful tumor suppressor—placing cells containing preneoplastic as well as oncogenic mutations into a normal tissue architecture reverts those cells back to a normal phenotype (e.g. polarization of epithelial cancer cells) despite the continued presence of oncogenic mutations. Conversely an environment that is rich in growth promoting mediators can spur on cells containing mutations to develop into cancer.6-8 These processes continually alter the composition of the microenvironment and subsequently influence tumor progression in the aged host.

Within this extracellular environment, the influence of various growth factors has been at the core of cancer research. However, there is increasing interest in the roles of other components during tumor progression. The term “microenvironment” now includes the extracellular matrix (e.g. collagens, laminins), matricellular components, soluble factors (hormones, cytokines, growth factors, enzymes) that are released by resident and circulating cells or transmitted by other organs, and a myriad of cell types (e.g. various immune cell populations, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, epithelial cells).6, 9 Cells use membrane receptors, such as integrins and syndecans, to physically attach to components of the extracellular matrix, including collagens and laminins. These types of receptors, in turn, are connected to the intracellular cytoskeleton network via protein signaling scaffolds. Alterations in the cytoskeleton, due to signaling through cell-matrix receptors, modify gene expression through links to the nuclear matrix and chromatin. Gene expression changes subsequently lead to modifications in the chemical and protein composition of the microenvironment.6

Metastasis of the primary tumor, likewise, is affected by aging. Kaplan, et al elegantly demonstrated that when they replaced young marrow with aged marrow in young irradiated mice, tumor metastases decreased.10 Conversely when they replaced old marrow with young marrow in irradiated older mice, they observed an increase in metastases suggesting that tumor metastases are determined by preparation of a bone-marrow derived “metastatic niche” prior to the arrival of cancer cells and that older marrow is poorer at preparing this niche than younger marrow.10 There are a multitude of factors involved in metastases, including an angiogenic component and differential signaling by the tumor cells themselves. Thus the interactions of tumor cells with the host homeostatic mechanisms are highly variable and complex.11-13 The reasons behind an apparent decrease in metastases in the aged host versus young host are myriad and likely to vary with the type of cancer. In this minireview, we will use prostate cancer as the model and focus on the potential roles of extracellular matrix components during primary tumor progression in the aged host.

Epithelial Cancers and Cellular Senescence

Age-associated epithelial cancers, such as prostate cancer, contribute significantly to morbidity and mortality in the elderly.14 One possible mechanism by which the body defends itself against epithelial cancers is to halt replication of damaged cells by senescence. Although senescence might initially assist in preventing the formation of epithelial tumors, the accrual of senescent cells may ultimately provide a permissive environment that promotes tumor progression.6, 7 In this scenario, once a cell has entered senescence, its transcriptome is altered such that genes associated with inflammation, angiogenesis, and immune cell recruitment/activation are secreted locally.15-18 These cells acquire a unique secretome, which Campisi and colleagues term the “Senescent Associated Secretory Phenotype” (SASP).17, 19 Senescent cells also alter the extracellular matrix directly through changes in structural proteins (e.g. collagens, laminins) as well as the enzymes that regulate their turnover (e.g. MMPs, TIMPs).15, 16, 18, 20 As an example, senescent cells can overexpress specific collagen and laminin chains (e.g. Col I α2, Col IV α3, LM α4, LM β1). At the same time, these cells tend to have greater matrix metalloproteinase activity, suggesting linked biosynthetic and degradative processes.18, 20 Cumulative changes in expression patterns affect not only the senescent cell, but also influence surrounding cells. This viewpoint is supported by studies demonstrating that accumulation of mutations alone is not sufficient to cause cancer; instead cells harboring mutations require a permissive microenvironment in which to progress towards tumorigenicity.6-8, 21, 22

Studies on the role of senescent cells in tumor initiation and progression can appear contradictory depending on which cell type is being examined (fibroblast, epithelial, endothelial, etc) and their subsequent location. For instance, when senescent fibroblasts were co-cultured with pre-malignant epithelial cells, increased proliferation and tumorigenicity of those epithelial cells resulted, both in vitro and in vivo.7, 16, 17, 23 Further Liu and Hornsby reported that when breast cancer cell lines were mixed with senescent fibroblasts and placed in a subcutaneous xenograft model, greater tumorigenicity occurred compared to when breast cancer cells were implanted alone or with non-senescent fibroblasts.18 Intriguingly, when using the kidney-capsule model, the same group found that the presence of senescent fibroblasts did not further enhance angiogenesis or tumor growth relative to the effect of control fibroblasts.24 In our studies using dermal fibroblasts from aged human donors, we observed that cells exhibiting features of senescence (decreased proliferation, slowed migration, positive beta-gal staining) produced growth-promoting chemokines to a greater extent than non-senescent cells from aged human donors.25 More work is needed on how the source of the senescent fibroblasts, as well as the subsequent location of the tumor grafts, influences the resulting growth. Such studies would provide us with a better understanding of the role of senescent fibroblasts in tumor initiation and progression.

Because fibroblasts are the primary cell type in most studies of senescence, the effect of other types (e.g. endothelial, epithelial, and cancer cells) in cancer initiation and progression remains poorly studied. The few studies published, however, often support a role for these other senescent cells in inhibition of tumor initiation and/or progression.17, 20, 26-32 Like fibroblasts, these cells also have a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) and are capable of altering the tumor microenvironment.17, 20 Coppe, et al laser-captured prostate epithelial tumor cells from tissue samples collected during the time of radical prostatectomy and examined them for regulation of mRNA expression of SASP factors: men treated with chemotherapy prior to surgery had increased levels of SASP factors compared to men who did not receive chemotherapy.17 Whether an increase in SASP factors at the time of prostatectomy correlated with a significant difference in time to recurrence or with differences in survival rates was not examined. Moreover, how different senescent cell types modify the microenvironment of the aged host has not been specifically examined. Further studies investigating the role of senescent cells in the tissues of aged cancer patients are warranted and are of potential clinical importance in regard to monitoring patient response to various therapies.

Extracellular Matrix Components

Clinical observations suggest that while aging confers the greatest risk of developing cancer, once initiated, histologically similar tumors often behave less aggressively in the aged.33 This premise was further supported by animal studies in which young and aged mice received identical inocula of tumor cells and were subsequently monitored for tumor growth and aggressiveness.34-37 Proposed mechanisms for differences in cancer behavior have focused on age-related changes in immune mediated responses, increases in apoptosis, and decreases in pathological angiogenesis,33-36 all of which result in a less permissive milieu for tumor growth in an aged relative to a young host.7, 17 In this context, it is important to note that in studies of prostate cancer, cell-specific characteristics can obviate age-related influences on tumor progression.38, 39

In this mini-review studies of age-related alterations of the matrix in normal tissues, and changes in tumor matrix in non-aged hosts, will provide a basis for discussion of several key extracellular components as additional variables in disease progression. As is common in gerontology, it is important to note that for any given matrix component, specific disease states that are more common in the aged might confer changes in a given organ that obviate alterations due to age itself. This mini-review discusses the traditional extracellular matrix proteins, Collagen I and laminin, as well as matricellular components such as thrombospondin 1 (TSP1), SPARC (osteonectin), and the non-sulfated glycosaminoglycan, hyaluronic acid (HA).

Collagen I

Collagen I is a heterotrimeric, fibrillar protein (2 chains of the alpha 1(I) and 1 chain of the alpha 2(I) monomer) that is the major structural extracellular component of most tissues.40-43 Of the more than 25 collagens, Collagen I has been the most extensively examined in aged humans and the consensus is that aging confers a progressive decrease in Collagen I synthesis concurrent with an increase in Collagen I degradation.40, 41 Studies examining mechanisms of decreased collagen I content in aged human tissues have noted that lower levels of fibrogenic growth factors, such as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β),44 contribute to less Collagen I synthesis. At the same time, elevated matrix metalloproteinase activity mediates increased Collagen I degradation. Whether the latter results from an increase in collagenase and other matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) or a decrease in tissues inhibitors of MMPs (TIMPs) is still a matter of debate.45 There are important exceptions to this premise, such as the increased Collagen I deposition that is often noted in aged hearts as a response to hypertension.46, 47 Although not due to aging per se, the observations with respect to cardiac Collagen I underscore the need to use the term “deregulation” to describe many of the changes in the matrix in aged organs.

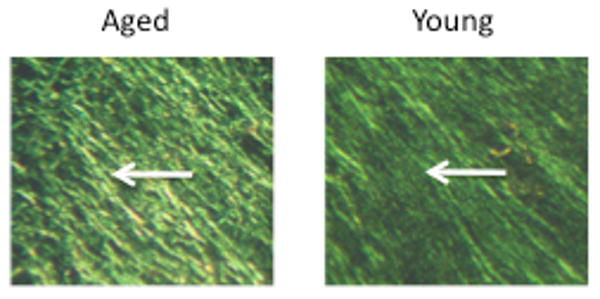

Whether total Collagen I expression is increased or decreased in any given organ, there is consensus that Collagen I is more loose, disorganized, and fragmented in most aged tissues, especially skin (Figure 1). These alterations result in less potential for cellular attachment, which has implications for the support, as well as the function, of resident cells.48 As an example, age-related losses in integrin (primarily α1β1 and α2β1)-collagen binding result in less robust cell adhesion and migration.49 Others have proposed that age-related deficits in the collagen-integrin cascade initiate prostate tumorigenesis.50 Collagen density and stiffness is another parameter that influences tumor cell behavior. Weaver and colleagues have noted that enhanced collagen cross-linking, mediated by lysyl oxidase, promotes growth and invasion by normally pre-malignant human mammary epithelial cells. This same group noted that interactions between adhesion molecules such as filamin A and β1 integrin can alter the cells' response to collagen tension, thereby permitting morphogenesis in high density gels. Taken together these data underscore the ability of the cell, in particular epithelial cells, to adapt to the stiffness of their microenvironment.51, 52 Whether endothelial cells have this same capacity is unclear—although a less dense collagen matrix could facilitate vascular invasion, studies of angiogenesis in most organs have demonstrated decreased capillary density with age.53, 54 Moreover, the implications of age related changes in collagen organization to epithelial tumor growth in general is still a matter of conjecture. As previously noted, in prostate tumors it is cell and tissue specific characteristics that determine progression, irrespective of host age.38, 39

Figure 1. Differences in organization of Collagen I extracted from aged and young mice.

Shown are sections of polymerized Collagen I from aged and young mice tail tendons stained with Picrosirius Red and viewed with a polarized lens. Note Collagen I from aged hosts display looser and less organized polymerization of fibrils (arrow, left panel), while Collagen I from young mice has the expected organized and dense striated pattern (arrow, right panel). Magnification=40×

Aging also increases the number of advanced glycation end products (AGE) present on matrix components, such as collagen. Bartling et al examined collagen from aged rats and found that various lung cancer cell lines had decreased adhesion to and migration through collagen type I and III from old rats compared to young rats.55 The collagen from old (24 month) rats had a significantly higher AGE load than collagen from young (2 months) and adult (12 months) rats. Collagen from young rats that was modified to have increased AGE load also led to decreased adhesion and migration of the cancer cell lines. In addition, the authors found decreased MT3-MMP proteolysis of collagen from old hosts and the AGE-modified collagen compared to the unmodified collagen from young animals.55 We have also noted that Collagen I extracted from aged mice tail tendons differs significantly from that obtained from young mice.56 Moreover, in aged mouse prostates, Collagen I is the most significantly altered extracellular matrix protein at the mRNA, protein, and ultrastructural levels, in a manner similar to aged human skin.57 Normal dermal fibroblasts were able to contract the looser, less organized polymerized form of 3D Collagen I obtained from aged mice better than the Collagen I from young mice. Gene expression profiles of the same resident fibroblasts were significantly altered following exposure to the old Collagen I and reflected the changes in cell-matrix contacts induced by the aged Collagen I relative to young Collagen I.56 Taken together, these studies illustrate the potential utility of using aged mouse models, as well as matrices extracted from aged murine hosts, to examine changes in cell behavior that might be relevant to cell-matrix interactions that occur during tumor growth in vivo.

Laminins

Laminins (LM) are large matrix glycoproteins composed of highly homologous α, β, and γ chains and are the main constituents of basal membranes (a special matrix that separates different cell types from one another, such as endothelial or epithelial cells from the surrounding stroma).58 Laminins are crucial components of the tissue architecture, but are also modulators of cell behavior.58 Examination of laminins, however, has been restricted to alterations during development and tumor progression.58 In part this is because laminins are thought of as developmentally regulated with stable expression in healthy adults. For instance, in fetal prostate LM111 (α1β1γ1, formerly known as Laminin 1) is the predominate laminin, but it is replaced by LM332 (α3β3γ2, formerly known as Laminin 5) as the predominate laminin in adult epithelial basement membranes.59, 60 However, a clue to the importance of laminins in the aged microenvironment may be inferred by examining alterations that occur in the basement membrane in the aged prostate. As men age, the presence of abnormal lesions within the prostate increases.61 Immunohistochemical staining of prostate tissues demonstrates that decreased expression of LM332 occurs as early as prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN).59, 60, 62 Not all PIN lesions become cancerous, but the reasons why are poorly understood. Perhaps the effect of altered laminin expression on the surrounding microenvironment could provide one clue. During progression from PIN to carcinoma, expression of LM332 is lost and remains absent in prostate metastases.60, 63, 64 LM332 is crucial for correct polarization of the epithelial cells, thus an absence of this laminin leads to disorganized epithelial cells. However, Calaluce, et al also demonstrated that alterations in LM332 expression affect expression of a variety of genes, suggesting that the changes in laminin expression in aged prostates may influence the prostate microenvironment not only by altering ECM/cell interactions, but also by directly modifying gene expression and therefore could potentially lead to a microenvironment that is more permissive for tumor growth.65

Some studies suggest that expression of other laminin chains also are altered with increased age of the host. Luo et al and Bavik et al demonstrated that senescent prostate epithelial cells found in regions of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) as well as senescent prostate fibroblasts have increased expression of the laminin α4 and β1 chains.16, 66 The laminin α4 chain is normally present in laminins that are important to vessel architecture; most endothelial cells throughout the body express the laminin α4 chain.58 Normal blood vessel maturation and loss of malignant characteristics are associated with conversion to LM421 (α4β2γ1, formerly known as laminin 9), whereas sprouting and tumor blood vessels express LM411 (α4β1γ1, formerly known as laminin-8).67 In a cell model of senescent prostate cancer cells, we have found increased expression of both the laminin α4 and β2 chains.20 Overexpressing both chains in prostate cancer cell lines decreased tumor growth in vivo, while overexpressing either chain alone resulted in increased tumor growth. In addition, overexpression of the laminin α4 chain alone resulted in increased levels of collagen deposition and increased microvessel density in the tumors suggesting that alterations in laminins influence reorganization of the matrix as well as infiltration of other cell types, including endothelial cells. Wu et al demonstrated that the ability of immune cells to infiltrate tissue sites might also be influenced by laminin composition. In a mouse model of brain inflammation, disease-associated CD4+ T cells had markedly lower infiltration through endothelial basement membranes containing only LM511 rather than the usual LM411. However, the infiltration of other immune cells, such as macrophages and CD8+ T cells, was not effected by the presence of LM511.68 By extrapolation, increased levels of the laminin α4 chain without an increase in the laminin β2 chain in aged prostates may enhance the infiltration of regulatory CD4+ T cells, thereby altering the microenvironment into one that more favorably supports tumor growth. Thus, in the aged host, accumulation of senescent cells could have a dichotomous function on tumor initiation and progression depending on which laminins are expressed.

Matricellular Components

The term “matricellular” refers to components of the extracellular space that primarily regulate cell function without providing significant structural support. The “matricellular” designation implies a protein has a tremendous range of effects, many of which are contextual (i.e., dependent upon the local milieu).69 Although few have been investigated with respect to tumors in the aged host, the proteins Thrombospondin 1 (TSP1) and SPARC (osteonectin) have been examined separately in aging and cancer biology. For the purposes of this review and its focus on prostate cancer, we will also include the non-sulfated glycosaminoglycan, hyaluronan (HA).

Thrombospondin 1

Thrombospondin 1 (TSP1) is one of several members of a family of large trimeric glycoproteins that are classically matricellular in character. TSP1 is of greatest interest due to its ability to inhibit endothelial cell functions and angiogenesis.70, 71 TSP1 expression is increased in most aged cells and is thought to contribute to decreased angiogenesis in aged tissues, such as the kidney, in their basal state.72 Moreover, the increase in TSP1 in aged organs is presumed to play a role in deficient blood vessel formation during tissue repair in older hosts.54, 73

Higher levels of TSP1 have been postulated to decrease tumor angiogenesis, thereby slowing tumor growth. TSP1 inhibits blood vessel formation by blocking pro-angiogenic mediators (such as the potent vasodilator nitric oxide, which is already deficient in aged tissues), growth factor mediated functions (such as proliferation and migration), and enhancing apoptosis of activated endothelial cells. 75 TSP1 has additional influences on other cells in the microenvironment by modulating the balance of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors, the TIMPs.76 The negative effects of TSP1 on endothelial cell functions have resulted in great interest in the role of this glycoprotein during tumor progression. In many cancers, TSP1's presence is associated with a non-angiogenic phenotype and tumor regression; conversely, the absence of TSP1 expression is correlated with an angiogenic switch and metastases.70, 71

Expression of TSP1 is highly regulated by cellular and extracellular mediators as well as unexpected compounds including certain cholesterol lowering agents.77 In prostate cancer cell lines, the tumor suppressive β1C integrin increases TSP1 expression; while at the same time androgens repress TSP1 transcription.75, 78 The influence of androgens on TSP1 expression and subsequent tumor vascularity and growth depends on the duration of TSP1 exposure. Androgen withdrawal initially leads to increases in TSP1 and vessel regression; however, with continued exposure prostate cancer angiogenesis and growth continue despite persistently high levels of TSP1.75 Similar results have been reported in other cancers: persistently high levels of TSP1 in the breast tumor stroma ultimately result in disease progression, an effect that may result from increased expression of VEGF.79 These multiple effects have dampened enthusiasm for the use of TSP1 in clinical intervention studies.

SPARC

SPARC is a small, secreted glycoprotein that is highly expressed in injured and inflamed tissues. Accordingly, high levels of SPARC are found in many cell types and in most aged organs. The absence of a defined receptor and a clear understanding of its functional significance have led some to propose that SPARC is a general marker of a stress response and subsequent cellular activation.80 Studies in vitro indicate SPARC can delay early collagen initiation.81, 82 However, the association of SPARC with collagen synthesis and processing in vivo has suggested it is a beneficial, but not necessary, variable in structural matrix assembly and organization.83 Interestingly, we have noted that young fibroblasts secrete more SPARC when placed in aged, relative to young, 3D collagen I. 56 It is possible that the increase in SPARC reflects the cells' response to the looser, less organized aged matrix.

As a result of the tight link between SPARC expression and remodeling tissues, it is not surprising to note a differential increase in the expression of SPARC during progression of prostate cancer.70-84 In prostate metastases to bone, cathepsin K and other mediators are thought to increase the expression of SPARC, thereby further inducing boney involvement with tumor cells.85 Intact SPARC might inhibit the angiogenic response by impairing proper collagen alignment and blocking pro-angiogenic growth factors.86 At the same time it has been reported that cleaved SPARC facilitates vessel growth by enhancing endothelial cell proliferation.87, 88 However, in young SPARC-null versus wild-type counterparts, increases in angiogenic invasion were found in the SPARC-null mice in a sub-dermal sponge model. In aged hosts, differences in fibrovascular migration and vessel formation exhibited by SPARC-null versus wild-type mice were no longer apparent. Hence, the role of SPARC in the angiogenic response was presumably obviated by age-related deficits in cellular functions and loss of pro-angiogenic mediators, such as VEGF.89

The relative ease by which in vivo SPARC expression can be manipulated has resulted in examination of its specific effects in the initiation, progression, and metastases of many tumors. After decades of examination it is clear that SPARC's influence, like that of aging, is dependent on the tumor cell type and the specific microenvironment of the host.88, 90 In a TRAMP model of spontaneous prostate tumors, modulation of SPARC in mice from a mixed genetic background did not effect prostate tumor initiation, progression, or metastases.69, 91 In contrast, when Said et al crossed TRAMP mice with SPARC-null mice on a pure C57/Bl6 background, they reported that prostate cancer progression was more aggressive and resulted in a greater number of metastases in TRAMP/SPARC-/- mice compared to TRAMP/SPARC+/+ mice.92 Furthermore, the TRAMP/SPARC-/- mice demonstrated decreased levels of stromal collagen I and III deposition within the adenocarcinomas, enhanced MMP-2 and -9 activity in tumor lysates, increased levels of angiogenic factors, and increased microvascular density compared to TRAMP/SPARC+/+ mice.92 These changes are similar to those noted in pancreatic cancer and ovarian cancer cell lines placed in SPARC-null versus wild-type mice.88, 93 These data suggest that in certain microenvironments, SPARC acts as a tumor suppressor and is anti-angiogenic. It is possible that much of SPARC's function is dependent on the status of Collagen I: if both are highly expressed the resulting extracellular architecture could provide greater stability against tumor progression.

Hyaluronan

Hyaluronan (HA) is a large, unbranched polymer of the disaccharide glucuronic acid/N-acetylglucosamine. A normal constituent of tissues, native HA is comprised of from 2,000–25,000 disaccharides with molecular masses of 106–107.94 HA's size and affinity for water promotes its binding and organization of other ECM macromolecules, thereby mediating ECM assembly and homeostasis. The relationship between HA and aging is not well defined and appears to vary among, as well as within, tissues depending upon exogenous exposures, such as UV light. Moreover, many of the studies have been performed on cells aged in vitro, an important but not universally accepted model of cellular aging. Accurate measures of changes with age are also complicated by decreased extractability and impaired organization of HA with aging.95-97 Despite all of these considerations it is generally accepted that young cells synthesize more newly formed HA than their aged counterparts in response to injury as well as HYAL activity.98, 99, 100. At the same time it is thought that HA content may accumulate with age as a result of increased half-life as well as less efficient degradation.100

HA is produced by prostate tumor cells as well as the stroma that surround tumors. It is generally accepted that HA accumulation is a poor prognostic indicator in prostate cancer and predicts unfavorable outcomes including metastases.101, 102, 103 HA content is regulated by at least 3 HA synthases (HAS-1, -2, -3), which differ in tissue distribution, rate of HA synthesis, and size of HA produced.104-106 Tumor cell lines that overexpress HAS-2 and -3 show increased tumorigenesis; cell lines with HAS-2 and -3 suppressed by antisense oligos or siRNA exhibited reduced tumorigenicity.95, 96, 107, 108

HA facilitates tumor progression by multiple mechanisms. HA influences ECM porosity by binding to collagen I as well as versican and fibrin, thereby increasing tumor cell motility in vitro.109-111 HA also enhances cell migration via CD44-dependent mechanisms, including those that increase MMP activity.100 Accordingly, modification of CD44 expression is gaining increasing interest as a target in prostate cancer therapy.112-114 The presence of HA also induces signaling complexes that contain activated ErbB2,115 a transmembrane protein that promotes tumor malignancy and drug resistance.

HA may also promote tumor growth by enhancing tumor vascularization. High molecular weight (MW) HA is anti-angiogenic;116, 117 however, low MW oligosaccharides of HA stimulate angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo.117-119 Correspondingly degradation of high MW HA by hyaluronidase (HYAL) enhances angiogenesis in tumors and correlates with cancer invasiveness.120, 121 Tumor extracts contain pro-angiogenic HA oligomers that may arise via digestion of HA by tumor-associated HYALs.106, 122, 123 Of particular note is HYAL-1, which is implicated in prostate cancer progression and recurrence.102, 124, 125

The effect of age on HA metabolism into high and low MW forms is as poorly understood as age-related changes in total HA content and organization. Middle-aged rat skin appears to express HA of higher MW, but the influence of age on the ratio of high MW to low MW HA has not been examined in detail.126 It is probable that each organ has its own regulation of HA expression with respect to both amount and size distribution. Consequently, additional determination of age related effects on HA turnover and size are likely of greater significance in highlighting factors associated with cancer progression, than measures of total HA expression in the tumor microenvironment.

Conclusion

Body-wide levels of factors associated with tumor progression might decrease with aging, but their level of expression can increase locally. The prostate provides a unique model for this paradigm. For example, senescent cells in the prostate are more prevalent with host age and display a transcriptome and secretome that appears to encourage cellular proliferation, inflammation, and angiogenesis. Matricellular components (eg. TSP1, SPARC, and HA) as well as extracellular matrix proteins (eg. collagens, laminins, and their associated integrins) are modulated by aged cells, but in a locally specific manner. These components can interact with resident cells to further alter the microenvironment to one that promotes epithelial tumor growth (Table 1). Consequently, while tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastases are often impaired in the aged host, the local microenvironment of primary epithelial tumors such as the prostate may be as supportive of tumor progression as that found in the young host.

Table 1. Age-related changes in ECM components and potential effects on tumor progression.

| Promoting | Inhibiting | |

|---|---|---|

| Collagen I | Increased stiffness | Decreased synthesis/density Increased fragmentation |

| Laminin | Cleavage and/or loss of LM332 (α3β3γ2) Increased expression of LM α4 and β1 chains |

LM332 (α3β3γ2) expression with polarization of epithelial cells Increased expression of LM α4 and β2 chains |

| TSP1 | Long term interactions with VEGF | Increased expression– inhibition of angiogenesis via multiple mechanisms |

| SPARC | Interactions with Collagen I synthesis and processing Cleavage into pro-angiogenic forms |

Increased expression– inhibition of GF effects on endothelial cells |

| Hyaluronan | Increases in total Hyaluronan | Decrease in HA turnover/generation of LMW-HA forms |

Acknowledgments

Amy D. Bradshaw, PhD, and Mamatha Damodarasamy, MS, for assistance with the manuscript. We also acknowledge the following grant support: NIH grants U54 CA126540 and R01 AG015837 and the Prostate Cancer Research Program of the Department of Defense W81XWH-09-1-0177.

References

- 1.Nadon NL. Of mice and monkeys: National Institute on Aging resources supporting the use of animal models in biogerontology research. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:813–5. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.8.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dekker P, Maier AB, van Heemst D, de Koning-Treurniet C, Blom J, Dirks RW, Tanke HJ, Westendorp RG. Stress-induced responses of human skin fibroblasts in vitro reflect human longevity. Aging Cell. 2009;8:595–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herbig U, Ferreira M, Condel L, Carey D, Sedivy J. Cellular senescence in aging primates. Science. 2006;311:1257. doi: 10.1126/science.1122446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hornsby P. Cellular senescence and tissue aging in vivo. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57A:B125–B256. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.7.b251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Labat-Robert J, Robert L. The effect of cell-matrix interactions and aging on the malignant process. Adv Cancer Res. 2007;98:221–59. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(06)98007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson C, Bissell M. Of extracellular matrix, scaffold, and signaling: tissue architecture regulates development, homeostasis, and cancer. Ann Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:287–309. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campisi J. Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: good citizens, bad neighbors. Cell. 2005;120:513–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bissell M, Radisky D. Putting tumours in context. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:46–54. doi: 10.1038/35094059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan T, Coussens L. Humoral immunity, inflammation and cancer. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:209–16. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplan R, Rafii S, Lyden D. Preparing the “soil”: the premetastatic niche. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11089–93. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langley R, Fidler I. Tumor cell-organ microenvironment interactions in the pathogenesis of cancer metastasis. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:297–321. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bierie B, Moses H. Gain or loss of TGF-beta signaling in mammary carcinoma cells can promote metastasis. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:3319–27. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.20.9727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giampieri S, Manning C, Hooper S, Jones L, Hill C, Sahai E. Localized and reversible TGF-beta signalling switches breast cancer cells from cohesive to single cell motility. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1287–96. doi: 10.1038/ncb1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun M. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang H, Pan KH, Cohen S. Senescence-specific gene expression fingerprints reveal cell-type-dependent physical clustering of up-regulated chromosomal loci. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3251–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2627983100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bavik C, Coleman I, Dean J, Knudsen B, Plymate S, Nelson P. The gene expression program of prostate fibroblast senescence modulates neoplastic epithelial cell proliferation through paracrine mechanisms. Cancer Res. 2006;66:794–802. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coppe JP, Patil C, Rodier F, Sun Y, Munoz D, Goldstein J, Nelson P, Desprez PY, Campisi J. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:2853–68. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu D, Hornsby PJ. Senescent human fibroblasts increase the early growth of xenograft tumors via matrix metalloproteinase secretion. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3117–26. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodier F, Coppe JP, Patil C, Hoeijmakers W, Munoz D, Raza S, Freund A, Campeau E, Davalos A, Campisi J. Persistent DNA damage signalling triggers senescence-associated inflammatory cytokine secretion. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:973–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sprenger C, Drivdahl R, Woodke L, Eyman D, Reed M, Carter W, Plymate S. Senescence-induced alterations of laminin chain expression modulate tumorigenicity of prostate cancer cells. Neoplasia. 2008;10:1350–61. doi: 10.1593/neo.08746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bissell M, Rizki A, Mian I. Tissue architecture: the ultimate regulator of breast epithelial function. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:753–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gosselin K, Martien S, Pourtier A, Vercamer C, Ostoich P, Morat L, Sabatier L, Duprez L, T'Kint de Roodenbeke C, Gilson E, Malaquin N, Wernert N, et al. Senescence-associated oxidative DNA damage promotes the generation of neoplastic cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7917–25. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawrenson K, Grun B, Benjamin E, Jacobs I, Dafou D, Gayther S. Senescent fibroblasts promote neoplastic transformation of partially transformed ovarian epithelial cells in a three-dimensional model of early stage ovarian cancer. Neoplasia. 2010;12:317–25. doi: 10.1593/neo.91948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu D, Hornsby P. Fibroblast stimulation of blood vessel development and cancer cell invasion in a subrenal capsule xenograft model: stress-induced premature senescence does not increase effect. Neoplasia. 2007;9:418–26. doi: 10.1593/neo.07205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eyman D, Damodarasamy M, Plymate SR, Reed MJ. CCL5 secreted by senescent aged fibroblasts induces proliferation of prostate epithelial cells and expression of genes that modulate angiogenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2009;220:376–81. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collado M, Serrano M. Senescence in tumours: evidence from mice and humans. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:51–7. doi: 10.1038/nrc2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang BD, Broude E, Dokmanovic M, Zhu H, Ruth A, Xuan Y, Kandel E, Lausch E, Christov K, Roninson I. A senescence-like phenotype distinguishes tumor cells that undergo terminal proliferation arrest after exposure to anticancer agents. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3761–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shay J, Roninson I. Hallmarks of senescence in carcinogenesis and cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2004;23:2919–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmitt C. Senescence, apoptosis and therapy – cutting the lifelines of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:285–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwarze S, Fu V, Desotelle J, Kenowski M, Jarrard D. The identification of senescence-specific genes during the induction of senescence in prostate cancer cells. Neoplasia. 2005;7:816–23. doi: 10.1593/neo.05250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xue W, Zender L, Meithing C, Dickins R, Hernando E, Krizhanovsky V, Cordon-Cardo C, Lowe S. Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by p53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. Nature. 2007;445:656–60. doi: 10.1038/nature05529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Majumder P, Grisanzio C, O'Connell F, Barry M, Brito J, Xu Q, Guney I, Berger R, Herman P, Bikoff R, Fedele G, Baek WK, et al. A prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia-dependent p27Kip1 checkpoint induces senescence and inhibits cell proliferation and cancer progression. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:146–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.06.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ershler W. Why tumors grow more slowly in old people. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1986;77:837–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kreisle R, Stebler B, Ershler W. Effect of host age on tumor-associated angiogenesis in mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82:44–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pili R, Guo Y, Chang J, Nakanishi H, Martin G, Passaniti A. Altered angiogenesis underlying age-dependent changes in tumor growth. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1303–14. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.17.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Itzhaki O, Skutelsky E, Kaptzan T, Siegal A, Sinai J, Schiby G, Michowitz M, Huszar M, Leibovici J. Decreased DNA ploidy may constitute a mechanism of the reduced malignant behavior of B16 melanoma in aged mice. Exp Gerontol. 2008;43:164–75. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaptzan T, Skutelsky E, Itzhaki O, Sinai J, Michowitz M, Yossipov Y, Schiby G, Leibovici J. Age-dependent differences in the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy in C57BL and AKR mouse strains. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:1035–48. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gronberg H, Damber JE, Jonsson H, Lenner P. Patient age as a prognostic factor in prostate cancer. J Urol. 1994;152:892–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32601-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reed M, Karres N, Eyman D, Cruz A, Brekken R, Plymate S. The effects of aging on tumor growth and angiogenesis are tumor-cell dependent. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:753–60. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chung L, Baseman A, Assikis V, Zhau H. Molecular insights into prostate cancer progression: the missing link of tumor microenvironment. J Urology. 2005;173:10–20. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000141582.15218.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shuster S, Black MM, McVitie E. The influence of age and sex on skin thickness, skin collagen and density. Br J Dermatol. 1975;93:639–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1975.tb05113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heino J. The collagen family members as cell adhesion proteins. Bioessays. 2007 Oct;29(10):1001–10. doi: 10.1002/bies.20636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gordon M, Hahn R. Collagens. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;339:247–57. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0844-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ashcroft G, Dodsworth J, van Boxtel E, Tarnuzzer R, Horan M, Schultz G, Ferguson M. Estrogen accelerates cutaneous wound healing associated with an increase in TGF-β1 levels. Nat Med. 1997;3:1209–15. doi: 10.1038/nm1197-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hornebeck W, Emonard H, Monboisee JC, Bellon G. Matrix-directed regulation of pericellular proteolysis and tumor progression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:231–41. doi: 10.1016/s1044-579x(02)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gazoti Debessa C, Mesiano Maifrino L, Rodrigues de Souza R. Age related changes of the collagen network of the human heart. Mech Ageing Dev. 2001;122:1049–58. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00238-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lakatta EG. Arterial aging is risky. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:1321–2. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91145.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fisher GJ, Varani J, Voorhees JJ. Looking older: fibroblast collapse and therapeutic implications. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:666–72. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.5.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reed M, Ferara N, Vernon R. Impaired migration, integrin function, and actin cytoskeletal organization in dermal fibroblasts from a subset of aged human donors. Mech Ageing Dev. 2001;122:1203–20. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00260-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gorlov IP, Byun J, Gorlova OY, Aparicio AM, Efstathiou E, Logothetis CJ. Candidate pathways and genes for prostate cancer: a meta-analysis of gene expression data. BMC Med Genomics. 2009;2:48. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-2-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levental KR, Yu H, Kass L, Lakins JN, Egeblad M, Erler JT, Fong SF, Csiszar K, Giaccia A, Weninger W, Yamauchi M, Gasser DL, et al. Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell. 2009;139:891–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gehler S, Baldassarre M, Lad Y, Leight J, Wozniak M, Riching K, Eliceiri K, Weaver V, Calderwood D, Keely P. Filamin A-beta 1 integrin complex tunes epithelial cell response to matrix tension. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:3224–38. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rivard A, Fabre J, Silver M, Chen D, Murohara T, Kearney M, Magner M, Asahara T, Isner J. Age-dependent impairment of angiogenesis. Circulation. 1999;99:111–20. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sadoun E, Reed M. Impaired angiogenesis in aging is associated with alterations in vessel density, matrix composition, inflammatory response, and growth factor expression. J Hist Cytochem. 2003;51:1119–30. doi: 10.1177/002215540305100902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bartling B, Desole M, Rohrbach S, Silber RE, Simm A. Age-associated changes of extracellular matrix collagen impair lung cancer cell migration. FASEB J. 2009;23:1510–20. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-122648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Damodarasamy M, Vernon RB, Karres N, Chang CH, Bianchi-Frias D, Nelson PS, Reed MJ. Collagen Extracts Derived From Young and Aged Mice Demonstrate Different Structural Properties and Cellular Effects in Three-Dimensional Gels. J Geront:Biol Sci Mar. 2010;65(3):209–18. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bianchi-Frias D, Vakar-Lopez F, Coleman I, Reed M, Plymate S, Nelson P. The effects of aging on the molecular and cellular composition of the prostate microenvironment. PLoS One. 2010 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012501. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Patarroyo M, Tryggvason K, Virtanen I. Laminin isoforms in tumor invasion, angiogenesis and metastasis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:197–207. doi: 10.1016/S1044-579X(02)00023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brar P, Dalkin B, Weyer C, Sallam K, Virtanen I, Nagle R. Laminin alpha-1, alpha-3, and alpha-5 chain expression in human prepubetal benign prostate glands and adult benign and malignant prostate glands. Prostate. 2003;55:65–70. doi: 10.1002/pros.10206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nagle R. Role of the extracellular matrix in prostate carcinogenesis. J Cell Biochem. 2004;91:36–40. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brawer M. Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia: an overview. Rev Urol. 2005;7:S11–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hao J, Yang Y, McDaniel K, Dalkin B, Cress A, Nagle R. Differential expression of laminin 5 (α3β3γ2) by human malignant and normal prostate. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:1341–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Udayakumar T, Chen M, Bair E, von Bredow D, Cress A, Nagle R, Bowden G. Membrane type-1-matrix metalloproteinase expressed by prostate carcinoma cells cleaves human laminin-5 β3 chain and induces cell migration. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2292–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tripathi M, Nandana S, Yamashita H, Ganesan R, Kirchhofer D, Quaranta V. Laminin-332 is a substrate for hepsin, a protease associated with prostate cancer progression. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:30576–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802312200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Calaluce R, Kunkel M, Watts G, Schmelz M, Hao J, Barrera J, Gleason-Guzman M, Isett R, Fitchmun M, Bowden G, Cress A, Futscher B, et al. Laminin-5-mediated gene expression in human prostate carcinoma cells. Mol Carcinog. 2001;30:119–29. doi: 10.1002/1098-2744(200102)30:2<119::aid-mc1020>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Luo J, Dunn T, Ewing C, Sauvageot J, Chen Y, Trent J, Isaacs W. Gene expression signature of benign prostatic hyperplasia revealed by cDNA microarray analysis. Prostate. 2002;51:189–200. doi: 10.1002/pros.10087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhou Z, Doi M, Wang J, Cao R, Liu B, Chan K, Kortesmaa J, Sorokin L, Cao Y, Tryggvason K. Deletion of laminin-8 results in increased tumor neovascularization and metastasis in mice. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4059–63. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu C, Ivars F, Anderson P, Hallmann R, Vestweber D, Nilsson P, Robenek H, Tryggvason K, Song J, Korpos E, Loser K, Beissert S, et al. Endothelial basement membrane laminin alpha 5 selectively inhibits T lymphocyte extravasation into the brain. Nat Med. 2009;15:519–27. doi: 10.1038/nm.1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Elola M, Wolfenstein-Todel C, Troncoso M, Vasta G, Rabinovich G. Galectins: matricellular glycan-binding proteins linking cell adhesion, migration, and survival. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:1679–700. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7044-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Naumov G, Bender E, Zurakowski D, Kang S, Sampson D, Flynn E, Watnick R, Straume O, Akslen L, Folkman J, Almog N. A model of human tumor dormancy: an angiogenic switch from the nonangiogenic phenotype. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:316–25. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zaslavsky A, Baek KH, Lynch RC, Short S, Grillo J, Folkman J, Italiano JE, Jr, Ryeom S. Platelet-derived thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) is a critical negative regulator and potential biomarker of angiogenesis. Blood. 2010 doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-242065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kang DH, Anderson S, Kim YG, Mazzalli M, Suga S, Jefferson JA, Gordon KL, Oyama TT, Hughes J, Hugo C, Kerjaschki D, Schreiner GF, et al. Impaired angiogenesis in the aging kidney: vascular endothelial growth factor and thrombospondin-1 in renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:601–11. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.22087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Agah A, Kyriakides TR, Letrondo N, Bjorkblom B, Bornstein P. Thrombospondin 2 levels are increased in aged mice: consequences for cutaneous wound healing and angiogenesis. Matrix Biol. 2004;22:539–47. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Isenberg JS, Hyodo F, Pappan LK, Abu-Asab M, Tsokos M, Krishna MC, Frazier WA, Roberts DD. Blocking thrombospondin-1/CD47 signaling alleviates deleterious effects of aging on tissue responses to ischemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2582–8. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.155390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Colombel M, Filleur S, Fournier P, Merle C, Guglielmi J, Courtin A, Degeorges A, Serre C, Bouvier R, Clezardin P, Cabon F. Androgens repress the expression of the angiogenesis inhibitor thrombospondin-1 in normal and neoplastic prostate. Cancer Res. 2005;65:300–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.John AS, Hu X, Rothman VL, Tuszynski GP. Thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) up-regulates tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) production in human tumor cells: exploring the functional significance in tumor cell invasion. Exp Mol Pathol. 2009;87:184–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Solomon KR, Pelton K, Boucher K, Joo J, Tully C, Zurakowski D, Schaffner CP, Kim J, Freeman MR. Ezetimibe is an inhibitor of tumor angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:1017–26. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Goel H, Moro L, Murphy-Ullrich J, Hsieh CC, Wu CL, Jiang Z, Languino L. Beta 1 integrin cytoplasmic variants differentially regulate expression of the antiangiogenic extracellular matrix protein thrombospondin 1. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5374–82. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fontana A, Filleur S, Guglielmi J, Frappart L, Bruno-Bossio G, Boissier S, Cabon F, Clezardin P. Human breast tumors override the antiangiogenic effect of stromal thrombospondin-1 in vivo. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:689–91. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sage E, Clark C. A prototypic matricellular protein in the tumor microenvironment--where there's SPARC, there's fire. J Cell Biochem. 2008;104:721–32. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Giudici C, Raynal N, Wiedemann H, Cabral WA, Marini JC, Timpl R, Bachinger HP, Farndale RW, Sasaki T, Tenni R. Mapping of SPARC/BM-40/osteonectin-binding sites on fibrillar collagens. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:19551–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710001200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hohenester E, Sasaki T, Giudici C, Farndale RW, Bachinger HP. Structural basis of sequence-specific collagen recognition by SPARC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18273–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808452105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bradshaw AD, Baicu CF, Rentz TJ, Van Laer AO, Bonnema DD, Zile MR. Age-dependent alterations in fibrillar collagen content and myocardial diastolic function: role of SPARC in post-synthetic procollagen processing. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H614–22. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00474.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Thomas R, True L, Bassuk J, Lange P, Vessella R. Differential expression of osteonectin/SPARC during human prostate cancer progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1140–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Podgorski I, Linebaugh BE, Koblinski JE, Rudy DL, Herroon MK, Olive MB, Sloane BF. Bone marrow-derived cathepsin K cleaves SPARC in bone metastasis. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:1255–69. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kupprion C, Motamed K, Sage EH. SPARC (BM-40, osteonectin) inhibits the mitogenic effect of vascular endothelial growth factor on microvascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29635–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sage EH, Reed MJ, Funk SE, Truong T, Steadele M, Puolakkainen P, Maurice DH, Bassuk JA. Cleavage of the matricellular protein SPARC by matrix metalloproteinase 3 produces polypeptides that influence angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37849–57. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302946200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Arnold S, Brekken R. SPARC: a matricelluar regulator of tumorigenesis. J Cell Commun Signal. 2009;3:255–73. doi: 10.1007/s12079-009-0072-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Reed MJ, Bradshaw A, Shaw M, Sadoun E, Han N, Ferara N, Funk SE, Puolakkainen P, Sage EH. Enhanced angiogenesis characteristic of SPARC-null mice disappears with age. J Cell Physiol. 2005;204:800–7. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Clark CJ, Sage EH. A prototypic matricellular protein in the tumor microenvironment--where there's SPARC, there's fire. J Cell Biochem. 2008;104:721–32. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wong SY, Crowley D, Bronson RT, Hynes RO. Analyses of the role of endogenous SPARC in mouse models of prostate and breast cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2008;25:109–18. doi: 10.1007/s10585-007-9126-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Said N, Frierson H, Chernauskas D, Conaway M, Motamed K, Theodorescu D. The role of SPARC in the TRAMP model of prostate carcinogenesis and progression. Oncogene. 2009;28:3487–98. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bull Phelps S, Carbon J, Miller A, Castro-Rivera E, Arnold S, Brekken R, Lea J. Secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine as a regulator of murine ovarian cancer growth and chemosensitivity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:180.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Toole BP. Hyaluronan: from extracellular glue to pericellular cue. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:528–39. doi: 10.1038/nrc1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Simpson MA, Reiland J, Burger SR, Furcht LT, Spicer AP, Oegema TR, Jr, McCarthy JB. Hyaluronan synthase elevation in metastatic prostate carcinoma cells correlates with hyaluronan surface retention, a prerequisite for rapid adhesion to bone marrow endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17949–57. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010064200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Simpson MA, Wilson CM, McCarthy JB. Inhibition of prostate tumor cell hyaluronan synthesis impairs subcutaneous growth and vascularization in immunocompromised mice. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:849–57. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64245-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Simpson RM, Meran S, Thomas D, Stephens P, Bowen T, Steadman R, Phillips A. Age-related changes in pericellular hyaluronan organization leads to impaired dermal fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:1915–28. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Meyer LJ, Stern R. Age-dependent changes of hyaluronan in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:385–9. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12371800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ghersetich I, Lotti T, Campanile G, Grappone C, Dini G. Hyaluronic acid in cutaneous intrinsic aging. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:119–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1994.tb01540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Robert L, Robert AM, Renard G. Biological effects of hyaluronan in connective tissues, eye, skin, venous wall. Role in aging. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lipponen P, Aaltomaa S, Tammi R, Tammi M, Agren U, Kosma VM. High stromal hyaluronan level is associated with poor differentiation and metastasis in prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:849–56. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00448-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gomez CS, Gomez P, Knapp J, Jorda M, Soloway MS, Lokeshwar VB. Hyaluronic acid and HYAL-1 in prostate biopsy specimens: predictors of biochemical recurrence. J Urol. 2009;182:1350–6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.06.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bharadwaj A, Kovar J, Loughman E, Elowsky C, Oakley G, Simpson M. Spontaneous metastatis of prostate cancer is promoted by excess hyaluronan synthesis and processing. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:1027–36. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Weigel PH, Hascall VC, Tammi M. Hyaluronon synthases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13997–4000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.13997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Harris EN, Kyosseva SV, Weigel JA, Weigel PH. Expression, processing, and glycosaminoglycan binding activity of the recombinant human 315-kDa hyaluronic acid receptor for endocytosis (HARE) J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2785–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607787200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Stern R. Hyaluronan metabolism: a major paradox in cancer biology. Pathol Biol. 2005;53:372–82. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Liu N, Gao F, Han Z, Xu X, Underhill CB, Zhang L. Hyaluronan synthase 3 overexpression promotes the growth of TSU prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5207–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kosaki R, Watanabe K, Yamaguchi Y. Overproduction of hyaluronan by expression of the hyaluronan synthase Has2 enhances anchorage-independent growth and tumorigenicity. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1141–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hayen W, Goebeler M, Kumar S, Riessen R, Nehls V. Hyaluronan stimulates tumor cell migration by modulating the fibrin fiber architecture. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 13):2241–51. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.13.2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Annabi B, Thibeault S, Moumdjian R, Beliveau R. Hyaluronan cell surface binding is induced by type I collagen and regulated by caveolae in glioma cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21888–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313694200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ricciardelli C, Russell DL, Ween MP, Mayne K, Suwiwat S, Byers S, Marshall VR, Tilley WD, Horsfall DJ. Formation of hyaluronan- and versican-rich pericellular matrix by prostate cancer cells promotes cell motility. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:10814–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606991200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Subramaniam V, Gardner H, Jothy S. Soluble CD44 secretion contributes to the acquisition of aggressive tumor phenotype in human colon cancer cells. Exp Mol Pathol. 2007;83:341–6. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Handorean AM, Yang K, Robbins EW, Flaig TW, Iczkowski KA. Silibinin suppresses CD44 expression in prostate cancer cells. Am J Transl Res. 2009;1:80–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yang K, Tang Y, Habermehl GK, Iczkowski KA. Stable alterations of CD44 isoform expression in prostate cancer cells decrease invasion and growth and alter ligand binding and chemosensitivity. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ghatak S, Misra S, Toole BP. Hyaluronan constitutively regulates ErbB2 phosphorylation and signaling complex formation in carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8875–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410882200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.West DC, Hampson IN, Arnold F, Kumar S. Angiogenesis induced by degradation products of hyaluronic acid. Science. 1985;228:1324–6. doi: 10.1126/science.2408340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.West DC, Kumar S. Hyaluronan and angiogenesis. Ciba Found Symp. 1989;143:187–201. doi: 10.1002/9780470513774.ch12. discussion -7, 81-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Rahmanian M, Pertoft H, Kanda S, Christofferson R, Claesson-Welsh L, Heldin P. Hyaluronan oligosaccharides induce tube formation of a brain endothelial cell line in vitro. Exp Cell Res. 1997;237:223–30. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Montesano R, Kumar S, Orci L, Pepper MS. Synergistic effect of hyaluronan oligosaccharides and vascular endothelial growth factor on angiogenesis in vitro. Lab Invest. 1996;75:249–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Liu D, Pearlman E, Diaconu E, Guo K, Mori H, Haqqi T, Markowitz S, Willson J, Sy MS. Expression of hyaluronidase by tumor cells induces angiogenesis in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7832–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Paiva P, Van Damme MP, Tellbach M, Jones RL, Jobling T, Salamonsen LA. Expression patterns of hyaluronan, hyaluronan synthases and hyaluronidases indicate a role for hyaluronan in the progression of endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;98:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kovar JL, Johnson MA, Volcheck WM, Chen J, Simpson MA. Hyaluronidase expression induces prostate tumor metastasis in an orthotopic mouse model. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1415–26. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Stern R. Hyaluronidases in cancer biology. Semin Cancer Biol. 2008;18:275–80. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lokeshwar VB, Cerwinka WH, Isoyama T, Lokeshwar BL. HYAL1 hyaluronidase in prostate cancer: a tumor promoter and suppressor. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7782–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lokeshwar VB, Rubinowicz D, Schroeder GL, Forgacs E, Minna JD, Block NL, Nadji M, Lokeshwar BL. Stromal and epithelial expression of tumor markers hyaluronic acid and HYAL1 hyaluronidase in prostate cancer. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11922–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008432200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Miyamoto I, Nagase S. Age-related changes in the molecular weight of hyaluronic acid from rat skin. Jikken Dobutsu. 1984;33:481–5. doi: 10.1538/expanim1978.33.4_481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]