Abstract

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α inhibitors (TNFI) are a major class of biologic therapeutics, and include decoy receptor and monoclonal antibody (MAb) therapeutics that block TNFα action. TNFα is a pro-inflammatory cytokine in brain disease, such as stroke, brain or spinal cord injury, or Alzheimer disease. However, the biologic TNFIs cannot be developed for the brain, because these large molecules do not cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Brain penetrating forms of TNFα decoy receptors or anti-TNFα antibody therapeutics can be re-engineered as IgG fusion proteins with a BBB molecular Trojan horse, such as the mAb against the human insulin receptor (HIR). The HIRMAb undergoes receptor-mediated transport across the BBB via the endogenous insulin receptor, and carries into brain the fused biologic TNFI. A fusion protein of the HIRMAb and the type II TNF receptor (TNFR) extracellular domain, designated the HIRMAb-TNFR fusion protein, has been engineered and expressed in stably transfected Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells. The HIRMAb-TNFR fusion protein binds both the HIR and TNFα with low nM affinity. The HIRMAb cross reacts with the Rhesus monkey insulin receptor, and the HIRMAb-TNFR is rapidly, and selectively, taken up by primate brain at concentrations that inhibit TNFα. In addition, a fusion protein of the HIRMAb and a therapeutic single chain Fv (ScFv) antibody has been engineered and also expressed in stably transfected CHO cells. The BBB molecular Trojan horse platform technology allows for the engineering of brain-penetrating recombinant proteins as new biologic therapeutics for the human brain.

Key words: blood-brain barrier, insulin receptor, monoclonal antibody, tumor necrosis factor, decoy receptor

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α is an inflammatory cytokine that plays a pathologic role in acute and chronic disease of peripheral organs. TNFα action is suppressed by the administration of biologic TNFα-inhibitors (TNFI), which are one of two classes of recombinant proteins: decoy receptor drugs or monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapeutics. In the case of the decoy receptor drug, the extracellular domain (ECD) of the type II TNFα receptor (TNFR) is fused to the amino terminus of the human IgG1 Fc region.1 In the case of the mAb drugs, both chimeric and humanized mAb's directed against TNFα are FDA approved drugs.2

TNFα also plays a pathologic role in the central nervous system (CNS) including both acute disorders, such as stroke,3 brain trauma4,5 or spinal cord injury (SCI),6 as well as chronic diseases of the brain, such as Alzheimer disease (AD)7 or depression.8 However, the biologic TNFIs cannot be developed as drugs for the brain, because the biologic TNFIs do not cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The development of small molecule TNFIs is not likely to be successful. Even if a small molecule TNFI was developed, it would most likely not cross the BBB. Only lipid soluble small molecules with a molecular weight <400 Da cross the BBB in pharmacologically significant amounts, and 98% of all small molecules do not cross the BBB.9

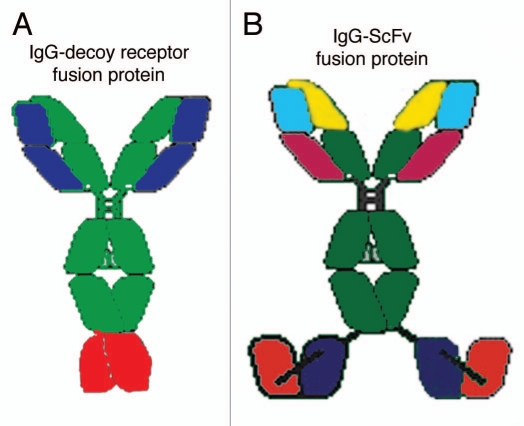

Diseases of the brain can be treated with biologic TNFIs if these large molecule drugs are re-engineered as fusion proteins with a BBB molecular Trojan horse.10 The latter is an endogenous peptide, or peptidomimetic mAb, which penetrates the BBB via receptor-mediated transport on an endogenous BBB receptor, such as the BBB insulin receptor or transferrin receptor (TfR). The most potent Trojan horse for the human brain is a genetically engineered MAb against the human insulin receptor (HIR).11 The engineering of the chimeric or humanized HIRMAb enables the subsequent genetic engineering of IgG fusion proteins, wherein the biologic drug, which is normally not transported across the BBB, is fused to the HIRMAb. Figure 1 illustrates the structure of two classes of HIRMAb fusion proteins that have been re-engineered to cross the human BBB. The TNFR ECD is fused to the carboxyl terminus of the heavy chain of the genetically engineered HIRMAb to form an IgG-decoy receptor fusion protein (Fig. 1A). Alternatively, a single chain Fv (ScFv) form of MAb therapeutic is fused to the carboxyl terminus of the genetically engineered HIRMAb to form an IgG-ScFv fusion protein (Fig. 1B). In either case, the IgG fusion protein is bi-functional.12,13 The HIRMAb part of the fusion protein triggers receptor-mediated transport across the human BBB. The TNFR ECD part of the fusion protein (Fig. 1A), or the ScFv part of the fusion protein (Fig. 1B), binds and neutralizes the target molecule within the brain behind the BBB. The IgG-decoy receptor fusion protein structure places the TNFR ECD in a dimeric configuration, which mimics the dimeric structure of the endogenous TNFR. The IgG-ScFv fusion protein structure places the ScFv in a dimeric configuration, which mimics the bivalency of an IgG molecule.

Figure 1.

(A) The HIRMAb-TNFR decoy receptor fusion protein is formed by fusion of the amino terminus of the TNFR ECD to the carboxyl terminus of the heavy chain of the engineered HIRMAb. (B) The HIRMAb-ScFv fusion protein is formed by fusion of the amino terminus of the ScFv to the carboxyl terminus of the heavy chain of the engineered HIRMAb. The HIRMAb-decoy receptor and HIRMAb-ScFv fusion proteins are bi-functional molecules. The top part of either fusion protein binds the HIR, at the BBB, to mediate transport into the brain, and the bottom part of either fusion protein binds TNFα, to suppress the inflammatory properties of the cytokine in brain behind the BBB.

IgG-Decoy Receptor Fusion Protein

The HIRMAb-TNFR is the first biologic TNFI ever engineered to penetrate the BBB of any species, much less the human BBB.12,14 This IgG-decoy receptor fusion protein is a bi-functional molecule and binds both the HIR on the BBB, to mediate brain penetration, and binding of TNFα within the brain behind the BBB. The structure of the HIRMAb-TNFR fusion protein departs from all prior structures of decoy receptor-IgG fusion proteins, where the decoy receptor is uniformly fused to the amino terminus of the human IgG Fc fragment.1 Fusion of the decoy receptor to the amino terminus of the human Fc serves to stabilize the decoy receptor in a dimeric configuration and to prolong the blood residence time of the decoy receptor pharmaceutical. However, the only receptor targeted by a decoy receptor:Fc fusion protein is the Fc receptor. IgG fusion proteins do not penetrate the BBB from blood via transport on a BBB Fc receptor. Although the neonatal Fc (FcRn) receptor is expressed at the BBB,15 the BBB Fc receptor only mediates the reverse transcytosis of IgG molecules from brain to blood, and does not mediate the influx of IgG molecules from blood to brain.16 In contrast to the design of the typical decoy receptor:Fc fusion protein, the HIRMAb-TNFR fusion protein incorporates the fusion of the amino terminus of the decoy receptor to the carboxyl terminus of the CH3 region of the heavy chain of the HIRMAb (Fig. 1A). This design places the TNFR ECD in a dimeric configuration, which mimics the native state of the receptor, which crystallizes as a dimer.17 Fusion of the decoy receptor to the amino terminus of the HIRMAb heavy chain would most likely impair binding of the antibody to the HIR, as demonstrated previously for a HIRMAb-enzyme fusion protein.18 Therefore, the design of the HIRMAb-TNFR fusion protein allows for retention of both functionalities of the fusion protein, i.e., high affinity binding to the HIR, for mediation of BBB transport, and high affinity binding to human TNFα, for suppression of the cytotoxic effects of this cytokine. Both HIR and TNFα binding properties of the fusion protein are high affinity characterized by KD values <1 nM for both targets.12

The HIRMAb-TNFR fusion protein is a hetero-tetrameric protein comprised of two heavy chains (HC) and two light chains (LC) (Fig. 1A). Given this complex structure, a eukaryotic host cell, the Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell, was chosen for the production of a stably transfected cell line.14 DG44 CHO cells were electroporated with a tandem vector, which encodes on a single DNA plasmid separate and tandem expression cassettes for the HC, the LC, and for the selection gene, dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR). DG44 cells do not express DHFR. Therefore, incorporation of the DHFR gene in the expression plasmid allows for selection of high producing CHO lines with methotrexate treatment. The CHO line is adapted to serum free medium (SFM), and high producing clones are isolated by two rounds of limited dilutional cloning. The HIRMAb-TNFR fusion protein is affinity purified from conditioned SFM by protein A chromatography.14

The initial HIRMAb-TNFR pharmacokinetics and brain uptake studies were performed in the adult Rhesus monkey.14 The HIRMAb cross reacts with the insulin receptor in Old World primates, such as the Rhesus monkey, but does not cross react with the insulin receptor of New World primates or with lower animals such as rodents. The HIRMAb-TNFR was radiolabeled with [3H]-N-succinimidyl propionate, in parallel with the radio-iodination of a Fc fusion protein of the TNFR ECD, designated TNFR:Fc. The [3H]-HIRMAb-TNFR and [125I]-TNFR:Fc fusion proteins were co-injected in the Rhesus monkey. The brain uptake of the HIRMAb-TNFR fusion protein, 3.0 ± 0.1% I.D/100 gram brain, is high compared to the brain uptake of the TNFR:Fc fusion protein, 0.23 ± 0.06% I.D/100 gram.14 This low level of brain uptake of the TNFR:Fc fusion protein is no greater than the brain uptake of a brain plasma volume marker, human IgG1, which indicates the TNFR:Fc fusion protein does not cross the BBB.14 Normalization of the organ uptake (%ID/gram) by the plasma area under the plasma concentration curve (AUC) allows for computation of the organ permeation-surface area (PS) product for brain and peripheral organs. This analysis demonstrated the brain targeting properties of the HIRMAb Trojan horse, as the ratio of the PS product for the HIRMAb-TNFR fusion protein, relative to the PS product for the TNFR:Fc fusion protein, is 30 for brain, but near unity for peripheral organs. These observations highlight the selective targeting of the brain by the HIRMAb Trojan horse.14

The pharmacokinetic and brain uptake data for the primate allow for initial dosing considerations of therapeutic interventions with the HIRMAb-TNFR fusion protein. The brain uptake, 3.0% ID/100 gram, at an injection dose of 0.2 mg/kg, produces a brain concentration of the HIRMAb-TNFR fusion protein of 1.1 pmol/gram fusion protein, which is equivalent to 2.2 pmol/gram, since there are 2 TNFR moieties per individual fusion protein (Fig. 1A). The concentration of immunoreactive TNFα in normal brain is undetectable, but increases to 0.4 pmol/gram in traumatic brain injury.5 Since the affinity of the HIRMAb-TNFR fusion protein for TNFα is high, a low dose of the HIRMAb-TNFR fusion protein of 0.2 mg/kg will sequester most of the cerebral TNFα in brain in traumatic brain injury. Higher doses of the fusion protein would sequester essentially 100% of the TNFα in brain in pathologic conditions. HIRMAb fusion protein, at doses as high as 20 mg/kg, has been administered intravenously to Rhesus monkeys chronically without side effects or changes in glycemic control in either plasma or cerebrospinal fluid.19

Decoy receptors, other than the TNFR, could also be re-engineered as HIRMAb fusion proteins for brain conditions, such as the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor for brain cancer,20 the TNF-like weak inducer of apoptosis receptor for stroke,21 or the lymphotoxin β receptor for multiple sclerosis.22

IgG-ScFv Fusion Protein

mAbs that bind and inactivate TNFα can also be developed as a biologic TNFI for the brain, providing the anti-TNFα MAb is re-engineered as a fusion protein with a BBB molecular Trojan horse such as the HIRMAb. This becomes a problem of engineering a single fusion protein comprised of the variable region of the heavy chain (VH) and the variable region of the light chain (VL) from two antibodies. In addition, the four genes encoding the 2 VH regions and the 2 VL regions must be spliced on to genes encoding the constant (C)-region of an IgG heavy chain and light chain. This was accomplished with the engineering of the HIRMAb-ScFv fusion protein shown in Figure 1B. In this case, a ScFv against the Abeta amyloid peptide of Alzheimer disease (AD) was fused to the carboxyl terminus of the heavy chain of the engineered HIRMAb, which incorporates the C-region of human IgG1 and the C-region of human kappa.13 The genes encoding the heavy chain and the light chain of the hetero-tetrameric HIRMAb-ScFv fusion protein were placed in separate expression cassettes on a single tandem vector (TV). Given the complex structure of the HIRMAb-ScFv fusion protein, which is glycosylated at the heavy chain C-region, CHO cells were chosen as the host cell. Following electroporation of the CHO cells with the TV encoding the HIRMAb-ScFv fusion protein, a high producing stably transfected line was cloned.13 The CHO-derived HIRMAb-ScFv fusion protein was homogeneous on both non-reducing and reducing SDS-PAGE. The HIRMAb-ScFv fusion protein was bi-functional and demonstrated high affinity binding to the HIR, with an ED50 of 1.9 ± 0.1 nM, and to the Abeta amyloid peptide, with an ED50 of 2.0 ± 0.8 nM.13 The HIRMAb-ScFv fusion protein was radiolabeled with the 125I-Bolton-Hunter reagent, and administered by intravenous (IV) injection into the adult Rhesus monkey for a plasma pharmacokinetics and brain uptake study. The systemic clearance of the HIRMAb-ScFv fusion protein was 1.7 ± 0.1 mL/min/kg and 1.32 ± 0.03 mL/min/kg, respectively, after injection of 0.2 and 1.0 mg/kg fusion protein. There was a linear relationship between the plasma AUC and dose, as the AUC was 118 ± 5 ug·min/mL and 759 ± 18 ug·min/mL, respectively, after the IV injection of 0.2 and 1.0 mg/kg HIRMAb-ScFv fusion protein.13

In conclusion, the BBB molecular Trojan horse platform technology enables the re-engineering of biologic TNFIs as brain penetrating neuropharmaceuticals. Tandem vectors have been engineered with allow for the production of high producing, stably transfected eukaryotic host cells lines. CHO lines have been propagated in serum free medium, and the IgG fusion proteins are purified by conventional protein A affinity chromatography. Without such re-engineering to enable brain penetration, the biologic TNFIs, or any other class of recombinant protein therapeutic, cannot be developed for diseases of the brain, owing to lack of transport of these large molecules across the BBB.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/biobugs/article/12105

References

- 1.Peppel K, Crawford D, Beutler B. A tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-IgG heavy chain chimeric protein as a bivalent antagonist of TNF activity. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1483–1489. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.6.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valesini G, Iannuccelli C, Marocchi E, Pascoli L, Scalzi V, Di Franco M. Biological and clinical effects of anti-TNFalpha treatment. Autoimmun Rev. 2007;7:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nawashiro H, Martin D, Hallenbeck JM. Neuroprotective effects of TNF binding protein in focal cerebral ischemia. Brain Res. 1997;778:265–271. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00981-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knoblach SM, Fan L, Faden AI. Early neuronal expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha after experimental brain injury contributes to neurological impairment. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;95:115–125. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shohami E, Novikov M, Bass R, Yamin A, Gallily R. Closed head injury triggers early production of TNFalpha and IL-6 by brain tissue. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1994;14:615–619. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1994.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marchand F, Tsantoulas C, Singh D, Grist J, Clark AK, Bradbury EJ, McMahon SB. Effects of Etanercept and Minocycline in a rat model of spinal cord injury. Eur J Pain. 2009;13:673–681. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tweedie D, Sambamurti K, Greig NH. TNFalpha inhibition as a treatment strategy for neurodegenerative disorders: new drug candidates and targets. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2007;4:378–385. doi: 10.2174/156720507781788873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Himmerich H, Fulda S, Linseisen J, Seiler H, Wolfram G, Himmerich S, et al. Depression, comorbidities and the TNFalpha system. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23:421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pardridge WM. The blood-brain barrier: bottleneck in brain drug development. NeuroRx. 2005;2:3–14. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pardridge WM. Re-engineering biopharmaceuticals for delivery to brain with molecular Trojan horses. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:1327–1338. doi: 10.1021/bc800148t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boado RJ, Zhang Y-F, Zhang Y, Pardridge WM. Humanization of anti-human insulin receptor antibody for drug targeting across the human blood-brain barrier. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2007;96:381–391. doi: 10.1002/bit.21120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hui EK-W, Boado RJ, Pardridge WM. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-IgG fusion protein for targeted drug delivery across the human blood-brain barrier. Mol Pharm. 2009;6:1536–1543. doi: 10.1021/mp900103n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boado RJ, Lu JZ, Hui EK-W, Pardridge WM. IgG-single chain Fv fusion protein therapeutic for Alzheimer's disease: expression in CHO cells and pharmacokinetics and brain uptake in the Rhesus monkey. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2010;105:627–635. doi: 10.1002/bit.22576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boado RJ, Hui EK-W, Lu JZ, Zhou Q-H, Pardridge WM. Selective targeting of a TNFR decoy receptor pharmaceutical to the primate brain as a receptor-specific IgG fusion protein. J Biotechnol. 2010;146:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlachetzki F, Zhu C, Pardridge WM. Expression of the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) at the blood-brain barrier. J Neurochem. 2002;81:203–206. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Pardridge WM. Mediated efflux of IgG molecules from brain to blood across the blood-brain barrier. J Neuroimmunol. 2001;114:168–172. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan KF, Siegel MR, Lenardo JM. Signaling by the TNF receptor superfamily and T cell homeostasis. Immunity. 2000;13:419–422. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boado RJ, Pardridge WM. Genetic engineering of IgG-glucuronidase fusion proteins. J Drug Targeting. 2010;18:205–211. doi: 10.3109/10611860903353362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boado RJ, Hui EK-W, Lu JZ, Pardridge WM. AGT-181: Expression in CHO cells and pharmacokinetics, safety, and plasma iduronidase enzyme activity in Rhesus monkeys. J Biotechnol. 2009;144:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holash J, Davis S, Papadopoulos N, Croll SD, Ho L, Russell M, et al. VEGF-Trap: a VEGF blocker with potent antitumor effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11393–11398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172398299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yepes M, Brown SA, Moore EG, Smith EP, Lawrence DA, Winkles JA. A soluble Fn14-Fc decoy receptor reduces infarct volume in a murine model of cerebral ischemia. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:511–520. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62273-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plant SR, Iocca HA, Wang Y, Thrash JC, O’Connor BP, Arnett HA, et al. Lymphotoxin beta receptor (Lt betaR): dual roles in demyelination and remyelination and successful therapeutic intervention using Lt betaR-Ig protein. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7429–7437. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1307-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]