Abstract

Bcl-2 homologues (such as Bcl-xL) promote survival in part through sequestration of “activator” BH3-only proteins (such as Puma), preventing them from directly activating Bax. It is thus assumed that inhibition of interactions between activators and Bcl-xL is a prerequisite for small molecules to antagonize Bcl-xL and induce cell death. The biological properties, described here of a terphenyl-based alpha-helical peptidomimetic inhibitor of Bcl-xL attest that displacement of Bax from Bcl-xL is also critical. Terphenyl 14 triggers Bax-dependent but Puma-independent cell death, disrupting Bax/Bcl-xL interactions without affecting Puma/Bcl-xL interactions. In cell-free assays, binding of inactive Bax to Bcl-xL, followed by its displacement from Bcl-xL by terphenyl 14, produces mitochondrially permeabilizing Bax molecules. Moreover, the peptidomimetic kills yeast cells that express Bax and Bcl-xL, and it uses Bax-binding Bcl-xL to induce mammalian cell death. Likewise, ectopic expression of Bax in yeast and mammalian cells enhances sensitivity to another Bcl-xL inhibitor, ABT-737, when Bcl-xL is present. Thus, the interaction of Bcl-xL with Bax paradoxically primes Bax at the same time it keeps Bax activity in check, and displacement of Bax from Bcl-xL triggers an apoptotic signal by itself. This mechanism might contribute to the clinical efficiency of Bcl-xL inhibitors.

The Bcl-2 family of interacting proteins plays a major role in regulating apoptosis. Antiapoptotic Bcl-2 homologs (e.g., Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Mcl-1) control the survival and progression of tumors and their sensitivity to conventional therapy (34). They preserve mitochondrial integrity by opposing the activity of the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members Bax and Bak, which display sequence conservation throughout three Bcl-2 homology (BH) domains (BH1 to -3) and that of their upstream effectors, the BH3-only proteins (e.g., Bid and Bad) (14, 41). The mechanisms by which Bcl-xL counteracts the toxicity of Bax are of particular importance in human cancer cells, because in these cells the expression level of Bcl-xL strongly correlates with resistance to most chemotherapeutics (2), and Bax is crucial for the apoptotic response to diverse stimuli, including that to BH3-only proteins (45) (13) (4).

There are certainties and unknowns about how Bcl-xL prevents Bax activation and/or activity. It is commonly agreed that the antiapoptotic function of Bcl-2 homologs relies on the ability of a hydrophobic grove, formed at their surface by the BH1, -2, and -3 domains, to engage the α-helical BH3 domains of proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members (32). It is also widely accepted that occupation of this BH3-binding site by small-molecule ligands, the so-called BH3 mimetics, will inhibit this antiapoptotic function. In contrast, the molecular mechanism(s) through which the BH3-binding activity of Bcl-2 homologs, such as Bcl-xL, exerts control over Bax and how exactly BH3 mimetics might promote Bax-dependent apoptosis remain unclear.

These questions are particularly apposite because Bax is synthesized in a constitutively inactive form, which is cytosolic and/or peripherally associated with mitochondria and thus must be activated to a proapoptotic form to exert cytotoxicity. Conformational changes leading to the exposure of key functional domains within the molecule are required for this protein to be activated and for it to insert into mitochondrial membranes and then kill cells (reviewed in references 21 and 44). How Bcl-2 homologs such as Bcl-xL, as BH3-binding proteins, interfere with this process of Bax “activation” requires elucidation.

A subgroup of BH3-only proteins, such as Bim or Puma, exerts direct Bax-activating properties through their eponymous BH3 domain (reviewed in reference 22). It is thus thought that the BH3-binding activity of Bcl-2 homologs promotes survival in great part by sequestering Bax “activator” BH3 molecules. Consistent with this, the ability of diverse Bcl-2 homologs to maintain cell survival has been linked to their physical engagement of Bim or Puma, and the induction of cell death by the high-affinity BH3-mimetic inhibitor of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL ABT-737 was shown to coincide with an inhibition of these interactions (8, 9, 11). The demonstration that there is a functional hierarchy among BH3-only proteins, with “BH3 activators” (Bim and Puma) acting downstream of “BH3 sensitizers” (i.e., those “BH3-only” proteins, such as Bad, that bind only to prosurvival members of the Bcl-2 family and do not activate Bax directly) (16, 23), is also in agreement with the notion that binding by Bcl-2 homologs (such as Bcl-xL) of BH3 activators (such as Puma) is a key event that critically dictates cell fate. The aforementioned hierarchy is not absolute, however: if “BH3 activators” are required for full-blown apoptosis induction by “BH3 sensitizers,“ the latter can nevertheless initiate apoptosis in the absence of the former (42). To account for these observations, it has been proposed that a direct interaction between Bcl-2 homologs and Bax is also involved in determining cell survival (1). This raises the question of how critical this specific interaction might be for the regulation of apoptosis. In particular, understanding whether displacement of Bax from survival Bcl-2 homologs is sufficient to promote cell death by itself and understanding how Bax might be “activated” under these conditions without the recruitment of “BH3 activators” are required, particularly for an understanding of the determinants of BH3 mimetic toxicity.

The work presented here addresses these issues by documenting the biological properties of a previously described Bcl-xL antagonist. We used a cell-permeant terphenyl-based peptidomimetic rationally designed to mimic an α-helical BH3 domain based on the crystal and solution structures of the BH3Bak/Bcl-xL complex (18, 43). We show that treatment of cells with this compound inhibits Bax/Bcl-xL interactions but fails to interfere with Puma/Bcl-xL interactions. This compound triggers Puma-independent, Bax-dependent cell death that relies on Bax displacement from Bcl-xL, as evidenced by the following observations: (i) in cell-free assays, initially inert Bax gains proapoptotic activity after its interaction with Bcl-xL and its subsequent release from Bcl-xL by the compound; (ii) yeast cells that express Bax and Bcl-xL but not either of these proteins alone are sensitive to the deleterious effects of the compound; and (iii) induction of mammalian cell death by the compound is a Bcl-xL-dependent process that can be rescued by wild-type Bcl-xL but not by a mutant of Bcl-xL that does not interact with Bax. This implies that the interaction of Bax with Bcl-xL, followed by its release from this survival protein upon occupancy of its BH3-binding site, constitutes a two-step (“trap and release”) process that can produce “activated” Bax molecules and initiate cell death by itself. Consistent with this, ABT-737 also can promote Bcl-xL-dependent Bax activation in some instances. Direct and sustained interactions between Bax and Bcl-xL are thus critical for cell survival, even in the absence of BH3 activators.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibodies.

The following antibodies were used: anti-Bcl-xL antibody from Epitomics (1018-1) for immunoprecipitation and from Transduction Laboratories (610747) for Western blotting, anti-Puma antibody from Calbiochem (Ab-1) for Western blotting, anti-Bax 2D2 (for Western blotting and immunoprecipitation) and 6A7 (for immunoprecipitation) from Beckman Coulter (731730 and 731731, respectively), anti-cytochrome c antibody from R&D Systems (MAB897), anti-active caspase 3 antibody from PharMingen (559565); anti-F1F0-ATPase subunit α from Molecular Probes (A-21350); antiactin from Chemicon (MAB1501R) for immunocytochemistry. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents were obtained from Bio-Rad (France) and Santa Cruz. Fluorescent Alexa 488- and Alexa 568-conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from Molecular Probes. Terphenyl 14, synthesized as described in reference 18, was systematically prepared freshly in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a 100 mM concentration prior to dilution to appropriate concentrations in the indicated buffers or culture media. ABT-737 was synthesized as previously described (30). Unless indicated, all other reagents used in this study were obtained from Sigma.

Peptides and recombinant proteins.

Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled or nonfluorescent high-pressure liquid chromatography-purified Bid-BH3 (EDIIRNIARHLAQVGDSMDR), Bad-BH3 (NLWAAQRYGRELRRMSDEFVDSFKK), Puma-BH3 (RGEEEQWAREIGAQLRRMADDL) Bax-BH3 (KKLSECLKRIGDELDS), and Bax-BH3 L63A (KKLSECAKRIGDELDS) peptides were obtained from Sigma-Genosys (Cambridge, United Kingdom). The preparation of histidine-tagged (for cell-free pulldown assays) or glutathione S-transferase (GST)-fused (for fluorescence polarization and microinjection assays) recombinant Bcl-xL (wild type or G138A lacking 24 amino acids at the COOH terminus) have been described in references 10 and 25, respectively.

Cell-free assays.

Fluorescence polarization (FP) assays were performed essentially as described in reference 25. Fluorescent peptides (Bid-BH3, Bad-BH3, or Puma-BH3; 15 nM) and GST-Bcl-xL (wild type or G138A; 0.1 μM) were mixed in binding buffer (20 mM Na2HPO4 [pH 7.4], 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% pluronic acid) with titrations of terphenyl 14 or of nonfluorescent peptides. Fluorescence polarization was then measured using Fusion-Packard equipment.

In vitro synthesis and quantification of 35S-Met (Amersham, France)-labeled Bax (35S-Bax) from cDNAs using the TNT coupled transcription/translation system (Promega, France) were performed as described previously (39). Cell-free protein binding experiments between 35S-Bax and His-tagged Bcl-xL (wild type or G138A when indicated) were performed essentially as described in reference 28. Briefly, 35S-Bax (4 fmol) was incubated with His-tagged proteins (8 fmol) immobilized on nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) resin in 50 μl binding buffer (142 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 0.5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 1 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and a mixture of other protease inhibitors) at 30°C for 2 h. The resulting mixture was then incubated for an additional hour at 30°C in the absence or presence of the indicated concentration of terphenyl 14. Protein complexes were then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C and washed three times in binding buffer. The resulting pellet, and the supernatant from the first centrifugation at 13,000 × g, were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by scanning with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, France) followed by quantification using the IPLab gel program (Signal Analytics, Vienna, VA). Where indicated, supernatants from the first centrifugation were added to mitochondria (2.5 mg proteins/ml) isolated from rat liver, as described in reference 39, at 37°C for 1 h in 40 μl standard import buffer (250 mM sucrose, 80 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM malic acid, 8 mM succinic acid, 1 mM ATP-Mg2+, 20 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid [MOPS], pH 7.5, and reticulocyte lysate, 10% [vol/vol]), followed by centrifugation of mitochondria. 35S-Bax (4 fmol) incubated with 10 μM terphenyl 14 for 1 h at 30°C in binding buffer in the absence of His-tagged Bcl-xL was also incubated with isolated rat liver mitochondria under identical conditions. The amount of cytochrome c present in the mitochondrial supernatant following any given treatment was analyzed by Western blotting.

For cell-free immunoprecipitation assays of 35S-Bax, radiolabeled Bax/His-tagged Bcl-xL complexes were prepared, treated or not with terphenyl 14 (10 μM), ABT-737 (1 μM), or BH3 peptides (1 μM), and isolated by centrifugation as described above. The resulting supernatants were used for immunoprecipitation assays using the 6A7 or 2D2 anti-Bax antibody (4 μg), performed with the Catch and Release V2.0 reversible immunoprecipitation system (Upstate) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The same protocol was used for immunoprecipitation of 0.8 fmol of untreated 35S-Bax, of 35S-Bax that had been treated with 10 μM terphenyl 14 in the absence of Bcl-xL, or of 35S-Bax that had been incubated for 30 min at 37°C at pH 4 prior to neutralization at pH 7.4, as described in reference 5. Immunoprecipitated radiolabeled proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography as described above.

Isolation of mitochondria from HeLa cells (cultured as described below) was performed by subcellular fractionation. The indicated HeLa cells were scraped using a Teflon scraper and centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The cell pellets were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in volume-per-volume cell extraction buffer (CEB) (250 mM sucrose, 50 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10 μM cytochalasin B, 1 mM EGTA, and 1 tablet protease inhibitor). Cells were allowed to swell for 30 min on ice prior to their homogenization with 50 strokes in an ice-cold 2-ml glass Dounce homogenizer. Unbroken cells and nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation at 750 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Mitochondria were collected from the resulting supernatants by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Mitochondrial pellets were resuspended in standard mitochondrial buffer (see above) prior to determination of the protein concentration and incubation with the indicated concentration of terphenyl 14. The amount of cytochrome c present in the mitochondrial supernatant and in the mitochondrial fraction following any given treatment was analyzed by Western blotting.

Mammalian cell culture.

Human colorectal cancer cells lines derived from HCT116 (p21−/−, p21−/− Puma−/−, or p21−/− Bax−/−) were kindly provided by B. Vogelstein. These cells were grown in complete McCoy medium as previously described (45). HeLa cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and 2 mM glutamine. Simian virus 40 (SV40) large-T-antigen-immortalized wild-type and Bcl-xL−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), kindly provided by D. Huang, were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and 2 mM glutamine.

Mammalian cell assays.

Recombinant lentivirus (shScr and shBcl-xL, targeting nucleotides 58 to 76 of human Bcl-xL) were engineered, produced, and titrated as previously described (11). A multiplicity of infection of 5 was used, and further experiments were performed 3 days after infection.

Transient transfection of lentivirus-treated HeLa (or HCT116 p21−/−Puma−/−) with plasmids expressing short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-resistant Bcl-xL cDNAs was performed using the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's instructions. shRNA-resistant cDNAs were obtained by introducing four silent point mutations to the region that is targeted by the shRNA, at nucleotides 63, 67, 68, and 75 (uppercase letters), replacing the original sequence, aaaggAtacAGctggagTc, with aaaggGtacTCctggagCc. Cells at 80% confluence in 1 well of a 12-well plate were treated overnight with Lipofectamine mixed with 1 μg of either pCMV-shresBcl-xL, pCMV-shresBcL-xL G138A, pCMV-shresBcL-xL L90A, pCMV-shresBcL-xL ΔTM (lacking the 23 amino acids at the C terminus), or the empty pCMV vector in Opti-MEM I reduced serum medium. Transfected cells were washed and left for an additional 24 h in complete medium prior to the indicated treatment, Western blot analysis and cell death assays. Transient transfection of lentivirus-treated HeLa cells with plasmid expressing Bax cDNA was performed essentially as described above, using cells grown at 80% confluence in 1 well of a 6-well plate transfected with 0.2 μg of pCMV-Bax.

Stable knockdown of Bax and Bcl-xL in HeLa cells was performed using pSilencer2.1 plasmids that contain short hairpin RNA targeted to oligonucleotides 392 to 400 of human BAX or to oligonucleotides 578 to 598 of human BCL-X, introduced into the pSilencer2.1-Hygro plasmid as previously described (26). HeLa cells expressing the corresponding plasmids or the negative-control pSilencer2.1-Hygro-SCR plasmid were obtained by electroporation followed by selection in hygromycin (100 μg/ml). Functional assays were performed in the absence of hygromycin using the bulk of selected cells to avoid clonal bias.

HeLa and HCTT116 cells manipulated as described above were treated for the appropriate time with the needed concentrations of terphenyl 14, ABT-737, or DMSO carrier alone. DEVDase activity in cellular lysates was measured as described in reference 6. Cell death was also evaluated using a trypan blue staining procedure. For immunocytochemical analysis, cells grown on glass coverslips were fixed and stained as previously described (6). Coimmunoprecipitation assays were performed after the indicated treatments using 4 μg of the indicated antibody and 500 μg of protein lysates in CHAPS buffer (HEPES [10 mM], NaCl [150 mM], and CHAPS [1%] [pH 7.4]) with the Catch and Release V2.0 reversible immunoprecipitation system (Upstate), according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Short-term knockdown of Bcl-xL or Mcl-1 in HeLa cells was performed by transient transfection of validated siBcl-xL or siMcl-1 nucleotides and of control small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) (Ambion) using the HiPerfect transfection reagent (Qiagen 301705) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For functional assays, 5 × 104 cells were seeded in 9-mm dishes 24 h prior to transfection. Nucleotides (0.6 μl, 20 μM) were incubated with the HiPerfect reagent (6 μl) for 10 min at room temperature in 100 μl of serum-free RPMI medium and then added to the cell complete medium to a final nucleotide concentration of 5 nM. Cells were incubated with nucleotides for 48 h (for siBcl-xL) or 24 h (for siMcl-1) prior to subsequent treatment with terphenyl 14 or ABT-737. For Western blot experiments, the same procedure was employed using 2 × 105 cells seeded on 35-mm dishes 24 h before transfection with the corresponding amount of siRNA nucleotides.

Transient transfection of Bcl-x knockout MEFs with plasmids encoding Bcl-xL wild type or G138A together with a plasmid encoding the red fluorescent protein DsRed was performed using the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent. Briefly, 105 cells were seeded in 1 well of a 24-well plate prior to overnight incubation with Lipofectamine mixed with 0.2 μg of pDs-Red and 0.8 μg of either pCMV-Bcl-xL, pCMV-BcL-xLG138A, or the empty pCMV vector in Opti-MEM I reduced serum medium. Transfected cells were then washed and left for an additional 24 h in complete DMEM. Immunocytochemical and Western blotting indicated that expression of ectopic Bcl-xL and that of Bcl-xL G138 in transfected Bcl-x−/− MEFs were comparable (data not shown). Morphological analysis of fluorescent (i.e., DsRed-positive) cells was performed using a Zeiss Axiovert 200-M inverted fluorescence microscope.

Yeast assays.

Yeast expressing galactose-inducible wild-type untagged Bax, Bcl-xL, or both were obtained by transforming the wild-type haploid strain W303-1B (mata ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3) with the vectors pYES3/Bax and pDP83A/Bcl-xL, which express the corresponding cDNA under the control of the GAL1/10 promoter, and TRP1 and URA3 as yeast selection markers, respectively (3).

Cells were grown aerobically at 28°C in a semisynthetic medium containing 0.17% yeast nitrogen base (Difco), 0.1% potassium phosphate, 0.5% ammonium sulfate, 0.2% Drop-Mix, 0.01% of auxotrophic requirements, and 2% dl-lactate as a nonfermentable carbon source (pH 5.5). Cultures were diluted to a cell density of 1 × 106 cells/ml in the same medium supplemented with 1% galactose to induce the expression of the proteins for 8 h.

For immunoprecipitation experiments, cells were diluted, after protein induction, to a cell density of 1 × 106 cells/ml in the same medium (i.e., with galactose) where drugs (100 μM terphenyl 14) or mock (DMSO plus 0.02% Tween 20) were added. Six hours later, cells (5 ml culture) were washed twice with 10 mM Tris-maleate (pH 6.7) containing 0.4 M mannitol, 2 mM EGTA, antiproteases (Complete; Roche), and antiphosphatases (Phostop; Roche) and broken with glass beads (3 min). After unbroken cells were sedimented (900 × g, 10 min), the supernatant was added with 10× immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (IP50; Sigma) and incubated at 4°C for 40 min. Anti-Bax antibody (mouse monoclonal 2D2; Sigma) was added (2 μg/ml), and immunoprecipitation was done overnight at 4°C. Protein G Sepharose beads were added and incubated for 6 h. Beads were washed 6 times and incubated with 25 μl Laemmli buffer for 5 min at 90°C. Samples were separated on SDS-PAGE, transferred on polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF), and immunoblotted with anti-Bax (N20; Santa-Cruz) or anti-Bcl-x (BD Transduction Laboratories) rabbit polyclonal antibodies. Immunoblots were revealed with the ECL+ system (GE Healthcare). Nonsaturated films were scanned and quantified using the ImageJ software program.

For cell viability assays, cells were diluted to a cell density of 1 × 106 cells/ml after protein induction and incubated in the presence (or not) of compounds for an additional 12 h in the same medium, after which cell density was assessed.

RESULTS

BH3-mimetic terphenyl 14 triggers Bax-dependent cell death independently of the BH3 activator Puma.

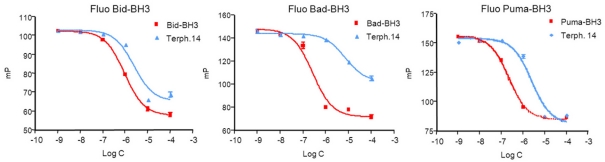

As a tool to study how inhibition of the BH3-binding site of Bcl-xL can trigger Bax activation, we used a synthetic small molecule described by Kutzki and colleagues, terphenyl 14, which mimics an α-helical BH3 domain (18). Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy has shown that terphenyl 14 targets the helical, BH3 binding area on the surface of Bcl-xL (43). Fluorescence polarization assays using recombinant Bcl-xL fused to GST, as previously described (25), confirmed that terphenyl 14 inhibited the binding of diverse BH3 peptides (derived from Bid, Bad, and Puma) to Bcl-xL in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1 and Table 1), in agreement with the notion that it is a bona fide BH3 mimetic.

FIG. 1.

Inhibition of Bcl-xL binding to BH3 peptides by terphenyl 14 (Terph. 14). Fluorescence polarization-based competitive binding assays using fluorescein-labeled Bid-BH3, Bad-BH3, or Puma-BH3 (15 nM) in complex with Bcl-xL (as a GST fusion protein; 100 nM) are shown for terphenyl 14 and respective nonfluorescent peptides at the indicated concentrations (C). Data are means (± SEM) of results from 3 independent experiments. mP, milli-polarization level.

TABLE 1.

Effect of terphenyl 14 on BH3 binding by Bcl-xLa

| Peptide | IC50 (μM) for: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BcI-xL/Fluo Bid-BH3 | BcI-xL/Fluo Bad-BH3 | BcI-xL(G138A)/Fluo Bad-BH3 | BcI-xL/Fluo Puma-BH3 | |

| Terph. 14 | 1.74 ± 0.69 | 6.36 ± 2.45 | 6.94 ± 1.05 | 3.2 ± 0.39 |

| Bid-BH3 | 0.66 ± 0.20 | ND | ND | ND |

| Bad-BH3 | ND | 0.27 ± 0.02 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | ND |

| Puma-BH3 | ND | ND | ND | 0.25 ± 0.01 |

Interaction of fluorescent (Fluo) peptides with Bcl-xL (wild type or G138A) in the presence of terphenyl 14 (Terph. 14) or unlabeled peptides was analyzed by fluorescence polarization. IC50, the concentration required to displace 50% of the fluorescent BH3 peptides (15 nM) bound to 100 nM GST-fused Bcl-xL. Bcl-xL(G138A) does not bind Bid-BH3. Data are means (± SEM) of results from 3 independent experiments. ND, not determined.

To investigate the biological effects of terphenyl 14, we treated the human colorectal cancer cell line HCT116 p21−/− with this compound. These cells rely on the expression of Bcl-xL to maintain their survival in culture (11). This is due in part to the constitutive expression of the BH3 activator Puma, which, like Bax, is bound to Bcl-xL in these cells. As shown in Fig. 2A, treatment of HCT116 p21−/− cells with terphenyl 14 (50 to 100 μM) induced cell death. This process was Bax dependent as judged by the resistance of the corresponding HCT116 p21−/− Bax−/− cells to the same treatments. Surprisingly, HCT116 p21−/− Puma−/− cells were as sensitive as parental cells to terphenyl 14. We inferred that the lack of effect of Puma expression on the response of HCT116 p21−/− cells to terphenyl 14 relied on the inability of this compound to liberate a sufficient amount of Puma protein from survival proteins. Consistent with this, we found that treatment of cells with terphenyl 14 had no impact on Puma/Bcl-xL interactions, as evaluated in coimmunoprecipitation assays (Fig. 2B). In contrast, terphenyl 14 significantly displaced endogenous Bax from Bcl-xL, in agreement with a previous report (43). Of note, our coimmunoprecipitation assays were performed with cell lysates obtained using CHAPS, a detergent that does not induce overt modifications of Bax conformation by itself (15).

FIG. 2.

Role of Puma and Bax in cell death induction of HCT116 p21−/− cells by terphenyl 14. (A) Effect of terphenyl 14 on viability. Parental, Bax knockout, or Puma knockout HCT116 p21−/− cells were treated with the indicated concentration of terphenyl 14 for 24 h prior to measurement of cell viability. Data are means (± SEM) of results from 3 independent experiments. (B) Effect of terphenyl 14 on Bax/Bcl-xL and Puma/Bcl-xL interactions. HCT116 p21−/− cells were treated with terphenyl 14 (100 μM) (Ter. 14) or not treated (Unt.) for 24 h, and the resulting cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (I.P.) with an anti-Bcl-xL antibody. Bcl-xL, Bax, and Puma present in total extracts and immunoprecipitated fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting (W.B.). The amount of Bax or Puma that coimmunoprecipitated with Bcl-xL under each condition was evaluated by densitometric analysis and normalized to the amount of protein that coimmunoprecipitated with Bcl-xL in untreated cells. Data are means (± SE) of results from three independent experiments. P values were assessed using a Student t test.

Terphenyl 14 cooperates with Bcl-xL to promote Bax activation in cell-free assays.

It follows from the above experiments that terphenyl 14 induction of Bax- dependent cell death occurs without the recruitment of the BH3 activator Puma, which terphenyl 14 cannot displace from Bcl-xL, but under conditions where Bax is displaced from Bcl-xL. We thus investigated whether displacement of Bax from Bcl-xL by terphenyl 14 can directly promote cell death.

We first investigated whether terphenyl 14 was able to promote cell-free activation of Bax in the presence of its target Bcl-xL but in the absence of direct BH3 activators using published methods (4, 28). In these assays, in vitro-translated radiolabeled (IVTR) Bax molecules were used. These molecules are essentially inert for isolated mitochondria. These “inactive” IVTR Bax molecules interact with Bcl-xL significantly, although less efficiently than IVTR Bax molecules that have been “activated” after coincubation with Bid (28). The specificity of these interactions, which were evaluated in cell-free pulldown assays using recombinant His-tagged Bcl-xL, was strongly underscored by the fact that they were abrogated by the G138A mutation within Bcl-xL (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Terphenyl 14 cooperates with Bcl-xL to promote cell-free Bax activation. (A and B) Effect of terphenyl 14 on cell-free binding of Bax to Bcl-xL. (A) In vitro-translated radiolabeled Bax (4 fmol) was incubated with the indicated His-tagged Bcl-xL recombinant proteins (8 fmol). His-bound protein complexes were then centrifuged, and the presence of free 35S-Bax in the resulting supernatant (F.) or 35S-Bax bound to Bcl-xL following three additional washes (B.) was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography with a PhosphorImager. Autoradiograms representative of three independent experiments are shown. Input, 4 fmol of untreated 35S-Bax was loaded for illustrative purposes. The average quantity of Bax bound to His complexes (mean ± SE of results from three independent experiments) was evaluated and is expressed as a percentage of the initial amount of 35S-Bax (n.a., nonapplicable). wt, wild type. (B) His-Bcl-xL wild type/35S-Bax complexes were left untreated or treated with 10 μM terphenyl 14. The presence in the initial complexes (lane 1) and in the supernatant resulting either from a mock treatment (lane 2) or from terphenyl treatment (lane 3) of His-tagged Bcl-xL and of 35S-Bax was analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-His antibody (34660 from Qiagen) and by autoradiography, respectively. Data representative of three independent experiments are shown. The average quantity of Bax displaced from His complexes by 10 μM terphenyl 14 (mean ± SE of results from three independent experiments), expressed as a percentage of 35S-Bax present in the initial His complexes, is indicated. (C) Effect of terphenyl 14 on Bax-induced mitochondrial permeabilization in the presence of Bcl-xL. Left, 35S-Bax (4 fmol) was incubated with His tagged-Bcl-xL (8 fmol) prior to the addition of terphenyl 14. His-bound protein complexes were then centrifuged, and the presence of 35S-Bax in the resulting supernatant (free 35S-Bax) and in the pellet following three additional washes (Bcl-xL-bound 35S-Bax) was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography with a PhosphorImager. Data representative of three independent experiments are shown. Right, 35S-Bax (4 fmol) bound to His-tagged Bcl-xL was treated with terphenyl 14 prior to its incubation with rat liver mitochondria (100 μg) for 1 h at 37°C. The presence of cytochrome c in the supernatant following centrifugation of mitochondria was analyzed by Western blotting. Where indicated, terphenyl 14 (10 μM) was directly added to 4 fmol 35S-Bax in the absence of Bcl-xL prior to incubation with isolated mitochondria. Western blots representative of three independent experiments are shown. (D) Effect of terphenyl 14 on Bax conformation in the presence of Bcl-xL. 35S-Bax was subjected to the indicated treatment prior to immunoprecipitation with the 2D2 or 6A7 anti-Bax antibody. 1, untreated 35S-Bax; 2, 35S-Bax treated with 10 μM terphenyl 14 in the absence of Bcl-xL; 3, 35S-Bax preincubated at pH 4; 4, 35S-Bax preincubated with His-tagged Bcl-xL and released from Bcl-xL by 10 μM terphenyl 14. Data representative of three independent experiments are shown.

In cell-free pulldown assays, terphenyl 14 disrupted the interaction of IVTR Bax with recombinant His-tagged Bcl-xL (Fig. 3B) in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3C). This confirms that this compound exerts a direct inhibitory effect on Bax-Bcl-xL interactions. Those Bax molecules displaced from Bcl-xL by terphenyl 14 exhibited mitochondrial permeabilizing properties, as judged by their ability to induce cytochrome c release when added to rat liver mitochondria (Fig. 3C), which are not permeabilized by BH3 peptides unless exogenous Bax is added (4). Of note, Bcl-xL combined with terphenyl 14 (10 μM) was unable to induce cytochrome c release in the absence of Bax (data not shown), indicating that terphenyl 14, as previously reported for BH3 peptides, does not convert Bcl-xL into a protein with innate permeabilizing properties (19, 28).

In the above assays, the initial amount of IVTR Bax, even in the presence of 10 μM terphenyl 14, was insufficient to induce cytochrome c release unless it was prebound to Bcl-xL (Fig. 3C). This implies an active contribution of Bcl-xL in the activation of Bax mitochondrial permeabilizing activity by terphenyl 14. To further test this and to determine whether this process is accompanied by a change in Bax conformation, we used a previously reported cell-free immunoprecipitation assay, devoid of isolated mitochondria, using the conformation-specific 6A7 monoclonal anti-Bax antibody (15, 28). Binding of this antibody to Bax indicates a change in Bax conformation that, notably, can be induced by incubation of IVTR Bax with activator BH3 peptides (such as Bid-BH3) that also enhance Bax mitochondrial activity (4). In contrast, neither native IVTR Bax nor Bcl-xL-bound IVTR Bax immunoreacted with this antibody (4). As shown in Fig. 3D, the 6A7 antibody immunoreacted with IVTR Bax after acidification (as a positive control of Bax activation [5]) or once IVTR Bax had been displaced from Bcl-xL by 10 μM terphenyl 14 but not with IVTR Bax to which terphenyl 14 was added in the absence of Bcl-xL. In contrast, the 2D2 antibody, which recognizes Bax regardless of its conformation, immunoprecipitated IVTR Bax under all conditions tested (Fig. 3D). Analysis of 2D2-immunoprecipitated Bax under nondenaturing conditions showed, moreover, that IVTR Bax that was displaced from Bcl-xL by terphenyl 14 could form homodimers in solution, another reported feature of “activated” Bax molecules (data not shown). Thus, a two-step process wherein initially inactive Bax binds to Bcl-xL and is then released from Bcl-xL by the terphenyl 14 BH3 mimetic produces activated Bax molecules in cell-free assays.

Yeast cells expressing Bax and Bcl-xL are sensitive to terphenyl 14.

To confirm that the “trap and release” mechanism described above is sufficient to initiate cell death, we used yeast cells. Yeast express no recognized Bcl-2 family proteins. They tolerate the expression of full-length untagged wild-type human Bax but undergo cell death when they express Bax variants that carry mutations that critically affect the protein conformation or when they express wild-type Bax together with BH3 activators (3, 11, 33, 40). We thus analyzed whether the expression of Bax and Bcl-xL in this context is sufficient to install some sensitivity to terphenyl 14, employing yeast strains that express galactose-inducible Bax, Bcl-xL, or both. Untagged wild-type Bax was used since its induction in our system had no detectable impact on yeast viability by itself (33).

The coexpression of Bax and of Bcl-xL lead to substantial interaction between these proteins, as judged by coimmunoprecipitation experiments (Fig. 4A). Treatment of yeast cells coexpressing Bax and Bcl-xL with terphenyl 14 (100 μM) inhibited Bax/Bcl-xL interactions (assayed in coimmunoprecipitation experiments) (Fig. 4A and B). A significant decrease in the viability of yeast expressing Bax and Bcl-xL but not of these expressing either one alone was observed under these conditions (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

Expression of Bax and Bcl-xL renders yeast cells sensitive to terphenyl 14. (A and B) Effect of terphenyl 14 treatment on Bax/Bcl-xL interactions in yeast. The indicated strains were grown, and Bax and/or Bcl-xL expression was induced by galactose prior to treatment with terphenyl 14 (100 μM) or mock treatment (DMSO plus 0.02% Tween 20) for an additional 6 h, followed by immunoprecipitation with anti-Bax antibodies and Western blotting (WB) of the resulting immunoprecipitates (A). The amounts of Bcl-xL and of Bax that were immunoprecipitated by anti-Bax antibodies were evaluated by densitometric analysis. The Bcl-xL/Bax ratio was normalized to 1 for mock conditions for each experiment. Data are the means (± SEM) of results from three independent experiments (B). (C) Effect of terphenyl 14 on the viability of yeast cells expressing Bax, Bcl-xL, or both. The indicated strains were grown in the presence of galactose, and cell density was measured in each of the indicated yeast strains 12 h after treatment with terphenyl 14 (100 μM). It is expressed as a percentage of the density measured in the corresponding mock-treated samples. Data are means (± SEM) of results from 8 independent experiments. P values (*, P < 0.005) were assessed using a Student t test.

Terphenyl 14 requires Bcl-xL to trigger Bax-mediated mitochondrial permeabilization and cell death.

We then analyzed whether the cooperation between Bcl-xL and terphenyl 14 to liberate activated Bax, analyzed in the above assays, is also triggered in mammalian cells and if Bcl-xL contributes to Bax activation induced by terphenyl 14. We previously published that HCT116 p21−/− cells undergo cell death upon Bcl-xL depletion by RNA interference unless Puma expression is diminished (11). We thus used HCT116 p21−/− Puma−/− cells and downregulated Bcl-xL expression with a previously published approach using a recombinant lentivirus that expresses green fluorescent protein (GFP) together with a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting Bcl-xL (shBcl-xL) (11). Bcl-xL-depleted cells or cells infected with a control lentivirus were treated with terphenyl 14. As shown in Fig. 5A, the downregulation of Bcl-xL reduced cell death induced by terphenyl 14.

FIG. 5.

Bcl-xL is involved in the induction of mitochondrial Bax activity by terphenyl 14. (A) Bcl-xL contributes to cell death induction by terphenyl 14 in HCT116 p21−/− Puma−/− cells. HCT116 p21−/− Puma−/− cells were infected with a control recombinant lentivirus (shScr) or with a recombinant lentivirus expressing a short hairpin targeting Bcl-xL (shBcl-xL) before their treatment with terphenyl 14 (100 μM). Twenty-four hours later, cell death was assessed as described in the legend for Fig. 2. Data are means (± SEM) of results from 3 independent experiments. (B) Bcl-xL is required for Bax-dependent induction of cytochrome c (cyt c) release and caspase 3 (casp3) activation by terphenyl 14. Immunostaining of cytochrome c and active caspase 3 in HeLa cells expressing a control plasmid (SCR), pSilencer Bax (shBax), or pSilencer BCL-X (shBcl-x) and treated with or without terphenyl 14 (100 μM) for 18 h was performed. The percentages of cells exhibiting mitochondrial cytochrome c release and active caspase 3 following treatment are indicated. Data shown are means (± SE) of results from 4 independent experiments. (C) Bcl-xL is required for efficient induction of mitochondrial Bax insertion by terphenyl 14. The indicated HeLa cells were treated or not with terphenyl 14 (100 μM) for 18 h. Mitochondria were then isolated and left untreated or treated with alkaline carbonate. The amounts of mitochondrion-bound (untreated mitochondria) and membrane-inserted (alkaline-treated mitochondria) Bax and F1 ATPase (as a control mitochondrial membrane protein) were analyzed by Western blotting. The amount of Bax inserted into mitochondrial membranes (i.e., alkaline resistant) in each condition was evaluated by densitometric analysis and normalized to the amount of protein inserted into mitochondria from control cells treated with terphenyl 14. Data are means (± SE.) of results from four independent experiments. P values were assessed using a Student t test. (D) Mitochondria from HeLa cells are intrinsically sensitive to induction of Bcl-xL-dependent cytochrome c release by terphenyl 14. Mitochondria isolated from the indicated HeLa cells were incubated with terphenyl 14 in standard mitochondrial buffer for 1 h at 37°C. The amounts of cytochrome c present in the mitochondrial fraction and in the mitochondrial supernatant (“released”) were then analyzed by Western blotting. Data representative of three independent experiments are shown. F1 ATPase was used as a control mitochondrial membrane protein.

To further investigate the role played by Bcl-xL in terphenyl 14-induced cell death, we used HeLa cells in which either Bax or Bcl-xL expression was selectively downregulated by the stable expression of recombinant plasmids that express shRNA (HeLa pSilencer Bax and pSilencer Bcl-xL cells, respectively; note that Bcl-xL reduction in HeLa cells could be maintained in culture over numerous passages). Terphenyl 14 treatment of control cells inhibited the interactions between Bax and Bcl-xL, and terphenyl 14 was less cytotoxic in HeLa cells in which either Bax or Bcl-xL expression was selectively downregulated compared to results for control cells (data not shown). Likewise, human glioblastoma cells depleted in either Bax or Bcl-xL by stable expression of pSilencer plasmids (26) were more resistant to induction of cell death by terphenyl 14 (data not shown). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that Bcl-xL knockdown HeLa cells, akin to Bax knockdown HeLa cells, were resistant to induction of cytochrome c release by terphenyl 14 treatment (Fig. 5B). Subcellular fractionation analysis indicated, in agreement with a previous report (38), that Bax was present in mitochondria isolated from control HeLa cells. Most of these Bax molecules were “peripherally” associated with mitochondria and could be detached from the mitochondrial fraction following alkaline treatment (Fig. 5C). Addition of terphenyl 14 to control HeLa cells induced the insertion of mitochondrially localized Bax into mitochondrial membranes, as indicated by the increase in the amount of alkaline-resistant mitochondrial Bax (Fig. 5C). Terphenyl 14 treatment induced Bax insertion into mitochondrial membranes much less efficiently in Bcl-xL knockdown cells (Fig. 5C). This is in strong agreement with the notion that Bcl-xL-dependent Bax mitochondrial insertion is critical for the induction of mitochondrial permeabilization by terphenyl 14.

Intriguingly, terphenyl 14 treatment induced only modest changes in the amounts of Bax present in mitochondrial or cytosolic fractions (Fig. 5C and data not shown). This suggests that terphenyl 14-induced, Bax-dependent mitochondrial permeabilization essentially ensues from an effect of the peptidomimetic on proteins already at the mitochondria, where Bax/Bcl-xL complexes were reported to reside (47). To confirm this, we directly incubated terphenyl 14 with mitochondria isolated from HeLa cells. Terphenyl 14 induced cytochrome c release from mitochondria isolated from control HeLa cells but had no detectable effect at the concentrations used on mitochondria isolated either from Bax knockdown, or from Bcl-xL knockdown cells (Fig. 5D). Thus, the permeability of mitochondria from HeLa cells exhibits an inherent sensitivity to terphenyl 14 which relies on Bax and also, most importantly, on Bcl-xL.

The ability of Bcl-xL to cooperate with terphenyl 14 is prevented by a single mutation in Bcl-xL that abrogates its interaction with Bax.

We further investigated whether the ability of Bcl-xL to interact with Bax is required for Bcl-xL to mediate terphenyl 14-induced Bax activation, using the G138A mutant of Bcl-xL. The interaction of this mutant with Bax is abrogated by a single mutation in the BH1 domain of Bcl-xL (29, 31) (Fig. 2A). Fluorescence polarization assays indicated that this mutant was still capable of binding Bad-BH3 and that terphenyl 14 disrupted this interaction (Table 1). Thus, Bcl-xL G138A is deficient for the interaction with Bax but not for the interaction with terphenyl 14.

HeLa cells were depleted in Bcl-xL by the lentivirus approach described above, prior to reintroduction of Bcl-xL variants by transient transfection with plasmids that express the corresponding cDNA, modified in the shRNA target sequence in order to make it resistant to inhibition by RNA interference. Wild-type Bcl-xL restored the sensitivity of Bcl-xL knockdown HeLa cells to terphenyl 14, but the G138A mutant did not (Fig. 6A). In contrast, a variant of Bcl-xL lacking 23 amino acids at its C terminus (Bcl-xL ΔTM) and unable to localize at the mitochondria (32) (immunohistochemical analysis confirmed the cytosolic localization of this deletion mutant; data not shown) and a variant carrying a single mutation in the BH3 domain of Bcl-xL (Bcl-xL L90A) that abrogates the proapoptotic activity of Bcl-xS, and thus the prodeath activity of this domain (7), were as efficient as wild-type Bcl-xL. Similar results were obtained in HCT116 p21−/− Puma−/− cells (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

The Bcl-xL G138A mutant does not cooperate with terphenyl 14. (A and B) Transiently transfected Bcl-xL G138A does not restore the sensitivity of Bcl-xL knockdown HeLa cells (A) or HCT116 p21−/− Puma−/− cells (B) to terphenyl 14. Cells were infected with an shBcl-xL lentivirus prior to transfection with plasmids expressing shRNA-resistant cDNAs encoding the indicated Bcl-xL variant or with empty vector and treatment or not with terphenyl 14 (100 μM). Death rates in the resulting cells were evaluated 24 h later. Data are means (± SE) of results from three independent experiments. (Right) Western blot analysis of Bcl-xL expression was performed to assess the efficiency of RNA interference (using cells infected with a control lentivirus, Scr, as a positive control) and of transduction in each condition. β-Tub., β-tubulin. (C) Microinjection of recombinant Bcl-xL G138A does not restore the sensitivity of Bcl-xL knockdown HeLa cells to terphenyl 14. Recombinant GST, GST-Bcl-xL, or GST-Bcl-xL G138A (1 μM) were microinjected together with the fluorescent marker FITC-Dextran 40S (0.5%) in the indicated HeLa cells 6 h prior to their treatment with terphenyl 14. The percentage of microinjected (i.e., fluorescent) cells exhibiting morphological features of cell death was assayed 18 h later. Data are means (± SE) of results from at least three independent experiments. (D) Resistance of Bcl-xL−/− cells to terphenyl 14. Wild-type and Bcl-xL−/− MEFs were treated with terphenyl 14 (100 μM) or DMSO carrier alone for 18 h. The activation of DEVDase (top) (A.U., arbitrary units) and the loss of cell viability (bottom) following treatment were then assayed. Data are means (± SEM) of results from 3 independent experiments. (E) Transiently transfected Bcl-xL but not Bcl-xL G138A cooperates with terphenyl 14 to promote cell death in Bcl-xL knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Bcl-x−/− MEFs transfected with the indicated plasmids together with a plasmid encoding the red fluorescent protein (RFP) DsRed as a transfection marker were treated with terphenyl 14 for 18 h prior to morphological analysis of fluorescent cells. Data are means (± SE) of results from four independent experiments. P values were assessed using a Student t test.

These data imply that the localization of Bcl-xL at membranes appears dispensable for it to promote the effects of terphenyl 14. They also imply that Bcl-xL-dependent induction of cell death by terphenyl 14 is unlikely to rely on a process wherein the compound causes Bcl-xL to expose its own BH3 domain. In contrast, the BH3-binding activity of Bcl-xL appears to play an essential role. Consistent with this, microinjected wild-type Bcl-xL but not Bcl-xL G138A restored the sensitivity of Bcl-xL knockdown (pSilencer Bcl-xL) HeLa cells to terphenyl 14-induced cell death (Fig. 6C). We also found that immortalized mouse embryonic fibroblasts derived from mice in which Bcl-xL had been genetically eliminated (Bcl-x−/− MEFS) were more resistant to terphenyl 14 treatment than control MEFs (Fig. 6D). Wild-type Bcl-xL but not Bcl-xL G138A overcame the resistance of Bcl-x−/− MEFS to terphenyl 14 treatment (Fig. 6E).

ABT-737 also promotes Bcl-xL-dependent Bax activation.

We investigated whether BH3 mimetic molecules other than terphenyl 14 trigger Bcl-xL-dependent Bax activation using ABT-737.

We first performed cell-free immunoprecipitation assays of IVTR Bax in the presence or absence of recombinant Bcl-xL as described above (Fig. 7A). ABT-737 released IVTR Bax from Bcl-xL, as judged by the presence, in the unbound fraction after treatment, of IVTR Bax that immunoprecipitated with the 2D2 anti-Bax antibody. These molecules had undergone a change in conformation as they immunoreacted with the 6A7 antibody. Terphenyl 14, as reported above, and peptides encompassing the BH3 domains of Bad and Bax (which interfere with Bax Bcl-xL interactions [4]) also released active Bax molecules from Bcl-xL. In contrast, a negative-control mutant Bax-BH3 peptide (L63A) was unable to release Bax molecules from Bcl-xL (Fig. 7A).

FIG. 7.

ABT-737 promotes Bcl-xL-dependent Bax activation. (A) ABT-737 impacts Bax conformation in the presence of Bcl-xL in cell-free assays. Bottom, 35S-Bax bound to recombinant His-Bcl-xL was treated with terphenyl 14 (10 μM), ABT-737 (1 μM), or the indicated BH3 peptides. The resulting “free” Bax molecules were then immunoprecipitated with the 2D2 or 6A7 anti-Bax antibody. Top, 35S-Bax was directly treated with the indicated compounds and peptides in the absence of Bcl-xL prior to immunoprecipitation. (B) Expression of Bax and Bcl-xL renders yeast cells sensitive to ABT-737. The effect of a 6-h ABT-737 treatment (20 μM) on Bax/Bcl-xL interactions was evaluated and quantified as described in the legend for Fig. 4A and B. Data are means (± SE) of results from three independent experiments. The effect of the same treatment on the viability of yeast cells expressing the indicated protein was evaluated as described in the legend for Fig. 4C. Data are means (± SEM) of results from 8 independent experiments. P values (*, P < 0.005) were assessed using a Student t test. (C) Ectopic expression of Bax sensitizes HeLa cells to ABT-737 by a Bcl-xL-dependent process. HeLa cells were infected with the indicated lentivirus, as described in the legend for Fig. 6A, transfected with the indicated plasmids, and treated or not with ABT-737 (5 μM) for 18 h prior to evaluation of cell death. Data are means (± SEM) of results from 3 independent experiments. Bottom insert, Western blot analysis of Bax expression was performed to assess transduction efficiency in each condition. (D) Acute knockdown of Bcl-xL mitigates cell death induced by ABT-737 in combination with Mcl-1 downregulation. HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated sequence of siRNA prior to treatment with ABT-737 (1 μM), terphenyl 14 (100 μM), or vehicle alone for an additional 24 h, and loss of cell viability was evaluated. Cell death rates induced by each combination of siRNA in the absence of treatment are represented in white, while the specific cell death rates observed in the presence of compound are shown in gray and black (for ABT-737 and terphenyl 14, respectively). Data are means (± SE) of results from three independent experiments. Note that death rates measured in untreated siCtr/siCtr and siBcl-xL/siCtr cells are shown twice, below ABT-737 and terphenyl 14-induced death rates, respectively. The bottom shows representative Western blotting, confirming the specificity of the RNA interference approach targeting Bcl-xL and Mcl-1 expression. (E) Knockdown of Bax mitigates cell death induced by ABT-737 in combination with Mcl-1 downregulation. Control (Scr) or Bax knockdown (shBax, expressing pSilencer Bax) HeLa cells were transfected with control siRNA (siCtr) or siMcl-1 nucleotides 24 h before their treatment for an additional 24 h with ABT-737 (1 μM) or vehicle alone, followed by evaluation of loss of cell viability. Data (represented as in panel D) are means (± SE) of results from four independent experiments.

Second, we treated yeast cells that express Bax and/or Bcl-xL with concentrations of ABT-737 (20 μM) that inhibited Bax/Bcl-xL interactions (Fig. 7B). This treatment significantly affected the viability of yeast cells if and only if they expressed both Bax and Bcl-xL, indicating that, as in the case of terphenyl 14, disruption of Bax/Bcl-xL interactions by ABT-737 suffices to initiate cell death.

We then explored whether ABT-737 can trigger Bcl-xL-dependent activation of Bax in mammalian cells. We used HeLa cells and transfected them with untagged Bax under conditions under which ectopic Bax expression did not promote cell death by itself (Fig. 7C). Such transfection was nevertheless sufficient to sensitize cells that had been infected with a control lentivirus (scr) to induction of cell death by ABT-737. This effect was dependent upon endogenous Bcl-xL, since it was not observed in cells that had been infected with a shBcl-xL lentivirus (Fig. 7C). Reintroduction of wild-type Bcl-xL (using a shRNA-resistant cDNA) restored the sensitivity of Bcl-xL knockdown cells, but this was not the case for the G138A mutant (Fig. 7C). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that ABT-737 uses Bax-binding Bcl-xL molecules to promote death of cells with enhanced Bax expression.

To confirm that ABT-737 can promote Bcl-xL-dependent cell death, we analyzed what role Bcl-xL might play in cell death induction by ABT-737 in HeLa cells that are depleted in Mcl-1, a Bcl-2 homolog which is not targeted by ABT-737 (30). HeLa cells were transiently transfected with siRNA nucleotides targeting Bcl-xL and/or Mcl-1 prior to treatment with ABT-737. Knockdown of Mcl-1 enhanced the specific response to ABT-737 (Fig. 7D). Importantly, stable Bax knockdown HeLa cells (pSilencer Bax cells described above) were significantly less sensitive to ABT-737 treatment after Mcl-1 downregulation than control cells (Fig. 7E), indicating that Bax contributes, at least in part, to induction of cell death in ABT-737-treated, Mcl-1-depleted HeLa cells. Cell death rates specifically induced by ABT-737 treatment in Mcl-1-depleted cells were reduced when Bcl-xL expression was coincidentally downregulated (Fig. 7D). Knockdown of Bcl-xL expression by this approach also promoted resistance of HeLa cells to the specific effects of terphenyl 14 (Fig. 7D). Thus, like that induced by terphenyl 14, cell death induced by ABT-737 combined with Mcl-1 downregulation is partly Bcl-xL dependent.

DISCUSSION

The recent observation that neutralization of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 members might suffice to allow Bax-mediated apoptosis (42) suggests that in healthy cells, without the involvement of BH3 activators, a proportion of Bax molecules may exist in a “primed” state, complexed to prosurvival proteins such as Bcl-xL (1). Our results are consistent with this view and further imply that Bcl-xL itself contributes to the induction and/or maintenance of such an activated “primed” state for Bax, since endogenous Bcl-xL allows terphenyl 14 to unleash enough active Bax to permeabilize mitochondria and kill cells. The cell-free assays and the cellular assays using variants of Bcl-xL described here indicate that while an exposure of the BH3 domain of Bcl-xL is unlikely to be involved and a membrane localization of Bcl-xL is dispensable, the BH3 binding interface of this protein is crucial to this process. Our data thus strongly support the notion that the Bcl-xL dependency of terphenyl 14 activity depends on a process whereby Bax, “trapped” by Bcl-xL, is released in an active form upon inhibition of the BH3-binding activity of Bcl-xL.

We currently do not know whether this “trap and release” process extends to other multidomain Bcl-2 family members. The resistance of Bcl-xL knockout cells to terphenyl 14 is incomplete, implying that other targets might be involved in the biological effects of this compound. Terphenyl 14 inhibits not only the BH3-binding activity of Bcl-xL but also those of Mcl-1 and of Bcl-2 (data not shown), and the latter protein recapitulates the ability of Bcl-xL to release active Bax in response to sensitizer BH3 peptides in cell-free assays (4). It is also noteworthy that because Bax played a major role in the apoptotic responses studied here, the present work cannot investigate how Bcl-xL inhibition might recruit the activity of the other proapoptotic multidomain protein, Bak.

Our findings imply that inhibition of the direct interaction between Bcl-xL and Bax can launch a Bax-dependent apoptotic program even in the absence of direct, highly efficient BH3 activators. This is best exemplified by the experiments performed in yeast. Moreover, we demonstrated Bcl-xL-dependent induction of mammalian apoptosis by the terphenyl compound using mammalian cells that do not harbor constitutive BH3 activator-related death signals that render Bcl-xL necessary to maintain viability (and that tolerate Bcl-xL downregulation) or mammalian cells in which tolerance to Bcl-xL depletion was induced precisely by knocking out the expression of the activator BH3-only protein, which is involved in rendering Bcl-xL acutely necessary for the survival of these cells (HCT116 p21−/− Puma−/−). The fact that BH3 activators are dispensable for the triggering of cell death signals by the sole displacement of Bax from Bcl-xL is also supported by the observation that terphenyl 14, which triggers Bcl-xL and Bax-dependent cell death, is unable to recruit Puma by displacing it from Bcl-xL in a whole-cell configuration. This lack of effect contrasts with the ability of the terphenyl compound to compete with the binding of diverse BH3 peptides (including that of Puma) to Bcl-xL in cell-free assays. We speculate it might rely on the fact that the kon rate and/or the koff rate (kon and koff, association and dissociation rate constants, respectively) of terphenyl 14 binding to Bcl-xL is such that the compound cannot efficiently compete with Puma to create free Puma proteins. Of note, the preferential displacement of Bax but not Puma may stem, at least in part, from a difference in the binding affinities of Bax-BH3 versus Puma-BH3 to Bcl-xL since we measured a higher affinity of the Puma-BH3 peptide (41 nM) than of the Bax-BH3 peptide (147 nM) for Bcl-xL, using fluorescence polarization (data not shown).

Our data do not dispute the fact that Bcl-xL exerts its antiapoptotic activity by sequestering BH3 activators or Bax itself. They unravel that the Bcl-xL interaction with Bax shifts the equilibrium toward an activated conformation of Bax. Thus, the nature of this interaction primes Bax and maintains it in an active conformation, so that sustained Bcl-xL activity (and, in particular, sustained binding to Bax) is required for survival. Through this process, certain cancer cells may be “addicted” to Bcl-xL even in the absence of other, more direct Bax-activating signals. Other “addictive” effects of Bcl-2 and/or Bcl-xL have been reported, relying on a shift in energy metabolism from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis upon Bcl-xL overexpression (35) or on an enhancing effect of Bcl-2 on the expression of proapoptotic proteins (27). The addictive process we describe here differs mechanistically from these in that it is the very ability of Bcl-xL to engage a BH3-domain-dependent interaction with Bax, i.e., the property on which its prosurvival activity relies, which is involved.

How is Bax activated by the “trap and release” mechanism? Since Bax may be activated through perturbation at multiple sites (44), we speculate that Bcl-xL sustains this process by facilitating exposure of the BH3 domain of Bax, which is buried inside native Bax. Exposure of the Bax BH3 domain is understood to accompany a general disruption of the hydrophobic core of native Bax formed by helixes α1, α4, α5, and α6 (36) and to facilitate Bax homo-oligomerization (46), which may be sufficient for Bax induction of apoptosis (12). We thus suggest that Bcl-xL permits a conformational change in native Bax by engaging its BH3 domain. Additional regions, distinct from these that constitute the Bcl-xL BH3 binding site sensu stricto, might be involved in the initial interactions bringing about such a conformational change (Fig. 8A). Alternatively, Bcl-xL might bind Bax molecules with an open BH3 domain that could arise from a nonfavored equilibrium in the absence of acute stress (Fig. 8B). In each case, Bcl-xL would maintain “open” Bax molecules in a bound state and preserve viability at the same time that it favors the existence of “primed” Bax molecules (with their BH3 domain exposed). Disruption of Bcl-xL/Bax complexes would then unleash free, membrane insertion-competent Bax molecules that initiate cell death. Further feed-forward mechanisms might intervene, since relatively small amounts of active Bax molecules may suffice to initiate cell death (20) (48).

FIG. 8.

Model for Bax activation by its interaction with and then release by Bcl-xL. Mitoch., mitochondrial. See the text for details.

Since our model implies that BH3 mimetic molecules other than terphenyl 14 might trigger Bcl-xL-dependent Bax activation, the fact that ABT-737 uses Bcl-xL in certain instances to promote Bax-dependent cell death is particularly significant. This feature is apparent once Mcl-1 expression is downregulated, whereas Bcl-xL-dependent induction of cell death by terphenyl 14 is detected even in the presence of Mcl-1 in the same cellular context (Fig. 7). This difference is likely to stem from the fact that terphenyl 14 can counteract the ability of Mcl-1 to prevent apoptosis. ABT-737 also differs from terphenyl 14 in that it much more efficiently binds to the BH3-binding interface of Bcl-xL. We speculate that upon prolonged treatment with ABT-737, this property might paradoxically mitigate the “trap and release” process by preventing de novo formation of Bax/Bcl-xL complexes. Reciprocally, the Bcl-xL-dependent process might be more manifest when disruption of existing complexes prevails over inhibition of complex formation. We observed that cycloheximide enhances the sensitivity of HeLa cells to induction of death by ABT-737 in a Bcl-xL-dependent manner (data not shown). This might result from a specific effect on the expression of short-lived Mcl-1 but also from additional consequences of de novo protein synthesis inhibition.

ABT-737 not only displaces Bax from its antiapoptotic targets but also BH3 activators such as Bim or Puma, thereby recruiting their ability to activate Bax to induce efficient cell death (see reference 24). Yet some observations had hinted that parameters other than the sole displacement of BH3 activators from Bcl-2 homologues might intervene: (i) sensitivity to ABT-737 was suggested to rely on its ability to disrupt Bcl-2 interactions with Bax itself (17); (ii) overexpression of Bcl-xL does not promote resistance against ABT-737 (35); (iii) resistance of small-cell lung cancer cell lines to ABT-737 coincides with low expression of Bim and high expression of Mcl-1 but also with low expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL (37). Our results imply that the disruption of complexes between Bax and Bcl-xL is one additional parameter that contributes to sensitivity to ABT-737 and thus to the clinical efficiency of analogous compounds, such as that of an oral version of ABT-737, ABT-263, which has entered clinical trials. From a more-general perspective, our data imply that the cancer cell response to a given Bcl-xL inhibitor relies on the nature of the interactions engaged in by Bcl-xL and on the nature of the interactions this inhibitor can disrupt. “Free” Bcl-xL molecules will correlate with resistance, and molecules occupied by BH3 activators and/or Bax itself will correlate with sensitivity. Understanding how the interactions of Bcl-xL with BH3 activators and with Bax are regulated in cancer cells (and in particular, how they impact on each other) is therefore crucial to understanding by which molecular mechanisms Bcl-xL contributes to the aberrant survival of these cells.

Acknowledgments

We feel indebted to Muriel Priault for her generous sharing of reagents and for her advice. We thank David Huang for the gift of wild-type and Bcl-xL knockout MEFs and Jean Claude Martinou for His-tagged recombinant proteins. We thank Lisa Oliver for fruitful comments.

P.J. is supported by ARC (no. 4895), Fondation de France (Tumor Committee), Région Pays de la Loire (CIMATH network), and Institut de Recherche Servier.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 December 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, J. M., and S. Cory. 2007. The Bcl-2 apoptotic switch in cancer development and therapy. Oncogene 26:1324-1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amundson, S. A., et al. 2000. An informatics approach identifying markers of chemosensitivity in human cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 60:6101-6110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arokium, H., N. Camougrand, F. M. Vallette, and S. Manon. 2004. Studies of the interaction of substituted mutants of BAX with yeast mitochondria reveal that the C-terminal hydrophobic alpha-helix is a second ART sequence and plays a role in the interaction with anti-apoptotic BCL-xL. J. Biol. Chem. 279:52566-52573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cartron, P. F., et al. 2004. The first alpha helix of Bax plays a necessary role in its ligand-induced activation by the BH3-only proteins Bid and PUMA. Mol. Cell 16:807-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cartron, P. F., L. Oliver, E. Mayat, K. Meflah, and F. M. Vallette. 2004. Impact of pH on Bax alpha conformation, oligomerisation and mitochondrial integration. FEBS Lett. 578:41-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cartron, P. F., et al. 2003. The N-terminal end of Bax contains a mitochondrial-targeting signal. J. Biol. Chem. 278:11633-11641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang, B. S., et al. 1999. The BH3 domain of Bcl-x(S) is required for inhibition of the antiapoptotic function of Bcl-x(L). Mol. Cell. Biol. 9:6673-6681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chipuk, J. E., et al. 2008. Mechanism of apoptosis induction by inhibition of the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:20327-20332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del Gaizo Moore, V., et al. 2007. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia requires BCL2 to sequester prodeath BIM, explaining sensitivity to BCL2 antagonist ABT-737. J. Clin. Invest. 117:112-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desagher, S., et al. 1999. Bid-induced conformational change of Bax is responsible for mitochondrial cytochrome c release during apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 144:891-901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallenne, T., et al. 2009. Bax activation by the BH3-only protein Puma promotes cell dependence on antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members. J. Cell Biol. 185:279-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.George, N. M., J. J. Evans, and X. Luo. 2007. A three-helix homo-oligomerization domain containing BH3 and BH1 is responsible for the apoptotic activity of Bax. Genes Dev. 21:1937-1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillissen, B., et al. 2003. Induction of cell death by the BH3-only Bcl-2 homolog Nbk/Bik is mediated by an entirely Bax-dependent mitochondrial pathway. EMBO J. 22:3580-3590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green, D. R., and G. Kroemer. 2004. The pathophysiology of mitochondrial cell death. Science 305:626-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu, Y. T., K. G. Wolter, and R. J. Youle. 1997. Cytosol-to-membrane redistribution of Bax and Bcl-X(L) during apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:3668-3672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim, H., et al. 2006. Hierarchical regulation of mitochondrion-dependent apoptosis by BCL-2 subfamilies. Nat. Cell Biol. 8:1348-1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konopleva, M., et al. 2006. Mechanisms of apoptosis sensitivity and resistance to the BH3 mimetic ABT-737 in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell 10:375-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kutzki, O., et al. 2002. Development of a potent Bcl-x(L) antagonist based on alpha-helix mimicry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124:11838-11839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuwana, T., et al. 2002. Bid, Bax, and lipids cooperate to form supramolecular openings in the outer mitochondrial membrane. Cell 111:331-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lakhani, S. A., et al. 2006. Caspases 3 and 7: key mediators of mitochondrial events of apoptosis. Science 311:847-851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lalier, L., et al. 2007. Bax activation and mitochondrial insertion during apoptosis. Apoptosis 12:887-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Letai, A. 2009. Puma strikes Bax. J. Cell Biol. 185:189-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Letai, A., et al. 2002. Distinct BH3 domains either sensitize or activate mitochondrial apoptosis, serving as prototype cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell 2:183-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Letai, A. G. 2008. Diagnosing and exploiting cancer's addiction to blocks in apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8:121-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maiuri, M. C., et al. 2007. Functional and physical interaction between Bcl-X(L) and a BH3-like domain in Beclin-1. EMBO J. 26:2527-2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manero, F., et al. 2006. The small organic compound HA14-1 prevents Bcl-2 interaction with Bax to sensitize malignant glioma cells to induction of cell death. Cancer Res. 66:2757-2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitsiades, C. S., et al. 2007. Bcl-2 overexpression in thyroid carcinoma cells increases sensitivity to Bcl-2 homology 3 domain inhibition. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92:4845-4852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moreau, C., et al. 2003. Minimal BH3 peptides promote cell death by antagonizing anti-apoptotic proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 278:19426-19435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muchmore, S. W., et al. 1996. X-ray and NMR structure of human Bcl-xL, an inhibitor of programmed cell death. Nature 381:335-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oltersdorf, T., et al. 2005. An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces regression of solid tumours. Nature 435:677-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ottilie, S., et al. 1997. Structural and functional complementation of an inactive Bcl-2 mutant by Bax truncation. J. Biol. Chem. 272:16955-16961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petros, A. M., E. T. Olejniczak, and S. W. Fesik. 2004. Structural biology of the Bcl-2 family of proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1644:83-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Priault, M., et al. 2003. Investigation of the role of the C-terminus of Bax and of tc-Bid on Bax interaction with yeast mitochondria. Cell Death Differ. 10:1068-1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reed, J. C. 2003. Apoptosis-targeted therapies for cancer. Cancer Cell 3:17-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwartz, P. S., et al. 2007. 2-Methoxy antimycin reveals a unique mechanism for Bcl-x(L) inhibition. Mol. Cancer Ther. 6:2073-2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suzuki, M., R. J. Youle, and N. Tjandra. 2000. Structure of Bax: coregulation of dimer formation and intracellular localization. Cell 103:645-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tahir, S. K., et al. 2007. Influence of Bcl-2 family members on the cellular response of small-cell lung cancer cell lines to ABT-737. Cancer Res. 67:1176-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Terradillos, O., S. Montessuit, D. C. Huang, and J. C. Martinou. 2002. Direct addition of BimL to mitochondria does not lead to cytochrome c release. FEBS Lett. 522:29-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tremblais, K., et al. 1999. The C-terminus of bax is not a membrane addressing/anchoring signal. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 260:582-591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weber, A., et al. 2007. BimS-induced apoptosis requires mitochondrial localization but not interaction with anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins. J. Cell Biol. 177:625-636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Willis, S. N., and J. M. Adams. 2005. Life in the balance: how BH3-only proteins induce apoptosis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 17:617-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Willis, S. N., et al. 2007. Apoptosis initiated when BH3 ligands engage multiple Bcl-2 homologs, not Bax or Bak. Science 315:856-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yin, H., et al. 2005. Terphenyl-based Bak BH3 alpha-helical proteomimetics as low-molecular-weight antagonists of Bcl-xL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127:10191-10196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Youle, R. J., and A. Strasser. 2008. The BCL-2 protein family: opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9:47-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu, J., Z. Wang, K. W. Kinzler, B. Vogelstein, and L. Zhang. 2003. PUMA mediates the apoptotic response to p53 in colorectal cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:1931-1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zha, H., et al. 1996. Structure-function comparisons of the proapoptotic protein Bax in yeast and mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:6494-6508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou, H., Q. Hou, Y. Chai, and Y. T. Hsu. 2005. Distinct domains of Bcl-XL are involved in Bax and Bad antagonism and in apoptosis inhibition. Exp. Cell Res. 309:316-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu, Y., et al. 2006. Bax does not have to adopt its final form to drive T cell death. J. Exp. Med. 203:1147-1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]