Abstract

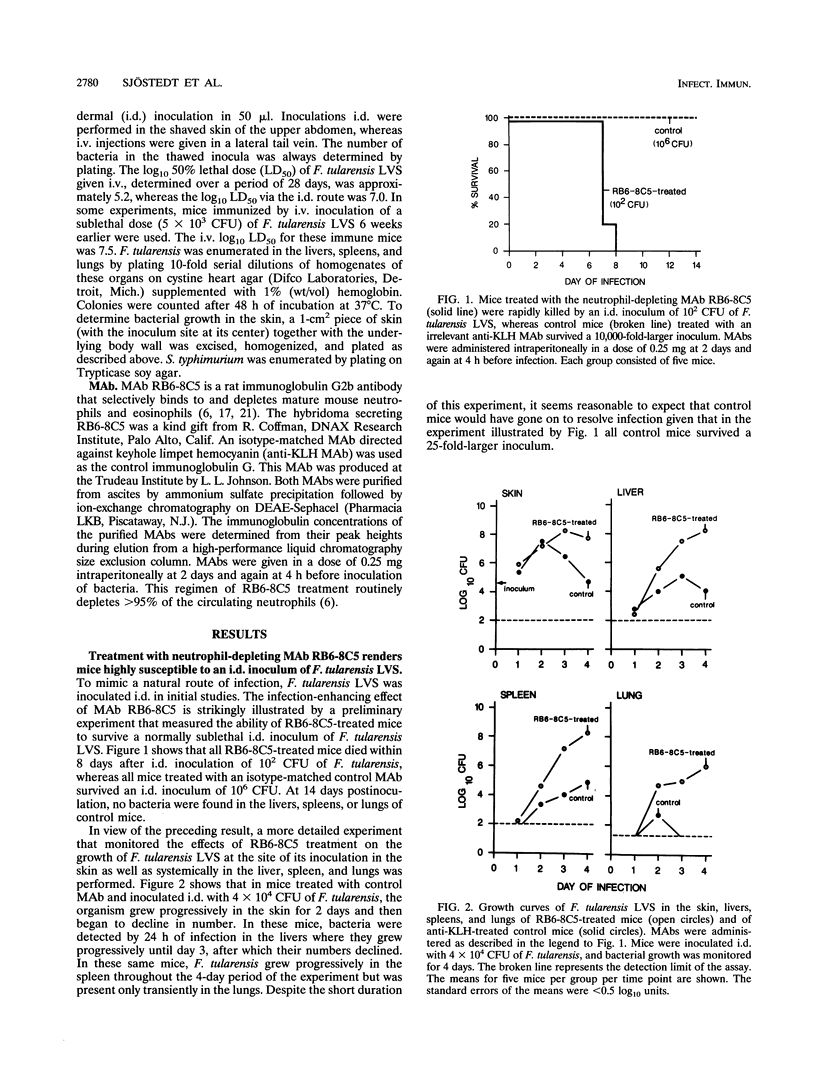

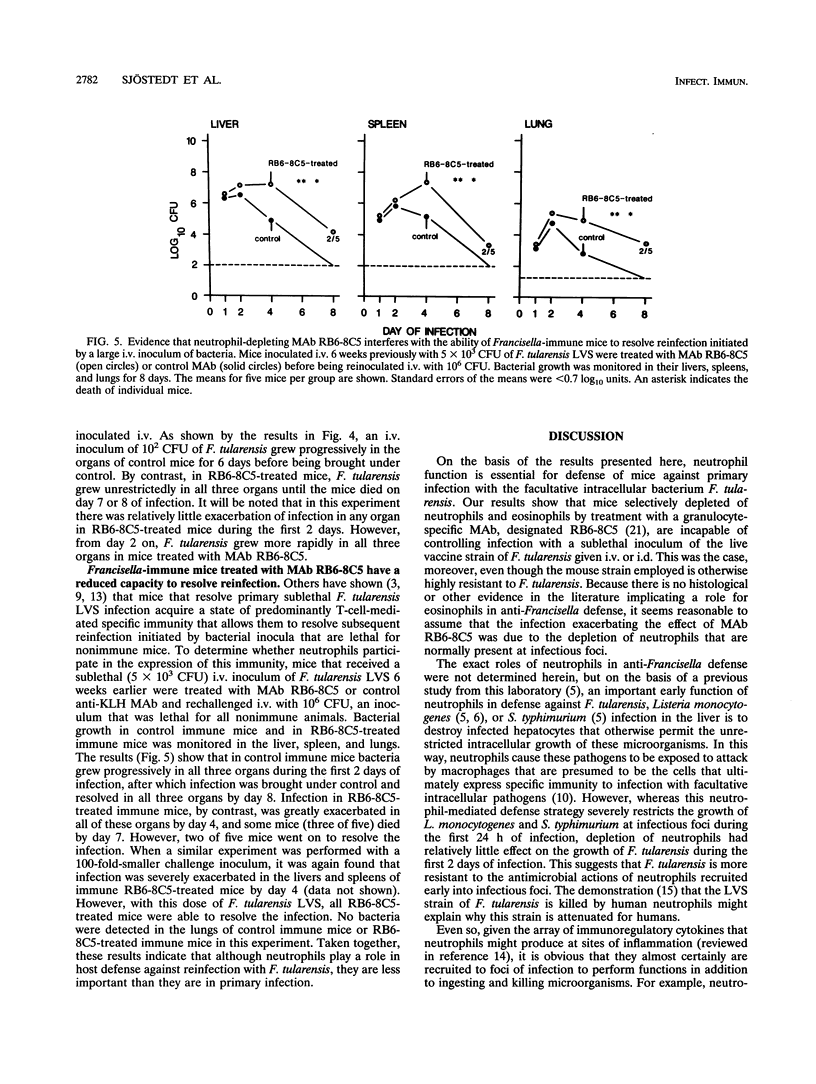

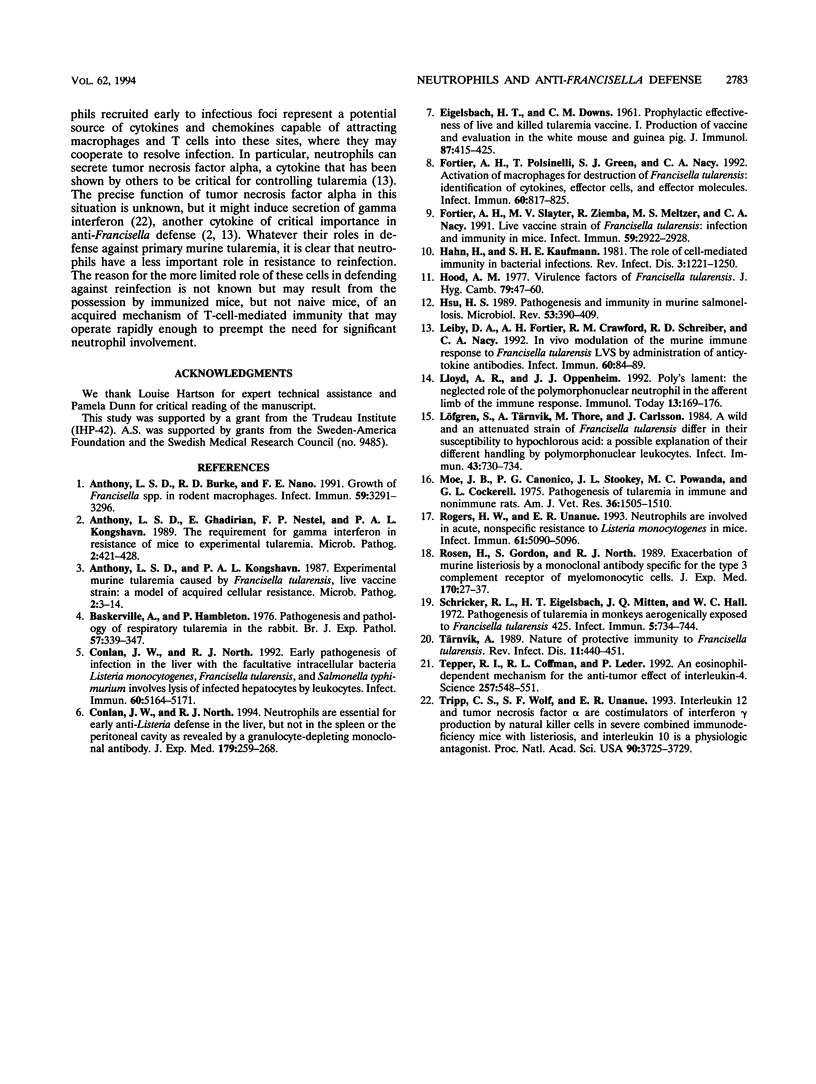

It is generally believed that immunity to experimental infection with the facultative intracellular bacterium Francisella tularensis is an example of T-cell-mediated immunity that is expressed by activated macrophages and mediated by Francisella-specific T cells. According to the results presented herein, neutrophils are also essential for defense against primary infection with this organism. It is shown that mice depleted of neutrophils by treatment with the granulocyte-specific monoclonal antibody RB6-8C5 are rendered defenseless against otherwise sublethal doses of F. tularensis LVS inoculated intravenously or intradermally. In neutrophil-depleted mice, the organism grew progressively in the livers, spleens, and lungs to reach lethal numbers, whereas infection was resolved in normal mice. Although neutrophils were found to resistance to reinfection, their participation was less important. The results suggest that neutrophils are needed for defense against primary infection because they serve to restrict the growth of F. tularensis before it reaches numbers capable of overwhelming a developing specific immune response. The exact way that neutrophils achieve this is not clear at this time, although it is probable that they contribute in ways other than by ingesting and killing the bacterium.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anthony L. D., Burke R. D., Nano F. E. Growth of Francisella spp. in rodent macrophages. Infect Immun. 1991 Sep;59(9):3291–3296. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3291-3296.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony L. S., Ghadirian E., Nestel F. P., Kongshavn P. A. The requirement for gamma interferon in resistance of mice to experimental tularemia. Microb Pathog. 1989 Dec;7(6):421–428. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(89)90022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony L. S., Kongshavn P. A. Experimental murine tularemia caused by Francisella tularensis, live vaccine strain: a model of acquired cellular resistance. Microb Pathog. 1987 Jan;2(1):3–14. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskerville A., Hambleton P. Pathogenesis and pathology of respiratory tularaemia in the rabbit. Br J Exp Pathol. 1976 Jun;57(3):339–347. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlan J. W., North R. J. Early pathogenesis of infection in the liver with the facultative intracellular bacteria Listeria monocytogenes, Francisella tularensis, and Salmonella typhimurium involves lysis of infected hepatocytes by leukocytes. Infect Immun. 1992 Dec;60(12):5164–5171. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.12.5164-5171.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlan J. W., North R. J. Neutrophils are essential for early anti-Listeria defense in the liver, but not in the spleen or peritoneal cavity, as revealed by a granulocyte-depleting monoclonal antibody. J Exp Med. 1994 Jan 1;179(1):259–268. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EIGELSBACH H. T., DOWNS C. M. Prophylactic effectiveness of live and killed tularemia vaccines. I. Production of vaccine and evaluation in the white mouse and guinea pig. J Immunol. 1961 Oct;87:415–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortier A. H., Polsinelli T., Green S. J., Nacy C. A. Activation of macrophages for destruction of Francisella tularensis: identification of cytokines, effector cells, and effector molecules. Infect Immun. 1992 Mar;60(3):817–825. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.817-825.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortier A. H., Slayter M. V., Ziemba R., Meltzer M. S., Nacy C. A. Live vaccine strain of Francisella tularensis: infection and immunity in mice. Infect Immun. 1991 Sep;59(9):2922–2928. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.2922-2928.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn H., Kaufmann S. H. The role of cell-mediated immunity in bacterial infections. Rev Infect Dis. 1981 Nov-Dec;3(6):1221–1250. doi: 10.1093/clinids/3.6.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood A. M. Virulence factors of Francisella tularensis. J Hyg (Lond) 1977 Aug;79(1):47–60. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400052840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu H. S. Pathogenesis and immunity in murine salmonellosis. Microbiol Rev. 1989 Dec;53(4):390–409. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.4.390-409.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiby D. A., Fortier A. H., Crawford R. M., Schreiber R. D., Nacy C. A. In vivo modulation of the murine immune response to Francisella tularensis LVS by administration of anticytokine antibodies. Infect Immun. 1992 Jan;60(1):84–89. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.1.84-89.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd A. R., Oppenheim J. J. Poly's lament: the neglected role of the polymorphonuclear neutrophil in the afferent limb of the immune response. Immunol Today. 1992 May;13(5):169–172. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90121-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löfgren S., Tärnvik A., Thore M., Carlsson J. A wild and an attenuated strain of Francisella tularensis differ in susceptibility to hypochlorous acid: a possible explanation of their different handling by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Infect Immun. 1984 Feb;43(2):730–734. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.2.730-734.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moe J. B., Canonico P. G., Stookey J. L., Powanda M. C., Cockerell G. L. Pathogenesis of tularemia in immune and nonimmune rats. Am J Vet Res. 1975 Oct;36(10):1505–1510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers H. W., Unanue E. R. Neutrophils are involved in acute, nonspecific resistance to Listeria monocytogenes in mice. Infect Immun. 1993 Dec;61(12):5090–5096. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.12.5090-5096.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen H., Gordon S., North R. J. Exacerbation of murine listeriosis by a monoclonal antibody specific for the type 3 complement receptor of myelomonocytic cells. Absence of monocytes at infective foci allows Listeria to multiply in nonphagocytic cells. J Exp Med. 1989 Jul 1;170(1):27–37. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schricker R. L., Eigelsbach H. T., Mitten J. Q., Hall W. C. Pathogenesis of tularemia in monkeys aerogenically exposed to Francisella tularensis 425. Infect Immun. 1972 May;5(5):734–744. doi: 10.1128/iai.5.5.734-744.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepper R. I., Coffman R. L., Leder P. An eosinophil-dependent mechanism for the antitumor effect of interleukin-4. Science. 1992 Jul 24;257(5069):548–551. doi: 10.1126/science.1636093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripp C. S., Wolf S. F., Unanue E. R. Interleukin 12 and tumor necrosis factor alpha are costimulators of interferon gamma production by natural killer cells in severe combined immunodeficiency mice with listeriosis, and interleukin 10 is a physiologic antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993 Apr 15;90(8):3725–3729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tärnvik A. Nature of protective immunity to Francisella tularensis. Rev Infect Dis. 1989 May-Jun;11(3):440–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]