Abstract

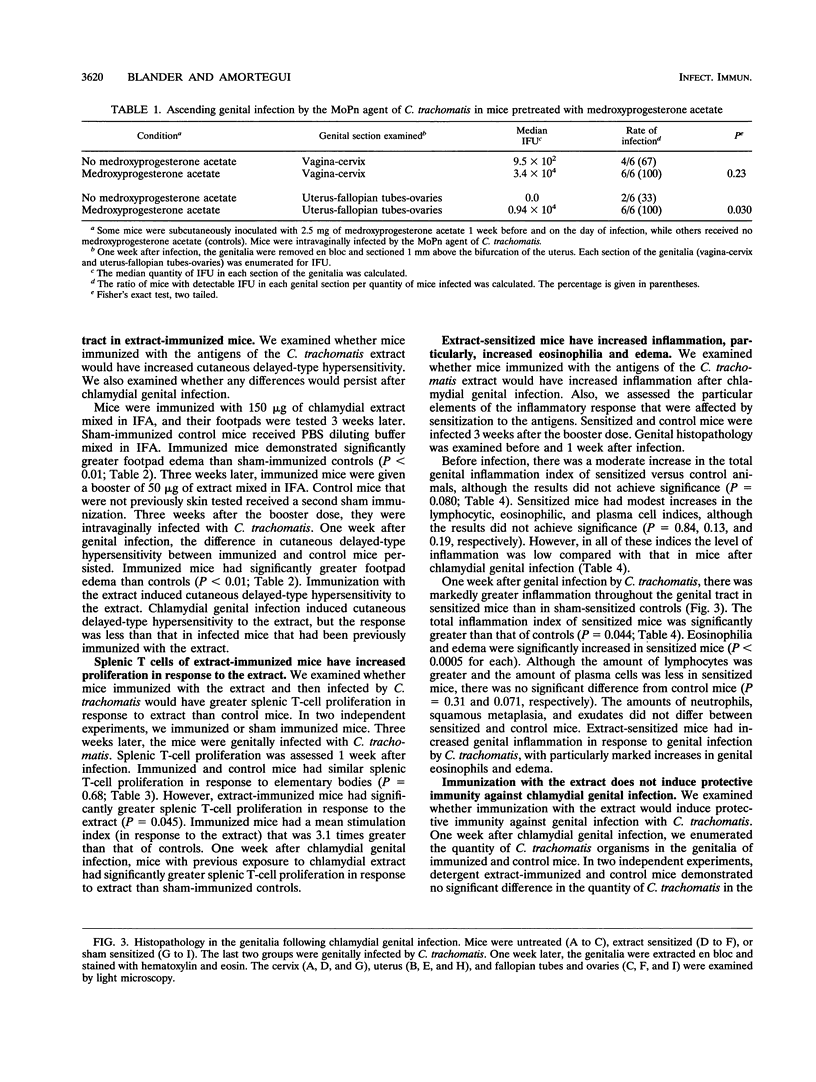

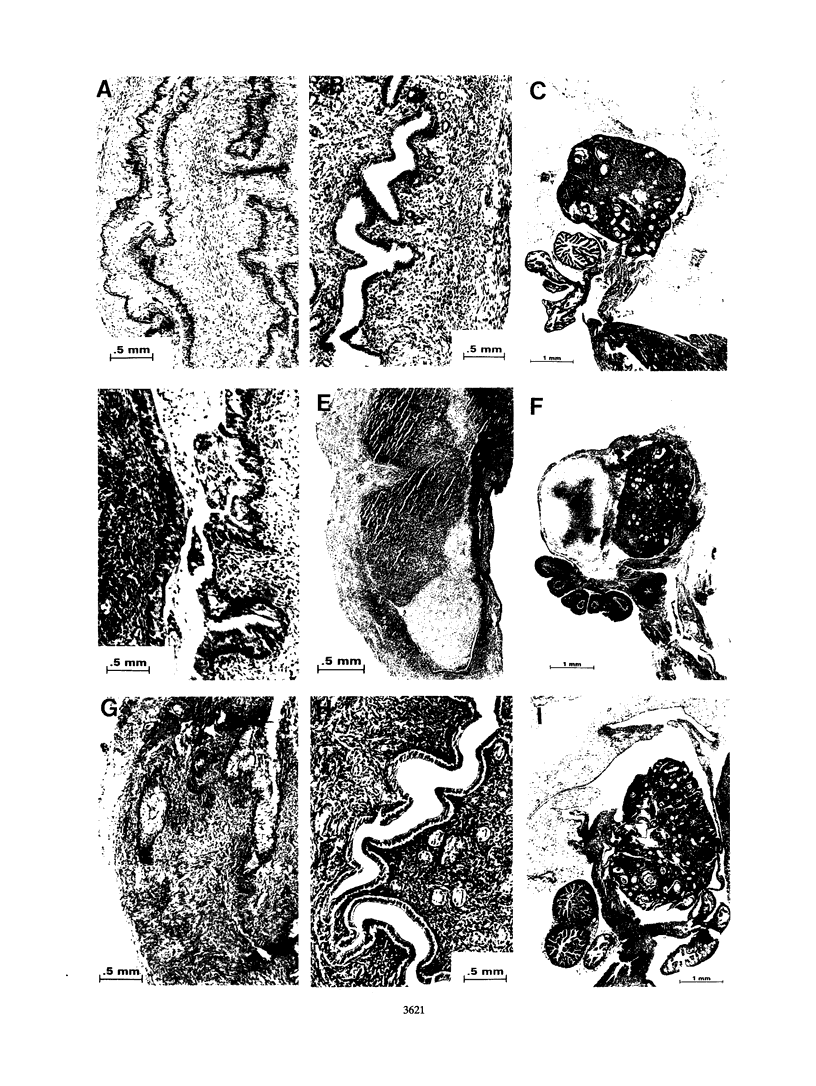

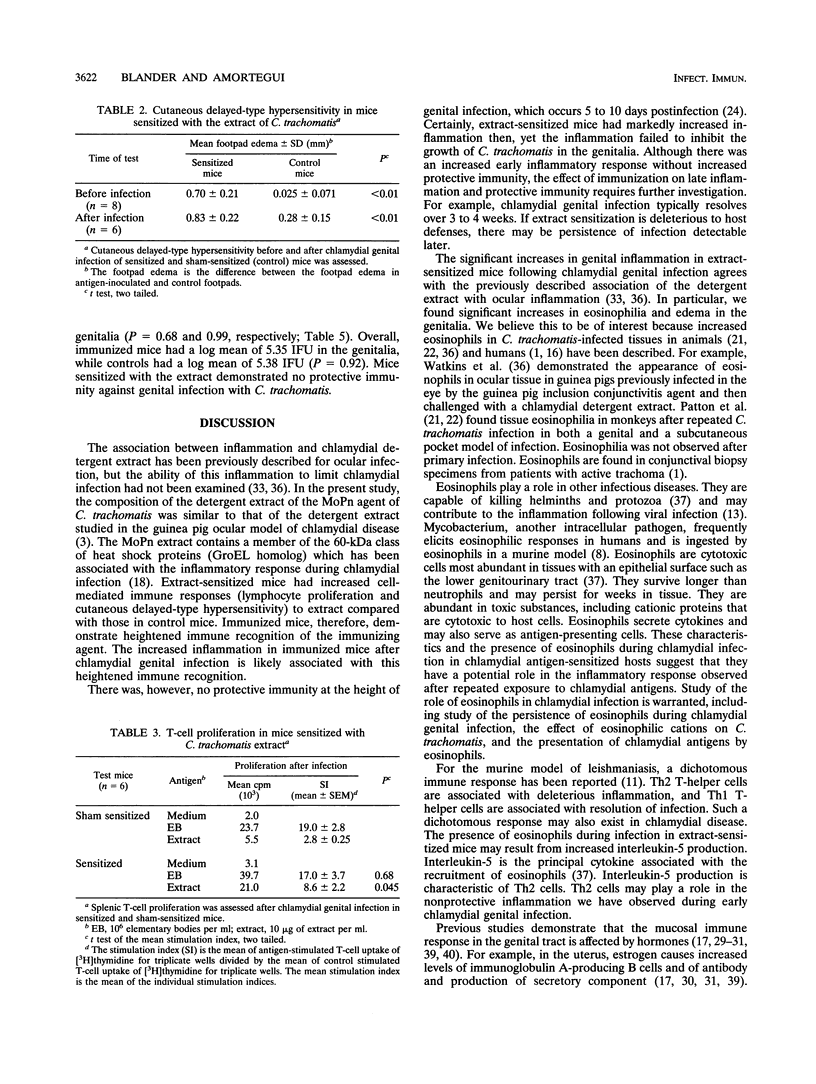

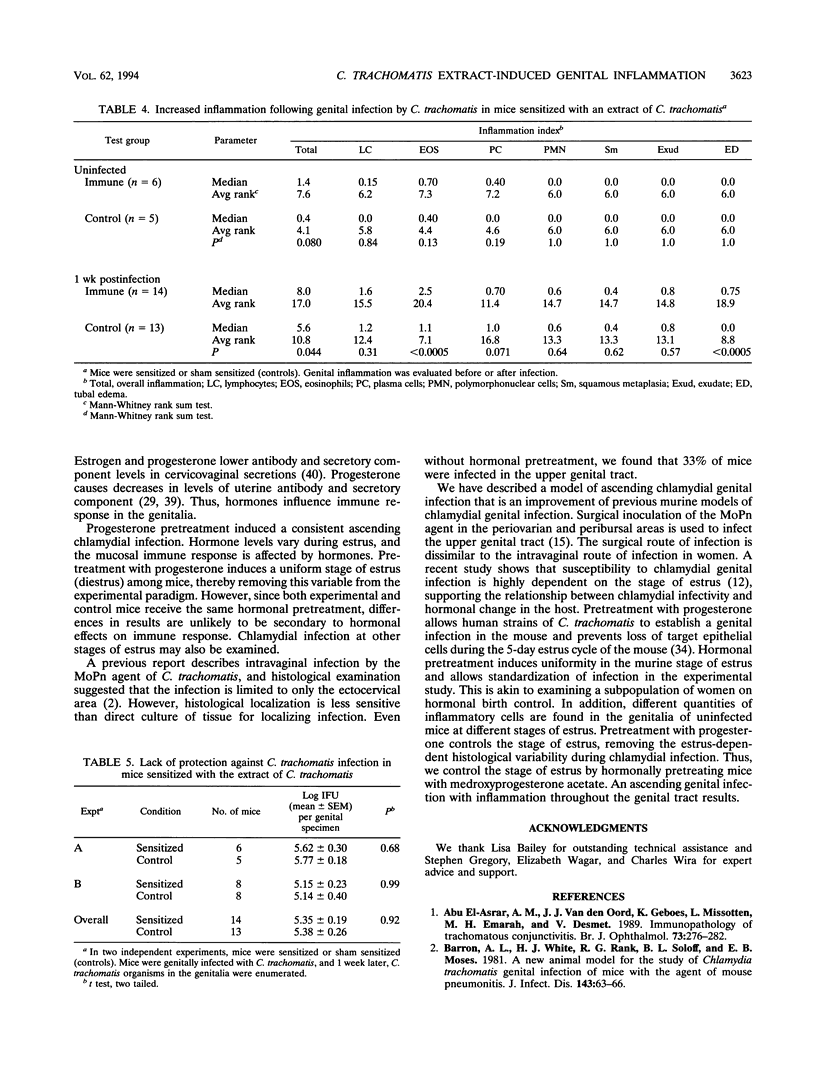

We have determined that immunization with a detergent extract of the mouse pneumonitis agent of Chlamydia trachomatis fails to induce a protective inflammatory immune response following genital infection by C. trachomatis. We demonstrated that mice immunized with the detergent extract have increased cutaneous delayed-type hypersensitivity and increased splenic T-cell proliferation in response to the chlamydial extract. After genital infection by C. trachomatis, extract-sensitized mice had significantly increased genital inflammation (P = 0.044) compared with controls. The inflammation was characterized by significantly increased eosinophils in the genitalia (P < 0.0005) and increased genital edema (P < 0.0005). However, the increased genital inflammation of extract-sensitized mice provided no increase in protection against infection (P = 0.92).

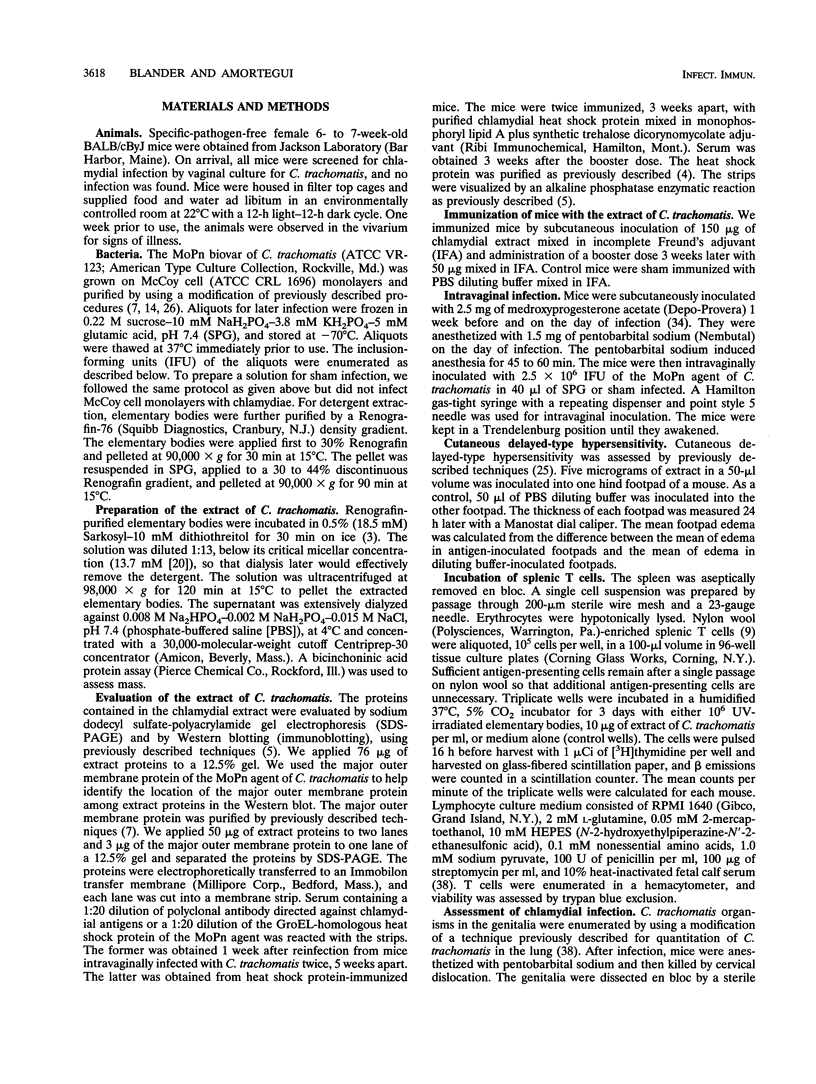

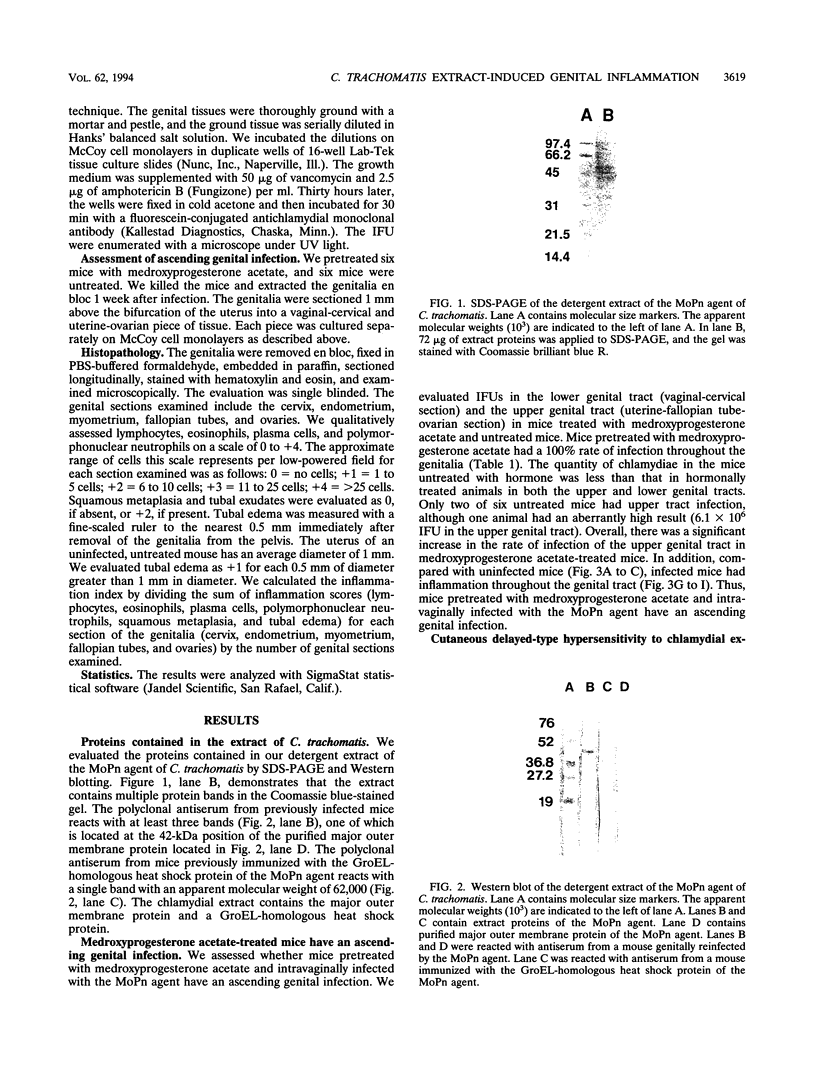

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barron A. L., White H. J., Rank R. G., Soloff B. L., Moses E. B. A new animal model for the study of Chlamydia trachomatis genital infections: infection of mice with the agent of mouse pneumonitis. J Infect Dis. 1981 Jan;143(1):63–66. doi: 10.1093/infdis/143.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavoil P., Stephens R. S., Falkow S. A soluble 60 kiloDalton antigen of Chlamydia spp. is a homologue of Escherichia coli GroEL. Mol Microbiol. 1990 Mar;4(3):461–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blander S. J., Horwitz M. A. Vaccination with Legionella pneumophila membranes induces cell-mediated and protective immunity in a guinea pig model of Legionnaires' disease. Protective immunity independent of the major secretory protein of Legionella pneumophila. J Clin Invest. 1991 Mar;87(3):1054–1059. doi: 10.1172/JCI115065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell H. D., Kromhout J., Schachter J. Purification and partial characterization of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1981 Mar;31(3):1161–1176. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.3.1161-1176.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro A. G., Esaguy N., Macedo P. M., Aguas A. P., Silva M. T. Live but not heat-killed mycobacteria cause rapid chemotaxis of large numbers of eosinophils in vivo and are ingested by the attracted granulocytes. Infect Immun. 1991 Sep;59(9):3009–3014. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3009-3014.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayston J. T., Wang S. P., Yeh L. J., Kuo C. C. Importance of reinfection in the pathogenesis of trachoma. Rev Infect Dis. 1985 Nov-Dec;7(6):717–725. doi: 10.1093/clinids/7.6.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinzel F. P., Sadick M. D., Holaday B. J., Coffman R. L., Locksley R. M. Reciprocal expression of interferon gamma or interleukin 4 during the resolution or progression of murine leishmaniasis. Evidence for expansion of distinct helper T cell subsets. J Exp Med. 1989 Jan 1;169(1):59–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito J. I., Jr, Harrison H. R., Alexander E. R., Billings L. J. Establishment of genital tract infection in the CF-1 mouse by intravaginal inoculation of a human oculogenital isolate of Chlamydia trachomatis. J Infect Dis. 1984 Oct;150(4):577–582. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.4.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimpen J. L., Garofalo R., Welliver R. C., Ogra P. L. Activation of human eosinophils in vitro by respiratory syncytial virus. Pediatr Res. 1992 Aug;32(2):160–164. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199208000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo C., Wang S., Wentworth B. B., Grayston J. T. Primary isolation of TRIC organisms in HeLa 229 cells treated with DEAE-dextran. J Infect Dis. 1972 Jun;125(6):665–668. doi: 10.1093/infdis/125.6.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Scolea L. J., Jr, Paroski J. S., Burzynski L., Faden H. S. Chlamydia trachomatis infection in infants delivered by cesarean section. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1984 Feb;23(2):118–120. doi: 10.1177/000992288402300213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landers D. V., Erlich K., Sung M., Schachter J. Role of L3T4-bearing T-cell populations in experimental murine chlamydial salpingitis. Infect Immun. 1991 Oct;59(10):3774–3777. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.10.3774-3777.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott M. R., Clark D. A., Bienenstock J. Evidence for a common mucosal immunologic system. II. Influence of the estrous cycle on B immunoblast migration into genital and intestinal tissues. J Immunol. 1980 Jun;124(6):2536–2539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison R. P., Lyng K., Caldwell H. D. Chlamydial disease pathogenesis. Ocular hypersensitivity elicited by a genus-specific 57-kD protein. J Exp Med. 1989 Mar 1;169(3):663–675. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.3.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton D. L., Kuo C. C. Histopathology of Chlamydia trachomatis salpingitis after primary and repeated reinfections in the monkey subcutaneous pocket model. J Reprod Fertil. 1989 Mar;85(2):647–656. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0850647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton D. L., Kuo C. C., Wang S. P., Halbert S. A. Distal tubal obstruction induced by repeated Chlamydia trachomatis salpingeal infections in pig-tailed macaques. J Infect Dis. 1987 Jun;155(6):1292–1299. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.6.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton D. L., Moore D. E., Spadoni L. R., Soules M. R., Halbert S. A., Wang S. P. A comparison of the fallopian tube's response to overt and silent salpingitis. Obstet Gynecol. 1989 Apr;73(4):622–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey K. H., Newhall W. J., 5th, Rank R. G. Humoral immune response to chlamydial genital infection of mice with the agent of mouse pneumonitis. Infect Immun. 1989 Aug;57(8):2441–2446. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.8.2441-2446.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey K. H., Soderberg L. S., Rank R. G. Resolution of chlamydial genital infection in B-cell-deficient mice and immunity to reinfection. Infect Immun. 1988 May;56(5):1320–1325. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.5.1320-1325.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripa K. T., Mårdh P. A. Cultivation of Chlamydia trachomatis in cycloheximide-treated mccoy cells. J Clin Microbiol. 1977 Oct;6(4):328–331. doi: 10.1128/jcm.6.4.328-331.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter J., Hanna L., Hill E. C., Massad S., Sheppard C. W., Conte J. E., Jr, Cohen S. N., Meyer K. F. Are chlamydial infections the most prevalent venereal disease? JAMA. 1975 Mar 24;231(12):1252–1255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern J. E., Wira C. R. Progesterone regulation of secretory component (SC): uterine SC response in organ culture following in vivo hormone treatment. J Steroid Biochem. 1988;30(1-6):233–237. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(88)90098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan D. A., Underdown B. J., Wira C. R. Steroid hormone regulation of free secretory component in the rat uterus. Immunology. 1983 Jun;49(2):379–386. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan D. A., Wira C. R. Hormonal regulation of immunoglobulins in the rat uterus: uterine response to a single estradiol treatment. Endocrinology. 1983 Jan;112(1):260–268. doi: 10.1210/endo-112-1-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor H. R., Johnson S. L., Schachter J., Caldwell H. D., Prendergast R. A. Pathogenesis of trachoma: the stimulus for inflammation. J Immunol. 1987 May 1;138(9):3023–3027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. P., Grayston J. T. Pannus with experimental trachoma and inclusion conjunctivitis agent infection of Taiwan monkeys. Am J Ophthalmol. 1967 May;63(5 Suppl):1133–1145. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(67)94095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller P. F. The immunobiology of eosinophils. N Engl J Med. 1991 Apr 18;324(16):1110–1118. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199104183241607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. M., Schachter J., Drutz D. J., Sumaya C. V. Pneumonia due to Chlamydia trachomatis in the immunocompromised (nude) mouse. J Infect Dis. 1981 Feb;143(2):238–241. doi: 10.1093/infdis/143.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wira C. R., Hyde E., Sandoe C. P., Sullivan D., Spencer S. Cellular aspects of the rat uterine IgA response to estradiol and progesterone. J Steroid Biochem. 1980 Jan;12:451–459. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(80)90306-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wira C. R., Sullivan D. A. Estradiol and progesterone regulation of immunoglobulin A and G and secretory component in cervicovaginal secretions of the rat. Biol Reprod. 1985 Feb;32(1):90–95. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod32.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolridge R. L., Grayston J. T., Chang I. H., Cheng K. H., Yang C. Y., Neave C. Field trial of a monovalent and of a bivalent mineral oil adjuvant trachoma vaccine in Taiwan school children. Am J Ophthalmol. 1967 May;63(5 Suppl):1645–1650. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(67)94158-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Asrar A. M., Van den Oord J. J., Geboes K., Missotten L., Emarah M. H., Desmet V. Immunopathology of trachomatous conjunctivitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989 Apr;73(4):276–282. doi: 10.1136/bjo.73.4.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]