Abstract

N-Acylethanolamines (NAEs) are members of the fatty acid amide family. The NAEs have been proposed to serve as metabolic precursors to N-acylglycines (NAGs). The sequential oxidation of the NAEs by an alcohol dehydrogenase and an aldehyde dehydrogenase would yield the N-acylglycinals and/or the NAGs. Alcohol dehydrogenase 3 (ADH3) is one enzyme that might catalyze this reaction. To define a potential role for ADH3 in NAE catabolism, we synthesized a set of NAEs and evaluated these as ADH3 substrates. NAEs were oxidized by ADH3, yielding the N-acylglycinals as the product. The (V/K)app values for the NAEs included here were low relative to cinnamyl alcohol. Our data show that the NAEs can serve as alcohol dehydrogenase substrates.

Keywords: Alcohol dehydrogenase 3, N-acylethanolamine oxidation, N-acylglycinal, N-fatty acylglycine

Introduction

The fatty acid amide bond has long been recognized in nature, dating back decades to the work defining the structure of the ceramides and sphingolipids [1,2]. N-Palmitoylethanolamine, CH3-(CH2)14-CO-NH-CH2-CH2-OH, was the first non-sphingosine fatty acid amide isolated from a biological source, egg yolk in 1957 [3]. Interest in the fatty acid amides burgeoned with the identification of N-arachidonoylethanolamine (anandamide) as the endogenous ligand for the cannabinoid receptors, CB1 and CB2, in the brain [4]. We now know that a family of N-acylethanolamines, in addition to anandamide and N-palmitoylethanolamine, is found in the brain and other tissues. Most of the N-acylethanolamines (NAEs) seem to play important signaling roles in mammals [5–7].

We have proposed that two classes of fatty acid amides are linked in a biosynthetic pathway, the N-fatty acylglycines and the PFAMs [8,9]. Oxidative cleavage of the N-fatty acylglycines at the Cα-N bond of the glycyl residue would yield the corresponding PFAM and glyoxylate. In vitro studies have shown that this reaction is catalyzed by peptidylglycine αamidating monooxygenase, (PAM, EC 1.14.17.3) with VMAX/KM values comparable to the peptide precursor substrates [10]. In addition, elimination of PAM activity in mouse neuroblastoma N18TG2 cells resulted in the accumulation of N-oleoyglycine when these cells were grown in the presence of oleic acid [9]. Previously, Bisogno et al. [11] had shown that N18TG2 cells cultured in the presence of [1-14C]-oleic acid secreted [1-14C]-oleamide indicating that these cells must contain the enzymatic machinery required for oleamide biosynthesis. While our data support the hypothesis that the N-fatty acylglycines are biosynthetic precursors for the PFAMs, other possible pathways for the in vivo production of the PFAMs have been suggested, most notably the nucleophilic attack of fatty acyl-CoA thioesters by ammonia as catalyzed by cytochrome c [12]: CoA-S-CO-R + NH3 → R-CO-NH2 + CoA-SH.

Short-chain N-acylglycines like N-butyrylglycine, N-isovaleroylglycine, and N-hexanoylglycine, are mammalian metabolites [13–15]. Trace levels of longer-chain N-acylglycines, N-octanoylglycine and N-decanoylglycine, are known only from patients with a deficiency in medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase [16,17]. Longer-chain N-fatty acylglycines were unknown in mammals until our identification of N-oleoylglycine from N18TG2 cells grown in the presence of a PAM inhibitor [9]. Since our discovery of N-oleoylglycine, there have been other reports of mammalian N-fatty acylglycines: N-arachidonoylglycine, N-linoleoylglycine, N-palmitoylglycine, N-stearoylglycine, and N-docosahexaenoylglycine [18–20]. Bradshaw et al. [20] also isolated N-oleoylglycine from mice, consistent with our earlier work. The known N-fatty acylglycines are widely distributed throughout the body with the highest levels being found in the skin, lung, spinal cord, liver, and kidney [19,20].

The identification of mammalian N-fatty acylglycines leads to the question regarding the pathway(s) for their biosynthesis. One possible pathway involves the conjugation of glycine to the fatty acid via nucleophilic attack of the glycyl α-amino group at the carboxylate of the fatty acid. Huang et al. [18] and Bradshaw et al. [21] demonstrate that this reaction does take place in the cell; however, the details of the chemistry are undetermined. It seems unlikely the glycine would be directly conjugated to a fatty acid, but instead would involve nucleophilic attack of an activated fatty acid, an acyl-CoA thioester being an obvious possibility. Acyl-CoA:glycine N-acyltransferase (ACGNAT or GLYATL) [22,23], bile acid-CoA:amino acid N-acyltransferase (BAAT) [24], and cytochrome c [25] are all enzymes which catalyze glycine conjugation to an acyl-CoA. For each enzyme, there are in vitro studies suggesting that each could produce N-fatty acylglycines from the corresponding N-fatty acyl-CoA and glycine, but data conclusively validating their role in N-fatty acylglycine biosynthesis in vivo are currently lacking. Other possible activated fatty acids for attack by glycine could be a fatty acid adenylate similar to the amino acid adenylates involved in charging tRNAs or in the biosynthesis of mycothiol or a fatty acid thioester linked to a cysteine in a carrier protein, similar to intermediates observed in fatty acid biosynthesis. Alternatively, the N-fatty acylglycines might be produced by a novel N-acylglycine synthase via the initial formation of an acyl-enzyme intermediate which is subsequently attacked by a bound glycine. Such a novel N-acylglycine synthase is consistent with data from Huang et al. [18] and Bradshaw et al. [21] showing that fatty acids are directly conjugated to glycine and could enable a decrease in the pKa of the glycyl α-amino group in the enzyme active site to increase the nucleophilicity of this moiety. Amino acid promiscuity by a novel N-acylglycine synthase might account for the plethora of N-fatty acylamino acids recently identified in mammalian brain by Tan et al. [26].

Another suggested pathway for the biosynthesis of the N-fatty acylglycines is the sequential oxidation of the NAEs by a fatty alcohol dehydrogenase and fatty aldehyde dehydrogenase [27]. The first evidence for this pathway to the N-fatty acylglycines was presented by Burstein et al. [28] showing that anandamide was converted to N-arachidonylglycine in cultured liver cells. More recent work by Bradshaw et al. [21] in RAW 264.7 and C6 glioma cells again showed that anandamide is oxidized to N-arachidonoylglycine. Finally, Aneetha et al. [27] found that purified human alcohol dehydrogenase 7, hADH7, catalyzed the NAD+-dependent oxidation of ananadamide in vitro and will dismutate the intermediate N-arachidonoylglycinal to N-arachidonoylglycine. These data all strongly suggest that the NAEs can serve as precursors to the N-fatty acylglycines. Intriguingly, data from Bradshaw et al. [21] show that N-arachidonoylglycine is produced by both anandamide oxidation and glycine conjugation to arachidonic acid in cultured mammalian cells.

We report here, for the first time, that a series of NAEs are substrates for alcohol dehydrogenase 3 from bovine liver (ADH3). Alcohol dehydrogenase 3 enzymes are found in virtually all eukaryotes and prokaryotes and represent the ancestral enzyme from which all the other medium-chain ADHs originated [29]. NAEs from N-acetylethanolamine to anandamide are oxidized by ADH3 with a general trend of the longer chain NAEs exhibiting the highest V/K values. N-Benzoylethanolamine and other N-arylacylethanolamines are also ADH3 substrates with N-(tBOC)-ethanolamine having the highest V/K value from this class of novel ADH3 substrates. ADH3-mediated oxidation of the NAEs results in the formation of the corresponding N-fatty acylglycinals showing that ADH3 does not catalyze the dismutation of the acylglycinals to the N-fatty acylglycine and NAE.

Materials and Methods

Enzyme Purification

Bovine liver ADH3 was purified following a procedure modified from Pourmotabbed and Creighton [30]: ammonium sulfate precipitation (45–67%), DEAE cellulose chromatography, Mimetic Blue II chromatography, and blue dextran agarose chromatography. The Mimetic Blue II column replaced the NAD+-agarose chromatography in the published procedure from Pourmotabbed and Creighton [30]. Dialyzed sample containing partially purified ADH3 from the DEAE cellulose column was loaded onto a Mimetic Blue II affinity column (1.5 × 20 cm) that was previously equilibrated with 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 and 2 mM DTT. The column was washed with the same buffer and flow rate was adjusted to 1 ml/min. Protein content of fractions was monitored by measuring absorbance at 280 nm. Once the A280 was below 0.2, a linear gradient of 0–20 mM NAD+ (total volume 200 ml) was applied to the column in order to elute ADH3.

Fractions (4.0 mL) were assayed for ADH3 activity by measuring NADH production spectrophotometrically at 340 nm, using cinnamyl alcohol as the substrate. Assays were carried out in 100 mM glycine-NaOH pH 10.0, 5.0 mM cinnamyl alcohol, and 2.5 mM NAD+ at 37 °C. Note that 1 unit of ADH3 activity corresponds to 1 μmole of NADH produced/min under these conditions. NADH production was followed at 340 nm using a JASCO V-530 UV-Vis spectrophotometer. Crude enzyme fractions are known to contain ADH1 and ADH2 and were, thus, evaluated in presence of 3.0 mM pyrazole, a known inhibitor ADH1/ADH2 [31]. In addition to this, rates for controls without cinnamyl alcohol were subtracted from those obtained in the presence of substrate to eliminate false positives.

Fractions with the highest specific activity were analyzed for purity using SDS-PAGE, and those containing only a single protein band corresponding to the weight of an ADH3 subunit (~40 kDa) were pooled together. Protein concentration of purified ADH3 was determined using the Bradford dye binding assay [32] and the concentrated enzyme (6.5 mg/mL) was stored at −80 °C.

Synthesis of the NAEs

A number of N-acylethanolamines were available commercially in high purity and these were obtained and used without further purification. N-Arachidonoylethanolamine and N-linoleoylethanolamine were purchased from Cayman Chemical Company, N-acetylethanolamine was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, and N-propionylethanolamine was purchased from TCI.

The remaining N-acylethanolamines included here were synthesized by the addition of ethanolamine to the acid chloride as described [33,34]. [1,2-13C]-N-Octanoylethanolamine, CH3-(CH2)6-CO-NH-13CH2-13CH2-OH, was prepared similarly except that commercially available [1,2-13C]-ethanolmine-HCl was first neutralized with a 10-fold molar excess of triethylamine before the addition of octanoyl chloride. Purity and identity of synthesized NAEs were confirmed by 1H and 13C NMR using a Varian iNOVA 400 MHz NMR. The acid chlorides, ethanolamine, and [1,2-13C]-ethanolamine-HCl were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and were used without further purification. Anhydrous CH2Cl2 was purchased from EMD.

Synthesis of the N-Acylglycinals

N-Benzoylglycinal and N-octanoylglycinal were prepared using a procedure slightly modified from Brown [35]. N-Acylglycinal diethyl acetals were prepared by reacting aminoacetaldehyde diethyl acetal with the corresponding acyl chlorides under basic conditions. N-Benzoylglycinal and N-octanoylglycinal were obtained by acid-catalyzed deprotection of the corresponding N-acylglycinal diethyl acetals. The purity and identity of the N-acylglycinal diethyl acetal intermediates and the desired N-acylglycinals were confirmed by 1H and 13C NMR spectra obtained on Varian iNova 400 MHz.

Spectrophotometric Assay for the Production of NADH

Kinetic constants for short- and medium-chain NAEs were determined from initial reaction rates obtained by following NAD+ reduction to NADH as the increase in absorbance at 340 nm (Δε340 = 6.22 × 103 M−1 cm−1) using a JASCO V-530 UV-Vis spectrophotometer. Reaction conditions were as follows: 100 mM glycine-NaOH pH 10, 2.5 mM NAD+, and 15–30 μg/ml ADH3 in 1.0 ml total reaction volume. NAE concentrations were between 0.1KM and 10KM, and all assays were conducted at 37 °C. Glycine was purchased from J.T. Baker, NAD+ was acquired from BioWorld, and cinnamyl alcohol and 1-octanol were from Sigma-Aldrich. All were used without further purification. Rates were normalized using rate for 250 μM cinnamyl alcohol as the standard.

MTS-Formazan Assay for the Production of NADH

Due to the low solubility of long-chain NAEs, a complete range of kinetic assays at high [NAE] to determine steady-state kinetic parameters (KM and VMAX) could not be performed. As the compounds could only be assayed at relatively low concentrations (<100 μM), the rates of NADH production were very low and could not be confidently determined spectrophotometrically. Instead, a more sensitive method for NADH detection was employed, coupling the NADH production to the reduction of a tetrazolium dye MTS ([3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt) to the colored formazan with λmax at 490 nm and ε = 20,800 M−1 cm−1 at pH 9.5 [36]. Phenazinemethosulfate (PMS) was used as an intermediate electron carrier.

NAEs with 10 or more carbon atoms in the acyl chain were all assayed for ADH3 activity at the same concentration employing the MTS-formazan assay. The assay conditions were as follows: 100 mM sodium pyrophosphate pH 9.5, 55 μM NAE, 2.5 mM NAD+, 150 μM MTS, 8.25 μM PMS, 3.0% (v/v) DMSO and 30 μg/ml ADH3. Decanoyl and lauroylethanolamine were soluble enough to allow the determination of KM and VMAX values as well. All reactions were done at 37 °C and the initial rates were determined by observing the increase in absorbance at 490 nm using a JASCO V-530 UV-Vis spectrophotometer. Sodium pyrophosphate was obtained from Fisher, MTS was purchased from Promega, and PMS was obtained from TCI America. Rates for cinnamyl alcohol obtained in this manner matched the rates obtained by following NADH production at 340 nm. Rates were normalized against the rate obtained for 250 μM cinnamyl alcohol as a standard.

Molecular Modeling

The crystal structure of human ADH3 (PDB ID 1MP0) [37] was used for grid-based ligand docking. All co-crystallized ligands deemed superfluous for enzyme function were removed from the crystal structure and polar hydrogen atoms were added using AutoDockTools. Charges were then corrected for the requisite zinc ions and bond orders corrected for the co-substrate, NAD+. The receptor grid was prepared with a grid point spacing of 0.2 Å using AutoGrid. The substrates of interest were then prepared using AutoDockTools to define torsions, rotamers, and polar hydrogen atoms. The ligands were then docked into the active site of ADH using AutoDock 4.0 [38,39]. All default settings were utilized with the exception of increasing the number of energy evaluations from 2.5 × 104 to 2.5 × 107.

Product Characterization by HPLC

Separations were performed on an Agilent HP 1100, equipped with a 4-channel solvent mixing system, a quaternary pump, and a variable wavelength UV detector and were accomplished using a Thermo-Scientific C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm) with the temperature fixed at 40 °C. N-Benzoylethanolamine, N-benzoylglycinal, and N-benzoylglycine (hippurate) were separated using either a gradient of 50 mM sodium phosphate pH 6.0:CH3CN from 90:10 (v/v) to 95:5 (v/v) over 20 minutes, or isocratic mobile phase of 50 mM sodium phosphate pH 6.0:CH3CN (90:10 v/v) and the analytes were detected by monitoring the UV absorbance at 230 nm.

Cinnamyl alcohol, cinnamyl aldehyde, and cinnamic acid were separated using a linear gradient of 50 mM sodium phosphate pH 6.0:CH3CN from 75:25 (v/v) to 40:60 (v/v) over 15 minutes and the analytes were detected by monitoring the UV absorbance at 265 nm.

N-Benzoylethanolamine and N-benzoylglycinalsemicarbazone were separated using a linear gradient of H2O:CH3CN from 70:30 (v/v) to 40:60 (v/v) over 20 minutes and the analytes were detected by monitoring the UV absorbance at 210 nm.

Analysis by GC-MS

GC-MS analyses were performed using a Shimadzu QP5000 GC-MS equipped with a DB-5 (0.25 μm × 0.25 mm × 30 m) column. Compounds were extracted from reaction mixture using either ethyl ether (cinnamyl alcohol and cinnamyl aldehyde) or CH2Cl2 (N-benzoylethanolamine, N-benzoylglycinal, and N-benzoylglycine). Aldehyde derivatization to PFB-oximes was done by dissolving the extracted and dried residue into 90 μl of CH3CN, adding 10 μl of 100 mM PFBHA (O-(2,3,4,5,6-pentafluorobenzyl)hydroxylamine), and heating the solution at 60 °C for 60 minutes.

N-Benzoylglycine derivatization was done by dissolving the extracted and dried material in 100 μl of BSTFA (N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide), purging the solution with N2, and heating the mixture for 15–20 minutes at 90 °C. Derivatized samples (5–10 μl) were injected into the GC-MS in a splitless manner, with injection temperature at 250 °C. The temperature program was modified adapted from Merkler et al. [9]. Oven temperature was raised from 55 °C to 150 °C, at a rate of 40 °C/min, held at 150 °C for 3.6 min, then raised to 300 °C at a rate of 10.0 °C/min, and finally held at 300 °C for 1.0 min. Interface temperature between GC and MS was 280 °C, and solvent cut time was 7–9 min. Peak identity was established by comparison of retention times and mass spectra with those of derivatized standards and library spectra.

Trapping of the N-Acylglycinals with Semicarbazide

In order to characterize the N-acylglycinal reaction products, which are unstable at the reaction pH, semicarbazide was employed as an aldehyde-trapping reagent. Semicarbazide was added in large excess (9–10 × substrate concentration) to the reaction mix containing 100 mM sodium pyrophosphate pH 9.5, 3–5 mM N-benzoylethanolamine, 2.5 mM NAD+, and 0.25–1.0 mg/ml ADH3. Formation of N-benzoylglycinal semicarbazone was followed by HPLC.

N-Acylglycinal Semicarbazone Characterization by 13C NMR

N-Octanoylglycinal semicarbazone was characterized by following the enzymatic oxidation of [1,2-13C]-N-octanoylethanolamine in the presence of semicarbazide by 13C NMR. The presence of N-octanoylglycinal semicarbazone was established by observing the reduction in intensity of the 13C labeled signals in the substrate and the appearance of two 13C carbon signals consistent with those of N-octanoylglycinal semicarbazone. Peak identity was confirmed by comparison with 13C spectrum of synthesized N-octanoylglycinal semicarbazone. Reaction conditions were as follows: 50 mM sodium pyrophosphate pH 8.0, 2.5 mM [1,2-13C]-N-octanoylethanolamine, 2.5 mM NAD+, 20 mM semicarbazide-HCl, 10% (v/v) D2O, and 1.7 mg/ml ADH3. Reaction mix was incubated at 37 °C, and 13C NMR spectra were taken after 24 hour and 48 hr reaction time points. Control samples containing all the reagents except for the enzyme were handled and analyzed in the same manner. 13C NMR Spectra were collected using a Varian iNova 400 MHz instrument.

Results and Discussion

ADH3 Purification

ADH3 was purified from bovine liver to ~90 % homogeneity and exhibited specific activity of 0.53 U/mg. Molecular weight of ADH3 subunits, calculated based on the Rf values determined from the SDS-PAGE was 38 kDa, which is in good agreement with previously determined values of 40-41 kDa [40].

Kinetics of ADH3-catalyzed NAE Oxidation

A variety of aliphatic NAEs with acyl chain lengths varying from 2 to 20 carbons, as well as several aromatic NAEs were evaluated as substrates for ADH3. All of the tested NAEs were found to be substrates for ADH3, with KM values decreasing with increase in chain length of the acyl substituent (Table 1). This indicates that increase in substrate size leads to tighter binding to the enzyme, or rather that small size impairs the ability to bind to the site tightly, which is in agreement with known substrate preferences of ADH3 [41]. The values measured for the VMAX followed the same trend, decreasing with increase in substrate size and hydrophobicity. However, decrease in KM values were more pronounced, resulting in overall increase in VMAX/KM values with increase in length of the acyl chain length for the NAE substrates (Table 1). While ADH3 could catalyze the oxidation of all tested NAEs, their turnover values were low compared to cinnamyl alcohol, an ADH3 substrate with a relatively high VMAX/KM value. Also included in Table 1 are the steady-state kinetic values for the ADH3 mediated oxidation of 1-octanol. 1-Octanol is a substrate used in the study of many alcohol dehydrogenases and, thus, facilitaties the comparison of the NAE kinetic data included here to earlier work.

Table 1.

Kinetic Constants for the ADH3-Mediated Oxidation of NAE Substrates with Acyl Chains Containing 2-12 Carbon Atoms.

| Substrate |  |

KM (mM) | VMAX (μmol/min/mg) | VMAX/KM (sec−1 M−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-Acetylethanolamine | R = CH3 | (4.5 ± 0.4) × 102 | 1.9 ± 0.059 | 2.7 |

| N-Propionylethanolamine | R = CH3CH2 | 79 ± 3.8 | 1.9 ± 0.026 | 15 |

| N-Butyrylethanolamine | R = CH3(CH2)2 | 46 ± 5.4 | 1.7 ± 0.052 | 23 |

| N-Hexanoylethanolamine | R = CH3(CH2)4 | 9.5 ± 0.36 | 1.6 ± 0.018 | 110 |

| N-Octanoylethanolamine | R = CH3(CH2)6 | 5.8 ± 0.38 | 1.5 ± 0.028 | 160 |

| N-Decanoylethanolamine | R = CH3(CH2)8 | 0.32 ± 0.029 | 0.57 ± 0.024 | 1.1 × 103 |

| N-Lauroylethanolamine | R = CH3(CH2)10 | 0.033 ± 0.0061 | 0.14 ± 0.0088 | 2.7 × 103 |

| 1-Octanol | CH3-(CH2)6-CH2-OH | 0.050 ± 0.0130 | 2.5 ± 0.16 | 3.2 × 104 |

| Cinnamyl alcohol | C6H6HC=CHCH2OH | 0.035 ± 0.0033 | 4.0 ± 0.058 | 7.2 × 104 |

Kinetic parameters, KM and VMAX/KM, could not be determined for NAE substrates with acyl chains longer than 12-carbon atoms (longer than N-lauroylethanolamine) due to low solubility and low reaction rates. A comparison of initial rates between two medium-chain (N-decanoyl- and N-lauroylethanolamine) and several long-chain NAEs at a single substrate concentration is shown in Table S1 (Supplementary material). The initial rates of Table S1 follow the general trend observed with short- and medium-chain NAEs as the rates decrease with the increasing length of the acyl chain (see Table 1).

The data in Tables 1 and S1 were generated with NAEs comprised only of straight-chain saturated or unsaturated acyl chains. We also found that NAEs containing a terminal benzene ring were ADH3 substrates (Table 2). The VMAX/KM values obtained for the NAE substrates of this class included here are low relative to cinnamyl alcohol and are of the same magnitude determined for the aliphatic acyl chain NAEs with acyl chain lengths of 4–8 carbons (compare Table 2 to Table 1).

Table 2.

Kinetic Constants for the ADH3-Mediated Oxidation of NAE Substrates with Acyl Chains Containing an Benzyl Ring.

| Substrate |  |

KM (mM) | VMax (μmol/min/mg) | VMax/KM (sec−1 M−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-Benzoylethanolamine | R = C6H6 | 5.2 ± 0.52 | 0.36 ± 0.0098 | 44 |

| N-Phenylacetylethanolamine | R = C6H5CH2 | 3.9 ± 0.24 | 1.2 ± 0.026 | 200 |

| N-Benzyloxycarbonylethanolamine | R = C6H5CH2O | 2.3 ± 0.14 | 0.81 ± 0.014 | 220 |

| N-(2-Phenoxyacetyl)ethanolamine | R = C6H5OCH2 | 6.3 ± 0.36 | 0.25 ± 0.0042 | 25 |

| Cinnamyl alcohol | C6 H6HC=CHCH2 | 0.035 ± 0.0033 | 4.0 ± 0.058 | 7.2 × 104 |

Molecular Modeling of ADH3-NAE Binding

NAE substrates with straight-chain, saturated acyl chains between 2 and 11 carbon atoms were docked into the human ADH3 crystal structure using AutoDock 4.0 in order to evaluate their relative binding energies. Sequence alignment of human and bovine ADH3 using BLAST [42] shows that they share 94% identity, with 98% of residues conserved, suggesting that the docking results obtained with the human enzyme are applicable to bovine ADH3 as well. Relative binding energies of docked NAEs were found to follow the same general trend as KM values, decreasing with increase in chain length (Table 3), indicating that tighter binding to the enzyme is at least partly responsible for the observed KM trend. Substrates were docked in the enzyme active site with hydroxyl group coordinating with the catalytic Zn(II), in the same manner as other ADH3 substrates have been shown to bind [40,43].

Table 3.

Comparison of the KM Values to the Calculated Free Energy of Binding for Selected NAEs and Cinnamyl Alcohol.

| Substrate | KM (mM) | Calculated Free Energy of Bindinga (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| N-Acetylethanolamine | (4.5 ± 0.4) × 102 | −3.72 |

| N-Propionylethanolamine | 79 ± 3.8 | −4.14 |

| N-Butyrlethanolamine | 46 ± 5.4 | −4.22 |

| N-Hexanoylethanolamine | 9.5 ± 0.36 | −4.34 |

| N-Octanoylethanolamine | 5.8 ± 0.38 | −4.31 |

| N-Decanoylethanolamine | 0.32 ± 0.029 | −4.34 |

| N-Lauroylethanolamine | 0.033 ± 0.0061 | −4.06 |

| N-Benzoylethanolamine | 5.2 ± 0.52 | −4.58 |

| Cinnamyl alcohol | 0.035 ± 0.0033 | −4.68 |

Binding energies values were calculated using Autodock 4.0, and have a standard error of about ± 2.5 kcal/mol [39].

HPLC Analysis of the ADH3-Mediated Oxidation of the NAEs

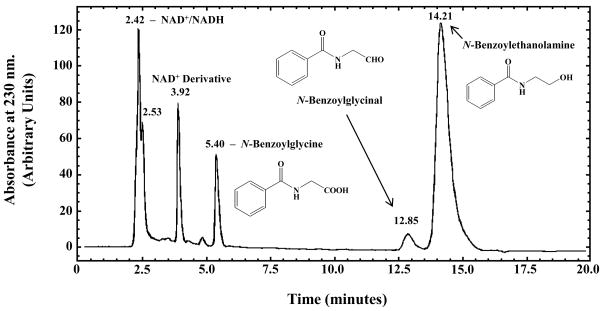

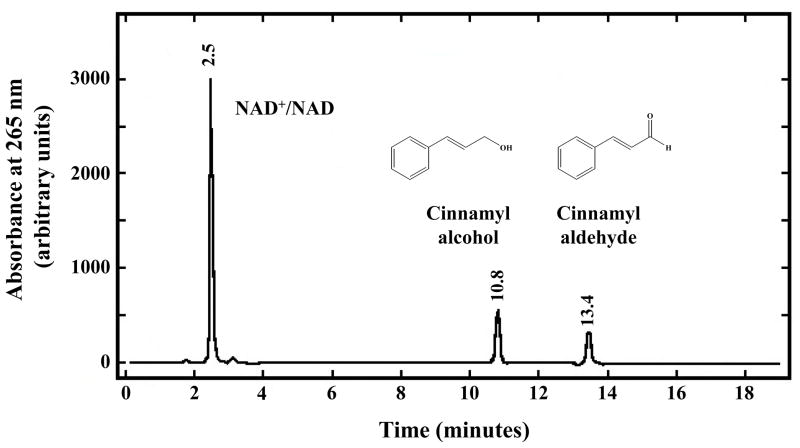

HPLC analysis of the ADH3-catalyzed oxidation of N-benzoylethanolamine revealed the presence of peaks with retention times consistent with N-benzoylglycine and N-benzoylglycinal (Fig. 1). N-Benzoylglycine and N-benzoylglycinal are the two possible products of the enzymatic oxidation of N-benzoylethanolamine. However, Svensson et al. [44] found that ADH3 does not catalyze aldehyde dismutation suggesting that N-benzoylglycinal should be produced upon the ADH3-mediated oxidation of N-benzoylethanolamine. Incubation of N-benzoylglycinal under the conditions used for ADH3 catalyzed reactions (2.5 mM NAD+, pH 9.5–10) in the absence of ADH3 showed low rates of non-enzymatic aldehyde dismutation to N-benzoylglycine and N-benzoylethanolamine (data not shown). Incubation of ADH3 with N-benzoylglycinal under identical conditions does not significantly increase the rate of aldehyde dismutation (Supplementary material, Fig. S1). HPLC analysis of ADH3-catalyzed oxidation of cinnamyl alcohol, a substrate with a VMAX/KM that is ~1600 higher than that of N-benzoylethanolamine, yields only a peak with a retention time consistent with cinnamyl aldehyde (Fig. 2). These data further suggest that the ADH3-catalyzed products of NAE oxidation are the N-acylglycinals, and that the observed N-acylglycines are produced via slow non-enzymatic aldehyde dismutation.

Figure 1. HPLC Analysis of the ADH3-catalyzed Oxidation of N-Benzoylethanolamine.

Reaction conditions were as follows: 100 mM sodium pyrophosphate pH 9.5, 2.5 mM NAD+, 6.0 mM N-benzoylethanolamine, and 2.4 mg/ml ADH3. HPLC analysis was performed after 36 hr of reaction time. The peak with a retention time of 3.918 min was derived from NAD+ that formed during prolonged incubation at high pH. A peak with the same retention time was also observed in the control sample containing only NAD+ and buffer.

Figure 2. HPLC Analysis of the ADH3-catalyzed Oxidation of Cinnamyl Alcohol.

Reaction conditions were as follows: 100 mM sodium pyrophosphate pH 9.5, 2.5 mM NAD+, 1.75 mM cinnamyl alcohol, and 5.0 μg/ml ADH3. HPLC analysis was performed after 45 min of reaction time.

GC-MS Characterization of the Products Generated by ADH3

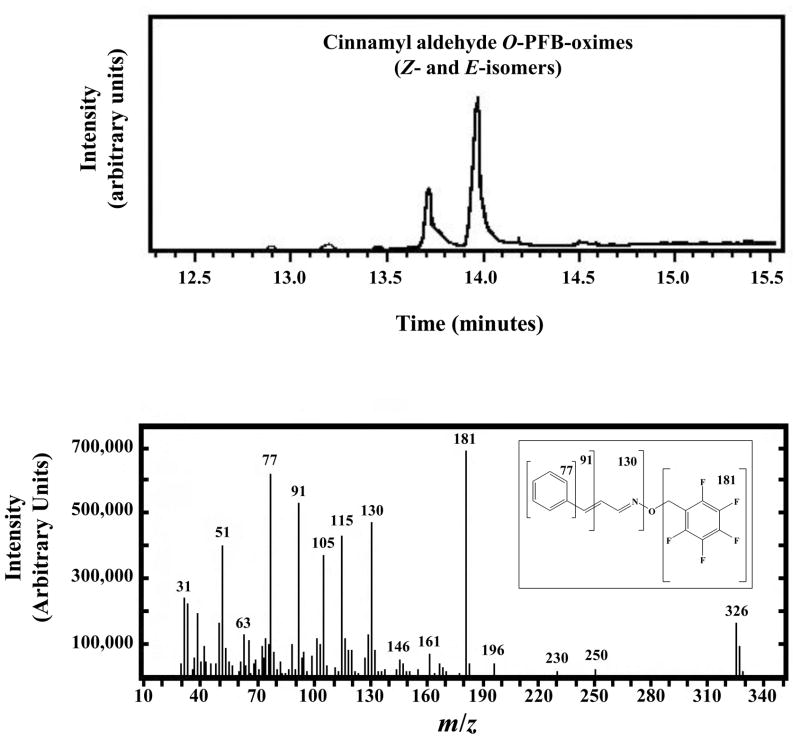

Our HPLC results strongly suggest that products of the ADH3-mediated oxidation of the NAEs are the corresponding N-acylglycinals. However, comparison of HPLC retention times is not definitive as there is always that possibility that another compound has a similar retention time. We used GC-MS to further characterize the products generated from the NAEs by ADH3. In order to test the validity of this approach, we first used GC-MS to characterize the cinnamyl alcohol reaction product. Derivatization of cinnamyl alcohol reaction extract with PFBHA gave two peaks detected by GC-MS, whose retention times and fragmentation patterns were consistent with those for two isomers of cinnamyl aldehyde PFB-oxime (Fig. 3), confirming that the reaction product is cinnamyl aldehyde. However, applying the same method to characterize N-benzoylglycinal observed by HPLC proved unsuccessful. Although the derivatized standard for N-benzoylglycinal-PFB-oxime was successfully characterized using GC-MS, this compound could not be detected by GC-MS in the reaction extracts. This can be attributed to the very low turnover rates of N-benzoylethanolamine oxidation compared to cinnamyl alcohol oxidation (Table 2), as well as to the tendency of N-benzoylglycinal to undergo non-enzymatic oxidation to N-benzoylglycine under the reaction conditions. Derivatization of the N-benzoylethanolamine reaction extract with BSTFA resulted in detection of N,O-di-TMS-N-benzoylglycine, confirming that the peak observed by HPLC is N-benzoylglycine.

Figure 3. GC-MS Analysis of the ADH3-generated Cinnamyl Aldehyde.

Cinnamyl aldehyde was first generated enzymatically by treating cinnamyl alcohol with ADH3 as described in the legend to Figure 2. Cinnamyl aldehyde was converted to the perfluorobenzyl oxime (O-PFB-oxime) with PFBHA and analyzed by GC-MS. The resulting cinnamyl aldehyde O-PFB-oxime exists as the E- and Z-isomers, which have different retention times in the gas chromatograph (upper panel), but exhibit identical fragmentation patterns from the mass spectrometer (lower panel). The structure and fragmentation pattern of cinnamaldehyde O-perfluorobenzyl oxime are shown in the inset to the lower panel.

13C NMR Characterization of the Products Generated by ADH3

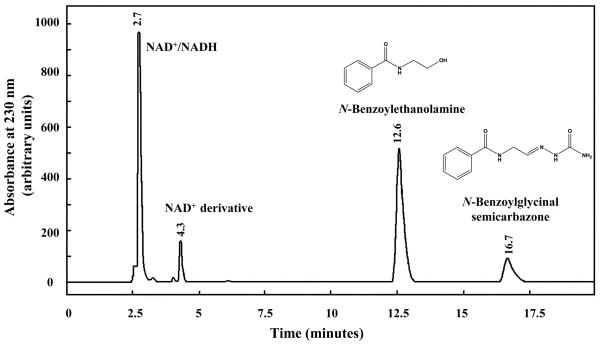

In order to detect and characterize the unstable N-acylglycinal product, a well-known aldehyde-trapping reagent, semicarbazide, was added to the reaction mixture. Semicarbazide readily reacts with aldehydes and ketones to form semicarbazones. HPLC analysis of N-benzoylethanolamine reaction containing semicarbazide revealed a peak consistent with the peak for N-benzoylglycinal semicarbazone standard (Fig. 4). Note that the peak consistent with N-benzoylglycine is not seen in the chromatogram. Further characterization of the semicarbazone derivative was attempted by LC-MS and GC-MS, but proved unsuccessful.

Figure 4. HPLC Analysis of the ADH3-catalyzed Oxidation of N-Benzoylethanolamine in the Presence of Semicarbazide.

Reaction conditions were as follows: 100 mM sodium pyrophosphate pH 9.5, 2.5 mM NAD+, 4.0 mM N-benzoylethanolamine and 0.3 mg/ml ADH3. HPLC analysis was performed after 24 hr of reaction time.

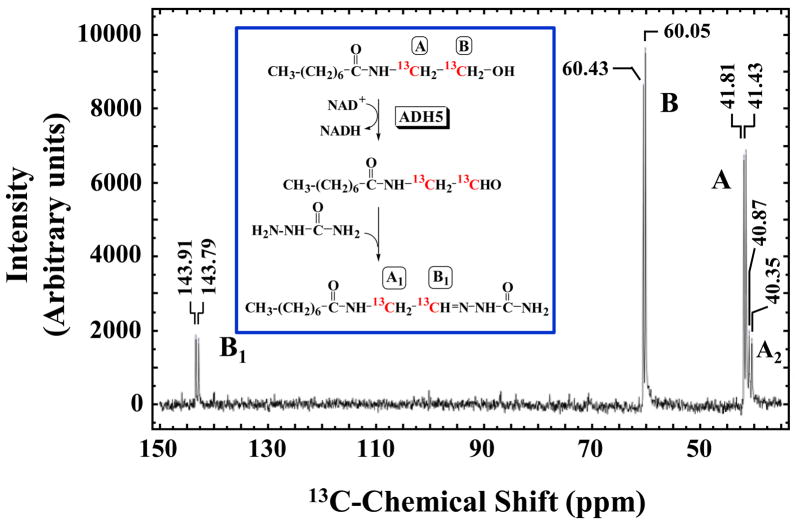

To better characterize the putative N-acylglycinal semicarbazone species detected by HPLC, the ADH3 reaction was analyzed by 13C NMR for which the substrate was [1,2-13C]-N-octanoylethanolamine. ADH3 treatment of [1,2-13C]-N-octanoylethanolamine reaction showed a total of 4 different 13C signals – two that matched those for the substrate, at 41 and 60 ppm, and two new 13C signals, at 40 and 143 ppm (Fig. 5). The chemical shifts of the two new signals match those of the corresponding carbon atoms in the N-octanoylglycinal semicarbazone standard, providing strong confirmation that the product of the ADH3 catalyzed oxidation is N-octanoylglycinal. Repeating the experiment in the absence of semicarbazide resulted in appearance of 13C signals consistent with those of N-octanoylglycine. This result was consistent with our HPLC experiments, which showed that N-benzoylglycinal is non-enzymatically oxidized to N-benzoylglycine at basic pH. Control sample with no ADH3 present showed only the two substrate peaks, confirming there was no detectable oxidation of N-octanoylethanolamine through non-enzymatic chemistry.

Figure 5. 13C-NMR Spectrum of ADH3-catalyzed Oxidation of [1,2-13C]-N-Octanoylethanolamine in the presence of Semicarbazide.

Reaction conditions were as follows: 50 mM sodium pyrophosphate pH 8.0, 2.5 mM [1,2-13C]-N-octanoylethanolamine, 2.5 mM NAD+, 20 mM semicarbazide HCl, 10% (v/v) D2O, and 1.7 mg/ml ADH3. The 13C-NMR spectrum was collected after reaction proceeded for 48 hr.

Conclusions

The data presented here demonstrate the N-fatty acylethanolamines can serve as substrates for ADH3 being oxidized to the N-fatty acylglycinals. In contrast to other alcohol dehydrogenases [44,45], ADH3 does not catalyze aldehyde dismutation and, thus, does not catalyze the conversion of N-acylglycinals and cinnamyl aldehyde to the corresponding carboxylate. This result agrees with earlier data from Svensson et al. [44] that human ADH3 does not convert butanal to butyric acid. The relatively low VMAX/KM values measured for the ADH3-catalyzed oxidation of the NAEs suggests that it is unlikely that this enzyme plays a significant role in conversion of NAEs to N-acylglycinals in vivo. Nevertheless, our findings coupled with the work of Aneetha et al. [27] showing that ADH7 is capable of catalyzing the conversion of anandamide to N-arachidonoylglycinal and N-arachidonoylglycine, validate the dehydrogenase-mediated oxidation of the NAEs is a plausible pathway to the NAGs and PFAMs in vivo. Recent work from Bradshaw et al. [21] does show that anandamide is a precursor to N-arachidonoylglycine in RAW 264.7 and C6 glioma cells. The ADH7-mediated oxidation of anandamide is relatively slow hinting that another enzyme may catalyze NAE oxidation in vivo. In this regard, further studies on ADH6 and ADH8 assessing the possibility of their involvement in NAE metabolism could be revealing, as these two alcohol dehydrogenases are poorly investigated to date. The possibility that fatty aldehyde dehydrogenases could function in the oxidation of N-fatty acylglycinals to N-fatty acylglycines also warrants further investigation.

Research Highlights.

Alcohol dehydrogenase 3 (ADH3)-mediated oxidation of the N-acylethanolamines (NAEs).

N-Acylglycinals are the products of NAE oxidation by ADH3

Structure-activity relationships for the NAE substrates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by grants from the National Institutes of Health - General Medical Sciences (R15-GM059050 and R15-GM073659), the Florida Center for Excellence for Biomolecular Identification and Targeted Therapeutics (FCoE-BITT grant no. GALS020), the Gustavus and Louise Pfieffer Research Foundation, the Eppley Foundation for Research, the Shin Foundation for Medical Research, and the Shirley W. & William L. Griffin Foundation to D.J.M., a predoctoral fellowship to E.W.L. from the American Heart Association (#0415259B), and a travel grant from the University of South Florida Student Government to M. I. The authors dedicate this work to the memory of Dr. Mitchell E. Johnson.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Thudichum JLW. A Treatise on the Chemical Constitution of the Brain. Baillière, Tindall, and Cox; London: 1884. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levene PA. Sphingomyelin. III. J Biol Chem. 1916;24:69–89. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuehl KA, Jr, Jacob TA, Ganley HO, Ormond RE, Meisinger MAP. The identification of N-(2-hydroxyethyl)-palmitamide as a naturally occurring antiinflammatory agent. J Amer Chem Soc. 1957;79:5577–5578. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmer SL, Thakur GA, Makriyannis A. Cannabinergic ligands. Chem Phys Lipids. 2003;121:3–19. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(02)00143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmid HHO, Berdyshev EV. Cannabinold receptor-inactive N-acylethanolamines and other fatty acid amides: metabolism and function. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2002;66:363–376. doi: 10.1054/plef.2001.0348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Marzo V, De Petrocellis L, Bisogno T. The biosynthesis, fate and pharmacological properties of endocannabinoids. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2005;168:147–185. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26573-2_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farrell EK, Merkler DJ. Biosynthesis, degradation and pharmacological importance of the fatty acid amides. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:558–568. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merkler DJ, Merkler KA, Stern W, Fleming FF. Fatty acid amide biosynthesis: a possible new role for peptidylglycine α-amidating enzyme and acyl-coenzyme A: glycine N-acyltransferase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;330:430–434. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merkler DJ, Chew GH, Gee AJ, Merkler KA, Sorondo JPO, Johnson ME. Oleic acid derived metabolites in mouse neuroblastoma N18TG2 cells. Biochemistry. 2004;43:12667–12674. doi: 10.1021/bi049529p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilcox BJ, Ritenour-Rodgers KJ, Asser AS, Baumgart LE, Baumgart MA, Boger DL, DeBlassio JL, deLong MA, Glufke U, Henz ME, King L, III, Merkler KA, Patterson JE, Robleski JJ, Vederas JC, Merkler DJ. N-Acylglycine amidation: implications for the biosynthesis of fatty acid amides. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3235–3245. doi: 10.1021/bi982255j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bisogno T, Sepe N, De Petrocellis L, Mechoulam R, Di Marzo V. The sleep inducing factor oleamide is produced by mouse neuroblastoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;239:473–479. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Driscoll WJ, Chaturvedi S, Mueller GP. Oleamide synthesizing activity from rat kidney: identification as cytochrome c. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22353–22363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610070200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caldwell J, Idle JR, Smith RL. The amino acid conjugations. In: Gram TE, editor. Extrahepatic Metabolism of Drugs and Other Compounds. SP Medical and Scientific Books; New York: 1980. pp. 453–492. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozand PT, Gascon GG. Organic acidurias: a review, part 2. J Child Neurol. 1991;6:288–303. doi: 10.1177/088307389100600402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonafé L, Troxler H, Kuster T, Heizmann CW, Chamoles NA, Burlina AB, Blau N. Evaluation of urinary acylglycines by electrospray tandem mass spectrometry in mitochondrial energy metabolism defects and organic acidurias. Mol Genet Metab. 2000;69:302–311. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2000.2982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonham Carter SM, Midgley JM, Watson DG, Logan RW. Measurement of urinary medium chain acyl glycines by gas chromatography-negative ion chemical ionization mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1991;9:969–975. doi: 10.1016/0731-7085(91)80032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rinaldo P, Schmidt-Sommerfeld E, Posaca AP, Heales SJR, Woolf DA, Leonard JV. Effect of treatment with glycine and L-carnitine in medium-chain acyl CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. J Pediatr. 1993;122:580–584. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83539-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang SM, Bisgno T, Petros TJ, Chang SY, Zavitsanos PA, Zipkin RE, Sivakumar R, Coop A, Maeda DY, De Petrocellis L, Burstein S, Di Marzo V, Walker JM. Identification of a new class of molecules, the arachidonyl amino acids, and characterization of one member that inhibits pain. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:42639–42644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107351200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rimmerman N, Bradshaw HB, Hughes HV, Chen JSC, Hu SSJ, McHugh D, Vefring E, Jahnsen JA, Thompson EL, Masuda K, Cravatt BF, Burstein S, Vasko MR, Prieto AL, O’Dell DK, Walker JM. N-Palmitoyl glycine, a novel endogenous lipid that acts as a modulator of calcium influx and nitric oxide production in sensory neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:213–224. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.045997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradshaw HB, Rimmerman N, Hu SSJ, Burstein S, Walker JM. Novel endogenous N-acyl glycines: identification and characterization. Vitam Horm. 2009;81:191–205. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(09)81008-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradshaw HB, Rimmerman N, Hu SSJ, Benton VM, Stuart JM, Masuda K, Cravatt BF, O’Dell DK, Walker JM. The endocannabinoid anandamide is a precursor for the signaling lipid N-arachidonoyl glycine by two distinct pathways. BMC Biochem. 2009;10:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-10-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelley M, Vessey DA. Characterizatin of the acyl-CoA:amino acid N-acyltransferase from primate liver mitochondria. J Biochem Toxicol. 1994;9:153–158. doi: 10.1002/jbt.2570090307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waluk DP, Schultz N, Hunt MC. Identification of glycine N-acyltransferase-like 2 (GLYATL2) as a transferase that produces N-acylglycines in humans. FASEB J. 2010;24:2795–2803. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-148551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Byrne J, Hunt MC, Rai DK, Saeki M, Alexson SE. The human bile acid-CoA:amino acid N-acyltransferase functions in the conjugation of fatty acids to glycine. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34237–34244. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300987200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCue JM, Driscoll WJ, Mueller GP. Cytochrome c catalyzes the in vitro synthesis of arachidonoyl glycine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;365:322–327. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan B, O’Dell DK, Yu YW, Monn MF, Hughes HV, Burstein S, Walker JM. Identification of endogenous acyl amino acids based on a targeted lipidomics approach. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:112–119. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M900198-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aneetha H, O’Dell DK, Tan B, Walker JM, Hurley TD. Alcohol dehydrogenase-catalyzed in vitro oxidation of anandamide to N-arachidonoyl glycine, a lipid mediator: synthesis of N-acyl glycinals. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.10.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burstein SH, Rossetti RG, Yagen B, Zurier RB. Oxidative metabolism of anandamide. Prostagladins Other Lipid Mediat. 2000;61:29–41. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(00)00053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Danielsson O, Atrian S, Luque T, Hjelmqvist L, Gonzàlez-Duarte R, Jörnvall H. Fundamental differences between alcohol dehydrogenase classes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4980–4984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pourmotabbed T, Creighton DJ. Substrate specificity of bovine liver formaldehyde dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:14240–14244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parés X, Vallee BL. New human liver alcohol dehydrogenase forms with unique kinetic characteristics. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1981;98:122–130. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(81)91878-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jonsson KO, Vandevoorde S, Lambert DM, Tiger G, Fowler CJ. Effects of homologues and analogues of palmitoylethanolamide upon the inactivation of the endocannabinoid anandamide. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133:1263–1275. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lambert DM, DiPaolo FG, Sonveaux P, Kanyonyo M, Govaerts SJ, Hermans E, Bueb JL, Delzenne NM, Tschirhart EJ. Analogues and homologues of N-palmitoylethanolamide, a putative endogenous CB2 cannabinoid, as potential ligands for the cannabinoid receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1440:266–274. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown EV. 1949 Penilloaldehydes and penaldic acids. In: Clarke HT, Johnson JR, Johnson R, editors. The Chemistry of Penicillin. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1949. pp. 473–534. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barltrop JA, Owen TC, Cory AH, Cory JG. 5-(3-Carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl)-3-(4-sulfophenyl)tetrazolium, inner salt (MTS) and related analogs of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) reducing to purple water-soluble formazans as cell-viability indicators. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1991;1:611–614. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanghani PC, Robinson H, Bennett-Lovsey R, Hurley TD, Bosron WF. Structure-function relationships in human Class III alcohol dehydrogenase (formaldehyde dehydrogenase) Chem Biol Interact. 2003;143–144:195–200. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(02)00203-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morris GM, Goodsell DS, Halliday RS, Huey R, Hart WE, Belew RK, Olson AJ. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and empirical binding free energy function. J Comput Chem. 1998;19:1639–1662. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huey R, Morris GM, Olson AJ, Goodsell DS. A semiempirical free energy force field with charge-based desolvation. J Comput Chem. 2007;28:1145–1152. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanghani PC, Robinson H, Bosron WF, Hurley TD. Human glutathione-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenase. Structures of apo, binary, and inhibitory ternary complexes. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10778–10786. doi: 10.1021/bi0257639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wagner FW, Parés X, Holmquist B, Vallee BL. Physical and enzymatic properties of a class III isozyme of human liver alcohol dehydrogenase: χ-ADH. Biochemistry. 1984;23:2193–2199. doi: 10.1021/bi00305a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanghani PC, Bosron WF, Hurley TD. Human glutathione-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenase. Structural changes associated with ternary complex formation. Biochemistry. 2002;41:15189–15194. doi: 10.1021/bi026705q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Svensson S, Lundsjö A, Cronholm T, Höög J-O. Aldehyde dismutase activity of human liver alcohol dehydrogenase. FEBS Lett. 1996;394:217–220. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00954-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henehan GTM, Oppenheimer NJ. Horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase-catalyzed oxidation of aldehydes: dismutation precedes net production of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide. Biochemistry. 1993;32:735–738. doi: 10.1021/bi00054a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.