Abstract

Cervical total disc replacement (CTDR) has been increasingly used as an alternative to fusion surgery in patients with pain or neurological symptoms in the cervical spine who do not respond to non-surgical treatment. A systematic literature review has been conducted to evaluate whether CTDR is more efficacious and safer than fusion or non-surgical treatment. Published evidence up to date is summarised qualitatively according to the GRADE methodology. After 2 years of follow-up, studies demonstrated statistically significant non-inferiority of CTDR versus fusion with respect to the composite outcome ‘overall success’. Single patient relevant endpoints such as pain, disability or quality of life improved in both groups with no superiority of CTDR. Both technologies showed similar complication rates. No evidence is available for the comparison between CTDR and non-surgical treatment. In the long run improvement of health outcomes seems to be similar in CTDR and fusion, however, the study quality is often severely limited. After both interventions, many patients still face problems. A difficulty per se is the correct diagnosis and indication for surgical interventions in the cervical spine. CTDR is no better than fusion in alleviating symptoms related to disc degeneration in the cervical spine. In the context of limited resources, a net cost comparison may be sensible. So far, CTDR is not recommended for routine use. As many trials are ongoing, re-evaluation at a later date will be required. Future research needs to address the relative effectiveness between CTDR and conservative treatment.

Keywords: Artificial disc replacement, Fusion surgery, Cervical spine, Patient-related outcomes, Systematic review

Introduction

Spine disorders are related to a major burden of disease in the industrialised world. It is thought that one of the main causes of pain and neurological symptoms in the cervical spine are degenerative cervical conditions, also expressed as degenerative disc disease (DDD), although this concept has been discussed controversially [19]. Most importantly, pain can also be caused by other spinal structures such as facet joints and furthermore, degenerative processes and protrusions are very common and mostly do not cause symptoms.

Usually, pain or neurological symptoms in the cervical spine are treated with non-surgical methods. If this treatment fails, surgical interventions may be considered. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) has been considered as the gold standard for surgical treatment of patients with non-responsive symptoms in the cervical spine, although not for pure axial neck pain.

As an alternative to arthrodesis, cervical total disc replacement (CTDR) is increasingly applied for surgical treatment. During the surgical procedure, the degenerated disc is removed completely and replaced by an artificial device. Different products from various manufacturers exist. It has been suggested that CTDR maintains anatomical disc space height, normal segmental lordosis and physiological motion patterns. In consequence, this should avoid adjacent disc degeneration (ADD) that has been observed in patients after fusion. However, whether ADD is a result of fusion per se or simply part of the natural history of the disease has been discussed controversially [6].

Cervical disc replacement is indicated in patients with pain (radiculopathie and myelopathie) or neurological symptoms related to disc degeneration on one level between C3 and C7 after unsuccessful conservative treatment for at least 6 weeks unless in cases of severe or progressing neurological deficits. Contra-indications are advanced spondylosis, active infection, material allergies, cervical instability, multi-level disease, severe facet joint pathology, osteopenia, osteomalacia, osteoporosis or spinal metastases; additionally, fused levels adjacent to the treatment level has been defined as contra-indication [3], although ongoing research is investigating whether these patients could still undergo CTDR [16, 18].

The therapeutic aim is to reduce pain and disability and to improve quality of life, patient satisfaction and return to work. Additionally, lower rates of ADD should be achieved.

Meanwhile a number of clinical studies have been published that compared total cervical disc replacement with surgical fusion. Some of the earlier studies have already been summarised in reviews [3, 6, 12, 19]. The most recent randomised controlled studies (RCT) have, however, not been included. The aim of this review is therefore to present the currently available evidence in a systematic way.

We aim to answer the research question whether cervical artificial disc replacement is more efficacious and safer than (a) surgical fusion or (b) non-surgical interventions in patients with clinical symptoms due to disc degeneration who have had unsuccessful conservative treatment.

Method

We undertook a systematic literature review according to the current methodological standards [7]. This included a systematic literature search in common medical data bases [Medline via Ovid, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, NHS-CRD-HTA (INAHTA)] that was supplemented by a hand-search. Table 1 demonstrates the criteria we chose for literature search and subsequent selection of references. The literature search was restricted to the period between 2000 and January 2010 and to publications in English or German. In Medline and Embase, we restricted the search to high-level evidence according to ‘evidence-based medicine standards’ and we selected RCTs only from the references identified. Selection of references and data extraction was done by two researchers independently. For summarising the evidence, we used the GRADE methodology that provides a tool to grade the evidence according to pre-defined criteria for each outcome parameter selected [9].

Table 1.

Criteria for literature search

| Population | Patients with pain or neurological symptoms caused by degenerative processes in the cervical spine after failed conservative therapy without prior fusion |

| Intervention | Total artificial disc replacement in the cervical spine |

| Control intervention | 1. Surgical fusion |

| 2. Non-surgical treatment | |

| Outcomes | 1. Patient relevant clinical benefits: reduction of pain and disability, increased quality of life and satisfaction, employment (emphasis on long-term outcomes) |

| 2. Complications: reoperations, product failure or removal, neurological complications, infections, adjacent disc degeneration, death | |

| Study design | RCTs, but no interim results from RCTs or single-centre results from multi-centre RCTs |

Results

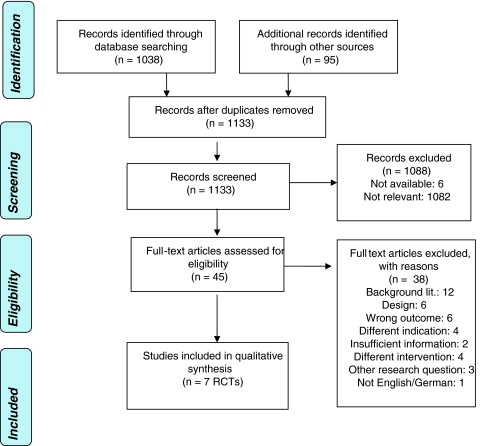

Via systematic search, we identified 1,038 references. Via hand-search and requested material from manufacturers we found further 95 publications resulting in a total number of 1,133 references. The selection process is demonstrated in Fig. 1. As shown in Table 1, we limited the selection of papers to high-level evidence of RCTs. In total, seven RCTs are available that compare cervical disc replacement with fusion. None of the studies addressed the question whether artificial disc replacement is more effective and safer than non-surgical methods. Ten studies that present interim or single-centre results were excluded from the analysis. Additionally, 18 non-comparative case series were excluded from the review.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA tree for study selection

Study characteristics

Study characteristics and results are presented in Table 2. All studies identified compared CTDR with ACDF. Patient inclusion and exclusion criteria in the RCTs differed between the studies and were not always transparently stated. The studies included patients with a minimum age of 18–21 years whose symptoms were related to maximum of two levels (C3–T1). Patients suffered from pain, radiculopathy, myelopathy and/or neurological deficits and had either been unsuccessfully conservatively treated for at least 6 weeks or showed severe neurological symptoms. In most studies, the degenerative process had to be confirmed by radiographic examinations. The most commonly mentioned exclusion criteria were diseases of the facet joints at the affected level, unclear arm or neck pain, severe spondylosis, osteoporosis, allergies against used material, autoimmune diseases (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis), severe diabetes or adipositas, diseases who require long-term medication (e.g. steroids) and mental illness.

Table 2.

Study characteristics of selected RCTs (significant results in bold; figures show first interventional group and second comparator)

| References | Murrey [14] | Heller [10] | Cheng [5] | Anderson [1] | Mummaneni [13] | Nabhan [15] | Robertson [17] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | USA (FDA) multicentre study | USA (FDA) multicentre study | China | USA (FDA) multicentre study | USA (FDA) multicentre study | G | USA |

| Sponsor | Synthes | Medtronic | n.s. | Medtronic | Medtronic | n.s. | Medtronic |

| Product | ProDisc-C | Bryan Cervical disc | Bryan Cervical disc | Bryan Cervical disc | Prestige St Cervical disc | ProDisc-C | Bryan Cervical disc |

| Comparator | ACDF | ACDF + plate | ACDF (+plate) | ACDF + plate | ACDF | ACDF + cage + plate | ACDF + plate |

| Study design | RCT (non-inferiority) | RCT (non-inferiority) | RCT | RCT (non-inferiority) | RCT (non-inferiority) | RCT | RCT + non-comparative registry |

| Number of patients randomised | 209 (103/106) | 582 (290/292) | 65 (31/34) | 463 (242/221) | 625 (313/312) | 49 (25/24) | 305 (103/202) |

| Age of patients (included min/max age) | Ø 42/44 (18–60) | Ø 44/47 (25–78) | Ø 45/47 | n.s. | Ø 43/44 (22–73) | Ø 40 | Ø 56/45 (28–81) |

| Discs per patient | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Follow up (months) | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 36 | 24 |

| Outcome year 1 | |||||||

| NDI | n.s. | −36.6/−31.4 (p0.007) | −38/−33 (p0.03) | n.a. | −34.8/−32.8 (p 0.89) | n.a. | n.a. |

| Pain VAS | |||||||

| Neck pain | n.s. | −51.8/−46.7 (p0.04) | −5.4/−4.6 | n.a. | Figures n.s. | −4.2/−4.2 (p n.s.) | n.a. |

| Arm pain | −54.7/−49.9 (p0.03) | −5.3/−4.8 (p n.s.) | −5.9/−5.7 (p n.s.) | ||||

| SF 36 | |||||||

| Physical component | 81%/76.7%c (p 0.3) | +15.8/+13.7 (p0.010) | +14/+ 12 | n.a. | +12.8/+11.2 (not s.) | n.a. | n.a. |

| Mental component | +10.2/+7 (p0.048) | n.s. | +7.7/+6.1 (not s.) | ||||

| Overall success (OS) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 77.6%/66.4% (p0.004) | n.a. | n.a. |

| Satisfaction | n.s. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Outcome year 2 | |||||||

| NDI | 79.8%/78.3%a (not s.) | 86%/78.9%a (p0.035) | −39/−32 (p0.023) | n.a. | −36/−33.6 (p 0.08) | n.a. | n.a. |

| Pain VAS | |||||||

| Neck pain | 87.9%/86.9%d (p 1.0) | −52.8/−44.5 (p0.009) | −5.8/−4.5 (p0.012) | n.a. | Figures n.s. | −4.2/−3.5 (p n.s.) | n.a. |

| Arm pain | −52.17/−49.7 (p 0.194) | −5.7/−4.5 (p0.013) | −6.1/−5.3 (p n.s.) | ||||

| SF 36 | |||||||

| Physical component | +15.3/+14.5 (p 0.15) | +15/+11 (p0.013) | n.a. | +13.1/+11.8 (not s.) | n.a. | n.a. | |

| Mental component | +9.4/+7.1 (p 0.27) | n.s. | +7.4/+7.5 (not s.) | ||||

| Overall | 79.2%/70%c (p 0.09) | ||||||

| Neurological successb | 90.9%/88% (p 0.638) | 93.9%/90.2% (p 0.1) | n.s. | n.a. | 92.8%/84.3% (p0.006) | n.a. | n.a. |

| Overall success (OS) | 72.3%/68.3% (p0.01 non-inf.) | 82.6%/72.7% (p0.001 non-inf.; p0.01 superior) | n.a. | n.a. | 79.3%/67.8% (p0.004 non-inf.; p0.0053 superior) |

n.a. | n.a. |

| 72.7%/60.4%e (p0.047) | |||||||

| Satisfaction | 83.4/80 (not s.) | n.s. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| Employment | |||||||

| Employment rate | 83%/80% (p 0.71) | 76.8%/73.6% (not s.) | n.a. | n.a. | 75.4%/74.7% (p n.s.) | n.a. | n.a. |

| Return to work time | 48 days/61 days (p0.004) | 45 days/61 days (p0.022) | |||||

| Outcome year 3 | |||||||

| Pain VAS | |||||||

| Neck pain | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | −4.3/−3.7 (p 0.06) | n.a. |

| Arm pain | −6.1/−5.5 (p 0.1) | ||||||

| Drop-out rate | 2 (103)/6 (106) | 60 (290)/98 (292) | 1 (31)/2 (34) | 10% | 91 (313)/115 (312) [3] | 6 (25)/3 (24) | 29 (103)/44 (202) |

| Complications | |||||||

| SSP | 2 (103)/9 (106) | 6 (242)/8 (290) (not s.) | 13 (242)/17 (221) (p0.045) | 5 (276)/23 (265) | n.s. | ||

| IAE | 3 (103)/7 (106) | 2.9%/5.4% | |||||

| SAE | 1.7%/3.2% | 32 (242)/47 (221) | |||||

| GAE | 1 (31)/1 (34) | 82 (242)/64 (221) (p0.023) | 17 (276)/11 (265) | ||||

| ME | 36 (242)/34 (221) (p 0.07) | ||||||

| SADD | 0 (103)/1 (106) | 3 (276)/9 (265) (p 0.07) | 0 (158)/11 (74) (p0.018) | ||||

ACDF anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, CH Switzerland, F France, G Germany, GAE general adverse events, IAE implant or implantation-related serious adverse event (fatal, life threatening, requires hospitalisation, prolongation of hospitalisation, results in persistent or significant disability/incapacity or requires medical/surgical intervention), n.a. not applicable, ME medical events possibly or directly related to operation, NDI neck disability index, non-inf. non-inferiority hypothesis, n.s. not stated, not s. not significant, OS ≥15-point improvement in NDI, no serious adverse events, no additional surgical procedure [13] (maintenance/improvement in neurological parameters) [10, 14], SADD symptomatic adjacent disc disease, SF-36 Short form 36 (mental and physical health survey), SAE serious adverse events (WHO grade 3 + 4) related to implant or operation, SSP secondary surgery procedure (revision, removal or re-operation), VAS visual analogue scale

a>15-point improvement

bMaintenance or improvement in sensory, motor and reflex functions

cAny improvement from baseline

d20% improvement in arm or neck pain

eMinimum clinically important difference hypothesis

Most of the RCTs were conducted in the USA as ‘Food and Drug Administration investigational device exemption studies’ [1, 10, 13, 14]. One study was based in Germany [15] and one in China [5]. In the majority of studies, the artificial disc implanted was the ‘Bryan cervical disc’. Almost all of the RCTs applied a non-inferiority study design. This means that the primary outcome measure is not tested for superiority but for equality. The number of patients in the studies varied from 49 to almost 600. Mean age of the study population was mainly between 40 and 50 years. Patients were followed for 2 years except in one study were the follow-up period was 3 years.

To demonstrate patient-related outcomes studies used the neck disability index (NDI), visual analogue pain scales and a generic instrument for measuring the general health state (SF-36). Additionally, patient satisfaction, the employment rate and the time to return to work were measured. The primary endpoint in the RCTs was a combined endpoint called ‘overall success’. Overall success occurred when patients reached a pre-specified reduction in disability in combination with no serious complications, maintenance or improvement in neurological status and specific radiological parameters.

Overall study quality

According to the GRADE methodology, study results were summarised for each of the selected outcome parameters. The results are shown in Table 3. The methodological quality of the studies was assessed according to the Cochrane checklist [11]. We defined the randomisation process and the blinding of assessors as most important criteria for internal validity of the studies. According to this quality assessment, rating was between fair and poor for the studies included. When more than one study addressed the outcome parameters in question, the results were consistent. The available evidence showed directness, meaning that studies compared the two alternatives in question head to head and addressed the same question as in our research question with respect to population, comparator and outcome. In summary, the strength of evidence for CTDR compared with fusion is moderate. This means that further studies may probably have an important influence on the comparative rating of efficacy and safety.

Table 3.

Evidence-profile: efficacy and safety of cervical artificial disc versus fusion

| No. of studies/patients | Design | Methodological quality | Consistency of results | Directness | Effect size | Other modifying factorsa | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome: NDI; 24 months | |||||||

| 4/1,481 | RCT | Fair/poorb | Yes | Direct | Improvement in both groups; slightly better but mostly insignificant improvement in CTDR-group | No | Moderate |

| Outcome: Pain VAS; (1) 24 months; (2) 36 months | |||||||

| (1) 4/905 | (1) RCT | (1) Poorb | (1) Yes | Direct | (1) Improvement in both groups; slightly better but only partly significant improvement in CTDR-group | No | Moderate |

| (2) 1/49 | (2) RCT | (2) Poorb | (2) Only 1 study | Direct | (2) No difference between groups | ||

| Outcome: SF-36; 24 months | |||||||

| 4/1,481 | RCT | Fair/poorb | Yes | Direct | Improvement in both groups; CRI unclear; no sign. difference (except physical component in one study) between groups | No | Moderate |

| Outcome: Neurological success; 24 months | |||||||

| 3/1,416 | RCT | Fair/poorb | Yes | Direct | Improvement in both groups (~90% of patients), slightly better but mostly insignificant improvement in CTDR-group | No | Moderate |

| Outcome: satisfaction; 24 months | |||||||

| 1/209 | RCT | Fairc | Yes | Direct | Both groups highly satisfied, no sign. difference between groups | No | Moderate |

| Outcome: overall success; 24 months | |||||||

| 3/1,416 | RCT | Fair/poorb | Yes | Direct | Slightly and significantly more (max. 83%) reached success criterion in CTDR-group compared with Fusion group (max. 73%) | No | Moderate |

| Outcome: (1) employment rate; 24 months; (2) return to work; 24 months | |||||||

| (1) 3/1,416 | (1) RCT | (1) Fair/poorb | Yes | Direct | (1) ~3/4 in both groups employed, no sign. difference between groups | No | Moderate |

| (2) 2/834 | (2) RCT | (2) Fairb | Direct | (2) CTDR-group returned to work sign. earlier (~15 days) | |||

| Outcome: Complications; 24 months | |||||||

| 7/2,591 | RCT | Fair/poorb | Yes | Direct | Secondary surgical procedure: 2–5% CTDR-group; 3–9% fusion group. Implant(ation)-related complications: 3% CTDR-group; 5–7% fusion group. Serious adverse events: 2–13% CTDR-group; 3–21% fusion group. General adverse events: 3–34% CTDR group; 3–29% fusion group. Operation-related events: 15% CTDR group; 15% fusion group. SADD: 0–1% CTDR group; 1–15% fusion group | No | Moderate |

SADD symptomatic adjacent disc disease, CTDR group cervical total disc replacement group, sign. significant, d days, CRI clinically relevant improvement

aLow incidence, lack of precise data, strong or very strong association, high risk of reporting bias, dose-efficacy gradient, residual confounding plausible

bITT-Analysis not conducted or not stated; treatment groups at baseline only partly comparable or baseline characteristics not stated; no blinding of outcome assessment; drop-out rate >20%; non-inferiority design problematic

cNo blinding of outcome assessment; ITT-Analysis not stated

Efficacy of CTDR compared with fusion

After 2 years, studies consistently demonstrated that in terms of the combined endpoint ‘overall success’ artificial disc replacement (with the products Pro-Disc C, Prestige St, Bryan Cervical disc) is not inferior to fusion [10, 13, 14]. Non-inferiority was statistically significant. Additionally, two studies [10, 13] showed a slight and statistically significant superiority of 4–11% points.

Concerning the parameters disability, pain, general health state (SF-36), neurological success and satisfaction, improvement was demonstrated in both groups. Except for some selected sub-categories in single studies (e.g. neck pain), benefits for the patients in the CTDR-group were not significantly higher than for those in the fusion group [5, 10, 13–15]. Furthermore, in two studies [13, 14] patients in the prothesis group returned to work on average 15 days earlier than patients in the fusion group. However, no difference in the employment rate was found after 2 years.

In one study [15], pain reduction was additionally evaluated after 3 years where no difference between the two groups could be demonstrated. None of the technologies achieves complete disappearance of symptoms.

Safety of CTDR compared with fusion

The most common complications in both groups were ‘general complications’ (e.g. wound infection, dysphagia/dysphonia, allergic reactions). They occurred in maximal one-third of patients in both groups. One study demonstrated a significantly higher rate of ADD in the fusion group [17], however, the rate of secondary surgical procedures was not statistically different between the groups (up to 5% of prothesis-patients and up to 9% of fusion-patients had to undergo a re-operation). No procedure-related deaths were reported. Frequency of complications was very similar between the two groups but differed considerably between studies.

Discussion

The review has shown that individual patient-related outcomes (quality of life, pain reduction, disability) were not better in the prothesis group than in the fusion group. Although marginal superiority could be demonstrated for specific sub-parameters (e.g. return to work), the benefit is relative in the general context. For example, while some studies demonstrated that patients after disc replacement return to work a few days earlier, the overall employment rate after 2 years did not differ between the groups. Complications are similar in both groups.

The only parameter that consistently showed statistically significant results was the combined endpoint ‘overall success’. The non-inferiority design means that this primarily confirms that artificial disc replacement is not worse than surgical fusion. Only two studies demonstrated a marginal but clinically questionable benefit of disc replacement over fusion for the endpoint ‘overall success’ [10, 13]. Moreover, the validity of the individual components of the combined endpoint has been debated. For example, superiority for the composite outcome in the ‘Prestige St trial’ and in one of the ‘Bryan trials’ [10] is most certainly attributable to the problematic neurological component in the composite measure [3].

The validity of the study results is limited for the following reasons: First, the non-inferiority design is usually less stringent for demonstrating efficacy than a standard clinical trial. It is usually employed when a margin of inferiority of a new technology is accepted because it is offset by some other advantages such as less invasiveness, lower costs, etc. Such advantages were not evident in the case of the artificial disc trials. Hence, the study design is questionable [2]. Secondly, study quality is limited due to unblinding of outcome assessors, exclusion of patients after randomisation and unclear or no intention-to-treat-analysis. Additionally, some studies have shown high drop-out rates [10, 13] and used non-validated instruments for eliciting patient-related outcomes [10, 13]. This could have biased the results towards the intervention group. Finally, patients are on average between 40 and 50 years old. Hence, long-term durability and performance of the device are very important. The follow-up period of 2 years is too short to obtain evidence on the long-term success of the device.

At least 14 studies on cervical artificial discs are registered as ongoing. Some interim results have already been presented at conferences but publications showing the relevant data have not been available so far.

Not least, according to MRT studies, degenerative changes of the intervertebral disc are often wrongly considered as causes of pain [4, 19]. Bearing this in mind, the decision for surgical intervention needs to be made very carefully. As a study by Grob et al. [8] shows, the spectrum of indications in general practice is wider (e.g. multi-level disease) than the inclusion criteria in clinical studies. More long-term observational data are required to evaluate whether these patients benefit from CTDR. Additionally, due to the numerous contra-indications very few patients may be considered for surgical interventions per se. In that context, it seems to be a severe deficit that no studies have been conducted so far which compare artificial disc replacement with non-surgical interventions.

The main limitation of the paper is related to the methodology of systematic reviews. Although the review is based on standard methodological approaches and uses validated quality checklists, the final judgement of the technologies under evaluation is ultimately subjective. We tried to address this limitation by being as transparent as possible about the research process, the data used and the judgements made. As even more studies will become available, a meta-analysis could be undertaken to summarise the study results in a quantitative manner.

Conclusion

Cervical total disc replacement has been presented as a promising new technology to treat patients with pain or neurological symptoms secondary to degenerated discs that do not respond to conservative treatment within 6 weeks. The evidence from randomised controlled clinical studies has shown that after 2 years CTDR is equal to fusion surgery in terms of outcomes and complications. In the context of limited resources, we recommend to additionally analyse the costs of the two technologies and to propose the technology that shows lower net costs until new research data is available. Because a number of studies are ongoing, we need to re-evaluate the technology when new evidence is available. Until then, CTRD is not recommended for routine use but should be restricted to research settings only.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Silvia Brandstätter for her valuable comments on earlier versions of the manuscript and to Tarquin Mittermayr for the support in the systematic literature search.

References

- 1.Anderson PA, Sasso RC, Riew KD, Anderson PA, Sasso RC, Riew KD. Comparison of adverse events between the Bryan artificial cervical disc and anterior cervical arthrodesis. Spine. 2008;33:1305–1312. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817329a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blue Cross Blue Shield A (2007) Artificial lumbar disc replacement. Blue Cross Blue Shield Association (BCBS), Chicago

- 3.Blue Cross Blue Shield A (2008) Artificial intervertebral disc arthroplasty for treatment of degenerative disc disease of the cervical spine. Technology evaluation center assessment program. Executive summary, vol 24, pp 1–4 [PubMed]

- 4.Boos N, Rieder R, Schade V, Spratt KF, Semmer N, Aebi M. 1995 Volvo award in clinical sciences. The diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging, work perception and psychosocial factors in identifying symptomatic disc herniations. Spine. 1995;20:2613–2625. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199512150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng L, Nie L, Zhang L, Hou Y, Cheng L, Nie L, Zhang L, Hou Y. Fusion versus Bryan cervical disc in two-level cervical disc disease: a prospective, randomised study. Int Orthop. 2009;33:1347–1351. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0655-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fekete TF, Porchet F. Overview of disc arthroplasty-past, present and future. Acta Neurochir. 2009;152:392–404. doi: 10.1007/s00701-009-0529-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gartlehner G (2007) Internes Manual. Abläufe und Methoden. In: LBI-HTA (ed) LBI-HTA, Vienna

- 8.Grob D, Porchet F, Kleinstuck FS, Lattig F, Jeszenszky D, Luca A, Mutter U, Mannion AF (2009) A comparison of outcomes of cervical disc arthroplasty and fusion in everyday clinical practice: surgical and methodological aspects. Eur Spine J 19(2):297–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Guyatt G, Oxman A, Vist G, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann H. For the GRADE Working Group Rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Br Med J. 2008;336:924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heller JG, Sasso RC, Papadopoulos SM, Anderson PA, Fessler RG, Hacker RJ, Coric D, Cauthen JC, Riew DK, Heller JG, Sasso RC, Papadopoulos SM, Anderson PA, Fessler RG, Hacker RJ, Coric D, Cauthen JC, Riew DK. Comparison of BRYAN cervical disc arthroplasty with anterior cervical decompression and fusion: clinical and radiographic results of a randomized, controlled, clinical trial. Spine. 2009;34:101–107. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818ee263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins JPT, Green S, The Cochrane Collaboration (eds) (2009) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.0.2 (updated September 2009)

- 12.Medical Advisory Secretariat (2006) Artificial disc replacement for lumbar and cervical degenerative disc disease-update: an evidence-based analysis. Medical Advisory Secretariat, Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MAS), Toronto [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Mummaneni PV, Burkus JK, Haid RW, Traynelis VC, Zdeblick TA, Mummaneni PV, Burkus JK, Haid RW, Traynelis VC, Zdeblick TA. Clinical and radiographic analysis of cervical disc arthroplasty compared with allograft fusion: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:198–209. doi: 10.3171/spi.2007.6.3.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murrey D, Janssen M, Delamarter R, Goldstein J, Zigler J, Tay B, Darden B, Murrey D, Janssen M, Delamarter R, Goldstein J, Zigler J, Tay B, Darden B. Results of the prospective, randomized, controlled multicenter Food and Drug Administration investigational device exemption study of the ProDisc-C total disc replacement versus anterior discectomy and fusion for the treatment of 1-level symptomatic cervical disc disease. Spine J. 2009;9:275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nabhan A, Ahlhelm F, Pitzen T, Steudel WI, Jung J, Shariat K, Steimer O, Bachelier F, Pape D, Nabhan A, Ahlhelm F, Pitzen T, Steudel WI, Jung J, Shariat K, Steimer O, Bachelier F, Pape D. Disc replacement using Pro-Disc C versus fusion: a prospective randomised and controlled radiographic and clinical study. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:423–430. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0226-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips FM, Allen TR, Regan JJ, Albert TJ, Cappuccino A, Devine JG, Ahrens JE, Hipp JA, McAfee PC, Phillips FM, Allen TR, Regan JJ, Albert TJ, Cappuccino A, Devine JG, Ahrens JE, Hipp JA, McAfee PC. Cervical disc replacement in patients with and without previous adjacent level fusion surgery: a prospective study. Spine. 2009;34:556–565. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31819b061c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robertson JT, Papadopoulos SM, Traynelis VC, Robertson JT, Papadopoulos SM, Traynelis VC. Assessment of adjacent-segment disease in patients treated with cervical fusion or arthroplasty: a prospective 2-year study. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3:417–423. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.3.6.0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sekhon LH, Sears W, Duggal N, Sekhon LHS, Sears W, Duggal N. Cervical arthroplasty after previous surgery: results of treating 24 discs in 15 patients. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3:335–341. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.3.5.0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.W. C. B. Evidence Based Practice Group (2005) Artificial cervical and lumbar disc implants: a review of the literature. WorkSafe BC Richmond, BC