Abstract

Rationale

Recent developments in cardiac simulation have rendered the heart the most highly integrated example of a virtual organ. We are on the brink of a revolution in cardiac research–one in which computational modeling of proteins, cells, tissues and the organ allow to link genomic and proteomic information to the integrated organ behavior, in the quest to provide quantitative understanding of the functioning of the heart in health and disease.

Objective

The goal of this article is to assess the current state-of-the-art in whole-heart modeling and the plethora of its applications in cardiac research.

Methods and Results

General whole-heart modeling approaches are presented, and the applications of whole-heart models in cardiac electrophysiology and electromechanics research are reviewed. The article showcases the contributions that whole-heart modeling and simulation have made to our understanding of the functioning of the heart. A summary of the future developments envisioned for the field of cardiac simulation and modeling is also presented.

Conclusions

Biophysically-based computational modeling of the heart, applied to human heart physiology and the diagnosis and treatment of cardiac disease, has the potential to dramatically change twenty-first century cardiac research and the field of cardiology.

Keywords: whole-heart model, electrophysiological modeling, electromechanical modeling, simulation, cardiac disease

1. Introduction

Modeling and simulation has long been intertwined with the biological sciences, including cardiac research. The review articles in this issue of Circulation Research provide vivid examples of this relationship, and underscore the newly-found power of cardiac simulation. Modern cardiac research has increasingly recognized that appropriate models and simulation can help interpret a vast array of experimental data and dissect important mechanisms and inter-relations. Paraphrasing Cohen1, modeling and simulation are becoming cardiac research community’s “next microscope, only better”. As advances in computer modeling have transformed many traditional areas of physics and engineering, they are also transforming the understanding of cardiac function in health and disease and the clinical practice of cardiology.

Recent developments in cardiac simulation have rendered the heart the most highly integrated example of a virtual organ. These developments are firmly anchored in the long history of cardiac cell modeling (this year marks the 50th anniversary of the first ion-current based myocyte model2), and are firmly rooted in the iterative interaction between modeling and experimentation. Importantly, modeling the function of the heart has benefitted significantly from the revolution in medical imaging and from the systematic incorporation of validated biophysical relationships, resulting in a dramatic enhancement of the physiological relevance of heart models. Today, both the opportunities and the challenges presented to whole-heart modeling arise from the heterogeneities of the biological “units” in the hierarchy of structural organization and from the often unpredictable outcomes of their interaction (emergent phenomena) across the temporal and spatial scales. We believe we are on the brink of a revolution in cardiac research –one in which computational modeling of proteins, cells, tissues and the organ will allow linking genomic and proteomic information to integrated organ behavior.

The goal of this article is to assess the current state of whole-heart modeling. We present the general modeling approaches, and review the applications of whole-heart models in cardiac electrophysiology and electromechanics research. Cardiac modeling has been strongly driven by the notion that “the purpose of computing is insight, not numbers”3, and this article underscores the profound contributions that whole-heart modeling and simulation have made to our understanding of the functioning of the heart. To limit the scope of the review, we focus on ventricular models only (referring to them as whole-heart models), as the ventricles are the major pump as well as the perpetrator of the most lethal arrhythmias.

2. General Approach to Whole Heart Modeling

2.1 Model Components

A schematic of the general approach to modeling cardiac electromechanical function is shown in Fig. 1A. It consists of two coupled parts, which simulate the electrical and the mechanical functions of the heart, respectively. As an electrical wave propagates through the heart, the depolarization of each myocyte initiates release of calcium from its intracellular stores, followed by binding of calcium to Troponin C and cross-bridge cycling. The latter forms the basis for contractile protein movement and the development of active tension in the myocyte, leading to deformation of the ventricles. The electromechanical model of the heart represents these processes.

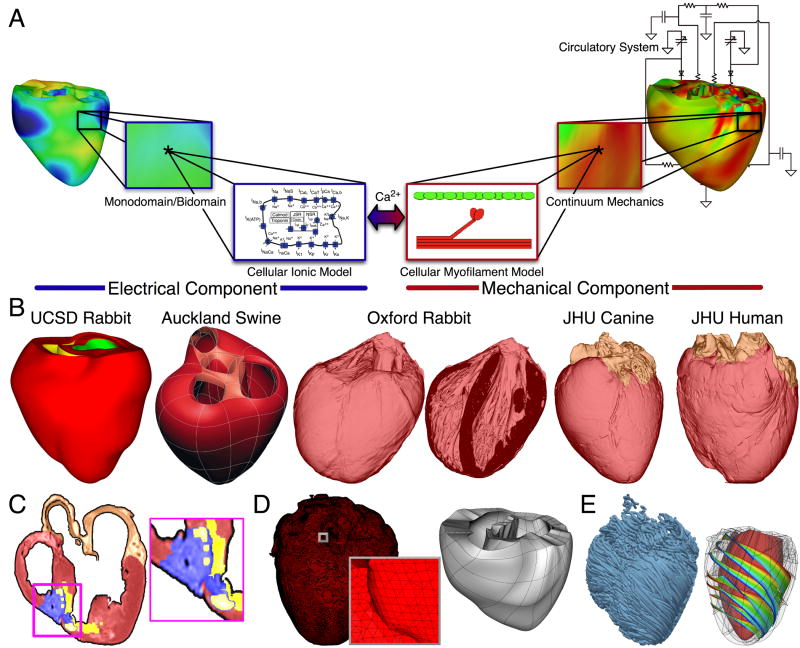

Fig. 1.

Whole-heart modeling. A. General approach to modeling cardiac electromechanical function. B. Geometrical models. C. Delineation of atria, and of infarct core (yellow) and border zone (blue) of an infracted canine heart. D. Computational meshes of the canine heart (electrical and mechanical). E. Fiber and sheet orientations obtained from canine heart DTMRI. Images modified from.11, 15, 17

The electrical component of the model in Fig. 1 simulates the propagation of a wave of transmembrane potential by solving the monodomain reaction-diffusion partial differential equation4, PDE (or a system of coupled PDEs if the extracellular current flow is explicitly accounted for, i.e. the bidomain problem) over the volume of the heart. The reaction-diffusion PDE describes current flow through myocytes that are electrically connected via low-resistance gap junctions. Cardiac tissue has orthotropic passive electrical conductivities that arise from the cellular organization of the heart into fibers and laminar sheets.5 Global conductivity values are obtained by combining fiber and sheet organization with myocyte-specific local conductivity values. Current flow in the tissue is driven by active processes of ionic exchanges across myocyte membranes. These processes are represented by the cellular ionic model (Fig. 1A), where current flow through ion channels, pumps and exchangers as well as subcellular calcium cycling are governed by a set of ordinary differential (ODE) and algebraic equations; ionic models of different complexity are currently in use.6 Simultaneous solution of the PDE(s) with the set of ionic model equations represents simulation of electrical wave propagation in the heart. The intracellular calcium released during electrical activation couples the electrical and mechanical components of the model (Fig. 1A). It serves as an input to the cellular myofilament model, representing the generation of active tension within each myocyte, where sets of ODEs and algebraic equations describe, to a varying degrees of complexity7, 8, calcium binding to Troponin C, cooperativity between regulatory proteins, and cross bride cycling. Contraction of the ventricles arises from the active tension generated by the myocytes. Deformation of the organ is described by the equations of continuum mechanics9, with the myocardium being an orthotropic, hyper-elastic, and nearly-incompressible material with passive properties defined by an exponential strain energy function. Simultaneous solution of the myofilament model equations with those representing passive cardiac mechanics over the volume of the heart (Fig. 1A) constitutes simulation of cardiac contraction. During contraction, the stretch ratio (ratio of myocyte length before and after deformation) and its time derivative influence, in turn, cellular myofilament dynamics, including length-dependent calcium sensitivity. Finally, to simulate the cardiac cycle and the corresponding pressure-volume loop, conditions on chamber volume and pressure are imposed by a lumped-parameter models of the systemic and pulmonic circulatory systems10, 11 (Fig. 1A). Note that currently fully coupled electromechanical modeling is still the exception rather than the rule in the cardiac modeling community (see section 4 for detail).

2.2 Whole heart model geometry and anatomical structure

Whole-heart electromechanical models are modular in the sense that they can provide solutions to electrophysiological or electromechanical problems on user-specified whole-heart geometries, which can be idealized (such as cylindrical and elliptical shapes12, 13 or anatomically-accurate, the latter either representing averaged geometries obtained from histological sectioning14–16 or individual hearts’ geometry and structure11, 17, 18, as obtained from MR images.19, 20 The modular structure of the model also allows the use of any cellular ionic and myofilament models, of different species and with different levels of biophysical detail.

Fig. 1B presents different whole-heart geometries used in electrophysiological and electromechanical modeling. The first two hearts (rabbit, UCSD data14, and swine, Auckland data15) are examples of averaged geometries obtained from histological sectioning, while the other three are examples of image-based individual geometries17. Using MRI data for model geometry also allows to represent individual hearts’ structural remodeling, such as infarction (Fig. 1C; see ref.17 for detail on infarct segmentation).

Solutions to electrophysiological or electromechanical whole-heart models nowadays involve the use of the finite element method. The governing equations are thus solved on a spatially-discretized version of the heart volume, i.e. on the computational mesh. The electrical and mechanics parts of the model have different requirements regarding the degree of discretization (i.e. element size) as well as the element type, thus the two parts of the model require two different computational meshes. The electrical mesh requirements are based on spatiotemporal characteristics of wave propagation; a spatial resolution of about 250–300um is appropriate for electrophysiological finite element models4. A novel approach was recently published21 for electrical mesh generation directly from segmented MRI images. The meshing technique is automatic, and produces boundary-fitted and locally-refined meshes (Fig. 1D). The mechanical mesh, on the other hand, typically consists of hexahedral elements with Hermite basis. This choice of finite elements increases the degree of strain continuity and is appropriate for maintaining incompressibility constraints22. The mechanical mesh of the heart can also be generated directly from segmented MR images11 (Fig. 1C).

Fiber and laminar sheet organization underlie the orthotropic electrical conductivities of the tissue and its mechanical properties. In the electrical mesh, local fiber and sheet directions are typically mapped at the centroids of the finite elements, while in the mechanics mesh, fiber and sheet orientations and their derivatives are defined at mesh nodes and then interpolated over the elements. This is typically done based on histological sectioning information14–16 or on diffusion tensor (DT) MR data11, 17 (the primary, secondary, and tertiary eigenvectors of the water diffusion tensors are aligned with the fiber direction, with the direction transverse to the fiber direction and in the plane of the laminar sheet, and with that normal to the laminar sheet, respectively19). The same procedure is used for fiber mapping in hearts with structural remodeling such as infarction17; DTs are mapped on every finite element centroid, followed by the delineation of the infarct scar and border zone. Fig. 1D presents fiber orientation, as reconstructed from DTMR images, in the electrical mesh of a slice of the canine heart and in the whole canine heart, and the sheet orientations in the ventricular mechanics mesh. In cases where neither histological nor DTMR imaging information is available, rule-based approaches have been used18 to assign fiber orientation consistent with measurements.

2.3 Numerical solutions

Simulations of whole heart electromechanical function are typically executed on parallel high performance computing hardware. The electrical problem is significantly more computationally demanding than the mechanical; notable packages used in simulations include MEMFEM23 and CARP24. A review of the various numerical approaches used in solving the electrical problem is included in the Online Supplement.

3. Cardiac Electrophysiology Applications

This section reviews the application of whole-heart models in cardiac electrophysiology, and specifically, in the study of normal propagation in the heart as well as of the mechanisms that give rise and maintain cardiac arrhythmias under normal and pathological conditions. Modeling in all the studies reviewed here involved the use of electrical ventricular models of different species (left component in Fig. 1A).

As the different sections below describe, whole heart modeling has often been used to test hypotheses regarding phenomena, the existence of which cannot be proven directly with experimental methods, such as behavior within the depth of the ventricular walls. In testing such hypotheses, whole heart models constrained and subsequently validated with available experimental data have been used. The predicative capabilities of whole heart electrophysiological models have been ascertained most frequently with optical or electrical mapping recordings of normal or reentrant propagation on the epicardial surfaces, or with global experimental variables such as, for instance, defibrillation thresholds. With the advent of image-based individual heart models, the expectation is that experiments will be conducted with the same heart that the model is generated from, ensuring an unprecedented match between experimental and simulation results.

3.1 Models of ventricular propagation

While the vast majority of electrophysiological whole-heart applications pertain to the mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmias, there are a handful of studies that have focused on the properties of normal wave propagation in the ventricles18, 25–28, providing insight, that cannot be obtained by experimentation, into the role of organ structure in the patterns of wave propagation and repolarization. Two studies are particularly notable. The study by Samson and Henriquez27 investigated how heart size (by comparing an MRI-based mouse ventricular model to the UCSD rabbit model), myocardial properties, and spatial distribution of cell types affect functional action potential duration (APD) dispersion within the ventricular volume. The authors concluded that a larger heart size decreases global electrotonic effects and unmasks intrinsic APD differences between cell types, thus increasing APD dispersion. The second is the recent study by Bishop and co-workers,18 which employed the high-resolution MRI-based Oxford rabbit heart model (Fig. 1B, ~25um raw-data resolution). Since the model included blood vessels and endocardial trabeculations, it was used to ascertain the role of these structural heterogeneities in ventricular propagation. Fig. 2A illustrates the propagation of a wavefront elicited at the apex in this model compared to that in a simplified whole-heart model based on the same imaging data but excluding vessels and trabeculations. The results underscore the regional differences in activation due to shortcut pathways and indicate the important role cardiac microstructure could play in impulse propagation.

Fig. 2.

Role of structural complexities in wave propagation in the rabbit ventricle. A. Paced propagation (from apex) in models with and without endocardial trabeculations and blood vessels. B. Spiral wave propagation. Images modified from.18, 35

3.2 Models of ventricular arrhythmia mechanisms

Most of the whole-heart models used in the study of arrhythmia mechanisms have focused on the self-sustained reentrant propagation of complex 3D waves. Historically, these were the first applications of whole heart modeling29–32. Whole-heart modeling studies have revealed important aspects of reentrant arrhythmias that could not have been established via experimentation alone, among which the dynamic characteristics of ventricular fibrillation (VF), and the role of alternans and restitution in arrhythmogenesis.

The first demonstrations that whole-heart modeling of arrhythmias is feasible and tractable came from Winslow’s team at Johns Hopkins University (in a series of public presentations about 10 years ago), and from the work of Panfilov and Keener29 at the University of Utah. In the latter, the authors developed a 3D model of scroll-wave activation using the Auckland canine geometry16 and the 2-variable FitzHugh-Nagumo model of cellular kinetics. The study demonstrated that the organizing centers (filaments) of reentrant activity in the structurally-normal heart could be maintained entirely within the myocardial wall, manifesting themselves as focal sources on the surfaces. The same model was subsequently used30 to propose that while in small hearts (mice, rabbits) a single rapidly drifting and meandering rotor could underlie VF, in large hearts, including those of humans, VF could be sustained by numerous co-existing rotors. Panfilov31 extended this concept by demonstrating, in the same model, that not only the presence of scroll waves, but also their breakup (dynamical instability) was relevant to VF sustenance. Winslow and co-workers were the first to utilize models reconstructed from MRI scans 32, 33, using a rabbit heart model, the authors demonstrated that early after-depolarizations (EADs) can lead to reentrant arrhythmias. The role of the complex ventricular geometry in wave fragmentation and spiral wave break-up was explored by Xie et al.34 The presence of cardiac microstructure was also found to impact the reentrant wave (Fig. 2B),35 in a manner similar to the way it alters normal propagation.

Whole-heart models have been used extensively in characterizing VF. Clayton and coworkers36 examined the evolution of VF within the 3D volume of the rabbit and canine ventricles by quantifying the dynamics of the scroll-wave filaments. These studies determined the number of filaments and their lifetimes, and classified their shapes, which depend on the location of the filaments within the ventricles. Furthermore, the number of the scroll-wave filaments in the rabbit ventricles was found to increase in the presence of APD heterogeneity caused by the inward rectified K+ current gradient. While such heterogeneity has been reported to result in mother-rotor fibrillation, where VF is driven by a single rapid and stationary rotor in the region of shortest refractory period37, it remained unclear how an initial rotor could migrate to this region38. This question was answered by the simulation study of Baher et al39; results from this rabbit whole-heart model demonstrated that the inclusion of short-term memory (effect of pacing history on APD) resulted in spontaneous conversion of multiple-wavelet to mother-rotor fibrillation. Finally, in recent years, advances have been made to characterize VF in the human heart.40, 41 The geometrical data for the model were obtained from histological slices of an ex-vivo normal human heart, with fiber architecture mapped from the canine. Intriguingly, modeling results40 demonstrated that human VF is driven by a small number of reentrant sources (~10), and is thus much more organized than VF in animal hearts of comparable size (~50 sources). Among the numerous factors examined in this study as contributing to human VF organization, the minimum APD had the largest effect on the number of rotors, a property that differs significantly between the human and large animal hearts.

Electrical alternans, which are beat-to-beat changes in APD, have long been recognized as a precursor to the development of VF. Alternans can be concordant with the entire tissue experiencing the same phase of oscillation, or discordant, with opposite-phase regions distributed throughout the tissue. Over the last decade, much emphasis has been placed on the restitution curve slope as a major factor in both the onset of arrhythmias following the development of discordant alternans, and the dynamic destabilization of reentrant waves leading to the transition of ventricular tachycardia (VT) into VF. In what has become known as the restitution hypothesis, flattening the APD restitution curve is postulated to inhibit alternans development and subsequent conduction block, and prevent the onset of fibrillation.42 Simulation studies employing whole-heart models43–47 have made important contributions to ascertaining the intricate set of mechanisms by and the conditions under which steep APD restitution could lead to VF onset. Using the rabbit ventricular model, Echebarria and Karma44 demonstrated that in homogenous tissue with steep APD restitution, the transition from concordant to discordant alternans is dynamical, with contributing mechanisms being both a broad conduction velocity (CV) restitution or a localized change in pacing period. Furthermore, the study found that a sudden change in pacing rate could initiate discordant alternans in the presence of a spatial gradient in APD restitution without the involvement of CV restitution. Cherry and Fenton45 found, using the same model, that electrotonic and memory effects can suppress alternans, prevent conduction block, and stabilize reentrant waves even when APD restitution is steep. Using the human whole-heart model,40 Keldermann et al46 investigated the effect of heterogeneous restitution properties in human VF by incorporating clinically-measured APD restitution. The study found that the number of filaments and the excitation periods depended on the extent of restitution heterogeneity. Thus, restitution heterogeneity was found to contribute to VF dynamics complexity. In a follow-up study,47 the authors found that under heterogeneous APD restitution, both mother-rotor and multiple-wavelet VF could occur in the same heart, indicating that mother-rotor is a possible mechanism of human VF.

3.3 Models of arrhythmias in the diseased heart

Whole-heart computational research into arrhythmia mechanisms in the setting of cardiac disease remains in its infancy, and is one of the potential avenues for growth in wholeheart modeling applications. Simulation research into regional ischemia and infarction in the ventricles has charted the initial path in this direction, by providing insights into the role of electrophysiological and structural heterogeneities associated with cardiac disease in arrhythmia generation. The recent study by Jie et al48 characterized the substrate for ischemia phase 1B arrhythmias in the rabbit heart (Fig. 3A) by examining how the interplay between different degrees of hyperkalemia in the surviving layers, and the level of cellular uncoupling between these layers and the mid-myocardium combine with the specific geometry of the ischemic zone in the ventricles to result in reentrant arrhythmias. The study implemented a realistic representation of the ischemic insult (hyperkalemia, acidosis, hypoxia), including its spatial distribution (a central ischemic zone, CIZ, and border zones, BZ). It demonstrated a biphasic change in arrhythmia vulnerability with the increase in extracellular potassium concentration. Fig. 3A shows the model as well as the generation of reentry in the sub-epicardium following the slow propagation of a premature stimulus. While the surviving subepicardium and subendocardium exhibited the same changes in electrophysiologic properties for varying degrees of hyperkalemia, conduction block occurred preferentially in the subendocardium during both pacing and premature stimulation due to geometrical factors (Fig. 3A), resulting in reentry being formed only in the subepicardium. Furthermore, the simulation results found that a wide BZ reduced the inducibility of reentry by causing a propagation block in CIZ. Finally, the degree of uncoupling between the surviving (epi- and endocardial) layers and the inexcitable mid-myocardium was found to profoundly affect reentry initiation: stronger coupling led to shortened APD and lengthened post-repolarization refractory period of the paced propagation, which in turn reduced inducibility of reentry by blocking propagation of the premature wavefront.

Fig. 3.

Arrhythmias in ischemia and infarction. A. Arrhythmogenic substrate in ischemia phase 1b. Left: Model of ischemia phase 1b following LAD occlusion in the rabbit heart, with central ischemic zone (CIZ) and border zone (BZ). Colors distinguish the regions. White dashes outline BZ. Asterisk indicates the stimulus site. Border zones for different ischemic parameters are also shown. Right: Generation of reentry in the sub-epicardium following propagation of premature stimulus in myocardium uncoupled from the surviving endo- and epicardium. Activation maps on the anterior epicardial surface and in a cross-section across the LV are shown. S2 and R refer to activation maps for the premature and the first reentrant beats, respectively. Black asterisk indicates reentry exit site. Figure modified from48. B. Infarct-related VT in the canine heart. Left panel: MRI-based model of the infracted canine heart with scar and BZ. Remaining panels: Activation maps of VT following programmed stimulation. Arrows indicate direction of propagation.

An example of simulations of infarct-related VT using an MRI-based canine heart model (see Fig. 1C) is presented in Fig. 3B. The model incorporated experimental data on electrophysiological remodeling in BZ, including altered ionic channel expression49, 50 and connexin 43 downregulation.51 Programmed stimulation from the endocardial surface in this model revealed52–54 conduction slowing in the BZ giving rise to VT inducibility and reentrant circuit morphology consistent with experimental data. Fig. 3B illustrates epicardial and intramural views of the activation patterns during ventricular tachycardia induction from an endocardial pacing site near the apex.55 The simulation results demonstrated that the organizing center of infarct-related VT is located within the BZ, regardless of the pacing site from which VT is induced. This result has important implications for ablation of infarct-related VT; further simulation studies on the subject are expected to provide simulation guidance of VT ablation in patients.

3.4 Ventricular models of arrhythmia initiation with electric shocks and defibrillation

Ventricular models incorporating realistic geometry have also been used to examine the mechanisms by which a defibrillation shock induces arrhythmia and defibrillates (terminates VF) in the heart. Whole-heart modeling research has proven particularly indispensible in uncovering these mechanisms since the electric shock induces virtual electrode polarization in the heart that is a function of organ structure, a relationship which is difficult to tease out by experimentation. These models are accompanied by further complexities, as they require the use of the bidomain representation of cardiac tissue (see section 2.1). Research devoted to the numerical aspects of bidomain modeling is reviewed in the Online Supplement.

A series of studies from Trayanova’s group were devoted to determining the mechanisms by which a defibrillation shock fails or succeeds in terminating VF. The bidomain model of the rabbit ventricles23, 56 was employed to determine the mechanisms by which virtual electrode polarization is induced following a defibrillation shock23 and those by which post-shock activations originate. In studies of arrhythmogenesis with external monophasic shocks in the same model, Rodríguez et al57, 58 demonstrated that shock outcome and the type of post-shock arrhythmia induced by the shock depend on the location of the intramural postshock excitable area formed by shock-induced de-excitation of previously refractory myocardium.

The article by Ashihara et al59 extended these findings in the rabbit ventricles to propose a new theory of postshock propagation and shock-induced arrhythmogenesis. The authors suggested that the mechanism that underlies the quiescent period (this period is termed the isoelectric window) following strong shocks, of strength near the upper limit of vulnerability or the defibrillation threshold, DFT, is due to “tunnel propagation” of postshock activations through intramural excitable areas. Fig. 4A demonstrates this concept for biphasic shocks delivered by external electrodes. Formation of virtual electrode polarization, quick re-excitation, and synchronous repolarization took place sequentially. However, a wavefront that originated deep within the wall remained submerged, giving rise to an isoelectric window, until it broke through onto the epicardium and propagated, resulting in intramural reentry.

Fig. 4.

“Tunnel” propagation of activations following defibrillation shocks in rabbit hearts. Arrows indicate direction of propagation. A. Tunnel propagation of a post-shock activation for a 12-V/cm monophasic shock delivered to a paced activation. It resulted in reentry following epicardial breakthrough after an isolelectric window. The model (with external defibrillation electrodes) as well as maps of transmembrane potential at shock-end and at various instances post-shock are shown. Small image of the heart is a transparent rendering of the intramural wavefront (asterisk). B. Submerging of a pre-shock fibrillatory wavefront by a strong biphasic shock delivered from an ICD. The figure shows the model, the fibrillatory pre-shock state (with scroll-wave filaments in pink), and post-shock transmembrane potential maps for two shock strengths at different post-shock timings. In contrast to the 25-V shock, the near-DFT 175-V shock converted the LV excitable area into an intramural excitable tunnel (see triangular arrows in shock-end panel) with no apparent propagation on the epicardium; the wavefront propagatied in it until epicardial breakthrough following the isoelectric window. Modified from.59, 60

This new theory was extended to explain the mechanisms responsible for the existence of isoelectric window following ICD (implantable cardioverter-defibrillator) shocks delivered to the fibrillating heart in a recent article by Constantino et al60 The simulation results demonstrated that the non-uniform field created by ICD electrodes, combined with the fiber orientation and complex geometry of the ventricles, resulted in a postshock excitable region located always in the LV free wall, regardless of preshock state. For near-DFT shocks, this excitable region was converted into an intramural tunnel (Fig. 4B), through which either pre-existing fibrillatory or shock-induced wavefronts propagated during the isoelectric window, emerging as breakthroughs on the LV epicardium. Interestingly, failed defibrillation for near-DFT shocks was found to not always be associated with termination of existing wavefronts and generation of new wavefronts by the shock, as previously believed; instead, wavefronts remained “alive” in the intramural postshock tunnel. Preshock activity within the LV played a significant role in shock outcome: a large number of preshock filaments resulted in an isoelectric window associated with tunnel propagation of pre-existing rather than shock-induced wavefronts. Furthermore, shocks were more likely to succeed if the LV excitable area was smaller. Obtaining such insights into the mechanisms of defibrillation would have been impossible with the use of experimentation alone.

The mechanisms underlying initiation of post-shock arrhythmias with electric shocks under the conditions of global ischemia have also been studied using the same rabbit ventricular bidomain model.61

3.5 Ventricular models incorporating the Purkinje system

The ability to combine a model representation of the Purkinje system with the complex structure of the ventricles provided new opportunities to understand arrhythmogenesis, and specifically, the contribution of Purkinje to the initiation and maintenance of reentry. The first simulation study to incorporate the Purkinje system in a whole-heart model was by Berenfeld and Jalife.62 The authors converted the Auckland canine model into an isotropic finite-difference mesh; the His bundle branches and the Purkinje system were digitized from anatomic data and superimposed over the endocardium. The end points of the Purkinje system in each ventricle were assigned as Purkinje-ventricular junctions (PVJs). The model was used to test the hypothesis that PVJs might be responsible for focal subendocardial activations during complex tachyarrhythmias. Reentrant activity involving muscle and the Purkinje was simulated, demonstrating that the reentry pattern evolved with drifting epicardial breakthroughs and transformed on the endocardium from focal activity to figure-of-eight reentry. The reentry terminated if the Purkinje system was disconnected from the muscle before it reached a relative steady-state. Thus, the study concluded that the Purkinje system may have a double role in the evolution of reentry: first, it is essential at the initial stages of reentry and second, it may lead to intramural reentry, which, once formed, is no longer dependent on the Purkinje system.

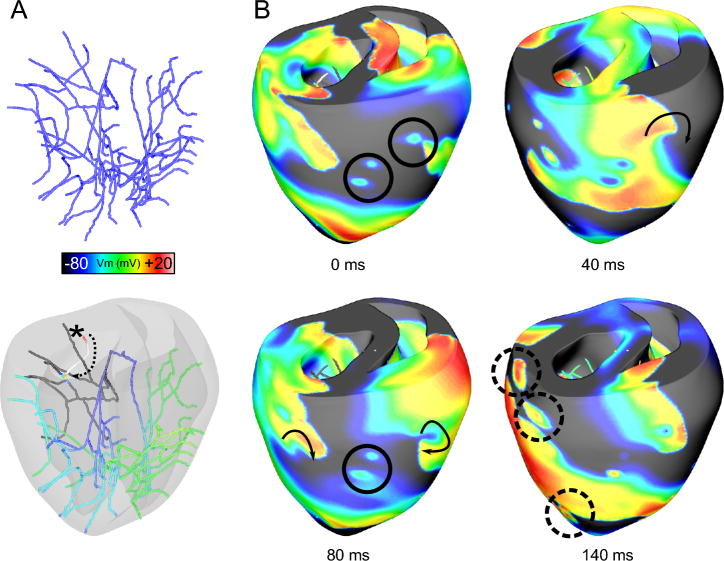

Vigmond and his team recently developed a new sophisticated model of the His-Purkinje system63 and incorporated it in the UCSD rabbit ventricular model. The Purkinje system was modeled as free-running, consisting of one-dimensional fibers (cubic Hermite elements), separated by gap junctions. This representation allows the study not only the role of the network in arrhythmogenesis, but also of its possible involvement in defibrillation and post-shock reentry. Defibrillation studies using this model demonstrated that shocks induced focal activations in the His-Purkinje system64; Purkinje fibers were found responsible for reentry initiation at low shock strengths.55, 65 A recent study by Deo et al66 using this model, focused on examining the conditions for arrhythmogenesis due to EADs originating in Purkinje cells; the latter are known to be are more vulnerable to EADs than ventricular myocytes. The authors demonstrated that a single ectopic beat arising from EAD in the distal Purkinje network can give rise to reentrant arrhythmia; in contrast, EADs in the proximal network were unable to initiate reentry. The contribution of the Purkinje system during arrhythmias67 in a heart where the Purkinje fibers penetrate the ventricular wall and reach the subendocardium, such as in the pig, is illustrated in Fig. 5. The transient local refractoriness created at sites of failed breakthroughs of activity from the penetrating Purkinje fibers is sufficient to split propagating waves and provide epicardial anchor points for transmural scroll waves (Fig. 5B). On the other hand, successful breakthroughs from excited Purkinje terminals act as secondary sources, accelerating existing wavefronts and providing escape routes for activity within Purkinje cells (Fig. 5B). The simulations thus demonstrate that the Purkinje system could both stabilize scroll waves and cause wave breakup.

Fig. 5.

Contribution of the Purkinje system to maintaining arrhythmias. A. Purkinje system without and with the translucent ventricles. In the latter image, membrane voltage is rendered on the Purkinje. Retrograde propagation (*) and the resulting rapid excitation through local branches (dotted arrow) are visible. B. Transmembrane potential maps during arrhythmia (arbitrary times). Failed breakthroughs are highlighted with circles. The transient local refractoriness created at these sites is sufficient to split propagating waves and provide epicardial anchor points for the transmural scroll waves (40ms; arrow). Successful breakthroughs from excited Purkinje terminals act as secondary sources, accelerating wavefronts and providing escape routes for activity within the Purkinje system (140ms; dashed circles).

3.6 Whole-heart models of fluorescent recording in the heart

An interesting application of whole-heart modeling examined the role of photon scattering in signal distortion during optical mapping of cardiac electrical activity. Understanding the sources of this distortion is important for the correct interpretation of fluorescent mapping results and provides a common ground for comparison between experiment and simulation regarding the distribution of transmembrane potential during arrhythmias and defibrillation. Simulation studies68-71 combined the rabbit ventricular model with a 3D model of photon scattering. Model results demonstrated that that distortion in the optical signal as a result of photon scattering is truly a 3D phenomenon, and depends critically upon the geometry of the ventricles, the direction of wavefront propagation, and the specifics of the experimental setup. Fig. 6A presents results from these simulation experiments. The studies found that photon scattering was responsible for optical signal characteristics such as dual-humps, elevated resting potentials, and reduced action potential amplitudes near the reentrant core (Fig. 6A, left), and for underestimation of both the number of surface phase singularities (Fig. 6A, right) and the virtual electrode polarization magnitude on the epicardium.

Fig. 6.

Scroll-wave filaments and phase singularities during arrhythmias. A. The role of photon scattering in optical mapping of arrhythmias and assessment of filament behavior. Left: Time course of the transmembrane potential, Vm and the optical signal, Vopt, during sustained VT in the rabbit heart. Semi-transparent snapshot of Vm distribution, with filaments in purple, is shown, indicating the location where the signals are recorded from. Figure modified from70. Right: Fibrillatory activity with phase singularities on the epicardium in Vm (normalized voltage) and Vopt maps. B. Scroll-wave filaments in the contracting human LV model. Left: Snapshots of filaments at 0ms (initiation of a single spiral wave) and after 4s of reentrant activity (filaments are rendered in red). Right: Filament history. Horizontal lines correspond to individual filaments and start at the time of filament appearance, ending at the time of its disappearance. Long red line represents the initial spiral wave. Modified from81.

4. Cardiac Electromechanics Applications

The coupling between electrical and mechanical events in the heart is an active area of research. Experimental and clinical research has demonstrated that the mechanical activity of the heart, in health and disease, affects cardiac electrophysiology.72 For instance, disturbances in heart rhythm are often due to mechano-electric coupling mechanisms in combination with those associated with remodeling in heart disease. Below we provide a review of the applications of whole heart models in cardiac electromechanics, with a emphasis on simulations of arrhythmogenesis originating from mechanical stimuli and mechano-electric coupling, as well as those focusing on electromechanical dyssynchrony and cardiac resynchronization therapy. Simulation research reviewed here involved the use of the electromechanical models of the type shown in Fig. 1A, with cellular ionic and myofilament models of varying complexity and of different species, where the models have been constrained and validated with experimental measurements, typically strain and hemodynamic data. Studies of cardiac biomechanics only in health and disease, a rich and important field in itself, where whole heart modeling has been broadly used, are outside of the scope of this review.

4.1 Models of stretch-related ventricular arrhythmias

One of the most important mechanism of mechano-electric coupling is the existence of sarcolemmal channels that are activated by mechanical stimuli. A variety of ionic channels activated by changes in cell volume or cell stretch have been identified in cardiac tissue73. Of these, stretch-activated channels (SACs), either non-selective or potassium-selective, have long been implicated as important contributors to the pro-arrhythmic substrate in the heart. The nonuniform distribution of positive myofiber strain (stretching) during mechanical contraction under a variety of pathological conditions could produce, via SAC, a pro-arrhythmic dispersion in electrophysiological properties. SACs have been shown to shorten or lengthen APD of a single myocyte or produce ectopic beats depending on the timing of the mechanical stimulus application relative to the phase of the action potential.72, 74 Uncovering, however, the mechanisms by which SACs contribute to ventricular arrhythmogenesis under a variety of pathological conditions is hampered by the lack of experimental methodologies that can record the 3D electrical and mechanical activity simultaneously and with high spatiotemporal resolution. Thus, computer simulations have emerged as a valuable tool to dissect the mechanisms by which SAC contribute to the ventricular arrhythmogenic substrate.

The first modeling attempts to address the role of SAC in arrhythmogenesis in the whole heart employed pseudo-electromechanical models, in which mechanical activity (and specifically, mechanical impact) was not represented, but its effect on ventricular electrophysiology was, through the recruitment of SAC. The study by Li et al75 examined the mechanisms by which mechanical impact to the pre-cordial region of the chest (commotio cordis) can lead to arrhythmias. The study used the rabbit ventricular model, in which the mechanical impact was “delivered” to (i.e. SAC were assumed open in) a pre-defined (nearly semi-spherical) region of the ventricles during repolarization; the dimension of impact was scaled from baseball impacts in man or in pig experimental models76 to that of rabbit. Despite the simplified representations, this study explained how SAC recruitment in commotio cordis leads to the establishment of ventricular arrhythmias in a narrow time interval during the T-wave.

As ventricular arrhythmia can be initiated by a mechanical impact, it can also be terminated by it.77 A similar pseudo-electromecanical model78 was used to elucidate the mechanisms for termination of arrhythmia by precordial thump under normal and globally-ischemic conditions and to determine the reasons for the decreased efficacy of precordial thump in global ischemia. The study demonstrated that increased mechano-sensitivity of the KATP channels in ischemia lowers precordial thump efficacy. Indeed, simulation results demonstrated that in the normal heart, precordial thump succeeded in terminating VT in 60% of the cases, while this success decreased to 30% in ischemia.

Decoupled mechanical and electrophysiological ventricular rabbit models were employed by Li et al79 to uncover the mechanisms for the experimentally-observed increase in post-shock arrhythmogenesis and elevated DFT in hearts with ventricular dilation80. The study involved a two-step approach: acute dilation was simulated in a model of ventricular mechanics14; the output of the mechanics model (dilated ventricular geometry with corresponding fiber orientation and strain distributions) was used in the electrophysiological model of defibrillation. The research tested the hypothesis that SAC recruitment and deformations in organ shape and fiber architecture lead to increased arrhythmogenesis following electric shocks. Results showed that dilation-induced deformation alone did not increase vulnerability to arrhythmia induction by shocks, while SAC recruitment increased vulnerability by 37%. The heterogeneous activation of SAC was found to be the main reason for increased vulnerability to electric shocks since it caused dispersion of electrophysiological properties in the tissue.

True electromechanical models aimed at examining the mechanisms for mechanically-mediated arrhythmogenesis are only very recent; in fact, the only two ventricular studies in existence were published in 2010. The first is by Keldermann,81 who used an electromechanical model of the human LV to investigate the effect of mechano-electric coupling via SAC on reentrant wave stability. The simulation results revealed that mechano-electric coupling results in the deterioration of stable reentrant waves into turbulent patterns characteristic of VF (Fig. 6B, left). While the initial scroll-wave was found to remain intact, other filaments existed for a short period only (Fig. 6B, right). Filament breakup was due to SAC recruitment in regions of high fiber stretch (away from the spiral core), resulting in voltage-dependent inactivation of sodium channels there, a mechanism for breakup that is different from other known mechanisms for wavebreak such as restitution.42–47 The simulations results thus provided an alternative explanation for the degeneration of VT into VF.

The mechanisms of spontaneous induction of arrhythmias in the diseased heart was the subject of the second electromechanics study, by Jie et al.82 It used a model of the beating rabbit ventricles to gain insight into the role of electromechanical dysfunction in arrhythmogenesis during acute regional ischemia, both in the induction of ventricular premature beats (VPBs), and in their subsequent degeneration into ventricular arrhythmia. The model had CIZ and BZ and represented the electrophysiological and mechanical milieu in the heart at several stages post-occlusion. Dynamic mechano-electrical feedback was represented via spatially and temporally non-uniform membrane currents through SACs, the conductances of which depended on local fiber strain rate, dEff/dt. Fig. 7 presents the essential findings in the study. Fig. 7A illustrates the spatial distribution of strain in the fiber direction in the normal and ischemic ventricles (4min post-occlusion) during systole. Large myofiber strain developed in the ischemic region. Fig. 7B depicts VPB induction in the ischemic heart. VPB originated from two locations around the endocardial LV BZ (arrows in 191-ms inset), propagated intramurally in the apical region (195ms), with the wavefront enclosed by the ellipse making the first breakthrough onto the epicardium, followed by the other wavefront (enclosed by the square), since the latter propagated across a thicker wall portion. Both epicardial breakthrough sites were located close to the anterior ischemic border, consistent with experimental findings.83 Fig. 7C presents action potentials recorded at sites 1 (in BZ) and 2 (in CIZ) in the 191-ms inset. At both sites, cells underwent mechanically-induced delayed afterdepolarization -like events following the paced beat. At site 1 (BZ), the depolarization (solid arrow) evoked spontaneous firing. At site 2, despite the fact that the peak magnitude of sub-threshold depolarization (dashed circle) was larger, no action potential was triggered, due to decreased excitability in CIZ. The VPB wavefront blocked within CIZ (Fig. 7D top), resulting in reentry. The study also dissected the contribution of the electrophysiological factors (the ischemic changes) and mechanical factors (SAC recruitment) to the generation of proarrhythmic substrate (Fig 7D middle and bottom), demonstrating that VPB cannot degrade into reentrant arrhythmia under the conditions of either electrophysiologically (No_SAC) or mechanically (No_Ischemia) -induced pro-arrhythmic substrate alone. The results of this study clearly demonstrate that stretch of ischemic tissue, which loses its ability to contract, by the surrounding normal tissue during contraction leads to mechanically-induced depolarizations, via SAC, in the ischemic region. Mechanically-induced VPBs originated from the ischemic border in the LV endocardium, initiating reentry. The study by Jie et al82 thus provided the first direct evidence that mechanically-induced depolarizations and their spatial distribution within the ischemic region are a possible mechanism by which mechanical activity contributes to the origin of spontaneous arrhythmias.

Fig. 7.

Mechanically-induced arrhythmia in the regionally-ischemic rabbit heart. A. Distribution of myofiber strain (Eff) in the normal and ischemic heart during systole. B. Evolution of a mechanically-induced VPB. C. Vm traces at sites 1 and 2 marked in the 191-ms inset in B. Black arrow and dashed circle denote mechanically-induced depolarization at these sites. Red arrow indicates activation at site 2 by propagation of the mechanically-induced VPB. D. Activation maps for the full model, model No_SAC, and model No_Ischemia during VPB. No_SAC incorporates all the electrophysiological changes in ischemia, but without involvement of SAC, and, thus, without mechanically-induced DADs; external stimuli were applied at the same time and locations where the mechanically-induced VPB originated in the full model (arrows in 191-ms inset in B). No_Ischemia included SAC and thus the spatial distribution of mechanically-induced DADs, but without ischemia-induced electrophysiological changes. Black lines denote conduction block. Asterisk: reentry exit site. Snapshots of transmembrane potentials are also presented for models No_MSC and No_Ischemia. Modified from82.

4.2 Modeling the Electromechanical Activation Sequence and Electromechanical Feedback Mechanisms in the Normal Heart

The mechanical effect of altered cardiac activation sequence has been the subject of intense discussion since asynchronous electrical activation can cause abnormalities in perfusion and pump function. Whole-heart simulations have played an important role in understanding the relationship between the spatiotemporal pattern of electrical activation and the local sequence of mechanical strain, which is of paramount importance in optimizing the sequence of electrical activation in the diseased heart aimed at achieving maximum pump performance. The study by Usyk and McCulloch84 was the first attempt to examine, using a canine heart electromechanical model, the delay between the onsets of electrical activation and fiber shortening (electromechanical delay, EMD) in sinus rhythm and LV pacing, assuming homogeneous excitation-contraction latency throughout the ventricles. This early biophysically-simplified model (the first whole-heart electromechanical model) found EMD to vary throughout the ventricles, with both positive and negative values, indicating the possibility of fiber shortening before depolarization. Following this first effort, electromechanical models have been adjusted and enriched with experimental data.85, 86 The recent study by Gurev et al87 conducted a thorough analysis of the 3D EMD distribution in the rabbit ventricles and it dependence on the loading conditions. To isolate the effect of the pattern of electrical activation on EMD, simulations were executed for sinus rhythm and LV epicardial pacing with homogeneous distribution of excitation-contraction latency; this whole-heart model incorporated the biophysical representation of myofilament dynamics by Rice et al.7 The results revealed that under both activation scenarios, EMD distribution is non-uniform (Fig. 8A). Consistent with experimental results,88 in sinus rhythm EMD is longer at epi- than at endocardium, and is greater near the base than at the apex. Following epicardial pacing, EMD distribution is markedly different and changes with pacing rate. Analysis of the mechanisms revealed that for both electrical activation sequences, late-depolarized regions were characterized with significant myofiber prestretch caused by the contraction of the early-depolarized regions (Figs.8B&C). This prestretch delays myofiber-shortening onset, and results in longer EMD, giving rise to heterogeneous EMD distributions. This study revealed that the loading conditions of the ventricles play an important role in the relationship between electrical and mechanical activation. Understanding the latter relationship is of paramount importance to therapies that employ pacing of the heart, and particularly CRT.

Fig. 8.

Electromechanical delay (EMD) in the rabbit heart for sinus rhythm and epicardial pacing. A. Maps of EMD. Asterisk: pacing site. B. Transmural maps of strain in the fiber direction during systole. Arrows indicate early shortening and prestretching during the isovolumic phase. C. Epicardial fiber strain at four epicardial locations. IVC: isovolumic contraction; EJ: ejection. Modified from87.

The effects of transmural heterogeneity of electrophysiological properties and excitation-contraction coupling in determining LV function was the subject of two simulation studies, which concluded that inclusion of transmural heterogeneity in APD 1) had a profound effect on reducing sarcomere length transmural dispersion during repolarization89 and 2) impacted predominantly local deformation, particularly during early systole.90 These studies illustrate the importance of accounting for physiological complexity in the heart in the modeling efforts to establish the mechanisms governing the normal heart functioning.

The heart achieves an efficient coordinated contraction via a complex network of feedback mechanisms that span the hierarchy of biological complexity. The paper by Niederer et al91 employed a rat LV electromechanical model to explore how feedback loops regulate normal contraction. The relative roles of four tension and deformation feedback mechanisms were examined: length-dependent change in calcium sensitivity, filament overlap, tension-dependent binding of calcium to troponin C, and velocity-dependent cross bridge kinetics. Length-dependent changes in calcium sensitivity and filament overlap, which constitute the Frank-Starling law, were found to be the two dominant regulators of the efficient transduction of work. The absence of either mechanism not only altered the spatial distribution of stress and strain, but also determined the transmural variation in work. These results showed that feedback from muscle length to tension generation at the cellular level is an important control mechanism of pumping efficiency.

4.3 Electromechanical models of cardiac resynchronization therapy in the failing heart

Heart failure patients often exhibit dyssynchrony in contraction, which diminishes the systolic function of the heart. Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), the treatment modality that employs bi-ventricular pacing to re-coordinate the contraction of the heart, is a valuable therapeutic option for such patients. CRT has been shown to improve heart failure symptoms and reduce hospitalization, yet approximately 35% of patients fail to respond to the therapy.92 The poor predictive capability of current approaches to identify potential responders to CRT reflects the incomplete understanding of the complex pathophysiological and electromechanical factors that underlie mechanical dyssynchrony in failing hearts. Simulations of whole-heart electromechanical behavior offer an opportunity to dissect these mechanisms and suggest strategies for optimizing the therapy. Usyk and McCulloch expanded their model84 to incorporate dilation characteristic of heart failure, and demonstrated that it could be used to model CRT under the conditions of left bundle branch block (LBBB). Since a large portion of CRT non-responders are heart failure patients with chronic myocardial infarction, ascertaining the impact of the infarct on cardiac dyssynchrony and resynchronization is an important aspect of optimizing CRT. The simulation study by Kerckhoffs et al93 demonstrated, as anticipated, that increased infarct scar size diminishes the improvement of ventricular function following bi-ventricular CRT in the LBBB failing heart. Further simulation efforts11 are well poised to determine the mechanisms by which infarct location and scar transmurality each contribute to diminished CRT efficacy,94 and the insights used to predict an optimal placement of the LV pacing electrode in patients with myocardial infarction.

A recent study by Kerckhoffs et al95 focused the CRT modeling effort towards assessing the sensitivity, to cardiac dysfunction, of various indices of mechanical dyssynchrony used to quantify contractile dysfunction in patients, such as circumferential uniformity ratio estimate (CURE),96 internal stretch fraction (ISF),97 and the percentile range of time to peak shortening (WTpeak).97 CURE and ISF are indices that measure distribution of strain magnitudes, whereas WTpeak measures distribution of strain timing. The basic model was the same as in,84 but additionally represented heart failure via dilation, dysynchronous activation (i.e. LBBB), decreased inotropy, and prolonged relaxation. All indices were found sensitive to the activation sequence, but only CURE and ISF were sensitive to the combination of dilation and LBBB, a condition typically present in patients receiving CRT, while WTpeak was not. Thus, CURE and ISF, which measure systolic strain nonuniformity, are better predictors of mechanical dissynchrony because systolic strain nonuniformity, as this modeling study demonstrated, is the dominant determinant of variability in regional work. The results obtained by Kerckhoffs et al95 have also important implications for the emerging field of patient-specific modeling, and in particular, for patient-specific optimization of the LV pacing location for CRT. With geometry and electrical activation sequence, which can be established by a clinical evaluation, being the major determinants of regional cardiac function, and the hard-to-measure material properties playing a minor role, patient-specific simulations could be performed to suggest optimal CRT tailored to the individual. Work in this direction has begun with the development of MRI-based models of cardiac electromechanical function.11, 98

5. Directions for Future Whole-Heart Modeling Research

The reviewed above whole-heart modeling research efforts demonstrates the enormous progress that have been made over the last decade in using whole-heart computational approaches to address both the mechanisms of cardiac dysfunction as well as issues related to the clinical application of therapies for cardiac disease. In the years to come, this role of wholeheart modeling will be broadened and enriched. The advancement of whole-heart modeling will be strongly dependent on concomitant developments in experimental methodologies, which can provide data to constrain, enrich, and validate the models. Of particular importance to wholeheart modeling will be the capability to better resolve the structural features of the intact heart, by developing methods to characterize complex tissue geometries and specifically, structural remodeling in disease, e.g. ischemic cardiomyopathy and fibrosis. The development of unique and sensitive probes for the architecture of cardiac tissues, including tractography and connectivity mapping techniques, will provide a significant impetus to the whole-heart modeling efforts. It will enhance their ability to make significant contributions to the field of cardiac electrophysiology and electromechanics, and to the clinical practice of cardiology.

Below we provide a summary of the future developments we envision for the field of whole-heart simulation and modeling.

Integration of the understanding of cardiac function in health and disease across the physical scales of increasing complexity, from molecule to cell, tissue, the whole heart, and ultimately the patient. The essential role of whole-heart modeling and simulation will be broadened to include not only assisting hypothesis-driven research, but also providing the framework for the unification of diverse experimental findings. The goal is to provide a quantitative understanding of the mechanisms of cardiac rhythm and pump dysfunctions, with the heart as a global dynamic system, and at all levels, from the genes to the patient. This involves bridging the spatial and temporal scales, from nanometer to meter, and from nanoseconds to minutes or hours. Furthermore, to address the contribution of various factors to the origin of cardiac dysfunction, simulations will increasingly become multi-physics. For instance, in examining the mechanisms for arrhythmogenesis in cardiac disease, factors stemming from soft tissue mechanics and fluid dynamics will need to be accounted for. Finally, the relationship between structure and function at the various levels of structural complexity in the heart will have to be incorporated in a comprehensive manner.

Providing the formal and quantitative means of extrapolating mechanisms from animal models of cardiac dysfunction to the human heart. While this role of whole-heart simulations and computational approaches is strongly linked the one described above, it also has its own unique challenge: the lack of availability of human data, at any level of structural complexity, that can inform and constrain the models of human cardiac arrhythmia mechanisms or contractile dysfunction. Future simulations and whole-heart modeling approaches will thus have to play a major role in integrating knowledge, albeit scarce, about the human heart with insights obtained from animal studies, in order to be able to extrapolate mechanisms that could be at work in the human heart, in both health and disease.

Serving as a testbed for new therapies and a vehicle for the development of new diagnostic modalities. The augmented role of cardiac modeling in the development of new therapies for cardiac dysfunction and diagnostic modalities arises from its function as the framework that unifies diverse cardiac electrophysiology and electromechanics insight. Multi-scale, multi-physics models that incorporate electromechnical and structural remodeling in cardiac disease will serve as the first line of screening of new therapies and approaches, including pharmacological interventions. Furthermore, riding on the heels of diagnostic developments that stem from mathematical modeling and simulation, such as electrocardiographic imaging,99 will be new approaches to patient screening and diagnosis.

Patient-specific approaches to analysis and treatment of heart rhythm disturbances and contractile dysfunction. As imaging modalities are becoming more prevalent in patient evaluation, a wealth of patient-specific cardiac structural and functional data is rapidly becoming available. Today, we stand at the threshold of a new era in cardiac modeling and simulation: anatomically-detailed, tomographically reconstructed models of patient hearts are beginning to be developed that have the potential to integrate patient-specific information from the ion channel to the electromechanical interactions in the intact heart. The use of models in tailor-made diagnosis, treatment planning, and prevention of sudden cardiac death will slowly become a reality. Currently, researchers face numerous obstacles in the development of patient-specific heart models, among which the low resolution of the in-vivo heart scans, the current impossibility of acquiring patient-specific fiber orientation, issues with segmenting out structural remodeling in the patient heart such as the infarct, and finally, difficulties in validating these models with ECGs and patient electrophysiological data. Furthermore, the advancement of algorithms and approaches for high-speed simulations (see next) is of critical importance in order for these approaches to become clinical reality.

New emphasis on the development of modeling tools and techniques. Such emphasis will result in the ability to incorporate fine-grained cardiac structural and functional data, and will enable models to run in a period of time appropriate for clinical applications. As described in the Online Supplement, research efforts are being invested in dramatically improving the parallel scalability of biophysically-detailed whole-heart models; new data demonstrate that a single human heartbeat in such a model can be simulated in only 4min. Furthermore, the best approaches to modularize and interface multiple model levels, as well as to preserve and curate model and data in easy-access repositories need to be determined.

Development of interfaces that allow model utilization by non-experts. The development and use of electrophysiological and electromechanics models of the heart currently requires a great amount of expertise in a number of different fields such as numerical analysis, computer science, cardiac electrophysiology and mechanics, medicine, and lately, image processing. Taking advantage, by the broader community, of the new developments in whole-heart modeling and the ability of the latter to integrate data from different scales remains, however, a challenge. Despite some efforts to open-source models to the community by the original developers, the process has been hampered by lack of adequate training of the research community in utilizing currently available computational tools, models and visualization; by time-consuming and cumbersome infrastructures; and by interfaces, if any, that are outright unfriendly. Efforts must be supported to develop user-friendly web-based computing infrastructure for research in heart electrophysiology and electromechanics that could serve as a virtual research environment for the entire community. This infrastructure should allow the direct input of cardiac structural imaging data and the ability to easily assemble models with the click of the mouse.

Biophysically-based computational modeling of the heart, applied to human heart physiology and the diagnosis and treatment of cardiac disease, will revolutionize twenty-first century cardiac research and the field of cardiology. The future that awaits us is exciting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the help of her doctoral students Jason Constantino, Hermenegild Arevalo and Jason Bayer in the preparation of the manuscript, and the significant contribution of Dr. Gernot Plank, Medical University of Graz, Austria, to the Online Supplement.

Sources of Funding

Supported by NIH grant R01-HL082729 and NSF grant CBET-0933029.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- PDE

Partial Differential Equation

- ODE

Ordinary Differential Equation

- MR

Magnetic Resonance

- DT

Diffusion Tensor

- APD

Action Potential Duration

- VF

Ventricular Fibrillation

- VT

Ventricular Tachycardia

- CV

Conduction Velocity

- ICD

Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator

- DFT

Defibrillation Threshold

- PVJ

Purkinje-ventricular Junction

- CRT

Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy

- EAD

Early Afterdeoplarization

- SAC

Stretch Activated Channels

- BZ

Border Zone

- CIZ

Central Ischemic Zone

- EMD

Electromechanical Delay

- LBBB

Left Bundle Branch Block

Footnotes

Disclosure

The author is a co-founder of CardioSolv LLC. CardioSolv was not involved in this research.

In October 2010, the average time from submission to first decision for all original research papers submitted to Circulation Research was 13.9 days.

References

- 1.Cohen J. Mathematics Is Biology's Next Microscope, Only Better; Biology Is Mathematics' Next Physics, Only Better. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noble D. Cardiac action and pacemaker potentials based on the Hodgkin-Huxley equations. Nature. 1960;188:495–497. doi: 10.1038/188495b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamming R. Introduction to applied numerical analysis. McGraw-Hill Companies; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plank G, Zhou L, Greenstein JL, Cortassa S, Winslow RL, O'Rourke B, Trayanova NA. From mitochondrial ion channels to arrhythmias in the heart: computational techniques to bridge the spatio-temporal scales. Philos Transact A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2008;366:3381–3409. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2008.0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LeGrice IJ, Smaill BH, Chai LZ, Edgar SG, Gavin JB, Hunter PJ. Laminar structure of the heart: ventricular myocyte arrangement and connective tissue architecture in the dog. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:H571–582. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.2.H571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noble D, Rudy Y. Models of cardiac ventricular action potentials: iterative interaction between experiment and simulation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond A. 2001;359:1127–1142. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rice JJ, Wang F, Bers DM, de Tombe PP. Approximate model of cooperative activation and crossbridge cycling in cardiac muscle using ordinary differential equations. Biophys J. 2008;95:2368–2390. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.119487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niederer SA, Hunter PJ, Smith NP. A quantitative analysis of cardiac myocyte relaxation: a simulation study. Biophys J. 2006;90:1697–1722. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.069534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerckhoffs RCP, Healy SN, Usyk TP, McCulloch AD. Computational Methods for Cardiac Electromechanics. Proceedings of the IEEE. 2006;94:769–783. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerckhoffs RC, Neal ML, Gu Q, Bassingthwaighte JB, Omens JH, McCulloch AD. Coupling of a 3D finite element model of cardiac ventricular mechanics to lumped systems models of the systemic and pulmonic circulation. Ann Biomed Eng. 2007;35:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s10439-006-9212-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurev V, Lee T, Constantino J, Arevalo H, Trayanova NA. Models of cardiac electromechanics based on individual hearts imaging data: Image-based electromechanical models of the heart. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. doi: 10.1007/s10237-010-0235-5. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arts T, Reneman RS, Veenstra PC. A model of the mechanics of the left ventricle. Ann Biomed Eng. 1979;7:299–318. doi: 10.1007/BF02364118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bovendeerd PH, Arts T, Huyghe JM, van Campen DH, Reneman RS. Dependence of local left ventricular wall mechanics on myocardial fiber orientation: a model study. J Biomech. 1992;25:1129–1140. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(92)90069-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vetter FJ, McCulloch AD. Three-dimensional analysis of regional cardiac function: a model of rabbit ventricular anatomy. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1998;69:157–183. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(98)00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens C, Remme E, LeGrice I, Hunter P. Ventricular mechanics in diastole: material parameter sensitivity. J Biomech. 2003;36:737–748. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00452-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Legrice IJ, Hunter PJ, Smaill BH. Laminar structure of the heart: a mathematical model. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H2466–2476. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.5.H2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vadakkumpadan F, Arevalo H, Prassl AJ, Chen J, Kickinger F, Kohl P, Plank G, Trayanova N. Image-based models of cardiac structure in health and disease. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2009;2:489–506. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bishop MJ, Plank G, Burton RA, Schneider JE, Gavaghan DJ, Grau V, Kohl P. Development of an anatomically detailed MRI-derived rabbit ventricular model and assessment of its impact on simulations of electrophysiological function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H699–718. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00606.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helm P, Beg M, Miller M, Winslow R. Measuring and mapping cardiac fiber and laminar architecture using diffusion tensor MR imaging. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1047:296–307. doi: 10.1196/annals.1341.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helm PA, Tseng HJ, Younes L, McVeigh ER, Winslow RL. Ex vivo 3D diffusion tensor imaging and quantification of cardiac laminar structure. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:850–859. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prassl AJ, Kickinger F, Ahammer H, Grau V, Schneider JE, Hofer E, Vigmond EJ, Trayanova NA, Plank G. Automatically generated, anatomically accurate meshes for cardiac electrophysiology problems. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2009;56:1318–1330. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2009.2014243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Onate E, Rojek J, Taylor R, Zienkiewicz O. Finite calculus formulation for incompressible solids using linear triangles and tetrahedra. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering. 2004;59:1473–1500. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trayanova N, Eason J, Aguel F. Computer simulations of cardiac defibrillation: a look inside the heart. Computing and Visualization in Science. 2002;V4:259–270. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vigmond EJ, Hughes M, Plank G, Leon LJ. Computational tools for modeling electrical activity in cardiac tissue. J Electrocardiol. 2003;36 (Suppl):69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simelius K, Nenonen J, Horacek M. Modeling cardiac ventricular activation. Int J Bioelectromag. 2001;3:51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lorange M, Gulrajani RM. A computer heart model incorporating anisotropic propagation. I. Model construction and simulation of normal activation. J Electrocardiol. 1993;26:245–261. doi: 10.1016/0022-0736(93)90047-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sampson KJ, Henriquez CS. Electrotonic influences on action potential duration dispersion in small hearts: a simulation study. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005:289. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00507.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colli Franzone P, Pavarino LF, Scacchi S, Taccardi B. Modeling ventricular repolarization: effects of transmural and apex-to-base heterogeneities in action potential durations. Math Biosci. 2008;214:140–152. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panfilov A, Keener JP. Re-entry in an anatomical model of the heart. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals. 1995;5:681–689. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gray RA, Jalife J. Ventricular fibrillation and atrial fibrillation are two different beasts. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science. 1998;8:65–78. doi: 10.1063/1.166288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panfilov A. Spiral breakup as a model of ventricular fibrillation. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science. 1998;8:57–64. doi: 10.1063/1.166287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winslow RL, Scollan DF, Holmes A, Yung CK, Zhang J, Jafri MS. Electrophysiological modeling of cardiac ventricular function: from cell to organ. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2000;2:119–155. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.2.1.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winslow R, Helm P, Baumgartner W, Peddi S, Ratnanather T, McVeigh E, Miller M. Imaging-based integrative models of the heart: Closing the loop between experiment and simulation. In: Bock G, Goode J, editors. In silico’ simulation of biological processes: Novartis foundation symposium. Vol. 247. ohn Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2002. pp. 129–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xie F, Qu Z, Yang J, Baher A, Weiss JN, Garfinkel A. A simulation study of the effects of cardiac anatomy in ventricular fibrillation. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:686–693. doi: 10.1172/JCI17341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vadakkumpadan F, Rantner L, Tice B, Boyle P, Prassl A, Vigmond E, Plank G, Trayanova N. J Electrocardiol. Vol. 42. 2009. Image-based models of cardiac structure with applications in arrhythmia and defibrillation studies; pp. 157.e151–157.e110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clayton R. Vortex filament dynamics in computational models of ventricular fibrillation in the heart. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science. 2008;18:043127. doi: 10.1063/1.3043805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Samie FH, Berenfeld O, Anumonwo J, Mironov SF, Udassi S, Beaumont J, Taffet S, Pertsov AM, Jalife J. Rectification of the background potassium current: a determinant of rotor dynamics in ventricular fibrillation. Circ Res. 2001;89:1216–1223. doi: 10.1161/hh2401.100818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ten Tusscher KH, Panfilov AV. Reentry in heterogeneous cardiac tissue described by the Luo-Rudy ventricular action potential model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003:284. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00608.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baher A, Qu Z, Hayatdavoudi A, Lamp ST, Yang M-J, Xie F, Turner S, Garfinkel A, Weiss JN. Short-term cardiac memory and mother rotor fibrillation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:180–189. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00944.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ten Tusscher KH, Hren R, Panfilov AV. Organization of ventricular fibrillation in the human heart. Circ Res. 2007;100:e87–101. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.150730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.ten Tusscher KH, Mourad A, Nash MP, Clayton RH, Bradley CP, Paterson DJ, Hren R, Hayward M, Panfilov AV, Taggart P. Organization of ventricular fibrillation in the human heart: experiments and models. Exp Physiol. 2009;94:553–562. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.044065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garfinkel A, Kim YH, Voroshilovsky O, Qu Z, Kil JR, Lee MH, Karagueuzian HS, Weiss JN, Chen PS. Preventing ventricular fibrillation by flattening cardiac restitution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6061–6066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090492697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bernus O, Eyck B, Verschelde H, Panfilov A. Transition from ventricular fibrillation to ventricular tachycardia: a simulation study on the role of Ca2+-channel blockers in human ventricular tissue. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2002;47:4167. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/47/23/304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Echebarria B, Karma A. Mechanisms for initiation of cardiac discordant alternans. The European Physical Journal-Special Topics. 2007;146:217–231. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cherry E, Fenton F. Suppression of alternans and conduction blocks despite steep APD restitution: electrotonic, memory, and conduction velocity restitution effects. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H2332–2341. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00747.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keldermann RH, ten Tusscher KH, Nash MP, Hren R, Taggart P, Panfilov AV. Effect of heterogeneous APD restitution on VF organization in a model of the human ventricles. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 2008:294. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00906.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keldermann RH, ten Tusscher KH, Nash MP, Bradley CP, Hren R, Taggart P, Panfilov AV. A computational study of mother rotor VF in the human ventricles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H370–379. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00952.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]