Abstract

Aim

This study investigated whether Pavlovian extinction occurs during smoking cessation by determining whether experience abstaining from smoking in the presence of cigarette cues leads to decreased probability of lapsing and whether this effect is mediated by craving.

Design

Secondary analyses were carried out with data sets from two studies with correlational/observational designs.

Settings

Data were collected in smokers’ natural environments using ecological momentary assessment techniques.

Participants

61 and 207 smokers who were attempting cessation participated.

Measurements

Multilevel path models were used to examine effects of prior experience abstaining in the presence of available cigarettes and while others were smoking on subsequent craving intensity and the probability of lapsing. Control variables included current cigarette availability, current exposure to others smoking, number of prior lapses, and time in the study.

Findings

Both currently available cigarettes (OR’s = 36.6, 11.6) and the current presence of other smoking (OR’s = 5.0, 1.5) were powerful predictors of smoking lapse. Repeated exposure to available cigarettes without smoking was associated with a significantly lower probability of lapse in subsequent episodes (OR’s = .44, .52). However, exposure to others smoking was not a reliable predictor, being significant only in the smaller study (OR = .30). Craving functioned as a mediator between extinction of available cigarettes and lapsing only in the smaller study and was not a mediator for extinction of others smoking in either study.

Conclusion

This study showed that exposure to available cigarettes is a large risk factor for lapsing, but that this risk can also be reduced over time by repeated exposures without smoking. Smoking cessation interventions should attempt to reduce cigarette exposure (by training cigarette avoidance) but recognize the potential advantage of unreinforced exposure to available cigarettes.

Keywords: Smoking cessation, Extinction, Pavlovian-instrumental transfer

INTRODUCTION

Drug use appears to be an operant behavior that is maintained by the positive or negative reinforcing effects of a drug [1]. However, Pavlov advanced the view that classical (now termed Pavlovian) conditioning is an important mechanism of drug addiction [2], helping to explain why lapses and, ultimately, relapse, are elicited by particular stimuli [3]. More recent research suggests that drug addiction may be the result of a combination of operant and Pavlovian processes [4], such as Pavlovian-instrumental transfer whereby cues associated with receiving a reinforcer increase operant responding associated with the same reinforcer. In the case of smoking, cues previously associated with receiving nicotine, such as available cigarettes, increase the likelihood that the smoker will perform the operant response of smoking. Although much of the evidence for Pavlovian-instrumental transfer is from animal research [5, 6], Talmi and colleagues [7] have demonstrated the effect in humans using functional magnetic resonance imaging. Hogarth, Dickinson and Duka [8] demonstrated transfer effects with smokers reinforced with cigarettes, showing that both the amount of puffing and craving significantly increased when a laboratory conditioned stimulus was presented.

The role of craving

Ferguson and Shiffman [9] have described craving for nicotine as a “final-common-pathway expression of motivations for drug use.” Two types of craving have been identified: background craving, which is experienced as a slowly varying tonic state that slowly drops two days to two weeks after quitting [10–12] and episodic craving, which is typically triggered by smoking-associated stimuli. Craving has been considered a conditioned response to a drug cue [1] that motivates drug seeking behavior [13], an epiphenomenon that has little to do with behavior, and an index of and the extent to which a representation of the outcome of drug taking is activated by a stimulus [8]. Background craving has been shown to be the most bothersome withdrawal symptom in early cessation [14] and to be prospectively associated with relapse after smoking cessation [14–16]. Cue-related episodic craving is also associated with smoking relapse [9].

Extinction has been characterized as a process by which behavior or conditioned responding is eliminated by the withdrawal of reinforcers or unconditioned stimuli [17]. Animal research demonstrates that the association between an unconditioned stimulus and a conditioned stimulus is not unlearned with the passage of time, but that extinction requires exposure to the conditioned stimulus without the unconditioned stimulus [18, 19]. If the same processes apply to smoking cessation, smokers who are never exposed to cigarette cues during cessation will be more likely to smoke when a cigarette cue is inevitably encountered, either because the stimulus has directly led to smoking or because it increased craving, which can then lead to lapsing [9]. Conversely, repeated exposure to cues without smoking should extinguish the associated responses, which should then lead to lower probabilities of lapsing. We consider this possibility by examining the relation of the cumulative number of extinction trials (not smoking when cigarettes are available or others are smoking) to the probability of lapsing in subsequent trials. The role of craving as a mediator between number of extinction trials and lapse risk is also explored.

METHOD

Data sets and samples

Data produced in two ecological momentary assessment (EMA) studies of cigarette smokers who were attempting to quit smoking were used. EMA is a method of collecting data in natural settings by having study participants respond to questions at various times during the day in real-world settings [20, 21].

RESIST Study

The original aim of RESIST was to address a series of research questions concerning the effect of coping strategy use and reversal theory states [22, 23] on success in smoking cessation. Participants were recruited from the Kansas City metropolitan area and participated in the study for about two weeks or until they returned to regular smoking (at least 5 cigarettes a day for 3 consecutive days), whichever occurred first. Fifty-four percent of the sample attended community-based smoking cessation programs and 46% were self-quitters. Table 1 lists the demographic and smoking history characteristics of the sample. More details about the sample and exclusion criteria have been published [24, 25]. Other results of the RESIST study have been reported [26–29].

Table 1.

Characteristics of RESIST and QT Samples

| RESIST | QT | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 61 | 207 |

| % Females | 70% | 58% |

| Average age | 43 | 44 |

| % African American | 8% | 6% |

| % Hispanic/and other | 5% | 2% |

| % White | 87% | 92% |

| Smoking History | ||

| Mean # of cigarettes/day | 24.1 | 26.5 |

| Mean # of years smoking | 22.7 | 23.1 |

| % attending smoking cessation program | 54% | 100% |

| Episodes | ||

| # resists | 1,377 | 3,588 |

| # lapses | 239 | 1,551 |

| # random assessments | 3,652 | 22,003 |

| % Quit for 24 hours | 93% | 100% |

| % Experienced lapses | 66% | 66% |

Quit (QT) Study

The original aims of the QT study included analysis of circumstances surrounding initial lapse episodes and exploration of the association between these situations and baseline smoking patterns [30–33]. All participants attended a smoking cessation program that was part of the study protocol. Participants were recruited from the Pittsburgh metropolitan area and participated in the study for two weeks prior to quitting smoking and for about four weeks after quitting or until they returned to regular smoking (at least 5 cigarettes a day for 3 consecutive days), whichever occurred first. Table 1 lists the characteristics of the sample. More details about the sample and procedures have been previously published [10, 34–38].

Procedures

Both studies used a computer-based electronic diary (ED) system developed by Shiffman and his associates. The ED system was implemented on a PSION Organizer II LZ 64 (PSION, Ltd., London, England), a hand-held computer running software that was developed specifically for each project. Assessment sessions could be either self-initiated or prompted. Participants were instructed to self-initiate assessments immediately after they experienced a lapse, defined as any smoking, even a puff, and immediately after a resist, defined as an episode during which they were tempted to smoke but did not. In addition to the self-initiated assessments, participants responded to randomly prompted assessments about 5 times per day, which were used to evaluate times when participants were not particularly tempted to smoke. For all three types of episodes, ED administered a questionnaire to collect data about the current episode. Included were items assessing craving (0–10) whether others were smoking (no, yes, in my group, yes, in my view), and the availability of cigarettes (easily, with difficulty, not available). Others smoking was defined for the subject as anyone smoking in the subject’s environment; no responses were assigned 0; both in my view and in my group were assigned 1. For cigarette availability respondents were instructed to respond according to their subjective assessment of how easily they could obtain a cigarette in the setting. Cigarette availability was dichotomized with easily available assigned 1 and both not available and available with difficulty assigned 0. Although one needs a cigarette in order to lapse, some lapses occurred when cigarettes were available with difficulty, such as after purchasing a cigarette or knocking on a neighbor’s door to request one. Situations during which others were smoking did not necessarily mean that cigarettes were available, especially if the respondent felt unable or unwilling to ask the other smokers for a cigarette.

Data analysis

The data for each subject consist of a series of self-initiated and randomly prompted situations collected over a period of about 2 weeks for the RESIST study and about 4 weeks for the QT study.

Study variables

The outcome variable was whether the respondent reported lapsing (coded as 0/1 for no/yes). The hypothesized mediator was reported craving level (0–10) during the situation. Control variables likely to affect both craving and the probability of lapsing were (a) current cigarette availability (scored as 0/1), (b) currently others smoking, (whether others were currently smoking; scored as 0/1), (c) the log of the time since quitting, and (d) log of the number of prior lapses since quitting. Two hypothesized predictors were constructed to represent extinction trials for available cigarettes and for others smoking. These cumulative extinction variables were constructed in three steps. First, for each situation, we counted the number of times the person had not smoked when the appropriate cue was present during prior situations. Second, because earlier analysis had shown that the relation was nonlinear and better described by the log, we took the log of each cumulative extinction value (1 was added before taking logs to deal with zeros). Third, because the effects of extinction are context-specific [18], the extinction variables were expected to be predictive only in those situations when the cigarette cue was present. Therefore, if the cue (available cigarettes or others smoking) was not present in the episode, the associated extinction variable was set to 0; if the cue was present, it was set to the log of the number of prior non-lapse episodes where a cue was present.

Analyses

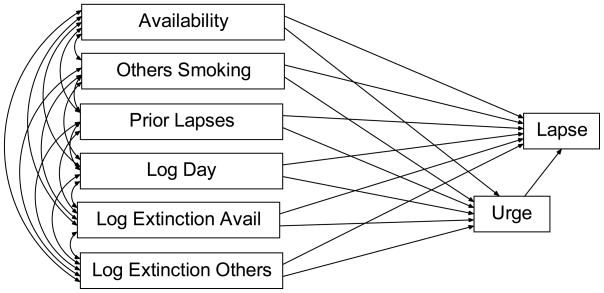

To test the hypothesis that more extinction trials (not smoking in the presence of a cue) would lead to less craving and lower probability of lapsing, a multilevel path model, with a binary outcome (lapse) and a continuous mediator (craving) was fit separately for RESIST and QT data sets. The model is illustrated in Figure 1. To allow for individual differences in the baseline probability of lapsing (i.e., the probability at day 1, given zero values on the other predictors) and in the baseline craving level, a random threshold (for lapsing) and random intercept (for craving) were included in the model. For both datasets, there was significant (p < .01) variation across participants both in the initial probability of lapsing and in the initial reported craving level. The model was fit with maximum likelihood estimation using Mplus, Version 5 [39]. Finally, to demonstrate whether the effect of a predictor on lapsing is mediated by craving level, the indirect effect of the predictor was tested for significance using the Sobel test for mediation [40].

Figure 1.

An illustration of the path model with hypothesized direct effects on lapse probability and mediating effects through craving (urge) level.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for the demographic and smoking history variables for each dataset. Table 2 shows the means, standard deviations, minimum, and maximum values for the predictor variables. These statistics were computed across participants. So, for example, the first line of Table 2 shows that, for the RESIST study, the mean across participants for lapses, a binary variable, is .05, indicating an average of 5% of the observations consists of lapses. With respect to individual participants, some had no lapses, as shown by the minimum of 0, whereas the maximum percent of lapses was 29%. Similarly, the mean craving level was 3.25, with a minimum mean value of 0.23 for one participant, and a maximum mean value of 7.40. The mean number of extinction trials for cigarette availability across participants was 14.82, with a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 98. The results for the QT study are shown in the lower half of the table.

Table 2.

Mean, SD, Minimum, and Maximum for Study Variables across Participants.

| Resist Study (N = 61 Participants) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

| Lapse (0/1) | .05 | .06 | 0 | 0.29 |

| Cigarette Availability (0/1) | .22 | .25 | 0 | 0.94 |

| Others Smoking (0/1) | .15 | .15 | 0 | 0.56 |

| Craving Level (0-10) | 3.25 | 1.81 | 0.23 | 7.40 |

| Cumulative Prior Lapses | 4.82 | 5.05 | 0 | 21.00 |

| Total Days after Quit | 13.11 | 4.23 | 3 | 18.00 |

| Extinction Cig Availability | 14.82 | 19.99 | 0 | 98.00 |

| Extinction Others Smoking | 10.74 | 11.67 | 0 | 41.00 |

| QT Study (N = 207 Participants) | ||||

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

| Lapse (0/1) | .06 | .10 | 0 | 0.47 |

| Cigarette Availability (0/1) | .39 | .33 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Others Smoking (0/1) | .12 | .12 | 0 | 0.59 |

| Craving Level (0–10) | 2.86 | 2.26 | 0 | 10.00 |

| Cumulative Prior Lapses | 9.03 | 15.43 | 0 | 127.00 |

| Total Days after Quit | 24.05 | 7.02 | 2 | 43.00 |

| Extinction Cig Availability | 43.21 | 44.42 | 0 | 197.00 |

| Extinction Others Smoking | 12.84 | 13.96 | 0 | 69.00 |

Table 3 shows, for each dataset, the correlations of the predictor variables used in the path models. The correlations are generally moderate to small, except for those of current availability and extinction of availability, and currently others smoking and extinction in the presence of others smoking, which are fairly large. However, the condition index and variance proportions (collinearity diagnostics, given in SPSS) indicated that collinearity was not a problem for either dataset. This is also evident by the relatively small standard errors found for these variables in the path analysis below (the main consequence of collinearity is inflation of the standard errors).

Table 3.

Correlations of Predictor Variables.

| Resist Study (N = 61 Participants) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Avail | Others | Crave | Prior | Days | ExtAv | ExtOth |

| Cigarette Availability | 1.00 | ||||||

| Others Smoking | .42 | 1.00 | |||||

| Craving Level | .15 | .26 | 1.00 | ||||

| Log Cum Prior Lapses | .24 | .10 | .12 | 1.00 | |||

| Log Days after Quit | −.07 | −.00 | −.31 | .31 | 1.00 | ||

| Extinction Log Avail | .87 | .38 | .09 | .32 | .05 | 1.00 | |

| Extinction Log Others | .41 | .87 | .07 | .15 | .10 | .46 | 1.00 |

| QT Study (N = 207 Participants) | |||||||

| Variable | Avail | Others | Crave | Prior | Days | ExtAv | ExtOth |

| Cigarette Availability | 1.00 | ||||||

| Others Smoking | .29 | 1.00 | |||||

| Craving Level | .09 | .12 | 1.00 | ||||

| Log Cum Prior Lapses | .19 | .08 | .17 | 1.00 | |||

| Log Days after Quit | .04 | −.01 | −.26 | .31 | 1.00 | ||

| Extinction Log Avail | .92 | .23 | .03 | .23 | .21 | 1.00 | |

| Extinction Log Others | .28 | .90 | .09 | .12 | .09 | .27 | 1.00 |

Effects on lapsing

Table 4 shows results for the multilevel path model illustrated in Figure 1. The first section of the table shows results for the direct effects of the various predictors on the probability of lapsing. In both the RESIST and QT studies, measures of current cigarette availability and currently others smoking had large positive effects on the probability of lapsing. For example, for the RESIST study, the odds ratio of a lapse when cigarettes were currently available is 36.60, more than 36 times higher in the presence of cigarettes than in the absence. The craving level also has a significant positive effect in both studies. The log cumulative prior lapses had small positive effects, but it is only significant in the QT study. The log days since quitting had a positive effect, which means that the probability of lapsing, given a temptation, increased with days in the study, more quickly at first and more slowly later (i.e., a decelerating curve).

Table 4.

Parameter Estimates for the Multilevel Path Model

| Within Participants | Effects on Lapse Probability |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Resist Study | QT Study | ||||||||

| Est | SE | OR | 95% CI for OR | p | Est | SE | OR | 95% CI for OR | p | |

| Current Cigarette Availability (0/1) | 3.60 | 0.32 | 36.60 | (19.55, 68.53) | <.01 | 2.45 | 0.18 | 11.59 | (8.14, 16.49) | <.01 |

| Currently Others Smoking (0/1) | 1.61 | 0.36 | 5.00 | (2.47, 10.13) | <.01 | 0.42 | 0.19 | 1.52 | (1.05, 2.21) | 0.02 |

| Craving Level (0–10) | 0.66 | 0.05 | 1.93 | (1.75, 2.13) | <.01 | 0.57 | 0.02 | 1.77 | (1.70, 1.84) | <.01 |

| Log Cumulative Prior Lapses (+1) | 0.33 | 0.58 | 1.39 | (0.45, 4.34) | 0.57 | 0.40 | 0.18 | 1.49 | (1.05, 2.12) | 0.03 |

| Log Days after Quit | 1.69 | 0.52 | 5.42 | (1.96, 15.02) | <.01 | 2.28 | 0.26 | 9.78 | (5.87, 16.27) | <.01 |

| Log Extinction Availability (+1) | −0.83 | 0.33 | 0.44 | (0.23, 0.83) | 0.01 | −0.66 | 0.14 | 0.52 | (0.39, 0.68) | <.01 |

| Log Extinction Others Smoking (+1) | −1.20 | 0.38 | 0.30 | (0.14, 0.63) | <.01 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 1.26 | (0.88, 1.79) | 0.21 |

| Within Participants | Effects on Craving |

|||||||||

| Resist Study | QT Study | |||||||||

| Variable | Est | SE | 95% CI for Est | p | Est | SE | 95% CI for Est | p | ||

| Current Cigarette Availability (0/1) | 1.49 | 0.19 | (1.12, 1.86) | <.01 | 0.40 | 0.08 | (0.24, 0.56) | <.01 | ||

| Currently Others Smoking (0/1) | 0.74 | 0.21 | (0.33, 1.15) | <.01 | 0.65 | 0.10 | (0.45, 0.85) | <.01 | ||

| Log Cumulative Prior Lapses (+1) | 1.60 | 0.22 | (1.17, 2.03) | <.01 | 1.39 | 0.07 | (1.25, 1.53) | <.01 | ||

| Log Days after Quit | −3.46 | 0.14 | (−3.73, −3.19) | <.01 | −2.69 | 0.06 | (−2.81, −2.57) | <.01 | ||

| Log Extinction Availability (+1) | −0.86 | 0.19 | (−1.23, −0.49) | <.01 | −0.09 | 0.06 | (−0.21, 0.03) | 0.14 | ||

| Log Extinction Others Smoking (+1) | −0.23 | 0.22 | (−0.66, 0.20) | 0.3 | 0.15 | 0.10 | (−0.05, 0.35) | 0.12 | ||

Table notes: RESIST study consisted of 61 participants, 5,268 observations; QT study consisted of 207 participants, 27,142 observations.

Of particular interest are the results for the effects of extinction on the probability of lapsing. The second to last line in the top part of Table 4 shows that log extinction of cigarette availability had a significant negative effect in both the RESIST and QT studies. This means that, as the number of occasions in which participants abstained in the presence of cigarettes increased, the probability that they lapsed on the index occasion decreased. Thus, for example, in the RESIST study, the odds of lapsing was 0.44 times smaller after the first 10 successful extinction trials (10 trials = 1 on the log scale). The results for the second extinction variable, others smoking, are not as clear. In particular, there is a significant negative effect on lapsing in the RESIST study (OR = .30), but a small and non-significant positive effect in the QT study. Thus, the RESIST study suggests a possible relationship between exposure to others smoking and subsequent abstinence, but the QT study does not.

Effects on craving

The second section of Table 4 shows the effects of the predictors on self-reported craving level, which serves as a hypothesized mediator, as shown in Figure 1. The effects of current cigarette availability, currently others smoking, and log cumulative prior lapses are all positive and significant (p < .01). Thus, craving was higher when cigarettes were currently available and when others were currently smoking. The effect of log days in the study is significant and negative in both studies: As days passed, the reported craving to smoke decreased more quickly at first and more slowly later (given that craving is a function of log days).

The effects of the extinction variables on craving are not as clear. Extinction in the presence of others smoking appears to have non-significant effects in both studies. Thus, it appears that experience being in the presence of others who are smoking without lapsing does not reduce craving levels in subsequent situations where others are smoking. With respect to extinction when cigarettes were available, a negative effect appears in both studies, but it is significant only in the RESIST study (p < .01). Thus, it is not clear whether extinction in the presence of cigarettes reduces craving, whereas it is clear that it reduces the probability of lapsing, as shown in the top part of the table.

Mediation

The results show that there are clearly direct and indirect effects of current cigarette availability and currently others smoking on the probability of lapsing. For example, for the RESIST study, current cigarette availability had a direct effect on lapsing of 3.60 (i.e., the log odds ratio estimate) and an effect on craving level of 1.49, both of which are significant. In addition, the effect of craving on the probability of a lapse was 0.66 and was also significant. Thus, for the RESIST study, the indirect effect of current cigarette availability on lapsing through craving is 1.49 × 0.66 = 0.98, which gives a Sobel test statistic of 6.74 with p < .01, and so there is significant mediation. Similarly, currently others smoking and log days in the study also have significant mediated effects. On the other hand, extinction trials for the availability of cigarettes appear to have a mediated effect only for the RESIST study, where the total mediated effect is −0.86 × 0.66 = −0.57, which gives a Sobel statistic of −4.28 (p <.01); however the effect is not significant for the QT study (−.09 ×.57 = −.05, Sobel test statistic = −1.50, p =.13).

In sum, extinction trials when cigarettes were available had both a direct and mediated effect in the RESIST study, but only a direct effect (on lapsing, with no effect on craving) in the QT study. Extinction trials when others were smoking had no mediating effect in either study, and a direct effect only in the RESIST study.

DISCUSSION

We tested the theory-based hypothesis that more extinction trials (not smoking in the presence of a cigarette cue) would lead to lower probability of lapsing. Controlling for other major variables that are likely to affect lapse probability, such as cigarette availability and others smoking in the current episode, current craving level, prior lapses, and length of time in the study, the analyses indicated that the hypotheses were partially supported. In both data sets, the results showed that the more times an individual had previously abstained in the presence of easily available cigarettes, the less likely he/she was to lapse in subsequent episodes where cigarettes were easily available. Experience with abstaining when others were smoking predicted subsequent lapse probability in one of the two data sets.

Under our model, craving was expected to mediate the relationship between extinction trials and lapse probability. Although cumulative exposures to available cigarettes had the hypothesized negative relationship with craving level in both studies, the relationship was significant only for the smaller data set, and only for exposure to available cigarettes, not exposure to others smoking. Thus, cumulative experience abstaining in the presence of easily available cigarettes had direct effects on lapse probability in both studies, but a mediated effect only appeared in one study. A limitation of this study is that we could not distinguish background from cue-induced craving. This could be an important distinction since it is cue-induced craving that would be expected to change in an extinction paradigm.

This study has several limitations. First, the data are observational and correlational. Although the random effects model used in these analyses controls for individual differences in the outcome variables (lapse probability and craving), those with higher extinction scores may be systematically different than those with lower scores on important predictors not in the model. Second, the samples lack ethnic diversity and represent those smokers who could accommodate the study equipment in their lives. Moreover, all the participants in QT and half of those in RESIST sought formal programs to quit smoking, which is not typical of most smokers attempting cessation. Third, our counts of the times participants resisted available cigarettes are based on self-initiated reports about resisted temptations to smoke and randomly assessed nontemptations. We have no data on the number or duration of total exposures to available cigarettes. Finally, the extinction model we tested was a simple one of merely counting the times a participant reported not smoking in the presence of cigarette cues. Other, more complex models may be more appropriate. Because extinction is context dependent [18, 41], taking into account more aspects of the situations in which cigarette cues are encountered and resisted may improve the predictive power of the extinction variable.

Our findings lend partial support for a model of extinction of instrumental responses to conditioned stimuli that have undergone Pavlovian-instrumental transfer. Not smoking in the presence of such stimuli may ultimately weaken the association between cigarette cues and smoking behavior. However, association is not causation and there could be other processes besides or in addition to extinction that explain the reduced likelihood of lapsing after repeated unreinforced exposure to the presence of cigarettes. One explanation, for example, is that smokers gain practice in resisting potent smoking-related cues. Most smoking cessation protocols include recommendations to reduce exposure to conditioned stimuli by getting rid of cigarettes, lighters, ashtrays, and by staying away from other smokers. Indeed, a number of studies, including this one have shown that the presence of cigarette cues in the immediate environments of those attempting abstinence led to increased craving and to increased probability of lapsing in those environments [3, 9, 24, 30].

Overall, the findings indicate that situations in which cigarettes are available clearly imperil smokers’ ability to remain abstinent. But at the same time, repeated non-reinforced exposures may promote a process of cue extinction and/or strengthen smokers’ ability to control their behavior (resist cue-induced lapses) in the presence of strong cigarette cues. Our data show that staying away from smoking cues is good advice as long as the ex-smoker can avoid available cigarettes altogether. But successful experience with not smoking in the presence of available cigarettes may ultimately improve long-term success. It is likely that return to use of other addictive substances is similarly cue-dependent. Overall, our study suggests that smoking cessation programs should include both stimulus control techniques (cigarette avoidance) and practice resisting available cigarettes in natural environments to ensure long-term abstinence.

Acknowledgments

Data collection for the QT project was supported by grants DA06084 and DA10605 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Saul Shiffman, principal investigator. Data collection for the RESIST project was supported by grant NR03145 from the National Institute of Nursing Research, Kathleen A. O’Connell, principal investigator. The authors acknowledge Tom Weishaar for editorial assistance.

Data collection for the RESIST project was supported by grant NR03145 from the National Institute of Nursing Research, Kathleen A. O’Connell, principal investigator. Data collection for the QT project was supported by grants DA06084 and DA10605 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Saul Shiffman, principal investigator. Saul Shiffman consults exclusively for Glaxo-SmithKline Consumer Healthcare, which manufactures smoking cessation products, and is also a founder of invivodata, inc., which provides electronic diaries for clinical trials. Neither Kathleen A. O’Connell nor Lawrence T. DeCarlo are affiliated with the tobacco, alcohol, pharmaceutical, or gaming industries nor do they have any other conflicts of interest with respect to the project reported here.

Contributor Information

Kathleen A. O’Connell, Department of Health and Behavior Studies, Teachers College Columbia University, 525 W. 120th Street, New York, NY 10027.

Saul Shiffman, University of Pittsburgh, Department of Psychology, Smoking Research Group, 130 North Bellefield Avenue, Suite 510, Pittsburgh PA 15213.

Lawrence T. DeCarlo, Department of Human Development, Teachers College Columbia University, 525 W. 120th Street, New York, NY 10027.

References

- 1.Glautier S, Remington B. The form of responses to drug cues. In: Drummond DC, Tiffany ST, Glautier S, Remington B, editors. Addictive behaviour: Cue exposure theory and practice. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 1995. pp. 21–46. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pavlov I. Conditioned reflexes. New York: Oxford University Press; 1927. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niaura RS, Rohsenow DJ, Binkoff JA, Monti PM, Pedraza M, Abrams DB. Relevance of cue reactivity to understanding alcohol and smoking relapse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:133–52. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belin D, Jonkman S, Dickinson A, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Parallel and interactive learning processes within the basal ganglia: Relevance for the understanding of addiction. Behavioural Brain Research. 2009;199:89–102. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corbit LH, Janak PH, Balleine BW. General and outcome-specific forms of Pavlovian-instrumental transfer: The effect of shifts in motivational state and inactivation of the ventral tegmental area. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;26:3141–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rescorla RA, Solomon RL. Two-process learning theory: Relationships between Pavlovian conditioning and instrumental learning. Psychological Review. 1967;74:151–82. doi: 10.1037/h0024475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talmi D, Seymour B, Dayan P, Dolan RJ. Human pavlovian-instrumental transfer. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:360–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4028-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hogarth L, Dickinson A, Duka T. The associative basis of cue-elicited drug taking in humans. Psychopharmacology. 2010;208:337–51. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1735-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferguson SG, Shiffman S. The relevance and treatment of cue-induced cravings in tobacco dependence. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:235–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shiffman S, Engberg JB, Paty JA, Perz WG, Gnys M, Kassel JD, et al. A day at a time: Predicting smoking lapse from daily urge. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:104–16. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piasecki TM, Niaura R, Shadel WG, Abrams D, Goldstein M, Fiore MC, et al. Smoking withdrawal dynamics in unaided quitters. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:74–86. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.West R, Schneider N. Craving for cigarettes. British Journal of Addiction. 1987;82:407–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb01496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Brien CP, Childress AR, Ehrman R, Robbins SJ. Conditioning factors in drug abuse: Can they explain compulsion? Journal of Psychopharmacology. 1998;12:15–22. doi: 10.1177/026988119801200103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.West R, Hajek P, Belcher M. Time course of cigarette withdrawal symptoms while using nicotine gum. Psychopharmacology. 1989;99:143–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00634470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Killen JD, Fortmann SP. Craving is associated with smoking relapse: findings from three prospective studies. Experimental & Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1997;5:137–42. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.5.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferguson SG, Shiffman S, Gwaltney CJ. Does reducing withdrawal severity mediate nicotine patch efficacy? A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:1153–61. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bouton ME, Swartzentruber D. Sources of relapse after extinction in Pavlovian and instrumental learning. Clinical Psychology Review. 1991;11:123–40. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bouton ME. Context and behavioral processes in extinction. Learning and Memory. 2004;11:485–94. doi: 10.1101/lm.78804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delamater AR. Experimental extinction in Pavlovian conditioning: Behavioural and neuroscience perspectives. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology B: Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 2004;57(B):97–132. doi: 10.1080/02724990344000097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stone AA, Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in behavioral medicine. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1994;16:199–202. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Apter MJ. The experience of motivation: The theory of psychological reversals. London: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Apter MJ. An introduction to reversal theory. In: Apter MJ, editor. Motivational styles in everyday life: A guide to reversal theory. Washington DC: American Psychology Association; 2001. pp. 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Connell KA, Schwartz JE, Gerkovich MM, Bott MJ, Shiffman S. Playful and rebellious states vs negative affect in explaining the occurrence of temptations and lapses during smoking cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6:661–74. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001734049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Connell KA, Hosein VL, Schwartz JE, Leibowitz RQ. How does coping help people resist lapses during smoking cessation? Health Psychology. 2007;26:77–84. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Catley D, O’Connell KA, Shiffman S. Absentminded lapses during smoking cessation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14:73–6. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Connell KA, Gerkovich MM, Bott M, Cook MR, Shiffman S. The effect of anticipatory strategies on the first day of smoking cessation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16:150–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Connell KA, Hosein VL, Schwartz JE. Thinking and/or doing as strategies for resisting smoking. Research in Nursing & Health. 2006;29:533–42. doi: 10.1002/nur.20151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Connell KA, Schwartz JE, Shiffman S. Do resisted temptations during smoking cessation deplete or augment self control resources? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:486–95. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.4.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shiffman S, Paty JA, Gnys M, Kassell JA, Hickcox M. First lapses to smoking: Within-subjects analysis of real-time reports. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:366–79. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shiffman S, Gwaltney CJ, Balabanis MH, Liu KS, Paty JA, Kassel JD, et al. Immediate antecedents of cigarette smoking: An analysis from ecological momentary assessment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:531–45. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shiffman S, Gwaltney CJ. Does heightened affect make smoking cues more salient? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:618–24. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.3.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shiffman S, Balabanis MH, Gwaltney CJ, Paty JA, Gnys M, Kassel JD, et al. Prediction of lapse from associations between smoking and situational antecedents assessed by ecological momentary assessment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;91:159–68. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shiffman S, Gnys M, Richards TJ, Paty JA, Hickcox M, Kassel J. Temptations to smoke after quitting: A comparison of lapsers and maintainers. Health Psychology. 1996;15:455–61. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.6.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shiffman S, Hickcox M, Paty JA, Gnys M, Kassel JD, Richards TJ. Progression from a smoking lapse to relapse: Prediction from abstinence volation effects, nicotine dependence, and lapse characteristics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:993–1002. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shiffman S, Hickcox M, Paty JA, Gnys M, Kassel JD, Richards TJ. The Abstinence Violation Effect following smoking lapses and temptations. Cognitive Therapy & Research. 1997;21:497–523. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shiffman S, Hickcox M, Paty JA, Gnys M, Richards T, Kassel JD. Individual differences in the context of smoking lapse episodes. Addictive Behaviors. 1997;22:797–811. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shiffman S, Hufford M, Hickcox M, Paty JA, Gnys M, Kassel JD. Remember that? A comparison of real-time versus retrospective recall of smoking lapses. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:292–300. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.65.2.292.a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus Users’ Guide. 5. Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- 40.MacKinnon DP, Warsi G, Dwyer JH. A simulation study of mediated effect measures. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1995;30:41–62. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3001_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bouton ME. Context and ambiguity in the extinction of emotional learning - implications for exposure therapy. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 1988;26:137–49. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(88)90113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]