Abstract

The colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1) receptor is a protein-tyrosine kinase that regulates cell division, differentiation, and development. In response to phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), the CSF-1 receptor is subject to proteolytic processing. Use of chimeric receptors indicates that the CSF-1 receptor is cleaved at least two times, once in the extracellular domain and once in the transmembrane domain. Cleavage in the extracellular domain results in ectodomain shedding while the cytoplasmic domain remains associated with the membrane. Intramembrane cleavage depends on the sequence of the transmembrane domain and results in the release of the cytoplasmic domain. This process can be blocked by γ-secretase inhibitors. The cytoplasmic domain localizes partially to the nucleus, displays limited stability, and is degraded by the proteosome. CSF-1 receptors are continuously subject to down-modulation and regulated intramembrane proteolysis (RIP). RIP is stimulated by granulocyte-macrophage-CSF, CSF-1, interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-4, lipopolysaccharide, and PMA and may provide the CSF-1 receptor with an additional mechanism for signal transduction.

The colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1) receptor is a protein-tyrosine kinase that regulates the proliferation and differentiation of monocytes and macrophage precursors (6, 65). CSF-1 receptor-deficient mice have strongly reduced levels of macrophages and defects in bone formation, development of the mammary gland, and the formation of the placenta (15). CSF-1 receptors have also been implicated in a variety of malignancies (32, 33).

The CSF-1 receptor is composed of an extracellular ligand-binding domain, a single transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic domain (28). The cytoplasmic domain is divided into a juxtamembrane region, a kinase domain that is separated into two parts by a kinase insert, and a carboxy-terminal tail (see Fig. 4A). The initial steps in CSF-1-dependent signal transduction are relatively well understood. Ligand binding results in receptor dimerization, which is followed by autophosphorylation on a number of tyrosine residues, including tyrosines 697, 706, 721, 807, and 973 (52, 70, 72, 73, 76). Phosphorylation on tyrosine 807 contributes to activation of the catalytic domain (58, 74). The other phosphorylated tyrosine residues act as binding sites for SH2 domain-containing signaling proteins, including Src, Grb2, STAT1, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, Mona, phospholipase C-γ2 (PLC-γ2), and c-Cbl (1, 4, 5, 42, 49, 52, 73, 76). These signaling proteins are activated directly or indirectly as a consequence of binding to the receptor, and they initiate cascades of events that make it possible for the cell to respond to the presence of CSF-1 (6).

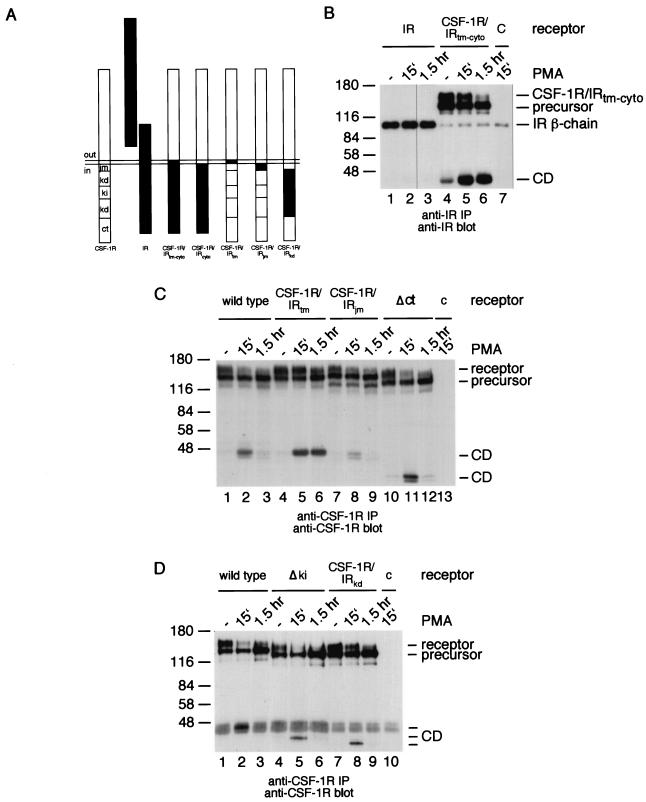

FIG. 4.

Down-modulation of a CSF-1R/IR chimera. (A) Domain swapping was carried out using the wild-type murine CSF-1 receptor (CSF-1R) and the human insulin receptor (IR). CSF-1R/IRtm-cyto contains the extracellular domain of the CSF-1 receptor and the transmembrane and intracellular region of the insulin receptor. CSF-1R/IRcyto contains the extracellular and the transmembrane domains of the CSF-1 receptor and the intracellular region of the insulin receptor. In CSF-1R/IRtm the CSF-1 receptor transmembrane domain has been replaced with the insulin receptor transmembrane domain. In CSF-1R/IRjm the CSF-1 receptor juxtamembrane region has been replaced with the insulin receptorjuxtamembrane region. In CSF-1R/IRkd the CSF-1 receptor kinase domain has been replaced with the insulin receptor kinase domain. tm = transmembrane domain; jm = juxtamembrane region; kd = kinase domain; ki = kinase insert; ct = carboxy-terminal region. (B) 293 cells were transfected with expression constructs for the wild-type insulin receptor (IR; lanes 1 to 3) or the CSF-1R/IRtm-cyto chimera (lanes 4 to 7), or with a control plasmid (lane 7). Cells were left untreated (lanes 1 and 4) or were stimulated with PMA for 15 min (lanes 2, 5, and 7) or for 1.5 h (lanes 3 and 6). The cells were lysed and analyzed by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting with an antiserum against the insulin receptor β chain. (C) 293 cells were transiently transfected with expression constructs for the wild-type CSF-1 receptor (lanes 1 to 3), the CSF-1R/IRtm chimera (lanes 4 to 6), the CSF-1R/IRjm chimera (lanes 7 to 9), the Δct CSF-1 receptor mutant (lanes 10 to 12), or a control plasmid (lane 13). Control cells (lanes 1, 4, 7, and 10) and cells treated with PMA for 15 min (lanes 2, 5, 8, 11, and 13) or 1.5 h (lanes 3, 6, 9, and 12) were lysed and analyzed by anti-CSF-1 receptor immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting. (D) 293 cells were transiently transfected with expression constructs for the wild-type CSF-1 receptor (lanes 1 to 3), the Δki CSF-1 receptor mutant (lanes 4 to 6), the CSF-1R/IRkd chimera (lanes 7 to 9), or a control plasmid (lane 10). Control cells (lanes 1, 4, and 7) and cells stimulated with PMA for 15 min (lanes 2, 5, 8, and 10) or for 1.5 h (lanes 3, 6, and 9) were lysed and analyzed by anti-CSF-1 receptor immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting.

Recently, a novel mechanism for signal transduction has been discovered, named regulated intramembrane proteolysis (RIP) (9). It involves proteolytic processing of membrane proteins and is characterized by release of the extracellular domain, followed by intramembrane cleavage and release of the cytoplasmic domain into the cytosol. Upon their release, cytoplasmic domains have been shown to move to the nucleus, where they can regulate transcription of specific genes (71). This process was first implicated in the processing of the sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP), Notch, and the amyloid precursor protein (APP). RIP is thought to occur at the cell surface, in endosomes, in the Golgi apparatus, and in the endoplasmic reticulum (9).

Since its discovery in Drosophila melanogaster about a century ago, the Notch signaling pathway has been characterized in great detail (45, 75). Notch is a type I transmembrane receptor that is important in regulating cell fate determination during development. Notch signaling is activated upon binding to the membrane-bound DSL ligands (39). Following ligand binding, the ectodomain of Notch is released into the extracellular environment by the tumor necrosis factor alpha-converting enzyme (TACE) (7). The remaining membrane-associated intracellular domain is cleaved within the transmembrane domain by γ-secretase (20, 51, 64). Following its release from the membrane, the cytoplasmic domain of Notch moves to the nucleus, where it interacts with members of the CSL family of transcription factors and initiates transcription of specific target genes (38).

γ-Secretase is composed of four proteins, including presenilin 1 (PS1) or PS2, aph-1, aph-2/nicastrin, and pen-2 (23). The PSs are thought to represent the catalytic subunits that mediate the cleavage of peptide bonds present in the context of a transmembrane region. PSs contain eight transmembrane domains, with catalytic aspartic acid residues present within transmembrane domains 6 and 7 (21, 77). Dominant-negative PS mutants and chemical inhibitors of γ-secretase have been shown to inhibit intramembrane cleavage and cytoplasmic domain release from a variety of membrane proteins (46, 47, 61).

There is evidence in the literature that suggests that the CSF-1 receptor may be subject to RIP. Stimulation of macrophage precursors with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) causes CSF-1 receptor down-modulation and ectodomain shedding (3, 13, 14, 22, 27). In this study, we have analyzed proteolytic processing of the CSF-1 receptor by following the fate of its cytoplasmic domain. Our results show that the receptor is subject to at least two cleavage events. The first event results in release of the extracellular domain while the cytoplasmic domain remains associated with the membrane. The second event, which is mediated by γ-secretase, results in the release of the cytoplasmic domain from the membrane. Chimeric receptors were used to show that each cleavage event is dependent on the sequence of specific regions of the receptor. The cytoplasmic domain appears to localize in part to the nucleus, and it is eventually degraded by the proteosome. This process may represent an alternative to classical CSF-1 receptor signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

293T cells were grown in Dulbecco-Vogt-modified Eagle's medium containing 10% calf serum. p388D1 cells (kindly provided by Edward Dennis, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, Calif.) were grown in Iscove's-modified Dulbecco's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. A polyclonal anti-CSF-1 receptor serum was raised against a glutathione S-transferase-CSF-1 receptor kinase insert domain fusion protein. In addition, polyclonal anti-CSF-1 receptor antiserum raised against the carboxy terminus (sc-692) and polyclonal anti-PS1 (sc-7860) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, Calif.). Dimethyl pimelimidate 2HCl was purchased from Pierce (Rockford, Ill.). N-Acetyl-Leu-Leu-norleucinal (LL-n-L), methylamine, LPS, and PMA were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). The γ-secretase inhibitor L-685,458 was purchased from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany).

Expression of wild-type and mutant CSF-1 receptors in 293 cells.

293 cells were grown on 10-cm tissue culture dishes coated with polylysine and transfected at 30% confluency with 2 μg of pcDNA3 CSF-1 receptor or 5 μg of dominant-negative PS1. Transfections were carried out using Lipofectin and Optimem purchased from Gibco BRL (Gaithersburg, Md.). Cells were lysed 96 h after transfection.

Construction of insulin receptor chimera and deletion mutant CSF-1 receptors.

Chimeric receptors and receptor mutants were generated by PCR using the Advantage-HF 2 PCR kit from Clontech (Palo Alto, Calif.). All receptor cDNAs were cloned into pcDNA3 and sequenced to ensure fidelity.

PMA, LPS, LL-n-L, methylamine, and the γ-secretase inhibitor L-685,458.

PMA and LPS were added at a final concentration of 100 ng/ml to macrophages or transiently transfected 293 cells at 37°C for the indicated times. LL-n-L was added at a final concentration of 50 μg/ml for 14 h at 37°C, and methylamine was added at a final concentration of 10 mM 1 h prior to stimulation. The γ-secretase inhibitor L-685,458 was added at a final concentration of 5 μM for 14 h at 37°C.

Immunoprecipitation experiments.

Cells were grown to confluency on 10-cm tissue culture dishes and starved for 24 h for 293 cells or 14 h for macrophage cells. Before lysis, the cells were stimulated with PMA and then rinsed twice with cold Tris-buffered saline (TBS) and lysed in 1 ml of 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 100 mM NaF, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 500 μM sodium orthovanadate, 10 μg of aprotinin/ml, and 10 μg of leupeptin/ml (PLC lysis buffer) per 10-cm tissue culture dish. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm in an Eppendorf microcentrifuge at 4°C. CSF-1 receptors were immunoprecipitated by incubation of cell lysates with polyclonal anti-CSF-1 receptor kinase insert antiserum covalently coupled to protein A-Sepharose with rocking for 1.5 h at 4°C or by incubation of cell lysates with 10 μl of polyclonal anti-CSF-1 receptor carboxy-terminus antiserum (sc-692) for 1 h at 4°C, followed by incubation with 100 μl of a 10% slurry of protein A-Sepharose with rocking for 1 h at 4°C. Immunoprecipitates were washed four times with 1 ml of PLC lysis buffer, boiled for 5 min in 62.5 mM Tris-Cl (pH 6.8), 10% glycerol, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 2.3% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 0.025% bromophenol blue (SDS sample buffer) and resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

Immunoblotting.

Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes using a Bio-Rad (Hercules, Calif.) semidry transfer apparatus at 50 mA per gel for 50 min at room temperature. Membranes were blocked for 45 min at room temperature in 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 0.2% Tween 20 (TBS-T) containing 5% milk and then incubated with a 1:200 dilution of either the polyclonal CSF-1 receptor antiserum raised to the kinase insert or the carboxy terminus or a 1:500 dilution of the polyclonal PS1 antiserum in TBS-T with 5% milk for 1 h at room temperature. Blots were washed twice for 10 min in TBS-T and twice for 5 min in TBS. Membranes were then incubated for 30 min with protein A-horseradish peroxidase diluted 1:10,000 in TBS-T and washed as before. Reactive proteins were visualized by using an ECL kit purchased from Amersham Pharmacia (Piscataway, N.J.).

Cell fractionization.

Cells were grown to confluency on 10-cm tissue culture dishes, rinsed once with cold TBS and once with cold 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.4), 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EGTA, 0.1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 μg of aprotinin/ml, and 10 μg of leupeptin/ml (hypotonic lysis buffer [HLB]), and lysed by Dounce homogenization after swelling in 700 μl of HLB per 10-cm dish. Lysates were centrifuged for 45 min at 10,000 rpm in an Eppendorf microcentrifuge at 4°C to separate the particulate and soluble fractions.

Immunofluorescence.

p388D1 macrophages were plated onto polylysine-coated glass coverslips, grown for 24 h, and subsequently starved for 16 h in the presence of inhibitors as indicated. Cells were treated with PMA for 10 or 90 min at 37°C and fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 15 min at room temperature. Coverslips were washed three times with PBS and subsequently permeabilized and blocked for 15 min in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBS-T) with 0.3% TX-100 and 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Coverslips were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with the anti-CSF-1 receptor kinase insert polyclonal antibody diluted 1:1,000 in PBS-T containing 5% BSA and 3% normal goat serum in a humidified chamber. Coverslips were washed three times for 5 min with PBS-T at room temperature, incubated for 30 min at room temperature with goat anti-rabbit-Alexa 488 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.), and diluted 1:500 in PBS-T containing 5% BSA and 3% normal goat serum. Coverslips were washed as before and mounted onto glass slides with Airvol 205 (Air Products and Chemical, Inc., Allentown, Pa.) containing DABCO (1,4-diazabicyclo-[2.2.2]octane; Sigma Aldrich) and stored in the dark at 4°C. Immunostained cells were visualized with a Leica DMR microscope equipped with a Sony digital camera.

RESULTS

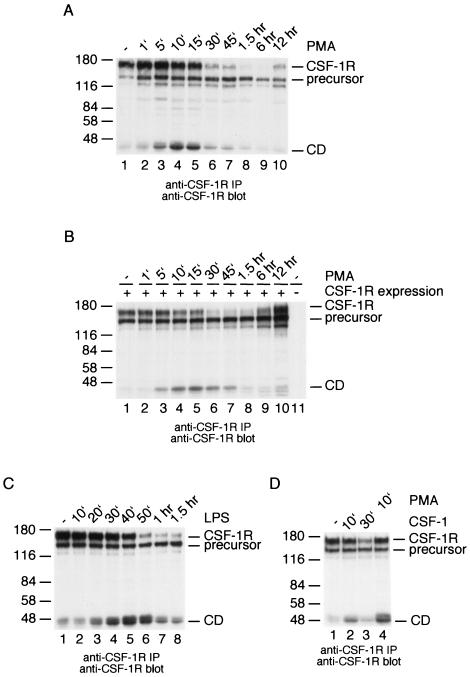

Activation of protein kinase C (PKC) using PMA has previously been shown to cause CSF-1 receptor down-modulation (3, 13, 14, 22, 27). To investigate the dynamics of this process, p388D1 macrophages were incubated for various amounts of time with PMA before the cells were lysed. CSF-1 receptors were isolated by immunoprecipitation and detected by anti-CSF-1 receptor immunoblotting. The results showed that mature receptors start to disappear from the cell between 5 and 10 min after addition of PMA (Fig. 1A). Receptor down-modulation reached maximal levels 1.5 h after addition of PMA (Fig. 1A). We noticed the appearance of a 45-kDa protein that reacted with the anti-CSF-1 receptor serum, just as mature receptors were starting to disappear (Fig. 1A). This fragment was first seen 1 min after the addition of PMA. It reached maximal levels within 10 to 15 min, and it had disappeared almost completely at 1.5 h after addition of PMA. Similar results were obtained in 293 cells transiently expressing the wild-type CSF-1 receptors (Fig. 1B). These experiments suggested that PMA induces proteolytic processing of the CSF-1 receptor and that this results in the transient appearance of a 45-kDa fragment containing the CSF-1 receptor cytoplasmic domain.

FIG. 1.

PMA- and LPS-induced CSF-1 receptor down-modulation results in the appearance of a 45-kDa receptor fragment. (A) p388D1 macrophages were stimulated with 100 ng of PMA/ml for the indicated amounts of time. CSF-1 receptors were isolated by immunoprecipitation and analyzed by anti-CSF-1 receptor immunoblotting. (B) 293 cells were transfected with a CSF-1 receptor expression construct (lanes 1 to 10) or with a control plasmid (lane 11). The cells were stimulated with PMA for the indicated amounts of time and analyzed as described for panel A. (C) p388D1 macrophages were stimulated with 100 ng of LPS/ml for the indicated amounts of time and analyzed by anti-CSF-1 receptor immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting. (D) p388D1 macrophages were stimulated with 100 ng of CSF-1 or PMA/ml for the indicated amounts of time and analyzed by anti-CSF-1 receptor immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting. CD is the CSF-1 receptor cytoplasmic domain.

To find out whether a 45-kDa CSF-1 receptor fragment is formed in response to other activators of macrophages, p388D1 cells were stimulated with LPS for various amounts of time. Receptors were isolated by immunoprecipitation and analyzed by anti-CSF-1 receptor immunoblotting. The experiment showed that LPS caused the disappearance of mature CSF-1 receptors and stimulated the formation of a 45-kDa receptor fragment (Fig. 1C). This fragment was also formed in response to CSF-1, although at significantly lower levels (Fig. 1D). Thus, PMA, LPS, and CSF-1 induce processing of the CSF-1 receptor, which results in the formation of a 45-kDa cell-associated CSF-1 receptor fragment.

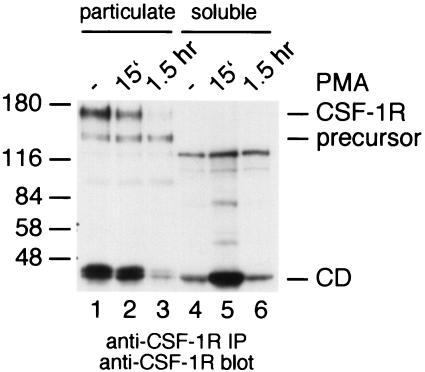

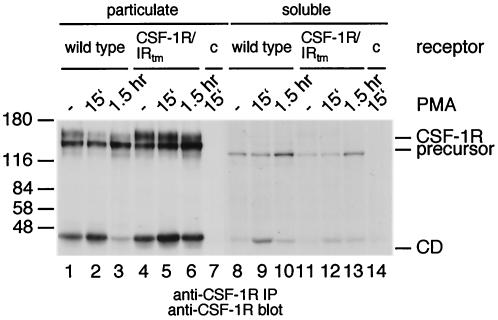

To find out whether this fragment remains associated with the membrane or whether it is released into the cytoplasm, lysates of PMA-stimulated macrophages were separated by high-speed centrifugation into a particulate and a soluble fraction. Both fractions were analyzed for the presence of mature receptors and cytoplasmic fragments by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting. The results showed that full-length receptors were only present in the particulate fraction (Fig. 2). Cytoplasmic fragments were found mainly in the particulate fraction of control cells. In response to PMA, cytoplasmic fragments disappeared from the particulate fraction and appeared transiently in the soluble fraction (Fig. 2). These results show that PMA-induced processing of the CSF-1 receptor is a multistep process. In the first step the receptor is trimmed, and this results in the appearance of the 45-kDa CSF-1 receptor cytoplasmic domain. In the second step, this fragment is released from the membrane into the cytoplasm. The results in Fig. 2 suggest that PMA stimulates processing of the mature receptor as well as processing of the cytoplasmic fragment.

FIG. 2.

Release of the CSF-1 receptor cytoplasmic domain into the cytoplasm following activation of PKC. Control macrophages (lanes 1 and 4) or macrophages stimulated with PMA for 15 min (lanes 2 and 5) or for 1.5 h (lanes 3 and 6) were lysed and separated into a particulate fraction (lanes 1 to 3) and a soluble fraction (lanes 4 to 6). Both fractions were analyzed by anti-CSF-1 receptor immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting.

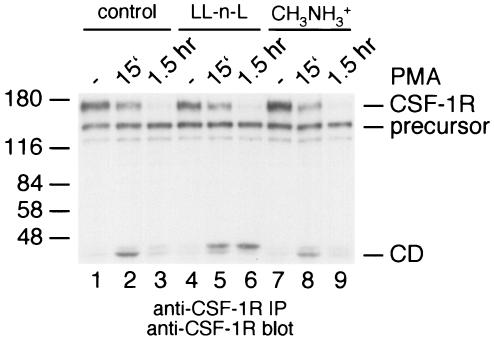

Our results show that the cytoplasmic domain turns over rapidly once it is released into the cytosol, with most of it being degraded within 90 min after the addition of PMA to the cells. To find out where the cytoplasmic domain is degraded, cells were stimulated with PMA after treatment with the proteosomal inhibitor LL-n-L or the lysosomal inhibitor methylamine (Fig. 3). The results showed that the half-life of the cytoplasmic domain was significantly prolonged in the presence of LL-n-L (Fig. 3). In contrast methylamine, an inhibitor of lysosomal degradation, had no effect (Fig. 3). These observations suggest that the cytoplasmic domain of the CSF-1 receptor is degraded by the proteosome after it is released from the membrane.

FIG. 3.

The CSF-1 receptor cytoplasmic domain is degraded in the proteosome. Control p388D1 macrophages (lanes 1 to 3) and macrophages pretreated with the proteosomal inhibitor LL-n-L (lanes 4 to 6) or the lysosomal inhibitor methylamine (lanes 7 to 9) were left unstimulated (lanes 1, 4, and 7) or were stimulated with PMA for 15 min (lanes 2, 5, and 8) or for 1.5 h (lanes 3, 6, and 9). The cells were lysed and analyzed by anti-CSF-1 receptor immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting.

Initially, we hypothesized that, in the presence of PMA, PKC would phosphorylate the CSF-1 receptor somewhere in its cytoplasmic domain and that phosphorylation would mark the receptor for processing. To test this, we constructed a chimera containing the extracellular domain of the CSF-1 receptor and the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domain of the insulin receptor (Fig. 4A). The insulin receptor and the CSF-1R/IRtm-cyto chimera were transiently expressed in 293 cells and tested for processing after stimulation with PMA. While the insulin receptor was unaffected by the presence of PMA, the chimera disappeared rapidly from the cells following addition of PMA (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, the cytoplasmic domain generated from this chimera appeared to be stable (Fig. 4B). Thus, the initial step in receptor processing is dependent on the sequence of the extracellular domain. Once generated, the cytoplasmic domain of the CSF-1 receptor is degraded in the proteosome, while the cytoplasmic domain of the insulin receptor is not.

To find out why the insulin receptor cytoplasmic domain is stable, we constructed CSF-1 receptors in which the transmembrane domain, the juxtamembrane region, or the kinase domain was replaced with those of the insulin receptor (Fig. 4A). In addition, we constructed CSF-1 receptors lacking the kinase insert domain or the carboxy terminus (Fig. 4A). These receptors were transiently expressed in 293 cells and tested for their susceptibility to PMA-induced processing. The results showed that the cytoplasmic domains of all receptors were degraded normally, with the exception of the cytoplasmic domain from a chimera containing the insulin receptor transmembrane domain (Fig. 4C and D). To further investigate the role of the transmembrane domain in degradation of the cytoplasmic domain, we directly compared two CSF-1 receptor chimera: one containing the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of the insulin receptor and a second one containing only the cytoplasmic domain of the insulin receptor (Fig. 5). While the cytoplasmic domain of the first chimera appeared to be stable, the cytoplasmic domain of the second chimera was degraded during prolonged exposure to PMA (Fig. 5). These experiments indicate that the CSF-1 receptor transmembrane domain is essential for degradation of the cytoplasmic domain in response to PMA.

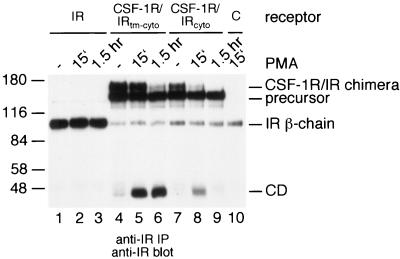

FIG. 5.

The CSF-1 receptor transmembrane domain directs degradation of the insulin receptor cytoplasmic domain. 293 cells were transfected with expression constructs for the wild-type insulin receptor (IR; lanes 1 to 3), the CSF-1R/IRtm-cyto chimera (lanes 4 to 6), the CSF-1R/IRcyto chimera (lanes 7 to 9), or a control plasmid (lane 10). Cells were left untreated (lanes 1, 4, and 7) or were stimulated with PMA for 15 min (lanes 2, 5, 8, and 10) or for 1.5 h (lanes 3, 6, and 9). The cells were lysed and analyzed by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting with an antiserum against the insulin receptor β chain.

Two models could explain the observed results. First, the cytoplasmic domain is stabilized because it is not released into the cytosol and therefore not available for proteosomal degradation. Second, the cytoplasmic domain is stabilized because a recognition sequence necessary for degradation is no longer present once released from the membrane. To distinguish between these two possibilities, cells expressing the CSF-1R/IRTM chimeric receptor were treated with PMA, lysed in HLB, and separated into a particulate and a soluble fraction. In contrast to what was found with the wild-type receptor, the cytoplasmic domain of the CSF-1R/IRTM chimeric receptor remained associated with the particulate fraction (Fig. 6). These data suggest that the cytoplasmic domain needs to be released from the membrane before it can be degraded by the proteosome.

FIG. 6.

The transmembrane domain is essential for release of the CSF-1 receptor cytoplasmic domain into the cytosol. 293 cells were transfected with expression constructs for the wild-type CSF-1 receptor (lanes 1 to 3 and 8 to 10), the CSF-1R/IRtm chimera (lanes 4 to 6 and 11 to 13), or a control plasmid (lanes 7 and 14). Control cells (lanes 1, 4, 8, and 11) or cells stimulated with PMA for 15 min (lanes 2, 5, 7, 9, 12, and 14) or for 1.5 h (lanes 3, 6, 10, and 13) were lysed and separated into a particulate fraction (lanes 1 to 7) and a soluble fraction (lanes 8 to 14). Both fractions were analyzed by anti-CSF-1 receptor immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting.

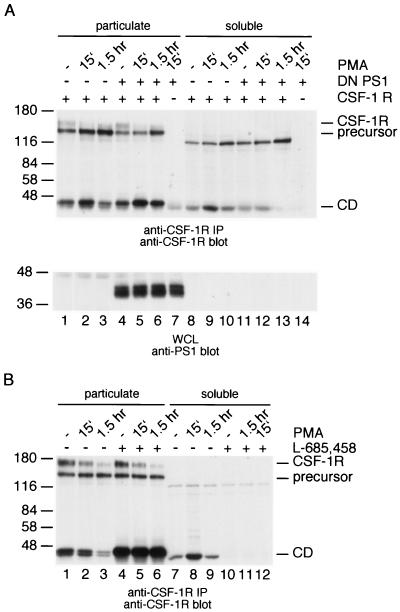

The observation that replacement of the transmembrane domain blocks further processing suggests that the CSF-1 receptor is subject to RIP. To determine whether γ-secretase is involved in release of the cytoplasmic domain, wild-type CSF-1 receptors were coexpressed with a dominant-negative PS1 mutant in 293 cells. Control and PMA-stimulated cells were lysed and separated into particulate and soluble fractions that were analyzed for the presence of the cytoplasmic domain (Fig. 7A). Whole-cell lysates were analyzed for expression of dominant-negative PS (Fig. 7A). The results showed that in the presence of a dominant-negative PS1, the CSF-1 receptor cytoplasmic domain accumulated in the membrane fraction, while very little was released into the cytosol (Fig. 7A). In a second and independent approach, macrophages were pretreated with the γ-secretase inhibitor L-685,458 and then treated with PMA (Fig. 7B). Both the particulate and the soluble fraction were analyzed for the presence of the cytoplasmic domain (Fig. 7B). The results showed that inhibition of γ-secretase results in an accumulation of the membrane-bound cytoplasmic domain in the presence or absence of PMA. These results suggest strongly that release of the CSF-1 receptor cytoplasmic domain from the membrane is mediated by γ-secretase.

FIG. 7.

Dominant-negative PS1 and a γ-secretase inhibitor interfere with the release of the CSF-1 receptor cytoplasmic domain into the cytosol. (A) 293 cells were transfected with expression constructs for the wild-type CSF-1 receptor (lanes 1 to 6 and 8 to 13) or with a control plasmid (lanes 7 and 14) and an expression construct for dominant-negative PS1 (lanes 4 to 7 and lanes 11 to 14) or a control plasmid (lanes 1 to 3 and lanes 8 to 10). Control cells (lanes 1, 4, 8, and 11) or cell stimulated with PMA for 15 min (lanes 2, 5, 7, 9, 12, and 14) or for 1.5 h (lanes 3, 6, 10, and 13) were lysed and separated into a particulate fraction (lanes 1 to 7) and a soluble fraction (lanes 8 to 14). Both fractions were analyzed by anti-CSF-1 receptor immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting (top panel). Whole-cell lysates were analyzed by anti-PS1 immunoblotting (bottom panel). (B) Control p388D1 macrophages (lanes 1 to 3 and 7 to 9) or macrophages pretreated with the γ-secretase inhibitor L-685,458 (lanes 4 to 6 and 10 to 12) were left unstimulated (lanes 1, 4, 7, and 10) or were stimulated with PMA for 15 min (lanes 2, 5, 8, and 11) or for 1.5 h (lanes 3, 6, 9, and 12). The cells were lysed and separated into a particulate (lanes 1 to 6) and a soluble (lanes 7 to 12) fraction. Both fractions were analyzed by anti-CSF-1 receptor immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting.

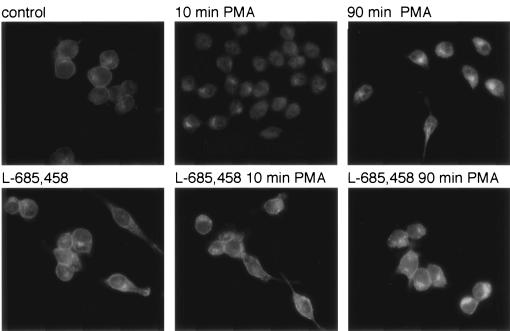

To find out whether processing takes place at the cell surface or at an internal membrane following internalization, control macrophages and macrophages that were pretreated with the γ-secretase inhibitor were stimulated with PMA and analyzed by anti-CSF-1 receptor immunofluorescence. The results showed that CSF-1 receptors were present at the plasma membrane and throughout the cell, as well as in a discrete cytoplasmic conglomerate (Fig. 8). It appeared that there was also some nuclear staining. The addition of PMA for 10 min resulted in the disappearance of receptors from the cell surface and possibly an increase in nuclear staining (Fig. 8). These results are consistent with the biochemical data and suggest that, after being released from the membrane, the CSF-1 receptor cytoplasmic domain accumulates in the cytosol and the nucleus. When cells are stimulated with PMA following pretreatment with the γ-secretase inhibitor, we observed continued strong staining at the plasma membrane (Fig. 8). This suggests that CSF-1 receptors are processed by γ-secretase while present at the cell surface.

FIG. 8.

CSF-1 receptors are processed at the plasma membrane. Control p388D1 macrophages and macrophages pretreated with the γ-secretase inhibitor L-685,458 were left unstimulated or were stimulated with PMA for 10 or 90 min and analyzed by anti-CSF-1 receptor immunofluorescence.

DISCUSSION

The CSF-1 receptor is synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum as a 130-kDa precursor protein (25, 54). This precursor is converted into the 150-kDa CSF-1 receptor by modification of its Asn-linked sugar chains. Our antibodies also reacted with an uncharacterized 120-kDa protein that appears to be related to the CSF-1 receptor (Fig. 1 and 2). Only the 150-kDa CSF-1 receptor is expressed on the cell surface and is subject to proteolytic processing and down-modulation in response to PMA.

Our results suggest that proteolytic processing and down-modulation of the CSF-1 receptor take place continuously and that the rate of this process increases substantially in response to PMA. Since PMA is an artificial stimulator of PKC, it is important to find out whether PMA-dependent receptor down-modulation reflects a physiologically relevant process. To address this, we included an experiment in which macrophages were stimulated with LPS. The result showed that LPS causes CSF-1 receptor processing, in a manner that is very similar to what can be observed after stimulation with PMA, the only difference being that the time course with LPS is somewhat delayed. This is most likely due to the fact that LPS is not a direct activator of PKC. We also observed the generation of the ∼45-kDa cytoplasmic domain in response to CSF-1, although at lower levels than observed in response to PMA. Several other studies have shown shedding of the CSF-1 receptor extracellular domain following stimulation with granulocyte-macrophage CSF, tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-2, or interleukin-4 (12, 17, 19, 31). Thus, CSF-1 receptor processing appears to be a normal process that can be activated by a number of physiologically relevant stimuli.

We have investigated PMA-induced down-modulation of the CSF-1 receptor by following the fate of its cytoplasmic domain. Our observations suggest that this process involves two separate cleavage events. First, the receptor is cleaved outside the plasma membrane, resulting in the release of its extracellular domain. Second, the receptor is cleaved within the transmembrane domain, resulting in the release of its cytoplasmic domain into the cytosol. This is very similar to what has been observed for several other cell surface proteins, including APP, Notch, and ErbB4 (9, 24, 71). We found that, in contrast to the CSF-1 receptor, the insulin receptor is not subject to this process. Thus, some but not all receptor protein-tyrosine kinases are subject to PKC-dependent proteolytic processing.

The general consensus is that PMA-dependent receptor down-modulation is initiated by activation of extracellular metalloproteases that recognize specific receptors. The alternative is that PKC phosphorylates receptors on their cytoplasmic domain, thereby marking them for down-modulation. We have tested this model by generating a chimera that is composed of the extracellular domain of the CSF-1 receptor and the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of the insulin receptor. Our experiment showed that initiation of CSF-1 receptor processing is independent of its cytoplasmic domain. This is consistent with an observation showing that there is no increase in CSF-1 receptor phosphorylation upon activation of PKC (22).

It has been found recently that release of the extracellular domain of the CSF-1 receptor is mediated by TACE (59). TACE is a cell surface-associated metalloprotease that is composed of an extracellular catalytic domain, a transmembrane domain, and a small cytoplasmic domain (34). TACE has been implicated in the processing of several membrane proteins, including APP, Notch, and ErbB-4 (7, 10, 56, 63). Exactly how TACE is activated by PKC remains to be established (18, 57). Thus, PMA-induced CSF-1 receptor processing is initiated by the activation of TACE, which recognizes a specific sequence in the extracellular domain of the CSF-1 receptor.

After the release of the extracellular domain into the medium, the CSF-1 receptor is cleaved within the transmembrane domain, resulting in the release of its cytoplasmic domain into the cytosol. Two protease families are involved in regulated intramembrane proteolysis, the site 2 proteases and the PSs. The site 2 protease is involved in regulation of cholesterol biosynthesis. It cleaves the SREBP within one of its transmembrane domains. This results in the release of a transcription factor that activates genes involved in cholesterol biosynthesis (8). The PSs, which are thought to represent the catalytic subunits of γ-secretase, have been implicated in intramembrane cleavage of a variety of proteins, including APP, Notch, ErbB-4, E-cadherin, LRP, Nectin-1α, Jagged2, Delta1, DCC, and CD44 (2, 20, 26, 30, 35, 36, 43, 44, 47, 50, 51, 62, 69). We have used the γ-secretase inhibitor L-685,458 and a dominant-negative PS1 to show that CSF-1 receptor is cleaved by PS.

It is well established that SREBP is cleaved in the Golgi apparatus (16, 48). APP is cleaved either in the Golgi apparatus or in the endosomes (60). Recent evidence suggests that Notch associates with PS1 in the endoplasmic reticulum, while Notch is cleaved after the complex appears at the cell surface (51). To find out where the CSF-1 receptor is processed, cells that had been treated with the γ-secretase inhibitor L-685,458 were analyzed by anti-CSF-1 receptor immunofluorescence. The data showed that the membrane-bound ∼45-kDa CSF-1 receptor fragment accumulated at the plasma membrane. This suggests strongly that the CSF-1 receptor is cleaved by γ-secretase at the cell surface.

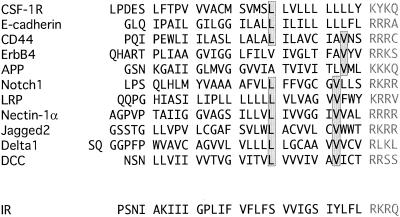

Despite its importance during development and possibly during the onset of Alzheimer's disease, the specificity of γ-secretase is still poorly understood. Analysis of APP transmembrane domain mutants led to the conclusion that γ-secretase can tolerate a variety of point mutations in the transmembrane domain of its substrates (40, 41, 66). This led to the suggestion that γ-secretase simply recognizes transmembrane proteins that have lost their extracellular domains (9, 66). Mutation of a specific valine residue in the Notch transmembrane domain inhibits processing and blocks biological activity in vivo (29). This suggests that γ-secretase requires the presence of specific residues in the transmembrane domain of its substrates. Our results show that replacing the CSF-1 receptor transmembrane domain with that of the insulin receptor blocks the release of the cytoplasmic domain into the cytosol. This suggests that γ-secretase can distinguish the CSF-1 receptor transmembrane domain from the insulin receptor transmembrane domain. To find out whether there is any sequence conservation, we aligned the transmembrane sequences of a number of γ-secretase substrates (Fig. 9). This alignment showed the presence of a leucine at 11 residues and a valine at 3 or 4 residues from the end of the transmembrane domain (Fig. 9). Most sequences contained both of these elements, while some contained only the leucine or the valine. The insulin receptor transmembrane domain, which is resistant to intramembrane cleavage, lacks both of these elements.

FIG. 9.

Alignment of transmembrane domains of γ-secretase substrates. The transmembrane domains of several γ-secretase substrates were aligned (2, 20, 30, 35, 43, 44, 47, 50, 51, 69). The transmembrane domain of the insulin receptor was included for comparison. Conserved residues are boxed, and stop-transfer signals are shown in grey.

What is the function of PKC-dependent CSF-1 receptor processing? Receptor processing is initiated by release of the extracellular domain. This blocks the ability of cells to respond to the presence of CSF-1. In addition, the extracellular domain can bind to CSF-1, thereby reducing the active levels of this cytokine. Finally, the extracellular domain could act as a ligand for CSF-1 precursors present on the surface of CSF-1-producing cells. CSF-1 is synthesized as part of a precursor protein that is composed of an extracellular domain, a transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic domain. Soluble CSF-1 is released from this precursor by proteolytic cleavage (53, 55). Interestingly, there exists an alternatively spliced version of this precursor that lacks the cleavage site and that could act as a surface-bound ligand or as a receptor. The extracellular domain that is released from the CSF-1 receptor represents a potential ligand for the membrane-bound CSF-1 precursor protein.

It has been well established that following its release from the plasma membrane, the cytoplasmic domain of Notch moves to the nucleus, where it stimulates transcription of specific target genes (64, 67, 68, 75). More recently it has been suggested that the cytoplasmic domain of APP, in association with Fe65, can act as a transcription factor (11, 26, 37). Finally, there is some evidence that the cytoplasmic domain of ErbB4 can move to the nucleus, where it may activate transcription of specific target genes (47). Immunofluorescence experiments showed some nuclear CSF-1 receptor staining. Although it is tempting to speculate about a nuclear function for the CSF-1 receptor cytoplasmic domain, future research will be required to confirm its nuclear presence and to find out whether this presence has any functional consequences.

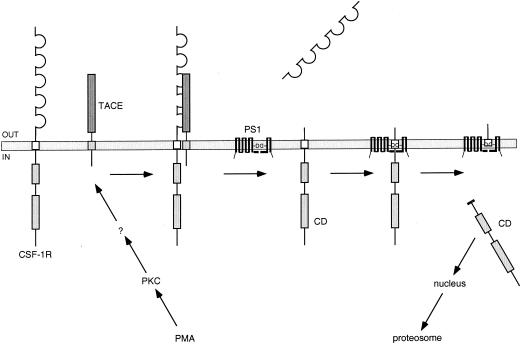

In summary, our model indicates that PMA-induced activation of PKC leads to cleavage of the CSF-1 receptor ectodomain by the α-secretase TACE (Fig. 10). TACE recognition of the CSF-1 receptor is only dependent upon extracellular sequences. The remaining membrane-bound cytoplasmic domain is released into the cytosol by γ-secretase (Fig. 10). Our results show that the transmembrane domain forms part of the recognition site for γ-secretase. After release from the membrane, the cytoplasmic domain may localize partly to the nucleus and is degraded by the proteosome (Fig. 10). Our results suggest that the CSF-1 receptor utilizes an alternative signaling mechanism that involves release of its cytoplasmic domain into the cell.

FIG. 10.

Model for CSF-1 receptor down-modulation and release of its cytoplasmic domain. PMA-induced activation of PKC leads to cleavage of the CSF-1 receptor ectodomain by TACE. TACE recognition of the CSF-1 receptor is only dependent upon extracellular sequences. The remaining membrane-bound cytoplasmic domain (CD) is recognized by γ-secretase and cleaved within the transmembrane domain. Intramembrane cleavage is dependent on the CSF-1 receptor transmembrane sequence and results in the release of the CD into the cytosol. Once released into the cell, the CD localizes in part to the nucleus and is degraded by the proteosome.

Acknowledgments

We thank Todd Golde for the PS1 constructs.

This work was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health training grant (NIH/NCI 5 T32 CA09523).

REFERENCES

- 1.Alonso, G., M. Koegl, N. Mazurenko, and S. A. Courtneidge. 1995. Sequence requirements for binding of Src family tyrosine kinases to activated growth factor receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 270:9840-9848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Annaert, W. G., L. Levesque, K. Craessaerts, I. Dierinck, G. Snellings, D. Westaway, P. S. George-Hyslop, B. Cordell, P. Fraser, and B. De Strooper. 1999. Presenilin 1 controls gamma-secretase processing of amyloid precursor protein in pre-Golgi compartments of hippocampal neurons. J. Cell Biol. 147:277-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baccarini, M., P. Dello Sbarba, D. Buscher, A. Bartocci, and E. R. Stanley. 1992. IFN-gamma/lipopolysaccharide activation of macrophages is associated with protein kinase C-dependent down-modulation of the colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor. J. Immunol. 149:2656-2661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourette, R. P., S. Arnaud, G. M. Myles, J. P. Blanchet, L. R. Rohrschneider, and G. Mouchiroud. 1998. Mona, a novel hematopoietic-specific adaptor interacting with the macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor, is implicated in monocyte/macrophage development. EMBO J. 17:7273-7281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourette, R. P., G. M. Myles, J. L. Choi, and L. R. Rohrschneider. 1997. Sequential activation of phoshatidylinositol 3-kinase and phospholipase C-γ2 by the M-CSF receptor is necessary for differentiation signaling. EMBO J. 16:5880-5893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourette, R. P., and L. R. Rohrschneider. 2000. Early events in M-CSF receptor signaling. Growth Factors 17:155-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brou, C., F. Logeat, N. Gupta, C. Bessia, O. LeBail, J. R. Doedens, A. Cumano, P. Roux, R. A. Black, and A. Israel. 2000. A novel proteolytic cleavage involved in Notch signaling: the role of the disintegrin-metalloprotease TACE. Mol. Cell 5:207-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown, M. S., and J. L. Goldstein. 1997. The SREBP pathway: regulation of cholesterol metabolism by proteolysis of a membrane-bound transcription factor. Cell 89:331-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown, M. S., J. Ye, R. B. Rawson, and J. L. Goldstein. 2000. Regulated intramembrane proteolysis: a control mechanism conserved from bacteria to humans. Cell 100:391-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buxbaum, J. D., K. N. Liu, Y. Luo, J. L. Slack, K. L. Stocking, J. J. Peschon, R. S. Johnson, B. J. Castner, D. P. Cerretti, and R. A. Black. 1998. Evidence that tumor necrosis factor alpha converting enzyme is involved in regulated alpha-secretase cleavage of the Alzheimer amyloid protein precursor. J. Biol. Chem. 273:27765-27767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao, X., and T. C. Sudhof. 2001. A transcriptionally active complex of APP with Fe65 and histone acetyltransferase Tip60. Science 293:115-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, B. D., C. R. Clark, and T. H. Chou. 1988. Granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor stimulates monocyte and tissue macrophage proliferation and enhances their responsiveness to macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Blood 71:997-1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, B. D., H. S. Lin, and S. Hsu. 1983. Lipopolysaccharide inhibits the binding of colony-stimulating factor (CSF-1) to murine peritoneal exudate macrophages. J. Immunol. 130:2256-2260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen, B. D., H. S. Lin, and S. Hsu. 1983. Tumor-promoting phorbol esters inhibit the binding of colony-stimulating factor (CSF-1) to murine peritoneal exudate macrophages. J. Cell. Physiol. 116:207-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dai, X. M., G. R. Ryan, A. J. Hapel, M. G. Dominguez, R. G. Russell, S. Kapp, V. Sylvestre, and E. R. Stanley. 2002. Targeted disruption of the mouse colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor gene results in osteopetrosis, mononuclear phagocyte deficiency, increased primitive progenitor cell frequencies, and reproductive defects. Blood 99:111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeBose-Boyd, R. A., M. S. Brown, W. P. Li, A. Nohturfft, J. L. Goldstein, and P. J. Espenshade. 1999. Transport-dependent proteolysis of SREBP: relocation of site-1 protease from Golgi to ER obviates the need for SREBP transport to Golgi. Cell 99:703-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dello Sbarba, P., L. Nencioni, D. Labardi, E. Rovida, B. Caciagli, and M. G. Cipolleschi. 1996. Interleukin 2 down-modulates the macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor in murine macrophages. Cytokine 8:488-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dello Sbarba, P., and E. Rovida. 2002. Transmodulation of cell surface regulatory molecules via ectodomain shedding. Biol. Chem. 383:69-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dello Sbarba, P., E. Rovida, B. Caciagli, L. Nencioni, D. Labardi, A. Paccagnini, L. Savini, and M. G. Cipolleschi. 1996. Interleukin-4 rapidly down-modulates the macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor in murine macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 60:644-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Strooper, B., W. Annaert, P. Cupers, P. Saftig, K. Craessaerts, J. S. Mumm, E. H. Schroeter, V. Schrijvers, M. S. Wolfe, W. J. Ray, A. Goate, and R. Kopan. 1999. A presenilin-1-dependent gamma-secretase-like protease mediates release of Notch intracellular domain. Nature 398:518-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doan, A., G. Thinakaran, D. R. Borchelt, H. H. Slunt, T. Ratovitsky, M. Podlisny, D. J. Selkoe, M. Seeger, S. E. Gandy, D. L. Price, and S. S. Sisodia. 1996. Protein topology of presenilin 1. Neuron 17:1023-1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Downing, J. R., M. F. Roussel, and C. J. Sherr. 1989. Ligand and protein kinase C downmodulate the colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor by independent mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9:2890-2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edbauer, D., E. Winkler, J. T. Regula, B. Pesold, H. Steiner, and C. Haass. 2003. Reconstitution of gamma-secretase activity. Nat. Cell Biol. 5:486-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fortini, M. E. 2002. Gamma-secretase-mediated proteolysis in cell-surface-receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 3:673-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Furman, W. L., C. W. Rettenmier, J. H. Chen, M. F. Roussel, C. O. Quinn, and C. J. Sherr. 1986. Antibodies to distal carboxyl terminal epitopes in the v-fms-coded glycoprotein do not cross-react with the c-fms gene product. Virology 152:432-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao, Y., and S. W. Pimplikar. 2001. The gamma-secretase-cleaved C-terminal fragment of amyloid precursor protein mediates signaling to the nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:14979-14984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guilbert, L. J., and E. R. Stanley. 1984. Modulation of receptors for the colony-stimulating factor, CSF-1, by bacterial lipopolysaccharide and CSF-1. J. Immunol. Methods 73:17-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hampe, A., B. M. Shamoon, M. Gobet, C. J. Sherr, and F. Galibert. 1989. Nucleotide sequence and structural organization of the human FMS proto-oncogene. Oncogene Res. 4:9-17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huppert, S. S., A. Le, E. H. Schroeter, J. S. Mumm, M. T. Saxena, L. A. Milner, and R. Kopan. 2000. Embryonic lethality in mice homozygous for a processing-deficient allele of Notch1. Nature 405:966-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikeuchi, T., and S. S. Sisodia. 2003. The Notch ligands, Delta1 and Jagged2, are substrates for presenilin-dependent “gamma-secretase” cleavage. J. Biol. Chem. 278:7751-7754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacobsen, S. E., F. W. Ruscetti, C. M. Dubois, and J. R. Keller. 1992. Tumor necrosis factor alpha directly and indirectly regulates hematopoietic progenitor cell proliferation: role of colony-stimulating factor receptor modulation. J. Exp. Med. 175:1759-1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kacinski, B. M. 1997. CSF-1 and its receptor in breast carcinomas and neoplasms of the female reproductive tract. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 46:71-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kacinski, B. M. 1995. CSF-1 and its receptor in ovarian, endometrial and breast cancer. Ann. Med. 27:79-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Killar, L., J. White, R. Black, and J. Peschon. 1999. Adamalysins. A family of metzincins including TNF-alpha converting enzyme (TACE). Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 878:442-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim, D. Y., L. A. Ingano, and D. M. Kovacs. 2002. Nectin-1α, an immunoglobulin-like receptor involved in the formation of synapses, is a substrate for presenilin/gamma-secretase-like cleavage. J. Biol. Chem. 277:49976-49981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kimberly, W. T., W. P. Esler, W. Ye, B. L. Ostaszewski, J. Gao, T. Diehl, D. J. Selkoe, and M. S. Wolfe. 2003. Notch and the amyloid precursor protein are cleaved by similar gamma-secretase(s). Biochemistry 42:137-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kimberly, W. T., J. B. Zheng, S. Y. Guenette, and D. J. Selkoe. 2001. The intracellular domain of the beta-amyloid precursor protein is stabilized by Fe65 and translocates to the nucleus in a notch-like manner. J. Biol. Chem. 276:40288-40292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lai, E. C. 2002. Keeping a good pathway down: transcriptional repression of Notch pathway target genes by CSL proteins. EMBO Rep. 3:840-845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lendahl, U. 1998. A growing family of Notch ligands. Bioessays 20:103-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lichtenthaler, S. F., N. Ida, G. Multhaup, C. L. Masters, and K. Beyreuther. 1997. Mutations in the transmembrane domain of APP altering gamma-secretase specificity. Biochemistry 36:15396-15403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lichtenthaler, S. F., R. Wang, H. Grimm, S. N. Uljon, C. L. Masters, and K. Beyreuther. 1999. Mechanism of the cleavage specificity of Alzheimer's disease gamma-secretase identified by phenylalanine-scanning mutagenesis of the transmembrane domain of the amyloid precursor protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:3053-3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lioubin, M. N., G. M. Myles, K. Carlberg, D. Bowtell, and L. R. Rohrschneider. 1994. Shc, Grb2, Sos1, and a 150-kilodalton tyrosine-phosphorylated protein form complexes with Fms in hematopoietic cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:5682-5691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marambaud, P., J. Shioi, G. Serban, A. Georgakopoulos, S. Sarner, V. Nagy, L. Baki, P. Wen, S. Efthimiopoulos, Z. Shao, T. Wisniewski, and N. K. Robakis. 2002. A presenilin-1/gamma-secretase cleavage releases the E-cadherin intracellular domain and regulates disassembly of adherens junctions. EMBO J. 21:1948-1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.May, P., Y. K. Reddy, and J. Herz. 2002. Proteolytic processing of low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein mediates regulated release of its intracellular domain. J. Biol. Chem. 277:18736-18743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mumm, J. S., and R. Kopan. 2000. Notch signaling: from the outside in. Dev. Biol. 228:151-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murphy, M. P., S. N. Uljon, P. E. Fraser, A. Fauq, H. A. Lookingbill, K. A. Findlay, T. E. Smith, P. A. Lewis, D. C. McLendon, R. Wang, and T. E. Golde. 2000. Presenilin 1 regulates pharmacologically distinct gamma-secretase activities. Implications for the role of presenilin in gamma-secretase cleavage. J. Biol. Chem. 275:26277-26284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ni, C. Y., M. P. Murphy, T. E. Golde, and G. Carpenter. 2001. γ-Secretase cleavage and nuclear localization of ErbB-4 receptor tyrosine kinase. Science 294:2179-2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nohturfft, A., R. A. DeBose-Boyd, S. Scheek, J. L. Goldstein, and M. S. Brown. 1999. Sterols regulate cycling of SREBP cleavage-activating protein (SCAP) between endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:11235-11240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Novak, U., E. Nice, J. A. Hamilton, and L. Paradiso. 1996. Requirement for Y706 of the murine (or Y708 of the human) CSF-1 receptor for STAT1 activation in response to CSF-1. Oncogene 13:2607-2613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Okamoto, I., Y. Kawano, D. Murakami, T. Sasayama, N. Araki, T. Miki, A. J. Wong, and H. Saya. 2001. Proteolytic release of CD44 intracellular domain and its role in the CD44 signaling pathway. J. Cell Biol. 155:755-762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ray, W. J., M. Yao, J. Mumm, E. H. Schroeter, P. Saftig, M. Wolfe, D. J. Selkoe, R. Kopan, and A. M. Goate. 1999. Cell surface presenilin-1 participates in the gamma-secretase-like proteolysis of Notch. J. Biol. Chem. 274:36801-36807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reedijk, M., X. Liu, P. van der Geer, K. Letwin, M. D. Waterfield, T. Hunter, and T. Pawson. 1992. Tyr721 regulates specific binding of the CSF-1 receptor kinase insert to PI 3′-kinase SH2 domains: a model for SH2-mediated receptor-target interactions. EMBO J. 11:1365-1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rettenmier, C. W. 1989. Biosynthesis of macrophage colony-stimulating factor (CSF-1): differential processing of CSF-1 precursors suggests alternative mechanisms for stimulating CSF-1 receptors. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 149:129-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rettenmier, C. W., M. F. Roussel, R. A. Ashmun, P. Ralph, K. Price, and C. J. Sherr. 1987. Synthesis of membrane-bound colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1) and downmodulation of CSF-1 receptors in NIH 3T3 cells transformed by cotransfection of human CSF-1 and c-fms (CSF-1 receptor) genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:2378-2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rettenmier, C. W., M. F. Roussel, and C. J. Sherr. 1988. The colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1) receptor (c-fms proto-oncogene product) and its ligand. J. Cell Sci. Suppl. 9:27-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rio, C., J. D. Buxbaum, J. J. Peschon, and G. Corfas. 2000. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme is required for cleavage of erbB4/HER4. J. Biol. Chem. 275:10379-10387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roghani, M., J. D. Becherer, M. L. Moss, R. E. Atherton, H. Erdjument-Bromage, J. Arribas, R. K. Blackburn, G. Weskamp, P. Tempst, and C. P. Blobel. 1999. Metalloprotease-disintegrin MDC9: intracellular maturation and catalytic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 274:3531-3540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roussel, M. F., S. A. Shurtleff, J. R. Downing, and C. J. Sherr. 1990. A point mutation at tyrosine-809 in the human colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor impairs mitogenesis without abrogating tyrosine kinase activity, association with phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, or induction of c-fos and junB genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:6738-6742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rovida, E., A. Paccagnini, M. Del Rosso, J. Peschon, and P. Dello Sbarba. 2001. TNF-alpha-converting enzyme cleaves the macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor in macrophages undergoing activation. J. Immunol. 166:1583-1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Selkoe, D. J. 1998. The cell biology of beta-amyloid precursor protein and presenilin in Alzheimer's disease. Trends Cell. Biol. 8:447-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shearman, M. S., D. Beher, E. E. Clarke, H. D. Lewis, T. Harrison, P. Hunt, A. Nadin, A. L. Smith, G. Stevenson, and J. L. Castro. 2000. L-685,458, an aspartyl protease transition state mimic, is a potent inhibitor of amyloid beta-protein precursor gamma-secretase activity. Biochemistry 39:8698-8704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sisodia, S. S., and P. H. St. George-Hyslop. 2002. γ-Secretase, Notch, Abeta and Alzheimer's disease: where do the presenilins fit in? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3:281-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Slack, B. E., L. K. Ma, and C. C. Seah. 2001. Constitutive shedding of the amyloid precursor protein ectodomain is up-regulated by tumour necrosis factor-alpha converting enzyme. Biochem. J. 357:787-794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Song, W., P. Nadeau, M. Yuan, X. Yang, J. Shen, and B. A. Yankner. 1999. Proteolytic release and nuclear translocation of Notch-1 are induced by presenilin-1 and impaired by pathogenic presenilin-1 mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:6959-6963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stanley, E. R., L. J. Guilbert, R. J. Tushinski, and S. H. Bartelmez. 1983. CSF-1—a mononuclear phagocyte lineage-specific hemopoietic growth factor. J. Cell. Biochem. 21:151-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Struhl, G., and A. Adachi. 2000. Requirements for presenilin-dependent cleavage of notch and other transmembrane proteins. Mol. Cell 6:625-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Struhl, G., and I. Greenwald. 1999. Presenilin is required for activity and nuclear access of Notch in Drosophila. Nature 398:522-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Struhl, G., and I. Greenwald. 2001. Presenilin-mediated transmembrane cleavage is required for Notch signal transduction in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:229-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Taniguchi, Y., S. H. Kim, and S. S. Sisodia. 2003. Presenilin-dependent “gamma-secretase” processing of deleted in colorectal cancer (DCC). J. Biol. Chem. 278:30425-30428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tapley, P., A. Kazlauskas, J. A. Cooper, and L. R. Rohrschneider. 1990. Macrophage colony-stimulating factor-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of c-fms proteins expressed in FDC-P1 and BALB/c 3T3 cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:2528-2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Urban, S., and M. Freeman. 2002. Intramembrane proteolysis controls diverse signalling pathways throughout evolution. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12:512-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.van der Geer, P., and T. Hunter. 1990. Identification of tyrosine 706 in the kinase insert as the major colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1)-stimulated autophosphorylation site in the CSF-1 receptor in a murine macrophage cell line. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:2991-3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.van der Geer, P., and T. Hunter. 1993. Mutation of Tyr697, a GRB2-binding site, and Tyr721, a PI 3-kinase binding site, abrogates signal transduction by the murine CSF-1 receptor expressed in Rat-2 fibroblasts. EMBO J. 12:5161-5172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.van der Geer, P., and T. Hunter. 1991. Tyrosine 706 and 807 phosphorylation site mutants in the murine colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor are unaffected in their ability to bind or phosphorylate phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase but show differential defects in their ability to induce early response gene transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:4698-4709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Weinmaster, G. 2000. Notch signal transduction: a real rip and more. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 10:363-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wilhelmsen, K., S. Burkhalter, and P. van der Geer. 2002. C-Cbl binds the CSF-1 receptor at tyrosine 973, a novel phosphorylation site in the receptor's carboxy-terminus. Oncogene 21:1079-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wolfe, M. S., W. Xia, B. L. Ostaszewski, T. S. Diehl, W. T. Kimberly, and D. J. Selkoe. 1999. Two transmembrane aspartates in presenilin-1 required for presenilin endoproteolysis and gamma-secretase activity. Nature 398:513-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]