Abstract

Although extensive structural and biochemical studies have provided molecular insights into the mechanism of cAMP-dependent activation of protein kinase A (PKA), little is known about signal termination and the role of phosphodiesterases (PDEs) in regulatory feedback. In this study we describe a novel mode of protein kinase A-anchoring protein (AKAP)-independent feedback regulation between a specific PDE, RegA and the PKA regulatory (RIα) subunit, where RIα functions as an activator of PDE catalysis. Our results indicate that RegA, in addition to its well-known role as a PDE for bulk cAMP in solution, is also capable of hydrolyzing cAMP-bound to RIα. Furthermore our results indicate that binding of RIα activates PDE catalysis several fold demonstrating a dual function of RIα, both as an inhibitor of the PKA catalytic (C) subunit and as an activator for PDEs. Deletion mutagenesis has localized the sites of interaction to one of the cAMP-binding domains of RIα and the catalytic PDE domain of RegA whereas amide hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry has revealed that the cAMP-binding site (phosphate binding cassette) along with proximal regions important for relaying allosteric changes mediated by cAMP, are important for interactions with the PDE catalytic domain of RegA. These sites of interactions together with measurements of cAMP dissociation rates demonstrate that binding of RegA facilitates dissociation of cAMP followed by hydrolysis of the released cAMP to 5′AMP. cAMP-free RIα generated as an end product remains bound to RegA. The PKA C-subunit then displaces RegA and reassociates with cAMP-free RIα to regenerate the inactive PKA holoenzyme thereby completing the termination step of cAMP signaling. These results reveal a novel mode of regulatory feedback between PDEs and RIα that has important consequences for PKA regulation and cAMP signal termination.

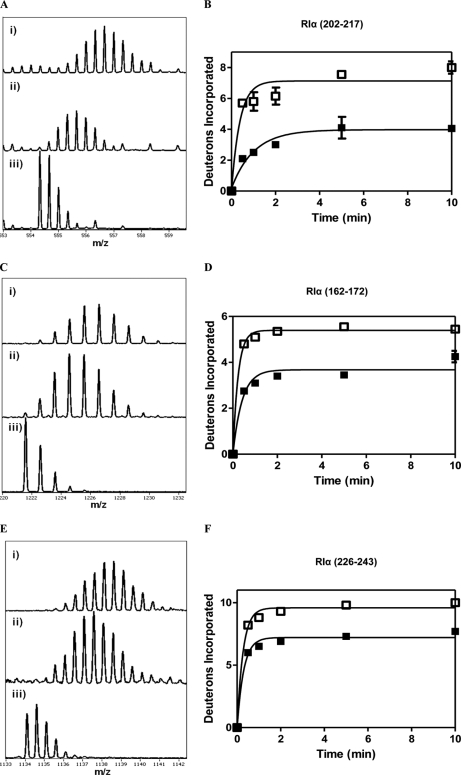

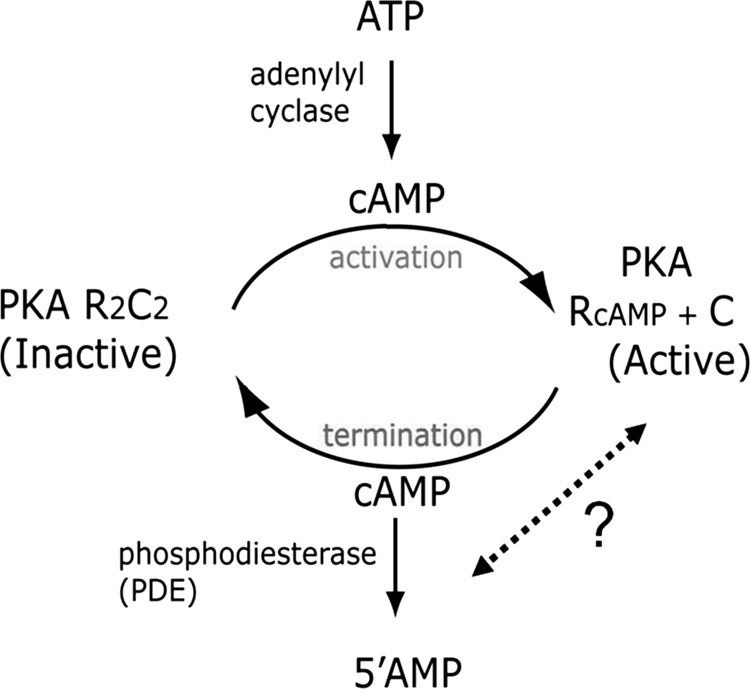

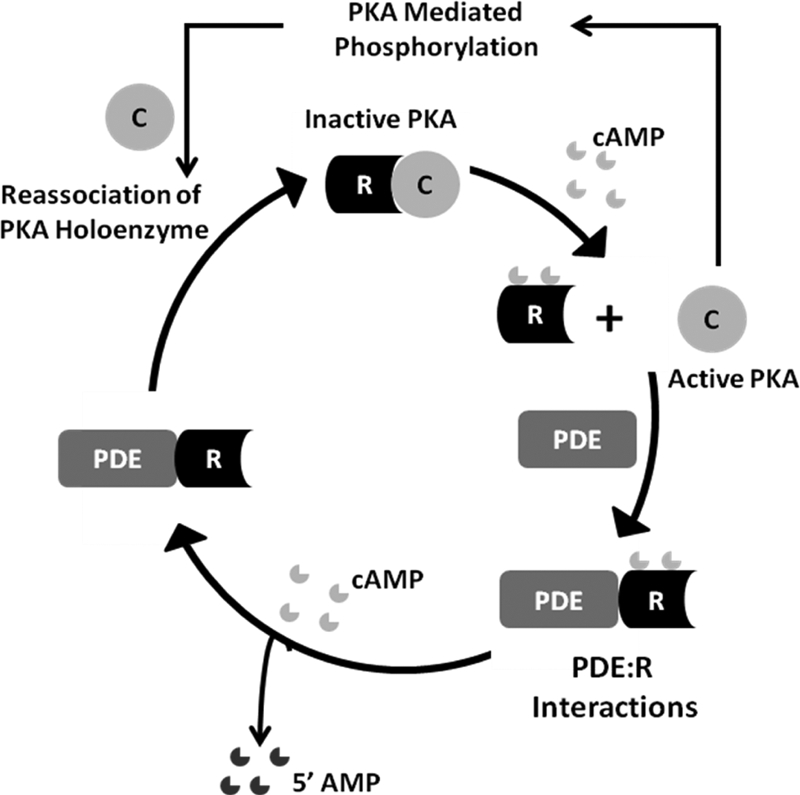

The second messenger, cyclic 3′5′ adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)1, plays a central role in regulating a plethora of metabolic and cellular processes. One of the targets for cAMP is a conserved cAMP-binding domain (CNB) found associated with a variety of effector domains/proteins such as protein kinase A (PKA), guanine-exchange factor protein (Epac), the cAMP-regulated bacterial transcription factors and cyclic nucleotide gated ion channels (1). In eukaryotes, the main intracellular target for cAMP is PKA (2–4). In the absence of cAMP, PKA exists as an inactive tetramer of catalytic (C) and regulatory (R) subunits. Binding of cAMP to the R-subunit of the holoenzyme induces conformational changes leading to its dissociation and unleashes the active C-subunit. The synthesis and degradation of cAMP are catalyzed by two classes of enzymes, adenylyl cyclases, which facilitate cAMP synthesis from ATP upon hormonal stimulation of G-protein-coupled receptors (5), and phosphodiesterases (PDEs), which catalyze the conversion of cAMP to 5′AMP and mediate signal termination (6) (Fig. 1). Apart from adenylyl cyclases, the superfamily of PDEs, comprising five cAMP-specific PDE families and numerous isoforms and splice variants, are directly involved in maintaining the duration and intensity of the cAMP response (6). Although extensive biochemical studies and structural biology of PDEs and PKA have elucidated the molecular basis for PDE enzymology as well as cAMP-dependent activation of PKA, little is known about how reassociation of the cAMP-bound R and C-subunits occurs in the cell and how PDEs cross regulate PKA to accelerate signal termination in cAMP signaling (Fig. 1). An additional level of complexity arises from the enormous diversity in isoforms of PKA and PDEs in eukaryotes. Four nonredundant R-subunit isoforms (RIα, RIβ, RIIα, and RIIβ) and three C-subunit isoforms (Cα, Cβ, and Cγ) are found in eukaryotic cells. All the R-subunit isoforms show a common domain organization consisting of an N-terminal dimerization/docking domain and two C-terminal cAMP-binding domains (CNB:A, CNB:B)(Fig. 2A) (3). Despite a conserved domain architecture, all of these isoforms show enormous differences in subcellular localization, tissue specificity, and function (7). Of these, RIα and Cα are the two isoforms that are distributed across all cell-types (8, 9). Furthermore, gene knockout studies have shown obligatory requirement for both RIα and Cα for normal growth and development of all cells (9). The superfamily of PDEs also shows wide differences in catalytic activity, tissue specificity and subcellular localization (6). It is evident that the subcellular localization of specific PDE and PKA families/isoforms must govern the duration and intensity of the cAMP signaling response across various subcellular compartments.

Fig. 1.

Overview of cAMP signaling and regulation of PKA. Adenylyl cyclases catalyze synthesis of cAMP from ATP whereas phosphodiesterases (PDEs) catalyze hydrolysis of cAMP to 5′ AMP. cAMP activates PKA by mediating dissociation of the PKA holoenzyme to release R and C-subunits via a largely well-understood mechanism. Little is known, on how cAMP-bound R-subunits reassociate with C-subunit to generate inactive PKA, and the potential role of PDEs in cross-talk with the R-subunits leading to signal termination.

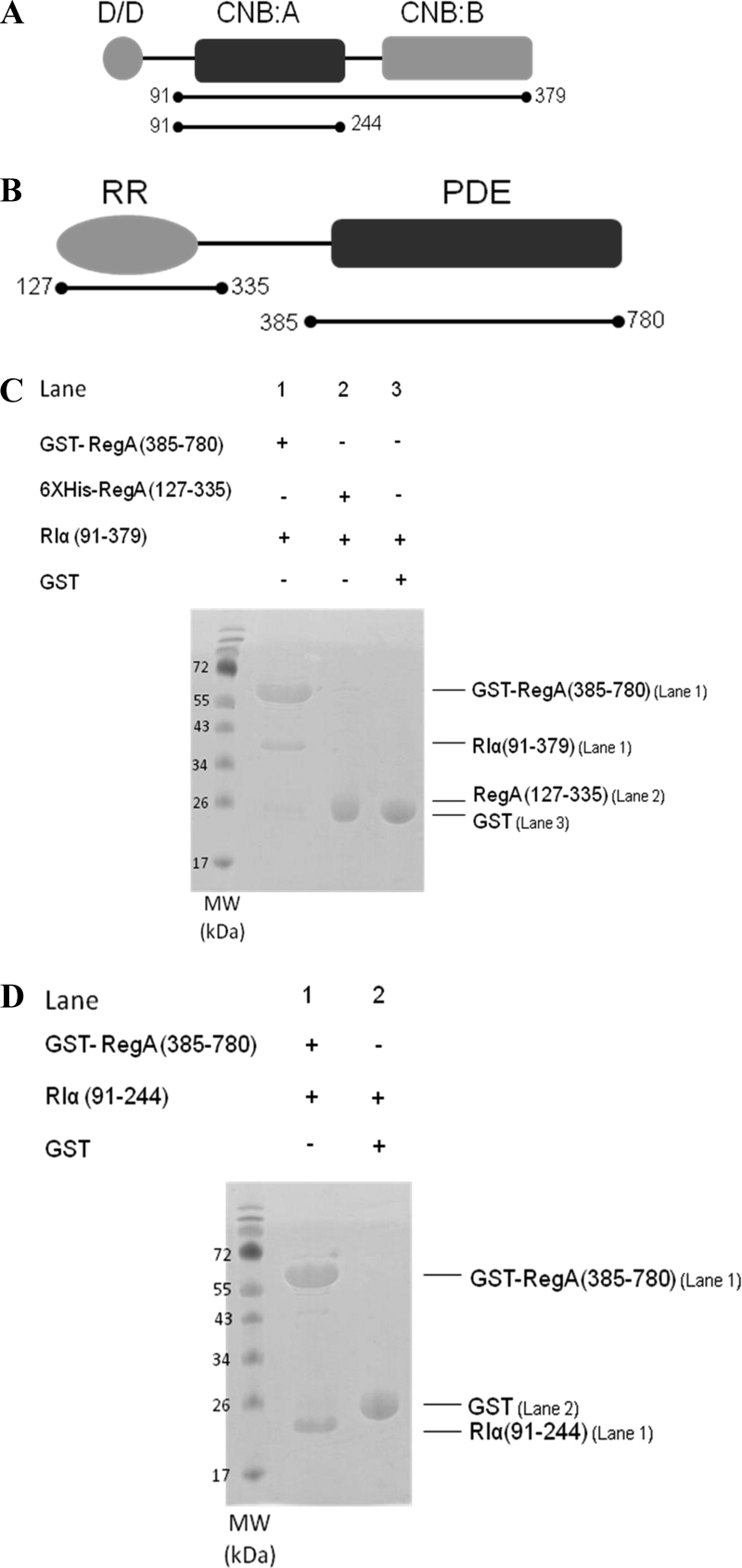

Fig. 2.

The catalytic PDE domain of RegA interacts with the cAMP binding domains of RIα. A, Domain organization of RIα showing an N-terminal dimerization/docking domain (D/D) in gray connected by a linker to two tandem cAMP-binding domains, CNB:A in black and CNB:B in gray. The deletion fragment RIα (91–244), is a minimal module that binds with high affinity to both cAMP as well as the C-subunit (52). B, Domain organization of RegA showing an N-terminal response regulator receiver domain (RegA (127—335)) in gray and a C-terminal phosphodiesterase catalytic domain (RegA (385–780)) in black. C, GST pull down of cAMP-free RIα (91–379) with the PDE catalytic domain, GST RegA (385–780) shows direct binding to cAMP-free RIα (91–379) (Lane 1). GST was used as control (Lane 3). Hexahistidine pull down of cAMP-free RIα (91–379) with hexahistidine tagged RegA (127–335) (Lane 2). D, GST pull down of cAMP-free RIα (91–244) with GST RegA (385–780) (Lane1). GST was used as control (Lane 2). (MW: Molecular weight marker). For clarity, all future references to RegA in the figures and figure legends denote the GST-tagged RegA (385–780) and all future references to RIα denote RIα (91–244) unless otherwise stated.

The discovery of protein kinase A anchoring proteins (AKAPs) (10), a class of anchoring proteins that tether the PKA R-subunits to different classes of signaling and target proteins, further underscore the importance of compartmentalization in cAMP signaling. AKAPs interact with the N-terminal dimerization domains of the R-subunits and function to bring elements of the cAMP signaling pathway in close proximity and to enable targeting to specific organelles. mAKAP (AKAP 450) is one AKAP that has been shown to bind both the RII isoform of the PKA R-subunit and PDE4D3 (11, 12) in which the proximity of PDEs with PKA would generate a single functional unit with tight regulation of cAMP signaling. It must be noted that nearly all the AKAPs discovered thus far preferentially interact with the RII isoforms of the R-subunit (13). Even the dual-specificity AKAPs (d-AKAPs) bind the RII isoform with a higher affinity than the RI isoform (14, 15).

There have also been a few examples of AKAP-independent colocalization of PDEs and PKA. PDE7A and its interactions with the PKA C-subunit (16) is one example. Another example describes interactions between the cAMP-binding domains of PKA RIα and a PDE, RegA from the eukaryote Dictyostelium discoideum (17). This species contains only a single RIα isoform of the PKA R-subunit. Furthermore, D. discoideum RIα is monomeric as it lacks the N-terminal third of the mammalian RIα sequence, including the N-terminal dimerization/docking domain, whereas the sequences of the cAMP-binding domains (CNB:A and CNB:B) are highly invariant among RIα across species (18). These indicate that the PDE-RIα interactions must involve the cAMP-binding domains and would therefore be independent of AKAPs. Earlier studies also showed that RegA was capable of interacting not only with RIα from D. discoideum but also with the monomeric N-terminal truncation mutant of mammalian (Bos taurus) RIα (RIα (91–379)) (17).

It has been assumed until now that reassociation of the PKA holoenzyme occurs through a reversal of the activation process in which C-subunit binding to cAMP-bound RIα facilitates dissociation of cAMP leading to regeneration of the holoenzyme (19). This is supported by evidence showing affinity of cAMP for the holoenzyme being significantly lower than that for free RIα (20). In such a process, PDEs would only play a passive role in hydrolyzing the cAMP released upon C-subunit binding and facilitate signal termination. Our study characterizing RIα-RegA PDE interactions reveals a novel mechanism highlighting an active role for PDEs in signal termination. Our comprehensive enzymological analysis of PDE-R-subunit complexes shows that PDEs are capable of hydrolyzing cAMP-bound to the R-subunit in addition to free soluble cAMP. This is achieved by two processes: a) PDEs mediate active dissociation of cAMP from R-subunits, b) Binding of the R-subunits activates PDE catalysis. This establishes a previously unknown function of RIα as an activator for PDEs, underscoring the importance of PDE-R-subunit cross talk in cAMP signaling. We have used amide hydrogen/deuterium (H/D) exchange mass spectrometry to map the interactions between RIα and RegA. Our results have enabled identification of residues critical for RIα-RegA interactions and show that RIα uses overlapping but distinct surfaces for mediating interactions with the C-subunit and PDEs. By catalyzing hydrolysis of cAMP-bound to the RIα, PDEs actively prime RIα for reassociation with the C-subunit and thus are critical for signal termination in cAMP signaling.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Unless otherwise mentioned all reagents were from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The expression vector pGEX-4T-1 was from GE (Chicago, IL); restriction endonucleases and DNA modifying enzymes were from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA); calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase was from Fermentas (Burlington, Canada). BL21 (DE3) E. coli strains were from Novagen (Madison, WI). Glutathione Sepharose 4B and NHS-activated Sepharose 4 Fast Flow were obtained from GE (Chicago, IL). TALON metal affinity resin was from Clontech Laboratories (Mountain view, CA), 8-AEA-cAMP and 8-Fluo-cAMP, a fluoresceine-modified analog of cAMP with the dye linked at position 8 of the adenine base spacer were from Biolog Life Science Institute (Bremen, Germany), Fluorescein-5-maleimide was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA), cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase assay kit was from BIOMOL (Plymouth Meeting, PA), trifluoroacetic acid, protein sequence analysis grade, was from Fluka BioChemika (Buchs, Switzerland), Poroszyme immobilized pepsin cartridge was from Applied Biosystems (Foster city, CA), Immobilized pepsin bead slurry and EZ-link maleimide polyethylene glycol2-Biotin reagent were from Thermo Scientific Pierce (Rockford, IL) and Streptavidin-agarose was from Novagen (Madison, WI).

Cloning and Expression of a C-Terminal Deletion Domain Mutant of RegA

Recombinant clones for expression of B. taurus PKA RIα and M. musculus PKA C-subunit in E. coli were from Dr. S. S. Taylor, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of California San Diego. The clones for RegA and RegA (127–335) were a gift from Dr. William Loomis, Center for Molecular Genetics, Department of Biology, University of California San Diego. A fragment of regA encoding the conserved PDE catalytic domain from residues 385–780 was subcloned into vector pGEX-4T-1 by standard molecular biology methods. A pair of forward and reverse oligonucleotide primers: 5′CGGGATCCAAGTTGATAAAGAATGATTCAGT-3′ and 5′-CGCGCTCGAGTAAAGGAGCGGTCGAAGAAGAT-3′ were synthesized for amplification of regA encoding amino acid residues 385–780 by PCR. The amplified DNA and the expression vector were digested separately by restriction endonucleases BamHI and XhoI, purified from agarose gel, and ligated by T4 DNA ligase. The pGEX4T-regA plasmid was transformed into E. coli strain BL21* (DE3) for protein overexpression.

Protein Expression and Purification

cAMP affinity chromatography resin for R-subunit purification was synthesized by coupling 8-AEA-cAMP to the NHS-activated Sepharose 4 Fast Flow ® beads according to manufacturer specifications (GE Life Sciences Singapore) (21). Both cAMP-bound and cAMP-free RIα (91–379) and RIα (91–244) were expressed and purified as described previously (22). The C-subunit of PKA was expressed and purified as described previously (23). Full length RegA and the receiver domain construct RegA (127–335) were expressed as hexahistidine tagged proteins and purified according to manufacturer specifications (Talon, Clontech laboratories). RegA (385–780) was expressed as a GST fusion protein in E. coli BL21*(DE3). The protein was purified using glutathione Sepharose 4B (GE Life Sciences) according to manufacturer specifications followed by size exclusion-gel filtration chromatography on an AKTA system (GE Life Sciences).

Pull-Down Assays

GST- tagged RegA (385–780) (10 nmol) was incubated with 50 μl bed volume of glutathione Sepharose beads for 30 min at room temperature (23 °C). The beads were then washed with binding buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol (BME)) to remove any unbound protein and proteins nonspecifically bound to the beads. Glutathione-immobilized GST-RegA (385–780) was subsequently incubated with 50 nmol of cAMP-free RIα (91–379) and cAMP-free RIα (91–244) in separate experiments. The beads were then agitated gently at room temperature (23 °C) for 1 h and rapidly washed 3–4 times with binding buffer. Protein was then eluted with elution buffer (10 mm reduced glutathione, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 5 mm BME) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (12%) and stained with Coomassie blue to test for co-elution of PKA R-subunit fragments with deletion domain fragments of RegA. A control experiment with GST alone was carried out in parallel. Hexahistidine tagged RegA (127–335) was immobilized on cobalt beads (Talon resin, Clontech Laboratories) and similar amounts of protein samples, beads and the same experimental conditions as above were used except that the elution buffer contained 150 mm imidazole pH 7.5 instead of glutathione.

Fluorescence Spectroscopy

In order to test the effect of RegA binding to fluorescein labeled R-subunit, we chose three single-site cysteine point mutations in RIα (91–244) (R92C, S145C and R239C) and labeled them with fluorescein maleimide (FM) as described earlier (22). The percentage of R-subunit labeled was determined spectrophotometrically using the following equation:

|

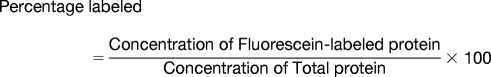

Concentration of fluorescein-labeled protein was calculated by measuring the absorbance at 497 nm (ε487 = 83 000 for Fluorescein maleimide) and the total protein concentration was estimated by the Bradford assay. Labeling efficiencies of ∼20%–25% were obtained. All fluorescence measurements were made on an LS 55 luminescence spectrophotometer, (Perkin Elmer). In preliminary experiments to estimate the affinities of cAMP-bound and cAMP-free RIα for RegA, 10 μm of FM labeled cAMP-bound and cAMP-free RIα (91–244) were incubated with a range of concentrations of GST-RegA (385–780) (1–128 μm). An excitation wavelength of 490 nm was used and changes in the intensity of emission of fluorescein at 518 nm were monitored. The experiment was carried out by setting both the excitation and emission slits at 2.5 nm with a scan speed of 100 nm/min. Both FM-labeled R92C and R239C mutants of RIα (91–244) showed concentration-dependent decreases in total fluorescence upon addition of increasing concentrations of RegA (385–780), whereas no changes in fluorescence were detected in S145C labeled RIα (91–244) with RegA. Plots of normalized relative fluorescence (F0/F) versus concentration of RegA (385–780) where, F0 and F are the fluorescence intensities at the emission maxima in the absence and presence of GST-RegA (385–780) respectively, best fit to an equation for one site-specific binding (Graph Pad Prism software version 5 (San Diego, CA)). The estimated KD was 16.6 ± 5.3 and 17.4 ± 3.6 μM for cAMP-bound and cAMP-free RIα (91–244) R239C and 18.0 ± 7.5 and 26.2 ± 6.8 μm for cAMP-bound and cAMP-free RIα (91–244) R92C respectively (data not shown). For accurate determination of dissociation constants it is necessary for the total concentration of one of the reactants to ideally be 10–100× lower than the measured dissociation constants (24). However in our experiments, the concentration of FM-labeled RIα (91–244) was only ∼twofold lower than our measured KD. Therefore in a second experiment, we repeated the fluorescence quenching studies using the lowest possible concentrations of FM-labeled protein that could be effectively measured under our experimental conditions. Here, a different batch of FM-labeled RIα (91–244) R239C, which showed better labeling than before (62.5%), was used at lower concentrations (0.5 μm) to monitor changes in fluorescence upon addition of GST-RegA (385–780) (concentration range 0.5–7.5 μm) (Fig. 3). Values for KD obtained were 1.6 ± 0.4 and 1.7 ± 0.7 μm for cAMP-bound and cAMP-free RIα (91–244) respectively but still only 3X greater than the concentration of FM-labeled RIα (91–244). The values we obtained therefore represent higher estimates of the dissociation constant. Calculation of a more accurate dissociation constant would require higher sensitivity of labeled probes and/or detection or labeling of both RegA and RIα. A control experiment with equimolar amounts of GST did not show any changes in fluorescence and suggested no independent binding of GST to RIα (91–244) (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

cAMP-bound and cAMP-free RIα bind RegA with identical affinities. Plot of relative fluorescence of fluorescein-labeled RIα (91–244) R239C (0.5 μm) and concentrations of RegA (0.5–7.5 μm) (Excitation wavelength: 490 nm, Emission wavelength: 520 nm). Y-axis shows normalized values of relative fluorescence where 100% represents the maximum value for F0/F. Open triangle cAMP-free RIα (Δ) and open inverted triangle (▿), cAMP-bound RIα. The curves were fit to the equation for one-site specific binding (Graph Pad Prism software version 5).

Phosphodiesterase Assay

Full-length RegA and GST RegA (385–780) were assayed for cAMP hydrolytic activity using a colorimetric cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase assay (BIOMOL, Plymouth Meeting, PA). Full-length RegA and GST RegA (385–780) (200 nm) were each separately incubated with 200 μm cAMP at room temperature (23 °C) over a time course spanning 10–60 min in assay buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2, and 5 mm BME) in a total reaction volume of 50 μl. The linked PDE assay used, measures PDE activity by monitoring the amount of product, 5′ AMP indirectly, where free inorganic phosphate generated by calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase by hydrolysis of 5′ AMP is detected by BIOMOL green reagent (malachite green) that interacts with free phosphate, which in turn increases absorbance at 620 nm. PDE reactions were quenched by addition of trichloroacetic acid to a final concentration of 7%. The samples were then centrifuged to remove denatured protein; phosphate in the supernatant was quantitated by adding 100 μl of BIOMOL green reagent and by measurement of the absorbance at 620 nm. A control experiment with GST in the presence of RIα (91–244) was carried out in parallel and showed no PDE activity.

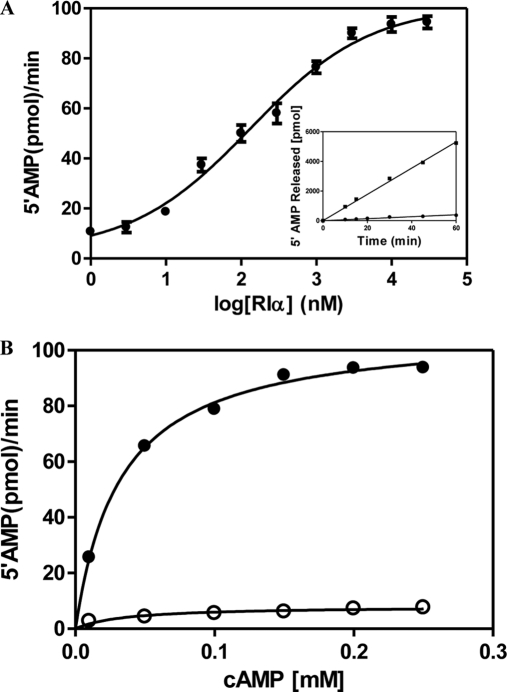

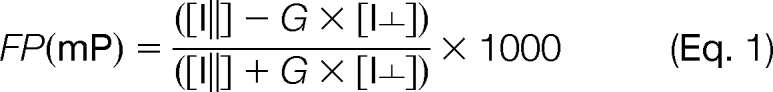

To measure RIα(91–244)-mediated activation of RegA, GST RegA(385–780) (50 nm) was incubated with a range of cAMP- free RIα (91–244) concentrations (1 nm–30 μm) and assayed for PDE activity (Fig. 4A). The maximal activity was seen under these conditions in the presence of 3 μm or greater cAMP-free RIα (91–244) with an EC50 for the activation equal to 0.13 μm. PDE assays were then carried out with three concentrations of GST RegA (385–780) (25, 50, and 100 nm) in the presence of 3 μm cAMP-free RIα (91–244) and the relative activity showed a linear relationship with the concentration of GST RegA (385–780) used (data not shown). GST RegA (385–780) alone (50 nm) and in the presence of 3 μm cAMP-free RIα (91–244) was then used to determine the kinetic parameters (Km and Kcat) by measuring activity at cAMP concentrations ranging from 10 μm to 250 μm (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

cAMP-free RIα is an activator of PDE catalysis. A, EC50 for cAMP-free RIα-mediated activation of RegA. Concentrations of RegA and cAMP were 50 nm and 200 μm respectively. Triplicate reactions were carried out at 30 °C for 15 min with a range of concentrations of cAMP-free RIα (1 nm–30 μm). The plot was fit to an equation describing a sigmoidal dose response curve (Activity versus Log Agonist) (Graphpad Prism version 5) and an EC50 of 132 nm was calculated. These results indicate that a maximal increase (∼ 13 X) in activity is seen when RegA is fully saturated with RIα. Inset shows PDE-mediated 5′AMP synthesis over time for free RegA and in the presence of RIα (3 μm). B, RIα activates RegA by increasing the Vmax of the phosphodiesterase reaction. PDE assays of RegA (50 nm) were carried out in the absence (○) or presence (●) of cAMP-free RIα (3 μm). Rates of 5′-AMP product formed were plotted versus a range of cAMP concentrations and fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation (Graph Pad Prism software version 5). The Vmax for the PDE reactions catalyzed by RegA was 8.1 ± 0.5 pmol 5′AMP released/min (kcat = 3.2 min−1) and that for RegA + RIα is 107.6 ± 1.3 pmol 5′AMP released/min (kcat = 43.0 min−1); The Km for RegA was calculated to be 35.0 μm and for RegA + RIα, 32.5 μm. Data are average measurements from three replicate experiments. Error bars indicating standard deviation are too small to be clearly seen on the graph.

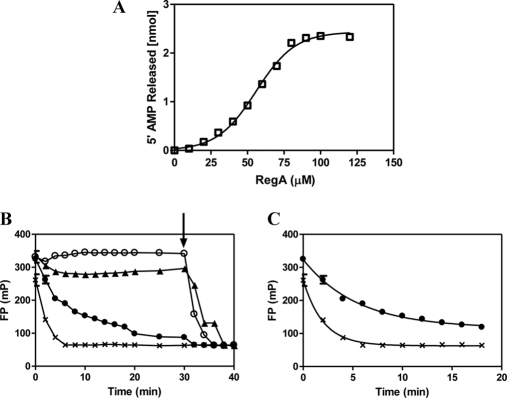

To test the ability of RegA to hydrolyze cAMP bound to RIα (91–244) rather than cAMP in solution, we used cAMP-bound RIα (91–244) as a sole substrate for RegA. Fifty micromolar cAMP-bound RIα (91–244) was incubated for 30 min at 30 °C with different concentrations of GST- RegA (385–780) (0–120 μm) in assay buffer with added CIAP (1 u, Fermentas) to a final volume of 50 μl. The reaction was quenched by addition of trichloroacetic acid to a final concentration of 7%. The samples were then centrifuged to remove denatured protein; phosphate in the supernatant was quantitated by adding 100 μl of BIOMOL green reagent and by measurement of the absorbance at 620 nm (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

A, RegA catalyzes hydrolysis of cAMP-bound to RIα. Phosphodiesterase activity of RegA was measured by a colorimetric assay described in materials and methods using cAMP-bound RIα as substrate. 50 μm cAMP-bound RIα was incubated with different concentrations of RegA (0–120 μm). Plot shows PDE activity as a function of concentration of RegA (□). The plots were fit to an equation describing a sigmoidal dose response curve (Activity versus Log Agonist) (Graphpad Prism version 5). B, RegA mediates dissociation of cAMP from RIα. Dissociation of 8-Fluo-cAMP from RIα (7.2 μm) was monitored by measuring the fluorescence polarization (FP) under different conditions, (○) control: Buffer A (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 5 mm BME), (●) presence of unlabeled cAMP (Buffer A, 1 mm cAMP), (▴) presence of C- subunit (36 μm), (Buffer A, 0.2 mm ATP), (X) presence of RegA (36 μm) (Buffer A). FP measurements were as described in materials and methods. FP values are plotted versus time, arrow indicates the time point (30 min) of addition of RegA (36 μm) to all samples. C, RegA increases dissociation rates of 8-Fluo-cAMP from RIα. Dissociation rates were calculated by fitting the data for the early time points (0–18 min) to an equation describing one phase exponential decay using Graph Pad Prism software version 5 (San Diego, CA). Data are average measurements from three independent experiments. Error bars indicating standard deviation are too small to be clearly seen on the graph.

Fluorescence Polarization Assay for cAMP Dissociation

To determine if RegA interactions facilitate dissociation of cAMP from RIα, we carried out a fluorescence polarization (FP) assay using 8-Fluo-cAMP saturated RIα (91–244) as described (25). This assay allows measurement of the rate of dissociation/competitive displacement of 8-Fluo-cAMP from RIα by cAMP, because FP of bound fluorescent analog is greater than for analog free in solution. FP was calculated by the equation:

|

FP (mP) is the fluorescence polarization measured in millipolarization units, I∥ is the signal in parallel mode,I⫠ is the signal with in perpendicular mode and G represents the G-factor or correction factor for the instrument. A Biotek Synergy 4 Multi-Detection microplate reader (Winooski, VT) was used in FP mode for the plate reader assays. The excitation and emission wavelengths used were 485 nm and 528 nm, respectively with a bandwidth of 20 nm with an instrument G-factor of 0.87. The 96-well black plates were from Greiner (Germany). The FP signals for 7.2 μm of 8-Fluo-cAMP bound RIα (91–244) in buffer A (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 5 mm BME) were monitored with and without (i) unlabeled cAMP (1 mm), (ii) C- subunit with 0.2 mm ATP (36 μm), and (iii) GST-RegA (385–780)(36 μm). FP measurements were taken at time intervals of 2 min for 30 min. In all samples 36 μm of GST-RegA (385–780) was added at 30 min, and FP measurements were obtained until 40 min (Fig. 8B). Data from early time points (0–18 min) were fit to a one phase exponential decay equation using Graph Pad Prism software version 5 (San Diego, CA) (Fig. 8C).

Amide Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry

cAMP-free RIα (91–244): GST-RegA (385–780) complex eluted from the pull-down experiment described above was purified and concentrated to 6.9 mg/ml protein, based on Bradford assay, using vivaspin concentrators (Sartorius Stedim Biotech GmbH, Goettingen, Germany). We believe that in this sample containing a molar excess of GST-RegA (385–780), all the RIα (91–244) would be fully saturated with GST-RegA(385–780) and enable mapping of RegA-RIα (91–244) interactions.

Deuterium exchange was carried out by mixing 2 μl of the samples in storage buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 5 mm BME) with 28 μl of D2O (99.90%) resulting in a final concentration of 93.3% deuterated buffer A (20 mm Tris-HCl, pHread 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 5 mm BME). Exchange was carried out at 20 °C for various times (0.5, 1, 2, 5, and 10 min). The exchange reaction was quenched by adding 30 μl of prechilled 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid to get a final pHread of 2.5. A 50 μl aliquot of the quenched sample (∼14 μg protein sample) was then injected on to a chilled nano-Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography sample manager (beta test version, Waters, Milford, MA) as previously described (26). The sample was washed through a 2.1 × 30 mm immobilized pepsin column (Porozyme, ABI, Foster City, CA) using 100 μl/min 0.05% formic acid in water. The digest peptides were trapped on a 2.1 × 5 mm C18 trap (ACQUITY BEH C18 VanGuard Pre-column, 1.7 μm, Waters, Milford, MA). Peptides were eluted using an 8%–40% gradient of acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid at 40 μl/min, supplied by a nanoACQUITY Binary Solvent Manager (Waters, Milford, MA), on to a reverse phase column (ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 Column, 1.0 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm, Waters, Milford, MA) for resolution. Peptides were detected and mass measured on a SYNAPT HDMS mass spectrometer (Waters, Manchester, UK) acquiring in MSE mode (27, 28).

Peptides were identified from MSE data of undeuterated samples using ProteinLynx Global Server (PLGS 2.4 (beta test version))(Waters, Milford, MA) (29, 30). Identifications were only considered if they appeared at least twice out of three replicate runs. These identifications were mapped on to subsequent deuteration experiments using prototype custom software (HDX browser, Waters, Milford). Data on each individual peptide at all time points were extracted using this software, and exported to the HX-Express program (31).

Continuous instrument calibration was carried out with Glu-Fibrinogen peptide at 100 fmol/μl. We also visually analyzed the data to ensure only well-resolved peptide isotopic envelopes were subjected to quantitative analysis. The lowest signal-to-noise ratio among all peptides analyzed was six. HX-express generated centroid values for the isotopic envelopes of all the peptides analyzed, which reflected the average mass of the peptide. The difference between the average masses of the deuterated and undeuterated peptide gave the average number of deuterons exchanged. The N-terminal amide of all the peptide fragments exchanged too rapidly to measure and was not included in calculation of average deuterons exchanged (31). A control experiment was carried out to calculate the deuterium back exchange loss during the experiment by incubating cAMP-free RIα (91–244) with deuterated buffer A for 24 h at room temperature (20 °C). Even following extended deuteration, RIα (91–244) still showed some solvent inaccessible and ordered regions that were not completely deuterated. For an accurate measurement of back exchange loss, we therefore focused only on peptides from within highly solvent exchangeable regions of the protein, identified as those regions that show the greatest relative exchange at shorter time points (10 min exchange). The region in RIα (91–244) spanning residues 111–130 is a highly solvent exchangeable region and all 3 overlapping peptides used for calculations of back exchange span this region and showed nearly maximal exchange in ligand-free RIα(91–244) following 10-min deuterium exchange and would represent fully deuterated samples following 24 h exchange. An average deuteration back exchange of 32.8 ± 1.0% was calculated from average back exchange values for three peptides: RIα (111–123) (m/z = 547.65) (back exchange = 34.4%), RIα (111–119) (m/z = 559.34) (back exchange = 33.7%) and RIα (111–126) (m/z = 632.701) (back exchange = 30.4%). All deuterium exchange values reported were corrected for a 32.8% back exchange by multiplying the raw centroid values by a multiplication factor of 1.49 (32). Kinetic plots of deuteration for all peptides from RIα (91–244) alone and bound to RegA were made and these fit best to a one phase association model accounting for deuterons exchanging at a rapid rate (mainly solvent-accessible amides) (33). Parallel amide H/D exchange experiments were carried out and measured by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry to provide additional sequence coverage (Supplementary information).

Pull-down Assay with Immobilized cAMP-bound RIα (91–244)

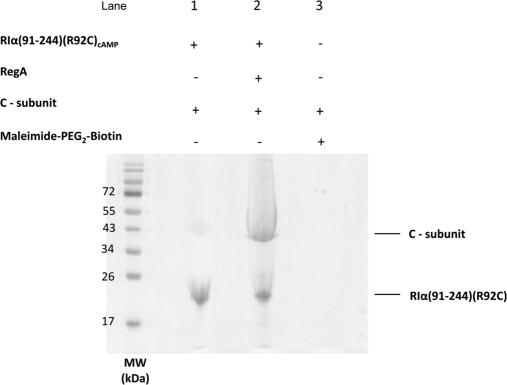

To test if RegA primed RIα for reassociation with C-subunit, immobilized cAMP-bound RIα (91–244)(R92C) alone and incubated with RegA was used in a pull-down assay. Immobilized RIα (91–244)(R92C) was prepared by reacting it with EZ-Link Maleimide-polyethylene glycol2-Biotin (spacer arm of 29.1 Å) as per manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Scientific). A 10-nmol aliquot of maleimide-polyethylene glycol2-Biotin modified cAMP-bound RIα (91–244)(R92C) was bound to streptavidin-agarose beads (50 μl) (Novagen) by incubation for 20 min at room temperature (23 °C) to yield RIα (91–244) immobilized on agarose beads. The beads were then washed three times with Buffer B (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2 and 0.2 mm ATP) to remove any unbound protein. Two 25-μl aliquots of RIα (91–244)(R92C) bound beads were incubated with 50 nmol of C-subunit in buffer B and 50 nmol of C-subunit plus 50 nmol of GST-RegA (385–780) in buffer B separately for 30 min at room temperature (23 °C). The beads were then collected by centrifugation and washed 4 times with buffer B. A 15-μl aliquot of 1× SDS-PAGE loading dye was added to the beads, boiled at 95 °C for 10 min and analyzed on 12% SDS-PAGE (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

RegA primes RIα for reassociation with C-subunit; Biotinylated cAMP-bound RIα (91–244)(R92C) was bound to Streptavidin-agarose and incubated with C-subunit in the presence and absence of RegA as described in materials and methods, the samples were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Lane 1: C-subunit and immobilized RIα in the absence of RegA; Lane 2: C-subunit and immobilized RIα in the presence of RegA; Lane 3: C-subunit and Maleimide-polyethylene glycol2-Biotin-Streptavidin agarose beads (control).

RESULTS

Deletion Mutagenesis Indicates that the Catalytic Domain of RegA Mediates AKAP-independent Interactions with the CNB:A Domain

To further characterize interactions between RIα and RegA (17), we set out to define the specific domains involved in mediating these interactions by deletion mutagenesis of both RegA and RIα. RIα (91–244), containing a single cAMP binding domain (CNB:A), is a minimal module that has been used to examine the molecular details of the R-C interface (34) as well as to probe cAMP interactions with RIα (35). This minimal construct consists of two subdomains: an α- subdomain composed entirely of α- helices, which forms the interface with the C-subunit (34) and a β-subdomain that contains a conserved cAMP-binding pocket (1, 35). We therefore set out to characterize the binding of RegA to RIα (91–244) having confirmed this interaction by size-exclusion chromatography (data not shown).

At least two domains are predicted from the amino acid sequence of RegA, i) an N-terminal regulatory receiver domain (RR) bearing high homology to response regulators (36) and ii) a C-terminal catalytic domain highly homologous to catalytic domains of all PDEs (6) (Fig. 2B). We were interested in testing which of these two conserved domains mediated interactions with RIα and so generated deletion domain constructs of RegA; RegA (127–335) to span the receiver domain and RegA (385–780) to span the catalytic domain. Each of these domain constructs were tested for their ability to interact with the larger deletion mutant of R-subunit, RIα (91–379) containing both CNB:A and CNB:B by a pull-down assay. We found that GST RegA (385–780) alone but not RegA (127–335) interacted with cAMP-free RIα (91–379) (Fig. 2C). We additionally carried out pull-down assays with cAMP-free RIα (91–244) and observed interactions with GST RegA (385–780)(Fig. 2D). Our results indicate that the CNB:A domain is sufficient for mediating interactions with the catalytic domain of RegA. GST alone did not bind to either RIα construct. For clarity, all future references to RegA in the text denote GST-tagged RegA(385–780) and all future references to PKA RIα denote RIα (91–244) unless otherwise stated.

Measurement of Binding Affinity of RIα to RegA by Fluorescence Quenching

In order to test the effect of RegA binding to fluorescein-labeled RIα, we chose three single site cysteine point mutations in RIα (91–244) (R92C, S145C, and R239C) and labeled them with fluorescein maleimide (FM) as described earlier (22). Quenching of fluorescence signal upon addition of RegA seen with two mutants, RIα (91–244) (R92C) and RIα (91–244) (R239C) was followed to calculate estimated dissociation constants (KD) as described in materials and methods. Plots of fluorescence quenching of cAMP-free and cAMP-bound FM-labeled RIα (91–244) R239C by RegA were nearly identical with dissociation constants, KD = 1.7 μm ± 0.7 and KD = 1.6 μm ± 0.4 for cAMP-bound and cAMP-free RIα determined by nonlinear curve fitting to equation for one site-specific binding (Graph Pad Prism software version 5)(Fig. 3). Because the concentration of labeled RIα (91–244) R239C is only 3× fold lower than our measured value for the KD, when it should ideally be between 10- and 100-fold lower than the KD, the calculated KD values represent upper limits for the true affinities of the cAMP-bound and cAMP-free RIα complexes (24).

RIα Binding Induces a 13× Increase in RegA Phosphodiesterase Activity

We next set out to measure the functional effects of RIα binding on PDE activity of RegA. The catalytic domain of RegA retained the same level of PDE activity as full-length RegA (Supplemental Fig. 1). This is consistent with previous studies showing deletion of the N-terminal receiver domain and generation of a GST-fusion catalytic domain did not alter the PDE activity of RegA (37). We then tested the effects of cAMP-free RIα binding on PDE activity of RegA, by measuring the activity of RegA (50 nm) alone and with a range of concentrations of RIα from 1 nm to 30 μm RIα (Fig. 4A). Maximal activity was seen in the presence of 3 μm or greater RIα with an EC50 for the activation to be 0.13 μm. Although the dissociation constant for RegA-RIα by fluorescence quenching was estimated to be less than 1.5 μm, the EC50 values obtained from the reaction provide a more accurate measurement of the affinity as it pertains to the RIα-dependent activation of RegA PDE catalysis. These results showed further that RIα binding induces a ∼13× fold enhancement in PDE catalysis of RegA. There was a linear relationship between the activity of RegA in the presence of excess RIα, with the total concentrations of RegA used, and this enabled us to carry out cAMP saturation kinetics of RegA alone and in the presence of 3 μm RIα. The plots were fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation (Graph Pad Prism version 5) as described in Materials and Methods. These showed that the basis for the ∼13× fold enhancement of PDE catalysis by RIα was through direct effects on the catalytic turnover rates (kcat = 3.2 min−1 for RegA and 43.0 min−1 for the RegA-RIα complex) whereas the Michaelis constants (KmcAMP = 35.0 μm for RegA and 32.5 μm for RegA-RIα complex) were nearly identical (Fig. 4B).

Mapping RIα-RegA Interactions by Amide H/D Exchange Mass Spectrometry

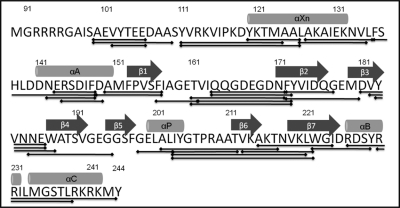

Amide hydrogen/deuterium (H/D) exchange mass spectrometry is an ideal method to monitor protein-protein interactions in solution and is especially suitable for mapping protein interfaces (38). In this study, we used amide H/D exchange coupled to pepsin digestion and LC-ESI-QTOF mass spectrometry to specifically probe the solvent accessibility (39) of the RIα surface in the free state and in complex with RegA, by monitoring amide H/D exchange over a 0.5–10 min time period. In the ESI-QTOF MS experiments, the identities of the pepsin digest fragments of RIα were determined by PLGS v.2.4 program (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA) and a total number of 36 peptides corresponding to 90% of the sequence of RIα(91–244) were identified (Fig. 5) and centroid analysis on all the peptides was carried out by the program HX-express as described in materials and methods. The variability in centroid values between replicate measurements was less than 1% for most peptides and less than 10% for all peptides.

Fig. 5.

Amino acid sequence of RIα(91–244) showing secondary structure elements with boundaries. Solid lines indicate the 36 pepsin digest fragments analyzed in the study with a total sequence coverage of ∼90%.

Table I summarizes the extent of deuteration for all the 36 peptides from which quantitative data were obtained. The data are reported as the average number of deuterons incorporated following 10 mins for three independent determinations. Kinetic plots of deuteration for all peptides from RIα(91–244) alone and bound to RegA were generated and these fit best to a one phase association model (Graph Pad Prism software version 5) accounting for deuterons exchanging at a rapid rate (mainly solvent-accessible amides) (33). For three of the peptides that showed large differences between cAMP-free RIα and RegA-bound RIα, the plots along with isotopic envelopes are shown in Fig. 6 and plots of all remaining peptide fragments are shown in Supplemental Fig. 4. There was no significant difference observed between the exchange following 10 mins of deuterium exchange or from calculation of the maximum number of deuterons exchanged determined from fitting plots of the time course of deuteration, either method of data presentation resulting in the same conclusion (40, 41).

Table I. Summary of H/D exchange data for cAMP-free RIα(91–244) and cAMP-free RIα(91–244):RegA. Averages and standard deviations were calculated with measurements from three independent experiments.

| No. | Pepsin digest fragments of RIα (91–244) | Charge | Residue nos. | Maximum exchangeable amides | Maximum deuterons exchanged after 10 min |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cAMP-free RIα(91–244) | cAMP-free RIα(91–244): RegA | |||||

| (m/z) | (z) | (Mean ± S.D.) | (Mean ± S.D.) | |||

| 1 | AEVYTEE (840.36) | 1 | 100–106 | 6 | 4.6 ± 0.12 | 4.6 ± 0.15 |

| 2 | AEVYTEEDAA (1097.51) | 1 | 100–109 | 9 | 5.5 ± 0.21 | 5.3 ± 0.17 |

| 3 | VYTEE (640.28) | 1 | 102–106 | 4 | 2.3 ± 0.06 | 2.3 ± 0.06 |

| 4 | YVRKVIPKDYKTM (547.65) | 3 | 111–123 | 11 | 8.6 ± 0.28 | 8.3 ± 0.21 |

| 5 | YVRKVIPKDYKTMAA (595.01) | 3 | 111–125 | 13 | 9.8 ± 0.38 | 10.2 ± 0.21 |

| 6 | YKTMAA (684.34) | 1 | 120–125 | 5 | 4.2 ± 0.12 | 3.9 ± 0.09 |

| 7 | LAKAIEKNV (493.31) | 2 | 126–134 | 8 | 4.4 ± 0.12 | 4.1 ± 0.12 |

| 8 | AKAIEKNVL (493.31) | 2 | 127–135 | 8 | 4.4 ± 0.12 | 4.1 ± 0.12 |

| 9 | FSHLDDNERSDIF (797.86) | 2 | 136–148 | 12 | 3.1 ± 0.06 | 2.9 ± 0.12 |

| 10 | NERSDIF (880.41) | 1 | 142–148 | 6 | 1.8 ± 0.07 | 1.4 ± 0.23 |

| 11 | ERSDIF (766.37) | 1 | 143–148 | 5 | 0.8 ± 0.06 | 0.8 ± 0.07 |

| 12 | RSDIFD (752.36) | 1 | 144–149 | 5 | 0.5 ± 0.03 | 0.5 ± 0.06 |

| 13 | DAMFPVSF (913.41) | 1 | 149–156 | 6 | 1.1 ± 0.03 | 1.0 ± 0.00 |

| 14 | AMFPVSF (798.39) | 1 | 150–156 | 5 | 1.2 ± 0.07 | 1.1 ± 0.03 |

| 15 | FIAGET (637.33) | 1 | 156–161 | 5 | 0.4 ± 0.03 | 0.3 ± 0.07 |

| 16 | TVIQQGDEGDN (1175.54) | 1 | 161–171 | 10 | 6.0 ± 0.07 | 4.5 ± 0.07a |

| 17 | TVIQQGDEGDNF (661.80) | 2 | 161–172 | 11 | 5.4 ± 0.10 | 3.7 ± 0.15a |

| 18 | VIQQGDEGDNF (1221.58) | 1 | 162–172 | 10 | 5.4 ± 0.09 | 4.2 ± 0.15a |

| 19 | QQGDEGDN (862.32) | 1 | 164–171 | 7 | 4.6 ± 0.03 | 3.7 ± 0.09a |

| 20 | QQGDEGDNF (1009.39) | 1 | 164–172 | 8 | 4.7 ± 0.10 | 3.4 ± 0.09a |

| 21 | FYVIDQ (784.39) | 1 | 172–177 | 5 | 0.4 ± 0.03 | 0.3 ± 0.03 |

| 22 | FYVIDQGEM (1101.50) | 1 | 172–180 | 8 | 1.5 ± 0.07 | 1.2 ± 0.10 |

| 23 | DVYVNNE (852.37) | 1 | 181–187 | 6 | 2.3 ± 0.09 | 1.9 ± 0.09 |

| 24 | VYVNNE (737.35) | 1 | 182–187 | 5 | 2.5 ± 0.20 | 2.1 ± 0.03 |

| 25 | YVNNEW (824.36) | 1 | 183–188 | 5 | 3.0 ± 0.12 | 2.5 ± 0.07 |

| 26 | NEWATSVGEG (525.22) | 2 | 186–195 | 9 | 4.3 ± 0.12 | 4.2 ± 0.09 |

| 27 | GELAL (502.29) | 1 | 199–203 | 4 | 3.0 ± 0.09 | 1.0 ± 0.09a |

| 28 | ALIYGTPRAATVKAKT (554.33) | 3 | 202–217 | 14 | 7.9 ± 0.25 | 4.0 ± 0.03a |

| 29 | IYGTPRAAT (475.26) | 2 | 204–212 | 7 | 5.2 ± 0.13 | 2.2 ± 0.09a |

| 30 | IYGTPRAATVKAKTNVK (606.70) | 3 | 204–220 | 15 | 7.0 ± 0.15 | 3.2 ± 0.12a |

| 31 | IYGTPRAATVKAKTNVKL (644.39) | 3 | 204–221 | 16 | 7.9 ± 0.24 | 3.7 ± 0.09a |

| 32 | VKAKTNVKL (500.83) | 2 | 213–221 | 8 | 1.3 ± 0.06 | 0.9 ± 0.00 |

| 33 | AKTNVKLWG (508.80) | 2 | 215–223 | 8 | 1.7 ± 0.03 | 1.7 ± 0.03 |

| 34 | WGIDRDS (424.70) | 2 | 222–228 | 6 | 1.8 ± 0.03 | 1.9 ± 0.26 |

| 35 | RDSYRRILMGSTLRKRKM (1134.10) | 2 | 226–243 | 17 | 10.1 ± 0.03 | 7.4 ± 0.22a |

| 36 | RRILMGSTL (523.81) | 2 | 230–238 | 8 | 3.3 ± 0.12 | 3.0 ± 0.00 |

a Peptides showing significant differences in exchange between RIα (91–244) and RIα (91–244)-RegA complex.

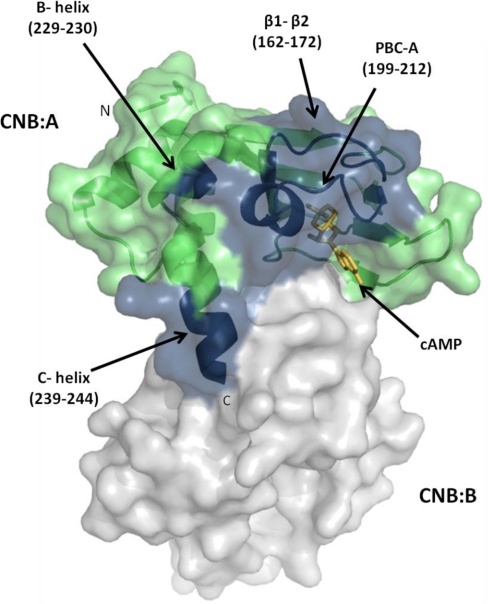

Fig. 6.

A, ESI-QTOF mass spectra for a peptide spanning RIα(202–217) showing decreased exchange in the RIα–RegA complex. (i) The isotopic envelope for the same peptide from RIα alone following 10 min deuteration (ii) The isotopic envelope for the same peptide from RIα:RegA following 10 min deuteration; (iii) Undeuterated sample. B, Time course of deuterium exchange for residues 202–217 fit to an equation for one-phase association (Graph Pad Prism software version 5 (San Diego, CA)). Open square (□), apo RIα; Closed square (■), RIα:RegA complex. C, ESI-QTOF mass spectra for the peptide RIα (162–172) showing decreased exchange in the RIα:RegA complex. (i)–(iii) are same as described in 6A. D, Time course of deuterium exchange for residues 162–172, symbols are as in 6B. E, ESI-QTOF mass spectra for the peptide RIα (226–243) showing decreased exchange in RIα:RegA. (i)–(iii) are as in 6A. F, Time course of deuterium exchange for residues 226–243. Symbols are as in 6B. The data showed very low variability (< 1% for most peptides) when replicate independent measurements were compared. This is reflected in the error bars, some of which are too small to be clearly seen on the graph.

Parallel amide exchange experiments were also carried out and measured by MALDI-TOF MS. Although the primary sequence coverage obtained was lower than from the ESI-QTOF MS analysis, there was one peptide in the MALDI-TOF MS analysis, that provided information on the C terminus of RIα (91–244) (residues 239–244), missing in coverage from the ESI-QTOF MS analysis. Results from analysis of other peptides were entirely consistent with the ESI-QTOF MS analysis (Supplemental Figs. 2, 3). From a combination of the ESI-QTOF MS and MALDI-TOF MS data, three clusters of overlapping peptides showing significantly decreased exchange in the complex compared with unbound RIα were identified and these regions are further discussed below.

Three Regions on RIα showed Decreased Solvent Accessibility in the RegA-RIα Complex: Phosphate Binding Cassette, β-strands 1–2 and α:B-C-helices

An important region of the protein where RegA binding caused decreased deuterium exchange was the region spanning the phosphate binding cassette (PBC) (Figs. 6A, 6B). Interestingly, this region is the binding site for cAMP and contains critical and invariant cAMP interaction residues including Glu200 and Arg209 (42). Subtractive analysis of peptides 28–31 from Table I:- residues 202–217, 204–212, 204–220, and 204–221 spanning the PBC showed decreased solvent accessibility corresponding to protection of three backbone amide deuterons that can be localized to residues 205–212. Peptide 27 in Table I spanning residues 199–203 showed decreased solvent accessibility corresponding to protection of two backbone amide deuterons.

A second region spans the β-strands 1, 2, and the loop connecting them. Subtractive analysis of overlapping peptides 16–20 from Table I: residues 161–171, 161–172, 162–172, 164–171, and 164–172 in this region showed protection of nearly 1.5 backbone amides that are localized to residues 162–172 (Figs. 6C, 6D).

A third region where we observed decreased exchange in the RegA-RIα complex is the C-terminal end of the C-helix spanning residues 226–243 (Figs. 6E, 6F). Subtractive analysis of three overlapping peptides in this region (peptides 34–36 in Table I: residues 226–243, 222–228, and 230–238) allowed us to localize the changes to segments within these peptides. Because there were no observable differences in exchange in the peptides, 222–228 and 230–238, the observed 2.7 deuterons protected in residues 227–243 is localized to residues 229, 230, and/or residues 239–243. MALDI-MS analysis (Supplemental Fig. 3, Table I) showed a protection of 1 deuteron in residues 240–244. All these regions map onto a contiguous surface on the structure of RIα and highlight the regions on RIα that are essential for binding RegA (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Amide H/D exchange mass spectrometry data mapped on to the crystal structure (surface representation) of cAMP-bound RIα (113–379) (PDB ID: 1RGS), CNB:A is in green and CNB:B is in gray (35). The phosphate binding cassette (PBC-A) (residues 199–212), B-helix (residues 229, 230), C-helix (residues 239–244) (From subtractive analysis and with amide exchange MALDI-TOF MS data) and 1 segment from the β-subdomain (residues 162–172) showed decreased exchange in the RIα:RegA complex. cAMP is yellow and protected regions are blue. Structure of RIα (113–379) is displayed using Pymol (DeLano Scientific, Mountain View, CA).

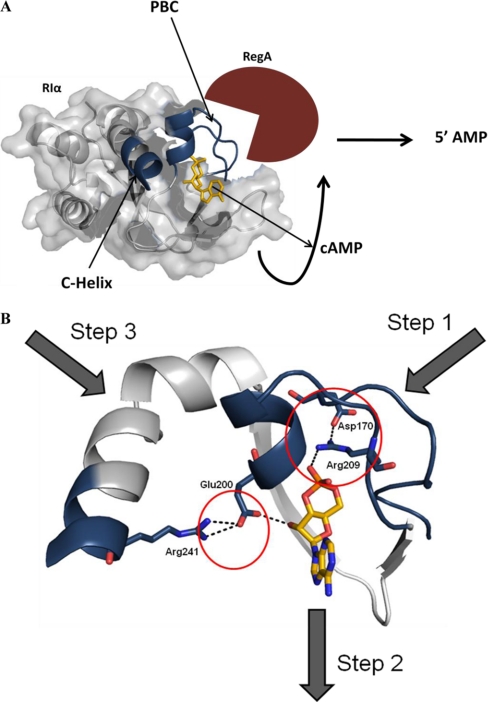

RegA Catalyzes Hydrolysis of cAMP-bound to RIα

The crystal structure of cAMP-bound RIα (PDB:1RGS) shows that the highly conserved PBC provides an important hydrophobic environment for cAMP, shielding it from intracellular phosphodiesterases (21, 43). Because we identified the PBC as one of the regions mediating interactions with RegA, we set out to test if the catalytic domain of RegA could hydrolyze cAMP bound to RIα. We carried out PDE assays with variable concentrations of RegA (0 to 120 μm) with constant concentrations (50 μm) of cAMP-bound RIα (Fig. 8A). We observed that RegA is able to hydrolyze bound cAMP at a rate far slower than the rate of RegA hydrolysis of cAMP in solution (an average rate of 0.015 per min for bound cAMP compared with kcat = 3.2 min−1 for cAMP in solution by RegA and 43.0 min−1 for cAMP in solution by RegA-RIα). Furthermore, a plot of PDE activity and variable concentrations of RegA catalytic domain fit best to a sigmoidal curve. This together with the slower activity seen with bound cAMP suggested that RegA-mediated hydrolysis of bound cAMP proceeded as a two-step reaction. Binding of RegA leads to dissociation of bound cAMP first followed by PDE-dependent cAMP hydrolysis.

To test this further we used a fluorescent analog of cAMP, 8-Fluo-cAMP, which has been shown to have similar binding affinities to RIα as cAMP (44) and is highly resistant to PDEs as well (manufacturer's sheet, Biolog, Bremen, Germany) in a fluorescence polarization (FP) assay for measuring cAMP dissociation as described in Materials and Methods (25) (Fig. 8B, 8C). There was no spontaneous dissociation of 8-Fluo-cAMP from RIα over the duration of the experiment consistent with the high affinity of cAMP to RIα (20). Addition of RegA following a 30 min incubation showed a drop in FP indicative of RegA-mediated dissociation of bound 8-Fluo-cAMP. Any effect of addition of RegA must only be because of dissociation of 8-Fluo-cAMP because this analog is resistant to PDE hydrolysis (Biolog Inc., specifications). We additionally verified that RegA was unable to hydrolyze 8-Fluo-cAMP under the conditions of our experiment. In the presence of 1 mm unlabeled cAMP, we calculated the intrinsic off-rate for cAMP to be 0.18 min−1 (Fig. 8C). RegA increases the rate of cAMP dissociation even in the absence of excess cAMP (koff = 0.50 min−1). The rate of RegA-mediated dissociation of cAMP is thus 2.8-fold greater than the intrinsic off-rate of cAMP seen only in the presence of excess cAMP. We also compared the kinetic off-rates in the presence of C-subunit. Under the conditions of the assay, the C-subunit would be predicted to be bound to cAMP-RIα in a ternary complex (KD = 0.2 μm for R-cAMP:C (22, 45) and KD = 2.9 μm of cAMP for holoenzyme (20) so what we observed here is a decrease in FP that potentially reflects increased dynamics of cAMP whereas still bound to the regulatory subunit in a ternary complex (20) rather than dissociation. This is confirmed by our observation that the FP signal dropped upon further addition of RegA to our sample (Fig. 8B). Thus the C-subunit primarily weakens the binding of cAMP to RIα and stays bound to it in a ternary complex (KD = 0.2 μm,(22, 45) whereas RegA mediated active dissociation of cAMP and catalyzed hydrolysis of the released cAMP.

RegA Primes RIα(91–244) for Reassociation with C-Subunit

Our results clearly showed that RegA binding to cAMP-bound RIα mediates dissociation of bound cAMP followed by hydrolysis, generating cAMP-free RIα bound to RegA. We then set out to test the effects of addition of C-subunit on this complex. We immobilized RIα using a specific biotin-maleimide tag covalently attached to RIα at residue 92 bound to streptavidin-agarose beads as described in materials and methods. Our results indicate that the C-subunit binds strongly to cAMP-free RIα and displaces RegA whereas it binds poorly to the cAMP-bound RIα that is not treated with RegA (Fig. 9). These results together with the FP studies show that RegA binding to RIα facilitates dissociation of cAMP followed by subsequent hydrolysis to 5′AMP, generating the cAMP-free RIα (Fig. 10). This is now poised to reassociate with the free C-subunit in the presence of MgATP. Thus, RegA primes RIα for reassociation with the C-subunit.

Fig. 10.

Proposed mechanism for RegA mediated hydrolysis of cAMP-bound to RIα. A, Structure of cAMP-bound RIα is shown (from PDB ID: 1RGS (30)) highlighting the cAMP binding site and αC:A helix, which are part of the three regions showing decreased exchange upon interactions with the catalytic PDE domain of RegA (red cartoon). Binding of RegA induces release of cAMP, which is consequently hydrolyzed to 5′ AMP. B, RegA binding disrupts conserved electrostatic charge relays anchoring cAMP to RIα at binding site (step 1), which in turn facilitates release of cAMP (step 2) leading to its subsequent hydrolysis. This would enable reassociation of the cAMP-free RIα generated with PKA C-subunit via a separate interaction site (step 3) (41) leading to holoenzyme formation and signal termination.

DISCUSSION

The cAMP-PKA signaling pathway is highly conserved across all eukaryotes from yeast to humans. Although the individual elements of the pathway, namely PKA R and C-subunits and PDEs are conserved, higher eukaryotes show an enormous complexity in isoforms and splice variants for each of the proteins involved in this pathway (6). Sophisticated regulatory networks modulate the activity of the cAMP signaling pathway wherein intracellular levels of cAMP are controlled not only by hormonal stimulation of ACs but also by PDE-mediated hydrolysis of cAMP to 5′ AMP. In order to study interactions between PDEs and PKA we have chosen the elements of a simple eukaryotic model- Dictyostelium discoideum, which presents a simple model for cAMP-PKA signaling with single isoforms of the PKA R (RIα) and C-subunit (Cα) that both show high homology to mammalian PKA subunits (18). Extensive studies have shown that an N-terminal deletion mutant of B. taurus RIα interacts with and activates the D. discoideum PDE, RegA to the same extent as the cognate D. discoideum R-subunit (17). Our results further localize the interactions of RegA to a shorter double truncation mutant lacking the N-terminal domain as well as the CNB-B domain, RIα(91–244), which encompasses the CNB-A domain. All of the residues involved in cAMP binding and allostery are invariant between D. discoideum RIα and mammalian (B. taurus) RIα (Supplemental Fig. 5) (18). Given the strong homology and functional equivalence of mammalian and D. discoideum PKA subunits, we have used the mammalian PKA R and C-subunits and D. discoideum PDE, RegA to examine direct protein interactions between the two groups of proteins. Even though the cAMP signaling proteins used are from separate species, our studies on regulatory interactions have shed light on the mechanism of signal termination that is likely to be conserved across all species. Our evidence of allosteric communication between PKA and PDEs is thus relevant for cAMP signaling in general and cAMP signaling in D. discoideum in particular.

RegA Phosphodiesterase is Capable of Hydrolyzing cAMP-bound to RIα

In the cAMP-dependent activation/termination cycle of PKA, cAMP generated by the activation of adenylyl cyclases binds PKA leading to dissociation of the C and R-subunits. Signal termination is assumed to occur through the reverse process of reassociation of the subunits and release of cAMP. However two aspects of the signaling process remain unclear. How is the cAMP that binds the free R-subunit with high affinity (low nm) released before it can reassociate with the C-subunit? It has been demonstrated in several studies with [3H]-labeled cAMP (46, 47) that the intrinsic dissociation rate of cAMP from the R-subunit is low as measured by dialysis (t ½ > 5 days) (46). When excess unlabeled cAMP is included the dissociation rates are faster but the important question remains that in the absence of excess cAMP, how is the bound cAMP released and signal termination achieved? A related aspect is how PKA is better suited to respond to a flux of cAMP rather than to fixed levels of cAMP (48)? Our present study underscores the role of PDEs in mediating dissociation and hydrolysis of cAMP bound to the R-subunits and is critical for signal termination in cAMP signaling.

The cAMP binding A-domain (CNB:A) of RIα is sufficient for mediating interactions with the catalytic PDE domain of RegA. Interaction of RegA with cAMP-bound RIα catalyzes hydrolysis of cAMP to generate 5′ AMP and cAMP-free RIα: RegA complex as products. Amide H/D exchange mass spectrometry show that RegA interactions with RIα at a surface spanning the PBC. Examination of the structure of the cAMP-binding pocket suggests two possibilities of how RegA might mediate hydrolysis of bound cAMP. It could recognize bound cAMP and hydrolyze it directly or alternatively RegA binding to the R-subunit might induce the active dissociation of cAMP from its high affinity binding site with subsequent hydrolysis to 5′ AMP. Our PDE activity and fluorescence polarization experiments with a PDE-resistant cAMP analog support the latter mechanism (Fig. 10A). In summary we propose a mechanism that highlights a novel role for PDEs in facilitating hydrolysis of cAMP-bound to RIα allowing for reassociation with the C-subunit. The three steps in cAMP signal termination summarized in Fig. 10B are:

Binding to cAMP-bound RIα leading to dissociation of cAMP from RIα,

Activation of PDE catalysis and hydrolysis of the dissociated cAMP generating the cAMP-free RIα-RegA complex

Capture of cAMP-free RIα by the C-subunit leading to reassociation of the R and C-subunits and leading to holoenzyme formation with consequent dissociation of RegA.

These are described in additional detail below

i) Binding to cAMP-bound RIα, which Weakens Interactions between cAMP and RIα

Our studies for the first time highlight an important aspect of signal termination in cAMP signaling, namely to understand how cAMP bound to RIα is released. Till now it was assumed that this occurred solely through competitive binding of the C-subunit, which weakens the affinity of cAMP for the R-subunit (19). Our FP studies with 8-Fluo-cAMP, a fluorescent cAMP analog have been useful in elaborating a role for PDEs in facilitating the dissociation of bound cAMP. Monitoring the dissociation rates of cAMP from RIα under various conditions show that RegA is capable of facilitating a faster dissociation of cAMP from the RIα even in the presence of unlabeled cAMP or the C-subunit (Fig. 8).

ii) Activation of PDE Catalysis and Hydrolysis of the Dissociated cAMP Generating the cAMP-free RIα-RegA Complex

RIα binding results in a 13× fold activation of PDE catalysis through an effect solely on the catalytic rate for the reaction (Fig. 4). This enhanced catalysis is observed with cAMP in solution whereas a significantly lower activity was seen when bound cAMP was used as a sole substrate for RegA (Fig. 8A). A possible explanation for this would be that RegA mediates dissociation of bound cAMP at a slower rate followed by rapid hydrolysis of the released cAMP. We confirmed this by measuring the rates of dissociation of cAMP bound to RIα in the absence and presence of RegA (Fig. 8B, 8C). Our results support a stepwise model whereby RegA binds RIα leading to dissociation first followed by hydrolysis of cAMP to 5′AMP. The rate of PDE activity of the RIα-bound protein (kcat = 43.0 min−1) is greater than the rate of dissociation of cAMP from RIα (cAMP-off rate = 0.5 min−1). RegA binding mediates dissociation of cAMP from PBC of the R-subunit followed by its hydrolysis. RegA thus is capable of hydrolyzing both cAMP, free in solution as well as cAMP-bound to the R- subunit, the latter via a two-step process. This represents the first known instance of a phosphodiesterase actively mediating hydrolysis of cAMP-bound to PKA R-subunits or any other CNB domain-containing protein. It is interesting to note the difference in affinities of cAMP for the CNB domains in RIα compared with that with the guanine exchange factor Epac. The affinity of cAMP to free RIα is in the nanomolar range but is 1000× weaker for the holoenzyme as well as for the CNB domains of Epac. Thus cAMP binds to the PKA R- subunit (KD = 0.2 nm) with ∼10,000× higher affinity than to Epac1 (KD = 2.9 μm) (20). The ability of PDEs to hydrolyze cAMP-bound to RIα through a two-step process might thus be uniquely relevant to it given the higher affinity of cAMP to RIα relative to other CNB domain-containing proteins such as Epac, given the high estimated intracellular concentrations of cAMP (20).

iii) Capture of cAMP-free RIα by the C-subunit Leading to Reassociation of the R and C-subunits and Leading to Holoenzyme Formation with Consequent Dissociation of RegA

Our results show that RegA binding primes cAMP-bound RIα for reassociation with the C-subunit. C-subunit predictably associates weakly with cAMP-bound RIα but preincubation/addition of RegA leads to strong binding to cAMP-free apo RIα. This also indicates that the C-subunit is capable of displacing RegA from the cAMP-free RIα-RegA complex leading to signal termination (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Proposed model for the role of PDEs in signal termination of PKA. cAMP activates PKA by facilitating dissociation of the holoenzyme into cAMP-bound R-subunit and free C-subunit, which then catalyzes the phosphorylation of numerous intracellular substrates. PDEs bind the cAMP-bound R-subunit, induce cAMP dissociation and subsequent hydrolysis of cAMP. The cAMP-free R subunit generated enhances activity of the associated PDE and is primed to reassociate with the C-subunit regenerating the PKA holoenzyme.

Dual Function of RIα as Inhibitor of C-subunit and Activator of PDEs

Our results on the affinities of RegA for both cAMP-bound and cAMP-free forms of RIα being nearly identical are not surprising as cAMP is hydrolyzed during the course of fluorescence experiments, generating cAMP-free RIα-RegA complex. It should be noted that RIα would exist in the cell predominantly in the cAMP-bound or C-subunit-bound states but only transiently in the cAMP-free state given the high affinity of RIα for both cAMP and the C-subunit. We predict that the cAMP-free RIα-RegA complex is thus an important intermediate in the signal termination step of cAMP signaling where free C-subunit competitively reassociates with the cAMP-free RIα to release RegA and generate the inactive holoenzyme (Fig. 11). Furthermore, our results indicate that cAMP-free RIα-RegA activates PDE catalysis. This enables adaptation to steady state levels of cAMP and ensures reactivation of PKA only upon large fluxes of cAMP levels in the cell (48). Significantly, cAMP-bound RIα is a substrate for PDEs and an activator of PDE catalysis in addition to its well-known role as a cAMP-dependent inhibitor of PKA C-subunit.

RIα Mediates Distinct but Overlapping Interactions with PKA C- subunit and RegA-PDE

The crystal structure of cAMP-bound RIα (PDB:1RGS) shows that the highly conserved PBC provides an important hydrophobic environment for cAMP, shielding it from intracellular phosphodiesterases (43, 49). Three regions on RIα showed decreased solvent accessibility upon binding to RegA (Figs. 6A, 6B, Table I). The first region includes the PBC with two sets of fragments spanning residues 205–212 and 199–203 respectively. The first fragment includes Arg 209 and Ala 210, conserved residues critical for anchoring the cyclic phosphate moiety of cAMP (42). The second fragment peptide contains two important residues Glu 200 and Ala 202, which are important for interacting with the 2′ OH of the ribose moiety of cAMP (35). A second region spanning β strands 1–2 showed decreased deuterium exchange. Interestingly, this region contains residues that are involved in mediating an important relay coupling cAMP binding to PKA activation (Figs. 6C, 6D) (32) and Badireddy et al. (manuscript submitted) (50, 51)). A third region showing decreased exchange in the RegA-RIα complex spans α:B and α:C helices, critical for coupling C-subunit and cAMP binding to the PBC as well as integrating signals from cAMP:B domain (40). Any of these regions alone or together might form the RegA-RIα interaction interface because reduced exchange seen upon RegA binding can be because of shielding of solvent as a consequence of direct binding interactions between RIα and RegA or because of binding-induced conformational changes. The differences between direct interactions and induced conformational changes are currently being tested by site-directed mutagenesis in ongoing studies. It is interesting that the three regions we identified on RIα as being important for RegA interactions are equally important either for cAMP binding or for relaying the allosteric effects of cAMP binding to the rest of the protein. Furthermore the solvent protected regions form a contiguous surface distinct from the RIα(91–244):C interface (34, 40) (Fig. 7). None of the other regions including the helical subdomain: αX:N helix, A helix, and the B/C helix in the cAMP binding A domain that form the interaction interface with C- subunit showed any difference in deuterium exchange in the RegA-RIα complex suggesting that the modes of RegA and C-subunit binding to RIα might be different. Whereas the C-subunit interacts with the pseudosubstrate site and helices in the α:subdomain, RegA mainly interacts with β:subdomain, with residues involved in binding cAMP and enabling allosteric effects of cAMP binding across the entire molecule.

Universal Mode of Regulatory Crosstalk between PKA R-subunits and PDEs

Amide H/D exchange MS data has provided insights into the regions of RIα important for interactions with RegA. These include PBC, β-subdomain region (β1-β2) and α:B-C-helices, all nearly invariant across R-subunits from all species with a very high degree of conservation (1, 18). Given that the PDE catalytic domains across species are highly conserved (6), we strongly believe that these interactions are also likely to be conserved among mammalian PDEs as well (Supplemental Fig. 5). We are examining the closest mammalian homologs of RegA for their ability to bind RIα.

Till now details of how cAMP-bound to the R-subunit is released and hydrolyzed to 5′AMP, has been attributed to a combination of effects mediated by the C-subunit and PDEs. In this mechanism, C-subunit binding competitively dissociates cAMP, which then is hydrolyzed by PDEs to 5′AMP, leading to signal termination (19). We describe for the first time an alternate mechanism where RIα activates PDE catalysis severalfold, leading to hydrolysis of bound cAMP. These studies highlight a universal model for cross-talk between R-subunits and PDE catalytic domains, which plays important roles in signal termination of second messenger cAMP signaling (Fig. 11).

Acknowledgments

We thank Mark Ritchie, Waters Pacific Private Ltd. Singapore and Michael Eggertson, Martha Stapels and Keith Fadgen, Waters Corporation, Milford, MA. We also thank Suguna Badireddy, Tanushree Bishnoi, Srinath Krishnamurthy and Dr. Kenneth M. Humphries (Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation) for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

* This work was supported by a grant from A*STAR-Biomedical Research Council, Singapore and a Beta-test agreement and grant from Waters Corporation, Milford MA.

This article contains supplemental Figs.1–5.

This article contains supplemental Figs.1–5.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- cAMP

- cyclic adenosine 3′, 5′- monophosphate

- AKAP

- A- kinase anchoring protein

- AC

- adenylyl cyclase

- BME

- β- mercaptoethanol

- C subunit

- catalytic subunit of PKA

- CIAP

- calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase

- FM

- fluorescein maleimide

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- FP

- fluorescence polarization

- LC-ESI QTOF

- liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization quadrupole time-of-flight

- MALDI-TOF

- matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight

- NHS

- N-hydroxysuccinimide

- PDE

- cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase

- PKA

- protein kinase A

- R-subunit

- regulatory subunit of PKA

- PBC

- phosphate binding cassette.

REFERENCES

- 1. Berman H. M., Ten Eyck L. F., Goodsell D. S., Haste N. M., Kornev A., Taylor S. S. (2005) The cAMP binding domain: an ancient signaling module. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 45–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beebe S. J., Corbin J. D. (1986) Cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinases. The Enzymes 17, 43–111 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johnson D. A., Akamine P., Radzio-Andzelm E., Madhusudan M., Taylor S. S. (2001) Dynamics of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Chem. Rev. 101, 2243–2270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shabb J. B. (2001) Physiological substrates of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Chem. Rev. 101, 2381–2411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kamenetsky M., Middelhaufe S., Bank E. M., Levin L. R., Buck J., Steegborn C. (2006) Molecular details of cAMP generation in mammalian cells: a tale of two systems. J. Mol. Biol. 362, 623–639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Conti M., Beavo J. (2007) Biochemistry and physiology of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: essential components in cyclic nucleotide signaling. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 481–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McKnight G. S. (1991) Cyclic AMP second messenger systems. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 3, 213–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Amieux P. S., Cummings D. E., Motamed K., Brandon E. P., Wailes L. A., Le K., Idzerda R. L., McKnight G. S. (1997) Compensatory regulation of RIalpha protein levels in protein kinase A mutant mice. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 3993–3998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Amieux P. S., McKnight G. S. (2002) The essential role of RI alpha in the maintenance of regulated PKA activity. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 968, 75–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wong W., Scott J. D. (2004) AKAP signalling complexes: focal points in space and time. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 959–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baillie G. S., Scott J. D., Houslay M. D. (2005) Compartmentalisation of phosphodiesterases and protein kinase A: opposites attract. FEBS Lett. 579, 3264–3270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dodge K. L., Khouangsathiene S., Kapiloff M. S., Mouton R., Hill E. V., Houslay M. D., Langeberg L. K., Scott J. D. (2001) mAKAP assembles a protein kinase A/PDE4 phosphodiesterase cAMP signaling module. EMBO J. 20, 1921–1930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gold M. G., Lygren B., Dokurno P., Hoshi N., McConnachie G., Taskén K., Carlson C. R., Scott J. D., Barford D. (2006) Molecular basis of AKAP specificity for PKA regulatory subunits. Mol. Cell 24, 383–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Burns L. L., Canaves J. M., Pennypacker J. K., Blumenthal D. K., Taylor S. S. (2003) Isoform specific differences in binding of a dual-specificity A-kinase anchoring protein to type I and type II regulatory subunits of PKA. Biochemistry 42, 5754–5763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huang L. J., Wang L., Ma Y., Durick K., Perkins G., Deerinck T. J., Ellisman M. H., Taylor S. S. (1999) NH2-Terminal targeting motifs direct dual specificity A-kinase-anchoring protein 1 (D-AKAP1) to either mitochondria or endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Biol. 145, 951–959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Han P., Sonati P., Rubin C., Michaeli T. (2006) PDE7A1, a cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase, inhibits cAMP-dependent protein kinase by a direct interaction with C. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 15050–15057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shaulsky G., Fuller D., Loomis W. F. (1998) A cAMP-phosphodiesterase controls PKA-dependent differentiation. Development 125, 691–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Canaves J. M., Taylor S. S. (2002) Classification and phylogenetic analysis of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase regulatory subunit family. J. Mol. Evol. 54, 17–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ogreid D., Døskeland S. O. (1983) Cyclic nucleotides modulate the release of [3H] adenosine cyclic 3′,5′-phosphate bound to the regulatory moiety of protein kinase I by the catalytic subunit of the kinase. Biochemistry 22, 1686–1696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dao K. K., Teigen K., Kopperud R., Hodneland E., Schwede F., Christensen A. E., Martinez A., Døskeland S. O. (2006) Epac1 and cAMP-dependent protein kinase holoenzyme have similar cAMP affinity, but their cAMP domains have distinct structural features and cyclic nucleotide recognition. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 21500–21511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Diller T. C., Xuong N. H., Taylor S. S. (2000) Type II beta regulatory subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase: purification strategies to optimize crystallization. Protein Expr. Purif. 20, 357–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Anand G., Taylor S. S., Johnson D. A. (2007) Cyclic-AMP and Pseudosubstrate Effects on Type-I A-Kinase Regulatory and Catalytic Subunit Binding Kinetics. Biochemistry 46, 9283–9291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Herberg F. W., Bell S. M., Taylor S. S. (1993) Expression of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase in Escherichia coli: multiple isozymes reflect different phosphorylation states. Protein Eng. 6, 771–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goodrich J. A. a. K., J. F (2007) Binding and kinetics for molecular biologists, 1st Ed., Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kool J., van Marle A., Hulscher S., Selman M., van Iperen D. J., van Altena K., Gillard M., Bakker R. A., Irth H., Leurs R., Vermeulen N. P. (2007) A flow-through fluorescence polarization detection system for measuring GPCR-mediated modulation of cAMP production. J. Biomol. Screen 12, 1074–1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wales T. E., Fadgen K. E., Gerhardt G. C., Engen J. R. (2008) High-speed and high-resolution UPLC separation at zero degrees Celsius. Anal. Chem. 80, 6815–6820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bateman R. H., Carruthers R., Hoyes J. B., Jones C., Langridge J. I., Millar A., Vissers J. P. (2002) A novel precursor ion discovery method on a hybrid quadrupole orthogonal acceleration time-of-flight (Q-TOF) mass spectrometer for studying protein phosphorylation. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 13, 792–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Silva J. C., Denny R., Dorschel C. A., Gorenstein M., Kass I. J., Li G. Z., McKenna T., Nold M. J., Richardson K., Young P., Geromanos S. (2005) Quantitative proteomic analysis by accurate mass retention time pairs. Anal. Chem. 77, 2187–2200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Geromanos S. J., Vissers J. P., Silva J. C., Dorschel C. A., Li G. Z., Gorenstein M. V., Bateman R. H., Langridge J. I. (2009) The detection, correlation, and comparison of peptide precursor and product ions from data independent LC-MS with data dependant LC-MS/MS. Proteomics 9, 1683–1695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li G. Z., Vissers J. P., Silva J. C., Golick D., Gorenstein M. V., Geromanos S. J. (2009) Database searching and accounting of multiplexed precursor and product ion spectra from the data independent analysis of simple and complex peptide mixtures. Proteomics 9, 1696–1719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Weis D. D., Engen J. R., Kass I. J. (2006) Semi-automated data processing of hydrogen exchange mass spectra using HX-Express. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 17, 1700–1703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Anand G. S., Krishnamurthy S., Bishnoi T., Kornev A., Taylor S. S., Johnson D. A. (2010) Cyclic-AMP and Rp-cAMPS induced conformational changes in a complex of the catalytic and regulatory (RIa) subunits of PKA. Mol. Cell Proteomics oi: 10.1074/mcp.M900388-MCP200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mandell J. G., Falick A. M., Komives E. A. (1998) Identification of protein-protein interfaces by decreased amide proton solvent accessibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 14705–14710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim C., Xuong N. H., Taylor S. S. (2005) Crystal structure of a complex between the catalytic and regulatory (RIalpha) subunits of PKA. Science 307, 690–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Su Y., Dostmann W. R., Herberg F. W., Durick K., Xuong N. H., Ten Eyck L., Taylor S. S., Varughese K. I. (1995) Regulatory subunit of protein kinase A: structure of deletion mutant with cAMP binding domains. Science 269, 807–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stock A. M., Robinson V. L., Goudreau P. N. (2000) Two-component signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69, 183–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thomason P. A., Traynor D., Cavet G., Chang W. T., Harwood A. J., Kay R. R. (1998) An intersection of the cAMP/PKA and two-component signal transduction systems in Dictyostelium. EMBO J. 17, 2838–2845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hoofnagle A. N., Resing K. A., Ahn N. G. (2003) Protein analysis by hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 32, 1–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mandell J. G., Baerga-Ortiz A., Akashi S., Takio K., Komives E. A. (2001) Solvent accessibility of the thrombin-thrombomodulin interface. J. Mol. Biol. 306, 575–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Anand G. S., Hughes C. A., Jones J. M., Taylor S. S., Komives E. A. (2002) Amide H/2H exchange reveals communication between the cAMP and catalytic subunit-binding sites in the R(I)alpha subunit of protein kinase A. J. Mol. Biol. 323, 377–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hughes C. A., Mandell J. G., Anand G. S., Stock A. M., Komives E. A. (2001) Phosphorylation causes subtle changes in solvent accessibility at the interdomain interface of methylesterase CheB. J. Mol. Biol. 307, 967–976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cànaves J. M., Leon D. A., Taylor S. S. (2000) Consequences of cAMP-binding site mutations on the structural stability of the type I regulatory subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Biochemistry 39, 15022–15031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]