Abstract

To persist in latently infected, proliferating cells, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) episomes must replicate and efficiently segregate to progeny nuclei. Episome persistence in uninfected cells requires latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 (LANA1) in trans and cis-acting KSHV terminal repeat (TR) DNA. The LANA1 C terminus binds TR DNA, and LANA1 mediates TR-associated DNA replication in transient assays. LANA1 also concentrates at sites of KSHV TR DNA episomes along mitotic chromosomes, consistent with a tethering role to efficiently segregate episomes to progeny nuclei. LANA1 amino acids 5 to 22 constitute a chromosome association region (Piolot et al., J. Virol. 75:3948-3959, 2001). We now investigate LANA1 residues 5 to 22 with scanning alanine substitutions. Mutations targeting LANA1 5GMR7, 8LRS10, and 11GRS13 eliminated chromosome association, DNA replication, and episome persistence. LANA1 mutated at 14TG15 retained the ability to associate with chromosomes but was partially deficient in DNA replication and episome persistence. These results provide genetic support for a key role of the LANA1 N terminus in chromosome association, LANA1-mediated DNA replication, and episome persistence.

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV, also called human herpesvirus 8), a gamma-2-herpesvirus, is tightly associated with Kaposi's sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma, and multicentric Castleman's disease (4, 5, 29, 38). KSHV infection in tumor cells and in primary effusion lymphoma cell lines is predominantly latent. Latently infected cells have multiple copies of extrachromosomal circular KSHV DNA (episomes) (4, 9). To persist in proliferating cells, episomes must replicate prior to each cell division and then efficiently segregate to progeny cells. Latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 (LANA1) (22, 23, 32), one of a limited number of viral genes expressed in latent infection, is necessary and sufficient for KSHV episome persistence (1, 2). Expression of LANA1 in uninfected B lymphoblastoid cells permits episome persistence of DNA containing the KSHV terminal repeat (TR) sequence (1, 2).

Consistent with its role in episome persistence, LANA1 specifically binds KSHV TR DNA and mediates its replication (2, 7, 8, 11, 12, 15, 17, 27, 34). The LANA1 C terminus cooperatively binds two adjacent sites within the KSHV TR (12). In transient assays, LANA1 expression enables TR DNA to replicate (12, 15, 17, 27). The LANA1 C-terminal DNA binding domain is essential for DNA replication. The LANA1 N terminus also has a role in DNA replication, since fusion of at least the N-terminal 90 amino acids to the C terminus was either essential for (15, 26, 27) or enhanced (17) replication.

LANA1 also associates with mitotic chromosomes (1, 24, 31, 40). Immunofluorescence microscopy demonstrates that LANA1 concentrates at sites of KSHV DNA along mitotic chromosomes (1, 7, 20, 39). In the absence of episomes, LANA1 diffusely paints chromosomes (1). LANA1 contains two independent chromosome association regions, one comprised of amino acids 5 to 22 (31) and a second within the C-terminal domain (24; M. Ballestas, T. Komatsu, and K. Kaye, 4th Int. Workshop KSHV Related Agents, 2001).

Taken together, these findings are consistent with LANA1 enabling episome persistence by mediating KSHV DNA replication and bridging DNA to mitotic chromosomes to efficiently segregate episomes to progeny nuclei. Such a function is similar to that proposed for the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) EBNA1 and bovine papillomavirus E2 proteins. EBNA1 and E2 both bind cognate DNA, are involved in its replication, and are hypothesized to tether DNA to chromosomes to efficiently segregate episomes to progeny cells (3, 18, 19, 25, 37, 42, 43).

This work investigated the LANA1 N terminus. We demonstrate that LANA1 amino acids 5 through 13 are essential for chromosome targeting, DNA replication, and episome persistence. In addition, residues 14 and 15, which are not required for chromosome association, contribute to DNA replication and episome persistence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

GFP NLS (18) has the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene fused to a nuclear localization signal (NLS). GFP LANA1 1-32 contains the indicated LANA1 residues downstream of GFP in EGFP-Cl (Clontech). GFP LANA1 was constructed by inserting a SmaI restriction fragment from pBSLANA (1) into the SmaI site of EGFP-C1. Alanine substitutions in GFP LANA1 1-32 were introduced by PCR mutagenesis with the oligonucleotides listed in Table 1. GFP LANA1 1-32 was amplified with the reverse (R) primer of each pair and oligonucleotide GFP-F, and GFP LANA1 1-32 was also amplified with the forward (F) primer of each pair and GFP-R.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used to generate LANA1 mutants

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| GFP-F | CTCGCCGACCACTACCAGCAG |

| GFP-R | GCTTACTATTTACGCGTTAAG |

| LANA1 5GMR7→AAA-F | GGCGCCCCCGGCGGCCGCGCTGAGGTCGGGACGG |

| LANA1 5GMR7→AAA-R | CCGTCCCGACCTCAGCGCGGCCGCCGGGGGCGCC |

| LANA1 8LRS10→AAA-F | GGGAATGCGCGCGGCCGCGGGACGGAGCACCGGCG |

| LANA1 8LRS10→AAA-R | CGCCGGTGCTCCGTCCCGCGGCCGCGCGCATTCCC |

| LANA1 11GRS13→AAA-F | CCTGAGGTCGGCGGCCGCGACCGGCGCGCGCCC |

| LANA1 11GRS13→AAA-R | GGGCGCGCGCCGGTCGCGGCCGCCGACCTCAGG |

| LANA1 14TG15→AA-F | GGGACGGAGCGCGGCCGCGCCCTTAACGAGAGGAAG |

| LANA1 14TG15→AA-R | CTTCCTCTCGTTAAGGGCGCGGCCGCGCTCCGTCCC |

| LANA1 17PLT19→AAA-F | CACCGGCGCGGCGGCGGCGAGAGGAAGTTG |

| LANA1 17PLT19→AAA-R | CAACTTCCTCTCGCCGCCGCCGCGCCGGTG |

| LANA1 20RGS22→AAA-F | GCCCTTAACGGCGGCCGCGTGTAGGAAACGAAACAG |

| LANA1 20RGS22→AAA-R | CTGTTTCGTTTCCTACACGCGGCCGCCGTTAAGGGC |

| LANA1 5-13-F | GGAATGCGCCTGAGGTCGGGACGGAGCTGCA |

| LANA1 5-13-R | TGCAGCTCCGTCCCGACCTCAGGCGCATTCC |

| LANA1 5-14-F | GGAATGCGCCTGAGGTCGGGACGGAGCACCTGCA |

| LANA1 5-14-R | TGCAGGTGCTCCGTCCCGACCTCAGGCGCATTCC |

For each mutation, the products of these reactions were combined, amplified with GFP-F and GFP-R, and inserted into the EcoRI and BglII restriction sites of EGFP-Cl. Mutations were subcloned from GFP LANA1 1-32 to GFP LANA1 with BsaI. Mutations were cloned from GFP LANA1 to pSG5LANA (1) with EcoRI and NruI. To generate GFP LANA1 5-13 and GFP LANA1 5-14, complementary oligonucleotides (Table 1) were annealed and inserted into PstI-digested GFP NLS. To generate p8TR, Z6-BE (2) was digested with BstYI and the ≈8.4-kb fragment (containing a partial TR, eight copies of the TR unit, and ≈1.3 kb of unique KSHV sequence) was cloned into the BamHI site of the pRepCK vector (1). All PCR-generated clones were confirmed by sequencing.

Transfections and fluorescence microscopy.

BJAB cells were transfected in 400 μl of RPMI medium at 200 V and 960 μF in a 0.4-cm-gap cuvette with a Bio-Rad electroporator (1). For metaphase spreads, 0.5 × 106 cells/ml were incubated overnight in 1 μg of colcemid (Calbiochem) per ml 18 to 24 h after transfection. Colcemid-treated cells were swollen in hypotonic buffer (1% sodium citrate, 10 mM CaCl2, 10 mM MgCl2), spread onto slides, and fixed for 10 min in 4% paraformaldehyde (Polysciences) in phosphate-buffered saline. For Fig. 3, cell spreads were fixed in methanol-acetone (1:1) and incubated with anti-LANA1 monoclonal antibody (ABI) followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-rat immunoglobulin G (Southern Biotechnology). Cells were counterstained with propidium iodide (Molecular Probes) (1 μg/ml), and coverslips were applied with Aqua-Poly mount (Polysciences). Microscopy was performed with a Zeiss Axioskop, PCM2000 hardware, and C-imaging software (Compix, Inc.).

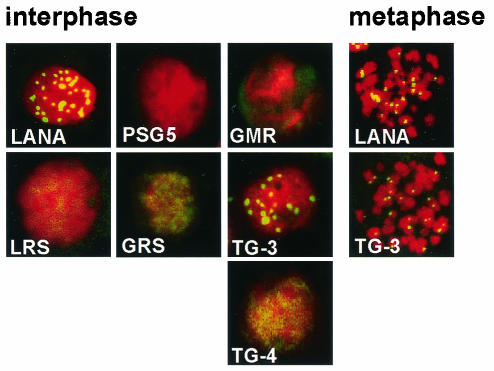

FIG. 3.

Confocal microscopy of G418-resistant BJAB cells expressing LANA1 mutants. LANA1 (green) was detected with anti-LANA1 monoclonal antibody, and interphase nuclei (red) (left) and metaphase chromosomes (red) (right) were detected with propidium iodide. Overlay of green and red generates yellow. BJAB cells with only pSG5 do not express LANA1. BJAB cells expressing F-LANA1 (LANA), LANA1 5GMR7→ AAA (GMR), LANA1 8LRS10→ AAA (LRS), LANA1 11GRS13→ AAA (GRS), and LANA1 14TG15→ AA-3 (TG-3) and -4 (TG-4) are shown. Magnification, ×630.

Generation of BJAB cells stably expressing LANA1 proteins.

pSG5 plasmids (Stratagene) encoding LANA1 mutants were cotransfected with a plasmid carrying the hygromycin resistance gene downstream of a simian virus 40 promoter into BJAB cells. After 48 h, cells were seeded into microtiter plates, selected for hygromycin resistance, and screened for LANA1 expression (1).

DNA replication assay and electrophoretic mobility shift assays.

Forty-eight hours after transfection with 30 μg of p8TR DNA, low-molecular-weight DNA was harvested from cells by the method of Hirt (16), and 3 μg of DNA was overdigested overnight with 50 U of BglII, and 30 μg of DNA was overdigested overnight with 50 U of BglII and 100 U of DpnI. Digested DNA was resolved in a 0.7% agarose gel and Southern blotting was performed with a 32P-labeled TR probe. For electrophoretic mobility shift assays, in vitro-translated LANA1 proteins (TNT Quick-coupled reticulocyte lysate systems [Promega]) were incubated in 22 μl of reaction buffer [20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 10% glycerol, 50 mM KCl, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 18 μg of poly(dI-dC) per ml] with 50,000 cpm of TR-13 probe for 30 min at room temperature with or without excess unlabeled TR-13. TR-13 is a 20-nucleotide LANA1 binding sequence (2). Complexes were resolved by electrophoresis in 3.5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels, and signal was detected by autoradiography.

Selection of G418-resistant cells and Gardella gel analysis.

BJAB cells stably expressing Flag epitope-tagged LANA1 (F-LANA1) (1) or LANA1 mutants were transfected with p8TR DNA. After 48 h, cells were seeded (1,000 cells/well) into 96-well microtiter plates in medium containing G418 (600 μg/ml) (Gibco). Gardella gel analysis was performed by in situ lysis of cells in gel-loading wells with pronase and sodium dodecyl sulfate and electrophoresis in Tris-borate-EDTA (14). DNA was transferred to a nylon membrane, and KSHV DNA was detected with a 32P-labeled TR probe.

RESULTS

LANA1 residues 5 to 13 are essential for chromosome targeting.

To determine which residues within LANA1 amino acids 5 to 22 mediate chromosome association, green fluorescent protein (GFP) was fused to LANA1 1-32 containing scanning alanine substitutions. GFP LANA1 1-32 5GMR7→ AAA, GFP LANA1 1-32 8LRS10→ AAA, GFP LANA1 1-32 11GRS13→ AAA, GFP LANA1 1-32 14TG15→ AA, GFP LANA1 1-32 17PLT19→ AAA, and GFP LANA1 1-32 20RGS22→ AAA each contain the indicated amino acids mutated to alanines within GFP LANA 1-32 (Fig. 1). LANA1 residue 16 (alanine) was left unchanged. LANA1 residues 24 to 30 encode a nuclear localization signal (NLS) and were left intact to target the GFP fusion proteins to the nucleus.

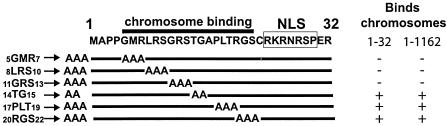

FIG. 1.

Alanine scanning mutagenesis of the LANA1 N terminus. LANA1 residues 1 to 32 are shown with the indicated alanine substitutions below. The NLS and previously defined chromosome association region are indicated (31). The chromosome binding abilities of GFP LANA1 1-32 and GFP LANA1 1-1162 containing each indicated mutation are summarized at the right.

The GFP fusion proteins containing alanine substitutions were assayed for the ability to associate with mitotic chromosomes. GFP LANA1 1-32, GFP LANA1 1-32 5GMR7→ AAA, GFP LANA1 1-32 8LRS10→ AAA, GFP LANA1 1-32 11GRS13→ AAA, GFP LANA1 1-32 14TG15→ AA, GFP LANA1 1-32 17PLT19→ AAA, GFP LANA1 1-32 20RGS22→ AAA, and GFP NLS were each expressed in (uninfected) BJAB B lymphoma cells. GFP NLS has GFP fused with an NLS to target GFP to the nucleus. After 24 h, cells were metaphase arrested with colcemid and investigated by confocal microscopy.

GFP LANA1 1-32 5GMR7→ AAA (Fig. 2A, green), GFP LANA1 1-32 8LRS10→ AAA (Fig. 2A, green), and GFP LANA1 1-32 11GRS13→ AAA (Fig. 2A, green) did not paint chromosomes (red) and instead distributed between them, similar to GFP NLS (Fig. 2A). In contrast, GFP LANA1 1-32 14TG15→ AA (Fig. 2A, green), GFP LANA1 1-32 17PLT19→ AAA (Fig. 2A, green), and GFP LANA1 1-32 20RGS22→ AAA (Fig. 2A, green) diffusely painted mitotic chromosomes (red) (overlay of green and red generates yellow) similar to GFP LANA1 1-32 (Fig. 2A). A small amount of GFP LANA1 1-32 14TG15→ AA was also interspersed between chromosomes (Fig. 2A, arrows), and may be due to a slightly lower affinity for chromosomes compared to GFP LANA1 1-32 17PLT19→ AAA, GFP LANA1 1-32 20RGS22→ AAA and GFP LANA1 1-32. Cells were also investigated by fluorescence microscopy in live cell drops with Hoechst dye to detect chromosomes and results were similar to those with the fixed cells (data not shown). In live cells, GFP LANA1 1-32 5GMR7→ AAA, GFP LANA1 1-32 8LRS10→ AAA, and GFP LANA1 1-32 11GRS13→ AAA did not associate with chromosomes and GFP LANA1 1-32 14TG15→ AA, GFP LANA1 1-32 17PLT19→ AAA and GFP LANA1 1-32 20RGS22→ AAA diffusely painted chromosomes. Therefore, alanine substitutions of LANA1 5GMR7, 8LRS10, and 11GRS13 abolished GFP LANA1 1-32 chromosome association, but alanine substitutions of LANA1 14TG15, 17PLT19, and 20RGS22 did not.

FIG. 2.

LANA1 amino acids 5 to 13 are essential and sufficient for chromosome targeting. GFP fusion proteins were expressed in BJAB cells and confocal microscopy was performed after metaphase arrest and counterstaining with propidium iodide. Overlay of GFP (green) and chromosomes (red) generates yellow. (A) GFP NLS (GFP), GFP LANA1 1-32 (1-32), GFP LANA1 1-32 5GMR7→ AAA (GMR), GFP LANA1 1-32 8LRS10→ AAA (LRS), GFP LANA1 1-32 11GRS13→ AAA (GRS), GFP LANA1 1-32 14TG15→ AA (TG), GFP LANA1 1-32 17PLT19→ AAA (PLT), and GFP LANA1 1-32 20RGS22→ AAA (RGS). (B) GFP NLS (GFP), GFP LANA1 (LANA), GFP LANA1 5GMR7→ AAA (GMR), GFP LANA1 8LRS10→ AAA (LRS), GFP LANA1 11GRS13→ AAA (GRS), GFP LANA1 14TG15→ AA (TG), GFP LANA1 17PLT19→ AAA (PLT), and GFP LANA1 20RGS22 → AAA (RGS). (C) GFP NLS (GFP), GFP LANA1 1-32 (1-32), GFP LANA1 5-13 (5-13), and GFP LANA1 5-14 (5-14). Arrows indicate small amounts of GFP LANA1 fusions dispersed between chromosomes for GFP LANA1 1-32 14TG15→ AA, GFP LANA1 14TG15→ AA, GFP LANA1 5-13, and GFP LANA1 5-14. Nontransfected cells are red only. Magnification, ×630.

Since LANA1 contains a C-terminal chromosome association region in addition to the one in the N terminus, the effects of these N-terminal mutations were also assayed in full-length LANA1 fused with GFP (GFP LANA1). After expression in BJAB cells and metaphase arrest, GFP LANA1 5GMR7→ AAA, GFP LANA1 8LRS10→ AAA, and GFP LANA1 11GRS13→ AAA did not associate with chromosomes, but GFP LANA1 14TG15→ AA, GFP LANA1 17PLT19→ AAA and GFP LANA1 20RGS22 → AAA coated chromosomes (Fig. 2B). As expected, GFP LANA1, but not GFP NLS, associated with chromosomes (Fig. 2B). A small amount of GFP LANA1 14TG15→ AA distributed between chromosomes (Fig. 2B, arrows), similar to GFP LANA1 1-32 14TG15→ AA. In live cell drops, GFP LANA1 5GMR7→ AAA, GFP LANA1 8LRS10→ AAA, and GFP LANA1 11GRS13→ AAA did not associate with chromosomes, but GFP LANA1 14TG15→ AA, GFP LANA1 17PLT19→ AAA and GFP LANA1 20RGS22→ AAA did associate with chromosomes (data not shown). Therefore, despite the presence of the C-terminal chromosome association domain, 5GMR7→ AAA, 8LRS10→ AAA, and 11GRS13→ AAA each abolish LANA1 chromosome association but 14TG15→ AA, 17PLT19→ AAA and 20RGS22 → AAA do not.

Since LANA1 residues 5 to 13 were essential for chromosome association, we assayed whether they were sufficient to target chromosomes. GFP NLS fused to LANA1 residues 5 to 13 (GFP LANA1 5-13) and GFP NLS fused to LANA1 residues 5 to 14 (GFP LANA1 5-14) were expressed in BJAB cells, and metaphase spreads were prepared. Both GFP LANA1 5-13 and GFP LANA1 5-14 diffusely painted chromosomes, similar to GFP LANA1 1-32 (Fig. 2C). A small amount of GFP LANA1 5-13 and 5-14 also distributed between chromosomes (Fig. 2C, arrows). GFP LANA1 5-13 and GFP LANA1 5-14 also diffusely associated with chromosomes in live cell drops (data not shown). Therefore, LANA1 residues 5 to 13 are sufficient for efficient chromosome targeting.

LANA1 residues 5 to 13 are essential for episome persistence.

To investigate the importance of chromosome association in episome maintenance, LANA1 mutants abolished for chromosome association were assayed for the ability to mediate episome persistence. If chromosome association is critical for LANA1-mediated segregation of episomes to progeny nuclei, then the absence of chromosome association is expected to result in rapid loss of episomes from proliferating cells (18). BJAB cells containing pSG5 vector or stably expressing F-LANA1 (1), LANA1 5GMR7→ AAA, LANA1 8LRS10→ AAA, and LANA1 11GRS13→ AAA were each transfected with p8TR DNA, seeded into microtiter plates, and selected for G418 resistance. p8TR contains eight copies of the KSHV TR element and confers resistance to G418. As expected, p8TR DNA efficiently persisted in F-LANA1-expressing cells, and over 95% of microtiter wells were positive for G418-resistant outgrowth. In contrast, fewer than 30% of microtiter wells were positive for G418-resistant outgrowth in BJAB cells with pSG5 or expressing LANA1 5GMR7→ AAA, LANA1 8LRS10→ AAA, or LANA1 11GRS13→ AAA. The low rate of G418-resistant outgrowth in these cells was reminiscent of results in which TR DNA required integration into host chromosomes for persistence.

The distributions of F-LANA1 and the LANA1 mutants were investigated in the G418-resistant BJAB cells. F-LANA1 (Fig. 3, green) localized to dots within the cell nucleus (red) (overlay of green and red generates yellow). In contrast, LANA1 5GMR7→ AAA (Fig. 3, green), LANA1 8LRS10→ AAA (Fig. 3, green), and LANA1 11GRS13→ AAA (Fig. 3, green) distributed throughout the nucleus (red) (overlay of green and red generates yellow). Since LANA1 focally concentrates to dots at sites of KSHV episomes, but in the absence of episomes distributes throughout the nucleus (1), these results were consistent with episomes in F-LANA1-expressing cells but not in cells expressing LANA1 5GMR7→ AAA, LANA1 8LRS10→ AAA, and LANA1 11GRS13→ AAA.

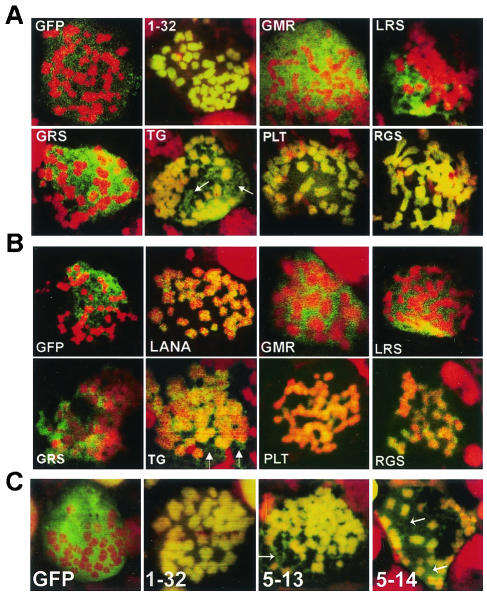

Gardella gel analysis was performed after 26 days of G418 selection to assay for the presence of episomes. In Gardella gels, live cells are loaded into the wells and lysed in situ (14). During electrophoresis, chromosomal DNA remains at the gel origin, while extrachromosomal DNA (as large as 200 kb) migrates into the gel. As expected, KSHV-infected BCBL-1 primary effusion lymphoma cells (33) had episomes (Fig. 4A, lane 1, E) and also linear replicating KSHV (Fig. 4A, lane 1, L). F-LANA1-expressing cells (Fig. 4A, lanes 5 to 7) also had extrachromosomal DNA (asterisk) which migrated near covalently closed circular plasmid p8TR DNA (Fig. 4A, lane 21, ccc). More slowly migrating extrachromosomal DNA was also present in F-LANA1 cells (Fig. 4A, lanes 5 to 7). The more slowly migrating DNA is due to larger episomes generated by TR duplication and arrangement of input plasmids into multimers (2). In contrast, G418-resistant cells with pSG5 (Fig. 4A, lanes 2 to 4), LANA1 5GMR7→ AAA (Fig. 4A, lanes 8 to 10), LANA1 8LRS10→ AAA (Fig. 4A, lanes 11 to 13), and LANA1 11GRS13→ AAA (Fig. 4A, lanes 14 to 16) lacked extrachromosomal DNA. In these cells, G418 resistance was conferred by integrated p8TR DNA. Therefore, LANA1 5GMR7→ AAA, LANA1 8LRS10→ AAA, and LANA1 11GRS13→ AAA did not support persistence of p8TR episomes.

FIG. 4.

LANA1 residues 5 to 13 are essential for episome persistence. Gardella gel analysis was performed to assay for episomes; 2.5 × 106 cells were lysed in situ in gel wells, DNA was resolved by electrophoresis and detected by Southern blotting with the TR probe. (A) After 26 days of G418 selection, independent BJAB cell lines expressing F-LANA1 and LANA1 mutants were assayed for TR episomes. Lane 1, BCBL-1 primary effusion lymphoma cells; lanes 2 to 4, BJAB cells containing pSG5; lanes 5 to 7, BJAB cells expressing F-LANA1; lanes 8 to 10, BJAB cells expressing LANA1 5GMR7→ AAA; lanes 11 to 13, BJAB cells expressing LANA1 8LRS10→ AAA; lanes 14 to 16, BJAB cells expressing LANA1 11GRS13→ AAA; lanes 17 to 20, BJAB cells expressing LANA1 14TG15→ AA; lane 21, p8TR plasmid DNA. E, BCBL-1 KSHV episomes (lane 1), L, linear, replicating BCBL-1 KSHV (lane 1). The asterisk indicates episomes in F-LANA1-expressing cells (lanes 5 to 7). More slowly migrating episomal DNA is also present in lanes 5 to 7. Brackets indicate episomal DNA in LANA1 14TG15→ AA-expressing cells (lanes 17 and 19). (B) After 53 days of G418 selection, BJAB cell lines expressing F-LANA1 and LANA1 14TG15→ AA were again assayed for TR episomes. Lanes 1 to 3, BJAB cells expressing F-LANA1; lanes 4 to 7, BJAB expressing LANA1 14TG15→ AA; lane 8, p8TR plasmid. Nicked and covalently closed circular (ccc) p8TR plasmid is indicated. O, gel origin. This figure is representative of four experiments.

LANA1 14TG15→ AA is partially deficient for episome persistence.

LANA1 14TG15→ AA, which retains the ability to associate with chromosomes, was also investigated for the ability to mediate episome persistence. After transfection into BJAB cells stably expressing LANA1 14TG15→ AA, p8TR DNA efficiently persisted and over 95% of microtiter wells were positive for G418-resistant outgrowth. However, outgrowth was less robust compared to that of p8TR transfected BJAB cells expressing F-LANA1. After one week of G418 selection, colonies of several hundred F-LANA1-expressing cells were present in microtiter wells compared to colonies of fewer than 100 LANA1 14TG15→ AA-expressing cells.

Independently derived, G418-resistant, LANA1 14TG15→ AA-expressing cell lines LANA1 14TG15→ AA-1, -2, -3, and -4 were expanded and investigated by confocal microscopy. LANA1 14TG15→ AA (green) concentrated to dots in interphase nuclei (red) (overlay of green and red generates yellow) and along mitotic chromosomes (red) in LANA1 14TG15→ AA-1 and -3 (Fig. 3) cells. In contrast, LANA1 14TG15→ AA distributed throughout nuclei in almost all LANA1 14TG15→ AA-2 and -4 (Fig. 3) cells. These results were consistent with episome persistence in LANA1 14TG15→ AA-1 and -3, but little or no episome persistence in LANA1 14TG15→ AA-2 and -4 cells.

Gardella gel analysis assayed for the presence of episomes in LANA1 14TG15→ AA cells. LANA1 14TG15→ AA-1 (Fig. 4, lane 17, brackets) and LANA1 14TG15→ AA-3 (Fig. 4A, lane 19, brackets) cells had extrachromosomal DNA, but LANA1 14TG15→ AA-2 (Fig. 4A, lane 18) and LANA1 14TG15→ AA-4 (Fig. 4A, lane 20) did not have detectable episomal DNA. Although LANA1 14TG15→ AA-1 and -3 had episomal DNA, the signal was significantly less intense than that in F-LANA1-expressing cells (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 17 and 19 with lanes 5 to 7), indicating less episomal DNA. Much of the LANA114TG15→ AA-1 and -3 episomal DNA migrated much more slowly (upper brackets in Fig. 4A, lanes 17, 19) than covalently closed circular p8TR DNA (Fig. 4A, lane 21, ccc), consistent with multimerized p8TR episomes and TR duplication within the episomes (2). Therefore, all three LANA1-expressing cell lines had episomes but only two of four LANA114TG15→ AA-expressing cell lines had detectable p8TR episomes, indicating less efficient LANA114TG15→ AA mediation of episome persistence. Since the high rate of G418-resistant outgrowth in microtiter plates (>95% of wells) was consistent with episomal persistence in most or all these wells (1, 2), it is likely that LANA1 14TG15→ AA-2 and -4 initially had episomal DNA and then lost episomes as cells proliferated in culture.

Gardella gel analysis was performed again with F-LANA1 and LANA1 14TG15→ AA-expressing cells after 53 days of G418 selection. All three F-LANA1 cell lines had episomal DNA (Fig. 4B, lanes 1 to 3), most of which migrated near to covalently closed circular p8TR plasmid (Fig. 4B, lane 8, ccc). LANA114TG15→ AA-2 (Fig. 4B, lane 5) and -4 (Fig. 4B, lane 7) again had no episomal DNA. However, in contrast to the results after 26 days of G418 selection, LANA114TG15→ AA-1 no longer had detectable episomal DNA (Fig. 4B, lane 4). LANA114TG15→ AA-3 still had a small amount of slowly migrating extrachromosomal DNA (Fig. 4B, lane 6, bracket). Therefore, after 53 days of G418 selection LANA1 efficiently maintained p8TR episomes in all cell lines but episomes persisted in only one of four LANA114TG15→ AA cell lines.

LANA1 14TG15→ AA is partially deficient for DNA replication.

Since LANA114TG15→ AA inefficiently mediated episome persistence despite associating with chromosomes (Fig. 2 and 3), we investigated whether LANA114TG15→ AA was compromised for DNA replication. Experiments assayed for replication of DNA with DpnI digestion to differentiate replicated from unreplicated p8TR DNA. p8TR was purified from Dam methylase-positive Escherichia coli, which methylates adenines at DpnI sites. DpnI restriction enzyme cleaves methylated sites but does not cleave these sites when adenine methylation is absent, as is the case after replication in mammalian cells, which lack Dam methylase.

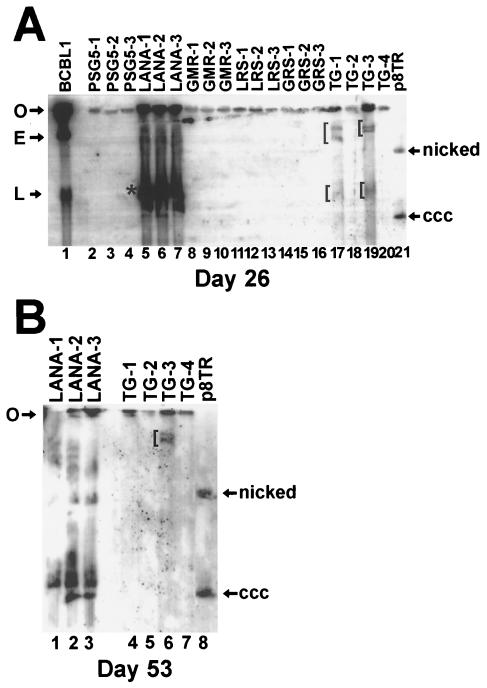

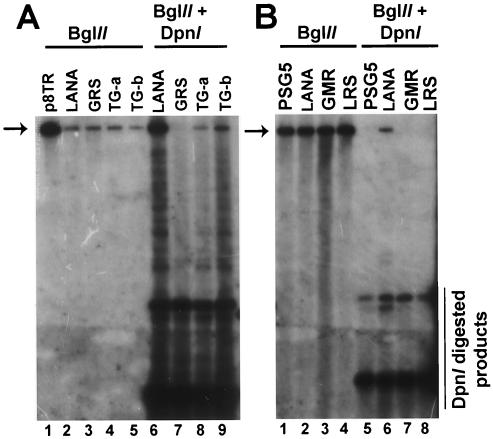

Therefore, p8TR DNA resistant to DpnI digestion indicates replication in mammalian cells. p8TR DNA was transfected into BJAB cells containing pSG5 vector, BJAB cells stably expressing F-LANA1, and into two independent BJAB cell lines stably expressing LANA114TG15→ AA, termed LANA114TG15→ AA-a and -b. After 48 h, low-molecular-weight DNA was extracted by the method of Hirt (16). DNA was digested with BglII, which linearizes p8TR (Fig. 5A, lanes 1 to 5, arrow) or with BglII and DpnI (Fig. 5A, lanes 6 to 9). As expected, BglII-linearized and DpnI-resistant p8TR DNA was present after transfection of F-LANA1-expressing cells (Fig. 5A, lane 6). BglII-linearized and DpnI-resistant DNA was also present in cells expressing LANA114TG15→ AA-a (Fig. 5A, lane 8) and LANA114TG15→ AA-b (Fig. 5A, lane 9), but the amount was significantly less than that in LANA1-expressing cells (Fig. 5A, compare lanes 8 and 9 with lane 6). The lower amount of replicated p8TR was not due to lower expression levels of LANA114TG15→ AA since immunoblots with anti-LANA1 monoclonal antibody demonstrated LANA114TG15→ AA was expressed at higher levels than F-LANA1 in both the LANA114TG15→ AA-a and -b cell lines (data not shown). Therefore, LANA114TG15→ AA is partially compromised for DNA replication.

FIG. 5.

LANA1 residues 5 to 13 are essential for DNA replication and residues 14 to 15 have a role in DNA replication. Assay of DNA replication of LANA1 mutants. BJAB cells containing the pSG5 vector or stably expressing F-LANA1 or LANA1 mutants were transfected with p8TR. After 48 h, low-molecular-weight DNA was digested with BglII or with BglII and DpnI. Digested DNA was resolved in agarose gels, transferred to nylon membranes, and detected with the TR probe. (A) Lane 1, p8TR plasmid; lane 2, F-LANA1; lane 3, LANA1 11GRS13→ AAA; lane 4, LANA1 14TG15→ AA-a; lane 5, LANA1 14TG15→ AA-b; lane 6, F-LANA1; lane 7, LANA1 11GRS13→ AAA; lane 8, LANA1 14TG15→ AA-a; lane 9, LANA1 14TG15→ AA-b. Signal below linearized p8TR but above the DpnI-digested fragments in lanes 6, 8, and 9 is due to partially replicated p8TR DNA. (B) Lane 1, pSG5; lane 2, F-LANA1; lane 3, LANA1 5GMR7→ AAA; lane 4, LANA1 8LRS10→ AAA; lane 5, pSG5; lane 6, F-LANA1; lane 7, LANA1 5GMR7→ AAA; lane 8, LANA1 8LRS10→ AAA. The arrow indicates linearized p8TR. This figure is representative of at least three experiments.

Residues 5 to 13 are essential for LANA1 mediated DNA replication.

In parallel experiments, we also investigated the possibility that LANA1 5GMR7→ AAA, LANA1 8LRS10→ AAA, and LANA1 11GRS13→ AAA might also be altered for DNA replication. p8TR DNA was transfected into BJAB cells containing pSG5, or stably expressing F-LANA1, LANA1 5GMR7→ AAA, LANA1 8LRS10→ AAA, and LANA1 11GRS13→ AAA. After 48 h, low-molecular-weight DNA was extracted and DNA was digested with BglII (Fig. 5A, lane 3, Fig. 5B, lanes 1 to 4, arrows) or with BglII and DpnI (Fig. 5A, lane 7, Fig. 5B, lanes 5 to 8). BglII-linearized and DpnI-resistant p8TR DNA was again present after transfection into BJAB cells expressing LANA1 (Fig. 5B, lane 6) but not in cells with only pSG5 (Fig. 5B, lane 5). BglII-linearized and DpnI-resistant DNA was also not present in cells expressing LANA1 5GMR7→ AAA (Fig. 5B, lane 7), LANA1 8LRS10→ AAA (Fig. 5B, lane 8) or LANA1 11GRS13→ AAA (Fig. 5A, lane 7), indicating absence of p8TR replication in these cells. The lack of detectable replication was not due to lower expression levels of LANA1 5GMR7→ AAA, LANA1 8LRS10→ AAA, and LANA1 11GRS13→ AAA than of LANA1, since immunoblot demonstrated that expression levels of the LANA1 mutated proteins were at least as high as that of LANA1 (data not shown). Therefore, alanine substitution of LANA residues 5GMR7, 8LRS10, and 11GRS13 abolished DNA replication.

Since mutation of LANA1 5GMR7, 8LRS10, 11GRS13, or 14TG15 to alanines all had effects on DNA replication, 17PLT19 and 20RGS22 were also assayed for DNA replication. GFP LANA1, GFP LANA1 17PLT19→ AAA and GFP LANA1 20RGS22→ AAA were each cotransfected with p8TR DNA into 293T cells, and Hirt extractions were performed 48 h later. Similar amounts of BglII-digested and DpnI-resistant DNA were present for GFP LANA1, GFP LANA1 17PLT19, and GFP LANA1 20RGS22 (data not shown). Therefore, alanine substitution of LANA1 amino acids 17PLT19 and 20RGS22 did not reduce DNA replication.

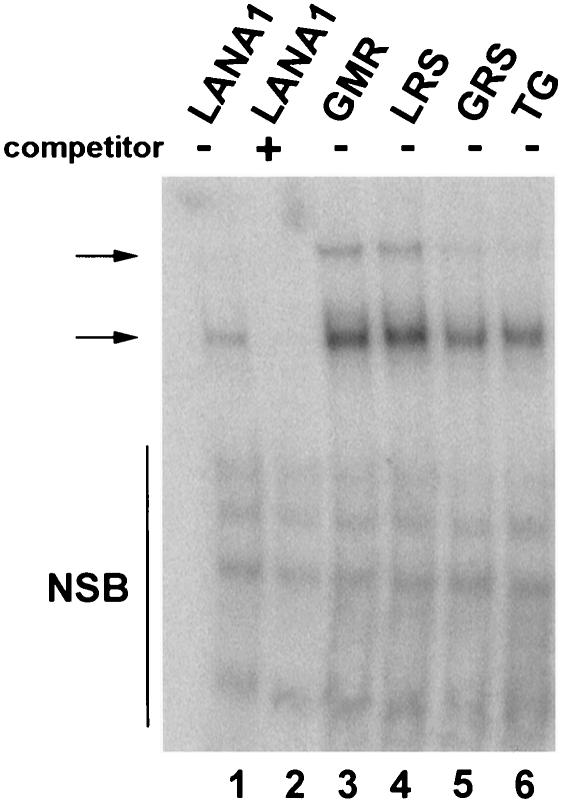

Mutations in the LANA1 N terminus do not affect binding to KSHV TR DNA.

We investigated the possibility that reduced binding to TR DNA accounted for the deficient DNA replication observed after mutation of LANA1 5GMR7, 8LRS10, 11GRS13, or 14TG15 to alanines. In vitro-translated F-LANA1, LANA1 5GMR7→ AAA, LANA1 8LRS10→ AAA, LANA1 11GRS13→ AAA and LANA1 14TG15→ AA were each assayed by electrophoretic mobility shift assays for the ability to bind TR probe. F-LANA1 (Fig. 6, lane 1), LANA1 5GMR7→ AAA (Fig. 6, lane 3), LANA1 8LRS10→ AAA (Fig. 6, lane 4), LANA1 11GRS13→ AAA (Fig. 6, lane 5) and LANA1 14TG15 → AA (Fig. 6, lane 6) each formed similar, specific complexes with TR DNA (Fig. 6, arrows). The complexes were similar to those previously observed for F-LANA1 and LANA1 (2) (and unpublished data). Therefore, mutation of LANA1 5GMR7, 8LRS10, 11GRS13, or 14TG15 to alanines does not affect DNA binding and the effects of these mutations on DNA replication are due to other factors.

FIG. 6.

Alanine substitutions at the LANA1 N terminus do not inhibit binding to TR DNA. Radiolabeled probe TR-13 was incubated with in vitro-translated F-LANA1 (lanes 1 and 2), LANA1 5GMR7→ AAA (lane 3), LANA1 8LRS10→ AAA (lane 4), LANA1 11GRS13→ AAA (lane 5), or LANA1 14TG15→ AA (lane 6), and electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed. Addition of a 100-fold excess of unlabeled competitor TR-13 is indicated (lane 2). Arrows indicate specific complexes. NSB, nonspecific bands. Free probe was run off the gel.

DISCUSSION

This work provides molecular genetic evidence that LANA1 residues 5 to 13 are essential for chromosome association, DNA replication, and episome maintenance. Alanine substitutions of 5GMR7, 8LRS10, or 11GRS13 each independently abolished these LANA1 functions. Interestingly, alanine substitutions of 14TG15 did not abolish chromosome association but significantly reduced DNA replication and episome persistence. In contrast, alanine substitutions of 17PLT19, or 20RGS22 did not affect LANA1 chromosome association or DNA replication.

The finding that LANA1 residues 5 to 13 are essential for chromosome association is consistent with other work where deletion of residues 1 to 22 or 1 to 15 abolished chromosome association (24, 35). LANA1 residues 5 to 13 likely associate with chromosomes via an interaction with a cell protein(s) associated with chromosomes. For instance, the cell protein EBP2 mediates EBV EBNA1 interaction with chromosomes to allow EBV episome persistence (21, 36). MeCP2 has been proposed as a candidate cell protein through which the LANA1 N terminus associates with chromosomes (24). Interaction with different chromosome associated proteins would be consistent with the finding that LANA1 and EBNA1 do not colocalize in coinfected primary effusion lymphoma cells (39). At least two EBNA1 regions mediate chromosome association (18, 28, 41). Of interest, the EBNA1 chromosome association regions and LANA1 5 to 13 are all rich in basic residues.

LANA1 amino acids 5 to 13 are also sufficient for chromosome association. LANA1 5-13 fused to GFP diffusely painted chromosomes. This finding further reinforces the importance of this sequence for LANA1 chromosome association and demonstrates that residues 14 to 22 are dispensable for chromosome association. These findings differ from other work in which LANA1 residues 1 to 15 fused to GFP only weakly associated with chromosomes in one of thirty mitotic cells and was usually seen in the nucleoplasm (31). Here, GFP LANA1 5-13 (and GFP LANA1 5-14) associated with chromosomes as frequently as did GFP LANA1 1-32 and was never noted to be excluded from mitotic chromosomes. It is possible that the different observations are due to the addition of an NLS to GFP LANA1 5-13 in this work. Another possibility is that cell type differences account for the differing results.

In full-length LANA1, the N terminus contains the dominant chromosome binding region. Although LANA1 contains a C-terminal chromosome association domain, it did not rescue LANA1 chromosome association when alanines were substituted for 5GMR7, 8LRS10, or 11GRS13. It is likely that the chromosome association roles of the N and C termini are different in the presence of KSHV episomes. When episomes are present, LANA1 concentrates to dots at sites of KSHV DNA along chromosomes (Fig. 3), instead of diffusely coating chromosomes (Fig. 2) (1). Intriguingly, the LANA1 C terminus concentrates to dots on mitotic chromosomes in the absence of episomes (M. Ballestas, T. Komatsu, and K. Kaye, 4th Int. Workshop on KSHV Related Agents, p. 32, 2001; unpublished observations).

Residues 5 to 13 are also essential for LANA1-mediated DNA replication since alanine substitutions for 5GMR7, 8LRS10, and 11GRS13 all abolished DNA replication. These results are consistent with work indicating the LANA1 N-terminal 90 or more residues are important for LANA1-mediated DNA replication (15, 17, 26, 27). The LANA1 C terminus binds KSHV TR DNA (8, 13, 27) and interacts with components of the origin recognition complex in vitro (27). Similarly, EBV EBNA1 and the EBV oriP associate with components of the origin recognition complex (6, 10). The LANA1 N terminus may also recruit factors essential for DNA replication. Alternatively, it is possible that the lack of chromosome association and inability to mediate DNA replication are directly linked. LANA1 mutants lacking the N-terminal chromosome binding region do not associate with chromatin during interphase (31). Association with chromatin may be important for efficient targeting to sites of cellular DNA replication and origin firing.

The essential role of LANA1 residues 5 to 13 in episome maintenance is consistent with the requirement for these amino acids for both chromosome association and DNA replication. In order for KSHV episomes to persist in proliferating cells, DNA must replicate and efficiently segregate to progeny nuclei. Substitution of alanines for 5GMR7, 8LRS10, and 11GRS13 abolished both LANA1 DNA replication and chromosome association. These defects would prevent both episome replication and efficient segregation to progeny cells. These results are consistent with work in which deletion of LANA1 residues 1 to 22 abolished LANA1-mediated episome persistence. Substitution of histone H1 but not histone H2B for LANA1 1 to 22 reconstituted LANA1's ability to mediate episome persistence for 3 weeks (35). It is likely that histone H1 restored LANA1-mediated DNA replication in addition to chromosome association in these experiments.

LANA1 14TG15→ AA was partially deficient for DNA replication and episome persistence. The inefficient episome maintenance correlated with, and is likely due to, LANA1 14TG15→ AA's reduced DNA replication. LANA1 14TG15 may interact with a cell protein(s) that has a critical role in LANA1-mediated DNA replication. If episomes are not faithfully replicated prior to each cell division, they will eventually be diluted out in a proliferating cell line. LANA1 14TG15→ AA also selected for enlarged episomes. Since episome enlargement is due to increased number of TR elements and multimerization of input plasmids (2), the increased number of LANA1 binding sites may partially alleviate the LANA1 14TG15→ AA defect.

This work provides genetic support for a critical role of the LANA1 N terminus in chromosome association, DNA replication, and episome maintenance. Further work is necessary to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying these functions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elliott Kieff and members of the Kaye laboratory for helpful discussions and Carol Quink for assistance. Takashi Komatsu generated the GFP LANA1 plasmid.

This work was supported by grants CA85751 (to M.E.B.) and CA82036 (to K.M.K.) from the National Cancer Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ballestas, M. E., P. A. Chatis, and K. M. Kaye. 1999. Efficient persistence of extrachromosomal KSHV DNA mediated by latency-associated nuclear antigen. Science 284:641-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballestas, M. E., and K. M. Kaye. 2001. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 mediates episome persistence through cis-acting terminal repeat (TR) sequence and specifically binds TR DNA. J. Virol. 75:3250-3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bastien, N., and A. A. McBride. 2000. Interaction of the papillomavirus E2 protein with mitotic chromosomes. Virology 270:124-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cesarman, E., P. S. Moore, P. H. Rao, G. Inghirami, D. M. Knowles, and Y. Chang. 1995. In vitro establishment and characterization of two acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related lymphoma cell lines (BC-1 and BC-2) containing Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like (KSHV) DNA sequences. Blood 86:2708-2714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang, Y., E. Cesarman, M. S. Pessin, F. Lee, J. Culpepper, D. M. Knowles, and P. S. Moore. 1994. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. Science 266:1865-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaudhuri, B., H. Xu, I. Todorov, A. Dutta, and J. L. Yates. 2001. Human DNA replication initiation factors, ORC and MCM, associate with oriP of Epstein-Barr virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:10085-10089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cotter, M. A., II, and E. S. Robertson. 1999. The latency-associated nuclear antigen tethers the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus genome to host chromosomes in body cavity-based lymphoma cells. Virology 264:254-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotter, M. A., II, C. Subramanian, and E. S. Robertson. 2001. The Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen binds to specific sequences at the left end of the viral genome through its carboxy-terminus. Virology 291:241-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Decker, L. L., P. Shankar, G. Khan, R. B. Freeman, B. J. Dezube, J. Lieberman, and D. A. Thorley-Lawson. 1996. The Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is present as an intact latent genome in Kaposi's sarcoma tissue but replicates in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of Kaposi's sarcoma patients. J. Exp. Med. 184:283-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhar, S. K., K. Yoshida, Y. Machida, P. Khaira, B. Chaudhuri, J. A. Wohlschlegel, M. Leffak, J. Yates, and A. Dutta. 2001. Replication from oriP of Epstein-Barr virus requires human ORC and is inhibited by geminin. Cell 106:287-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fejer, G., M. M. Medveczky, E. Horvath, B. Lane, Y. Chang, and P. G. Medveczky. 2003. The latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus interacts preferentially with the terminal repeats of the genome in vivo and this complex is sufficient for episomal DNA replication. J. Gen. Virol. 84:1451-1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garber, A. C., J. Hu, and R. Renne. 2002. Latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA) cooperatively binds to two sites within the terminal repeat, and both sites contribute to the ability of LANA to suppress transcription and to facilitate DNA replication. J. Biol. Chem. 277:27401-27411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garber, A. C., M. A. Shu, J. Hu, and R. Renne. 2001. DNA binding and modulation of gene expression by the latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 75:7882-7892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gardella, T., P. Medveczky, T. Sairenji, and C. Mulder. 1984. Detection of circular and linear herpesvirus DNA molecules in mammalian cells by gel electrophoresis. J. Virol. 50:248-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grundhoff, A., and D. Ganem. 2003. The latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus permits replication of terminal repeat-containing plasmids. J. Virol. 77:2779-2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirt, B. 1967. Selective extraction of polyoma DNA from infected mouse cell cultures. J. Mol. Biol. 26:365-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu, J., A. C. Garber, and R. Renne. 2002. The latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus supports latent DNA replication in dividing cells. J. Virol. 76:11677-11687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hung, S. C., M. S. Kang, and E. Kieff. 2001. Maintenance of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) oriP-based episomes requires EBV-encoded nuclear antigen-1 chromosome-binding domains, which can be replaced by high-mobility group-I or histone H1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:1865-1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ilves, I., S. Kivi, and M. Ustav. 1999. Long-term episomal maintenance of bovine papillomavirus type 1 plasmids is determined by attachment to host chromosomes, which Is mediated by the viral E2 protein and its binding sites. J. Virol. 73:4404-4412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones, D., M. E. Ballestas, K. M. Kaye, J. M. Gulizia, G. L. Winters, J. Fletcher, D. T. Scadden, and J. C. Aster. 1998. Primary-effusion lymphoma and Kaposi's sarcoma in a cardiac-transplant recipient. N. Engl. J. Med. 339:444-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kapoor, P., and L. Frappier. 2003. EBNA1 partitions Epstein-Barr virus plasmids in yeast cells by attaching to human EBNA1-binding protein 2 on mitotic chromosomes. J. Virol. 77:6946-6956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kedes, D. H., M. Lagunoff, R. Renne, and D. Ganem. 1997. Identification of the gene encoding the major latency-associated nuclear antigen of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Clin. Investig. 100:2606-2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellam, P., C. Boshoff, D. Whitby, S. Matthews, R. A. Weiss, and S. J. Talbot. 1997. Identification of a major latent nuclear antigen, LNA-1, in the human herpesvirus 8 genome. J. Hum. Virol. 1:19-29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krithivas, A., M. Fujimuro, M. Weidner, D. B. Young, and S. D. Hayward. 2002. Protein interactions targeting the latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus to cell chromosomes. J. Virol. 76:11596-11604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lehman, C. W., and M. R. Botchan. 1998. Segregation of viral plasmids depends on tethering to chromosomes and is regulated by phosphorylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:4338-4343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim, C., D. Lee, T. Seo, C. Choi, and J. Choe. 2003. Latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus functionally interacts with heterochromatin protein 1. J. Biol. Chem. 278:7397-7405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim, C., H. Sohn, D. Lee, Y. Gwack, and J. Choe. 2002. Functional dissection of latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus involved in latent DNA replication and transcription of terminal repeats of the viral genome. J. Virol. 76:10320-10331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marechal, V., A. Dehee, R. Chikhi-Brachet, T. Piolot, M. Coppey-Moisan, and J. C. Nicolas. 1999. Mapping EBNA-1 domains involved in binding to metaphase chromosomes. J. Virol. 73:4385-4392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moore, P. S., and Y. Chang. 1995. Detection of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in Kaposi's sarcoma in patients with and without HIV infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 332:1181-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohno, S., J. Luka, T. Lindahl, and G. Klein. 1977. Identification of a purified complement-fixing antigen as the Epstein-Barr virus-determined nuclear antigen (EBNA) by its binding to metaphase chromosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:1605-1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piolot, T., M. Tramier, M. Coppey, J. C. Nicolas, and V. Marechal. 2001. Close but distinct regions of human herpesvirus 8 latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 are responsible for nuclear targeting and binding to human mitotic chromosomes. J. Virol. 75:3948-3959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rainbow, L., G. M. Platt, G. R. Simpson, R. Sarid, S.-J. Gao, H. Stoiber, C. S. Herrington, P. S. Moore, and T. F. Schulz. 1997. The 222- to 234-kilodalton latent nuclear protein (LNA) of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) is encoded by orf73 and is a component of the latency-associated nuclear antigen. J. Virol. 71:5915-5921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Renne, R., M. Lagunoff, W. Zhong, and D. Ganem. 1996. The size and conformation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) DNA in infected cells and virions. J. Virol. 70:8151-8154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwam, D. R., R. L. Luciano, S. S. Mahajan, L. Wong, and A. C. Wilson. 2000. Carboxy terminus of human herpesvirus 8 latency-associated nuclear antigen mediates dimerization, transcriptional repression, and targeting to nuclear bodies. J. Virol. 74:8532-8540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shinohara, H., M. Fukushi, M. Higuchi, M. Oie, O. Hoshi, T. Ushiki, J. Hayashi, and M. Fujii. 2002. Chromosome binding site of latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is essential for persistent episome maintenance and is functionally replaced by histone H1. J. Virol. 76:12917-12924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shire, K., D. F. Ceccarelli, T. M. Avolio-Hunter, and L. Frappier. 1999. EBP2, a human protein that interacts with sequences of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 important for plasmid maintenance. J. Virol. 73:2587-2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skiadopoulos, M. H., and A. A. McBride. 1998. Bovine papillomavirus type 1 genomes and the E2 transactivator protein are closely associated with mitotic chromatin. J. Virol. 72:2079-2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soulier, J., L. Grollet, E. Oksenhendler, P. Cacoub, D. Cazals-Hatem, P. Babinet, M. F. d'Agay, J. P. Clauvel, M. Raphael, L. Degos, et al. 1995. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in multicentric Castleman's disease. Blood 86:1276-1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szekely, L., F. Chen, N. Teramoto, B. Ehlin-Henriksson, K. Pokrovskaja, A. Szeles, A. Manneborg-Sandlund, M. Lowbeer, E. T. Lennette, and G. Klein. 1998. Restricted expression of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-encoded, growth transformation-associated antigens in an EBV- and human herpesvirus type 8-carrying body cavity lymphoma line. J. Gen. Virol. 79:1445-1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szekely, L., C. Kiss, K. Mattsson, E. Kashuba, K. Pokrovskaja, A. Juhasz, P. Holmvall, and G. Klein. 1999. Human herpesvirus-8-encoded LNA-1 accumulates in heterochromatin- associated nuclear bodies. J. Gen. Virol. 80:2889-2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu, H., D. F. Ceccarelli, and L. Frappier. 2000. The DNA segregation mechanism of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1. EMBO Rep. 1:140-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yates, J., N. Warren, D. Reisman, and B. Sugden. 1984. A cis-acting element from the Epstein-Barr viral genome that permits stable replication of recombinant plasmids in latently infected cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:3806-3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yates, J. L., N. Warren, and B. Sugden. 1985. Stable replication of plasmids derived from Epstein-Barr virus in various mammalian cells. Nature 313:812-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]