Abstract

The factor inhibiting HIF-α (FIH-1) hydroxylates many ankyrin repeat-containing proteins including IκBα. It is widely speculated that hydroxylation of IκBα has functional consequences, but the effects of hydroxylation have not been demonstrated. We prepared hydroxylated IκBα and compared it to the unhydroxylated protein. Urea denaturation and amide H/D exchange experiments showed no change in the “foldedness” upon hydroxylation. Surface plasmon resonance measurements of binding to NFκB showed no difference in the NFκB binding kinetics or thermodynamics. Ubiquitin-independent proteasomal degradation experiments showed no difference in the half-life of the protein. Thus, it appears that hydroxylation of IκBα by FIH-1 is inconsequential, at least for the functions we could assay in vitro.

Keywords: hypoxia-inducible factor, ankyrin repeat, post-translational modification, protein folding, proteasome degradation

Introduction

The hypoxia-inducible transcription factors (HIFs) mediate the genomic response to oxygen deficiency (hypoxia) in multicellular organisms. These transcription factors are α/β heterodimers that bind DNA and activate transcription of over 70 target genes during cellular hypoxia [1]. HIFs “sense” the level of oxygen by being modified by four oxygen-sensitive hydroxylases; three prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs) and one asparaginyl hydroxylase, factor inhibiting HIF (FIH) [2]. These hydroxylases are all members of the 2-oxoglutarate (2OG)–dependent dioxygenase superfamily and their activity depends on the cellular oxygen concentration. Under normoxia, the HIF-α subunit is hydroxylated by the PHDs leading to ubiquitination and rapid degradation. In addition, FIH-mediated hydroxylation FIHdirectly regulates the transcriptional activity of the HIF-α proteins by inhibiting binding of the obligate CREB-binding protein (CBP)/p300 coactivator proteins to the HIF-α C-terminal transactivation domain (CAD), further repressing transcriptional activity [3,4]. At the onset of hypoxia, hydroxylase activity is greatly reduced, resulting in HIF protein accumulation and derepression of CAD activity, and consequently robust transcriptional activation.

Recent work has demonstrated that, in addition to hydroxylating HIF-α, FIH can also hydroxylate the ankyrin domains of a wide range of proteins. Ankyrin repeat domains contain a consensus sequence that has been shown to bind to, and be a good substrate for, FIH [5]. Searches for alternative substrates of FIH identified IκB and Notch family members and ASB4 (ankyrin repeat and SOCS box protein 4) as substrates of FIH [5-10]. These intracellular proteins all contain ankyrin repeat domains (ARDs), and in each case the target asparagine residues lie within the ARD. Ankyrin repeat-containing proteins are found in all three phyla, and are present in some 6% of eukaryotic protein sequences [11,12]. Thus the consequences of FIH-dependent hydroxylation could be wide-ranging if modification of these alternate substrates has functional significance. Although these alternative substrates have been shown to be hydroxylated in vitro, in cultured cells, and in vivo, it remains difficult to establish functional consequences of the hydroxylation event in a rigorous manner.

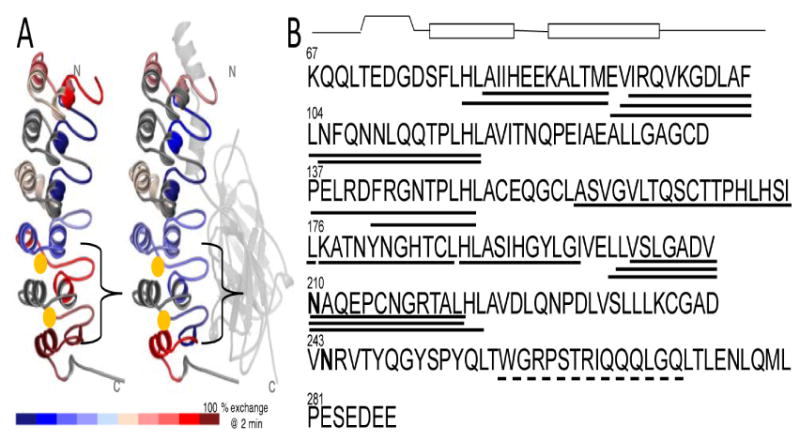

Since hydroxylation of HIF-α potentiates its degradation, and the degradation rate of IκBα is a sensitive parameter in control of the NFκB signaling pathway [13,14], we were particularly interested in the possible functional role of hydroxylation in regulating the stability and/or degradation of IκBα. Indeed, human IκBα is hydroxylated by FIH at positions 210 and 244 (Figure 1A) with Asn 244 being the preferred site [10]. The two hydroxylated asparagines are at the interfaces between AR4-AR5 and AR5-AR6, which is the weakly-folded part of IκBα [15] that folds on binding of NFκB(Figure 1A) [16]. In previous work, we showed that stabilization of AR5-AR6 in IκBα altered its intracellular half-life and had drastic functional consequences [17]. Given that hydroxylation has been shown to stabilize consensus ARD proteins, it is possible that hydroxylation might increase the stability of the IκBα ARD, and therefore influence its functional activity [18]. Here we present a full biophysical characterization of FIH-hydroxylated IκBα, including binding of the hydroxylated protein to NFκB and proteasomal degradation rates.

Figure 1.

A) Structure of IκBα from the NFκB-IκBα complex showing the relative amide exchange in free IκBα vs. NFκB-bound IκBα. The red regions exchanged nearly all of their amides within 2 min, whereas the blue regions exchange less. Gold spheres mark the positions of the two hydroxylated asparagines, Asn 210 and Asn 244. B) Sequence of IκBα showing the two hydroxylated asparagines in bold-face type. Above the sequence is the secondary structural representation of each ankyrin repeat. The lines underneath the sequence depict the peptides generated upon pepsin cleavage during the amide exchange experiment that were analyzed. The solid lines indicate peptides for which amide exchange can be quantitatively determined whereas the dashed lines indicate peptides for which the amide exchange can only be qualitatively assessed.

Materials and Methods

IκBα Expression and Purification

Human IκBα67-287 protein was expressed and purified as described previously [17]. Residues 67-287 comprise the entire ARD and the PEST sequence. This protein is truncated at the C-terminus, and is missing residues 288-317, but we have shown previously that it has identical folding and binding properties to the full-length ARD [19]. The final purification step was on a Superdex-75 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare) to ensure the absence of any aggregated species. The proteins were stored at 4°C and used within 3 days of gel filtration. Protein concentrations were determined by spectrophotometry, using extinction coefficient of 12,950 M-1 cm-1 for IκBα.

In vivo hydroxylation

In vivo hydroxylation was achieved by co-expressing IκBα behind the T7 promoter in a kanamycin resistant vector and Trx-6H-FIH [20] behind the T7 promoter in an ampicillin resistant vector in BL21 (DE3) cells. Hydroxylated IκBα was purified from the co-expression system as described above. Although some of the IκBα remained in a high molecular weight complex with FIH, monomeric, hydroxylated IκBα could be obtained after a final purification step on Superdex-75 gel filtration column.

Mass Spectrometry

Hydroxylated IκBα samples were analyzed by liquid chromatography (LC)-MS with electrospray ionization. All nanospray ionization experiments were performed by using a QSTAR-XL hybrid mass spectrometer (ABSciex) interfaced to a nanoscale reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatograph (Tempo) using a 10 cm-180 ID glass capillary packed with 5-μm Magic C-4 beads (Michrom). Buffer A was 98% H2O, 2% ACN, 0.2% formic acid, and 0.005% TFA and buffer B was 100% ACN, 0.2% formic acid, and 0.005% TFA. Peptides were eluted from the C-4 column into the mass spectrometer using a linear gradient of 25–80% Buffer B over 60 min at 400 μl/min. LC-MS data were acquired in TOF scan mode (400-2000). The parameters for ESI-MS were: IS 2.3 KV; DP 65 V; CAD 5 V. The data were processed with Analyst 2.0 software using Bayesian Protein Reconstruction tool in the mass range 20,000-30,000 with step mass of 1 Da ans S/N threshold of 20.

Equilibrium folding experiments

Equilibrium folding experiments were performed on an Aviv 202 spectropolarimeter (Aviv Biomedical, Lakewood, NJ, USA) with a Hamilton Microlab 500 titrator (Hamilton, Reno, NV, USA). Urea (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA, USA) was specially purified by dissolving it at a nominal concentration of 8M in water, and then treating with AG 501-X8 (D) resin (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) for 1 hour to remove cyanate contaminants [21]. Resin was filtered out with a 0.2μm filter and buffer salts were added to the purified urea. Urea concentrations were checked using refractometry [22]. Urea was used within 2 days of resin treatment to prevent re-accumulation of cyanate. A 1 cm fluorescence quartz cuvette containing 2.0 ml of 0.5–4 μM of the native protein in buffer (25 mM tris, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM EDTA, pH 7.5) and was titrated with denatured protein (7.3 – 8.4 M urea in buffer), in 30 to 40 injection steps. After each injection, samples were equilibrated with constant stirring at 80 rpm for 180s prior to data collection. The CD signal was collected at 225 nm, averaged 10 seconds, and the fluorescence signal was collected through a 320 cut-off filter with an excitation wavelength of 280nm, averaged over 2 to 5 seconds. Experiments were performed at 5°C unless otherwise stated.

Folding curves were fit to a two state folding model, assuming a linear dependence of the folding free energy on denaturant concentration [22]. The pre (native) and post (unfolded) transition baselines were treated as linearly dependent on denaturant concentration. The data was globally fit to equation 1.

where Sobs is the observed signal, p1 and p2 are the pre and post transition baselines, a1 and a2 their corresponding y-intercepts; ΔG is the folding free energy in water and m is the cooperativity parameter (m-value). The data were fit using a non-linear least square fitting algorithm in Kaleidagraph (Synergy Software, Reading, PA, USA).

Amide exchange experiments

Native state backbone amide exchange was measured as described previously [23]. To specifically probe the weakly-folded parts of the ARD, IκBα was incubated for 2 min in deuterated buffer at pH 7.4 and then the amide exchange was quenched by dilution into ice cold 0.1% TFA solution to bring the pH down to 2.2 and the temperature down to 0°C. The sample was immediately digested with an excess of immobilized pepsin and the digest mixture was frozen in liquid N2. All samples were analyzed on the same day by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry [24]. Eighteen peptides that cover 60% of the sequence were analyzed for both wild-type and hydroxylated IκBα. The centroids of the mass envelopes were measured and compared to undeuterated controls and corrected for back exchange as described previously [15].

Surface plasmon resonance binding experiments

Sensorgrams were recorded on a Biacore 3000 instrument using streptavidin chips as described [19]. NFκB was biotinylated and immobilized as described; 150 RU, 250 RU, and 350 RU of NFκB (p50248-321/p65190–321) were immobilized. Wild type IκBα (0.02–1.6 nM) was injected for 5 min and dissociation was measured for 20 min at 25 °C at 50 μL/min. Regeneration was achieved by a 1 min pulse of 3 M urea in running buffer. Data were fit using the BiaEvaluation 2.0 software and plotted in Origin 7.0.

Proteasome degradation experiments

Proteasome degradation assays were performed basically as described [17]. IκBα (1 μM), freshly purified by size-exclusion chromatography, was incubated with 100nM bovine 20S proteasome (a gift from G. Ghosh) for 0 min, 15 min, 30 min, 60 min, 90 min, or 120 min at 25 °C in 20 mM Tris, 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT (pH 7.0). Degradation reactions were quenched by boiling with SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Intact IκBα was separated by SDS-PAGE (13% polyacrylamide gel) and visualized using Western blots probed with sc-847 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies) followed by anti-rabbit HRP conjugate.

Results

Preparation and characterization of FIH-1-hydroxylated IκBα

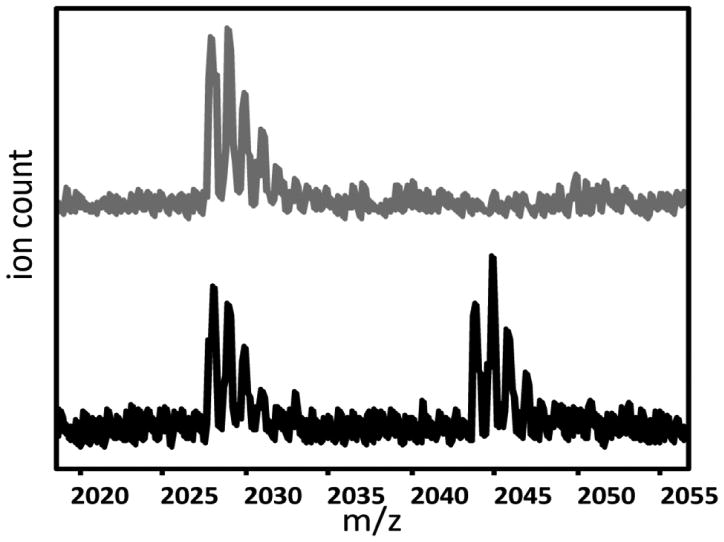

Several different approaches to obtaining fully-hydroxylated IκBα were attempted, including in vitro incubation with either purified FIH or lysates from E. coli cells expressing FIH. The FIH and IκBα appeared to form a tight complex prior to hydroxylation, and only partial hydroxylation was observed under initial in vitro hydroxylation conditions tested (data not shown). Co-expression of the IκBα with FIH in E. coli finally resulted in sufficient yields of hydroxylated protein. Mass spectrometric analysis of the hydroxylated protein compared to unhydroxylated controls showed that the protein was fully hydroxylated with only one predominant peak at 24,427 Da after deconvolution of the multiply charged species, as compared to the unhydroxylated control, which had a mass of 24,394 Da. Others have shown that FIH hydroxylates IκBα at Asn 210 and Asn 244, but the hydroxylation at 244 occurs more readily [10]. Pepsin digestion of the hydroxylated protein gave four peptides spanning residues 203-221 (Figure 1). Analysis of these peptides showed that at least 50% of the IκBα was hydroxylated also at Asn 210 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

MALDI-Tof mass spectra of the peptide corresponding to residues 202-221 (m/z 2028) from wild type IκBα (grey) and hydroxylated IκBα. Although quantitation is not possible due to the expected difference in ionization between the hydroxylated and unhydroxylated peptides, it is clear that a substantial amount of Asn 210 is hydroxylated.

Equilibrium unfolding experiments

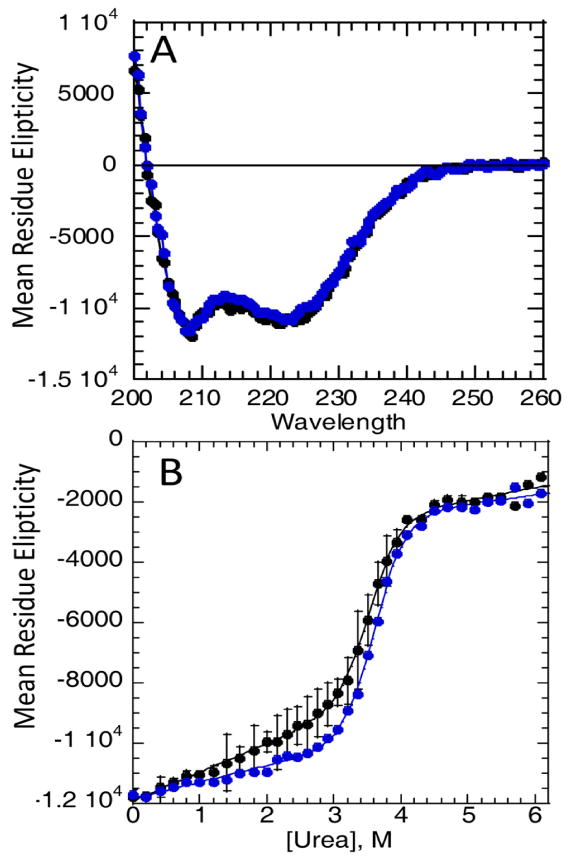

The hydroxylated protein displayed high α-helical secondary structure content, as indicated by the far-UV circular dichroism (CD) spectrum, which was not different from the wild type(Figure 3A). To probe the stability of the FIH hydroxylated IκBα, titration experiments were performed to unfold the protein in urea monitoring the CD signal at 222 nm. Although IkBa is prone to aggregation and is not thermally denaturable, at pH 7.5, in 50 mM NaCl, 1mM DTT, 25 mM Tris-HCl buffer, the refolding upon chemical denaturation was >95% reversible, as shown previously [23]. The CD signal changed upon addition of denaturant and displayed a sharp transition, typical of a cooperatively folded unit, but with a sloping pre-transition baseline which we have previously assigned to the weakly-folded AR5-6 region [23]. Multiple experiments on the hydroxylated versus wild type IκBα were performed, however the equilibrium denaturation properties of the hydroxylated protein were not different from those of wild type IκBα (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

A) Circular Dichroism (CD) spectra of wildtype (black) and hydroxylated (blue) IκBα. B) Equilibrium urea denaturation of IκBα (black) and hydroxylated IκBα (blue) at 3 μM total protein concentration at 5°C, (conditions described in Materials and Methods) followed by the CD signal at 225nm. The standard error of the mean from several experiments is also plotted. The data were fit assuming a sloping baseline giving for the wild type protein ΔG = -9.1 ± 0.7 kcal/mol, m=2.6 ± 0.2 and for the hydroxylated protein ΔG = -9.3 ± 0.5 kcal/mol, m=2.6 ± 0.13.

Amide hydrogen exchange experiments

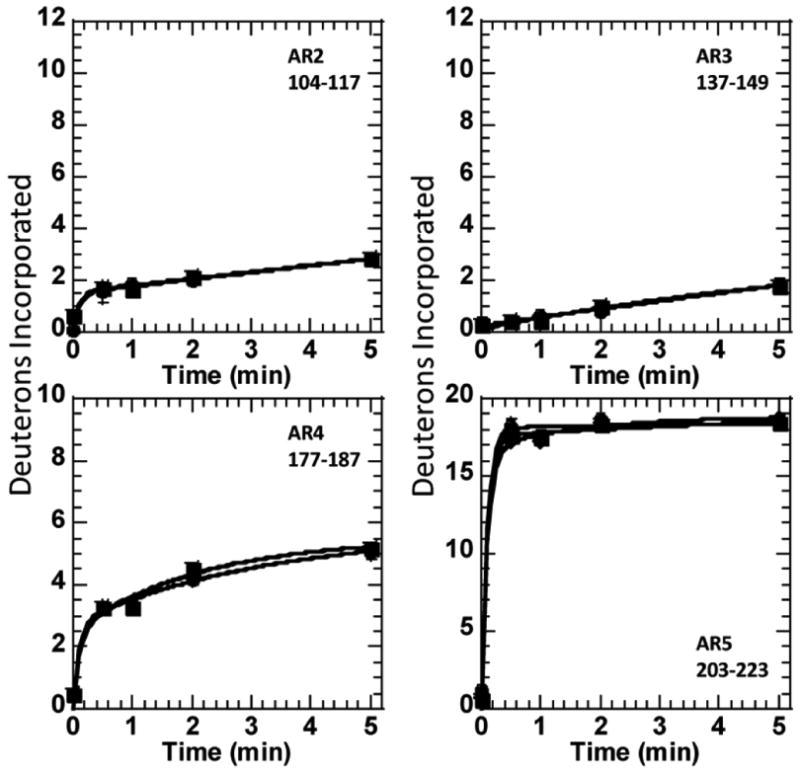

Native state amide exchange monitored by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry is a sensitive probe of the folded state of proteins in general, and is highly informative in IκBα because pepsin digestion after exchange produces fragments of similar secondary structure from each repeat that can be directly compared [15]. We have previously shown that mutation of only two residues in AR6 pre-fold the weakly-folded part, and this is most clearly shown by a dramatic decrease in amide exchange (a difference of some 5 deuterons) in AR5 and AR6 in this pre-folded mutant [17]. Figure 4 shows plots of the amide exchange of several peptides corresponding to regions of AR4-AR5. Comparison of the hydroxylated IκBα to the wild type protein shows no difference in amide exchange. This mass spectrometry experiment is particularly important because here the peptides corresponding to the hydroxylated protein are separated (by virtue of their difference in mass) from those of the unhydroxylated protein, even if they are present in the same mixture. Thus, this experiment allows us to compare the fully hydroxylated protein to the protein with only a hydroxyl at Asn 244 in the same experiment. It is clear from the plots in Figure 4 that again, no differences were observed in the “foldedness” of IκBα due to FIH hydroxylation. Although the peptide of mass 1767 from AR6 could not be analyzed quantitatively, this region also did not differ as assessed by qualitative comparisons of the mass envelopes.

Figure 4.

Plots of the amide H/D exchange over five minutes into regions of IκBα or hydroxylated IκBα. In the case of the peptides covering the Asn 210, only the peptide of mass 2165 is presented, but all the peptides from this region gave the same results. For this peptide, three data sets are presented. Data for the unhydroxylated protein was obtained from a separate unhydroxylated sample as well as from the unhydroxylated protein present in the sample of hydroxylated protein.

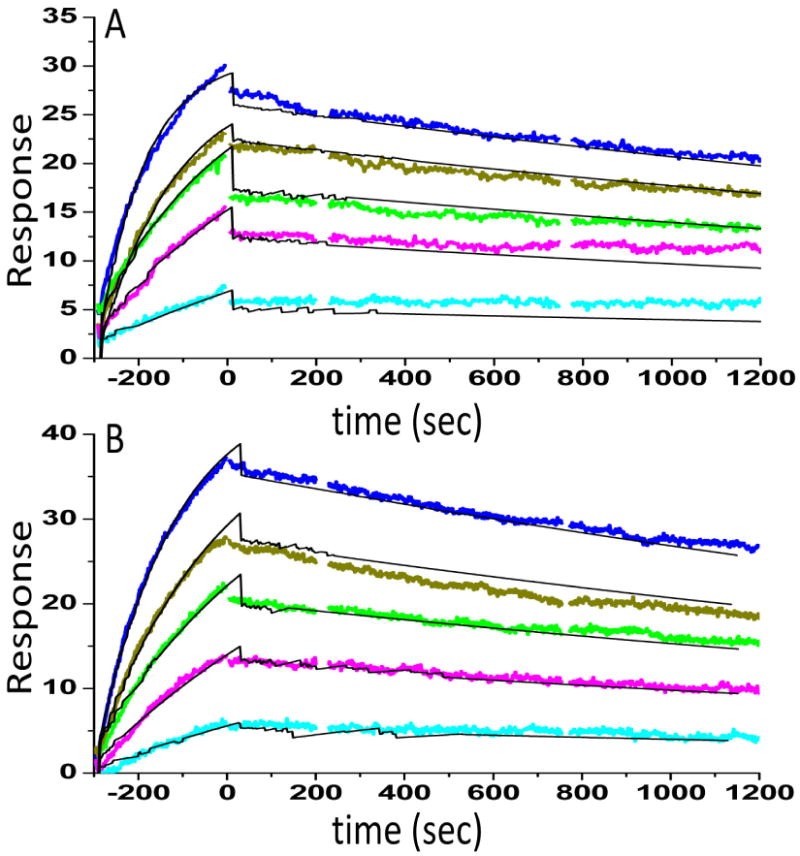

Binding to NFκB by surface plasmon resonance

To probe whether the hydroxylation affects NFκB binding, surface plasmon resonance binding kinetics experiments were performed. As shown previously, IκBα binds extremely tightly to NFκB [19]. The binding experiments showed that at most, hydroxylation had little, if any, effect on NFκB binding (KD of the wild type protein was 62 ±12 pM whereas that for the hydroxylated protein was 88 ±14 pM) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Surface plasmon resonance (Biacore) binding kinetics of the interaction between NFκB and either wild type (A) or hydroxylated (B) IκBα was performed as previously described [19]. NFκB(p50248-321/p65190–321) was biotinylated at the N-terminus of p65 and immobilized on a streptavidin sensor chip. IκBα (0.12, 0.34, 0.56, 0.95, 1.56 nM) was the flowing analyte. The data were fit using a simple 1:1 binding model yielding for the wild type protein ka = 6 × 106 M-1s-1, kd = 2.3 × 10-4, RMAX = 28.3, X2 = 0.55, and KD = 62 ±12 pM and for the hydroxylated protein ka = 4 × 106 M-1s-1, kd= 2.8 × 10-4, RMAX = 44.3, X2 = 0.74, and KD = 88 ±14 pM.

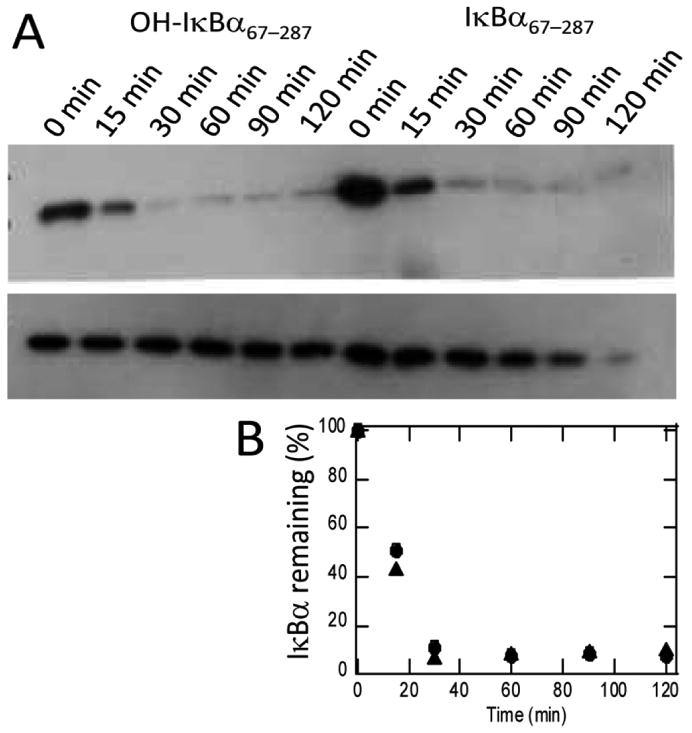

Proteasomal degradation

We have previously shown that IκBα is rapidly degraded in vitro and in vivo by the 20S proteasome [17]. This process is ubiquitin independent, but rather depends on a degron in the C-terminal part of the protein that might be sensitive to FIH hydroxylation [25]. To probe whether FIH hydroxylation affected the degradation rate of IκBα by the 20S proteasome, similar in vitro experiments were performed. Figure 6 shows that the degradation of FIH--hydroxylated IκBα is not significantly different from that of wild type IκBα. Quantitation of the bands by densitometry gives a half-life of 15 min for both the hydroxylated and unhydroxylated protein.

Figure 6.

Proteasome degradation experiments were performed as described in the Materials and Methods section. (A) Samples were taken at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min and quenched by addition of gel loading buffer. The amount of remaining IκBα was analyzed by SDS Page and Western blotting by comparing the sample containing proteasome (top gel) with the sample that did not contain proteasome (bottom gel). (B) Densitometric quantitation of the gels shown in A confirms the similar degradation rates of IκBα (●) and hydroxylated IκBα (▲).

Discussion

The NFκB signaling pathway is controlled by several inhibitor proteins, but IκBα is responsible for the rapid response after acute stress signals [26]. Properties of IκBα including its “foldedness”, intracellular half-life, and binding affinity for NFκB dimers are all exquisitely balanced in order to maximize pathway response and control [14]. In addition, NFκB signaling has previously been shown to be induced by hypoxia although the mechanism of induction is not fully understood [27,28]. Previous reports indicated a slightly enhanced inhibitory action of hydroxylated IκBα (that would presumably be suppressed by hypoxia) but siRNA-mediated suppression of FIH actually reduced NFκB activity [10]. Thus, although a functional significance would make a lot of sense, the evidence was tenuous at best. In previous work, we have demonstrated that we can subtly perturb the “foldedness” of the IκBα ARD and consequently its various functions, including NFκB binding and intracellular half-life through the use of stabilizing mutations [17,23]. Here we used the same experimental approaches to analyze the consequences of FIH hydroxylation on the “foldedness” and function of IκBα.

Others have shown that IκBα is hydroxylated by FIH at two asparagine residues, Asn 210 and 244, the latter of which is more readily hydroxylated [10]. In attempting to hydroxylate IκBα with FIH in vitro, we observed that a tight complex forms between the two proteins as has been seen for FIH and other ARD-containing proteins [18]. This complex was so tight as to make it difficult to separate the IκBα from the FIH to obtain reasonable yields of fully hydroxylated protein from in vitro reactions. Instead, from co-expression, we were able to obtain monomeric hydroxylated IκBα in reasonable yields. Electrospray Q-TOF mass spectrometry of the intact hydroxylated IκBα showed a single peak with a mass approximately 32 Da higher than IκBα suggesting that the protein was 100% hydroxylated at two sites. Pepsin digestion followed by MALDI mass spectrometry, which is not quantitative and is expected to cause at least some fragmentation of the hydroxyl group, showed that at least 50% of Asn 210 was hydroxylated. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that the protein is 100% hydroxylated at Asn 244 and at least 50% hydroxylated at Asn 210.

Equilibrium unfolding experiments showed equal stability of the FIH hydroxylated IκBα and consistent with this result, native state amide H/D exchange to probe the backbone dynamics also showed no difference between unhydroxylated and hydroxylated IκBα across all of the ankyrin repeats. Importantly, even though the protein may not have been completely hydroxylated, the hydroxylated and unhydroxylated protein fragments separate by mass and could be simultaneously analyzed from the same sample.

Previous indirect DNA binding activity (EMSA assays) of NFκB from nuclear extracts had suggested addition of FIH reduced the binding of NFκB [10]. We previously showed that EMSA assays do not accurately recapitulate the intracellular binding affinity of the NFκB-IκBα interaction, but that surface plasmon resonance with specifically biotinylated NFκB does [19]. We therefore measured the binding affinity of the hydroxylated IκBα in the same manner and compared it to the unhydroxylated protein. The results clearly showed that hydroxylation had minimal effects on the binding affinity.

Finally, we previously showed that the intracellular half-life of IκBα is exquisitely sensitive to the “foldedness” of AR5 and AR6 [17]. We also showed that intracellular half-life of free IκBα is rapid because of proteasomal degradation of IκBα that is ubiquitin independent and likely involves some form of the 20S proteasome [25]. As few as two mutations in AR6 dramatically altered both the intracellular half-life and the in vitro half-life in the presence of 20S proteasome preparations [17]. Since intracellular half-life is one of the sensitive parameters that controls NFκB signaling, we were anticipating that FIH hydroxylation would alter the proteasomal sensitivity of IκBα. Again, however, both proteins had the same rate of degradation by 20S proteasomal preparations.

Thus, for every function we can rigorously and quantitatively measure in vitro, FIH hydroxylation of IκBα is inconsequential. It is possible that many of the ARD hydroxylations that have been observed are similarly inconsequential and that the consensus sequence that is being hydroxylated is an accidental substrate. On the other hand, we have shown that the FIH orthologue from Tribolium castaneum (red flour beetle) can also hydroxylate the Tribolium Notch analogue [29]. This implies that this “accidental” modification is highly conserved and may have some functional consequence other than alteration of stability or NFκB binding. FIH plays an important role in regulating metabolism, with the phenotype of the FIH knockout mice displaying elevated metabolism, including higher respiration and heart rate, as well as energy expenditure [30]. It is unclear at this stage whether this phenotype is mediated by the HIF or ankyrin repeat subtrates, although there is no obvious disruption to NFκB signalling.

It is interesting that a similar connundrum also plagues asparagine hydroxylation in the EGF-like domains of most extracellular proteins. Here too, no evidence that hydroxylation alters the structure or function of the EGF-like domain-containing proteins has been forthcoming. Yet, the beta aspartyl/asparaginyl hydroxylase knockout mice display a distinct developmental phenotype, which the authors concluded is due to altered hydroxylation of Jagged and probably also its receptor, Notch [31]. So, although the molecular consequences of EGF hydroxylation are yet to be defined, it obviously has an important physiological role. As mass spectrometry advances and more post-translational modifications are found, it will likely become more and more common that the functionally relevant substrates are few in a mix of unintentional ones. In addition, the functional consequences of such modifications may require years of experimentation to establish.

Acknowledgments

NIH P01GM071862-04 to EAK and funding from the National Health and Research Council of Australia to DJP.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:721–732. doi: 10.1038/nrc1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schofield CJ, Ratcliffe PJ. Oxygen sensing by HIF hydroxylases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:343–54. doi: 10.1038/nrm1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lando D, Peet DJ, Gorman JJ, Whelan DA, Whitelaw ML, Bruick RK. FIH-1 is an asparaginyl hydroxylase enzyme that regulates the transcriptional activity of hypoxia-inducible factor. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1466–71. doi: 10.1101/gad.991402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hewitson KS, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) asparagine hydroxylase is identical to factor inhibiting HIF (FIH) and is related to the cupin structural family. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26351–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cockman ME, Webb JD, Kramer HB, Kessler BM, Ratcliffe PJ. Proteomics-based identification of novel factor inhibiting hypoxia-inducible factor (FIH) substrates indicates widespread asparaginyl hydroxylation of ankyrin repeat domain-containing proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:535–46. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800340-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng X, et al. Interaction with factor inhibiting HIF-1 defines an additional mode of cross-coupling between the Notch and hypoxia signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3368–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711591105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman ML, et al. Asparaginyl hydroxylation of the Notch ankyrin repeat domain by factor inhibiting hypoxia-inducible factor. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24027–38. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704102200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cockman ME, Webb JD, Ratcliffe PJ. FIH-dependent asparaginyl hydroxylation of ankyrin repeat domain-containing proteins. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1177:9–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferguson JE, 3rd, Wu Y, Smith K, Charles P, Powers K, Wang H, Patterson C. ASB4 is a hydroxylation substrate of FIH and promotes vascular differentiation via an oxygen-dependent mechanism. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:6407–19. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00511-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cockman ME, et al. Posttranslational hydroxylation of ankyrin repeats in IkappaB proteins by the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) asparaginyl hydroxylase, factor inhibiting HIF (FIH) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14767–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606877103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Björklund AK, Ekman D, Elofsson A. Expansion of protein domain repeats. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:e114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mosavi LK, Cammett TJ, Desrosiers DC, Peng ZY. The ankyrin repeat as molecular architecture for protein recognition. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1435–48. doi: 10.1110/ps.03554604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Dea EL, Barken D, Peralta RQ, Tran KT, Werner SL, Kearns JD, Levchenko A, Hoffmann A. A homeostatic model of IkappaB metabolism to control constitutive NF-kappaB activity. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:111. doi: 10.1038/msb4100148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferreiro DU, Komives EA. Molecular Mechanisms of System Control of NF-kappaB Signaling by IkappaBalpha. Biochemistry. 2010;49:1560–7. doi: 10.1021/bi901948j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Croy CH, Bergqvist S, Huxford T, Ghosh G, Komives EA. Biophysical characterization of the free IkappaBalpha ankyrin repeat domain in solution. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1767–77. doi: 10.1110/ps.04731004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Truhlar SM, Torpey JW, Komives EA. Regions of IkappaBalpha that are critical for its inhibition of NF-kappaB.DNA interaction fold upon binding to NF-kappa. B Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18951–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605794103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Truhlar SME, Mathes E, Cervantes CF, Ghosh G, Komives EA. Pre-folding IkappaBalpha alters control of NF-kappaB signaling. J Mol Biol. 2008;380:67–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.02.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardy AP, Prokes I, Kelly L, Campbell ID, Schofield CJ. Asparaginyl beta-hydroxylation of proteins containing ankyrin repeat domains influences their stability and function. J Mol Biol. 2009;392:994–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bergqvist S, Croy CH, Kjaergaard M, Huxford T, Ghosh G, Komives EA. Thermodynamics reveal that helix four in the NLS of NF-kappaB p65 anchors IkappaBalpha, forming a very stable complex. J Mol Biol. 2006;360:421–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linke S, Hampton-Smith RJ, Peet DJ. Characterization of ankyrin repeat-containing proteins as substrates of the asparaginyl hydroxylase factor inhibiting hypoxia-inducible transcription factor. Methods Enzymol. 2007;435:61–85. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)35004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Street TO, Courtemanche N, Barrick D. Protein folding and stability using denaturants. Methods Cell Biol. 2008;84:295–325. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(07)84011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pace CN. Determination and analysis of urea and guanidine hydrochloride denaturation curves. 1986;131:266–80. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)31045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferreiro DU, Cervantes CF, Truhlar SM, Cho SS, Wolynes PG, Komives EA. Stabilizing IkappaBalpha by “consensus” design. J Mol Biol. 2007;365:1201–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mandell JG, Falick AM, Komives EA. Measurement of amide hydrogen exchange by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Analytical Chemistry. 1998;70:3987–3995. doi: 10.1021/ac980553g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathes E, O'Dea EL, Hoffmann A, Ghosh G. NF-kappaB dictates the degradation pathway of IkappaBalpha. EMBO J. 2008;27:1357–67. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoffmann A, Levchenko A, Scott ML, Baltimore D. The IkappaB-NF-kappaB signaling module: temporal control and selective gene activation. Science. 2002;298:1241–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1071914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmedtje JF, Ji YS, Liu WL, DuBois RN, Runge MS. Hypoxia induces cyclooxygenase-2 via the NF-kappaB p65 transcription factor in human vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:601–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zampetaki A, Mitsialis SA, Pfeilschifter J, Kourembanas S. Hypoxia induces macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2) gene expression in murine macrophages via NF-kappaB: the prominent role of p42/ p44 and PI3 kinase pathways. FASEB J. 2004;18:1090–1092. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0991fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hampton-Smith RJ, Peet DJ. From polyps to people: a highly familiar response to hypoxia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1177:19–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang N, et al. The asparaginyl hydroxylase factor inhibiting HIF-1alpha is an essential regulator of metabolism. Cell Metab. 2010;11:364–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dinchuk JE, et al. Absence of post-translational aspartyl beta-hydroxylation of epidermal growth factor domains in mice leads to developmental defects and an increased incidence of intestinal neoplasia. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:12970–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110389200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]