Abstract

Type I interferons (IFN-αβ) are pleiotropic cytokines critical for antiviral host defense, and the timing and magnitude of their production involve a complex interplay between host and pathogen factors. Mouse cytomegalovirus (a β-herpesvirus) is a persistent virus that induces a biphasic IFN-αβ response during the first days of infection. The cell types and molecular mechanisms governing these 2 phases are unique, with splenic stromal cells being a major source of initial IFN-αβ, requiring communication with B cells expressing lymphotoxin, a tumor necrosis factor family cytokine. Here we review the factors that regulate this lymphotoxin–IFN-αβ “axis” during cytomegalovirus infection, highlight how stroma-derived IFN-αβ contributes in other models, and discuss how deregulation of this axis can lead to pathology in some settings.

Introduction

The type I interferons (IFN-αβ) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family cytokines are critical for mounting effective immune defenses. In turn, deregulated expression of these cytokines can promote autoimmunity, highlighting their importance in maintaining immune homeostasis. The significance of IFN-αβ and TNF-related ligands in antiviral immunity is supported by the fact that most viruses have evolved counterstrategies to modulate their signaling. The herpesviruses are prime examples of this, where extensive coevolution with their hosts has resulted in the establishment of lifelong persistence/latency in the face of a robust immune response. The cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection model (a β-herpesvirus) provides an excellent opportunity to probe for mechanisms that regulate antiviral defenses, as >3% of the mouse genome is predicted to regulate immunity to this virus (Beutler and others 2005). CMV is particularly well suited for exploring immune defenses that are impacted by homeostatic signaling networks, because this virus establishes largely asymptomatic equilibrium with its immune-competent host. The lymphotoxin αβ (LTαβ)-LTβ receptor (LTβR) cytokine system is a master regulator of a multidimensional “immune circuit,” signaling both constitutively and inducibly to regulate stromal and hematopoietic cells in various tissues. Here we will discuss how the CMV model first exposed a role for LTαβ signaling in the regulation of IFN-αβ production by stromal cells and how this LTαβ-IFN-αβ “axis” may regulate other immune and/or disease processes.

Cytomegalovirus

Human CMV (HCMV) infects the majority of population (50%–90%) (Staras and others 2006), is usually acquired early in life, and is largely asymptomatic in healthy individuals. However, in persons with underdeveloped or compromised immunity, primary or reactivated HCMV infection can lead to serious disease (eg, congenital infection) (Pereira and others 2005). The robust reactivation of CMV from latency upon immune suppression highlights the need for constant immune surveillance to maintain homeostasis between this virus and its host over a lifetime of infection. Host-specific replication/evolution of the CMVs has hindered their study in heterologous animal models, and consequently, the mouse model of CMV (MCMV) infection is commonly used. MCMV displays similar tissue tropism, temporal regulation of gene expression, and pathogenesis to HCMV and has been an invaluable model for dissecting various mechanisms regulating immune control of CMV. Additionally, the rat, guinea pig, and rhesus monkey models of CMV infection have provided valuable immunological data (Kern 2006; Powers and Fruh 2008). It is notable that sequence divergence between CMVs is concentrated largely in the “nonessential” open reading frames (ORFs) that function mainly as immune modulators, highlighting how antiviral defenses drive host-specific CMV evolution. Consequently, studying the CMV–host relationship has yielded unique insight into the mechanisms that promote and maintain immune homeostasis over a lifetime of infection.

The Innate Immune Response Early During CMV Infection

IFN-αβ and natural killer (NK) cells are critical for innate control during the first few days of MCMV infection (Scalzo and others 2007). Early studies examined how IFN-αβ signaling regulates MCMV replication, both in vitro and in vivo (Osborn and Medearis 1966; Kern and others 1978; Grundy and others 1982; Chong and others 1983). It is difficult to dissect NK cell versus IFN-αβ functions, because in addition to acting directly on infected cells, IFN-αβ is critical for activating NK cell effector functions, promoting their cytotoxicity and proliferation/survival via signal transducer and activate of transcription (STAT1) and interleukin (IL)-15–dependent pathways (Orange and Biron 1996; Nguyen and others 2002). IFN-αβ is detectable in the serum at high levels as early as 6 h following MCMV infection (Grundy and others 1982) and peaks at 8–12 h before decreasing (Schneider and others 2008). There is a second wave of IFN-αβ production at ∼36–48 h detectable in organs and circulation, commensurate with high levels of IL-12, and this occurs in response to the first round of MCMV spread in vivo (Schneider and others 2008). Work by Biron and colleagues revealed that IL-12 is derived primarily from dendritic cells (DC) at this time, which then promotes STAT4-dependent IFN-γ production by NK cells, a pathway functionally separable from IFN-αβ-STAT1 NK cell cytotoxicity (Orange and others 1995; Dalod and others 2002; Nguyen and others 2002). Invariant NK-T cells also secrete high levels of IFN-γ at 36 h, requiring both IL-12 and IFN-αβ for maximal production (Tyznik and others 2008; Wesley and others 2008). Interestingly, invariant NK-T cells upregulate CD69 during the first phase of the innate cytokine response (∼12 h), but do not produce IFN-γ at this time (Tyznik and others 2008). In this review, we will primarily focus on the LTαβ-dependent pathways that regulate the initial phase of the IFN-αβ response to MCMV infection derived from splenic stromal cells.

Stromal Cells as Targets of MCMV Infection and Producers of IFN-αβ

At ∼8 h after MCMV infection, IFN-α and IFN-β production peaks in the spleen, liver, and serum (Schneider and others 2008). The levels then return to near background by 24 h, surging again at ∼36–48 h. MCMV requires ∼30 h to complete its replication cycle, and therefore, IFN-αβ production at 8 h is derived from cells responding to the primary virus inoculum, with the second phase occurring in response to the first round of MCMV spread/production in vivo. Physical separation of splenic stromal and hematopoietic cells at 8 h after infection revealed the stroma to be the major source of IFN-αβ and also the main cellular compartment where MCMV initially replicates (Schneider and others 2008). In contrast, the second phase of IFN-αβ production is derived primarily from DC (Dalod and others 2003), with contributions from both plasmacytoid DC and conventional DC (reviewed in Marshall and Geballe 2009; Loewendorf and Benedict 2010).

These results pointed to a lymphoid tissue stromal cell being a key regulator of the primary innate cytokine response to MCMV infection, but what is the nature of this stromal cell? Stromal cells help to maintain the 3-dimensional integrity and microarchitecture of lymphoid tissues, forming a basement structure where lymphocytes and antigen-presenting cells adhere, traffic, and congregate. Although stromal cell subsets are not nearly as well characterized as their hematopoietic counterparts, significant diversity does exist within this population (Kraal and Mebius 2006). Splenic stromal cell subsets are often identified based on their physical location [marginal zone (MZ), red pulp, or white pulp], expression of integrins and lectins (eg, MAdCAM-1, VACM-1, BP-3, gp38/podoplanin), and production of specific homeostatic chemokines (eg, CCL21 and CXCL13) (Mebius and Kraal 2005; Mueller and Germain 2009). However, they have remained somewhat enigmatic because of the many technical challenges associated with isolating and culturing them under conditions where they maintain their phenotype(s). For example, fibroblast reticular cells that normally reside in the T-cell zone continue to express several identifiable markers when cultured ex vivo (gp38, VCAM, ER-TR7), but they do not maintain expression of their “signature chemokine,” CCL21 (Katakai and others 2004; Link and others 2007). However, if these same cells are grown on a 3-dimensional matrix and subjected to high fluid flow rates, then CCL21 mRNA expression is induced (Tomei and others 2009). In short, this example highlights the complexities associated with trying to dissect the nature of the stromal cell(s) that respond to initial MCMV infection, or any other pathogen for that matter, as purifying stromal cell subsets and subjecting them to ex vivo analysis is not a straightforward task.

Recently, the location of the splenic stromal cells targeted by MCMV has been identified (Hsu and others 2009) (Fukuyama, Verma, Benedict, and Ware, unpublished observations). Cells infected by GFP-expressing MCMV are localized almost exclusively to the splenic MZ at 8 h. The MZ contains several specialized populations of stromal cells, one being marginal zone reticular cells (MRCs), which are phenotypically similar to fibroblast reticular cells dispersed throughout the spleen (Kraal and Mebius 2006). MRCs can be distinguished from MZ sinus endothelial cells by their CD31−/ER-TR7+ expression (Kraal and Mebius 2006). MRCs express various adhesion molecules (eg, MAdCAM-1, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1) that bind integrins on hematopoietic cell subsets (eg, MZ B cells, macrophage populations), preferentially maintaining these cells in the MZ. MRCs also form bridging channels and conduits, the structural “highways” that facilitate trafficking of hematopoietic cells and small proteins from the MZ to locales in the red and white pulp (Mebius and Kraal 2005; Zindl and others 2009). As the majority of circulating blood enters the spleen through the MZ sinus, MRCs are well positioned to function as first responders to pathogens or foreign antigens.

The first cells infected by MCMV in the MZ are likely MRCs, as they express CD29, MAdCAM-1, and ER-TR7. Initial infection of MRCs by MCMV appears very specific, not infecting closely juxtaposed endothelial cells or macrophages (Hsu and others 2009). Interestingly, recent work indicates that lymphoid tissue reticular cells may regulate peripheral T-cell tolerance (Fletcher and others 2010). Given that the same MRCs likely harbor latent CMV (Mercer and others 1988), it is tempting to speculate that CMV infection of these cells might impact tolerance. In this vein, CMV is frequently discussed as a potential cofactor in autoimmune disorders (Varani and others 2009), but direct causative proof in most cases has been difficult to obtain because of the high prevalence of CMV infection in the general population.

LTαβ-LTβR Regulation of Lymphoid Tissue Stroma

LTαβ-LTβR signaling impacts the development and/or microarchitecture of all lymphoid tissues (Ware 2005) (Fig. 1). Its requirement for lymph node (LN) development was first revealed in ltα-deficient mice (LTα−/−), a phenotype recapitulated in LTβR−/− and LTβ−/− mice (reviewed in Tumanov and others 2003b). LN development halts during embryogenesis because of a requirement for cross-talk between LTβR-expressing stromal cells and LTαβ-expressing lymphoid tissue inducer cells in the developing LN anlagen (Randall and others 2008). In contrast to LN, the spleen still forms in the genetic absence of LTαβ-LTβR signaling, but the development and/or differentiation of stromal cells in both the MZ and white pulp is altered (Tumanov and others 2003a; Zindl and others 2009). Blocking LTαβ-LTβR signaling in both neonates and adults has also revealed its requirement for the homeostatic maintenance of splenic stromal cells postembryogenesis (Ettinger and others 1996; Mackay and others 1997). In total, the role that LTαβ-LTβR signaling plays in the regulation of lymphoid tissue stroma at the developmental and homeostatic level is complex and multifaceted. Importantly, however, the many available genetic and pharmacologic tools provided a unique opportunity to assess its role in mounting host defenses to CMV, a persistent virus that targets lymphoid tissue stromal cells.

FIG. 1.

Lymphotoxin and the immediate tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family. The TNF family ligands bind their cognate receptors as soluble and/or cell-associated trimers, shown by the arrows. LTα1β2 and LIGHT bind the LTβR, recruiting TNF receptor–associated factor (TRAF) adaptors to the receptor and resulting in the liberation/stabilization of NFκB-inducing kinase (NIK). NIK then activates IKKα and the downstream noncanonical NFκB signaling pathway. Studies indicate that LTαβ-LTβR and NIK-dependent signaling contributes to initial interferon (IFN)-αβ production by splenic stromal cells during mouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV) infection.

Making the Link Between Lymphotoxin and IFN-αβ During HCMV Infection In Vitro

Initial studies in vitro suggested a role for LTαβ-LTβR signaling in regulating type I IFN during CMV infection. Triggering LTβR signaling during the first hours of HCMV infection in cultured fibroblasts dramatically amplifies IFN-β production (∼10–100-fold, varying upon the multiplicity of infection (MOI) of infection) (Benedict and others 2001). This is not unique to LTαβ-LTβR signaling, as LTα-TNF receptor (TNFR) signaling also enhanced IFN-β production. In addition, IL-2–activated human NK cells can function as “sources” of LTβR and TNFR ligands, similarly enhancing IFN-β production from HCMV-infected stromal cells, even at very low effector:target ratios (Iversen and others 2005). In all these scenarios, HCMV infection and LTβR/TNFR function cooperatively to induce IFN-β, with receptor signaling alone inducing no IFN-β and virus alone being a weak inducer. However, the 2 added commensurately, or within a few hours, induced high levels of IFN-β transcription and secretion, which inhibited viral spread in the cultures by a noncytolytic, reversible mechanism (Benedict and others 2001). Subsequent work from several groups has shown that HCMV imposes a direct, viral transcription–dependent block to early IFN-β transcription (Browne and others 2001), mediated, at least in part, by the immediate early-2 protein (Taylor and Bresnahan 2005, 2006; Jarvis and others 2006). The immediate early-2 block to IFN-β is thought to involve inhibition of NFκB, a key component of the IFN-β transcriptional enhancesome (Maniatis and others 1998). Notably, NFκB activation is absolutely required for LTβR/TNFR signaling to cooperatively induce IFN-β transcription in HCMV-infected cells (Benedict and others 2001). Therefore, we would propose a model where if an extrinsic activator of NFκB (ie, LTβR, TNFR, etc.) signals concurrently upon initial HCMV infection of a stromal cell, this can circumvent an HCMV-imposed block to IFN-β transcription. Consequently, multiple factors must be considered when assessing the innate cytokine response during CMV infection, as both the host signaling pathways and viral countermeasures impact its magnitude.

The LT-IFN-αβ Axis In Vivo During MCMV Infection

Although the results with HCMV-infected fibroblasts suggested the existence of an LT-IFN-αβ axis operable in stromal cells, this needed to be examined in vivo. Initial studies found that mice deficient for LTαβ-LTβR signaling were more sensitive to MCMV-induced death (Benedict and others 2001). Subsequent studies revealed that LTα−/−, LTβ−/−, and LTβR−/− mice could not control acute MCMV replication (Banks and others 2005). Intriguingly, at high doses of MCMV infection, a dramatic apoptotic collapse of splenic lymphocytes and DC occurs at 2–3 days after infection in mice lacking LTαβ-LTβR signaling. A similar massive splenocyte death is observed in mice lacking the type I IFN receptor (IFN-αβR), again highlighting a parallel between these 2 innate cytokine systems. Induction of IFN-β mRNA was dramatically reduced in the spleen of LTα−/− and LTβ−/−/LIGHT−/− mice at 8 h after MCMV infection (Schneider and others 2008). Injection of an agonistic anti-LTβR antibody restores IFN-β mRNA levels to a large degree in these genetically deficient mice and rescues the vast majority of splenocyte apoptosis, but cannot amplify the type I IFN response in wild-type mice. Taken together, these data suggest the existence of a coordinately regulated innate defense pathway requiring both lymphotoxins and IFN-αβ to protect the homeostasis of lymphoid tissue upon infection with a normally nonpathogenic herpesvirus.

Lymphotoxin-Dependent Cross-Talk Between B cells and Stromal Cells Promotes the IFN-αβ Response to MCMV

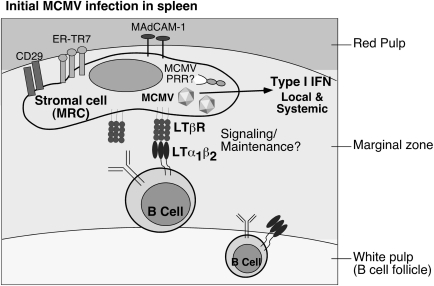

Results with bone marrow chimeric mice suggested that the MCMV-infected, IFN-αβ–producing splenic stromal cells must express the LTβR themselves (Fig. 2) (Schneider and others 2008). Therefore, if the stroma must express the LTβR, what cell type provides the LTαβ? LTαβ can be expressed by both naive and activated B and T lymphocytes, suggesting either cell type could be responsible. Accordingly, mice lacking all B cells display a dramatic deficiency in the initial IFN-αβ response to MCMV, whereas mice lacking T cells are normal (Schneider and others 2008). Further, conditional knockout mice lacking ltβ expression specifically in either B or T cells confirmed that it is LTβ-expressing B cells that communicate with the LTβR-expressing MRCs to promote the initial type I IFN response in the spleen (Schneider and others 2008).

FIG. 2.

LTαβ-expressing B cells cross-talk with splenic stromal cells to promote initial type I IFN production during MCMV infection. Upon entry into the spleen, MCMV first infects ERTR-7+ MAdCAM-1+ CD29+ marginal zone reticular cells (MRCs), and these stromal cells are the likely source of the majority of type I IFN produced locally and detected systemically during initial infection. B cells that constitutively express surface LTαβ provide a required signal to LTβR-expressing stromal cells to induce type I IFN. The pattern recognition receptor (PRR) detecting MCMV in the stroma is currently unknown.

Organ-Specific Regulation of IFN-αβ Production by Lymphotoxin Signaling

Although cross-talk between B cells and stroma via the LTαβ-LTβR pathway is crucial for initial IFN-αβ production in the spleen during MCMV infection, initial type I IFN production in the liver is not dependent upon LTβR signaling (Schneider and others 2008). The mechanism promoting initial IFN-αβ production in liver is currently unknown, but liver sinusoidal endothelial cells and hepatocytes are primary targets of initial MCMV infection in this organ (Sacher and others 2008). Although both these cell types can express LTβR, perhaps the absence of a significant, resident B-cell population in the liver excludes the role of this axis during initial MCMV infection. Interestingly, the relative amount of IFN-αβ produced by the liver compared with the spleen is significantly lower when normalized to MCMV gene expression (Schneider and others 2008), suggesting that splenic MZ stromal cells are robust producers of IFN-αβ on a per cell basis when encountering this virus. Additionally, as mice deficient in LTβR signaling show normal initial levels of IFN-αβ production in the liver but show major defects in the serum, this strongly suggests that the spleen is a major contributing organ to systemic IFN-αβ levels during MCMV infection.

LTβR Signaling Pathways That Regulate the Stromal IFN-αβ Response

Upon binding of the LTβR by LTαβ or LIGHT, the TNFR-associated factors (TRAFs) function as cytoplasmic signaling adaptors (Fig. 1) (Nakano and others 1996; VanArsdale and others 1997). Activation of the noncanonical NFκB pathway occurs after recruitment of TRAF2 and TRAF3 to the LTβR upon ligand binding, competitively displacing the NFκB-inducing kinase (NIK) from these TRAFs, which constitutively degrade NIK via their E3 ubiquitin ligase activity in unactivated cells (Sanjo and others 2010), ultimately resulting in activation of IKKα and RelB-dependent transcription (Dejardin and others 2002). Mice with a naturally occurring mutation in NIK (aly/aly) also show a severe defect in the MCMV-induced initial IFN-αβ response (Schneider and others 2008), indicating that the LTβR-NIK signaling pathway operates in MZ stromal cells to modulate innate defenses.

Mice lacking Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling (MyD88/TRIF deficient) mount a normal initial IFN-αβ response to MCMV infection, distinguishing the LTβR from TLR-dependent pathways in regulating MCMV defenses in MZ stromal cells (Schneider and others 2008). The TLR-independent pathways that regulate innate sensing of DNA viruses are not as well defined as they are for RNA viruses; however, significant recent advances have been made (Pichlmair and Reis e Sousa 2007; Tamura and others 2008; Takeuchi and Akira 2009). The DNA-dependent activator of interferon response factors (IRFs) (DAI/DLM-1/ZBP1) senses dsDNA in the cytoplasm (Takaoka and others 2007). Dependent activator of IRF (DAI) can bind the receptor-interacting protein (RIP) 1 and RIP3 through its RIP homotypic interacting motif (Kaiser and others 2008; Rebsamen and others 2009) and transmit downstream signals through Cardif (IPS-1/MAVS/VISA) and/or the stimulator of IFN genes/mediator of IRF3 activation to activate IFN-β transcription (Ishikawa and Barber 2008; Takeuchi and Akira 2008; Yanai and others 2009). Although the sensor/pathway regulating innate recognition of MCMV remains unidentified, a recent report identifies DAI as necessary and sufficient for IRF3 activation and IFN-β production during HCMV infection of cultured fibroblasts (DeFilippis and others 2010). As IRF3 and NFκB are both essential components of the IFN-β-enhancesome (Thanos and Maniatis 1995), it is enticing to speculate that LTβR regulation of type I IFN production may synergize with a DAI-dependent (or DAI-like) pathway in some cell types.

How the Lessons Learned from Studying LTαβ-LTβR Regulation of Innate Defense to CMV May Extend to Other Systems

Stromal cells are major producers of IFN-αβ during MCMV infection, but do they contribute in other contexts? Recent studies with the ssRNA Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) identified the stroma as producing IFN-αβ during infection (Schilte and others 2010). Similar to several other RNA viruses, a Cardif-dependent recognition pathway is operable in fibroblasts, but whether LTαβ-dependent signals contribute to CHIKV innate defenses remains to be determined. Recent work has also shown that splenic stromal cells regulate the effectiveness of DC-targeted vaccines (Longhi and others 2009). The adjuvant activity of poly-IC in this system was ascribed primarily to its induction of type I IFN in vivo. Similar to studies with MCMV and CHIKV, a bone marrow reconstitution approach revealed radioresistant stromal cells to be the major MDA5-dependent producers of IFN-αβ after poly-IC injection, which then functioned to mature vaccine antigen-targeted, DEC-205+ DC and promote the adaptive response.

As a flip side to the protective role of LTαβ-LTβR signaling in promoting antiviral innate defenses, deregulated and/or extended activation of this pathway has recently been shown to promote tumorigenesis. In the case of hepatitis B and C virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma, infiltration of LTαβ-expressing lymphocytes can signal to LTβR-expressing hepatocytes to drive chronic hepatitis and liver cancer (Haybaeck and others 2009). In turn, expression of LTαβ by tumor-resident B cells drives the pathogenesis associated with castration-resistant prostate cancer (Ammirante and others 2010). In both these mouse tumor models, treatment with LTβR-Fc (a pharmacological blocker of LTαβ and LIGHT signaling) restricted tumor progression. Additionally, activation of both the canonical and noncanonical NFκB pathways downstream of LTβR activation was implicated in tumorigenesis. Consequently, these cases serve as another example that tight regulation of LTαβ-LTβR signaling is critical for maintaining immune homeostasis and that chronic signaling during prolonged inflammation can disrupt this equilibrium and promote disease.

Conclusions

Although we have mainly discussed the host mechanisms regulating CMV induction of IFN-αβ, CMV dampens both IFN-αβ induction and downstream signaling at various levels, and this has been recently reviewed (DeFilippis 2007; Lenac and others 2008; Marshall and Geballe 2009). It is critical to consider this fact when formulating any models regarding the functional consequences of IFN-αβ signaling on the course of CMV infection. Additionally, the direct regulation of innate defenses by the LTαβ-LTβR signaling pathway is almost certainly intertwined with its role in maintaining lymphoid tissue architecture. CMV selectively disrupts this architecture upon acute infection, but LTβR-dependent signaling contributes to its rapid restoration (Benedict and others 2006), highlighting a key difference between CMV and nonpersistent viruses, which disrupt tissue architecture for much longer periods of time (Mueller and others 2007; Scandella and others 2008). These concepts, in addition to the role that B cells can play in regulating innate antiviral defenses, will continue to be active areas of research that bridge diverse fields.

Acknowledgments

The authors apologize to their colleagues whose work was not referenced because of limited space. This work was supported by NIH grants AI076864 and AI069298 to C.A.B.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Ammirante M. Luo JL. Grivennikov S. Nedospasov S. Karin M. B-cell-derived lymphotoxin promotes castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nature. 2010;464(7286):302–305. doi: 10.1038/nature08782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks TA. Rickert S. Benedict CA. Ma L. Ko M. Meier J. Ha W. Schneider K. Granger SW. Turovskaya O. Elewaut D. Otero D. French AR. Henry SC. Hamilton JD. Scheu S. Pfeffer K. Ware CF. A lymphotoxin-IFN-beta axis essential for lymphocyte survival revealed during cytomegalovirus infection. J Immunol. 2005;174(11):7217–7225. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict CA. Banks TA. Senderowicz L. Ko M. Britt WJ. Angulo A. Ghazal P. Ware CF. Lymphotoxins and cytomegalovirus cooperatively induce interferon-beta, establishing host-virus detente. Immunity. 2001;15(4):617–626. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00222-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict CA. De Trez C. Schneider K. Ha S. Patterson G. Ware CF. Specific remodeling of splenic architecture by cytomegalovirus. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2(3):e16. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler B. Georgel P. Rutschmann S. Jiang Z. Croker B. Crozat K. Genetic analysis of innate resistance to mouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV) Brief Funct Genomic Proteomic. 2005;4(3):203–213. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/4.3.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne EP. Wing B. Coleman D. Shenk T. Altered cellular mRNA levels in human cytomegalovirus-infected fibroblasts: viral block to the accumulation of antiviral mRNAs. J Virol. 2001;75:12319–12330. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.24.12319-12330.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong KT. Gresser I. Mims CA. Interferon as a defence mechanism in mouse cytomegalovirus infection. J Gen Virol. 1983;64(Pt 2):461–464. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-64-2-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalod M. Hamilton T. Salomon R. Salazar-Mather TP. Henry SC. Hamilton JD. Biron CA. Dendritic cell responses to early murine cytomegalovirus infection: subset functional specialization and differential regulation by interferon alpha/beta. J Exp Med. 2003;197(7):885–898. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalod M. Salazar-Mather TP. Malmgaard L. Lewis C. Asselin-Paturel C. Briere F. Trinchieri G. Biron CA. Interferon alpha/beta and interleukin 12 responses to viral infections: pathways regulating dendritic cell cytokine expression in vivo. J Exp Med. 2002;195(4):517–528. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFilippis VR. Induction and evasion of the type I interferon response by cytomegaloviruses. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;598:309–324. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-71767-8_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFilippis VR. Alvarado D. Sali T. Rothenburg S. Fruh K. Human cytomegalovirus induces the interferon response via the DNA sensor ZBP1. J Virol. 2010;84(1):585–598. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01748-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejardin E. Droin NM. Delhase M. Haas E. Cao Y. Makris C. Li ZW. Karin M. Ware CF. Green DR. The lymphotoxin-beta receptor induces different patterns of gene expression via two NF-kappaB pathways. Immunity. 2002;17(4):525–535. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettinger R. Browning JL. Michie SA. van Ewijk W. McDevitt HO. Disrupted splenic architecture, but normal lymph node development in mice expressing a soluble lymphotoxin-b receptor-IgG1 fusion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13102–13107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher AL. Lukacs-Kornek V. Reynoso ED. Pinner SE. Bellemare-Pelletier A. Curry MS. Collier AR. Boyd RL. Turley SJ. Lymph node fibroblastic reticular cells directly present peripheral tissue antigen under steady-state and inflammatory conditions. J Exp Med. 2010;207(4):689–697. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy JE. Trapman J. Allan JE. Shellam GR. Melief CJ. Evidence for a protective role of interferon in resistance to murine cytomegalovirus and its control by non-H-2-linked genes. Infect Immun. 1982;37(1):143–150. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.1.143-150.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haybaeck J. Zeller N. Wolf MJ. Weber A. Wagner U. Kurrer MO. Bremer J. Iezzi G. Graf R. Clavien PA. Thimme R. Blum H. Nedospasov SA. Zatloukal K. Ramzan M. Ciesek S. Pietschmann T. Marche PN. Karin M. Kopf M. Browning JL. Aguzzi A. Heikenwalder M. A lymphotoxin-driven pathway to hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2009;16(4):295–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu KM. Pratt JR. Akers WJ. Achilefu SI. Yokoyama WM. Murine cytomegalovirus displays selective infection of cells within hours after systemic administration. J Gen Virol. 2009;90(Pt 1):33–43. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.006668-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa H. Barber GN. STING is an endoplasmic reticulum adaptor that facilitates innate immune signalling. Nature. 2008;455(7213):674–678. doi: 10.1038/nature07317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen AC. Norris PS. Ware CF. Benedict CA. Human NK cells inhibit cytomegalovirus replication through a noncytolytic mechanism involving lymphotoxin-dependent induction of IFN-beta. J Immunol. 2005;175(11):7568–7574. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis MA. Borton JA. Keech AM. Wong J. Britt WJ. Magun BE. Nelson JA. Human cytomegalovirus attenuates interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor alpha proinflammatory signaling by inhibition of NF-kappaB activation. J Virol. 2006;80(11):5588–5598. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00060-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser WJ. Upton JW. Mocarski ES. Receptor-interacting protein homotypic interaction motif-dependent control of NF-kappa B activation via the DNA-dependent activator of IFN regulatory factors. J Immunol. 2008;181(9):6427–6434. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katakai T. Hara T. Sugai M. Gonda H. Shimizu A. Lymph node fibroblastic reticular cells construct the stromal reticulum via contact with lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 2004;200(6):783–795. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern ER. Pivotal role of animal models in the development of new therapies for cytomegalovirus infections. Antiviral Res. 2006;71(2–3):164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern ER. Olsen GA. Overall JC., Jr. Glasgow LA. Treatment of a murine cytomegalovirus infection with exogenous interferon, polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid, and polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid-poly-L-lysine complex. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1978;13(2):344–346. doi: 10.1128/aac.13.2.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraal G. Mebius R. New insights into the cell biology of the marginal zone of the spleen. Int Rev Cytol. 2006;250:175–215. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(06)50005-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenac T. Arapovic J. Traven L. Krmpotic A. Jonjic S. Murine cytomegalovirus regulation of NKG2D ligands. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2008;197(2):159–166. doi: 10.1007/s00430-008-0080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link A. Vogt TK. Favre S. Britschgi MR. Acha-Orbea H. Hinz B. Cyster JG. Luther SA. Fibroblastic reticular cells in lymph nodes regulate the homeostasis of naive T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(11):1255–1265. doi: 10.1038/ni1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewendorf A. Benedict CA. Modulation of host innate and adaptive immune defenses by cytomegalovirus: timing is everything. J Intern Med. 2010;267:483–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longhi MP. Trumpfheller C. Idoyaga J. Caskey M. Matos I. Kluger C. Salazar AM. Colonna M. Steinman RM. Dendritic cells require a systemic type I interferon response to mature and induce CD4+ Th1 immunity with poly IC as adjuvant. J Exp Med. 2009;206(7):1589–1602. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay F. Majeau GR. Lawton P. Hochman PS. Browning JL. Lymphotoxin but not tumor necrosis factor functions to maintain splenic architecture and humoral responsiveness in adult mice. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27(8):2033–2042. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis T. Falvo JV. Kim TH. Kim TK. Lin CH. Parekh BS. Wathelet MG. Structure and function of the interferon-beta enhanceosome. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1998;63:609–620. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1998.63.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall EE. Geballe AP. Multifaceted evasion of the interferon response by cytomegalovirus. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009;29(9):609–619. doi: 10.1089/jir.2009.0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mebius RE. Kraal G. Structure and function of the spleen. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(8):606–616. doi: 10.1038/nri1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer JA. Wiley CA. Spector DH. Pathogenesis of murine cytomegalovirus infection: identification of infected cells in the spleen during acute and latent infections. J Virol. 1988;62:987–997. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.3.987-997.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller SN. Germain RN. Stromal cell contributions to the homeostasis and functionality of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(9):618–629. doi: 10.1038/nri2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller SN. Hosiawa-Meagher KA. Konieczny BT. Sullivan BM. Bachmann MF. Locksley RM. Ahmed R. Matloubian M. Regulation of homeostatic chemokine expression and cell trafficking during immune responses. Science. 2007;317(5838):670–674. doi: 10.1126/science.1144830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano H. Oshima H. Chung W. Williams-Abbott L. Ware C. Yagita H. Okumura K. TRAF5, an activator of NF-kB and putative signal transducer for the lymphotoxin-b receptor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14661–14664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.14661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen KB. Salazar-Mather TP. Dalod MY. Van Deusen JB. Wei XQ. Liew FY. Caligiuri MA. Durbin JE. Biron CA. Coordinated and distinct roles for IFN-alpha beta, IL-12, and IL-15 regulation of NK cell responses to viral infection. J Immunol. 2002;169(8):4279–4287. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orange JS. Biron CA. Characterization of early IL-12, IFN-alpha beta, and TNF effects on antiviral state and NK cell responses during murine cytomegalovirus infection. J Immunol. 1996;156(12):4746–4756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orange JS. Wang B. Terhorst C. Biron CA. Requirement for natural killer cell-produced interferon gamma in defense against murine cytomegalovirus infection and enhancement of this defense pathway by interleukin 12 administration. J Exp Med. 1995;182(4):1045–1056. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.4.1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn JE. Medearis DN., Jr. Studies of relationship between mouse cytomegalovirus and interferon. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1966;121(3):819–824. doi: 10.3181/00379727-121-30897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira L. Maidji E. McDonagh S. Tabata T. Insights into viral transmission at the uterine-placental interface. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13(4):164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichlmair A. Reis e Sousa C. Innate recognition of viruses. Immunity. 2007;27(3):370–383. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers C. Fruh K. Rhesus CMV: an emerging animal model for human CMV. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2008;197(2):109–115. doi: 10.1007/s00430-007-0073-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall TD. Carragher DM. Rangel-Moreno J. Development of secondary lymphoid organs. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:627–650. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebsamen M. Heinz LX. Meylan E. Michallet MC. Schroder K. Hofmann K. Vazquez J. Benedict CA. Tschopp J. DAI/ZBP1 recruits RIP1 and RIP3 through RIP homotypic interaction motifs to activate NF-kappaB. EMBO Rep. 2009;10(8):916–922. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacher T. Podlech J. Mohr CA. Jordan S. Ruzsics Z. Reddehase MJ. Koszinowski UH. The major virus-producing cell type during murine cytomegalovirus infection, the hepatocyte, is not the source of virus dissemination in the host. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3(4):263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanjo H. Zajonc DM. Braden R. Norris PS. Ware CF. Allosteric regulation of the ubiquitin:NIK and ubiquitin:TRAF3 E3 ligases by the lymphotoxin-beta receptor. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(22):17148–17155. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.105874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalzo AA. Corbett AJ. Rawlinson WD. Scott GM. Degli-Esposti MA. The interplay between host and viral factors in shaping the outcome of cytomegalovirus infection. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85(1):46–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scandella E. Bolinger B. Lattmann E. Miller S. Favre S. Littman DR. Finke D. Luther SA. Junt T. Ludewig B. Restoration of lymphoid organ integrity through the interaction of lymphoid tissue-inducer cells with stroma of the T cell zone. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(6):667–675. doi: 10.1038/ni.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilte C. Couderc T. Chretien F. Sourisseau M. Gangneux N. Guivel-Benhassine F. Kraxner A. Tschopp J. Higgs S. Michault A. Arenzana-Seisdedos F. Colonna M. Peduto L. Schwartz O. Lecuit M. Albert ML. Type I IFN controls chikungunya virus via its action on nonhematopoietic cells. J Exp Med. 2010;207(2):429–442. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider K. Loewendorf A. De Trez C. Fulton J. Rhode A. Shumway H. Ha S. Patterson G. Pfeffer K. Nedospasov SA. Ware CF. Benedict CA. Lymphotoxin-mediated crosstalk between B cells and splenic stroma promotes the initial type I interferon response to cytomegalovirus. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3(2):67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staras SA. Dollard SC. Radford KW. Flanders WD. Pass RF. Cannon MJ. Seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus infection in the United States, 1988–1994. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(9):1143–1151. doi: 10.1086/508173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaoka A. Wang Z. Choi MK. Yanai H. Negishi H. Ban T. Lu Y. Miyagishi M. Kodama T. Honda K. Ohba Y. Taniguchi T. DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) is a cytosolic DNA sensor and an activator of innate immune response. Nature. 2007;448(7152):501–505. doi: 10.1038/nature06013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi O. Akira S. MDA5/RIG-I and virus recognition. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20(1):17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi O. Akira S. Innate immunity to virus infection. Immunol Rev. 2009;227(1):75–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00737.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura T. Yanai H. Savitsky D. Taniguchi T. The IRF family transcription factors in immunity and oncogenesis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:535–584. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RT. Bresnahan WA. Human cytomegalovirus immediate-early 2 gene expression blocks virus-induced beta interferon production. J Virol. 2005;79(6):3873–3877. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3873-3877.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RT. Bresnahan WA. Human cytomegalovirus immediate-early 2 protein IE86 blocks virus-induced chemokine expression. J Virol. 2006;80(2):920–928. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.920-928.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanos D. Maniatis T. Virus induction of human IFN beta gene expression requires the assembly of an enhanceosome. Cell. 1995;83(7):1091–1100. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomei AA. Siegert S. Britschgi MR. Luther SA. Swartz MA. Fluid flow regulates stromal cell organization and CCL21 expression in a tissue-engineered lymph node microenvironment. J Immunol. 2009;183(7):4273–4283. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumanov AV. Grivennikov SI. Shakhov AN. Rybtsov SA. Koroleva EP. Takeda J. Nedospasov SA. Kuprash DV. Dissecting the role of lymphotoxin in lymphoid organs by conditional targeting. Immunol Rev. 2003a;195:106–116. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumanov AV. Kuprash DV. Nedospasov SA. The role of lymphotoxin in development and maintenance of secondary lymphoid tissues. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003b;14(3–4):275–288. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(03)00026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyznik AJ. Tupin E. Nagarajan NA. Her MJ. Benedict CA. Kronenberg M. Cutting edge: the mechanism of invariant NKT cell responses to viral danger signals. J Immunol. 2008;181(7):4452–4456. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanArsdale TL. VanArsdale SL. Force WR. Walter BN. Mosialos G. Kieff E. Reed JC. Ware CF. Lymphotoxin-b receptor signaling complex: role of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 3 recruitment in cell death and activation of nuclear factor kB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2460–2465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varani S. Frascaroli G. Landini MP. Soderberg-Naucler C. Human cytomegalovirus targets different subsets of antigen-presenting cells with pathological consequences for host immunity: implications for immunosuppression, chronic inflammation and autoimmunity. Rev Med Virol. 2009;19(3):131–145. doi: 10.1002/rmv.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware CF. NETWORK COMMUNICATIONS: Lymphotoxins, LIGHT, and TNF. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:787–819. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesley JD. Tessmer MS. Chaukos D. Brossay L. NK cell-like behavior of Valpha14i NK T cells during MCMV infection. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(7):e1000106. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanai H. Savitsky D. Tamura T. Taniguchi T. Regulation of the cytosolic DNA-sensing system in innate immunity: a current view. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21(1):17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zindl CL. Kim TH. Zeng M. Archambault AS. Grayson MH. Choi K. Schreiber RD. Chaplin DD. The lymphotoxin LTalpha(1)beta(2) controls postnatal and adult spleen marginal sinus vascular structure and function. Immunity. 2009;30(3):408–420. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]