Abstract

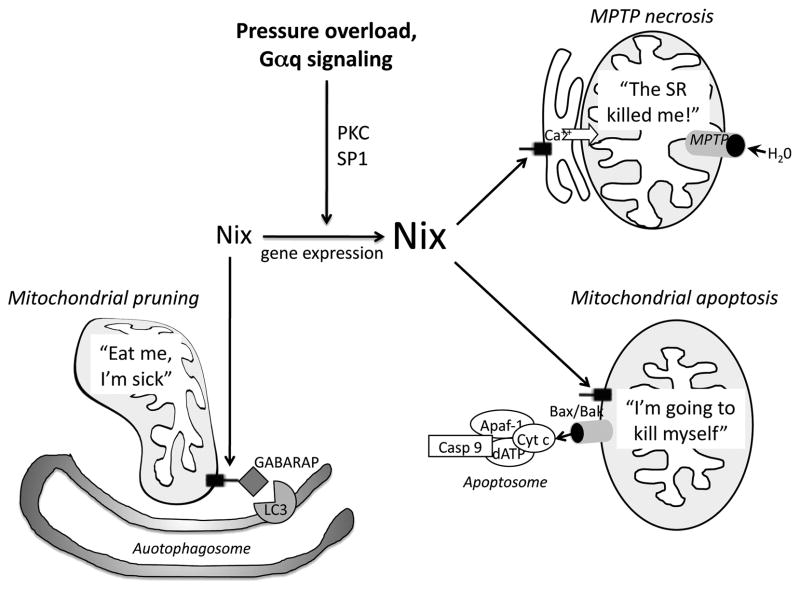

Nix was first described in the heart as the protein product of a differentially expressed mRNA detected by hybridiztion to a partial cDNA sequence tag on an RNA expression array. Over the subsequent 8 years Nix has become the prototypical transcriptionally-regulated cardiac myocyte “suicide” gene and has been used as a model to interrogate mechanisms of programmed cardiomyocyte death in hypertrophy and heart failure. Nix stimulates conventional apoptosis mediated via the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway, but emerging evidence indicates that Nix also controls programmed necrosis dependent upon sarcoplasmic reticular-mitochondrial tethering, calcium cross-talk, and the mitochondrial permeability transition. Recent studies have also described Nix labeling of senescent cardiomyocyte mitochondria for autophagic elimination, elucidated a physiological mitochondrial quality control Nix function; so-called “mitochondrial pruning.

Keywords: apoptosis, programmed necrosis, autophagy, heart failure, BNip3 proteins, necrosis, mitochondrial autophagy

Introduction

In English Fairy Tales (1890) [1] Nix Nought Nothing is the tale of a prince given that name until his absent father (the King) could be present for his christening. Because his father was gone for a very long time the odd name stuck and the resulting confusion over Nix the word and Nix the man led to many misadventures involving a giant, his lovely daughter, and many magic spells (the complete original text is public domain and available at http://www.surlalunefairytales.com/authors/jacobs/english/nixnought.html). Similar confusion currently surrounds Nix, the molecule. After its original description [2], the function and mechanism of action of Nix, promoting apoptosis via the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway, seemed straightforward and essentially identical to other “pro-apoptotic” Bcl2 factors. However, recent data indicate that Nix localizes not only to mitochondria, but also to endoplasmic reticulum (sarcoplasmic reticulum in cardiac myocytes), and that it stimulates programmed cell elimination through at least three mechanistically distinct pathways, caspase-mediated apoptosis, necrosis mediated via the mitochondrial permeability transition, and autophagy.

Nix is transcriptionally upregulated in pathological cardiac hypertrophy, where it induces programmed cardiac myocyte death that is an important determinant of progression from compensated hypertrophy to dilated cardiomyopathy. Regulation of Nix by the same factors that induce cardiac hypertrophy, and its location at the apex of multiple distinct cardiomyocyte death signaling pathways, position it (and related cardiac-expressed BNip3) as an important sensor/effector of various forms of pathological cardiac stress. Here, the factors that regulate Nix in the heart, the consequences of its regulated expression, and the potential for targeting Nix in cardiac disease, are briefly reviewed in the context of new, unexpected developments.

Regulation of Nix expression

Nix transcripts are detected at low levels in most tissues, but it is constitutively expressed at higher levels in the heart, liver and kidney [3]. In myocardium, Nix is transcriptionally upregulated during development of pressure overload and Gαq-dependent hypertrophy via a mechanism dependent upon protein kinase C activation of transcription factor SP-1, which binds to GC boxes within the Nix promoter [3] (Figure). Importantly, cardiomyocyte Nix is not upregulated by hypoxia, whereas Nix is transcriptionally increased via a mechanism involving hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) in some tumor cells [4, 5]. These tissue-specific differences in Nix regulation have important implications: In hearts, hypertrophy-, but not hypoxia-mediated regulation of Nix provides for stimulus-specific cardiomyocyte death responses. Indeed, the related BH3-only like factor BNip3 is upregulated by hypoxia in cardiac myocytes, providing for separate, but functionally similar, programmed cardiomyocyte death responses in hearts undergoing chronic hemodynamic stress (Nix in hypertrophy) versus acute myocardial infarction (BNip3 in ischemia). In tissues wherein Nix is hypoxia-responsive, it may function as a tumor suppressor. Consistent with this role, transcriptional suppression of Nix due to hypermethylation of critical promoter regions is associated with lung, liver, and prostate cancers [6–8], and Nix mutations are found in breast and ovarian cancer [9]. The mechanism for Nix upregulation by hypoxia is proposed to involve HIF-1 recruitment of CREB-binding protein and tumor-suppressor p53 [10].

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of different Nix functions as described in the text.

The major mechanisms increasing Nix expression/activity are transcriptional. However, for any potent death factor the “on switch” needs to be coupled to a rapid “off switch”. For Nix and related BNip3 factors this is ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation determined by PEST sequences in their amino terminal domains [2, 11].

Nix can induce pathological programmed cell death (see below), but its presence at measurable levels in certain tissues suggests that it can play important physiological roles as well. In some instances, these functions have been delineated. For example, Nix is upregulated during erythroblast development in concert with anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL [12]. Nix gene ablation increases erythroblast development in vitro and in vivo, resulting in strikingly increased reticulocyte counts in the context of normal hematocrit, i.e. an imbalance favoring erythroblast survival over programmed elimination [13]. However, the erythrocytes (red blood cells) of Nix null mice are abnormally fragile, revealing that the maturational expression of Nix during erythropoiesis regulates erythroblast quantity and quality [14, 15].

Nix and cardiomyopathy: insights from cardiac gain- and loss-of-Nix function mice

As discussed below, the reason a programmed death protein like Nix is constitutively expressed in cardiac myocytes may relate to its essential role regulating mitochondrial quality and quantity through mito-autophagy [14, 16–18] (Figure). However, transcriptional upregulation of Nix in human and murine pressure overload hypertrophy is a pathological process that activates pathways leading to programmed elimination of cardiac myocytes and contributes to the transition from functionally compensated hypertrophy to dilated cardiomyopathy [19–21]. Both the normal/essential function of Nix and the pathological consequences of its upregulation have been delineated in studies that combine gain- and loss-of function in cultured cells with mouse models in which Nix is specifically modulated in cardiac myocytes.

Our initial studies examining the cellular consequences of the Nix upregulation used transient Nix expression in HEK293 cells. We observed Nix localizing primarily to mitochondria where it stimulated cytochrome c release that activated the mitochondrial pathway of caspase-dependent apoptosis [19]. In contrast, a naturally-occurring murine Nix splice variant lacking the carboxyl terminus hydrophobic domain (sNix) did not localize to mitochondria, activate caspases or induce cell death. These findings linked Nix mitochondrial localization to its programmed death response. Assuming that mitochondrial apoptosis signaling completely explained cell death (which later turned out to be only partially correct, see below), we used standard MYH6-directed transgenesis to overexpress Nix in mouse hearts beginning shortly after birth. Nix transgenic mice were born apparently normal, but developed a rapidly progressive dilated cardiomyopathy that was uniformly lethal on the 7th to 10th day of life (depending upon Nix expression level). TUNEL staining was positive in 15–20% of cardiac myocytes, implicating massive programmed cardiac myocyte death in this form of heart failure. In a subsequent study, we conditionally expressed Nix using a tetracycline-suppressible double MYH6–driven transgenic system, permitting us to determine that cell death induced by Nix was much greater under conditions where cardiac myocyte growth was being stimulated, i.e. in the actively growing post-natal heart and after induction of pressure overload by transverse aortic banding [20]. The latter finding showed that Nix coordinates intrinsic transcriptional cues and external trophic stimuli when inducing programmed cardiac myocyte death, and helps to explain how normal hearts tolerate low levels of constitutive Nix expression.

Based upon our observations that Nix is transcriptionally upregulated in Gαq-dependent hypertrophy and is sufficient to induce cardiac myocyte death leading to dilated cardiomyopathy, we hypothesized that increased Nix might be the mechanism of apoptotic decompensation in the peripartum cardiomyopathy that characterizes Gαq transgenic mice [22, 23]. To test this notion, we created germ-line Nix knockout mice (Nix KO), crossed them to Gαq transgenic mice, and compared the incidence and severity of peripartum cardiomyopathy in Gαq/Nix KO versus Gαq mice. Nix ablation improved survival and cardiac function and decreased myocardial TUNEL positivity, “rescuing” the Gαq mice from peripartum cardiomyopathy [21]. Although these data support a role for Nix in cardiomyocyte apoptosis induced by Gαq, the Nix knockout experiment had two limitations: First, the Gαq peripartum model has no known naturally-occurring human analog, and so its relevance to human disease is uncertain. Second, Nix was ablated in the germ line (i.e. in all tissues), and so its protective effects did not necessarily derive from direct actions on cardiac myocytes. To address these deficiencies, we performed an additional experiment examining the consequences of cardiac-specific Nix ablation (Nix flox/flox x Nkx2.5 Cre; cardiac Nix KO) on the response to cardiac pressure overload. Cardiomyocyte TUNEL labeling, ventricular remodeling, and heart function were determined weekly for two months following surgical transverse aortic banding. Compared to normal controls, cardiac Nix KO mice exhibited half the rate of cardiomyocyte TUNEL positivity and myocardial fibrosis and did not undergo the typical adverse ventricular remodeling seen after pressure overloading [21]. Thus, rescue of hypertrophy decompensation by Nix ablation is cardiomyocyte autonomous. Together, these results established Nix as an important stress-inducible factor mediating programmed death of hypertrophied cardiac myocytes, and demonstrated a causal role for Nix-mediated cardiomyocyte death in adverse ventricular remodeling of hypertrophied hearts.

Mechanistic studies of Nix-mediated programmed cardiomyocyte death

Like all “pro-apoptotic” Bcl2 family members, Nix interacts with Bax and Bak to permeabilize mitochondrial outer membranes, releasing cytochrome c into the cytosol where it interacts with other members of the apoptosome to initiate the caspase cascade leading to oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation and protein degradation, i.e. intrinsic pathway apoptosis (Figure). Several years ago we observed that, like some other Bcl2 family proteins, a fraction of Nix (estimated at ~15% of total Nix protein) localized not to mitochondria, but to endoplasmic reticulum, or in cardiac myocytes, sarcoplasmic reticulum [24]. In studies performed in collaboration with Litsa Kranias, we used our conditional Nix transgenic and knockout mice to determine that Nix overexpression increased cardiac myocyte SR calcium content by ~20%, whereas Nix gene ablation decreased SR calcium content by ~20%. Calcium cycling was not affected by Nix, suggesting that its calcium regulatory role was not coupled to cardiomyocyte contraction. We therefore hypothesized that increased SR calcium might be playing a role in Nix-mediated cell death. This notion was tested using genetic complementation (phospholamban [PLN] ablation) to restore normal SR calcium levels in Nix knockout mice. We were then able to compare the Gαq peripartum cardiomyopathy rescue by Nix knockout mice with normal SR calcium stores (Nix/PLN double null) versus Nix knockout mice with diminished SR calcium stores (Nix KO). Stunningly, normalization of SR calcium stores by phospholamban ablation substantially neutralized the protective effects of Nix ablation, linking SR calcium to cardiomyocyte death induced by Nix [24]. Since calcium does not have a significant role in intrinsic pathway apoptosis, this finding pointed to a second, non-apoptotic, form of cell death stimulated by reticular-localized Nix.

Nix has long been recognized to induce cell death with features of both apoptosis and necrosis [25]. Paralleling the confusion over the form of programmed cell death are inconsistencies regarding the mechanism. In particular, reports in the literature stating that Nix opens mitochondrial permeability transition pores (MPTP) and dissipates the critical inner membrane electrochemical gradient, Δψm, required for oxidative phosphorylation and ATP production are at odds with its purported apoptotic function to facilitate Bax/Bak-dependent mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization, which spares Δψm (and indeed requires cellular ATP to drive energy-consuming apoptotic processes [26–28]). Some of the central papers reporting MPTP opening by Nix mistakenly cited our own work, which does not indicate that this is a direct effect of Nix, to justify this claim [16] We noted that the reports of Nix opening MPTP were all performed in intact cells, whereas our own demonstration that purified Nix protein does not open MPTP used isolated mitochondria [13], and realized that all the experimental data could be reconciled if Nix was interacting at reticular structures to indirectly activate the mitochondrial permeability transition by promoting reticular-mitochondrial calcium transport. We tested this notion in a pair of papers using mutant Nix proteins modified to localize exclusively to either mitochondria or to endoplasmic/sarcoplasmic reticulum. In cultured cells, mitochondrial- and reticular-directed Nix were equally lethal, and both induced standard markers of apoptosis (cytochrome c release, caspase activation, and TUNEL positivity). However, mitochondrial-specific Nix did not induce the mitochondrial permeability transition, whereas reticular-specific Nix opened mitochondrial permeability transition pores [24]. In other words, Nix that was directed only to mitochondria spared the mitochondrial inner membrane electrochemical gradient (and therefore ATP production), whereas Nix that was directed to reticular structures instead of mitochondria opened the MPTP, destroying mitochondrial ATP production. These results prove that reticular-mitochondrial cross-talk induced by ER/SR Nix opens MPTP, and reveal that Nix itself is not a direct MPTP activator.

We compared the apoptotic and MPTP (which we call programmed necrosis) mechanisms of cardiac myocyte death in the intact cardiovascular system by creating transgenic mice conditionally expressing the mitochondrial or reticular specific Nix mutants, and then assessing the consequences of “rescue” by genetically ablating MPTP function. As in cultured cells, both reticular and mitochondrial Nix induced programmed cardiac myocyte death resulting in a rapidly progressive cardiomyopathy [29]. However, only reticular-Nix was rescued by ablation of cyclophilin D, the critical functional protein of the MPTP. Wild-type Nix transgenic mice were partially rescued by cyclophilin D ablation [29]. Thus, both apoptosis and programmed necrosis are activated by Nix when it is upregulated in hearts, and both mechanisms contribute to cardiac decompensation (Figure).

Recent studies have suggested that Nix also has an essential, physiological function in the normal heart. Whereas cardiomyocyte-specific Nix gene ablation had no adverse effects on cardiac structure or function in young mice (and indeed protected against cardiomyocyte loss and progression to dilated cardiomyopathy after induction of hypertrophy, see above), cardiac Nix-null mice aged for ~1 year developed cardiac dilatation and contractile dysfunction associated with increased mitochondrial numbers and ultrastructural mitochondrial abnormalities [18]. Combined cardiac ablation of Nix and functionally homologous BNip3 accelerated and exaggerated the mitochondrial cardiomyopathy phenotype. These results suggest that Nix (and BNip3) identify and target dysfunctional or senescent cardiac myocyte mitochondria for autophagic elimination (Figure).

Recent studies have identified a specific mechanism by which Nix directs mitochondrial autophagy, recruitment of autophagosome membrane LC3/GABARAP proteins. Phage-display screening for binding partners of the autophagic protein GABARAP (γ-aminobutyric acid receptor-associated protein) identified Nix as a relatively low-affinity (Kd~100 μM) binding factor [30]. Mutational analysis of the putative Nix GABARAP binding site, amino acids 31–43 (at the opposite end of the Nix protein from the C-terminal mitochondrial targeting and transmembrane domains), uncovered a critical tryptophan (W36) that is essential for Nix-GABARAP binding. A simultaneous report identified the Nix-GABARAP interaction by yeast two-hybrid screen using the autophagy factor Atg8 as bait [31]. As in the first study, the Nix-GABARAP binding domain was localized to the amino terminus (resides 35–38) and required (murine) W35. Finally, Nix controls “mitochondrial priming” by the E3 ubiquitin ligase [32]. Thus, at a subcellular level, Nix induces mitochondrial pathway apoptosis, it helps destroy individual mitochondria by facilitating ER-mitochondrial calcium cross-talk and MPTP opening, and it designates mitochondria for targeted elimination by mito-autophagy (figuratively painting “Eat Me!” on them, Figure).

Therapeutic implications of Nix-mediated programmed cardiac myocyte death

A first glance of the data reviewed above suggests that Nix should be an attractive therapeutic target. It is transcriptionally upregulated in response to a specific pathological stimulus, hypertrophy. It is positioned at the apex of two parallel death pathways, both of which induce cardiomyocyte death in hypertrophied hearts. Thus it should be possible to “kill two cell death birds with the anti-Nix stone”. I think that this may prove to be quite challenging in human disease, however. Although hypertrophy leads to heart failure, and cardiomyocyte dropout plays a central role in this process, decompensation of human hypertrophy to dilated cardiomyopathy is a chronic process that occurs over years or decades. Thus, any future anti-Nix therapy would need to be implemented over prolonged periods of time. If such therapy were not cardiac-specific, then it would interrupt the essential Nix regulatory function controlling erythropoiesis, resulting in accelerated production of fragile red blood cells, i.e. chronic hemolysis with or without anemia. There is also the potential for systemic Nix suppression to stimulate cancer growth. On the other hand, if a cardiac-specific anti-Nix therapeutic were developed, and Nix expression were completely suppressed, then Nix would not be present to label senescent and dysfunctional mitochondria for mitophagy (the physiological “Eat Me” function), resulting in cardiomyopathy from accumulation of abnormal mitochondrial. Thus, although our laboratory has developed promising avenues of targeting Nix with small molecules (unpublished work), it is my impression that the clinical applications will be in syndromes other than heart failure; other means of preventing programmed cardiac myocyte death should prove beneficial in cardiac hypertrophy, ischemia, and heart failure.

Footnotes

Disclosures: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jacobs J. English Fairy Tales and More English Fairy Tales: ABC-CLIO; Reprint edition. Jun 19, 2002. p. 1890. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen G, Cizeau J, Vande VC, Park JH, Bozek G, Bolton J, et al. Nix and Nip3 form a subfamily of pro-apoptotic mitochondrial proteins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galvez AS, Brunskill EW, Marreez Y, Benner BJ, Regula KM, Kirshenbaum LA, et al. Distinct Pathways Regulate Proapoptotic Nix and BNip3 in Cardiac Stress. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1442–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509056200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruick RK. Expression of the gene encoding the proapoptotic Nip3 protein is induced by hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9082–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.9082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sowter HM, Ratcliffe PJ, Watson P, Greenberg AH, Harris AL. HIF-1-dependent regulation of hypoxic induction of the cell death factors BNIP3 and NIX in human tumors. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6669–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calvisi DF, Ladu S, Gorden A, Farina M, Lee JS, Conner EA, et al. Mechanistic and prognostic significance of aberrant methylation in the molecular pathogenesis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2713–22. doi: 10.1172/JCI31457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun JL, He XS, Yu YH, Chen ZC. Expression and structure of BNIP3L in lung cancer. Ai Zheng. 2004;23:8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu W, Xie CC, Zhu Y, Li T, Sun J, Cheng Y, et al. Homozygous deletions and recurrent amplifications implicate new genes involved in prostate cancer. Neoplasia. 2008;10:897–907. doi: 10.1593/neo.08428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai J, Flanagan J, Phillips WA, Chenevix-Trench G, Arnold J. Analysis of the candidate 8p21 tumour suppressor, BNIP3L, in breast and ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:270–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fei P, Wang W, Kim SH, Wang S, Burns TF, Sax JK, et al. Bnip3L is induced by p53 under hypoxia, and its knockdown promotes tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cizeau J, Ray R, Chen G, Gietz RD, Greenberg AH. The C. elegans orthologue ceBNIP3 interacts with CED-9 and CED-3 but kills through a BH3- and caspase-independent mechanism. Oncogene. 2000;19:5453–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aerbajinai W, Giattina M, Lee YT, Raffeld M, Miller JL. The proapoptotic factor Nix is coexpressed with Bcl-xL during terminal erythroid differentiation. Blood. 2003;102:712–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diwan A, Koesters AG, Odley AM, Pushkaran S, Baines CP, Spike BT, et al. Unrestrained erythroblast development in Nix−/− mice reveals a mechanism for apoptotic modulation of erythropoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6794–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610666104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schweers RL, Zhang J, Randall MS, Loyd MR, Li W, Dorsey FC, et al. NIX is required for programmed mitochondrial clearance during reticulocyte maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19500–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708818104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diwan A, Koesters AG, Capella D, Geiger H, Kalfa TA, Dorn GW., 2nd Targeting erythroblast-specific apoptosis in experimental anemia. Apoptosis. 2008;13:1022–30. doi: 10.1007/s10495-008-0236-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandoval H, Thiagarajan P, Dasgupta SK, Schumacher A, Prchal JT, Chen M, et al. Essential role for Nix in autophagic maturation of erythroid cells. Nature. 2008;454:232–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang J, Ney PA. NIX induces mitochondrial autophagy in reticulocytes. Autophagy. 2008;4:354–6. doi: 10.4161/auto.5552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dorn GW., 2nd Mitochondrial Pruning by Nix and BNip3: An Essential Function for Cardiac-Expressed Death Factors. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2010;3:374–83. doi: 10.1007/s12265-010-9174-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yussman MG, Toyokawa T, Odley A, Lynch RA, Wu G, Colbert MC, et al. Mitochondrial death protein Nix is induced in cardiac hypertrophy and triggers apoptotic cardiomyopathy. Nat Med. 2002;8:725–30. doi: 10.1038/nm719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Syed F, Odley A, Hahn HS, Brunskill EW, Lynch RA, Marreez Y, et al. Physiological growth synergizes with pathological genes in experimental cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2004;95:1200–6. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000150366.08972.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diwan A, Wansapura J, Syed FM, Matkovich SJ, Lorenz JN, Dorn GW., 2nd Nix-mediated apoptosis links myocardial fibrosis, cardiac remodeling, and hypertrophy decompensation. Circulation. 2008;117:396–404. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.727073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams JW, Sakata Y, Davis MG, Sah VP, Wang Y, Liggett SB, et al. Enhanced Galphaq signaling: a common pathway mediates cardiac hypertrophy and apoptotic heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10140–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayakawa Y, Chandra M, Miao W, Shirani J, Brown JH, Dorn GW, 2nd, et al. Inhibition of cardiac myocyte apoptosis improves cardiac function and abolishes mortality in the peripartum cardiomyopathy of Galpha(q) transgenic mice. Circulation. 2003;108:3036–41. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000101920.72665.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diwan A, Matkovich SJ, Yuan Q, Zhao W, Yatani A, Brown JH, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria crosstalk in NIX-mediated murine cell death. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:203–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI36445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vande VC, Cizeau J, Dubik D, Alimonti J, Brown T, Israels S, et al. BNIP3 and genetic control of necrosis-like cell death through the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5454–68. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.15.5454-5468.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li P, Nijhawan D, Budihardjo I, Srinivasula SM, Ahmad M, Alnemri ES, et al. Cytochrome c and dATP-dependent formation of Apaf-1/caspase-9 complex initiates an apoptotic protease cascade. Cell. 1997;91:479–89. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80434-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kass GE, Eriksson JE, Weis M, Orrenius S, Chow SC. Chromatin condensation during apoptosis requires ATP. Biochem J. 1996;318 (Pt 3):749–52. doi: 10.1042/bj3180749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eguchi Y, Shimizu S, Tsujimoto Y. Intracellular ATP levels determine cell death fate by apoptosis or necrosis. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1835–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Y, Lewis W, Diwan A, Cheng EH, Matkovich SJ, Dorn GW., 2nd Dual autonomous mitochondrial cell death pathways are activated by Nix/BNip3L and induce cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:9035–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914013107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwarten M, Mohrluder J, Ma P, Stoldt M, Thielmann Y, Stangler T, et al. Nix directly binds to GABARAP: a possible crosstalk between apoptosis and autophagy. Autophagy. 2009;5:690–8. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.5.8494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Novak I, Kirkin V, McEwan DG, Zhang J, Wild P, Rozenknop A, et al. Nix is a selective autophagy receptor for mitochondrial clearance. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:45–51. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ding WX, Ni HM, Li M, Liao Y, Chen X, Stolz DB, et al. Nix is critical to two distinct phases of mitophagy: reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated autophagy induction and Parkin-ubiqutin-p62-mediated mitochondria priming. J Biol Chem. 2010 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.119537. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]