Abstract

The hallmark clinical symptom of early Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is episodic memory impairment. Recent functional imaging studies suggest that memory function is subserved by a set of distributed networks, which include both the medial temporal lobe (MTL) system and the set of cortical regions collectively referred to as the default network. Specific regions of the default network, in particular, the posteromedial cortices, including the precuneus and posterior cingulate, are selectively vulnerable to early amyloid deposition in AD. These regions are also thought to play a key role in both memory encoding and retrieval, and are strongly functionally connected to the MTL. Multiple functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies during memory tasks have revealed alterations in these networks in patients with clinical AD. Similar functional abnormalities have been detected in subjects at-risk for AD, including those with genetic risk and older individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Recently, we and other groups have found evidence of functional alterations in these memory networks even among cognitively intact older individuals with occult amyloid pathology, detected by PET amyloid imaging. Taken together, these findings suggest that the pathophysiological process of AD exerts specific deleterious effects on these distributed memory circuits, even prior to clinical manifestations of significant memory impairment. Interestingly, some of the functional alterations seen in prodromal AD subjects have taken the form of increases in activity relative to baseline, rather than a loss of activity. It remains unclear whether these increases in fMRI activity may be compensatory to maintain memory performance in the setting of early AD pathology or instead, represent evidence of excitotoxicity and impending neuronal failure. Recent studies have also revealed disruption of the intrinsic connectivity of these networks observable even during the resting state in early AD and asymptomatic individuals with high amyloid burden. Research is ongoing to determine if these early network alterations will serve as sensitive predictors of clinical decline, and eventually, as markers of pharmacological response to potential disease-modifying treatments for AD.

Keywords: Functional magnetic resonance imaging, Amyloid, PiB, Alzheimer’s disease, Aging, Hippocampus, Default network

Introduction

Difficulty in the formation and retention of new episodic memories is typically the earliest and most salient clinical symptom of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Traditionally, the syndrome of memory impairment in AD has been attributed to neuronal loss in the perforant pathway of the medial temporal lobe (MTL) (Hyman et al. 1984). More recently, functional imaging studies have suggested that memory processes are subserved by a set of distributed, large-scale neural networks. In addition to the hippocampus and surrounding MTL cortices, these memory networks are comprised of a set of cortical regions—collectively known as the default network—which typically deactivate during memory encoding and other cognitively demanding tasks focused on processing of external stimuli (Raichle et al. 2001; Buckner et al. 2008). Fronto-parietal cortical networks, supporting executive function and attentional processes, also likely interact with these memory systems (Buckner 2004), and multiple cognitive domains become impaired as AD progresses. Converging evidence suggests that episodic memory, executive function, and other cognitive functions affected in AD, depend on the integrity and interplay of large-scale networks (Mesulam 1990, 1998), each consisting of specific nodes located in limbic archicortical, allocortical, and central “hubs” in heteromodal isocortical brain regions (Buckner et al. 2009).

Although the MTL is thought to be the site of early pathology (specifically neurofibrillary tangle pathology and neuronal loss) underlying the initial amnesic syndrome, pathologic alterations of AD are detectable in other limbic and heteromodal cortical regions (Tomlinson et al. 1970; Arnold et al. 1991; Braak and Braak 1991), and atrophy in these regions is detectable with sensitive structural imaging techniques in very mild stages and even prodromal stages of AD (Chetelat et al. 2005; Smith et al. 2007; Whitwell et al. 2007; Bakkour et al. 2008) (Jack et al. 2008). The nature of AD symptomatology, which eventually affects many aspects of cognitive function, in particular, complex cognitive processes such as attention, visuospatial orientation, and language in addition to memory, as well as the selective involvement of multiple cortical “convergence zones” (Arnold et al. 1991) have led to the conceptualization of AD syndrome as a disease of multiple large-scale neural networks (Seeley et al. 2009).

By the time AD dementia is diagnosed clinically, substantial neuronal loss and neuropathologic change have occurred in these networks. If we are to successfully intervene with disease-modifying therapy and slow the clinical progression of AD, we must develop sensitive markers that can detect early alterations in brain function, prior to irreversible neuronal damage (DeKosky and Marek 2003). Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has the potential to detect subtle functional abnormalities in the brain networks supporting the complex cognitive processes that become progressively impaired over the course of AD. Although fMRI is not as widely used as structural MRI or [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) in dementia research, the past few years have seen a rapid increase in the number of fMRI studies in prodromal and in clinical AD. In particular, fMRI may prove most valuable in elucidating the relationship between the pathophysiological process of AD and the earliest clinical manifestations. Despite the remarkable advances over the past two decades in our understanding of the biochemical alterations found in AD, we still lack a complete mechanistic explanation as to how these early pathological changes result in clinical symptomatology and, in particular, the salient impairment in episodic memory function. To gain further insight into the neural underpinnings of memory impairment, we must study individuals in relatively early stages of AD, prior to widespread neuronal loss and multi-domain cognitive impairment.

This article will review fMRI evidence of disrupted neural networks in early AD, in particular, the networks supporting memory function. We will first review fMRI studies along the trajectory of clinical AD, working backwards from clinical dementia to the prodromal stages of AD, including mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and ultimately to asymptomatic individuals at-risk for AD by virtue of genetic risk or advanced age with the presence of occult amyloid deposition. We will also explore the intriguing anatomic overlap between specific components of the memory networks located in heteromodal cortical regions and amyloid deposition, as measured by PET amyloid imaging with Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB). The predilection of amyloid deposition for heteromodal cortical hubs, in particular, seems to parallel loss of cognitive functions subserved by these large-scale networks. Finally, we will discuss the potential mechanistic underpinnings of the observed disruption in these networks, including the paradoxical findings of hyperactivity reported in specific nodes of these networks in early stages of prodromal AD.

fMRI Techniques: A Brief Introductory Review

Functional MRI provides non-invasive, in vivo methods to investigate the neural underpinnings of higher cognitive functions by means of measuring regional hemodynamic changes related to underlying cellular activity (Logothetis et al. 2001; Shmuel et al. 2006).

The functional MRI technique most widely used to identify cerebral activation is based on imaging of the endogenous blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) contrast (Ogawa et al. 1990) (Kwong et al. 1992). As FDG-PET is principally a measure of synaptic activity, BOLD fMRI is considered to reflect the integrated synaptic activity of neurons via MRI signal changes due to changes in blood flow, blood volume, and the blood oxyhemoglobin/deoxyhemoglobin ratio (Logothetis et al. 2001; Thompson et al. 2003; Sheth et al. 2004). In addition to observed increases in BOLD signal in activated brain areas, negative BOLD responses or “deactivations,” which are thought to represent decreases in neuronal activity below baseline levels of activity, may also be critical responses within these large-scale networks (Shmuel et al. 2006). Figure 1 demonstrates the pattern of activation and deactivation during an associative memory paradigm.

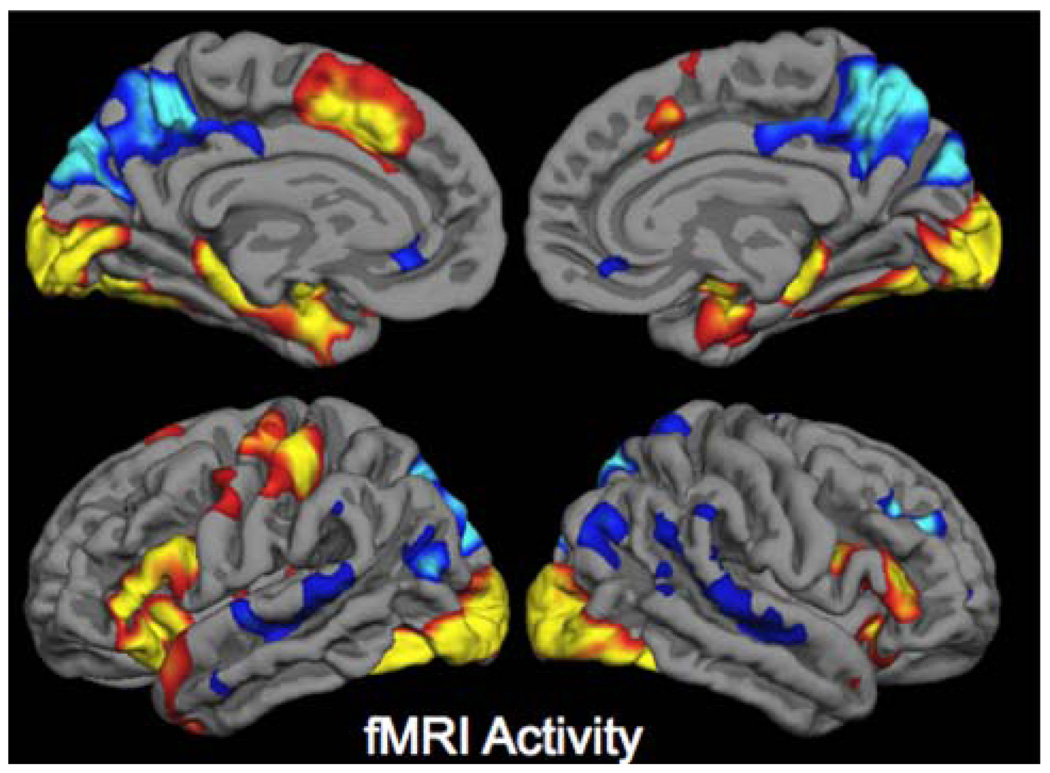

Fig. 1.

Cortical regions in which activity is increased during successful encoding of new items (activation) in prefrontal, medial, and inferior temporal regions, and in which activity is decreased during successful encoding of new items (deactivation) in the medial and lateral parietal regions. Increased and decreased activity is measured with respect to visual fixation. Regions shown in which task-induced deactivations are present represent key nodes within the default mode network (Sperling et al. 2009)

Typically, fMRI experiments compare the MR signal during one cognitive condition (e.g., memory encoding of novel stimuli) to a control task (e.g., viewing familiar stimuli) or to a passive baseline condition (e.g., visual fixation). This can be done in “block design” paradigms, in which stimuli of each cognitive condition are grouped together in blocks lasting 20–40 s, or in “event-related” paradigms, in which single stimuli from several different conditions are interspersed. The peak hemodynamic response is typically observed 4–6 s after the stimulus onset. Time courses of the task-induced positive and negative BOLD responses are similar and spatially these two types of responses are typically adjacent, though segregated from each others (Shmuel et al. 2006) (Fig. 2).

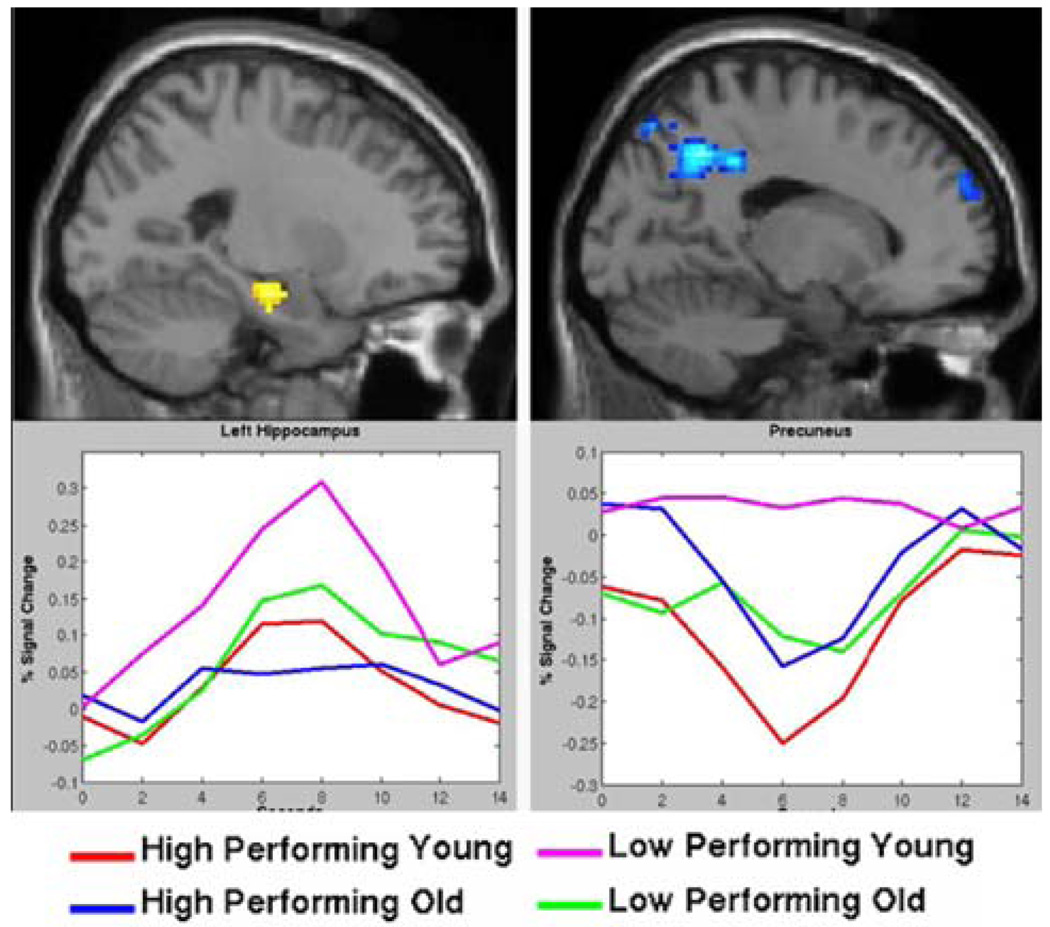

Fig. 2.

Both hippocampal activation (top left) and precuneus/posterior cingulate deactivation (top right) are associated with successful memory encoding in young subjects. Activity in these regions is altered in clinically normal older subjects who performed poorly on associative memory tasks. The bottom panels demonstrate MR signal time courses from these regions for four groups of subjects: low-performing elderly (pink), high-performing elderly (blue), low-performing young (green), and high-performing young (red). Low-performing elderly individuals (pink line in bottom graphs) fail to deactivate the precuneus/posterior cingulate (bottom right) during encoding, and demonstrate increased hippocampal (bottom left) and prefrontal activation for successful but not failed encoding trials. This hippocampal hyperactivity may represent a compensatory response to failure of default network activity (Miller et al. 2008b). (Color figure online)

The BOLD fMRI signal, and neurovascular coupling linking cellular activity to hemodynamic responses, is likely to undergo changes during healthy aging and during pathological processes related to neurodegenerative disease (Logothetis et al. 2001; D’Esposito et al. 1999). It is important to remember that BOLD fMRI is an indirect measure of neuronal activity, which can be impacted by blood flow as well as oxygen extraction, and thus there are potential neurovascular effects on baseline cerebral blood flow that may affect the BOLD response. As both increased and decreased BOLD as well as PET activation responses have, however, been reported in AD compared to elderly controls, this does not support the view of attenuation of the BOLD signal purely due to impaired vascular reactivity. The alterations in BOLD activity reported in AD also appear to be quite regionally specific and dependent on the nature of the cognitive task, making it unlikely that the changes observed in fMRI studies represent global pathophysiological alterations in neurovascular coupling.

In addition to functional activation studies, there has recently been considerable interest in studying the intrinsic connectivity of brain networks during the resting state using BOLD fMRI techniques, often referred to as functional connectivity or fc-MRI (Biswal et al. 1995). These techniques examine the correlation between the intrinsic oscillations or time courses of brain regions, and have revealed a number of brain networks which demonstrate significant coherence in the spontaneous activity of distributed nodes (Vincent et al. 2006). One of the most ubiquitous networks detected across subjects in various states of arousal is the default network (Shulman et al. 1997; Raichle et al. 2001; Greicius et al. 2003), and dysfunction of the default network has now been implicated in a number of neuropsychiatric disorders affecting cognition (Greicius et al. 2003; Buckner et al. 2008).

Among functional neuroimaging techniques, fMRI has many potential advantages in studying patients with neurodegenerative disorders. fMRI sessions can be repeated many times over the course of a longitudinal study, as it is a non-invasive imaging technique that does not require injection of a contrast agent, and thus lends itself well as a measure in clinical drug trials. It has relatively high spatial and temporal resolution, and the use of event-related designs enables the hemodynamic correlates of specific behavioral events, such as successful memory formation (Brewer et al. 1998; Wagner et al. 1998; Sperling et al. 2003a; Dickerson et al. 2007b) to be measured.

Despite these advantages, there are significant challenges in performing fMRI studies in older and cognitively impaired patients, as well as caveats to the interpretation of fMRI findings in general. The BOLD fMRI technique is particularly sensitive to even small amounts of head motion. Differences in task performance between patient and control groups complicate data interpretation, as the ability to perform the task may greatly influence the pattern and degree of observed fMRI activity (Price and Friston 1999) (Pariente et al. 2005). Disease-related alterations in brain structure may make it difficult to interpret the source of abnormalities in functional data (i.e., hypoactivation may reflect atrophy in addition to primary functional changes). These issues pose analytic challenges (e.g., structural–functional image co-registration; multi-subject co-registration). Functional neuroimaging measures may also be affected by transient brain and body states at the time of imaging, such as arousal, attention, sleep deprivation, sensory processing of irrelevant stimuli, or the effects of substances with pharmacologic central nervous system activity, which are commonly used in older individuals with cognitive impairment. It is also important to keep in mind that the abnormalities found in fMRI studies of AD patients may be heavily dependent on the type of behavioral task used in the study. Also, the nature of functional abnormalities may depend on whether the activated brain regions are directly affected by the disease, are indirectly affected via connectivity, or are not pathologically affected. Similarly, the ability to perform the task may greatly influence the pattern and degree of fMRI activity, as suggested by event-related subsequent memory studies. Finally, it is critical to complete further reliability experiments if fMRI is to be used widely in longitudinal or pharmacologic studies. Although there are now a few studies of fMRI test–retest reliability in young subjects (Machielsen et al. 2000; Manoach et al. 2001; Sperling et al. 2002), reproducibility studies are only beginning to be performed in MCI and AD patients (Clement and Belleville 2009). Recent advances in both the acquisition and analytic approaches to fMRI data should continue to improve our ability to utilize fMRI in multi-center studies.

Brain Networks Supporting Episodic Memory Function

Converging evidence strongly supports the hypothesis that memory function is subserved by a distributed network of brain regions, including the hippocampus, adjacent cortical regions in the MTL, and a distributed network of cortical regions connected through mono- and poly-synaptic projections. Based on the seminal work with the patient H.M. and a wealth of animal work, the majority of early fMRI and volumetric MRI studies were focused on the hippocampus. The hippocampus and specific medial temporal cortices may be particularly critical for binding novel associations into cohesive episodic memory traces (Squire and Zola-Morgan 1991; Eichenbaum and Bunsey 1995; Sperling et al. 2003a), providing a potential explanation for the selective vulnerability of associative memory processes in prodromal AD. One primary role of the hippocampal formation in episodic encoding is to form new associations between previously unrelated items of information (Squire and Zola-Morgan, 1991; Eichenbaum et al. 1996). Several fMRI studies in young subjects using a face-name associative encoding task (Sperling et al. 2001, 2002, 2003a) have demonstrated that associative memory paradigms produce robust activation of the anterior hippocampal formation (Small et al. 2001; Zeineh et al. 2003; Kirwan and Stark, 2004). We chose a face-name associative paradigm for our studies as learning the relationship between a name and a face is a particularly difficult cross-modal, non-contextual, paired-associate memory task, and difficulty remembering proper names is the most common memory complaint of older individuals visiting memory clinics (Zelinski and Gilewski, 1988; Leirer et al. 1990). Given their dependence on the integrity of the hippocampal memory system, associative memory tasks may be particularly useful in detecting the earliest memory impairment in AD (Morris et al. 1991; Fowler et al. 2002; Gallo et al. 2004).

Interestingly, recent fMRI studies also suggest that a specific set of regions, characterized as the “default network” (Raichle et al. 2001; Buckner et al. 2008), need to be disengaged or “deactivate” during successful memory formation (Daselaar et al. 2004; Miller et al. 2008b). The “default network” includes the posterior cingulate extending into the precuneus, lateral parietal, and medial prefrontal regions, and has been shown to be more metabolically active at rest, with decreases in activity (deactivation on PET and fMRI studies) in young subjects during most challenging cognitive tasks (Shulman et al. 1997; Buckner et al. 2008).

Anatomic studies and functional imaging studies suggest that key components of the default network, in particular the posteromedial cortices, are strongly connected to the hippocampal memory system (Kobayashi and Amaral 2007). Animal studies have demonstrated that lesioning the MTL specifically deafferents lateral and medial parietal regions (Meguro et al. 2001). Previous fMRI studies of “resting state” functional connectivity have also suggested that even when not engaged in a specific task, the hippocampus is functionally connected to the default network, in particular, posteromedial regions extending from posterior cingulate to precuneus and lateral parietal regions (Greicius et al. 2004; Vincent et al. 2006; Kahn et al. 2008). Task-related fMRI studies, including our own, have also suggested that MTL and posterior cingulate functional activity is reciprocally coordinated during memory tasks (Daselaar et al. 2003; Celone et al. 2006; Daselaar et al. 2006; Miller et al. 2008b) (Pihlajamaki et al. 2008). Recent event-related studies suggest that successful memory formation specifically requires coordinated and reciprocal activity between activation in the hippocampal nodes of the MTL system and deactivation in the retrosplenial–parietal nodes of this large-scale memory network (Miller et al. 2008b).

Although memory encoding tasks are typically associated with task-induced decreases in BOLD MR signal (deactivation) in medial and lateral parietal regions, memory retrieval tasks tend to show task-induced increases (activation) in these same regions (Wagner et al. 2005). Task-induced increases have also been reported in the posterior cingulate during autobiographical memory retrieval (Svoboda et al. 2006) and metamemory processes, involving the subjective evaluation of memory performance, such as confidence judgments regarding recognition memory (Chua et al. 2006). Taken together, these studies implicate a specific memory network, which includes both parietal/posterior cingulate and MTL memory systems that is important for successful memory formation and retrieval. Interestingly, these nodes of the network are selectively vulnerable to early AD pathology, with tangle pathology and cell loss predominately in the MTL, and amyloid deposition in parietal regions.

fMRI Studies in Patients Diagnosed with Clinical AD

Over the past decade, a number of fMRI studies in patients with clinically diagnosed AD, have reported decreased fMRI activation in MTL regions compared to older control subjects during episodic encoding tasks (Small et al. 1999; Rombouts et al. 2000; Kato et al. 2001; Machulda et al. 2003; Sperling et al. 2003b; Gron et al. 2002; Golby et al. 2005; Remy et al. 2004; Hamalainen et al. 2007). These studies have employed a variety of unfamiliar visual stimuli, including faces (Small et al. 1999; Pariente et al. 2005; Rombouts et al. 2005a), face-name pairs (Sperling et al. 2003b), scenes (Golby et al. 2005), line-drawings (Rombouts et al. 2000; Hamalainen et al. 2007), geometric shapes (Kato et al. 2001), and verbal stimuli (Remy et al. 2005), and have consistently reported decreased hippocampal and/or parahippocampal activity in AD patients compared to healthy older controls during the encoding of novel stimuli. Neocortical fMRI changes have also been demonstrated in AD using fMRI, including decreased activation in temporal and prefrontal regions. A recent quantitative meta-analysis (Schwindt and Black 2009) of both fMRI and FDG-PET memory activation studies of AD identified several regions as consistently being more likely to show greater encoding-related activation in controls than in AD patients, including hippocampal formation, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, precuneus, cingulate gyrus, and lingual gyrus.

Interestingly, evidence of increased neural activity, particularly in prefrontal regions, has been observed in AD patients performing memory tasks (Sperling et al. 2003b; Grady et al. 2003). In line with Golby et al. (2005), our recent work demonstrates that the normal suppression of MTL activity to repeated face-name stimuli as compared to visual fixation is significantly impaired in AD (Pihlajamaki et al. 2008). This data suggests that intact MTL repetition suppression may be part of the successful encoding and early consolidation process and that failure of MTL repetition suppression is a potential indicator of impaired MTL and memory function early in the course of AD (Pihlajamaki et al. 2009). The recent meta-analysis also reported that AD patients showed greater encoding-related activation in ventrolateral prefrontal, orbitofrontal, dorsolateral prefrontal, superior temporal, and fusiform regions, compared to controls. Regions involved in the so-called “cognitive control network” (dorsolateral prefrontal, posterolateral parietal, anterior cingulate, frontoinsula) were also less engaged in AD compared to controls, indicating the contribution of dysfunction in other cortical networks to impaired memory function in AD (Schwindt and Black 2009).

Recent studies have also suggested that the default network demonstrates markedly abnormal responses during memory tasks in clinical AD patients and in subjects at risk for AD (Lustig and Buckner 2004; Celone et al. 2006; Petrella et al. 2007; Pihlajamaki et al. 2008, 2009). Interestingly, the same default network regions that typically demonstrate beneficial deactivations in healthy young subjects (Daselaar et al. 2006), especially the posterior cingulate/precuneus, tend to manifest a paradoxical increase in fMRI activity above baseline in AD patients. It remains unclear whether this aberrant default network activity is due to alterations in baseline synaptic activity, as these regions typically demonstrate hypometabolism at rest in AD patients (Meltzer et al. 1996; Silverman et al. 2001; Alexander et al. 2002) and subjects at-risk for AD (Small et al. 2000; Reiman et al. 2004; Jagust et al. 2006). Interestingly, these regions demonstrating the aberrant default network activity also overlap the anatomy of regions with high amyloid burden in early AD (Klunk et al. 2004), which is discussed more extensively below.

fMRI Studies in Older Subjects with Mild Cognitive Impairment

It is likely that fMRI will prove most useful in understanding earlier stages of AD, as the diagnosis of AD at the stage of clinical dementia does not require a 3T magnet, and it is not particularly surprising that AD patients with significant memory impairment fail to engage the hippocampus. fMRI may be particularly valuable in the study of individuals with very mild symptoms suggestive of AD, at the point that they are still largely independent in daily function (Dickerson and Sperling 2005). Currently, individuals in this stage are often classified as having amnestic MCI, with memory impairment that is insufficient to impact daily function at the level of dementia (Petersen et al. 1999; Grundman et al. 2004). This gradual transitional state of MCI may last for a number of years (Dickerson et al. 2007a; Amieva et al. 2008), but some individuals with MCI will never progress to clinical AD, and may not even harbor AD neuropathology (Petersen et al. 2006). In other individuals, these early symptoms are likely already manifestations of AD (Morris and Cummings 2005), and the combination of early memory impairment with imaging and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers may allow earlier, accurate identification of the AD phenotype (Dubois et al. 2007). Given the growing body of evidence that alterations in synaptic function are present very early in the disease process, possibly long before the development of clinical symptoms and even significant neuropathology (Selkoe 2002; Coleman et al. 2004), fMRI may be particularly useful for detecting alterations in brain function that may be present very early in the course of AD, such as during the stages of MCI.

With respect to task-related activation in MCI, a handful of fMRI studies have been published to date and the results, thus far, have been variable, with some studies identifying a lesser degree of MTL activation in MCI compared to controls (Small et al. 1999; Machulda et al. 2003; Johnson et al. 2006b). Petrella et al. (2006) found no differences between MCI and controls in MTL activation during encoding, but observed hippocampal hypoactivation in MCI versus controls during retrieval. Hippocampal hypoactivation in MCI was no longer seen when memory performance accuracy was included as a covariate in the analysis. Johnson et al. used a paradigm involving the repetitive presentation of faces to demonstrate that MCI patients do not show the same slope of decreasing hippocampal activation with face repetition that is seen in older controls, suggesting disruption of this “adaptive” response in the MTL (Johnson et al. 2004).

Several studies have reported greater MTL activation in MCI patients compared to controls. We used an associative face-name encoding paradigm to compare MTL activation in very mild MCI, AD, and controls (Dickerson et al. 2005). Compared with controls, MCI subjects showed a greater extent of hippocampal activation and a trend toward greater entorhinal activation. Furthermore, there was minimal atrophy of the hippocampal formation or entorhinal cortex in this MCI group. Across all the subjects in the three groups, post-scan memory task performance correlated with extent of activation in both the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus.

Other groups have reported a similar phenomenon of hyperactivation in MCI using visual object encoding paradigms (Hamalainen et al. 2007), and event-related verbal memory paradigms (Heun et al. 2007; Kircher et al. 2007). A common aspect to the studies reporting evidence of increased fMRI activity is that the MCI subjects were able to perform the fMRI tasks reasonably well. In particular, the event-related fMRI studies found that the hyperactivity was observed specifically during successful memory trials, suggesting that the increased activity may serve as a compensatory mechanism in the setting of early AD pathology (Dickerson and Sperling 2008). Additional studies employing event-related fMRI paradigms will be very helpful in determining whether increased MTL activation in MCI patients is specifically associated with successful memory, as opposed to a general effect that is present regardless of success (possibly indicating increased effort).

The mechanistic underpinnings of MTL hyperactivation remain unclear. This phenomenon may reflect cholinergic or other neurotransmitter upregulation in MCI patients (DeKosky et al. 2002). Alternatively, increased regional brain activation may be a marker of the pathophysiologic process of AD itself, such as aberrant sprouting of cholinergic fibers (Hashimoto and Masliah 2003) or inefficiency in synaptic transmission (Stern et al. 2004). It is important, however, to acknowledge that multiple nonneural factors may confound the interpretation of changes in the hemodynamic response measured by BOLD fMRI, such as resting hypoperfusion and metabolism in MCI and AD, which may result in an altered BOLD fMRI signal during activation (Davis et al. 1998; Cohen et al. 2002). Further research to determine the specificity of hyperactivation with respect to particular brain regions and behavioral conditions, and the relationship to baseline perfusion and metabolism will be valuable to better characterize this phenomenon.

Similar to AD, there is recent evidence that areas of the default mode network such as the posteromedial and anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortices are significantly affected also in subjects with MCI relative to controls, even when accounting for atrophy (Rombouts et al. 2005a; Celone et al. 2006; Petrella et al. 2006, 2007; Sorg et al. 2007). At this point, it is, however, worth noting that concepts such as brain “default mode” or “resting state” are not always interpreted similarly throughout the neuroscience and neuroimaging communities but continue to be a topic of active research (Morcom and Fletcher 2007) and interpretation of the “awake resting state” when lying inside the MRI scanner in elderly subjects with neurodegenerative disorders is not totally unproblematic.

Functional Alterations as a Predictive Biomarker in MCI

We have recently extended a preliminary analysis of fMRI as a predictor of dementia in MCI (Dickerson et al. 2004). Over a follow-up interval of more than 5 years after fMRI scanning in 25 MCI subjects some showed no change and others progressed to dementia (change in Clinical Dementia Rating Scale-Sum-of-Boxes (CDR-SB), a measure of functional impairment across multiple domains, ranged from 0 to 4.5). The degree of cognitive decline was predicted by hippocampal activation at the time of baseline scanning, with greater hippocampal activation predicting greater decline (Miller et al. 2008a). This finding was present even after controlling for baseline degree of impairment (CDR-SB), age, education, and hippocampal volume. These data suggest that fMRI may provide a physiologic imaging biomarker useful for identifying the subgroup of MCI individuals at highest risk of cognitive decline for potential inclusion in disease-modifying clinical trials.

We have recently completed a longitudinal fMRI study in a group of 51 older individuals, across a range of cognitive impairment, imaged with alternate forms of the face-name paradigm at baseline and 2-year follow-up (Sperling et al. 2008). Preliminary analyses indicate that subjects who remained cognitively normal over the 2 years demonstrated no evidence of change in activation, whereas the subjects who demonstrated significant cognitive decline demonstrated a decrease in activation, specifically in the right hippocampal formation. Interestingly, we again observed that those subjects who declined had greater hippocampal activation at baseline, and that the amount of hyperactivation at baseline correlated with both loss of hippocampal signal and amount of clinical decline over 2 years. Thus, although we have hypothesized that hippocampal hyperactivation may be compensatory, it may also be a harbinger of impending hippocampal failure.

If, in fact, the “inverse U-shaped curve” of hyperactivation that we hypothesize takes place early in the course of prodromal AD (at the clinical stage of MCI) is confirmed by future longitudinal studies, then the use of fMRI as a physiologic imaging biomarker will have to grapple with the problem of “pseudonormalization” of activation when individuals with MCI demonstrate progressive decline that results in the loss of hyperactivation. It may be possible to use a combination of clinical (e.g., CDR Sum-of-Boxes), neuropsychologic (e.g., memory tasks), anatomic (e.g., hippocampal and/or entorhinal volume), and molecular (e.g., FDG-PET) measures to assist in the determination of where an individual is along the inverse U-shaped curve of MTL activation. That is, moderate hyperactivation in the setting of minimal clinical and memory impairment and relatively little MTL atrophy would be consistent with the upgoing phase of the hyperactivation curve while the same level of hyperactivation in the setting of more prominent clinical and memory impairment and MTL atrophy would be consistent with the downgoing phase of the curve. In the end, it will be critical to perform longitudinal studies to determine whether this model of the physiologic, anatomic, and behavioral progression of MCI is supported by trajectories in individuals and groups of subjects.

It also appears that alterations in hippocampal activation and parietal deactivation over the course of MCI and AD are strongly correlated (Celone et al. 2006). Similarly, resting state fMRI data has demonstrated alterations in parietal and hippocampal connectivity in MCI and AD (Greicius et al. 2004). Thus, converging evidence suggests that a distributed memory network is disrupted by the pathophysiological process of AD, which includes both MTL systems and posteromedial cortices involved in default mode activity. Future studies to probe alterations in connectivity between these system, which combine fMRI with other techniques such as diffusion tensor imaging, may prove particularly valuable in elucidating the early functional alterations in AD (Wierenga and Bondi 2007).

fMRI Studies in Asymptomatic Subjects at Genetic Risk for AD

Asymptomatic individuals with genetic risk factors for AD, such as carriers of the apolipoprotein E ε4 allele or autosomal dominant mutations such as presenilin 1, are particularly important subjects to assess with functional imaging. Bookheimer et al. (2000) reported that, despite equivalent performance on a verbal paired-associate task, cognitively intact ApoE ε4 carriers showed significantly greater activation, particularly prominent in bilateral MTL regions, compared to non-carriers. Subsequent studies stratified by ApoE genotype have been somewhat mixed in their results, with nearly equal number of studies reporting greater activation in ApoE ε4 carriers (Smith et al. 2002; Wishart et al. 2004; Bondi et al. 2005; Fleisher et al. 2005; Han et al. 2007) and decreased activation in ApoE ε4 carriers (Smith et al. 1999; Lind et al. 2006a, b; Trivedi et al. 2006; Borghesani et al. 2007; Mondadori et al. 2007), compared to non-carriers.

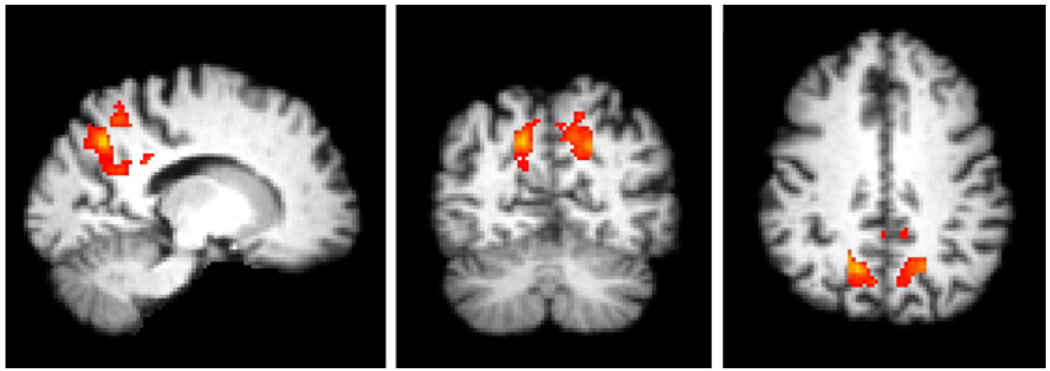

A recent study in young (ages 20–35) ApoE ε4 carriers revealed evidence of both altered default network connectivity at rest and increased hippocampal activation relative to non-carriers (Filippini et al. 2009). Other recent studies have demonstrated altered default network activity in older ApoE ε4 carriers (Persson et al. 2008). We have recently shown in 75 elderly subjects ranging from cognitively normal to mild AD, divided into ApoE ε4 carriers and non-carriers, that the fMRI activity of the posteromedial cortices and other key regions of the default network is also affected in cognitively normal elderly ε4 carriers compared to non-carriers consistent with the idea that these regions are particularly vulnerable to the early pathological changes of AD (Pihlajamaki et al. 2009). In this study, greater failure of posteromedial deactivation was also related to worse memory performance (delayed recall) across all 75 subjects as well as within the range of cognitively normal subjects and thus we concluded that the posteromedial cortical fMRI response pattern may be modulated both by the presence of ApoE ε4 allele and episodic memory capability (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Group fMRI map demonstrating posteromedial regions of the default network with significant differences in task-induced deactivation comparing ApoE ε4 carriers to non-carriers. Cognitively intact older ApoE ε4 carriers demonstrate failure of normal default network activity during memory encoding, similar to the pattern reported in clinical Alzheimer’s disease patients (Pihlajamaki et al. 2009)

Individuals with other genetic risk factors for AD have also been studied with functional neuroimaging. Haier et al. (2003) reported FDG-PET evidence of increased MTL activation (hypermetabolism) during cognitive tasks in non-demented Down’s syndrome patients. A recent fMRI study by Mondadori et al. also found evidence of increased activation, which was specific to the episodic memory paradigm, in a young asymptomatic carrier of the presenilin 1 mutation (Mondadori et al. 2006). A middle-aged presenilin 1 mutation carrier who fulfilled criteria for amnesic MCI showed decreased task-related activation. This study parallels the findings across the continuum of impairment in MCI subjects discussed above, and again suggests that there may be a non-linear trajectory of fMRI activation that evolves over the course of prodromal AD (Sperling 2007). Again, the variable results reported in genetic at-risk subjects will likely benefit from longitudinal fMRI testing, ideally in combination with amyloid and FDG-PET imaging and detailed volumetric measurements. These types of studies will probably provide critical information to improve our understanding of the temporal sequence of events early in the course of prodromal AD.

In an exciting area of recent research, there have been several studies of individuals with a family history of AD but without known genetic abnormalities. Again, somewhat discrepant results have been reported. Compared to a control group without a family history of AD, adult children of autopsy-confirmed AD patients exhibited increased activation in the frontal and temporal lobes, including the hippocampus (Bassett et al. 2006). Although a large percentage of the at-risk subjects possessed at least one copy of the ApoE ε4 allele, the increased activation was found to be unrelated to this genetic risk. Johnson et al. (2006a) have conducted two large fMRI studies comparing asymptomatic middle-aged adults (mean age 55) who have a parent clinically diagnosed with sporadic AD versus matched controls without parental history of AD. Both of these studies, one an encoding task and one a metamemory task, demonstrated decreased hippocampal activation in the higher risk group. Interestingly, although there was no main effect of ApoE genotype seen in these studies, the group with a negative family history but who did possess an ApoE ε4 allele showed the greatest hippocampal activation. This group also performed at the highest level of accuracy in the recognition task. These studies, which stratify subjects by family history, suggest that there may be a complicated interaction between ApoE and other genetic risk factors that influence hippocampal activation.

Intrinsic Funtional Connectivity (fc-MRI) Studies

As mentioned above, recent studies have used similar BOLD fMRI techniques to study spontaneous brain activity and the inter-regional correlations between neural activity even in the absence of task. These studies have clearly documented the organization of the brain into multiple large-scale brain networks, which persist even during sleep and anesthesia (Vincent et al. 2007), and support specific sensory and motor systems, as well as cognitive processes, such as the default network (Vincent et al. 2006). Interestingly, both independent component analyses and “seed-based” connectivity techniques have demonstrated the robust intrinsic connectivity between the posteromedial nodes of the default network, in particular the posterior cingulate/precuneus, with the hippocampus. Multiple groups have confirmed impaired intrinsic functional connectivity in the default network during the resting state in MCI and AD (Greicius et al. 2004; Rombouts et al. 2005b; Sorg et al. 2007; Bai et al. 2008; Rombouts et al. 2009) which appears to be over and above more general age-related disruption of large-scale networks (Andrews-Hanna et al. 2007; Damoiseaux et al. 2008). One recent study suggests that these resting fMRI techniques may be more readily applied to at-risk clinical populations than task fMRI (Fleisher et al. 2009).

Relationship of Amyloid Pathology to Memory Network Disruption

The relationship between amyloid pathology and memory impairment in humans remains controversial. Recent laboratory and transgenic animal studies suggest that soluble oligomeric forms of Aβ may directly impair synaptic function and long-term potentiation (LTP) (Walsh et al. 2002; Klyubin et al. 2005; Klein 2006; Lesne et al. 2006), alter dendritic spine morphology (Spires et al. 2005; Alpar et al. 2006), and contribute to synaptic failure (Walsh and Selkoe 2004). Fibrillar forms of Aβ may also cause disruption of the neuropil, resulting in dystrophic neurites and markedly altered axonal trajectories (D’Amore et al. 2003; Spires and Hyman 2004), impair evoked synaptic responses (Stern et al. 2004), occurring within days of plaque formation (Meyer-Luehmann et al. 2008). Furthermore, converging laboratory data suggest that decreasing oligomeric forms of Aβ can acutely restore LTP and improve behavioral deficits in animals (Dodart et al. 2002; Cleary et al. 2005; Klyubin et al. 2005; Oddo et al. 2006). Most intriguing are preliminary reports that immunotherapy approaches to remove amyloid may have at least some subtle positive effects on memory measures in AD patients (Gilman et al. 2005; Weksler et al. 2005; Black et al. 2010). Our own preliminary work with fMRI in the double-blind Phase I trial of a monoclonal antibody against Aβ 1–42 also suggests that there may be relatively acute effects on cognitive performance and hippocampal activation after a single dose of antibody, similar to reports in the animal literature (Dodart et al. 2002; Black et al. 2010).

The paradox, however, is that despite compelling genetic and laboratory evidence for a central role of Aβ in the pathogenesis of AD, the presence of fibrillar amyloid deposition seen at postmortem has not correlated particularly well with antemortem clinical status. Several autopsy studies suggest that the amount and location of fibrillar amyloid deposition does not relate strongly to the degree and type of clinical impairment (Arriagada et al. 1992b; Ingelsson et al. 2004), compared to tau pathology and neuronal loss (Markesbery et al. 2006). In addition, the amyloid deposition is relatively predominant in neocortical regions, compared to the MTL structures traditionally implicated in memory impairment. The most striking dissociation is that a substantial percentage of individuals known to be cognitive intact prior to death demonstrate significant amyloid pathology at autopsy (Arriagada et al. 1992a; Katzman 1997; Hulette et al. 1998; Price and Morris 1999; Bennett et al. 2006). There are several intriguing possibilities to explain this paradox: (1) Amyloid pathology is not directly related to memory impairment, despite the aforementioned compelling laboratory evidence. (2) Amyloid is primarily toxic to neurons in oligomeric forms, which are not well measured in autopsies or with PiB-PET imaging. In fact, it has been suggested that plaque deposition might represent a successful sequestration strategy for toxic forms of soluble Aβ, representing a protective mechanism; (3) Fibrillar amyloid does result in synaptic dysfunction and neuronal damage, perhaps by creating a reservoir of oligomeric Aβ, but some individuals are able to tolerate the amyloid burden without evidence of clinical impairment, perhaps due to cognitive and brain reserve (Stern 2006); (4) Amyloid deposition is necessary and sufficient to incite the pathophysiological cascade leading to clinical AD, but this process may take many years (Morris et al. 1996). We believe that a combination of the latter two is most likely, that is: we hypothesize that amyloid is associated with synaptic dysfunction and neuronal damage. While some individuals are able to compensate for amyloid-related toxicity for an extended time period, sensitive imaging and neuropsychological markers will reveal that normal subjects with evidence of high amyloid burden demonstrate evidence of aberrant memory related activity, in a pattern similar to that observed in prodromal AD, and the majority of these subjects will eventually develop subtle memory impairment over time.

Fortunately, we now have the exciting opportunity to be able to detect fibrillar amyloid in vivo and to begin to investigate some of the above hypotheses. A number of molecular imaging agents for the in vivo detection of AD pathology are under active development. The best characterized of the agents in current human use, and the majority of published human studies, are with 11-C PiB. PiB crosses the blood–brain barrier rapidly after intravenous administration, has a high affinity for sites on the beta-sheet structure of fibrillar Aβ, and is metabolized to polar derivatives that do not enter the brain (Mathis et al. 2003; Klunk et al. 2004). Postmortem tissue studies have indicated that PiB binds specifically to amyloid-laden brain regions (Bacskai et al. 2007; Ikonomovic et al. 2008). It is estimated that more than 3000 humans have now received PiB without any significant adverse events (Mathis, personal communication).

The anatomic distribution of PiB retention overlaps the cortical regions characteristically demonstrating atrophy and hypometabolism in AD including the precuneus, posterior cingulate, lateral parietal, and medial prefrontal cortices (Buckner et al. 2005). The precuneus and posterior cingulate are of particular interest because of the convergence of these regions’ vulnerability to early amyloid deposition, and its critical role in memory function, both during encoding and retrieval. As daily life involves a constant alternation between the processes of encoding of new information, retrieval of previously encountered information, and assessment as to whether information is novel or familiar, these regions may be nearly continuously oscillating between an activated and deactivated state, which may be particularly metabolically demanding. Laboratory evidence suggests that neuronal activity may directly increase production of amyloid-beta peptides (Cirrito et al. 2005). Thus, the critical role of the default network in memory function and its heightened and constant fluctuations in activity might serve to increase the production of amyloid-β protein in this network.

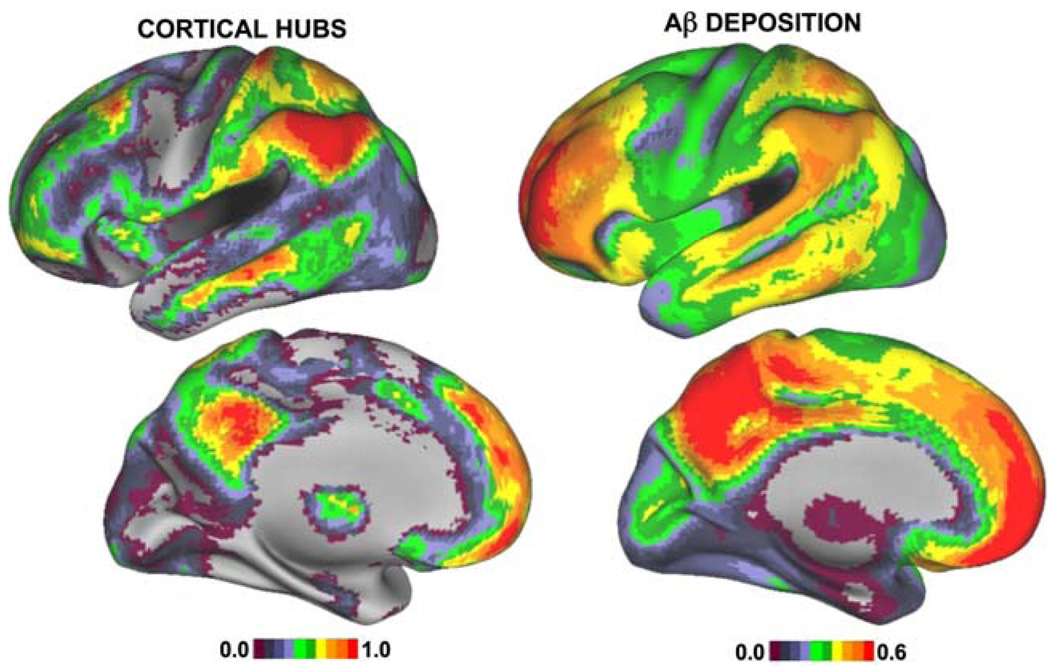

We have also recently noted that these default network regions are prominent “hubs” in intrinsic cortical connectivity, and that the topography of hubs with high connectivity in normal young individuals overlapped the anatomic distribution of amyloid deposition in AD patients (Buckner et al. 2009) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Surface maps indicating the location of cortical hubs estimated in 127 healthy young subjects (shown on left) and the pattern of amyloid-β deposition on PiB-PET imaging in 10 patients with clinical Alzheimer’s disease compared to 29 healthy older control subjects (Buckner et al. 2009)

Since the initial report of human PiB PET imaging in early 2004, there have been several reports indicating that a substantial fraction of clinically normal (CN) control subjects are “PiB positive” (PiB+), with elevated PiB retention in cortical regions typically affected in AD (Buckner et al. 2005; Lopresti et al. 2005; Fagan et al. 2006; Mintun et al. 2006; Rentz et al. 2006; Johnson et al. 2007; Pike et al. 2007; Gomperts et al. 2008; Jack et al. 2008). Many of these CN subjects have levels of PiB retention that are within the range of PiB binding seen in AD patients, but the fraction reported to be “PiB+” has been variable, largely depending on whether younger subjects were included in the analysis. Reports of the fraction of PiB + NC subjects has ranged from 10% in a group that included subjects from 20 to 86 years old (Mintun et al. 2006), 31% in subjects over the age of 70 (Mintun et al. 2008) to recent reports of approximately 50% in older subject groups (Gomperts et al. 2008). A recent analysis of the 17 NC subjects from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) with a mean age of 79.5 years reported 56% of these NC subjects had elevated PiB retention (Mathis et al. 2008). These recent reports, as well as our own preliminary data, suggest that age may be the most significant predictor of elevated PiB retention in normal individuals, consistent with the robust finding that age is also the greatest risk factor for developing clinical AD.

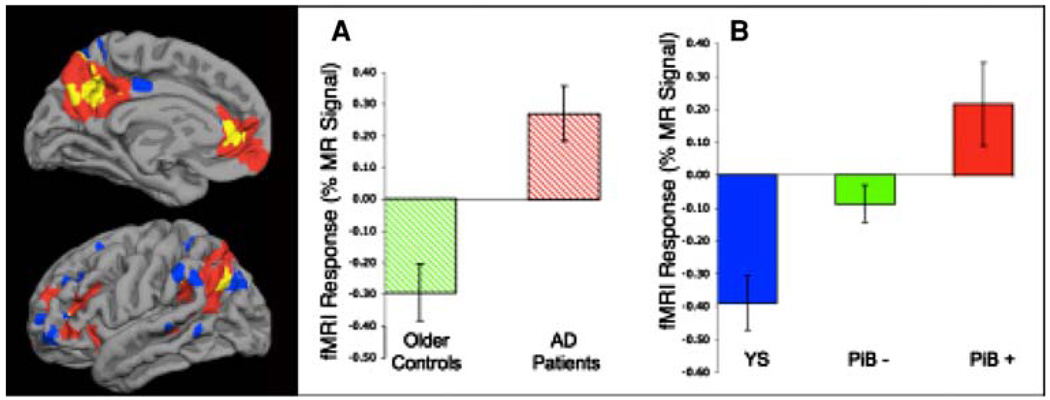

We recently completed a study combining PiB-PET imaging and fMRI in 35 non-demented older individuals (Celone et al. 2006; Sperling et al. 2009). The subjects were either cognitively normal or had very subtle memory complaints (Clinical Dementia Rating Scale of 0.5) but who still performed within the normal range on neuropsychological testing. Approximately 30% of these non-demented older individuals were found to have elevated PiB retention (high amyloid burden), in the range seen in mild AD patients. The high PiB subjects demonstrated very aberrant patterns of default network fMRI activity, particularly evident in the precuneus extending into the posterior cingulate, similar to previous reports in AD patients (Lustig et al. 2003; Pihlajamaki et al. 2008; Pihlajamaki et al. 2009). Interestingly, we found evidence of hippocampal hyperactivity only among the subset of CDR 0.5 subjects, consistent with our previous findings in very early MCI (Dickerson et al. 2005; Celone et al. 2006) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Surface map indicating the overlap between regions of highest PiB-PET retention and aberrant default network fMRI activity in 35 non-demented older individuals. The panel on right demonstrates similar pattern of aberrant default network activity during memory encoding in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (Panel A) and in non-demented older individuals with high amyloid burden (PiB+ in Panel B) (Sperling et al. 2009)

The link between amyloid pathology and dysfunction in the default network cortices, and functionally connected regions within the MTL, in which tangle pathology predominates, remains to be elucidated. Several recent multimodality studies have provided support for the hypothesis that amyloid is an early upstream pathological event, which is related to subsequent neurodegeneration and atrophy in the MTL and surrounding cortices at later stages of prodromal AD (Mormino et al. 2008; Fagan et al. 2009; Jack et al. 2009). Based on our recent data, we have even speculated that amyloid-related aberrant neural activity in this distributed network, including hyperactivity in the hippocampus, might provide a link between amyloid and tau pathology in disparate nodes of the distributed memory network (Celone et al. 2006; Sperling et al. 2009).

Recent molecular and electrophysiological studies in transgenic mouse models may be relevant to our findings of abnormally increased activity in regions with heavy amyloid burden. A recent mouse study suggests that the presence of amyloid plaques may result in abnormally increased neuronal activity in surrounding neurons (Busche et al. 2008). Another study reported evidence of aberrant neuronal excitation that reached the level of non-convulsive seizure activity in mice overexpressing human amyloid precursor (Palop et al. 2007). Thus, our observation of paradoxically increased fMRI signal during memory encoding might reflect a local excitatory response to amyloid pathology, which interferes with the normal inhibition of these neurons during memory encoding. It is also intriguing that the early selective loss of excitatory neuronal function, which has been reported in AD, has also been associated with loss of inhibitory neuronal function (Hyman et al. 1992; Baig et al. 2005), and thus, we have postulated that the functional changes in default network activity in AD might be due to an imbalance of excitatory and inhibitory inputs related to amyloid pathology (Sperling et al. 2009).

Intriguingly, we have also preliminary data suggesting that these same regions demonstrate abnormally increased activity during retrieval in non-demented older adults with high amyloid burden (Vannini et al. 2009). We have also recently found evidence of functional disruption in this distributed memory network at rest, with decreased intrinsic connectivity, specifically between the posterior cingulate and the hippocampus (Hedden et al. 2009). Taken together, these findings suggest that the presence of amyloid pathology in the default network, even in clinically normal older individuals, is associated with functional disruption of the distributed networks supporting memory processes (Celone et al. 2006; Sperling et al. 2009).

Conclusions

The pathophysiological process of AD is associated with alterations in large-scale functional brain networks, in particular, the distributed networks supporting memory function.

Despite the relative infancy of the field, there have already been a number of promising fMRI studies in AD, MCI, and at-risk subjects, which highlight the potential uses of fMRI in both cognitive neuroscience and clinical spheres of investigation. The early manifestations of network dysfunction in prodromal phases of AD may include paradoxical evidence of increased neural activity, in addition to loss of function. It remains unclear whether the phenomenon of hyperactivity is related to compensatory mechanisms or represents evidence of excitotoxicity and impending neural failure.

The combination of molecular and functional imaging techniques should provide further insight into the elusive link between pathology and behavior in AD. Our early work in non-demented older individuals with high amyloid burden suggests that functional alterations in memory networks may precede clinical symptomatology. Ongoing longitudinal studies will determine if these functional imaging markers are sensitive predictors of cognitive decline, and may 1 day prove useful in monitoring response to disease-modifying therapy in the preclinical phases of AD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging P01 AG036694; R01 AG-027435; P50 AG005134, the Alzheimer’s Association, and an Anonymous Medical Foundation.

Contributor Information

Reisa A. Sperling, Email: reisa@rics.bwh.harvard.edu, Department of Neurology, Center for Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 221 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA; Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; The Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Bradford C. Dickerson, Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA The Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Maija Pihlajamaki, Department of Neurology, Center for Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 221 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA; Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Patrizia Vannini, Department of Neurology, Center for Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 221 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA; The Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Peter S. LaViolette, Department of Neurology, Center for Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 221 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA The Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Ottavio V. Vitolo, Department of Neurology, Center for Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 221 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Trey Hedden, Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; The Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

J. Alex Becker, Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Dorene M. Rentz, Department of Neurology, Center for Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 221 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Dennis J. Selkoe, Department of Neurology, Center for Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 221 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Keith A. Johnson, Department of Neurology, Center for Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 221 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

References

- Alexander GE, Chen K, Pietrini P, Rapoport SI, Reiman EM. Longitudinal PET evaluation of cerebral metabolic decline in dementia: A potential outcome measure in Alzheimer’s disease treatment studies. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:738–745. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpar A, Ueberham U, Bruckner MK, Seeger G, Arendt T, Gartner U. Different dendrite and dendritic spine alterations in basal and apical arbors in mutant human amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. Brain Research. 2006;1099(1):189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amieva H, Le Goff M, Millet X, Orgogozo JM, Peres K, Barberger-Gateau P, et al. Prodromal Alzheimer’s disease: Successive emergence of the clinical symptoms. Annals of Neurology. 2008;64:492–498. doi: 10.1002/ana.21509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews-Hanna JR, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Lustig C, Head D, Raichle ME, et al. Disruption of large-scale brain systems in advanced aging. Neuron. 2007;56:924–935. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold SE, Hyman BT, Flory J, Damasio AR, Van Hoesen GW. The topographical and neuroanatomical distribution of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques in the cerebral cortex of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Cerebral Cortex. 1991;1:103–116. doi: 10.1093/cercor/1.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arriagada PV, Growdon JH, Hedley-Whyte ET, Hyman BT. Neurofibrillary tangles but not senile plaques parallel duration and severity of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1992a;42:631–639. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arriagada PV, Marzloff K, Hyman BT. Distribution of Alzheimer-type pathologic changes in nondemented elderly individuals matches the pattern in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1992b;42:1681–1688. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.9.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacskai BJ, Frosch MP, Freeman SH, Raymond SB, Augustinack JC, Johnson KA, et al. Molecular imaging with Pittsburgh compound B confirmed at autopsy: A case report. Archives of Neurology. 2007;64:431–434. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai F, Zhang Z, Yu H, Shi Y, Yuan Y, Zhu W, et al. Default-mode network activity distinguishes amnestic type mild cognitive impairment from healthy aging: A combined structural and resting-state functional MRI study. Neuroscience Letters. 2008;438:111–115. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baig S, Wilcock GK, Love S. Loss of perineuronal net N-acetylgalactosamine in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathologica. 2005;110:393–401. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-1060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakkour A, Morris JC, Dickerson BC. The cortical signature of prodromal AD. Regional thinning predicts mild AD dementia. Neurology. 2008;72:1048–1055. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000340981.97664.2f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett SS, Yousem DM, Cristinzio C, Kusevic I, Yassa MA, Caffo BS, et al. Familial risk for Alzheimer’s disease alters fMRI activation patterns. Brain. 2006;129:1229–1239. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett D, Schneider J, Arvanitakis Z, Kelly J, Aggarwal N, Shah R, et al. Neuropathology of older persons without cognitive impairment from two community-based studies. Neurology. 2006;66:1837–1844. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000219668.47116.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1995;34:537–541. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black R, Sperling R, Kirby L, Safirstein B, Motter R, Pallay A, et al. A single-ascending dose study of bapineuzumab (AAB-001), a humanized monoclonal antibody to A-beta, in AD. Alzheimer’s Disease and Associated Disorders. 2010 doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181c53b00. (e-pub) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondi MW, Houston WS, Eyler LT, Brown GG. fMRI evidence of compensatory mechanisms in older adults at genetic risk for Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;64:501–508. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000150885.00929.7E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookheimer SY, Strojwas MH, Cohen MS, Saunders AM, Pericak-Vance MA, Mazziotta JC, et al. Patterns of brain activation in people at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;343:450–456. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008173430701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghesani PR, Johnson LC, Shelton AL, Peskind ER, Aylward EH, Schellenberg GD, et al. Altered medial temporal lobe responses during visuospatial encoding in healthy APOE*4 carriers. Neurobiology of Aging. 2007;29:981–991. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JB, Zhao Z, Desmond JE, Glover GH, Gabrieli JD. Making memories: Brain activity that predicts how well visual experience will be remembered. Science. 1998;281:1185–1187. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5380.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL. Memory and executive function in aging and AD: Multiple factors that cause decline and reserve factors that compensate. Neuron. 2004;44:195–208. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Andrews-Hanna JR, Schacter DL. The brain’s default network: Anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1124:1–38. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Sepulcre J, Talukdar T, Krienen FM, Liu H, Hedden T, et al. Cortical hubs revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity: Mapping, assessment of stability, and relation to Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:1860–1873. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5062-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Snyder AZ, Shannon BJ, LaRossa G, Sachs R, Fotenos AF, et al. Molecular, structural, and functional characterization of Alzheimer’s disease: Evidence for a relationship between default activity, amyloid, and memory. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:7709–7717. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2177-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busche MA, Eichhoff G, Adelsberger H, Abramowski D, Wiederhold KH, Haass C, et al. Clusters of hyperactive neurons near amyloid plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2008;321:1686–1689. doi: 10.1126/science.1162844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celone KA, Calhoun VD, Dickerson BC, Atri A, Chua EF, Miller SL, et al. Alterations in memory networks in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: An independent component analysis. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:10222–10231. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2250-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetelat G, Landeau B, Eustache F, Mezenge F, Viader F, de la Sayette V, et al. Using voxel-based morphometry to map the structural changes associated with rapid conversion in MCI: A longitudinal MRI study. Neuroimage. 2005;27:934–946. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua EF, Schacter DL, Rand-Giovannetti E, Sperling RA. Understanding metamemory: Neural correlates of the cognitive process and subjective level of confidence in recognition memory. Neuroimage. 2006;29:1150–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirrito JR, Yamada KA, Finn MB, Sloviter RS, Bales KR, May PC, et al. Synaptic activity regulates interstitial fluid amyloid-beta levels in vivo. Neuron. 2005;48:913–922. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary JP, Walsh DM, Hofmeister JJ, Shankar GM, Kuskowski MA, Selkoe DJ, et al. Natural oligomers of the amyloid-beta protein specifically disrupt cognitive function. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8:79–84. doi: 10.1038/nn1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement F, Belleville S. Test-retest reliability of fMRI verbal episodic memory paradigms in healthy older adults and in persons with mild cognitive impairment. Human Brain Mapping. 2009;30:4033–4047. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen ER, Ugurbil K, Kim SG. Effect of basal conditions on the magnitude and dynamics of the blood oxygenation level-dependent fMRI response. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2002;22:1042–1053. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman P, Federoff H, Kurlan R. A focus on the synapse for neuroprotection in Alzheimer disease and other dementias. Neurology. 2004;63:1155–1162. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000140626.48118.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amore JD, Kajdasz ST, McLellan ME, Bacskai BJ, Stern EA, Hyman BT. In vivo multiphoton imaging of a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease reveals marked thioflavine-S-associated alterations in neurite trajectories. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 2003;62:137–145. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Esposito M, Zarahn E, Aguirre GK, Rypma B. The effect of normal aging on the coupling of neural activity to the bold hemodynamic response. Neuroimage. 1999;10:6–14. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1999.0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damoiseaux JS, Beckmann CF, Arigita EJ, Barkhof F, Scheltens P, Stam CJ, et al. Reduced resting-state brain activity in the “default network” in normal aging. Cerebral Cortex. 2008;18:1856–1864. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daselaar SM, Fleck MS, Dobbins IG, Madden DJ, Cabeza R. Effects of healthy aging on hippocampal and rhinal memory functions: An event-related fMRI study. Cerebral Cortex. 2006;16(12):1771–1782. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daselaar SM, Prince SE, Cabeza R. When less means more: Deactivations during encoding that predict subsequent memory. Neuroimage. 2004;23:921–927. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daselaar SM, Veltman DJ, Rombouts SA, Raaijmakers JG, Jonker C. Neuroanatomical correlates of episodic encoding and retrieval in young and elderly subjects. Brain. 2003;126:43–56. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TL, Kwong KK, Weisskoff RM, Rosen BR. Calibrated functional MRI: Mapping the dynamics of oxidative metabolism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:1834–1839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKosky ST, Ikonomovic MD, Styren SD, Beckett L, Wisniewski S, Bennett DA, et al. Upregulation of choline acetyltransferase activity in hippocampus and frontal cortex of elderly subjects with mild cognitive impairment. Annals of Neurology. 2002;51:145–155. doi: 10.1002/ana.10069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKosky ST, Marek K. Looking backward to move forward: Early detection of neurodegenerative disorders. Science. 2003;302:830–834. doi: 10.1126/science.1090349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson BC, Miller SL, Greve DN, Dale AM, Albert MS, Schacter DL, et al. Prefrontal-hippocampal-fusiform activity during encoding predicts intraindividual differences in free recall ability: An event-related functional-anatomic MRI study. Hippocampus. 2007a;17(11):1060–1070. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson BC, Salat DH, Bates JF, Atiya M, Killiany RJ, Greve DN, et al. Medial temporal lobe function and structure in mild cognitive impairment. Annals of Neurology. 2004;56:27–35. doi: 10.1002/ana.20163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson BC, Salat D, Greve D, Chua E, Rand-Giovannetti E, Rentz D, et al. Increased hippocampal activation in mild cognitive impairment compared to normal aging and AD. Neurology. 2005;65:404–411. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000171450.97464.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson BC, Sperling RA. Neuroimaging biomarkers for clinical trials of disease-modifying therapies in Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroRx. 2005;2:348–360. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.2.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson BC, Sperling RA. Functional abnormalities of the medial temporal lobe memory system in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: Insights from functional MRI studies. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:1624–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson BC, Sperling RA, Hyman BT, Albert MS, Blacker D. Clinical prediction of Alzheimer disease dementia across the spectrum of mild cognitive impairment. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007b;64:1443–1450. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodart JC, Bales KR, Gannon KS, Greene SJ, DeMattos RB, Mathis C, et al. Immunization reverses memory deficits without reducing brain Abeta burden in Alzheimer’s disease model. Nature Neuroscience. 2002;5:452–457. doi: 10.1038/nn842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Dekosky ST, Barberger-Gateau P, Cummings J, et al. Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. Lancet Neurology. 2007;6:734–746. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H, Bunsey M. On the binding of associations in memory: Clues from studies on the role of the hippocampal region in paired-associate learning. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1995;4:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H, Schoenbaum G, Young B, Bunsey M. Functional organization of the hippocampal memory system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:13500–13507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AM, Head D, Shah AR, Marcus D, Mintun M, Morris JC, et al. Decreased cerebrospinal fluid Abeta(42) correlates with brain atrophy in cognitively normal elderly. Annals of Neurology. 2009;65:176–183. doi: 10.1002/ana.21559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Mach RH, Lee SY, Dence CS, Shah AR, et al. Inverse relation between in vivo amyloid imaging load and cerebrospinal fluid Abeta42 in humans. Annals of Neurology. 2006;59:512–519. doi: 10.1002/ana.20730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippini N, MacIntosh BJ, Hough MG, Goodwin GM, Frisoni GB, Smith SM, et al. Distinct patterns of brain activity in young carriers of the APOE-epsilon4 allele. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:7209–7214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811879106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleisher AS, Houston WS, Eyler LT, Frye S, Jenkins C, Thal LJ, et al. Identification of Alzheimer disease risk by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Archives of Neurology. 2005;62:1881–1888. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.12.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleisher AS, Sherzai A, Taylor C, Langbaum JB, Chen K, Buxton RB. Resting-state BOLD networks versus task-associated functional MRI for distinguishing Alzheimer’s disease risk groups. Neuroimage. 2009;47(4):1678–1690. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler KS, Saling MM, Conway EL, Semple JM, Louis WJ. Paired associate performance in the early detection of DAT. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2002;8:58–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo DA, Sullivan AL, Daffner KR, Schacter DL, Budson AE. Associative recognition in Alzheimer’s disease: Evidence for impaired recall-to-reject. Neuropsychology. 2004;18:556–563. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.18.3.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman S, Koller M, Black RS, Jenkins L, Griffith SG, Fox NC, et al. Clinical effects of Abeta immunization (AN1792) in patients with AD in an interrupted trial. Neurology. 2005;64:1553–1562. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000159740.16984.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golby A, Silverberg G, Race E, Gabrieli S, O’Shea J, Knierim K, et al. Memory encoding in Alzheimer’s disease: An fMRI study of explicit and implicit memory. Brain. 2005;128:773–787. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomperts SN, Rentz DM, Moran E, Becker JA, Locascio JJ, Klunk WE, et al. Imaging amyloid deposition in Lewy body diseases. Neurology. 2008;71:903–910. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000326146.60732.d6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady CL, McIntosh AR, Beig S, Keightley ML, Burian H, Black SE. Evidence from functional neuroimaging of a compensatory prefrontal network in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:986–993. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00986.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Krasnow B, Reiss AL, Menon V. Functional connectivity in the resting brain: A network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:253–258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135058100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Srivastava G, Reiss AL, Menon V. Default-mode network activity distinguishes Alzheimer’s disease from healthy aging: Evidence from functional MRI. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:4637–4642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308627101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gron G, Bittner D, Schmitz B, Wunderlich AP, Riepe MW. Subjective memory complaints: Objective neural markers in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and major depressive disorder. Annals of Neurology. 2002;51:491–498. doi: 10.1002/ana.10157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundman M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment can be distinguished from Alzheimer disease and normal aging for clinical trials. Archives of Neurology. 2004;61:59–66. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haier RJ, Alkire MT, White NS, Uncapher MR, Head E, Lott IT, et al. Temporal cortex hypermetabolism in Down syndrome prior to the onset of dementia. Neurology. 2003;61:1673–1679. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000098935.36984.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamalainen A, Pihlajamaki M, Tanila H, Hanninen T, Niskanen E, Tervo S, et al. Increased fMRI responses during encoding in mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiology of Aging. 2007;28:1889–1903. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han SD, Houston WS, Jak AJ, Eyler LT, Nagel BJ, Fleisher AS, et al. Verbal paired-associate learning by APOE genotype in non-demented older adults: fMRI evidence of a right hemispheric compensatory response. Neurobiology of Aging. 2007;28:238–247. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto M, Masliah E. Cycles of aberrant synaptic sprouting and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s and dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurochemical Research. 2003;28:1743–1756. doi: 10.1023/a:1026073324672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden T, Van Dijk K, Becker JA, Mehta A, Sperling RA, Johnson KA, et al. Disruption of default network functional connectivity in clinically normal older adults harboring amyloid burden. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(40):12686–12694. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3189-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heun R, Freymann K, Erb M, Leube DT, Jessen F, Kircher TT, et al. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and actual retrieval performance affect cerebral activation in the elderly. Neurobiology of Aging. 2007;28:404–413. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]