Abstract

Background

Several genetic mechanisms have been proposed for the variability of the KS phenotype such as the parent-of-origin of the extra X chromosome. Parent-of-origin effects on behavior in KS can possibly provide insights into X-linked imprinting effects on psychopathology that may be extrapolated to other populations. Here, we investigated whether the parent-of-origin of the supernumerary X chromosome influences autistic and schizotypal symptom profiles in KS.

Methods

Parent-of-origin of the X chromosome was determined through analysis of the polymorphic CAG tandem repeat of the androgen receptor. Autistic traits (Autism Diagnostic Interview-revised) were measured in a younger KS sample (n=33) with KS and schizoptypal traits (Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire) were assessed in an older KS sample (n=43). Scale scores on these questionnaires were entered in statistical analyses to test parent-of-origin effects.

Results

The results show that parent-of-origin of the X chromosome is reflected in autistic and schizotypal symptomatology. Differences were shown in the degree of both schizotypal and autistic symptoms between the parent-of-origin groups. Furthermore, the parent-of-origin could be correctly discriminated in more than 90% of subjects through ADI-R scales and in around 80 % of subjects through SPQ scales.

Discussion

These findings point to parent-of-origin effects on psychopathology in KS and indicate that imprinted X chromosomal genes may have differential effects on autistic and schizotypal traits. Further exploration of imprinting effects on psychopathology in KS is needed to confirm and expand on our findings.

Keywords: Genetics, Autism, Schizotypy, Schizophrenia, Genetics, Imprinting, Parent-of-origin, Klinefelter, Sex chromosomal disorder, Aneuploidy, Genomic conflict, Sexual difference

Introduction

Klinefelter syndrome (KS; 47,XXY karyotype and variants) is somatically and behaviorally characterized by a marked variation in severity of the phenotype (1,2). KS is the most common chromosomal aberration in men with 0.1-0.2 % of the male population affected (3-5). It has been proposed that besides gene-environment interactions specific genetic factors may contribute to the phenotypic variability in KS, including preferential X-inactivation patterns and the parent-of-origin of the supernumerary X-chromosome (6,7,8).

The parent-of-origin might influence the KS phenotype via differential expression of paternal vs. maternal X-alleles, i.e. parental imprinting (7,9). In contrast to other trisomies that originate from errors at maternal meiosis, KS is a notable exception as nearly onehalf of the cases derive from paternal non-disjunction (10). Therefore, KS could be an interesting condition to study imprinting effects through the assessment of parent-of-origin effects of the extra X chromosome. The multiple neurodevelopmental and behavioral difficulties observed in KS could be due to the disproportionally high number of genes on the X chromosome that are involved with mental function (11-13). Men with KS often present with language based learning problems, cognitive dysfunction and social difficulties (1,14,15). These problems are accompanied by an increased vulnerability to a wide range of psychiatric disorders in some, but not all, men with KS (16-20). This wide variability in psychiatric morbidity could enhance the chance of detecting parent-of-origin effects on psychopathology in KS. Behavioral studies in KS have shown an increased prevalence of autistic and schizotypal traits, in some cases to the level of autism and schizophrenia (16,18,21,22). Therefore, KS is an interesting condition to study X-linked imprinting effects on autistic and psychotic symptomatology in subjects with the same genetic disorder.

The role of epigenetic mechanisms such as genomic imprinting in psychiatric pathogenesis is an evolving theme. Probably the most studied example of imprinted genes in psychiatric disease is the 15q11-13 region. The Prader-Willi (PWS) and Angelman (AS) syndromes are clinically distinct developmental disorders with frequent psychotic and autistic symptoms respectively which are caused by genetic defects in the imprinted domain at chromosome 15q11-q13, resulting in the loss of paternal (PWS) or maternal (AS) gene function (23,24). Crespi et al. have proposed that autistic and psychotic disorders represent opposing imprinted conditions (25-27). They suggest that the etiologies of psychotic spectrum conditions commonly involve genetic and epigenetic imbalances in the effects of imprinted autosomal genes, with a bias towards increased relative effects of maternally-expressed imprinted genes. In contrast, they hypothesize that autistic spectrum conditions are associated with increased relative effects of paternally-expressed imprinted genes.

With respect to X chromosomal genes, no clear imprinting effects have been described in humans. Skuse et al. have proposed that the parent-of-origin of the X-chromosome in monosomy X (Turner syndrome, TS) impacted performance on measures of social cognition with better performance by females with paternally derived X chromosomes (28). Earlier studies have assessed parent-of-origin effects on language and cognition in KS. Speech and language impairments were found to be more pronounced in subjects with paternal origin of the extra X chromosome in one study (7) whereas parent-of-origin effects, using similar measures, were not observed in other studies (29-31). In addition, a previous study did not show a parent-of-origin effect on the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in a sample of 20 adult men with KS, including psychosis (17).

The goal of the present study was to assess whether the parent-of-origin contributes to the variability of autistic and schizotypal symptomatology in subjects with KS. Autistic and schizotypal trait scores were analyzed separately. We assessed both parent-of-origin group differences in each set of trait scores and feasibility of utilizing trait scores to discriminate parent-of-origin groups. Data on trait scores were available from two previous studies. Autistic traits had been assessed in a sample of boys and adolescents (here referred to as the younger sample) with KS in an earlier survey on developmental psychopathology (18). Schizotypal traits in a sample of adolescents and adults with KS (here referred to as the older sample of adults) were available through an earlier study on schizophrenia spectrum symptomatology (21).

Methods

The Dutch Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects had approved the research protocols. Written informed consent was obtained according to the declaration of Helsinki. The current samples were extracted from larger samples recruited as part of a larger research program that studies the neurobehavioral consequences of KS. Both samples had been recruited via the Dutch Klinefelter association and two centers for clinical genetics and pediatrics situated in the centre of the Netherlands A newsletter encouraged to participate regardless of any problems present (for further recruitment details (see (18,21)). Exclusion criteria for both Klinefelter samples and controls were neurological conditions that impair speech and motor development (other than through KS) or a history of head injury with loss of consciousness, recent history of substance abuse and intellectual disability (IQ < 70). There were no mosaic forms of KS among the participants, all had the full 47,XXY karyotype.

Subjects

The younger KS sample consisted of 33 subjects with KS (mean age 12.0 yrs, SD 3.6, range 6-19 yrs). Determination of parent-of-origin of the extra X chromsome in this sample showed that in 19 subjects the extra X chromosome originated from the mother (maternal group) and in 14 subjects from the father (paternal group). Age was significantly higher in the maternal group than in the paternal group of the younger sample (p = 0.03, t-test). At the time of the assessment 8 younger subjects were treated with testosterone (3 from the maternal group, 5 from the paternal group). Total IQ scores did not differ between maternal and paternal groups (p=0.54, t-test).

Measures of autistic traits in the younger sample were compared to a control sample of 29 healthy siblings (14 females, 15 males) of patients with velocardiofacial syndrome (22q11 DS) children, ranging in age from 9 to 19 (mean=14.1; SD=2.5). This sample originated from a study of phenotypes in individuals with velocardiofacial syndrome with and without autism (32). These subjects were older (p = 0,01, t-test) than the KS subjects in the younger sample.

The older sample consisted of 43 subjects (mean age 31.1 , SD 14.4, range 10-68 years ). This sample was part of prior sample that had been recruited for a study into schizophrenia spectrum pathology (21). Determination of parent-of-origin of the extra X chromosome in this sample showed that in 25 subjects the extra X chromosome originated from the mother (maternal group) and in 18 subjects from the father (paternal group). At the time of assessment, 15 men (60%) from the maternal group and 11 (61%) from the paternal group were treated with testosterone supplements. Age and total IQ scores did not differ between maternal and paternal groups group (p=0,42 and p=0,38 respectively, t-test).

The older sample was compared with a normal control sample that was recruited using advertisements in local newspapers or were drawn from a database in our department. None of the control subjects had a history of psychiatric illness as confirmed with the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview plus (MINI) (33). Mean age did was not different between adults with KS and controls (p=0.12, t-test).

Table 1 shows the basic characteristics of the younger and older sample.

Table 1.

Age and total IQ score (TIQ) in the younger and older Klinefelter Syndrome (KS) samples. Maternal = maternal origin, Paternal = paternal origin of extra X-chromosome. M vs P gives p values for t-test comparisons of maternal origin versus paternal origin group comparisons.

| Younger KS sample | Older KS sample | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | Maternal | Paternal | M vs P | Controls | Maternal | Paternal | M vs P | |

| n | 29 | 19 | 14 | 75 | 25 | 18 | ||

| Age ± SD | 14.1 ± 2.6 | 10.5 ± 2.9 | 14.1 ± 3.4 | 0.03 | 26.7 ± 14.9 | 37.2 ± 15.7 | 28.9 ± 12.5 | 0.42 |

| TIQ ± SD | 102.3 ± 16.7 | 81.8 ± 14.1 | 79 ± 12.1 | 0.54 | na | 90.9 ± 9.5 | 87.8 ± 14.8 | 0.38 |

All 12 adolescents of the older sample (i.e. those subjects under age 18.0 years) were also part of the younger sample. Furthermore, 61 subjects out of the current samples took part in a study that evaluated parent-of-origin effects on IQ, psychomotor development and growth in boys and men with KS (7).

Determination of parent-of-origin

Technical details regarding the determination of parent-of-origin are stated in the supplemental information.

Measure

Autistic traits

ASD traits in the younger sample were measured by the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) (34). The ADI–R is an established ‘gold standard’ for assessing a categorical diagnosis of autism, but may also be used to assess profiles of autistic symptomatology (32,35). It is an extensive clinical interview administered to the parents. The interview consists of three core or so called ‘content’ domains of autism (i.e. qualitative abnormalities in social interaction (S), qualitative abnormalities in communication (C) and stereotyped and repetitive behaviors (R) (34). The ADI-R measures autistic behaviors that are called items. The ADI–R algorithm contains a total 37 items. The ADI-R Diagnostic Algorithm that measures behaviors between the age of 4.0-5.0 years old was used in the present study, i.e. not the ADI-R Current Behavior Algorithm. The ADI-R items within each core domain are grouped into ADI-R labels (or sub-domains). Each ADI-R domain consists of 4 labels (e.g. S1-4, C1-4 and R1-4), and each label consists of 2 to 5 items, which are directly related to the DSM-IV-TR criteria of an Autistic Disorder. Items are scored as 0 (ASD behavioral symptom specified not present), 1 (specified behavior not sufficient to code “2”) or 2 (specified ASD symptom present). Maximum label scores thus range from 4–10.

The ADI-R may also be used to assess profiles of autistic symptomatology (32,35). The 3 ADI-R domain scores and 12 ADI-R label scores were entered in the current analyses as autistic traits. An overview of the description of the ADI-R items, labels and the ADI-R domains of the algorithm is provided in Table S1 (see Supplement). Table S2 (see Supplement) states the individual ADI-R algorithm items sorted by labels and domains.

Schizotypal traits

The older sample was investigated for schizotypal traits through the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire (SPQ) questionnaire (36). The SPQ is a self-report measure of schizotypal traits, which has been shown to be normally distributed in the general population. Factor analytical studies have revealed three dimensions of schizotypy, being (a) Positive schizotypy (for example referential thinking and delusional atmosphere), (b) Negative schizotypy (for example constricted affect and social anxiety), and (c) Disorganization (odd speech and eccentric behavior) (37). These three dimensions are clusters of traits derived from 10 individual SPQ labels, which are assigned to the clusters according to the analyses of Vollema et al. Total score for each label is based on a range of questions that are answered with ‘yes’ (one point) or ‘no’ (zero points). The SPQ is regarded as a sensitive instrument to measure subclinical schizophrenia-like traits or symptoms (38).

Statistical analysis

Multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA) with parent-of-origin as between subjects factor (normal controls, maternal KS, paternal KS) and ADI-R domain and label scores as dependent variables, respectively, were performed to test differences between groups on ASD traits. Similar MANOVAs as for autistic measures above were performed with SPQ dimension and label scores as dependent variables, respectively. A Helmert contrast was applied to compare the controls with the total KS samples (contrast 1) and the maternal KS sample with the paternal KS sample (contrast 2) in one run. Partial eta squared (ηp2) indicates effect sizes, with ηp2 ~ 0.03 representing a weak effect, ηp2 ~ 0.06 representing a moderate effect and ηp2 ≥ 0.14 representing a large effect (39). Whereas MANOVA was used to test differences between group means, discriminant analysis (DA), direct method, was used to evaluate to what extent autistic and schizotypal trait scores could differentiate on the individual level between the maternal and paternal younger and older subsamples. For classification the within-group covariance matrices were used and prior probability was set to equal for all groups. The success of the predictive ability of the ADI-R domain/label and SPQ dimension/label scores for parent-of-origin is reflected in the classification matrix that shows the number and percentage of correctly identified subjects.

The threshold for significance in the analyses was set at p=0.05.

Results

Parent-of-origin and autistic symptoms

First, our main hypothesis was tested, whether the parent-of-origin groups differed in the degree of autistic trait scores. Age and testosterone treatment were irrelevant to the outcome of autistic ADI-R scores as these were measured according to the ADI-R algorithm, which assesses behaviors between age 4.0-5.0 years.

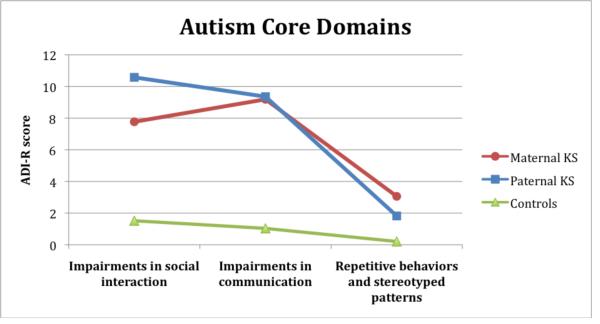

The multivariate effect of group on the ADI-R domain scores was significant [F(6,116)=11.27, p<.0001, ηp2=.368], with univariate F-tests significant for all domains (p<.0001 and ηp2≥.407). The 1st contrast (controls vs. total KS sample) revealed significant differences for all domains (p<.0001). The 2nd contrast (maternal vs. paternal KS) revealed no significant differences (p≥.054). Figure 1 indicates that the paternal group scores higher than the maternal group on the domains of impairments in social interaction (S) and impairments in communication (C), while on the domain of repetitive and stereotyped behaviors (R) the maternal group scores higher. No domain differences reached significance, though differences in domain S approached significance (p = .054).

Figure 1.

Average ADI-R domain scores for parent-of-origin groups in the younger KS sample versus controls. The 3 domains have different scoring ranges as they consist of 15, 13 and 6 items respectively.

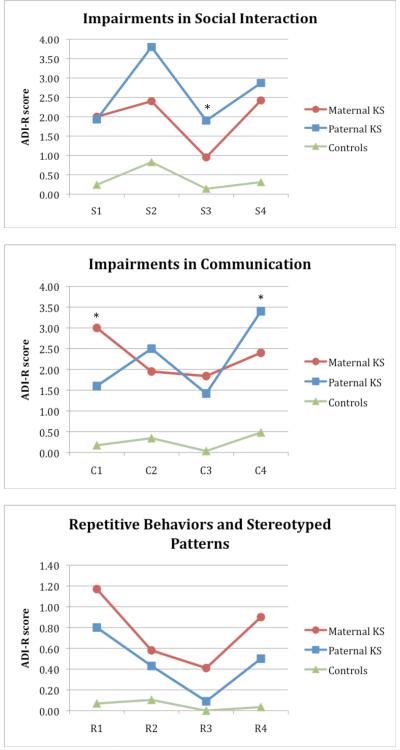

The multivariate effect of group on the ADI-R labels scores was significant [F(24,98)=4.56, p<.0001, ηp2=.528], with univariate F-tests significant for all labels (p<.0001 and ηp2≥.268) for all labels except R2 (p=.038, ηp2=.105) and R3 (p=.020, ηp2=.125). The 1st contrast (controls vs. total KS sample) revealed significant differences for all labels except R3 (p=.055). Significance levels reached p<.0001 for all other labels except R2 (p=.02). The 2nd contrast (maternal vs. paternal KS) revealed that paternal KS subjects scored higher on S3 (Lack of shared enjoyment) (p=.018) and C4 (p=.043) (Stereotyped, repetitive or idiosyncratic speech), whereas maternal KS subjects scored significantly higher (i.e., showed great impairment) on C1(Lack of, or delay in, spoken language and failure to compensate through gesture) (p=.016). Figure 2 gives an overview of the ADI-R label scores.

Figure 2.

Average ADI-R label scores for different parent-of-origin groups in the younger KS sample. * = p < 0.05, Helmert contrast analyses of maternal vs. paternal group scores.

Discriminant analysis involving the ADI-R domains (Wilks’ lambda =.741, χ2(3)=8.83, p=.032) resulted in a correct classification of 78.9% of the members of the maternal group and 78.6% of the members of the paternal group, misdiagnosing four and three subjects per group, respectively.

Discrimination analysis involving the ADI-R labels resulted (Wilks’ lambda =.397, χ2(12)=23.11, p=.027) in an correct classification of no less than 94.7% of the members of the maternal group and 92.7% of the members of the paternal group, only misdiagnosing one subject in each group.

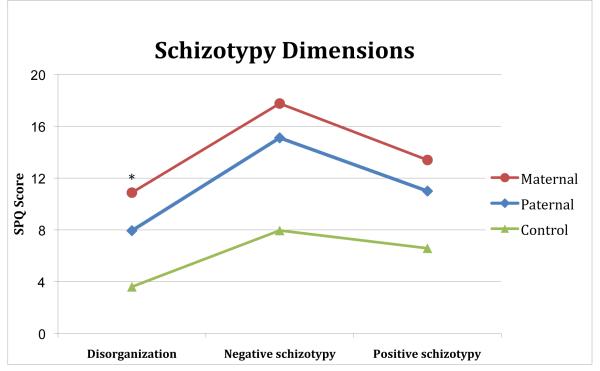

Parent-of-origin origin and schizotypal symptom profiles

As part of our main hypothesis, we further tested whether the parent-of-origin subgroups differed in schizotypal trait scores. Testosterone treatment did could not explain group effects on total schizotypal scores in the older sample (Mann-Whitney test: 60% of maternal subjects versus 61% paternal subjects receiving treatment, Z=−0.09, p=0.92). The multivariate effect of group (maternal vs. paternal vs. controls) on the SPQ main dimension scores was significant [F(6.228)=7.9303, p<.0001, ηp2=.173], indicating that the groups comprising the older sample differed in schizotypal dimension scores.

The univariate between subjects effects were significant for all dimensions with p varying between <.0001 (ηp2=.33) and .001 (ηp2=.118), with the maternal group scoring highest and the controls scoring lowest on all dimensions (see figure 3). The first difference contrast (KS vs. controls) showed significantly higher scores for the total KS sample on all SPQ dimension (p≤.004). The second difference contrast (maternal vs. paternal group) showed a significant difference for the dimension Disorganization (p=.032), but not for the other two dimensions (Positive/Negative schizotypy, p=.33).

Figure 3.

SPQ dimension scores for the parent-of-origin groups in the older KS sample. * = p < 0.05, Helmert contrast analyses of maternal vs. paternal group scores.

The same significant multivariate effect of group (maternal vs. paternal vs. controls) held for individual SPQ labels [F(20.214)=4.03, p<.0001, ηp2=.273], indicating that the groups differed in scores. The univariate between subjects effects were significant for all labels, except for Delusional ideas (p =.16), with p varying between <.0001 (ηp2=.355) to <.016 (ηp2=.070). The first difference contrast (KS vs. controls) showed significantly higher scores for the total KS sample on all SPQ labels with p ≤.005, except for Delusional ideas (p =.06), and Magical thinking (p =.022). The second and most important difference contrast (maternal group vs. paternal group) showed a trend toward significance for Magical thinking (p =.094), and significant differences on Excessive social anxiety (p =.049) and Odd or eccentric behavior (p =.010), with maternal scores scoring higher than paternal scores on 8 out of 10 subscales, an equal score for delusional ideas and a marginally lower score for ideas of reference (see Figure S1 in the Supplement).

Discriminant analysis involving the SPQ labels resulted in a correct classification of 80.0 % of the members of the maternal group and 77.8% of the members of the paternal group, misdiagnosing only five (out of 25) and four (out of 18) subjects per group, respectively.

Discussion

This study is the first to describe parent-of-origin effects on psychopathology in KS. The results show that the parent-of-origin of the extra X chromosome is reflected in the level of autistic symptoms and schizotypal traits. Multivariate effects of group (maternal vs. paternal vs. controls) on both schizotypal and autistic traits were found, indicating that the parent-of-origin groups differed in scores on both traits. Furthermore, significant differences on individual schizotypal and autistic trait scores were shown between maternal and paternal groups. The significantly higher scores on schizotypal traits were consistently associated with maternal origin. The significant differences in autistic traits were not consistent. One was associated with maternal origin and others with paternal origin. Further analysis revealed that the parent-of-origin of the extra X chromosome could be discriminated through specific autistic and schizotypal trait profiles. Over 90% correct classification of parental groups was feasible on the basis of the autistic trait profile in the younger sample and around 80% correct classification of the parental groups on the basis of the schizotypal profile in the older sample. Our results indicate that parent-of-origin effects on autistic and psychotic psychopathology exist, but further conclusions are precluded until other studies have provided evidence of similar imprinting effects.

Both the autistic and schizotypal measurements did not seem to be influenced by age. However, recall bias in the retrospective ADI-R interview might be greater in older subjects due to longer time passed since the 4-5 yrs age period used to measure behaviors especially if testosterone treatment at a later age has influenced behaviors. A relative strength is that we showed imprinting effects in two different largely independent samples. In comparison to other studies on KS our sample sizes were substantial but seem underpowered for more detailed comparisons.

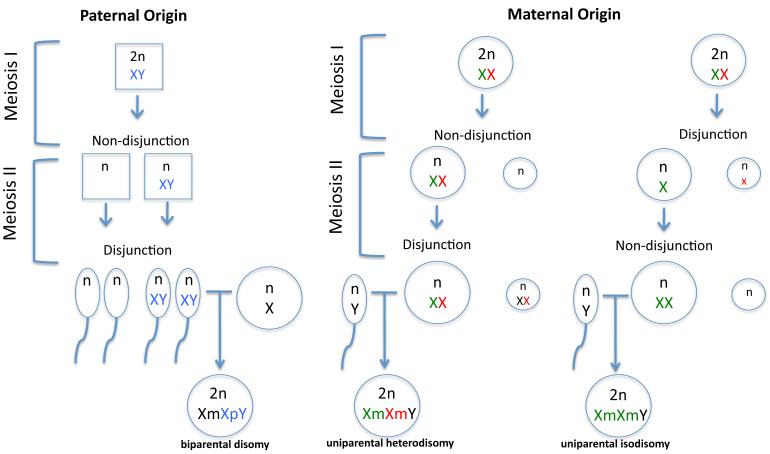

It should be noted that maternal non-disjunction during meiosis I leads to uniparental heterodisomy (two different X chromosomes from the same parent, in this case the mother), while an error during meiosis II results in uniparental isodisomy (duplicate of one maternal X chromosome in the child) (Figure 4). In our samples, we were able to determine the phase of meiotic non-disjunction in 29 of the total 44 maternal subjects. Evaluation of the androgen receptor polymorphic allelic differences showed heterodisomy in 15 cases and uniparental isodisomy in 14 cases. These numbers were too small for further comparisons, but the hetero- vs. isodisomic nature of the extra X chromosomes could also be of influence on the KS phenotype which would add another level of complexity in assessing parent-of-origin effects in KS.

Figure 4.

Different errors during gametogenesis leading to KS. Maternal origin is due to uniparental heterodisomy (two different X chromosomes from the same parent) via non-disjunction in Meiosis I or uniparental isodisomy (duplicate of one maternal X chromosome) via non-disjunction in meiosis II. Paternal origin is due to biparental disomy via non-disjunction in meiosis I (one paternal and one maternal X chromosome). Smaller round structures next to oocytes and ovums in female meioses designate first and second polar bodies.

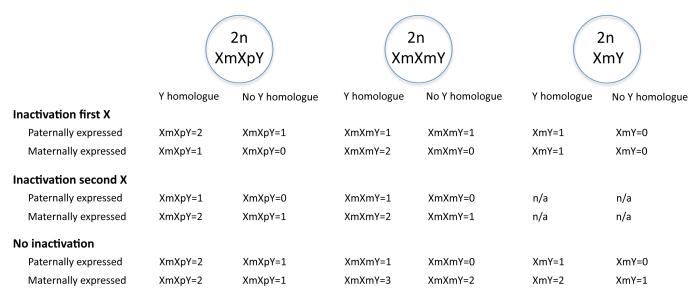

It is not known whether in turn, the parent-of-origin influences the complex gene dosage and inactivation patterns in KS. It has been well documented that 15 % of the human X-linked genes are known to stably escape inactivation and 10% of genes have a heterogeneous expression, i.e. these genes are inactivated in certain women and expressed on the inactive X chromosome in others (40). These findings suggest that genes that escape inactivation as well as those within pseudoautosomal regions (i.e. the homologous DNA sequences of nucleotides on the X and Y chromosomes) are likely to cause gene dosage differences in KS. Analogous to a figure depicting X chromosomal gene dosage in euploidic individuals by Davies et al (41), figure 5 depicts the possible relationships between imprinting status and X-inactivation in KS.

Figure 5.

Theoretical genes dosages for X-linked imprinted genes in different parent-of-origin forms of KS and euploidic males, depending upon their direction of imprinting, X-inactivation status, and the presence or not of a functionally equivalent Y homologue. In the example of XmXpY, Xm is the “first” X-chromosome, Xp is the “second” X-chromosome. For instance, “Paternal expression” and “Inactivation of the second X” for XmXpY results in an active (first) Xm which is not expressed when paternal genes are preferentially expressed, thus gene dosage =1 when a homologues gene can be expressed from the Y chromosome, and gene dosage = 0 when there is no Y homologues gene. Figure is analogous to a figure depicting X chromosomal gene dosage in euploid individuals by Davies et al. (41).

It has been speculated that elevated expression of X-linked genes in KS cause a liability for psychosis rather than ASD (20). This is mainly based upon the observation of similar deficits in verbal cognition and brain anatomy in both KS and schizophrenia (42,43). Crespi et al described that Klinefelter syndrome (usually 47,XXY) should involve high rates of psychotic spectrum disorders, whereas Turner syndrome (usually 45,X) should involve a higher incidence of autism (25,26). In our earlier psychiatric survey of 51 boys with KS we did find high frequencies of both ASDs and psychosis (18). It is possible that particular social-cognitive deficits in KS present differently at different ages. It could be that the developmental window in which they are assessed influences diagnoses (26). Of the current younger sample, 11 subjects had been diagnosed with an ASD in the original psychiatric survey. Six of these were in the maternal group and 5 in the paternal group. Three of these ASD subjects had also had suffered from at least one psychotic episode all of which had a maternal origin of the extra X chromosome. This might be in accordance with the maternal effect on schizoptypal traits that we observed in the older sample. The number of subjects in our study that were assessed for both schizotypal and autistic traits was underpowered for further comparisons. Future studies should aim to investigate whether a possible overlap in KS of autistic and psychotic spectrum psychopathology can be (partly) dissected through the parent-of-origin.

Not much is known about X linked imprinting effects in humans as opposed to effects of imprinting through autosomal genes. It has been suggested that X-linked imprinting may serve as a mechanism for the evolution of sexual dimorphism in humans, given that gene dosages of X-linked imprinted genes are expected to differ between the sexes (26,28). Traits encoded by paternally expressed X-linked genes can exhibit more qualitatively or bidirectionally distinct expression in male (XmY) and female progeny (either XmXp or XmXm), i.e. absent in males, present in females. In contrast, the phenotypic difference between male and female offspring for maternally encoded traits may be quantitative, i.e. a unidirectional effect (41). It could be interesting to compare our results to the parent-of-origin effects described in Turner syndrome, monosomy X. By Skuse’s hypothesis, i.e. in analogy to, XmO (maternal origin) and XpO (paternal origin) individuals in TS, XmXmY (maternal origin) Klinefelter patients might be expected to show more male-typical traits, compared to XmXpY (paternal origin) patients (28,44). To our knowledge, no studies have found autistic trait differences between autistic males and females. Two recent studies that measured schizotypal traits in large samples of normal individuals showed that negative symptoms are more pronounced in males, while positive scales tend to be higher in females (45,46). These findings and our maternal imprinting association with positive schizotypy scales do not suggest more male like traits in XmXmY individuals. In different mammalian species including mice, paternal X-chromosomal alleles are silenced in the extraembryonic tissue that constitutes the later placenta during development (47-49). Interestingly, mouse embryos carrying supernumerary X chromosomes of maternal origin have shown reduced placental growth (50,51). It is yet unclear if and to what extent preferential paternal X-chromosomal inactivation takes place in the human placenta (52,53). In the unusual human situation of XmXmY KS individuals, it might be possible that gene dosage effects are more pronounced in the fetal placenta through preferential paternal X chromosomal silencing. Maternal origin in KS could perhaps also result in reduced placental growth with more reduced brain growth and an increased susceptibility for psychosis analogous to the theories postulated by Badcock and Crespi for autosomal imprinting effects on psychosis and autism (27). This would contrast the situation in XmXpY men in which normal Xp silencing should occur in the fetal component of the placenta. Perhaps of interest in this respect, Lahti et al. described lower placental weight, lower birth weight and smaller head circumference at 12 months predicted elevated positive schizotypal traits in women after adjusting for several confounders (p<0.02) (53). Further gene dosage effects in the (developing) brain should explain the enhanced susceptibility for psychosis and/or ASD in KS also present among XmXpY individuals. Recent studies on (sex-specific) parent-of-origin allelic gene expression in the mouse brain in mice underscore the possibility that X chromosomal gene dosage differences of different parental origins are likely to cause differential effects in brain function (54,55).

In conclusion, it seems that the parent-of-origin of the extra X chromosome in KS may have a differential effect on autistic and schizotypal profiles in KS. KS could be a promising condition to further research X-linked imprinting effects on different psychopathologies. Such epigenetic knowledge could help to find the missing heritability in complex psychiatric disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Ben Oostra for his assistance on the manuscript. The research reported in this paper was partially supported by NIH/NIMH MH64824 to Dr. Kates.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: Dr Kates discloses that she is involved in a separate research study supported by Aton Pharma. All other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Reference List

- 1.Geschwind DH, Boone KB, Miller BL, Swerdloff RS. Neurobehavioral phenotype of Klinefelter syndrome. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2000;6:107–116. doi: 10.1002/1098-2779(2000)6:2<107::AID-MRDD4>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lanfranco F, Kamischke A, Zitzmann M, Nieschlag E. Klinefelter’s syndrome. Lancet. 2004;364:273–283. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16678-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bojesen A, Juul S, Gravholt CH. Prenatal and postnatal prevalence of Klinefelter syndrome: a national registry study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:622–626. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris JK, Alberman E, Scott C, Jacobs P. Is the prevalence of Klinefelter syndrome increasing? Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16:163–170. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nielsen J, Wohlert M. Chromosome abnormalities found among 34,910 newborn children: results from a 13-year incidence study in Arhus, Denmark. Hum Genet. 1991;87:81–83. doi: 10.1007/BF01213097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iitsuka Y, Bock A, Nguyen DD, Samango-Sprouse CA, Simpson JL, Bischoff FZ. Evidence of skewed X-chromosome inactivation in 47,XXY and 48,XXYY Klinefelter patients. Am J Med Genet. 2001;98:25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stemkens D, Roza T, Verrij L, Swaab H, van Werkhoven MK, Alizadeh BZ, et al. Is there an influence of X-chromosomal imprinting on the phenotype in Klinefelter syndrome? A clinical and molecular genetic study of 61 cases. Clin Genet. 2006;70:43–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuttelmann F, Gromoll J. Novel genetic aspects of Klinefelter’s syndrome. Mol Hum Reprod. 2010;16:386–95. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaq019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs PA, Hassold TJ, Whittington E, Butler G, Collyer S, Keston M, et al. Klinefelter’s syndrome: an analysis of the origin of the additional sex chromosome using molecular probes. Ann Hum Genet. 1988;52:93–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1988.tb01084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas NS, Hassold TJ. Aberrant recombination and the origin of Klinefelter syndrome. Hum Reprod Update. 2003;9:309–317. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmg028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jazin E, Cahill L. Sex differences in molecular neuroscience: from fruit flies to humans. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:9–17. doi: 10.1038/nrn2754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen DK, Disteche CM. High expression of the mammalian X chromosome in brain. Brain Res. 2006;1126:46–49. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skuse DH. X-linked genes and mental functioning. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14 Spec No 1:R27–R32. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boada R, Janusz J, Hutaff-Lee C, Tartaglia N. The cognitive phenotype in Klinefelter syndrome: a review of the literature including genetic and hormonal factors. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2009;15:284–294. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Visootsak J, Graham JM., Jr. Social function in multiple X and Y chromosome disorders: XXY, XYY, XXYY, XXXY. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2009;15:328–332. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bojesen A, Juul S, Birkebaek NH, Gravholt CH. Morbidity in Klinefelter syndrome: a Danish register study based on hospital discharge diagnoses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1254–1260. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boks MP, de Vette MH, Sommer IE, van RS, Giltay JC, Swaab H, et al. Psychiatric morbidity and X-chromosomal origin in a Klinefelter sample. Schizophr Res. 2007;93:399–402. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruining H, Swaab H, Kas M, van Engeland H. Psychiatric characteristics in a self-selected sample of boys with Klinefelter syndrome. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e865–e870. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeLisi LE, Maurizio AM, Svetina C, Ardekani B, Szulc K, Nierenberg J, et al. Klinefelter’s syndrome (XXY) as a genetic model for psychotic disorders. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;135B:15–23. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeLisi LE, Friedrich U, Wahlstrom J, Boccio-Smith A, Forsman A, Eklund K, et al. Schizophrenia and sex chromosome anomalies. Schizophr Bull. 1994;20:495–505. doi: 10.1093/schbul/20.3.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Rijn RS, Aleman A, Swaab H, Kahn R. Klinefelter’s syndrome (karyotype 47,XXY) and schizophrenia-spectrum pathology. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:459–460. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.008961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Rijn RS, Swaab H, Aleman A, Kahn RS. Social behavior and autism traits in a sex chromosomal disorder: Klinefelter (47XXY) syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38:1634–1641. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0542-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schanen NC. Epigenetics of autism spectrum disorders. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15 Spec No 2:R138–R150. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Veltman MW, Craig EE, Bolton PF. Autism spectrum disorders in Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes: a systematic review. Psychiatr Genet. 2005;15:243–254. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200512000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Badcock C, Crespi B. Imbalanced genomic imprinting in brain development: an evolutionary basis for the aetiology of autism. J Evol Biol. 2006;19:1007–1032. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crespi B. Genomic imprinting in the development and evolution of psychotic spectrum conditions. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2008a;83:441–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2008.00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crespi B, Badcock C. Psychosis and autism as diametrical disorders of the social brain. Behav Brain Sci. 2008;31:241–261. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X08004214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ross JL, Roeltgen DP, Stefanatos G, Benecke R, Zeger MP, Kushner H, et al. Cognitive and motor development during childhood in boys with Klinefelter syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:708–719. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeger MP, Zinn AR, Lahlou N, Ramos P, Kowal K, Samango-Sprouse C, et al. Effect of ascertainment and genetic features on the phenotype of Klinefelter syndrome. J Pediatr. 2008;152:716–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zinn AR, Ramos P, Elder FF, Kowal K, Samango-Sprouse C, Ross JL. Androgen receptor CAGn repeat length influences phenotype of 47,XXY (Klinefelter) syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:5041–5046. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kates WR, Antshel KM, Fremont WP, Shprintzen RJ, Strunge LA, Burnette CP, et al. Comparing phenotypes in patients with idiopathic autism to patients with velocardiofacial syndrome (22q11 DS) with and without autism. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:2642–2650. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lord C, Rutter M, LeCouteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1994;24:659–685. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brune CW, Kim SJ, Salt J, Leventhal BL, Lord C, Cook EH., Jr. 5-HTTLPR Genotype-Specific Phenotype in Children and Adolescents With Autism. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:2148–2156. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raine A. The SPQ: a scale for the assessment of schizotypal personality based on DSM-III-R criteria. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17:555–564. doi: 10.1093/schbul/17.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vollema MG, Hoijtink H. The multidimensionality of self-report schizotypy in a psychiatric population: an analysis using multidimensional Rasch models. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:565–575. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vollema MG, Postma B. Neurocognitive correlates of schizotypy in first degree relatives of schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28:367–377. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stevens J. Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; London: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carrel L, Willard HF. X-inactivation profile reveals extensive variability in X-linked gene expression in females. Nature. 2005;434:400–404. doi: 10.1038/nature03479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davies W, Isles AR, Burgoyne PS, Wilkinson LS. X-linked imprinting: effects on brain and behaviour. Bioessays. 2006;28:35–44. doi: 10.1002/bies.20341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Itti E, Gaw G, I, Pawlikowska-Haddal A, Boone KB, Mlikotic A, Itti L, et al. The structural brain correlates of cognitive deficits in adults with Klinefelter’s syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1423–1427. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vawter MP, Harvey PD, DeLisi LE. Dysregulation of X-linked gene expression in Klinefelter’s syndrome and association with verbal cognition. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B:728–734. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crespi BJ. Turner syndrome and the evolution of human sexual dimorphism. Evolutionary Applications. 2008b;1:449–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2008.00017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bora E, Baysan AL. Confirmatory factor analysis of schizotypal personality traits in university students. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. :339–345. (209) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fonseca-Pedrero E, Lemos-Giraldez S, Muniz J, Garcia-Cueto E, Campillo-Alvarez A. Schizotypy in adolescence: the role of gender and age. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196:161–165. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318162aa79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takagi N, Sasaki M. Preferential inactivation of the paternally derived X chromosome in the extraembryonic membranes of the mouse. Nature. 1975;256:640–642. doi: 10.1038/256640a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wake N, Takagi N, Sasaki M. Non-random inactivation of X chromosome in the rat yolk sac. Nature. 1976;262:580–581. doi: 10.1038/262580a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xue F, Tian XC, Du F, Kubota C, Taneja M, et al. Aberrant patterns of X chromosome inactivation in bovine clones. Nat Genet. 2002;31:216–220. doi: 10.1038/ng900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moore T, McLellan A, Wynne F, Dockery P. Explaining the X-linkage bias of placentally expressed genes. Nat Genet. 2005;37:3–4. doi: 10.1038/ng0105-3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tada T, Takagi N, Adler ID. Parental imprinting on the mouse X chromosome: effects on the early development of X0, XXY and XXX embryos. Genet Res. 1993;62:139–148. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300031736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zeng SM, Yankowitz J. X-inactivation patterns in human embryonic and extra-embryonic tissues. Placenta. 2003;24:270–275. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Mello JC Moreira, Araújo ÉSSd, Stabellini R, Fraga AM, Souza JESd, et al. Random X Inactivation and Extensive Mosaicism in Human Placenta Revealed by Analysis of Allele-Specific Gene Expression along the X Chromosome. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(6):e10947. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lahti J, Raikkonen K, Sovio U, Miettunen J, Hartikainen AL, Pouta A, et al. Early-life origins of schizotypal traits in adulthood. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195:132–137. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.054387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gregg C, Zhang J, Weissbourd B, Luo S, Schroth GP, Haig D, et al. High-resolution analysis of parent-of-origin allelic expression in the mouse brain. Science. 2010;329:643–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1190830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gregg C, Zhang J, Butler JE, Haig D, Dulac C. Sex-specific parent-of-origin allelic expression in the mouse brain. Science. 2010;329:682–685. doi: 10.1126/science.1190831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.