Abstract

As the repertoire of αβT cell receptors (TCR) contracts with advancing age, there is an associated age-dependent accumulation of oligoclonal T cells expressing of a variety of receptors (NKR), normally expressed on natural killer (NK) cells. Evidences for differential regulation of expression of particular NKRs between T cells and NK cells suggest that NKR expression on T cells is physiologically programmed rather than a random event of the aging process. Experimental studies show NKRs on aged αβT cells may function either as independent receptors, and/or as costimulatory receptors to the TCR. Considering the reported deficits of conventional αβTCR-driven activation and also functional deficits of classical NK cells, NKR+ αβT cells likely represent novel immune effectors that are capable of combining innate and adaptive functions. Inasmuch as immunity is a determinant of individual fitness, the type and density of NKRs could be important contributing factors to the wide heterogeneity of health characteristics of older adults, ranging from institutionalized frail elders who are unable to mount immune responses to functionally independent community-dwelling elders who exhibit protective immunity. Understanding the biology of NKR+ αβT cells could lead to new avenues for age-specific intervention to improve protective immunity.

Keywords: CD16, CD56, immune effector, natural killer-related receptor, repertoire diversity

Introduction

T cells and natural killer (NK) cells are distinct lineages of lymphocytes that are traditionally defined as cellular mediators of adaptive and innate immunity, respectively. T cells are identified by the expression of an antigen-recognizing T cell receptor (TCR) composed of α and β (or γ and δ) polypeptides. Clonal lineages of T cells are identified by the unique TCR they express. In contrast, NK cells are classically defined by the expression of non-antigen recognizing, monomorphic receptors CD16 (also known as FcγRIIIA or Leu-11) and CD56 (also known as NCAM or Leu-19). Unless deliberately generated in vitro, NK cell clones are not readily identified by the expression of particular cell surface markers. NK cell lineages may only be tracked by the sequencing of incompletely rearranged TCRA or TCRB transcripts (Pilbeam et al, 2008), presence of such transcripts is consistent with a common progenitor for NK cells and T cells (Benne et al, 2009).

On the one hand, the αβTCR repertoire is highly diverse; most of the T cells found in secondary lymphoid organs are those generated in utero. Due to TCR gene rearrangements in the thymus, αβTCR diversity is immense. It is estimated to be at least 2.5 × 107 and up to a theoretical maximum of 1 × 1015; the average adult has about 1 × 1012 αβT cells in circulation (Arstila et al, 1999). But with the progressive postnatal degeneration of the thymus, and exposure to a vast universe of exogenous and endogenous antigens through life, αβTCR repertoire diversity contracts with age. For older adults aged ≥65 years, it has been reported that the overall αβTCR repertoire diversity is up to 1,000-fold less than that seen for younger persons (Naylor et al, 2005). This age-dependent reduction in repertoire diversity occurs in both the naïve and memory compartments. Thymic degeneration and depletion of the naïve pool accounts for the reduced naïve TCR diversity (Douek et al, 1998; Kilpatrick et al, 2008). Reduced memory TCR diversity may be explained by the selective expansion of clonotypes directed against persistent or cyclical pathogens (Hadrup et al, 2006; Pourgheysari et al, 2007; Naumova et al, 2009), and by overall clonal expansion of T cells of unknown specificities (Wack et al, 1998). It is noteworthy that T cell clonal expansion is also a characteristic of mice even for those reared in specific-pathogen free condition (Ku et al, 2001; Messaoudi et al, 2004; Yager et al, 2008) indicating that TCR repertoire contraction is a unique feature of the aging mammalian immune system.

On the other hand, overall repertoire diversity of NK-related receptors (herein referred to as “NKR”) has yet to be quantified, but it is likely to parallel that of TCR diversity. There is a very large superfamily of NKRs comprised of immunoglobulin (Ig)-like and C-type lectin receptors that are encoded in different chromosomes (Huntington et al, 2007; Barrow & Trowsdale, 2008). Some NKRs are activating (e.g. CD16, CD56, CD85b/c/e/f/g/i, CD158d/e2/j/k, NKG2C/D, and FcR), while others are inhibitory (e.g. CD94, CD85a/d/j, CD158a/b/c/e1/f/g/h/I, and NKG2A). In fact, some of the NKRs such as the CD158 family members (also known as killer cell Ig-like receptor, or KIR, family) are highly polymorphic (Bashirova et al, 2006). NKRs are generally expressed codominantly and in different combinations with CD16 and CD56; coexpression of activating and inhibitory receptors is thought to be important in fine-tuning NK cell responses (Cheent & Khakoo, 2009). Some NKRs, such as the NKG2, CD85, and CD158 families, have promiscuous recognition of class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC), and MHC class I-like molecules, suggesting antigen could also influence NK cell function (Eagle & Trowsdale, 2007; Middleton & Gonzelez, 2010). Whether or not overall NKR diversity in NK cells contracts with age remains to be examined. This would be an undertaking that will require complex permutations of analytical determination of the levels of expression of each NKR, and combinations thereof, in a defined cohort of subjects.

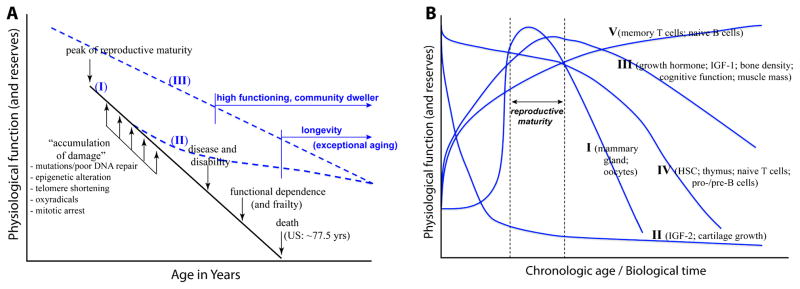

Functional alterations of conventional αβT cells and NK cells with aging: Biological examples of the Damage Paradigm of Aging

Aging is generally viewed as the decline of various physiological functions over time. In simplest terms, chronologically older organisms perform less efficiently than their younger counterparts. As to when and how aging commences is a subject of debate. A popular view however, is that aging pertains to individual survival after reproductive maturity. Figure 1A, graph I illustrates this view that various cells and tissues of humans (and mammals) are subject to progressive damage following reproductive maturity. Accumulation of such damage is thought to lead to disease and disability that progress to functional dependence or frailty, and ultimately to death. There are different forms of physiologic damage. Among the most studied are genomic instability due to either poor DNA repair and/or accumulating mutations (Hoeijmakers, 2009), oxidative stress (Salmon et al, 2010), telomere shortening and mitotic arrest (Sahin & DePinho, 2010), and depletion/defects of stem cell reserves (Geiger & van Zant, 2002).

Figure 1. Paradigms of Aging.

(A) The damage paradigm of aging (graph I) posits that the aging process and its outcomes are due to the accumulation of damage in various cells and organ systems over time. Examples of damage are genetic mutations, epigenetic dysregulation, telomere shortening, oxidative stress, and mitotic arrest. Accumulation of damage is thought to result in disease and disability, leading to frailty and ultimately death. As indicated, current human lifespan in the US has been estimated to be about 77.5 years (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2008). However, existence of large pockets of adults older than 78 years in the US and many countries could not be explained by the damage paradigm. Such lifespan extension is not simply a delay of the time of death, but extended years of favorable health and high level of individual function referred to as exceptional aging (Christensen et al, 2008). Considering that long life runs in families (Shoenmaker et al, 2006), exceptional aging and longevity suggest biological pathways are either elaborated in mid-life (graph II), or are genetically determined before birth (graph III) that might protect from the ill-effects of physiologic damage (see text for discussion). (B). In contrast to the damage paradigm that defines aging as individual survival after reproductive maturity, a developmental view of aging (Zwaan 2003; deMalgahaes and Church, 2005) posits that aging is part of the program of development beginning at birth and ending with death. It includes processes of deterioration, repair, and regeneration. Different organ-systems or physiologic functions undergo development and aging at different rates, at least five types of programs (I – V) are illustrated (see text for relevant discussion). Aging therefore occurs through the lifespan. Exceptional aging is not the absence of damage per se, but the capacity to retain function despite the damage in old age.

In the mammalian immune system, the damage paradigm of aging is thought to manifest as what is often referred to as “immunosenescence”. This phenomenon is loosely defined as the relatively poorer immune responses of older adults compared to those seen among younger individuals. In the context of infection and vaccination, immunosenescence is generally viewed as the progressive decline of antigen-specific immunity with age. In the T cell compartment therefore, contraction of αβTCR repertoire diversity with aging is the best example of immune damage. As noted earlier, the TCR repertoire is largely determined in utero, and its immense diversity is critical to host defense against a similarly diverse universe of pathogens, self-derived antigens, and environmental irritants.

In addition to TCR repertoire contraction, there is a large body of literature about a diminution in various aspects of T cell-mediated responses with advancing age consistent with the damage paradigm. A comprehensive review of such studies on age-related functional deficits of T cells is beyond the scope of this paper. However, a consensus finding is that aging is associated with an overall inefficiency of cell activation resulting from varying impairments of signal transduction from the TCR/CD3 complex (Cao et al, 2010) leading to various defects of classical T cell effector functions. Diminished formation of TCR/CD3 lipid rafts and reduced phosphorylation of TCR signaling intermediates have been shown to limit proliferation of aged T cells (Larbi et al, 2006; Henson et al, 2009; Chen et al, 2010). Consequently T cells of older adults have reduced antigen-specific cytotoxic and helper activities compared to T cells of younger people (Deng et al, 2004; Xie & McElhaney, 2007). There are also varying alterations in effector cytokine production by aged T cells, ranging from a complete lack of TCR/CD3-driven production of interleukin (IL)-2 to cases of paradoxical over production of interferon (IFN)-γ without TCR costimulation by CD28, the classic costimulator normally required to sustain activation of T cells in the young (Deng et al, 2004; Kang et al, 2004; Alberti et al, 2006; Pourgheysari et al, 2007).

Similar alterations of classical NK cells with aging have also been reported. A common observation is the contraction in the sizes of NK cell subsets as has been shown in various cohorts of adults aged ≥65 years that were selected using varying criteria of medical comorbidity relative to groups of younger healthy persons (Mariani et al, 1990; Erkeller-Yuksel et al, 1992; Ogata et al, 1997; Lin et al, 1998; Mocchegiani et al, 2003; Sundström et al, 2007). However, the degree of size contraction varies widely among study cohorts, and this could partly be related to the age definition of the elderly group under consideration. Many studies generally use 65 years as the low age limit for a single “older” test group that is compared with several younger groups. But because of heterogeneity of health and immune phenotypes of older adults (see discussion below), the usual young-versus-old group comparison may be an insufficient experimental approach. Thus, it will be of interest examine a large scale cross sectional cohort of subjects representing the entire human lifespan to determine the rate of size contraction of the NK cell compartment, and the extent to which other intrinsic biological factors such as race, sex, body size, and adiposity (Shahabuddin, 1995; Hodkinson et al, 2005; Caspar-Bauguil et al, 2006; Blum & Pabst, 2007) modifies it. Assessment of the NK compartment may also need to be examined in conjunction with assessment of other leukocyte subsets as NK cell numbers have been shown to be influenced by the proportions of other white blood cells (Reichert et al, 1991), an important consideration related to the overall homeostasis of leukocyte numbers that fluctuates over time (Cancro & Smith, 2003; Weyand et al, 2003; Faria et al, 2008; Surh & Sprent, 2008). Also, it will be of interest to examine whether frail or chronically ill elders have an even more contracted NK cell compartment, or perhaps have differential representation of NK cell subsets compared to elders who are highly functioning despite a history of comorbidity and/or current subclinical conditions (Carey et al, 2004; Rosano et al, 2005; Covinsky et al, 2006; Brach et al, 2007; Auyueng et al, 2008; Whitson et al, 2010). And since NK cells can express CD16 or CD56 either alone or together on the same cell, an important undertaking will be to determine whether these two receptors are independently regulated or that they co-regulate (or counter regulate) each other during the aging process.

Other adverse age-related alterations in the NK cell compartment have been reported. A current notable finding is the age-related shift in the proportions of CD56high and CD56low NK cells, the latter subset being more represented in old age (Le Graff-Tavernier et al, 2010). However, there remains a controversy as to whether these cells represent a continuum of phenotype of CD56-expressing NK cells or if they represent distinct lineages of NK cells. There is also no consensus about a quantitative definition for high-versus-low level of expression of CD56. Similar phenotypic studies indicate varying increases in the proportions of CD56+/CD16+ NK cell subsets co-expressing other NKRs such as NKG2D, CD94, NKG2A, and KLRG1 (Sansoni et al, 1993; Borrego et al, 1999; Le Garff-Tavernier et al, 2010; Hayhoe et al, 2010; Yan et al, 2010). Whether such increases in expression levels of NKR translates into better NK cell-mediated effector function would likely depend on the efficiency of NKR signaling, and the extent to which an activating NKR signal would be counter regulated by an inhibitory NKR signal.

Although it is not yet clear whether and how individual NKRs have signaling defects, there are several indicators of age-related insufficiency of NK cell function. The best example is the reduction of cytokine production by NK cells following activation, either through ligation of individual NKRs or through pharmacologic activators (Borrego et al, 1999; Mariani et al, 2001). There is also an age-dependent decrease in the level of perforin expression (Ruvakina et al, 1998), and a corresponding general decrease in spontaneous (or natural) killing activity of NK cells of older adults (Ogata et al, 1997; Mocchegiani et al, 2003). Antibody-dependent cytotoxocity (ADCC) of NK cells however, has been shown to be comparable between young and older adults (Fernandes & Gupta, 1981; Mariani et al, 1998; Lutz et al, 2005). ADCC, which is mediated through triggeting of CD16, could nevertheless still be significantly reduced in aged NK cells where CD16 is coexpressed increased levels of inhibitory NKR particularly CD158/KIR family members (Mariani et al, 1994). Collectively, all the above observations indicate that NK cell functional deficiency with aging is related to size contraction of the NK compartment, the types and density of the expression of particular NKR, and the efficiency of NKR signaling.

Healthy longevity and diversity of immune phenotypes among the elderly: A conundrum of the Damage Paradigm

Compared to younger persons, older adults clearly have less robust immune responses. But as alluded to previously, elders have highly heterogeneous health phenotypes, ranging from frail institutionalized persons to those who are highly functional and living independently (Newman et al, 2003, 2006; Yaffe et al, 2003; Rosano et al, 2005; Love et al, 2008; Strotmeyer et al, 2010). As illustrated in Figure 1A, graphs II and III, many elders are in fact living exceptionally well beyond the median lifespan of many populations (Yates et al, 2008; Yashin et al, 2010). Despite history of chronic conditions, some elders neither exhibit significant physical nor cognitive disability nor do they undergo frailty, a phenomenon referred to as exceptional aging (Christensen et al, 2008). While significant improvement of medical care in the 20th and 21st century has contributed to longer, and arguably healthier, lifespan especially in Western societies, there is increasing evidence for underlying biological factors that promote exceptional aging and longevity. As depicted in Figure 1A, there could be biological pathways either elaborated during midlife (graph II) or are predetermined at birth (graph III), that substantially dampen, if not protect against, the ill-effects of age-related physiologic damage. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss what the determinants of longevity are, long life runs in families (Shoenmaker et al, 2006; Willcox et al, 2006). Furthermore, there is mounting evidence for a genetic basis of healthy aging and longevity (Lunetta et al, 2007; Lescai et al, 2009; Newman et al, 2010; Sebastiani et al, 2010).

In addition to lifespan extension, another difficulty of the damage paradigm are observations that different organ systems do not age at the same rate, nor do they undergo the aging process by the same mechanism. Advances in developmental biology indicate that aging is part of the program of development inclusive of processes of damage, repair, and regeneration consistent with a developmental paradigm of aging (Zwaan, 2003; deMagalhaes & Church, 2005). This is illustrated in Figure 1B showing at least five types of developmental programs. Program I depicts the rapid rise and fall of physiological processes related to reproduction. Program II depicts the rapid postnatal decline of processes related to fetal development, exemplified by insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-2 and cartilage growth (Nillson & Baron, 2004; Gicquel & Le Bouc, 2006). Program III, which likely depicts the development and aging process for many of tissues and organs, pertains to the slow increases in organ size and physiological function from birth, peaking around reproductive maturity, and then slowly decline thereafter. Among the best examples are growth hormone, IGF-1, bone density, muscle mass, and cognitive function (Veldhius, 2008; Nithianantharajah & Hannan, 2009; Perrini et al, 2010). Program IV depicts processes that are at maximal at birth, then slowly decline through reproductive maturity, and subsequently undergo more rapidly decline thereafter. Examples are the thymus and naïve T cells as described above, as well as hematopoietic stem cells (Geiger & van Zant, 2002) and B cell precursors (Frasca et al, 2008). And Program V depicts the slow and steady rise of physiological function with time. This is exemplified by the accumulation of naïve B cells (Frasca et al, 2008), and by the expansion of the memory T cell compartment as described above. These differential rates of development, maturation, and aging in the various physiological systems suggest that health outcomes of old age may not be solely attributed to damage per se, but the extent to which physiological systems adapt to damage. The observed wide range of health phenotypes of elders likely reflects the varying degrees of repair and replenishment, and/or by the elaboration of novel protective mechanisms. As indicated previously, exceptional aging is not the absence of damage, but the capacity to retain function despite the damage (Christensen et al, 2008).

Indeed, elders exhibit vast heterogeneity in immune responsiveness. This is perhaps best illustrated by the work by Bernstein et al (1999) in the context of influenza vaccination. Bioassays of anti-influenza T cell and antibody responses show that while 40% of elders examined are unresponsive, there are three categories of responders: 32% are antibody responsive only, 15% are T cell responsive only, and 15% have intact T cell and antibody responses. The latter group of elders carries leukocytes that are capable of producing large amounts of IFN-γ when the cells are stimulated in vitro. In a similar study by McElhaney et al (1998), the interesting finding is that some older adults can have even higher IFN-γ responses to particular strains of influenza virus than younger people. This is corroborated by recent findings that older adults have H1N1-reactive memory T cells (and B cells) (Gras et al, 2010; Skountzou et al, 2010), hence they had been found to be less susceptible to the recent H1N1 influenza pandemic (Fisman et al, 2009). As to protection from seasonal influenza infection, work by Schwaiger et al (2003) demonstrates the association between a specific subset of T cells, namely, IL-4-producing CD62Lhi CD8+ T cells, and protective anti-influenza responses among older adults. Collectively, these studies are consistent with our idea for novel mechanisms of immune homeostasis in old age, and that aging is not synonymous with immune incompetence (Vallejo, 2007). Unraveling of these mechanisms will help refine the definition of immune competence based on the normal biology of older people rather than continuing to use definitions based on analogy with the biology of younger persons. A challenge therefore is to identify cellular and humoral parameters that underlie immune competence or incompetence among old people, as well as those that predict future health outcomes.

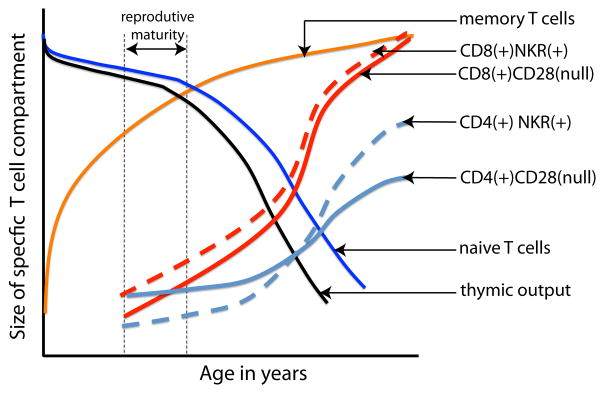

Expression of NKRs on T cells with advancing age: An emerging immunologic theme underlying successful aging

There is mounting evidence that T cells acquire NKRs with chronologic aging (Abedin et al, 2005; Peralbo et al, 2007). We have articulated that acquisition of NKRs by T cells with aging may compensate for the loss of αβTCR repertoire diversity (Vallejo, 2007). Among the evidence for this idea is the finding that T cells with identical TCRs, indicating derivation from a single mother cell, express a diverse array of NKRs with no two TCR-identical cells expressing the same repertoire of NKRs (Snyder et al, 2002). Considering the large superfamily of NKRs, with CD85 (or leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor, LIR) and CD158 (KIR) families consisting of multigenic and polymorphic members (Bashirova et al, 2006; Barrow & Trowsdale, 2008) their expression on clonal lineages of T cells creates a secondary level of diversity with functionally diverse NKR+ T cells (Vallejo, 2006). We further suggest that expression of NKRs on T cells with aging may compensate for the contraction in the size of the NK cell compartments as described above. Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between the progressive contraction of TCR diversity, and the corresponding accumulation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing a variety of NKRs. As noted previously, TCR repertoire contraction with aging is related to the atrophy of the thymus, the contraction of the naïve T cell reserve, and the accumulation of memory T cells. NKR-bearing T cells have memory phenotype (Ugoloni et al, 2001; Vely et al, 2001; van Bergen et al, 2004), are TCR-oligoclonal (Mingari et al, 1996; Uhrberg et al, 2001; Snyder et al, 2002; Abedin et al, 2005; Michel et al, 2007), and are mostly deficient in the expression of CD28. The irreversible loss of CD28 is the most consistent feature T cells undergoing senescence (Vallejo et al, 1999, 2002). The basis of the observed differences in the rate of loss of CD28 and the gain of NKRs between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells is not yet fully understood. However, CD8+ T cells have a more rapid turnover and faster rate of inactivation of telomerase making them more susceptible to senescence compared to CD4+ T cells (Valenzuela & Effros, 2002; Parish et al, 2010).

Figure 2. Age-related changes in the composition of the T cell compartments.

Thymic atrophy, depletion of the naïve compartment, and the corresponding expansion of the memory are the most significant physiologic impact of aging. All of these processes contribute the phenomenal contraction of TCR repertoire diversity in old age (Naylor et al, 2005). A characteristic feature of the T cell population in old age are large TCR-clonal subsets of the T cells that have lost expression of CD28 (Vallejo, 2005) but have gained of expression of various NKRs (Abedin et al, 2005; Peralbo et al, 2007). The latter receptors are expressed codominantly and in varying combinations. TCR clonal analyses have shown that even TCR-identical cells can express different repertoire of NKRs (Snyder et al, 2002) indicating a secondary level to T cell diversity (see text for discussion and related reference citations). Diversity of NKR+ T cells suggests novel effector functions, unraveling of which could pave ways to alternative interventions to improve immune function in old age.

NKR+ T cells are αβT cells expressing different TCRA and TCRB genes. Like conventional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, their clonotypic TCR is specific for antigen that is displayed by classical MHC molecules (Uhrberg et al, 2001; van Bergen 2004, 2009; Kennedy et al, 2008). NKR+ T cells are distinct from the so called invariant NKT (iNKT) cells, which are identified by the expression of an invariant TCR AV24 that recognize antigen in a CD1-dependent manner (Peralbo et al, 2007). iNKT cells are innate cells that elicit immune responses against lipoproteins and other pathogen-associated molecular pattern substances (Godfrey et al, 2010).

We have reported an age-dependent increased expression of CD56, the classic NKR, on clonal lineages of T cells (Lemster et al, 2008). It appears that accumulation of CD56+ T cells in both CD4 and CD8 compartments is a signature of centenarians (Sansoni et al, 1993; Miyaji et al, 1997). Other investigators have also reported varying frequency of T cells expressing the other prototypic NKR, CD16, particularly among healthy young and middle-aged adults (Lanier et al, 1985; Uciechowski et al, 1992; Zupo et al, 1993; McNerlan et al, 1998). Similar increased expression of other NKRs on T cells with aging have been found. Among the most commonly observed are members of the KIR family (van Bergen et al, 2004, 2009), and KLGR1 (Ouyang et al, 2003). KLRG1 is of significant interest because signaling from this receptor can directly lead to mitotic arrest of T cells (Voehringer et al, 2002; Henson et al, 2009), suggesting an active role of NKR in either the initiation or the maintenance of T cell senescence. On the other hand, we have found that NKR+ T cells from older adults generally have limited or have completely lost capacity to undergo mitosis, and that CD56+ T cells express high levels of expression the mitotic inhibitors p16 and p53 (Abedin et al, 2005; Lemster et al, 2008). Whether KLRG1 and CD56 signal senescence through p16 or p53 remains to be examined. Nonetheless, expression of high levels of KLRG1, p16, and p53 in these NK-like T cells are consistent with the reported overall senescence of the entire T cell pool with advancing age (Liu et al, 2009).

Age-dependent increased expression of NKRs on T cells is physiologically programmed rather than a random event of the aging process. NKRs are sporadically expressed on T cells of the young, and become more prevalent on T cells with advancing age (Abedin et al, 2005; Peralbo et al, 2007). Ontogenetically, NKRs are found only T cells with already recombined TCRs (Uhrberg et al, 2001), and only on memory T cells as described previously. There is evidence of fine regulation between T cells and NK cells at the level of the cis-regulatory promoter elements (Stewart et al, 2003; Xu et al, 2005), as well as by highly regulated epigenetic control (Li et al, 2008). As to what exactly triggers and/or modulates NKR expression with aging remains to be more rigorously examined. TCR engagement alone has been shown to induce expression for some NKRs on T cells in vitro (Huard & Karlsson, 2000). Several studies suggest the importance of the cytokine milieu, with certain NKRs being preferentially expressed in response to specific cytokines or combinations thereof in a variety of biological situations (Ponte et al, 1998; Roberts et al, 2001; Burgess et al, 2006; von Geldern et al, 2006; Graham et al, 2007; Crane et al, 2010). However, limiting dilution analysis of in vitro generated T cell clones show that even clonotypes growing within the same environment express different NKRs (Snyder et al, 2002). Determining whether the differential expression of NKRs between any two T cells clones involves fine-tuning of the combined signals from the TCR and from cytokine receptors, and/or perhaps a yet unknown third signal may require a single cell analysis approach.

Despite their limited ability to undergo cell division (Abedin et al 2005; Lemster et al, 2008; Henson et al, 2009), aged NKR+ T cells are functionally active lymphocytes. In cases where the TCR has retained functional integrity, NKRs such members of the CD158 family have been shown to serve as a costimulatory receptor with equivalent potency as CD28 (Snyder et al, 2004a; van Bergen et al, 2009; van der Veken et al, 2009). In fact, family members of CD158 and NKG2 have been shown to differentially costimulate cytokine production and cytotoxicity (Groh et al, 2001; Snyder et al, 2004b). Similarly, we have reported that CD56 can serve as both as costimulator to the TCR and as an independent signaling receptor for T cells (Lemster et al, 2008). TCR-independent ligation of CD56 alone strongly elicits cellular activation and cytokine production. Whether similar TCR-independent activation of aged CD16+ T cells can be achieved by CD16 triggering remains to be examined. Nevertheless, all these observations suggest that where the aged TCR is still capable trigger signal transduction, NKR signaling could augment cellular responses. And where the aged TCR has more pronounced signaling defects, direct NKR signaling could compensate and elicit a TCR-independent response implying an innate function of the aged NKR+ αβT cell. Interestingly, the number of the true innate iNKT cells has also been shown to decline with advancing age (Jing et al, 2007), suggesting yet another possibility for a compensatory role for the rise of NKR+ αβT cells with age.

Research Directions and Conclusion

The diversity of NKR-expressing αβT cells suggests multitude of T cell effectors that could be exploited to improve immune function. For example, expression of CD16 on aged T cells suggests an exciting notion for a role of such T cells in opsonin-mediated clearance of bacterial pathogens. It might also be possible to redesign vaccines to capitalize on the direct viral reactivity of NKG2 and CD158 family of NKRs. A challenge to successful clinical translation is likely to be dependent on ascertaining whether inhibitory NKRs interfere with activating NKRs in the elaboration of aged T cell responses in a manner akin to their roles in influencing classical NK cell function. Of interest as well is whether particular NKR+ T cell subsets can be useful predictors or prognosticators of health outcomes of aging. This would require molecular studies to ascertain the continuum of NK-like phenotypes of αβT cells in both highly functioning and chronically ill elders. Considering the codominant expression of NKRs, elucidation of mechanisms regulating the expression of one particular NKR over another and/or how the acquisition of one NKR affects the expression of another will be of paramount interest.

Acknowledgments

Research is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 AG030734, R01 AG022379).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abedin S, Michel JJ, Lemster B, Vallejo AN. Diversity of NKR expression in aging T cells and in T cells of the aged: the new frontier into the exploration of protective immunity in the elderly. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:537–548. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberti S, Cevenini E, Ostan R, Capri M, Salvioli S, Bucci L, Ginaldi L, De Martinis M, Franceschi C, Monti D. Age-dependent modifications of Type 1 and Type 2 cytokines within virgin and memory CD4+ T cells in humans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2006;127:560–566. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arstila TP, Casrouge A, Baron V, Even J, Kanellopoulos J, Kourilsky PA. A direct estimate of the human alphabeta T cell receptor diversity. Science. 1999;286:958–961. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5441.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auyeung TW, Kwok T, Lee J, Leung PC, Leung J, Woo J. Functional decline in cognitive impairment--the relationship between physical and cognitive function. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;31:167–173. doi: 10.1159/000154929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrow AD, Trowsdale J. The extended human leukocyte receptor complex: diverse ways of modulating immune responses. Immunol Rev. 2008;24:98–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashirova AA, Martin MP, McVicar DW, Carrington M. The killer immunoglobulin-like receptor gene cluster: tuning the genome for defense. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2006;7:277–300. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benne C, Lelievre JD, Balbo M, Henry A, Sakano S, Levy Y. Notch increases T/NK potential of human hematopoietic progenitors and inhibits B cell differentiation at a pro-B stage. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1676–1685. doi: 10.1002/stem.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E, Kaye D, Abrutyn E, Gross P, Dorfman M, Murasko DM. Immune response to influenza vaccination in a large healthy elderly population. Vaccine. 1999;17:82–94. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum KS, Pabst R. Lymphocyte numbers and subsets in the human blood. Do they mirror the situation in all organs? Immunol Lett. 2007;108:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrego F, Alonso MC, Galiani MD, Carracedo J, Ramirez R, Ostos B, Peña J, Solana R. NK phenotypic markers and IL2 response in NK cells from elderly people. Exp Gerontol. 1999;34:253–265. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(98)00076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brach JS, Studenski SA, Perera S, VanSwearingen JM, Newman AB. Gait variability and the risk of incident mobility disability in community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:983–988. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.9.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess SJ, Marusina AI, Pathmanathan I, Borrego F, Coligan JE. IL-21 down-regulates NKG2D/DAP10 expression on human NK and CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:1490–1497. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancro MP, Smith HS. Peripheral B cell selection and homeostasis. Immunol Res. 2003;27:141–148. doi: 10.1385/IR:27:2-3:141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao JN, Gollapudi S, Sharman EH, Jia Z, Gupta S. Age-related alterations of gene expression patterns in human CD8+ T cells. Aging Cell. 2010;9:19–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey EC, Walter LC, Lindquist K, Covinsky KE. Development and validation of a functional morbidity index to predict mortality in community-dwelling elders. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1027–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40016.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspar-Bauguil S, Cousin B, André M, Nibbelink M, Galinier A, Periquet B, Casteilla L, Pénicaud L. Weight-dependent changes of immune system in adipose tissue: importance of leptin. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:2195–2202. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheent K, Khakoo SI. Natural killer cells: integrating diversity with function. Immunology. 2009;126:449–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03045.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Gorelik GJ, Strickland FM, Richardson BC. Decreased ERK and JNK signaling contribute to gene overexpression in “senescent” CD4+CD28- T cells through epigenetic mechanisms. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;87:137–145. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0809562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen K, McGue M, Petersen I, Jeune B, Vaupel JW. Exceptional longevity does not result in excessive levels of disability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13274–13279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804931105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covinsky KE, Hilton J, Lindquist K, Dudley RA. Development and validation of an index to predict activity of daily living dependence in community-dwelling elders. Med Care. 2006 Feb;44(2):149–57. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000196955.99704.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane CA, Han SJ, Barry JJ, Ahn BJ, Lanier LL, Parsa AT. TGF-beta downregulates the activating receptor NKG2D on NK cells and CD8+ T cells in glioma patients. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:7–13. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Magalhães JP, Church GM. Genomes optimize reproduction: aging as a consequence of the developmental program. Physiology. 2005;20:252–259. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00010.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Jing Y, Campbell AE, Gravenstein S. Age-related impaired type 1 T cell responses to influenza: reduced activation ex vivo, decreased expansion in CTL culture in vitro, and blunted response to influenza vaccination in vivo in the elderly. J Immunol. 2004;172:3437–3446. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douek DC, McFarland RD, Keiser PH, Gage EA, Massey JM, Haynes BF, Polis MA, Haase AT, Feinberg MB, Sullivan JL, et al. Changes in thymic function with age and during the treatment of HIV infection. Nature. 1998;17:690–695. doi: 10.1038/25374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagle RA, Trowsdale J. Promiscuity and the single receptor: NKG2D. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:737–744. doi: 10.1038/nri2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkeller-Yuksel FM, Deneys V, Yuksel B, Hannet I, Hulstaert F, Hamilton C, Mackinnon H, Stokes LT, Munhyeshuli V, Vanlangendonck F, et al. Age-related changes in human blood lymphocyte subpopulations. J Pediatr. 1992;120:216–222. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80430-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faria AM, de Moraes SM, de Freitas LH, Speziali E, Soares TF, Figueiredo-Neves SP, Vitelli-Avelar DM, Martins MA, Barbosa KV, Soares EB, et al. Variation rhythms of lymphocyte subsets during healthy aging. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2008;15:365–379. doi: 10.1159/000156478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Interagency Forum. National Center for Health Statistics; Washington, DC: 2008. Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, Older Americans 2008: Key indicators of well-being; p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes G, Gupta S. Natural killing and antibody-dependent cytotoxicity by lymphocyte subpopulations in young and aging humans. J Clin Immunol. 1981;1:141–148. doi: 10.1007/BF00922755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisman DN, Savage R, Gubbay J, Achonu C, Akwar H, Farrell DJ, Crowcroft NS, Jackson P. Older age and a reduced likelihood of 2009 H1N1 virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2000–2001. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0907256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasca D, Landin AM, Lechner SC, Ryan JG, Schwartz R, Riley RL, Blomberg BB. Aging down-regulates the transcription factor E2A, activation-induced cytidine deaminase, and Ig class switch in human B cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:5283–5290. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger H, van Zant G. The aging of lympho-hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:329–333. doi: 10.1038/ni0402-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gicquel C, Le Bouc Y. Hormonal regulation of fetal growth. Horm Res. 2006;65:S28–S33. doi: 10.1159/000091503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey DI, Stankovic S, Baxter AG. Raising the NKT cell family. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:197–206. doi: 10.1038/ni.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham CM, Christensen JR, Thomas DB. Differential induction of CD94 and NKG2 in CD4 helper T cells. A consequence of influenza virus infection and interferon-gamma? Immunology. 2007;121:238–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02563.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gras S, Kedzierski L, Valkenburg SA, Laurie K, Liu YC, Denholm JT, Richards MJ, Rimmelzwaan GF, Kelso A, Doherty PC, et al. Cross-reactive CD8+ T-cell immunity between the pandemic H1N1-2009 and H1N1-1918 influenza A viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:12599–12604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007270107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groh V, Rhinehart R, Randolph-Habecker J, Topp MS, Riddell SR, Spies T. Costimulation of CD8alphabeta T cells by NKG2D via engagement by MIC induced on virus-infected cells. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:255–260. doi: 10.1038/85321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadrup SR, Strindhall J, Køllgaard T, Seremet T, Johansson B, Pawelec G, thor Straten P, Wikby A. Longitudinal studies of clonally expanded CD8 T cells reveal a repertoire shrinkage predicting mortality and an increased number of dysfunctional cytomegalovirus-specific T cells in the very elderly. J Immunol. 2006;176:2645–2653. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayhoe RP, Henson SM, Akbar AN, Palmer DB. Variation of human natural killer cell phenotypes with age: identification of a unique KLRG1-negative subset. Hum Immunol. 2010;71:676–681. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson SM, Franzese O, Macaulay R, Libri V, Azevedo RI, Kiani-Alikhan S, Plunkett FJ, Masters JE, Jackson S, Griffiths SJ, et al. KLRG1 signaling induces defective Akt (ser473) phosphorylation and proliferative dysfunction of highly differentiated CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2009;113:6619–6628. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-199588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeijmakers JH. DNA damage, aging, and cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1475–1485. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodkinson CF, Kelly M, Coudray C, Gilmore WS, Hannigan BM, O’Connor JM, Strain JJ, Wallace JM. Zinc status and age-related changes in peripheral blood leukocyte subpopulations in healthy men and women aged 55–70 yrs: the ZENITH study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59:S63–S67. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huard B, Karlsson L. KIR expression on self-reactive CD8+ T cells is controlled by T-cell receptor engagement. Nature. 2000;403:325–328. doi: 10.1038/35002105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntington ND, Vosshenrich CA, Di Santo JP. Developmental pathways that generate natural-killer-cell diversity in mice and humans. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:703–714. doi: 10.1038/nri2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing Y, Gravenstein S, Chaganty NR, Chen N, Lyerly KH, Joyce S, Deng Y. Aging is associated with a rapid decline in frequency, alterations in subset composition, and enhanced Th2 response in CD1d-restricted NKT cells from human peripheral blood. Exp Gerontol. 2007;42:719–732. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang I, Hong MS, Nolasco H, Park SH, Dan JM, Choi JY, Craft J. Age-associated change in the frequency of memory CD4+ T cells impairs long term CD4+ T cell responses to influenza vaccine. J Immunol. 2004;173:673–681. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy PT, Gehring AJ, Nowbath A, Selden C, Quaglia A, Dhillon A, Dusheiko G, Bertoletti A. The expression and function of NKG2D molecule on intrahepatic CD8+ T cells in chronic viral hepatitis. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15:901–909. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2008.01049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick RD, Rickabaugh T, Hultin LE, Hultin P, Hausner MA, Detels R, Phair J, Jamieson BD. Homeostasis of the naive CD4+ T cell compartment during aging. J Immunol. 2008;180:1499–1507. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku CC, Kappler J, Marrack P. The growth of the very large CD8+ T cell clones in older mice is controlled by cytokines. J Immunol. 2001;166:2186–2193. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanier LL, Kipps TJ, Phillips JH. Functional properties of a unique subset of cytotoxic CD3+ T lymphocytes that express Fc receptors for IgG (CD16/Leu-11 antigen) J Exp Med. 1985;162:2089–2106. doi: 10.1084/jem.162.6.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larbi A, Dupuis G, Khalil A, Douziech N, Fortin C, Fülöp T., Jr Differential role of lipid rafts in the functions of CD4+ and CD8+ human T lymphocytes with aging. Cell Signal. 2006;18:1017–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Garff-Tavernier M, Béziat V, Decocq J, Siguret V, Gandjbakhch F, Pautas E, Debré P, Merle-Beral H, Vieillard V. Human NK cells display major phenotypic and functional changes over the life span. Aging Cell. 2010 May 10; doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemster BH, Michel JJ, Montag DT, Paat JJ, Studenski SA, Newman AB, Vallejo AN. Induction of CD56 and TCR-independent activation of T cells with aging. J Immunol. 2008;180:1979–1990. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lescai F, Blanché H, Nebel A, Beekman M, Sahbatou M, Flachsbart F, Slagboom E, Schreiber S, Sorbi S, Passarino G, Franceschi C. Human longevity and 11p15.5: a study in 1321 centenarians. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:1515–1519. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Epigenetic mechanisms of age-dependent KIR2DL4 expression in T cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:824–834. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0807583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SC, Chou CC, Tsai MJ, Wu KH, Huang MT, Wang LH, Chiang BL. Age-related changes in blood lymphocyte subsets of Chinese children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1998;9:215–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.1998.tb00376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Sanoff HK, Cho H, Burd CE, Torrice C, Ibrahim JG, Thomas NE, Sharpless NE. Expression of p16(INK4a) in peripheral blood T-cells is a biomarker of human aging. Aging Cell. 2009;8:439–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00489.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love OP, Salvante KG, Dale J, Williams TD. Sex-specific variability in the immune system across life-history stages. Am Nat. 2008;172:E99–E112. doi: 10.1086/589521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunetta KL, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Karasik D, Benjamin EJ, Guo CY, Govindaraju R, Kiel DP, Kelly-Hayes M, Massaro JM, Pencina MJ, et al. Genetic correlates of longevity and selected age-related phenotypes: a genome-wide association study in the Framingham Study. BMC Med Genet. 2007;8:S13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz CT, Moore MB, Bradley S, Shelton BJ, Lutgendorf SK. Reciprocal age related change in natural killer cell receptors for MHC class I. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126:722–731. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani E, Mariani AR, Meneghetti A, Tarozzi A, Cocco L, Facchini A. Age-dependent decreases of NK cell phosphoinositide turnover during spontaneous but not Fc-mediated cytolytic activity. Int Immunol. 1998;10:981–989. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.7.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani E, Monaco MC, Cattini L, Sinoppi M, Facchini A. Distribution and lytic activity of NK cell subsets in the elderly. Mech Ageing Dev. 1994;76:177–187. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(94)91592-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani E, Pulsatelli L, Meneghetti A, Dolzani P, Mazzetti I, Neri S, Ravaglia G, Forti P, Facchini A. Different IL-8 production by T and NK lymphocytes in elderly subjects. Mech Ageing Dev. 2001;122:1383–1395. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00270-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani E, Roda P, Mariani AR, Vitale M, Degrassi A, Papa S, Facchini A. Age-associated changes in CD8+ and CD16+ cell reactivity: clonal analysis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1990;81:479–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1990.tb05359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElhaney JE, Upshaw CM, Hooton JW, Lechelt KE, Meneilly GS. Responses to influenza vaccination in different T-cell subsets: a comparison of healthy young and older adults. Vaccine. 1998;16:1742–1747. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNerlan SE, Rea IM, Alexander HD, Morris TC. Changes in natural killer cells, the CD57CD8 subset, and related cytokines in healthy aging. J Clin Immunol. 1998;18:31–38. doi: 10.1023/a:1023283719877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messaoudi I, Lemaoult J, Guevara-Patino JA, Metzner BM, Nikolich-Zugich J. Age-related CD8 T cell clonal expansions constrict CD8 T cell repertoire and have the potential to impair immune defense. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1347–1358. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel JJ, Turesson C, Lemster B, Atkins SR, Iclozan C, Bongartz T, Wasko MC, Matteson EL, Vallejo AN. CD56-expressing T cells that have features of senescence are expanded in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:43–57. doi: 10.1002/art.22310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton D, Gonzelez F. The extensive polymorphism of KIR genes. Immunology. 2010;129:8–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03208.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mingari MC, Schiavetti F, Ponte M, Vitale C, Maggi E, Romagnani S, Demarest J, Pantaleo G, Fauci AS, Moretta L. Human CD8+ T lymphocyte subsets that express HLA class I-specific inhibitory receptors represent oligoclonally or monoclonally expanded cell populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12433–12438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyaji C, Watanabe H, Minagawa M, Toma H, Kawamura T, Nohara V, Nozaki H, Sato Y, Abo T. Numerical and functional characteristics of lymphocyte subsets in centenarians. J Clin Immunol. 1997;17:420–429. doi: 10.1023/a:1027324626199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mocchegiani E, Muzzioli M, Giacconi R, Cipriano C, Gasparini N, Franceschi C, Gaetti R, Cavalieri E, Suzuki H. Metallothioneins/PARP-1/IL-6 interplay on natural killer cell activity in elderly: parallelism with nonagenarians and old infected humans. Effect of zinc supply. Mech Aging Dev. 2003;124:459–468. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(03)00023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumova EN, Gorski J, Naumov YN. Two compensatory pathways maintain long-term stability and diversity in CD8 T cell memory repertoires. J Immunol. 2009;183:2851–2888. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor K, Li G, Vallejo AN, Lee WW, Koetz K, Bryl E, Witkowski J, Fulbright J, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. The influence of age on T cell generation and TCR diversity. J Immunol. 2005;174:7446–7452. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AB, Arnold AM, Naydeck BL, Fried LP, Burke GL, Enright P, Gottdiener J, Hirsch C, O’Leary D, Tracy R Cardiovascular Health Study Research Group. Successful aging: Effect of subclinical cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2315–2322. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.19.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AB, Simonsick EM, Naydeck BL, Boudreau RM, Kritchevsky SB, Nevitt MC, Pahor M, Satterfield S, Brach JS, Studenski SA, Harris TB. Association of long-distance corridor walk performance with mortality, cardiovascular disease, mobility limitation, and disability. JAMA. 2006;295:2018–2026. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AB, Walter S, Lunetta KL, Garcia ME, Slagboom PE, Christensen K, Arnold AM, Aspelund T, Aulchenko YS, Benjamin EJ, et al. A meta-analysis of four genome-wide association studies of survival to age 90 years or older: the Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology Consortium. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:478–487. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nithianantharajah J, Hannan AJ. The neurobiology of brain and cognitive reserve: mental and physical activity as modulators of brain disorders. Prog Neurobiol. 2009;89:369–382. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson O, Baron J. Fundamental limits on longitudinal bone growth: growth plate senescence and epiphyseal fusion. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2004;15:370–374. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata K, Yokose N, Tamura H, An E, Nakamura K, Dan K, Nomura T. Natural killer cells in the late decades of human life. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;84:269–275. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang Q, Wagner WM, Voehringer D, Wikby A, Klatt T, Walter S, Müller CA, Pircher H, Pawelec G. Age-associated accumulation of CMV-specific CD8+ T cells expressing the inhibitory killer cell lectin-like receptor G1 (KLRG1) Exp Gerontol. 2003;38:911–920. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(03)00134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish ST, Wu JE, Effros RB. Sustained CD28 expression delays multiple features of replicative senescence in human CD8 T lymphocytes. J Clin Immunol. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9449-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peralbo E, Alonso C, Solana R. Invariant NKT and NKT-like lymphocytes: two different T cell subsets that are differentially affected by ageing. Exp Gerontol. 2007;42:703–708. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrini S, Laviola L, Carreira MC, Cignarelli A, Natalicchio A, Giorgino F. The GH/IGF1 axis and signaling pathways in the muscle and bone: mechanisms underlying age-related skeletal muscle wasting and osteoporosis. J Endocrinol. 2010;205:201–210. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilbeam K, Basse P, Brossay L, Vujanovic N, Gerstein R, Vallejo AN, Borghesi L. The ontogeny and fate of NK cells marked by permanent DNA rearrangements. J Immunol. 2008;180:1432–1441. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponte M, Bertone S, Vitale C, Tradori-Cappai A, Bellomo R, Castriconi R, Moretta L, Mingari MC. Cytokine-induced expression of killer inhibitory receptors in human T lymphocytes. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1998;9:S69–S72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourgheysari B, Khan N, Best D, Bruton R, Nayak L, Moss PA. The cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ T-cell response expands with age and markedly alters the CD4+ T-cell repertoire. J Virol. 2007;81:7759–7765. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01262-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AI, Lee L, Schwarz E, Groh V, Spies T, Ebert EC, Jabri B. NKG2D receptors induced by IL-15 costimulate CD28-negative effector CTL in the tissue microenvironment. J Immunol. 2001;167:5527–5530. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.5527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichert T, DeBruyère M, Deneys V, Tötterman T, Lydyard P, Yuksel F, Chapel H, Jewell D, Van Hove L, Linden J, et al. Lymphocyte subset reference ranges in adult Caucasians. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1991;60:190–208. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(91)90063-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosano C, Kuller LH, Chung H, Arnold AM, Longstreth WT, Jr, Newman AB. Subclinical brain magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities predict physical functional decline in high-functioning older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:649–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rukavina D, Laskarin G, Rubesa G, Strbo N, Bedenicki I, Manestar D, Glavas M, Christmas SE, Podack ER. Age-related decline of perforin expression in human cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells. Blood. 1998;92:2410–2420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin E, Depinho RA. Linking functional decline of telomeres, mitochondria and stem cells during ageing. Nature. 2010;464:520–528. doi: 10.1038/nature08982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon AB, Richardson A, Pérez VI. Update on the oxidative stress theory of aging: does oxidative stress play a role in aging or healthy aging? Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:642–655. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansoni P, Cossarizza A, Brianti V, Fagnoni F, Snelli G, Monti D, Marcato A, Passeri G, Ortolani C, Forti E, et al. Lymphocyte subsets and natural killer cell activity in healthy old people and centenarians. Blood. 1993;82:2767–2773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenmaker M, de Craen AJ, de Meijer PH, Beekman M, Blauw GJ, Slagboom PE, Westendorp RG. Evidence of genetic enrichment for exceptional survival using a family approach: the Leiden Longevity Study. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:79–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaiger S, Wolf AM, Robatscher P, Jenewein B, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. IL-4-producing CD8+ T cells with a CD62L++(bright) phenotype accumulate in a subgroup of older adults and are associated with the maintenance of intact humoral immunity in old age. J Immunol. 2003;170:613–619. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastiani P, Solovieff N, Puca A, Hartley SW, Melista E, Andersen S, Dworkis DA, Wilk JB, Myers RH, Steinberg MH, et al. Genetic Signatures of Exceptional Longevity in Humans. Science. 2010 doi: 10.1126/science.1190532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahabuddin S. Quantitative differences in CD8+ lymphocytes, CD4/CD8 ratio, NK cells, and HLA-DR(+)-activated T cells of racially different male populations. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1995;75:168–170. doi: 10.1006/clin.1995.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skountzou I, Koutsonanos DG, Kim JH, Powers R, Satyabhama L, Masseoud F, Weldon WC, del Martin MP, Mittler RS, Compans R, et al. Immunity to pre-1950 H1N1 influenza viruses confers cross-protection against the pandemic swine-origin 2009 A (H1N1) influenza virus. J Immunol. 2010;185:1642–1649. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder MR, Muegge LO, Offord C, O’Fallon WM, Bajzer Z, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Formation of the killer Ig-like receptor repertoire on CD4+CD28null T cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:3839–3846. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.3839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder MR, Nakajima T, Leibson PJ, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Stimulatory killer Ig-like receptors modulate T cell activation through DAP12-dependent and DAP12-independent mechanisms. J Immunol. 2004a;173:3725–3731. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder MR, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. The double life of NK receptors: stimulation or co-stimulation? Trends Immunol. 2004b;25:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CA, Van Bergen J, Trowsdale J. Different and divergent regulation of the KIR2DL4 and KIR3DL1 promoters. J Immunol. 2003;170:6073–6081. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strotmeyer ES, Arnold AM, Boudreau RM, Ives DG, Cushman M, Robbins JA, Harris TB, Newman AB. Long-term retention of older adults in the Cardiovascular Health Study: implications for studies of the oldest old. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:696–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02770.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundström Y, Nilsson C, Lilja G, Kärre K, Troye-Blomberg M, Berg L. The expression of human natural killer cell receptors in early life. Scand J Immunol. 2007;66:335–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.01980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surh CD, Sprent J. Homeostasis of naive and memory T cells. Immunity. 2008;29:848–862. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uciechowski P, Gessner JE, Schindler R, Schmidt RE. Fc gamma RIII activation is different in CD16+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:1635–1638. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugolini S, Arpin C, Anfossi N, Walzer T, Cambiaggi A, Förster R, Lipp M, Toes RE, Melief CJ, Marvel J, et al. Involvement of inhibitory NKRs in the survival of a subset of memory-phenotype CD8+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:430–435. doi: 10.1038/87740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhrberg M, Valiante NM, Young NT, Lanier LL, Phillips JH, Parham P. The repertoire of killer cell Ig-like receptor and CD94:NKG2A receptors in T cells: clones sharing identical alpha beta TCR rearrangement express highly diverse killer cell Ig-like receptor patterns. J Immunol. 2001;166:3923–3932. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela HF, Effros RB. Divergent telomerase and CD28 expression patterns in human CD4 and CD8 T cells following repeated encounters with the same antigenic stimulus. Clin Immunol. 2002;105:117–125. doi: 10.1006/clim.2002.5271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo AN. CD28 extinction in human T cells: altered functions and the program of T-cell senescence. Immunol Rev. 2005;205:158–169. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo AN. Age-dependent alterations of the T cell repertoire and functional diversity of T cells of the aged. Immunol Res. 2006;36:221–228. doi: 10.1385/IR:36:1:221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo AN. Immune remodeling: lessons from repertoire alterations during chronological aging and in immune-mediated disease. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo AN, Brandes JC, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Modulation of CD28 expression: distinct regulatory pathways during activation and replicative senescence. J Immunol. 1999;162:6572–6579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo AN, Bryl E, Klarskov K, Naylor S, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Molecular basis for the loss of CD28 expression in senescent T cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46940–46949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207352200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bergen J, Thompson A, van der Slik A, Ottenhoff TH, Gussekloo J, Koning F. Phenotypic and functional characterization of CD4 T cells expressing killer Ig-like receptors. J Immunol. 2004;173:6719–6726. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bergen J, Kooy-Winkelaar EM, van Dongen H, van Gaalen FA, Thompson A, Huizinga TW, Feltkamp MC, Toes RE, Koning F. Functional killer Ig-like receptors on human memory CD4+ T cells specific for cytomegalovirus. J Immunol. 2009;182:4175–4182. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0800455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Veken LT, Campelo MD, van der Hoorn MA, Hagedoorn RS, van Egmond HM, van Bergen J, Willemze R, Falkenburg JH, Heemskerk MH. Functional analysis of killer Ig-like receptor-expressing cytomegalovirus-specific CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:92–101. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis JD. Aging and hormones of the hypothalamo-pituitary axis: gonadotropic axis in men and somatotropic axes in men and women. Ageing Res Rev. 2008;7:189–208. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vely F, Peyrat M, Couedel C, Morcet J, Halary F, Davodeau F, Romagne F, Scotet E, Saulquin X, Houssaint E, et al. Regulation of inhibitory and activating killer-cell Ig-like receptor expression occurs in T cells after termination of TCR rearrangements. J Immunol. 2001;166:2487–2494. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voehringer D, Koschella M, Pircher H. Lack of proliferative capacity of human effector and memory T cells expressing killer cell lectinlike receptor G1 (KLRG1) Blood. 2002;100:3698–3702. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Geldern M, Simm B, Braun M, Weiss EH, Schendel DJ, Falk CS. TCR-independent cytokine stimulation induces non-MHC-restricted T cell activity and is negatively regulated by HLA class I. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:2347–2358. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wack A, Cossarizza A, Heltai S, Barbieri D, D’Addato S, Fransceschi C, Dellabona P, Casorati G. Age-related modifications of the human alphabeta T cell repertoire due to different clonal expansions in the CD4+ and CD8+ subsets. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1281–1288. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.9.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyand CM, Fulbright JW, Goronzy JJ. Immunosenescence, autoimmunity, and rheumatoid arthritis. Exp Gerontol. 2003;38:833–441. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(03)00090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitson HE, Landerman LR, Newman AB, Fried LP, Pieper CF, Cohen HJ. Chronic Medical Conditions and the Sex-based Disparity in Disability: The Cardiovascular Health Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010 doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willcox BJ, Willcox DC, He Q, Curb JD, Suzuki M. Siblings of Okinawan centenarians share lifelong mortality advantages. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:345–354. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.4.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie D, McElhaney JE. Lower GrB+ CD62Lhigh CD8 TCM effector lymphocyte response to influenza virus in older adults is associated with increased CD28null CD8 T lymphocytes. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Vallejo AN, Jiang Y, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Distinct transcriptional control mechanisms of killer immunoglobulin-like receptors in natural killer (NK) and in T cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24277–24285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500727200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe K, Lindquist K, Penninx BW, Simonsick EM, Pahor M, Kritchevsky S, Launer L, Kuller L, Rubin S, Harris T. Inflammatory marker and cognition in well-functioning African-American and white elders. Neurology. 2003;61:76–80. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000073620.42047.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager EJ, Ahmed M, Lanzer K, Randall TD, Woodland DL, Blackman MA. Age-associated decline in T cell repertoire diversity leads to holes in the repertoire and impaired immunity to influenza virus. J Exp Med. 2008;205:711–723. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Greer JM, Hull R, O’Sullivan JD, Henderson RD, Read SJ, McCombe PA. The effect of aging on human lymphocyte subsets: comparison of males and females. Immun Ageing. 2010;16:4. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yashin AI, Arbeev KG, AkushevichI Ukraintseva SV, Kulminski A, Arbeeva LS, Culminskaya I. Exceptional survivors have lower age trajectories of blood glucose: lessons from longitudinal data. Biogerontology. 2010;11:257–265. doi: 10.1007/s10522-009-9243-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates LB, Djoussé L, Kurth T, Buring JE, Gaziano JM. Exceptional longevity in men: modifiable factors associated with survival and function to age 90 years. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:284–290. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zupo S, Azzoni L, Massara R, D’Amato A, Perussia B, Ferrarini M. Coexpression of Fc gamma receptor IIIA and interleukin-2 receptor beta chain by a subset of human CD3+/CD8+/CD11b+ lymphocytes. J Clin Immunol. 1993;13:228–236. doi: 10.1007/BF00919976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwaan BJ. Linking development and aging. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ. 2003;47:pe32. doi: 10.1126/sageke.2003.47.pe32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]